#ushahidi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Can crowdsourced information during times of crisis (e.g. pandemic, natural disasters) mobilise the public into action (e.g. get to safety, assist those in need, communicate important information, etc.)?

In times of crisis, the role of crowdsourced information has become increasingly vital. Whether it's a pandemic, natural disaster, or any other emergency, the ability of individuals to share real-time information can mobilize communities into action, facilitating effective responses and support systems. This blog post explores how crowdsourced information during crises can drive public action and enhance community resilience, drawing on historical examples and the affordances of social media platforms. The Power of Crowdsourcing in Crisis Situations Crowdsourcing refers to the practice of obtaining information or services by soliciting contributions from a large group of people, often via the internet. In crisis scenarios, this collective intelligence can provide timely and relevant information that is crucial for effective emergency response. The advent of social media platforms has transformed how information is shared and consumed during emergencies, allowing for rapid dissemination and real-time updates.

Historical Context: The Haiti Earthquake One of the most significant examples of successful crowdsourcing in a crisis is the response to the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Following the disaster, initiatives like Ushahidi emerged, enabling individuals on the ground to report their needs via SMS (Starbird 2011). This platform allowed for the aggregation of critical information regarding medical emergencies, shelter requirements, and food shortages (Starbird 2011). Virtual “crowd” of volunteers worldwide processed and verified these raw messages, plotted it on their crowdmap, accessible to the public (Starbird 2011). The speed and accuracy of this crowdsourced data were instrumental in coordinating responses from humanitarian organizations like the American Red Cross and FEMA 12 (Starbird 2011). The Mission 4636 initiative further exemplifies this phenomenon. It allowed Haitians to send free text messages detailing their needs, which were then categorized and geo-located by volunteers globally. This project processed over 80,000 messages within a short period, showcasing how local knowledge combined with global volunteerism can enhance crisis response (Munro 2012).

0 notes

Text

Can crowdsourced information during times of crisis (e.g. pandemic, natural disasters) mobilise the public into action (e.g. get to safety, assist those in need, communicate important information, etc.)?

Crowdsourcing refers to a variety of activities involving the collection of input or resources from a large number of individuals, but it is difficult to define because it can take many different forms. Various scholars have attempted to define it, but there is no single accepted definition. Some regard it as a problem-solving tool, while others see it as a means of promoting company innovation. As a result, some people may consider Wikipedia or YouTube to be examples of crowdsourcing while others may not. The phrase "crowdsourcing" is derived from two words: "crowd," representing the people involved, and "sourcing," which refers to the act of obtaining resources. While this provides a fundamental overview, it does not cover all aspects of crowdsourcing. To better understand what constitutes crowdsourcing, this blog examines various definitions and provides crucial criteria that can be utilized to identify crowdsourcing activities more precisely (Estelles-Arolas & Gonzalez-Ladron-de-Guevara 2012).

Image of Crowdsourcing

Since Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential election, platforms such as Facebook, X (Twitter) and YouTube have transformed political campaigns, allowing for more efficient information sharing, personal connections and targeted messages. However, the digital revolution brings new issues such as privacy violations, false accounts, foreign interventions, and the spread of misinformation, all of which interfere with voter trust and election integrity. Incidents like the Cambridge Analytica incident pushed nations to adapt rules to reduce these risks. Elections officials in East and Southeast Asia, where social media is widely used, have launched initiatives to address these challenges. However, the region has seen instances of online misinformation leading to violence, emphasizing the need of powerful measures to manage digital threats before elections (Tan 2020).

Gif by Angelyn T.

Regulating social media during elections is difficult, especially given the growing incidence of misinformation coming from sources beyond a country's authority (Tan 2020). This issue is especially important during elections, when bogus news can confuse voters and put at risk fairness. While social media allows people to access and exchange election-related information, it may also be used by political players to manipulate public opinion through fake accounts, automated bots, and targeted adverts (Tan 2020). Similarly, during crises such as disasters or pandemics, rapid response and effective communication are critical. Crowdsourcing can play an important role in such situations, assisting people to stay informed, report misinformation, and take appropriate action. During elections, crowdsourced systems such as Kenya's Ushahidi efficiently monitored and reduced election-related violence. However, controlling internet content remains challenging due to disparities in national norms and the complexities of foreign influence (Tan 2020). Despite these challenges, crowdsourcing is a viable strategy of combatting misinformation and ensuring vote integrity, as well as raising public knowledge and engagement.

Other than that, an Electoral Management Body (EMB) oversees elections and its efficiency is determined by factors such as the legal framework, political climate and EMB independence. To address digital electoral difficulties, EMBs must have a strong political framework, access to cybersecurity resources and the ability to enforce standards governing online political expression, campaign funding and disinformation. This shows an index to assess EMBs’ preparedness to deal with digital disruptions, based on criteria: the EMB model (Independent Government or Mixed), the presence of regulations governing online campaign, data protection and misinformation, the rule of law and technological readiness. The index assesses how well countries are prepared to deal with digital difficulties during elections using both qualitative and quantitative data, such as the World Bank’s Rule of Law Indicator and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Technological Readiness Ranking. EMBs are graded based on these criteria, with higher ratings indicating a greater ability to control digital threats and maintain electoral integrity.

The Facebook/Cambridge Analytica incident in 2018 demonstrated how personal information may be abused in political campaigns. Data was acquired without the users’ content and used to target voters with individualized political advertisements, potentially affecting their beliefs and threatening integrity. In response, the European Union reinforced its data protection rules, most notably with the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), to promote openness and defend the democratic process. The argument also prompted questions about misinformation, micro-targeting and the ability of data analytics to influence public opinion. As technology advances, it is critical to establish ethical rules and openness in how personal data is used in order to preserve privacy and promote fair and democratic elections (Monteleone 2019).

In conclusion, crowdsourcing is an effective method for mobilizing the people during crises, allowing for real-time communication, resource allocation, and grassroots action. While it raises issues such as misinformation and verification, they can be addressed through focused tactics such as increased digital literacy, technological innovation, and collaborative frameworks. By taking advantage of crowdsourcing's capabilities while reducing its risks, societies might strengthen their resilience and responsiveness during times of crisis, eventually saving lives and building better communities.

Gif by buildingback

(788 words)

Reference list

Estelles-Arolas, E & Gonzalez-Ladron-de-Guevara, F 2012, ‘Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition’, Journal of Information Science, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 189–200, viewed 26 November 2024, <http://www.crowdsourcing-blog.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Towards-an-integrated-crowdsourcing-definition-Estell%C3%A9s-Gonz%C3%A1lez.pdf>.

Monteleone, S 2019, AT A GLANCE, viewed 26 November 2024, <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2019/637952/EPRS_ATA(2019)637952_EN.pdf>.

Tan, N 2020, ‘Electoral Management of Digital Campaigns and Disinformation in East and Southeast Asia’, Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, viewed 26 November 2024, <https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/epub/10.1089/elj.2019.0599>.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Crowdsourcing Changed the Game for All of Us

Ever paused to think about how much we rely on each other online? From solving global crises to deciding what LEGO set to buy next, crowdsourcing isn’t just a fancy word—it’s a whole vibe. It's proof that when humans come together (even virtually), incredible things can happen. Let’s dive into how crowdsourcing is shaking things up everywhere—from disasters to hobbies.

So, What’s the Deal With Crowdsourcing?

Imagine asking a group of strangers on the internet to help you finish a project. Weird, right? But that’s basically what crowdsourcing is. Instead of depending on one person or a tiny team, you reach out to a “crowd” to pitch in ideas, funds, or even manual work.

