#tooth taxon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

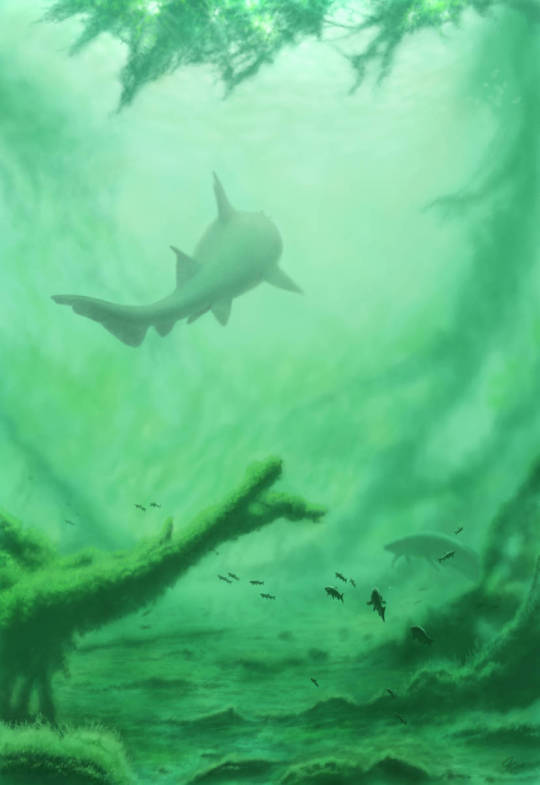

Another sketch brought to you by #paleostream

Rolfodon is a giant relative of the modern frilled shark, large enough to eat small or juvenile mosasaurs.

344 notes

·

View notes

Text

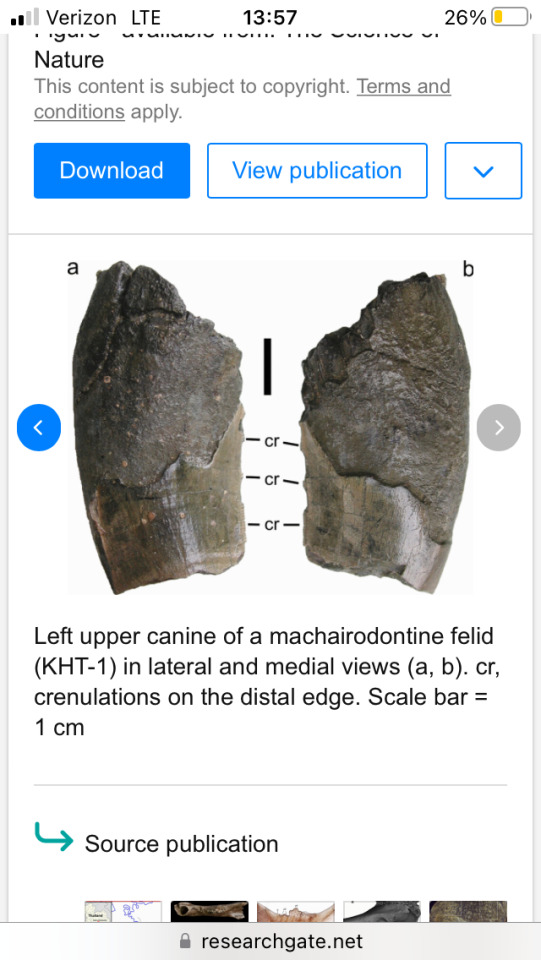

shaking and crying and screaming because all we have of the sabercat who lived alongside pachypanthera is one(1) broken tooth so we can’t know what she was….

who are you what is your story

#looks like a more basal taxon imo#machairodus or dinofelis?#tooth isn’t particularly thin laterally from what i can tell (these photos dont show the lateral width clearly tho sadly)#but overall me and my paleo major buddy both agree this is more of a basal puncturing tooth and less of a derived stabbing tooth#this is from thailand btw if anyone knows of any machairodont genera that have been confirmed in southeast asia lmk

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A partial dinosaur tooth of an indeterminate theropod from an unknown locale. It was labeled as possibly from the Yixian Formation thus potentially Yutyrannus huali. However, the odd orange preservation does not match that of this deposit according to those familiar with the formation; I'm also not sure if that darkened spot was caused by fire damage. The distal serration density of 20-21/5mm seems a bit high for Yutyrannus based on what's described from Sinotyrannus which is around 15-16/5mm, and it's unclear whether the tooth has a mesial carinae. There is a possibility that it belongs to the Cretaceous carcharodontosaurian tooth taxon, Prodeinodon. A very unusual tooth, but unfortunately the dubious provenance makes identification extremely difficult if not impossible.

#dinosaur#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#yutyrannus#prodeinodon#proceratosauridae#tyrannosauridae#carcharodontosauridae#theropod#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#ユウティラヌス#プロデイノドン#プロケラトサウルス科#ティラノサウルス科#カルカロドントサウルス科#恐竜#化石#古生物学

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have a least favorite dinosaur?

