#unitierra califas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[Unitierracalifas] UT Califas Demo Ateneo, 5-26-18, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañerxs: We will convene the Universidad de la Tierra Democracy Ateneo this coming Saturday, May 26, 2018 in San Jose at Casa de Vicky (792 E. Julian St., San Jose) from 2.00-5.00 p.m. to resume our regularly scheduled reflection and action space and to explore some of the questions and struggles mentioned below that are raised by the current conjuncture in which we find ourselves.

Ghada Karmi informs us that "between 30 March and 11 May Israeli forces shot dead more than 40 unarmed Palestinians and wounded over 2,000 during the Great March of Return series of protests in Gaza. On 14 May alone, in protests coinciding with the opening of the US embassy in Jerusalem, Israeli soldiers killed a further 58 Palestinians and wounded nearly 2,800." (see, G. Karmi, "At 70 Israel is a Bellicose Giant.") She also highlights how Israel continues its bullying attacks against other sovereign nations including calling for the assassination of leaders in the region. This, of course, is only possible through the backing of the U.S. and other western nations. The relationship between the U.S. and Israel is more than simply an alliance between two sovereign powers. Israel's connection with the U.S. is such that the one nation can orchestrate a falsehood that can then become the dominant story repeated by the the other, circulated by the U.S. political class, pundits, and mainstream media supported by think tanks, lobby groups, and media manipulators, such as pollsters and communication strategists, and, increasingly, by universities and academic institutions that have marginalized pro-Palestinian faculty. In this instance, the orchestrated falsehood is that the rebellion organized in conjunction with the recognition of the Nakba of 1948 is nothing more than attacks by Hamas. More than one critical media analyst recognizes this as nothing less than propaganda, the propaganda common to fascism. The resistance of the people is framed as terrorist violence. Yet not everyone was so ready to buy the well orchestrated lies as solidarity actions and resistances erupted across the globe in support of Palestine —Tel Aviv, South Africa, Brussels, New York. In San Francisco, chants of Palestine will be free! rose up from the streets as people marched from the Israeli Consulate in the city's Financial District to Federal Building in Civic Center (See, Sarah Ruiz-Grossman, "Hundreds in Israel and Beyond Protest Killings of Palestinians on Gaza Border.") The following day also in San Francisco, the disruption of a planned book talk by former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak resulted in eighteen arrests as those present interrupted and drowned out Barak's talk repeatedly, condemned him as a war criminal (see, Palestine Action Network, "Eighteen Arrested as Activists Shout Down Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak in San Francisco for War Crimes.")

We are reminded of Aimee Cesaire's observation when examining the brutality of colonization, and that in the context of discussions about the rise of fascism and the Second World War. According to Cesaire: "They [the atrocities of colonization] prove that colonization, I repeat, dehumanizes even the most civilized man; that colonial activity, colonial enterprise, colonial conquest, which is based on contempt for the native and justified by that contempt, inevitably tends to change him who undertakes it; that the colonizer, who in order to ease his conscience gets into the habit of seeing the other man as an animal, accustoms himself to treating him like an animal, and tends objectively to transform himself into an animal. It is this result, this boomerang effect of colonization that I wanted to point out." (see, A. Cesaire, Discourse on Colonialism, p.41) Israel's settler colonialism project has reached its apex, that is, the level of barbarity that is the natural evolution of colonial occupation. The colonizer loses his or her humanity and is capable of all manner of atrocities blinded by their own righteousness. And it is no wonder that Israel basks in the support of the U.S. Americans, if they are even aware of the violence may be momentarily appalled by the atrocities they witnessed these past few weeks in Gaza. Yet, they, "the respectable bourgeois," nonetheless maintain a system where the state apparatus, all of the elements of it, become an echo chamber for Israel's justification of a genocidal project they have been executing with impunity for seventy years, building on a settler colonial logic and program stretching back to the First Zionist Conference and the Basel Program of August 1897. Colonial and imperial powers, including the U.S. in the post World War II era, continue to rely on Israel for their purposes, that is for their own geopolitical designs for the region. And it is this moment, the moment that W.E.B Du Bois named democratic despotism that is the fundamental cause of all wars. It is the bargain the white working class makes with capital. The bargain is based on the quid pro quo that capital gets a compliant workforce and white labor enjoys a somewhat slightly higher wage, safer working conditions, more leisure time, and the few toys and trinkets of a bourgeois lifestyle, and all of that at the expense of Black and Brown labor and lives at home and abroad. In other words, the bargain can only be fulfilled through, according to Du Bois, colonialism which is to say war. (see, Du Bois, "African Roots of War.") The ethnic Mexican community shares an awareness of the nature of democratic despotism and its ties to war. We have resisted the imposition of the "Mexican wage" as well as fought for access and inclusion in all of America's dominant institutions since the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 that articulated the expanded borders of the settler colony. Rather than marking the end of the war, the treaty also articulated the promise of a continuous social war organized around the criminalization of resistance. This has been our plight as Chicanxs and Latinxs in the U.S. —to confront successive strategies of criminalization intertwined with militarization. It is a long standing process that has its most recent articulation in the attack on the immigrant community orchestrated through the elimination of TSP (Temporary Protected Status), DACA, and the deliberately orchestrated home, work, and street invasions and sweeps conducted by ICE, INS, and the Border Patrol, working in conjunction with local law enforcement and private prisons. All of this occurs against the backdrop of increased levels of border militarization that continue to produce numbers of deaths despite the drop in immigration as a whole. And, of course, the violence on one side of the border is linked to the violence on the other side —a violence of kidnappings, assassinations, disappearances, feminicides, and massacres. The colonist's disdain for the ethnic Mexican community of Greater Mexico was on display this week when New York Attorney Aaron Schlossberg excoriated patrons and staff at a Midtown Fresh Kitchen for speaking Spanish and a barrista at a Starbucks in La Cañada Flintridge on the outskirts of Los Angeles wrote "beaner" on the coffee cup of an order placed by a cook only identified as Pedro. (see, Y. Simón, "After Racist Lawyer Goes Viral" and A. Cataño, California Starbucks Employee Writes Racial Slur") Both moments may seem trivial compared to the levels of violence throughout Mexico, across the border, and in the neighborhood, but each also reflects a level of dehumanization common to racial capitalism, settler colonial states, and the fascism that defines them. What connects these locuses of violence besides the trajectories of settler colonialism outlined by Cesaire? It's war. "War, money, and the State are constitutive or constituent forces, in other words the ontological forces of capitalism," explain Éric Alliez and Maurizio Lazzarato. To this they add, "the critique of political economy is insufficient to the extent that the economy does not replace war but continues it by other means, ones that go necessarily through the State: monetary regulation and the legitimate monopoly on force for internal and external wars. To produce the genealogy of capitalism and reconstruct its 'development,' we must always engage and articulate together the critique of political economy, critique of war, and critique of the State." (see, E. Alliez and M. Lazzarato, Wars and Capital, p. 15.) It’s total war. But, the total war is not new. It’s colonial war directed everywhere, no longer confined to the colony. Alliez and Lazzarato reclaim primitive accumulation to advance the analysis by not limiting it to a specific historical moment but rather, recognizing it as an ongoing process. It is worth quoting them at length: "It is therefore not surprising that the authors associated with research on the world-economy are completing and enriching analysis of the transformations of war and the ways it is waged in direct relationship with nascent capitalism and the colonies. And in fact, 'primitive accumulation' provides the crucible for all the functions that war would later develop: establishment of disciplinary apparatuses (dispositifs) of power, rationalization and acceleration of production, terrain for testing and perfecting new technologies, and biopolitical management of productive force itself. Most of all, war plays a leading role in the 'governmentality' of the multiplicity of modes of production, social formations, and apparatuses of power that coexist in capitalism at the global scale. It is not limited to being the continuation on the strategic level of the (foreign) policy of states. It contributes to producing and holding together the differentials that define the divisions of labor, sexes, and races without which capitalism could not feed on the inequalities it unleashes." (see, E. Alliez and M. Lazzarato, Wars and Capital, p. 76)

Thus, it’s war that is based on controlling populations. In specific circumstances, that is when it is applied to “troubled areas,” it is organized as low intensity war, warfare that is not about taking of territory but a complex strategy of military and paramilitary violence, targeted aid, and specific policing powers all designed to disrupt the cohesion of a community so that specific populations can be more easily controlled. It is the Fourth World War as the Zapatistas have warned us, but it's also the longstanding, ongoing war of racial capitalism. The argument made in theorizations of racial capitalism is that race is not simply surplus but constitutive. Racial animus, organized through various strategies of criminalization and dehumanization that make possible dispossession, displacement, and dislocation, escalates with capitalism's collapse. Racial capitalism, as many have come to believe about capitalism in general, is both a mode of production and a mode of destruction. Race and racial belonging become the markers to determine what bodies must be controlled and therefore can be produced as disposable. Our resistances are critical to decolonial practice. Aimed at the architecture of control that checkpoints and borders represent, these are at the same time resistances against dehumanization.

