#uniformology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Keith Windham’s Uniform: A Long and Highly Speculative Deep Dive into the Royal Scots’ Uniform in 1745

This is something I’ve wanted to research for a while—uniformology tends to be my favorite aspect of military life, so naturally, provided with a redcoat officer protagonist who quickly stole my heart as a character, I wanted to be able to do his uniform justice in my depictions of him. Let me first start by saying that there is no shortage of excellent art in this fandom, and furthermore, most of the uniforms I have seen depicted in said art actually seem quite well-researched and accurate, especially given the limited information available. I by no means pretend to be an expert on this matter—I am much more familiar with late 18th century AWI era uniforms, and even then I am no scholar—but this time period in uniform history is surprisingly elusive, and I felt inclined to find out more by doing a bit of a (admittedly self-indulgent) deep dive. This will be a long post, intended to be something of a reference, largely for myself, detailing the specific appearance of our Major Windham’s uniform as best I can.

It must first be established, however, that information on this specific period of uniform is scant. My first “launching point” was this excellent post by Bantarleton discussing British uniforms during the Jacobite Rising (which I highly recommend checking out for more qualified Speculation), which also served to corroborate what I was already beginning to see in my research: between the years of 1742 and 1751, we lack any solid evidence as to what British uniforms may have looked like. The hypothetical image I am assembling here is based, therefore, largely on educated speculation, as are most of the modern depictions of uniforms during this time period. Take all of this with a grain of salt, as you would any other historical post by a user on Tumblr, and bear in mind once again that I am not a scholar. But with that being said, we can begin in the closest place that we do have visual evidence: in 1742.

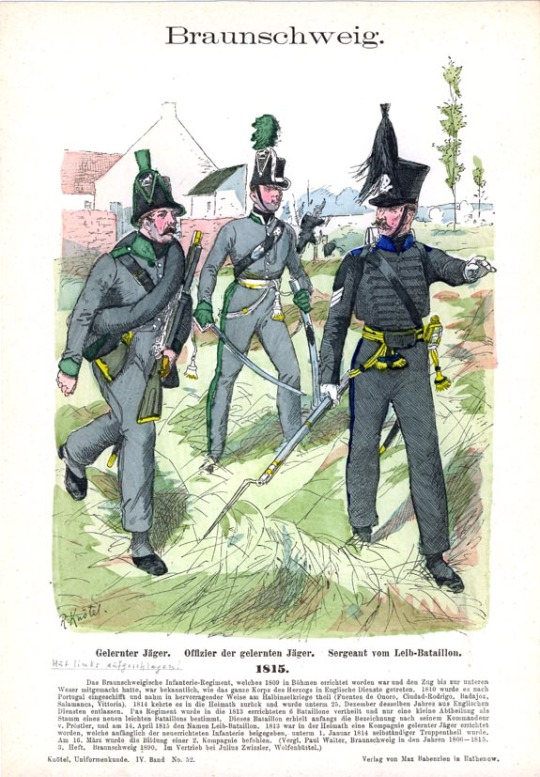

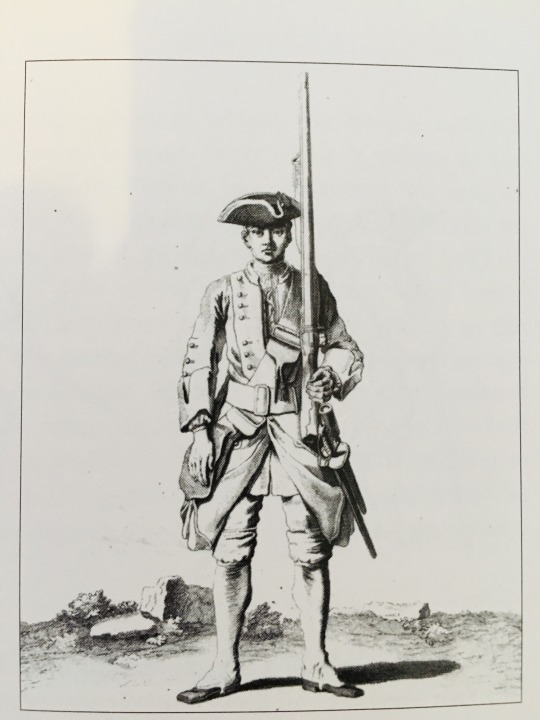

It was during this year that the Cloathing Book was commissioned by the Duke of Cumberland for King George II, which depicts the regular soldier’s regimental uniform across the military. Here we take a look at the 1st Royal Regiment (Royal Scots, though they would not be officially called that until the 19th century) uniform, which our Keith presumably would have worn some three years prior to canon, though assumedly not as a regular, which this soldier is.

