#things people who write like this should be taught: 1 poetry is an option and its one very different from other kinds of literature 2 you c

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#shut the fuck up#cant believe they are making us read this#things people who write like this should be taught: 1 poetry is an option and its one very different from other kinds of literature 2 you c#can think of something nice or perhaps interesting but not pretend it is of importance and make it into a whole “field of study” when it do#snt mean anything#god im so fed up w this#you will never be heidegger let it go#no one will ever be him againnnnnn

0 notes

Text

Introducing Osric Bright, the reckless film director, screenwriter, and actor

Character Profile

Full Name: Osric Hadrian Bright

Nickname(s): Oz, Ozzie

Birthday: April 12, 1972

Age: 34 (in 2006), 52 (Currently)

Current Residence: Astoria, Oregon (perhaps he moves to California later)

Blood Status: Half-blood

House: Thunderbird (also chosen by Horned Serpent)

Wand: Ebony, Thunderbird tail feather, 14 1/4, unyielding flexibility

Patronus: Weasel

Strengths: intelligent, confident, creative, curious, charming, generous

Neutral: independent

Weaknesses: a bit cocky, reckless, impulsive, impatient

Likes: film, photography, walking through forests, exploring abandoned places with friends, reading, writing, theatre

Dislikes: asking for help, being talked down to

Best Subject: No-Maj Studies, Transfiguration, Magical History

Worst Subject: Potions

Third Year Options/Electives: Magical History of the United States of America, Native American Witchcraft

Extracurricular Activities: Drama Club, Poetry Club, SIFNIAC Club (Students in Favor of No-Maj Interaction and Assimilation of Culture) (Secretary)

Faceclaim: Johnny Depp (especially in Secret Window)

Fun (or Not so Fun) Facts:

Osric is the child of a No-Maj father and Magical mother. His father abandoned the family when he was 7 and his sister Miranda was 4, resulting in his mother's long period of depression. As he got older, he began to see his abandonmemt as a good thing because he never truly loved them.

Osric knows a lot about No-Maj technology. He is mostly taught himself since the age of about fourteen. He often helps out at the tecnology center on the Ulvermorny campus.

He can be quite generous to people he loves and is genuinely a fun guy to be around. However, people should be aware that they will be involved in his shenanigans.

Osric LOVES Halloween and goes all out in terms of decorations and costumes. He and his girlfriend Nellie love to wear couple costumes. His Halloween parties are legendary in Astoria where he lives.

Osric occasionally acts in his own films. One film stars him as a detective with a vaguely French accent. It is exclusively made for No-Majes which causes him to get in trouble with magical law enforcement who believe it violates the law that forbids showing magic to No-Majes. Osric argues that No-Majes assume they are only seeing what they believe to be really good special effects. Ultimately, the film becomes a cult classic with mysterious origins. By the way, Osric's character looks like Dean Corso from the film The Ninth Gate.

Osric is very prone to writer's block and burnout which causes him to sulk and eat a lot of junk food.

Family & Friends

Mother: Sibylla Francesca (née Shoemaker) Bright (fc: Carol Kane)

Renowned theatre actress

Drama teacher and therapist

Gives tarot readings on the side

Fully supports her son's aspiration to be a filmmaker

Father: William Jeremiah Bright

Younger Sister: Miranda Catherine Bright (fc: Linda Cardellini)

Herbologist

Embarassed of her brother's antics

Unlike Osric, Miranda is quiet, patient, and insecure.

Osric sometimes gathers herbs for his sister 💚🥰

Maternal Grandfather: Troy Everett Shoemaker (fc: Lee Marvin)

Maternal Grandmother: Eulalia Francine (née Mears) Shoemaker (fc: Piper Laurie)

Paternal Grandfather: Thaddeus Bright

Paternal Grandmother: Evelyn (née Jenkins) Bright

Evelyn occasionally calls Sibylla to check on Osric and Miranda but only started after her son William had already abandoned them which rubs Osric the wrong way.

Girlfriend: Eleanor "Nellie" Ambrosia Kingsley (fc: Heather Graham)

Actress and frequent co-star of Osric's

Fellow member of the Drama Club at Ilvermorny

Friend: Quintessa Torres (fc: Elizabeth Peña)

Fellow member of the Poetry Club at Ilvermorny

At first she creeped out Osric but then he started to appreciate her interesting way of seeing things

Pet: A tabby cat named Salem (after Stephen King's Salem's Lot)

Divider art credit goes to @adornedwithlight. Thank you!

#osric bright#my ocs#harry potter original character#harry potter oc#original character#mort rainey#mort fans may like this#johnny depp

1 note

·

View note

Note

hello pia! feel free to delete this if it’s too personal but i’d love to hear about your degree, what you learned from it, and how you think it has informed the way you write (whether it has or hasn’t!). i’m studying for a different degree, still humanities, but i’d love to hear about your degree since i.. well when i was in hs i didn’t know that it was an option. also if the above is too personal, please recommend some texts to learn abt mass comms .. thank you!

