#vicky's vritings

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kiss the Burned Grey

Kiss the Burned Grey is up!

#slay the princess#stp burned grey#stp princess#stp grey#stp voice of the smitten#stp voice of the cold#stp voice of the hero#stp narrator#stp long quiet#stp fic#my fic#vicky's vritings#gothic romance

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

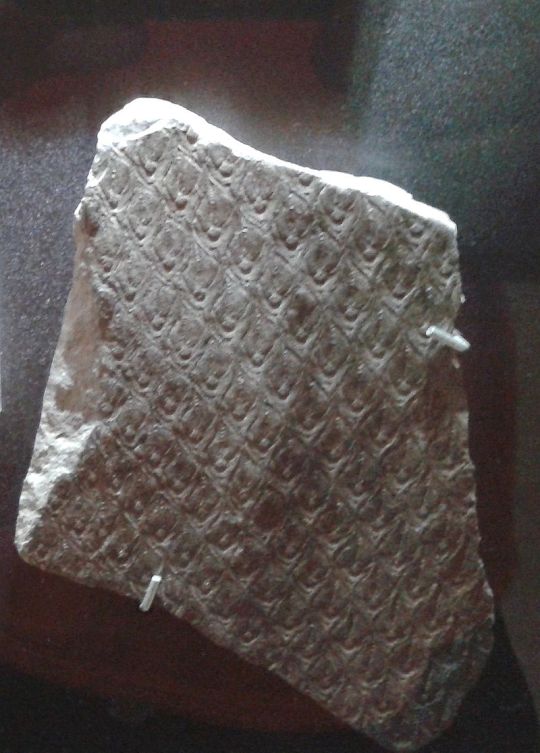

(Image, as well as much of my information, from Carboniferous Giants and Mass Extinction by George R. McGhee Jr.)

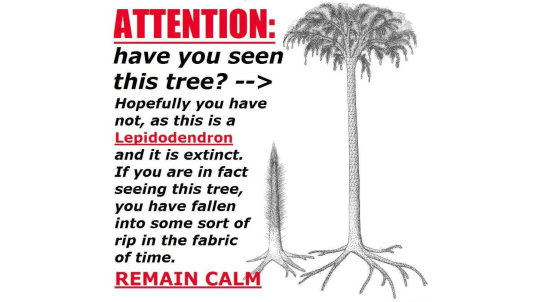

Take a look at this tree. On a scale of 1 to 10, how weird do you think it is?

You quite possibly just gave it a 3 or a 4 or something. Sure, it's a little odd, but does look vaguely normal, right? A friend of mine guessed it was some sort of baobab when I showed him the image.

This is, in fact Lepidodendron, an ancient tree from the Carboniferous, and by modern tree standards it is absolutely bizarre. Its closest surviving relatives, quillworts and clubmosses, only grow to a height of a few centimetres, yet Lepidodendron were giants that shot up to 50 metres tall... Briefly, before dispersing their spores and completely dying off.

(Lycopodium and Spinulum, modern relatives of Lepidodendron, photos by Bernd Haynold and Pete Pattavina)

You see, Lepidondron lived like a gigantic dandelion. For most of its life, it was a stumpy little thing that stuck close to the ground. Just an odd scaly green stump with some long leaves poking out. The green scales its bark consisted of were the place it conducted its photosynthesis, and thus basically did the work of leaves. The Lepidodendron would stay like this for a couple years, slowly expanding its roots and getting ready for the next step. But its roots would grow mostly horizontally, down not so much! And part of why is that even they had the scaly leaf-like photosynthetic bark. That's right, even their roots could - and to some extend needed to - photosynthesise!

(Fossil Lepidodendron bark in the National Museum of Brazil, photo by Dornicke; a fossilised relative of Lepidodendron with some of its roots visible, photo by Michael C. Rygel)

So why would you ever try to photosynthesise with your roots of all things as a plant? Surely it would make much more sense to just transport the sugars created in other parts there than to have your roots be so shallow that bits of them can catch a little light and make it in situ? Sure, if you're capable of that! This is what modern trees do, but they have two separate vascular tissues they use for transport: xylem, which moves water from the roots to the rest of the plant, and phloem, which moves sugars and other photosynthetic products from the leaves to the rest of the plant. Unfortunately for Lepidodendron, it only had xylem, no phloem, so its sugars were only ever going to move as far as they could diffuse, so every part of the tree needed to have at least a little photosynthesis happening, even the roots.

This truly gets ridiculous when the Lepidodendron decides after a few years of charging up that it's time to reproduce. That's when the weird green stump we have so far starts shooting up, up, up, very quickly, all the way until an enormous 40 or 50 metres in height. Now, modern trees grow this large by being supported by a sturdy wooden core, but that's not what Lepidodendron did. To hold up the entire tree, it relies entirely on its outer bark thickening as it grows. In mechanical terms, it was little more than a huge hollow pole, probably creaking and swaying terribly in the wind. Although I have not been able to confirm this in the literature so far, I suspect that between the shallow roots and the whole thing being held up by its bark, you could probably total a Lepidodendron with a good kick.

