#transalpina

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Transalpina, Rumänien, 24.08.2024

#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#monochrome#black and white#original photography#romanin rhapsody#transalpina#landscape

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transalpina Romania dragos_cimpoiasu

#Transalpina#Romania#dragos_cimpoiasu#europe#europe_gallery#europe_pics#europe_vacations#nature photography#europe_perfection#europe_photogroup#nature#nature_captures#nature_cuties#nature_hub#nature_good#nature_sultans#europe_moments#europe_greatshots#nature_brilliance#nature_lovers#nature_skyshotz

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transilvania roadtrip 2023 teaser :)

#motorcycle road trips#badtolka#motorcyclelife#adventure riding#f800gs#ktm adventure#trans european trail#moto adventure#adventure#transalpina#romania

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Circulația pe Transalpina, sectorul Rânca – Curpăt, a fost închisă din cauza ninsorii

Circulația rutieră pe Transalpina a fost suspendată pe segmentul dintre Rânca (județul Gorj) și Curpăt (județul Alba), începând de luni, 11 noiembrie 2024, din cauza ninsorilor abundente. Compania Națională de Administrare a Infrastructurii Rutiere (CNAIR) a emis un comunicat prin care informează că traficul pe acest sector montan, între km 34+800 și km 79+200 de pe DN 67C, va rămâne închis până…

#amenzi#anvelope de iarna#avertizare CNAIR#circulație rutieră închisă#CNAIR warning#cod galben Tags in English: Transalpina#condiții meteo#driver penalties#echipare vehicule#fines#Rânca-Curpăt section#road closure#sancțiuni șoferi#sector Rânca-Curpăt#Transalpina#vehicle equipment#weather conditions#winter tires#yellow weather warning

0 notes

Text

https://romaniasweetromania.com/2022/03/ziua-olteniei-oltenia-day/

#Ada Kaleh#Aleea Scaunelor#Brancusi#Calusul#Ceramica de Horezu#Coloana Infinitului#Cozia#craiova#cule#Dansul Calusului#Decebal#Drumul Regelui#Horezu#Masa Tacerii#Mica Valahie#Oltenia#Poarta sarutului#Portile de Fier#Tg Jiu#Tismana#Transalpina#tudor vladimirescu#Valcea#romania#visit romania#eastern europe#magic romania#beautiful romania

1 note

·

View note

Text

Transalpina, Sebeș, Romania

Taken by Calin Stan

0 notes

Text

Romania (2) (3) (4) by Emily Rae

Via Flickr:

(1) View of the town of Rânca. (2) (3) (4) Transalpina Highway

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dont tell Elon Musk about Transalpina and Cisalpina. Also dont tell him about Latin

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

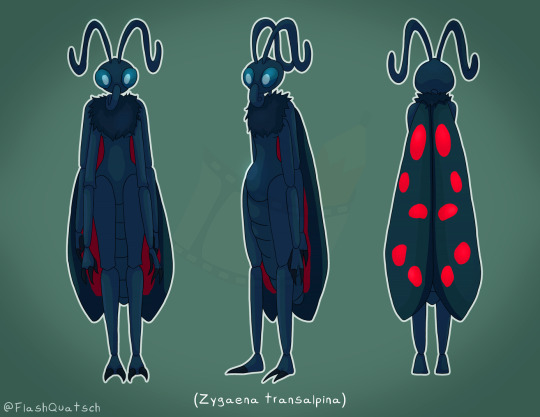

Character Design - Zygaena transalpina

New character design, I haven't picked a name for him yet 🤔 Suggestions?

Buy me a Ko-fi ^^ https://ko-fi.com/flashquatsch Support me on Patreon https://patreon.com/FlashQuatsch My Linktree https://linktr.ee/flashquatsch

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

✈️ 🩷

✈️ favourite place you’ve traveled?

i really like northern ireland, even though it's not very far away. other than that, romania! we went on the transalpina mountain road (i think) and it was lovely! there's also this one castle, boldogkő, in hngary that i adore, they have it all set up and furnished as it would have been when it was in use, and there's a really good medieval restaurant in the cliff underneath the castle

🩷 dream job?

ooh i have no idea. acting in doctor who, probably XD but also writing, photography (especially old buildings) or working with horses

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transalpina, Rumänien, 24.08.2024

#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#monochrome#black and white#original photography#romanian rhapsody

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Props to learning Roman history in elementary school telling me about gallia cisalpina and gallia transalpina meaning this or that side of the Alps. it makes the demonisation of prefixes like cis and trans very dumb because they clearly don't understand the meaning of words.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A car to match where you're sleeping / Transalpina / Aug '23

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantastic paragraph.

Trans and cis are also literally latin words.

Hello.

Cis- means "over here" trans- means "over there". What today is nothern italy used to be called "Gallia Cisalpina". What today is france was "Gallia Transalpina". Before the mountains/over the mountains.

I know that arguing with fascists about words and shit means nothing. But this is not for them, this is some fun little trivia for my over the mountains tumblr girlies 💜

45K notes

·

View notes

Text

Se deschid Transfăgărășanul și Transalpina! Trafic permis doar pe timp de zi, cu restricții stricte

Începând de vineri, 6 iunie, două dintre cele mai spectaculoase șosele montane ale României — Transfăgărășanul și Transalpina — se redeschid circulației rutiere, după perioada de iarnă. Traficul va fi însă permis doar pe timpul zilei și în condiții stricte de siguranță. În plin debut de sezon turistic, autoritățile au anunțat redeschiderea circulației pe cele două drumuri alpine de mare…

0 notes