#this is particularly making me think of the Strawberry Fields Forever scene

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My heart literally just skipped a beat as soon as I thought of the lyrics for Komm Sußer Tod in End of Evangelion

Shaking crying throwing up I think I have a small idea now

If the crossover works thematically then YEAH it’s fine I can do it. Songfic. For sure I mean HOW ELSE

Eva quotes. Thematically relevant parallels. If that is good enough then, yeah. I guess. But if it’s a LITERAL crossover then. Shit I got nothing bro

#nope I am not going to sleep now#i gotta Figure This Out#if it means I get no sleep then so be it#THIS IS THE MOMENT WHEN SHINJI ACCEPTS TO UNITE WITH HUMANITY AND ACCEPT HIMSELF#AND YET HE’S STILL FACED WITH THE GHOST OF KAWORU NOW AS AN ENEMY#NOT AS A FRIEND AND POSSIBLY A LOVER ANYMORE#I AM TRYING NOT TO PHYSICALLY SCREAM#HIDEAKI ANNO PETER JACKSON IT’S YOUR FAULT#also bc I can’t write for shit#but who else is gonna do it#I’d love for someone to tell me ‘hold on I’m on it’ and stop me#please stop me please#this is particularly making me think of the Strawberry Fields Forever scene#I NEED TO STOP#mixing up Komm Sußer Tod and take a sad song and make it better#Jesus Christ

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beltane Films

It’s a bit shit we can’t go frolic with the fae in the fields this Beltane and your one allocated government walk a day isn’t exactly the same as sitting, saturated by the sun all day on the Heath getting melted and eating strawberries. So I’ve made a list of my favourite films to help magically transform our inside lives into one that suitably reflects the mood of a fertility and love festival. Freya forbid it rains on friday but if it does dampen our witchy festivities at least we can get cosy and escape into nature through our imagination.

1. Practical Magic (1998); 90s dreamy scene scape, botanical witches, cute vintage dresses, midnight margaritas, chocolate cake for breakfast and a true love story, is there anything more worth watching on the Witches valentines? It ends on Samhain it’s a perfect witchy Beltane extravaganza- I mean that greenhouse tho

https://ww2.123movie.cc/movies/practical-magic/

2. The Love Witch (2016)

Beltane is about LOVE and WITCHES duh. There’s a Beltane ritual, the visuals are everything I want and need, it’s a smart, aesthetically appealing deep dive into the subversion of the male gaze. Anna Biller made all the costumes (!!) herself, she wrote, directed, produced it and personally I believe it to be one of the best horror flicks to have emerged in the past decade. Reminisce on all those terrible, tragic and non-consentual love spells I know you cast long long ago and indulge in some glamourous murder.

https://ww7.123moviesfree.sc/mov/the-love-witch-2016/

3. Tuck Everlasting (2002)

A film about a family that lives forever after drinking some magical spring water in the woods? Very Beltane. It has that 00s dreamy sheen, edwardian costume, a love story, a coming of age story and it’s all set in New England right at the end of the turn of the last century. In the original story our protagonist Winnie Foster was 10 years old and it was originally written as a children’s book which honestly is a bit creepy. Nevertheless, it’s a beautiful story about finding yourself, acknowledging the wheel of time and appreciating life death life cycles. Also whatshername from Gilmore Girls is in it. Cute. Perfect for a spring festival. There’s also a musical that flopped massively but some of the songs are worth a lil listen.

https://www.putlockers.cr/movie/tuck-everlasting-4736.html

3. FairyTale: A True Story (1997)

It’s Beltane we must have fairies! I was obsessed with this film as a child, particularly with the teeny tiny furniture they make for the fairy dolls house. I also spent a lot of time trying to untie myself from ropes like Houdini.This is the fictional retelling of the true story of the Cottingley girls who were caught up in the popular mysticism craze in the early 1900s and accidentally became celebrities after photographing the ‘fairies’ at the bottom of the garden. The story was a national sensation but after further investigation it was discovered that the photos had in fact been faked. No shit. The truly shocking thing is that the Cottingley girls seem to have escaped unharmed by the fae. It’s a great heartwarming film and features an interesting depiction of the British obsession with fairies and mysticism following rapid industrialisation. It also celebrates the beauty of Yorkshire and the British countryside in a very understated manner and honestly it might have been this film that launched my deep desire to run away into some woods and never look back.

https://ww2.123movie.cc/movies/fairytale-a-true-story

4. The Last Leprechaun (1998)

Ok this one is a bit mad. Another childhood favourite of mine, this film was given to me on a tape by my Scorpio Sun Gemini Moon Scottish grandad and within that context this film makes a lot of sense to me. It’s set in Ireland, this American family move into this huge house and discover the land is populated by the fae, quel surprise. There are banshees, there are fairies in a mine, there’s leprechauns looking for gold, it’s batshit and nowhere near as visually appealing as the films listed above but it’s a really fun watch. A good reminder at this time of year- don’t mess with the little people.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFd63gzYamw

5. Globe Theatre productions/ Online Theatre

This time of year would normally herald the start of outdoor concerts, festivals, garden parties and theatre out in the open air. Nothing compares to the magic of experiencing theatre outdoors, combining my two favourite lasting loves, theatre and nature in one. Naturally I’m devastated to be missing an entire season of outdoor theatre but thankfully the Globe has made loads of productions available online for FREE. Unfortunately, one of my favourite plays to watch at this time of year, As You Like It, is not part of the Globe’s free offerings https://globeplayer.tv/videos/as-you-like-it but if you’re looking for love and romance set in a forest with a good smattering of witty repartee and cross dressing look no further. Shakespeare’s birth and death day just passed us by (23rd) and if you haven’t yet celebrated this Taurean by indulging in a bit o cultchah I’m gently suggesting that you’d enjoy it. Equally, I’d recommend Emma Rice’s production of Midsummer Night’s Dream from the Globe, it’s literally the best production I’ve ever seen and at this point I’ve likely seen over 20 different productions of Dream so take me up on it. The cabaret artist Meow Meow plays Titania and I can’t think of anyone playing the Fairy Queen better.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p08b015k/culture-in-quarantine-shakespeare-a-midsummer-nights-dream

FREE ON BBC IPLAYER!!!

The customs in the play are somewhat a mixture of Beltane and Litha practices so tbh it’s good sabbat to sabbat. I guess you could also watch the Tempest if you really wanted but I kind of hate it ngl.