It’s not new (the Oxford English Dictionary has been crowdsourcing since the 1800s!), but the internet has made it huge. These days, it’s in everything—from tracking hurricanes to deciding which potato salad gets funded on Kickstarter (yes, that actually happened).

Saving the Day With Crowdsourcing

When disasters hit, crowdsourcing shines. Remember the 2011 Japan tsunami? Regular people with smartphones became on-the-ground reporters, sharing real-time updates about what was happening where. Platforms like OpenStreetMap let volunteers map out affected areas, showing people which roads were blocked and where to find safety.

Then there’s Ushahidi, a super cool tool that maps crisis data. It was used in Kenya to track election violence and has since been a lifesaver—literally—during disasters. People can report what they’re seeing, and voilà, you’ve got a clear picture of what’s happening.

And it’s not just about information. Crowdfunding platforms like GoFundMe are lifesavers too. After the earthquake in Palu, Indonesia, donations poured in to help victims rebuild their lives. It’s amazing how strangers band together when it really matters.

LEGO Bricks and Big Ideas

Okay, let’s talk about something less serious for a second: LEGO. Did you know the company has a crowdsourcing platform called LEGO Ideas? Fans submit their designs, and if enough people vote for them, LEGO might turn them into actual sets. And yes, the creators get paid (royalties, baby!).

This isn’t just good business for LEGO—it’s a great way to keep fans engaged and creative. Plus, how cool is it to walk into a store and see something you made on the shelves?

Social Media: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

Social media has taken crowdsourcing to the next level. Take the 2021 White Flag Movement in Malaysia. People who were struggling during COVID-19 lockdowns put up white flags outside their homes to signal they needed help. Social media spread the word, and soon, neighbors and strangers were pitching in with food and supplies.

But there’s a flip side. Crowdsourced info isn’t always accurate. We’ve all seen how quickly fake news can spread. Platforms like Twitter and Facebook have had to step up their game to fact-check posts, but the question remains: how much can we trust crowdsourced data?

Crowdsourcing: A Blessing or a Curse?

Crowdsourcing has its challenges. Some platforms rely on unpaid contributions, which can feel exploitative. And while we love the internet for bringing people together, it’s not always fair. Sometimes, a few voices dominate, drowning out the rest.

But despite its flaws, crowdsourcing is a game-changer. It’s democratized creativity, disaster response, and even fundraising. It’s proof that when people come together—whether for fun or survival—there’s nothing we can’t do.

Final Thoughts

Crowdsourcing is here to stay, and honestly, we’re better for it. Whether it’s funding indie films on Kickstarter or mapping flood zones to save lives, the crowd has power. So, the next time you chip in on a group project (IRL or online), remember: you’re part of something much bigger.

References

Brabham, D. C. (2013). Crowdsourcing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Howe, J. (2006). The Rise of Crowdsourcing. Wired.

OpenStreetMap. Retrieved from https://www.openstreetmap.org.

LEGO Ideas. Retrieved from https://ideas.lego.com.

Crowdsourcing Week. Using Crowdsourcing to Combat Coronavirus.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Crowdsourcing: How Strangers Online Are Saving Lives

Imagine a devastating earthquake strikes, leaving entire communities cut off and in desperate need of help. Communication systems are down, and chaos takes over. Then, through platforms like Twitter or SMS-based tools, strangers from across the world begin sending updates, mapping damage, and coordinating rescue efforts. This is crowdsourcing in action. It is the power of collective digital collaboration, transforming crises into opportunities for global teamwork.

While the potential of crowdsourcing is extraordinary, it also comes with challenges. Let’s explore the successes, struggles, and lessons that make this phenomenon both inspiring and complex.

How Crowdsourcing Transforms Crises

One of the most notable examples of crowdsourcing was during the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Traditional communication systems were wiped out, making it nearly impossible to understand the full scope of the disaster. Ushahidi, a crowdsourcing platform, stepped in to bridge the gap. People on the ground used SMS and social media to report destroyed buildings, trapped individuals, and urgent needs. These reports were turned into a real-time crisis map that guided rescue teams to areas requiring immediate attention (Ford, 2012).

The 2011 Japan tsunami demonstrated a similar use of digital collaboration. Platforms like Twitter became vital for spreading real-time updates. Survivors used these platforms to share evacuation routes, warn others about aftershocks, and connect with rescue teams. Digital communities harnessed their collective knowledge to tackle immediate problems and offer support where it was most needed (Bruns et al., 2012).

These examples showcase how crowdsourcing transforms emergencies into opportunities for action, proving that even in the face of disaster, humanity can come together in extraordinary ways.

From Crowdsourcing to Crowdfunding

Crowdsourcing is not limited to information sharing. It also extends to pooling financial resources through crowdfunding platforms like GoFundMe and Indiegogo. During the Queensland floods in 2011, social media not only helped with real-time updates but also inspired massive fundraising efforts. These funds provided crucial financial support to affected communities, helping them rebuild their lives (Bruns et al., 2012).

Bennett et al. (2015) explain that crowdfunding works because it feels personal. Seeing someone’s story or watching a campaign grow in real time creates a sense of connection. With just a small donation, people feel like they are part of something meaningful, and those small contributions quickly add up to significant impact.

The Challenges of Crowdsourcing

Despite its potential, crowdsourcing has its pitfalls. One of the biggest challenges is misinformation. In the chaos of a disaster, unverified reports can spread quickly, causing confusion and misdirecting resources. Ford (2012) highlights that while the "wisdom of the crowd" can be a force for good, it also amplifies mistakes when bad information goes unchecked.

Another major issue is accessibility. Not everyone has the tools or internet access to participate in crowdsourcing efforts, especially in rural or low-income areas. Posetti and Lo (2012) emphasize that this digital divide excludes the most vulnerable people, making it critical to create systems that are more inclusive and equitable.

Personal Reflection

Crowdsourcing is one of those concepts that restores my faith in humanity. I remember following the Haiti earthquake response and being blown away by how people from across the globe stepped in to help. It showed me that even in the darkest moments, the human instinct to connect and support each other is incredibly powerful.

On the other hand, I have also seen the downsides. During the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation about vaccines spread like wildfire in online spaces. What started as well-meaning discussions often turned into fearmongering or confusion, highlighting the importance of responsibility when using these platforms.

Crowdsourcing works because it taps into our shared humanity, but it also reminds us of the need for critical thinking and accountability.

Why Crowdsourcing Matters

Crowdsourcing highlights the incredible potential of collective action. From mapping disaster zones and providing real-time updates to pooling financial resources, it shows that we are stronger when we work together.

However, its limitations, such as misinformation and unequal access, remind us that even the best tools need thoughtful application. Despite these challenges, the heart of crowdsourcing lies in its ability to connect people and inspire meaningful action. It proves that in times of crisis, hope and help are only a click away.

References

Bennett, L., Chin, B., & Jones, B. (2015). Crowdfunding: A New Media & Society Special Issue. New Media & Society, 12(2). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444814558906

Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Crawford, K., & Shaw, F. (2012). #qldfloods and @QPSMedia: Crisis Communication on Twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland Floods. Social Media + Society, 7-10. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/48241/1/floodsreport.pdf

Ford, H. (2012). Crowd Wisdom. Index on Censorship, 33-39. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422012465800

Posetti, J., & Lo, P. (2012). The Twitterisation of ABC’s Emergency & Disaster Communication. Social Media Research Papers. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/ielapa.046926063833158

0 notes

Text

Hongera Tanzania Kufuzu AFCON, Mko Vizuri Sana..