Our second concrete visual of the same regimental uniform comes from 1751, portrayed by David Morier, who was commissioned probably by the Duke of Cumberland to paint a grenadier from each regiment. Why grenadiers, we can’t know—maybe for their fancy caps—but the uniform is essentially the same as would be the regular’s, with the exception of the cap (interestingly, I discovered the flanking company “wings” would be introduced only in 1752). The officers and the battalion men would all have been wearing cocked hats similar to the one portrayed in the previous photo.

Comparing the two, we see some changes in the silhouette and the smallclothes (in 1751 the breeches change to be blue instead of red), but nothing too drastic. I for one hadn’t realized that the Royal Scots would have been wearing red smallclothes during the mid century, as opposed to the white or buff. The one thing which does confuse me is the lack of lacing on the cuffs in 1742. Take this example, from the same collection, of a soldier from the 34th Regiment—notice the split cuffs and their elaborate lacing.

The artist seems to have been very deliberate in his depiction of the 1st’s uniform to include full cuffs without that extra lacing. Unfortunately I can’t seem to corroborate whether this was intentional or not, but my best guess is that it might have been a deliberate sign of the 1st Royals’ seniority: most regiments (like the 34th seen here) wore their own specific patterned lace, but the Royal Scots (at least during the mid 18th century) specifically wore plain white lace as a nod to the fact that they were the first and oldest regiment established in the British Army. It seems not impossible that this simpler cuff design might have been intended to convey the same sentiment. However, I can‘t say for sure whether this was the cuff in use during 1745, unfortunately. I would lean more toward the 1742 uniform for Keith’s just because it’s closer time-wise, but given that new uniforms were issued every year, it’s impossible to truly know how similar it would have been.

All that being said, it is important to acknowledge that we have been discussing regular soldiers up until this point: our Major Windham’s uniform would have borne some distinctions. This is a modern (so once again, speculative) illustration of an officer of the 7th Dragoon Guards in 1745, who, while not being an infantry soldier, would still have had a comparable uniform at the officers’ level, and provides a pretty good example of what some of these officers' distinctions might have looked like.

With regard to lace, officers’ uniforms of the 1st Royals were faced with gold lace as opposed to white, including on the hat. As mentioned before, as an officer, Keith would have been wearing a cocked hat with a black cockade on the left side, unlike the grenadier in the previous painting. While on duty, it seems likely that he would have worn a gilt gorget, though in a broader kind of half-moon shape than would be seen at the end of the century, and a sash, over his shoulder and the rest of his uniform rather than around his waist. He also would not have worn the crossbelts we see the regular soldiers wearing, and instead probably only a waist belt to hold his sword. Another important distinction would have been the gold aiguillette, a decorative knot to denote rank, rather than an epaulette like we see in the later century, on his right soldier, like the one on the dragoon officer’s shoulder here. An interesting but subtle detail would have been the fact that officers’ coats generally did not have the turned-back skirts associated with regular soldiers; the idea was that those soldiers would be moving around a lot more than the officers and therefore would need the extra room.

Another thing not specific to being an officer, but simply which differs from the paintings here, is that while on duty all soldiers (officers included) would have been wearing black gaiters, and not white. While, in my opinion, they do look fantastic (especially the full length mid century ones, unlike the late century half-gaiters��), white gaiters were reserved for parade because of how easily they could get dirty. While I’m here I suppose it’s worth listing off a couple general period details I often tend to forget about the mid-18th century, as someone who mentally lives in the 1770s: for one thing, military cocked hats were almost always worn slightly off to the side with the “point” angled over the left eye (you can kind of see it in the 1742 depiction). This was so that men could shoulder their firelocks without knocking their hats right off their head, and it became so much of a fashion that not only were officers (who were not bearing muskets) doing it, too, but also some civilians (and this lasted for a long time, pretty much until the army stopped wearing cocked hats). Also, it didn’t occur to me until recently that cravats were much more in fashion than stocks were during this period, and would have been tucked into a waistcoat that might have been even nearly half unbuttoned from the top, as was the fashion at the time.

