#very figures in a landscape (1970) coded

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hazbin Hotel Rewrite [WIP- this is copy and pasted from my docs; this is old but i wanted to share it anyway]

Rewrite the Characters:

Original +opinions (ooo~ Spicy) :

Charlie - Princess of Hell, Daughter of Lucifer. Sheltered and Cheery.

I hate that she’s just Disney Princess coded. They could have used the whole sheltered route well but TBF we don't see that either. We see a weird rendition of that where everyone forgives her for her terrible actions but yet other characters like Husk and Angel Dust are somehow held to a higher sense of accountability for their actions?!

I also don’t believe whoever raised Charlie could keep her away from the ever growing and changing landscape of Hell. Like if you're going to be a Princess of anything its really important for the next heir to be well acquainted with their kingdom's landscape and history. At the very least talk to the locals and commonwealth.

Her design is...ok. It didn't change much from the pilot but tbh i liked her Pilot design, I feel like it makes sense for her to wear hints of red and white, but i wish they added more than just red, i feel like black or gold would have been better or even purple for Biblical accuracy of Pride.

Vaggie - Girlfriend to Charlie and protector of the Hotel, ex-Exorcist.

Why did they change the lore? Also why does it feel like the VA hated being there or was just given 0 directions. She sounds dull and plain except for when she’s sounding like she’s angry, which is 99.98% Of Vaggie’s emotions.

That, an amnesia apparently?! How does vaggie not remember the very weapon that cut out her FUCKING EYE that still makes no sense, like how tf her and Lucifer and even Husk have wings, if wings are going to be used for ANY character why make them seem important to Vaggie when Husk literally has wings, and Lucifer the supposed “fallen Angel” STILL HAS HIS?! Like why? How does this make sense?

Angel - FemBoy, Sex worker. Deals in Self destruction, self loathing and deep depression while also being flirty and promiscuous. Was in a Mafia family. 1940s timeline.

Trauma porn character and just a bunch of gay men stereotypes. As a survivor, his story doesn't hit the way its meant to. There's a good and bad way to show SA and Abuse and while they did it “eh” (im saying this loosely) at first, they were completely unrealistic and downright infantilizing at the end.

There's no way someone who just went through a beating, an having to almost get drugged and dragged out of bar, is going to forgive the same person who started the stupor in the first place- ESPECIALLY ON THE SAME NIGHT!!!!!

I FUCKING CANT WITH THESE WRITERS THINKING MENTAL HEALTH CAN BE SOLVED IN A 20 MIN EPSIODE, IS THIS A KIDS SHOW ABOUT FRIENDSHIP OR AN ADULT SHOW ABOUT CARTOON DEMONS IN HELL.

And don’t get me started on that terrible musical number, it’s just soft core rape in a cheery pop tune i fucking hate it!! It doesn't help that Raph, an SA fetishist STORYBOARDED THE DAMN SCENE

WHAT THE FUCK MEDRANO!?

Husk - Angry grump, bar keeper. Contracted to Alastor. Gambler. From the 1970 or 60.

The design is a character designer's worst nightmares come to life on the screen. Every furry from the early 2000s clutching their pearls in cringe. It screams “omg rawr xD uwu” era and i think we as a society are way past that, i figured a 30 something year old woman would be too.

[apparently it was her sisters OC that was put into the show, viv why?!]

Alastor - radio show host from the 30s. Cannibal. Half Creole. ���Wendigo design”. Cocky and always smile but is "quite dangerous when provoked." [yea ok pal]

An OC from middle school that should have stayed in middle school. There is a reason so many OCs from artists' early childhood don't make it into their new and growing art style. Most of the time if you keep obsessing over the same OCs you stunt yourself on growing in your art. Tumblr Sexy Man is that exact thing. I like him in concept but, if he was drawn better and actually looked like a man from the 1900s and in his 40s,(or even a half creole man; that's supposedly a Wendigo) I'd have less to complain about. His concept is good and interesting, but its not the first or the last and Alastor def isn't the first. Also give that man a haircut please!

Nifty - Japanese-American. From the 50s Obsessive and a neat freak. Camera shy but psychotic.

I feel like this is just a racist stereotype waiting to be exposed. The “young psychotic Japanese girl” trope is so fucking old and repetitive that i cant vibe with a character like Nifty when i know her only purpose is to be used as comedy bait. It doesn't help that Viv didn't give Nifty almost any merch! Like WOW really showing favoritism over the merch sales and that is disgusting.

Sir Pentious - British inventor. Kinda an idiot but is a brilliant machinist.

We were robbed of a decent villain. I hate that he became part of the cast and became the first redeemed as if Angel wasn't there longer and started showing signs of Redemption sooner, like we got more Redemption scenes of Angel but like NONE of Pentious and we are supposed to believe this weird snake dude is redeemed just cuz he kissed a girl and got himself killed for nothing???? VIVZIE YOUR ASS WRITING IS ASS!!

Also he's a stolen Character...seems to be a trend for Viv..

Lucifer - King of Hell, Father of Charlie, Sin of Pride. Depressed and non-serious, deep self loathing. Complex of some sort. Short King.

He’s fine..i guess, i mean its freaking Jeremy Jordan VA-ing him…he kind fixes whatever is wrong with Lucifer character wise. [this is for very obvious reasons a joke, while re-reading this i realized some people might not know i'm being sarcastic,oopsies] He’s a terrible character for numerous reasons. He is kinda homophobic if you really think about that “i like girls too” line and then proceeds to call her “MAGGIE”; Lucifer feels like he is just there to satisfy Viv’s disney esque “daddy issues” type kink she has for “tragic characters and shitty dads” type characters.

Designs wise he trash. He looks like jeff the killer but blonde and drawn by your aunt who refused to go to art school

Cherri Bomb - Angels Friend. Arsonist. From the 60s(?). Punk rock.

Her design is literally traced and just the Addict design…the fans are just stupid. Also i dont like the fact that Viv EXPECTED viewers of her show, to have done homework on who the fuck Cherri is, cuz if you're a new watcher, and didn't read the fucking Vivziepop Bible, you wont know who tf she if or why you should even care about her.

Why is Angel hanging out with someone like this in the first place, You’d think because Angel is older and from a different time period he wouldn't vibe with Cherri?? But apparently Viv thinks a fem gay man from the 30s would be the best homie to a 20 yr old punk rock Aussie from the 60s, a whole 3 decades of time difference!! Tell us why and how they know each other!! How can these fundamentally very different people even vibe together!! Is it just cus "wow shared trauma of abusive lovers" cuz wow Viv.

(her entire design is also stolen soooooo~)

Mimzy - who?

This one also feels really fucking racist. Idk what it is with Viv but the jewish stereotypes of Mimzie are absolutely atrocious.

Fix:

Charlie - [TBD]

Vaggie - [TBD]

Angel - [TBD]

Husk - [TBD]

Alastor - [TBD]

Nifty - [TBD]

Sir Pentious - [TDB]

Lucifer -

Was an Angel with dreams, and took part in the Creation of All Things.

However Lucifer was too ambitious and went off course with the designs of Earth’s creatures, causing the other Angels to feel uncomfortable by him and his new creations.

While the Angels were tolerating him, he was allowed to visit the First Human, but in doing so felt that their lack of knowledge was unfair and so in hopes of helping the other Angels see things his way, he gave the Apple of Knowledge to Adam and Lilith.

This didn't go as planned though, Where Lilith became kinder and more empathetic, Adam however became more uptight, and acted as if he was better than Lilith.

Lucifer defended Lilith against Adam thus causing the Angels attention to be drawn. Seeing what Lucifer had done; Ultimately bringing evil (free will) into the world, They (strangely) cast Lucifer AND Lilith, as well as the creatures Lucifer had created to the dark void;

The Angels now would call it, Hell. Lucifer, home.

Lucifer would first land in Hell confused and depressed, Along with Lilith they both begin to freak out as they look into the dark, empty landscape in front of them. Feelings of bitterness begin to reside within Lucifer, that settled into a resilient sense of ignorant Pride.

Lucifer’s Creations -

The demons and most of the Hellborns. Lucifer is treated as the Divine Judge of Hell, His punishment is having to witness all the evil that had been created due to him and He in turn must turn what could never be, into another one of his creations. Though he is given it a process. He has given up on making anymore Hellborns due to them fixing that themselves. Demons that are specifically Dead Humans (The Sinners).