Angela Carter’s ‘Wise Children’, dir. Emma Rice

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p0892kf6/wise-children

Free on BBC iPlayer, I was lucky enough to see this show in person while it was at the Old Vic and yes, I’m a massive Emma Rice fan and if you watch it you’ll understand why. The show has nothing to do with the fae or Beltane but it is from modern myth maker Angela Carter (who wrote the Bloody Chamber) so there’s lots of folklore and mythical elements woven in. It’s just a bloody good time, it’s colourful, queer and musical whilst unconventionally exploring family trauma.

A Winter’s Tale, Royal Ballet

The Royal Opera House/Royal Ballet is screening their production of A Winter’s Tale on Friday at 7pm, it’s very magical, it’ll be available for a week, wahey

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n-byR-6p-qA

6. Anne with an E: Season 3, Episode 5, Netflix

https://www.netflix.com/watch/81025449?trackId=13752289&tctx=0%2C4%2Cf5cee1ae-463c-468c-90ac-6ccae34b01ad-31458487%2C%2C

I wasn’t too keen on Anne of Green Gables before Netflix made it dark and hashtag real. I particularly love this episode which features a Beltane ritual at the end, I know I wish I could meet you all round a bonfire waving ribbon wands in my nightgown. The last season in particular really solidifies Anne as symbolic of wild woman in tune with nature and the rhythms of her own soul and I could probably deep dive into this ad infinitum.

Skip to 40:14 minutes if you wish to only see the ritual.

7. Honorable mentions:

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) because fairies

https://www4.123movies.gr/movie/pans-labyrinth-2006/

Midsommar (2019) because although I know this film is really more for Litha, they have a Maypole so I think we can make it work

Far from the Madding Crowd ( 2015) Carey mulligan and countryside and terrible life decisions, the soundtrack is also very soothing on its own. You can watch it free (legally, shocker) on the BBC website.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcfilms/film/far_from_the_madding_crowd

Tess of the D’urbervilles (2008) the TV series!! with Gemma Arteton (?) as Tess; pastoral life, nature pagan goddess allusions and a finale at Stonehenge very Beltane. Once you get past all the religion stuff Hardy’s aight.

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2739yo

Happy Beltane Witches!!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

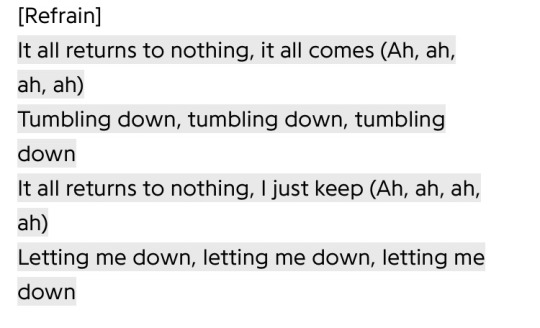

As promised, here is the Nygmobblepot fanmix I mostly put together this fall. (See the end of the post for links.) I’ve come across a few very nice fanmixes for them, but not a lot of the ones I found had rock music, and since Nygmobblepot is such a hard rock sort of couple I felt like the need to make a more rock-heavy playlist for them. (Plus, it’s just the sort of music I listen to most often, and so these are the songs that come to mind for me.)

I focused mainly on their season 3 arc, especially the angst. I tried to put the songs in a sort of narrative order, so it starts out with songs that are a bit more focused on their love; Lydia is meant as the turning point where the Isabella murder happens and things start heading south, and the songs thereafter are more focused on their darker dynamic in the latter part of season 3 (though they’re all on the dark side; this is meant to be an angsty playlist). Not every song precisely follows this arc; Bloodfeather, for example, leans towards that darker side of things, but it also fits them so well that I wanted to open the playlist with it. I think it works as echoing the foreshadowing of their relationship in season 2 as well.

1. *Bloodfeather by Highly Suspect: “In the name of love, I’ll follow you. And if my body’s dead and cold I died for you; in the name of love I’d kill for you.” “You’re fatal but I love who you are. Be my death or my forever; you’re my little bloodfeather.” (Our Penguin does tend to get his feathers bloodied... Granted, that’s not what a bloodfeather is, but the image does fit.)

2. Song 3 by Stone Sour: “If you take a step towards me, you will take my breath away, so I’ll keep you close and keep my secrets safe. No one else has ever loved me, no one else has ever tried, never understood how much I could take. There’s a darkness down inside me that I know we’ll both enjoy. Did I save you? 'Cause I know you saved me too.”

3. I’m Not Alright by Shinedown: “All messed up and slightly twisted. Am I sick or am I gifted? Maybe it’s me, I'm just crazy; maybe I like that I’m not alright.” (Honestly this one fits Gotham in general--”all dressed up in a white straight jacket” is actually a very Jerome line--but I figured I probably wasn’t going to get around to making a general Gotham playlist and it suits Nygmobblepot’s mutual madness, I think.)

4. Little Monster by Royal Blood: “Hey little monster, where’ve you been hiding, and can I come this time? Heartache to heartache, I’m your wolf, I’m your man. I say run little monster, before you learn who I am.”

5. Glycerine by Bush: “We live in a wheel where everyone steals, but when we rise it's like strawberry fields. I treated you bad; you bruised my face. Couldn't love you more, you’ve got a beautiful taste. It could have been easier on you, I couldn't change though I wanted to. Should’ve been easier by three; our old friend fear and you and me.”

6. Possum Kingdom by Toadies: “I’m not gonna lie. I'll not be a gentleman. Behind the boathouse I'll show you my dark secret... Do you wanna die?” (I’ve heard and thought of many interpretations for this strange, dark love song, but somehow or another, they all seem to fit Nygmobblepot.)

7. *Lydia by Highly Suspect: “I am the hungry shark, fast and merciless. But the only girl that could talk to him just couldn't swim, tell me what's worse than this. Your eyes alive in pain, black tears don't hide in rain, and I tied you to the tracks; when I turned around, I heard the sound, I hit the ground, I know there's no turning back.” (It’s particularly interesting how Oswald circuitously killed Isabella with railroad tracks, echoing the old mustache-twirling villain trope of tying the damsel to the train tracks that this song also references. Although if Isabella had had the presence of mind to realize that even if her breaks were out, her steering wheel was still working, she probably wouldn’t be dead, but that’s a rant for another day.)