New projects and a vision for research moving forward that begin to articulate new theorizations about the current race situation must take seriously how combined research efforts can contribute significantly to the de-criminalization of our communities, especially confronting the socially, politically, and economically constructed disposability associated with black wage-less life, illegal immigrant labor, third world “narco-terrorists,” and Indigenous autonomous communities. It must also engage in the de-militarization of our communities by exposing how capitalist extractivist strategies advance practices and strategies of dispossessing by de-humanizing, displacing by criminalizing, and dislocating through policing, especially pre-emptive policing executed by combined forces of police, military, and increasingly state bureaucracies once designed to administer a social wage. Successful research can be mapped out in cartographies of struggle confronting the spread of low intensity war and its manifestation in various moments of state and state manufactured violences across communities. These maps can include a variety of systems of information generated from the local, situated, and poetic knowledges that can shift the dominant frames of an increasingly complex media landscape and tell a different story about social justice. Such an effort can, for example, map fierce care, a category of struggle, or convivial tool, that emerged out of and was articulated through the efforts of mothers who re-directed their grief and rage at the injustice dealt them and their family into strategic moments of care to consciously reclaim community spaces while also raising awareness about the specific injustice suffered by often targeted families and the community as a whole. The collective construction of convivial tools emerges organically and is articulated in performances and practices that address inequality, especially the violences produced as capitalism reaches its internal and external limits as a result of the exhaustion of “cheap nature,” contradictions of commodity fetishism, and the advances of grassroots struggle. It is therefore a research that must approach the topic genealogically, that is to say, by uncovering how our present has come to be defined by racial inequality and a persistent racial animus organized through successive modes of criminalization, including the epistemological dimensions of settler colonial dominance. That is to say we must map out how knowledge is produced in such a way as to legitimize the criminalization of certain groups, i.e. those targeted for “premature death.”

South Bay and North Bay crew

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

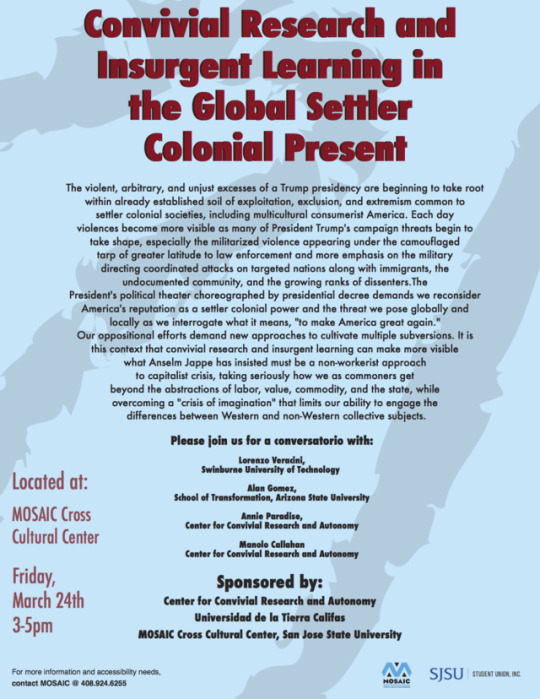

UT Califas demo ateneo, 3-24-18, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañeras/Compañerxs/ Insurgentas,

We will convene the Democracy Ateneo this coming Saturday on March 24 in San Jose at Casa de Vicky (792 E. Julian St., San Jose) from 2.00-5.00 p.m. to resume our scheduled reflection and action space and to explore some of the questions and struggles mentioned below and raised by the current conjuncture we find ourselves.

On March 8th -10th, Zapatista women from all five caracoles organized the “First International Political, Artistic, Sports and Cultural Gathering of Women that Struggle” in the caracol of Morelia, Chiapas in coordination with protests and manifestations of struggle that took place across the globe on International Women’s Day. A large banner at the entrance to the Morelia caracol welcomed all the women of the world. A smaller banner announced that men were prohibited. As the sun rose, a Zapatista band played Las Mañanitas, the song traditionally sung to celebrate a birthday, to welcome and celebrate the new beginning. Insurgenta Erika opened with a communiqué, welcoming all the sisters of Mexico and the world; the compañeras of the 6th National and International and of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the Indigenous Governing Council (CIG); the commandantas, insurgentas, and the compañeras from the militia, the bases of support, and the autonomous zones; they welcomed all those present and those not present, in struggle, both living and struggling elsewhere who could not come, and those dead. Insurgenta Erika made a point to offer a great embrace as wide as Mexico for the family of Eloisa Vega Castro, who traveled alongside Marichuy and was lost as a result of an accident on February 14th (see, "Palabras a Nombre de las Mujeres Zapatistas al Inicio del Primer Encuentro Internacional, Político, Artístico, Deportivo y Cultural de Mujeres que Luchan").

The opening communiqué read by Insurgenta Erika shared how the designation “insurgenta” is a strategy for when “we do not speak of an individual but of a collective." She identified herself as “Captain Insurgenta of Infantry, accompanied by other insurgents and militia companies of different degrees.” In an act of collective palabra (“our word is collective”) or sharing of the word, Insurgenta Erika laid out a history where the story-teller reflected on each stage of Zapatista women’s history through the rhetorical device of a vast and shifting “I” narrating a collective history: first she was a servant in the houses of others and she died of curable diseases, lack of medical attention, and lack of good food and education—where the doctors would not treat her because she was Indigenous and poor and did not speak Castilla. “But,” she reflected, “we also died for being women, and we died more.” During this time, she began leaving the house at night, to join the clandestine struggle forming in the jungle, telling no one, returning at dawn. The same collective narrator was born and grew up after the start of the war, listening to the soldiers, growing in resistance, leading and commanding battalions. She grew with her compañeras as together they raised schools, clinics, work collectives, and autonomous governments. But, she warned, “it cost a lot, and it still costs a lot.”

Insurgenta Erika also named how the idea for the women’s encuentro took shape in the space of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the Indigenous Governing Council (CIG), a space where Indigenous and Zapatista communities come together. The idea began to grow alongside the agreement to put forward Marichuy as spokesperson for the CIG and also as the strategy for her to be the first Indigenous woman candidate was put into action. The idea for the encuentro for women was organized from below—first in meetings and conversations among the collectives and in villages, then in the larger regions and zones, and finally in the caracoles. The idea came from the collectives, where the women shared how they discussed that “we have to do more because we see something that is happening. And what we see, sisters and compañeras, is that they are killing us. And that they kill us because we are women.”

In their analysis, it is the violence and death that is aimed at women through the patriarchal capitalist system that also contributes to a shared experience for women, which is also an experience that produces rage, courage, and struggle and while we are all different (like trees) this also makes us alike and collective (like a forest). “So we see the modern manifestation of this fucking capitalist system. We see that it makes a forest of women from all over the world with its violence. And its death has the face, body, and fucking head of patriarchy.” It is the system of patriarchial capitalism, in which women also participate, that must be destroyed, and no one will do it for us. We cannot demand that this system provide or make available our freedom; we must take responsibility to do it ourselves.