Sins -

All of the Sins were once creatures created by Lucifer that began to Form into The 7 Deadly Sins. However the rest of these creatures evolved into lower ranks and a hierarchy was formed. With the Sins and Lucifer being at the top.

The 7 are special creatures that Lucifer held a special fondness to in particular. More so than some of the other Creations. Each of these Sins were given a mission after the fall and were subsequently turned into the Sins by the Angels, who felt they deserved the same punishment, if not worse, as Lucifer. Forcing each of the Sins to work as their prince/princess of their specific ring unless they want their entire existence to cease. They rather that not happen.

The angels cursed all the sins, and Lucifer himself. that if they ever stop their torment they will cease to exist. Angels thought this was humane but didn't realize or rather didn't care that much at the time how barbaric it actually is.

Dubbed the Curse of the Angels or Angels Kiss

(play on Kiss of Death where whomever Death kissed is marked for death,

here the Sins were “kissed” by the Angels and a “kiss” was once used to symbolize a curse or bad omen onto another)

their "death" however is more than they evaporate into nothing

its their very minds and bodies slowly begin to deteriorate painfully to the point of being empty husks. No expression, No emotions, No sense of self. Nothing. Their consciousness and personality essentially gets erased entirely.

Premise IDEAS for Rewrite:

1]

Sinners go through character arc delving into their issues that lead to each one's Redemption

Heaven gets upset over the rise of redemption in Sinner

Earthly Denizens of Heaven/ “winners” attack the Hotel

The Sinners and the Staff defend the Hotel

Heaven’s attackers are turned fallen.

{END}

so i started this almost a year ago, it was right when i really started to dislike Viv and Helluva Flop Boss. If you wanna give a suggestion on what you think could make this better go for it. It's a WIP- so any advice is welcome and appreciated!!

#this is an old draft#hazbin critical#anti hazbin hotel#vivziepop critical#anti vivziepop#im still working on it

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Super Heroes ARE NOT INHERENTLY a Conservative power fantasy

Master Post

I don’t really agree superheroes are inherently a Conservative power fantasy nor that they simplistically preach law and order and justice are necessary for a happy ending.

After all Superman was fighting corrupt politicians in his very first appearance. The X-Men are institutionally persecuted often by government forces. Stan Lee did an entire story arc in refutation to Law and Order politics in the early 1970s.

Yeah, they hit people to save the day but like...I honestly think that’s far more of a human power fantasy than something of any specific ideology. There have been examples of mythic and folklore figures doing that since forever. The broad appeal of those types of characters throughout history and across political ideologies speaks to how it’s not inherently a political power fantasy of one type or another.

I know someone who is incredibly Liberal and has himself and people he’s known been persecuted by the police and he’s outspoken against such institutional persecution. He loves Daredevil and more poignantly the Punisher, a character outright adored by the police themselves but who is near universally framed (even within his own stories) as not a good person and someone you shouldn’t aspire to be like. This was even the case in his debut in Daredevil season 2 where it was made explicit that he is self-destructive.

Obviously my friend would be disgusted by the Punisher in real life, as would we all (I’d hope). But the fantasy is still unto itself appealing despite it conflicting with his ideologies. Hence super heroes are not a power fantasy rooted in a specific political ideology. Now sure that is one anecdotal piece of evidence. But the Punisher is clearly very, very popular and the degree to which he is popular (especially in the 1990s) wouldn’t really add up if his fanbase were predominantly Conservatively leaning people with the occasional Liberal exception.

He’s very obviously a character people of either leaning or in-between enjoy and was after all created by an outspoken young Liberal in Gerry Conway. Batman too is often perceived as very conservative. But he is the most popular superhero ever so he obviously appeals across political ideologies. After all, the two most defining Batman writers (after Bill Finger) were the incredibly Conservative Frank Miller and the incredibly Liberal Denny O’Neil.

I also don’t think super heroes are analogous to stand your ground myths. For starters, super heroes are not enshrined by the law. The closest comparison you could draw is if you encountered a clear cut crime in progress and intervened non-lethally somehow. E.g. that scene in Spider-Man 2 where Peter Parker walks away from a mugging in progress, but for the purposes of what I’m saying actually tried to intervene.

I once received counterpoints to the above view that went something like this:

You are extrapolating specifically European myth created by white males and applying it to all humans. African myths are different. Native American myths are different. Asian myths are different. You’re making my point that comics are a dominant conservative culture - specifically white male - fantasy, not refuting it.

Actually I wasn’t. There examples of such figures in Eastern myths too such as Sun Wukong. Son Goku is a 1980s manga character based first and foremost upon him (and Jackie Chan) and is a veritable institution in Japan. There is a vast crossover between fans of him and fans of other superhero characters despite him not being directly based upon any of them, having distinctly Eastern cultural influences and also not being a crime fighter in the traditional sense.

Goku in truth is probably more comparable to figures like Theseus in spite of not being based or influenced by him. African myths and European myths may be different but most cultures involve figures who have beyond human abilities and among those figures those who engage in actions that, within the values of those cultures, are regarded as good. All human beings are innately attracted to stories that in one shape or form present them as physically more powerful than they are, a by-product of more innate survival instincts. On our absolute most deepest levels we are animals and because of this the fantasy of being stronger, faster, less vulnerable to injury or malnutrition and/or having the ability to defend our homes/territories/family units (which in superhero comics is usually extended to the general population of a native city) is incredibly potent and attractive.

The counter pointer continued:

“It’s not a female fantasy. Women tell very different myths, most of them lost because men wrote down the stories. The romance genre is dominated by female writers because those are the stories women are drawn to tell.”

Given the vast plethora of female fans of the genre from 1938-now I really do not see how we can honestly say this is a genre that is particular to the power fantasy of one gender or another. Wonder Woman was after all a distinctly female power fantasy created with a lot of input from two women very much ahead of their time.

But going into another culture Sailor Moon (and her predecessor Sailor V, who was more of a traditional crime fighter) was arguably even more of a female power fantasy. She was the singular vision of a female mangaka who was aiming at a young female audience and was very specifically creating a female power fantasy. In both cases they are people with secret identities who engage in physical violence to varying degrees against very clearly coded evil individuals who pose direct threats to innocent lives.

Now about the gun debate? Well, most superheroes use guns?

But for the sake of argument let’s extent ‘guns’ to mean stuff like:

Ray guns

Web-shooters

Firing concussive energy blasts, like Cyclops’ optic blasts

Any kind of projectile

Well, even if you define guns like that, the majority of superheroes’ weapons are non-lethal whereas guns are designed specifically to kill. Yeah you can wound or incapacitate but gun wounds can still be lethal or crippling. Plus you could in theory kill someone with a net but that wasn’t what it was designed to do.

Things get iffy if we count biological weaponry, like in Cyclops’ case. Whilst his super power is literally having a powerful gun for his eyes, it’s also part of who he is and he’s got no choice in that. This changes the context drastically from someone who owns a gun and seeks to use it.

In Cyclops’ case he’s forced to own that weapon and it’s an immense burden upon him . It curtails his ability to have physical and emotional intimacy with others the way anyone else would. I anything I’s more analogous to a disability. So it isn’t like this is a wonderful fantasy about how cool it’d be to own a big gun without the burden of choosing to own it in the first place

That doesn’t even make sense considering the real issue regarding American gun laws ultimately isn’t about people merely owning guns but how they use them upon owning them. Cyclops still has to choose how to use his biological ‘big gun’ even if he didn’t get a choice in owning it one way or the other. It’s also a poor analogy considering Cyclops’ ‘Big Gun’ doesn’t even work properly due to a disability he has.

In fact, it’s posited superheroes are needed, especially vigilante heroes like Spider-Man who take law enforcement into their own hands despite being outside the law enforcement establishment, because the Marvel U is a dangerous, violent place. This is very similar to arguments used by conservative gun advocates in the US: we need guns to protect ourselves because our institutions can’t. Moving on let’s talk about the severity of crime. Is it not a Conservative power fantasy that the world of Marvel and DC comics is a dangerous and violent place? And therefore vigilantes who take the law into their own hands are needed?

