#tunisian cinema

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Golshifteh Farahani as Selma Derwich ARAB BLUES / UN DIVAN À TUNIS (2019) dir. Manele Labidi

#arab blues#un divan à tunis#golshifteh farahani#2010s#tunisia#tunisian cinema#by kraina#filmedit#worldcinemaedit#fuckyeahwomenfilmdirectors#shesnake#underbetelgeuse#userrobin#userkd#userdanahscott#userhugh#usertennant#userraffa#userteri#userjean

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

La mort trouble (1970), dir. Férid Boughedir & Claude d’Anna

473 notes

·

View notes

Text

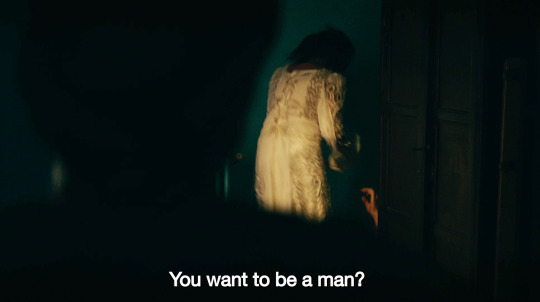

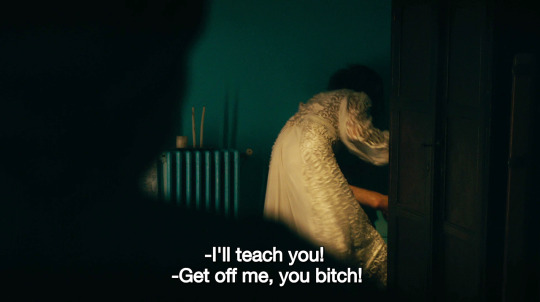

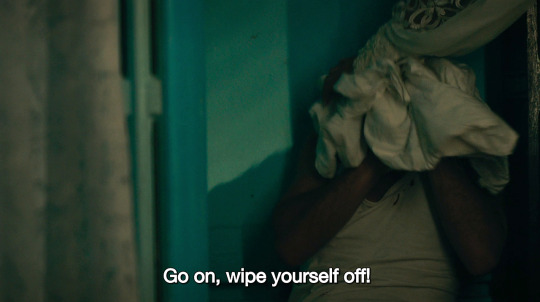

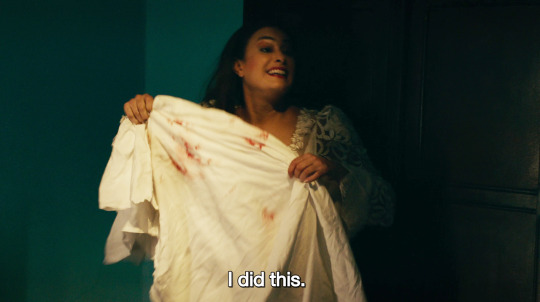

FOUR DAUGHTERS (2023, Kaouther Ben Hania) Cinematography by Farouk Laâridh

Between light and darkness stands Olfa, a Tunisian woman and the mother of four daughters. One day, her two older daughters disappear. To fill in their absence, the filmmaker Kaouther Ben Hania invites professional actresses and invents a unique cinema experience that will lift the veil on Olfa and her daughters’ life stories.

#les filles d'olfa#four daughters#documentary#four daughters 2023#kaouther ben hania#farouk laaridh#Olfa Hamrouni#Hind Sabri#dailyworldcinema#screencaps#filmedit#filmtag#shesnake#post#tunisian cinema

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

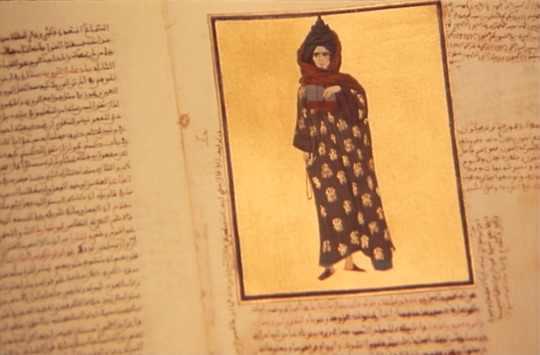

الهائمون (Wanderers of the Desert | Nacer Khemir | 1984)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un été à la Goulette (1996) dir. Férid Boughedir

#un ete a la goulette#a summer in la goulette#ferid boughedir#1996#90s films#screencaps#stills#film stills#tunisian cinema#sonia mankaï

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dachra (2018)

Yasmine is more prepared to survive horror movies than anyone else. Every beat where she is offered an alternative, she just wants to get the hell out. Good instinct. The alternative, chosen or otherwise, doesn’t lead anywhere good in this sort of situation. Uncertainty and confusion reign supreme here as a group of journalism students go beyond the pale to research a story. It’s certainly not bland. But what they get is a tale of terror quite unlike anything they are prepared to cover. Men unwilling to tell the truth. Women unwilling to speak. It’s all about nondescript meat, and precious little told otherwise.

The cinematography employed is seriously impressive for a first effort in the genre. After the group are led into the depths of hell in a remote village, the night of uncertainty is captured in pools of light, deep shadows, and flashes of strobelit nerves. It’s moody and paranoid, the danger present for the character palpable to the viewer as well. Nobody came screaming out of the darkness, but just how dangerous the moment was for Yasmine was still clear to the viewer. Equally frightenening was the erratic behavior of the child in the Don’t Look Now rain jacket; nothing short of the avatar of evil in any given moment.

THE RULES

SIP

Someone says 'Mongia'.

Asymmetrical framing of faces in a scene.

Witchcraft is mentioned.

The investigation hits a dead-end.

BIG DRINK

A nightmare sequence begins.

Obviously bullshit excuses are thrown around.

#drinking games#dachra#abdelhamid bouchnak#horror#horror & thriller#tunisian cinema#cannibal witches

0 notes

Note

can you tell me more about greeks from eastern europe and MeNa ? I cant find anything on them

Anon, when you were asking this, I assume you did not expect it would start an Odyssey for me. The ask was literally a "tell me more about the Greeks of three continents" and I... complied. It took me 20 days but I kinda wrote a book here. It was not easy. I used the English Wikipedia for sources. You can look there for more information.

I should note I did not include the Cypriot Greeks in this because I assumed you did not mean Greeks who have their own sovereign state. So, ultimately this is about Greek minorities. The topic of a minority - any minority - is always sensitive. As a result, some information here might be unpleasant. The purpose of the post is not to provoke or cause any controversy. It is only the truth of Greek people living outside Greece and Cyprus.

This post is only about the Greeks specifically from the areas Anon asked about.

