#this was originally number 1558!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

yeah! woo! fuck it up kirby! it's [kirb2k]!!!

#kirby#kirb2k#swearing#gif#music#macarena#audio by los del rio#my art#this was originally number 1558!#from october of 2022#for some reason to sync it up properly I had to save it at 15 fps and then slow it down to 1/4 speed lol#I gotta wait till my sibling-in-law leaves to set up the blaze campaign tho cuz they're resting in the room that has my password notebook :T#favorites

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

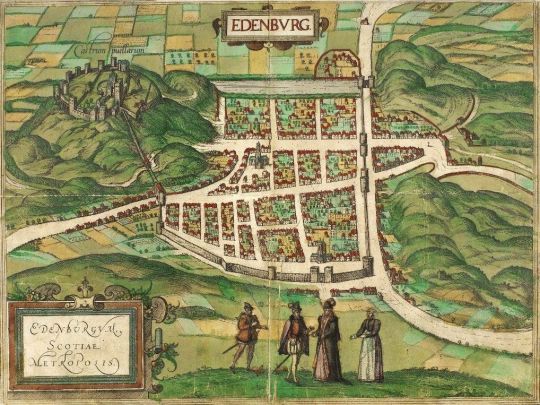

14th April 1582 saw a Charter granted by James VI which would lead to the foundation of University of Edinburgh in 1583.

The founding of the University of Edinburgh can be traced back directly to Robert Reid, Bishop of Orkney and Abbot of Kinloss Abbey. On his death in 1558 he left significant funds for the founding of a seat of learning in Edinburgh, and these formed the basis of the university's endowment. The University was established by a Royal Charter granted by James VI in 1582, making it only the sixth university to be founded in the British Isles, and the fourth in Scotland. Funding came both from the endowment left by Bishop Reid and from the City Council.

In in the 1700s the University of Edinburgh was at the heart of the wide ranging revolution in thinking now known as the Scottish Enlightenment, a revolution that led the French philosopher Voltaire to say "we look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization". Despite this, until the start of the 1800s, the university had no purpose built buildings, instead occupying a wide variety of rented accommodation. In 1827 this changed with the opening of the Old College, built on South Bridge by the architect William Henry Playfair to plans by Robert Adam.

More new buildings followed, including a new Medical School designed by Robert Rowand Anderson which opened in 1875, and the magnificent McEwan Hall, which was completed in 1880. The university is now also responsible for the oldest purpose-built concert hall in Scotland (and the second oldest in use in the British Isles) St Cecilia's Concert Hall, built for the Edinburgh Musical Society 1763; and in 1889 it opened Teviot House, the oldest purpose built Student Union building anywhere in the world.

The origins of the university library date back to a collection formed in 1580, two years before the university itself was founded. It has grown to become the largest university library in Scotland with over 2 million periodicals, manuscripts, theses, microforms and printed works. It is housed in the main University Library building in George Square, designed by Basil Spence and one of the largest academic library buildings in Europe. There are also a number of more specialised faculty and departmental libraries. In 2011 the previously independent Edinburgh College of Art became part of the university.

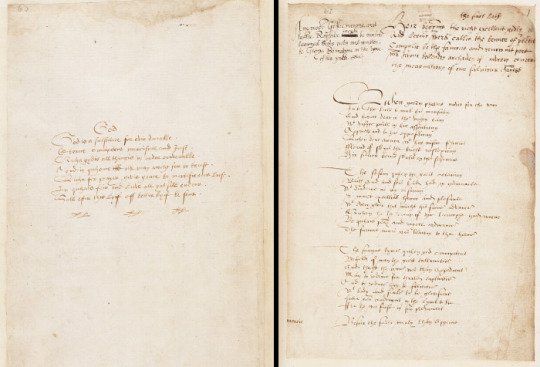

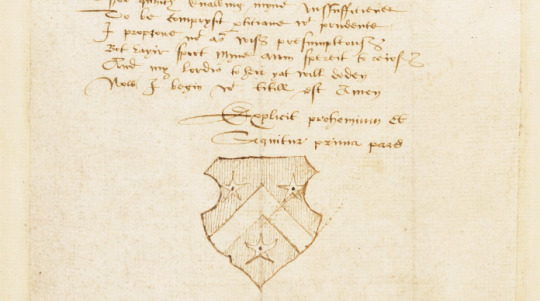

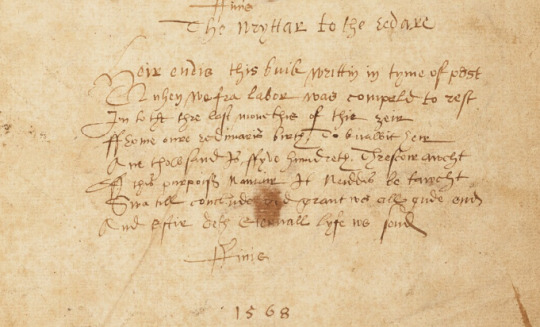

The pic shows the charter which the University holdds, the seal itself is not present. Assumed to have been in the possession of the city from the inception until loaned to the University in November 1995.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why did Elizabeth I do as she did with England's religious settlement?

So the thing to keep in mind about England's religious settlement is that it was constantly changing throughout the English Reformation, partly due to the monarch at the time, but also in significant part due to the changing environment of the time. The England of the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536 was a very different place from the England of 1547-9 when the Protestant reformers under Edward VI made their move against Gardiner, which in turn was a very different place from the England of 1553-1555 when Mary executed the very politically tricky reconciliation with Rome, which was a very different place in turn from the England of 1558 when Elizabeth I came to the throne.

In part because he shows up much less in pop culture depictions of the Tudors, there is a tendency in the popular historical imagination to skip over the seven year reign of Edward VI and jump from Protestantism under Henry to Catholicism restored under Mary to Elizabeth. This is a mistake for a couple reasons: first, as I've said, the Henrician period is really damn complicated and is hard to characterize as definitively Protestant or Catholic; second, the Edwardian period while relatively short saw really profound changes both in religious governance (in this period, the Church of England was pretty clearly not just Protestant but strongly Lutheran, which isn't something you could have said before or after) and in English religious culture.

Namely, as you can see from the map above, the Edwardian period really transformed English Protestantism from a purely elite project to one that, while still very much driven from above (the Book of Common Prayer was hardly a populist measure), had a popular constituency. This isn't to say that England was majority Protestant (yet), but you can see a strong regional divide with Protestantism having its base in London, the Home Counties, and East Anglia, and then Catholicism retaining its traditional strength in the North of England (which not coincidentally is where the Pilgrimage of Grace had originated from).

So when Elizabeth I ascended to the throne, she inherited a kingdom that was fairly evenly religiously divided. To that end, a lot of her religious policies were aimed at trying to steer a middle path: the Church of England would once again be independent of Rome, there would be Edward's Book of Common Prayer and other Lutheran elements of doctrine, but a lot of the outward forms of worship that were associated with Catholicism to keep that faction happy.

At the same time, Elizabeth was very much a monarch of the Reformation, a time when no one on any side believed in religious toleration. Hence the Elizabethan settlement making it illegal not to attend weekly services at the Church of England, at the penalty of crippling fines for "recusants." This policy, along with a no tolerance policy towards the existence of Catholic priests in England and a number of plots and conspiracies linked to said priests, did pretty rapidly reduce the number of English Catholics to a tiny minority, although as I've said, it ultimately failed to end disagreements within the Church of England that would eventually give rise to the Puritans.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ryu Number: The Sengoku Period/Romance of the Three Kingdoms characters of Warriors Orochi 4 Ultimate, Chapter 2, Part 3

The Young Dragon Obeys the Goddess

Kunoichi

Sanada Yukimura

Takeda Shingen

Fūma Kotarō

Uesugi Kenshin

Sanada Nobuyuki

-

Bao Sanniang (鮑 三娘, Hou Sanjou): Fictional wife of the fictional Guan Suo. In folklore, she’s a warrior who Guan Suo hears tell of and challenges to a spar; when he defeats her, she proposes. After her husband dies in battle, she guards Jiameng Pass until her death. Or maybe dies defending it. Or dies of illness there. That’s folklore, my dudes.

Chen Dao (陳 到, Chin Tou): Served Shu. Little is known about him, but he was the leader of one of Liu Bei’s elite units. Active from the 190s to the 230s.

-

Guan Ping

-

Guan Suo (關 索, 関 索, Kan Saku): In Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a fictional son of Guan Yu who served Shu. He is often folklorically described as being handsome and having many wives.

Guan Xing (關 興, 関 興, Kan Kou): Son of Guan Yu and younger brother of Guan Ping. When he became an adult, he became an official in Shu, but died some years later. Romance of the Three Kingdoms gives him a larger role and has him in more of a warrior role; he kills Pan Zhang (the Wu general who captured Guan Yu) and kills two former Liu Han whose defections to Sun Quan led to the event.

Guan Yi (關 彝, 関 彝, Kan I): Grandson of Guan Yu and son of Guan Xing. Some sources say he died after Shu’s 263 fall; in Romance of the Three Kingdoms he’s killed by Wei soldiers during Zhong Hui’s attempted rebellion in 264.

-

Guan Yinping

Liu Bei

-

Liu Ning (劉 寧, Ryuu Nei): Shu General. In the 221-222 Battle of Xiaoting, Liu Bei’s attempt to take back Jing Province from Wu, Liu Ning was defeated and forced to surrender.

