#to get this same realization as Correa talks about here

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

If you have an hour (on your commute, while cleaning the house, etc.), I HIGHLY recommend you listen to Juan Manuel Correa telling his story:

youtube

Trigger warnings: death, crash, trauma, pain, gruesome injuries, mental anguish mentioned.

#what an incredible story of human perseverance#juan manuel correa#when hr speaks about more to life than just racing#i can almost ehar charles saying the same thing#i am so glad he has other things in his life to bring him joy and fulfillment#and that he spends so much time with his close friends and family#sad that he had to have so many traumatic experiences early in life#to get this same realization as Correa talks about here#charles leclerc#anthoine hubert#f2 spa 2019#tw crash#tw loss#tw death#Youtube#tw trauma#tw pain

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Neutron Star Merger, The Fall of A Formula One Hero, and a Belgian Maiden Grand Prix Win

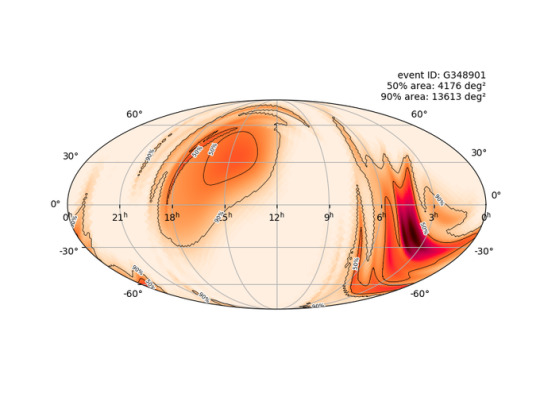

The LIGO/Virgo collaboration teams, observed a gravitational wave event of a Neutron Star merger "with the probability that the source may have at least one object in between three and five solar masses" said LIGO, on September 1st.

📸: LIGO Twitter

Kilonova observations are extraordinarily rare, for when Neutron stars collide, the remnants left are showers of gold and platinum scattered into the universe. These showers bring forth metals like the ones found on Earth.

Elements beneficial to our very existence.

Although the remnants here are believed to have merged into a black hole.

Who would have imagined that to the world of Formula One, that same rip to the fabric of space and time of a binary system hundreds of millions of years in the making, could have different consequences in the racing track.

It would arrive the same day that Charles Leclerc would make his Maiden Grand Prix Win.

While one can’t be certain what Einstein meant when he said, "God does not play dice with the universe,” we can only think of this moment. The Universe may be 14 billion years old, and with that, heroes and legends can be made because heroes are not born. Through pain and tears, downforce and minimal drag, Gravity much like F=ma, can be good friends, but in one wrong Turn, all can become the enemy, to Formula One drivers.

They are made, on the track and in moments such as these.

Racing For Anthoine

Like the great Carl Sagan once said, “For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.”

Anthoine Hubert, 22, of France, lost his life at the Belgian Grand Prix on August 31st.

The Renault French driver, was involved in a major accident with American Sauber driver, Juan Manuel Correa, at the Spa-Francorchamps. Hubert's car hit the bars then collided with Correa’s.

Correa, underwent surgery and “will remain in intensive care for at least another 24 hours to ensure that his condition can continue to be monitored by his surgical team,” read the official statement released on his website.

Anthoine Hubert, succumbed to his injuries after that tragic accident at Spa-Francorchamps.

A childhood friend to Charles Leclerc, someone he raced Karts with, laughed with, and joked with, perhaps looked up to race with head to head in this very track, the Monegasque now ran alone.

For Charles Leclerc, securing his maiden win at the Belgian Grand Prix, wouldn’t be the first place in his legacy, but a bequest to honor the memory of his now departed childhood friend.

Notwithstanding, everyone was racing for Anthoine and to honor his memory.

This was no ordinary race and as challenging as it was it would become one to remember.

The morning of Charles’ race, he'd been seen by the media talking to Anthoine’s family.

His mother, Nathalie, Father Victhor and brother Francois, gave him their support, as Nathalie embraced him.

That heartbreaking sight will live in the hearts of fans forever.

The Love of a Mother

📸: Kym Illman

It might have instilled love and strength in the Monegasque and a little extra push to go with the respect of millions of fans as a reminder that Anthoine would have wanted him to get to P1.

His last race having been practically stolen in Bahrain, this time, nothing would get in his way.

Phased, and unbelieving that any of it had happened, Anthoine’s loss, and his win, Charles said: “We were four kids dreaming of getting to Formula One.”

Anthoine Hubert, Charles Leclerc, Esteban Ocon and Pierre Gasly.

“We have grown up in karting together, so to lose him is a big shock for me, and everyone in the sport.”

“It was definitely the first situation for me where I have lost someone and then raced the following day. It is obviously quite challenging to close the visor and go through the exact corner —where he died— at the same speed as I did the day before.

Pierre Gasly, the Toro Rosso driver, gave Leclerc a little fuel to win the race too, had the words “ALWAYS WITH ME #AH19,” above the open view of his halo:

“I've grown up with this guy since I was seven in karting, we've been roommates, we've lived in the same apartment, in the same room for six years."

“We’ve been class mates, I’ve studied since I was 13 until 19 with him, with the same professor at a private school that the federation did. I’m still shocked.”

“You have to put it out of your mind because otherwise, you can’t race,” he added,

“I told Charles before the race: Please win this race for Anthoine, as we started racing in the same year, Charles, Anthoine, and myself. And Anthoine won the French Cup in 2005. We raced for many years and knew each other.”

Overtaken in Bahrain by a one-two Mercedes win, and getting wheel banged by Red Bull's, Max Verstappen in Austria, back in July, costing him-his first win, this one; means more.

“We lost a friend first of all — I would like to dedicate my first win to him. In my first race, we drove together, it's a shame what happened yesterday, I can't enjoy my victory fully.” Charles added.

"It is difficult to enjoy this victory, but hopefully, in two or three weeks, I will realize what happened.”

Everyone was cheering for Ferrari’s 16 to win it for Renault’s 19.

In the aftermath of Hubert’s passing, it’s hard to express what Leclerc must’ve felt like when he got to lap 19.

19 was Anthoine’s racing number, and the crowds paid tribute as well when the drivers came through.

it was no consequence that of all days, that Neutron Star Merger would be named S190901ap. The date that recorded the LIGO/Virgo's Neutron Stars Merger, which coincided with Anthoine's number.

And then you heard a solemn “This one is for Anthoine,” coming from Ferrari’s radio, said by Charles Leclerc upon finishing first.

Everyone burst, there was commotion everywhere, a good day and a sad day in Motorsports indeed for all the right reasons.

“It’s a good day but on the other hand losing Anthoine yesterday brings me back to 2005, my first ever French championship,” continued Leclerc during an interview.

📸: Kym Illman

A League of His Own

Seeing the Monegasque separate the Silver Arrows and keep good pace through and through, was what Formula One is all about, but is unfathomable to know how he must’ve felt while driving down Spa’s circuit or how he feels now that it’s been completed.

As youth of this new century, explorers and pioneers, one often forgets that millennials have much on their shoulders.

They’re here to make a name for themselves, and it's undeniable that on the way to greatness, they’re bound to lose those they love because this sport is ruthless.

Charles Leclerc won't be the exception, to the rule, but he's been the valid example of losing in every aspect and yet here he is. Racing and winning. Nothing deters his will to keep going.

The Scuderia Ferrari driver, and godson to Jules Bianchi, the last casualty to the sport before Hubert, is the living reminder that today's youth, still have plenty to look up to and much to fight for.

You could see him in the podium wearing a black armband with his entire Ferrari Team, as he raised his Trophy to the sky in honor of Anthoine.

Empowering generations of new drivers to not feel like outsiders. He might have lost a friend, his godfather, his father, that battle on two multifarious and defining races before, but on his third, he got his maiden trophy with a little help from above.

Lewis Hamilton of Mercedes spoke encomiums of Charles Leclerc after the race.

"It's not easy for any driver to jump into a top team like Ferrari against a four-time world champion, with much more experience, and then to continuously out-perform, out-qualify and out-drive him. But Charles’ results speak for themselves. There is a lot more greatness to come from him, and I am looking forward to racing alongside him in the future.”

“Then once I got in the car, as I did for my father two years ago, you need to put all the emotions to one side and focus on the job.”

Said, Leclerc “I was happy to win and remember him the way he deserved to be and, yeah, happy to do it on this day.”