Now remember, all this growth is happening without phloem, so the entire length of that stem has to not just be sturdy enough to keep the tree standing, but it also has to keep doing photosynthesis to feed itself. When it reaches its full height, the top of the tree finally starts sprouting branches and small leaves, leaving it looking like the picture at the start. But those are not what it's all about for the tree: the cones that develop among them are. At a height of 50 metres, the spores produced by the cones can very easily be picked up by the wind and blown far, far away. Being spores, rather than seeds as modern trees have, they have no supplies built in whatsoever, so they need to get lucky to land in a spot that has immediate access to water. Luckily, there are a lot of those in the vast Carboniferous swamps, and with the trees doing so much work to spread the spores very widely, some of them are sure to find good spots. And then, with the spores dispersed, the tree is done for. The entire thing, which has just grown to the skies, dies off and soon comes crashing down.

So how weird is this tree? I'd call it a perfect 10.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's what Mars gets! Phobos, its nearest moon, is tiny compared to ours, but it's also much closer by and the Sun looks smaller because it's farther away, so it still manages to cover up a decent chunk of the Sun. But nothing like the perfect eclipse we have.

The gas giants have plenty of moons, but because the Sun looks much smaller from them as it's so far away, the bigger moons just blot out the entire Sun when they pass in front of it. Of course, we don't really have photos of this from their non-existent surfaces, but we can see the moons' shadows dancing across the planets' clouds!

Now, this happens all the time on Jupiter, every single orbit of the four biggest moons, since they orbit in almost a flat plane seen from the Sun and Jupiter is such a big target for the shadows. But it's much, much rarer on Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, which just like Earth are tilted. The moon shadows only hit the planets during the two spots in the planet's orbit when the moon orbits happen to cross in front of the Sun. And considering how long these worlds take to orbit, that makes it very rare! Which is why there's no real pics of this happening on Neptune, where the opportunity only comes around once every 82 years! And even then, only one of its moons would cast a big enough shadow to see from Earth with Hubble or JWST, since Neptune is kind of far away and we sadly don't have any spacecraft orbiting it.

NO OTHER PLANET IN OUR SOLAR SYSTEM GETS TOTAL SOLAR ECLIPSES!! THE SIZE AND DISTANCE OF OUR MOON FROM EARTH AND THE SUN MAKE THE PERFECT CIRCUMSTANCES TO GET TOTALITY!!! THE EARTH AND MOON ARE SOOOO COOL AND OF COURSE OUR SUN!! I LOVE LIVING ON EARTH I LOVE YOU EARTH I LOVE YOUUUUU MOON I LOVE YOU SUN

#solar eclipse#space#mars#jupiter#saturn#uranus#neptune#vicky's vritings#frankly i'm amazed to find we have that pic of a moon shadow on uranus#that's already ultra-rare#especially when you consider uranus's moons orbit at a crazy 90 degree angle#again all of those moons just blot out the sun or it's a little potato transiting in front of it#the perfect match is unique to earth

80K notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapter four of Kiss the Stranger is up, completing the story! In this installment, we go on an adventure through dimensions and dizziness!

#slay the princess#stp stranger#stp princess#stp fic#stp voice of the contrarian#stp voice of the hero#stp narrator#stp long quiet#my fic#vicky's vritings

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy New Year!

Let's imagine it was the Earth itself that was going into its 2024th year. That is to say, we're compressing the entire history of the Earth into just the past 2023 years. What events would have happened when?

Well, not too much is certain about the first couple decades after our planet formed, until around 50 CE when we were hit by another proto-planet, Theia, and the debris formed the Moon. After a couple years of the planet cooling down again, the oceans formed out of boiling rain. The timing of the origin of life is very uncertain, but there are chemical signs it may very well have happened as early as the second century. Around 200 CE, the gas giants did a big funky orbit-swapping dance, and in the process inflicted the Late Heavy Bombardment on the rest of the solar system, meaning the Earth was suffering a ton of meteorite strikes for the entire third century.

The first indisputable evidence of life is from around 330, and the first stromatolites appear around 470. Those are basically the first fossils, stones created by layer upon layer of oxygen-producing cyanobacteria living and dying on top of one another. But even with oxygen producers evolving, it would take many centuries before oxygen became a major part of the atmosphere: not until the Great Oxygenation Event, which happened during the ninth and tenth centuries. That's also about the time the first complex, eukaryotic cells evolved through a symbiosis between an anaerobic archaean and an oxygen-breathing bacterium. The bacterium became more and more focused on just the oxygen-breathing task inside the larger cell, until its descendants were mitochondria, which as you all know are the powerhouse of the cell. The next seven centuries passed by with only slow, gradual changes, and life continuing to be unicellular and difficult to find in the fossil record.

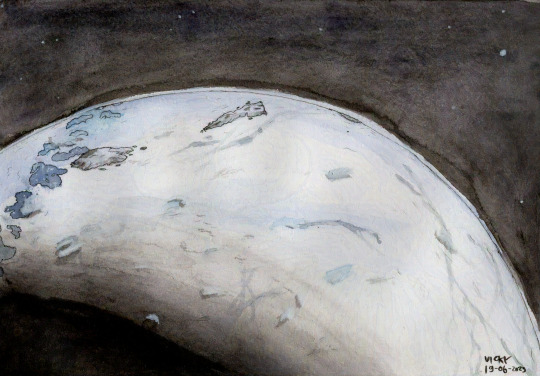

(1735's Snowball Earth, by me)

From 1704 to 1730, the entire planet froze over. After merely two years of thaw, it happened again, this time lasting from 1732 to 1742. But these snowball Earth episodes set the stage for the evolution of animals that began right after. Across the mid-18th century, the bizarre Ediacaran biota, with its strange symmetries, fronds, and fractal-like pattern filled the oceans. In the early 1780s they went extinct, possibly due to a temporary drop in oxygen-levels, only to be replaced by a great variety of quite different creatures in the Cambrian Explosion.