8. I Only Lie When I Love You by Royal Blood: (the title says most of it but) “Go ahead, pull the plug; broken finger, sticky trigger, now I can't get it off my chest... you know I’m up to something.”

9. Roll Me Under by Stone Temple Pilots: “Do you believe in something beautiful between chaos and the light?” (harks back to their earlier romance, but) “Roll me under, I'll pull the trigger for you. Do with me what you will. Hold me under, the water running over...” (harks forward to the first dock scene. Really I could’ve put this later in the mix but I also put it here to keep the hard/soft balance of the songs cycling back and forth just for auditory balance. Narratively it probably should’ve been #11.)

10. *House on Fire by Rise Against: “I’m in over my head and she's a high tide that keeps pushing me away. I thought we would build this together, but everything I touch just seems to break. Am I your sail or your anchor? Am I the calm or the hurricane?” “Till then I’ll hold you like a hand grenade. You touch me like a razor blade. I wish there was some other way, but no. Like a house on fire, we’re up in flames. I’ll burn here if that’s what it takes.”

11. Disarm by the Smashing Pumpkins: “Disarm you with a smile. Cut you like you want me to. The killer in me is the killer in you, my love. I used to be a little boy; so old in my shoes.”

12. Say You’ll Haunt Me by Stone Sour: “I will give you everything to... say you'll never die, you'll always haunt me. I want to know I belong to you; say you'll haunt me. Little soft pulses in my dead, little souvenirs of secrets shared, little off guard and unprepared.” (Basically Ed to Oswald in s3e15.)

13. Let it Die by the Foo Fighters: “Did you ever think of me? You’re so considerate. Hearts gone cold and your hands were tied; why’d you have to go and let it die?” (To clarify, I don’t by any means want to suggest that the ship is dead by ending my playlist on this note; I still have hope for Nygmobblepot in season 5, and if nothing else I think season 4 very clearly showed that the ship didn’t die for good in season 3. I just love how powerful and raw Dave Grohl’s voice is at the end of this song and I wanted to let it linger, to let that sound be the note this playlist ended on. Like I said, it’s an angsty playlist.)

Here are links to the playlists. I made two because the songs I’ve marked with an asterisk all have the f-word in them; in the case of House on Fire, it’s only once, but it’s several times in Bloodfeather. If you’re alright with that, here is the playlist with the original, uncensored songs.

If you would prefer clean versions, here is a version of the same playlist with clean versions of those three songs.

Fun fact: there was no clean version of House on Fire by Rise against on youtube, so I made my own using a handy editing trick. I probably could also have made better versions of the clean edits of the two Highly Suspect songs (no offence to the original editors but they’re not perfectly smooth and Bloodfeather has a weird gap at the end) but I decided it wasn’t worth the effort. If you would like me to make different edits of those, though, let me know and I’d consider it. I should perhaps also mention that Possum Kingdom does use the name of Jesus, but as long as you read the singer’s request as sincere it’s not taking it in vain. But, I do admit that it could be interpreted that way, for the sake of fair warning.

So, I hope you enjoy this dark, angsty, rocking season 3 Nygmobblepot playlist! Here’s to hopefully some great Nygmobblepot scenes in season 5.

#Nygmobblepot#Nygmobblepot fanmix#Nygmobblepot playlist#Gotham#angst#gotham season 3#gotham season 3 spoilers#rock music#dark romance#Oswald Cobblepot#Edward Nygma#dark lyric warning#violent lyric warning?#I don't always know what warnings to put on things but I try#I ramble but in service of explaining my fanmix this time#actually several of these songs I originally thought of with other ships#Little Monster and Glycerine were both Rumbelle songs for me#and Song 3 was Percleth even though I'm more or less the only person on the internet who ships Percleth#just some fun facts#I also learned from this the importance of saving drafts#because if you leave a half-finished post open for too long sometimes the page refreshes itself and you lose the whole thing#Nygmobblepot rocks