Chapters:

Egyptian Greeks

Sudanese, Tunisian and Libyan Greeks

Greeks of Albania

Ukrainian Greeks

Greeks of Russia and other Caucasus Greeks (including those of Georgia and Armenia)

Greeks of Romania and Moldova

Greeks of Bulgaria

Greeks in the Republic of North Macedonia

Greek presence in Hungary, Czechia, Poland and Serbia

Greeks of Syria and Lebanon

Greeks of Israel and Palestine

Greeks of Turkey

North Africa

Egyptian Greeks (Egyptiótes / Alexandriní)

One of the historically most prolific Greek minorities. While mercenaries and other small groups of Greeks had settled in Egypt centuries earlier, they really established themselves there during Alexander's conquests in the Hellenistic period. Ever since, they have been mostly concentrated around Alexandria, the city Alexander had built and named after himself, and later also Cairo, so they always formed an urban social class. Alexandria was a Greek hub for the longest time, throughout the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the Byzantine Empire and even the Ottoman times. Their numbers however had reached their lowest in the 18th century but a new surge of Greeks migrated to Egypt in the meantime, because by 1920 they were 200,000 and by 1940 they were 300,000. Greeks of Egypt were rich, owning banks, tobacco industries, cotton fields and many more businesses. They published several Greek newspapers and had their own theatres and cinemas. The Egyptian Greeks produced many artists, some of whom are amongst the most important Greek poets. Egyptian Greeks volunteered and participated in all wars Greece has been in. There were also many benefactors of the Greek state amongst them like Antonis Benakis for example, who founded the Benaki museums in Greece. In fact, a large number of Modern Greek artists and celebrities were or are descended from Egyptian Greeks. Greeks started leaving Egypt at the times of the coup d'etat of 1952 and the rise of the Pan-Arab nationalism. Nowadays, their number has fallen at around 7,000 while others changed their nationality to Egyptian. However, they are still centered around Alexandria and their churches and schools are still functioning. In Alexandria, apart from the Patriarchate, there is a Patriarchal theology school that opened recently after 480 years being closed. During the last decades, Greco-Egyptian relations have improved again a lot and this affects positively the Greek diaspora there.

A few notable Greeks of Egypt; note the poet Constantine Cavafy (upper row, right) and the nobellist poet George Seferis (lower row, middle).

Greek school play in Cairo for the Greek independence, 2017 - 2018.

Sudanese, Tunisian and Libyan Greeks

Greeks of North Africa are overwhelmingly concentrated in Egypt. However, there are tiny Greek communities in Libya, Sudan, South Sudan and Tunisia and they have a long history. Libyan Greeks are about 1,500 and are mostly descended from Crete. Greeks have been interacting with Nubians and the Sudanese over the course of millenias. In the Ottoman times, many Greeks arrived there, especially Greek Arvanites, as Ottoman mercenaries. After that they grew to around 7,000 people. Although always very few, they became quite influential to the Sudanese society, making industries, famous products, newspapers and running successful businesses. Around certain parts in Sudan one can still see old Greek advertisements and abandoned Greek named shops. Due to the unrest in Sudan and the rise of the Sharia Law, most Greeks abandoned the country. They are now only about 200 in North and South Sudan and yet they are still the largest European community of the country (so I read). In Tunisia the Greeks are fewer than 100 although in the 19th century they were more than 8,000 and most were sponge divers descended from the Dodecanese islands.

Sudanese Greek families of Khartoum, 1898.

Eastern Europe and Caucasus

Greeks of Albania (Northern Epirotes)

The Greek minority of Albania is the currently largest Greek minority in Eastern Europe and it is officially recognized by the Albanian state as the Greek National Minority of Albania. It is concentrated in the southern part of the country, particularly in the districts of Sarandë (Áyii Saránda), Gjirokaster (Argirókastro) and Vlorë (Avlóna) . There are hugely conflicting estimations of the Greek minority's numbers between the Albanian and the Greek state census. Western estimations place them around 200,000 though. There are also concerns of human right violations, with allegations that the police and secret services target the Greek minority. Greek communities have been targeted by development projects and had their homes demolished. Due to their proximity to Greece, the Greeks of Albania essentially speak Standard Modern Greek and are mostly indistinguishable from the Epirotes of Greece. A lot of them migrate to Greece at this point.

Greeks from Dropull, Albania in folk attires.

Ukrainian Greeks

The 2001 Ukrainian census counted 91,548 ethnic Greeks in Ukraine. They reside mostly in Donetsk and particularly in Mariupol city, which is why the most common dialect there is called Mariupolitan Greek. Greeks have been settling to Ukrainian territories since antiquity but most Ukrainian Greeks are descended from Pontic and Caucasus Greeks . However, some are also Urums, Tatar-speaking Greek Orthodox people of Crimea. They are very well intergrated to the Ukrainian state.

Greeks of Ukraine

Greeks of Russia and other Caucasus Greeks (including those of Georgia and Armenia)

Greeks have been settling to Caucasus and the southwestern regions of Russia since antiquity. The history of the Greeks in Russia has had ups and downs, sometimes enjoying privileges or tolerance and sometimes suffering suppression along all other ethnic minorities. This was the case both in Tsarist and Soviet Russia. More than half a million Greeks lived in the Russian Empire pre-Russian Revolution. Notable Greeks have been born or have lived in Russia, a prime example being the Heptanesian-born Ioannis Kapodistrias serving as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Russian Empire. Lenin supported the Greek community, only for Stalin to blow things up by deporting large numbers of Greeks to Kazakhstan. In general, Greeks mostly left Russia during Soviet times but things weren't always as bad as in Stalin's times. Most Greeks of Russia speak Pontic Greek, however in the operating Greek schools now they are learning Standard Demotic Greek. In 2010, the Russian census recorded 85,640 Greeks but in the 2021 census the number was 53,972...

Like said above, while Greeks inhabited Caucasus since the 7th century BC, most Caucasus Greeks nowadays originate from Pontos and East Anatolia, modern-day Turkey, and were emigrating to Russian, Georgian and Armenian highlands usually due to the Ottoman conquests and the very tense relations with the Turks. A bright exception occured in 1763 when 800 Greek households were moved to modern-day Armenia by King Heraclius II of Georgia in order to develop silver and lead mining. Their descendants still live in Marneuli district in modern-day Georgia. Greeks of Georgia, both Pontians and Urums, largely maintained their ethnic identity. Most started emigrating to Greece in the 20th century and especially during the 1992-1993 war in Abkhazia. Some who tried to return for vacations to their properties in Georgia found state efforts to uproot the remnants of the minority by favouring ethnic Georgians, reporting violence, looting and occupation of Greek houses. In 2005 the Council of Greeks in Georgia has appealed to the World Council of Hellenes, SAE, registering their fear caused by the increasing instances of previously rare ethnic violence against them. The matter was also discussed in the parliament of Greece. In any case, in 2002 there were still 15,166 Greeks living in Georgia but it is a dramatic decrease from 1989's 100,324. Georgian Greeks traditionally viewed Greece as the "Promised Land", dreaming to move there at some point. However, when they actually started doing that in the 90s, they experienced a cultural shock they did not expect. A few of them initially had some trouble to integrate into the society. This was perhaps the reason Georgian Greeks unfortunately even face some level of prejuidice within Greece, where they are sometimes called Russo-Pontians (Ρωσοπόντιοι). These issues are fading now though.