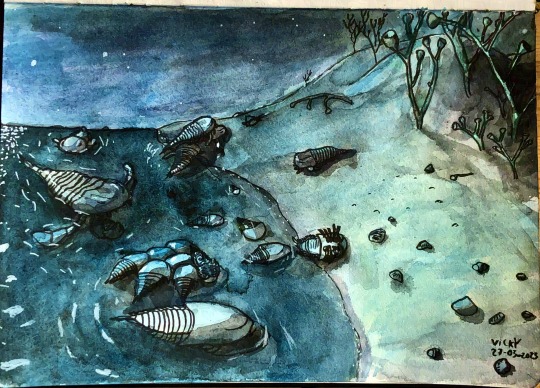

(Class of 1799, by me)

Starting in 1784 and running for a few decades, the Cambrian period saw the origin of most of the modern animal phyla, reaching its most famous form in the Burgess Shale fauna of 1799. During this time, most animals still lived on the sea floor, either attached or crawling, with relatively few actually swimming creatures. Plants started tentatively moving onto land around 1817, and in 1825, the rising of the great Appalachian mountains caused a severe drop in global CO2 and thus temperatures, leading to the Late Ordovician mass extinction.

(Horseshoe crabs and sea scorpions on a beach in 1834, by me)

Bony fish first showed up during the 1830s, and around the same time plants were getting serious about inhabiting the land, evolving roots and vascular tissues so they could properly grow there. Millipedes and the ancestors of spiders were the first animals to follow them onto land. Our own fishy ancestors did not take their first step until 1857, by which point the arthropods were well established there and the plants had figured out how to become trees. The Late Devonian extinction, partially caused by the evolution of said trees and partially by the south pole freezing, played out in two pulses over the late 1850s and early 1860s.

(Swamp prominently featuring Meganeura and Mazothairos in 1889, by me)

Arthropods and vertebrates continued to gain adaptations to life on land. The insects became the first creatures ever to fly in 1878, and the high-oxygen atmosphere of the time would be especially good to them. Around 1884, a group of vertebrates called the amniotes, after the membrane that kept water inside their eggs so they could lay them on land without them drying out, split into two groups: the reptiles and the synapsids (which we mammals descend from). The next few decades would see the synapsids in particular being extremely successful as the supercontinent Pangaea formed. Until 1912, when a massive episode of volcanism caused the worst mass extinction of all time, the Great Dying, scouring the Earth of a huge portion of its life.

(A 1930 scene featuring the three branches of archosaur: dinosaur, pterosaur, and pseudosuchian, by me)

The 1910s were a period of slow recovery during which strange new forms of animal evolved. Many different, unrelated reptiles, such as the ichtyosaurs and plesiosaurs, went to sea, where they would continue to provide some of the most impressive creatures for most of the 20th century. On land, the dinosaurs first appeared in 1920, though for the next decade or so they'd live in the shadow of their pseudosuchian (crocodile-line) cousins. In 1934, Pangaea began to break up, resulting in another terrible pulse of volcanism that caused a lot of extinctions and left particularly the feathered and furry survivors with a lot of empty niches to fill, allowing the dinosaurs and mammals to diversify greatly. The last common ancestor of all modern mammals lived in the early 1940s, and by 1957 the dinosaurs had figured out flight, with Archaeopteryx usually being considered the first bird. Other dinosaurs took on an incredible variety of sizes, shapes, and forms. Some of the most famous ones include Dilophosaurus (1942), Diplodocus and Stegosaurus (1955), Iguanodon (1969), Velociraptor (1991), and Tyrannosaurus rex (1994).

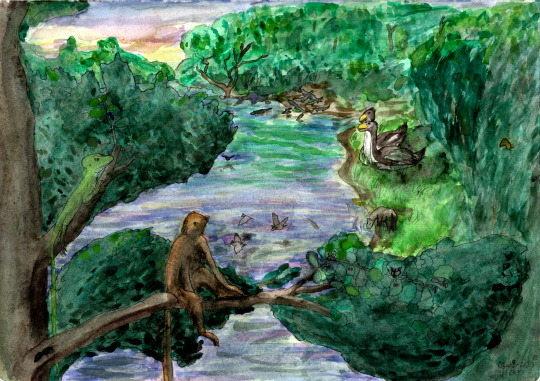

(A tropical lakeside in the year 2000, by me)

In 1995, the world was struck by a meteorite, wiping out many groups, including the marine reptiles, pterosaurs, and ammonites. The surviving mammals and dinosaurs went on to diversify across the next couple of years and had formed thriving new ecosystems in the tropical world of the turn of the millennium. The first known bat lived in 2001, and the whales returned to the oceans next year. Around 2009, the world's climates turned colder and dryer. Antarctica froze over and grasslands spread widely. Our last common ancestor with the chimpanzees and bonobos lived in 2021, and by new year 2023, our ancestors were getting brainier and more proficient with tools. That's also when the north pole froze and the Quaternary ice age cycle began. The first known members of Homo sapiens lived on 10 November 2023. The latest ice age started on 14 December, and ended at 2 AM on 30 December. The great pyramid of Giza was built at 6 AM on 31 December and On The Origin Of Species was published at 23:22 PM.

