#until I can get a lumbar puncture and drain the fluid and/or confirm the diagnosis it’s going to get worse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The whole time I was writing my fanfic I was like Geeze! it is getting harder and harder for me to do spelling and grammar, and I am sometimes entirely blind to misspellings and missing words in sentences. I guess it’s just writing a long story that’s doing it!

Anyway, turns out my body is producing too much fluid and my brain has been literally been getting increasingly squished for the last six months

#I am trying to find a funny way to talk about my brain condition and this is the closest I’ve come#other than that if I laughed too hard sometimes I nearly passed out#I just found out this week and nothing is formally confirmed yet but yeah#I found out by pure coincidence and it rocks me a little#I probably wouldn’t have found out until I went blind#so yes please be kind if you read my stuff and it’s a bit wonky#until I can get a lumbar puncture and drain the fluid and/or confirm the diagnosis it’s going to get worse#and then it’s likely it’ll just happen forever#I’m good on cerebrospinal fluid brain but i appreciate the thought

1 note

·

View note

Text

Brain Parasites: Part I.

In some parts of the world, brain infections may be due to worms or other parasites. These infections are more common in developing countries and rural areas. They are less common in the United States. Trichinella Spiralis, A Parasitic Roundworm

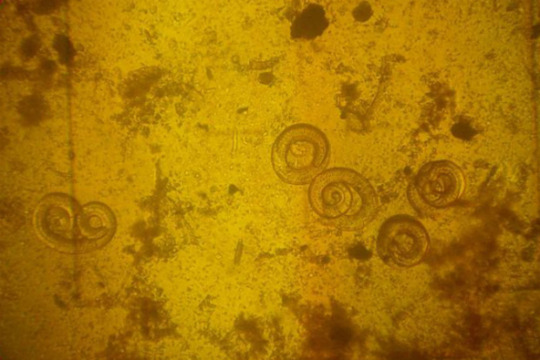

Trichinosis is a disease caused by parasitic roundworms (nematodes) that can infect and damage body tissues. Nematodes are a major division of the helminth family of parasitic worms (for example, Trichinella spiralis). When ingested, these parasitic worms can pass through the intestinal tract to invade other tissues, such as muscle, where they persist. Trichinosis is also termed trichinellosis, trichiniasis, or trichinelliasis. Trichinosis is caused by Trichinella species (parasitic nematodes, intestinal worms, and roundworms) that initially enter the body when meat containing the Trichinella cysts (roundworm larvae) is eaten. For humans, undercooked or raw pork and pork products, such as pork sausage, has been the meat most commonly responsible for transmitting the Trichinellaparasites. It is a food-borne infection and not contagious from one human to another unless infected human muscle is eaten. However, almost any carnivore (meat eater) or omnivore (eats meat and plants for food) can both become infected and, if eaten, can transmit the disease to other carnivores and omnivores. For example, undercooked or raw bear meat can contain livable Trichinella cysts. Therefore, if humans, dogs, pigs, rats, or mice eat the meat, they can become infected. In rare instances, larvae in cattle feed can infect cattle. There are six species that are known to infect humans:T. spiralis found in many carnivorous and omnivorous animals worldwide.T. britovi found in carnivorous animals in Europe and Asia.T. pseudospiralis found in mammals and birds worldwide.T. nativa found in arctic mammals (for example, bears, foxes).T. nelsoni found in African mammals (for example, lions, hyenas).T. murrelli found in wild animals in the U.S. Cysticercosis

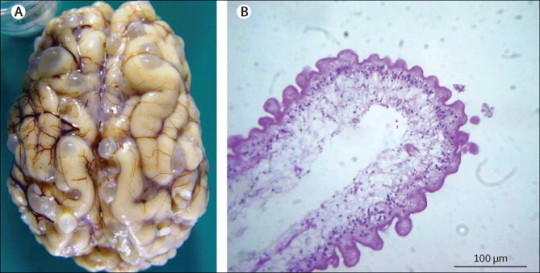

This infection is caused by pork tapeworm larvae. It is the most common parasitic infection in the Western Hemisphere. After people eat food contaminated with cysticercus eggs, secretions in the stomach cause the eggs to hatch into larvae. The larvae enter the bloodstream and are distributed to all parts of the body, including the brain. The larvae form cysts (clusters of larvae enclosed in a protective wall). These cysts can cause headaches and seizures. The cysts degenerate and the larvae die, triggering inflammation, swelling, and symptoms such as headaches, seizures, personality changes, and mental impairment.