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was never obsessed with the Beatles to the degree many of my peers were, but when I saw this Instagram post this morning, I had to do a little digging. So here you go: The Beatles’ 1967 hit “Strawberry Fields Forever” has long been considered one of the greatest pop songs ever recorded. Released in February of that year as a double A side single along with Penny Lane, the song peaked at number eight on the US Billboard charts (The Turtles’ “Happy Together” was number one that week). In 2011, Rolling Stone named it the band’s third greatest song and the 76th greatest song ever. Written by John Lennon, it’s a true masterpiece, but what it isn’t is a song about fields full of strawberries. Reading the lyrics, it’s clear that the song isn’t as happy-go-lucky as the melody might suggest. The song is more about Lennon’s insecurities and his tough childhood. The title of the song refers to the Salvation Army-ran girl’s orphanage – dreamily called “Strawberry Field” – that Lennon lived near growing up in Liverpool. Here’s the real story behind the song “Strawberry Fields Forever.” The Beatles were going through a rough patch when they all splintered off in the summer of 1966, immediately following what would be their last US live performance at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. The Fab Four would eventually reunite for six more albums (and one legendary, unannounced rooftop live performance), but that wasn’t known in the summer of ‘66. For his part, Lennon made his way to Almería, Spain to star in the black comedy How I Won the War. With long waits between shooting scenes, Lennon had plenty of time to write. In six weeks, he had a working version of the song that would come to define the Beatles’ second act. John Lennon’s childhood wasn’t particularly happy. When he was a baby, his banjo-playing father Alf was rarely home and often away at sea as a merchant. Tired of his travels, John’s mother Julia fell in love with another man and got pregnant with John’s half-sister. This caused a tremendous rift in the Lennon family with Julia’s sister Mimi calling social services twice on her own sister for raising John in, what she called, an unfit home. Eventually, social services handed John’s care over to Aunt Mimi and he spent a large portion of his childhood at his Aunt’s suburban Liverpool home in a town called Woolton – the house is now part of UK’s National Trust as a museum. John’s relationships with his parents after that were tragic. He wouldn’t see his father again for over two decades. John’s mother was hit and killed by a speeding car while crossing a road when John was only 17. According to Cynthia Lennon, John’s first wife, while Aunt Mimi did care for John, “she was not a woman for cuddles and praise.” Ruling with an iron fist, John was expected to be obedient, well-behaved and groomed. Later, biographers would write that he had a hard time making friends. It’s little wonder that young John Lennon had a rebellious streak and would often go in secret to play in the gardens of his next door neighbor – the girl’s orphanage Strawberry Field. The history of Strawberry Field dates back to 1870, when the property was owned by a wealthy English ship owner named George Warren. On the site, he built a giant gothic mansion that was in line with England’s Victorian-era, complete with a iron wrought gate, gardens and flowers. In 1927, another wealthy ship magnate named Alexander C. Mitchell purchased the mansion and property. Seven years later, Mitchell’s widow sold it to the Salvation Army. On July 7, 1936, the home was opened as a orphanage for up to forty girls. Two decades later, boys would be allowed in, but throughout most of John’s childhood, Strawberry Field was an all-girls’ orphanage. Years later, interviews would reveal the influence this foreboding, mysterious place had on Lennon’s writing. In a 1968 Rolling Stone interview, Lennon said that he was trying to write about Liverpool and had “visions of Strawberry Fields… Because Strawberry Fields is just anywhere you want to go.” (Note that the song title is “Strawberry Fields,” but the actual place is called “Strawberry Field.” Lennon would later admit that this was a stylistic choice- “Fields” simply sounded better than “Field.”) Lennon also often alluded to how Strawberry Field was representative of his childhood, on the outside foreboding but once he climbed over that wall, full of wildflowers and secretive gardens. It’s also thought that he greatly identified with the orphans who lived there, considering that he felt abandoned by his parents. In 1980, he explained his childhood thinking, “There was something wrong with me, I thought, because I seemed to see things other people didn’t see.” When John Lennon brought the song back to the band in November of 1966, it was met with awe. Engineer Geoff Emerick recalled to Rolling Stone that fateful moment, “There was a moment of stunned silence, broken by Paul, who in a quiet, respectful tone said simply, ‘That is absolutely brilliant.’” Over about a month, the band tinkered and recorded the song. It is widely thought of as the most complicated recording the Beatles ever did. When it was released in February of 1967, it was exactly what McCartney said when he first heard the song John Lennon named after a Liverpool girl’s orphanage – brilliant. Today, Strawberry Field is in a state of disrepair despite continuing to be a tourist attraction for Beatle fanatics. In 2005, after nearly 70 years as an orphanage, it closed down and all the remaining children were transferred to foster families. While many of the original buildings and structures were torn down in the 1970s, a few still remained including the iconic red Victorian-era Strawberry Field gates – until 2001. The gates, which dated back to Warren, were put into storage and replaced with replicas, leaving many fans (and tour guides, who rely on Beatle-related income) upset. Plans were announced in 2014 to turn the site into “a training centre for people with learning difficulties” along with a museum and artifacts dedicated to the influence this place had on the Beatles and John Lennon. However, as of this writing, Strawberry Field remains abandoned and mostly decrepit. Sources: Instagram, biography.com, and todayifoundout.com Such a sad, sad story: born during a German Air Raid during WWII, dysfunctional childhood, mother ran over and killed in the street, murdered by an obsessed fan.😢

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’d I miss?

Tim O'Reilly reflects on the stories from 2017 that played out after he finished writing his new book.

There's a scene in Lin-Manuel Miranda's Hamilton in which Thomas Jefferson, who has been away as ambassador to France after the American Revolution, comes home and sings, "What'd I miss?"

We all have "What'd I miss?" moments, and authors of books most of all. Unlike the real-time publishing platforms of the web, where the act of writing and the act of publishing are nearly contemporaneous, months or even years can pass between the time a book is written and the time it is published. Stuff happens in the world, you keep learning, and you keep thinking about what you've written, what was wrong, and what was left out.

Because I finished writing my new book, WTF? What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us, in February of 2017, my reflections on what I missed and what stories continued to develop as I predicted form a nice framework for thinking about the events of the year.

Our first cyberwar

"We just fought our first cyberwar. And we lost," I wrote in the book, quoting an anonymous US government official to whom I'd spoken in the waning months of the Obama administration. I should have given that notion far more than a passing mention.

In the year since, the scope of that cyberwar has become apparent, as has how all of the imagined scenarios we used to prepare turned out to mislead us. Cyberwar, we thought, would involve hacking into systems, denial-of-service attacks, manipulating data, or perhaps taking down the power grid, telecommunications, or banking systems. We missed that it would be a war directly targeting human minds. It is we, not our machines, that were hacked. The machines were simply the vector by which it was done. (The Guardian gave an excellent account of the evolution of Russian cyberwar strategy, as demonstrated against Estonia, Ukraine, and the US.)

Social media algorithms were not modified by Russian hackers. Instead, the Russian hackers created bots that masqueraded as humans and then left it to us to share the false and hyperpartisan stories they had planted. The algorithms did exactly what their creators had told them to do: show us more of what we liked, shared, and commented on.

In my book, I compare the current state of algorithmic big data systems and AI to the djinni (genies) of Arabian mythology, to whom their owners so often give a poorly framed wish that goes badly awry. In my talks since, I've also used the homelier image of Mickey Mouse, the sorcerer's apprentice of Walt Disney's Fantasia, who uses his master's spell book to compel a broomstick to help him with his chore fetching buckets of water. But the broomsticks multiply. One becomes two, two become four, four become eight, eight sixteen, and soon Mickey is frantically turning the pages of his master's book to find the spell to undo what he has so unwisely wished for. That image perfectly encapsulates the state of those who are now trying to come to grips with the monsters that social media has unleashed.

This image also perfectly captures what we should be afraid of about AI—not that it will get a mind of its own, but that it won't. Its relentless pursuit of our ill-considered wishes, whose consequences we don't understand, is what we must fear.

We must also consider the abuse of AI by those in power. I didn't spend enough time thinking and writing about this.

Zeynep Tufekci, a professor at the University of North Carolina and author of Twitter and Tear Gas, perfectly summed up the situation in a tweet from September: "Let me say: too many worry about what AI—as if some independent entity—will do to us. Too few people worry what *power* will do *with* AI." That's a quote that would have had pride of place in the book had it not already been in production. (If that quote resonates, watch Zeynep's TED Talk.)

And we also have to think about the fragility of our institutions. After decades of trash-talking government, the media, and expertise itself, they were ripe for a takeover. This is the trenchant insight that Cory Doctorow laid out in a recent Twitter thread.