Wu Lan (吳 蘭, 呉 蘭, Go Ran): Served Shu. Killed during the Hanzhong Campaign in 217, either in battle by Cao Hong and Cao Xiu’s forces, or after fleeing by the Di leader Qiangduan (the Di were an ethnic group of western China).

Xingcai (星彩, Seisai):Empress Zhang (張 皇后, Chou Kougou) was the daughter of Zhang Fei, who became an Imperial Consort of Shu emperor Liu Shan. She became empress in 238, after the previous empress, her elder sister, died. After Shu was conquered in 264, she joined Liu Shan in Luoyang. Koei gives her the fictional identity of Xingcai.

Zhang Bao (張 苞, Chou Hou): Son of Zhang Fei who died early. In Romance of the Three Kingdoms, he fights Guan Xing because he wants to lead forces into the 221-222 Battle of Xiaoting and Liu Bei has to break them up. In Zhuge Liang’s Third Northern Expedition (in 229), he dies of injuries from falling into a gully.

Zhao Yun (趙 雲, Chou Un): Served Shu. Originally served warlord Gongsun Zan, and there met Liu Bei, who was sheltering under Zan at the time. Continued his service under Liu Bei’s son Liu Shan and participated in the first of Zhuge Liang’s failed northern expeditions in 228. Died 229. In Romance of the Three Kingdoms he is one of the Five Tiger Generals of Shu. A popular folktale says that he was never scarred in battle, but died of fatal hemorrhage when his wife playfully pricked him with a pin.

Showdown with the Demon King

Sanada Yukimura

Ii Naotora

Sanada Nobuyuki

Akechi Mitsuhide

Gracia

-

Ishida Mitsunari (石田 三成): Born 1560. Served under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. After Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s death in 1598 he was in a very politically unstable position, not helped by Tokugawa Ieyasu’s willingness to ascend to power himself despite being nominally one of the regents of Hideyoshi’s heir. Mitsunari formed a coalition to stand against Tokugawa Ieyasu, culminating in the 1600 Battle of Sekigahara, with Mitsunari’s Western Army against Tokugawa’s Eastern Army, but Mitsunari’s unpopularity with potential allies saw his loss. He attempted to escape but was captured and killed.

-

Kuki Yoshitaka

Yamauchi Kazutoyo

-

Mori Nagayoshi (���長 可): Born 1558. Older brother of Mori Ranmaru. Served Oda Nobunaga, then Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Shot and killed at the 1584 Battle of Komaki and Nagakute.

-

Mori Ranmaru

Niwa Nagahide

Nō

Oda Nobunaga

Saitō Toshimitsu

Shibata Katsuie

-

Takigawa Kazumasu (滝川 一益; possibly Takigawa Ichimasu): Born 1525. Served Oda Nobunaga. After Nobunaga’s death, he opposed Toyotomi Hideyoshi alongside Shiba Katsuie, siding with Oda Nobutaka, but was defeated and submitted to Hideyoshi in 1583. After performing suboptimally at the 1584 Battle of Komaki and Nagakute, he retired and became a monk, and died 1586.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣 秀吉; also “Toyotomi no Hideyoshi”, i.e. Hideyoshi of the Toyotomis): Born 1537. Rose from a peasant background to become one of Nobunaga’s most prominent retainers. Famously built a castle on the edge of enemy territory in a very short amount of time in order to gain an advantage in the 1567 Siege of Inabayama Castle against the Saitō clan. After Nobunaga’s death in 1582, Toyotomi was in a strong position politically. He came into conflict with Shibata Katsuie and Oda Nobutaka when it came time to determine Nobunaga’s heir (being allied with Oda Nobukatsu instead), but prevailed. He completed the unification of Japan under a single rule that had been started by Oda Nobunaga. Later, he attempted a Japanese conquest of China through Korea, but this turned out to be a failure that lost him political strength. When he died in 1598 the invasions were called off. He declared his son Toyotomi Hideyori as his heir and entrusted his care to a Council of Five Elders, but that Didn’t Work Out and Tokugawa Ieyasu (one of the elders) ended up rising to power instead.

-

Guan Yinping

Liu Bei

-

Cao Pi (曹 丕, Sou Hi): Second son of Cao Cao and first emperor of the state of Wei. He succeeded his father when Cao Cao died in 220. In the same year, he deposed Emperor Xian, finally making the Cao explicitly emperors. Though Sun Quan was nominally one of his vassals, he broke ties with Wei, declaring independence in 222. Died 226.

Cao Zhen (曹 珍, Sou Chin): Wei general who worked with Zhuge Dan (back when Dan was still not-rebelling). In 255, he was killed in Gaoting in a clash with Wu forces who were receiving the defecting Wen Qin.

-

Guo Huai

-

Lady Zhen (甄夫人, Shin-Fujin; referred to in Warriors Orochi 4 as Zhenji/甄 姬/甄 姫/Shin-Ki, which means approximately the same, unless you count that second 姬/姫 character as a forename instead of an affix, which I cheerfully refuse to do because that means I can’t connect this Lady Zhen with other generic non-specific Lady Zhens): Born 183. Well-read and socially adept from a young age. Married Yuan Xi, son of warlord Yuan Shao, though Zhen lived apart from him in the administrative center of Shao’s territory. In 204, after Yuan Shao’s death, Cao Cao’s forces were able to take control of this territory, and Cao Pi met Zhen and married her. She kept the peace among the other wives and encouraged Pi to take more concubines. However, after Cao Cao died in 220 and Cao Pi became emperor, his favor toward other concubines led Zhen to complain; for this or some other unknown offense, Pi responded by forcing her to take her own life in 221. Her son Cao Rui would become the next emperor of Wei.

Wen Hu (文 虎, Bun Ko): Son of Wen Qin and brother of Wen Yang. After Sima Shi deposed Wei emperor Cao Fang and replaced him with Cao Mao in 254, Wen Qin started a rebellion, but this was quickly suppressed and he and his family were forced to defect to Wu. When Wei general Zhuge Dan rebelled against Sima Zhao in 257, the Wen family was among those sent to support him. However, the relationship between Wen Qin and Zhuge Dan deteriorated, and when Zhuge Dan had Wen Qin executed, Wen Hu and Wen Yang fled back and surrendered to Sima Zhao.

Wen Yang (文 鴦, Bun Ou): Born 238. Son of Wen Qin and brother of Wen Hu. After Zhuge Dan’s rebellion was defeated, Wen Yang went back to serving Wei, and after its formation, Jin. However, in 291, he was falsely accused of being involved in a failed rebellion by Sima Yao, Zhuge Dan’s grandson (not the emperor Sima Yao—different hanzi), and was executed along with his family

Yang Xin (楊 欣, You Kin): Served Wei. Assisted Deng Ai in the 263 conquest of Shu. Continued serving Jin. Died in 276 fighting against the nomadic Xianbei people.

-

Zhuge Dan

0 notes

Text

WHAT IS THE BEST WAY TO IMPROVE MY CREDIT SCORE

WHAT IS A GOOD CREDIT SCORE?

Lenders want to anticipate the likelihood of a borrower to repay a loan within the stipulated period. Therefore they use decision-making tools that assist in risk assessment. It is important to have a good credit, it is the governing factor in qualifying for a loan, amongst other factors. One’s credit score is generated upon request by the lender. Loan terms vary according to your credit score. Financial goals achieved have major impact on the borrower’s credit score. But just what is a good credit score? Well, before answering this question, it’s important to first understand what constitutes a credit score

WHAT AFFECTS YOUR CREDIT SCORE?

It is the elements contained in your credit report that affect your score. Such elements include:

Your total debt.

Loan payment history.

The rate of credit utilization.

Credit report inquiries submitted.

Civil judgements, bankruptcy and other public records.

The number of credit accounts newly opened.

The number and type of credit accounts one has, and how long they have been in existence.

However, there is information that credit scores do not regard such as:

Age of the borrower.

Origin, race, marital status, gender or religion.

Place of residence of the borrower.

Employment status and history and salary (although lenders may want to use such information for approval purposes).

Consumer disclosure inquiry made by the borrower or promotional inquiry made by lenders.

WHAT IS THE BEST WAY TO IMPROVE MY CREDIT SCORE?

Sometimes when reviewing your credit scores, you may discover that they are not as satisfactory as you would want them to be. Your credit report contains all activities related to your credit flow, showing your responsibility in regards to your credit management. There are ways you can take charge of your financial future if you are equipped with information like:

Improving your credit history with use of credit cards that are secured.

Making choices that improve the credit score.

The role of credit repair services to your credit.

Restoring and restoring one’s good credit after suffering major setbacks like divorce or death.

Monitoring your credit movements and learning on ways to help control them.

WHAT IF YOU DO NOT HAVE A CREDIT SCORE?

There are ways in which one can establish credit. Such ways include;

One must have a source of income that is adequate and if they are underage, they must have a consigner.

Open an account with the bank with a credit limit.

Open a secured credit card.

When applying for loans, there is no need for minimum credit score, but you can be disqualified when you have a low credit score. You will have to wait for your credit to improve for you to get the best rates. However, some companies servicing mortgages issue guidelines to borrowers with low credit scores to help them acquire their desired loans. There are facts about credit scores that are common. Credit reports do not contain credit scores, the scores are calculated upon request only. They change with time based on one’s credit movements. In the case of joint accounts, credit reports are contained in the credit history. However, when one gets married, the accounts of the spouses remain independent.