Safari ya Tanzania kufuzu kwa mashindano ya Kombe la Mataifa ya Afrika (AFCON) kwa mwaka 2025 Nchini Morocco unaweza kusema imejaa historia, juhudi, na shangwe isiyopimika. Kufuzu kwa mara nyingine kwa mashindano haya makubwa barani Afrika ni ushahidi wa jinsi soka la Tanzania limekua na jinsi vijana wetu wameonyesha moyo wa ushindani wa kweli. Ni wakati wa kujivunia mafanikio haya, si kwa…

0 notes

Text

TEDにて

クレイ・シャーキー:思考の余剰が本当のリアルな世界を変える!

(詳しくご覧になりたい場合は上記リンクからどうぞ)

クレイ・シャーキーが「思考の余剰」に注目しています。これは、人々が頭の余力を使って行っているインターネット上で共有された善行為作業のことです。

忙しくWikipediaを編集し、Ushahidiに投稿をするとき (それにLOLcatsを作っているときでさえ)、私達は、より良い善行為という協力的なリアルな世界を全世界に作り出しているのです。

プログラミングで、これをオープンソース化し、ゲーム理論で言うところの「ポジティブサムゲーム」というプラットフォームに変えることにします。

オコーラがしたことは、人に親切心がなければ、不可能で社会的なデザインの課題が、この2つに依存する状況が増加しています。そして、オコーラがしたことは、デジタル技術がなければ不可能でした。

思考の余剰には、あと半分の要素があります。20世紀のマスメディアの状況は人々に消費を促すことに長けていました。

結果として、私たちはよく消費するようになりました。

しかし、今やインターネットやスマートフォンのような道具によって、消費以上のことができるようになりました。

人々がテレビ漬けだったのは、好きこのんでそうしていたのではなかったのです。

私たちに与えられていた機会がそれしかなかったからに過ぎません。

もちろん、私達は今でも消費するのは好きです。

しかし、作ることも共有することも好きなことがはっきりしました。

最後に、カルチャーと伝統は一度でも壊れると元には戻らないということをわかりやすいデータとグラフで表現してもいます。

シュンペーターの創造的破壊は、一定数の創造の基礎を蓄積後に、未来を高密度なアイデアで練り上げてから破壊をするのが本質です。

こうして、憎しみの連鎖や混乱を最小限にする。

太古から高密度なアイデアは、概念の豊富な人間からしか創造されません。

太古から高密度なアイデアは、概念の豊富な人間からしか創造されません。

太古から高密度なアイデアは、概念の豊富な人間からしか創造されません。

特に日本のマスメディア、テレビ局など、顕著な傾向で、構造的な問題もあるかもしれません。

国民にマスメディアを使用して巧妙に情報操作している可能性が色濃くあります。再編して改善かな?

テレビなどは、アーカイブで追跡調査できるから倫理委員会に依頼するのも東京地検が抜き打ち調査しても良いかも知れません。

今ではテレビ局も権力者!日本のテレビ局は再編すべき!

一度、国に返上して、車と同様に放送免許停止や放送免許取消を導入すべきです。

もう一度言います!

テレビ局も今では権力者!再び、過ちを繰り返すかもしれません!

影響力の巨大な政治家、役所、警察、テレビ局や大中企業などの権力者以外なら規模も小さいので

表現の自由も良いでしょう。弱者にこそ自由!

世の中の影響力や権力が大きくなるほど言論の自由は制限されるのがこの世の真理。

今や、テレビやこれに出演している人間は、言論や表現の自由ではなく情報操作の自由。

テレビ局は解体、再編を!日本のテレビ局は再編すべき!一度、国に返上して、車と同様に放送

免許停止や放送免許取消を導入すべきです。

東日本大震災の際に放送無用でも、庶民生活に支障はなかったことですでに証明されています。

そして、裁判所の令状なしに監視カメラに人工知能を使用するのはプライバシー侵害です。

もしかして、日本国憲法の通信の秘匿にも?弱者である庶民への圧力?自動車のナンバーも無許可で読み取っています。

まず、影響力の巨大な政治家、役所、警察、テレビ局や大中企業の内部通報用として搭載して

手本を示してはいかがでしょうか?

スタンフォード実験(1970年代)?ミルグラム実験(1960年代)?マスメディアを悪用した戦前の日本の空気(1940年代)?似ている?同じことを繰り返さないようにみんなで見守っていくことだ。

日本では、適用されていないから令状申請を法律で義務化すればいいかもしれない。

特別に、日本の場合は、テレビに関係する放送内容、広告については、巧妙に情報操作している可能性が色濃く、出演料も高額な出演者、放送関係者も含めて全員、巨大な権力者は疑って観ることが重要です。

なお、日本の全テレビ局は超裕福層に入ります。

自らが権力者であることを発信せず視聴者を混乱させ、それに便乗して権力乱用する日本の民法テレビ局。同じことを繰り返さないようにみんなで見守っていくことだ。

情報技術の発展とインターネットで大企業の何十万、何百万単位から、facebook、Apple、Amazom、Google、Microsoftなどで数億単位で共同作業ができるようになりました。

現在、プラットフォーマー企業と呼ばれる法人は先進国の国家単位レベルに近づき欧米、日本、アジア、インドが協調すれば、中国の人口をも超越するかもしれません。

法人は潰れることを前提にした有限責任! 慈愛��基本的人権を根本とした社会システムの中の保護されなければならない小企業や個人レベルでは、違いますが・・・

ヨーロッパでの一般データ保護規則(GDPR)でも言うように・・・

年収の低い個人(中央値で600万円以下)から集めたデータほど金銭同様に経済的に高い価値を持ち、独占禁止法の適用対象にしていくことで、高価格にし抑止力を持たせるアイデア。

自分自身のデータを渡す個人も各社の取引先に当たりデータに関しては優越的地位の乱用を年収の低い個人(中央値で600万円以下)に行う場合は厳しく適用していく。

こういう新産業でイノベーションが起きるとゲーム理論でいうところのプラスサムになるから既存の産業との

戦争に発展しないため共存関係を構築できるメリットがあります。デフレスパイラルも予防できる?人間の限界を超えてることが前提だけど

しかし、独占禁止法を軽視してるわけではありませんので、既存産業の戦争を避けるため新産業だけの限定で限界を超えてください!

最後に、マクロ経済学の大目標には、「長期的に生活水準を高め、今日のこども達がおじいさん達よりも良い暮らしを送れるようにする!!」という目標があります。

経済成長を「パーセント」という指数関数的な指標で数値化します。経験則的に毎年、経済成長2%くらいで巡航速度にて上昇すれば良いことがわかっています。

たった、経済成長2%のように見えますが、毎年、積み重ねるとムーアの法則みたいに膨大な量になって行きます。

また、経済学は、大前提としてある個人、法人モデルを扱う。それは、身勝手で自己中心的な欲望を満たしていく人間の部類としては最低クズというハードルの高い個人、法人。

たとえば、生産性、利益という欲だけを追求する人間。地球を救うという欲だけを追求する人間。利益と真逆なぐうたらしたい時間を最大化したいという欲を追求する人間。などの最低生活を保護、向上しつつお金の循環を通じて個人同士の相互作用も考えていく(また、憎しみの連鎖も解消する)

多様性はあるが、欲という側面では皆平等。つまり、利益以外からも解決策を見出しお金儲けだけの話だけではないのが経済学(カントの「永遠平和のために」思想も含めて国家や権力者は透明性を究極にして個人のプライバシーも考慮)

(個人的なアイデア)

人間自体を、追跡すると基本的人権からプライバシーの侵害やセキュリティ上の問題から絶対に不可能です!!