To this end, the opening communiqué offered two options: those gathered could compete with one another to be the most beautiful, the most radical, the most brilliant or most militant and so on, and from here, we could all go home with nothing. Or we could find each other outside the individuating and alienating technologies of subjectivization organized through abstraction and the spectacle, and we could listen and learn from each other. It is, as Anselm Jappe warns, that we must be vigilant of the narcissism that capitalism breeds in its final stages. (see A. Jappe, Writing on the Wall)

The communiqués circulated for this particular gathering include vital information and reflect a collective organization, a complex system of information. There were, for example, details on what to do in an emergency or if someone got sick. There was a recognition that everything would be managed by women, and reminders that the women responsible for the garbage and the toilets, various health and sanitation tasks, as well as the lighting and technology, the food preparation, were also all participants so we should all help take care. It was shared that the lessons and ideas would be transferred back to the villages for those who could not travel to the encuentro, those who stayed home to tend fields and families and other responsibilities. There was always an inclusion of those who could not be there physically; the collective extends beyond those immediately present.

A report from each caracol informed all of us on the condition of Indigenous women’s lives before the Zapatista uprising and the challenges they continue to confront in the present. By evening, a series of theatrical productions continued the spaces of insurgent learning and convivial research: the evening theater show opened with a play to demonstrate how the Zapatista women had organized themselves to prepare for the encuentro and to prepare to host so many guests (by some counts as many as 9,000 guests and 2,000 Zapatista women). The theatrical performance helped illustrate the process of asemblea and the manner in which cargos or community-determined obligations, and tequios, or shared work projects are named, authorized, distributed, and fulfilled; they demonstrated how they organized themselves collectively around work to receive women in struggle from all over the world. It is worth remembering that the Zapatistas have invited us to take seriously the distinction between labor, that is the abstract labor imposed by capitalism, and work, the organized tasks fundamental to community regeneration. It is not an easy distinction to learn and much harder one to claim as we disentangle ourselves from the imposition of capitalist discipline in every aspect of our everyday lives. One theatre piece from the caracol of Oventik had no dialogue and took place against the backdrop of the “Sound of Silence” played on pan flutes. The choreographed sequence bore witness to the violence, the beatings and insults, that Indigenous women faced before the uprising, and how they organized themselves collectively to confront violence as Zapatista women, showing how this was a central part of their struggle as the “Zapatista women that we are.” Another number highlighted the selling and beating of women before the Zapatista time, and another was set in Ciudad Juarez and exposed the violence that women face when they leave their families, communities, and their villages, leaving their children in trash heaps and being traded amongst men as commodities on la frontera where they are beaten, disappeared, murdered. (see, S. González Rodríguez, The Femicide Machine) In another, a colorful paper mountain burst open and Zapatistas poured out while dances welcomed all the women of the world. Later, Zapatista women groups from the caracoles, took the stage playing politically reworked corridos of Northern Mexico, including Dignidad y Resistencia from Oventik singing "Si no hay mujer, no hay revolución," (If there is no woman, there is no revolution) and "La Del Moño Colorado." Groups from Columbia and Argentina were invited to the stage as well and played late into the night to cries of Zapatista afuera! and Bella Ciao!

The days were filled with soccer/football matches; volleyball and basketball, between Zapatista teams and also Zapatistas and encuentro participants. Each field was taken seriously, with a Zapatista woman referee stationed throughout the day and actively officiating at matches. Workshops, performances, and skill shares jostled for space across the mesas or performance areas, as invited guests shared strategies from struggles against extractivism and development’s megaprojects; offered testimonio on gender and sexual violence; performed wailing recollections of genocide in Guatemala; sang and acted out skits about organizing against the hacienda system and colonial regimes; conducted medical training skill shares and convened drawing circles and many other things shared. There was Afro-Columbian guerrilla theatre and murals being painted everywhere, and everywhere there was dancing and chanting. Moments of critical self-reflection were built into the organization of the encuentro as well, as Zapatista women made available spaces for criticism—tables where ideas for improvement could be logged. Zapatista women and the consejas of the CNI moved in collectives across the hot open spaces, assembled themselves in disciplined formations and also in casual collective formations to listen, watch, participate.

At the same time that the encuentro began to unfold in the caracol of Morelia, Chiapas at the gateway to the Lacandon jungle, only an ocean away in Spain, women filled the streets by the millions, over six million it is reported, in a massive strike contesting the "alliance of patriarchy and capitalism" for International Women’s Day. All over the globe women mobilized to continue in greater force those mobilizations that have a long history as well as those that emerge in more recent formations. (see, Democracy Now, "In Spain, Women Launch Nationwide Feminist Strike Protesting 'Alliance of Patriarchy & Capitalism' ")

These spaces and actions are reflections of the violence and struggles in the current conjuncture. The violence ratchets up everywhere as capitalism implodes; it is unleashed with fury on the bodies of women. Our comrades from UniTierra Oaxaca pass on what the Indigenous of Southern Mexico forewarn: our last battle may be upon us. At the frontlines are women defending the land: territory and life. These are insurgencies driven by fierce care, a command of fear, and a refusal to abandon collective struggle (see, M. Callahan and A. Paradise, "Fierce Care: Politics of Care in the Zapatista Conjuncture". The encuentro emerges alongside the #MeToo moment, the #Timesup moment in the wake of Weinstein’s prolific violence. It occurs as prisoners refuse silence against violations endured in carceral regimes as they document and stand up to violent gendered attacks by correctional officers in prisons that Alan Mills calls "the worst distillations of toxic masculinty." (see V. Law, #MeToo Behind Bars; J. Wang, Carceral Capitalism) This includes the recently filed lawsuit by women and gender non-conforming plaintiffs housed and formerly housed at the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla. This moment also walks with Marichuy, as she exposes not only corruption, but the charade that is electoral “democracy” organized through the current nation state. It is reflected in the memory of Berta Cáceres of the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), her life and struggle kept alive in the banners and spaces of struggle of the Morelia encuentro as well. It lives in Standing Rock and Unist'ot'en and all the places where women organize to collectively defend and regenerate life.

“We don’t ask you to come fight for us, just like we won’t go fight for you. All that we ask is that you keep fighting, don’t surrender, don’t sell out, and don’t stop being women who struggle.” In the Zapatista women's closing communiqué, a letter was read aloud from Ayotzinapa: don’t leave us. The bad government wants to close the case and leave us in oblivion. A small candle was illuminated with the reminder: if you feel alone, afraid, or that the fight is hard, light it again in your heart and take it to the dams, the disappeared, the murdered, the violated, the exploited, the migrants, take it to the dead. And tell every one of them that you are going to continue the fight for truth and for justice. And then we can say to each other, “Bueno. Now we are going to begin to build the world we deserve and need.” (see, "Palabras de las Mujeres Zapatistas en la Clausura del Primer Encuentro Internacional, Político, Artístico, Deportivo y Cultural de Mujeres que Luchan").

In closing two proposals were put forward for agreement: that we organize ourselves collectively in our own worlds to study, analyze, discuss, and if we can, agree to name those responsible for the pains that we have. And second, that we meet again the next year to convene spaces for women in struggle, but in our own spaces, according to our own ways.