Contact Us:

Address - Atlanta, GA

Email - [email protected]

Phone - (800) 531-1558

Website - C4 Credit Solutions

Blog - WHAT IS THE BEST WAY TO IMPROVE MY CREDIT SCORE

0 notes

Text

For sure we have all heard the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” and find its melody to be nostalgic. But at the same time, many of us have said the lyrics are nonsense, not understanding the meaning of the seemingly random "gifts" of each day. I grew up as a child singing the Perry Como version of the song , and I thought that the words of the song were silly, which sounded as if talking about love and lovers with a bunch of quirky gifts. Years later though, I was 13 or 14 years old, I read the song’s real significance and history – it was a Catechism of the Catholic Church hidden in the form of Christmas carol.

It was dark times in England for our beloved early Catholics, from 16th to 19th centuries (1558-1829). The descendants of the present-day British royal family instituted its own ‘church’ that runs up to this day in different countries. Immoralities and dreadful grave violence occurred. Their king declared himself a ‘pope’ and passed on the heresy to his children who then became rulers. Converts and monasteries were closed and robbed. There was a Prime Minister-equivalent politician who refused to obey the evil monarchy, so he was beheaded and died as a martyr for Jesus and later declared a Saint. Being a Catholic became a crime. Priests who performed Sacraments on Catholics were punished by death. The practice of the Roman Catholic faith, either public or private, was banned. Catholics were gruesomely killed by hanging, beheading, disembowelment while alive, tied and torn into pieces, suffocation, burning. The faithful Catholics both poor and wealthy risked their homes, lives, and everything just to attend the Mass and have their children baptized. Rich families built hiding places and holes for priests and Catholics, but many of them were raided and murdered.

The song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” was claimed as written by the English Jesuits to educate the young Catholic people in the doctrines, and tenets of the faith. With the background, there was a need for secrecy from the persecutors. They used mnemonic numbers to simply help the laypeople in remembering the basic facts and teachings.

Liturgically, the Church celebrates Christmas for ’12 Days’ that starts on Christmas Day and ends on the Feast of the Epiphany. Within the period, there are important feast days that aid us going deeper into the celebration of Our Lord Jesus Christ’s Nativity to understand His Coming as the means of our salvation.

I enjoy sharing this knowledge and origin of the Christmas song with you. The real essence of Christmas is whole in one song. When we hear “The Twelve Days of Christmas” again, may our hearts be filled with more love for Jesus and His Church, reminiscing the song’s true meaning, accepting the truths of the Catholic faith.

🎵On the fourth day of Christmas

my true Love sent to me

4 calling birds

3 French hens

2 turtle doves

& a partridge in a pear tree🎵

❣️🎄

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

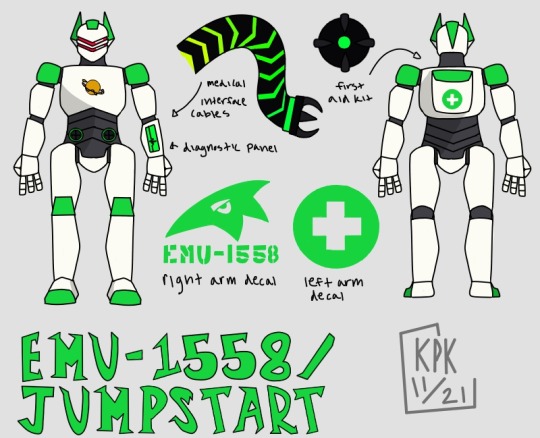

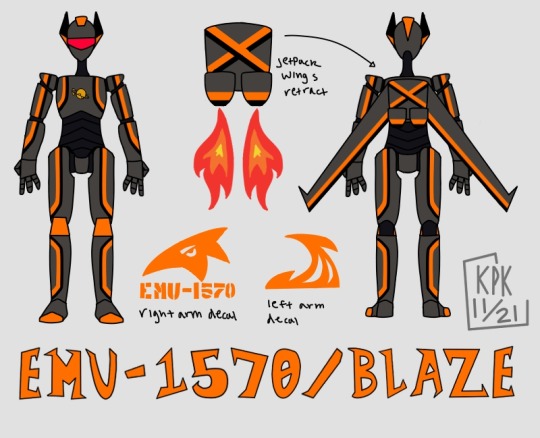

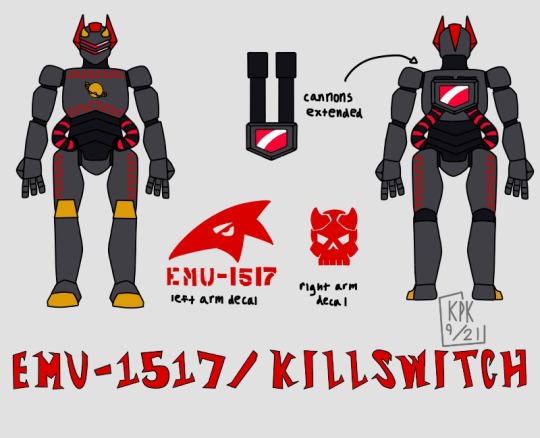

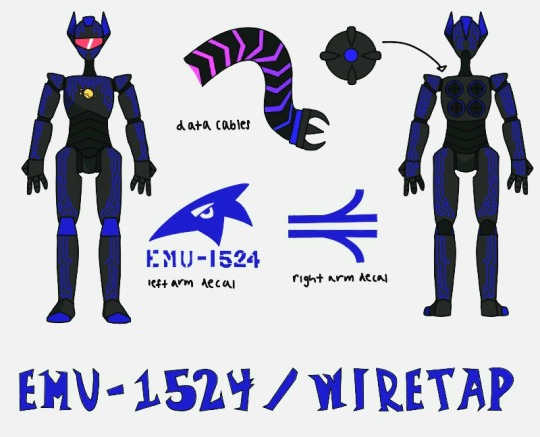

#art#digital art#ocs#original characters#sci fi ocs#mars troopers#emu-15#emu-1558#jumpstart#emu-1570#blaze#emu-1568#just realized i gave js and tc the same number lmao#thunderclap#emu-1517#killswitch#emu-1524#wiretap#robots

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ten Most Terrifying Women of Folklore

1) Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary is famous as an alcoholic drink and a game. The game's rules are simple: turn off the lights, look into a mirror, and say her name a number of times. With that, she will appear in the mirror in all her terrifying glory and tell you your future...or kill you. There are a lot of different stories and theories about who Bloody Mary is. Most scholars believe that the legend stems from the original Blood Mary, the English queen from the 1500's. Her name was Mary Tudor, daughter of king Henry VIII and sister to the famous queen of England, Elizabeth I. Mary's story is a far cry from the fantastical tales of queens and princesses most girls grow up fantasizing about. She was originally born and raised like European princesses of her day, but that changed when she was seventeen, when her father made the catastrophic move of breaking with the Catholic Church and forming the Church of England then divorcing Mary's mother, Katherine of Aragon. Mary was exiled from court, stripped of her title as princess, removed from the line of succession, and, worst of all, she was declared a bastard. Henry quickly married Anne Boleyn and the couple had Elizabeth. But then he discarded Anne and had her beheaded then married Jane Seymour, and they had a son, Edward. For years, Mary was ignored and poorly treated as an illegitimate, Catholic daughter. Understandably, Mary turned out quite embittered. Despite the steps taken to keep her out of the line of succession, when Henry and Edward died, Mary ultimately became the next ruler of England in 1553. As queen, Mary worked hard to return England to Catholicism. In order to accomplish this, she had hundreds of Protestants - men, women, and children - arrested and burned at the stake as heretics. It was very brutal. This is why she became known as 'Bloody Mary'. Mary's reign lasted for five years. She died in 1558, childless. She was succeeded by her younger Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth. As destructive as her religious persecution was and as dark as her reputation and story is, Mary was not exactly a crazy, evil tyrant, and she is far from England's worst monarch. Her persecution of Protestants was nothing new to Europe, nor England, as mass executions, like burning, were very common since the dark ages. A number of England's monarchs were involved in the same practices. And even though Mary's reign suffered great losses and damages, like losing Calais to the French, it also had a lot of good, such as a step forward in women's rights as Mary made it law that women could rule in their own right like kings. Ventures to the New World and other foreign countries were launched by Mary's administration and she expanded the arts and academics in England. But, in the end, Mary's sins and failures were and still are the biggest take-away from her life. It's quite plain to see and most plausible that she was more vilified and set apart from the other monarchs before and during her time because she was a woman. Back then, and still to this day, women were not accepted in positions of power. Women, even noble women, were expected to be submissive, delicate, and powerless as daughters, wives, and mothers. So a woman as a reigning monarch was still very foreign in Renaissance Europe. And Mary was the very first reigning queen in England's history. So if she messed up in any way or had any faults, it was used against her. Mary's executions of the Protestants were normal for kings, but totally unaccepted for a woman, queen or not. So it's safe to say that Mary wasn't just reviled for killing Protestants, she was also reviled for being a woman who killed Protestants.