これは、基本的人権がないと権力者が悪逆非道の限りを尽く��てしまうことは、先の第二次大戦で白日の元にさらされたのは、記憶に新しいことです。

マンハッタン計画、ヒットラーのテクノロジー、拷問、奴隷や人体実験など、権力者の思うままに任せるとこうなるという真の男女平等弱肉強食の究極が白日の元にさらされ、戦争の負の遺産に。

基本的人権がないがしろにされたことを教訓に、人権に対して厳しく権力者を監視したり、カントの思想などを源流にした国際連合を創設します。他にもあります。

参考として、フランスの哲学者であり啓蒙思想家のモンテスキュー。

法の原理として、三権分立論を提唱。フランス革命(立憲君主制とは異なり王様は処刑されました)の理念やアメリカ独立の思想に大きな影響を与え、現代においても、言葉の定義を決めつつも、再解釈されながら議論されています。

また、ジョン・ロックの「統治二論」を基礎において修正を加え、権力分立、法の規範、奴隷制度の廃止や市民的自由の保持などの提案もしています。現代では権力分立のアイデアは「トリレンマ」「ゲーム理論の均衡状態」に似ています。概念を数値化できるかもしれません。

権限が分離されていても、各権力を実行する人間が、同一人物であれば権力分立は意味をなさない。

そのため、権力の分離の一つの要素として兼職の禁止が挙げられるが、その他、法律上、日本ではどうなのか?権力者を縛るための日本国憲法側には書いてない。

モンテスキューの「法の精神」からのバランス上、法律側なのか不明。

立法と行政の関係においては、アメリカ型の限定的な独裁である大統領制において、相互の抑制均衡を重視し、厳格な分立をとるのに対し、イギリス、日本などの議院内閣制は、相互の協働関係を重んじるため、ゆるい権力分立にとどまる。

アメリカ型の限定的な独裁である大統領制は、立法権と行政権を厳格に独立させるもので、行政権をつかさどる大統領選挙と立法権をつかさどる議員選挙を、別々に選出する政治制度となっている。

通常の「プロトコル」の定義は、独占禁止法の優越的地位の乱用、基本的人権の尊重に深く関わってきます。

通信に特化した通信プロトコルとは違います。言葉に特化した言葉プロトコル。またの名を、言論の自由ともいわれますがこれとも異なります。

基本的人権がないと科学者やエンジニア(ここでは、サイエンスプロトコルと定義します)はどうなるかは、歴史が証明している!独占独裁君主に口封じに形を変えつつ処刑される!確実に!これでも人権に無関係といえますか?だから、マスメディアも含めた権力者を厳しくファクトチェックし説明責任、透明性を高めて監視しないといけない。

今回、未���のウイルス。新型コロナウイルス2020では、様々な概念が重なり合うため、均衡点を決断できるのは、人間の倫理観が最も重要!人間の概念を数値化できないストーカ��人工知能では、不可能!と判明した。

複数概念をざっくりと瞬時に数値化できるのは、人間の倫理観だ。

そして、サンデルやマルクスガブリエルも言うように、哲学の善悪を判別し、格差原理、功利主義も考慮した善性側に相対的にでかい影響力を持たせるため、弱者側の視点で、XAI(説明可能なAI)、インターネット、マスメディアができるだけ透明な議論をしてコンピューターのアルゴリズムをファクトチェックする必要があります。

<おすすめサイト>

実用に向けた大規模言語モデルApple インテリジェンス 2024

トーマス・ドームケ:AIがあれば、誰でもコーダーになれる

キャロル・ドウェック:必ずできる!― 未来を信じる 「脳のパワー」

スティーブン・ジョンソン:良いアイデアはどこで生まれる?

ジャロン・ラニアー:インターネットをどう善の方向に作り変えるべきか!

ハワード・ラインゴールド: 個々のイノベーションをコラボレーションさせる

ピート・アルコーン:2200年の世界について

イギリス保守党。党首デービッド・キャメロン: 政府の新時代

Japan TV of Secret(日本のテレビの秘密)Kindle版

個人賃金→年収保障、ベーシックインカムは、労働市場に対する破壊的イノベーションということ?2022(人間の限界を遥かに超えることが前提条件)

世界の通貨供給量は、幸福の最低ライン人間ひとりで年収6万ドルに到達しているのか?2017

<提供>

東京都北区神谷の高橋クリーニングプレゼント

独自サービス展開中!服の高橋クリーニング店は職人による手仕上げ。お手頃50ですよ。往復送料、曲Song購入可。詳細は、今すぐ電話。東京都内限定。北部、東部、渋谷区周囲。地元周辺区もOKです

東京都北区神谷の高橋クリーニング店Facebook版

#クレイ#シャーキー#思考#リアル#インター#ネット#GPT#善玉#共有#Wiki#pedia#協力#伝統#データ#ワーク#シス��ム#カルチャー#テレビ#マスメディア#tokyo#秘匿#通信#憲法#NHK#zero#ニュース#発見#discover#discovery

0 notes

Text

Week 12 : Crowd sourcing in times of crisis

The term "crowdsourcing" refers to the process of acquiring necessary ideas, materials, or services by asking a large number of people, particularly those in the online community, to contribute rather than hiring conventional workers or suppliers (Merriam Webster 2019).

According to (Riccardi 2016) the use of social media and the Internet to "virtually" harness people's strength and unite them in support of a crisis is another definition of crowdsourcing.

Journalist Jeff Howe introduced the phrase "crowdsourcing" for the first time in 2006 (Ghezzi 2017). The British government, however, offered a £20,000 reward for a device that could accurately measure longitude and, as a result, improve maritime safety and lower the number of sailors who lost their lives in 1714, making that one of the earliest known instances of crowdsourcing. This was done through the Longitude Act of 1714. The first marine chronometer was created as a result of this (Dunn 2014).

With a wide range of tools at their disposal, digital citizens may now swiftly raise global awareness of problems and natural catastrophes while also seeking answers and aid. This is made possible by the affordances provided by the internet and social media networks.

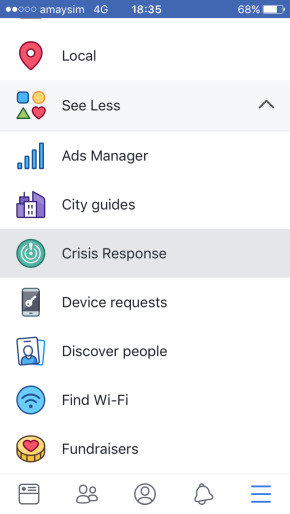

Since the 2011 Japanese earthquake and tsunami, Facebook has started creating disaster response capabilities. Beginning in 2014 with the release of their Safety Check product, they started with a discussion board. They subsequently included fundraisers and community assistance. All of these features were merged by Facebook in 2017 into a single resource known as the Crisis Response Centre (Nocak 2017).

"People affected by crises can find or offer help, stay updated on news and information, and let friends know they're safe" with the help of Crisis Response" (Facebook 2019).

Sadly, insufficient data gathering and limited access to reliable information can have a detrimental effect on emergency and humanitarian relief activities during times of disaster. On the other hand, by visualising data and hotspots, crowdsourcing crisis mapping may support efforts by facilitating the analysis and design of successful tactics. Prominent crisis mapping organisations and software resources comprise: UN Global Pulse, Crisis Mappers, Crisis Commons, Digital Humanitarian Networks, Ushahidi, Google Crisis Response, and the Standby Task Force (Skuse 2019).