That’s kind of similar to what Conservative gun advocates argue isn’t it? Guns are needed to protect one’s self.

Well for starters, the nature of the severity of crime is questionable in most Marvel or DC comics sans like Batman. It is made clear that superheroes absolutely do good but at the same time it wasn’t presented as though there was such a massive crime problem that say Marvel New York would’ve fallen apart without them.

That is exempting of course super villains.

Super villains however are cut from the same fantasy cloth as the heroes so how much to they really count towards representing real life concerns over crime anyway? They were after all literally created as a means to challenge the heroes. Action Comics #1 for example didn’t have any super villains.

Similarly modern interpretations of Batman do not seek to present the world or urban landscapes in general as inherently so riddled with dangerous crime that it necessitates Batman. They make it clear that Gotham is this extreme exception as opposed to the rule. Greg Rucka once spoke about this in an old documentary (for I think the History channel).The idea is that Gotham is exceptionally bad thus they need Batman.

In most versions of Superman post-1987 Lex Luthor has such a stranglehold on Metropolis that it needs Superman. And in Golden Age versions of Superman he was presented as just tackling general urban crime that existed amidst the Great Depression, most of which stemmed from organized crime or corrupt political figures. But it wasn’t as though Metropolis was on the brink if not for Superman’s intervention.

Really the levels of crime and such that exist in superhero stories exist purely to justify a superhero being a crime fighter in the first place; it’s a practicality issue not an ideological one. I think this is different to say police TV shows or films that present characters who allegedly exist in the real world, who represent real world police officers who do a real world job that involves them interacting with allegedly real world threat levels. In a superhero story, of course t here is more crime that actually exists in the real world but I don’t think anyone making the stories ever honestly thought otherwise or paid much thought to it one way or the other. It was just a means to an end of challenging the protagonists.

Okay, but how about the fact that heroes rarely (if ever) calling for gun control or gun bans? Surely that is a Conservative.

Well no not really. Again, it’s not really an ideologically driven factor in super hero stories. It’s more akin to how superhero comic books just do not touch for example the issue of abortion or how they rarely make it truly explicit what political leanings a character has one way or the other.*

John Byrne when discussing his iconic Superman run stated he felt the character was a card carrying Republican, but to the best of my knowledge no Superman comic before or since has ever come out and said that. No Punisher story to my knowledge has ever stated Punisher is a Conservative in spite of the fact that he obviously is. No Spider-Man story has stated Spider-Man is a Liberal/left leaning moderate. And yet he has been depicted that way in most stories and it’d just be incredibly likely given his age, where he lives and his family background. I don’t even know if any Captain America story has stated clearly and without question that Cap would obviously vote for the Democrats 100% of the time out of the two major parties, even though he was explicitly Liberal from the very first piece of artwork depicting him. In ne of Bucky’s early adventures as Captain America though he simultaneously protected Democrat and Republican politicians.

So whilst superhero comics do not involve characters calling for the abolition of guns 99% of the time, that’s less because they are or are not a Conservative power fantasy and more because the companies do not want to touch what they at least perceive as an incredibly volatile issue.

If the gun debate in America (which to me shouldn’t even be a debate, just get rid of them) ever moves to a place where there is virtually nobody opposing the abolition of guns most superheroes would absolutely be depicted in support of that.

To strip back everything I’m saying, super heroes are intended more on, and consumed more on, a symbolic level than something in line with a particular ideology.

They are vigilantes who fight crime. But it’s understood that the crime is in the story simply because it is universally understood as ‘a bad thing’ that can cause harm and damage. The superhero is you. You being a vigilante symbolises how you have to on an individual level deal with a problem, the ‘bad thing’.

And the super powers are the catharsis of how much easier it would be to deal with the ‘bad thing’ if you were more than what you are.

I don’t agree with 100% of this, but this video (which is interesting unto itself) touches upon this idea around the 15:30 mark.

youtube

It’s not as though a Liberal enjoys the genre for the escapism or the perverse indulgence in politics they wouldn’t agree with whilst a Conservative just loves it’s reaffirmation of their beliefs.

They love it for the same reasons and those are usually rooted in the human elements of the characters alongside the power fantasy. Which is why I maintain there is an innate human appeal to the genre regardless of what perspective you come at it from.

I mean Jesus, if we are really going to argue that superheroes are a Western Conservative power fantasy why have countries with anti-Western values, countries that American Conservatives are heavily in opposition to, devoured the genre on film?

Why is the MCU outright beloved in China?

Why have they tried to create their own super heroes in a similar vein?

Because these characters are not a Conservative, or a white, or a male power fantasy. They are just a human power fantasy.

*And contrary to what people who are hardline on one ideology or another think, not opposing an issue isn’t tantamount to supporting it. Neutrality exists. If you support abortion that’s Liberal stance on the issue. If you oppose gun control that’s a Conservative stance on that issue. If you do not care about them one way or another you ware not expressing a Liberal or Conservative view point.

The whole ‘With us or against us’ viewpoint is absolutely myopic and overly simplistic. By this logic America was supportive of Hitler before they joined the Allies in WWII. But they were also supportive of the Allies because they weren’t supporting the Axis powers either.

Neutrality can exist.

#MCU#marvel cinematic universe#Marvel#Marvel Comics#DC#DC Comics#Superman#Batman#John Byrne#Cyclops#Scott Summers#X-Men#Bruce Wayne#Clark Kent#Frank Miller#Denny O'Neil

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

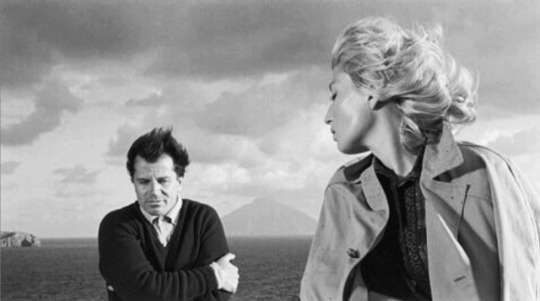

why should we be here talking, arguing? Believe me Anna, words are becoming less and less necessary; they create misunderstandings

eclisse inspirations, vol. IV Michelangelo Antonioni’s Trilogy of incommunicability part. 1 - L’avventura, 1960

When Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura arrived in 1960 – amidst a tumultuous reception in Cannes that saw some disturbed audience members wanting to throw something at the screen – cinema was already changing in fundamental ways. The makers of individual, handmade films that had been institutionally kept out on the fringes (Stan Brakhage, Shirley Clarke, Norman McLaren, to name but three) were starting to draw more viewers and critical attention. The narrative feature film underwent a revision, from inside the nouvelle vague (Godard’s Breathless) and out (Agnès Varda’s first films, Alain Resnais’s Last Year in Marienbad). Meanwhile the Italian film world had already seen the old codes of neorealism swept away – much of it Antonioni’s own doing – and had moved towards a post-neorealist cinema liberated from melodrama and political ideologies, perhaps best exemplified in 1959 by Ermanno Olmi’s first feature Time Stood Still.

A new, maturing modernity became widespread in cinema. The years 1959 to 1960 can be identified as a world-historical moment for film. In line with the development of lenses, film stocks and new and smaller cameras (including a more ubiquitous use of 16mm), the modernism that took hold showed yet again the time lag after which cinema typically comes to embrace changes that have occurred first in other artforms: for instance, the radical overhaul of jazz by bebop; the transformation of the sound world of music by such figures as Edgard Varèse and Harry Partch; the abstract-expressionist movement in painting from Pollock to Rothko; the ‘new novel’ invading literature (on which Marienbaddrew, courtesy of a script by novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet).

In this exceptional moment, some of cinema’s old props were being kicked away, including Hollywood’s genre formulae, the three-act narrative structure, the privileging of psychology, the insistence on happy and ‘closed’ endings. But what did it mean to free oneself of the securing laws and traditions of genre, its capacity for creating worlds and codes? What did it mean to reject a storytelling architecture that had served dramatists well since Aeschylus? What kind of moving-image experience with actors could exist beyond psychology – which, after all, was still on the 20th century’s new frontier of science and society? What if endings were less conclusive, or less ‘satisfying’? These are the questions Antonioni confronted and responded to with L’avventura, the film that – more than any other at that moment – redefined the landscape of the artform, and mapped a new path that still influences today’s most venturesome and radical young filmmakers.