The runaway objective function

In April of 2017, Elon Musk gave an interview with Vanity Fair in which he used a memorable variation on Nick Bostrom's image of an AI whose optimization function goes awry. Bostrom had used the thought experiment of a self-improving AI whose job was to run a paper-clip factory; Elon instead used a strawberry-picking robot, which allowed him to suggest that the robot aims to get better and better at picking strawberries until it decides that human beings are in the way of "strawberry fields forever."

In the book, I make the case that we don't need to look to a far future of AI to see a runaway objective function. Facebook's newsfeed algorithms fit that description pretty well. They were exquisitely designed to show us more of what we liked, commented on, and shared. Facebook thought that showing us more of what we asked for would bring us closer to our friends. The folks who designed that platform didn't mean to increase hyperpartisanship and filter bubbles; they didn't mean to create an opening for spammers peddling fake news for profit and Russian bots peddling it to influence the US presidential election. But they did.

So too, the economists and business theorists who made the case that "the social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits" and that CEOs should be paid primarily in stock so that their incentives would be allied with the interests of stockholders thought that they would make the economy more prosperous for all. They didn't mean to gut the economy, increase inequality, and create an opioid epidemic. But they did.

We expect the social media platforms to come to grips with the unintended consequences of their algorithms. But we have yet to hold accountable those who manage the master algorithm of our society, which says to optimize shareholder value over all. In my book, I describe today's capital markets as the first rogue AI, hostile to humanity. It's an extravagant claim, and I hope you dig into the book's argument, which shows that it isn't so far-fetched after all.

We need a new theory of platform regulation

In my book, I also wrote that future economic historians will "look back wryly at this period when we worshipped the divine right of capital while looking down on our ancestors who believed in the divine right of kings." As a result of that quote, a reader asked me if I'd ever read Marjorie Kelly's book The Divine Right of Capital. I hadn't. But now I have, and so should you.

Marjorie's book, written in 2001, anticipates mine in many ways. She talks about the way that the maps we use to interpret the world around us can lead us astray (that is the major theme of part one of my book) and focuses in on one particular map: the profit and loss statements used by every company, which show "the bottom line" as the return to capital and human labor merely as a cost that should be minimized or eliminated in order to increase the return to capital. This is a profound insight.

Since reading Marjorie's book, I've been thinking a lot about how we might create alternate financial statements for companies. In particular, I've been thinking about how we might create new accounting statements for platforms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon that show all of the flows of value within their economies. I've been toying with using Sankey diagrams in the same way that Saul Griffith has used them to show the sources and uses of energy in the US economy. How much value flows from users to the platforms, and how much from platforms to the users? How much value is flowing into the companies from customers, and how much from capital markets? How much value is flowing out to customers, and how much to capital markets?

This research is particularly important in an era of platform capitalism, where the platforms are reshaping the wider economy. There are calls for the platforms to be broken up or to be regulated as monopolies. My call is to understand their economics and use them as a laboratory for understanding the balance between large and small businesses in the broader economy. This idea came out in my debate with Reid Hoffman about his idea of "blitzscaling." If the race to scale defines the modern economy, what happens to those who don't win the race? Are they simply out of luck, or do the winners have an obligation to the rest of us to use the platform scale they've won to create a thriving ecosystem for smaller companies?

This is something that we can measure. What is the size of the economy that a platform supports, and is it growing or shrinking? In my book, I describe the pattern that I have observed numerous times, in which technology platforms tend to eat their ecosystem as they grow more dominant. Back in the 1990s, venture capitalists worried that there were no exits; Microsoft was taking most of the value from the PC ecosystem. The same chatter has resurfaced today, where the only exit is to be acquired by one of the big platforms—if they don't decide to kill you first.

Google and others provide economic impact reports that show the benefit they provide to their customers, but they also have to consider the benefit to the entrepreneurial ecosystem that gave them their opportunity. The signs are not good. When I looked at Google's financial statements from 2011 to 2016, I noted that the share of its ad revenue from third-party sites had declined from nearly 30% to about 18%. Amazon deserves similar scrutiny. Fifteen of the top 20 Kindle best sellers were published by Amazon.

There are other ways that these platforms have helped create lots of value for others that they haven't directly captured for themselves (e.g., Google open-sourcing Android and TensorFlow and Amazon's creation of Web Services, which became an enabler for thousands of other companies). Still, how do we balance the accounts of value extracted and value created?

We need a new theory of antitrust and platform regulation that focuses not just on whether competition between giants results in lower prices for consumers but the extent to which the giant platforms compete unfairly with the smaller companies that depend on them.

Augment people, don’t replace them

Enough of the news that expands on the darker themes of my book!

The best news I read in the 10 months since I finished writing the book was the research by Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute that shows that ecommerce is creating more and better jobs than those it is destroying in traditional retail. "To be honest, this was a surprise to me—I did not expect this. I'm just looking at the numbers," Mandel told Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times. Here is Mandel's paper.

This report nicely complemented the news that from 2014 to mid-2016, a period in which Amazon added 45,000 robots to its warehouses, it also added nearly 250,000 human workers. This news supports one of the key contentions of my book: that simply using technology to remove costs—doing the same thing more cheaply—is a dead end. This is the master design pattern for applying technology: Do more. Do things that were previously unimaginable.

Those who talk about AI and robots eliminating human workers are missing the point, and their businesses will suffer for it in the long run. There's plenty of work to be done. What we have to do is to reject the failed economic theories that keep us from doing it.

That's my call to all of you thinking, like me, about what we've learned in the past year, and what we must resolve to do going forward. Give up on fatalism—the idea that technology is going to make our economy and our world a worse place to be, that the future we hand on to our children and grandchildren will be worse than the one we were born into.

Let's get busy making a better world. I am optimistic not because the road ahead is easy but because it is hard. As I wrote in the book, "This is my faith in humanity: that we can rise to great challenges. Moral choice, not intelligence or creativity, is our greatest asset. Things may get much worse before they get better. But we can choose instead to lift each other up, to build an economy where people matter, not just profit. We can dream big dreams and solve big problems. Instead of using technology to replace people, we can use it to augment them so they can do things that were previously impossible."

Let's get to work.

Continue reading What’d I miss?.

from FEED 10 TECHNOLOGY http://ift.tt/2mczJ3n

0 notes

Text

What’d I miss?

What’d I miss?

Tim O'Reilly reflects on the stories from 2017 that played out after he finished writing his new book.

