#this legacy is not anything imposed by a human man but by the systems and roles that haunt palmer and become more Real than flesh and blood

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

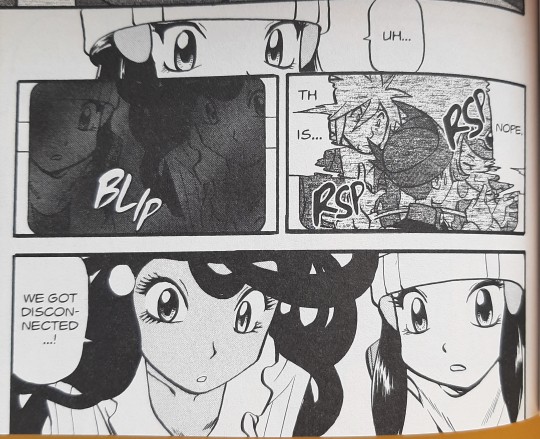

palmer appearing for a split second in the static and then vanishing. never mind this isn't weird distortion stuff the battle frontier's just haunted

#pokespe liveblog#not to get on my hauntology of static bullshit again#but palmer as the specter of a faltering legacy that looms heavy in the minds of all those affected by it#the culmination of the aloof powerful figure alongside the backwards traced familial questions that have lingered through the arcs#'where are the adults' is a common question asked during pokespe sinnoh#the answer is that the adults are no longer adults but abstracted representations of a power structure#pearl is burdened by his father's legacy#this legacy is not anything imposed by a human man but by the systems and roles that haunt palmer and become more Real than flesh and blood#platinum seeks information on the distortion world and instead faces flickers of the root of the known powerbase#her last sight before total obfuscation is the man who stood as an unseen hand in her journey#i don't necessarily think this makes palmer sinister since he seemed cool-ish in the few panels we saw of him#but he does occupy a certain kind of position in the narrative that's interesting to explore

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway. as a followup to this,

RECEIPTS FOR CHARLES’ PSYCHIC FUCKERY

i think xavier fucks with people’s minds like no other psychics -- at least in part -- is because he’s always very deliberate with the way he uses his powers since very early on.

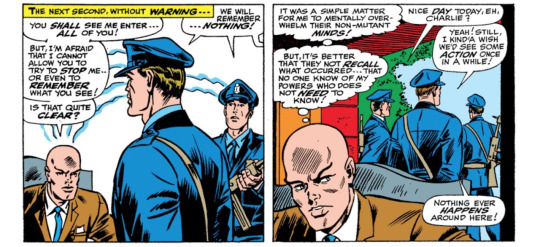

[uncanny x-men #38] is the canon moment where humans officially “discovered” mutants among them and anti-mutant became an organized public sentiment. charles upon reading the news immediately flew all the way to DC to meet the FBI agent conducting investigation on the supposed “mutant menace.”

when getting pass the armed guards, he considered that while he could simply use mind control to order them to let him pass, it’s better if they didn’t remember the encounter altogether.

this seems a pretty small and very unremarkably reasonable thought, all things considered, but it underpins the way this man thinks and how he interacts with his ability vis-a-vis the world, namely...

he has the uncanny ability and aptitude to blend the mental/constructed world with the “real” world and make you doubt yourself

in the same issue [#38], when confronting the FBI agents, instead of making it so that the agent simply freeze or unable to push him, he made it so that the agent (in green) THOUGHT he’s pushing, but was actually not.

it’s a subtle difference, but the effect psychologically is just that much more jarring -- you’re not just being “controlled.” it’s not just an outside force imposing upon you and your body, your entirely perception of reality and of YOURSELF is challenged. after this, how can you trust ANYTHING that you do when this man is around?

[THIS POST IS TOO FUCKING LONG IM PUTTING IT UNDER CUT]

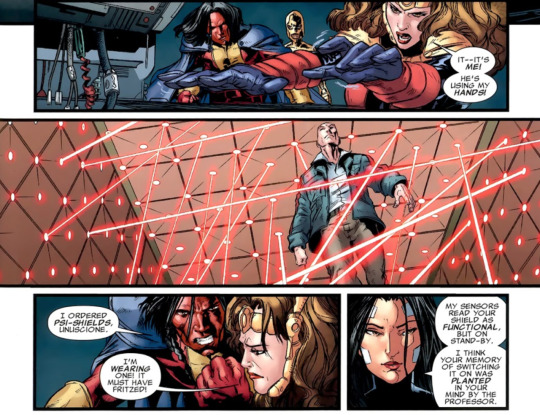

a similar trick was done in [legacy #225] when xavier single-handedly infiltrated the acolytes’ base.

at first they were surprised that he was able to bypass the security system, seemingly having the computers and weapons under his command (how could that be? “he has no telekinetic powers!” poor bennet exclaimed). but as it turns out, he’s actually controlling unuscione to do his bidding from the control room.

when questioned why her psi-shield wasn’t working, sentinel pointed out that it would’ve been... if it was turned on at all -- charles implanted the false memory of turning on the psi-shield in unuscione’s mind.

how fucking clever, chilling and mind-bending a trick is that?! for its subtlety. and it once again made it so that you can’t trust yourself.

i can go on about this whole sequence, including his encounter with random where he revealed that he’s bypassed his psi-shield by planting the hypnotic suggestions in his mind the night before in hiS DREAM-- this shows another aspect of his style of psychic warfare...

he plays the long game.

how long? it may be a minute, an hour, a day or a fortnight... but either way, he’d started before you knew it’s begun. he’s ahead of you. even just by a half step.

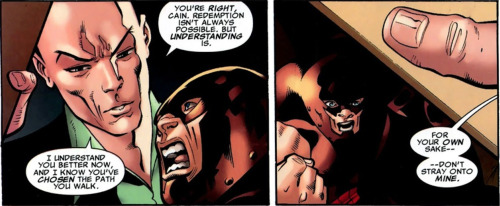

and then sometimes you get something like [legacy #219], where cain didn’t even know WHEN charles got into his head. in fact, he lived out a whole fucking scenario in which he killed charles for god knows how many days, weeks, or months, before the illusion was shattered.

(the way this thing went down was also just... a whole thing. i highly recommend checking it out. it’s a single issue one-shot but one of my favorite issues that’s both a master character study of charles fucking xavier, and a dissection of this troubled brotherly dynamic.)

herein lies the paradox or perhaps one of the contradictions with this character... however bizarre and out-of-touch his relationships with his fellow human beings (mutants included) seem to be, he also has a deep understanding of the human mind/psychology, which is what enables him to pull off these intricate mind tricks. and more importantly...

he watches and learns.

and we get the sense that he does this deliberately, like much of everything he does.

here is a moment i missed in my first reading: in [legacy #218], charles was facing off against claudine renko, aka miss sinister. miss sinister was one of sinister’s “hosts” and possessed similar psychic abilities. she was able to get the drop on xavier when xavier broke into her mansion. she attacked him with all sorts of mental tricks/illusions for about 1.5 page before he revealed that -- all along -- he’s got one of her psi-shield gadgets on him and used it to bypass her psychic assault.

something felt off about it but i couldn’t put my finger on it the first time reading it, until i realized... if he had the psi-shield all along, why did he let her attack his mind at all? why not have it activated the whole time and save the trouble?

a possible explanation seems to be that... he wanted to see what she’d do? he wanted to get her to show her hand and show herself -- which she did, letting on to him that she’s a host of mister sinister. and then, and only then, did he fight back and subdue her.

she should’ve learned from his previous battle with her original, mister sinister. it’s kind of a consistent thing that charles adjusts and gets better in psychic battles the longer they drag on.

in [legacy #214], he was locked in heated combat with mister sinister on the astral plane. and by all means he was losing. bad.

sinister was pulling out all the stops and weaponizing all of his past failures, regrets, angst, and humiliations against him. which all culminated in... onslaught.

what should’ve been the climax or the final blow ended up being the turning point where charles regained control and pushed sinister out of his mind and body (oh yeah sinister was trying to take over his body/mind in a ploy to resurrect himself forgot to mention that).... because it’s too obvious

...,,which.. . wt f yo mean tOo obvioSu?1!?!?

basically what i got out of this, and the totality of evidence, is that charles xavier is a tactician. once he knows what your game is/what you’re doing, he will figure out a way to counter it. whatever it takes.

whatever it takes.

