#to sort of contrast mob who has a supportive and loving family

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Thinking about Reigen again and it's kinda wild just how little we know about his past or childhood or anything like that. Genuinely all we know is that: his mother is weirdly judgmental and kinda controlling, he has an older sister(?) that he doesn't seem to be in contact with, was really similar to Mob as a kid, and was bullied(though we do not know to what extent or how severe).

#he does have a line that only the worst of men hit women and we have no idea where exactly that thought came from in the first place#but I like to imagine that it comes from a far more personal experience than he's willing to admit...#my personal headcanon is that reigen had a rly troubled home life and was mostly neglected#to sort of contrast mob who has a supportive and loving family#his neglectful home life and being bullied lead to the seeds of his attention and recognition problems#as well as constantly lying to both himself and others and constantly having a mask up#I imagine that reigen rly doesnt like to talk about his family and he distanced himself from them for a reason#and reigen and his sister having a very distant and cold relationship to contrast ritsu and mob... augggghhhhhh !!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

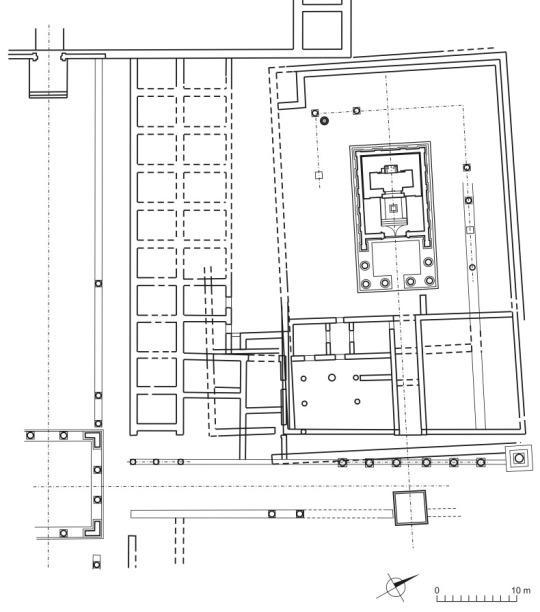

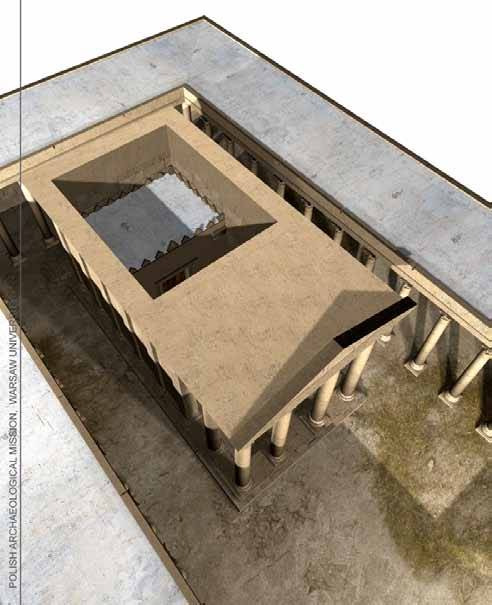

Temple of Allat

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

1st century CE

3D MODEL

The sanctuary of Allat included a temple which is clearly younger than the temenos itself. The same is true of the temple of Ba῾alshamin, and the two are very similar to each other, even if that of Allat is preserved only in its lower courses. Both are prostyle of Roman type with a Corinthian porch of four columns in front and two intercolumnia deep, facing East, both are articulated on three other sides with pilasters, both stand on low podiums and had plain pediments in front and back.

The Lion of Al-lāt is statue that adorned the Temple, of a lion holding a crouching gazelle, was made from limestone ashlars in the early first century CE and measured 3.5 m (11 ft) in height, weighing 15 tonnes. The lion was regarded as the consort of Al-lāt. The gazelle symbolized Al-lāt's tender and loving traits, as bloodshed was not permitted under penalty of Al-lāt's retaliation. The lion's left paw had a partially damaged Palmyrene inscription which reads: tbrk ʾ[lt] (Al-lāt will bless) mn dy lʾyšd (whoever will not shed) dm ʿl ḥgbʾ (blood in the sanctuary).

The temple of Allat can be dated from the internal evidence of two incomplete inscriptions as having been built in CE 148 or slightly later, barely twenty years or so after the cella of Ba῾alshamin. It is also clear that the same families were involved in the two sanctuaries. The fragmentary text from the doorway of Allat mentions two buildings: “this naos” and “the old hamana”. The latter term is Aramaic and applies to some sort of shrine. Here, for the first time, it can be ascribed with practical certainty to material remains.

These remains consist of the foundations of a small rectangular building, broader than it is deep (7.35 through 5.50 m), with very thick walls around a narrow room, barely large enough for the door wings to open inwards. This shrine has been piously preserved within the second century temple in such a way that the new walls enclose the old, leaving between them a space averaging only 6 cm wide. Stone of a different kind was used in each case. As the floor of the old building was laid practically on the ancient ground level, and as it continued to be used, the internal level of the new temple was lower than expected: the front columns set on a bench around the porch and the floor of the cella a few steps down from the porch.

The foundations of the new building also go deeper into the ground, which would have been no easy affair: they would have had to undermine the old shrine partly while keeping it intact at all costs. The cella is thus nothing more than a box containing the ancient tabernacle which remained in use as the adyton, the inner sanctum and seat of the goddess. This is apparently the only known case of such survival in Syria: usually, the adyton is built together with the temple, even if it may take the aspect of an independent building, as the two adytons of Bel, or incorporate some elements taken from the older phase, as in the case of Ba῾alshamin.

The exterior changed radically and became Classical in inspiration, Hellenistic for Bel, Vitruvian for the other two. In each case, however, these Corinthian temples were meant to impress the viewer and proclaim their belonging to the modern Roman world, but they were just a disguise. All three keep in different ways the memory of smaller, simpler tabernacles dedicated to the same godheads in the same places, but only the temple of Allat actually preserved its predecessor intact.

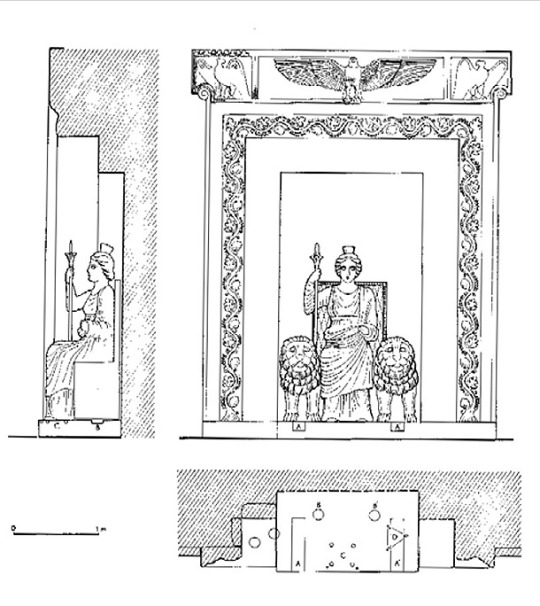

As the hamana of Allat remained complete, it would be pointless to roof the new cella above it. Indeed, there are good reasons to believe that the place was left open: not only has an outlet been arranged for rainwater, but more importantly, the pre-existing altar was left in front of the tabernacle but inside the temple, standing on a stone pavement not linked to either building; it could be used only if open to the sky. On the other hand, the porch should have been covered in the normal way. The narrow room inside the primitive shrine could not have any windows, as its walls are over 2 m thick. It was closed with two-winged doors which, when opened, revealed a statue inside a niche.

We have recovered several fragments of the framing, consisting of jambs covered with vine-scrolls and of a lintel featuring a spread eagle. The slab on which the statue was placed is preserved in place and bears a series of grooves and mortises suggesting a graphic restoration. This is possible thanks to several small replicas of the enthroned goddess, seated between two lions and holding a long sceptre. The statue was probably not of one piece but composite, and could perhaps have been moved from the throne to be carried in processions.

This is in sharp contrast to rituals that we can envisage for the relief images of other temples. But then, the idol of Allat was much older than the appearance of frontality in the art of Palmyra, and with it the possibility to represent the gods on a flat surface offered for viewing and veneration in other temples. Dated monuments allow us to fix the advent of frontality in the brackets between 15 and 30 CE. For its part, the idol of Allat (called “Lady of the House”), was offered by a certain Mattanai, being an ancestor of someone who mentioned the fact five generations later in 115 CE. This would bring back the original foundation to about 50 BCE at the latest (Gawlikowski 1990: 101–108).