South Bay and North Bay crew

#UT Califas#Unitierra Califas#ateneo#Democracy Ateneo#Zapatista encuentro#women's encuentro#First International Political Artistic Sports and Cultural Gathering of Women that Struggle

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Unitierracalifas] UT Califas Fierce Care Ateneo, 7-22-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañerxs, The Universidad de la Tierra Califas' Fierce Care Ateneo will gather on Saturday, July 22, from 2.00 - 5.00 p.m. at Miss Ollie's / Swans Market (901 Washington Street, Oakland, a few blocks from the 12th Street BART station) to continue our regular, open reflection and action space to explore questions and struggles related to the emerging politics of fierce care as well as some of the questions below. Recently academics in service of the military industrial complex put forward a theory of military engagement that warns dominant military powers of the day, i.e. the U.S. and by extension Israel, to recognize that today's most profound military challenge emanates from "urbanization," that is the production of fragile and feral cities ("characterized by violence and disorder"). Not surprisingly, the cities that militaries must protect are the smart cities (with "technology fully integrated"), i.e. those cities like San Francisco, London, Barcelona, and Tel Aviv, that are organized around technologies and related services designed for the digerati and the lifestyle they enjoy. (see, Williams and Selle, "Military Contingencies in Megacities and Sub-Megacities.") It's hardly a new thesis much less a new concern or practice. Military might has been aware of the threats that enemies bunkered in cities pose and the difficulties inherent in urban warfare. For some time now Raul Zibechi has reminded us of how present day "superpowers" worry about the expanding urban periphery, the zones of non-being both on the edges of major metropolitan centers and in the periphery more generally. (see, Zibechi, "Subterranean echos: Resistance and politics 'desde el Sótano'") Locally, the increasingly visible militarization of urban police departments reflects a growing investment in low intensity war as a strategy to control urban populations. What we witness is more than simply an increase in the introduction of sophisticated new armaments filtered back into police departments from the military. As families with deep roots in Oakland, for example, are displaced to outlying zones such as Vallejo and Stockton, paramilitary-like formations and strategies ratchet up violence that targets specific individuals, invades homes, and disrupts family relations. More and more state violence strikes in broad daylight as young people are gunned down walking to the store or chased off roads by multi-agency task forces, as in the cases of Colby Friday (8-12-2016) and James Rivera Jr. (7-22-2010). What is worthy of note in this new global formulation of "contemporary Stalingrads" is the tacit recognition of the amount of inequality and the intensity of its production in the current capitalist conjuncture. In other words, elites and the military ranks in their service recognize how capitalism is producing an increasingly "dangerous" population behind growing numbers of "sheet-metal forests." (see, Williams and Selle, "Military Contingencies in Megacities and Sub-Megacities.") Indeed, this becomes a moment in the articulation of a new racial spatial regime. In this context, it is worth noting the recent arms deals of the Trump administration with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Taiwan. Worth billions, these weapons are largely manufactured in the U.S. and are backed by what Robert Kurz reminds us is military bullion, from the gold dollar to the arms dollar. According to Kurz, "the dollar maintained its function as world currency through the mutation from the gold dollar to the arms dollar. And the strategic nature of global wars in the 1990s and turn of the century in the Middle East (in the Balkans and in Afghanistan) was directed at preserving the myth of the safe haven via the demonstration of the ability to intervene militarily on a global scale, thereby also securing the dollar as world currency." (see, R. Kurz, "World Power and World Money: The Economic Function of the U.S. Military Machine within Global Capitalism and the Background of the New Financial Crisis") Much more needs to be said about the military strategy currently being developed in response to the production of mega-cities and sub mega-cities, i.e. urbanization. Read genealogically, the present focus on urbanization presents as simply another justification for a greater commitment to invest in counter insurgency strategies and low intensity conflict against civilian populations in regions of the world that still have strategic interests for the U.S. More to the point, these strategies and investments in social control economies are increasingly directed at historically under-represented populations in the U.S. Against this onslaught, it is the practices of care, the nurturing that makes survival possible, that poses the greatest threat by communities sheltering in "sheet-metal forests" or even those sub-terranean networks of care that are almost entirely invisible in the "concrete canyons" of smart cities. If the rebel army has always relied on care and strong bonds with the community to survive, perhaps it is these networks that define the resistance in the present moment, more than ideology and identification, flags and formations. Strategies of capitalism designed to dismantle systems, networks, and practices of care work in tandem with militarization organized as counterinsurgency against a local population. Precarias a la Deriva alert us that women in Madrid's urban periphery have been creatively responding to the system's efforts to dismantle care. They warn that precarity results from four trajectories: the dismantling of of the Welfare State towards a shift to strategies of "containment of subjects of risk;" the dismantling of community spaces and expansion of commercial spaces, paralleled by the "hegemony of the car;" the dismantling of systems and skills to grow and share food, produce clothing and other necessities, a process that works hand in hand with the rise of fast food and prepared food; and the invasion aimed at time, resources, recognition, and desire for caring for children, elderly, and infirmed. (see, Precarias a la Deriva, "A Very Careful Strike-Four Hypotheses") Thus, precarity, as a current strategy of capitalism is often designated, results when areas of care in our everyday lives are privatized and no longer in our collective control. But despite this reality, people, especially women, refuse to abandon the obligations of care. Not only are we able to recognize and remain committed to care; we find at times it can be fierce. What distinguishes care —that is the everyday efforts to nurture and be nurtured by the people around us— with other practices we are beginning to come to understand as fierce care? We refuse to abandon what we generally think of care. We expect people to be thoughtful, to worry about each other, to find ways to support, nurture, and heal those around us. But, more than that there is a growing awareness of the necessity to directly confront forces and systems of violence that intentionally target specific folks, disrupt the community, dismantle the social infrastructure, and unweave the social fabric. In Stockton, mothers whose grown children have been killed by the state weave a complex fabric of refusal and care. Immediately following the killing of Colby Friday last August by Stockton Police officer David Wells, Dionne Smith, the mother of James Rivera Jr. who had been killed by Stockton Police six years earlier, went to the spot where Colby had been killed, and with others refused to leave —watching over the spot for two weeks and protecting the community memorial until Colby’s body was in the ground. Colby’s mother, Denise Friday, who lives two hours away in Hayward, also returns to the spot regularly, to sit and engage neighbors, refusing erasure and the fear that comes when police attempt to impose narratives and silence. These acts of vigil rest beneath the community gatherings and speak outs where mothers gather to seek and define justice; they are the quiet beneath the protests and the arrests. When school let out across California in early June and the distribution of school lunches was discontinued for summer, these same mothers began gathering once a week making dozens and dozens of brown bag lunches and handing them out to local children to help bridge the hunger of children in summer when the schools shut down. When there was extra lunches, they distributed them to the houseless community gathered under the highway overpass, or in one instance to people displaced from their apartments by fire earlier that day. As August and the one year anniversary of the killing of Colby Friday approaches, these mothers are raising funds for a back-to-school backpack drive (Colby Friday - Backpack Drive). Colby’s school age daughters dreamed the project together: the August prior, their father had been killed just before they all had a chance to get their back-to-school supplies together. In response a year later, their act of organizing supplies both exposes and remembers the stolen life of Colby, and reaches out to other children and families to share supplies. These interconnected acts mark a commitment to confront forces of violence to protect family and community and at the same time create space for everyday care. These are the moments where the care is fierce.

We retell this story and we are reminded of another story from Oaxaca —in Oaxaca, comrades tell us, when we hear bullets being fired, we don’t run away, we run to the sound of the bullets to find each other and together discover a way to stop them. As our comrades in Uni Tierra Oaxaca recently reflected: we must come together and listen, recognizing that we must learn from each other as an act of sharing and care —rather than one seeking to crush the other. This too is a fierce care.

South and North Bay Crew

NB: If you are not already signed-up and would like to stay connected with the emerging Universidad de la Tierra Califas community please feel free to subscribe to the Universidad de la Tierra Califas listserve at the following url <https://lists.resist.ca/cgibi n/mailman/listinfo/unitierraca lifas>. Also, if you would like to review previous ateneo announcements and summaries please check out UT Califas web page. Additional information on the ateneo in general can be found at: <http://ccra.mitotedigital.org /ateneo>. Find us on tumblr at <https://uni-tierra-califas.tu mblr.com>. Also follow us on twitter: @UTCalifas. Please note we will be shifting our schedule so that the Democracy Ateneo (San Jose) will convene on the fourth Saturday of every even month. The opposite, or odd month, will be reserved for the Fierce Care Ateneo (Oakland). In this way, we are making every effort to maintain an open, consistent space of insurgent learning and convivial research that covers both sides of the Bay.