[astonishing x-men (2017) #5] showed the epic battle between shadow king and charles xavier which ended in xavier’s last pre-krakoa resurrection via fantomex’s body (long story).

it’s a whole feat onto itself and i recommend people reading it, especially the 2017 annual #1 which further illustrates my point about charles’ psychic manipulation.

but the key point here is, he will throw everything at the problem -- and he never plays only one game at a time.

most importantly, he constructs a narrative. he doesn’t just make you do the thing he wants you to do, he gives you a reason as to why you’re doing it. a story. a history. an entire dollhouse that makes everything make sense... until it doesn’t.

it plays with all of your senses (possibly, but also not all the time. which ones do you rely on?), at multiple levels (it goes deeper than you thought, but by hitting the bottom you only discover how far he’s strung you along), and started way before you were ready, or even realized.

it shatters you by making you fundamentally question your relationship with reality. that’s what makes his use of psychic powers feel so intricate, elaborate, and so -- back to the central thesis of this post -- violating.

#( reference ) read comics.#( meta ) data.#long post#...anyway#read this also as my love letter to some of my favorite books lol

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anarchist FAQ/What is Anarchism?/2.17<

Anarchist FAQ

|

What is Anarchism?

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

A.2.17 Aren't most people too stupid for a free society to work?

We are sorry to have to include this question in an anarchist FAQ, but we know that many political ideologies explicitly assume that ordinary people are too stupid to be able to manage their own lives and run society. All aspects of the capitalist political agenda, from Left to Right, contain people who make this claim. Be it Leninists, fascists, Fabians or Objectivists, it is assumed that only a select few are creative and intelligent and that these people should govern others. Usually, this elitism is masked by fine, flowing rhetoric about "freedom," "democracy" and other platitudes with which the ideologues attempt to dull people's critical thought by telling them want they want to hear.

It is, of course, also no surprise that those who believe in "natural" elites always class themselves at the top. We have yet to discover an "objectivist", for example, who considers themselves part of the great mass of "second-handers" (it is always amusing to hear people who simply parrot the ideas of Ayn Rand dismissing other people so!) or who will be a toilet cleaner in the unknown "ideal" of "real" capitalism. Everybody reading an elitist text will consider him or herself to be part of the "select few." It's "natural" in an elitist society to consider elites to be natural and yourself a potential member of one!

Examination of history shows that there is a basic elitist ideology which has been the essential rationalisation of all states and ruling classes since their emergence at the beginning of the Bronze Age ("if the legacy of domination had had any broader purpose than the support of hierarchical and class interests, it has been the attemp to exorcise the belief in public competence from social discourse itself." [Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom, p. 206]). This ideology merely changes its outer garments, not its basic inner content over time.

During the Dark Ages, for example, it was coloured by Christianity, being adapted to the needs of the Church hierarchy. The most useful "divinely revealed" dogma to the priestly elite was "original sin": the notion that human beings are basically depraved and incompetent creatures who need "direction from above," with priests as the conveniently necessary mediators between ordinary humans and "God." The idea that average people are basically stupid and thus incapable of governing themselves is a carry over from this doctrine, a relic of the Dark Ages.

In reply to all those who claim that most people are "second-handers" or cannot develop anything more than "trade union consciousness," all we can say is that it is an absurdity that cannot withstand even a superficial look at history, particularly the labour movement. The creative powers of those struggling for freedom is often truly amazing, and if this intellectual power and inspiration is not seen in "normal" society, this is the clearest indictment possible of the deadening effects of hierarchy and the conformity produced by authority. (See also section B.1 for more on the effects of hierarchy). As Bob Black points outs:

"You are what you do. If you do boring, stupid, monotonous work, chances are you'll end up boring, stupid, and monotonous. Work is a much better explanation for the creeping cretinisation all around us than even such significant moronising mechanisms as television and education. People who are regimented all their lives, handed to work from school and bracketed by the family in the beginning and the nursing home in the end, are habituated to hierarchy and psychologically enslaved. Their aptitude for autonomy is so atrophied that their fear of freedom is among their few rationally grounded phobias. Their obedience training at work carries over into the families they start, thus reproducing the system in more ways than one, and into politics, culture and everything else. Once you drain the vitality from people at work, they'll likely submit to hierarchy and expertise in everything. They're used to it."—Bob Black, The Abolition of Work and other essays, pp. 21-2

When elitists try to conceive of liberation, they can only think of it being given to the oppressed by kind (for Leninists) or stupid (for Objectivists) elites. It is hardly surprising, then, that it fails. Only self-liberation can produce a free society. The crushing and distorting effects of authority can only be overcome by self-activity. The few examples of such self-liberation prove that most people, once considered incapable of freedom by others, are more than up for the task.

Those who proclaim their "superiority" often do so out of fear that their authority and power will be destroyed once people free themselves from the debilitating hands of authority and come to realise that, in the words of Max Stirner, "the great are great only because we are on our knees. Let us rise"

As Emma Goldman remarks about women's equality, "[t]he extraordinary achievements of women in every walk of life have silenced forever the loose talk of women's inferiority. Those who still cling to this fetish do so because they hate nothing so much as to see their authority challenged. This is the characteristic of all authority, whether the master over his economic slaves or man over women. However, everywhere woman is escaping her cage, everywhere she is going ahead with free, large strides." [Vision on Fire, p. 256] The same comments are applicable, for example, to the very successful experiments in workers' self-management during the Spanish Revolution.

Then, of course, the notion that people are too stupid for anarchism to work also backfires on those who argue it. Take, for example, those who use this argument to advocate democratic government rather than anarchy. Democracy, as Luigi Galleani noted, means "acknowledging the right and the competence of the people to select their rulers." However, "whoever has the political competence to choose his [or her] own rulers is, by implication, also competent to do without them, especially when the causes of economic enmity are uprooted." [The End of Anarchism?, p. 37] Thus the argument for democracy against anarchism undermines itself, for "if you consider these worthy electors as unable to look after their own interests themselves, how is it that they know how to choose for themselves the shepherds who must guide them? And how will they be able to solve this problem of social alchemy, of producing the election of a genius from the votes of a mass of fools?" [Malatesta, Anarchy, pp. 53–4]

As for those who consider dictatorship as the solution to human stupidity, the question arises why are these dictators immune to this apparently universal human trait? And, as Malatesta noted, "who are the best? And who will recognise these qualities in them?" [Op. Cit., p. 53] If they impose themselves on the "stupid" masses, why assume they will not exploit and oppress the many for their own benefit? Or, for that matter, that they are any more intelligent than the masses? The history of dictatorial and monarchical government suggests a clear answer to those questions. A similar argument applies for other non-democratic systems, such as those based on limited suffrage. For example, the Lockean (i.e. classical liberal or right-wing libertarian) ideal of a state based on the rule of property owners is doomed to be little more than a regime which oppresses the majority to maintain the power and privilege of the wealthy few. Equally, the idea of near universal stupidity bar an elite of capitalists (the "objectivist" vision) implies a system somewhat less ideal than the perfect system presented in the literature. This is because most people would tolerate oppressive bosses who treat them as means to an end rather than an end in themselves. For how can you expect people to recognise and pursue their own self-interest if you consider them fundamentally as the "uncivilised hordes"? You cannot have it both ways and the "unknown ideal" of pure capitalism would be as grubby, oppressive and alienating as "actually existing" capitalism.