By the same token, the first shrine of Allat becomes the oldest known in Palmyra and the first of which some remains are still in place. Another inscription found nearby mentions a hamana built in 31/30 BCE for the solar god Shamash. A square foundation 4 m to the side is still to be seen there, exactly on the axis of the Allat temple. It could have once contained a small inner room and the inscription could once have been placed in its wall, though we cannot establish this with absolute certainty. Another similar foundation was found a few years ago very close to the Allat temple. Possibly, the original temenos contained several such chapels, each for a different god. The Vitruvian cella had intruded in its midst about 150 CE without changing the character of the cult and scrupulously keeping the old installations in place.

The temple of Allat was destroyed twice: it was sacked once in 272 by the Roman troops of the emperor Aurelian and again, definitely, by a Christian mob at the end of the fourth century. In the meantime, the sanctuary remained in use within the limits of a legionary camp for over a century. One may imagine that access to it was restricted as far as the civilian population was concerned. The temple’s interior was radically changed during this time. Indeed, the old tabernacle contained within the cella had been destroyed together with the statue on the first occasion, while the walls of the cella seem to have remained intact.

At any rate, a restoration effort occurred very soon afterwards. Instead of trying to rebuild the shrine, its foundations were left in place and covered with a kind of platform including some sculptured fragments, which were thus piously preserved. We could recover some votive reliefs of the first to third centuries and some elements of the niche once framing the seated statue of the goddess. The cult image itself had to be replaced. Four short columns were brought in and set up in front of the masonry preserving the broken remains to support roofing in the form of a square canopy or perhaps a shelter from wall to wall over the whole ruin of the primitive shrine.

Under the canopy a new statue was fixed. Fallen and broken during the second sack, it has survived for the most part and could be reassembled. The statue is a second century copy of a statue of Athena, executed in Pentelic marble. It is clear that the original was Athenian and conceived in the circle of Pheidias. It has replaced an old and venerable, but no doubt primitive statue, and this in a time right after a military disaster and economic collapse. It could hardly be imported from Greece in these conditions, but could rather have embellished some profane public building in the city before receiving divine honours in the restored temple. The late restoration was probably an initiative of a Roman legionary legate under Aurelian, who wanted to reconcile the destitute local goddess, seeing in her no doubt Minerva, one of the standard Roman army cults. If so, the statue does not provide evidence for the cult of Allat, but is rather one of a series of Classical marbles imported to Palmyra for adornment of public buildings.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

#art#Architecture#travel#history#temple#tetrastyle#prostyle#merlon#corinthian#ionic#temenos#1 ce#2 ce#3 ce#athena#allat#al lat#nabatean#palmyra#tadmor#tadmur#lion#statue#roman#roman art#roman architecture#minerva#mythology

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

handmaid - 05

PAIRING: mob!sebastian stan x ingenue!reader

WARNINGS: age gap

A/N: sorry for the delay, i’ve been having a bit of a writer’s block recently and started getting out of it now. thank you so much for the support so far, hope you enjoy this one xx

NEXT CHAPTER

Sebastian was very much a powerful man in the way he carried himself to the way he spoke. She mostly stood by his side, basking in the glorious power he seemed to so easily hold over everyone who spoke to him. They spoke to him as if he were a king and, somehow, he was. After all, he managed to keep his family’s mob name still on top of any other and somehow even improved it, at least she heard from rumours on the street. All but one single guest had been polite, probably due to the fear he irradiated, that one being a guy named Thompson Williams. Mr. Williams was what Mr. Forrest called a mob rat, feeding on the wealth of those who had built it themselves without dirtying a single finger. His voice was mellow like snake’s venom, the politeness the fakest she’d ever heard, even Sebastian seemed to rush the conversation.

In order to do so, he had decided to finally dance with his fiancée, pulling her away from a pretty blonde haired guy she has been flirting with. Unhappily, Gwen put on a forced smile as he twirled her around the dance floor surrounded by other mob bosses and their wives. Seeing couples always brought a tinge of sadness to her. If there was something she knew is that she had to constantly be by Gwen’s side no matter her status which didn’t give her enough time to fin someone and if she did, she didn’t exactly think they would be happy to live with another couple. Besides, she was already in her early twenties and still to have a significant relationship with someone, the only one getting close being a guy she had met in private school who had taken her first kiss but other than that she just watched everyone fall in love while she waited in the wings.

Soon enough, Gwen was pulling her onto the dance floor, sending her off dancing with several men whose hands would constantly need to be watched fear they went lower than before. Whenever she thought she could step out of the dance floor and go stand, someone else was grabbing her hand to dance or Gwen was pulling her back in. As the seventh song finished, she managed to rush to the side, hiding behind one of Sebastian’s bodyguards before they could pull her back on the dance floor. She leaned against one of the table, soothing her very tired feet due to the unbelievably high heels he was using.

- Are you hiding, Y/N? - Sebastian came up from behind her, making her squeak ever so slightly due to the surprise.

- My feet really hurt. - she ever so slightly raised her feet. - I think Mr. Garret stepped on me a couple of times too.

- Mr. Garret is one for the wines. I wouldn’t put it against him as doing it on purpose.

- You and Gwen make a beautiful couple. - she gave him a warm feeling, not entirely sure why she felt sadness whenever she said so. Maybe it was because none of them really wanted to be in that relationship despite how great they looked together. - Although I must say, I didn’t pen you for dancing.

- Well, I was gonna ask you for a dance considering you’ve danced with every single man here but me. - he extended his hand towards her and despite the numbing sensation of her feet, she could find it within herself to deny him. She placed her hand upon his, tiptoeing a bit towards the dance floor.

Y/N considered herself a good dancer, at least a nice one to lead with but with Sebastian, things were slightly different. Her small squeak escaped her lips as he put his hands on her waist. She could almost feel the texture of his fingers through the thin beige lace fabric and suddenly she wished she had picked a thicker fabric. He was much more skilled at it than her, or maybe he was better at hiding how nervous he was. The latter was definitely true as he found it harder to control the grin that was trying to escape his polite stoic face as he felt her warm skin against his hand.

She turned her face looking at the people who were staring at him. She guessed that being that powerful had the disadvantage of the constant gaze of those trying to usurp his place. However, there was a sort of hiding kindness in his baby blue eyes, light, bright eyes contrasted to the darkness that followed him around. No, there was some sort of happiness in those eyes, a remnant of the child he once was.

- Everyone is staring at you. - she spoke for the first time ever they had started to dance, her eyes moving up to stare at his, the familiar nervousness starting to brew up and manifest itself in the heat up of her cheeks, warmer than the several candles displayed around the room.

- Trust me, angel, it is not me they’re staring at. - he twirled her around, pushing her a bit more towards his chest once she returned to her initial position. Y/N could feel every single cell on her body electrify and heat up.

- Maybe ... maybe you should return to dancing with Gwen. - appearances once again were important and Y/N knew it wouldn’t look good for the couple being celebrated being on two opposite ends of the room. She was the one to step away, half bowing to him and clapping as the song ended. Before Sebastian could even process her words, she had already departed to the sidelines of the dance floor, tapping Gwen’s shoulder and sending her straight to her fiancé.

It was still a harsh truth for her brain to process. As an English graduate, she was, as most graduates of the same course, an incurable romantic adoring the idea of kissing in the rain and small gestures that prove complete knowledge over your loved one. Here there were no hidden love, no unrequited affection, they were just getting married to form an alliance, to follow a contract set way before Gwen was born. Y/N understood her friend’s side and unwillingness to bend to the rules expected from her, she had always been a wild spirit who enjoyed relishing on her youth. However, she wasn’t one to agree with the constant petty remarks towards Sebastian.

- A remarkable party, isn’t it Miss Y/N? - Y/N sighed, watching Mr. Williams walk up to her side, a glass of red wine in hand.

- I would say so. - she replied politely.

- That is a very particular necklace you have there. - Thompson pointed at the necklace nested in the middle of her collarbones. - A gift from Mr. Stan, I would guess.

- No, I’ve had this necklace since I was born. However, with all due respect Mr. Williams, I don’t feel comfortable enough to discuss my personal life with you.

- You seem rather comfortable with Mr. Stan. - Y/N didn’t enjoy the undertones in his voice, taking a few steps behind and going onto a protective state. - Miss Y/N, you can trust me. Whenever you need anything, I’m here.

- I appreciate the gesture, Mr. Williams. I’ll keep it in mind.