#palaeoblr#happy new year#2024#geologic timescale#vicky's vritings#one year is 2.244 million years if you're curious#and yes i did exclude both year 0 and 2024#since 0 doesn't exist and 2024 hasn't happened yet#my art#i rather enjoy having an extensive collection of my art to illustrate my paleorambles nowadays#incidentally the big bang occurred in 4121 bce at this scale#which is curiously close to the date of creation creationists made up#if only they would follow through and insist humanity itself was seven weeks old too

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

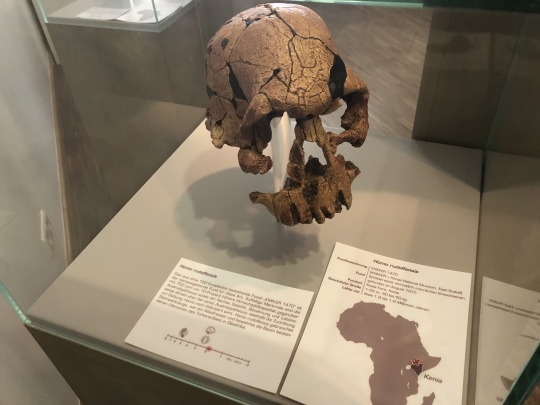

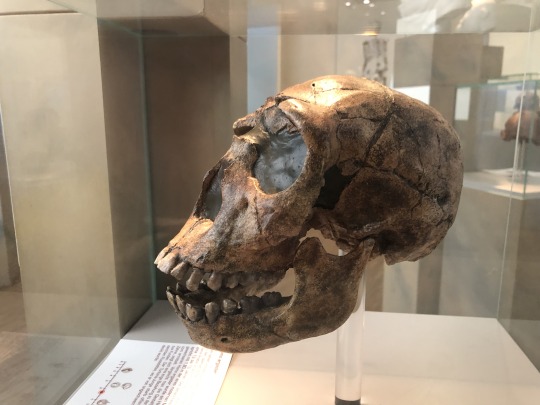

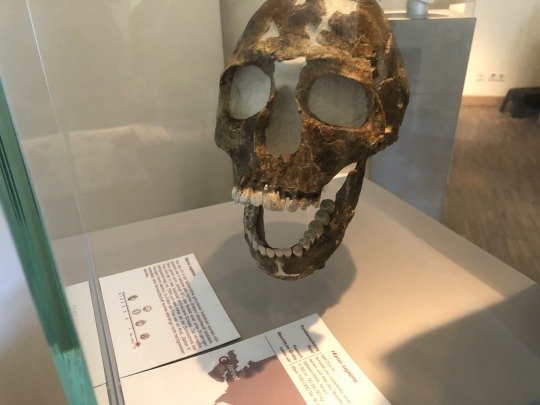

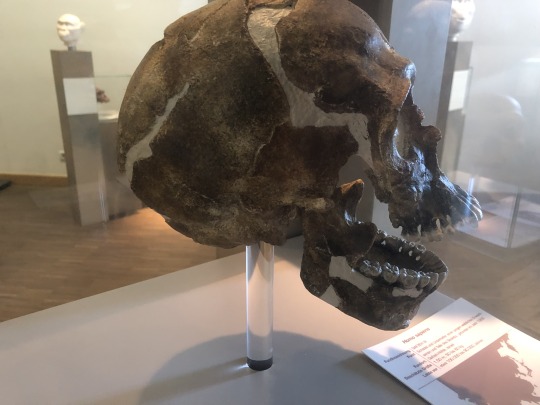

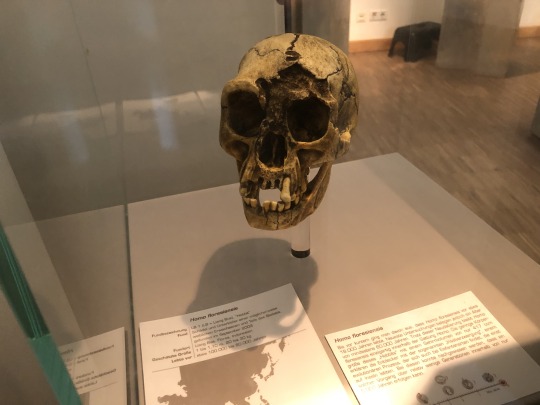

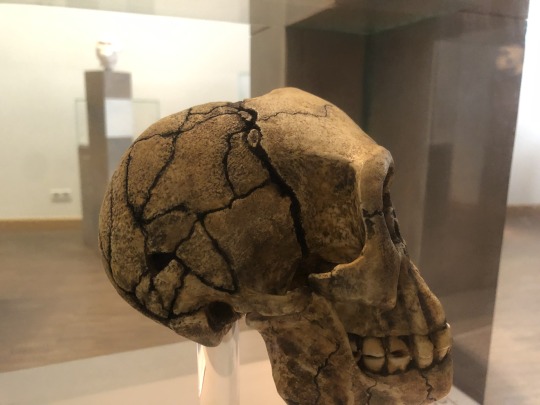

Let's take a closer look at the hominin skulls in the Senckenberg Museum's human evolution room. Keep in mind this is not a linear progression through our ancestors, and more like a bunch of closer and more distant cousins.