As such, anarchists are firmly convinced that arguments against anarchy based on the lack of ability of the mass of people are inherently self-contradictory (when not blatantly self-servicing). If people are too stupid for anarchism then they are too stupid for any system you care to mention. Ultimately, anarchists argue that such a perspective simply reflects the servile mentality produced by a hierarchical society rather than a genuine analysis of humanity and our history as a species. To quote Rousseau:

"when I see multitudes of entirely naked savages scorn European voluptuousness and endure hunger, fire, the sword, and death to preserve only their independence, I feel that it does not behove slaves to reason about freedom."—Rousseau, quoted by Noam Chomsky, Marxism, Anarchism, and Alternative Futures, p. 780

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Little Caesar (1931)

For a brief window in the early 1930s, Hollywood studios churned out a small flurry of gangster films that would define the genre into the present day. Among those influential progenitors was Mervyn LeRoy’s Little Caesar, released by Warner Bros. With Little Caesar, Warner Bros. was about to assume an identity of being the “dark” studio – greenlighting socially conscious films replete with human depravity and cynicism towards authority figures or, you know, gangster films where the police are given no nobility. Little Caesar, based on W.R. Burnett’s novel of the same name and adapted by Francis Edward Faragoh, Robert Lord, and future 20th Century Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck, is best remembered today as the film that made Edward G. Robinson a Hollywood superstar. Robinson and Little Caesar, as a film, resembled nothing moviegoers had seen before and demand for these movies – to the horror of state and local censors and special-interest morality groups – skyrocketed.

Audiences, in the opening throes of the Depression, admired these gangsters for their craftiness in assuaging their living conditions in dire economic times while hoping for their demise. Gangster films were an expression of wrath – bottled up within Western audiences due to the obvious costs of such behavior, but fully unleashed within the confines of fiction. That wrath could be consuming for characters in these films, and was often directed at the police, politicians (at any level of government), and other crime bosses with the gall to impose their own rules on a main character. By the end of the decade, this appealing aura would be reversed by the Hays Code – a set of guidelines by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) created in 1930, not fully enforced until 1934, and replaced with the MPAA ratings system in the United States in 1968 – by turning gangsters into unflattering personalities or shifting the narrative to the police attempting to capture the criminals.

Caesar Enrico “Rico” Bandello (Robinson) starts out as a minor criminal in the lower Midwest, along with friend Joe Massara (Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.). Discontent with their fortunes, they travel to Chicago – Rico joins Sam Vettori’s (Stanley Fields) gang while Joe pursues a long-held dream of being a dancer. Rico wants to help Joe rise through the gang’s hierarchy, but Joe declines when he learns the next heist is at the Bronze Peacock – the dinner-and-a-show establishment where he works. The friends go their separate ways, with Joe heeding his dance partner Olga’s (Glenda Farrell) words to leave the gangster lifestyle. At the Bronze Peacock, Rico – against the orders of “Big Boy” (Sidney Blackmer) – hails the Chicago police commissioner with a fatal gunshot. Open gang war has broken out in Chicago’s Northside, Rico believes Joe knows too much about what he has done, and friendships and fates will be determined in the film’s closing acts.

In supporting roles are William Collier, Jr.; Ralph Ince; Thomas E. Jackson as a police sergeant; Maurice Black as a rival boss; and George E. Stone as one of Rico’s henchpersons.

For modern audiences, one of the most glaring impediments to investing oneself into Little Caesar is the clunky acting from everyone who is not Edward G. Robinson (Fairbanks, Jr. feels like he is simply reading lines too often; Farrell is in her first credited feature film and will grow into her reputation as the wisecracking blonde in later comedies and musicals). The dialogue is delivered in stilted fashion, with theatrical voices being used in every scene (this is a legacy of the silent era, as actors and filmmakers were still trying to adapt themselves to synchronized sound – if Little Caesar was a silent film, I would be calling the acting anything but “clunky”). Despite this, the friendship between Rico and Joe feels like it existed even before the first minute of the film begins.

As a pre-Code film, Rico and Joe’s friendship also contains potential homoerotic subtext – Rico is completely dismissive of women as objects of sexual attraction (opens the possibility of other subtexts), he criticizes Joe’s attraction to Olga, almost always keeps his hands on his gun (concealed or otherwise) when rival men are around, the two are complete opposites but want the other to reform their ways, and Joe is the only person in the film that Rico can share his private ideas and life with. This subtext was overwhelming to ‘30s audiences, forcing W.R. Burnett (the author of the novel) to write a lambasting letter to the producers about the “conversion” of his originally and explicitly heterosexual title character. No matter Burnett’s complaints, the fact that the screenwriting team of Faragoh, Lord, and Zanuck packages this convincing friendship (or whatever it is) within a seventy-nine-minute runtime is an impressive achievement. It is also impossible without the performances of Robinson and, to a lesser extent, the junior Douglas Fairbanks.

Robinson, along with James Cagney, defined gangster films of the 1930s. Their relatively short stature – Robinson was 5′7″, Cagney 5′5″ – does not suggest a domineering physical presence on paper. But as Rico, Robinson is a fearsome menace constantly compensating for something. Rico cares little – but understands completely – about the ramifications of violence on society, friends, and families. Unlike many gangsters that would follow him, he is not seen under the influence of harder drugs or alcohol – he commits all his schemes and homicides sober. He does not have the athletic or imposing build of later gangsters, nor the cadence to force someone holding up their hands before their lights are turned off to piss their pants. Without any of this, Rico bathes himself in violence, committed to never being cuffed by the cops while still breathing (a promise to himself and the police that he exclaims several times, beaming with pleasure). His intelligence has justified killings in the name of gang loyalty and the familial structure it provides. His instincts allow him to evade capture and death from the hands of the police and rival hoodlums for a time, becoming the most feared – and, in a perverse way, admired – gangster of the Windy City.

Little Caesar does not have the scope of a gangster film directed by Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather trilogy) or a Martin Scorsese (1990′s GoodFellas, 2006′s The Departed). Many of the clichés found in the genre have not been codified yet but appear in this film: the small-time ruffian who shoots his way to the top, the friend of said ruffian attempting to escape a life of crime before meeting an end that involves the gallows or gunfire, the girlfriend who wants their man to stop working with the gang, the intransigent crime boss too set in their ways to prevent their usurpation, the rival crime bosses who instantly recognize the upstart as a destabilizing force in the balance of gang power, the police figures gunned down to kickstart what will lead to the film’s climax. All those aspects appear in Little Caesar – omitting, for the purposes of this review and in respect for those who have not seen the film, clichés in gangster movie finales. The gangster picture, in its concentration on violent masculinity, is one of the least versatile genres innovated by Hollywood. The blame for that dearth of narrative versatility should not be assigned to films that appeared before those tropes became tropes.

With film noir the eventual successor to the early 1930s gangster films, Little Caesar does not have the chiaroscuro lighting that would define film noir. Nevertheless, some of the imagery from cinematographer Tony Gaudio (1936′s Anthony Adverse, 1938′s The Adventures of Robin Hood) breathes grittiness and even a hint of tragedy to this set-bound production when the action is not set indoors. Otherwise, Little Caesar is not imaginatively shot for long stretches. With only one chilling exception, the lack of close-ups almost prevents Robinson, as Rico, from establishing invisible bounds that his subordinates dare not cross.

Though this review, among most all others one could find on Little Caesar, has waxed about Edward G. Robinson’s violent-with-a-smile performance, Robinson himself was squeamish to the sound of gunshots. In the rushes, LeRoy and editor Ray Curtiss noticed, “Every time he squeezed the trigger, he would screw up his eyes. Take after take, he would do the same thing.” To resolve this, Robinson’s eyelids – in any scenes that involved Rico firing his guns – would be taped. Robinson, by all accounts, was anything but Caesar Enrico Bandello or any other of the gangsters he would portray on-screen. The immigrant son of a Romanian Jewish family, Emanuel Goldenberg was a fine arts lover who spoke to and of others with gentleness. He was more of a Christopher Cross from Scarlet Street (1945) or, maybe, a Martinius Jacobson from Our Vines Have Tender Grapes (1945).