"They are so much faster than us and Monza is all straights ... We will do our best, but it is going to be a tough job to match them.”

He lamented his inability to master those straights like Leclerc, before. Something the Monegasque is seemingly able to do. Monza will be the place to put the five time World Champion to a test.

"So, there's a lot more greatness to come from him and I'm looking forward to seeing his growth and racing alongside him ... Today, it was fun, trying to chase him. He was just a little bit too quick.”

Maybe, Chekhov was right after all about Entropy, that beautiful chaos that makes our universe work, It does come easy, but as I wrote in my book, “Entropy comes easy, but Love outgrows the Universe,”©️

"I was struggling in the corners, so that allowed him to get close," said Sebastian Vettel of Ferrari and Leclerc's Team mate.

"I couldn't hold him off for a very long time. I tried to obviously make him [Hamilton] lose time in order to give Charles a cushion, and in the end it was just enough, so it did the job.

"I couldn't stay in range to look after myself, and I was sort of playing a road block to make sure that Charles was gaining some time." He did everything to help his team mate achieve his first victory.

In a statement given by Daniel Ricciardo from Team Renault, he too admitted not wanting to race following Hubert’s untimely death.

“I know that, weirdly enough, the best way we can kind of show our respect was to race today,”

“But I don’t think any of us actually wanted to be here or wanted to race”

“At least, I’m speaking for myself, but I’m sure I’m not the only one. It was certainly tough to be here and try to put on a brave face for everyone.”

“I know a lot of people in the paddock are hurting so I think everyone’s relieved it’s done, we can move on from here, and hopefully it’s the last time that this happens.”

For the Renault fans, Ricciardo racing that day meant everything.

To know that a driver from his team had perished, how does one reconcile, to keep the morale high for the millions of fans aching so racing is the answer.

Is the one thing the Aussie does to help the fans, and he does it well. We appreciate the effort even when we know the heartbreak he's feeling. A collective effort from everyone now to help each other heed the call of the F1 neighbor even on social media.

We love him for it.

It becomes a Labor of Love.

“Since I was a child I’ve been looking up to Formula 1, dreaming to be first a Formula 1 driver, which happened last year, then driving for Ferrari this year, and then the first win today.”

“It’s a good day, but on the other hand, as I said, losing Anthoine yesterday brings me back to 2005, my first ever French championship. There was him, Esteban [Ocon], Pierre [Gasly] and myself. We were four kids that were dreaming of Formula 1. We grew up in karting for many, many years, and to lose him yesterday was a big shock for me but obviously for everyone in motorsport, so it was a very sad day.” - Charles Leclerc

📸:© Reuters/ FRANCOIS LENOIR

A day filled with grief, racing, camaraderie, and the inextricable reminder that; the Universe is always at work.

Congratulations, Charles Leclerc and Team Ferrari for a well-deserved win.

We knew you had it all along.

“And when you want something, all the Universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.” Paolo Coelho

Jen McCulley TM Sep 2, 2019

#charles leclerc#anthoine hubert#sebastian vettel#lewis hamilton#daniel ricciardo#pierre gasly#esteban ocon#scuderia ferrari#charles 16#formula 1#formula1#essere ferrari#formula one#f1#racing for anthoine#belgian grand prix#belgiangp#belgium gp 2019

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

from these dark waters (from this dark world)

Far Cry 5 | Hurk Drubman Jr./Female Deputy | Fluff and Angst

First chapter: prologue Previous chapter: chapter one

For notes and extras, find it here on AO3!

Note: I apologize if Hurk seems a tad out of character here...

chapter two

Bailey’s still weak when John kidnaps her to perform his crazy fucking baptism. He’s nowhere near as stealthy as his brother was, just has his people drive up in a van and grab her like in some lame-ass spy movie, and burns rubber before Hurk can do anything. He pulls his pistol and levels it on one of the rear tires, but they’re out of range too quickly.

Hurk runs back to Bailey’s truck and peels out, first intending to chase them, but realizing almost immediately that they’d gotten too much of a head start. He radios the Sheriff instead.

“Go to Fall’s End and get Pastor Jerome.” Whitehorse barks in reply. “He’s closer to John than I am, he’ll be of more help.”

“Oh my. Mr. Drubman riding in like a knight in shining armor.” John Seed croons suddenly.

“The fuck you doin’ on this channel?” Hurk snarls.

“Don’t worry. I’ll be sure to return her to you shortly. We just have a small matter to clear up.”

“You hurt her and I’ll kill you. You hear me, you sonuvabitch?”

“So protective.” John purrs. “Like I said, we have something we need to discuss.”

There’s no point in replying, so Hurk just grits his teeth and floors it.

He roars into Fall’s End about half an hour later, slamming on brakes and screeching to a halt right in front of the Spread Eagle. Mary May is out the door in an instant, shotgun gripped in both hands and a wild look on her face.

“What the hell, Hurk? What’s goin’ on?” She yells when he opens the door and slides out of the truck.

“John’s got the Dep. The Sheriff sent me to rally the troops.” Hurk replies.

“Damn.” Mary May hisses. “We don’t have a fuckin’ army here.”

“Just need a couple people.” Hurk says, jerking a thumb toward the truck. “All ’a Bailey’s shit’s in there. Weapons, ammo, explosives, the whole kit. Should be enough to arm a few folks. Set up an ambush and get ‘em on their way back to Seed’s bunker.”

“Yeah, okay.” Mary May murmurs, scrubbing her face. “C’mon in. Jerome’s inside.”

“Well, look at that! Hurk Drubman Jr. How ya doin’, kid?” Merle Briggs says when Hurk walks in.

“Been better.” Hurk huffs.

“Damn, if Hurk’s all serious an’ shit, then somethin’ big must be up.” Merle says, frowning deeply.

—

They wait until dark before they start moving, headed toward the river with headlights off. Hurk and Jerome lead the convoy in Bailey’s truck, threading through the valley quickly and carefully.

“That’s where he dunks his victims.” Jerome says quietly when they get close. A white van emerges from the trees then, turning onto the main road and accelerating. “Right on time.”

Hurk floors it, the truck’s engine roaring. He goes off the road and cuts through the woods, breaking through the trees and barreling up onto the road in front of the van. They slam into the van’s front end, the impact bone-shaking, and ram it off the road and down the hill. The airbags deploy, stunning them both for a moment, then they’re out of the truck and bounding toward the van. Hurk’s ears are still ringing when he rips open the backdoors, loud enough to drown out the gunshot that puts down the Peggie that Bailey is grappling with.

“C’mon, Ladybug. I gotcha.” He says, grabbing Bailey’s arm and hauling her upright. She sways on her feet and stumbles, and Hurk grabs her waist to steady her.

“See you went the dramatic route.” She wheezes, clearing her throat and nodding toward her truck. Or, well...what’s left of it.

“Yeah, sorry about that.” Hurk replies. “Runnin’ short on roadblocks, and we didn’t wanna tip off the Peggies.”

“I loved that truck.” She huffs.

“I’ll find ya a new one.”

“C’mon. Got a chopper coming for us.” Jerome says.

“Jerome Jeffries, right?” Bailey rasps, removing Hurk’s hands from her waist and taking a shaky step forward. She holds out her hand. “Bailey Correa. I’d been meaning to come say hello before… well, before.”

“Pleasure’s mine, deputy.” Pastor Jerome says warmly, taking her hand and shaking it firmly. “Let’s get out of here first, then we can chat, hm?”

“Yes, sir.” Bailey replies, grimacing. “I might need a little help.”

“That’s what I’m here for.” Hurk says, bumping her shoulder. “Let’s go fuck up some Peggies.”

—

“Goddamn, it is good to see you guys.” Mary May crows when they make it back to town. “Hello, deputy. I’m Mary May Fairgrave, and I am damn glad to see someone finally standin’ up to those assholes.”

“Tryin’ to, anyway.” Bailey says. She lets Hurk help her out of the car they’d taken back into town, and leans heavily on his arm. “I’ve heard good things, Ms. Fairgrave.”

“Please, just Mary May is fine.” Mary May laughs, reaching to shake Bailey’s outstretched hand. “Anything you need, deputy, we’ll get it for you.”

“Call me Bailey. I could definitely use a beer.” She laughs, then elbows Hurk in the ribs. “And a new truck.”

“One beer comin’ up.” Mary May replies warmly. “On the house.”