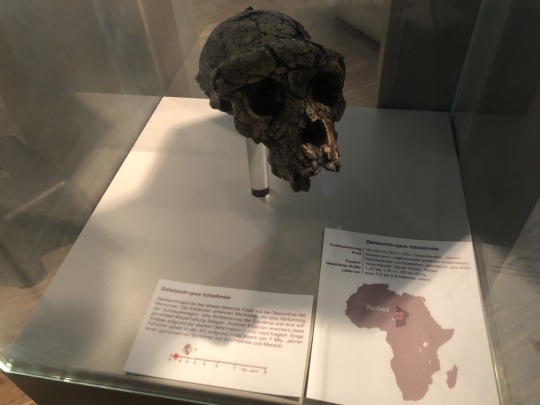

The first one, Sahelanthropus tchadensis is seven million years old, and may very well not be a hominin at all. I've always leaned towards the hypothesis that it's a gorilla relative, not one of ours. No matter which branch of the apes it belongs to, it lived not long after the time the human-line (hominins) and the chimp-line separated, and possibly even before that point!

Ardipithecus ramidus, the first hominin from where we can start making a fairly decent family tree of our relatives. Before this point, 5 million years ago, hominin fossils are very rare, fragmentary, and difficult to assign. One of the most interesting things that does seem to emerge from these early fossils is that we have walked on two legs for a long time. Maybe even so long that our common ancestor with the chimps and bonobos did it!

Lucy represents Australopithecus afarensis, who shows up at this point (3.3 million years ago).

Australopithecus africanus, the Taung child to be precise. We're about 2.8 million years ago at this point. Australopithecines must've been such fascinating creatures.

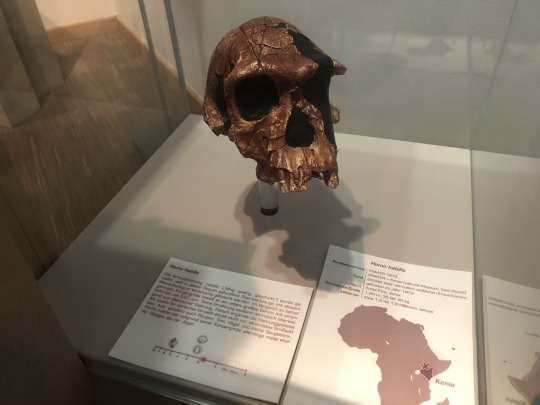

Homo habilis, the 'handy man', named that way because when they were discovered they were thought to be the first humans who used tools. Since then, Australopithecus tools have been found, and tool use by many different animals has also been documented.

Homo rudolfensis, a population of humans who lived at the same time as Homo habilis and were notably bigger and a little brainier. Does it warrant being its own species? That depends who you ask. Splitting vs lumping is a point of contention in almost every group's biology, and it can run especially high in the field of human evolution since hominins are A very high profile and important fossils that directly relate to our own origins, and B an extremely tangled group that seems to have produced loads and loads of isolated populations and subspecies that regularly migrated all over the place and had frequent interbreeding events. Personally I tend to come down on the side of lumping them into a few major species.

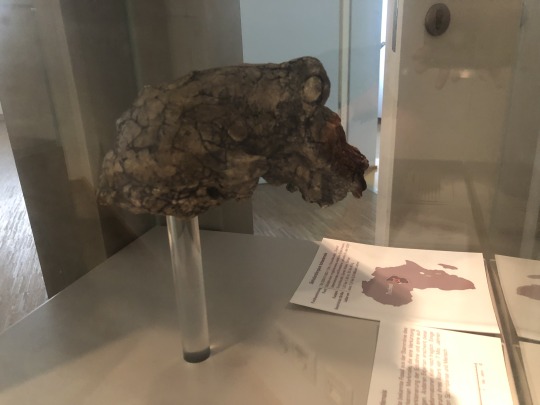

Paranthropus boisei. These were basically a separate lineage of australopithecines, quite different from our own ancestors, who continued to do australopithecus things until quite recently. They were very good climbers and seem to have returned to the trees.

Homo ergaster, either a close relative or a synonym of the more famous Homo erectus. This is the point where we got really brainy, probably figured out how to make fire ourselves, and spread from Africa to Eurasia.

Homo heidelbergensis. Homo erectus and its many subspecies spread all over Africa and Eurasia and existed for well over a million years. As time marches on and evolution did its thing, we eventually start calling the ones in Africa Homo heidelbergensis. They were quite tall, positively enormous compared to little Lucy a few million years back, and they too joined in the human migrations out of Africa. From the H. heidelbergensis who moved into Eurasia we eventually get neanderthals and denisovans, while Homo sapiens evolved from the heidelbergensis populations in Africa.

And there's the neanderthals! Large-brained and creative (the first known cave paintings belong to them and they buried their dead), they were likely quite different from the brutish image we often get from them. Rather than truly dying out, their populations eventually merged with the larger Homo sapiens population once they migrated out of Africa, leaving our modern genes with a couple percent neanderthal DNA.

Homo sapiens. And that's us! Not so much the last remaining branch of the human family tree as much as several of the separate branches ended up coming back together and weaving into a single bigger branch.

And then there's these little guys, Homo floresiensis! Probably originating from a Homo erectus population that ended up on the island Flores, insular dwarfism ended up making them grow quite tiny. On their isolated island, they remained until about 50000 years ago.

#human evolution#sahelanthropus#ardipithecus#australopithecus#homo#ape#primate#mammal#neogene#quaternary#palaeoblr#senckenberg museum#vicky's vritings

361 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Heya, just wanted to clear things up a little! Yes, the Roman Empire did include Egypt after they conquered it, which happened during Cleopatra's reign. She was in fact the final pharaoh as a result, and after her time Egypt was a Roman province for the next six centuries!