2) La Llorona

Latin culture has many stories and legends to offer. One of them is la Llorona, the Weeping Woman. She is the most famous of ghosts in Latin folklore. She is well-known in all Latin countries, but she is most connected to Mexico, its history, and its culture. La Llorona's origins date back prior to the Spanish Conquest within Aztec mythology and lore. It is said that one of the omens foretelling the indigenous people of Mexico of the coming destruction was a woman crying out for her lost children. She also resembles two Aztec goddesses, Cihuacoatl and Chalchiuhtlicue, and is quite likely also inspired by Malinche, the infamous translator to the conquistador Hernan Cortes, who was said to have produced children with her. La Llorona is a ghostly woman who wanders at night, most of the time near rivers, lakes, ponds, highways, roads, or anything similar to any of these. She is often seen as a woman with long, black hair and wearing a white dress and sometimes a veil. But you can always tell she is near when you hear a woman crying. She is always, always crying, which is why she is called the Weeping Woman. Like most legends, she has many origin stories. But the most popular story goes like this: she was once a woman named Maria, who was a commoner of indigenous descent in New Spain (what Mexico was originally called when it was taken over by Spain). Although she was very poor, she was exceptionally beautiful. She was said to be the most beautiful woman in that part of the land. Her beauty soon caught the eye of a traveling wealthy Spaniard. They had a whirlwind romance and Maria was swept off her feet. When he proposed, she said 'yes'. However, because she was poor and half-indigenous, she was not too welcomed by her new husband's family. The couple set up home in a lovely ranch house and had a number of children, whom they adored. Everything seemed perfect and Maria was happy. Years later, her husband went on a business trip, as he usually did, but this time he didn't come back. Maria soon found out what had happened: her husband had left to marry a Spanish noblewoman. Because she was mixed race, their marriage wasn't regarded as serious. Maria was devastated. So much so that, in the throes of her heartbroken rage, she took her children to the nearby river and drowned them there. When she regained her senses, it didn't last long when she realized what she had just done and she was overcome by grief and remorse. Maria cried out for her children in her misery then threw herself into the river, where she drowned. Maria didn't move on to the afterlife and is trapped in purgatory. Ever since, her spirit has roamed the land of the living, searching and mourning her deceased children. Tragic as she is, she's also feared. It's said that la Llorona will abduct children she comes across and drown them as she did with her own children so that they will take their place. For this reason, adults tell children to beware of la Llorona.

3) Kuchisake-onna

Japan is home to many ghosts and creepy creatures, but one of the more recent and most unnerving is Kuchisake-onna, the Slit Mouthed Woman. She roams the streets and appears as a normal Japanese civilian. She's beautiful and wears a long coat and a surgical mask, which can easily be passed off as it is quite the norm, especially in Japan, for people to wear masks when they're sick and trying to avoid getting sick. However, when she approaches you, she asks you, "Do you think I'm pretty?" When you answer her, she pulls down her mask and reveals a nightmarish Glasgow smile, hence why she is called the Slit Mouthed Woman. Some say she got her scar from a botched operation, but the most popular story is that she was the wife of a samurai centuries ago. When her husband accused her of having affair, he slashed her mouth wide open from ear to ear, tarnishing her beauty and making it so that no one would want her. So, when her spirit encounters someone on the street, she will ask them, "Amy I pretty?" When she pulls down her mask to show her scar, she will repeat the question. If you say 'yes', she will mutilate your mouth in the same fashion as hers. If you say 'no', she will kill you. You cannot avoid her or escape her, so the best option is to give her an ambiguous answer like 'so-so' or throw change or candy at her, or maybe even tell her you have somewhere else to be to which she will leave you alone out of politeness.

4) Lilith

Before Eve, there was Lilith. In the Judaic faith, she was Adam's original wife. Lilith was not content with being a submissive wife and questioned this order. Her rebellion resulted in her leaving Adam and the Garden of Eden and consequently transforming into one of the most feared demons in Abrahamic religions and ancient cultures. Lilith is a seductress and a bogeyman, tempting men and preying on children. She is the mother of the demonic entities known as incubi and succubi. Scholars have noted how her name and characterization are similar to the lilu, demons from Babylonian faith that were seducers and child eaters. As of recent, Lilith's origin as well as her long reputation as an evil she beast has made her a feminist icon.

5) Banshees

Gaelic lore tells of long haired women who roam the night, belting out blood curdling screams. Soon after they appear, someone dies. The banshees are legendary as feminine omens of impending doom, particularly death. It's said that they are the spirits of women who died suddenly and violently and spend their afterlives warning the living that one of them will die next. Banshees are held in such high regard that some Irish families have their own banshee to foretell that one of their relatives will die soon. The banshee shares close resemblance to keeners, women who sing mourning songs at funerals in Irish tradition.

6) The Sirens

These creatures from Greek mythology are synonymous with femme fatales and seductresses. The sirens are the temptresses. In the original Greek mythology, the sirens were not mermaids as they are thought to be now. Instead, they were large predatory birds with the heads of beautiful women. But that is the only difference. In all mythology, ancient to modern and regardless of where in the world, the sirens are renowned and feared for their singing, which is so beautiful that anyone who hears will be hypnotized by it and compelled to them, where they will almost certainly meet their doom. In Greek myths like the Odyssey and the journey for the Golden Fleece, the sirens inhabited an island in the middle of the ocean. They would lure passing ships with their enchanting music so that they would crash into the rocks that surrounded the island. The sailors would then either drown or be devoured by the sirens. The only people known to survive are the Argonauts and Odysseus. The Argonauts resisted the sirens' music by blocking out their music with the music played by Orpheus. However, Odysseus is the only one who actually heard the sirens' song but survived. He accomplished this by having his men stuff their ears with wax to act as earplugs then tie him to the ship's mast. He told them that no matter how much he begged and demanded them to release him, they were to keep him tightly bound to the mast until they were far out of earshot of the sirens' music. Sure enough, as they passed the island, Odysseus went raving mad to the music, but none of his men untied him nor were they victimized by the sirens thanks to not hearing them through the wax in their ears.

7) Screaming Jenny

Screaming Jenny is as disturbing as she is grisly and tragic. She haunts the train tracks of West Virginia. What makes her so special is that she appears suddenly, as a ball of fire, to incoming trains. To top it all off, she lets out a blood curdling scream that alerts the train conductors, who stop their trains to check on her. But when they reach her, she's gone. The story of Jenny is all around a sad tale. She was an impoverished woman living in the 1800's. She was so poor that she resorted to squatting in the abandoned shacks by the train tracks, like a lot of the unfortunate souls back then. In spite of her situation, Jenny was a selfless and kind soul. She would share her food with other hungry folk and spare her blanket to those who needed, even when she herself was starving and freezing. One cold night, Jenny was making soup in her shack. As this was the 1800's, she made her soup in a pot over an open fire. She sat close to the fire, so close that an ember leaped out and landed on her skirt, setting it on fire. Jenny screamed in terror and agony as the fire quickly consumed her dress, burning her alive. She ran out of her shack and through the shanty town, screaming and flailing. She didn't realize she was running towards the train tracks nor did she realize the training charging her way. The train rammed into Jenny's burning body, quickly and almost mercifully killing her. Jenny was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave. Since then, Jenny's spirit reenacts her sudden, brutal death at night, always at train tracks.

8) The Bell Witch

If you ever wonder where they got the idea for "The Blair Witch Project", one of the go-to answers is found in the legend of the Bell Witch. The Bell Witch is a famous paranormal phenomenon in Tennessee dating back to the early 19th century and it is every bit as disturbing as the movie it's said to have inspired. In 1817, Adams farmer John Bell and his family became the targets of nightmarish poltergeist activity. It began with John encountering a strange creature with the body of a dog and the head of a hare and members of the family witnessing a black dog following them and a girl in a green dress swinging from a tree. After that, they began to hear strange noises at night, like scratching, dogs howling, thumping, whispers, and chains, which they could never find the source of. But that was nothing compared to what came next. Sheets were yanked away, John began to grow ill, and, worst of all, the children were being terrorized by an invisible force. Betsy was the primary target in these attacks: she would be pulled out of her bed, slapped, pinched, and have her hair yanked. It got so bad that the family brought others to their home to find the cause of this activity. From there, the haunting worsened. The disembodied but very audible voice of a woman would be heard in the house, cursing and singing and taunting. Although Betsy suffered physical abuse from the entity, it was her father, John Bell who was given the worst fate. He became gravely ill and was bedridden before he suddenly died. It was realized he had been poisoned, but nobody was present in his room when the poison was given to him nor could any of them explain how the poison bottle got there or where it came from. As John Bell was laid to rest, his funeral was disrupted by a woman singing merrily. The Bells endured the haunting for a number of years and they would start up again after a seven year interval. It's not entirely certain who or what the Bell Witch was, but many suspect that it was the doing of a woman named Kate Batts. Batts was rumored to be a witch and she had a dispute with John Bell over the dealings of slaves. Batts did die at some point but it's believed she cursed the Bells and came back to haunt them. Today, it's believed that the Bell Witch now resides in a nearby cave, now called the Bell Witch Cave, where a great deal of paranormal activity and strange happenings have been reported.

9) Madam Koi Koi

In the schools of Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa, you will hear the clicking of heels. Not very threatening...until you see a pair of moving red heels with no body attached to it. This is said to be the ghost of Madam Koi Koi, an entity that haunts school halls, dormitories, and bathrooms. The ghost's name comes from the sound her shoes make. In life, she was a teacher known for her red high heels. She was also known for being very harsh, even abusive. She met her demise in either an accident or a violent uprising from her long suffering students. In death, she continues her cruel reign of terror over Africa's school children. Madam Koi Koi is reported to slap people, attack them in the bathrooms, and go after those who arrive to school early or leave late.