—

Pastor Jerome approaches Bailey three days later with a strangely guilty look on his face. She and Hurk had been holed up in the Spread Eagle since the baptism incident, and Bailey had spent most of those three days sleeping and eating.

“I’m sorry, deputy. I wouldn’t ask if it wasn’t important.” He says in preamble, and Hurk stands from where he’s been camped out on the couch and puts himself between them.

“No way, amigo.” He says, crossing his arms over his chest. “Look at her. She needs a fuckin’ break, man.”

“I know. And I’m sorry to even bring this up. But you’re the only person who can do this, Bailey.” Jerome puts his hands on Hurk’s shoulders and gently moves him aside. “He’s specifically asking for you.”

“Who is?” Bailey asks, sitting up in the full-sized bed Mary May had parked her in.

“A cult soldier. One of John’s Chosen. He wants to defect, and he wants you to help him.”

“And you don’t think this might be a trap?” Hurk huffs, looking at Bailey. “Someone else can do it. You ain’t fit.”

“Shut up, I’m fine.” Bailey retorts. “Where is he?”

“Silver Lake Trailer Park.” Jerome answers, looking relieved.

“We’re going.” Bailey says, throwing the bed covers aside and standing up. She’s wobbly on her feet still, and Jerome winces when she stumbles into the nightstand.

“This is stupid.” Hurk growls. “Which is sayin’ somethin’ comin’ from me.”

“We gotta do it.” She says, looking at him with a pleading look in her eyes. “Maybe if this guy successfully defects, more will do the same. It would save countless lives.”

“Bailey, you can barely stand.” Hurk replies, doing some pleading of his own.

“I’ll manage.” She huffs. “I was training to be a SWAT sniper before I came here. It hasn’t been too long, I should be able to knock the rust off and get my aim back. I can take a position somewhere up high and provide cover while your people get the guy to safety.”

“The general store should have a rifle you can use.” Jerome says, nodding. “I’ll radio the park and tell them you’re on your way.”

—

“Sniper, 200 yards, one o’clock.” Hurk murmurs, watching the Peggie sniper through the spotter’s scope Bailey had literally just taught him how to use.

“One second.” Bailey replies, firing at the last target before adjusting to find the new one. “Could you confirm that one?”

“Yeah, he’s dead.” Hurk chuckles.

A loud gunshot rings through the air, an unsilenced .50 cal, and something slams into the tree they’re taking cover next to about three feet above Hurk’s head. He ducks instinctively and starts to move, but then Bailey hums and takes the shot.

“Confirm?” She asks calmly, and Hurk takes a deep breath and looks through the scope. The dude’s laid out flat, dead as a fucking doornail.

“Yup. Got ‘im.” Hurk replies, looking at her and laughing giddily. “Damn, you are a good shot.” She grins, still looking through her scope, and Hurk takes a moment to appreciate the view. She looks good sprawled out prone like this, the M1 10 marksman rifle slotted against her shoulder like it belongs there, relaxed and loose and natural as she calmly takes aim. Nothin’ quite like watchin’ a beautiful girl with a gun, he thinks fondly.

“Did a few practice sessions with Grace Armstrong before the raid. I had, like, a two week window between Marshal Burke’s arrival and the actual arrest attempt? Maybe a little less. I used it like yoga.” She laughs and glances up at him. If she notices him staring, she doesn’t show it. “Never thought I’d actually have to use it for what it is.” She looks back into her scope, shifting a bit to find the Resistance team, and adjusts her sights. “They’re about to make it to the dock.” She murmurs.

Then Hurk sees movement out of the corner of his eye.

“Shit, Bailey, we got company.” He hisses, turning to face the movement and raising the M16 Pastor Jerome had given him.

“Easy.” She replies. “Take a deep breath, steady, and fire. Okay? Just like hunting.”

Then several Peggies break from the trees all at once and Hurk opens fire, spray and fucking pray.

“Fuck.” Bailey says, picking up the rifle and getting to her knees. She turns and fires a few rounds in the general direction of the Peggies bearing down on them, then thinks better of it and pulls her service pistol instead. Shouting starts below, from the direction of the dock, and Bailey swears again.

“Cover ‘em. I gotcha.” Hurk yells, moving so that he’s blocking her and taking down three more Peggies.

“They just keep coming.” She hisses, but he can hear her turn and lay prone again. “Shit, RPG!”

“What?!” Hurk starts to turn, to see what she’s talking about, and one of the fuckers hits him in the arm. He hisses and turns his attention back to the steady stream of assholes running toward them, and hears a fucking huge explosion behind him.

“No, nonononononono, oh fuck.”

“What’s happening?”

“We gotta move, now.” She snarls. He hears her get up and risks a glance back at her.

“Why, what’s goin’ on?”

“They’re all dead, and I lost the RPG. We’re no longer in control here.” She replies, her tone completely deadpan. “C’mon. Let’s move.”

“What do you mean they’re all dead?” Hurk asks, shooting the last two Peggies that run out of the trees. It’s quiet for a moment, so Hurk turns and jogs to catch up.

“I mean they’re all dead!” She yells, whirling around and jabbing a finger at the dock.

Or what’s left of it, anyway.

The nearby boat house is a starting to catch fire, the dock is completely gone, and there’s nothing but the framework of a burnt out boat sticking halfway out of the water. Bodies are floating nearby. Two are on fire. The round must have hit the boat directly, blowing it up completely.

“Damn.” Hurk says.

“Yeah. Now c’mon. I don’t know where that asshole went.” Bailey replies, turning and jogging down the hill.

—

They’re about halfway back to Fall’s End when the fucking gunshot wound in Hurk’s arm starts to really hurt. The adrenaline in his veins has long since run out, and the ache in his bicep is going from dull to throbbing quickly.

“What’s wrong?” Bailey asks, squinting at him from the passenger seat.

“Nothin.” Hurk answers, staring ahead as he drives one-handed toward Fall’s End. He’s glad it’s his left arm.

“You’re all tense.” She points out. “Are you hurt?”

“I’m fine, Ladybug, don’t worry.” He says, grinning at her. She just frowns deeper, but she lets it go, staring out the windshield with an unreadable expression on her face. “What about you? You okay?”

“Shoulda been able to save him.” She says quietly. “All of them. It’s not fair.”

“No, it’s not.” He agrees, glancing at her.

“I’ve been… struggling with the idea that— I don’t know. Never mind.” She huffs and looks down at her hands.

“Don’t do that, Ladybug.” Hurk says gently. “It ain’t healthy. Whatcha been strugglin’ with?”

“Something Jacob said.” She murmurs. “That I leave everyone worse off when I try to help. Maybe I should just get out of the way. I only hurt people.”

“Hey, you gave everybody somethin’ to believe in. Goddamn cult’s been killin’ the party ‘round here. But you’re givin’ everybody hope.” Hurk says, reaching over to grab her hand and trying not to wince when he has to use his injured arm to drive. “And a lot more folks would be dead if you hadn’t come along.”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, I do.”

#Far Cry 5#hurk drubman jr#hurk drubman jr/female deputy#john seed#joseph seed#jacob seed#faith seed#my writing#deputy correa#long post

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MR. WARREN BURNS

I wanna dedicate todays post to my first piano teacher, Mr Warren Burns. He was the first person to get me to sing, play piano and also play the saxophone. “Just the Way You Are” was the first song i ever learned to play and sing. He died when i was 13 from cancer and i didnt play piano again till i was 30 years old. I didn't even cry about his death till i was 30. I realized his effect on me was major and he is now one of my angels. If it wasn't for him i wouldn't be as musical as i am today. He was the first one to really believe in me and my talent as an entertainer. Mr. Burns thank you for believing in me. Till we meet again, here is my favorite shirt and favorite song you taught me for you! Thank you for being my first and greatest inspiration.

"Just The Way You Are" SONG/LYRICS By Billy Joel Don't go changing, to try and please me You never let me down before Don't imagine you're too familiar And I don't see you anymore I would not leave you in times of trouble We never could have come this far I took the good times, I'll take the bad times I'll take you just the way you are Don't go trying some new fashion Don't change the color of your hair You always have my unspoken passion Although I might not seem to care I don't want clever conversation I never want to work that hard I just want someone that I can talk to I want you just the way you are. I need to know that you will always be The same old someone that I knew What will it take 'till you believe in me The way that I believe in you. I said I love you and that's forever And this I promise from my heart I couldn't love you any better I love you just the way you are.