Robinson would take on gangster roles – comedies and dramas – until Never a Dull Moment (1968). Somewhat typecast as the tough gangster in the coming decades, few other Robinson performances were as frightening as this. For almost that performance alone, Little Caesar is one of the most important and accomplished films of the early 1930s. It is not the first gangster film ever made, but the gangster film playbook that it wrote – alongside the other great gangster pictures shortly to follow it – has undergone few sweeping revisions since its release.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Little Caesar#Mervyn LeRoy#Edward G. Robinson#Douglas Fairbanks Jr.#Glenda Farrell#William Collier Jr.#Sidney Blackmer#Ralph Ince#Thomas E. Jackson#Stanley Fields#Maurice Black#George E. Stone#Francis Edward Faragoh#Robert Lord#Darryl F. Zanuck#Hal B. Wallis#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet Four Craft Chocolate Makers Decolonizing the Industry

Jill Fannon/Eater

Chocolate makers Jinji Fraser, Karla McNeil-Rueda, Damaris Ronkanen, and Daniel Maloney on how ancestry informs what they do, and how to eradicate cultural erasure in the industry

Over a perfect omelet brimming with spring ramps and morels, I found myself stunned mid-chew as I listened to the words of my father. Moments earlier, I learned from him that my grandfather’s final bit of travel before he died was to Guyana, where our ancestors had lived, and where he had arranged to meet with a distant family member. Between bites, my dad continued, “there’s a Fraser family land trust outside of Georgetown...”

As a student of geography, I knew the region he’d begun to describe to be a major coastal export hub of Guyanese hinterland treasures, like gold, diamonds, and rice. As a chocolate maker, I knew Georgetown to be just west of cacao-rich rainforest. And right there, as I absently mopped up omelet sweat with a hunk of crusty bread, I felt the dissolution of the intimidation I had often felt while making chocolate in a male, white-dominant landscape. Our family land signified an ancestral connection to the greater sacred cacao story, which I suddenly found myself belonging to, creating a new grounding in my career. No longer was my work a radical dissent from the mainstream. It was now an homage to all who had come before me, passed down from generations ago through my DNA, and into my hands.

Even as my own story continues to unfold — through family lineage research and eventual travel to Guyana to see what has come of our land — I became fascinated with the ethnic diversity of the craft chocolate industry. I began to wonder about the ancestral rites of passage by BIPOCs (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) whose inclusion and celebration as chocolate makers has been marginalized in the media while the contributions of white men are normalized and bolstered. The narrow lens through which craft chocolate is seen is not only to the detriment of Indigenous chocolate makers globally, but also robs consumers of the chacne to experience the multitude of ways chocolate is produced. Healing the short-sightedness of our already fragile industry works toward universal fair-trade practices, equitable treatment of women farmers and producers, and the celebration of the work of BIPOC makers worldwide.

I spoke with Karla McNeil-Rueda (Cru Chocolate), who focuses on drinking chocolate, drawing from her own family experience while bringing attention to the undeniable influence of Mesoamerican heritage on the chocolate industry. Damaris Ronkanen (Cultura Craft Chocolate) also brought family nostalgia to our discussion, grounding herself solidly in community activism by educating the youth in chocolate making. Finally, I talked with Daniel Maloney (Sol Cacao), whose Trinidadian roots inspire him to continue his family lineage in cacao, as well as encourage an industrywide commitment to fair-trade practices. Altogether, we investigate how ancestry informs what they do and how they do it, as well as how we might eradicate cultural erasure in chocolate making, creating visibility and opportunity for more diversity.

The following interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Karla McNeil-Rueda

Co-Founder, Cru Chocolate, Sacramento, California

Eater: Did you find chocolate, or did chocolate find you?

Karla McNeil-Rueda: A bit of both. Chocolate, and cacao to be more specific, has always been here; it’s part of who we are, like corn, like a family member — it’s part of our DNA. Growing up in Honduras, we had many cacao- and chocolate-based drinks in different seasons with as many names as there were flavors, so this is a big part of our diet.

Keba Konte, courtesy McNeil-Rueda

Karla McNeil-Rueda

In the U.S., the chocolate-making space is dominated by white men. How do you find your own way?

Yes, it is true that what most people understand as chocolate making in the U.S. is represented mostly by white men, but we have no interest in fitting into that category. What they call chocolate is different to us; chocolate is our heritage and part of what we are. It is health, pleasure, an everyday ritual, a state of mind and a way of being. So we will never find our way in the chocolate industry; we must remain true to our own way. Chocolate in the U.S. and Europe needs the romance and the exotic appeal of a faraway land. For us, those lands are our homes, and that makes a big difference in our approach.

We also choose to only work with people who think differently, and [who] value the contribution of small and local businesses. These are people who also want to work with us, and don’t need to receive a container full of cacao in order to feel fulfilled — just how I don’t need to have a mega factory in order to find value in my work. It takes more time, more phone calls, more resources, more fun, more humanity, more everything — but that is what I love, that is the joy of freedom.

How does your ancestry inform what you do and the way you do it?

For me, ancestry is made up of the seeds and foods that fed those before us, including the agreements they made and work that they did in keeping each other alive through thousands and thousands of years.

So as we cook, our kitchens can become temples and our pantries can transform into altars, which opens our space for the feelings, emotions, memories and questions that arise. That is why I like to cook with music. It helps me have a sensibility,

This is how I feel my ancestry speaks, through food and especially through cacao. I notice how my thoughts change as the roasting or the grinding changes. We can better accompany our foods by listening as they go through these changes, because in the same way, they have accompanied us as we experience change in our daily lives.

How do we reconcile being chocolate makers when the industry is still entrenched in colonialism?

I think that the industry as a whole is dominated by many people, many colors, and many genders across the supply chain. There are many white women replicating colonial systems here in the U.S., and there are also many brown men enforcing this system at the farm level. The lack of fairness and equal opportunity in the chocolate industry has its roots in extraction, and that thrives in separation and in the erasing of others.

Import and export of crops are entrenched in colonialism, but cacao is an ancient native food, so you can also find many people still growing and making chocolate who are originally from the land in which cacao grows.

Colonialism is real, but so are the Indigenous people of these places. They are alive and thriving even with an imposed system, because they belong there. Colonialism is strong, but I believe our ancestral ways are stronger. We must have faith in the survival of these Indigenous groups; we must look for them, we must awaken a sincere desire for them to thrive.

It requires work, time, relationships, knowing each other’s culture, knowing each other’s languages, and courtship. That’s why colonialism is so appealing to many: You don’t have to know anything in order to participate and make money. A big lie of colonialism is the belief that there are no buying options; there’s only one way, the original people are gone, and what’s left is the colony. This is not true.

How do we create more diversity in the chocolate-making world?

First we must acknowledge the chocolate-making world is very diverse. In any city where you find immigrants from Mesoamerica, I guarantee you they are making chocolate.

That said, why is it easy for people to recognize a white man who had never seen a cacao tree before becoming a chocolate maker? And what makes it so hard to see a woman from Mesoamerica who has been making chocolate for generations as a chocolate maker? Why do people celebrate one and condemn the other?

I think when people rethink chocolate ... things will change. As long as people only chase the industrial candy bar, the craft chocolate bar, or the sugar- and cream-filled bon-bons, chocolate as a way of living among BIPOC will remain invisible. Misrepresenting chocolate creates social, environmental, and cultural problems, which at their core create disease and poverty for farmers and consumers.

Daniel Maloney

Co-Founder, Sol Cacao, the Bronx, New York

Courtesy Sol Cacao

Sol Cacao co-founders and brothers Dominic, Nicholas, and Daniel Maloney

Eater: Did you find chocolate, or did chocolate find you?

Daniel Maloney: At Sol Cacao, we believe chocolate found us. Growing up in Trinidad and Tobago, one of our most memorable moments was our grandmother carrying a basket of vegetables in both hands and a bowl of herbs balancing on her head. She would do this ritual everyday, even after turning 99. She would show my brothers and I all the vegetables she would pick, and their nutritional benefits. These early memories would leave a major impression and seed our interest in food security and sustainable and renewable agriculture. Before my brothers and I enrolled in college, our father began telling stories of our grandparents and how they practiced farming for over 35 years. Their favorite crops were sugarcane and the cacao tree. After learning these stories, we saw it in ourselves that we are capable of being cocoa farmers or chocolate makers.

How do you stay grounded in your craft, and navigate the persistent colonialism in the chocolate industry?

When we launched Sol Cacao, there were few people of color in the industry, so we had no choice but to jump into it and learn the process. We would dream about someday being on a cacao farm and picking the beans to make chocolate, a dream our grandparents were never able to fully realize for themselves. For these reasons we viewed chocolate making as a culture and family legacy, which gave us inspiration to pave our own way in the chocolate industry.