1 note

·

View note

Text

UT Califas demo ateneo, 6-24-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Comrades:

We will convene the Democracy Ateneo this coming Saturday on June 24 in San Jose at Casa de Vicky (792 E. Julian St., San Jose) from 2.00-5.00 p.m. to resume our scheduled reflection and action space and to explore some of the questions and struggles mentioned below and raised by the current conjuncture we find ourselves.

Recent statements warn that Trump's presidency, or more accurately, his non-stop bluster and blunders, are likely to destabilize key regions of strategic interest to the U.S. There are two underlying assumptions in this notion that should give one pause. First, much of the U.S. mainstream media and political punditocracy privilege specific "theaters" of war such as the Middle East and Eastern Europe, marginalizing by default other regions, notably, Latin America and other spaces across the Global South. Second, and probably most importantly, the threat of war discourse tied to regions that hold strategic interest for the U.S. suggests that war is not or has not already been underway. Our attention is focused on what we are told are legitimate or necessary wars. In essence, there are recent or current wars in specific countries, Syria and Afghanistan for example, that are rendered highly visible but there is, as Bob Marley once sang, "war everywhere war." Military analysts identify at least two kinds of wars in the present. There are the more traditional wars we have grown accustomed to marked by bombing campaigns, highly visible military operations, the architecture of bases and convoys, and so on. And then there are the less traditional —wars that are other than war, what military elites name as "unconventional wars." This type of warfare is not necessarily new, but it has taken on an increasing importance during what Robert Kurz calls the U.S.'s "economic militarization." (see, R. Kurz, "World Power and World Money: The Economic Function of the U.S. Military Machine within Global Capitalism and the Background of the new Financial Crisis.") The unconventional wars are not focused on a specific battlefield or tied to particular region and, as a consequence, not completely about conquering territory. This is low intensity war and it is war other than war. It is a type of warfare less invested in pitched battles and more occupied with controlling whole populations, even groups that might be scattered across a region or concentrated in the margins, but fundamentally pose a threat precisely because they are not typical combatants. In fact, the U.S. military imagines one of its greatest threats to be those "zones of non-being." (see, R. Zibechi, "The Militarization of the World's Urban Peripheries") The production of refugees across the planet are emblematic of the confluence of these multiple wars. "War, rumors of war." For the U.S. military, the solution to the threats it believes are arrayed against it is full spectrum dominance across the globe. (see, Joint Vision 2020) Much can be said about how such an approach is in the service and at the same time one of the primary engines of this later stage of neoliberalism. Kurz's genealogy of the enduring position of the dollar as world currency through its "mutation from the arms dollar to the gold dollar" is worth quoting at length: "The United States’ astronomical debt arising from this process of economic militarization could already in the 1980s no longer be funded from its own savings. But the economic power of the military machine was also reflected in foreign affairs. It was the military power of the United States as world police that offered global financial markets a safe haven —or so it seemed. This impression was reinforced significantly by the perceived victory over the opposing Eastern (European) system. The dollar maintained its function as world currency through the mutation from the gold dollar to the arms dollar. And the strategic nature of global wars in the 1990s and turn of the century in the Middle East (in the Balkans and in Afghanistan) was directed at preserving the myth of the safe haven via the demonstration of the ability to intervene militarily on a global scale, thereby also securing the dollar as world currency. On this ultimately irrational basis, excess (that is, not profitable and investable) capital from the third industrial revolution from around the world flowed increasingly into the United States, thus indirectly financing the defense and military machine." (see, R. Kurz, "World Power and World Money," pp. 192-193.) In Kurz's analysis, the rise of the U.S. military machine and its global intervention from the 90s onward served to funnel excess capital back into its own maw. The particulars of the circuits could be traced following this analysis. A focus on the interlocking technologies of full spectrum dominance and the ambitions of U.S. military industrial complex minions make apparent what is often masked: the omnipresence of war. Here we do not just mean traditional or non-traditional war, but counterinsurgency that is ultimately "class" warfare. While this may no longer be the traditional antagonistic, agonistic classes, as Kurz, John Holloway, and others remind us, it is nonetheless still the kind of class warfare that Karl Marx invited us to analyze and to contest. Foucault may have said it best, "it is one of the essential traits of Western societies that the force relationships which for a long time had found expression in war, in every form of warfare, gradually became invested in the order of political power." (see, M. Foucault, History of Sexuality, v. 1, 1990) There really is no special category for war despite the efforts of military intellectuals and politicians to insist on a specific taxonomy of warfare cloaked in national interests. Thus, we forget that war is persistent, always with us as a fundamental element of the production of the class relation. (That its omnipresence is in some cases easily forgotten is no accident.) War does not appear as as an essential element in the production of this class relation for the simple reason that it has been, as Achille Mbembe informs us, domesticated (see, A. Mbembe, "Necropolitics"). War and warfare in the Western European imaginary has been forged into categories that exalt good wars as opposed to bad, or illegitimate wars versus legitimate ones. The result of this epistemological shift, according to Mbembe, is to construct an apparatus that masks the slavery and colonialism that propelled the West into global dominance and defines it to this day. The nation state and capitalism have been imbricated in geographies of racial violence and colonial dominance from the 16th century to the present. "Everywhere war." The U.S. continues as the principal benefactor of warfare. In fact, the U.S. unabashedly insists that it alone has inherited the mantle to designate what is legitimate and illegitimate in warfare. Such arrogance knows no limits. It reaches its most grotesque level when the U.S. blusters about being the ultimate, final human rights arbiter across the globe. But, at the end of the day the U.S. is committed to repression which, Kristian Williams reminds us, is part of "the normal operations of the liberal state." Counterinsurgency is, pace Williams, a new type of warfare and style of war designed to eliminate or contain any project that threatens the dominant system. (see, K. Williams, "The Other Side of the COIN: Counterinsurgency and Community Policing.") The cloak of domesticated warfare organized through national interests, of which the U.S. has through much of the 20c claimed to be at the center, manages class warfare at home and abroad. War in the national interest has been one of the key devices that W.E.B Du Bois warned has made it possible for the white working class to claim and exploit a shared class interest and racial privilege against enslaved Africans and despoiled Native Americans as well as others who have been victims of U.S. colonial expansion. This is democratic despotism, that is, the idea that American democracy has been organized through a series of "black codes" that criminalize marginal populations within and beyond the territory of the U.S. to justify their dispossession of them and their commons in order that they can be exploited while privileging the white working class. According to Du Bois, the maintenance of an herrenvolk democracy as a strategy of class warfare that only serves a few requires expansion, acquisition of ever more resources and wealth to maintain the elevated lifestyle of those select few designated to enjoy the fruits of racial capitalism. (see, W.E.B Du Bois, "African Roots of War") "Until the philosophy which holds one race /superior and another inferior /is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned /everywhere is war, me say war." The Fourth World War, the designation the Zapatistas use to explain the current state of an omnipresent, ubiquitous warfare that impacts everyone on an everyday basis, does not always have a visible enemy or select strategic targets to be overrun. It is a war that is organized in the interstices of abstraction and extraction. It is a war battled out daily in the formation of a social relation that at times does not appear so visible, or as an obvious site of violent conflict. But, it is everywhere around us. It is a war often carried out by either the military or the police or both. It surfaces when a black or brown body is so devalued that it is gunned down without pretext except for fear of the other or reckless disregard, the result of a system that allocates "premature death" for one group against another, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore laments. (see, R.W. Gilmore, "Race and Globalization.") Similarly, we often overlook the impact our lifestyle decisions have on other regions of the world, usually oblivious to the hidden costs for the maintenance of our pristine digitized urban landscapes. The decisions we make about our lifestyle for the most part can have devastating, life or death consequences. But, how to break a social relation and refuse to be complicit in a war that is not of our making? On May 28 the EZLN and National Indigenous Congress (CNI) convened the "Constitutive Assembly for the Indigenous Governing Council (CIG)" made up of some 1,482 participants representing over 52 peoples to officially select María de Jesús Patricio (also known affectionately as "Marichuy") as spokesperson who will "participate as an independent candidate to the presidency of the Republic in 2018." (see, M. Gómez "Indigenous Governing Council") The success of the CGI and its naming of Marichuy as CGI spokesperson and candidate is part of the CNI and the EZLN's ongoing effort to disrupt the Fourth World War. The CNI and the Zapatistas have conspired to organize from below and to the left putting forward an Indigenous woman "whose name we will seek to place on the electoral ballot for the Mexican presidency in 2018 and who will be the carrier of the word of the peoples who make up the CIG, which in turn is highly representative of the Indigenous geography of our country." (see, EZLN & CNI, "The Time Has Come") The Constitutive Assembly and the momentous selection of its spokesperson continues the CIG's fulfillment of the CNI-Zapatista intervention in the election spectacle and might be viewed as torreando with the dominant political system and mainstream media. Not torreando in a frivolous way, nor in a way to compete or to take over the system, but in a clever way intended to expose the limits of the spectacle including the system overall and the failure of key institutions. It is a maneuver "to crash the party of those above which is based on our death and make it our own, based on dignity, organization, and the construction of a new country and a new world." The CNI-Zapatista initiative gestures to a critical political innovation in the formation of the governing council and the permanent assembly across Mexico that sustains it, a critical success in organizing the majority of Mexico from below and to the left. More to the point, it makes more visible the struggle for an alternative to the corrupt political system and its maintenance of war, revealing the devastating impact the war has had on Mexico from below. "This is the destruction that we have not only denounced but confronted for the past 20 years and which in a large part of the country is evolving into open war carried out by criminal corporations which act in shameless complicity with all branches of the bad government and with all of the political parties and institutions. Together they constitute the power of above and provoke revulsion in millions of Mexicans in the countryside and the city." (see, EZLN & CNI, "The Time Has Come")