Hi anon,

I did my degree/s (Media Studies + Mass Communications majors, Scriptwriting (Drama, Film, Short Film) + Creative Writing (Poetry, Short Story, Literature, SFF) minors) back in 1999, so honestly, some of the information I learned then is out of date, and you're definitely better off looking at a university curriculum now for decent texts on mass communications. Even the Masters I did over 10 years ago, lol. I am an old.

You have to understand when I was in university for Mass Comm, the internet as we know it, and social media, literally didn't exist. And though 'Rupert Murdoch still owns a ton of Telcos' is still true, things like Wikipedia didn't exist, lol. The 'please don't use Wikipedia as a reference' didn't exist as a sentence, because Wikipedia just...didn't exist.

The media landscape has changed.

I've kept up with aspects of media studies that interest me (representations of mental health in the media, for example), but since the university texts still often cost hundreds of dollars, I can't get a ton of them every year and read them. You might be surprised what you can find in university bookstores in the clearance section, because books aren't in the curriculum anymore but are still likely to be 15 years more up-to-date than what I was taught with, lol.

I don't really know how to answer your specific questions though. There were a lot of different units within the degree, so I learned a lot from it, I don't know how to condense that down.

Probably the most important things I took with me are that media (fiction) does not have a 1:1 correlation with reality, and that we are not all mindless vessels with an inability to negotiate the media we watch (otherwise we'd buy everything in advertising ever), people who believe 'high art' is better than 'low art' are elitist ignorant dicks who don't actually understand art at all (if you've ever disparaged reality TV or soap operas, you are in this category, with soap operas giving you a side order of heavy misogyny to boot), media literacy is crucial and needs to be taught and prioritised on par (if not higher than) english fiction literacy (kids engage in more media than books, they should have more media literacy than book literacy), and that it's always important to know the politics and values of the people who own the news media you're watching (and that almost all news media is homogenised).

The biggest gift it gave me was to entirely remove my shame over watching or consuming any kind of media. I don't know what a guilty pleasure is, because guilty pleasures are a sign that you have some more work to do on unpacking your issues (often internalised misogyny believe it or not) over watching certain shows or listening to certain music etc. and finding joy in it. I feel NO shame in anything I watch, rewatch, love, get the most out of. Anon, I have done assignments on Big Brother and gotten high distinction/s for it. I've watched Misfits and gotten high distinction/s for it. I'm in the Golden Key Society because I watched a lot of Studio Ghibli and a lot of romcoms. Media studies does what creative writing doesn't - unpacks all your shame over enjoying different genres (sadly creative writing teaches a lot of that shame and can genre shame as well, it's extraordinarily outdated in many curriculums in that way).

It is so liberating to just watch whatever the fuck I want, and listen to whatever music I want, and not give a shit whoever knows I watch or listen to it. Like, I just... literally who cares. It's all art. It all means something and then I get to choose its further meaning. I get to decide what media I won't consume and why (usually around the politics and actions of the creator/s or actor/s, JKR can go to hell, or just not liking the show - I also feel no shame not liking things that everyone else likes), but it's never a choice based in shame or guilt. It is...truly, such a wonderful feeling when you realise there's literally no reason on this earth to have a guilty pleasure if you can think for yourself and understand why you've been conditioned to feel 'ashamed' for watching certain genres (surprise, it's usually racism or xenophobia or misogyny!)

Like, I did a unit called Psychology, Psychoanalysis and Cinema (Psych Psych and Cinema as we called it), which was a tremendous amount of fun and let me know that psychology is literally in everything but that representations of psychology in literally everything tends to be not great lmao. I did a unit called Postmodern Wetlands which literally analysed the relationship between swamp representation in mass media (particular horror films as relating to the monstrous feminine) and what that means for environmentalism which changed my entire relationship to my body and the environment permanently. Idk how to describe that unit to anyone who hasn't taken it, but it was literally life-changing, lol.

It definitely influences my writing style, partly because I write serials based off of like... scriptwriting techniques I was taught for television drama back then. In terms of how media studies influences it - well mass communications probably not so much, and then media studies a whole lot, lol. (Mass Comm =/= Media Studies. One focuses on telecommunications/telcos/ISP providers/internet cables even, politics and the vehicles with which we spread mass media, the second one focuses more on the analysis of the products/works/pieces of art that end up on that mass media. One is a lot more discussion of 'which television stations do China / Fairfax / Murdoch own' or 'how are those internet sea cables going and how's the terrorism around that?' vs. 'what messages does the TV on each of these stations send').

But media studies influences my writing a ton, but I couldn't tell you how anon, aside from those two units I specifically mention above lol. Oh and the fact that we had to take a mandatory philosophy unit called Critical Thinking, which should be mandatory for every degree. That definitely taught me how to think critically, which...a lot of people don't know how to do! I probably couldn't even tell you the rest of how it influenced me, if you asked me 2 decades ago when I was actively studying it. I'd like to think it just makes me a more nuanced writer, and absolutely Teflon when it comes to fanpol / antis / anti-shippers, lol. But who knows!