But now I’m just rambling. I had fun learning about this and if someone else learns from it too, that’s just a bonus to me. Again, I'm not an expert; this is in no way meant to “correct” any of the depictions of Keith I’ve seen, or come off at all as being in bad faith. Almost everything I’ve said in this post is stuff I wasn't sure of myself until looking into, because this kind of thing is hard to know! As I said, most of the Keiths I see actually seem very well-researched and faithfully depicted. I just happen to love uniforms, and this man happens to have one (and a very good one at that). I would lean most heavily toward the 1742 version for Keith’s canon uniform if only because it’s closer in time to anything else we have, but who can really say what it looked like in real life? Some part of me is saddened to know we’ll likely never know, but thus is history. Hopefully knowing all this I’ll be able to do it some justice.

#wooooof.... long post#at some point hopefully i'll just like. draw it. but not today it's 2am#really interesting to look into though#one thing about me is I Love Uniforms#anyway#18thc#uniforms#flight of the heron#the flight of the heron#foth#keith windham#reference#jacobite rising#long post#redcoatposting#this is your captain speaking#haul up your queuegarnets#the captain's lectures

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

34 notes

·

View notes

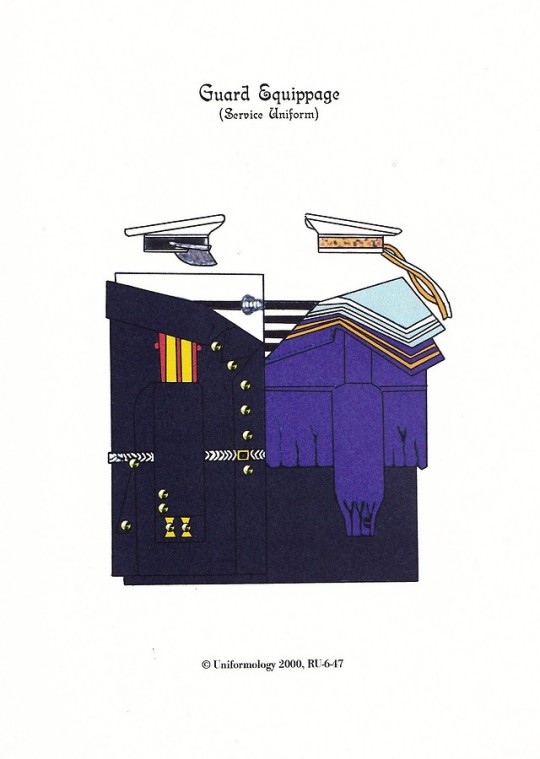

Photo

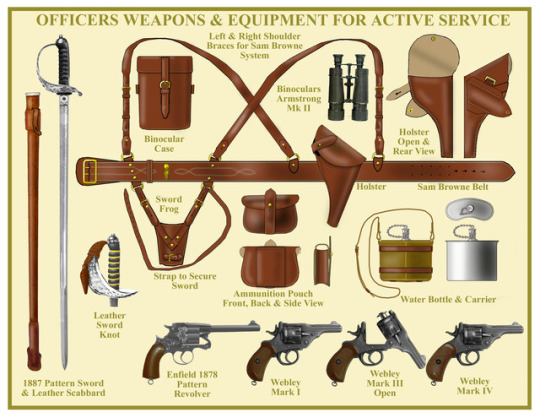

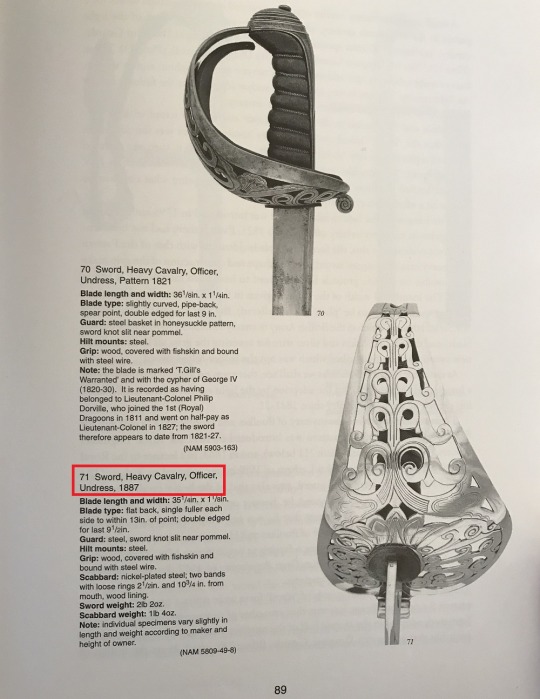

I really like the illustrations from Uniformology, however I have one small correction to make on this one. The sword in this illustration is a heavy cavalry officer’s undress (as opposed to dress) sword. It is labeled as an 1887 pattern, but there was never such a pattern. This mistaken identity arises from a misinterpretation of a caption of an photo in Swords of the British Army by Brian Robson:

The date of 1887 is the date this particular sword was made, not the year the sword became a regulation pattern. The swords illustrated at Uniformology and in Swords of the British Army are Pattern 1821 Heavy Cavalry Officers’ Swords. It is a very common mistake that I’ve seen repeated over and over again in various publications and online, and I really just nitpicking what is otherwise a very informative illustration.