10) Medusa

Greek mythology's most (in)famous monstress. As notable as her mane of living snakes is, it's second only to her cursed power which is turning any mortal who looks at her into stone. Like a lot of Greek mythology's antagonists, Medusa was once a human being cursed by the gods. She was once priestess to the goddess Athena and she was so beautiful that mortal and immortal men alike desired her. However, as a priestess to a virgin goddess like Athena, Medusa was sworn to chastity. Unfortunately, this did not stop Poseidon, god of the seas, from pursuing her. Nor did her pleas against him. The god assaulted the young priestess, inside Athena's temple no less. The goddess herself was outraged. It was said that she was not mad at Poseidon, but at Medusa, and she punished her by turning her into a gorgon. Her hair became a nest of living snakes, she grew scales and fangs, and to top it all off she was cursed to turn any one she looked at into stone. Medusa was exiled on an isolated island and many came to slay her, only to be turned to stone by her gaze. She was finally taken down when the young Perseus came along. Using his shield as a rear view mirror, he saw Medusa but remained flesh and blood and, with one swing of his sword, beheaded her. For centuries, she has been widely accepted as the ultimate monstress. As of recent, however, she has finally been acknowledged as a victim rather than a vile beast.

#mythology#legend#folklore#women#greek mythology#la llorona#the bell witch#bell witch#banshee#lilith#kuchisake onna#bloody mary#medusa#sirens#madame koi koi#screaming jenny#long post#cw gore#cw child abuse#cw child death#cw mutilation#cw body horror#cw murder#cw horror#horror

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Researchers have determined that an obsidian mirror believed to have been owned by the sixteenth-century English polymath John Dee originated in the Aztec world. Dee served as a scientific adviser and astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603). Like many Renaissance scholars, he was deeply immersed in occult practices and regularly attempted to communicate with spirits. One of the tools Dee is believed to have used in his magical pursuits is a circular obsidian mirror now in the British Museum. Notes attached to the mirror in the eighteenth century identify it as “The Devil’s Looking-glass” and “The Black Stone into which Dr Dee used to call his Spirits."

The Aztecs used obsidian mirrors of this sort to divine the future, and a number of these objects were brought to Europe following the conquest of Mexico in the early sixteenth century. To determine whether Dee’s mirror was one of these imports, a team led by archaeologist Stuart Campbell of the University of Manchester measured the proportions of various elements in the obsidian. The researchers found that the mirror’s chemical signature closely matches that of obsidian from Pachuca, Mexico, one of the Aztec Empire’s main sources of the volcanic glass. “This helps us understand the mirror as an Aztec object,” says Campbell. “The fact that it already had Aztec associations of divination and being able to see what’s not immediately apparent was seized on by John Dee and added value to the object from his point of view.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wide three-case inro showing plovers in flight above waves, stone basket and water wheel, Koma Kyūhaku, Early 18th century, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Japanese and Korean Art

four sections: rinpa-style with water wheel; white shore protector; plovers flying over waves A number of different motifs are fit onto this compact four case inrō, beginning with a “plover over waves” design in the style of the Rinpa artist, Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716). The plovers are executed in chunky mother-of-pearl inlays and takamaki-e, and fly over mountainous waves that simulates the look of pewter sheeting—an element favored by Kōrin and his predecessor, Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637). Oversized inlays are used for the depiction of the water wheel and rock basket as well, creating an artfully cluttered composition. The imagery of plovers over waves is a common Japanese literary convention, which seems to have first appeared in the Kojiki, an 8th-century compendium of Japanese origin myths. The scene generally connotes the struggle to surmount the difficulties of life. Size: 2 5/16 × 2 1/2 × 7/8 in. (5.87 × 6.35 × 2.22 cm) Medium: Lacquer, kinji, gold, silver takamakie, raden inlays

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/116810/

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Şehzade Bayezid/Bayezid herceg portréja

Origin and upbringing

The exact date of birth of Prince Bayezid is unknown, probably he was born in 1526 or 1527 in Istanbul as the fifth child of Sultan Suleiman and his favorite concubine, Hürrem. Suleiman and Hürrem probably did not plan more children after Bayezid, their family planning at least strongly suggests this. By the time he was born, he already had four older brothers and a half-brother, all of whom could form a right to the throne. But since the throne was not fundamentally the right of the first-born prince, Bayezid did not start at a disadvantage because of the order of birth. However, the older princes had more time and opportunity to gain supporters for themselves, to prove their aptitude. Bayezid waited his whole life to prove his ability, but fate brought it in a different way.

In 1530, Sultan Suleiman ordered the circumcision of his three eldest sons, Mustafa, Mehmed, and Selim. Bayezid was only three years younger than Selim, while Selim was nine years younger than Mustafa. Why Bayezid was omitted is clear, as the prince, up to 3.5-4 years old, was too young for the ceremony, especially considering that the eldest prince, Mustafa, was already 15 years old at the time. However, it raises several questions as to why - given that Hürrem and Suleiman probably did not plan more children- was Selim not left out of the circumcision also so that he could be circumcised later together with Bayezid? Why was Bayezide left alone? My theory for this is that the son born between Selim and Bayezid, Abdullah, was still alive at the time of the organization of the circumcision. Thus, it is possible that Suleiman planned to circumcise Abdullah and Bayezid later in another ceremony, but Abdullah died in the meantime, leaving Bayezid alone.

Bayezid, nevertheless received the same thorough education as his older brothers, but was fundamentally separate from them. In addition, the circumcised princes had already been introduced to the people, to the statesmen, to the soldiers during the ceremony so they were much better known. Meanwhile Bayezid wasn't really known, since he wasn't introduced yet. Then in 1532 Hürrem gave birth to another child, which could fill Bayezid with the hope that he would also have a younger brother with whom he could study and go on a campaign and Selim did with Mehmed. However, the child was born with physical deformities, so Bayezid could not dream of a similar pairing as his older siblings had. We do not know whether Bayezid himself experienced these events so negatively or only posterity explains the situation so negatively. Either way, the fact that Bayezid was paired with Cihangir instead of his older brothers seems to have marked his life forever. The relationship between Bayezid and Cihangir never seems to have been a close one. Cihangir always accompanied his mother when she visited Selim in his province, but there is no indication that he went to Bayezid's province with his mother as well. This, of course, could have been only a coincidence, but it also raises the possibility that Bayezid maybe was mean with Cihangir during their childhood or maybe he made Cihangir to know how unhappy he was with the pairing?

In 1537 Suleiman went on a campaign and took Hürrem's two circumcised sons, Mehmed, 16, and Selim, 13, with himself too. However, Bayezid was only 10-11 years old at the time, so he was not fit to accompany his father at that age, nor was he circumcised. Probably Bayezid had a hard time having to stay home with his mother and younger brother while his older brothers gather the first war-experiences of their lives.

In 1539 Bayezid's sister Mihrimah married Rüstem Pasha and Suleiman decided to combine the wedding ceremonie and the circumcision ceremony of Bayezid and Cihangir. The ceremony lasted more than two weeks but was far less spectacular than the ceremony 9 years earlier, but there were financial reasons for it.

The young prince

In 1543 Suleiman went on another campaign against the Kingdom of Hungary and took Prince Bayezid with him this time. On their way to home from the campaign, they received the news that Bayezid’s eldest brother, Prince Mehmed, had passed away. Sultan Suleiman was completely shattered, which also affected his health. A long mourning greeted the family. After such years, Bayezid's life changed in 1546, as Suleiman assigned him to his first princely province to Konya. His mother did not accomponied him to his new province, as she had not previously accompanied either Mehmed or Selim. Thus Bayezid was accompanied by his governess and a harem chosen by his mother with great care.

Bayezid did not choose a favorite concubine for himself like his brother Selim or his father did. He had a lot of concubines, all his children were born from different women. Bayezid had an extremely large number of sons, which is unusual since most princes did some kind of family planning. Bayezid, on the other hand, had at least seven sons and at least four daughters. His children:

Orhan, according to some sources, was born in 1543, but this is not possible, given that Bayezid received a province only in 1546. Before that he could not have had a child, thus Orhan was probably born in 1546. He was sent to his own province in December 1558 to Çorumba by his grandfather. The young prince was then said to be "strikingly handsome." According to some sources, as soon as he got his province, he made pregnant one of his concubines, who later gave birth to a son. However, there is no evidence to that.

Osman, who was Mahmdus’s full-brother, was born in an uncertain year, but since he didn’t get his own province with Orhan, he was presumably a little younger than him. He may have died as a child, as most sources do not mention him among his brothers in the records of the 1562's execution.

Mihrimah, was born in 1547. Suleiman arranged the wedding a wedding for her and for the three daughters of Prince Selim and the younger daughter of Prince Mustafa in 1562. Mihrimah's husband was Muzaffer Pasa. No information has survived about their marriage, most probably they didn't have any children. Mihrimah was forced to follow her husband to his posts. Her her husband was first a governor of Baghdad, Şehr-i Zor and then Cyprus. Her husband died in 1593, and it is probable that Mihrimah was no longer alive at that time because no one mentioned her later. There is also a chance that she died long before her husband.

Abdullah, he may have been born after 1548.

Hatice, born around 1550 and most likely deceased as a child.

Mahmud, was born in 1552 as Osman's full-brother.

Ayşe, born around 1553. She married much later than her sister. Her husband was Eretnaoglu Hoca Ali Pasa, with whom she had a son, Sultanzade Mehmed Bey. It is not known when the boy was born. Even the date of her marriage is uncertain, but most probably she was not married off by her grandfather but by his uncle, Selim. We know nothing about the life of Ayşe and the time of her death is unknown as well.