- You’ll keep what in mind? - never once had Y/N been so happy to hear Sebastian’s voice and feel him looming presence behind her. Mr. Williams, however, seemed to keep his composure, merely raising his glass as a curtesy to the mob boss.

- I was just paying your new employee my respects, Stan. Offering my aid if ever in need.

- She won’t need your help. - he scoffed at the idea of a lower rank mobster being ever able to provide Y/N with someone he couldn’t. If Y/N ever needed something she was to come to him not to a rat like Thompson Williams who had made a small empire by screwing others over. No, Y/N would never need help from someone like him, if it was up to Sebastian’s will. Gwen too did not enjoy to see her friend speak with guys like Thompson, and like a spy was standing a few feet apart from the three, glass in hand, watching with a few bodyguards in hand if needed. - If you excuse me, my fiancée and I are retiring for tonight.

- Have a nice night, Mr. Stan, Miss Y/N. - she didn’t know how to explain it but her name felt wrong in that tongue. Like it shouldn’t be said and before she could politely reply as she had been taught, Sebastian already had a hold on her wrist, pushing her towards Genevieve who was willingly waiting to make sure her friend was alright.

- We are going home, right now. - Sebastian muttered to one of his bodyguards, ready to end the parade of his personal life. On the other hand, Gwen had other plans not exactly agreeing with leaving a party thrown in her honour that early. Y/N noticed her change in attitude, fully knowing exactly how her friend behaved whenever she didn’t agree with something. - Now means now, Genevieve.

- I’m staying, you can go. - Gwen looked at Y/N, her eyes begging for her to plead with Sebastian so she could stay over. Should she do it? No. Was she gonna do it? Well, it was Gwen, her oldest friend, so with a sight, Y/N turned on her heel to face the mob boss.

- We could go now and maybe let Gwen stay here with the bodyguards. For appearances. - she suggested and Sebastian seemed to pounder it. It was rather clear to him what Y/N was trying to achieve, she wasn’t that sneaky, however, he also did not want to have a fight with his fiancée for everyone to see. - I could stay too.

- No, Y/N, you can go. - Gwen definitely did not want to have a babysitter following her around and telling her to be mindful of her role, despite that being Y/N’s job since they were children. - I know you don’t like these functions anyway.

Sebastian did not reply, instead bolting out of the room followed by one of his bodyguards. Y/N gave Gwen a “be careful” look before rushing after him the best she could in her heels until she reached him, stopping him by grabbing onto the sleeve of his suit. The mob boss stopped, glancing for a few seconds at Y/N before sighing, placing his hand on the small of her back and leading her towards the limo. He couldn’t be mad at her for defending her friends, however, he could be mad at both of them not to follow orders, specially his orders. Sebastian was not one to have his control tested yet Y/N unknowingly did it.

- Do not disobey me next time. - he almost growled at her, watching as Y/N moved away from him, her innocent nature returning on full display.

- I’m sorry, Mr. Stan. - she bit on her lip, leaning against the limo’s window.

- I understand your loyalty towards Genevieve but I’ve been in this environment much longer than you and her have been. I know better.

- She’s young, marriage isn’t exactly what she wanted specially to someone like you?

- Someone like me? - she briefly looked to the side and even though she was in the dark of the night inside the limo, she was met by clean white teeth gritted down at her as well as a deep dark angry glared directed at her, of course. - Care to explain?

- A stranger. - she stated, playing with the fabric of her dress as not to look him in the eye.

- No, angel, that’s not what you meant. - he knew when someone was lying, his profession, if that could be said, called for that ability and she was lying. If not, she was at least trying to be kind. - What did you mean by someone like me?

- Well ... your ... your reputation follows you.

- You should know your friend’s reputation follows her too, she isn’t exactly the type of woman I would enjoy to marry.

The atmosphere was heavy and none of them really knew how to break the ice. Every once in a while she would look at him, briefly trying to see if his posture had relaxed but he kept on with his statue like posture which continued even as they rode the lift back to the penthouse. He took back to his office while Y/N stood at the entrance of the penthouse. Sighing, she took her shoes off and walked to the kitchen, grabbing a cup of iced water. Just like she used to do back in her old home, she stripped off her dress standing in a corset and petit coat that gave volume to the dress and sat on the balcony, drinking her glass of iced water.

Y/N knew better not to annoy Gwen or Sebastian, however, it feared her more to disobey Sebastian. He had enough power and men to dispose of her and make it look like an accident, however it wasn’t that which made her not want to disappoint him. It was something else.

She climbed the stairs to her bedroom.

It had been a long day.

tag list: @sideeffectsofyou @lilya-petrichor @xoxohannahlee @irespostthingsiwanttoseelater

#sebastian stan#sebastian stan x reader#sebastian stan/reader#sebastian stan x you#sebastian stan/you#sebastian stan x y/n#sebastian stan/y/n#sebastian stan imagine#sebastian stan drabble#sebastian stan fanfic#sebastian stan AU#mob!sebastian stan#mob boss!sebastian stan

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

BL Show Review Series - Until We Meet Again

The next show I am going to review is (spoilers) my favorite BL to date. It’s called Until We Meet Again, and it is fantastic.

Disclaimer that these are my own opinions, and I don’t know where the BL community as a whole stands on these shows. If I disliked a show you loved or visa versa, no disrespect is intended!

MASTERLIST OF BL SHOW REVIEWS

Mild Spoiler Warning and TW: brief mentions of suicide and homophobia

Until We Meet Again Rating: 9 / 10

I’ve put off writing about this show, because I’m finding it hard to articulate all of the reasons why the whole thing works so well. First of all, it needs to be said that whoever did the casting should get whatever the Thai version of an Emmy is, because every person involved in this show is so, so good. The standout, however, is Fluke as the main character, Pharm.

Fluke is, in my humble opinion, unequivocally the best actor in the Thai BL world. So much of the emotional work is done by him, in a show that is very, very emotional, and he carries the weight of the narrative really well. This man can cry on cue, and I swear he can make himself blush on cue too. You believe every second of his performance, and he makes Pharm very likable, relatable, and sympathetic without tipping over into helpless damsel territory.

Part of what makes the character so good is the quiet but firm way that he sticks up for himself. When Alex, the popular drama club president, starts to flirt with him, instead of running to Dean or meekly tolerating it, Pharm smiles politely and rejects him in a way that leaves no room for confusion. And when Dean does something that Pharm is uncomfortable with, Pharm forgives him with the gentle caveat that he never do it again. It’s said kindly, but you understand that Pharm means it, and Dean understands that too.

Anyway, that’s a hundred words just about how much I love Pharm, and we haven’t even talked about the main relationship. See, this is why I haven’t written about this show yet.

A quick overview of the show is that back in the late 80s, two university-aged men named Korn and In fell in love. However, their fathers disapproved, and Korn’s father was a mob boss who had tight control over his son. In despair, Korn kills himself and In, sick with grief, follows.

(left: Korn, right: In)

Then, cut to modern times, we meet Pharm and Dean, who we quickly understand are the reincarnations of In and Korn, respectively. It’s Pharm’s first day at university, and while he’s there doing all the introduction stuff, he meets his future best friends, Team and Manaow, and locks eyes with Dean.

Dean and Pharm both feel this connection, and their relationship is the sweetest, softest, kindest thing you will ever encounter in one of these series. Dean is a taciturn third year who is the president of the swimming club. He has plenty of female admirers, but he’s been looking for someone all his life. When he finds Pharm, he knows that his search is over. He is so gentle with Pharm, who is dealing with PTSD from In’s memories. At the same time, Dean doesn’t play any games. He makes it clear that he likes Pharm and wants Pharm to like him back. He never tries to hide his feelings with Pharm or anyone else.

(left: Dean, right: Pharm)

Ohm, who plays Dean, has less to do than Fluke, because Dean is not the primary POV character of the show, and he’s much quieter overall. But what he does well is watching Pharm and touching him like he is the most important thing in the world. He’s open with his affection and never gets hostile or aggressive the way characters often do in these stories. He’s a big guy, but he’s very kind.

Korn and In’s story is told through flashbacks that are mainly meant to mirror Dean and Pharm in the present. It’s hard to watch their happiness when we know how it’s going to end up. Earth plays In, who patiently and insistently chases after Korn. His smile is like sunlight. Seriously, he is a gift, which makes it all the harder to watch him go through so much pain. Korn is much more stoic. I think of all of the characters, he’s the one I had the hardest time connecting with. He keeps a very stern face most of the time, but by the end, it still hurts seeing him suffer.