I still think looking at current university curriculums for Media Studies (also known as Media Analysis in some other countries) is probably the best place to find recs. But you can also check out the books on media in my Goodreads list and go by star rating.

#asks and answers#pia on media studies#media studies and mass comm#they're both very different#you can do media studies and not know anything about mass comm#and vice versa#but they do go hand in hand#mass comm is still an area i find fascinating#because it's where the big politics are in the world#and also where the terrorism etc. is#but it can get heavy very quickly for that reason

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Be curious. Be humble. Be useful.

I was invited to give the annual Taub Lecture for graduating Public Policy students at the University of Chicago, my alma mater and the department from which I graduated. This is what I came up with.

---

I am incredibly grateful and honored to be here tonight. The Public Policy program literally changed my life.

My name is Ben Samuels-Kalow, my pronouns are he/him/his. I’m a 2012 Public Policy graduate, and I will permit myself one “back in my day” comment: When I was a student here, the “Taub Lecture” were actual lectures given by Professor Taub in our Implementation class. I’ve spent the last nine years teaching in the South Bronx. For the past two years, I have served as Head of School at Creo College Prep, a public charter school that opened in 2019.

I was asked tonight to tell you a bit about my journey, and the work that I do. My objection to doing this is that there is basically nothing less interesting than listening to a white man tell you how he got somewhere, so I'll keep it brief. I grew up in New York City and went to a public high school that turned out Justice Elena Kagan, Chris Hayes, Lin-Manuel Miranda, among many others…none of whom were available tonight.

We, on this Zoom, all have one thing in common — we have been very, very close to graduating from the University of Chicago. I have never sat quite where you sit. I didn’t graduate into a pandemic. But the truth is that everyone graduates into a crisis. The periods of relative ease, the so-called “ends of history”, even the end of this pandemic, are really matters of forced perspective. This crisis isn’t over. Periods of relative peace and stability paper over chasms of structural inequality.

You went to college with the people who will write the books and go on the talk shows and coin the phrases to describe our times. You could write that book. You could go into consulting and spend six weeks at a time helping a company figure out how to maximize profits from their Trademark Chasm Expanding Products.

You could also run into the chasm.

What is the chasm?

It is the distance between potential and opportunity. It is a University on the South Side of Chicago with a student body that is 10% Black and 15% Latinx, with a faculty that is 65% white.

It is eight Black students being admitted to a top high school in New York City...in a class of 749.

What is the chasm?

The chasm is that in our neighborhood in The Bronx, where I’m standing right now, 1 in 4 students can read a book on their grade level, and only 1 in 10 will ever sit in a college class.

It is maternal mortality and COVID survival rates. The chasm is generational wealth and payday loans.

It is systemic racism and misogyny.

It is the case for activism and reparations.

In my job, the chasm is the distance between the creativity, brilliance, and wit that my students possess, and the opportunities the schools in our neighborhood provide.

In the zip code in which I grew up in New York City, the median income is $122,169. In the zip code where I have spent every day working since I graduated from UChicago, the median income is $30,349. The school where I went to 7th grade and this school where next year we will have our first 7th grade are only a 15 minute drive apart.

In my first quarter at UChicago, I joined the Neighborhood Schools Program, and immediately fell in love with working in schools. I joined NSP because a friend told me how interesting she found the work. I’d done some tutoring in high school, and had taught karate since I was 15. I applied, was accepted, and worked at Hyde Park Academy on 62nd and Stony Island in a variety of capacities from 2008 to 2012.

At the time, Hyde Park Academy had one of very few International Baccalaureate programs on the South Side, and every spring, parents would line up out the door of the school to try to get their rising 9th grader in. I worked with an incredible mentor teacher and successive classes of high school seniors whose wit, creativity, and skill would've been at home in the seminars and dorm discussions we all have participated in three blocks north of their high school.

In my work at Hyde Park Academy, I learned the first lesson of three lessons that have shaped my career as a teacher. Be curious. I had been told in Orientation that there were “borders” to the UChicago experience, lines we should not cross. I am forever grateful to the people who told me to ignore that BS. Our entire department is a testimony to ignoring that BS. We ask questions like, why did parents line up for hours to get into what was considered a “failing” high school? Why had no one asked my kids to write poetry before? Why are they more creative and better at writing than most of the kids I went to high school with, but there is only one IB class and families have to literally compete to get in? I learned as much from my job three blocks south of the University as I did in my classes at the University...which is to say, I was learning a LOT, but I had a lot more to learn.