Mehmed was born around 1554.

Murad was born around 1556. He may have died as a child, as most sources do not mention him among his brothers in the records of the execution.

Hanzade was born around 1556 and probably died as a child.

Bayezid’s last child was a boy whose name is unknown and who was born in 1559 or 1560.

We do not have much information about the reign of Bayezid in Konya. However, he lived there when Suleiman asked him to go with him to his campaign in Aleppo to gain experience. Bayezid had been waiting for this opportunity for years, so he must have gladly joined his father. They spent together the winter of 1548 near Aleppo and Prince Cihangir was with them also. In the spring, Suleiman ordered a huge hunt, during which he also had the opportunity to spend time with Bayezid. Bayezid, who wanted the attention and recognition of his father, certainly enjoyed the hunt. Bayezid remained in Aleppo with his father until June 1549, when the army set out on the frontier to continue fighting, and Bayezid returned to Konya.

Fight for the throne

Bayezid is commonly regarded as one of the best examples of the struggle for the throne. At the time of his birth, he had little chance of ascending the throne since he had four older brothers. However, Prince Abdullah soon passed away, and in 1543 he was succeeded by Mehmed and finally in 1553 Suleiman himself executed Prince Mustafa, Bayezid's eldest half-brother, so his chances gradually increased. There are legends - and the series has confirmed this - that Bayezid and Mustafa were close to each other. However, this is not true. Bayezid was still a child when Mustafa left Istanbul, and later they barely met (if they met at all). One of the strongest counter-arguments to their good relationship is that in 1553 Sultan Suleiman left Bayezid as the defender of Istanbul when he went on a campaign. Suleiman already knew by then that Prince Mustafa would be executed during the campaign, which is why he feared that Mustafa, guessing the events, would march to Istanbul and occupy the throne. Suleiman then had three sons beside Mustafa: the sick Cihangir, the calm Selim, and the warrior Bayezid. It was a logical decision to leave Bayezid in the position of protector of the capital, as with his aggressive and sudden nature, he would have been more likely to arrest Mustafa while trying to invade the capital, than Cihangir, Selim, or any of the pashas. If Suleiman would have been insecure about Bayezid’s allegiance he would never have left him near the capital in such perilous times.

The former events also shed light on the fact that Bayezid was not at a disadvantage against Selim in the battle for the throne in the early 1550s. And most likely this was thanks to the existence of Hürrem Sultan, his mother. For Hürrem had always tried to restrain Bayezid so that he would not anger his father with his sudden nature and thoughtless words. Bayezid was the most temperamental and agressive in the family. Many said he resemled Suleiman's father, Sultan Yavuz Selim, with the difference that he lacked Yavuz Selim's prudence and intelligence. Suleiman was famous for his fear of his own father, so he was probably not really happy that Bayezid constantly reminded him of Yavuz Selim. In any case, Hürrem did her best to support Bayezid, as did Mihrimah and Rüstem Pasha. However, there are opinions that Hürrem's support was directed at Bayezid only because she feared that if she did not support him, Bayezid would reach his own death while angering the Sultan. Those who are of this opinion believe that Hürrem wanted to see Prince Selim on the throne, not Bayezid. Why? For Selim was a good-natured, humble person who would never have been able to execute his brothers, so with Selim's reign the law of fratricide could have ended maybe and Bayezid would have survived. Knowing Hürrem’s ingenuity, her commitment to her sons, and Selim’s humbleness and the nature of Bayezid, my personal opinion is the same.

Loosing his father

Many believe that Hürrem’s death in 1558 was the event that separated Bayezid and Suleiman, but this is not true. The two of them never stood really close to each other because of their extremely different personalities. And the execution of Mustafa in 1553 further aggravated the situation. After the execution of Mustafa, huge rebellions broke out throughout the empire, for example, in Rumelia, an imposter claimed to be Prince Mustafa himself, and gathered huge support. Bayezid, as the guardian of the capital, should have reacted immediately to the events, but he probably did not assess the situation correctly because he did not take proper action against the pseudo-Mustafa even after a long delay. Indeed! According to the Austrian ambassador, Bayezid himself supported the pseudo-Mustafa because he was frightened that he could at any time had the same fate as Mustafa. After Bayezid's late act, suspicion awoke in Suleiman, the Sultan was furious, and Hürrem could hardly managed to convince the Sultan that Bayezid was innocent, he just reacted badly to the situation. Eventually, Hürrem's supplication and Bayezid's apology softened the sultan's heart, but he moved him from the province of Konya to Kütahya in 1555. Suleiman finally let his son go after a long educational speech.

After these events, the situation between Suleiman and his son could never be consolidated. Especially given that Bayezid experienced moving to Kütahya as an exile, even though Kütahya was no further from the capital than Selim’s post. He probably voiced this in his letters, at least one of Suleiman's surviving letters suggests this, “[Y]ou may leave all to God, for it is not man’s pleasure, but God’s will, that disposes of kingdoms and their government. If He has decreed that you shall have the kingdom after me, no man living will be able to prevent it.” This makes it clear that Suleiman did not want to deal with succession, even if he himself preferred Selim, he never stated that he would consider Selim as his heir. Even though we know that Selim grew very attached to his father during the campaign of 1553-1555, he supported his father after the loss of Cihangir and perhaps it was there that Suleiman’s heart began to draw more towards Selim. Maybe Bayezid might have felt something from this and maybe that’s why he didn’t really believe that his father wouldn’t interfere in the succession?

In 1558 Hürrem Sultan passed away, with this Bayezid losing his most influential supporter, who had already saved him several times. Of Hürrem's children, Bayezid's life was perhaps most affected by Hürrem's death. Bayezid, however, still had several supporters, including Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha and Mihrimah Sultan, who sought to keep Hürrem’s will by trying to protect the prince. Unfortunately, however, none of them had a big enough impact on the prince as his mother was, so the prince didn’t even listen to them. It is possible that after Hürrem's death there may have been some dispute between Selim and Bayezid, for in the summer of 1558 the Sultan decided to transfer both his sons to new provinces. He sent Selim to Konya and Bayezid to Amasya. The appointment to Amasya may have concealed a hint that Bayezid will also suffer the fate of Prince Mustafa if he does not behave properly, but it may also be that Suleiman had no such intention. For even then the sultan did not name any of his sons as his successors, and both of his sons were at roughly similar distances from Istanbul. Selim, as always, obeyed immediately, but Bayezid first refused the order and only left for Amasya after a long hesitation. From this period we are left with the correspondence of Suleiman and Bayezid, in which Bayezid writes, “Forgive Bayezid’s offense, spare the life of this slave /I am innocent, God knows, my fortune-favored sultan, my father”; in response, Süleyman wrote, “My Bayezid, I’ll forgive your offense if you mend your ways / But for once do not say ‘I am innocent,’ show repentance, my dear son.” This also shows well that Suleiman, although angry with his son, did not intend to take action against him despite his series of mistakes.

The rebellion

Bayezid feared that his father would execute him like he did with Mustafa. However, Suleiman did not have such an intention either, at that time he had not dealt with succession for years. It was Bayezid's own paranoia which chased him to the wrong path. At that time, the provinces were not stable at all, especially not the Eastern ones like Amasya. Maybe this is why Bayezid came up with the idea and started recruiting an army. It was not clear what the purpose of his was. Some say he only wanted to kill Selim with his son Murad and then retreat to Amasya and wait there for Suleiman's death. Others say he would have got rid of the sultan after Selim and Murad. In my opinion, he hoped that if he succeeded in killing Selim and Murad, the Sultan would accept him as his heir. Bayezid had to see that his small and not that devoted army was not fit to confront with the sultan as well, perhaps enough against a princely army, but not against the sultan. If Bayezid hoped his father would accept him becoming the sultan, he was wrong. Suleyman would do anything to avoid it. During this period, Suleiman made preparations to make succession possible throughout the female line also. Thus, if Selim and Murad had passed away, he would have named his nephew Kara Osmanşah as his heir and he would hunt down Bayezid, as a traitorous and rebellious prince does not deserve the throne. It was only then, that Suleiman clearly decided and chosed a heir, Selim (in case of his death, Murad and in case of his death Kara Osmanşah).

For his rebellion Bayezid also received money from his sister, Mihrimah, to equip the army. When Suleiman realized this, he immediately questioned his daughter, who „confessed that she had done this to execute the will of the mother, who had arranged this in her testament.” Suleiman repeatedly ordered his son to disarm, but Bayezid did not do it. With this, Bayezid was named by the sultan as a rebel. From then on, there was no other way but open rebellion.

So Bayezid set out with his army toward Konya to meet with his brother. Prince Selim asked for his father's help, which, of course, he received with the order not to attack, but wait for what Bayezid would do. Suleiman perhaps hoped that if Bayezid saw Selim's army united with the imperial army he would gave up. But Bayezid did not gave up, but attacked. At the end of May 1559, the two armies fought on the Konyan plain. The battle lasted for two days, at the end of which Selim triumphed, but Bayezid was able to escape the battle-scene, back to Amasya. From there, he wrote a letter asking his father for forgiveness. The sultan responded positively, writing to his son, he would grant it only if Bayezid would execute those who had „led him astray”. Bayezid largely disregarded the order, beheading only three of his suite. This shows that beside his temper he was a fair man, who couldn’t punish „innocent” people just for his sake.