Now, this all happened during the 1st century BCE, while the final mammoths went extinct on a distant Siberian island around 2000 BCE, so Cleopatra was not around at the same time as mammoths... But Egypt itself was! In 2000 BCE Egypt was already over a thousand years old, and the pyramids had already stood for 600 years!

Now what that also means is that in 30 BCE when Cleopatra died during the Roman conquest of Egypt, the building of the pyramids was 2600 years in the past... Which is a longer time than the 2054 years between now and Cleopatra's time! Which very much does fuck with the brain.

Reconstruction of bust of Roman emperor Caracalla.

#roman empire#egypt#mammoth#the roman empire is old#but egypt is ribonkulously ancient#vicky's vritings

99K notes

·

View notes

Text

After having suffered and died at Nightmare's hands for so many lives that he can't even remember them all, the Slayer decides to try and start over with her and invite her to dance. It will not lead them anywhere nice. Please be sure to check the content warnings for this one, it's very much a horror story and a lot heavier than most of my writing.

#slay the princess#stp nightmare#stp princess#stp long quiet#stp voice of the paranoid#stp voice of the smitten#stp voice of the hero#stp voice of the cold#stp narrator#stp fic#my fic#vicky's vritings

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

Kiss the Stranger, chapter Two is up! In this one, the Princess uses wonky physics to save Quiet, everyone has a lot of fun underwater until the Narrator tries to get in on it, a lot of important conversations are had, and everyone gets to take a well-deserved nap.

#slay the princess#stp fic#stp stranger#stp princess#stp voice of the contrarian#stp voice of the hero#stp long quiet#stp narrator#my fic#vicky's vritings

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kiss the Princess is six months old today!

Half a year ago, I was stuck in a terribly long car ride, and to deal with the boredom and general discomfort I wrote a little story asking 'What if you could kiss the Razor and she was into it but also bit your face off about it?' I published it on Discord in my hotel that evening, and then on AO3 the next day, and long story short, half a year later I've written thirteen Kiss the Princess stories totaling 123k words! Which, incidentally, makes it the third longest Slay the Princess fic in the Archive if you treat them as a single story.

Said story would also have the second-most hits of any Slay the Princess fic, so needless to say I have been and continue to be blown away by the love you lot show this series. I'm super grateful to everyone who has read these stories, and especially everyone who has let me hear their thoughts about them, because I probably wouldn't have kept going this long without you. I've had such a good time writing this series, and it's definitely a story that grew in the telling. By now we've gone through two full cycles, Shifty dances and all, and I'm hard at work on Kiss the Cage to start the next one with. Getting to put continuity in these stories while also making sure they can be read in any order is actually one of my favourite things about this series.

Lemme just leave you with a little teaser for Kiss the Cage:

#slay the princess#stp fic#my fic#vicky's vritings#yes thank you spell checker a gagged person does indeed not speak correct english

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

It's fascinating to think of how the Cretaceous world would have responded to the climate shifts of the Cenozoic. The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum wasn't that far off and I could imagine it causing issues for the largest dinosaurs - perhaps that's when the tyrannosaur extinction speculated above would happen, but I'm especially thinking of sauropods. In our timeline it only caused a minor extinction event, but then we really didn't have many of the kind of giants that would struggle with it in the Paleocene. Many of the modern mammal groups really came into their own afterward, and while whatever groups of animal became major players would be a complete crapshot, I imagine it would still be a bit of a biosphere turnover, with many of the old giants disappearing and new groups showing up. Perhaps including some (very different from our own timeline, probably not even placental) mammal groups. A reasonable point to call the end of the Cretaceous in this timeline.

Andrewsarchus and Paraceratherium show there was still plenty of space for new giants on land afterward - though of course all of those niches are dependent on how the rest of the biosphere looks, not just on the climate. I imagine mosasaurs would still be going strong in the roles of basilosaurid whales for a while, but may have vanished in the Eocene-Oligocene Extinction Event like those. Perhaps, like in our timeline, massive filter feeders would swim around afterwards as well - a new branch of mosasaur or plesiosaur maybe, or perhaps the whale sharks would be a lot more diverse than in our timeline. Or something truly weird like gigantic ammonites?

The Oligocene and Miocene cooling and spreading of grasslands (though it very well may not be grass but something else entirely in a similar niche) would be the next big event. Herbivores would need to adapt to quite different environments and tougher food. I'd like to think pterosaurs would do quite well with all the new open space. Speaking of flyers, birds would likely still be a major dinosaur group, though our own crown birds would be much less diverse with more niches already filled up. But on the other hand, toothed birds would likely stick around and may be filling some of the bird of prey niches - the ones that aren't taken up by pterosaurs. I doubt there'd be ratites and terror birds in a world with dromaeosaurs and ornithomimosaurians surviving, though.

Finally, the Quaternary ice age cycle leading to modern fauna. Feathers and fur would be a great investment - descendants of dromaeosaurs, in whatever strange forms they have taken by this point, seem like they'd just get fluffier. The ability to migrate along with the rapid climate shifts is also very helpful, I do think there'd still be pterosaurs, though they might huddle around the equator during ice ages.