For some that film would instead be Breathless. Godard’s accidental discovery of the jump cut (courtesy of his editor) helped him rejig a more conventional yet sly imagining of the crime movie into a piece of radical art, a way of fracturing time as important as Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubist fracturing of space and perception. It’s also arguable that Godard had the more immediate impact, especially through the 1960s, since his taste for pop-culture iconography, graphic wordplay and politics positioned him a bit closer to the centre of the period’s cultural zeitgeist than Antonioni (despite the Italian’s subsequent ability to capture swinging London and The Yardbirds in 1966’s Blowup, and Los Angeles counterculture in 1970’s Zabriskie Point). Even a movie with huge pop figures and crossover attraction like Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964) would have been unthinkable without the example of Godard.

Yet I’d argue that L’avventura and Antonioni’s subsequent films – perhaps most importantly L’eclisse (The Eclipse, 1962) – have exerted a greater long-term impact (his effect on the generations after the 1960s is something I’ll consider later). One of L’avventura’s many remarkable qualities to note now is its staying power – its ability to astonish anew after repeated viewings. Many great films are of their moment, yet lessen over time. Here, the entrance of Monica Vitti, with her classically hip black dress and sexily tousled blonde mane, amounts to an announcement that the 60s have arrived; a lesser work with her in it would be no more than a key identifier of that moment.

It’s the film’s subtle straddling of an older world and a new one still in the process of defining itself – reflected immediately and perfectly in composer Giovanni Fusco’s opening title theme, alternating between nostalgic Sicilian strummings and nervous, creeping percussive beats – that establishes its rich, unending landscapes of physical reality and the mind. This is part of the film’s timelessness, within an absolutely contemporary / modern setting. The early images of L’avventura trace a parting of the generations, as Anna (Lea Massari) – seemingly the film’s central character – tells her wealthy Roman father that she’s going away on a holiday to Sicily with girlfriend Claudia (Vitti), then seen very much on the periphery of the action, tagging along. But after Anna inexplicably disappears during a boat trip to an uninhabited island, it is Claudia who moves to the centre of the narrative – and into the affections of Anna’s architect boyfriend Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) – as attempts to find Anna gradually peter out.

What makes L’avventura the greatest of all films, however, is its assertion, exploration and expansion of the concept of the ‘open film’. This had been Antonioni’s great project ever since he started out as a filmmaker after an extremely interesting career as a critic (like Godard). His early documentaries, such as The People of the Po (Gente del Po, 1947), and his earliest narrative films, such as the astonishing Story of a Love Affair (Cronaca di un amore, 1950), suggest an artist pulling against what he perceived as the constraints of neorealism towards an openness based on a heightened perception of constant change – a dynamic that was for him the fundamental quality of the post-war world.

A NEW QUESTION

For Antonioni, the issues of neorealism were essential, in that they gave him an aesthetic base from which to launch. The People of the Po is an early neorealist work, both in its submersion in unvarnished realism and its interest in the lives of working people, but it also works against the predominant tendency in neorealism to project sympathy and sentimentality. By the time of Story of a Love Affair, teeming with characters from the upper and middle classes, his was not a class-based cinema; it offered instead a broader perspective – observant, distanced, occasionally unsympathetic. It reached into a more modern realm than neo-realism, a realm that had no name for it – and in fact still doesn’t.

Antonioni was never a leader – nor even part – of a movement. That’s partly because with each successive film he constantly redefined his approach. Roland Barthes, in his profoundly perceptive and concise 1980 speech honouring Antonioni, identified the process this way: “It is because you are an artist that your work is open to the Modern. Many people take the Modern to be a standard to be raised in battle against the old world and its compromised values; but for you the Modern is not the static term of a facile opposition; the Modern is on the contrary an active difficulty in following the changes of Time, not just at the level of grand History but at that of the little History of which each of us is individually the measure. Beginning in the aftermath of the last war, your work has thus proceeded, from moment to moment, in a movement of double vigilance, towards the contemporary world and towards yourself. Each of your films has been, at your personal level, a historical experience, that is to say the abandonment of an old problem and the formulation of a new question; this means that you have lived through and treated the history of the last 30 years with subtlety, not as the matter of an artistic reflection or an ideological mission, but as a substance whose magnetism it was your task to capture from work to work.”

L’avventura builds on the work and experiences of Antonioni’s previous decade, which saw him working through his doubts about genre (film noir in Story of a Love Affair, backstage drama in La signora senza camelie, 1953); about narrative form (the counter-intuitive three-part structure of I vinti, 1952); his love of writer Cesare Pavese (author of the source novel for 1955’s Le amiche) – as important a literary voice to Antonioni as Cesare Zavattini was to the hardcore neorealists. And add to this his growing interest in temporality, the emptied-out frame, the composition that maintains both precision and an expansive gaze that treats bodies, buildings and landscapes with equal importance.

With only a few filmmakers (Mizoguchi, Renoir, Dreyer, von Sternberg, Resnais, Olmi, Kubrick, and more recently Costa, Alonso and Apichatpong) is there such a visible, constant seeking of artistic purpose through the process of each successive film – a striving, a refinement. Antonioni’s 1950s work represents one of the most fruitful directorial decades to watch of any filmmaker. Already in some ways a master in 1950, he proceeded to question his own positions with each film, as if the doubts he had about the state of the post-war world resided, originally, in himself, and then fanned out to the making of the work itself, so that the expression of mortality (most explicitly conveyed in a Pavese adaptation such as Le amiche) inside the film was part and parcel of the director’s own tentative stance. (Tentato suicido/Tentative Suicide is the title of Antonioni’s segment in the 1953 omnibus film L’amore in città.)

These were not only cerebral matters – though the intellectual currents running underneath these films and under the neorealist movement preceding them were crucial to their fecundity – but real concerns rooted in the hard factors that faced any Italian filmmaker trying to get a project off the ground. Antonioni’s tentativeness – a constant fascination to his supporters in the French critical community, and an irritation to many of his Italian contemporaries – was partly based on the tentativeness of Italian film production itself. In almost no case during the 1950s did he encounter a smooth pre-production, firm financial backing or drama-free production periods. The typically poor performance of his films at the box office did little to enamour him to distributors and producers, though in the then nascent world of the auteur film business, it helped enormously that his films did well – even smashingly well – in Paris.

After the commercial failure of Il grido (1957) and an initially limp critical response, Antonioni seriously considered abandoning the cinema altogether, and returned to the theatre, where he had worked in the early years of his career. Even when he did come back to film, to shoot L’avventura, all of his worst concerns came back to haunt him. Already shaky producers bailed out mid-shoot as their company, Imeria, went bankrupt, leaving the crew literally high and dry on the desert island of Lisca Bianca, without sufficient food and water, in a hair-raising episode that makes Coppola’s misadventures filming Apocalypse Now in the Filipino jungle sound like a stroll on the beach.

SURPASSING MYSTERIES

This context, in all its intellectual and practical dimensions, is crucial to comprehending the massive achievement that L’avventura represents. How a film of such constant perfection could even be made under such dreadful conditions is, for me, one of the surpassing mysteries of film history. Viewed in isolation (and aren’t almost all films, even more now in our isolated viewing environments?), L’avventura can superficially be seen as magnificently beautiful in its constant chain of stunning black-and-white images from cinematographer Aldo Scavarda (with whom Antonioni had never previously worked, and never would again).

L’avventura is populated by good-looking actors oozing sex appeal. Monica Vitti, for one, had never had a starring film role before, but with her smouldering presence it was she – as much as Sophia Loren or Ingmar Bergman’s ensemble of intelligent and worldly actresses – who set the standard and the look for the new, sexualised European movie star that was key to the successful foreign-film invasion that hit English-language shores (and was perceived as such a threat by LBJ and his White House crony Jack Valenti that they set up the American Film Institute as a nationalist bulwark against the foreigners supposedly taking over US cinemas). For New York downtown hipsters, London cosmopolitans and Paris cinephiles alike, the combination of serious cinema and sexual beauty was simply too much to pass up.