Honestly not really

I guess a fragmentary tooth taxon but I wouldn't be able to name it off the top of my head

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

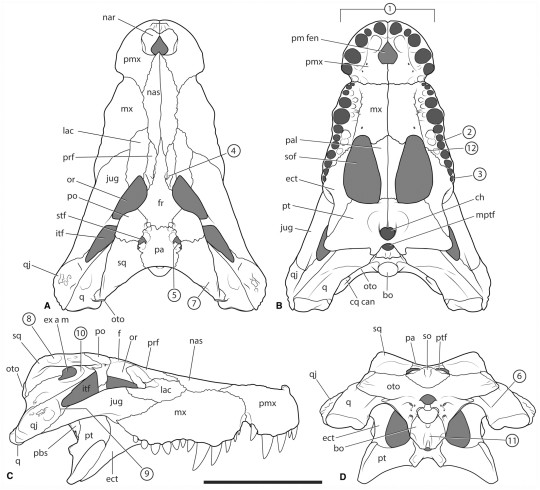

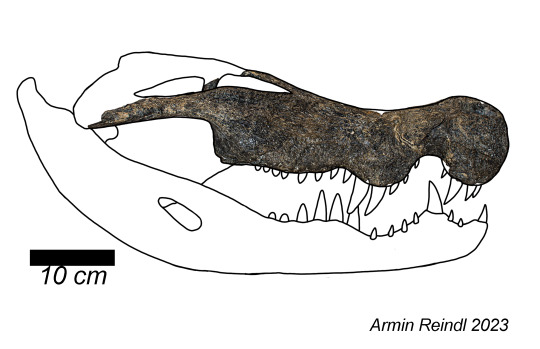

Baru iylwenpeny: The Last Baru

Happy to announce that there's just been a major new publication for mekosuchines. The Alcoota Baru, which I briefly touched upon in my post on the genus, has finally been named. The new name, Baru iylwenpeny (pronounced eel-OON-bin-yah), derives from the Eastern Anmatyerr dialect (part of the Arrernte language) and means "good at hunting". A name that seems quite fitting when you look at the skull.

As a reminder, this animal stems from the Alcoota Fossil Site in Australia and dates to the Late Miocene, making it the youngest of the three recognized Baru species.

Previously this species was already referred to as being "the most robust Baru" and they weren't kidding. This thing looks more like something out of the Cretaceous than an animal that lived a mere 8 million years ago.

The morphology is interesting in many ways. Many of the ridges that are so prominent in Baru wickeni and less developed in Baru darrowi are absent. The seventh and eight tooth are so close they theres basically no space. Instead of four teeth like other Baru it has five in each premaxilla and the nasals reach the nares, like in Baru wickeni but unlike in Baru darrowi. The teeth also show the same small serrations as Baru darrowi and, unlike either of the other species, the jaws appear much less wavy not because they are but because the first festoon of the maxilla is followed up by a second one so developed it makes the first look almost flat. It's a fascinating mosaic of characters that makes its relation to the other species a puzzling question. You'd think that the ridges for instance point at it being derived? After all wouldn't it make sense? Baru wickeni had the most developed rigdes, Baru darrowi smaller ones and Baru iylwenpeny none. Plus, the teeth of Baru wickeni are smooth unlike those of later forms. Yet at the same time.... The fact that it has five teeth instead of four and the fact that the nasals reach the nares are both ancestral traits, so you'd expect it to be closer to the base.

Left: Baru wickeni Right: Baru darrowi

Well, while I think this isn't going to be the final place of this species among Baru, the most recent phylogenetic analysis suggests that Baru iylwenpeny was weirdly enough the basalmost species. Which means that it must have split from the other two species at the latest during the Late Oligocene and outlived the both of them without us ever knowing.

The paper also discusses how these animals may have gone extinct. If you look back at Kalthifrons, you might remember how I mentioned that mekosuchines kinda had a drop in diversity when transitioning from the Miocene to Pliocene. While the new paper avoids calling this a drop in diversity, it does highlight that there certainly was a turnover in fauna. The reason is an old enemy of mekosuchines. Climate. Yates and colleagues suggest that Australia was hit by an especially nasty dry period at the end of the Miocene, severe enough to drive Baru to its death but not severe enough to whipe out all mekosuchines. And after Baru was gone, Kalthifrons and Paludirex moved into the open niche.

There's also a final little piece of information that's not focused on yet really fascinating. Baru iylwenpeny had a friend. At least one other croc lived at the Alcoota site during the Late Miocene and tho it hasn't been studied in full yet, one thing is apparently known. It was a relative to the Bullock Creek taxon that coexisted with Baru darrowi and a relative to "Baru" huberi, the small croc that coexisted with Baru wickeni. This grouping has yet to be given a name, but its fascinating to me that each Baru species seemingly coexisted with a much smaller mekosuchine. Alas, like Baru this lineage seems to have fallen victim to climate change.