Finally, a major thing to consider for the entire Cenozoic is that it's a world of separate continents. The cretaceous already saw continents developing their own unique fauna, and that pattern would only be likely to increase. You might see some very odd ones, like a South America where the top predator is a carnivorous hadrosaur that invades North America once the Panama isthmus appears, while Australia ends up with gondwanatherian mammal megafauna.

Pretending End Cretaceous mass extinction event never took place, do you have any thoughts on speculative evolution and how dinosaurs and their contemporaries may have evolved through the years?

Like the explosion of mammal biodiversity probably wouldn’t have taken place, but what else? Assuming other global processes like plate tectonics, and the accompanying changes in currents, oxygen cycles etc, if you only take away the asteroid and it’s direct consequences, how do the dominoes fall?

Well, AFAIK the asteroid wouldn't have had any long term affects on the planet's tectonic activity or the climate. It was an apocalyptic event for sure, but depending on what scientist you believe, the immediate effects of the impact were over anywhere from a couple thousand years to only a few months.

So the plates would still move the way they have in the Cenozoic and the climate would still cool down and dry up due to the Earth's orbit and Milankovitch cycles. There would still be an Ice Age and animals would have to adapt to it.

The main difference would be life of course, and I cannot stress this enough, everything would be different. There would be no placental mammals, plant life would be mostly angiosperms but not in their total domination we see today, teleost fish wouldn't fill almost every aquatic niche like they do today, and of course there'd still be a shit ton of dinosaurs.

The thing about the asteroid was that it basically wiped the earth clean of entire clades, and those vast expanses of open niches is what kickstarted the biosphere we know today. There would be literally nothing in common with our "timeline" if it hadn't hit, except for some extreme cases of living fossils like Triops or Lepisosteus. No Mackerel, no Poison Dart Frogs, no Rose Bushes, no Great White Sharks, no Leopard Slugs, no Bears, no Giraffes, no Komodo Dragons, no Coconut Trees, no Crows or Ravens, etc.

In that sense though, 66 million years isn't that long in the perspective of the Mesozoic, so there wouldn't be anything crazy different from the Cretaceous. I doubt we'd see any dinosauroids for example. There would still be big sauropods and big theropods to hunt them, there would still be pterosaurs and marine reptiles of all kinds, there'd still be Ammonites and plenty of lobe finned fish, etc.

I think it's safe to say the arms race between armored Ornithischians and Tyrannosaurs would fizzle out, and much like the Stegosaurs and Carnosaurs of the Jurassic, they'd go extinct to make way for other animals to take their place. Maybe gigantic dromaeosaurs and quadrupedal ornithomimids or extremely armored sauropods and pterosaurs with bone crushing beaks, the possibilities are endless and I'm sure there's a million speculative evolution projects out there trying to answer that question.

Basically, we wouldn't be here making these posts.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Prisoner and the Slayer both know the Narrator will possess him if he tries to free her. Can they establish trust between them and come up with a plan to outwit the Narrator when He can hear every word they speak?

#slay the princess#stp prisoner#stp princess#stp long quiet#stp voice of the skeptic#stp voice of the hero#stp narrator#my fic#stp fic#vicky's vritings

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's the finale to Shifty and Quiet's long journey together, featuring the Moment of Clarity and the Prisoner. Chapter 2 of Kiss the Long Quiet is here!

#slay the princess#stp shifting mound#stp princess#stp long quiet#stp fic#my fic#vicky's vritings#stp fury#stp damsel#stp thorn#stp moment of clarity#stp prisoner

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

With Her fifth vessel collected, the Shifting Mound awakens and discovers what She and the Long Quiet are. Despite the love that blossomed between them, he has many misgivings about the forces She represents. She must face him and convince him to leave the construct together. Can She and Her vessels convince him?

Have you ever wondered what a Shifty confrontation is like from Her perspective? That's exactly what this story is all about!

#slay the princess#stp shifting mound#stp princess#stp long quiet#stp fic#stp fury#stp damsel#stp thorn#stp moment of clarity#stp prisoner#my fic#vicky's vritings

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay, so I am not all knowledgeable about horses, so take all this with a grain of salt because I'm researching them as I type out this post. But the Wikiped tells me knights generally rode medium-weight horses that weighed around 500 kg, although it's possible particularly heavily armoured knights went for heavy-weight horses in the 680-910 kg range instead. So in order to match their ability to carry a fully armoured knight, but also have solid speed and endurance like a horse, I'm inclined to look for animals around that size. Of course, larger dinosaurs might be used in medieval warfare as well, the same way elephants were, and I could imagine some truly incredible howdahs mounted on a sauropod's back that might function as a whole mobile castle. But a Brachiosaurus is not really gonna be doing the job as a knight's mount. We're gonna be looking at more average sized dinosaurs here.

Looking at some videos of them galloping, it seems horses keep their backs surprisingly still compared to many other mammals while running. If you look at a dog running at full speed, for example, you'll see their spines flexing up and down much more than horses do. Which probably means even hobbit knights would be unlikely to be riding dogs into battle. But this is a field where I think dinosaurs should do the job quite well, as the modern ones keep their backs quite still while running:

Of course, horses are quadrupedal, but with dinosaurs we get to pick between bipeds, quadrupeds, and facultative bipeds like hadrosaurs who could do both. A bipedal mount is obviously going to present both knight and mount with some balance issues, since the mount has to deal with balancing a fully armoured knight's weight on just two legs. A bipedal mount is also going to be more prone to 'rearing up' and probably be more unpredictable in its movements in general. And if you do fall off, it's a longer way to the ground. Careful breeding of the mounts, and much training for both knight and mount would probably be needed to ride a bipedal dinosaur. None of this is to say riding a biped would be impossible, but they're probably not the most likely choice. So let's leave Theropods, Pachycephalosaurs, Ornithopods, and the bipedal early Sauropodomorphs to the side for now. I'll come back and write more about how the more daredevil knights might ride them later.