As a chocolate maker in the 21st century, we carry the responsibility to correct some of the historical injustices which have taken place in the cacao industry. One way chocolate makers are doing this is through traceability and transparency in their chocolate-making process. It starts with where and how the cacao beans are grown and harvested by sourcing organic or fair-trade cacao. Through purchasing fair-trade cacao, we ensure the cacao farmers get the correct compensation to have a livable wage to make change back in their local communities, to global effect.

Damaris Ronkanen

Founder, Cultura Craft Chocolate, Denver, Colorado

Eater: What family memories have informed your perception of chocolate?

Damaris Ronkanen: My abuelita would always have fresh tortillas and atole in the morning. She would get up early and take her nixtamal [cooked corn] to the molino, where they would grind the corn into fresh masa. When she came back she would make tortillas by hand and use a little bit of the masa to make a fresh batch of atole. Whenever I was there she always made sure to make champurrado (a chocolate atole) since she knew it was my favorite. She would toast cacao beans on her comal and grind them by hand using her metate. She would then blend the chocolate into the steaming hot atole and use her molinillo to whisk it until it was super frothy. The process was mesmerizing.

Juan Fuentes, courtesy Ronkanen

Damaris Ronkanen

Unfortunately, I could never replicate this to be quite the same when I was back in the U.S. There weren’t molinos to grind your corn, and people didn’t make their own nixtamal, and there definitely weren’t cacao beans freshly toasted and ground by hand.

How has your business model evolved since its inception?

When we started out making chocolate, the big guys of the chocolate-making industry defined what craft chocolate was, so we felt the pressure to make bars in order to succeed. Still, I was pulled by my Mexican roots, and the memories of market visits and fresh champurrado with my grandmother.

There was a huge difference between my grandmother’s texture and European texture. When we officially started Cultura, I wanted to get back to my heritage, so we introduced drinking chocolate. I knew in order to honor my grandmother, and to move my business forward, I would need to define what I was doing on my own terms and decide what impact my business could have on my community. As successful as the bars were at the wholesale level, they weren’t speaking to my soul.

What is your approach in how you communicate about chocolate in your work?

After experiencing such a pivotal moment in 2018, opening Cultura, connecting with my roots helped define not only what I wanted to create, but how I talk about chocolate too. Our local community in Westwood is composed largely of Mexican immigrants, and we made it part of our mission to create a non-intimidating space where families could feel at home with familiar flavors. They might not immediately connect with the single-origin bars we offer, but they definitely get excited about the drinking chocolate, which opens a door to educate about origin, terroir, and processing.

Even in the way we designed our logo, and chose a mural for the outside of our building, people in the community feel welcome. It becomes a true form of empowerment for our community when they take part in hands-on classes, teaching everything from where the cacao originates to making beverages to explaining what the molinillos they may have seen around their grandparents’ houses are actually used for.

How have you been able to find success while avoiding the elitist mentality around chocolate making?

We focus on culturally relevant chocolates. I’ve learned to not try and emulate the style of chocolates other companies were making, but instead to make chocolate that our community appreciates, and that highlights my heritage. Without having real experience, these other companies construct their narratives around their sourcing, creating a false reality of how much impact they really have on the groups of people they feature on their social media feeds. These stories are used for marketing and to drive up pricing. There’s a certain elitism in craft-chocolate making that fetishizes authenticity through communication and packaging in order to make their product accessible for white people.

We don’t have the influence and reach of these other companies, but that isn’t the goal either. It has taken a lot of effort for people to understand why we do things the way we do, but I’ve always known there was so much more my business is capable of in terms of making chocolate accessible and engaging our community.

How can we leave the door open to create more diversity in the chocolate making world?

The question we’ve always asked of ourselves is: What impact can our company have? A conversation I would like to see happen is of the limited entrepreneurial spirit and access in America. In Mexico, the opportunity is available to everyone to continue family traditions in business. Here, there is a lot of intimidation and difficulty in making your own path. So in order to positively influence this issue, we exclusively hire women from within the community. We offer classes to youth who otherwise don’t have access to craft chocolate — this is their space too. We are bilingual, so there aren’t any language barriers to learning or curiosity.

Jill Fannon/Eater

Jinji Fraser

Jill Fannon/Eater

The lingering question is: What actionable steps might we take to inspire a new generation of BIPOC chocolate makers, and how can they feel justified in exploring the craft of chocolate making in their own ways without intimidation or judgment?

“BIPOC makers need to organize and create their own BIPOC chocolate makers association, in which we spend time and resources educating, supporting, and uplifting each other, and where many ways of expressing chocolate can coexist,” McNeil-Rueda says. As for me, my earliest experience in chocolate making was at the International Chocolate Show in Paris in 2012. I learned then, and have known through my career, that an impeccable bar is one whose texture is smooth and melt is indiscernible from one’s own body temperature. Perfection and accolades are both sought through thousands of dollars of stainless-steel equipment and, importantly, an agreement and an eidetic memory of European technique.

My most recent experience of chocolate making in Guatemala was categorically different, and wildly more satiating: Indigenous women slow-roasting beans over an open flame, then hulling them using friction and the wind, before using a molcajete to grind the beans into a paste heavy with grit and fragments of all the cacao ever to pass that stone bowl, ready for drinking. In that moment of awed observation, I felt that this technique and experience should be allowed to live in those Highlands, and with their descendants; respected without appropriation, lauded with curiosity and intrigue. I knew it was upon me to discover what methods and practices are innate to me, and then to educate my community on a broader vision of good chocolate.

As it relates to chocolate, one should be able to choose their pleasure. However, this is not a journey that can be void of education. There must be support for the idea that chocolate takes on many different forms, and freedom for each form to exist means respect for all who make it. “Positions of leadership in craft chocolate companies should be held by Black and brown people in order to heal the whitewashing of our cultural roots,” says Ronkanen. Indeed, that would be a collective effort to decolonize chocolate and acknowledge the ancestral pathways critical to making the industry whole.

Jinji Fraser is a Baltimore-based writer and chocolate-maker at Pure Chocolate by Jinji.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3kgZVpA https://ift.tt/3m5Q9qO

Jill Fannon/Eater

Chocolate makers Jinji Fraser, Karla McNeil-Rueda, Damaris Ronkanen, and Daniel Maloney on how ancestry informs what they do, and how to eradicate cultural erasure in the industry

Over a perfect omelet brimming with spring ramps and morels, I found myself stunned mid-chew as I listened to the words of my father. Moments earlier, I learned from him that my grandfather’s final bit of travel before he died was to Guyana, where our ancestors had lived, and where he had arranged to meet with a distant family member. Between bites, my dad continued, “there’s a Fraser family land trust outside of Georgetown...”

As a student of geography, I knew the region he’d begun to describe to be a major coastal export hub of Guyanese hinterland treasures, like gold, diamonds, and rice. As a chocolate maker, I knew Georgetown to be just west of cacao-rich rainforest. And right there, as I absently mopped up omelet sweat with a hunk of crusty bread, I felt the dissolution of the intimidation I had often felt while making chocolate in a male, white-dominant landscape. Our family land signified an ancestral connection to the greater sacred cacao story, which I suddenly found myself belonging to, creating a new grounding in my career. No longer was my work a radical dissent from the mainstream. It was now an homage to all who had come before me, passed down from generations ago through my DNA, and into my hands.

Even as my own story continues to unfold — through family lineage research and eventual travel to Guyana to see what has come of our land — I became fascinated with the ethnic diversity of the craft chocolate industry. I began to wonder about the ancestral rites of passage by BIPOCs (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) whose inclusion and celebration as chocolate makers has been marginalized in the media while the contributions of white men are normalized and bolstered. The narrow lens through which craft chocolate is seen is not only to the detriment of Indigenous chocolate makers globally, but also robs consumers of the chacne to experience the multitude of ways chocolate is produced. Healing the short-sightedness of our already fragile industry works toward universal fair-trade practices, equitable treatment of women farmers and producers, and the celebration of the work of BIPOC makers worldwide.