Baru wickeni and "Baru" huberi, in truth an unnamed genus.

The paper is accessible here for those that wan't to dive deeper into the matter. I'll also be working on an updated size chart, this time featuring all three species of Baru, tho I can already tell you that despite being more robust its surprisingly not that much larger.

The last Baru (Crocodylia, Mekosuchinae): a new species of ‘cleaver‐headed crocodile’ from central Australia and the turnover of crocodylians during the Late Miocene in Australia (wiley.com)

#baru#baru iylwenpeny#alcoota baru#alcoota fossil site#miocene#paleontology#palaeoblr#crocs#crocodile#mekosuchinae#paleontology news#prehistory

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no dinosaur named Troodon

Sunday 23/4/23

Alaskan Troodontid - Julio Lacerda @paleoart

A brief sorry for not writing for a while. Had a lot on my mind and also just struggled to get that jump-start on my creativity again. But after having a bit of nerd-out at a friend recently, I have a dinosaur related thing to talk about today.

For anyone knee-deep into dinosaur stuff, they'd know about the popular stereotyping around small meat eating dinosaurs. The likes of "Raptors" are often portrayed as problem solvers; coordinated, and clever. And although most modern birds have more developed brains than extinct non-bird dinosaurs, the exception of Troodon is often brought up.

Troodon - @/the_meep_lord on Twitter

Troodon is a name that dino-nerds will bring up as a notable example of smart dinosaurs. It was one of the dinosaurs most closely related to birds, it had large eyes for its head, and in fact the largest brain to body size ratio of any non-avian dinosaur. But what many dino-nerds might struggle with, is that most palaeontologists believe that the genus Troodon is not valid.

Now when I first heard this information, my reaction was likely the same to yours reader. What do mean the genus isn't valid? Ask anyone what Troodon looks like, we have a very clear picture. How can we have full skeletons of a dinosaur that didn't exist? How come we have a significant clade of dinosaurs named after it (Troodontidae)? It is a dinosaur that even had unfortunate older stereotypes in its design (pictured below: the olive green smooth skinned Troodon that inspired the ugly Dinosauroid speculative biology thing).

llustration of Troodon - De Agostini Library (unable to find artist)

The issue, as I'll try to explain, was an unfortunate game of guesswork and generalisation across the Palaeontological community.

Discovery and Naming

In 1855, a single fossil teeth was found in Montana, USA. This was a particularly jagged tooth, and seemed to belong to some form of carnivorous or at least omnivorous reptile. It was named Troodon formosus meaning "wounding tooth, well formed". This tooth was originally classified as belonging to a lizard, so the genus Troodon was born.

Troodon holotype drawing, 1860

In 1901, it was decided that Troodon's tooth belonged to a dinosaur, within the group Megalosauridae. But as I've discussed previously, Megalosaurus was a wastebasket taxon, and other experts wanted to place Troodon somewhere more definitive. In 1924, Troodon was classified as a relative of dome-headed dinosaurs such as Pachycephalosaurus and Stegoceras. And since Troodon pre-dated many dinosaurs in this group, the family was at the time referred to as Troodontidae.

"Sandy", Pachycephalosaurus specimen at Royal Ontario Museum

Troodon as a Pachycephalosaur lasted until 1945, when Troodon was finally reclassified as carnivorous dinosaur, and the dome-headed dinosaurs were renamed under the title Pachycephalosauridae.

Other Troodontids

For a long time, the issue with Troodon was that because it's teeth were one of a kind, they did not know how the rest of it's body looked. The first dinosaur to be classified under Troodontidae that wasn't named just for teeth was a dinosaur called Stenonychosaurus (meaning 'narrow claw lizard").

Stenonychosaurus, Nix Illustration @alphynix

The original specimen of Stenonychosaurus did not have teeth, but it's close relative Saurornithoides did. And once both specimens had more complete specimens collected, they were classified under the group Saurornithoididae in the 1980s. But soon, scientists found similarities between the teeth of Saurornithoididae dinosaurs, and that of Troodon. The Principle of Priority states that earlier names for taxon are more valid taxonomically, so Saurornithoididae was considered synonymous with Troodontidae, and all specimens previously referred to as Stenonychosaurus were now called Troodon.

"Troodon" Specimen, Perot Museum, Texas

Most of the facts we now think of as Troodon were originally attributed to Stenonychosaurus, and many other North American Troodontids were considered as possible synonyms of Troodon, but this received some push back.

The idea that most of North America's Troodontids all belonging to one taxa was questioned. So, as had happened to other wastebasket taxon prior, Troodon was reanalysed.

In the late 2000s, a Troodontid called Pectinodon was separated from the Troodon genus and considered its own taxon. In the mid-late 2010s, some material originally classified under Stenonychosaurus, and then Troodon, was given its own genus, Latenivenatrix.