There's a scene in Lin-Manuel Miranda's Hamilton in which Thomas Jefferson, who has been away as ambassador to France after the American Revolution, comes home and sings, "What'd I miss?"

We all have "What'd I miss?" moments, and authors of books most of all. Unlike the real-time publishing platforms of the web, where the act of writing and the act of publishing are nearly contemporaneous, months or even years can pass between the time a book is written and the time it is published. Stuff happens in the world, you keep learning, and you keep thinking about what you've written, what was wrong, and what was left out.

Because I finished writing my new book, WTF? What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us, in February of 2017, my reflections on what I missed and what stories continued to develop as I predicted form a nice framework for thinking about the events of the year.

Our first cyberwar

"We just fought our first cyberwar. And we lost," I wrote in the book, quoting an anonymous US government official to whom I'd spoken in the waning months of the Obama administration. I should have given that notion far more than a passing mention.

In the year since, the scope of that cyberwar has become apparent, as has how all of the imagined scenarios we used to prepare turned out to mislead us. Cyberwar, we thought, would involve hacking into systems, denial-of-service attacks, manipulating data, or perhaps taking down the power grid, telecommunications, or banking systems. We missed that it would be a war directly targeting human minds. It is we, not our machines, that were hacked. The machines were simply the vector by which it was done. (The Guardian gave an excellent account of the evolution of Russian cyberwar strategy, as demonstrated against Estonia, Ukraine, and the US.)

Social media algorithms were not modified by Russian hackers. Instead, the Russian hackers created bots that masqueraded as humans and then left it to us to share the false and hyperpartisan stories they had planted. The algorithms did exactly what their creators had told them to do: show us more of what we liked, shared, and commented on.

In my book, I compare the current state of algorithmic big data systems and AI to the djinni (genies) of Arabian mythology, to whom their owners so often give a poorly framed wish that goes badly awry. In my talks since, I've also used the homelier image of Mickey Mouse, the sorcerer's apprentice of Walt Disney's Fantasia, who uses his master's spell book to compel a broomstick to help him with his chore fetching buckets of water. But the broomsticks multiply. One becomes two, two become four, four become eight, eight sixteen, and soon Mickey is frantically turning the pages of his master's book to find the spell to undo what he has so unwisely wished for. That image perfectly encapsulates the state of those who are now trying to come to grips with the monsters that social media has unleashed.

This image also perfectly captures what we should be afraid of about AI—not that it will get a mind of its own, but that it won't. Its relentless pursuit of our ill-considered wishes, whose consequences we don't understand, is what we must fear.

We must also consider the abuse of AI by those in power. I didn't spend enough time thinking and writing about this.

Zeynep Tufekci, a professor at the University of North Carolina and author of Twitter and Tear Gas, perfectly summed up the situation in a tweet from September: "Let me say: too many worry about what AI—as if some independent entity—will do to us. Too few people worry what *power* will do *with* AI." That's a quote that would have had pride of place in the book had it not already been in production. (If that quote resonates, watch Zeynep's TED Talk.)

And we also have to think about the fragility of our institutions. After decades of trash-talking government, the media, and expertise itself, they were ripe for a takeover. This is the trenchant insight that Cory Doctorow laid out in a recent Twitter thread.

The runaway objective function

In April of 2017, Elon Musk gave an interview with Vanity Fair in which he used a memorable variation on Nick Bostrom's image of an AI whose optimization function goes awry. Bostrom had used the thought experiment of a self-improving AI whose job was to run a paper-clip factory; Elon instead used a strawberry-picking robot, which allowed him to suggest that the robot aims to get better and better at picking strawberries until it decides that human beings are in the way of "strawberry fields forever."

In the book, I make the case that we don't need to look to a far future of AI to see a runaway objective function. Facebook's newsfeed algorithms fit that description pretty well. They were exquisitely designed to show us more of what we liked, commented on, and shared. Facebook thought that showing us more of what we asked for would bring us closer to our friends. The folks who designed that platform didn't mean to increase hyperpartisanship and filter bubbles; they didn't mean to create an opening for spammers peddling fake news for profit and Russian bots peddling it to influence the US presidential election. But they did.

So too, the economists and business theorists who made the case that "the social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits" and that CEOs should be paid primarily in stock so that their incentives would be allied with the interests of stockholders thought that they would make the economy more prosperous for all. They didn't mean to gut the economy, increase inequality, and create an opioid epidemic. But they did.

We expect the social media platforms to come to grips with the unintended consequences of their algorithms. But we have yet to hold accountable those who manage the master algorithm of our society, which says to optimize shareholder value over all. In my book, I describe today's capital markets as the first rogue AI, hostile to humanity. It's an extravagant claim, and I hope you dig into the book's argument, which shows that it isn't so far-fetched after all.

We need a new theory of platform regulation

In my book, I also wrote that future economic historians will "look back wryly at this period when we worshipped the divine right of capital while looking down on our ancestors who believed in the divine right of kings." As a result of that quote, a reader asked me if I'd ever read Marjorie Kelly's book The Divine Right of Capital. I hadn't. But now I have, and so should you.

Marjorie's book, written in 2001, anticipates mine in many ways. She talks about the way that the maps we use to interpret the world around us can lead us astray (that is the major theme of part one of my book) and focuses in on one particular map: the profit and loss statements used by every company, which show "the bottom line" as the return to capital and human labor merely as a cost that should be minimized or eliminated in order to increase the return to capital. This is a profound insight.

Since reading Marjorie's book, I've been thinking a lot about how we might create alternate financial statements for companies. In particular, I've been thinking about how we might create new accounting statements for platforms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon that show all of the flows of value within their economies. I've been toying with using Sankey diagrams in the same way that Saul Griffith has used them to show the sources and uses of energy in the US economy. How much value flows from users to the platforms, and how much from platforms to the users? How much value is flowing into the companies from customers, and how much from capital markets? How much value is flowing out to customers, and how much to capital markets?

This research is particularly important in an era of platform capitalism, where the platforms are reshaping the wider economy. There are calls for the platforms to be broken up or to be regulated as monopolies. My call is to understand their economics and use them as a laboratory for understanding the balance between large and small businesses in the broader economy. This idea came out in my debate with Reid Hoffman about his idea of "blitzscaling." If the race to scale defines the modern economy, what happens to those who don't win the race? Are they simply out of luck, or do the winners have an obligation to the rest of us to use the platform scale they've won to create a thriving ecosystem for smaller companies?