Be sure to check out Uniformology for more on British military uniforms!

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outlander and the Real-World Mystery of What British Uniforms Looked Like in 1745

As folks can’t help but have noticed, I’ve been treating the TV series Outlander to all sorts of unpleasantness recently, but one of the most popular topics for historical pedants everywhere - namely uniformology - has raised interesting points that actually go beyond mere nitpicking with the show. The interesting, and frustrating, thing is we don’t actually have good evidence for just what British Army uniforms looked like during the 1745 Jacobite Uprising.

The basis of our knowledge for British uniforms in the 1740s is a text called the Cloathing Book. Officially commissioned in 1742 by the Duke of Cumberland for his father King George II, it shows the uniforms as worn by regular soldiers across the British Army, from line regiments to cavalry to “invalid” veterans. It gives us a pretty sound foundation for what soldiers probably looked like during the Jacobite Rising which did, after all, only occur three years later. But three years is a long time in the world of fashion.

The next quasi-official mass artistic rendering of what British soldiers were wearing occurred around 1751, when artist David Morier was commissioned to paint a grenadier from each regiment in the British Army, possibly for the Duke of Cumberland. The result shows us the changes that had occurred between 1742 and 1751, such as more elaborately laced, but less baggy cuffs, and waist belts being worn beneath coats rather than over them - elements that all mirrored the progress of popular fashion at the time.

Take the images below showing the same regiment, the 4th Foot or King’s Own, as depicted in 1742 and 1751. Leaving out the fact that one is a regular soldier and one is a grenadier (and thus has a different hat and shoulder lace), and the changes to aspects like the cuffs, skirts and general cut are fairly obvious.

But where does this leave us for 1745? Just how far along the path between 1742 and 1751 had uniforms progressed? Surely there must be more artwork depicting soldiers from those years?

The initial answer might seem to be “yes.” What about Hogarth’s famous work The March of the Guards to Finchley, depicting British soldiers marching to meet the Jacobites, or David Morier’s actual depiction of the battle of Culloden? Or, if seeking a less formal sketch, what of the charming depictions by Paul and Thomas Sandby, British Army cartographers who spent their spare time documenting Scotland’s landscapes and peoples in the aftermath of the uprising. Those are all near-as-damnit contemporary, right?

Well, actually, not really. Exact dates are almost impossible to pin down for any of these pieces. The famed (and excellent) Hogarth painting of the Guards was done in 1750. Sandby’s sketches (one below) are largely undated, but are believed to mostly fall around 1748 and 49. Bearing in mind that new uniforms were issued every year and the problem becomes clear.

And what of Morier? His artwork is popularly believed to show the 4th Foot engaging the Jacobites at Culloden. But if it’s meant to show the 4th, who we’ve seen above in 1742 and 1751, then it shows some curious variance. The cuffs are different shapes, the lapels narrower and the sleeves have a herringbone lace pattern, rather than the ladder pattern seen in ‘42 and ‘51. There’s also no lace on the skirts except, tantalisingly, in one case where the artist appears to have started to paint it in then stopped. Historian Stuart Reid hypothesizes that this points to the “Culloden” painting actually being done by Morier in the 1750s, a fact supported by the popular belief that he had members of the 4th stand in as real studies at his London studio - the 4th weren’t stationed in London until the 1750s.

In fact, the painting is probably not meant to be a direct depiction of Culloden at all. It is popularly known only as An Incident in the Rebellion of ‘45, and the first time it appears on record, in 1765, it is described simply as A Skirmish between some Highlanders and English Infantry.

As a final frustration, we cannot guarantee that the Cloathing Book itself is wholly accurate. A number of regiments are clearly based on the same standard template image, and we don’t know whether this was an artist cutting corners, or whether they were genuinely identical. We do have written evidence of uniform changes between 1742 and 1745, such as the instruction issued on November 17 1743 that ‘all the coats of the infantry be lappeled that are not so already, and that all be made with the same sort of pocket as the Scotch Fusiliers, viz., the plaits of the coat.’ This essentially removed the last of the old-style single-breasted jackets, such as those seen worn by the 20th Foot in 1742. Such documented evidence is few and far between, however.