A group of volunteers that volunteer for crisis mapping gathered information on the state of hospitals and clinics in the Bahamas following the destruction caused by Hurricane Dominic in 2019 and called themselves the Bahamas Standby Task Force. Maps have given first responders vital information on population mobility during emergencies as well as access to medical facilities and supplies, according to DirectRelief.org (Smith 2019).

Studies conducted on crowdsourcing responses to disasters such as flooding in Pakistan, wildfires in Colorado, and earthquakes and storms in Haiti have demonstrated that crowdsourcing helps emergency management prioritise and organise volunteers and resources more effectively. Online crowdsourcing has proven to be a potent and useful method for drawing resources to crisis situations and increasing public awareness, thanks to our global connection (Riccardi 2016).

References

Crowdsourcing, 2019, Merriam Webster, viewed 18 June 2024, <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/crowdsourcing>;.

Dunn, R 2014, The History, Longitude Prize.Org, viewed 18 June 2024, <https://longitudeprize.org/about-us/history>;.

Ghezzi, A, Gabelloni, D, Martini, A, & Natalicchio, A 2017, Crowdsourcing: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research’. International Journal of Management Reviews. 10.1111/ijmr.12135.

Nowak, M 2017, ‘A New Center for Crisis Response on Facebook’, Facebook Newsroom, viewed 18 June 2024, <https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/09/a-new-center-for-crisis-response-on-facebook/>;.

Skuse, A 2019, ‘Crowdsourcing and Crisis Mapping in Complex Emergencies’, Australian Civil-Military Centre or the Australian Government, viewed 18 June 2024, This paper is published under a Creative Commons license, viewed 18 June 2024, <https://www.adelaide.edu.au/accru/projects/ACMC2/Crowdsourcing_and_Crisis_Mapping_Final_ISBN.pdf>;.

Riccardi, M 2016, ‘The power of crowdsourcing in disaster response operations’ International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol 20, pp 123-128.

Smith, N 2019, ‘In Hurricane Dorian’s Wake, Maps Provide Essential Insights for First Responders’, DirectRelief.Org, viewed 18 June 2024, <https://www.directrelief.org/2019/08/in-hurricane-dorians-wake-maps-provide-essential-insights-for-first-responders/>;.

0 notes

Text

Week 12 | Crowdsourcing in Times of Crisis

Hello Humans! We'll be talking all about crowdsoursing today! Could we do something right here in this blog? Could we turn this blog into an example of crowdsourcing? Drop anything you can think of about crowdsourcing, to let others come to this blog to get information about crowdsourcing!

Now crowdsourcing, what is it? it is a practice where tasks or inputs are solicited from a large group of people, often via the internet, has proven to be a valuable tool in times of crisis. This approach leverages the collective intelligence and resources of a community to address challenges that may be beyond the capabilities of individual entities or traditional methods. During crises, such as natural disasters, pandemics, or humanitarian emergencies, crowdsourcing can facilitate rapid and effective responses, providing crucial support to affected populations.

One of the primary benefits of crowdsourcing in crisis situations is the speed at which information can be gathered and disseminated. For instance, during the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the Ushahidi platform enabled real-time mapping of crisis information by aggregating data from various sources, including social media, text messages, and emails (Meier, 2012). This crowdsourced information helped rescue teams prioritize their efforts and allocate resources more efficiently. Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, crowdsourced data platforms like Nextstrain provided real-time tracking of the virus's spread, aiding public health responses globally (Hadfield et al., 2018).

Crowdsourcing also promotes community engagement and empowerment. By involving local communities in the crisis response process, it ensures that the solutions are tailored to the specific needs and contexts of those affected. This participatory approach not only enhances the effectiveness of the response but also fosters resilience and self-reliance among community members. For example, during the Australian bushfires of 2019-2020, platforms like Fires Near Me allowed citizens to report and track fire incidents, contributing to a more coordinated and community-driven response (McLennan, 2020).

However, crowdsourcing in times of crisis is not without challenges. The accuracy and reliability of crowdsourced data can be problematic, as the information provided by untrained individuals may be inconsistent or erroneous. Furthermore, the sheer volume of data can be overwhelming, necessitating robust systems for filtering and verifying information. Addressing these challenges requires a combination of technological solutions, such as machine learning algorithms for data validation, and human oversight to ensure the credibility of the information (Goodchild & Glennon, 2010).

In conclusion, crowdsourcing is a powerful tool for crisis management, offering rapid information gathering, enhanced community involvement, and resource optimization. While challenges remain, the continued development of technological and organizational frameworks can harness the full potential of crowdsourcing to improve crisis response efforts.

References

Goodchild, M. F., & Glennon, J. A. (2010). Crowdsourcing geographic information for disaster response: a research frontier. International Journal of Digital Earth, 3(3), 231-241.

Hadfield, J., Megill, C., Bell, S. M., Huddleston, J., Potter, B., Callender, C., Sagulenko, P., Bedford, T., & Neher, R. A. (2018). Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics, 34(23), 4121-4123.

McLennan, B. (2020). Fires Near Me: The citizen-led bushfire information revolution. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 35(2), 20-25.

Meier, P. (2012). Crisis mapping in action: How open source software and global volunteer networks are changing the world, one map at a time. Journal of Map & Geography Libraries, 8(2), 89-100.

0 notes

Text

Crowdsourcing in times of crisis

Crowdsourcing, the practice of obtaining input or assistance from a large number of people, typically via the internet, has become an invaluable tool in times of crisis. It leverages the collective intelligence and resources of the public to address urgent and complex challenges. During emergencies, crowdsourcing can facilitate rapid information dissemination, resource mobilization, and innovative problem-solving, ultimately enhancing crisis response efforts.

One of the most notable applications of crowdsourcing in crises is disaster response. Platforms like Ushahidi, which originated during the 2008 Kenyan post-election violence, enable individuals to report incidents via SMS, email, or social media. These reports are then mapped in real-time, providing responders with critical information on affected areas. This technology has been used in various disasters, including the 2010 Haiti earthquake and the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, to coordinate aid and rescue operations more effectively.

Crowdsourcing also plays a vital role in public health emergencies. During the COVID-19 pandemic, crowdsourced data helped track the virus's spread and inform public health strategies. For instance, Johns Hopkins University developed an interactive dashboard that aggregates data from multiple sources, providing real-time updates on infection rates, recoveries, and fatalities worldwide. This crowdsourced information has been crucial for governments and health organizations in making informed decisions.

In addition to disaster and health crises, crowdsourcing has been instrumental in humanitarian efforts. Platforms like GoFundMe and GlobalGiving allow individuals to contribute financially to support those in need. These platforms can quickly mobilize funds for victims of natural disasters, conflicts, and other emergencies, providing immediate relief when traditional funding mechanisms might be slow to respond .

In conclusion, crowdsourcing in times of crisis harnesses the power of collective action to address urgent and complex challenges. Whether through real-time information sharing, financial support, or innovative problem-solving, crowdsourcing enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of crisis response efforts. As digital connectivity continues to grow, the potential for crowdsourcing to aid in crisis management will likely expand, offering new ways to leverage public participation in building resilient communities.

0 notes

Text

Week 12

Crowd Sourcing in Times of Crisis

Crowdsourcing is a powerful tool to gather real-time information, ideas or services from a large group of people, especially from an online community. It is a decentralised network that grasps the collective intelligence and efforts of the public to address challenges that arise during emergencies such as natural disasters, pandemics, or political issues. For example, the Ushahidi Haiti Project collected approximately 40,000 independent reports, and within a few hours, nearly 4,000 unique events were mapped (Yang et al., 2014). This has shown crowdsourcing plays a crucial role in real-time gathering information and enabling people to share and update information simultaneously.