Latenivenatrix sculpture, @bookrat

Was "Troodon" really Troodon?

So the question of "What is a Troodontid?" had a very clear answer now. They were small to medium Theropod dinosaurs with narrow skulls, front facing eyes, larger braincases, and often restored with sickleclaws and feathers, similar to the Dromeosaurs. But the question came back to the Genus Troodon itself. We had sufficient material of many other Troodontids to tell what most of their body looked like, but the "holotype" of Troodon was still just one tooth.

In case you need a refresher on the terminology, a holotype is the first fossil a new species is named for. For another fossil to be named the same species, it needs to be identified as similar enough to the holotype. Holotypes are often fragmentary, it is common practice to fill in the full skeleton with details from similar relatives, but you still need enough details to identify who your relatives are.

The holotype of Troodon was so fragmentary, (again one bone), that it has been referred to as undiagnostic. Terminology lesson again, that means you CANNOT tell what it belongs to.

The fragmentary Holotype of the more recent Troodontid "Talos sampsoni", was almost complete in comparison to Troodon's. Credit: Scott Hartman

The Troodon tooth was *similar* enough to Stenonychosaurus that they were proposed to be close relatives, but there were differences enough for there to be initial scepticism at their synonymy. The original explanation proposed that the Troodon tooth came from an individual who was older, or in a different part of the mouth to teeth found from Stenonychosaurus, but this was never scientifically scrutinised, just proposed. The whole absorbing of Stenonychosaurus into Troodon was based on heresy that had never been scientifically tested.

So in 2017, almost universally, it was decided that Stenonychosaurus be separated from Troodon as its own valid dinosaur. Almost all material that had at that point been assigned to Troodon were reassigned to Stenonychosaurus or Latenivenatrix. And now the genus Troodon had a problem. If all known fossil material came down to a single, very undiagnostic tooth, then what WAS this dinosaur actually like?

Stenonychosaurus - Anuperator (deviantart)

The current take is that there was no dinosaur known as Troodon in the technical sense. The tooth may not even belong to a Troodontid. But since Troodontidae has become an established group with established diagnostic traits, we still get to keep the name, for the group at least.

Troodontids Now

Troodontidae is still a very popular mainstream group of dinosaurs, but the names Stenonychosaurus, Saurornithoides, and Latenivenatrix are not as well known as Troodon. Many recent paleoart projects, particularly animations have depicted Troodon-like dinosaurs. But for scientific accuracy, they often decide to use the catch-all term "Troodontid", so audiences know what dinosaur we're talking about without being unscientific.

The YouTube Animation series "Dinosauria" features an episode on Arctic North American Dinosaurs. The main character is referred to as an Alaskan Troodon. This dinosaur has been originally proposed as a larger subspecies of Troodon described from larger teeth found in Alaska. As of writing, this Troodontid still does not an official description or scientific name.

youtube

In the 4th episode of the Apple TV+ series, Prehistoric Planet, we again see a dinosaur probably based on the Alaskan Troodon, this time just referred to as a "Troodontid".

youtube

In both pieces of media, the Troodontids engage in intelligent problem solving, but nothing on the level of what Jurassic Park would engage in. In Dinosauria, the Troodontid uses vocal mimicry. In Prehistoric Planet, it uses burning sticks to spread a wildfire. Both behaviours that different modern birds engage in, but may have been a stretch for what non-avian dinosaurs were capable of.

Thanks for Reading

If you are still a bit confused as to what this all meant, that's OK, it took me a while to get me head around it too. I encourage readers to do their own research and come to their own conclusion as to what this all means.

If you did feel my explanations helped you learn something new today, please reblog and spread the word. Of course add on your own commentary to the reblogs if you have insight that would better clarify the topic.

Thankyou for reading, and I'll hopefully have something else to post on here soon.

#blog#blogpost#palaeontology#dinosaurs#troodon#troodon formosus#stenonychosaurus#Latenivenatrix#Troodontidae#nomen dubium#theropod#Youtube#long post