I spoke with Karla McNeil-Rueda (Cru Chocolate), who focuses on drinking chocolate, drawing from her own family experience while bringing attention to the undeniable influence of Mesoamerican heritage on the chocolate industry. Damaris Ronkanen (Cultura Craft Chocolate) also brought family nostalgia to our discussion, grounding herself solidly in community activism by educating the youth in chocolate making. Finally, I talked with Daniel Maloney (Sol Cacao), whose Trinidadian roots inspire him to continue his family lineage in cacao, as well as encourage an industrywide commitment to fair-trade practices. Altogether, we investigate how ancestry informs what they do and how they do it, as well as how we might eradicate cultural erasure in chocolate making, creating visibility and opportunity for more diversity.

The following interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Karla McNeil-Rueda

Co-Founder, Cru Chocolate, Sacramento, California

Eater: Did you find chocolate, or did chocolate find you?

Karla McNeil-Rueda: A bit of both. Chocolate, and cacao to be more specific, has always been here; it’s part of who we are, like corn, like a family member — it’s part of our DNA. Growing up in Honduras, we had many cacao- and chocolate-based drinks in different seasons with as many names as there were flavors, so this is a big part of our diet.

Keba Konte, courtesy McNeil-Rueda

Karla McNeil-Rueda

In the U.S., the chocolate-making space is dominated by white men. How do you find your own way?

Yes, it is true that what most people understand as chocolate making in the U.S. is represented mostly by white men, but we have no interest in fitting into that category. What they call chocolate is different to us; chocolate is our heritage and part of what we are. It is health, pleasure, an everyday ritual, a state of mind and a way of being. So we will never find our way in the chocolate industry; we must remain true to our own way. Chocolate in the U.S. and Europe needs the romance and the exotic appeal of a faraway land. For us, those lands are our homes, and that makes a big difference in our approach.

We also choose to only work with people who think differently, and [who] value the contribution of small and local businesses. These are people who also want to work with us, and don’t need to receive a container full of cacao in order to feel fulfilled — just how I don’t need to have a mega factory in order to find value in my work. It takes more time, more phone calls, more resources, more fun, more humanity, more everything — but that is what I love, that is the joy of freedom.

How does your ancestry inform what you do and the way you do it?

For me, ancestry is made up of the seeds and foods that fed those before us, including the agreements they made and work that they did in keeping each other alive through thousands and thousands of years.

So as we cook, our kitchens can become temples and our pantries can transform into altars, which opens our space for the feelings, emotions, memories and questions that arise. That is why I like to cook with music. It helps me have a sensibility,

This is how I feel my ancestry speaks, through food and especially through cacao. I notice how my thoughts change as the roasting or the grinding changes. We can better accompany our foods by listening as they go through these changes, because in the same way, they have accompanied us as we experience change in our daily lives.

How do we reconcile being chocolate makers when the industry is still entrenched in colonialism?

I think that the industry as a whole is dominated by many people, many colors, and many genders across the supply chain. There are many white women replicating colonial systems here in the U.S., and there are also many brown men enforcing this system at the farm level. The lack of fairness and equal opportunity in the chocolate industry has its roots in extraction, and that thrives in separation and in the erasing of others.

Import and export of crops are entrenched in colonialism, but cacao is an ancient native food, so you can also find many people still growing and making chocolate who are originally from the land in which cacao grows.

Colonialism is real, but so are the Indigenous people of these places. They are alive and thriving even with an imposed system, because they belong there. Colonialism is strong, but I believe our ancestral ways are stronger. We must have faith in the survival of these Indigenous groups; we must look for them, we must awaken a sincere desire for them to thrive.

It requires work, time, relationships, knowing each other’s culture, knowing each other’s languages, and courtship. That’s why colonialism is so appealing to many: You don’t have to know anything in order to participate and make money. A big lie of colonialism is the belief that there are no buying options; there’s only one way, the original people are gone, and what’s left is the colony. This is not true.

How do we create more diversity in the chocolate-making world?

First we must acknowledge the chocolate-making world is very diverse. In any city where you find immigrants from Mesoamerica, I guarantee you they are making chocolate.

That said, why is it easy for people to recognize a white man who had never seen a cacao tree before becoming a chocolate maker? And what makes it so hard to see a woman from Mesoamerica who has been making chocolate for generations as a chocolate maker? Why do people celebrate one and condemn the other?

I think when people rethink chocolate ... things will change. As long as people only chase the industrial candy bar, the craft chocolate bar, or the sugar- and cream-filled bon-bons, chocolate as a way of living among BIPOC will remain invisible. Misrepresenting chocolate creates social, environmental, and cultural problems, which at their core create disease and poverty for farmers and consumers.

Daniel Maloney

Co-Founder, Sol Cacao, the Bronx, New York

Courtesy Sol Cacao

Sol Cacao co-founders and brothers Dominic, Nicholas, and Daniel Maloney

Eater: Did you find chocolate, or did chocolate find you?

Daniel Maloney: At Sol Cacao, we believe chocolate found us. Growing up in Trinidad and Tobago, one of our most memorable moments was our grandmother carrying a basket of vegetables in both hands and a bowl of herbs balancing on her head. She would do this ritual everyday, even after turning 99. She would show my brothers and I all the vegetables she would pick, and their nutritional benefits. These early memories would leave a major impression and seed our interest in food security and sustainable and renewable agriculture. Before my brothers and I enrolled in college, our father began telling stories of our grandparents and how they practiced farming for over 35 years. Their favorite crops were sugarcane and the cacao tree. After learning these stories, we saw it in ourselves that we are capable of being cocoa farmers or chocolate makers.

How do you stay grounded in your craft, and navigate the persistent colonialism in the chocolate industry?

When we launched Sol Cacao, there were few people of color in the industry, so we had no choice but to jump into it and learn the process. We would dream about someday being on a cacao farm and picking the beans to make chocolate, a dream our grandparents were never able to fully realize for themselves. For these reasons we viewed chocolate making as a culture and family legacy, which gave us inspiration to pave our own way in the chocolate industry.

As a chocolate maker in the 21st century, we carry the responsibility to correct some of the historical injustices which have taken place in the cacao industry. One way chocolate makers are doing this is through traceability and transparency in their chocolate-making process. It starts with where and how the cacao beans are grown and harvested by sourcing organic or fair-trade cacao. Through purchasing fair-trade cacao, we ensure the cacao farmers get the correct compensation to have a livable wage to make change back in their local communities, to global effect.

Damaris Ronkanen

Founder, Cultura Craft Chocolate, Denver, Colorado

Eater: What family memories have informed your perception of chocolate?

Damaris Ronkanen: My abuelita would always have fresh tortillas and atole in the morning. She would get up early and take her nixtamal [cooked corn] to the molino, where they would grind the corn into fresh masa. When she came back she would make tortillas by hand and use a little bit of the masa to make a fresh batch of atole. Whenever I was there she always made sure to make champurrado (a chocolate atole) since she knew it was my favorite. She would toast cacao beans on her comal and grind them by hand using her metate. She would then blend the chocolate into the steaming hot atole and use her molinillo to whisk it until it was super frothy. The process was mesmerizing.

Juan Fuentes, courtesy Ronkanen

Damaris Ronkanen

Unfortunately, I could never replicate this to be quite the same when I was back in the U.S. There weren’t molinos to grind your corn, and people didn’t make their own nixtamal, and there definitely weren’t cacao beans freshly toasted and ground by hand.

How has your business model evolved since its inception?

When we started out making chocolate, the big guys of the chocolate-making industry defined what craft chocolate was, so we felt the pressure to make bars in order to succeed. Still, I was pulled by my Mexican roots, and the memories of market visits and fresh champurrado with my grandmother.

There was a huge difference between my grandmother’s texture and European texture. When we officially started Cultura, I wanted to get back to my heritage, so we introduced drinking chocolate. I knew in order to honor my grandmother, and to move my business forward, I would need to define what I was doing on my own terms and decide what impact my business could have on my community. As successful as the bars were at the wholesale level, they weren’t speaking to my soul.

What is your approach in how you communicate about chocolate in your work?