"Now is the time," as the Zapatistas have said on other critical occasions, "to sharpen hope." But, this new weapon, a weapon of hope forged through the shared efforts of the CNI and the Zapatistas is not a conventional arm. It is a convivial tool. It is a device co-generated in struggle by a community long victimized, and targeted, in the warfare of over five hundred years of slavery and colonialism, and most recently, neoliberalism. As a convivial tool it is forged horizontally with the equal participation of all that brings to bear the wisdom common to all convivial apparatuses —that the new tool celebrates all who helped forged it without in any way diminishing any one in its construction or application. "What we've seen on our limited and archaic horizon," explains SupGaleano, "is that the collective can bring to the forefront the best of each individuality." (see, SupGaleano, "Lessons on Geography and Globalized Calendars," April 2017) And, it is a tool, or weapon, that can be wielded by anyone and everyone because its only purpose is the regeneration of the community. It is worth quoting the CNI-EZLN statement from the CIG convening at length: "We reiterate that only through resistance and rebellion have we found possible paths by which we can continue to live and through which we find not only a way to survive the war of money against humanity and against our Mother Earth, but also the path to our rebirth along with that of every seed we sow and every dream and every hope that now materializes across large regions in autonomous forms of security, communication, and self-government for the protection and defense of our territories. In this regard there is no other path than the one walked below. Above we have no path; that path is theirs and we are mere obstacles." (see, EZLN & CNI, "The Time Has Come") The CIG's purpose and their selection of Marichuy is the articulation of a powerful tool forged through centuries of struggle but most recently, at least since 1994, decades of convivial research and insurgent learning. In the closing of the Zapatista hosted seminar, "The Walls of Capital, The Cracks of the Left," Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés states it plainly: "that’s what the National Indigenous Congress’s effort is about, and that is why the candidate and the Indigenous Governing Council will make a tour. It’s not to win votes; we already know that there will be few votes and that they’ll still defraud us out of those few votes, and that the bad system will revive the dead to vote in its favor. Enough of that already!" (see, Closing Words of the Seminar “The Walls of Capital, The Cracks of the Left,” April 2017) South Bay Bay Crew NB: If you are not already signed-up and would like to stay connected with the emerging Universidad de la Tierra Califas community please feel free to subscribe to the Universidad de la Tierra Califas listserve at the following url <https://lists.resist.ca/cgibn /mailman/listinfo/unitierracal ifas>. Also, if you would like to review previous ateneo announcements and summaries please check out UT Califas web page. Additional information on the ateneo in general can be found at <http://ccra.mitotedigital.org /ateneo>. Find us on tumblr at <http://uni-tierra-califas.tum blr.com> and twitter @UTCalifas. Please note we have altered the schedule of the Democracy Ateneo so that it falls on the fourth Saturday of every even month from 2.00 to 5.00 p.m.

#UniTierra Califas#UT Califas#Universidad de la Tierra Califas#Democracy Ateneo#San Jose#EZLN#Marichuy#war#COIN#achille mbembe#CNI#Zapatista

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

UT Califas demo ateneo, 4-22-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Comrades: We will convene the Democracy Ateneo this coming Saturday on April 22 in San Jose at Casa de Vicky (792 E. Julian St., San Jose) from 2.00-5.00 p.m. to resume our scheduled reflection and action space and to explore some of the questions and struggles mentioned below and raised by the current conjuncture we find ourselves.

The conceits of Western Democracies are everywhere exposed. From Donald Trump's electoral "victory," to the current election battle underway in France and the most recent political drama unfolding in Turkey, the claims developed nations make about democracy ring hollow —a political din produced by the rattling taking place in their own echo chambers. Still, power is believed to be in the hands of the "informed citizen." But, that power, the power of the vote in a formal, representative democracy, in reality can do little. Can any group of organized voters stop the U.S. military industrial complex from expanding, from using its massive arsenal on countries already ravaged by wars, from keeping the entire globe on a constant war footing? In fact, as the EZLN has named early on, this is the Fourth World War. It is everywhere at once. And in many places it is carried out in the name of democracy.

The mendacity that pervades democratic systems is no where laid more bare than when the world discovers that the state of one of the most powerful Western Democracies targets a family, a family guilty of nothing more than being ethnic Mexican and refusing to recognize the artificial borders that divide the continent. In this particular instance, a mother has turned a Denver church into a sanctuary for her and her children to be together and to be safe. She is determined to prevent the state from using her and others like her to send a message, instilling fear in the the over eleven million Spanish-speaking members of the U.S. economy who, although undocumented, are vital to its operation. When the state, according to Anselm Jappe, no longer serves capital it necessarily falls back on its primary purview, namely repression. "In times of crisis the State transforms itself into what it has historically been since its beginning: an armed gang." (see, A. Jappe, "Violence, What Use is It") Whose interest does it really serve to hunt down a mother and terrorize her brood, forcing them to flee, hide, and finally, fight back. Although many families have gone underground, a few like Jeanette Vizguerra have organized themselves through their networks to oppose any efforts to remove them from the country and to break up their families. (see, Democracy Now, "'I Am Her Voice': Meet the 10-Year-Old Boy Helping His Mom Take Refuge from Deportation in a Church") These families are connected to the families trying to find stable land as they flee Syria, Eritrea, Somalia, Côte d'Ivoire, Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan... Not long ago Douglas Lummis alerted us about the inherent limits of political systems that claim to be "democracies." Lummis' critique of democracy also reclaims it —what democracy really means, an unencumbered authentic democracy that is the expression of people's power. However, he also warns us that any reclaiming of democracy must not wait for it. In other words, democracy, or radical democracy, does not require political education or revolution, that is a vanguard or leaders to direct the people. It only needs to be exercised —taken up by everyone in any given moment in the situation they find themselves locally. However, "any democratic movement that accepts the basic conditions of competition and work in the capitalist economy as unalterable, and seeks only to make things 'a bit more pleasant,' has conceded defeat from the beginning." (see, D. Lummis, Radical Democracy)