One of the key things that makes this drama different than other BLs is that it has a genuinely compelling plot. We get to watch as Dean and Pharm navigate their new relationship while trying to piece together what is happening inside their heads. They also need to figure out how much of what they feel for each other is them and how much of it is because of Korn and In’s memories. The story went places I truly wasn’t expecting at times and kept me interested the whole way through.

The supporting characters on this show are also great. The secondary couple is Pharm’s friend Team and Dean’s friend Win. Win is the vice president of the swimming club, and Team is a junior member of the club. They immediately have that playful, fighting vibe between them that is really fun to watch.

(left: Team, right: Win)

Win’s character has lots of tattoos and piercings. He looks like a bad boy, but just like Dean, he’s actually very nice. He’s more mischievous and outgoing than Dean though. This makes him a better match for Team, who isn’t afraid to match Win’s attitude and return his teasing back at him.

Oftentimes, the secondary pairings bore me a bit, but I loved, loved, LOVED Win and Team. They are getting their own series next year, and I cannot wait for it.

Something else I want to point out about this story is that there are no Evil Female Characters. No clingy ex-girlfriends or scheming, jealous love rivals anywhere to be seen. But there ARE female characters, and they’re all great. Manaow, Pharm’s other best friend, is the main one. She’s played by Thai BL mainstay Sammy. Manaow is loud and friendly and supportive. She also gets her own boyfriend, though I wish we saw more of that relationship (give it to us in the sequel, pleassssse). Dean’s sister Del quickly joins their group of friends as well. Then there’s the less prominent members of Pharm’s cooking club. Female family members who also play big roles in the narrative.

The show isn’t without its faults. The one BLARING example that comes to mind is product placement. Until We Meet Again has the most blatant and annoying product placement I have ever seen. It almost feels like the show is stopping and having the characters give full commercials mid-episode. I refuse to mention the names of the products, but they are highlighted in a ham-handed way that is even more crass when you contrast it with the quality of the rest of the show. The worst one, by far, is at least relegated to a sort of mini-story after the episode. It involves one character encouraging another to go to the sponsored clinic and get cosmetic work done. The whole thing is not just gross but also out of character for both of them. I’ve pretty much erased it from my mind. Capitalism can burn.

The other thing is that occasionally the pacing drags a bit. I enjoyed it, but the director lingers 5-10 seconds too long on some shots, especially those involving eye contact. This is normal for BLs, but not to this extent. There’s an almost-kiss scene that drags on for nearly a FULL MINUTE in an early episode. At this point, I’ve rewatched the show so many times that I know when to hit the skip 10 secs button to move things along at a faster clip. But the first time I watched, I was like, “OK, I get it. They’re looking at each other and remembering events from their past lives. You have thoroughly conveyed this.”

But those are comparatively minor gripes and didn’t detract too much from my enjoyment. Watch this show. Have tissues ready.

And if you’re interested in fanfic, I put together rec lists for multiple BL shows including this one that can be found��here and here.

MASTERLIST OF BL SHOW REVIEWS

(Send me an ask if you have a show you’d like me to review - with the understanding that I will be completely honest - or if there’s anything you think I forgot or got wrong in this review.)

#until we meet again#uwma#bl review series#ohmfluke#deanpharm#dean x pharm#bounprem#winteam#win x team#kornin#korn x in#cooheart#kao x earth#thai bl#bl recs

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hogwarts House Sorting: Lucifer Characters

After hemming and hawing for weeks, I finally decided to commit to making this character analysis. I’ll be using the @sortinghatchats system of house sorting because I really love how much nuance it allows for!

You can find excellent explanations of the system on their blog, but a brief explanation for the un-initiated: Primary houses explain WHY a person does things. Secondary houses explain HOW they do them. Frequently, people may model another house, meaning they borrow that system or approach, but will fall back on their “true” house when the chips are down. Additionally, people can lose touch with their house(s) in a process called burning/falling/petrifying/stripping. Without further ado, here we go! Sortings under the cut. [Spoilers through Season 4].

LUCIFER MORNINGSTAR. I’ll start with Lucifer’s secondary, which I think is more straightforward. Our chaotic Devil is a Slytherin secondary through-and-through. He’s at his best when he’s improvising by charming other people, waltzing into a drug dealers’ home base, or paying off a traffic cop. While he can look like a charging Gryffindor or a favor-dealing Hufflepuff, these are ultimately tools that Lucifer uses to be a more effective Slytherin.

At first glance, Luci looks like a Slytherin primary, too. However, I actually think our titular Devil is a burned Hufflepuff primary who resorted to modelling Slytherin when he Fell. In fact, Luci’s character arc over the course of the show is to un-burn, a journey that starts even before he meets Chloe in the pilot. Hufflepuff and Slytherin primaries are both loyalist; the main difference between them is in the scope of their loyalty. Slytherin primaries prioritize a smaller circle of people whom they have decided to prioritize. In contrast, Hufflepuffs believe in the innate value of people, and seek to prioritize people based on need or a sense of what is fair–in Lucifer’s case, this revolves around the basic right to free will.

Hufflepuffs tend to burn when the world has treated them so unfairly that they end up believing that caring about everyone is an impossible goal. Facing this rejection, they narrow their circles and start to prioritize looking out just for themselves, or a few loved ones. This often comes with a sense of shame: if the Hufflepuff were a better person, they could be kind to everyone (and remember, being kind doesn’t mean being nice). Lucifer is constantly asking himself this question. Is he a monster? Can he be a good person? In the pilot, his first interaction with Amenadiel includes asking, “Do you think I’m evil because I was born that way, or because dear old Dad decided I was?”

At the beginning of the series, Lucifer mostly looks out for himself and, to a lesser extent, Maze. However, even in the pilot, we see glimpses of his inherent sense of justice and compassion for humanity. His interactions with Delilah (and his reaction to her death) set the stage, and his work with the LAPD–beyond his fascination with Chloe–continues the trend. Linda says it best when she tells him, “I think you’re starting to enjoy seeking justice for the good ones.” He only punishes people who have betrayed his innate sense of what is kind and fair–people who hurt other people–and he detests when someone takes away another person’s choice.

This isn’t to say that Slytherins can’t have this innate sense of fairness and compassion; it’s that a Slytherin would still put their “own people” first when the chips are down, and feel good about that decision. A Hufflepuff would feel like they’ve done the right thing when they put the collective good first. When Luci gives Marlotte her own universe at the end of season 2, he’s prioritizing the good of the world–and God and all his siblings in Heaven, estranged they may be–above keeping someone he loves very dearly: his mom. It’s a pretty significant character moment that this is the moral act which gives him his wings back.

Similarly, Lucifer’s pivotal decision at the end of season 4 also shows his Hufflepuff primary. He makes a huge personal sacrifice by going back to rule Hell, and hurts Chloe and his other loved ones to do it too. At the end of the day, Luci wants to do what’s best for humanity, even if it’s at cost to his inner circle. The flip side of this is the very Slytherin decision he makes at the end of season 3 which triggers the reappearance of his Devil face: killing Cain. Lucifer has killed exactly two people, both for the Slytherin motivation of protecting Chloe. Now, we can argue that Luci’s Slytherin model actually served him pretty well here, and the show generally wants us to support Luci after these difficult choices. But the key is in his reaction, which is an intense level of guilt uncharacteristic of someone who genuinely believes that the ends justify the means when it comes to protecting the people they love.

For our true Slytherin primaries, we need to look no further than the occasional murder-buddies, Maze and Dan.

MAZIKEEN SMITH. Maze is a classic Slytherin primary through and through, and she petrifies over the course of season 3. Her Slytherin primary clashes with Lucifer’s Hufflepuff primary as he slowly un-burns; she can’t understand why he cares so much about humans and why he would change for them. It also explains why she’s so betrayed by his refusal to take her back to Hell: For Slytherin Maze, Lucifer refusing to prioritize her must mean that he cares about her less. For Hufflepuff Lucifer, he has to consider the good of the system–and taking Maze back to Hell could endanger everyone else by angering his father. Plus, it would break up the family!

At the beginning, Maze’s circle consists of herself and Lucifer, and she’s willing to go to any length to protect him–including almost killing Chloe and siding with Amenadiel to bring Lucifer home. While her stance on humanity ends up changing, it’s primarily because she finds some humans that she happens to like–Trixie and Linda, first and foremost, though she adopts more as the series goes on. She tells Chloe, “I’m glad I didn’t kill you,” not because she suddenly decides murder is inherently bad, but because she ends up looking at Chloe and thinking, ‘This one is mine.’