Despite the excellent relations of Greeks and Armenians, few Greeks reside in Armenia. According to an Armenian scientific research in 2002, around 6,000 Greeks lived in the country, however in the Armenian census of 2011 there were only 900 registered. The reasons for the decrease in their numbers is emigration to Greece and the West for financial reasons.

Caucasus Greeks from Batumi, Georgia, early 20th century.

Greeks of Romania and Moldova

Greeks are a very small but historic minority of Romania and Moldova. Again, first settling in the 7th century BC, they maintained a presence there throughout the Middle Ages, due to the Orthodox influence of the Byzantine Empire. So much so that even during the Ottoman times, Greeks were still considered the most significant promoters and representatives of the Orthodox faith, enjoying thus a big status in these regions, enforced by the Ottomans who did not trust Romanian rulers. Many Greek Phanariotes (elite Greeks of Constantinople) rose to nobility and royalty and became Voivodes (princes) of Wallachia and Moldavia. In the early 19th century, the Greek princes and nobles of the Danubian principalities became directly involved in the preparation of the Greek Revolution against the Ottoman Empire. In Chișinău, the capital of Moldova, the oldest surving building of the city once housed the Filiki Eteria (Society of Friends), the secret organisation that prepared the Greek Revolution. Its appointed leader Alexander Ypsilantis was the Greek Voivode of Wallachia. After the Greek Independence and ever since, Greeks gradually lost this status of nobility and were integrated into Romanian society. A lot of notable Greeks are Romanian Greeks. Nowadays, the emigration routes have shifted a lot and Romania has a Greek minority of about 14,000. In Moldova, the ethnic Greeks are no more than 3,000-4,000.

Portrait of Ioannis Georgios Karatzas (Ioan Caradja), Prince of Hungaro-Wallachia, with his granddaughter Eleni Argyropoulou, crayons and chalk on paper, 1821.

Greeks of Bulgaria / Sarakatsani

Historically there were Greeks settled in the region of Bulgaria since the 7th century BC, given also its proximity to Greece. Due to the Macedonian Struggle and the two Balkan Wars it's very hard to find safe estimations of how many Greeks truly lived there. In any case, Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey underwent critical population exchanges with each other and most Greeks of Bulgaria sooner or later moved to Greece. The Bulgarian census of 2011 reported 3,935 Greeks (this making them the fourth largest ethnic minority in the country), whereas the Greek government estimated them at 25,000 - 28,500. The reason for this gap is that the Bulgarian government does not recognize the Sarakatsani as ethnic Greeks, instead pushing for Vlach, Slavic or Thracian origin theories, which are making the preservation of the community's ethnic identity harder and harder. This is why in February 2023 the head committee of the Sarakatsani Associations of Bulgaria and the head committee of the Sarakatsani Associations (Greece) visited the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Hellenic Parliament to ask from the Greek State to push the matter of granting Greek nationality to the Sarakatsani of Bulgaria.

The Sarakatsani are a nomadic group which originates from the mountains of Greece and speak a northern Greek dialect with several archaic elements.

Sarakatsani girls of Bulgaria

Greeks in the Republic of North Macedonia

Nowadays, the Greeks of the neighbouring country are 294. They originate mostly from Greek refugees from the Civil War. I don't actually doubt that number because a) it is a small country and b) I don't think many Greeks would live there or be registered as Greeks now given the tensions between the two countries. However, the Greek presence in the region can be traced since 2,000 BC but of course everything is denied prior to the refugees of the 40s - 50s. Until about 1690, the Greek Christian population was the majority according to Ottoman demographics. Since then the rise of Slavic nationalism caused trouble to the Greek community, which gradually started to shrink. The two hotspots of Greek presence were Gevgelija (Yévyeli) and Bitola or Monastir (Monastiri). In 1878, 10,000 Greek signatures were gathered in Skopje against the Treaty of San Stefano, which was empowering Bulgarian and minimizing Greek claims. When the area passed under the control of Serbia in 1913, one fourth of the Bitola population was Greeks. There were also villages with only Greek population. In the census of 1941, German Axis forces counted 100,000 Greeks out of an overall population of 800,000 in the entire region. The census of 1951 counts 158,000 Greeks, most of Vlach descent, but the rise in number is indeed due to the influx of Greek refugees of the Civil War. Surprisingly, during the 1991 census after the establishment of the republic, the opposition party revealed that about 12 - 18% of the population claimed Greek ethnic consciousness. Now they are 294 according to the census.

Greek demonstration in Bitola, 1905.

Greek school in Gevgelija, 1900. It was one of the four Greek schools operating in the city.

The first organisation for the pro-Greek side of the Macedonian Struggle in Gevgelija, 1904.

Greek presence in Hungary, Poland, Czechia and Serbia

In Hungary, Poland and Czechia the Greek minorities are very small, counting about 3,500 - 4,000 people in each. Greeks settled in these places since the Middle Ages but most Greeks there originate from migrations during the Greek Civil War. In Hungary the Greek minority is one of the 13 officially recognized minorities of the country. The Greek-founded village Beloiannisz (named after Beloyannis) traditionally has a Greek mayor, even though the Greek population of the village is not the majority anymore..

Despite the excellent relations, few Greeks live in Serbia. About 690 Greeks are registered but there are another 4,500 people of Greek ancestry. The small Greek minority is officially recognized by the Serbian government.

Near East

Greeks of Syria and Lebanon (Antiochean and Levantine Greeks)

Greek presence in Syria and Lebanon had been strong since ancient times, even before Alexander the Great's conquests, but it was reinforced constantly throughout the Hellenistic, the Roman and the Byzantine periods. The first massive blow to the Greek population there was the Arab conquest in the 7th century. The second blow was the vindictive measures Ottoman Turks took against Greeks of the Near Eastern lands of the empire as a warning to not aid the Greeks of Greece in the Independence War. Nowadays, 4,500 Christian Greeks live in Syria. However, following the Greco-Turkish War in 1897–98, in which the Ottoman Empire lost Crete to the Kingdom of Greece, Sultan Abdul Hamid II resettled in Syria and Lebanon significant numbers of Greek Muslims originally from Ottoman Crete. Nowadays, there are 7,000 and 8,000 Greek-speaking Muslims of Cretan origin in Lebanon and in Al-Hamidiyah, Syria respectively. Many of them still speak Greek as their first language. By 1988, many Greek Muslims from both Lebanon and Syria had reported being subject to discrimination by the Greek embassy because of their religious affiliation. The community members would be regarded with indifference and even hostility and would be denied visas and opportunities to improve their Greek through trips to Greece. Scary, but true. Due to the Syrian Civil War, many Muslim Syrian Greeks moved to Cyprus or back to Crete. Many Greeks left Lebanon due to the Israel invasion in 2006.