After experiencing such a pivotal moment in 2018, opening Cultura, connecting with my roots helped define not only what I wanted to create, but how I talk about chocolate too. Our local community in Westwood is composed largely of Mexican immigrants, and we made it part of our mission to create a non-intimidating space where families could feel at home with familiar flavors. They might not immediately connect with the single-origin bars we offer, but they definitely get excited about the drinking chocolate, which opens a door to educate about origin, terroir, and processing.

Even in the way we designed our logo, and chose a mural for the outside of our building, people in the community feel welcome. It becomes a true form of empowerment for our community when they take part in hands-on classes, teaching everything from where the cacao originates to making beverages to explaining what the molinillos they may have seen around their grandparents’ houses are actually used for.

How have you been able to find success while avoiding the elitist mentality around chocolate making?

We focus on culturally relevant chocolates. I’ve learned to not try and emulate the style of chocolates other companies were making, but instead to make chocolate that our community appreciates, and that highlights my heritage. Without having real experience, these other companies construct their narratives around their sourcing, creating a false reality of how much impact they really have on the groups of people they feature on their social media feeds. These stories are used for marketing and to drive up pricing. There’s a certain elitism in craft-chocolate making that fetishizes authenticity through communication and packaging in order to make their product accessible for white people.

We don’t have the influence and reach of these other companies, but that isn’t the goal either. It has taken a lot of effort for people to understand why we do things the way we do, but I’ve always known there was so much more my business is capable of in terms of making chocolate accessible and engaging our community.

How can we leave the door open to create more diversity in the chocolate making world?

The question we’ve always asked of ourselves is: What impact can our company have? A conversation I would like to see happen is of the limited entrepreneurial spirit and access in America. In Mexico, the opportunity is available to everyone to continue family traditions in business. Here, there is a lot of intimidation and difficulty in making your own path. So in order to positively influence this issue, we exclusively hire women from within the community. We offer classes to youth who otherwise don’t have access to craft chocolate — this is their space too. We are bilingual, so there aren’t any language barriers to learning or curiosity.

Jill Fannon/Eater

Jinji Fraser

Jill Fannon/Eater

The lingering question is: What actionable steps might we take to inspire a new generation of BIPOC chocolate makers, and how can they feel justified in exploring the craft of chocolate making in their own ways without intimidation or judgment?

“BIPOC makers need to organize and create their own BIPOC chocolate makers association, in which we spend time and resources educating, supporting, and uplifting each other, and where many ways of expressing chocolate can coexist,” McNeil-Rueda says. As for me, my earliest experience in chocolate making was at the International Chocolate Show in Paris in 2012. I learned then, and have known through my career, that an impeccable bar is one whose texture is smooth and melt is indiscernible from one’s own body temperature. Perfection and accolades are both sought through thousands of dollars of stainless-steel equipment and, importantly, an agreement and an eidetic memory of European technique.

My most recent experience of chocolate making in Guatemala was categorically different, and wildly more satiating: Indigenous women slow-roasting beans over an open flame, then hulling them using friction and the wind, before using a molcajete to grind the beans into a paste heavy with grit and fragments of all the cacao ever to pass that stone bowl, ready for drinking. In that moment of awed observation, I felt that this technique and experience should be allowed to live in those Highlands, and with their descendants; respected without appropriation, lauded with curiosity and intrigue. I knew it was upon me to discover what methods and practices are innate to me, and then to educate my community on a broader vision of good chocolate.

As it relates to chocolate, one should be able to choose their pleasure. However, this is not a journey that can be void of education. There must be support for the idea that chocolate takes on many different forms, and freedom for each form to exist means respect for all who make it. “Positions of leadership in craft chocolate companies should be held by Black and brown people in order to heal the whitewashing of our cultural roots,” says Ronkanen. Indeed, that would be a collective effort to decolonize chocolate and acknowledge the ancestral pathways critical to making the industry whole.

Jinji Fraser is a Baltimore-based writer and chocolate-maker at Pure Chocolate by Jinji.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3kgZVpA via Blogger https://ift.tt/35plJcn

0 notes

Text

“I am constantly discovering, expanding, finding the cause of my ignorance, in martial arts and in life. In short, to be real.” -Bruce Lee

I’ve always been a Bruce Lee fan.

I’m not sure at what point exactly he made such an impression on me; I only know it was a lasting one.

He didn’t believe in limits, barriers, or conformism; he believed in self mastery, authenticity, and testing the abilities of human potential. He had a higher level of thinking that transferred into every area of life. He created his own style of martial arts that had no style — it was adaptable to anything. His legacy is the kind we all aspire to leave; one of significance, purpose; making an impact in the time we’re here.

I have 2 copies of his book, Jeet Kune Do. He was always thinking, always evolving, always learning. I did ‘Bruce Lee Monday’s’ for awhile as a tribute, but people kept asking if I was taking karate instead of focusing on the wisdom.

I looked up some of his habits and how he spent a typical day. According to his daughter Shannon, Bruce dedicated time for physical, mental and spiritual development in his daily life — creating a day filled with training, learning, teaching, writing, and connecting with people.

In other words, he created a schedule that fit his life priorities, not squeezing his life to fit around someone else’s.

Take his advice: research your own experience. Design the life and style you want to live, then do the work to make it a reality. Don’t pursue things society says you should want; don’t conform to anyone else’s expectations. Understand your own.

Here are a few of my favorite quotes from him, and from those who knew him. I hope they resonate with you as much as they do with me. -J

1. “I have changed from self-image actualization to self actualization…from blindly following propaganda, organized truths, etc, to searching internally for the cause of my ignorance.”

2. “A man is at his worst when he does not understand himself. He will work to accumulate external securities rather than do the inner work that will bring true security and rootedness. So cultivate and school yourself.”

3. “Research your own experience. Absorb what is useful, reject what is useless, add what is essentially your own.”

4. “To see a thing uncolored by one’s own preferences and desires is to see it in its own pristine simplicity.”

5. “We possess a pair of eyes to help us to observe as well as to discover, yet most of us simply do not see in the true sense of the word. However, when it comes to observing faults in others, most of us are quick to react with condemnation. But what about looking inwardly for a change? To personally examine who we really are and what we are, our merits as well as our faults. In short, to see oneself as one is for once and to take responsibility for oneself.”

6. “The conformer seldom learns to depend upon himself for expression; rather he faithfully follows a pattern. As time passes, he will probably learn some dead routines and be good according to his set pattern, but he has not come to understand himself.”

7. “Man, the living creature, the creating individual is always more important than any established style or system.”

8. “As a person matures, he will realize that his skills are not so much tools to conquer others, but tools used to explode his ego and all its follies.”

9. “Although I can tell you what is not freedom, I cannot tell you what it is because that you must discover for yourself.”

10. “…On the sea, I thought about all my past training and got mad at myself and punched at the water. Right then in that moment, a thought suddenly struck me. Wasn’t this water, the very basic stuff, the essence of kung-fu? I struck it just now, but it did not suffer hurt. Again I stabbed it with all my might, yet it was not wounded. I then tried to grasp a handful of it but it was impossible. This water, the softest substance in the world, could fit into any container. Although it seemed weak, it could penetrate the hardest substance in the world. That was it! I wanted to be like the nature of water."

11. “I treasure the memory of past misfortunes. It has added more to my bank of fortitude.”

12. “The meaning of life is that it is to be lived, and it is not to be traded and conceptualized and squeezed into a pattern of systems.

13. “Each man binds himself — the fetters are ignorance, laziness, preoccupation with self and fear. You must liberate yourself.”

14. “Bring the mid into sharp focus and make it alert so that it can immediately intuit truth, which is everywhere. The mind must be emancipated from old habits, prejudices, restrictive thought processes and even ordinary thought itself.”

15. “When you are talking about fighting, with no rules. Well then, baby you’d better train every part of your body.”

16. “There is no mystery about my style. My movements are direct, and non-classical. The extraordinary part of life lies in its simplicity. Every movement of Jeet Kune do is being so of itself. There is nothing artificial about it. I believe that the easy way is the right way.”