Maze petrifies when she slowly loses everyone in her circle besides herself. This starts by Linda and Amenadiel lying to her and spirals out of control when Lucifer refuses to take her back to Hell. “None of you deserve me,” she tells him, and suddenly finds herself with no one to protect but herself. However, Maze un-petrifies at the end of the season; the first step is when Amenadiel shows her compassion, but she ultimately finds her place again when she rushes to save Linda from the bluffed threat from Cain.

Maze is a Gryffindor secondary. She’s at her best when she charges head (and knife) first into situations. However, she also has a Ravenclaw model that, similarly to Lucifer, she uses to make her a more effective Gryffindor. Maze collects weapons and fighting styles in a very Ravenclaw-fashion so that she can be the best possible torturer and bounty-hunter, but when trouble arrives, she’s not going to stop and make a plan–she’s going to kick trouble’s ass.

DAN ESPINOZA gets along with Maze so well because they’re both Slytherin primaries. Dan’s willingness to feed Warden Perry to the mob–and his lack of remorse afterwards–because Perry is a scumbag who hurt someone he cares about is clear evidence of his primary. He also knows exactly where to look for a little backup in Maze, who’s always down to offer him the means to his end. At his “Detective Douchiest,” Dan is leveraging his Slytherin primary to justify his bad behavior. He’s loyal to himself, after all, and throws himself into his work to avoid being attached to anyone else. However, Dan’s primary is also a strength. It makes him fiercely loyal and dependable to the people he loves–willing to do whatever it takes to protect them, or get them the revenge they don’t believe in getting for themselves.

Speaking of throwing himself into work: Dan is a Hufflepuff secondary. He’s a hard-working detective who keeps his head down–which makes him clash with his Gryffindor ex-wife, Chloe, who would rather make loud, controversial decisions in the name of justice–and puts in steady hours to chip away at his goals. When he’s in a good place, he puts a similar work ethic into the people he loves. When he’s in a bad one, he hides behind his work and detaches from the “human” side of his secondary.

CHLOE DECKER. Like I just mentioned, Chloe is a Gryffindor primary who desperately wants to pretend that she’s a Ravenclaw. Her Ravenclaw model–attributing morality to the legal system, carefully considering the facts when making decisions–can serve her well, and she falls back on it when she’s trying to wrangle Lucifer’s Slytherin antics. However, Chloe’s real strength has always been following her gut–occasionally to the point of self-righteousness. This also explains her base moral conflict with Dan, who both prioritizes people over ideals. A similar conflict could exist with Lucifer, but Luci is constantly encouraging Chloe to trust her instincts–he values her true primary more than her model. She has an innate sense of right and wrong that she has to fight very hard to overcome, and things normally go worse for her when she does.

I’m talking about the clusterfuck that was early season 4, obviously. Chloe sees Lucifer’s Devil face at the end of season 3 and is faced with a reality that her Ravenclaw model was stubbornly refusing to accommodate; she has a gut reaction of fear that tells her to run away. This initial need for space wasn’t actually the issue. I think that, if Chloe had met anyone besides Father Kinley, things would’ve been just fine. But when she meets Kinley in Rome, Chloe is manipulated into ignoring her Gryffindor instincts. Her heart is telling her to trust Lucifer–that he’s a good person who she loves. However, Kinley manipulates Chloe into trusting an external source of morality instead: his twisted brand of Catholic pedagogy. What restores Chloe’s conscience is tossing out everything Kinley tries to tell her and realigning with what she feels, which is love for Lucifer.

Chloe is also a Gryffindor secondary, although her Ravenclaw secondary model is more useful and stable than her primary model. Like Maze, she borrows the thoughtful planning and skill-collecting of a Ravenclaw. Chloe tackles cases by examining every angle, carefully interrogating suspects, and weighing the pros and cons of every solution. I would hazard a guess that most of her colleagues assume that Ravenclaw!Chloe is all there is–especially because she seems so much more sensible that her reckless partner. But if we dig deeper, Chloe is more than happy to charge into situations with a stubbornness and bravery that’s nearly unmatched. When push comes to shove, Chloe will take a psychologist on a date rather than wait for special permission to speak to a suspect, leverage Lucifer’s impulsivity to shake down perps, and stand between Lucifer and Cain’s henchmen while daring them to shoot.

AMENADIEL. Our resident solider of God is a little harder to pin down than most of the others for me, primarily because I really want to know more about his time in Heaven before the series started. Amenadiel reads either like a Ravenclaw or Gryffindor primary, though I lean towards a stripped Gryffindor. This is complicated by the fact that Amenadiel was stripped long before he realizes it during season 2. Stripped Gryffindors learn that they can’t trust their own moral compass and have to find a new system to follow instead. I think this happened to Amenadiel when he was still living in the Silver City, perhaps around the time Lucifer Fell, if not before.

Amenadiel functions by being his father’s loyal solider–by doing exactly what he’s told, because it’s supposed to be the right thing. He labels his brother as selfish, reckless, and evil despite harboring a clear love for him at the same time. This cognitive dissonance exists because someone else taught Amenadiel that he should believe those things about Lucifer. He survives in Heaven by falling in line–essentially adapting his father’s party line, like a Ravenclaw would. The issue is that a Ravenclaw would be satisfied with adapting such a system, and would not struggle as much to revise this system later if they found it inadequate.

In contrast, Amenadiel is constantly struggling to figure out what’s right. He’s horrified by his own behavior during season 1, causing him to Fall from angelhood and lose his wings and powers, but can’t seem to re-orient himself. He tries on different hats–first being like Lucifer, then following their mom instead of their dad, and finally trying to follow their dad again–but nothing ever feels right. Amenadiel’s greatest comfort is found in the realization that angels self-actualize. Once this realization comes, Amenadiel learns to trust himself again and regains his wings once and for all.

Amenadiel splits himself between Gryffindor and Ravenclaw secondaries and somehow manages to fail at both. (I say this with love). This is mostly because, I think, his Gryffindor primary is so stripped that his HOW is too detached from a WHY that makes internal sense–this leaves him ineffective and lost. Looking at season 4, though, I think Amenadiel is a Ravenclaw who models a Gryff secondary. While he’s still up for a Gryffindor-esque charge into the fight, Amenadiel approaches Linda’s pregnancy and impending fatherhood with a desire to learn as much as he can and make a better world for his son.

LINDA MARTIN is a Ravenclaw primary who briefly falls when she sees Lucifer’s Devil face, then promptly picks up herself back up and builds a new moral system for herself. It takes her about a week and she’s fairly satisfied with the result, even when her emotional and physical fears flare back up and she has to baby-proof her ceiling. Pre-fall, Linda believed in a system of compassion and warm skepticism, which made her an excellent therapist. She liked to think she might be reincarnated as a chameleon. She enjoyed the process of questioning the world. During her fall, Linda found her current system incapable of accommodating the simultaneously massive and personal scale of Divinity–and post-fall, she builds a new system that largely looks the same as before but, as Amenadiel helpfully points out, contains “different questions.”

With Linda, we’ve finally found a straightforward Ravenclaw secondary, no modelling to be found. Linda likes to plan for trouble, and she flounders when that opportunity is taken away from her. She’s constantly trying to remind people that she’s not that kind of doctor, and while she lets herself get swept up into Lucifer’s schemes–like breaking God out of a psychiatric hospital–she’s never comfortable in that kind of situation and the decisions she makes impulsively don’t tend to work out well for her (see: the resulting interrogation from the ethics review board).

ELLA LOPEZ is another “double” house, and our second Hufflepuff primary. While many people who have a strong religious faith can be seen as Ravenclaw primaries, Ella’s connection to her faith is driven by her innate love for humanity. She believes that people–including the Devil, who she says gets a bad rap–are basically good and deserve love and kindness. After Charlotte’s death, we see that Ella’s response is not to lose faith in her approach to life like a Ravenclaw might–instead, she resents a God who she thought shared her Hufflepuff morals and clearly doesn’t, if such senseless bad things can happen to good people.

Her Hufflepuff secondary is a fairly classic kind, combining cheerful work with an interpersonal warmth that endears people to her. Ella’s natural charisma is a sweet, understated variety that makes even Azrael, the Angel of Death, want to look out for her. While Ella rarely leverages this consciously–and her lack of desire to do so feeds into her charm–there are multiple points in the series where people casually go to bat for her. Two prime examples are when Charlotte tells off Pierce in an immensely satisfying fashion and when Lucifer scares Ella’s brother straight.