Greek kids of Damascus celebrating the Ohi (No) National Day.

Lebanon Greeks in a traditional dance.

Greeks of Israel and Palestine

There is a theory popular with the scholars that the Philistines, ancient people of Palestine, originate from Aegean Greek populations who migrated there in the Iron Age. What's certain is that later, after the conquests of Alexander the Great and the consequent conquests of the Romans the regions were and remained for a long time significantly hellenized. Ashkelon, Jaffa, Jerusalem and Gaza were in fact the most hellenized areas. During the Byzantine period, the populations there reached their peak and a considerable part of them were Greeks. The Greek presence was reduced significantly with the Arab conquest of the 7th century. Nowadays, the Greek community there is small. There are about 1,500 - 2,500 non-Jewish Greeks. There are however also 1,000 - 6,000 Greek Jews (Romaniote and Sephardic) who originate from Greece Jews who moved to the modern State of Israel after its establishment. Greek expatriates comprise most of the leadership of the Eastern Greek Orthodox Church in Israel and the Palestinian Territories and of course the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, in an arrangement that predates the modern State of Israel.

Theophilos III, the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem.

Greeks of Turkey (Anatolian, Pontic, Constantinopolitan and Cappadocian Greeks)

It's hard to summarize the story here. Greeks settled in Asia Minor in the 13th century BC. While Asia Minor was a hub of ancient peoples and cultures, most of them faded due to infighting with each other. In these circumstances, the Greek colonies prospered and the Greek influence spread thoroughly throughout the land. In the archaic period already western Anatolia was structured in Greek city-states, not different from what was happening in the Greek mainland. Many of the most famous ancient Greeks were from Anatolia. While the Greek presence there was never threatened, the Greek influence was antagonized by that of the Persian Empire, with the Greek city-states often being under its control. Alexander the Great's wars with the Persian Empire and the establishment of the Diadochi Kingdoms in the 4th - 1st century BC simply reinforced the Greek presence there for centuries to come. From that point onwards the population of the region was predominantly Greek. This was not changed by the Romans who allowed the Greek language and the Greek culture to remain the principal one in the whole east half of the empire. In 330 AD the emperor Constantine the Great founded the city of Constantinople on the older site of the Greek city Byzantion. This city soon became the largest and wealthiest in the world in the Middle Ages and it was the most significant hotspot of the medieval Greek culture and language. The region of Asia Minor was the most prosperous region of the Byzantine Empire for most of its history. Many Byzantine Emperors were of Anatolian / Cappadocian Greek descent. However, in the end of the 11th century the Byzantine Empire lost these lands to a new coming force from the east, the Seljuq Turks. Some of these losses were reversed but it was ultimately the beginning of the end. The sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 and the formation of Latin states throughout Greece dismantled the empire completely and while it made valiant efforts to resurrect itself, it did not manage to fortify itself against the next threat. By the middle of the 15th century, the new coming force of the Ottoman Turks had conquered Asia Minor, Constantinople and the Greek mainland.

Asia Minor Greeks remained subjects of the Ottoman Empire for the centuries to come. Due to the policy of religious tolerance, the Anatolian Greeks managed to keep their faith and their identity effectively preserved. In spite of that, the Ottoman society favoured Muslims significantly and many Greeks converted to Islam and progressively lost their identity.

Cappadocian Greeks (Karamanlides)

During the 16th century the region of Cappadocia became largely Turkified in culture and language through a gradual process of acculturation, as a result many Greeks of Anatolia had accepted the Turkish vernacular and some of whom later became known as Karamanlides. Although the Karamanlides abandoned Greek when they learned Turkish, they remained Greek Orthodox Christians and continued to write using the Greek alphabet. Cappadocian Greeks would migrate to Constantinople and other large cities to do business. By the 19th century, many were wealthy, educated and westernized and several reclaimed their native tongue. In the early 20th century, Greek settlements were still both numerous and widespread throughout most of today’s Turkey. The Cappadocian Greeks of the 19th and 20th centuries were renowned for the richness of their folktales and preservation of their ancient Greek tongue. The underground cities of Cappadocia continued to be used as refuges from the Turkish Muslim rulers as late as the 20th century. By the beginning of the First World War, the Greeks of Anatolia were besieged by the Young Turks. Cappadocian Greek deaths alone totaled 397,000. In 1924, after living in Cappadocia for thousands of years the remaining Cappadocian Greeks were expelled to Greece as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey defined by the Treaty of Lausanne. The descendants of the Cappadocian Greeks who had converted to Islam were not included in the population exchange and remained in Cappadocia, some still speaking the Cappadocian Greek language. Following the population exchange there was still a substantial community of Cappadocian Greeks living in Turkey, in Constantinople, the majority of whom also migrated to Greece following the Anti-Greek Istanbul Pogrom riots of 1955. Today the descendants of the Cappadocian Greeks can be found throughout Greece, as well as in countries around the world. The modern region of Cappadocia is famous with tourists and has more than 700 Greek Orthodox churches and over thirty rock-carved chapels, many with preserved painted icons, Greek writing and frescos, some from the pre-iconoclastic period that date back as far as the 6th century, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Notable Cappadocian Greeks.

Pontic Greeks

Pontic or Pontian Greeks are the ethnic Greeks indigenous to the region of Pontus (pontos, Greek for "sea"), the northern coastal area of Turkey in the Black Sea. They speak the Pontic Greek dialect, which they also call Romeika, like Greek was often called in the Byzantine times. This dialect retains many archaic elements. Large communities (around 25% of the population) of Christian Pontic Greeks remained throughout the Pontus area until the 1920s, preserving their own distinct customs and dialect of Greek. Between 1913 and 1923, the Ottoman leadership attempted to expel or kill its native Christian population of Anatolia, including the Pontic Greeks. Different scholars have made different estimates for the death toll; most estimates range from 300,000 to 360,000 Pontic Greeks killed. Many were executed, others were subject to massacres; many Pontic men were forced to work in labor camps until they died; still others were deported to the interior on death marches. Rape, primarily of Pontic women and girls, was prominent. In 1923 those still remaining in Turkey were exiled to Greece as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey defined by the Treaty of Lausanne. Nowadays, there are about 5,000 Greeks remaining in their lands of Pontus. However, some Greek sources exploring the possibility of crypto-Christianity in Turkey speak of estimations around 345,000. In any case, most of their descendants now live in Greece, nearing half a million. The total Pontic Greek population across the globe (including the diaspora) is estimated as two to two and a half million people. Pontians are amongst the proudest Greeks and preserve their culture and customs carefully. The sense of Greek ethnic identity of the Pontians remaining in Turkey however is severely endangered.

Pontic Greek students in Trebizond, 1902 - 1903.