I knew I wanted to be a teacher from my first quarter here. I did my research. The Boston Teacher Residency was the top program in the country, so I applied there. I was a 21 year old white man interested in education, so...I applied to Teach for America. In the early 2010’s, I looked like the default avatar on a Teach for America profile. It was my backup option. I was all in on Boston, and was sure, with four years working in urban schools, a stint at the Urban Education Institute, and, at the time, seven years of karate teaching under my belt, I was a shoe in.

I was rejected from both programs. Which brings me to my second lesson. Be humble. We are destined for and entitled to nothing. There is an aphorism I learned from one of my favorite podcasts, Another Round: "carry yourself with the confidence of a mediocre white man." If you are a mediocre white man, like me, do as much as you can not to be. If you look like me, you live life on the "lowest difficulty setting." This means I need to question my gifts, contextualize my successes, and actively work against systems of oppression that perpetuate inequity.

Over the last two years, I have interviewed over 300 people to work at this school. There are a series of questions that I ask folks with backgrounds like myself:

Have you ever lived in a neighborhood that was majority people of color?

Have you ever worked on a team that was majority people of color?

Have you ever worked for a boss/supervisor/leader who was a person of color?

The vast majority of white folks, myself at 21 included, could not answer “yes” to these three questions. This is disappointing, but I've also lived and worked in two of the most segregated cities on this continent, so it is not surprising. By the time I sat where you’re sitting now, I had learned a lot about education policy and sociology. I'd taken every class that Chad offered at the time. I'd worked at UEI, I'd worked in a South Side high school for four years, and I still thought I was entitled to something. Unlearning doesn't usually happen in a moment, and I certainly didn't realize it at the time, but these rejections were the best thing that has happened to me in my growth as a human.

I moved back home to New York, was accepted to my last-choice teaching program, and started teaching at MS 223: The Laboratory School of Finance & Technology. I ended up teaching there for 5 years. I had incredible mentors, met some of my best friends, started a Computer Science program that’s used as a model at hundreds of schools across New York City…and most importantly, while making copies for Summer School in July of 2015, I met my wife.

All this to say — if you aren’t 100% convinced that what you’re doing next year is Your Thing, keep an open mind…and make frequent stops in the copy room.

I learned that teaching was My Thing. I didn't want to do ed policy research. I got to set education policy, conduct case studies, key informant interviews, run statistical analysis…with 12 year olds. This was the thing I couldn’t stop talking about, reading about, learning about. I really and truly did not care about the “UChicago voices” of my parents and my friends who kept asking what I was going to do next. My answer: teach.

If you look like me, and you teach Computer Science, there are opportunities that come flying your way. I was offered jobs with more prestige, jobs with more pay, jobs far away from the South Bronx. I was offered jobs I would have loved. But I’d learned a third lesson: be useful. If you have a degree from this place, people will always ask you what the next promotion or job is. They will ask "what's next for you" and they will mean it with respect and admiration.

Here’s the thing: teaching was what’s next. “But don’t you want to work in policy?” Teaching is a political act. It is hands-on activism, it is community organizing, it is high-tech optimistic problem-solving and low-tech relationship building. It is the reason we have the privilege of choosing a career, and it is a career worth choosing.

I had internalized what I like to call the Dumbledore Principle: “I had learned that I was not to be trusted with power.” This meant unlearning the very UChicago idea that if you were smart and if you think and talk like we are trained to think and talk at this place, you should be in charge. The best things in my life have come from unlearning that. Learning from mentors to never speak the way I was praised for in a seminar. Learning from veteran teachers how to be a warm demander who was my authentic best self...and more importantly brought out the authentic best self in my students. Being useful isn't the same thing as being in charge…and that is ok.

I believe this deeply. Which is why, when I was offered the opportunity to design and open a school, my first thought was absolutely the hell no. I said to my wife: “I’m a teacher. Dumbledore Principle — we’re supposed to teach, make our classrooms safe and wonderful for our kids.”

I also knew that teaching kids to code wasn’t worth a damn if they couldn’t read and write with conviction, so I started looking for schools that did both — treated kids like brilliant creatives who should learn to create the future AND met them where they were with rigorous coursework that closed opportunity gaps. In our neighborhood, there were schools that did the latter, that got incredible results for kids. Then there was my school, where kids learned eight programming languages before they graduated, but at which only 40% of our kids could read.

We were lauded for this, by the way. 40% was twice the average in our district. We were praised for the Computer Science — the mayor of New York and the CEO of Microsoft visited and met with my students. It felt great. I wasn’t convinced it was useful.

Kids in the neighborhood where I grew up didn’t have to choose between a school that was interesting and a school that equipped them with the knowledge and skills to pursue their own interests in college and beyond. Why did our students have to choose? I delivered this stressed-out existential monologue to my wife that boiled down to this: every kid deserves a school where they were always safe, and never bored. We weren’t working at a school like that. I was being offered a chance to design one. But…Dumbledore principle.

My wife took it all in, looked at me, and said: “You idiot. Dumbledore RAN a school.”

Friends, you deserve a partner like this.