This event only further angered Suleiman, so Bayezid made a final decision and left Amasya with his sons and his remaining army heading east. Only four of his sons were with him, Orhan, Abdullah, Mahmoud, and Mehmed. Murad and Osman presumably passed away earlier. He had another son, who may not have been born at all at that time, perhaps only after his father left. The pregnant concubine may have been one of the few women who had certainly prayed for the birth of a daughter, for by then it was clear what would be the fate of Bayezid and his sons. However, fate was not merciful to the concubine and her son was born.

The refugee

Bayezid and his army were heading east, not stopping to battle with the governor of either province. They got into a minor fight only at the Iranian border when they tried to keep them within the empire. Eventually, however, they successfully crossed the Iranian border in August and sought refuge from the Persian Shah. Suleiman himself had followed his son, and before him Sokollu Mehmed Pasa and Prince Selim were chasing Bayezid.

Bayezid was received as a guest in October 1560 by Tahmasp Shah as part of a magnificent ceremony in the capital, Quazvin. When it became clear that Bayezid and Tahmasp were allied with each other, Suleiman lined up his army along the Iranian border and initiated negotiations with Tahmasp. Finally, in December, he allowed Selim to return home and also reduced the army to less readiness, recalling some of them. Suleiman would not have done this for no reason, Tahmasp probably assured him that he did not intend to fight. This shows well that Tahmasp probably cheated on Bayezid, for if the Shah really wanted to attack, he would not have begun to negotiate with Suleiman. Tahmasp Shah probably wanted to get the best out of the situation for his country, which was not a war but a peaceful solution. It was for this reason that Bayezid's situation changed rapidly and he soon became a prisoner from a guest. Bayezid and his sons were imprisoned, and his followers were sent away by the Shah so that he could negotiate with Suleiman in peace.

Negotiations have dragged on for a long time. By July 1561, Suleiman had already offered 900,000 ducats, supplemented by Prince Selim's 300,000 ducats, as well as the castle of Kars, if the Shah returned Bayezid and his sons. Tahmasp thought at length, but refused despite the very generous offer. He knew that he could ask for almost anything and it would be given to him sooner or later, since Bayezid was a threat to the Ottoman Empire as long as he lived, but he did not dare to overstretch the string either. Foresight, Tahmasp did not seek out Suleiman, but Prince Selim, the future sultan, with his own offer. Tahmasp knew that it was better to make an alliance with the future sultan, so in March 1562 he sent envoys to Kütahya, Selim. Tahmasp also wanted a trade and peace agreement with Selim in addition to the 1,200,000 ducats and the castle of Kars. We do not know whether Selim himself decided to agree with Tahmasp or Suleiman was also asked. Knowing Selim, who never did anything without his father’s permission, he most probably asked the Sultan about it, or Suleiman had previously given him a free decision on the topic. Either way, the offer of the Shah was finally accepted.

His death

Tahmasp Shah finally let the Ottoman delegation to enter to the prison of Bayezid and his sons on July 23, 1562. Legend has it that Tahmasp specifically only let Prince Selim's men to enter to the prison, having previously promised Bayezid that he would never hand him over to Suleiman. In doing so, he was essentially able to keep his word. Thus it was Ali Aga, the head of Selim's delegation, who immediately ordered the execution of the princes having a legal fetwa from the Seyhülislam and Suleiman himself. At the same time, Bayezid's youngest son was executed in Bursa also. They were all denied a fair burial in Bursa and were buried outside the walls of Sivas. Probably the reason for this was - beyond Suleiman’s greate anger - that it would have been risky to travel five coffins through Anatolia, which already was a dangerous place that time.

Bayezid's guilt is not in question, so is the legitimacy of his execution. If Bayezid would patiently waited he would probably survive. Although he would never have been a sultan, since no one but a few Janissary troops supported him, Selim himself probably would not have executed his brothers, but would have kept them isolated. Although it is worth noting that Bayezid would not have accepted this by his nature either, so perhaps Selim would eventually have been forced to execute him.

The case of Bayezid and his family is a good example of where a rebellious prince end up in the end. Bayezid’s rebellion and then execution undoubtedly further aggravated Selim’s depression and exacerbated Mihrimah’s grief, and Suleiman’s pain was also unimaginable. Many blame Suleiman, but it became abundantly clear from the events that Suleiman, especially compare with the case of Mustafa, was extremely forgiving toward Bayezid. In addition to his parents and siblings, the fate of his children was forever marked by Bayezid's rebellion. It is not enough that his sons were executed along him, his concubines were also married without special care, to people who were much less worthy than usual, and Bayezis's daughters were denied marriages worthy of their rank. In addition, no one remembered his daughters for years to come, they lived and died completely in oblivion. All this was thank to Bayezid's rebellion.

Private opinion about Bayezid: I have been suffering with this portrait for a very long time. It was much more difficult to write it than it was to write Mustafa's. Mustafa's life was simply so depressing that I had a hard time getting myself into writing. In the case of Bayezid, however, I simply became more and more angry. I feel it’s especially important to bring these people as close to us as possible with the portraits. I try to personalize the writing separately so that we can feel what was going on in the minds of these historical characters. So far, I feel like I’ve managed to fully feel every historical figure, imagine myself in their place and see why they did what. In the case of Bayezid, this did not happened at all. The more I read about him the more angry I became and wanted to shout at him, "why are you doing this ?!". I can’t help it, but I simply feel sorry for everyone around Bayezid more than I feel sorry him, because I think his death was solely and exclusively caused by the series of his bad decisions.

Used sources: L. Peirce - The imperial harem; L. Peirce - Empress of the East; C. Imber - The Ottoman Empire 1300-1650; Y. Öztuna - Kanuni Sultan Süleyman

* * *

Eredete és neveltetése

Bayezid herceg pontos születési ideje nem ismert, valószínűleg 1526-ban vagy 1527-ben jött világra Isztambulban Szulejmán szultán és kedvenc ágyasa, Hürrem ötödik gyermekeként. Szulejmán és Hürrem valószínűleg Bayezid után nem tervezett több gyermeket, családtervezésük legalábbis erősen erre utal. Születésekor már négy édesbátyja és egy féltestvére volt, akik mind jogot formálhattak a trónra. Mivel a trón alapvetően nem az első szülött herceg joga, Bayezid sem születési sorrendje miatt indult hátrányból. Azonban az idősebb hercegeknek több idejük és lehetőségük volt maguknak támogatókat szerezni, bizonyítani rátermettségüket. Bayezid egész életében arra várt, hogy bizonyíthassa alkalmasságát, ám a sors így hozta.

1530-ban Szulejmán szultán elrendelte három idősebb fiának, Musztafának, Mehmednek és Szelimnek a körülmetélését. Bayezid csupán három évvel volt fiatalabb Szelimnél, míg Szelim kilenc évvel volt ifjabb Musztafánál. Az, hogy Bayezidet miért hagyták ki egyértelmű, hiszen a maximum 3,5-4 éves herceg túl fiatal volt a szertartáshoz, különösen figyelembe véve azt, hogy a legidősebb herceg, Musztafa ekkor már 15 éves volt. Az azonban több kérdést felvet, hogy - tekintettel arra, hogy valószínűleg nem tervezett Hürrem és Szulejmán több gyermeket - Szelimet miért nem hagyták ki a körülmetélésből, hogy később Bayeziddel együtt metélhessék körül? Miért hagyták Bayezidet egyedül? Erre egy lehetséges magyarázat, hogy a Szelim és Bayezid között született fiú, Abdullah még életben volt a körülmetélés szervezése során. Így tehát lehetséges, hogy Szulejmán úgy tervezte, Abdullah és Bayezid hercegeket később fogja körülmetéltetni egy másik ceremónia során, Abdullah azonban időközben elhunyt, így Bayezid egyedül maradt.

A körülmetélési szertartásból kimaradt Bayezid ettől függetlenül ugyanolyan alapos nevelésben és oktatásban részesült, mint idősebb testvérei, azonban tőlük alapvetően elkülönülve. Emellett pedig a körülmetélt hercegeket már bemutatták a birodalomnak, az államférfiaknak, így ők sokkal ismertebbek voltak, mondhatni már beavatott örökösök. 1532-ben aztán Hürrem újabb gyermeknek adott életet, ez pedig reménnyel tölthette el Bayezidet, hogy neki is lesz egy kisebb testvére, akivel együtt tanulhat, mehet majd hadjáratra. A gyermek azonban fizikai deformitásokkal jött világra, így Bayezid nem álmodhatott olyan párosításról, ami idősebb testvéreinek jutott. Nem tudjuk, hogy Bayezid maga is ilyen negatívan élte e meg ezeket az eseményeket vagy csak az utókor magyarázza bele a helyzetbe. Akárhogyan is, az hogy Bayezidet Cihangirral párosították, idősebb bátyjai helyett úgy tűnik örökre megpecsételte életét. Bayezid és Cihangir között úgy tűnik sosem volt szoros a viszony. Cihangir mindig elkísérte édesanyját, mikor az Szelimet látogatta meg tartományában, azonban nincs arra utaló jel, hogy Bayezidhez is anyjával tartott volna. Ez természetesen lehet véletlen is, de felveti annak a lehetőségét is, hogy Bayezid gyermekkorukban talán éreztette Cihangirral, mennyire nem örül a párosításnak?