PHOTOGRAPHY: WWW.CALVINMA.NET @CMAERA

XOXO, AMY CORREA BELL

#AMY CORREA BELL#WARREN BURNS#PIANO TEACHER#MUSIC#INSPIRATION#POETRY#PHOTOGRAPHY#BILLY JOEL#VINTAGE TEE

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

I MET JOSH KUN in 2010, when the exhibit he had co-curated with Roger Burnett, Jews on Vinyl, opened at the Skirball Center. Kun is one of the preeminent cultural historians of Los Angeles, a deeply curious explorer of the pathways and palimpsests of our great universe of a city. He is a professor at USC, a MacArthur fellow, and the recipient of several awards, including the 2006 American Book Award and this year’s Berlin Prize. We were supposed to speak about his recent work on the inescapable Latin influence — led by a Los Angeles–based “wrecking crew” of Latin American musicians — on American music, but any conversation with Kun turns wide-ranging and we ended up talking about the changing landscape of collecting and archiving cultural artifacts in the age of constant content.

Playlists: Uno, Dos …

¤

GUSTAVO TURNER: The book you have edited, The Tide Was Always High: The Music of Latin America in Los Angeles, doubles as a treasure trove of information. I was only part of the way through your wide-ranging introduction and I had already built a long Spotify playlist of rare Latin-inflected jazz recorded in Los Angeles, including The Lighthouse All-Stars’ “Viva Zapata,” Cal Tjader’s “Manuel’s Mambo,” and René Touzet’s “El Loco Cha Cha Cha,” which you reveal as the original source for the “Louie, Louie” riff! How do you know when to stop gathering material for such a vast project?

Playlist: The Tide Is High: Los Angeles Jazz

JOSH KUN: Actually, there hasn’t been as much research on the Latin American imprint in Los Angeles music as one might guess and assume, so a lot of the research that we did, building up to the writing and the editing of the The Tide Was Always High, was figuring out exactly what music we should be thinking about. And a lot of that was just collecting records, and doing digs, following trails and clues — a friend would mention an artist or session, and that would lead me to say, “I never heard that record!” And then I’d have to get it — looking on eBay, going to record shops, and that kind of thing.

The fun part …

The fun part! It’s my core methodology. And inevitably, once you finish the book, all these other records are found, and some you ordered are delivered late and so they didn’t make it. You always find new things that might change the stories or add to the stories in some way. [He pulls a copy of Henry Mancini’s Symphonic Soul (1975).] For example, this is one that I was turned onto late, and it’s not in the book but it’s a really great one — Symphonic Soul, by Henry Mancini.

Not the first name one associates with Latin American music.

It’s technically like a kind of pop strings/R&B record as the title suggests, but he’s got all these little Latin traces throughout, like [Brazilian pianist] Mayuto Correa is on there [credited with “Latin American Rhythm”], and Abraham Laboriel [Sr.], the great bass player from Mexico City, whom we interview in the book, plays on this record and it’s a really great example of how these different worlds mix.

All these guys on Mancini’s Symphonic Soul — even the non-Latinos, like [vibraphonist and percussionist] Emil Richards, [keyboardist] Joe Sample, and [drummer] Harvey Mason — these guys were major players in the L.A. funk and jazz world that all played with each other and all were well versed in Latin American rhythms and Latin American songbooks. That was one of the great pleasures and joys of doing this project, is seeing how these different worlds connected. Henry Mancini, who relied on so much of Latin music in his film scores and soundtracks, working with Laboriel and Sample — that is pretty heavy, these are heavy, heavy cats. To have those worlds converge and connect became one of the sub-themes of the book: realizing how intertwined Hollywood studio recording sessions were with the actual club music scenes of jazz and funk, and beyond, in Los Angeles.

Many articles, books, and documentaries have been devoted to “the Wrecking Crew,” the celebrated group of Los Angeles studio musicians that show up in innumerable rock, pop, jazz and funk sessions from the Beach Boys to Elvis to Sinatra to Michael Jackson, but not a lot has been explored about this “parallel Wrecking Crew” which you could (and in many cases still can) call on when you wanted a Latin-inflected sound.

That’s precisely what we tried to address with this book. We have interviews with the top living Latin American session players in L.A. We managed to track down the majority of them. [Radio journalist] Betto Arcos and I did those interviews, and he was really helpful in identifying some of those great L.A.-based players. So we have Abraham Laboriel in there, [Brazilian percussionist] Paulinho da Costa, [Colombian reedman] Justo Almario, [Peruvian drummer] Alex Acuña, [Cuban percussionist] Luis Conte, [Brazilian percussionist] Airto Moreira, and [Mexican-American percussionist] Ramon Yslas. They’re all, save for Yslas, roughly the same generation, and together they played on thousands of recordings in the United States alone. And not just in “Latin” projects, but for major commercial artists like Joni Mitchell, or Madonna, or, in Paulinho’s case, playing on monumental Michael Jackson sellers like Off the Wall and Thriller.

The Latin American Wrecking Crew!

These guys absolutely were the Latin American Wrecking Crew, but interestingly, though they were often brought in to play “Latin music,” for the most part they were playing on everything, because these guys can play everything.

Doing interviews with them was so fantastic — hearing their stories like Justo Almario coming straight from Colombia, to New York, to L.A., and then playing with the Commodores. We wanted to make sure that these stories were out there and how that changes the official record, the history of what we think of as L.A. music. When we were researching the book, we started thinking about the role of Latin American musicians and Latin American music in Los Angeles as a kind of open secret with musicians. Everybody in the session music world knows this fact, that Latin American music is central. And yet, it still feels highly marginalized in the way we talk about music in Los Angeles, and for that matter, the way we talk about “American music” throughout the United States.

Several of the musicians that The Tide Was Always High recovers for Los Angeles musical history are Brazilian. The book includes a great essay by Walter Aaron Clark (“Doing the Samba on Sunset Boulevard,” on Carmen Miranda and the Hollywoodization of Latin sounds) and also a thoroughly original piece by Brian Cross presented as “a speculative history of Brazilian Music into Los Angeles.” Brazil is always a special case when talking about cultural influence: it’s its own thing, but also a central part of the Latin American puzzle.

It’s the Texas of South America.

Absolutely. And, as the really important Ruy Castro books on the development of bossa nova (Chega de Saudade [1990, translated as Bossa Nova] and A Onda que se Ergueu no Mar [2001]) make clear, the relationship between Brazilian music and American jazz has always been a very complex two-way conversation. In Los Angeles, the (barely) unofficial Brazilian ambassador of music has been Sérgio Mendes, who arrived in 1964 for the famous Carnegie Hall bossa nova showcase, headed to Los Angeles and never left or stopped being at the center of the Brazilian musician colony here. Whenever I talk to Brazilian and other Latin musicians, they all say that the first thing they do when they get to Los Angeles is go pay their respects to Sérgio Mendes. He is like the Godfather, or the Pope.

That comes up in literally every interview with Brazilian musicians in the book. They all say that for the most part they came here because of him. Sérgio was an active recruiter and advocate, he opened up this space. After the records he made with A&M Records, he was the guy and everybody talks about him as a power player and as someone who cleared some space for Brazilian musicians to come to Los Angeles and work with him, or work with projects, and that’s when a lot of that kind of cross-bleeding happens of Sérgio Mendes connecting with Quincy Jones and then Quincy Jones becomes somebody who falls in love with bossa and Brazilian music and that’s the Michael Jackson connection. In Brian’s essay, he writes about the relationship between Quincy Jones as producer of Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones as having already done Brazilian records decades before.

And of course, because of Austin Powers (1997), one of Quincy Jones’s biggest hits under his own name ended up being his “Soul Bossa Nova” (1962)!

That “Hollywoodization” of Latin sounds is actually important and something that Brian touches on. It happened to samba before bossa nova. In Brazil, samba is heavily African music, Afro-Brazilian. When it gets exported and enters Hollywood, in part through Carmen Miranda, its “Africanness” is kind of always there, but it’s also not there. Carmen Miranda becomes a de-Africanized version of a woman from Bahia. The world of blackness in the export of this music is a very important topic. When it enters the mainstream of Hollywood, Black Brazil it’s not so present. It’s sonically present but not visually present.

This “whitening” also happened with Mexican brownness in the case of songwriter Agustín Lara and 1930s “Mexican” (euphemistically called “Spanish”) exoticism in architecture and design, as LACMA’s recent Found in Translation shows. Also true about Caribbean music after Xavier Cugat and Desi Arnaz …

It’s what typically happens in the United States. It’s everywhere. And especially in the Americas, it’s rare when an Afro-Latino or Afro-Latina rises to the top financially, successfully in pop music.