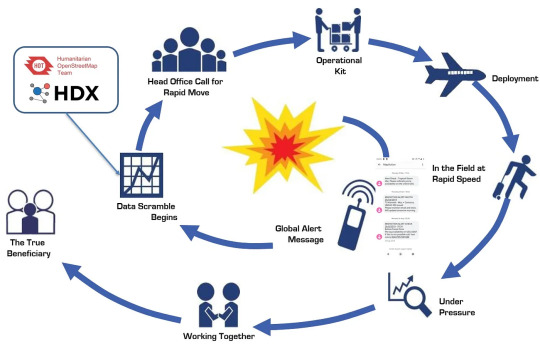

MapAction rapid response process.

Certainly, crowdsourcing is being utilised to help mobilise resources such as food, medical supplies, and volunteers. It allows diverse communities to collaborate and improve communication through online platforms. TopCoder, an online platform offering crowd-contest services, launched the Anti-Coronavirus Hackathon, an ideation challenge aimed at generating ideas from its community to assist people, governments, and organisations during the coronavirus outbreak (Vermicelli et al., 2020). Engaging the community in crisis response efforts fosters a sense of ownership and empowerment. Additionally, crowdsourcing encourages society to take the initiative to be involved in disaster response and recovery. For instance, the "Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team" entitles volunteers to create and update maps in areas affected by disasters, providing critical information for responders.

The accuracy of data, users’ privacy, and the digital divide have become the concerns of society. There is controversy about the compromise between the speed of information gathering and the accuracy of data. In crises, quick decisions are often necessary, but relying on unsubstantiated crowdsourced data can lead to misinformation and ineffective responses. In order to ensure the reliability of crowdsourced information, verification mechanisms and partnerships with trusted entities can help alleviate the risk of misinformation. Crowdsourcing in times of crisis offers multiple advantages, from rapid data collection to diverse problem-solving. However, it also presents challenges that integrate with data quality, privacy, and coordination. As technology evolves gradually, the rapid expansion of crowdsourcing makes it essential to confront these obstacles and leverage the collective strengths of the crowd in a responsible and ethical manner.

References:

Penson, S. (2021, December 13). Mapping for Humanitarian Response 2019 MapAction and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. Medium. https://medium.com/@steve.penson/mapping-for-humanitarian-response-2019

Vermicelli, S., Cricelli, L., & Grimaldi, M. (2020). How can crowdsourcing help tackle The COVID‐19 pandemic? An explorative overview of innovative collaborative practices. R & D Management, 51(2), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12443

Yang, D., Zhang, D., Frank, K., Robertson, P., Jennings, E., Roddy, M., & Lichtenstern, M. (2014). Providing real-time assistance in disaster relief by leveraging crowdsourcing power.Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 18(8), 20252034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-014 0758-3

0 notes

Text

Week 12: Crowd Sourcing in Times of Crisis

During a crisis, crowdsourcing is using a large number of people's knowledge, skills, and resources to solve urgent problems, typically through online platforms. In the event of a catastrophe, whether it be a natural disaster, a public health emergency, or a humanitarian crisis, this approach uses the brainpower of many individuals to collect and share current information, organise available resources, and aid affected communities.

Accurate and timely information is crucial for effective reaction and decision-making in times of crisis. With crowdsourcing, everyone can use social media, smartphone apps, or specialised platforms to report events, transmit updates, or offer first-hand opinions. Ushahidi and other social media hashtags allow anyone affected by natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes to report the damage, ask for help, and share location-specific information. In the event of an emergency, the real-time data can be invaluable in helping rescuers assess the situation and direct resources to the hardest hit areas. “One can easily identify the location, damages, severity of any disaster. Also there is a mechanism though which one can post the news on any social media.” (Mondal et al. 2017)

Quick distribution of necessities like food, medicine, and cash can be facilitated through crowdsourcing. Facebook Fundraisers, GoFundMe, and Kickstarter are just a few of the platforms that organisations and individuals can use to quickly collect money for relief efforts. Also, by matching skills and availability with needs, crowdsourcing makes it easier to organise volunteers. Masks for All and similar initiatives saw individuals all around the globe making and distributing masks to vulnerable populations and healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks to everyone working together online, this was a reality.

Creative and adaptable problem-solving skills are essential in times of crisis. In order to solve complex problems, crowdsourcing encourages a diverse group of people to share their knowledge, expertise, and ideas. In the event of a public health emergency, academics and medical experts can collaborate on therapy development and improvement utilising platforms like Foldit and OpenAI. In addition, online competitions and hackathons can be organised to bring people together to solve technical problems; for example, making contact tracking apps or resource management platforms.

In times of disaster, crowdsourcing can provide much-needed psychological and emotional support in addition to practical information and resources. Support groups and online communities provide a safe space for people to talk to one another, share advice, and lift each other up emotionally. “Social media are capable of revealing some aspects of the mental and emotional state of a nation”(Alexander 2013). Support networks on platforms like Reddit, Facebook Groups, and niche forums can be invaluable in helping people cope with the emotional and mental challenges that crisis situations inevitably bring.

In a nutshell, crowdsourcing is a way for people to pool their resources, share current knowledge, find solutions to problems, and help their communities during times of need. This strategy enhances the effectiveness and efficiency of disaster response efforts by utilising the diverse knowledge and perspectives of a broad group of individuals. As a result, more lives are saved and communities are rebuilt.

References

Mondal, T, Bhattacharya, I, Roy, J & Maity, M 2017, “Use of Infrastructure-Less Network Architecture for Crowd Sourcing and Periodic Report Generation in Post Disaster Scenario,” Communications in computer and information science, pp. 230–239, viewed <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6427-2_19>.

Alexander, DE 2013, “Social Media in Disaster Risk Reduction and Crisis Management,” Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 717–733, viewed <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-013-9502-z>.

0 notes

Text

Week 12: Crowdsourcing in Times of Crisis

When a crisis arises, every second matters. Conventional approaches to information collection and response can be laborious and slow. This is where crowdsourcing comes into play, providing a potent instrument to harness the resources and combined knowledge of the populace.

By using the Internet, social media, and smartphone apps, a huge number of individuals can contribute their work, information, or opinions through a process known as crowdsourcing (Hargrave 2022). A few examples of crowdsourcing:

Data collection: Compiling details regarding the magnitude of the damage, the places impacted, and the immediate requirements on the ground. Crisis mapping: charting places that are inundated, infrastructure that is damaged, or roads that are closed in real time. Search and rescue: Making use of social media posts and eyewitness accounts to find those who have gone missing. Fundraising: To support relief efforts and long-term rehabilitation, crowdfunding platforms can help raise crucial finances.

A few advantages of crowdsourcing are reach and speed. Crowdsourcing enables quick information collection and distribution, which is essential during the vital initial hours of a crisis. Local knowledge. The most recent information about the situation is frequently held by those who are physically there. Scalability. Crowdsourcing can draw from a large pool of resources, including local knowledge and technological know-how. Lastly, an increased involvement from the public and openness.

And the disadvantages of crowdsourcing are as such, depending on the crowd that is being sourced, results can be easily distorted. Lack of ownership or secrecy regarding an idea. Possibility of missing the finest opportunities, skills, or guidance and failing to achieve the intended outcome (Hargrave 2022).