Lummis' criticism remains potent and his admonishment necessary: Western Democracies and their ilk are indeed corrupted and have little to do with people power. Yet he overlooks a critical fact: these democracies are better understood as racial democracies. The entanglement of democracy and capital has hardly been by accident and in every way from their beginnings were dependent on the principal institutions of racial inequality, namely colonialism and slavery and, much later, apartheid. The braiding of capital and "democracy" within colonial and settler colonial societies can be mapped, for example, in the legislative acts, or Black Codes, that dehumanized Africans and later their descendants converting them into property and ultimately denying them any rights as workers, citizens, and so on. (see, A. Mbembe, The Critique of Black Reason) These Black Codes were also forged with every intention to control the Indigenous populations of the Americas, first as labor and later to be attacked and confined to reservations so that the land and resources beneath them was accessible for extractivist design. The union between capital and democracy extends in the U.S. to the ethnic Mexican population after the U.S.-Mexican War (War of American Aggression) resulted in the U.S. absconding with a third of Mexico's patrimony. The longstanding legislative enactments that codified racial and gender difference when the Spanish, and later English and French, arrived to the New World to the present are only part of the story. In the current context, it is no secret that this conjuncture has made more visible capitalism's production of a disposable subject. But, not all subjects are disposable in this final phase of capitalism. It might be more accurate to assert that there are at least two kinds of subjects in the current moment: disposable and digitized. By digitized we mean a body that is totally plugged into a digital biotech world, the 2.0 world of debt, finance, and apps that colonize all aspects of our everyday lives, increasingly drawn to high tech cultural playgrounds like San Francisco, Barcelona, and Tel Aviv. (see, P. Gelderloos, "Precarity in Paradise: The Barcelona Model")

It should be of little surprise to practically no one that, as the Black Panthers used to say back in the day and Robin Spencer reminds us today, the avaricious businessman, demagogic politician, and racist violent cop are together the core of a fascist state. (see, Spencer, "The Black Panther Party and Black Anti-Fascism in the United States") It is no wonder that the kabuki theater of American politics unfolds with everyone playing their part, including a newly empowered fascist network of white supremacists and their ilk insisting on their right to exercise free speech as in the recent "Trump rally" convened by Gavin McInnes of Vice magazine and other fascist groups in Berkeley. (see, Democracy Now, "White Nationalists, Neo-Nazis & Right-Wing Militia Members Clash with Antifa Protesters in Berkeley;" S. Bauer, "I Went Behind the Front Lines With the Far-Right Agitators Who Invaded Berkeley")

An authentic crisis is one, Ivan Illich insists, "that is, the occasion for a choice —only if at the moment it strikes the necessary social demands can [it] be effectively expressed." However, in engaging the crisis that is essentially already upon us, "if we are to anticipate its effects, we must investigate how sudden change can bring about the emergence into power of previously submerged groups." "It is not calamity as such," explains Illich, "that creates these groups; it is much less calamity that brings about their emergence; but calamity weakens the prevailing powers which have excluded the submerged from participation in the social process." Who are these "submerged groups" that are increasingly more visible in the current moment? They are communities of struggle who are not consumed by "political myths" and who are not duped by "the current industrial illusion." They are everyday people that claim the vernacular and are prepared to transform the crisis or calamity or catastrophe into a moment to exercise a convivial alternative. They, we, are folks committed to a "conscious use of disciplined procedure that recognizes the legitimacy of conflicting interests, the historical precedent out of which the conflict arose, and the necessity of abiding by the decision of peers." "The preparation of such groups," declares Illich, "is the key task of new politics at the present moment." (see, I. Illich, Tools for Conviviality, pp. 105-106.) Illich's counterfoil research, or what those of us who are apart of Universidad de la Tierra Califas call convivial research and insurgent learning, seeks to recognize each other across submerged groups; activate submerged groups where they have become somewhat dormant; and link with those that have begun to surface. Among these activated networks that are more than networks, some of the most resilient fibers are those connected to and emanating from the EZLN and the growing Zapatista community that surrounds them. This week ends the Zapatistas' most recent initiative, a global campaign titled Faced with the Walls of Capital: Resistance, Solidarity, and Support for Below and to the Left. With this as with previous spaces, the Zapatistas continue to accumulate struggle, creating the opportunity for communities of struggle to converge while learning from one another how to advance a multifaceted effort of resistance against capitalism and at the same moment to continue to collectively construct alternatives. Migrants on the move defying borders are one of those submerged groups as are the mothers and their families who work to dismantle police violence. It includes all the pirates of the quilombos of the peripheries and the pirates who risk the undercommons appropriating resources, subverting practices, and dismantling the structures of dominant institutions. All those who attempt to live unmediated lives by the forces of the state and capital, but also by the abstractions that organize and sustain capitalism as a system.

Jappe warns that capitalism is not in one of what has been a long line of cyclical crises, but rather what we are experiencing is a definitive crisis brought on by capitalism's fundamental, internal contradiction —it is no longer able to produce surplus value through the exploitation of labor. If capital is in its final death throe then how do we extricate ourselves from abstract labor and the commodity form both of which are key mechanisms and conditions of capitalist command, whether it be articulated through labor, commodity, or more recently in the neoliberal era through debt. How do we get beyond the violent excess of class struggle? How do we do we grow into something else, that outgrows race and patriarchy until they whither away? "One cannot escape from the structural constraints of the system by democratizing access to its functions," explains Jappe. (see, A. Jappe, "Credit unto Death") "In the new theory of commodity fetishism... the crux of the problem resides in the 'subject-form' common to all those who live in commodity society, although this does not mean that this form is the same for all subjects." According to Jappe, "the subject is the substrate, the agent, the bearer that the fetishistic system of valorization of value requires in order to assure production and consumption." (see, A. Jappe, "Princesse de Cleves Today") What news ways of being human can we imagine and become together?

South Bay Bay Crew NB: If you are not already signed-up and would like to stay connected with the emerging Universidad de la Tierra Califas community please feel free to subscribe to the Universidad de la Tierra Califas listserve at the following url <https://lists.resist.ca/cgibn /mailman/listinfo/unitierracal ifas>. Also, if you would like to review previous ateneo announcements and summaries please check out UT Califas web page. Additional information on the ateneo in general can be found at <http://ccra.mitotedigital.org /ateneo>. Find us on tumblr at <http://uni-tierra-califas.tum blr.com> and twitter @UTCalifas. Please note we have altered the schedule of the Democracy Ateneo so that it falls on the fourth Saturday of every even month from 2.00 to 5.00 p.m. -- Center for Convivial Research and Autonomy

http://ggg.vostan.net/ccra/#1_______________________________________________ UnitierraCalifas [email protected]

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Unitierracalifas] UT Califas fierce care ateneo, 3-25-17, 2.00-5.00 p.m.

Compañerxs,

The Universidad de la Tierra Califas' Fierce Care Ateneo will gather on Saturday, March 25, from 2.00 - 5.00 p.m. at Miss Ollie's / Swans Market (901 Washington Street, Oakland, a few blocks from the 12th Street BART station) to continue our regular, open reflection and action space to explore questions and struggles related to the emerging politics of fierce care as well as some of the questions below.