Celia Cruz would be the exception.

Yes, she’s the exception. But for the rest, there’s always a kind of de-Africanizing that has to happen. I think of Shakira as a great example. She comes from a city with a prominent African musical community, Barranquilla, and yet there’s a kind of, and I don’t say this as a critique of her individually, but there is a whitening that has historically happened in the industry, particularly in the Americas. A kind of browning — or “beigeing” to use the old term.

There’s a chapter in the book about Latin American dance and its relationship to music in L.A. by Cindy García. Juliet McMains wrote a recent book about salsa in in the United States, and there’s a great chapter on Los Angeles about how salsa dance in L.A. was heavily influenced not by Afro-Caribbeans or Afro-Latinos, but instead was heavily influenced by the way people danced in Hollywood productions. Los Angeles’s version of salsa was so distinct from the East Coast because people were modeling their moves after Hollywood.

It’s the same thing that happens with jazz and R&B turning into big-band and swing. Tango is also one of the most egregious examples, where in Hollywood it becomes this weirdly stylized Valentino thing that is not even remotely close to the complex tango styles in Buenos Aires.

But then the question becomes how do you write about all this or talk about all this without clinging to an authenticity narrative or clinging to a purity narrative, which I did not want to do. I didn’t want to say that “this is bad and this is good” because, especially in a place like Los Angeles, it all gets thrown together, and it becomes a constant negotiation of high and low, and “authentic” Latin American music versus completely “Hollywoodized” versions of Latin America through Disney and lots of other channels. While it’s important to track those obviously, and provide critical histories of those, I think we were careful to not demonize in one direction and praise in another, but actually figure out how do we deal with the middle ground, which is kind of the norm here.

Going back to Sérgio Mendes, he would be a great example of that. He has been one of the most commercial successful Latin musicians here for decades, but his music is deeply uncool for many “hip” listeners.

Sérgio is a great example. Those early Brazil ’66 records were brilliant in terms of genre splicing and him learning the market. Sérgio covered “For What It’s Worth,” the Buffalo Springfield song about the Sunset Strip riots in 1966. It’s a really beautiful, kind of awesome, slow funk song. How perfect is that? It’s him saying, “Come on — I’m an L.A. artist, so I can do a Brazilian funk version of the Buffalo Springfield song about white kids rioting on the Sunset Strip and that’s my purview, and that can be part of my songbook and I can cash in on it, but also make something new.” And I love his songbook!

Speaking of songbooks, you also rescue the figure of Trini Lopez. One could argue that the unstoppable rise of the DJ killed that type of entertainment in Los Angeles — the super-professional live bands of session players that could play all the big hits in their own style. Los Angeles in the 1960s had frontmen like Trini Lopez, Johnny Rivers, José Feliciano, who specialized in what today we would call “covers.”

Trini Lopez was, as he was often called, a human jukebox. At PJ’s, he would churn out all the hits of the day and do his own Latin spin on them. That’s something that I really like. I have a soft spot for that modality.

Before we move over from Brazil, we have to talk about Carmen Miranda. In a sense, the Carmen Miranda project of Americanizing (or Hollywoodizing) Brazilian music in the 1940s is a good example of an L.A. modernist project.

I completely agree.

In the Busby Berkeley sense.

Absolutely! Hollywood’s role in that is big. We did a tribute to Latin American composers in Hollywood as part of this project at the Getty where we put together a big band and we did songs by Esquivel, Agustín Lara, María Grever, Lalo Schifrin, and Ary Barroso. Part of that show was a claim about modernism, making the claim that these are modernist strategies that are not ever talked about as such, or rarely.

An image that I always think about is the iconic photographs of the Koenig Case Study Houses, and all these iconic Julius Shulman shots of midcentury Los Angeles with upper-middle-class or upper-class white couples in their perfect midcentury outfits, and the Eames chairs, and all the right furniture, and they always have a hi-fi. And nine times out 10, what’s on that hi-fi? It’s always Pérez Prado records or Esquivel records! There’s a soundtrack to midcentury modern and it’s often Latin American–influenced, but it’s been left out, I think, of the narrative of what counts as L.A. modernism. The Tide Was Always High makes the argument that Latinos and Latin American culture are a kind of “ghost in the machine” of L.A. modernism. It is always there haunting it, but it’s rarely talked about with the centrality that it deserves.

It’s like a musical counterpart to the “Mayan” influence in modernist architecture in Los Angeles.

This has been a big part of the work of Jesse Lerner, a curator, writer, and filmmaker who did a series on Latin American experimental film for Pacific Standard Time, called Ism Ism Ism / Ismo Ismo Ismo. And he co-curated the exhibit about Disney in Latin America with Rubén Ortíz Torres. Jesse is an amazing thinker and he wrote a great book called The Maya of Modernism, and it’s all about the role of the “Maya” in the modernist imagination, from the Ennis House to the Aztec Hotel in Monrovia, which is actually Mayan-inspired design but it’s called “Aztec.”

With a soundtrack by Yma Sumac!

We had an essay about Peruvian, Incan singer Yma Sumac in the book and we did a concert paying tribute to her at the Hammer. The singers had to figure out how they were going to do this, and often they would ask for lyric sheets, of which there aren’t any. One of the singers emailed, “Can you send me the original quechua lyrics?” And I said, “I don’t think they’re in quechua.” And she started thinking — and she’s from Mexico City — and she said, “I think they are.” So we started poking around, and according to the only book that’s been written about Yma Sumac they are wordless. It’s not quechua. And she said, “Oh yeah, but everything is wrong in that book and he makes claims that she’s singing this and she’s not singing that.”

Was it quechua?

It went back and forth and we ended up with: “It’s not quechua, but it could be quechua, but it could not be, and it’s wordless and it isn’t”! And that was part of what was happening, that there was this open play with exporting manufactured authenticity, and creating this commodified image in the case of “Yma Sumac,” of the Incan Princess who ends up at the Hollywood Bowl or Capitol Records and people are buying her records because she’s supposedly singing in quechua, when in fact, she might just be making words up.

But it doesn’t at all detract from the extraordinary arrangements and the extraordinary talent of her as a singer and performer, so it was really interesting and instructive to watch contemporary artists grapple with that and figure out how they perform themselves in relationship to that.

I wanted to bring up the issue of Latin musical communities in Los Angeles and gentrification. For example, the Boyle Heights community.

I don’t live in Boyle Heights and I cant speak for anyone in Boyle Heights and so I leave those debates to the folks who are rooted in their community and are doing what they believe is the important work for the sustainability of their community and the sustainability of their histories. And I support that 100 percent.

The Boyle Heights of late 20th and early 21st centuries is not the Boyle Heights of the 1950s and ’60s, and it’s important to not confuse those, they are different histories. The Boyle Heights that produced so much of the R&B and early Chicano Boogie Woogie, the Pachuco boogie music of the ’50s, was very different from the Boyle Heights that emerges post-1980s, where Boyle Heights goes from being one of the most multiethnic, multiracial, multilingual immigrant neighborhoods in the country to being one of the least, to become predominantly a Mexican neighborhood. Those are different histories, and I think that we have to approach them very differently and I always try to resist a little bit this, “Oh, it used to be an immigrant neighborhood, and it used to always welcome immigrants.” Well, that’s true, but it’s a different political and cultural climate right now.

Although gentrification and redevelopment are constants in Los Angeles.

These are real issues. I always remind my students that people are fighting because they feel that something’s at stake and there’s a real visceral fear that something is being taken away, and we have too much history in Los Angeles where we’ve seen communities be displaced. We’ve seen people being bulldozed, literally, by corporate, city, commercial entertainment developments, and I don’t think we can quickly turn a blind eye to it. So I think it’s really important.

I did a big project from the Phillips Recording Company a few years ago, where we were looking at the history of this very important record shop and music store that was in Boyle Heights from the 1930s to the 1980s. Latino, African American, Japanese American — it’s really this idealized, archetypal example of that story. Even in doing that project, I started worrying about what that nostalgia was about. Why was I and why were so many of the people that I knew so invested in that earlier Boyle Heights story and less invested in the contemporary Boyle Heights story? Where are all the histories of what’s been happening since the ’80s in Boyle Heights? And that’s been told largely through Chicano historians, it’s been largely told by Chicano activists and Chicano musicians. The rise of son jarocho from Boyle Heights as a community force, the rise of Chicano alternative music or rock in espa��ol — those histories are being written right now and I think that’s really important and I’m looking forward to 10 years from now what views we have backward to this moment.