The road to opening Creo College Prep, and the last two years of leading our school as we opened, closed, opened online, finished our first year, moved buildings, opened online again, opened in-person (kind of) and now head into our third year, has reinforced my lessons from teaching — be curious, be humble, be useful. These lessons are about both learning and unlearning. A white guy doing Teach for America at 21 is a stereotype. A white guy starting a charter school is a stereotype with significant capital, wading into complicated political and pedagogical waters. The lessons I learn opening a school and the unlearning I must do to be worthy of the work are not destinations, they are journeys.

Be curious

I didn’t just open a school. Schools are communities, they are institutions, and they are bureaucracies. If you work very, very hard, and with the right people, they become engines that turn coffee and human potential into joy and intellectual thriving capable of altering the trajectory of a child’s life.

First you have to find the right people. I joined a school design fellowship, spent a year visiting 50 high-performing schools across the country, recruited a founding board of smart, committed people who hold me accountable, and spent time in my community learning from families what they wanted in a school. There is studying public policy, and then there is attending Community Board meetings and Community Education Council Meetings, and standing outside of the Parkchester Macy's handing out flyers and getting petition signatures at Christmastime next to the mall Santa.

I observed in schools while writing my BA, and as a teacher, but it was in this fellowship that I learned to “thin slice,” a term we borrowed from psychology that refers to observing a small interaction and finding patterns about the emotions and values of people. In a school, it means observing small but crucial moments — how does arrival work, how are students called on, how do they ask for help in a classroom, how do they enter and leave spaces, how do they move through the hallways, where and how do teachers get their work done — and gleaning what a school values, and how that translates into impact for kids. Here’s how I look at schools:

Does every adult have an unwavering belief that students can, must, and will learn at the highest level?

Do they have realistic and urgent plans for getting every kid there? Are these beliefs and plans clear and held by kids?

Are all teachers strategic, valorizing planning and intellectual nerdery over control or power?

Is the curriculum worthy of the kids?

Can kids explain why the school does things they way they do? Can staff? Can the leader?

If I'm in the middle of teaching and I need a pen or a marker, what do I do? Is that clear?

What’s the attendance rate? How do we follow up on kids who aren’t here?

How organized and thoughtful are the physical and digital spaces?

Are kids seen by their teachers? Are their names pronounced correctly? Do their teachers look like them? Do they make them laugh, think, and revise their answers?

Would I want to work here? Would I send my own kids here?

Be humble

I learned that there are really two distinct organizations that we call “school.” One is an accumulation of talent (student and staff) that happens to be in the same place at the same time, operating on largely the same schedule.

These were the schools I attended. These are schools you got to go to if you got lucky and you were born in a zip code with high income and high opportunity. These are schools where you had teachers who were intellectually curious, and classmates whose learning deficits could be papered over by social capital…and sometimes, straight up capital.

“Accumulation of talent” also describes the schools I worked at. These were schools where if you got lucky and you were extraordinary in your intelligence, determination, support network, and teachers who’d decided to believe in you, you became one of the stories we told. “She got into Cornell.” “That whole English class got into four year colleges.”

Most schools in this country, it turns out, are run like this. I knew all about local control and the limits of federal standards on education and the battles over teacher evaluations and so much other helpful and important context I learned in my PBPL classes. But when thin-slicing a kindergarten classroom in Nashville on my first school visit of the Fellowship, I saw a whole other possibility of what “school” can be.

School can be a special place organized towards a single purpose. One team, one mission. Where the work kids do in one class directly connects to the next, and builds on the prior year. Where kids are treated like the important people they are and the important people they will be, where students and staff hold each other to a high bar, where there is rigor and joy. A place where staff train together so that instead of separate classrooms telling separate stories about how to achieve, there is one coherent language that gives kids the thing they crave and deserve above all else: consistency.

We get up every morning to build a school like that. It’s why my team starts staff training a month before the first day of school. It’s why we practice teaching our lessons so that we don’t waste a moment of our kids’ time. It’s why everyone at our school has a coach, including me, so we can be a better teacher tomorrow than we were today. It’s why we plan engaging, culturally responsive, relevant lessons. It’s how we keep a simple, crucial promise to every family: at this school, you will always be safe, and you will never be bored.

Be useful

Statistically speaking, it is not out of the realm of possibility that several of you will one day be in a position to make big sweeping policy changes. You will have the power to not only write position papers, but to Make Big Plans. I will be rooting for you, but I hope that you won’t pursue Big Plans for the sake of Big Plans.

The architect who designed the Midway reportedly said "make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood." I had that quoted to me in several lectures at this school, and you know what?

It’s bullshit.

I am asking you not to care about scale. Good policy isn’t about scale, it’s about implementation, and implementation requires the right people on the ground. Implementation can scale. The right people cannot. We can Make Big Plans, but every 6th grade math class still needs an excellent math teacher. That's a job worth doing. I could dream about starting 20 schools, but every school needs a leader. That’s a job worth doing. Places like UChicago teach us to ask "what's next" for our own advancement, to do this now so we can get to that later. I learned to ask "what's next" to be as useful as possible to as many kids as I have in front of me.