CHARLOTTE RICHARDS. Oh, dearest Charlotte. So much of her time is spent in a existential crisis that she’s another hard one to pin down. but I think she’s a Slytherin primary. When Charlotte finds out about the Devil of it all, she doesn’t run like Chloe, and she doesn’t have to reconstruct her view of the world like Linda does. Instead, Charlotte struggles to understand how to be a “good” Slytherin. Pre-trip to Hell, it’s implied that Charlotte lived fairly selfishly, extending her Slytherin circle to herself, her clients, and perhaps her children. Post-Hell, Charlotte is rocked to her core by the realization that she was not living free of guilt.

Now, some could argue that this means Charlotte isn’t actually a Slytherin. However, Slytherins aren’t free from other aspects of morality just because their first priority will always be their chosen people. Charlotte prioritized protecting criminals who she knew did terrible things, and she put herself first to an extent that many people would feel guilty about, even though most would agree that it’s good to put yourself first sometimes. When she’s trying to become a “good” person, Charlotte initially tries to give up her Slytherin ideals entirely. She quits her job and joins the DA’s office, trying to more like the cheerful Hufflepuff Ella.

This ultimately fails; it simply isn’t her. But Charlotte finds success–and a tragic redemption–when she learns that there’s more than one way to be a Slytherin. She turns some of her Slytherin loyalty outwards, towards victims and survivors of domestic abuse as well as new loved ones–Dan, Ella, and Amenadiel. She’s willing to go to great lengths to protect the people in her circle, which is still a very Slytherin motivation, but one that she feels much more at peace with in the end.

As for Charlotte’s secondary? Look, anyone who steals a dude’s motorcycle while cheerfully informing him, “Don’t worry, it’s for God!” is probably a Gryffindor. I don’t make the rules here.

MARLOTTE. The thing about being a Hufflepuff primary is that people matter, but not everyone has the same definition of “person.” At first glance, the Divine Goddess might look like a Slytherin primary. However, I argue that she actually values all “people” equally, it’s just that she considers Celestials to be people, and humanity to be both too foreign and simple to matter. (This logic is, by the way, the same reasons Hufflepuffs are no less capable of racism, homophobia, etc. than anyone else).

Goddess’s primary goal is to reunite her family, sans God, and she’s willing to roast a bunch of humans on the Santa Monica Pier to do it. Humans are fundamentally expendable–except for her “favorite human,” Dan, who essentially gets a loophole when she spends enough time with him and stops seeing him as “other.” But Goddess doesn’t consider any Celestial to be expendable. She’s not willing to harm Luci and Amenadiel, even when she realizes that they were planning to betray her. She doesn’t value herself more than she values her children, and she doesn’t play favorites. If she did, she might be content to try and stay on Earth, or to wage a war in which some of her children (i.e., the ones who didn’t side with her) died. If Goddess were a Slytherin, it would be possible to “kick” people out of her circle, like Maze does when she petrifies. Instead, Goddess’s natural state is essentially inclusive, much like her son, Lucifer–they just have a pretty substantial conflict over who gets included.

Goddess is a determined Ravenclaw secondary. When she needs to make things better with Lucifer, she learns how to make “cheesy noodles.” She throws herself whole-heartedly into learning how to live as Charlotte Richards–including reading every legal book every, apparently. While she’s certainly cunning like many Slytherin secondaries, Goddess actually doesn’t function very well without a plan. Things fall apart for her pretty quickly when she runs out of time in her body and has to make decisions off the cuff. Unlike Lucifer, who works best when he’s under pressure, she needs time to set up her course of action.

EVE is another difficult one to sort because so much of her characterization is about not knowing how she is. This makes her primary fairly obscured, and I hope we’ll see more of her in season 5 so I can revisit this sorting. For now, I’m going with a Gryffindor primary. Eve is motivated by doing what feels good–whether it’s leaving Heaven because she’s tired of being someone’s wife or convincing her boyfriend to punish people. She has an instinctive solution to every problem–even when logic says, ‘Hey, maybe don’t release demons from Hell?’ because she knows how things should be–and that’s with her and Lucifer together.

The reason she clashes with Lucifer is that while Eve’s primary is about ideals, Lucifer’s primary is about people–whether he’s operating on his Slytherin model or his true Hufflepuff primary. Lucifer cares a whole lot about other people’s desires–including Eve’s–but he doesn’t care that much about his own if they hurt other people. Interestingly, Chloe and Lucifer have this same idealist vs. humanist conflict; Eve and Chloe just have very different flavors of Gryffindor morality, and it turns out that Chloe’s ideals match up with Lucifer’s Hufflepuff values more of the time. Furthermore, Chloe comes to accept Lucifer’s Hufflepuff-ness in a way that Eve doesn’t. Chloe actually prefers Luci as a Puff–her Gryffindor righteousness says that they should protect other people, which is the same thing Lucifer wants to do.

Much like Ella, Eve uses a Hufflepuff secondary to build connections with other people that she can depend on. However, Eve leverages those connections on a much more conscious level than Ella ever does–in fact, it’s essentially the first thing that Eve ever does, both in her life and in the series. She starts by connecting herself to Adam, trying to be the perfect wife. Then, she leaves Heaven and seeks out Lucifer, relying on him to help her accomplish her goals. After getting dumped, Eve jumps to Maze instead. She’s a particularly effective Hufflepuff because of her Slytherin model, which allows her to adapt to whatever the other person needs her to be (see: the entirety of “Super Bad Boyfriend.”) You could make the argument that Eve is actually just a Slytherin secondary, since the “chameleon” aspect is so central to how she functions. However, Eve has a level of discomfort with her constant mask-wearing that a Slytherin secondary probably wouldn’t. In fact, deciding to part ways with her Slytherin model and figure out who she is represents Eve’s big character moment at the very end of the season.

MARCUS PIERCE/CAIN. I saved Cain for last because (in my opinion) he’s the closest thing to a pure antagonist that we have on the show, but frankly even that’s debatable [EDIT I FORGOT KINLEY EXISTED LMAO]. Anyways, Cain is a Slytherin primary who has been petrified for so long that he’s ready for a hard-out on the whole immortality thing. The only person in his circle is himself–we see, mostly in flashbacks, that this is because he’s tired of the pain that comes with losing people he loves. Cain only wants to live again once he adds Chloe to his circle and she reminds him what it feels like to have people to live for.

The neat and/or horrifying thing about Cain is that he’s a fantastic example of a truly insidious Hufflepuff secondary. His entire Sinnerman persona revolves around crafting a network of people and resources he can depend on. When Luci and friends put his back against the wall after the death of Charlotte, Cain doesn’t resort to charging, improvising, or leveraging his own skills. Instead, he calls up a bunch of people who owe him favors and are too terrified to betray him, and they do all the dirty work for him. It actually very nearly works, too.

#lucifer#lucifer netflix#sortinghatchats#i have like........so many more feelings but this got so long#but like i have endless thoughts about how different character dynamics are impacted by their houses#idk maybe ill make a sequel to this post with my thoughts on those?#we'll see#I wrote a thing

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Season 7 Characters

I am a good bit of the way through season 7 now, so I thought I’d share my thoughts on the characters. Overall, there’s no character I outwardly dislike (except Gothel but I’m meant to dislike her), but I only really like two characters, Drizella and Robin. As in, these are the only two characters who engage me on an emotional level. Everyone else is just sort of..... there. I am leaving out Rumple, Regina and Zelena because I’m lazy as fuck I have made my opinions known about them already and nothing as really changed. I am also not doing Naveen/Drew or Anastasia because as much as I like them.... they barely qualify for characters.

Anyway, if that didn’t put you of, then let’s-a go!

Drizella Tremaine/Ivy Belfrey- Oh my precious, crazy Drizella, you stole my heart in episode 6 (Wake Up Call) and have kept it. I think the main reason she is so sympathetic is because she has a relatable backstory-I’m sure a good number of people in the audience can relate to the frustration of being the second favourite child and living in the shadow of an older sibling. And Adelaide plays her so amazingly, small upset, dejected looks at her mother’s indifference to her in Hyperion Heights so that you can’t help but be on her side, even when I learn she is evil I still sort of rooted for her to make her mother regret what she did. Even after she drugs Ana, her tearful “I don’t want to die” made my heart ache for her. Wrong decision, completely wrong decision, but I can so, so get where she is coming from with it. I like how her arc centered on family and making amends with her sister. And then her redemption came and sent such a compelling character to hell with “well you ended up not hurting your sister for your own gain so good for you, don’t worry about us,your victims, just go live your life.” Oh Drizzy, I wish I could have given you the redemption you so richly deserved. I also would have liked less focus on Henry, because their relationship felt sort of random. And more exploration of her relationship with Ella.