All that may be why L’avventura had its immediate impact. (A special jury prize from Cannes, after all that booing and hissing, also didn’t hurt.) But the endurance of the film, residing crucially in its conceptual openness, describes a pathway that cinema has been exploring and testing ever since. Much as Flaubert’s novels and Beethoven’s symphonies, concertos and string quartets are continually regenerated by way of the new directions they paved, and the new generations of work following such directions, so Antonioni’s work – and L’avventura in particular – is regenerated by the subsequent cinema that came in its wake.

As Geoffrey Nowell-Smith observes in his essential study of the film, the periphery in Antonioni is of absolute importance, for this is where the sense of drift in his mise-en-scène and narratives resides – a de-centred centrality. No filmmaker before Antonioni, not even the most radical visionaries like Vigo, had established this before as a part of their aesthetic project. In the early scenes when Anna visits Sandro, or when they join their holiday boating group, Vitti’s Claudia remains for a long time on the outside looking in, marginalised, seemingly unimportant. And yet there is something in her nervous gaze, her subtle physical gestures, that makes her impossible not to notice, especially in contrast to Anna’s inner tension and outward unhappiness – an unhappiness she can’t identify, even in private to Claudia.

These are most certainly not Bergman women, forever examining themselves, forever able to articulate the exact words in whole spoken paragraphs about their state of mind, their relationship with God. For one thing, in Antonioni, God doesn’t exist. The state of the world is one of humans searching for some kind of connection amidst a disinterested nature; the island on which the floating party lands is both exotically remote and barren, like a volcano frozen during eruption. The landscapes in L’avventura have been interpreted in a number of different ways that testify to the film’s Joycean levels of readings: from Seymour Chatman’s insistence on metonyms for his reading of what he calls Antonioni’s “surface of the world”, to Gilberto Perez’s more valuable view of the work in his extraordinary film study The Material Ghost, across a whole range of possible interpretations, from the literary to the visual. For me, however, it’s always tempting to see these people – on this island, at that moment – as the last humans on earth.

In L’avventura, more than any film before it had ever dared, the centre will not hold. The open film is a fluid thing, pulsating, forever changing, shifting from one centre to another, not quite beginning and not quite ending (or at least beginning something new in its ‘ending’). Anna, the centre, vanishes, with no visual or verbal clues to trace her by, except rumours of sightings. She was in effect the glue that held the party together, having helped bring Claudia in closer to her circle of friends – and to Sandro. But with Anna’s disappearance, the film alters shape in front of us; a sudden absence actually expands the film’s eye. Individual shots become more extended and prolonged, the sky and land grow larger, the elements become more tangible (clouds, rain, harsher sun).

HERE AND NOW

What’s even more disturbing is that nothing happens – no discovery, no evidence, no detective work and, finally, no memory. L’avventura is, in part, the story of how a woman is forgotten, to the extent that long before the film is done, Anna is less than a trace on a page, a ghost or a photo in an album. A more sentimental filmmaker or a Hollywood studio would have ensured that Anna lived on through Claudia and Sandro’s love affair and possible union. But here, after a while, they don’t speak of Anna anymore. She gradually fades, which is what happens to the dead as regarded by the living (not that Anna is necessarily dead; the film neither encourages nor discourages the suggestion). Although their joint actions ostensibly trace an effort to collect any information on Anna’s whereabouts, Antonioni suggests that the activity of Claudia and Sandro isn’t nearly as important as their time together in this moment, in this or that place.

About those places. The greatness of L’avventura is multivalent, situated in many realms at once: cinematic, aural, existential, literary, architectural, sexual, philosophical – all of them of equal importance. The open film, beyond its fluidity, is amoral in the best sense, or at least unconcerned with a hierarchy of values. Almost all films of any kind privilege certain artistic values above others, and the great ones do it for several: Singin’ in the Rainhonours the body, the sounds of showbiz, the fresh memories of Hollywood at its height; Vampyr celebrates the psychological effect that optical dislocations have on the viewer’s psyche, the spiritual possibilities of the horror film, the blurry line between genres and those alive and dead.

But L’avventura marks a new kind of film, not made before, in which the story that launched the film dissolves and gives way to something else – a journey? a wandering? – that points to a host of possible readings beyond what mere narrative allows, and yet at the same time is too specifically rooted in a form of acting – in situations, episodes and events – to ever become purely abstract. (Though this was an area Antonioni did address in various ways, including the semi-apocalyptic ending of L’eclisse, the visualisations of madness in 1964’s Red Desert and the slow-motion explosion near the end of Zabriskie Point.)

For Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, “L’avventura is a film about consciousness and its objects, the consciousness that people have of other people and of the environment that surrounds them.” It is a film that’s also about a change of consciousness – what that looks and feels like: for instance Claudia’s move from the edges to the centre and, in the final passages, back to the edges. This change of consciousness is realised in terms that encompass Antonioni’s grasp of a vast range of materials: Sandro’s relationship with architecture is framed with the couple’s bodies, both above buildings and nearly swallowed up by them, their shared sexuality first shared in open space and then further and further contained within smaller rooms; the sense of new possibilities (new towns, new relationships) seen in the curve of a highway, a train hurtling down the tracks and through tunnels; the insistence on the Old World in the hulking presence of churches, formal dinner parties, rigid bodies against Claudia’s free and easy one, always in motion; the sounds of creaky nostalgic ‘Italian’ music against Fusco’s disturbing atonalities and unnerving syncopations (in one of the greatest film scores ever written).

Antonioni, as Perez often notes, infuses his cinema with doubt – a doubt that extends to his questioning of psychology as a basis for cinematic drama (let alone his doubt in the value of cinematic drama). But doubt is not an end point in this or his other films; instead it represents the beginning of new possibilities. Thus the open film’s mapping of changes of consciousness – through the tools of mise-en-scène, temporality, elliptical editing, a matching of sound to image combined with a de-emphasis on actors’ faces presiding over scenes (close-ups are fewer by far in L’avventura than any of his previous films) – is a picture of a post-psychological topography of the human condition, a radical effort to find a cinema grammar to express inner thought with photographic means.

This is a map that did (as Perez has noted) go out of style for a time, perhaps during the period of postmodernism, and definitely during the period when Fassbinder ruled the arthouse. But the map has been opened again by a new generation. Its influence can now be seen in films from every continent – to such an extent that the Antonioni open film can be said to be in its golden age. Here are some examples: the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, from Blissfully Yours to Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives; Lisandro Alonso’s La libertad through to Liverpool; Uruphong Raksasad’s Agrarian Utopia; C.W. Winter and Anders Edström’s The Anchorage; Ulrich Köhler’s Sleeping Sickness; the entire so-called Berlin School, of which Köhler is a part; Albert Serra’s Honour of the Knights and Birdsong; James Benning; Kelly Reichardt; Kore-eda Hirokazu; Ho Yuhang’s Rain Dogs; Jia Zhangke’s Platform and Still Life; Li Hongqi’s Winter Vacation. The list goes on…

Some of these filmmakers may disavow any Antonioni influence – but we know that what directors (including Antonioni) say about their films can’t always be trusted. Besides, the ways in which L’avventura works on the viewer’s consciousness are furtive and often below a conscious level. In Apichatpong’s fascination with characters being transformed by the landscape around them; in Raksasad’s interest in dissolving the borders between ‘documentary’ and ‘fiction’, or the recorded and the staged; in Alonso’s precision and absolute commitment to purely cinematic resources and disgust with the sentimental; in Köhler’s continual refinement of his visualisation of his characters’ uncertain existences; in Reichardt’s concern for what happens to human beings in nature – especially when they get lost: in all these and more, the open film is stretched, remoulded, reconsidered, questioned, embraced. A kind of film that was first named L’avventura.

[by Robert Koehler, from BFI. November 2016]

#eclisse#filmmaking#filmproduction#cinema#arthaus#michelangelo antonioni#monica vitti#italy#tumblr#artists on tumblr

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://travelonlinetips.com/best-activities-to-explore-in-the-philippines-for-travel-lovers/

Best Activities to Explore in the Philippines for Travel Lovers

There is an unimaginable range of activities and travel-related things for a travel lover to explore in the Philippines. So much so that more you will read about the places and its attractions, the more confused your mind will become about the sorting out a travel itinerary of choice. When one gets too many good things to digest at once, this is always insisted to be selective and thorough rather than getting a piece from whatever you can. A piece won’t let you enjoy the taste while it does ruin in your dinner, on the other hand, you would miss out on many options when you will selectively pick just a few options but at least, you will be ensured of enjoying to the fullest and your heart’s satisfaction.