Sometimes the cysts block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid within the spaces of the brain (ventricles) putting pressure on the brain. This disorder is called hydrocephalus. The increased pressure can cause headaches, nausea, vomiting, and sleepiness. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) can often show the cysts. But blood tests and a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to obtain a sample of cerebrospinal fluid are often needed to confirm the diagnosis.

The infection is treated with albendazole or praziquantel (drugs used to treat parasitic worm infections, called antihelminthic drugs). Corticosteroids are given to reduce the inflammation that occurs as the larvae die. Seizures are treated with anticonvulsants.

Occasionally, surgery is necessary to place a drain (shunt) to remove the excess cerebrospinal fluid and relieve the hydrocephalus. The shunt is a piece of plastic tubing placed in the spaces within the brain. The tubing is run under the skin, usually to the abdomen, where excess fluid can drain. Surgery to remove cysts from the brain may also be needed. Naegleria fowleri

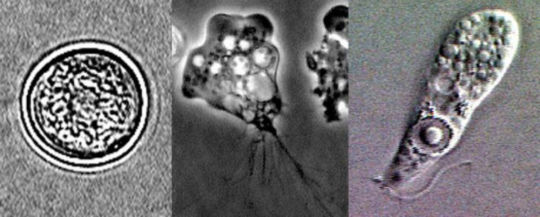

Naegleria fowleri is a heat-loving (thermophilic), free-living ameba (single-celled microbe), commonly found around the world in warm fresh water (like lakes, rivers, and hot springs) and soil. Naegleria fowleri is the only species of Naegleria known to infect people. Most of the time, Naegleria fowleri lives in freshwater habitats by feeding on bacteria. However, in rare instances, the ameba can infect humans by entering the nose during water-related activities. Once in the nose, the ameba travels to the brain and causes a severe brain infection called primary meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is usually fatal. Naegleria fowleri has 3 stages in its life cycle: cyst, trophozoite, and flagellate. The only infective stage of the ameba is the trophozoite. Trophozoites are 10-35 µm long with a granular appearance and a single nucleus. The trophozoites replicate by binary division during which the nuclear membrane remains intact (a process called promitosis). Trophozoites infect humans or animals by penetrating the nasal tissue and migrating to the brain via the olfactory nerves causing primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Trophozoites can turn into a temporary, non-feeding, flagellated stage (10-16 µm in length) when stimulated by adverse environmental changes such as a reduced food source. They revert back to the trophozoite stage when favorable conditions return. Naegleria fowleri trophozoites are found in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and tissue, while flagellated forms are occasionally found in CSF. Cysts are not seen in brain tissue. If the environment is not conducive to continued feeding and growth (like cold temperatures, food becomes scarce) the ameba or flagellate will form a cyst. The cyst form is spherical and about 7-15 µm in diameter. It has a smooth, single-layered wall with a single nucleus. Cysts are environmentally resistant in order to increase the chances of survival until better environmental conditions occur. N. fowleri can spend long spans of time just hanging around as a cyst, a little armored ball that can survive cold, heat, and dry conditions. When a cyst comes into contact with an inviting host, it sprouts tentacle-like pseudopods and turns into a form known as a trophozoite. Once it’s transformed, the trophozoite heads straight for the host’s central nervous system, following nerve fibers inward in search of the brain. Once it’s burrowed into its host’s brain tissue — usually the olfactory bulbs — N. fowleri sprouts a “sucking apparatus” called an amoebostome and starts chowing down on juicy brain matter. As the amoeba divides, multiplies and moves inward, devouring brain cells as it goes, its hosts can go from uncomfortable to incoherent to unconscious in a matter of hours.The symptoms start subtly, with alterations in tastes and smells, and maybe some fever and stiffness. But over the next few days, as N. fowleri burrows deeper into the brain’s cognitive structures, victims start feeling confused, have trouble paying attention, and begin to hallucinate. Next come seizures and unconsciousness, as the brain loses all control. Two weeks later, the victim’s most likely perishes — although one man in Taiwan managed to stick it out for a grueling 25 days before his nervous system finally gave out.Although N. fowleri infections are rare in the extreme — worldwide historical totals number only in the hundreds — they’re almost always fatal, and tricky to catch and treat before they spiral out of control. Even so, you’d be wise to avoid warm pools of still water, lest you end up with an uninvited guest on the brain. Loa Loa