Greeks of Constantinople and the rest of the Anatolian Greeks

A class of moneyed ethnically Greek merchants called Phanariotes emerged in the latter half of the 16th century and went on to exercise great influence in the administration in the Ottoman Empire's Balkan domains in the 18th century. For all their cosmopolitanism and often western education, the Phanariotes were aware of their Hellenism. In the early 19th century, two out of the three major centers of Greek learning were in Anatolia; Smyrna (Izmir) and Aivali (Ayvalik). The outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in March 1821 was met by mass executions, pogrom-style attacks, the destruction of churches, and looting of Greek properties throughout the Empire. The most severe atrocities occurred in Constantinople, in what became known as the Constantinople Massacre of 1821. By the late 19th and early 20th century, the Greek element was found predominantly in Constantinople and Smyrna, along the Black Sea coast (the Pontic Greeks) and the Aegean coast, the Gallipoli peninsula and a few cities and numerous villages in the central Anatolian interior (the Cappadocian Greeks). The Greeks of Constantinople constituted the largest Greek urban population in the Eastern Mediterranean.The Greek population amounted to 1,777,146 (16.42% of population during 1910). In the first half of 1914, the Ottoman authorities expelled more than 100,000 Ottoman Greeks to Greece. During World War I and its aftermath (1914–1923), the government of the Ottoman Empire and subsequently the Turkish National Movement, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, instigated a violent campaign against the Greek population of the Empire. The campaign included massacres, forced deportations involving death marches, and summary expulsions. According to various sources, several hundreds of thousand Ottoman Greeks died during this period. After the Greco-Turkish War, a population exchange between the two countries was agreed. Due to the Greeks' strong emotional attachment to their first capital as well as the importance of the Ecumenical Patriarchate for Greek and worldwide Orthodoxy, the Greek population of Constantinople was specifically exempted and allowed to stay in place. In 1923, the Ministry of Public Works asked from private companies to fire non-Muslim workers. In 1934, many minorities including the Greeks were forced to adopt last names of a more Turkish rendition. In 1936, Turkish became the teaching language in Greek schools. In 6–7 September 1955 an anti-Greek pogrom was orchestrated in Istanbul by the Turkish military. The pogrom greatly accelerated emigration of ethnic Greeks from Turkey, and the Istanbul region in particular. The Greek population of Turkey declined from 119,822 persons in 1927, to about 7,000 by 1978. In 1964 the Turkish government took actions against the Greek minority that resulted in massive expulsions and Greeks were banned from participating in 30 professions. Greek-owned shops were forcefully shut down. More Greeks were deported. In the late 60s, the Turkish authorities built open prisons for Turkish convicts in Turkey's islands Imbros and Tenedos, which however were Greek populated, forcing many of the Greeks living there to also leave. On 15 August 2010, a ritual was held for the Assumption of Mary at the Sumela Monastery, built in 386 AD, after an 88 years old ban. This annual ritual continues, although it often sparks debate in Turkey for “keeping foreign traditions alive on the day Trabzon was captured by the Turks.” Get it? The "foreign" traditions were the ones taking place there since 386 AD.

To summarize, before World War I, there were still an estimated 1.8 million Greeks living in the Ottoman Empire with Constantinople being the most populous Greek center in the the Mediterranean. The 2008 figures released by the Turkish Foreign Ministry places the current number of Turkish citizens of Greek descent at the 3,000–4,000 mark. As of 2023, according to The Economist, "Turkey's Greek community is being revived"... whatever that means.

Graduates and Teacher of the Evangelical School of Izmir (Smyrna), 1878. (Not to be confused with the Evangelical dogma.)

#greece#greeks#greek people#minorities#greek diaspora#eastern europe#north africa#middle east#greek history#anon#ask

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi

1 love your blog and podcast

2 I’m really enjoying your weekly Palestinian film recs

3. Do you have more recommendations for Arab and Middle Eastern cinema ?

Thank you ☺️

helloooooo, thank you 🥰 I have a whole sideblog which I don't promote enough called @swanasource where I and my co-mod @thatidomagirl frequently post middle eastern/SWANA film and films made by swana filmmakers in the film tag here:

I myself am still on my journey of watching more swana films (and non-english and non-Western films) so I won't claim to be any sort of exhaustive expert. but here are some of my favourites!

Salt of this Sea (2008). Dir. Annemarie Jacir. Palestinian film about a Palestinian-American woman heisting an Israeli bank

The Persian Version (2023). Dir. Maryam Kershavez. Comedy about an Iranian-American lesbian who gets pregnant after a one night stand and so decides to learn more about her family history.

Kedi (2016). A calming and beautiful Turkish documentary about the cats of Istanbul

Ali's Wedding (2017). A rom-com about an Iraqi-Australian Muslim who falls in love with the Lebanese girl from his mosque who's helping him get into med school.

The Man Who Sold His Skin (2020). Tunisian thriller about a syrian refugee who agrees to let his back be tattooed and be part of a living exhibition by a notorious artist so he can get a visa.

Sirens (2020). A documentary about the queer Lebanese all-girl metal band, Slave To Sirens, set around the Beirut explosion.

In Vitro (2019). A short Palestinian sci-fi film about an elderly woman in an underground bunker trying to describe the world before to a young woman who's only ever known the bunker.

Cairo Time (2009). Dir. Ruba Nadda. Look, this film isn't perfect but It's about a white American woman who's husband is a UN worker in Egypt. She goes to visit him in Cairo, but her husband is waylaid so he sends his bestie played by the beautiful Alexander Siddig to take her around Cairo and oh my GOD the romantic tension of this movie keeps me up at night.

Butterflies (2018). One of my fave movies ever. A Turkish comedy about 3 estranged siblings who have to take a chaotic road trip to fulfil their father's last wishes.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Dune Part 2

All right, friends. Dune Part 2. I absolutely picked the wrong time to start wanting to return to Tumblr, since I'm currently in the thick of Ramadan, but c'est la vie. I'm a bit worried that if I don't review now that I might forget my specific impressions of the movie, though I have to say that if this weren't Ramadan that I absolutely would be going back to see it again in the cinema, which says a lot considering that it's been at least ten years since I've actually wanted to go back and repeat a film instead of just waiting for it to come out on streaming/DVD.

So the movie is good. It is in fact very, very good. It's the Empire Strikes Back of the Dune duology (possibly trilogy), and (much like Empire) in terms of cinematography, music, scripting and acting it's nearly flawless. There are, however, issues, things that might not occur to a majority-Western audience but which are immediately clear to anyone who either comes from an Arab or Muslim background.

What follows here is a deep dive into some of the historical and cultural sources of Dune and some of the ways in which the movie producers, and in some cases fans, have failed to acknowledge those sources.