Similar kind of situation awaits every traveller while visiting a country as diverse as the Philippines. With more than 7000 islands and all being tropical paradise in their own right, you are prone to get confused. So rather seeking it all, go for the limited but the most unique ones that the place has to offer. For your help, we have figured out a few activities that you would surely love to explore as a traveller in the Philippines. You can simply choose the best Travel Deals to the Philippines using Klook Promo Code or Klook Voucher Code to avail exclusive rebates on your bookings.

Wander Around Banaue Rice Terraces

The tourist destination and rice terrace do not seem to go in the same flow for many people but you will be in no doubt about the synonymous meaning of Rice terrace once you wander around the beautiful landscape of Banaue. This place is impeccably crafted by the local farmers who were forced to develop a farming technique to grow food for themselves and their families amidst the mountainous and hilly slopes. Some geological studies have revealed that these terraces were prepared by the farmers around 2000 years back which obviously means they did it all by themselves without the help of any mechanical tools and machinery equipment. A hiking trip down these locales would serve a big lesson for your life and motivate you to rise up against adversities.

Witness the Taal Lake of Tagaytay

This is an active volcanic site located near a freshwater lake which together adds to form an invaluably exquisite view you would never be able to get it out of your memories for the rest of your life. Such is the insane charm and attractiveness of this place that it keeps you will forget to blink in between on a number of occasions while touring this place. The lake filled with freshwater covers more than 240 sq km and covers a portion of the volcanic sight on one of its end known as Mount Taal. The height of the volcanic mountain site is around 300 metres though it is deemed very risky to visit the top of the mountain as it is considered an active volcanic site which spilt out the hot liquid in the year 1970 last time. All being said, this is indeed one of the most incredible natural wonders of the earth and the Philippines happens to be the lucky place to possess many such marvels of nature.

Get Mesmerized by Chocolate Hills

The Chocolate Hills is one of the most popular places in the Philippines and as a travel lover, you will be committing nothing short of a crime if you skip the tour to Chocolate Hill for any reason at all. These hills are found in the central island territory of Bohol. While many tourists would find themselves lazy to move further once they take a short rest on the tremendous beaches of Bohol, it is no lesser delightful to witness the astounding chocolate hills, a true marvel of nature. The exotic sightseeing locale is particularly known for its unusual geographic formations that never fail to awe-inspire you no matter how many times you look at them. Get the best hotel deals in the Philippines using the Hotels.com Promo Code, Hotels.com Coupons, Hotels.com Discount Code for saving hefty amounts on your travel accommodations.

Source link

0 notes

Text

Aaron Lowell Denton: The Accidental Designer

The following post is brought to you by Squarespace, an easy-to-use website builder for your personal and professional needs. You can start a free trial for a website (with no credit card required) today and use coupon code DESIGNMILK for 10% off your website when you’re ready to publish. Our partners are hand picked by the Design Milk team because they represent the best in design.

Entering the world of Indiana-based visual artist Aaron Lowell Denton can feel like stepping through the doorway of an astonishingly preserved record shop you’d long had forgotten – a realm embellished in the hallmarks reminiscent of Stanislaw Fernandes’ finest OMNI magazine covers, the Memphis Movement, forgotten classics of the 1980s Japanese city pop albums era, and maybe even the neon hued geometric landscapes once emblazoned across blank VHS cassette tapes. With a portfolio pulsing with a surreal experimental glow, Denton has carved out a career as a musician’s artist, one adept at mining the collective memory of music’s imprint onto our emotions, expressed through an Indian summer spectrum of colors and absurdist’s sense of movement.

Photo: Anna Powell Denton

Originally from Upland, a tiny little town in northern Indiana, and now based in Bloomington, Indiana, Denton’s journey follows the trajectory more that of a squiggle than a line. “[When I first moved to Bloomington] I had a slew of day jobs before I went full time with design. I served tables at a vegetarian restaurant here in town called The Owlery,” says Denton, “I also painted houses for a while, alongside some carpentry work. I worked the door at a bar during a 10pm to 4am shift. That was a weird time.”

Between this hodge-podge of jobs, Denton was also designing flyers and posters for a local musical venue for the love of it, sometimes for just $50 a pop, but mostly for free. Over time he found himself spending an extraordinary time on these projects despite the modest pay. It was only when his then-partner-now-wife suggested making a go of a career as a visual artist that Denton decided to abandon toiling 70-hour weeks to dedicate himself fully into his design work.

“I was super scared to quit my restaurant job. I figured I’d try it for a few months and go back to waiting tables, but it worked out! I feel super grateful to have the job and life I have. It’s a privilege, especially in times like these, to be able to work for yourself and make art for a living. I can’t believe I get to do it everyday.”

The world would soon come knocking on Denton’s door by way of Instagram, where his work garnered a great deal of attention from design and music aficionados alike. He’d soon find himself inundated with commissions by promoters all seeking Denton’s uniquely hypnotic pop manifestations for the likes of musicians such as Wild Nothing, Leon Bridges and Khruangbin, John Maus, and Stereolab, tying a lyrical sense of typography together with a heart-on-his-sleeve affection for artists such as Donald Judd, Joan Miró, Helen Frankenthaler, and Bridget Riley.“That high art stuff is a bit in my aesthetic DNA at this point, and my sense of color and composition comes from all the time I spent (and still spend) in museums and looking in books.”

Today Denton’s eye finds itself drawn toward other outliers of art, including surreal futurist Stanislaw Fernandes, 1960s-1970s Japanese typography, and OMNI magazine, influences clearly discernible across his portfolio, “I also got into a big city pop phase last year that resulted in a bunch of work in that style. I just get really into looking and researching a certain style, and I think it’s fun to sometimes try on styles and techniques. It’s a way to give yourself permission to experiment and grow.”

This growth also included designing his own website on Squarespace, where his online portfolio resides alongside an e-commerce shop where some of his more recent work is available as posters. The site has become an integral extension of his online presence, allowing him to connect with new clients and customers alike. Denton remembers designing his site as surprisingly “easy”, crediting Squarespace’s robust site building tools. “There was definitely a time when building a website felt like such a feat, but it’s just not that way anymore.”

Denton also cites an appreciation for the collaborative nature of his work. As a musician himself, he calls the process a “conversation” integral to informing his eventual solution in tying together his vision with the artist, the venue, and even the audience. It’s a process he’s embraced increasingly more as he ventures solely from poster work toward collaborative commissions.

“Part of the art in it for me is the dialogue with clients, and the personal connection that can come out of creating art together,” notes Denton, “Especially when you’re representing someone else’s art with your own, that process has to be collaborative. That being said, like I mentioned, musicians can understand the need to not be caged in too much. They can empathize with needing a certain amount of autonomy to find something unique.”

“I’ve been lucky to work with some of my favorite musicians and it does sometimes feel like it’s coming from somewhere mysterious, pre-cooked.” Promotional risograph poster for Wild Nothing. September, 2018.

When asked about what makes for a good poster or album design, Denton is quick to point out the open-minded nature of his clientele – musicians – has afforded him a fairly relaxed relationship that tends to foster, rather than hamper good design.

“[Musicians] tend to be less intense than say, an art director. When I do a poster there’s not much between my idea and execution and the final piece; whereas, with something like a logo for a business, or a commercial project, it needs to be discussed and examined. That can be fun too…it’s all just different.”

These fairly unrestricted bounds have permitted Denton a level of interpretive freedom not all designers are always given, allowing the artist to consider both the complete oeuvre of the musician with his own personal connections with their music to form novel solutions. “I sometimes feel like the bands I get asked to work for already have visual representations, fully formed, sitting somewhere inside me. Like, they’re formed from my own relationship with the music and fandom.

“Design has a rich history of endearing social messages with imagery. With the Abolish ICE poster I was working with a group called New Sanctuary Coalition to raise funds for immigration bonds, which are exorbitantly higher for people in that system. I’d love to collaborate on more social posters in the future though, it’s an area of my work I really value.”