The topic of crowdsourcing is quickly developing and has enormous promise for disaster response. Through addressing the obstacles and incorporating crowdsourcing into official response plans, we may develop a more effective and human-centered crisis management strategy. Sites for crowdsourcing, such as Ushahidi, were essential in mapping damaged infrastructure and locating survivors after the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Relief efforts during Hurricane Sandy were supported by crowdsourcing data on flooded streets and power shortages.

Here are a few things that you can do:

Seek out reputable crowdsourcing websites that are operational during emergencies.

Contribute responsibly by checking facts before sharing them and avoiding starting rumours.

If you are skilled in a certain area (translation, data analysis), think about offering your services online as a volunteer.

And so, you may use the strength of the public to transform a catastrophe into a chance for cooperation and fortitude.

References

Hargrave, M 2022, “Crowdsourcing: Definition, How It Works, Types, and Examples,” Investopedia, accessed 14 June 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/crowdsourcing.asp

0 notes

Text

Reality TV and Digital Publics: An Exploration

This week’s lecture focused on the complex interplay between reality TV and social media, highlighting how digital publics form and engage within the public sphere. The discussion provided historical context, explored key concepts, and examined the role of social media in reshaping audience interaction and engagement.

Key Concepts: Digital Publics and the Public Sphere

The public sphere is traditionally defined as a space where private individuals come together to discuss and influence political change (Kruse, 2018; Sakariassen, 2020). With the advent of social media, this concept has evolved into multiple digital publics, which are micro-communities formed around specific platforms and issues. Examples include hashtags like #Auspol and Tumblr fandoms.

Historical and Contemporary Context of Crowdsourcing

Crowdsourcing is not a novel concept. Historical examples such as the British government's Longitude Prize in 1714 and the Oxford English Dictionary’s reliance on 800 readers in 1884 illustrate early forms of distributed problem-solving (Chrum, 2013). In modern times, platforms like Ushahidi have been pivotal in crisis mapping, highlighting how digital technologies can mobilize citizens and unify views during crises.

Reality TV: Definitions and Audience Paradoxes

Reality TV, a dominant television genre for over 20 years, encompasses a wide range of sub-genres including gamedocs, talent contests, and celebrity-based programs (Murray & Ouellette, 2009). Despite its popularity, reality TV is often cited as the least favorite genre among surveyed audiences (Statista, 2022). This paradox underscores the complex relationship audiences have with reality TV, where they engage heavily but express disdain for the genre.

Reality TV and Social Media: Transforming Engagement

Reality TV has leveraged social media to diversify markets and enhance audience participation. Social media platforms enable reality TV stars and fans to interact across various channels, fostering a dynamic and participatory culture (Arcy, 2018). This multiplatform engagement creates digital publics where everyday political talk and social issues are discussed, reflecting the intersection of personal and political spheres (Graham & Hajru, 2011).

Case Studies: Malaysian Digital Publics and Tumblr

In Malaysia, platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook dominate digital public spaces, enabling citizens to mobilize and engage in community building (Castells, 2015). Similarly, Tumblr provides a safe space for marginalized voices, particularly for trans and gender-diverse individuals, offering a supportive environment distinct from platforms like Facebook and Instagram (Byron et al., 2019).

Implications for Broadcasters and Audiences

The convergence of reality TV and social media benefits broadcasters through increased viewer engagement and ratings. However, it also exposes participants to intense public scrutiny and potential harassment. The phenomenon of reality TV fame highlights the thin line between celebrity and ordinary individuals, with social media amplifying both positive and negative interactions (Porter, 2015).

Conclusion

The exploration of reality TV and digital publics reveals the transformative impact of social media on audience engagement and the formation of digital communities. These platforms facilitate dynamic interactions that blur the lines between personal and political spheres, reflecting broader societal trends and challenges. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for comprehending the evolving landscape of media and public discourse.

References

Arcy, J. (2018). The digital money shot: Twitter wars, The Real Housewives, and transmedia storytelling. Celebrity Studies.

Byron, P., Robards, B., Hanckel, B., Vivienne, S., & Churchill, B. (2019). Safety, visibility and interaction on LGBTQ social media platforms. Media International Australia, 171(1), 127-138.

Castells, M. (2015). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the internet age. Polity Press.

Chrum, J. (2013). Crowdsourcing: Definition and History. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from hbr.org.

Graham, T., & Hajru, A. (2011). Reality TV as a trigger of everyday political talk in the net-based public sphere. European Journal of Communication.

Kruse, M. (2018). The public sphere: Definitions and theories. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 42(1), 5-17.

Murray, S., & Ouellette, L. (2009). Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture. NYU Press.

Porter, T. (2015). Digital fandom: New media studies. Routledge.

Sakariassen, H. (2020). Public sphere revisited: Theories and debates. Media Studies Quarterly, 38(2), 89-104.

Statista. (2022). Popularity of reality TV among U.S. audiences. Retrieved from statista.com.

0 notes

Text

Week 12: Crowd sourcing in times of crisis

welcome back to nn’s blog ˙✧˖°🌎 ༘ ⋆。˚

Hello there my wonderful peeps! I hope you’re doing well. This is going to be my last blog post for the semester, and I wanted to end on something incredibly powerful and uplifting topic – Crowdsourcing in Times of Crisis. Let’s dive into how people come together online to make a real difference when the world needs it most.

So, what exactly is crowdsourcing? At its core, it’s about leveraging the collective power of a large group of people to solve problems, gather information, or generate ideas. When a crisis hits, whether it’s a natural disaster, a pandemic, or a humanitarian emergency, crowdsourcing becomes a vital tool for quick and effective response (Howe 2006).

Let’s rewind to some real-world examples.

Do you guys remember the devastating Australian bushfires in 2019-2020? Social media was flooded with posts asking for donations, sharing information about safe havens for wildlife, and even coordinating volunteer efforts. Platforms like GoFundMe saw an outpouring of support, with people from all over the world donating to help those affected. One standout moment was when comedian Celeste Barber’s Facebook fundraiser raised over $50 million for firefighting services, showcasing the immense impact of digital communities rallying together (BBC News 2020).

ABC News reported about Celeste Barber raised $51 million for RFS & Brigades Donations Fund

While we often think of modern examples, the concept of collective action has been around for centuries. Take the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake in China, the deadliest earthquake in recorded history. Though there was no technology for crowdsourcing as we know it today, the communities banded together in remarkable ways. Local citizens and officials worked collectively to rebuild homes, share resources, and support each other through the aftermath. This historical example highlights the timeless nature of collective action in crisis situations (Spence et al. 2021).

The story about 1556 Shaanxi, China earthquake

Fast forward to the Sabah Mount Kinabalu earthquake in 2015. This disaster struck the beautiful Mount Kinabalu in Malaysia, leaving many stranded and in need of immediate assistance. Social media and crowdsourcing platforms became essential tools. People used Twitter and Facebook to share real-time updates, call for help, and coordinate rescue efforts. Volunteers, rescue teams, and locals collaborated through these channels to ensure a swift response, demonstrating the power of collective action in the face of tragedy (The Straits Times 2015).

The Straits Times reported about Sabah Mount Kinabalu earthquake in 2015

And let's not forget the power of information. During crises, crowdsourced information can be a lifesaver. Tools like Google’s Person Finder help reconnect people with loved ones after a disaster, while platforms like Ushahidi map reports from the ground in real-time, offering a clearer picture of what’s happening and where help is needed most.

The beauty of crowdsourcing lies in its democratizing power. It breaks down barriers, allowing anyone with an internet connection to contribute to meaningful solutions. However, it’s not without challenges. Ensuring the accuracy of information, coordinating large-scale efforts, and maintaining security are critical issues that need constant attention.