Robin Hood-Mills/Margot- I’m so happy with how they used Robin. I find her such an interesting blend of the LWM and the Enchanted Forest, like watching her use the word “jerkwad” to a troll hunting mob in the Enchanted Forest. And I find her to be the most realistic character; her struggle with finding herself and her identity, the contrast between the “popular girl” she was in high school which just gave her a superficial happiness, and then finding her true calling as Robin Hood, doing something worthwhile, was so nice to watch. I cheered when she picked up that bow! And same in Hyperion Heights, Margot’s conflict with her mother is something very realistic, they never communicated enough. I also like her sense of humour a lot. And how she stands up for her beliefs and fights for the little guy-or girl, Alice, in her case-like a real Robin Hood. However, I don’t like how most of her main development took place in flashbacks, an issue I have with most characters. And I do find her present day character to be a bit... two dimensional. But hey, I have more episodes to go, so I could be wrong. I’d like to see more of her as a character, but from what I have seen I feel like she mainly exists as Alice’s love interest.

After this I think my reviews/analysis/whatever we’re calling this post are going to be less in-depth because Drizzy and Robin are the only two I really care for.

Rapunzel Tremaine/Victoria Belfrey- Well damn if season 7 did one thing, it was make a sympathetic villain with Victoria. I did find her a bit “knock off Evil Queen” until her backstory was revealed in 7x09. The whole theme of that episode was Punzy’s love for her family and even as a villain she is still doing everything because she loves Ana. My favourite kind of villains always have a sort of code or justification that makes them think they’re in the right. In a way, she reminds me of s1 Rumple, who kept his love for his son, but was still corrupted and evil with it. A moment for her that sticks out a lot is when Gothel has kidnapped and bound her and yet her concern is still for Ana, the first thing she does when she sees her is ask her if she is okay. That right there is some complex characterisation; she’s evil but with a tiny nugget of goodness left inside her. Now her redemption is where she falls down; she starts to realise that she should have focussed more on Drizella and less on the deceased Ana, which was good, and she saved Drizzy at the cost of her own life, but like I said before, Drizella was one out of many victims who never got any closure, most importantly Ella.

Lucy Mills- I do think Lucy is a lot like her father and that’s why I like her so much; her belief, her drive, and her sass. She isn’t really the most complex character there is, btu she’s just so loveable. She sees the best in everyone, even Tremaine (even if I sideeyed that part because come on bb). I don’t know what else to say about her; I can’t really say I love her development because imo, there is not much development to love, but who doesn’t love a funny, heart of gold munchkin running around believing in people all the time?

Tiana/Sabine-Well she’s... a good person. I like her development in becoming “her own knight in shining armour”. But like..... That’s sort of all their is to her. I do like her, she’s cute, her relationship with Naveen is adorable. She’ confident and strong but.... there isn’t a whole load of depth to her. Or maybe there is and I just forgot. I would say “I can’t believe ouat messed up the Princess and the Frog” but... it’s OUAT. She seems to fulfil the role of “supportive best friend” more than she does her own character arc.

Ella Mills/Jacinda-Okay for one thing-Dania does not deserve the hate she gets. She is a fine actress. Leave her alone demons. That said, she’s kind of like Tiana for me. Yeah she’s a good person but there’s not much depth to her. I feel like her lack of a backstory is bad for her because it makes it hard to sympathise with her. Sure we know she had a hard life but we don’t see it. I like her more in HH funnily enough, despite overall preferring the EF flashbacks. Watching her fight for Lucy is pretty cool to watch. The narrative fucks her over a lot, especially when t comes to Tremaine and how she did not once factor into her redemption arc despite being hurt severely by her.

Wish Hook/Detective Rogers- Sigh. Like Ella and Tiana, he’s a good person who deserves a happy ending, but that’s really all there is. He gets a little bit of complexity in 7x13 and 7x16 (I think), which is nice. They did skip over his redemption arc, which works for story purposes, but part of what I loved about Killian was his redemption arc. My favourite moments of his were him showing how much he had changed so WHook doesn’t fit that for me. I sort of see him as fundamentally the original character but less-less flawed, less self loathing, less redemption arc (that’s not grammatically correct but let’s move on). They also seem to have taken away the cheeky and sarcastic humour, which may make him more appealing to some people but I miss it. Objectively he’s pretty unproblematic, which I think in a way makes him boring, but undeserving of all the hate the CS fandom throws his way. He also gets manipulated and used a lot, which does make me feel sympathy for him. His scenes with Alice, young Alice in particular, are cute. And I do like that he stopped drinking. He’s a good man who deserves happiness probably more than anyone else, but kind of a watered down version of OG Killian. Don’t get me wrong, I tried really hard to love him but... I guess it wasn’t meant to be. Who knows, maybe at the end of the day, I did jsut see Killian as a prop for Emma, which is why I feel little attachment to a version that isn’t with her.

Henry Mills Swan- Henry is one of my favourite original show characters, so what drew me to this season was a grown up Henry. I am glad that despite being an adult, we still have that cute nerdy wide eyed dreamer of a kid. He does some things and I just think “that is so freaking Henry” like his fist pumping and Star Wars references and using his lunchbox as a weapon. And a lot of his child personality is still there, still an optimist who believes in people, but I feel like he’s matured a bit now. At the same time, he wants to be like the kind of heroes he read about and grew up with. He wants to give Ella a special ring like his grandparents had. I’ll admit there re bits where I don’t feel that he is Henry, but I think that’s because there is such a big jump between Gilmore!Henry and West!Henry.

Alice Jones/Tilly- I went in expecting Tilly to become my favourite, which is weird now because I am fairly neutral on her. I find it interesting the way she sometimes acts like an overgrown child because I think it is a way of showing how emotionally stunted she is, which is pretty neat. She is definitely very cute and makes an eccentric, bouncy kind of Alice, which is what I do think of when I think “Alice In Wonderland” (although my Alice knowledge is limited to the animated film and the Tim Burton one so I may not be very knowledgeable in that respect). I like her dynamic with Robin a lot. She isn’t really that well developed but she is fun to watch. I also wonder sometimes if her eccentricity and “strangeness” for a lack of better word is just her hiding how upset she is. I don’t really have anything else to say about her.

Gothel-To be honest, Gothel seems fairly one dimensional. There is very little to her. She wants to kill everyone because people killed her family. I feel like the writers have kept trying to make villains “bigger and badder” since s5 and then Gothel was just overkill. She has pretty much 0 redeeming qualities, which is cool, she’s the bad guy, but I don’t know, I think it just comes off as pretty shallow. Maybe a “she was always evil” story a la Cruella de Vil would have worked better? I will give it to them that she is very very creepy sometimes.

Dr Facilier/Samdi-I love how on the one hand, he is so, so like his animated counterpart but with enough uniqueness to stand apart. Daniel plays him so amazingly, his movements are so fluid, he’s charming but there’s a danger to him. He is a slimy little bastard (kinda like a... frog. See what I did there?). He intrigues me but I don’t see much to him. But he does remind me of s1 Rumple with his deals and general tomfoolery. I’ll come back to this section ocne I have watched more of s7, but for now my general perception is that he is fun to watch but I don’t see much below the surface.

#ouat s7#drizella tremaine#robin mills#rapunzel tremaine#victoria belfrey#lucy mills#tiana ouat#ella mills#wish hook#henry mills#gothel#dr facilier#lotta shit going on here#long post for ts#if you're on mobile

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

[book review] Earthseed duology (Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents) by Octavia Butler

"In order to rise from its own ashes, a Phoenix must first burn.”

So I find myself with a massive backlog of potential book reviews, although I’ve been doing a fair amount of re-reading and many of those are old classics (does the world need another review of The Brothers Karamazov? Or Siddhartha? Ironically Hesse would find the idea appalling as he is a firm believer that the more you try to discuss something to death the less power and truth it holds). I am of a similar mind about the Earthseed books (Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents) as they are very well acclaimed indeed and aren’t in desperate need of visibility. But I have things to say. Lucky you.