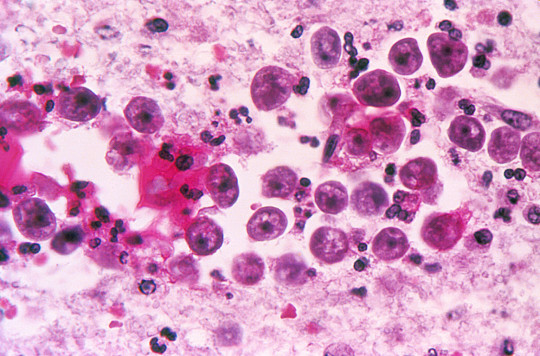

Loiasis, called African eye worm by most people, is caused by the parasitic worm Loa loa. It is passed on to humans through the repeated bites of deerflies (also known as mango flies or mangrove flies) of the genus Chrysops. The flies that pass on the parasite breed in certain rain forests of West and Central Africa. Infection with the parasite can also cause repeated episodes of itchy swellings of the body known as Calabar swellings. Knowing whether someone has a Loa loa infection has become more important in Africa because the presence of people with Loa loa infection has limited programs to control or eliminate onchocerciasis (river blindness) and lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis). There may be more than 29 million people who are at risk of getting loaisis in affected areas of Central and West Africa. The deerflies (genus Chrysops) that pass Loa loa on to humans bite during the day. If a deerfly eats infected blood from an infected human, the larvae (non-adult parasites) will infect cells in its abdomen. After 7–12 days the larvae develop the ability to infect humans. Then the larvae move to the mouth parts of the fly. When the deerfly breaks a human’s skin to eat blood, the larvae enter the wound and begin moving through the person’s body.It takes about five months for larvae to become adult worms inside the human body. Larvae can become adults only inside the human body. The adult worms live between layers of connective tissue (e.g., ligaments, tendons) under the skin and between the thin layers of tissue that cover muscles (fascia). Fertilized females can make thousands of microfilariae a day. The microfilaria then move into the lymph vessels of the body (the lymph vessels contain the blood cells that fight infection). Eventually they move into the lungs where they spend most of their time. These microfilariae enter the blood from time to time, usually around midday. It takes five or more months for microfilariae to be found in the blood after someone is infected with Loa loa. The microfilariae can live up to one year in the human body. If they are not consumed in a blood meal by a deerfly they will die. Adult worms may live up to 17 years in the human body and can continue to make new microfilariae for much of this time.Most people with loiasis do not have any symptoms. People who get infected while visiting areas with loiasis but do not come from areas where loiasis is found (travelers) are more likely to have symptoms. The most common manifestations of the disease are Calabar swellings and eye worm. Calabar swellings are localized, non-tender swellings usually found on the arms and legs and near joints. Itching can occur around the area of swelling or can occur all over the body. Eye worm is the visible movement of the adult worm across the surface of the eye. Eye worm can cause eye congestion, itching, pain, and light sensitivity. Although eye worm can be scary, it lasts less than one week (often just hours) and usually causes very little damage to the eye. People with loiasis can have itching all over the body (even when they do not have Calabar swellings), hives, muscle pains, joint pains, and tiredness. Sometimes adult worms can be seen moving under the skin. High numbers of blood cells called eosinophils are sometimes found on blood counts. Some people who are infected for many years may develop kidney damage though development of permanent kidney damage is not common. Other rare manifestations include painful swellings of lymph glands, scrotal swellings, inflammation of parts of the lungs, fluid collections around the lung, and scarring of heart muscle. The vector for Loa loa filariasis are flies from two species of the genus Chrysops, C. silacea and C. dimidiata. During a blood meal, an infected fly (genus Chrysops, day-biting flies) introduces third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human host, where they penetrate into the bite wound . The larvae develop into adults that commonly reside in subcutaneous tissue . The female worms measure 40 to 70 mm in length and 0.5 mm in diameter, while the males measure 30 to 34 mm in length and 0.35 to 0.43 mm in diameter. Adults produce microfilariae measuring 250 to 300 μm by 6 to 8 μm, which are sheathed and have diurnal periodicity. Microfilariae have been recovered from spinal fluids, urine, and sputum. During the day they are found in peripheral blood, but during the noncirculation phase, they are found in the lungs . The fly ingests microfilariae during a blood meal. After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and migrate from the fly's midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles of the arthropod. There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae. The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the fly's proboscis and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal.

69 notes

·

View notes