17. "A good teacher can never be fixed in a routine. Each moment requires a sensitive mind that is constantly adapting. A teacher must never impose this student to fit his favorite pattern. A good teacher is never a giver of truth; he is a guide, a pointer to the truth that each student must find for himself. I am not teaching you anything. I just help you explore yourself."

18. Master: “What is the highest technique you hope to achieve?

Bruce: “To have no technique.”

a. “Time would just stop when he was around. He was so inspirational and high-spirited. When I was down, Bruce would always lift my spirits and I would feel better. He could be a serious person one moment and a jokester the next.” -Allen Joe

b. “What many do not know is that Bruce was a practical joker. He giggled a lot, he was somebody you went to high school with. On the other hand, he was very philosophical. He compelled you to be in his presence.” -Jerry Poteet, Bruce Lee’s student and friend.

c. “I met Bruce Lee and he picked up my spirits…he had this inner desire to create equality among people and to try to bring out the best in people.” -Taky Kimora

#goalrecon #goals #hardtokill #nevergiveup #barrierbreaker #consistency #lifestyle #Impact #worlddomination #humanspirit #fearless #mindset #life #inspiration #motivation #perspective #gratitude #satoriseeking #meditation #namaste #R8 #justbecause

0 notes

Text

Truce: Chapter 14.1

Hanzo returns home three days after the fight.

The wake is that same evening.

He floats through it, feeling ephemeral and untethered in the hospital issued hover chair. The guests offer their condolences with murmurs that pass through him; not a single word manages to catch inside his ears. His sight is also compromised; unfocused and erratic. His eyes skate around the framed photos of his brother, instead drawn to the movements of hands over the bowl of incense and the slow waft of pale smoke. He realizes he will never get the smell of incense, earthy and morbid, out of his nostrils.

There is no casket. He has attended dozens of funerals, but this one breaks pattern. The body is already cremated. A numb monotone in the back of his mind informs him he has fucked it up; his brother's one and only funeral.

Ando-san pays his respects with his head bowed, as if he had not four days before told Hanzo that Genji needed to die, and two days after that congratulated him on doing the right thing. The elder's mouth had cut a severe crevice in stony features, but his eyebrows were held aloft with something like pride.

An distant part of Hanzo advises he leap from the chair and cut the man's throat open. Ando is old, Hanzo wouldn't need his feet.

A more immediate part reminds he'd be better to turn the blade into his own stomach instead.

The rest of him chants a silent mantra that none-the-less drowns out the priest and his sutra; he's dead because you killed him, he's dead because you killed him, he's dead because you....

Hanzo stays with the ashes all night and does not sleep. He reminds himself that if he was able to carry out the duty of killing his own brother, he is certainly capable of anything else. The night passes without words or tears or much of anything but an empty stare at the carved box bearing his brother's remains. Hanzo wonders how long it will take until he feels as if he inhabits his own body again. How long until he believes that body inhabits a reality where his brother is dead (because I killed him).

In the morning, there is another ceremony. His brother's ashes are buried near their father.

Hanzo records little of it to memory.

The funeral guests are all family, clansmen, some of them men who had despised Genji, others who hadn't even known him. They are here because they support the clan, not because they would miss his brother.

Genji's friends do not attend. Hanzo almost thinks to ask if they had even been invited, but finds he doesn't care about the answer.

When the guests leave, a young woman with eyelids painted bright green darts between the bodies filing out the open gate. Hanzo does not recognize her specifically, but identifies her as the right age and disposition to be among his brother's social circle.

She has a wide look in her eyes. Frightened; not of standing in the middle of a loose gathering of yakuza, but of the dour funeral wear surrounding her. "Where is he?" She asks no one, until the moment her gaze finds Hanzo. He watches her identify him, then take in the chair and the blanket hiding his injured legs. Her stare lingers where his feet do not dent the blanket.

"What happened?" This time there is a cold certainty in her voice, clear as the peal of a bell. She already knows the answer.

Hanzo says nothing.

But that isn't enough. And the moment she springs for him is the moment Watanabe-kun steps from between two guests, grabbing the girl's wrists and twisting them behind her in a relentless grip. The girl grimaces, growls, and then decides Watanabe is not who she wants, her attention snaps back to Hanzo. "Tell me!"

"He's dead." Because I killed him.

His intention was to only give her half the truth, but his mouth rebels. Voicelessly, his lips complete the manta, confessing to this stranger. He watches her decipher the message and feels nothing.

To some degree or another, all of Genji's friends have a confrontational spirit. No respectable citizen would consort with someone of Genji's demeanor, appearance, tastes, and connections. He expects her to be furious. Maybe threaten to kill him.

Instead he sees the anger and fear drop away from her features, replaced with only a knit confusion. A look of such disoriented loss that Hanzo almost has the impulse to offer her a hand.

"What?" She shakes her head, Watanabe-kun continues to hold her wrists but it's unnecessary. The girl looks as if she has been spun dizzy. Like if Watanabe released her, she might sit down where she stands. "Why? What... happened? Aren't you his brother?"

"Enough," Watanabe jerks her hard by the wrists, no nonsense as she escorts her prisoner to the gate to be tossed out. The girl hardly even seems to notice, dragged through the gathering of family that watched but kept a distance. Her vision jerks to each of them in turn, stuttering between imposing faces and mourning garb. "Don't you call yourself family?? What the fuck is wrong with you?!"

No one answers her.

Watanabe-kun drags her out of view of the gate.

When the guests have left, Hanzo steers his chair through the halls until he reaches Genji's room.

It's different, Hanzo realizes, as he takes in the decorations with dull observations. It is always different, lately. Genji redecorated or rearranged his room at least once a year. Posters went up and down, Japanese sensibility was replaced with a western frivolity, then back to his roots again. Merchandise from his favorite shows would go on display, then be knocked into trashcans or drawers. Currently he has a large mattress on a high pedestal with dark blue sheets. Armor he hates to wear still stands in proud display on a mannequin in the corner. A wall has been decorated with all manner of weapons, as if they are for aesthetic purposes alone. Hanzo supposes Genji would rather use them to impress lovers than take lives.

Not that it matters now. Not when he's dead because you killed him.

There is a long cabinet in the corner, expensive bronze wood engraved with dark, shimmering dragons. It had belonged to their father. Hanzo remembers catching Genji sliding it through the halls from his room; one of the few demonstrations his brother made of trying to keep a piece of the man who had raised them.

They hadn't talked much, in the months since his death. Hanzo had no doubts that the spike of increased distance was related to his brother's own fraught feelings about their father and the Shimada legacy left to them. But Hanzo'd had little time to mourn, and no option to run away from his responsibilities.

He opens the cabinet, revealing a narrow skyline made up of colorful bottles; tall or fat, square or round. He picks out a long red one, rice wine produced right here in Hanamura from a small distillery, and pours himself a glass.

Genji's room looks out over a square garden. It's late in the season and the blossoms are sparse, but green and burgundy leaves have unfurled into a backdrop for the remaining speckle of pale flowers, all of which rests on the slate gray gravel that makes up the majority of the garden. Every pebble polished down to river stone softness so they could walk on it barefoot with no discomfort.

He supposes neither of them will ever enjoy that again.

Hanzo's bedroom is on the opposite end of the same garden, though it has been years since they would meet in the middle. To spar, to discuss their unshared interests, to bicker, to drink.

"It's my birthday, brother, so you have to do whatever I say."

"I've never once agreed to that," Hanzo sighs, begrudgingly aware that within reason, he would anyway. Genji must have deduced the same.

"C'mon, I'm not asking for a lot, just try a little spine with me."

Hanzo turns a sharp gaze on Genji, "You must be joking."

"No?"

Hanzo, twenty, on break during Golden Week meaning he had only half as many responsibilities as usual, reaches out to tweak his younger brother's ear. "Stop using the product! You're going to get addicted."

Genji sidles closer to Hanzo at the tug with the same fluidity he uses to diffuse punch or a throw. And then rolls his eyes. "So it's fine if it's other people, just not me?"

"Yes."

"Heh," there's a wistful twist to Genji's mouth. "Sure. Look, we're not getting addicted, I just want to try it once."