It’s really easy to talk about — especially for a white secular Jewish guy — to cling to these old stories and I want to call myself out, I wanna check myself and others on it, to say, “What are we not talking about if we keep talking about the 1950s?” I’m talking about the continual inequalities of Latino life in Los Angeles, the continual transformation of the public spaces of Los Angeles, the ongoing patterns of redevelopment.

I also wanted to bring up the role of thrift stores and record collecting in the survival of a lot of this culture.

Physical thrift stores or digital ones like eBay?

Both, I guess.

These days I’m usually pretty target-driven. My first step: EBay. Set up an eBay search. Second step: Set up a Google News alert. And then start looking for the specific thing you’re looking for. Because pre-eBay I would spend a lot of time traveling, a lot of time driving, even flying to thrift stores in neighborhoods where things might be located and it would always be a crapshoot, you know? You might find something you’re looking for and you’d find a lot of things you were not looking for which might not be useful for the project. I find that online searches can be good at helping you target things. Most of the things I’m interested in are not in official archives, in formal archives, and so it’s hard to find them, but eBay can be very, very helpful.

Don’t you worry about the future of these artifacts you write about?

I do. But that’s another difficult question. Institutionalizing it could take on all kinds of different shapes. We’re just starting at USC to think more about this in terms of Southern California collections. Everyone is getting rid of their records. After I did the Jewish album cover book, that was almost 10 years ago, and to this day I get at least a few emails a year from somebody saying, “I live in blah blah blah and my uncle just died, or my father died and I got a box of Yiddish 78s and I don’t know if I should throw them in the trash or, you know, can I send them to you?” I don’t want them all, though! Part of me always wants to say, “Yeah! Send them to me,” because I do want them all. I want it all in theory, but I don’t want it all in dust and boxes and there’s so much stuff.

And you can’t preserve it all?

We can’t. And so the question becomes: “What do you preserve? And why?” That’s why I think the role of the curator and the role of the archivist, is really tricky.

Music Man Murray, who had a record shop, when he was dying, everyone was trying to figure out what to do with his collection and who would buy it. And I was trying to convince USC to buy it. And we worked really hard to figure out investors, and things, and it became this big question of like, “Well, its 400,000 objects. Where are we going to put that?” To buy that is actually the cheap part. The expensive part is long-term storage, digitization, ongoing preservation. It’s super expensive. And then what? We have four warehouses full of 400,000 things. Who’s going to staff it? Would people visit it? Who’s going to index it and do the metadata? These are really important questions.

It’s much harder than the Library of Congress picking 25 films a year to preserve.

It is. But I understand why and I am very sympathetic to that method. My sheet music project with the L.A. Public Library involved working on an archive of 100,000 pieces of sheet music and songbooks and figuring out which 200 of them are the ones that should be in a book and be our primary storytelling devices.

Don’t you feel you’re killing part of history when you choose something over something else?

Oh, I know I am. That’s why in all my projects I am careful to say, “This is not an official version, this is my version, in this book, in this project.” And if you, Gustavo, went and did this, it would be, and should be, a totally different book.

I had to become very comfortable with the inherent failure of all my archivist projects. Even this new book, there’re so many things that aren’t in there and there’re so many different ways of telling this exact same story, it can keep you up at night. It does keep me up at night.

But it really can make you crazy if you worry about it all the time, and then you never write the book.

¤

Gustavo Turner is a writer and photographer in Los Angeles. Instagram: @gustavoturner and Twitter: @eyecantina.

The post The Latin American Wrecking Crew: A Conversation with Josh Kun appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2phDDcv via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

I MET JOSH KUN in 2010, when the exhibit he had co-curated with Roger Burnett, Jews on Vinyl, opened at the Skirball Center. Kun is one of the preeminent cultural historians of Los Angeles, a deeply curious explorer of the pathways and palimpsests of our great universe of a city. He is a professor at USC, a MacArthur fellow, and the recipient of several awards, including the 2006 American Book Award and this year’s Berlin Prize. We were supposed to speak about his recent work on the inescapable Latin influence — led by a Los Angeles–based “wrecking crew” of Latin American musicians — on American music, but any conversation with Kun turns wide-ranging and we ended up talking about the changing landscape of collecting and archiving cultural artifacts in the age of constant content.

Playlists: Uno, Dos …

¤

GUSTAVO TURNER: The book you have edited, The Tide Was Always High: The Music of Latin America in Los Angeles, doubles as a treasure trove of information. I was only part of the way through your wide-ranging introduction and I had already built a long Spotify playlist of rare Latin-inflected jazz recorded in Los Angeles, including The Lighthouse All-Stars’ “Viva Zapata,” Cal Tjader’s “Manuel’s Mambo,” and René Touzet’s “El Loco Cha Cha Cha,” which you reveal as the original source for the “Louie, Louie” riff! How do you know when to stop gathering material for such a vast project?

Playlist: The Tide Is High: Los Angeles Jazz

JOSH KUN: Actually, there hasn’t been as much research on the Latin American imprint in Los Angeles music as one might guess and assume, so a lot of the research that we did, building up to the writing and the editing of the The Tide Was Always High, was figuring out exactly what music we should be thinking about. And a lot of that was just collecting records, and doing digs, following trails and clues — a friend would mention an artist or session, and that would lead me to say, “I never heard that record!” And then I’d have to get it — looking on eBay, going to record shops, and that kind of thing.

The fun part …

The fun part! It’s my core methodology. And inevitably, once you finish the book, all these other records are found, and some you ordered are delivered late and so they didn’t make it. You always find new things that might change the stories or add to the stories in some way. [He pulls a copy of Henry Mancini’s Symphonic Soul (1975).] For example, this is one that I was turned onto late, and it’s not in the book but it’s a really great one — Symphonic Soul, by Henry Mancini.

Not the first name one associates with Latin American music.

It’s technically like a kind of pop strings/R&B record as the title suggests, but he’s got all these little Latin traces throughout, like [Brazilian pianist] Mayuto Correa is on there [credited with “Latin American Rhythm”], and Abraham Laboriel [Sr.], the great bass player from Mexico City, whom we interview in the book, plays on this record and it’s a really great example of how these different worlds mix.

All these guys on Mancini’s Symphonic Soul — even the non-Latinos, like [vibraphonist and percussionist] Emil Richards, [keyboardist] Joe Sample, and [drummer] Harvey Mason — these guys were major players in the L.A. funk and jazz world that all played with each other and all were well versed in Latin American rhythms and Latin American songbooks. That was one of the great pleasures and joys of doing this project, is seeing how these different worlds connected. Henry Mancini, who relied on so much of Latin music in his film scores and soundtracks, working with Laboriel and Sample — that is pretty heavy, these are heavy, heavy cats. To have those worlds converge and connect became one of the sub-themes of the book: realizing how intertwined Hollywood studio recording sessions were with the actual club music scenes of jazz and funk, and beyond, in Los Angeles.

Many articles, books, and documentaries have been devoted to “the Wrecking Crew,” the celebrated group of Los Angeles studio musicians that show up in innumerable rock, pop, jazz and funk sessions from the Beach Boys to Elvis to Sinatra to Michael Jackson, but not a lot has been explored about this “parallel Wrecking Crew” which you could (and in many cases still can) call on when you wanted a Latin-inflected sound.

That’s precisely what we tried to address with this book. We have interviews with the top living Latin American session players in L.A. We managed to track down the majority of them. [Radio journalist] Betto Arcos and I did those interviews, and he was really helpful in identifying some of those great L.A.-based players. So we have Abraham Laboriel in there, [Brazilian percussionist] Paulinho da Costa, [Colombian reedman] Justo Almario, [Peruvian drummer] Alex Acuña, [Cuban percussionist] Luis Conte, [Brazilian percussionist] Airto Moreira, and [Mexican-American percussionist] Ramon Yslas. They’re all, save for Yslas, roughly the same generation, and together they played on thousands of recordings in the United States alone. And not just in “Latin” projects, but for major commercial artists like Joni Mitchell, or Madonna, or, in Paulinho’s case, playing on monumental Michael Jackson sellers like Off the Wall and Thriller.

The Latin American Wrecking Crew!