Speed is a concern, so we can probably eliminate Thyreophora (Ankylosaurs and Stegosaurs). Aside from their speed issues, it'd also be tricky to find a comfy spot to ride them from, with their extremely broad backs (Ankylosauria) and armour plates and spikes. If we also eliminate dinosaurs that are too large or too small, I think we are left with only Ceratopsians and the smallest sauropods, such as Europasaurus. A Europasaurus-mounted knight is quite a cool idea, though I think it's probably still too slow, more like riding a cow than a horse.

So we're left with Ceratopsians, and I think these are probably best suited for a knight's needs. They are strong, sturdy creatures, quite capable of great bursts of speed for short durations at least. They've got sturdy backs that would let you put a saddle on them quite stably (though some may have had quills on their backs). Many of them (though probably not Triceratops) lived in herds, meaning humans could probably step in and use their social behaviour to domesticate them, as we've done with many ungulates. Many of them probably engaged in headbutting, which would help them keep their cool when their rider tells them to charge down an enemy. A cavalry charge where the mounts have horns and protective crests of their own to match the knights' lances and armour would no doubt be absolutely terrifying. Most of their crests were built more for display than protection, their skulls having large windows to lighten them, but that could be fixed with some sort of crest armour. I think the ceratopsians might actually quite like having a big chunk of steel on their crests making them look even more impressive, provided the weight is not too much for them.

Ceratopsians would be a much heavier ride than a horse, though. A Torosaurus (or Triceratops) is much more like an elephant than a horse in size. Even the average-sized ceratopsians, like Styracosaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus, would still weigh in at around two tonnes, since they're much bulkier than horses even if they're about the same height. A Yehuecauhceratops could get you some more manouevrability, but if you go smaller than that your mount is probably not gonna be able to carry a whole knight. And there lies the problem: these are bulky creatures, very capable of doing a sprint, but not very good at running around for a long distance. Ceratopsian-mounted knights would take a long time to get from point A to point B, and they're not going to be outmanouevring infantry on the battlefield either.

If you're looking for a dinosaur mount that's more of a long-distance runner, like a horse, you'll unfortunately end up back at the bipeds with all the balance issues they bring. I'm not gonna go through them exhaustively, but I do wanna highlight a few of the more flashy options. A particularly large Utahraptor would be about the right weight, but since they tended to leap onto prey to use their claws and use their feathered arms for balance, you're in for a very bumpy ride. Air-filled bones might make them more fragile than a knight wants too, and as ambush predators they probably exhaust more quickly than horses do. Other mid-sized theropods might make for more suitable, less jumping-prone mounts, particularly if you can find one that's both a social animal (for domestication purposes) and a pursuit predator (for long distance running). Yutyrannus or Nanuqsaurus, perhaps?

As for bipedal herbivores, most Pachycephalosaurians would be far too small, but Pachycephalosaurus might do a good job, provided it went through centuries of breeding for larger and stronger animals as horses were. Like their ceratopsian relatives, they probably wouldn't balk too much at a cavalry charge, but they'd be a lot lighter and more manouevrable. I don't imagine their battering ram skulls would be nearly as useful as their cousins' horns during a charge, but if you're charging right by the enemy like in a joust they'll probably do a good job. The ornithopods come in a wide range of sizes, with many of the most famous ones being too large for a knight's purposes. They were social animals, and quite capable of running around, but since they'd have to be able to go about on both four and two legs to make full use of their mobility, you'd have to use some sort of modified saddle and probably strap yourself in to ride them properly. Many would come with built-in horns for long-distance communication if you can teach them to do it on command too.

So in conclusion, there's no perfect dinosaurian mount for a knight, but there are a number of decent choices, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. Styracosaurus is a good choice for heavy cavalry charging, while Nanuqsaurus or Pachycephalosaurus will do more for a knight who wants manouevrability and speed.

Which dinosaurs would make for the best knightly mounts?

I'm not a dinosaur kid, so you'd probably be better off asking @we-are-avenger and @we-are-scribe who *are*, and can weigh in better than I.

#dinosaur#paleopet#knight#palaeoblr#ceratopsian#yutyrannus#spec evo#pachycephalosaurus#'just a quick little post off the top of my head' i said#'it'll take me like fifteen minutes and be some fun speculation'#i still don't know anything about horses#and while i know more about dinosaurs some of my information may very well be inaccurate#i'm a paleoartist not a paleontologist#so take this as the fantasy spitballing it is and not scientific truth#vicky's vritings

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Adversary accidentally knocks herself out while fighting the Slayer, and he decides to take care of her rather than listen to the Narrator. How will it affect their next fight?

This one's a double feature, the second chapter with the continuation of the story in Eye of the Needle will be up in a couple days! Content warnings for graphic descriptions of violence and temporary character death, because it's an Adversary story.

#slay the princess#stp adversary#stp princess#stp long quiet#stp voice of the hero#stp voice of the stubborn#stp narrator#stp fic#my fic#vicky's vritings#needle and smitten to come in the next chapter too#you are not ready for the stubborn and smitten team-up

23 notes

·

View notes