I hold these two thoughts in my mind:

The educational realities of the South Bronx have a lot more to do with where highways were built in our neighborhood than with No Child Left Behind or charter schools, and require comprehensive policy change that address not only educational inequity, but environmental justice, and systemic racism.

The most useful policy changes I can make right now are to finalize the schedule for our staff work days that start on June 21, get feedback on next year’s calendar from families, and finish hiring the teachers our kids deserve.

I will follow the policy debates of #1 with great interest, but I know where I can be useful, and I’ll wake up tomorrow excited to make another draft of the calendar. I hope you get to work on making your Small Plans, and I will leave you with the secret — or at least the way that worked for me:

Find yourself people who are smarter than you and who disagree with you. Find problems you cannot shut up or stop thinking about. Do what you can’t shut up about with intellect and kindness. Use the privilege and opportunity that we have because we went to this school to make sure that opportunity for others does not require privilege. Run into the chasm.

Be curious, be humble, be useful.

Thank you.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Make a Move Just to Stay in the Game (part one)

oh look, it’s jules, back on her au.

what can i say, i love this thing so much. @ichlugebulletsandcornnuts and i have worked so hard on it and it’s practically took on a life of its own, so here’s installment three, a bit more soft, but there is definitely some not soft in there too. featuring awesome new character!

i’m going to link my masterpost, so if you’re new, you can go back and read the whole au from the start, which is called hold onto me, you’re all i have.

so yeah! this one is four parts, all a bit short bc otherwise they’d be really long.

[Part 1: Feelin’ My World Start to Turn]

as ward of the queen, katherine was now above her former colleagues in rank, which brought its own challenges and benefits in turn. she still spends most of her time with jane, but she suddenly realises she has a lot more free time where she doesn’t have anything to do now her lady-in-waiting duties had been removed. what she also realises, however, is that she’s rather unprepared for royal life. she’s not the only person who’s noticed, either; on one day, she overhears two courtiers saying some less than pleasant things about her, mostly along the lines that she’s a stupid, uneducated girl who doesn’t know the first thing about being nobility. it hurts to hear those things about her and it sticks in her mind that evening as her and jane sit by the fireplace, jane embroidering and katherine lost in her own world.

“mum?” katherine says very suddenly, and jane glances over at her.

“yes, love?”

katherine pauses a moment before speaking hesitantly. “what kinds of things are ladies of my rank supposed to know?”

jane was obviously not expecting that question. she looks taken aback for a moment, before her brows furrow together and she looks off at the wall.

“well princesses generally have very well-rounded educations.” she thinks for a moment. “arithmetic, history, studies of trade and geography, a language of some sort...” she trails off. “why do you ask, love?”

katherine looks ashamed, but can’t bring herself to lie. “just some things some people were saying earlier.” she shrugs. “that i wasn’t smart enough, stuff like that.” she tries to sound nonchalant, but the words really did hurt. she wanted to be enough for jane.

“oh, love,” jane frowns. “you’re definitely smart enough-”

“but i don’t know a lot of those things,” katherine admits. “i don’t know any other languages, i barely studied any geography, and i’ve never had an arithmetic lesson in my life.” she shrugs slightly, looking embarrassed. “they only taught us to read and write, and things like dancing and-” she stops before she can mention music; it’s not something she wants to think about right now. “there’s so much I don’t know.”

jane can’t entirely argue with katherine. she knows that the girl didn’t have the easiest go, but she never contemplated katherine’s education, or lack thereof.

“what about a tutor, love?” jane suggests. “i’ll bring in some one in to teach you these things. there are plenty of noblemen that would-“

she sees katherine’s face change in that instant, from a curious excitement to immediate fear. it takes her a moment, but she works out the cause.

“or a noblewoman?”

jane’s last words almost take katherine by surprise, as if she hadn’t realised that could be an option. “do... do you think there’s an educated woman who’d want to teach me?” she asks, slightly shyly. jane nods.

“i’m sure there are. I can ask around; I know several of the court have connections to educated circles, and i’m sure i could arrange a tutor to come to court to teach you - if that’s something you’d like, of course. it’s completely up to you, love.”

katherine smiles, not all that confidently but smiles nonetheless. “i’d like that a lot,” she admits shyly. jane grins brightly.

“of course, love, i’ll look into it.”

jane does her thorough research, and one name comes up again and again, one catherine parr.

catherine parr is a humanist, a woman who has written her own book, and by all accounts has a kind but scholarly temperament. from her research, jane discovers that catherine parr and her husband had fallen out of favour with the king a few years back, but recently had been forgiven. by lucky coincidence her husband, John Neville (or Latimer, as most referred to him as) was at court visiting and jane manages to get a letter to him, asking for the services of his wife to tutor lady katherine, ward to the queen consort of england. the letter was more of a formality; with the latimers only just coming back into favour, they must have thought it would be unwise of them to refuse jane’s request, although jane of course wouldn’t do anything to them if they did refuse.

catherine, upon meeting the ward, gave off an air of confidence, unwavering in her sense of self.

she doesn’t even curtsy to katherine.

she bows. long and low.