This is something that we can measure. What is the size of the economy that a platform supports, and is it growing or shrinking? In my book, I describe the pattern that I have observed numerous times, in which technology platforms tend to eat their ecosystem as they grow more dominant. Back in the 1990s, venture capitalists worried that there were no exits; Microsoft was taking most of the value from the PC ecosystem. The same chatter has resurfaced today, where the only exit is to be acquired by one of the big platforms—if they don't decide to kill you first.

Google and others provide economic impact reports that show the benefit they provide to their customers, but they also have to consider the benefit to the entrepreneurial ecosystem that gave them their opportunity. The signs are not good. When I looked at Google's financial statements from 2011 to 2016, I noted that the share of its ad revenue from third-party sites had declined from nearly 30% to about 18%. Amazon deserves similar scrutiny. Fifteen of the top 20 Kindle best sellers were published by Amazon.

There are other ways that these platforms have helped create lots of value for others that they haven't directly captured for themselves (e.g., Google open-sourcing Android and TensorFlow and Amazon's creation of Web Services, which became an enabler for thousands of other companies). Still, how do we balance the accounts of value extracted and value created?

We need a new theory of antitrust and platform regulation that focuses not just on whether competition between giants results in lower prices for consumers but the extent to which the giant platforms compete unfairly with the smaller companies that depend on them.

Augment people, don’t replace them

Enough of the news that expands on the darker themes of my book!

The best news I read in the 10 months since I finished writing the book was the research by Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute that shows that ecommerce is creating more and better jobs than those it is destroying in traditional retail. "To be honest, this was a surprise to me—I did not expect this. I'm just looking at the numbers," Mandel told Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times. Here is Mandel's paper.

This report nicely complemented the news that from 2014 to mid-2016, a period in which Amazon added 45,000 robots to its warehouses, it also added nearly 250,000 human workers. This news supports one of the key contentions of my book: that simply using technology to remove costs—doing the same thing more cheaply—is a dead end. This is the master design pattern for applying technology: Do more. Do things that were previously unimaginable.

Those who talk about AI and robots eliminating human workers are missing the point, and their businesses will suffer for it in the long run. There's plenty of work to be done. What we have to do is to reject the failed economic theories that keep us from doing it.

That's my call to all of you thinking, like me, about what we've learned in the past year, and what we must resolve to do going forward. Give up on fatalism—the idea that technology is going to make our economy and our world a worse place to be, that the future we hand on to our children and grandchildren will be worse than the one we were born into.

Let's get busy making a better world. I am optimistic not because the road ahead is easy but because it is hard. As I wrote in the book, "This is my faith in humanity: that we can rise to great challenges. Moral choice, not intelligence or creativity, is our greatest asset. Things may get much worse before they get better. But we can choose instead to lift each other up, to build an economy where people matter, not just profit. We can dream big dreams and solve big problems. Instead of using technology to replace people, we can use it to augment them so they can do things that were previously impossible."

Let's get to work.

Continue reading What’d I miss?.

http://ift.tt/2mczJ3n

0 notes

Text

What’d I miss?

What’d I miss?

Tim O'Reilly reflects on the stories from 2017 that played out after he finished writing his new book.

There's a scene in Lin-Manuel Miranda's Hamilton in which Thomas Jefferson, who has been away as ambassador to France after the American Revolution, comes home and sings, "What'd I miss?"

We all have "What'd I miss?" moments, and authors of books most of all. Unlike the real-time publishing platforms of the web, where the act of writing and the act of publishing are nearly contemporaneous, months or even years can pass between the time a book is written and the time it is published. Stuff happens in the world, you keep learning, and you keep thinking about what you've written, what was wrong, and what was left out.

Because I finished writing my new book, WTF? What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us, in February of 2017, my reflections on what I missed and what stories continued to develop as I predicted form a nice framework for thinking about the events of the year.

Our first cyberwar

"We just fought our first cyberwar. And we lost," I wrote in the book, quoting an anonymous US government official to whom I'd spoken in the waning months of the Obama administration. I should have given that notion far more than a passing mention.

In the year since, the scope of that cyberwar has become apparent, as has how all of the imagined scenarios we used to prepare turned out to mislead us. Cyberwar, we thought, would involve hacking into systems, denial-of-service attacks, manipulating data, or perhaps taking down the power grid, telecommunications, or banking systems. We missed that it would be a war directly targeting human minds. It is we, not our machines, that were hacked. The machines were simply the vector by which it was done. (The Guardian gave an excellent account of the evolution of Russian cyberwar strategy, as demonstrated against Estonia, Ukraine, and the US.)

Social media algorithms were not modified by Russian hackers. Instead, the Russian hackers created bots that masqueraded as humans and then left it to us to share the false and hyperpartisan stories they had planted. The algorithms did exactly what their creators had told them to do: show us more of what we liked, shared, and commented on.

In my book, I compare the current state of algorithmic big data systems and AI to the djinni (genies) of Arabian mythology, to whom their owners so often give a poorly framed wish that goes badly awry. In my talks since, I've also used the homelier image of Mickey Mouse, the sorcerer's apprentice of Walt Disney's Fantasia, who uses his master's spell book to compel a broomstick to help him with his chore fetching buckets of water. But the broomsticks multiply. One becomes two, two become four, four become eight, eight sixteen, and soon Mickey is frantically turning the pages of his master's book to find the spell to undo what he has so unwisely wished for. That image perfectly encapsulates the state of those who are now trying to come to grips with the monsters that social media has unleashed.

This image also perfectly captures what we should be afraid of about AI—not that it will get a mind of its own, but that it won't. Its relentless pursuit of our ill-considered wishes, whose consequences we don't understand, is what we must fear.

We must also consider the abuse of AI by those in power. I didn't spend enough time thinking and writing about this.

Zeynep Tufekci, a professor at the University of North Carolina and author of Twitter and Tear Gas, perfectly summed up the situation in a tweet from September: "Let me say: too many worry about what AI—as if some independent entity—will do to us. Too few people worry what *power* will do *with* AI." That's a quote that would have had pride of place in the book had it not already been in production. (If that quote resonates, watch Zeynep's TED Talk.)

And we also have to think about the fragility of our institutions. After decades of trash-talking government, the media, and expertise itself, they were ripe for a takeover. This is the trenchant insight that Cory Doctorow laid out in a recent Twitter thread.