Photo: Anna Powell Denton

Amusingly, Denton’s affinity for collaboration even extends to the nuts and bolts of operating as a one-person operation. “I actually enjoy emailing quite a bit,” admits Denton, “The dialogue between me and my clients is something I’m actively interested in. I don’t dread any of that stuff.”

Denton credits his Squarespace designed site as an alternative medium to show work outside of social media, one where his work can be shown without the expectations and associations of an audience-based medium like Instagram. “I like to think of my site just as a full view of a collection of work. It’s the fastest way for someone to see what my work is all about.” Visitors are welcome to peruse his portfolio of work and purchase posters from an e-commerce shop vertical. Denton’s design is clean, simple, and easy to navigate, permitting his artwork to be the centerpiece of the experience.

Squarespace has made selling my work all around the world a more accessible possibility. The commerce tools are really easy to use and understand.

With a majority of his past work connected to the music industry, Denton is using his site to aid in pursuing new opportunities, both out of curiosity and out of necessity, “When COVID hit, a majority of my poster work evaporated, so this year has been a lot different as far as where the work is coming from. I’ve been doing more editorial jobs, which I’m really into. I’d like to do a book design at some point, and also want to do more movie posters. I’m trying to learn about motion design in my spare time, so I could see myself trying that at some point.”

Ready to share your vision or brand with the world? Take the first step today with your very own website with Squarespace. Start your free two week trial (no credit card required!) and use coupon code DESIGNMILK when you’re ready to get 10% off.

via http://design-milk.com/

from WordPress https://connorrenwickblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/17/aaron-lowell-denton-the-accidental-designer/

0 notes

Text

A Look Back at the 10th Annual TCM Classic Film Festival

HOLLYWOOD — Double anniversaries: This year’s TCM Film Festival marked two milestones, the 25th anniversary of the classic movie channel, which bowed on April 14, 1994, and the 10th anniversary of its namesake annual event.

In a movie landscape challenged by new platforms, industry consolidation and general entertainment overload, TCM remains a beacon for film buffs. “We’ve stayed true to our mission of showing films the way they’re meant to be seen, uncut and commercial free,” said Jennifer Dorian, TCM general manager. “That mission has not changed over 25 years. And when we started doing this festival, it made sense that it would be the context in which we started to bring people together and then showcase these films once again on these incredible screens in Hollywood.”

Held April 11-14 at the historic TCL Chinese Theatre complex, Egyptian Theatre, Cinerama Dome and the Roosevelt Hotel, the classic movie marathon featured more than a hundred films and events, with most programmed to reflect the festival’s main theme “Follow Your Heart: Love at the Movies.” That certainly was the case for the opening-night attraction “When Harry Met Sally …” (1989), with stars Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan and director Rob Reiner appearing at the TCL Chinese IMAX to celebrate the rom-com’s 30th anniversary. Though “Harry” might seem relatively new by TCM standards, “We had no idea back then if it would stand the test of time,” Crystal told the crowd. Reiner added, “You never know. You make a movie, and hopefully it turns out well, and hopefully others like it, too.”

Also in the opening-night audience was Ted Turner, the broadcast industry magnate whose purchase of the MGM film library in 1986 gave rise to TCM. Along with Turner, others receiving special tributes during the festival were casting director Juliet Taylor, producer Fred Roos, filmmaker Nora Ephron and film historian Kevin Brownlow. Fox Studios, founded in 1905, reincarnated as 20th Century Fox in 1935 and swallowed whole by Disney in 2019, also was feted, with screenings of landmark titles such as “Sunrise: A Story of Two Humans” (1927), “The Sound of Music” and perhaps the studio’s biggest all-time blockbuster and game-changer, “Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope: Special Edition” (1977).

Adding star power were appearances by actors and filmmakers Diane Baker, Jacqueline Bisset, Ronee Blakley, John Carpenter, Keith Carradine, Frank Darabont, Dana Delany, Angie Dickinson, Louis Gossett Jr., Bill Hader, Barbara Rush, Kurt Russell and Alex Trebek. Also scheduled to appear but unable to attend were Norman Lear, Shirley MacLaine, Gena Rowlands and Lily Tomlin.

Among the restored titles receiving world premieres were “Do the Right Thing” (1989), “Escape from Alcatraz” (1979), “Holiday” (1938), “The Killers” (1964), “Kind Hearts and Coronets” (1949), “Merrily We Go to Hell” (1932), “Nashville” (1975) and “Winchester ’73” (1950, U.S. premiere showing).

Though the festival’s tent-pole titles attracted overflow crowds, some of the greatest moments came courtesy of lesser-known films, such as the many pre-Code offerings, rediscoveries and special formats (including nitrate and Cinerama). Here are 10 for the 10th:

"Night World"

Eighty the hard way: Introducing the pre-Code drama “Night World” (1932), Susan Karloff noted that her father Boris “made a lot of films like this”—movies that weren’t prestige projects but were entertaining and well-made nonetheless. A year earlier, Karloff teamed with Mae Clarke for “Frankenstein,” his breakthrough movie, and they reunited for “Night World,” which also features Lew Ayres, George Raft and Hedda Hopper, before she reinvented herself as a professional gossip-monger. “’Frankenstein’ was his 81st film,” Susan Karloff said. ”Nobody saw the first 80.”

Ted Turner on the success of TCM: It comes down to one simple truth: “People like old stuff.” That’s how the founder of Turner Broadcasting, which begat Turner Classic Movies, explained the enduring popularity of the acclaimed cable channel. Now that he’s reached his golden years, the onetime Mouth of the South admitted that he has realized “I’m old, so people finally like me.”

The low-budget bang of the Bs: A turn-away crowd flocked to “Open Secret” (1948), a film noir tinged with social activism, and screened as one of the festival’s many “Discoveries.” Eddie Muller, “The Czar of Noir” and host of TCM’s “Noir Alley,” observed: “This is probably the biggest single crowd ever to see this movie, which is as B as B gets. If they spent more than $2,000 on this film, I’d be amazed.” Despite the movie’s modest origins, “Open Secret” bravely takes aim at nativism and prejudice in post-war America. “I’m very happy to present this movie,” Muller said. “It’s as down and dirty as it gets.”

"Santo vs. the Evil Brain"

Lucha libre, viva Mexico! The midnight screening of the cult/camp classic “Santo vs. the Evil Brain” quickly turned into spectacle as two fans in lucha libre garb swarmed the theater, tossing out treats and trinkets, including El Santo masks on sticks. A Mexican folk hero, El Santo was a luchador enmascarado (masked wrestler) and fighter for justice. As portrayed by actor Rodolfo Guzman Huerta, El Santo appeared in more than 50 films, including the first in the series, “Santo Contra el Cerebro del Mal” (1961, “Santo vs. the Evil Brain”). “It’s a miracle that we’re showing this film,” said archivist Viviana Garcia Besne, whose grandfather introduced El Santo to the screen. “The Mexican film industry is not supporting these movies, despite their popularity.” Her father found the original camera negative of “Santo vs. the Evil Brain,” “so with the centennial of El Santo [Guzman Huerta] in 2017, we thought we should restore his movies.” She implored the audience to revel in the film’s over-the-top spirit: “You must react or you’ll fall asleep.”

Remembering the King of the Cowboys: Through the ’20s, Tom Mix rode tall in the saddle and revolutionized the Western by focusing on action and performing his own stunts. A century later, however, he’s all but forgotten. Introducing a double feature of “The Great K&A Train Robbery” (1926) and “Outlaws of Red River” (1927) at the Legion Theatre, TCM senior programming director Scott McGee paid tribute to “the ultimate cowboy star” and mentioned that several of his younger TCM colleagues had never heard of Mix, once nicknamed “The Rent Man” by theater exhibitors. Most of Mix’s nearly 300 films (all but nine were silent) were lost in a 1937 studio fire, so those TCM youngsters could be forgiven for their ignorance.