84 notes

·

View notes

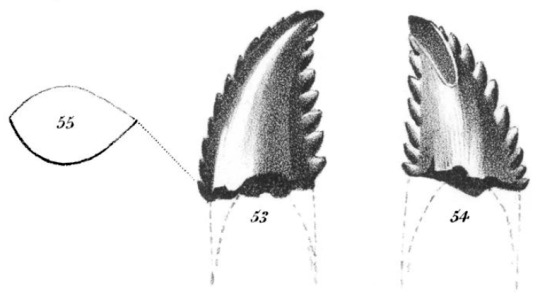

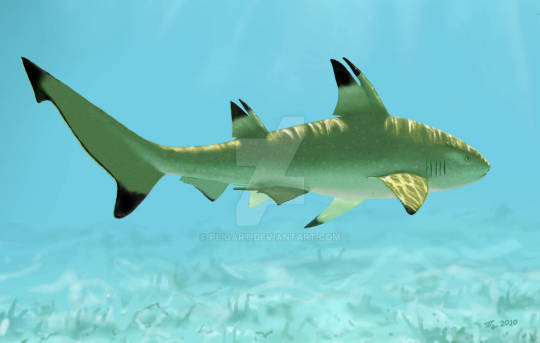

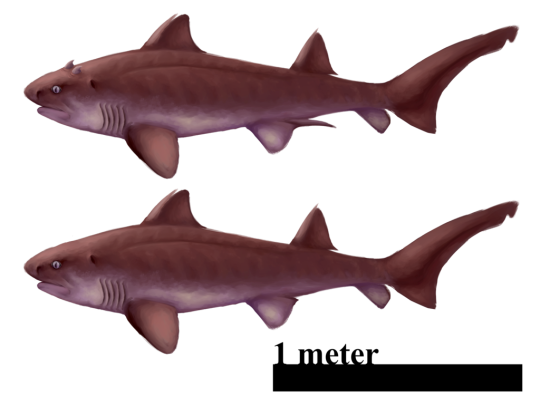

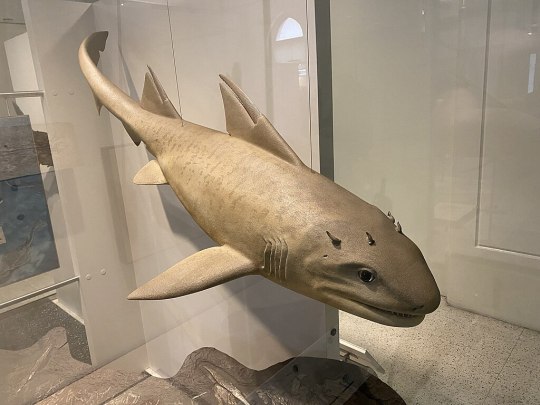

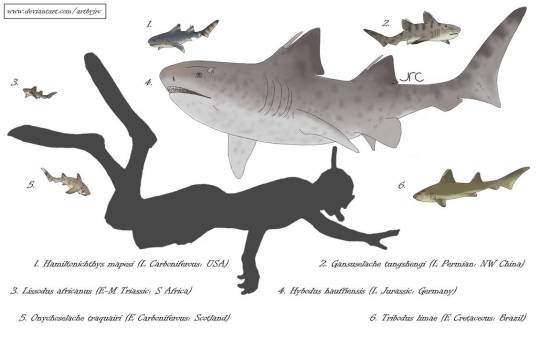

Text

Hybodus is an extinct genus of hybodont shark-like cartilaginous fish which lived throughout much of the world’s marine, brackish, and freshwater environments from the Late Permian Period to the Late Cretaceous Period some 259 to 66 million years ago. The first known remains of hybodus consisting of various isolated teeth where collected and formally described from throughout Europe by Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz in 1837 whilst he worked on his five volume series: Research on Fossil Fish. He dumped the creature Hybodus meaning crooked or humped tooth in ancient greek. In the following centuries several more remains would be unearthed including spines, jaws, vertebrae, and even whole specimens. Because of this numerous species have been assigned to Hybodus with varying degrees of analysis and evidence unfortunately leading hybodus to become a bit of a wastebasket taxon which is current undergoing a broad amount of reexamination. As such the exact species count is uncertain. Although first believed to merely be an extinct example of a living shark family, in 1911 Dr. Zittel showed them to be there own distinct lineage which along with modern sharks and rays make up the the clade Euselachii. Reaching around 6.6 to 9.8ft (2 to 3m) in length, It possessed a streamlined body shape similar to modern sharks, with two similarly sized dorsal fins that would have helped it steer with precision. These fins where also lined with dentinous spines which exhibit a rib-like ornamentation located towards the tip of the spine, with rows of hooked denticles present on the posterior side. The spines may have played a role in defending the animal from predators. Hybodus is also unique in that these fish sported multiple different kinds of teeth each distinctly shaped, it is thought that Hybodus' varied dentition would have allowed it to opportunistically exploit a variety of food sources; sharper teeth would have been used to catch slippery prey, while the flatter teeth probably helped them crush shelled creatures.

Art featured can be found at the following links

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Hokusai - Hokusai Manga Vol. 12, Men eating Noodles)

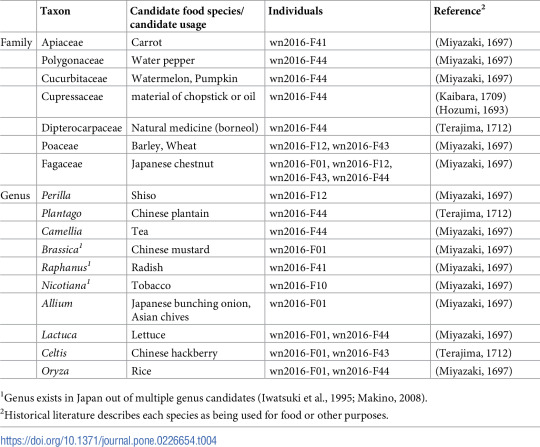

I recently came across the paper "Ancient DNA analysis of food remains in human dental calculus from the Edo period, Japan" by Sawafuji et al. (2020).