The runaway objective function

In April of 2017, Elon Musk gave an interview with Vanity Fair in which he used a memorable variation on Nick Bostrom's image of an AI whose optimization function goes awry. Bostrom had used the thought experiment of a self-improving AI whose job was to run a paper-clip factory; Elon instead used a strawberry-picking robot, which allowed him to suggest that the robot aims to get better and better at picking strawberries until it decides that human beings are in the way of "strawberry fields forever."

In the book, I make the case that we don't need to look to a far future of AI to see a runaway objective function. Facebook's newsfeed algorithms fit that description pretty well. They were exquisitely designed to show us more of what we liked, commented on, and shared. Facebook thought that showing us more of what we asked for would bring us closer to our friends. The folks who designed that platform didn't mean to increase hyperpartisanship and filter bubbles; they didn't mean to create an opening for spammers peddling fake news for profit and Russian bots peddling it to influence the US presidential election. But they did.

So too, the economists and business theorists who made the case that "the social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits" and that CEOs should be paid primarily in stock so that their incentives would be allied with the interests of stockholders thought that they would make the economy more prosperous for all. They didn't mean to gut the economy, increase inequality, and create an opioid epidemic. But they did.

We expect the social media platforms to come to grips with the unintended consequences of their algorithms. But we have yet to hold accountable those who manage the master algorithm of our society, which says to optimize shareholder value over all. In my book, I describe today's capital markets as the first rogue AI, hostile to humanity. It's an extravagant claim, and I hope you dig into the book's argument, which shows that it isn't so far-fetched after all.

We need a new theory of platform regulation

In my book, I also wrote that future economic historians will "look back wryly at this period when we worshipped the divine right of capital while looking down on our ancestors who believed in the divine right of kings." As a result of that quote, a reader asked me if I'd ever read Marjorie Kelly's book The Divine Right of Capital. I hadn't. But now I have, and so should you.

Marjorie's book, written in 2001, anticipates mine in many ways. She talks about the way that the maps we use to interpret the world around us can lead us astray (that is the major theme of part one of my book) and focuses in on one particular map: the profit and loss statements used by every company, which show "the bottom line" as the return to capital and human labor merely as a cost that should be minimized or eliminated in order to increase the return to capital. This is a profound insight.

Since reading Marjorie's book, I've been thinking a lot about how we might create alternate financial statements for companies. In particular, I've been thinking about how we might create new accounting statements for platforms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon that show all of the flows of value within their economies. I've been toying with using Sankey diagrams in the same way that Saul Griffith has used them to show the sources and uses of energy in the US economy. How much value flows from users to the platforms, and how much from platforms to the users? How much value is flowing into the companies from customers, and how much from capital markets? How much value is flowing out to customers, and how much to capital markets?

This research is particularly important in an era of platform capitalism, where the platforms are reshaping the wider economy. There are calls for the platforms to be broken up or to be regulated as monopolies. My call is to understand their economics and use them as a laboratory for understanding the balance between large and small businesses in the broader economy. This idea came out in my debate with Reid Hoffman about his idea of "blitzscaling." If the race to scale defines the modern economy, what happens to those who don't win the race? Are they simply out of luck, or do the winners have an obligation to the rest of us to use the platform scale they've won to create a thriving ecosystem for smaller companies?

This is something that we can measure. What is the size of the economy that a platform supports, and is it growing or shrinking? In my book, I describe the pattern that I have observed numerous times, in which technology platforms tend to eat their ecosystem as they grow more dominant. Back in the 1990s, venture capitalists worried that there were no exits; Microsoft was taking most of the value from the PC ecosystem. The same chatter has resurfaced today, where the only exit is to be acquired by one of the big platforms—if they don't decide to kill you first.

Google and others provide economic impact reports that show the benefit they provide to their customers, but they also have to consider the benefit to the entrepreneurial ecosystem that gave them their opportunity. The signs are not good. When I looked at Google's financial statements from 2011 to 2016, I noted that the share of its ad revenue from third-party sites had declined from nearly 30% to about 18%. Amazon deserves similar scrutiny. Fifteen of the top 20 Kindle best sellers were published by Amazon.

There are other ways that these platforms have helped create lots of value for others that they haven't directly captured for themselves (e.g., Google open-sourcing Android and TensorFlow and Amazon's creation of Web Services, which became an enabler for thousands of other companies). Still, how do we balance the accounts of value extracted and value created?

We need a new theory of antitrust and platform regulation that focuses not just on whether competition between giants results in lower prices for consumers but the extent to which the giant platforms compete unfairly with the smaller companies that depend on them.

Augment people, don’t replace them

Enough of the news that expands on the darker themes of my book!

The best news I read in the 10 months since I finished writing the book was the research by Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute that shows that ecommerce is creating more and better jobs than those it is destroying in traditional retail. "To be honest, this was a surprise to me—I did not expect this. I'm just looking at the numbers," Mandel told Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times. Here is Mandel's paper.

This report nicely complemented the news that from 2014 to mid-2016, a period in which Amazon added 45,000 robots to its warehouses, it also added nearly 250,000 human workers. This news supports one of the key contentions of my book: that simply using technology to remove costs—doing the same thing more cheaply—is a dead end. This is the master design pattern for applying technology: Do more. Do things that were previously unimaginable.

Those who talk about AI and robots eliminating human workers are missing the point, and their businesses will suffer for it in the long run. There's plenty of work to be done. What we have to do is to reject the failed economic theories that keep us from doing it.

That's my call to all of you thinking, like me, about what we've learned in the past year, and what we must resolve to do going forward. Give up on fatalism—the idea that technology is going to make our economy and our world a worse place to be, that the future we hand on to our children and grandchildren will be worse than the one we were born into.

Let's get busy making a better world. I am optimistic not because the road ahead is easy but because it is hard. As I wrote in the book, "This is my faith in humanity: that we can rise to great challenges. Moral choice, not intelligence or creativity, is our greatest asset. Things may get much worse before they get better. But we can choose instead to lift each other up, to build an economy where people matter, not just profit. We can dream big dreams and solve big problems. Instead of using technology to replace people, we can use it to augment them so they can do things that were previously impossible."

Let's get to work.

Continue reading What’d I miss?.

http://ift.tt/2mczJ3n

0 notes