What conclusions can we draw from all this? Well, basically, we don’t know exactly what uniforms looked like in 1745. Close, yes, but no guarantees. So let’s bring Outlander back in to make ourselves all feel better.

Obviously these lads are a mess, but just where have they gone wrong? It looks to me as though the costume designer has decided to base all his or her redcoats on the depiction of Ligonier’s 59th Foot from the 1742 Cloathing Book (image below). The most distinct thing about them is the lack of lace around the buttons, something considered by some to be evidence of another mistake in the 1742 book and something that, even if it were reality, probably still wouldn’t have been the case in 1745.

The baggy cuffs, incorrect button placement and poor cut of the garments (regimental tailors actually fitted each soldier’s coat to him during the period) are a bad start, as are the baggy gaiters and mismatching shoes, but things keep going south as we move onto the accouterments and weapons. The belts are certainly not the buff leather they ought to be and the cartridge pouches are likely too small and shouldn’t be that shade. No soldiers in the show appear to carry water canteens. Some of the muskets look suspiciously like later Short Land Pattern models. And the hats are best left unmentioned - ugly, poorly shaped, without lace, they look like they’ve come from a kid’s pirate Halloween costume.

Am I being harsh? Possible. It is, after all, a TV show, not a documentary (and it’s not like they often get it right either). Never-the-less, the information for making good, educated guesses is out there. I’m not saying we should see a whole battalion of British infantry in tailored, hand-stitched uniforms. But implementing some better research would have yielded a better look without necessarily hitting the budget any harder. On the bright side, at least it gives history nerds something to complain about.

#outlander#history#scottish history#british army#18th century#redcoat#redcoats#fashion#military history#scotland#scottish#jacobite#jacobites#the 45#1745#culloden#battle of Culloden

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

WWI British & French references

Here is a list of references I recommend for reenacting and/or collecting uniforms & items from the British & French armies of the Great War. I have read and seen a lot more on the matter but those are what I consider the most useful and/or interesting refs.

They include uniformology references but also books about the general experience of WWI to help one undertake the role.

British

Uniforms & Items.

British Uniforms & Equipment of the Great War, 1914-18 - John Bodsworth

Uniforms & Equipment Of The British Army In World War I: A Study In Period Photographs - Stephen Chambers

Karkee Web (for webbing & equipment information).

Campaign 1914 - Chris Pollendine

Great War Tommy: The British soldier 1914-1918 - Peter Doyle (I also recommend the whole range of Doyle’s books).

Soldiers’ Accoutrements of the British Army 1750-1900 - Pierre Turner

The British Army in World War I (1 and 2) - Mike Chappell

The British Army 1914-1918 - Donald Fosten & Robert Marrion

The Old Contemptibles - Michael Barthorp

British Battle Insignia (1) - Mike Chappell (only if you know what regiment you are aiming at).

From Tradition to Protection: British military headgear in WW1 - In Flanders Fields’ Museum

General knowledge.

(mostly biased towards subaltern officers -- sorry!)

(Period) Infantry Manual 1914. Planned for officers but suitable to learn drill for all ranks

Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War - John Lewis-Stempel

The British Army in the Great War - Frederick Hadley

(Period) Diary of Edwin Campion Vaughan. (published under modern title ‘Some Desperate Glory’)

Epitaphs of the Great War series - Sarah Wearne. Interesting and emotional insight into period mindset

(Period) Journey’s End - R. C. Sherriff

[FR] Tommy 1914-1918 - Lawrence Brown & Faris Siwadi

[FR] Join Now! L’entrée en guerre de l’Empire britannique - Great War Museum of Meaux

(Period) 24 Hours on the Somme - Edward Liveing

Arms & Uniforms of WWI - Liliane & Fred Funcken

______________________________________________________

French

Uniforms & Items.

[FR] Gazette des Uniformes : L’équipement du Poilu 1914-18

[FR] Gazette des Uniformes : L’uniforme du Poilu 1914-18

[FR] Uniformes : Le Poilu de la Grande Guerre

[FR] Website Les Français à Verdun

Website of the reenactment group 151 RIL

[FR] Le soldat français dans la Grande Guerre - Christophe Fombaron

The French Army 1914-18 - Ian Sumner

From Tradition to Protection: French military headgear in WW1 - In Flanders Fields’ Museum

[FR] Very complete website about M15 Adrian helmets

General knowledge.