Researchers extracted DNA from dental calculus - that's the white stuff that forms on your teeth over time (and is generally removed if you go in for cleanings) - to study what people in the mid- to late-Edo period ate. To do this, they sampled calculus from 13 bodies dating to the 18th and 19th Century: 7 women and 6 men who lived in the city of Edo.

They found that they were unable to identify any type of animal taxon in the samples, so we don't know which fish or meats, if any, were eaten by the sampled individuals. So, not helpful in that regard.

However, they were able to identify the following:

We already know (and the paper points this out as well) that the diet of Edo's townspeople primarily consisted of rice and vegetables, occasionally (or regularly, depending on your means) accompanied by various types of fish.

From the list above, we can then identify a few more of the ingredients these specific people ate: rice, as their main staple, but also soba or udon (made from wheat and barley). An assortment of different vegetables, such as carrots, chestnuts, shiso, and garlic chives. And tea, naturally.

Interestingly, the researchers also found some non-food items, specifically plant matter from the Cupressacea (cypress) family, borneol and tobacco.

Tobacco is perhaps self-explanatory: many people in Edo smoked (pipes, specifically), and it would be fair to say that this left some residue in their dental calculus.

Plant matter from the cypress family is more interesting. There are two types of trees native to Japan from that family, the Japanese cedar and the Japanese arborvitae, the kind of smallish conifer that grows all over Japan. This plant matter is most likely to get into peoples' mouths by using chopsticks and toothpicks made from those trees, but also by using the resin as a painkiller for toothaches.

And the borneol stands out because it comes from a tree called the Borneo camphor, which isn't native to Japan and also won't grow in Japan if you tried. Meaning that the borneol would have to be imported, which it had been for a few hundred years, from China.

People examined in this study most likely came into contact with borneol as a flavoring in tooth powder. Tooth powder at the time was primarily fine sand with added flavoring to, I suppose, improve the experience and set apart different "brands" sold in stores.

You can learn more about tooth powders, tooth brushes, and treating toothaches in the Edo period on the website of the Kanagawa Prefectural Dental Association (in English).

Additionally, borneol was used in many traditional kampo medicines in both Japan and China. I'm not very well versed in kampo medicines, but according to this website, it's used to aid the digestive system by stimulating the production of gastric juices, treat bronchitis, coughs and colds, relieves pain and reduces swelling, and can be taken as a tonic to promote relaxation.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Compendium of Enantiornithean Late Cretaceous Jaws

Adamantina Formation enantiornithean jaw from Wu et al 2021.

I still remember the Mirarce paper and its authors’ decisions to depict the eponymous bird with a toothless beak. This decision was based on an assumption that, by the Late Cretaceous, most Enantiornithes had lost their teeth, concurrent with increased speciations towards powered flight and large sizes.

Yet, in recent years it has become increasingly clear that there was no “end goal” for the evolution of toothlessness in birds, with many taxa remaining toothed until the very end of the Mesozoic. Thus, no specific reason for the opposite birds to have lost their teeth.

Still, fact of the matter is that very few cranial remains identified as Enantiornithes date to the Late Cretaceous. While most sepcimens are predictably fragmentary, a few are almost complete, rendering this a frustrating puzzle. For example. Neuquenornis retains a fairly complete skeleton aside from the jaws, a skull well preserved aside from the front. Classic spiteful gods.

Hence, I’ve decided to make a small compendium of known enantiornithean jaw material from the Late Cretaceous.

Gobipteryx (and Gobipipus)

A menagerie of materials associated with embryonic Gobipteryx and Gobipipus, Chatterjee et al 2013.

For most of history the most well preserved Late Cretaceous enantiornithean material came from Asia. The taxa Gobipteryx occurs in Campanian-aged deposits of the Gobi Desert, and includes a myriad of exquisitely preserved material ranging from adults to embryonic remains. A lot of our understanding of the lifecycle of Enantiornithes in fact comes from these animals, hatchlings being supreprecocial and able to fly nigh immediately after birth.

Another more controversial taxon is Gobipipus, known from much the same deposits. Its known almost exclusively from embryonic specimens and several researchers have argued that it differs substantially from embryos assigned to Gobipteryx, but this debate is on-going.

Both birds lack teeth, instead having a keratinous beak whose upper jaw curves upwards. The bony components of the beak differ drastically from those of modern birds, with the maxilla being well developed and forming a large part of the upper jaw margin instead of being reduced as in modern birds, and it’s still unclear if it was capable of cranial kinesis like modern birds do. The ecology of these animals is also rather unclear; they come from what were in life arid environments, but some have suggested a piscivorous lifestyle for these birds, which would be in line wth some studies finding them closely related to the piscivorous longipterygids and��Halimornis (see supplementary material). Maybe some sort of seagull-like ecology, foraging in desert lakes?