“it’s an honor to meet you, lady katherine,” she says formally yet genuinely.

katherine looks confused for a moment, before returning a curtsey and smiling slightly. “likewise, lady parr.”

parr waves a hand. “no formalities needed, please.”

katherine smiles wider. she likes her new tutor already.

their first lesson is the day after parr arrives at court. katherine is slightly nervous but mostly excited; she’s always liked learning, and she’s determined to prove to everyone else and herself that she’s smart enough to be good enough. parr greets her with a smile, sat on one side of a small table, and katherine takes the chair opposite her. there’s some books stacked on the floor next to the table and an ink pot and quill next to several sheets of paper.

“today is just finding out what you know, to give me a better idea of where to start off,” parr explains. “please, remember i’m not here to judge you, and if you do not know something then you shouldn’t feel ashamed. that’s what these lessons are for, after all.”

katherine shyly nods. the edge of parr’s lips twitch up in a half-smile as katherine picks up the quill and looks to her earnestly.

“tell me all that you know about christopher columbus’ endeavor to the new world,” parr instructs. she picks up a book and begins to thumb through as katherine writes as much as she can. she fills just over one sheet before she’s finished, striking a line across and looking back to parr.

“explain what you can about the salt trade.”

this question katherine can hardly manage a few lines on; the education she’d had never taught her anything about trade. that was for men, and they hadn’t thought it necessary to tell a girl anything about it. she desperately tries to drum up anything else she could possibly think of on it but gives up with a sigh, cheeks flushing slightly. to her surprise, parr doesn’t comment, simply asking her to write a list of any wars the english had taken part in. question after question parr asks her until the paper has been filled up and katherine’s hand is starting to cramp from writing. parr takes the papers and offers katherine a kind smile.

“thank you. you may take a break while I read your responses, or if you’d prefer you can get a start on reading this.” she takes a book from the stack on the floor and places it in front of katherine. ‘UTOPIA - by thomas more’ the book reads, and katherine flips it open curiously.

“i wouldn’t worry about the more technical elements of more’s prose yet,” parr tells her. “the first read through i just want you to understand the basics.”

“um,” katherine interrupts quietly, blushing bright red. “i’m sorry, i can’t read this.”

the book was all in a different language. katherine wasn’t sure, but she’d guess it was latin. parr looks slightly surprised.

“i wasn’t told you didn’t know latin,” she says, and katherine internally berates herself for seeming stupid in front of her new tutor, but then parr smiles. “oh, you have a wonderful time ahead of you. latin is hard work, but you’ll learn to translate the most beautiful works of poetry and prose. i just have to adjust my lesson plans slightly.”

with their remain few hours before breaking for lunch, parr begins the latin lessons. she finds herself holding back many surprised smiles as just how quickly katherine is picking up the language, finding verb conjugations and basic sentence structure a piece of cake.

just after noon jane quietly knocks and pokes her head around the door. “is this a bad time?” she asks, seeing both women hunched over their papers.

parr looks up and smiles. “not at all, your majesty, come in.”

she crosses to katherine, who had yet to look up from her concentrated writing. she jumps slightly when jane lays a gentle arm around her shoulders, but quickly relaxes into the hold.

“how goes it, love?” jane asks, kissing katherine’s forehead.

katherine practically beams with a sort of quiet pride. “good, i think!” she sends a quick glance to parr for confirmation and parr nods, laughing slightly.

“more than good, i’d say. lady katherine has a remarkable aptitude for languages, your majesty. i’ve been thoroughly impressed.”

katherine lights up at the praise and jane grins at her, pride welling up in her chest.

“that’s fantastic, love.”

parr finishes jotting down a few notes before setting down her quill and shaking out her wrists.

“that should do it for now, lady katherine. we’ll reconvene in one hour?”

jane looks at her questioningly. “won’t you be joining us for lunch, lady parr?”

parr turns confused. “i suppose i was under the impression that-“

“oh, dear,” jane laughs slightly, “you simply must have lunch with us, right kat?” the girl nods enthusiastically, standing up. jane smiles again. “besides, i’d like a full report on how my little scholarly lady is doing.” she nudges katherine lightly in the ribs.

parr smiles gently. “well, in that case, i humbly accept your invitation.”

“wonderful,” jane claps her hands together. “i’m ready to hear about everything you’ve been working on.”

during lunch, katherine is incredibly chatty, practically unable to stop talking about the things she had learnt in the past few hours. she proudly recites some verb conjugations for jane, who offers a round of applause at the end, laughing slightly at her daughter’s childish glee at learning something new. parr chips in every so often to remind katherine of something or to voice her own praises.

jane feels pride rise in her very quickly, leaving her heart so full she can barely stand it.

parr excuses herself a few minutes early to get everything ready for the afternoon, and, as soon as she’s gone, jane pulls katherine into her arms, lightly kissing her temple.