Apocalypse: The First World War (film & books)

Arms & Uniforms of WWI - Liliane & Fred Funcken

[FR] Paroles de Poilus - Jean-Pierre Guéno

(Period) Fear - Gabriel Chevallier

(Period) Under Fire - Henri Barbusse

(Unfortunately, this list is quite empty because, for my impression, I mostly used books related to my specific regiment, the Corsican 173rd Infantry Regiment. Therefore, they would be quite pointless to list here if you are not interested in this specific unit).

Hope this could help!

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

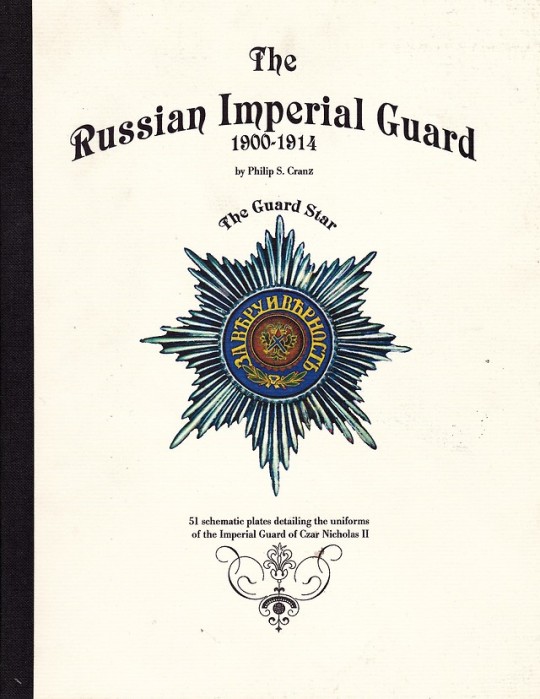

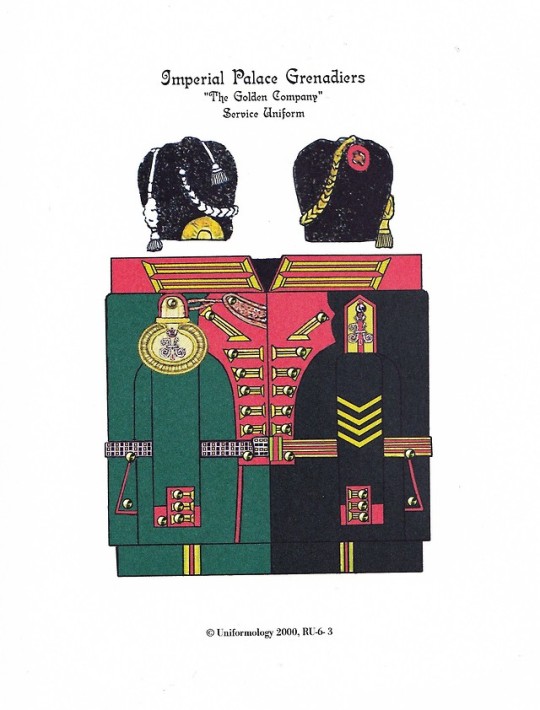

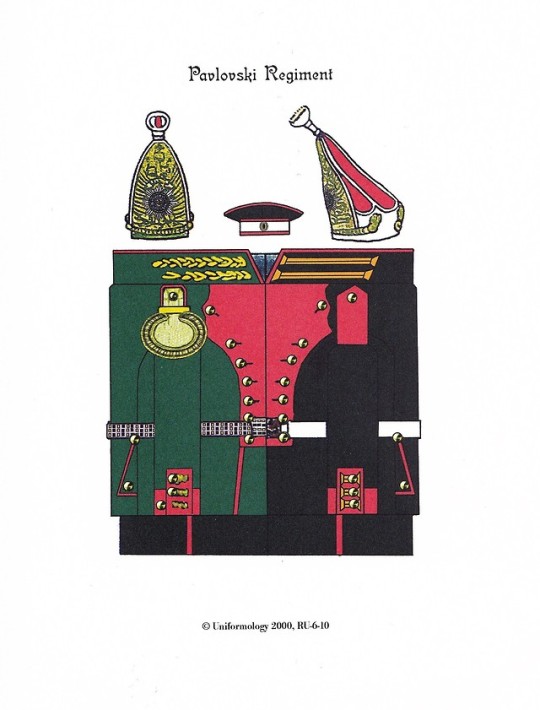

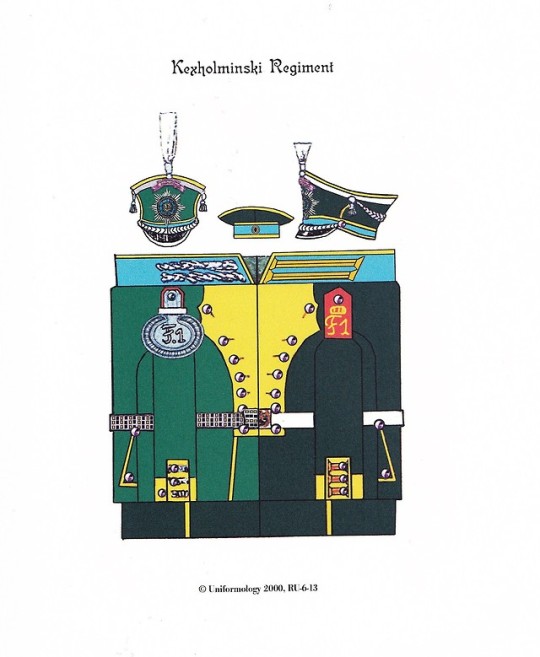

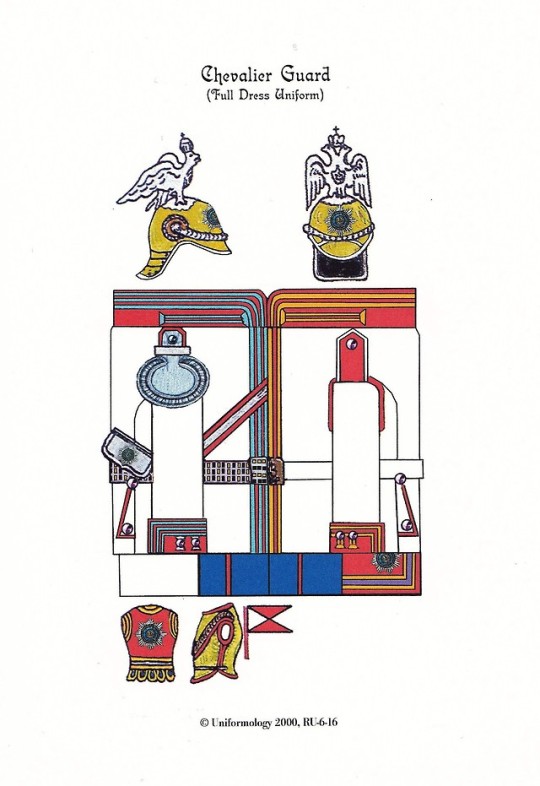