1537-ben Szulejmán hadjáratra indult, melyre magával vitte Hürrem két körülmetélt fiát, a 16 éves Mehmedet és a 13 éves Szelimet. Bayezid azonban még csak 10-11 éves volt ekkor, tehát korban sem volt alkalmas arra, hogy elkísérje apját, valamint körül sem volt metélve. Valószínűleg Bayezid nehezen viselte, hogy otthon kell maradnia anyjával és öccsével, míg bátyjai életük első harcászati tapasztalatait gyűjtik be.

1539-ben Bayezid nővére, Mihrimah férjhez ment Rüsztem Pasához. Az esküvői ünnepségekkel összevonva pedig Szulejmán úgy döntött megtartják Bayezid és Cihangir hercegek körülmetélési szertartását is. Az ünnepség több, mint két hétig tartott ám jóval kevésbé volt látványos, mint a 9 évvel korábbi ceremónia, ám ennek gazdasági okai voltak, nem a hercegek ellen irányult.

Az ifjú herceg

1543-ban Szulejmán újabb hadjáratra indult a Magyar Királyság ellen és ezen hadjáratra magával vitte Bayezid herceget is. A hadjáratról hazafelé tartva kapták a hírt, hogy Bayezid legidősebb bátyja, Mehmed herceg elhunyt. Szulejmán szultán teljesen összetört, ami egészségére is kihatással volt. Hosszas gyász köszöntött a családra, mígnem 1546-ban Bayezid élete felpezsdült, ugyanis Szulejmán kivenezte őt Konya tartomány élére. Édesanyja nem tartott vele új tartományába, ahogy korábban sem kísérte el sem Mehmedet sem Szelimet. Így Bayezidet is dajkája és az anyja által nagy gonddal kiválasztott háreme kísérte el Konyába.

Bayezid nem választott magának kedvenc ágyast, mint bátyja Szelim vagy édesapja. Nagyon sok ágyasa volt, minden gyermeke más nőtől született. Bayezidnek extrém sok fia volt, ami szokatlan, hiszen a legtöbb herceg valamiféle családtervezést folytatott. Bayezidnek viszont legalább hét fia született és legalább négy lánya. Gyermekei:

Orhan egyes források szerint 1543-ban született, ám ez nem lehetséges, tekintettel arra, hogy Bayezid 1546-ban kapott tartományt, előtte nem lehetett gyermeke. Így Orhan valószínűleg 1546-ban született. Saját tartományba 1558 decemberében küldte őt nagyapja, Çorumba. A fiatal hercegről ekkor azt mondták, hogy "különösen jóképű". Egyes források szerint, amint tartományába került teherbeejtette egyik ágyasát, aki később fiút szült neki. Erre azonban nem utal semmi féle bizonyíték.

Osman, aki édestestvére volt Mahmdunak, születési ideje bizonyalan, ám mivel ő nem kapott saját tartományt Orhannal együtt, feltehetőleg fiatalabb volt nála valamennyivel. Lehetséges, hogy már gyermekként elhunyt, ugyanis a legtöbb forrás nem említi testvérei között a kivégzésről szóló feljegyzésekben.

Mihrimah, 1547-ben jött világra. Szulejmán 1562 nyarán esküvő szervezésbe fogott és Szelim herceg három lánya, valamint Musztafa herceg kisebbik lánya mellett Mihrimaht is kiházasította. Mihrimah férje Muzaffer Pasa lett. Házasságukról nem maradt fenn semmilyen információ, gyermekeik valószínűleg nem születtek. Mihrimah a házasság révén kénytelen volt elhagyni Isztambult, férje ugyanis előbb Bagdad, Şehr-i Zor majd Ciprus helytartója volt, Mihrimahnak pedig követnie kellett férjét éppen aktuális pozíciójára. Férje 1593-ban hunyt el, és valószínű, hogy Mihrimah ekkor már nem volt életben, mert senki sem említette a későbbiekben. Arra is meg van az esély, hogy jóval férje előtt elhunyt már.

Abdullah, 1548 után születhetett.

Hatice, 1550 körül született és nagy valószínűséggel gyermekkorában elhunyt.

Mahmud, 1552-ben jött világra, Osman édesöccseként.

Ayşe, 1553 körül született. Ő jóval később ment férjhez, mint nővére. Esetében a kiválasztott férj, Eretnaoglu Hoca Ali Pasa volt, akivel született egy fiuk, Sultanzade Mehmed Bég. Nem tudni, hogy fiuk mikor született, azt sem, mikor házasodtak össze. Valószínűleg őt már nem nagyapja, hanem nagybátyja, Szelim házasította ki. Ayşe életéről semmit nem tudunk és halálának ideje is ismeretlen.

Mehmed, 1554 körül született.

Murad, 1556 körül jött világra. Lehetséges, hogy már gyermekként elhunyt, ugyanis a legtöbb forrás nem említi testvérei között a kivégzésről szóló feljegyzésekben.

Hanzade 1556 körül született és valószínűleg gyermekként elhunyt.

Bayezid utolsó gyermeke egy fiú volt, akinek neve nem ismert, és aki 1559-ben vagy 1560-ban jött világra.

Bayezid Konyai uralkodásáról nem sok információnk van. Itt élt azonban, mikor Szulejmán aleppói hadjáratára magához rendelte fiát, hogy tapasztalatokat szerezhessen. Bayezid évek óta várhatott már erre a lehetőségre, így bizonyára nagy örömmel csatlakozott apjához. Az 1548-49-es telet együtt töltötték Aleppo környékén és velük volt Cihangir herceg is. Tavasszal pedig Szulejmán hatalmas vadászatot rendelt el, melynek során alkalma volt Bayeziddel is időt tölteni. Az apja figyelmére és elismerésére vágyó Bayezid minden bizonnyal nagyon élvezte a vadászatot. Bayezid 1549 júniusáig maradt Aleppoban apjával, ekkor ugyanis a hadsereg megindult a frontra, hogy folytassák a harcokat, Bayezid pedig visszatért Konyába.

Harc a trónért

Bayezidet szokás a trónért folyó harc egyik mintapéldájának tekinteni. Születésekor nem sok esélye volt a trónra négy idősebb bátyja mellett. Azonban Abdullah herceg hamarosan elhunyt, 1543-ban őt követte Mehmed majd végül 1553-ban maga Szulejmán végeztette ki Musztafa herceget, Bayezid legidősebb, féltestvérét, így esélyei fokozatosan növekedtek. Vannak olyan legendák - és erre a sorozat is ráerősített - melyek szerint Bayezid és Musztafa közel álltak egymáshoz. Azonban ez a legkevésbé sem igaz. Bayezid gyermek volt még, mikor Musztafa elhagyta Isztambult, később pedig alig találkoztak (ha találkoztak egyáltalán). Jó viszonyuk egyik legerősebb ellenérve az, hogy 1553-ban Szulejmán szultán Bayezidet hagyta hátra, mint Isztambul védelmezőjét, mikor hadjáratra vonult. Szulejmán ekkor már tudta, hogy Musztafa herceget a hadjárat során ki fogja végeztetni, épp ezért félt attól, hogy Musztafa megsejtve az eseményeket Isztambulba vonul és elfoglalja a trónt. Szulejmánnak ekkor három fia volt Musztafán kívül: a beteges Cihangir, a nyugodt Szelim és a harcos Bayezid. Logikus döntés volt, hogy Bayezidet hagyta a főváros védelmezőjének pozíciójában, hiszen agresszív és hirtelen természetével, nagyobb eséllyel tudta volna feltartóztatni az oda betörő Musztafát, mint Cihangir, Szelim vagy bármelyik pasa. Ha Szulejmán bizonytalan lett volna Bayezid hűségében sosem hagyta volna a főváros közelében ilyen vészterhes időkben.

Az előbbi események arra is rávilágítanak, hogy Bayezid az 1550-es évek elején nem volt hátrányban Szelimmel szemben a trónért folyó harcban. Ám ennek nagy valószínűséggel Hürrem szultána létezése volt oka. Hürrem ugyanis mindig is igyekezett Bayezidet féken tartani, hogy az ne dühítse apját hirtelen természetével és meggondolatlan szavaival. Bayezid volt ugyanis a családban a legtemperamentumosabb és legerőszakosabb. Sokak szerint Szulejmán apjára, Yavuz Szelim szultánra emlékeztetett mindenkit, annyi különbséggel, hogy hiányzott belőle Yavuz Szelim megfontoltsága és eszessége. Szulejmán pedíg híresen tartott apjától, így feltehetőleg nem igazán örült annak, hogy Bayezid állandóan őrá emlékezteti. Mindenesetre Hürrem szultána minden erejével Bayaezidet támogatta, akárcsak Mihrimah és Rüsztem pasa. Azonban olyan vélemények is vannak, melyek szerint támogatása csupán azért Bayezid felé irányult, mert félt, hogy ha nem őt támogatja Bayezid eléri a szultánnál a saját halálát. Akik ezen a véleményen vannak úgy gondolják, hogy Hürrem is Szelim herceget szerette volna a trónon látni, nem Bayezidet. Miért? Mert Szelim jólelkű, szerény személy volt, aki sosem lett volna képes kivégeztetni testvéreit, így Szelim uralkodásával a testvérgyilkosság törvénye véget érhetett volna és Bayezid is életben maradt volna. Ismerve Hürrem eszességét, fiai iránti elkötelezettségét, valamint Szelim rátermedtségét és Bayezid természetét személyes véleményem ugyanez.

Eltávolodása apjától