Regardless, this painted a picture for Late Cretaceous Enantiornithes, and no doubt inspired the decision of the peeps on the Mirarce paper. Thankfully, other, more recent discoveries seem to be putting this to rest.

Adamantina Enantiornitheans

More material from Wu et al 2021

The Adamantina Formation dates to the Late Cretaceous, somewhere between the Campanian and the Maastrichtian depending on estimates. A partcular quarry, known as “William’s Quarry”, has wielded a massive amount of fairly well preserved enantiornithean fossils. These birds have not yet been described, but they are so complete that a study about their tooth replacement patterns was even possible.

Unlike the Mongolian birds, these ones clearly have teeth. Curiously, their snout shape is rather similar to that of modern raptors, the jaws ending on a hook. However, unlike contemporary birds like Ichthyornis, these hooks end not in a beak, but still host teeth, which is frankly amazing. I’m assuming they probably were hawk or falcon like animals, but given their rather unique snout morphology a more specialised diet like that of snail kites is also a possibility.

These animals clearly prove that toothed opposite-birds endured until the end of the Mesozoic, and considering avisaurids have typically been reconstructed as raptor-like birds I’m assuming Mirarce probably also had teeth.

Yuornis

Yuornis material from Xu et al 2021.

In 2021 a brand new completed enantiornithean was found in Henan, China. Roughly contemporary to the Mongolian birds, the ensuing phylogenetic study actually groups Yuornis with them, but the authors rejected this as bias due to toothlessness and elected to not make it part of Gobipterygidae.

Like gobipterygids Yuornis lacks teeth, but has a substantially different beak morphology, hence why the reluctance to consider it closely related t them. For starters its maxilla is more reduced (albeit much larger than in modern birds) while its premaxilla approaches the modern condition. Its beak is also rather narrow, and does not curve upwards. Combined with strong wings and perching feet, this seems like a Mesozoic analogue for a small corvid like a jay or magpie. No mentions of cranial kinesis are made, but several palatal elements are similar to more derived birds so it might have been able to do so.

If unrelated to gobipterygids, Yuornis represents a second lineage of toothless opposite-birds. This is not unsual as birds as a whole lost teeth multiple times and the same likely applied to Enantiornithes, but its clear by now that this was not the norm for the last enantiornitheans.

Falcatakely

From O’Connor et al 2020.

Falcatakely was found just two years ago and shows one of the most derived Mesozoic avian beaks of all time, with a maxive maxila and nasal while the premaxila is tiny, the polar opposite of modern birds. Small peg-like teeth line the end of the jaws, while the rostrum itself is deep and curved, resembling that of a toucan. It would then join hornbills and true toucans in the convergent evolution club.

But there’s a reason I left this for last. Several reseachers are not convinced it is actually an enantiornithe, with a viable alternative by Mickey Mortimer being an omnivoropterygid. Sapeornis like birds are known from Falcatakely‘s Maastrichtian locale in Madagascar, but so are pengornithid enantiornitheans (which coincidentaly match O’Connor et al 2020’s phylogenetic results for this bird). In the end, more evidence will be needed to determine it either way.

Conclusion

Its clear that Late Cretaceous Enantiornithes had a wide variety of lifestyles and ecologies, and with that came a variety of jaw anatomies. Some groups did indeed become toothless, but it is patently clear that many toothed species lived all the way to the end.

#enantiornithes#enantiornitheans#enantiornithean#enantiornithine#enantiornithines#paleontology#palaeontology#paleoblr#palaeoblr#bird#birds#dinosaur

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

WELCOME TO THE SABERTOOTH SHOWDOWN.

Saber-toothed (adjective): having long, sharp canine teeth

Admittedly, this is a fairly niche topic, so before actually constructing the bracket and releasing the matchups, I think it’s important to give a background for each taxon. That way, everyone will have at least a little bit of information to base their votes on!

The competitors will be organized at the genus rank, as many are extinct and there simply isn’t a whole lot we can infer about the variation between some species from only their fossils.

Each competitor will have a dedicated post including their overall ecological success, as well as my personal opinion of how they would rank in a tier list format. If you disagree with any of my arguments, please feel free to voice your opinion, as well as argue for the placement you feel is most appropriate for each competitor.

I will tag each background/rank post by the competitor’s genus, family, and class.