These guys absolutely were the Latin American Wrecking Crew, but interestingly, though they were often brought in to play “Latin music,” for the most part they were playing on everything, because these guys can play everything.

Doing interviews with them was so fantastic — hearing their stories like Justo Almario coming straight from Colombia, to New York, to L.A., and then playing with the Commodores. We wanted to make sure that these stories were out there and how that changes the official record, the history of what we think of as L.A. music. When we were researching the book, we started thinking about the role of Latin American musicians and Latin American music in Los Angeles as a kind of open secret with musicians. Everybody in the session music world knows this fact, that Latin American music is central. And yet, it still feels highly marginalized in the way we talk about music in Los Angeles, and for that matter, the way we talk about “American music” throughout the United States.

Several of the musicians that The Tide Was Always High recovers for Los Angeles musical history are Brazilian. The book includes a great essay by Walter Aaron Clark (“Doing the Samba on Sunset Boulevard,” on Carmen Miranda and the Hollywoodization of Latin sounds) and also a thoroughly original piece by Brian Cross presented as “a speculative history of Brazilian Music into Los Angeles.” Brazil is always a special case when talking about cultural influence: it’s its own thing, but also a central part of the Latin American puzzle.

It’s the Texas of South America.

Absolutely. And, as the really important Ruy Castro books on the development of bossa nova (Chega de Saudade [1990, translated as Bossa Nova] and A Onda que se Ergueu no Mar [2001]) make clear, the relationship between Brazilian music and American jazz has always been a very complex two-way conversation. In Los Angeles, the (barely) unofficial Brazilian ambassador of music has been Sérgio Mendes, who arrived in 1964 for the famous Carnegie Hall bossa nova showcase, headed to Los Angeles and never left or stopped being at the center of the Brazilian musician colony here. Whenever I talk to Brazilian and other Latin musicians, they all say that the first thing they do when they get to Los Angeles is go pay their respects to Sérgio Mendes. He is like the Godfather, or the Pope.

That comes up in literally every interview with Brazilian musicians in the book. They all say that for the most part they came here because of him. Sérgio was an active recruiter and advocate, he opened up this space. After the records he made with A&M Records, he was the guy and everybody talks about him as a power player and as someone who cleared some space for Brazilian musicians to come to Los Angeles and work with him, or work with projects, and that’s when a lot of that kind of cross-bleeding happens of Sérgio Mendes connecting with Quincy Jones and then Quincy Jones becomes somebody who falls in love with bossa and Brazilian music and that’s the Michael Jackson connection. In Brian’s essay, he writes about the relationship between Quincy Jones as producer of Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones as having already done Brazilian records decades before.

And of course, because of Austin Powers (1997), one of Quincy Jones’s biggest hits under his own name ended up being his “Soul Bossa Nova” (1962)!

That “Hollywoodization” of Latin sounds is actually important and something that Brian touches on. It happened to samba before bossa nova. In Brazil, samba is heavily African music, Afro-Brazilian. When it gets exported and enters Hollywood, in part through Carmen Miranda, its “Africanness” is kind of always there, but it’s also not there. Carmen Miranda becomes a de-Africanized version of a woman from Bahia. The world of blackness in the export of this music is a very important topic. When it enters the mainstream of Hollywood, Black Brazil it’s not so present. It’s sonically present but not visually present.

This “whitening” also happened with Mexican brownness in the case of songwriter Agustín Lara and 1930s “Mexican” (euphemistically called “Spanish”) exoticism in architecture and design, as LACMA’s recent Found in Translation shows. Also true about Caribbean music after Xavier Cugat and Desi Arnaz …

It’s what typically happens in the United States. It’s everywhere. And especially in the Americas, it’s rare when an Afro-Latino or Afro-Latina rises to the top financially, successfully in pop music.

Celia Cruz would be the exception.

Yes, she’s the exception. But for the rest, there’s always a kind of de-Africanizing that has to happen. I think of Shakira as a great example. She comes from a city with a prominent African musical community, Barranquilla, and yet there’s a kind of, and I don’t say this as a critique of her individually, but there is a whitening that has historically happened in the industry, particularly in the Americas. A kind of browning — or “beigeing” to use the old term.

There’s a chapter in the book about Latin American dance and its relationship to music in L.A. by Cindy García. Juliet McMains wrote a recent book about salsa in in the United States, and there’s a great chapter on Los Angeles about how salsa dance in L.A. was heavily influenced not by Afro-Caribbeans or Afro-Latinos, but instead was heavily influenced by the way people danced in Hollywood productions. Los Angeles’s version of salsa was so distinct from the East Coast because people were modeling their moves after Hollywood.

It’s the same thing that happens with jazz and R&B turning into big-band and swing. Tango is also one of the most egregious examples, where in Hollywood it becomes this weirdly stylized Valentino thing that is not even remotely close to the complex tango styles in Buenos Aires.

But then the question becomes how do you write about all this or talk about all this without clinging to an authenticity narrative or clinging to a purity narrative, which I did not want to do. I didn’t want to say that “this is bad and this is good” because, especially in a place like Los Angeles, it all gets thrown together, and it becomes a constant negotiation of high and low, and “authentic” Latin American music versus completely “Hollywoodized” versions of Latin America through Disney and lots of other channels. While it’s important to track those obviously, and provide critical histories of those, I think we were careful to not demonize in one direction and praise in another, but actually figure out how do we deal with the middle ground, which is kind of the norm here.

Going back to Sérgio Mendes, he would be a great example of that. He has been one of the most commercial successful Latin musicians here for decades, but his music is deeply uncool for many “hip” listeners.

Sérgio is a great example. Those early Brazil ’66 records were brilliant in terms of genre splicing and him learning the market. Sérgio covered “For What It’s Worth,” the Buffalo Springfield song about the Sunset Strip riots in 1966. It’s a really beautiful, kind of awesome, slow funk song. How perfect is that? It’s him saying, “Come on — I’m an L.A. artist, so I can do a Brazilian funk version of the Buffalo Springfield song about white kids rioting on the Sunset Strip and that’s my purview, and that can be part of my songbook and I can cash in on it, but also make something new.” And I love his songbook!

Speaking of songbooks, you also rescue the figure of Trini Lopez. One could argue that the unstoppable rise of the DJ killed that type of entertainment in Los Angeles — the super-professional live bands of session players that could play all the big hits in their own style. Los Angeles in the 1960s had frontmen like Trini Lopez, Johnny Rivers, José Feliciano, who specialized in what today we would call “covers.”

Trini Lopez was, as he was often called, a human jukebox. At PJ’s, he would churn out all the hits of the day and do his own Latin spin on them. That’s something that I really like. I have a soft spot for that modality.

Before we move over from Brazil, we have to talk about Carmen Miranda. In a sense, the Carmen Miranda project of Americanizing (or Hollywoodizing) Brazilian music in the 1940s is a good example of an L.A. modernist project.

I completely agree.

In the Busby Berkeley sense.

Absolutely! Hollywood’s role in that is big. We did a tribute to Latin American composers in Hollywood as part of this project at the Getty where we put together a big band and we did songs by Esquivel, Agustín Lara, María Grever, Lalo Schifrin, and Ary Barroso. Part of that show was a claim about modernism, making the claim that these are modernist strategies that are not ever talked about as such, or rarely.

An image that I always think about is the iconic photographs of the Koenig Case Study Houses, and all these iconic Julius Shulman shots of midcentury Los Angeles with upper-middle-class or upper-class white couples in their perfect midcentury outfits, and the Eames chairs, and all the right furniture, and they always have a hi-fi. And nine times out 10, what’s on that hi-fi? It’s always Pérez Prado records or Esquivel records! There’s a soundtrack to midcentury modern and it’s often Latin American–influenced, but it’s been left out, I think, of the narrative of what counts as L.A. modernism. The Tide Was Always High makes the argument that Latinos and Latin American culture are a kind of “ghost in the machine” of L.A. modernism. It is always there haunting it, but it’s rarely talked about with the centrality that it deserves.

It’s like a musical counterpart to the “Mayan” influence in modernist architecture in Los Angeles.

This has been a big part of the work of Jesse Lerner, a curator, writer, and filmmaker who did a series on Latin American experimental film for Pacific Standard Time, called Ism Ism Ism / Ismo Ismo Ismo. And he co-curated the exhibit about Disney in Latin America with Rubén Ortíz Torres. Jesse is an amazing thinker and he wrote a great book called The Maya of Modernism, and it’s all about the role of the “Maya” in the modernist imagination, from the Ennis House to the Aztec Hotel in Monrovia, which is actually Mayan-inspired design but it’s called “Aztec.”