Shot on location in Colorado, “The Great K&A Train Robbery” proved that “the real natural wonder was Mix himself,” McGee said. “He was a bona-fide cowboy and horseman of the highest order.” Mix’s penchant for fancy duds emphasized that he was “all about the show and the flash. He knew that clothes do make the man.” MoMa curator Anne Morra added that even though “his clothes weren’t trail-worthy, he always gets the girl,” and pointed out that Mix’s trusty steed, Tony the Wonder Horse, outlived his master, who died in a car accident in 1940, by two years.

"It Happened Here"

Speaking truth to power: Accepting the second annual Robert Osborne Award, which honors individuals crucial in maintaining the legacy and preservation of classic films, historian, author and filmmaker Kevin Brownlow warned the crowd that he was going to go off-script. “Where’s release of ‘Hollywood’?” he said, referring to his influential documentary series about the silent-film era, shown on TV in 1980 but never released in a home-video format due to rights issues.

As part of the Brownlow tribute, TCM screened his own “It Happened Here,” which imagines what might have occurred if Germany had conquered Britain during World War II. At 15, Brownlow began making the docudrama with creative partner Andrew Mollo, and over eight years, the two attracted eventual assistance from directorial lions Tony Richardson and Stanley Kubrick. As “It Happened Here” began to roll at the Egyptian, and introductory credits about the movie’s restoration identified it as a 1965 release, Brownlow from his seat shouted out “1964!”

The patriarchy strikes back: Though she was the first female to receive the Directors Guild Fellowship Award and successfully helmed seven films from 1966 to 1974, writer/director/producer Stephanie Rothman found herself on the outs by the mid-’70s. Speaking before a midnight screening of her “Student Nurses” (1970), Rothman recalled that studio chiefs thought she was “too intellectual”—even though she specialized (by necessity) in exploitation fare. In the early ’80s, one exec finally brought her in for a meeting to discuss a project for a young male director about to make his first studio film. “It sounded just like my own ‘Velvet Vampire’ [1971],” Rothman said. “So I asked them, why not hire me? They didn’t.” The filmmaker and film in question turned out to be Tony Scott and the vampire-themed “The Hunger” (1983).

"The Killers"

Taking dead aim at the truth: Always the straight shooter, actress Angie Dickinson told it like it was in her introductory remarks before “The Killers” (1964), Don Siegel’s crime thriller, loosely based on the Ernest Hemingway short story. Shot in unusually vivid Eastman Color, it follows two hit men (Lee Marvin and Clu Gulager) trying figure out the score of their score. Neither of the male leads—John Cassavetes as the mark and Ronald Reagan as the mastermind—wanted to be in this movie, she recalled. In his last film before he launched his political career, Reagan made “The Killers” “just to get out of his contract.” And Cassavetes—“that is some Greek”—“was pretty quiet,” she said. “The film wasn’t his style but he needed the work,” she added, referring to the actor-director’s preference for his own indie, iconoclastic projects. Dickinson attributes the film’s success to Siegel (“an absolute doll—adorable!”) and Cassavetes (“he was so charismatic, he didn’t have to do anything on the screen”), and not so much to Reagan: “You could tell that he was kinda dying back there.”

As for why she didn’t become a bigger star, Dickinson said, “It didn’t happen. It takes a lot of luck, and I didn’t have the drive. The parts weren’t there. So I did ‘Police Woman’”—her hit ’70s series—“which was a grind and did me in.” At that point, TCM host Ben Mankiewicz reminded her that 100 episodes of “Police Woman” was nothing to sneeze at, and Dickinson quickly corrected him: “Actually, 91.” She laughed and added, “I am such a truth buff.”

The circle of life, Tinsel Town edition: Introducing the silent film “A Woman of Affairs” (1928), starring Greta Garbo and John Gilbert, which was screened with a full orchestra led by Carl Davis conducting his own score, at the historic Egyptian, film scholar Leonard Maltin acknowledged a stroke of serendipity: “We have one of those only in Hollywood moments tonight. Performing on the French horn in the orchestra is the great-great grandson of John Gilbert.”

The enduring legacy of Robert Osborne: Throughout the festival, many luminaries saluted the late figurehead of TCM. “Robert loved this festival,” said Kevin Brownlow. “He lobbied for it for years and basked in its success and its shared community.” Speaking ahead of “Magnificent Obsession” (1954), in which she co-starred opposite Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman, Barbara Rush recalled, “We grew up together in the business. It was Robert who really got TCM going,” she said, reflecting on Osborne’s own magnificent obsession. “He was like a very dear brother to me. Plus, he knew everything, especially about the movies.”

from All Content http://bit.ly/2PkpYgT

0 notes

Text

CAPE TOWN ART FAIR QUESTIONNAIRE

The Goodman gallery had the same gallerists as the gallery, and the layout of the booth was similar to the gallery’s layout. The walls were not too cluttered, each work was spaced out evenly. There were about 2 Goodman gallery booths. None of them had works from the current artists being shown at their gallery in Cape Town. The Stevenson Gallery booth felt interactive, much like the gallery itself. There were different gallerists and different works up. The vibe was very similar to the main gallery in Woodstock. The Blank Gallery booth was run by the same gallerists, and displayed some work of the same artist who was being shown in the gallery. There was some other work up by other artists as well. A few pieces in the booth were installation and hanging pieces, much like the gallery in Woodstock. The booth was a bit more filled than the gallery itself.

2. I absolutely loved Sheltering by Matt Philips. This painting was geometric and colourful and abstract. It is a very textured painting made up of many sharp shapes such as triangles. The artist used silica and pigment to paint this on linen fabric, which adds to the texture. I love this piece because I love abstract art. His use of colourful shapes in the order they are makes the painting seem like a ladder of some sorts. Ascending. Another piece I loved was An unexpected absence by Kirsten Beets. This piece made up of many other pieces is part of a series of paintings this artist did. Very simple, minimal painting of three chairs in a seemingly confined landscape. The lack of people in this painting makes it enticing to look at. It brings sadness to the surface, but yet so aesthetically pleasing. One of the three chairs is tipped over, making it seem left out. The role of these chairs are almost personified. Another piece I loved was by Kenneth Baker, called Abstract. This old piece resembles an almost tribal symbolic message. The dark lines and colours create a sense of a journey that has been undertaken by the artist. Either inward or an outward journey. I love this piece because of how raw and rough it is. One can see the layers of paint, and the thick lines he wished to present. This piece brings up many questions, and makes one wonder what the artist had to experience in order to make such a piece.

Three pieces I disliked were to do with large figurative, slightly realistic pieces. I really do not like realistic figures painted in a “commercial” way. Time keeper 113 by Norman O’Flynn does not interest me because of how saturated it is. The Large painting of a figure in bright vibrant colours draws me away. The slight street art aesthetic is played with in this piece by using some spray paint and thick paint. This piece comes from a series called The timekeepers. I struggle to find meaning and authenticity is this styled work. Another piece I disliked was Ornama 119 by Kilmany-Jo Liversage. Another large scale painting. This portrait was created by acrylic, spray paint and markers on canvas. This vibrant and saturated colour portrait resembles a pop art type artwork. Using conventional materials. The street art style is also seen in this piece by using spray paint, and tagging a section of the painting. The artist’s use of thick colourful lines does not resonate with me as I find it too distracting; I’m not sure where to look at. Finally, Nouvo Mondo by A. Collesano - an ink drawing of a giant eel hovering over a lighthouse. I am not a fan of tattoo styled drawings, nor fantasy creatures. This artwork does not sit well with me because it doesn’t say much to me. I feel Andrea’s olden day technique of ink drawings are too outdated to be creating them today.

3. The predominant mediums used in this year’s art fair were painting, mixed media. Predominant processes were repetition and collaging using other materials such as fabric, string etc.

4. The major differences between booths were obvious when looking at the size of some booths. Some were much larger than others, displaying more and larger works. Some booths went inside a smaller room; this was not often, but a few booths did so. A few booths were interactive, thus allowing the viewers to really take part in the work they were displaying. Some booths just had works displayed on the four sides of their walls, where as others had pieces in the middle of the booth.

5. In terms of signage, some booths have more than others. Solo booths have more signage around the pieces; more descriptions. Sometimes there were description of the exhibition on the wall next to the artist’s name. Other booth only had a small sign stating what gallery they were, and small labels on each work. Some booths didn’t have label on their, thus one would have to ask who the artist was and what was the work called. Most of the time, titles of the works were very small next to the piece.