CURRENT COMPETITORS

There are currently 22 genera included in the tournament. Organized by family, they are as follows:

Felidae: Homotherium, Megantereon, Xenosmilus, Machairodus, Smilodon, Neofelis, Dinofelis

Nimravidae: Nimravus, Hoplophoneus, Dinictis, Quercylurus

Barbourofelidae: Barbourofelis

Oxyaenidae: Machaeroides

Thylacosmilidae: Thylacosmilus

Gorgonopsidae: Inostrancevia, Lycaenops

Lystrosauridae: Lystrosaurus

Anomocephaloidae: Tiarajudens

Stahleckeriidae: Lisowicia

Cervidae: Hydropotes

Cercopithecidae: Papio

Uintatheriidae: Uintatherium

If you have a genus in mind that you think should be included, please submit it, as well as your personal appraisal of their rank!

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or Treat!

you get this carved statue of homotherium latidens!

initially interpreted as a cave lion, this human-made artifact from france is now thought to represent the slender legged, short-toothed scimitar cat homotherium latidens. its short tail and thick, deep jaw imply a sabertooth affinity, rather than a pantherine one.

discovered in 1896 and officially described in 1910, this item tells us something very interesting; it was made later than the most recent skeletal remains of homotherium known from europe at the time. this interpretation implies that the taxon survived much later into the pleistocene than paleontologists at the time believed.

at first, this interpretation was dismissed due to the belief that homotherium had already been extinct for some time before the carving’s creation… until 2000, when we found a very, very young homotherium jawbone in the north sea.

turns out, this new sabercat jaw was only about 28,000 years old, confirming that homotherium did in fact live all the way up until the quaternary extinction! meaning that once again, our prehistoric ancestors have inadvertently gifted us priceless and accurate knowledge about the ecology they lived in. the person who carved this piece absolutely could have seen homotherium latidens in the wild, and likely did! a very cool story about the intersection of art and tradition with science :3

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinofact #117

Despite its popularity, Troodon is actually considered a wastebasket taxon and a dubious genus. One of the biggest factors to its dubious status is the fact that the holotype specimen is a single tooth.

Source: Wikipedia

#dinosaur#dinosaurs#paleontology#troodon#taxonomy#teeth#nomen dubium#fun facts#trivia#dinosaur trivia#dinosaur fun facts#6th#january#2022#january 6th#january 2022#january 6th 2022

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dinosaur tooth of an indeterminate theropod from the Isalo III Formation in Ambondromamy, Madagascar. It's not clear what kind of theropod this morphology belongs to, but it is possibly a coelurosaurian of some kind. Megalosauroids can be ruled out as the mesial carinae extends to the base of the crown. This Middle Jurassic morphology is described as being similar to those seen in the Upper Cretaceous theropod tooth taxon Richardoestesia isosceles, but given the huge gap in time, they are likely not particularly related.

#dinosaur#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#theropod#jurassic#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#恐竜#化石#古生物学

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

bro I'm fighting tooth and nail to remind my family to get my middle school sister to vaccinate... I hope you stay safe I'm sorry the world is Hell and sickness

in other news. Hey how's spineasours doing

MAN... 😭😭😭😭😭 i rlly hope she can get vaccinated AUGVUHGGUUHH if it helps, i heard hbomberguys video on the history of the antivaxx movement was pretty convincing for a few peoples families (altho it is like 2 hrs long...) ALLOF u stay safe 🫂🫂🫂

i havent heard any new spinosaurus news in a while but who knows.. maybe our favorite endlessly revised taxon will come thru 4 us once again

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists in Australia made an incredible reproductive discovery: 17-million-year-old sperm. The male sex cell was found in the fossilized remains of freshwater crustaceans, known as ostracods.

The sperm themselves are an extraordinary find. They were thought to be longer than the male shrimplike creature's body, but were tightly coiled up inside the sexual organs.

. . .

“The Riversleigh fossil deposits in remote northwestern Queensland have been the site of the discovery of many extraordinary prehistoric Australian animals, such as giant, toothed platypuses and flesh-eating kangaroos," Archer said in a statement from UNSW. "So we have become used to delightfully unexpected surprises in what turns up there."

. . .

Just as bizarre as the discovery is how scientists think the fossil was preserved: bat poop.

Professor Archer explains: “About 17 million years ago, Bitesantennary Site was a cave in the middle of a vast biologically diverse rainforest. Tiny ostracods thrived in a pool of water in the cave that was continually enriched by the droppings of thousands of bats.

"The phosphorus from the stream of bat feces mixed with the water and helped preserve these fossils. Bat droppings have also helped preserve fossils in France.

----

This is an old article, but I thought it might be new and interesting to other people to.

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified,[1] grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typically around 1 mm (0.039 in) in size, but varying from 0.2 to 30 mm (0.008 to 1.181 in) in the case of Gigantocypris. Their bodies are flattened from side to side and protected by a bivalve-like, chitinous or calcareous valve or "shell". The hinge of the two valves is in the upper (dorsal) region of the body. Ostracods are grouped together based on gross morphology. While early work indicated the group may not be monophyletic[2] and early molecular phylogeny was ambiguous on this front,[3] recent combined analyses of molecular and morphological data found support for monophyly in analyses with broadest taxon sampling.[4]

1 note

·

View note