First of all, it's obvious that the Fremen are meant to be based on the Arabs, but of the the entire main cast there is only ONE actor with an Arab background, and that is Souhaila Yacoub, the half-Tunisian actress who plays Shishakli, the female Fremen warrior who is executed by the Harkonnens. Now, I have to say that this woman was fantastic. Her attitude is completely on point for an Arab, especially a North African Arab: forceful, loud, a bit brash and mocking even under fire. Nicely done. Points to the producers there, but I have to take that point away again because she is literally the only Space Arab who is actually Arab. Javier Bardem, the Spanish actor who plays Stilgard, does have some interesting moments and one of the reasons why I feel that the screenwriters were advised on Arabic traditions/culture. The incident during which he warns Paul about the Jinn in the desert like it's a joke but then immediately turns extremely serious when Paul starts smiling is so in character for an Arab and honestly just a brilliant bit of scripting, but much of the time he also acted more or less like what people *think* a fanatical religious Arab acts like--loud, frantic and unstable.

Not only this, but the "Muslim" behaviour/traditions in the film are at best...vague. People are praying, but in any direction at all. I do realize that this would be a complicated issue on another planet, where the Ka'aba couldn't be pointed to, but there are Islamic rulings for EVERYTHING. Check out the one about praying in space:

Even if they had as a society simply picked a random direction for prayer, they should all be praying at the same time and in the same direction (they seem to do this in larger crowds, but not in the smaller group where we first see people praying). They also definitely shouldn't be talking during prayer or trying to make other people talk to them during prayer (as Chani does), since talking breaks your prayer and you have to start over all over again (during obligatory prayers).

Language, too, is an issue, and a big one, because while I do understand that a conlang was developed for use in this movie, the linguists consulted did know that the language was meant to be heavily influenced by Arabic. Consequently, they've included a lot of fragmentary Arabic in their work. Unfortunately this Arabic is poorly pronounced at best, to the point where I was looking words up and laughing at what they're meant to be based on. For example, "Shai Hulud," the word for the Worms, is based on the Arabicشيء خلود, which means "immortal thing," and should be pronounced with "shai" rhyming with "say" followed by a glottal stop, and the 'h' in "Hulood" is actually a guttural sound like the infamous "ch" in Bach, followed by a long U. Another example is Mua'dib مهذب , a real word in Arabic that means "teacher," but is is actually pronounced with a "th" sound instead of a d and emphasis on the second syllable, not on the last as in French. (Note: I made an error here. There is a word مؤدب , pronounced mostly the same in the movie, but with a glottal stop after the 'u' sound and a short 'i' after the d sound rather than a long vowel, that is usually used to mean polite, urbane, gentlemanly, etc. but which can also mean teacher, although I have never heard it used in this context) "Usul", أصول, Paul's other Fremen name, was likely not, as I had previously guessed, based on the word "Rasool," meaning Prophet, but on أصول الفقه the Principles of islamic Jurisprudence, which also ties directly into a religious/prophetic them. Again, this is pronounced on the long vowel, so with a short first U and a long second U.

I've included the Arabic spellings in here, by the way, so that you can drop them into Google translator and hear how they actually sound.

Now, I do realize that the story itself is set 8000 years in the future and that spoken Arabic as a language would have changed considerably in that time, if it existed still at all, but Arabic is a liturgical language as well as a vehicle for conversation, and Muslims all across the world today use it as a tool for worship. Muslims who have no cultural connection with Arabic often still learn it in order to connect more deeply with religious traditions and simply to perform prayers and other religious duties. Religious scholars consider it to be a necessary duty of the Muslim to learn at least some Arabic:

And keep in mind that the Arabic spoken today across the MENA region is very different (and different in different places) to the Arabic spoken 1400 years ago by the Prophet Mohamed (peace be upon him). Given Islamic traditions, the chances of the Fremen using liturgical/classical Arabic for their worship would be quite high, even if their spoken language had evolved past the point of being recognizably Arabic.

Keep in mind, also, that Dune as a whole is an allegory for colonialism, economic exploitation of poorer nations (or making rival nations poor through the same), as well as dehumanization of the views and needs of native peoples in order to make that exploitation palatable to the occupying forces (I thought that this was done quite smartly in Jessica's part of the story; although she is sympathetic to the Fremen, she feels that manipulating their religious traditions is the best way to protect her son, and in doing so she allows herself to dehumanize the people who come to rely on her).

It is, therefore, incumbent upon us not to distance ourselves too much from the intended message by claiming that Dune is fiction and need not too accurately reflect the culture and religion of the people that the Fremen are so clearly based on. The fact that the producers have done little to hire Arab actors or induced any real effort to accurately pronounce the Arabic words or accurately portrayal Islamic practices seems to indicate that they are concerned about identifying too closely with the economic and cultural struggle between East and West, properly because they fear the potential economic backlash, and this despite the fact that Frank Herbert clearly wrote his book to illustrate the fallout of that struggle.

Here is a wonderful article written by a culturally Arab woman:

There are numerous other articles addressing the same issues, but I like this one because it's written by a Muslim woman, who also addresses the "hijab cosplaying" in the movie. I didn't get into that much, but I definitely recognize that it's a problem when Muslim women worry about potential violence while wearing hijab in the streets of Western nations, but the same article of clothing is fetishized in movies and fashion.

I've also seen some comment about the Mahdi mention in particular. This is a saviour-figure in Islam who will come near the end of the world. There is no emphasis on this figure in Sunni Islam, but Shias seem to have a significant body of literature concerning this figure and, from what I understand, believe that he may perhaps have already come, and so there has been some poor reception in that community to applying the label of Mahdi to Paul. Criticisms ranging from insensitivity to outright blasphemy have been levelled regarding this usage. Now, there was some tip-toeing around the prophetic theme in Dune, and rightly so, I believe, since the Prophet Mohamed is the "seal of the prophets" in Islam, meaning the last and final. The fact that Paul was essentially set up as a false prophet by the Bene Gesserit does avoid some of the potential fallout from this, and also makes sense of Chani's rejection at the end of the film, since she felt strongly about Paul acting as a false Prophet.

Again, I am aware that there is internal cosmology within the series itself, and that some fans object to the religion of the Fremen being referred to as Islam, but when the inspiration for the entire ethnicity, religion, and the natural resources at stake are as clear as they are in this series, it's also futile to expect that people will not draw those associations, nor that people belonging to the religion or ethnic group in question may not acknowledge the beauty of the movie, the gorgeous cinematography, rousing music, and tightly plotted story, but still take exception to what is clearly Orientalism.

And it is frankly such a shame that we have to place this movie under that header, because the story of Dune is so sympathetic to the Middle East and its peoples, and as I said in the beginning I actually loved the film and found it very beautiful. It was also exciting to see Islamic themes used creatively in mainstream media, but while Frank Herbert clearly wrote the story as an exposition on the exploitation of natural resources, particularly oil, in the MENA region, the truth is that the racism and exploitation that he was protesting are very much alive today and contribute to the oppression of millions. It's particularly disappointing to see the message of the movie sail over the heads of people watching it when Arab Muslims in Palestine are being dehumanized and obliterated at this very moment, and while Libya was one of the latest Arab nations to be targeted for its oil resources, only a decade ago, with European oil companies moving in directly after the downfall of Ghadafi (which makes the timing extremely suspicious, one might say):

And even after the US finished their occupation of Iraq, Western oil companies remained en mass to continued drilling:

Egypt to this day remains economically destabilized while Western nations exploit its oil stocks, to no benefit at all of its peoples:

I'm sure I could cite dozens of other cases, but it's clear that there is a one-on-one parallel between spice melange and oil, making any protests of apoliticism in an inherently political story utterly vain.