Friday, March 10 ended Native Nations Rise, a four day convergence of Indigenous peoples and allies who gathered in Washington D.C. to continue the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline as well as the several other pipelines under construction, including the Keystone XL, Trans-Pecos, Bayou Ridge, and Dakota Access. The fight, according to Kandi Mossett, is more than against one pipeline, it's about embracing a whole new way of life —one that is sustainable and is not about taking from the earth, but giving back. It is an on-going struggle. For Mossett and others it is the continuation of a five hundred year struggle against forces that take and destroy for a lifestyle that is no longer tenable. The four days of mobilization in D.C. not only confronted the destruction of shale deposits and the pipelines that the oil industry wants to use to maintain a toxic lifestyle, but also advanced a recognition that we must reclaim and invent a new, sustainable way of living. (see, Jaffe, "Next Steps in the Battle Against the Dakota Access and Keystone Pipelines")

More and more we are reminded that Indigenous communities are on the front lines of struggle. They are often the first line of defense against the rapacious and destructive extractive industries. It is this battle line that also signals that the U.S. is a settler colonial nation and as such has been and remains committed to erasing Indigenous people. The most recent persecution against the Standing Rock Sioux and others at the DAPL has made sacred site water protectors into targets of the most advanced militarized police repression, deploying sophisticated weaponry, infiltration, and surveillance while also criminalizing sacred-site water protectors in the mainstream media. The assault on Indigenous nations underscores the most critical element of settler colonialism, that is, according to Patrick Wolfe, it is "a structure, not an event." (see, Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native") J. Kehaulani Kauanui takes up Wolfe's argument to point to an "enduring indigeneity" that operates dialectically as Indigenous peoples resist all elimination efforts, and at the same time as the settler colonial structure continues into the present to "hold out" against indigeneity. (See, J. Kehaulani Kauanui, "A Structure, Not an Event.") For both Wolfe and Kauanui, Palestine is the most recent site of a violent settler colonialism advanced by a U.S. backed Zionism. To this we would add Indian-occupied Kashmir, of which Omar Bashir recently noted, "India only wants Kashmir, not its people," thus naming the settler colonial logic with its concomitant operations of elimination and containment. (see, Bashir, "India Only Wants Kashmir, Not Its People")

More recently, Lorenzo Veracini has taken up Wolfe's intervention and also asserted that both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous are now being treated roughly the same —that is as disposable people. "The working poor are growing in number almost everywhere," warns Veracini. "Like Indigenous peoples facing a settler colonial onslaught, the 'expelled' are marked as worthless. The 'systemic transformation' produces modalities of domination that look like setter colonialism." In other words, more and more people are treated as disposable and the system would prefer to eliminate them rather than convert them into exploitable labor. (see, Veracini, "Settler Colonialism's Return")

From the Zapatistas to the several battle lines against pipelines across the U.S. and other battle fronts occupied by Indigenous communities across the globe, they are at the fore front of disrupting capitalism. But, it's not the capital(ism) we originally battled against. Or, at least, our understanding of capitalism has shifted, because capitalism has reached its final crisis. There are two clear areas of analysis that more recently have exposed its limits. First, capitalism no longer has access to an inexhaustible or "cheap nature." According to Jason Moore "capitalism is historically coherent —if 'vast but weak'— from the long sixteenth century; co-produced by a 'law of value' that is a 'law' of Cheap Nature. At the core of this law is the ongoing, radically expansive, and relentlessly innovative quest to turn work/energy of the biosphere into capital (value-in-motion)." (Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life, p. 14)

Robert Kurz, and the wertkritik school that has been built around his work, is the second line of thought that recognizes capitalism is not just in yet another cyclical crisis but is nearing the limits of its internal contradiction. Kurz has taken to task the different approaches to Marx for their inability to extend Marx's critique of political economy and account for both the excesses and limits of commodity society. "Kurz, on the basis of a thoroughgoing reading of Marx," asserts Anselm Jappe, "maintained that the basic categories of the capitalist mode of production are currently losing their dynamism and have reached their 'historical limit': mankind no longer produces enough 'value.'" (see, Jappe, "Kurz: A Journey into Capitalism's Heart of Darkness," p. 397) The crucial point made by Kurz and elaborated by Jappe is that capitalism is not eternal, nor are the specific elements of capitalism, i.e., abstract labor, value, commodity, and money, timeless. "The structural mass of unemployment (other typical phenomena are dumping-wages, social welfare, people living in dumps, and related forms of destitution) indicates that the compensating historical expansionary movement of capital has come to a standstill." (see, Kurz, "Against Labour, Against Capital: Marx 2000") Kurz admonishes against mis-using Marx's categories and falling into a positivistic trap. A more complete reading and extension of Marx's insights reveal that commodity, value, and labor are not ontological, "transhistorical conditions of human existence." As much as they are neither eternal or timeless, they likewise have a history. "The appearance of labor as the substance of value is real and objective, but it is real and objective only within the modern commodity-producing system." Jappe explains,"Kurz always asserted that capitalism was disappearing along with its old adversaries, notably the workers' movement and its intellectuals who completely internalised labour and value and never looked beyond the 'integration' of workers —followed by other 'lesser' groups— into commodity society,"

Both Moore and Kurz invite us to interrogate the myth of capitalism as a never-ending system and to recognize that it has reached its limit. It can not overcome its internal contradictions given that it can no longer exploit cheap nature. But, if capitalism is gasping its last what does this mean for race and racial formations that were long believed to be essential to managing capitalism's most exploitative functions, i.e. producing surplus value via tightly controlled labor made more malleable through a brutal racial hierarchy of violent control? Does the end of capitalism signal an abandonment of the several intersecting racial regimes that helped insure its reproduction? "Race," Wolfe insists, "is colonialism speaking, in idioms whose diversity reflects the variety of unequal relationships into which Europeans have co-opted conquered populations." For Wolfe,"different racialising practices seek to maintain population-specific modes of colonial domination through time," (see, Wolfe, "Introduction," Traces of History, p. 5; 10) If settler colonialism endures as a structure that attempts to produce populations as disposable, how are we to understand this in relation to labor and race in the current moment?

Is disposability a condition of capital in its final stage or a new racial regime? "Disposability manifests," Martha Biondi reminds us, "in our larger society's apparent acceptance of high rates of premature death of young African Americans and Latinos." It is not only the school to prison pipeline, structural unemployment, and "high rates of shooting deaths" that produce disposability. (quoted in Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #Blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation, p. 16) It is also the way we think about water, health, and collective ways of being.

Indigenous struggles and the Black and Brown working class are and have been refusing disposability. This can be heard in the adamant battle cry proclaiming, Black lives matter! and also in the stands taken across the globe by Indigenous people and their supporters to protect the earth. Disposibility as a technology and extractivism as an operation are imbricated and proceed in violent unison as capital enters a new phase. Disposibility is marked by settler colonialism's "drive to elimination...[a] system of winner-take-all;" extractivism follows its own mandate of total depletion of all resources, also a system of grabbing everything. (Kauanui and Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism Then and Now")

Raul Zibechi analyzes the extractivist model as a new form of neoliberalism: "extractivism creates a dramatic situation —you might call it a campo without campesinos— because one part of the population is rendered useless by no longer being involved in production, by no longer being necessary to produce commodities." For Zibechi, "the extractivist model tends to generate a society without subjects. This is because there cannot be subjects within a scorched-earth model such as extractivism. There can only be objects." (see, Zibechi, "Extractivism creates a society without subjects") What does care look like at the end of capitalism? When we are longer bound by the relations of a commodity society?

South and North Bay Crew

NB: If you are not already signed-up and would like to stay connected with the emerging Universidad de la Tierra Califas community please feel free to subscribe to the Universidad de la Tierra Califas listserve at the following url <https://lists.resist.ca/cgibin/mailman/listinfo/unitierraca lifas>. Also, if you would like to review previous ateneo announcements and summaries please check out UT Califas web page. Additional information on the ateneo in general can be found at: <http://ccra.mitotedigital.org /ateneo>. Find us on tumblr at <https://uni-tierra-califas.tumblr.com>. Also follow us on twitter: @UTCalifas. Please note we will be shifting our schedule so that the Democracy Ateneo (San Jose) will convene on the fourth Saturday of every even month. The opposite, or odd month, will be reserved for the Fierce Care Ateneo (Oakland). In this way, we are making every effort to maintain an open, consistent space of insurgent learning and convivial research that covers both sides of the Bay. -- Center for Convivial Research at Autonomy

http://ggg.vostan.net/ccra/#1