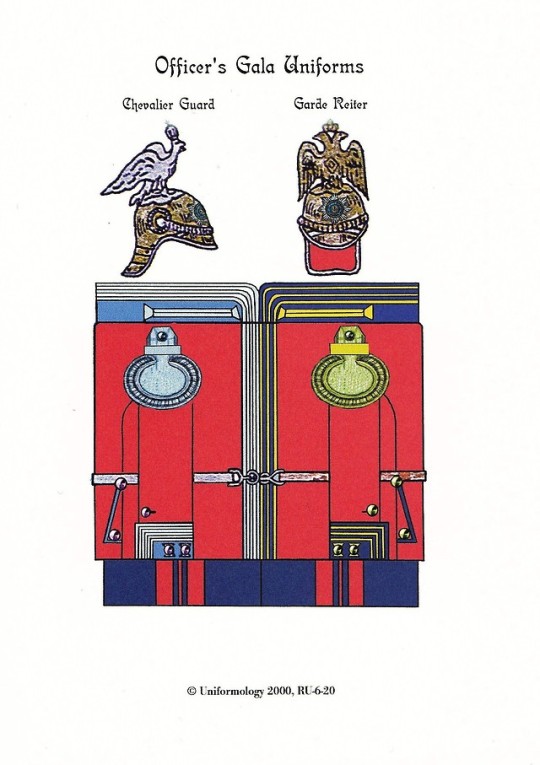

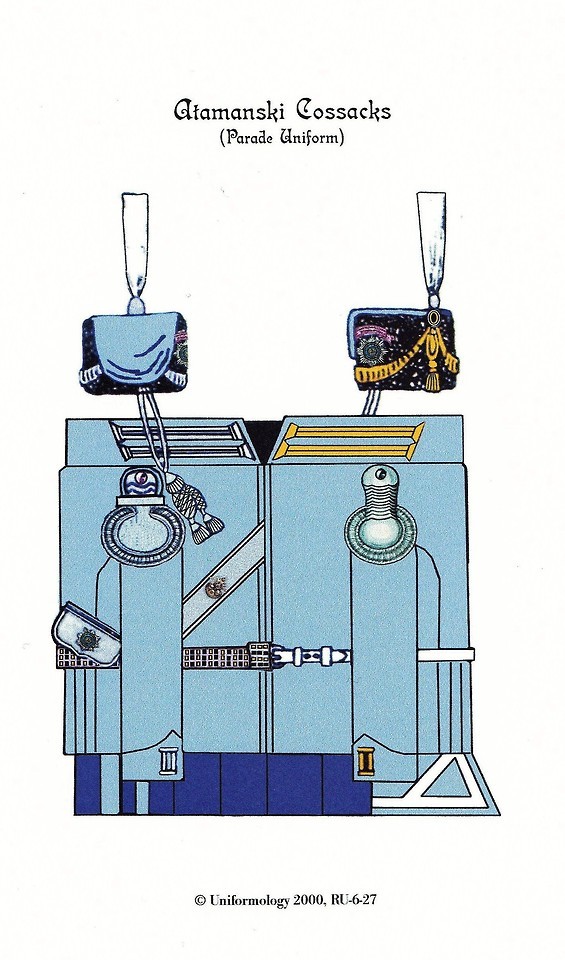

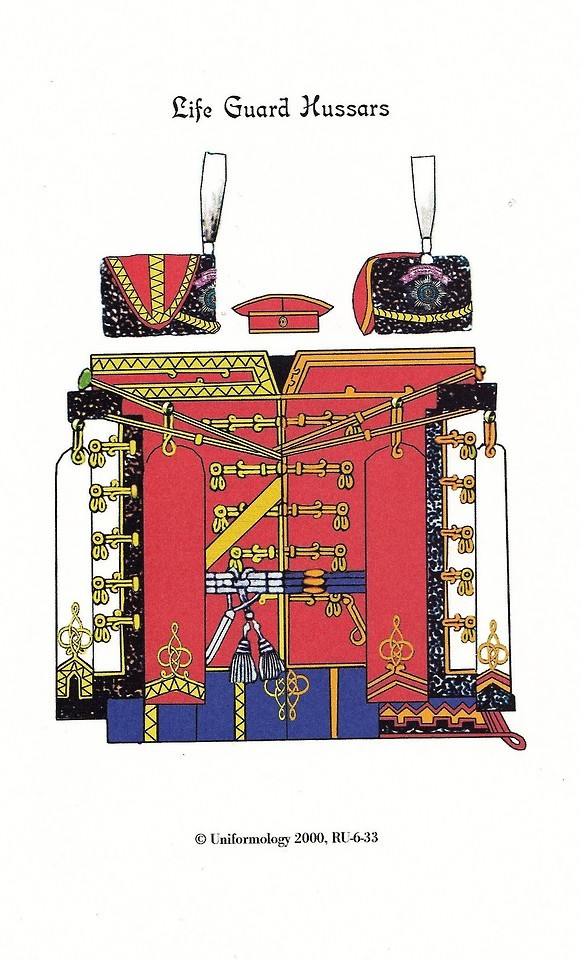

The Russian Imperial Guard 1900-1914

51 schematic plates detailing the uniforms of the Imperial Guards of the Czar Nicholas II

by Philip S. Cranz

Uniformology ,Weatherford 2006, 58 pages

euro 45,00*

email if you want to buy :[email protected]

Collection of 51 schematic plates covers each regiment of the Imperial Guard of Czar Nicholas II - the last Russian Czar. After the disastrous war with Japan in 1904-5, Czar Nicholas II ordered sweeping reforms for the Russian Army. Among these, in an attempt to restore pride and confidence was a change in dress uniforms. This change reversed the draconian reforms of Alexander III in 1881 when simple peasant style uniforms were adopted and all cavalry became dragoons. Now the hussars, lancers and cuirassiers returned (the latter converted to dragoons) with distinctive and attractive uniforms. Not least of these affected the Imperial Guard where uniforms reached their apogee in terms of magnificence.

orders to: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

flickr: fashionbooksmilano

instagram: fashionbooksmilano

tumblr: fashionbooksmilano

#Russian Imperial Guard#uniformology#hussars#lancers#cuisarriers#uniforms#uniformi militari#grenadiers#fashion inspirations#uniforms books#fashionbooksmilano

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

13 notes

·

View notes