With a soundtrack by Yma Sumac!

We had an essay about Peruvian, Incan singer Yma Sumac in the book and we did a concert paying tribute to her at the Hammer. The singers had to figure out how they were going to do this, and often they would ask for lyric sheets, of which there aren’t any. One of the singers emailed, “Can you send me the original quechua lyrics?” And I said, “I don’t think they’re in quechua.” And she started thinking — and she’s from Mexico City — and she said, “I think they are.” So we started poking around, and according to the only book that’s been written about Yma Sumac they are wordless. It’s not quechua. And she said, “Oh yeah, but everything is wrong in that book and he makes claims that she’s singing this and she’s not singing that.”

Was it quechua?

It went back and forth and we ended up with: “It’s not quechua, but it could be quechua, but it could not be, and it’s wordless and it isn’t”! And that was part of what was happening, that there was this open play with exporting manufactured authenticity, and creating this commodified image in the case of “Yma Sumac,” of the Incan Princess who ends up at the Hollywood Bowl or Capitol Records and people are buying her records because she’s supposedly singing in quechua, when in fact, she might just be making words up.

But it doesn’t at all detract from the extraordinary arrangements and the extraordinary talent of her as a singer and performer, so it was really interesting and instructive to watch contemporary artists grapple with that and figure out how they perform themselves in relationship to that.

I wanted to bring up the issue of Latin musical communities in Los Angeles and gentrification. For example, the Boyle Heights community.

I don’t live in Boyle Heights and I cant speak for anyone in Boyle Heights and so I leave those debates to the folks who are rooted in their community and are doing what they believe is the important work for the sustainability of their community and the sustainability of their histories. And I support that 100 percent.

The Boyle Heights of late 20th and early 21st centuries is not the Boyle Heights of the 1950s and ’60s, and it’s important to not confuse those, they are different histories. The Boyle Heights that produced so much of the R&B and early Chicano Boogie Woogie, the Pachuco boogie music of the ’50s, was very different from the Boyle Heights that emerges post-1980s, where Boyle Heights goes from being one of the most multiethnic, multiracial, multilingual immigrant neighborhoods in the country to being one of the least, to become predominantly a Mexican neighborhood. Those are different histories, and I think that we have to approach them very differently and I always try to resist a little bit this, “Oh, it used to be an immigrant neighborhood, and it used to always welcome immigrants.” Well, that’s true, but it’s a different political and cultural climate right now.

Although gentrification and redevelopment are constants in Los Angeles.

These are real issues. I always remind my students that people are fighting because they feel that something’s at stake and there’s a real visceral fear that something is being taken away, and we have too much history in Los Angeles where we’ve seen communities be displaced. We’ve seen people being bulldozed, literally, by corporate, city, commercial entertainment developments, and I don’t think we can quickly turn a blind eye to it. So I think it’s really important.

I did a big project from the Phillips Recording Company a few years ago, where we were looking at the history of this very important record shop and music store that was in Boyle Heights from the 1930s to the 1980s. Latino, African American, Japanese American — it’s really this idealized, archetypal example of that story. Even in doing that project, I started worrying about what that nostalgia was about. Why was I and why were so many of the people that I knew so invested in that earlier Boyle Heights story and less invested in the contemporary Boyle Heights story? Where are all the histories of what’s been happening since the ’80s in Boyle Heights? And that’s been told largely through Chicano historians, it’s been largely told by Chicano activists and Chicano musicians. The rise of son jarocho from Boyle Heights as a community force, the rise of Chicano alternative music or rock in español — those histories are being written right now and I think that’s really important and I’m looking forward to 10 years from now what views we have backward to this moment.

It’s really easy to talk about — especially for a white secular Jewish guy — to cling to these old stories and I want to call myself out, I wanna check myself and others on it, to say, “What are we not talking about if we keep talking about the 1950s?” I’m talking about the continual inequalities of Latino life in Los Angeles, the continual transformation of the public spaces of Los Angeles, the ongoing patterns of redevelopment.

I also wanted to bring up the role of thrift stores and record collecting in the survival of a lot of this culture.

Physical thrift stores or digital ones like eBay?

Both, I guess.

These days I’m usually pretty target-driven. My first step: EBay. Set up an eBay search. Second step: Set up a Google News alert. And then start looking for the specific thing you’re looking for. Because pre-eBay I would spend a lot of time traveling, a lot of time driving, even flying to thrift stores in neighborhoods where things might be located and it would always be a crapshoot, you know? You might find something you’re looking for and you’d find a lot of things you were not looking for which might not be useful for the project. I find that online searches can be good at helping you target things. Most of the things I’m interested in are not in official archives, in formal archives, and so it’s hard to find them, but eBay can be very, very helpful.

Don’t you worry about the future of these artifacts you write about?

I do. But that’s another difficult question. Institutionalizing it could take on all kinds of different shapes. We’re just starting at USC to think more about this in terms of Southern California collections. Everyone is getting rid of their records. After I did the Jewish album cover book, that was almost 10 years ago, and to this day I get at least a few emails a year from somebody saying, “I live in blah blah blah and my uncle just died, or my father died and I got a box of Yiddish 78s and I don’t know if I should throw them in the trash or, you know, can I send them to you?” I don’t want them all, though! Part of me always wants to say, “Yeah! Send them to me,” because I do want them all. I want it all in theory, but I don’t want it all in dust and boxes and there’s so much stuff.

And you can’t preserve it all?

We can’t. And so the question becomes: “What do you preserve? And why?” That’s why I think the role of the curator and the role of the archivist, is really tricky.

Music Man Murray, who had a record shop, when he was dying, everyone was trying to figure out what to do with his collection and who would buy it. And I was trying to convince USC to buy it. And we worked really hard to figure out investors, and things, and it became this big question of like, “Well, its 400,000 objects. Where are we going to put that?” To buy that is actually the cheap part. The expensive part is long-term storage, digitization, ongoing preservation. It’s super expensive. And then what? We have four warehouses full of 400,000 things. Who’s going to staff it? Would people visit it? Who’s going to index it and do the metadata? These are really important questions.

It’s much harder than the Library of Congress picking 25 films a year to preserve.

It is. But I understand why and I am very sympathetic to that method. My sheet music project with the L.A. Public Library involved working on an archive of 100,000 pieces of sheet music and songbooks and figuring out which 200 of them are the ones that should be in a book and be our primary storytelling devices.

Don’t you feel you’re killing part of history when you choose something over something else?

Oh, I know I am. That’s why in all my projects I am careful to say, “This is not an official version, this is my version, in this book, in this project.” And if you, Gustavo, went and did this, it would be, and should be, a totally different book.

I had to become very comfortable with the inherent failure of all my archivist projects. Even this new book, there’re so many things that aren’t in there and there’re so many different ways of telling this exact same story, it can keep you up at night. It does keep me up at night.

But it really can make you crazy if you worry about it all the time, and then you never write the book.

¤

Gustavo Turner is a writer and photographer in Los Angeles. Instagram: @gustavoturner and Twitter: @eyecantina.

The post The Latin American Wrecking Crew: A Conversation with Josh Kun appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2phDDcv

0 notes

Text

The Houston Astros started from the bottom, and now they’re World Series champions

The Astros were the butt of baseball’s jokes not that long ago. Now they’re having a whole lot of fun.

LOS ANGELES — The Houston Astros were a joke. A literal punchline to whatever baseball joke you could come up with. They were “The Aristocrats!” of baseball, something you could say at the end of a long, drawn out explanation of utter and total baseball incompetence. Say the word “Astros,” and you would get laughs.

The Houston Astros are World Series champions for the first time in their 56-year history.

It took skill, luck, talent, and smarts, which is what it took for every other championship team before them. The 2017 Astros were an incredible collection of talent. They were found talent, acquired talent, developed talent, and bought talent. They won 101 games in the regular season, and then they won 11 games after that. When future generations look back at the 2017 season, they won’t think, “Now how did that happen?” It makes sense. What with the talent and all.

But I want to talk about how bad they were if that’s okay.

I can’t stop thinking about this.

... not a single, solitary Nielsen household tuned in for as long as a few minutes in any given quarter-hour to watch the Astros lose to the Indians for their 105th defeat of the year.