I could go on, but I needn't. In short, this beautiful movie could have done so much good even beyond its obvious artistic merits, but instead it is still towing the political line. Much as was the case for Jessica and Paul, sometimes you can be a Harkonnen and not know it.

#dune#dune part 2#meta#islam#arabic#history#orientalism#paul atreides#lady jessica#chani kynes#oil drilling#colonialism#arrakis#north africa#the middle east

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

La mort trouble (1970), dir. Férid Boughedir & Claude d’Anna

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Daughters (2023, Kaouther Ben Hania)

#four daughters#les filles d'olfa#kaouther ben hania#women directors#documentary#tunisian cinema#olfa hamrouni#post#screencaps

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my brother's best friend is a Tunisian lesbian, I met her ten years ago and she adored me, asked about me all the, and yesterday and today I got to meet her again and hang out with her and really talk with her, and she's just. Super fun. She's a cinema expert and fan, she's a photographer, she works in archeology, she's a metalhead, she's passionate about TV shows and she's from a city in Tunisia that I've always wanted to visit, and we get to talk Arabic languages, music and cultures together, something that she told me she can't do normally because she doesn't know a lot of Maghrebian people and... Yeah, she's very cool. Very, very cool.

#rapha rambles#this post doesn't really have a point i just wanted to sing w's praise because she's hella cool and i needed to say it somewhere#it's also because i miss hanging out with maghrebians - my latino friends are great and latin america has a lot in common with north africa#but it's not the same and i'm really glad i got to speak arabic for a couple of days and talk north africa music and archeology and cinema

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashkal (2022)

Does every criminal have a motive? A series of apparent self-immolations clustered around a derelict neighborhood in Tunis makes even more fraught a tinderbox of issues in a country trying to heal after its people worked to overthrow an autocratic regime. Are these deaths merely suicides? Or are they connected, the work of a terrorist bent on sowing chaos or an ideologue with an anti-police mentality? If the gears of justice move slowly, the mechanisms of police corruption are well oiled. Fatma’s quest for the truth is met with scorn and obstruction from her colleagues, and the police union is quick to use the situation and fear over anti-police mentalities to appeal for shuttering the investigation into their crimes and complicity in authoritarianism. Even aside from the human toll of these crimes, the situation makes for a difficult minefield which Fatma and her partner (much more reluctantly) must navigate. It certainly doesn’t help that our adversary is only ever glimpsed at a distance or framed anonymously. The only image of his face, strange and deformed with small eyes and an almost absent nose, is the product of Fatma’s description. When the camera captures him, he’s swathed in bandages or a hoody, only his scarred and burned hands visible. We are trapped in Fatma’s perception during her dogged pursuit, limited by it. To that end, the final confrontation between the two is more emotional than physical. There’s nothing Fatma can do but gaze at her quarry in the inferno and weep in frustration. There is no release when various factions keep stoking the flames, and this mysterious figure is the avatar of that disarray.

The Gardens of Carthage itself reflects the decay of this situation. Construction which was initiated during the regime promptly ended with only very slow progress made in the ensuing years. The result is a strange, apocalyptic landscape of blank floors and open windows, walls opening up to nothing but empty air. People aren’t sure how to move forward, leaving behind ruin and disrepair. The camera at points lingers on austere compositions of steel and concrete accompanied by orchestral cluster chords. It manages to find a sort of elegance in the ugliness, even if it is marred by the proceedings of the film itself. Though the implications are terrible, the film manages to find a sort of strange beauty too in the orange glow of flames slowly overtaking a car in the distance or a man in a high-rise window. The closing moments show a score of people giving into the seduction of the fire, and yet Fatma alone seems able to resist that siren song, not participating in the collective madness.

THE RULES

SIP

Someone says 'immolation' or 'Commission'.

A construction crane appears in a scene.

Ashes are found.

Someone watches an Internet video.

BIG DRINK

Someone stands or sits at the edge of an unfinished building.

The shot looks straight down from above.

#drinking games#ashkal#the tunisian investigation#youssef chebbi#fatma oussaifi#crime#horror#horror & thriller#tunisian cinema

1 note

·

View note

Text

Remembering Yasser Jradi: A Tunisian Artist, Activist, and Revolutionary

Today, we gather to mourn the loss and celebrate the life of Yasser Jradi, a true Renaissance man of Tunisia. As an artist, activist, and revolutionary, Yasser touched countless lives and left an indelible mark on Tunisia’s cultural and political landscape. Yasser was not just an artist; he was art personified. A master of calligraphy, ceramics, photography, cinema, and music, he poured his soul…

0 notes

Text

Haydée Chikly Tamzali was a Tunisian-Jewish actress, writer, and filmmaker who played an essential role in the development of Arabic and African cinema.

Chikly began working with her father as a young girl. When she was 16, he directed her in her first starring role in the short film Zohra (1922), which was written by Chikly herself and is considered the first fiction film made in Tunisia. She served as her father's muse and was able to participate in various aspects of filmmaking, including film editing and hand-coloring.

📷 Tunisian actress, writer, and filmmaker Haydée Samama Chikly Tamzali, 1922.

0 notes

Text

MARRAKECH — Nabil Ayouch is Morocco’s best-known filmmaker, having directed international hits such as “Ali Zaoua: Prince of the Streets” (2000), “Whatever Lola Wants” (2007), “Horses of God” (2012).

Over recent years he has played a key role in developing the nascent Moroccan film industry including the production of a slate of over 40 Moroccan telefilms, for public broadcaster SNRT, which launched a new generation of directing and acting talent.

His 2012 pic, “Horses of God,” about the 2003 Casablanca suicide bombers, was sold to 40 countries by Wild Bunch and officially presented in the U.S. by Jonathan Demme, where it was Morocco’s candidate for the foreign-language Academy Award.

However, in 2015 Ayouch became a bête noire for certain quarters of Moroccan society due to his prostitution drama, “Much Loved,” which was banned one week after the film bowed in Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, on account of “serious outrage to the moral values of Moroccan women.” Private court proceedings were also filed against Ayouch.

Ayouch and his main actresses were fervently attacked in the media; the lead actress was assaulted in the street, leading her to move to Paris. Critics of “Much Loved” dubbed him as a foreigner who is undermining national cultural values. Ayouch was born in Paris to a French Jewish mother, of Tunisian descent, and a Moroccan Muslim father, born in Fez, and he has lived in Morocco since the early 1990s.

He is currently completing shooting on his next project “Razzia” which was initially conceived as a sci-fi project about the gulf between the rich and poor.