So, what’s the takeaway? Crowdsourcing leverages the collective power of individuals to provide support, share information, and bring about real change during crises.

"What we can achieve when we come together, even if only digitally."

This is the end of my blog for today! As this semester comes to an end, I just wanna say a huge thank you to all of you who’ve read my blogs! Thanks for being part of this journey 🫶🏻

Until next time! See ya <3

Reference

BBC News 2020, 'Australian bushfires: Celeste Barber's fundraiser reaches $50m', BBC News, 6 January, viewed 9 June 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-51002889.

Howe, J 2006, 'The rise of crowdsourcing', Wired, vol. 14, no. 6, viewed 9 June 2024, https://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/.

Spence, P, Lachlan, K, Lin, X & Del Greco, M 2021, 'Collective action in times of crisis: An analysis of the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake', Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 71, pp. 36-44.

The Straits Times 2015, 'Mount Kinabalu earthquake: Social media abuzz with news of rescue efforts', The Straits Times, 7 June, viewed 9 June 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/mount-kinabalu-earthquake-social-media-abuzz-with-news-of-rescue-efforts.

0 notes

Text

Week 12: Crowdsourcing: Harnessing Collective Power in Times of Crisis

In moments of crisis, whether it's a natural disaster or a global emergency, crowdsourcing becomes a powerful tool for bringing people together to help. Crowdsourcing means asking a large group of people, often through the internet, to share their knowledge and resources to solve problems and support each other. This approach has revolutionized how we respond to emergencies and disasters around the world (Hargrave 2022).

Crowdsourcing emerges as a crucial lifeline during times of crisis, revolutionizing how communities respond and recover from disasters. In the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake in 2010, platforms like Ushahidi utilized SMS and online forms to gather vital reports directly from affected locals. This real-time data was then mapped out, pinpointing areas where aid was urgently needed and enabling relief organizations to allocate resources efficiently (Ford 2012). Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, social media became a powerful tool for crowdsourcing, connecting individuals with critical resources like oxygen cylinders, hospital beds, and vaccine information through hashtags such as #COVIDRelief and #COVID19Help. These initiatives not only facilitated rapid information dissemination but also mobilized collective action, demonstrating the transformative impact of crowdsourcing in enhancing disaster response and community resilience.

In addition, social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have revolutionized crisis response efforts by enabling real-time crowdsourcing of vital information. During natural disasters like hurricanes and typhoons, affected communities leverage hashtags to disseminate urgent updates on evacuation routes, shelter availability, and critical needs such as food and water. This rapid sharing of information enables volunteers, relief organizations, and authorities to respond swiftly, ensuring timely assistance reaches those in distress. Similarly, in regions prone to wildfires and floods, residents utilize social media to warn others about impending dangers, share safety tips, and coordinate community-driven initiatives aimed at supporting affected individuals and communities. This grassroots approach facilitated by social media underscores its pivotal role in enhancing disaster preparedness and response strategies worldwide.

Conclusion: Coming Together to Make a Difference

Crowdsourcing demonstrates the power of collective action. By leveraging technology and collective knowledge, communities can respond more effectively to crises, save lives, and build resilience. It's about harnessing the strength of many to overcome challenges that no single entity could tackle alone.

In summary, crowdsourcing isn't just a tool it's a testament to human compassion and solidarity. By connecting people globally and locally, we can create a future where every voice is heard, and every contribution makes a meaningful impact in times of need.

Reference

Ford, H 2012, 'Witnesses to disasters: From documentary realism to collective intelligence', in M Farman (ed.), The Mobile Story: Narrative Practices with Locative Technologies, Routledge, pp. 31-44.

Hargrave, M 2022, Crowdsourcing: Definition, How It Works, Types, and Examples, Investopedia, viewed 16 Jun 2024, <https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/crowdsourcing.asp>.

0 notes

Text

Week 12: Crowdsourcing

In the midst of a period that is marked by an increasing frequency and severity of emergencies, ranging from environmental catastrophes to global health crises, crowdsourcing has emerged as a powerful instrument for the purpose of mobilising resources, gathering information, and stimulating innovation. This collaborative approach makes use of the numerous abilities and points of view of individuals from all over the world, so giving a method that is both flexible and adaptive in order to address complex and urgent issues. (Desai, Kuderer & Lyman 2020) An examination of the various applications of crowdsourcing in crisis management is presented in this essay. These applications are illustrated through prominent examples, and the study also discusses the inherent challenges and variables that need to be taken into consideration.

The rapid collection and dissemination of information is an immediate and practical application of crowdsourcing that can be utilized during times of need. During times of natural disasters, social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have become increasingly important means for receiving information that is up to the minute. Those who live in areas that have been affected are able to share their own experiences with regard to the level of destruction, the immediate needs, and the current status of safety. (Desai, Kuderer & Lyman 2020) This information distribution from the bottom up has the potential to improve official reporting, thereby providing a more comprehensive picture of the matter. One outstanding example is the Ushahidi platform, which was initially developed to record instances of violence that occurred in Kenya during the elections that took place in 2008. Ushahidi has been utilized all over the world to collect information from the general population during times of emergency, such as the earthquake that occurred in Haiti in 2010 and the tsunami that occurred in Japan in 2011. As a result of collecting data from a variety of sources, Ushahidi helps to validate information and improve decision-making, hence reducing the amount of erroneous information that is distributed. (Meier 2012)

When a crisis is occurring, it is absolutely necessary to distribute resources as quickly as possible. Platforms that facilitate crowdsourcing make this process more effective by enabling a wide range of individuals to contribute resources, including money and materials. It is important to note that crowdfunding platforms like GoFundMe and Kickstarter have been essential in the process of raising financial support for relief efforts that are urgently needed. This demonstrates the power of collective action by allowing for the quick accumulation of modest contributions from a considerable number of individuals. These platforms assist the aggregation of these contributions. During the COVID-19 epidemic, a large number of crowdfunding initiatives were launched in order to provide assistance to healthcare workers, supply personal protective equipment (PPE), and finance research endeavors. As a result of the success of these efforts, the effectiveness and potential of crowdsourcing in terms of mobilizing resources during times of global crisis have been demonstrated. (Mollick 2014)

The utilisation of the collective intelligence of the global community is what makes crowdsourcing a useful tool for fostering innovation. With the ability to issue open solicitations for responses to specific challenges brought about by crises, governments and organisations have the opportunity to communicate their needs. This method not only speeds up the process of finding solutions to problems, but it also brings in a diverse range of perspectives and technical knowledge.

Through the utilisation of crowdsourcing, it has been demonstrated that it has the capability to significantly enhance disaster management and recovery efforts. The strategy offers a flexible and adaptive approach to dealing with the complex challenges that are brought about by crises. This is accomplished by harnessing the combined strength of individuals. The strength of collective action during times of urgency is demonstrated by crowdsourcing, which encompasses actions such as the collection of information, the mobilization of resources, the resolution of any problems that may arise, and the coordination of volunteer efforts.

References

Desai, A, Kuderer, NM & Lyman, GH 2020, ‘Crowdsourcing in Crisis: Rising to the Occasion’, JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics, no. 4, pp. 551–554.

Meier, P 2012, 'Crisis Mapping in Action: How Open Source Software and Global Volunteer Networks Are Changing the World, One Map at a Time', Journal of Map & Geography Libraries, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 89-100.

Mollick, E 2014, 'The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study', Journal of Business Venturing, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 1-16.

0 notes