Parable of the Sower opens in 2024, when civilization has collapsed (the same year, as it happens, as the Bell Riots, so two sets of writers saw in the nineties the road headed on a thirty-year course to hell) to differing degrees depending on one’s socioeconomic status. The last of the middle-class holdouts live in self-policed, self-contained walled neighborhoods crowned with razor wire and glass. Groups only venture outside the walls armed. Despite this, people struggle to maintain some degree of normalcy and forward momentum—a local college still holds online classes (as it is too dangerous to travel to and from campus) and the community keeps holding church services and teaching its children in a living room-based school. Even as an adolescent Lauren Olamina realizes this is not sustainable, and that soon, the walls will be torn down and they will have to face the outside world as one of the dispossessed. Her realization that change is constant and inevitable, but that one must shape it, not try to hold to the old order, forms the basis of her personal philosophy she dubs “Earthseed”. It is partially her experiences as a “sharer”, or a person with hyperempathy syndrome, that informs her philosophy. When she sees others in pain, she feels it, as surely as if she herself was hurt. It is a handicap in a brutal world but she learns to live with it. In 2027 her prediction is fulfilled and she escapes the burning and plundering of her neighborhood and goes north—toward the Pacific Northwest, toward rain and opportunity. In contrast to her younger brother, who made his way in the outside world on cruelty and guile, she gathers a group of travelers and ex-slaves for mutual protection and support and from them forms her first Earthseed commune.

I found Sower at one of those clearance book sales that are frequently held outside Ackerman. The version they had has a rather bland, white-light background cover that tries to make it very clear that this is Serious Literature and worthy of consideration by people of intellectual fiber and not just the sort of riffraff who are mesmerized by the flash-bang tripe of sci-fi, but, at the very least, the protagonist is (correctly) portrayed as black. Unfortunately this often leads to the book being marketed or shelved as “special interest” but that is a whole other rant.

The broad socioeconomic changes predicted in the book are not surprising. They’re evident as imminent possibilities to many people. What always shocks me most in the writing of the most visionary speculative fiction authors – William Gibson, Margaret Atwood – is the correct prediction of small details. They predict tiny, sharp, and accurate vectors of future movement within the larger one. In the book Southern California is parched and dying and overcrowded and everybody wants to flood up to the Pacific Northwest, where there is water and the air is clean and there is space. This is exactly the trend I have seen now, twenty years after the book was published and ten years before the book takes place, and after several of the hottest, driest seasons on record (not counting that lovely burst of heavy rain this past winter). I’ve shot around vague “what are you going to do after graduation/in the future” etc conversations with various friend groups, who have no knowledge of each other and therefore no influence over each other, and with the exception of people who have personal ties elsewhere they almost all mention a vague tug toward “Seattle” or “Vancouver”, words that evoke greenery and cooler air and oxygen in place of dust. I’m no exception to this, despite the fact that almost all of my friends wound up in the LA area (many of us from Phoenix), but the way conversations are going we might all end up in the same place again anyway. In the books, Oregon, Washington, and Canada have sealed and armed borders to keep out floods of “California trash” hiking up I-5 looking for a better life. The flood has gotten bad enough that shoot-on-sight has become the accepted rule for guards. (And, from what I’ve heard of people currently living in those areas, that spirit is certainly there. It is understandable – their lovely area is being flooded with crowds of people driving up rents and costs of living, the rich buying up properties, the area choked with traffic. In short, it’s becoming SoCal. There’s a Tragedy of the Commons analogy here somewhere.) Given that communications infrastructure has collapsed most migrants are not aware of this, but even those who are feel it is worth the desperate attempt, because there is nothing left in SoCal for anybody but the rich. (In this case, ‘nothing’ really does mean complete anarchy and mob rule—the government has essentially become a privatized and parceled enforcement corps for the wealthy.) In the Real World LA we’ve had drought and relentless summer heat and given how overburdened the grid is the power goes out almost every time the temperature goes above 90*F. Even in the five years I’ve lived here traffic has gotten much worse (quantitatively—based on drive times) and rents have spiked dizzying amounts. The entire demographic character of neighborhoods around me has shifted in a matter of years. It all makes people feel like so much cattle and ferments a great deal of resentment and economic unrest.

In the first book the president runs on a populist platform that, at the time of publication (1993) might have sounded rather farfetched and Machiavellian, even though the country was coming out of the Regan years backlash, but at the current time sounds rather familiar. You know exactly where I’m going with this and I am far from the only person who has drawn parallels between President Donner and President Trump. Again, an example of prediction of ‘small’ details—a populist charlatan winning a desperate public is a common dystopian trope, but Butler correctly predicted the details of Donner’s plans and the rhetoric he uses to pit industry regulations and worker protections against this nebulous idea of “freedom” and “opportunity”. Company towns are a major part of the national fabric, and we see how they attract people (with promises of security and a constant source of food, no small offer when you grow up having to go around the neighborhood in armed groups) and the end result of (legally) indenturing people to their service through the use of payment in scrip. It’s a privatized debtor’s prison system. But, in the rhetoric of the elite, this represents “opportunity”, and the disgusting part is that they’re not wrong. To many people it’s more attractive than being murdered or raped on the road—until they realize that once they are legally ‘indebted’ (slaves), they will be treated that way anyway. But it’s the only “opportunity” offered to the masses. At this point in the story a good portion of the population is completely illiterate, and with that loss comes also the loss of their ability to learn about the past, to read and understand contracts and laws, to read newspapers. The school system collapsed, so you have a generation of young, angry people with no knowledge and no literacy. Hopeless, easy to inflame, easy to mislead. Butler is not coy in implying that this is a direct result of the end of the public school system and the collapse of public youth programs—money-saving measures touted as things that will ultimately lead to a more ‘efficient’ system (privatization). Surprise of surprises, though, once private those schools and youth programs no longer want to go where there is no money.

Donner also runs on a platform of returning to an idealized past – making America great again, if you will. (I almost did not add this because it’s too on-the-nose but fuck it. EDIT NOTE: I hand-to-God wrote this paragraph before I started reading Talents and I rescind my previous statement. Just keep reading.) When things are getting worse it’s only natural to want to turn back to when things are better. A savvy politician realizes this and uses it in his rhetoric—a vague promise. Lauren realizes that there is no turning back and that energies must be used to shape the future. As a leader, she is his direct foil.

Overt racism has again spiked in the wake of populist anger. Interracial couples are particularly likely to be attacked by mobs and in-group tribalism proxied by the marker of skin color is brazen. Lauren’s father points out (correctly) that their suburb is too black and brown to be of interest to authorities to try to re-claim, despite “respectable” middle-class status, and, indeed, it is one of the few white families in their neighborhood who is accepted to a company town on the coast. People get mean and scared when resources are few. Honestly as I am white I realize I am only made aware of overt shows of racism, so it is difficult for me to say how much worse things have gotten in the past few years (I do think that is the direction it has gone), but racists have certainly gotten bolder and more outspoken. It’s this ancient division tactic to keep the masses fighting each other for the few crumbs the rich leave for them, instead of focusing on the rich themselves. Again, not a new observation, but I am pleased with how accurately Butler predicted (or remembered, to anybody who reads history) that overt shows of racism and other forms of in-group/out-group behavior spike with hardship. People seem to think we’ve moved past that and become truly post-racial. Odd, that. People show their true prejudices under stress.

Women and children, especially, are vulnerable, and find themselves either disguising their sex (like Lauren, who is tall and angular in build) or finding men to travel with, often in exchange for sex—and condoms are rare, so this often leads to more pregnancy, more vulnerability, more dependency. (Aside – this is mentioned in the Saga comic, that women and children suffer most in war, even considering battlefield violence against drafted men.) Something Andrea Dworkin said – conservative women find the traditional marriage model attractive in that it is better to be raped by one man instead of by all men, and to get a roof and food in the deal. This is the origin of patriarchy. Lauren is well aware of this and is terrified of getting pregnant. In this book there is no Mad Max-like group of women acting in solidarity for mutual protection, but the concept of strength in numbers is proven in Lauren’s nascent Earthseed traveling group. Atomization – of the marginalized, of the weak, of minorities, of women – is what leads to death in a hostile world.

Lauren also learns that she is not the only person with hyperempathy syndrome (colloquially, ‘Sharers’) – it is a common result of in utero exposure to a new ‘smart’ drug, and it is a trait much prized in slaves and workers, as it makes them easier to control. The doctor in her traveling group points out that it would not be advantageous for healthcare workers, etc, to be paralyzed by another’s pain, but concedes that a greater prevalence might control a lot of the wanton violence. Sharers are also a uniquely vulnerable people; when they are in the minority, they are easily controlled, but were they the majority, the world would be a better place.