Ayouch received a $500,000 grant from the Moroccan Cinema Center (CCM) for this original version, penned by “Horses”’ scribe Jamal Belmahi, but as a result of the experience from “Much Loved” he decided to radically alter it and focus primarily on the human drama of the main characters.

He therefore turned down the initial grant and re-applied for CCM funding but was unsuccessful, which forced him to finance the film entirely as an international co-production.

The new script is written by Nabil Ayouch and Maryam Touzani and stars Maryam Touzani, Belgium’s Ariel Worthalter, Abdelilah Rachid, Dounia Binebine and Amine Ennaji.

It is produced by Bruno Nahon Paris-based Unité de Production, and is co-produced by iAyouch’s Casablanca-based production house, Ali’N Productions, Les Films du Nouveau Monde, France 3 Cinéma, and Belgium’s Artemis Productions.

It has also received funding from Eurimages, the Wallonia-Brussels Federation’s Film Centre, Belgian tax rebates and SofitvCiné 4, and has been pre-sold to Canal Plus, OCS, RTBF, BeTV and Voo.

Lensed in Casablanca, Ouarzazate and the Atlas mountains, “Razzia” depicts five separate stories, one set in the 1980s in the Atlas mountains and the others in present day Casablanca.

One of the recurring themes in the film is a reference to the 1942 classic “Casablanca,” starring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, which is ironically one of Morocco’s best-known symbols, even though it was shot entirely in Hollwood during WWII.

“In both films, people are fighting against an ideology,” says Ayouch. “They’re fighting against the Nazis in ‘Casablanca’ and in my film they are also trying to resist. The analogy is very clear.”

One of the key themes that links together the five stories is intolerance, ignorance of others and the refusal to accept differences, which Ayouch views as a growing sentiment in Morocco.

“The film is about people in search of freedom, and the right to speak their minds, act freely, and talk about the issues that matter to them. In particular the right of women to achieve this – since I think it’s getting more and more difficult for women to be free in modern Morocco.”

The social issues contained in the earlier versions of the project are still very present, but it is less about the gulf between rich and poor and more about issues of freedom of speech, that affect all tiers of Moroccan society, and the tendency for one section of society to feel contempt for another and become increasingly less tolerant.

“These are dangerous times throughout the world,” says Ayouch. “We have seen this with the election of Donald Trump in the U.S. and the rise of the far right in Hungary, Austria and France. Demagogy is leading in a new way, and there’s a new form of cultural hegemony – we’re seeing similar trends in the Arab world.”

Ayouch conceives the film, in part, as a tribute to the city of “Casablanca,” and explores the links with the no man’s land depicted in Michael Curtiz’s 1942 classic pic.

“My film will be a tribute but also a way of taking back what is ours,” says the director. “Casablanca was shot completely in L.A. and shows nothing of the true city, but even some locals in Casablanca are convinced that their streets hosted the original production.”

The pic includes images from the 1942 film and its soundtrack includes the iconic song, “As Times Go By.” One of the characters is convinced that the Bogart tearjerker was shot in his neighborhood when he was a young man. Alongside the references to “Casablanca,” other cult references that feature in the film include the pop group “Queen” and the late Freddy Mercury who personified the spirit of freedom that Ayouch wants to explore in the film. The soundtrack includes “We are the Champions,” “The Show Must Go On,” and “I Want to Break Free.”

The zones of modern-day Casablanca depicted in the film include the old medina and poor neighborhoods, where two of the characters live, walled condominiums in the “rich ghettoes” and also Casablanca’s famous art deco buildings. Ayouch considers that the city’s art deco architecture is part of the appeal of the 1942 pic and he wanted to bring the real Casablanca into homes around the world.

“Like millions of people, I really love this movie. A few years ago, I met a producer in New York who asked me how come this city was so famous around the world and yet no scene was shot in Morocco. He asked me whether it made me nervous. At the time I said “no.” But over time I realized that it did bother me. Even Moroccan people believe that it was shot here.”

Ayouch suddenly realized that this paradoxical situation was an excellent metaphor for what he views as the split personality of modern Moroccans and decided to create a character who believed that it was shot there. Another key character is a woman in quest for freedom. Society doesn’t let her life the way she wants to, so she moves and starts a new life, far from her husband. Another character, Hakim, is a carpenter living in a poor area, who is looked down upon by his father, dreams of becoming a musician and worships Freddy Mercury.

The present-day characters are all linked to a teacher who worked in a little school in an isolated Berber village, in the Atlas mountains, in 1982.

Ayouch says he was a man full of dreams who wanted to transmit his vision to children, to make them better people, and is able to do so until the authorities stop him, by means of the educational reforms introduced in 1982.

“I believe that there was a crucial change in mindsets in the early 1980s which changed education systems throughout the world and has had a major impact on the world of today,” said Ayouch. He added: “The education system turned its back on the humanities. This happened throughout the Maghreb region. In Morocco disciplines such as sociology and philosophy were taken off the curriculum. We’re now reaping the consequences. We’re building a new kind of human being.”

Ayouch considers that the defeat of the teacher in his film symbolizes the defeat of the entire society and he tries to trace a spiritual link to the other characters. He admits that this focus on the inner world of the characters and the way that society can crush people’s dreams was deeply affected by his experience with “Much Loved.”

“What happened to me after ‘Much Loved’ and to the actresses was a very strong experience. It really left a great impact. I will never forget the words I heard. Things I never thought I would hear. Such bad things. I never thought that this kind of split personality was so strong. That people could confuse fiction with reality and attack a director because he makes a film.”

Ayouch believes that there is a long-term evolution of mindsets which is engendering mistrust, intolerance and hatred.

He said that he admires how directors such as the Coen brothers or David Cronenberg show how oppressive forces can develop very slowly and then suddenly explode into violence.

He hopes to be able to complete “Razzia” in time for Cannes 2017 and thinks that it will be an important opportunity to focus on how mentalities are changing not only in Morocco but throughout the world.

“Mentalities are regressing for a simple reason,” he says. “Freedom of speech. We are moving backwards. What we have seen over the past two-to-three years, not only in Morocco but throughout the world, is a big step backwards.”

“Moroccan cinema has recorded major developments over the last decade, but they will all be worthless unless we defend freedom of speech. Funding for films in Morocco is now more about censorship than the films themselves. We can become one of the strongest film industries in the region, but we can also become very weak. I meet a lot of young directors who are all saying the same.”

Ayouch would also like to see greater solidarity between directors because he says that many complain but remain silent and cites the fact that for “Much Loved” over 80 major directors signed a petition in his support but few Moroccan directors defended him publicly.

Nonetheless, he maintains his own fighting spirit: “The day I feel I will be affected and refrain from speaking about what haunts and inspires me, I will stop. I will quit. I will make my films somewhere else.”

“Razzia” will be completed in early 2017. Ad Vitam will distribute the film in France and Films Distribution will handle international sales.

0 notes