“i’m already so proud of you, love,” she murmurs. “i know you’ll just continue to impress me.”

katherine smiles into her shoulder and hugs jane tightly. “thank you,” she says softly, “for giving me the chance.”

jane pulls back slightly, resting her hands on katherine’s shoulders. “and how are you finding your new tutor? she seems very nice.”

“she’s amazing!” katherine grins. “she didn’t get annoyed at me once and she explains everything so well.”

it warms jane’s heart to hear that katherine likes her new tutor, and it amazes her how much difference jane can see from the shy little girl who became her lady-in-waiting several months ago.

“i’m glad to hear that, love,” jane says quietly.

the grand clock in the corner chimes one strong note and falls silent, and katherine looks at jane almost a little sadly.

“back to it, kat,” jane gently instructs. she kisses katherine’s forehead. the girl had grown like a weed since they had first met; katherine used to barely hit jane’s nose, now they were exactly eye level. too much longer and katherine would be taller than jane herself.

she’s snapped out of her reverie by katherine saying goodbye. jane smiles, squeezing both of her hands gently.

“go keep making me proud, love.”

katherine blushes and dashed from the room, not wanting to keep parr waiting too long.

the woman is there waiting at the table when she enters.

“ready to continue?”

#six the musical#six musical#jane seymour#katherine howard#catherine parr#jules and jess write#make a move just to stay in the game#hold onto me you're all i have

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Dead Redemption 2 PC

Red Dead Redemption2 PC

The old west feels brand new again.

Oh Jesus Christ, what have you done? “Thomaschen 978 wants to know why a dozen carcasses and a couple of horse corpses are placed on rail tracks bordering the early industrial city and are the New Orleans stand-in St. Denis.” You killed half. village.” PC Games For Free

We are on round two of the recurring corpse pile. My poses got the idea to jump in front of the train after a few rounds of Lose Your Friends and Toss Them in the Sea in the Couple Friendly Strangers. Like GTA 5, Red Dead Redemption 2 has its own bowling minima, we explain to Chen in a roundabout way that provokes his fear. Die in the shared open world of Red Dead Redemption 2 and you’ll react fast enough to move your corpse around. Best RPGs games pc

The boy is in line with us. We should make it bigger. As the train comes around again, another pose tries to take us out. The chain defends us but does not bring it back to the tracks. He goes away screaming. Death of a true warrior.

Red Dead Redemption 2 could be the biggest, most humble videogame ball pit for an annoying story about impulsive children, the forced disintegration of the community, or simply a quiet and reflective hiking simulator. It’s just about what you need it to be, and it’s good at it.

Just hours before the corpse-bowling, I was alone through the icy forests, stepping into the long shadow cast across the snow by the rising moon. I heard a gunshot from a distance. The tracks of some wolves marked snow in the same direction. I saw them who won. Anytime I pay attention and look closely, RDR2 is the result of my curiosity. Best Racing games on pc

The mind-numbing expanse that makes up the vast world of RDR2 speaks to the creative force of a development team with an intense, obsessive dedication to realism (and all the money and time needed to do so). Like how my friends’ characters flare up when I fire a gun at them, how animal carcasses disintegrate over time, how NPCs react according to a sloppy or bloody outfit, how to stir through a doorway. Scares everyone everywhere.

It is hard to believe that RDR2 is so deep and wide and is also a harmonious, playable thing. I was already playing it for days worth the console version. This is why I am particularly disappointed that it ended up on the PC to some extent.

For every non-taught multiplayer adventure, disconnect or crash on the desktop, desktop. The rock star’s best storyline and character so far has been filmed through Frame Hutches’ slideshow and addressed over the launch weekend.

RDR2, one of the best Western games and one of the best open-world games I have ever released with enough stability issues, is recommended for the hard way until everything is completely smooth.

Morgan trail

EVERY PRETTY VISTA IS SOMETHING TO LOSE THROUGH ARTHUR’S EYES.

The story genre of Red Dead Redemption 2 follows the dying days of the Wild West. The sprawling industrial world faced the bandits and social downtrodden of Arthur Morgan’s small band, an imperfect but loyal, loving and self-reliant community.

Capitalism is reducing its value as resources to humans. Indigenous USA America is driven from the plains to make way for ‘civilization’ and commerce. The forests are brought down for timber, the hills are cut down for coal, and Morgan’s chosen family is caught in the middle, forced to flee, assimilate, or respond with violent protests is done. They do all three.

This is Rockstar’s most serious drama, and it’s really, really long. If you are running, the story ends after 40 to 50 hours and then continues for 10 to 15. The main story missions of Red Dead 2 feature distinctly rockstar fare: ride to a destination that is talking to everyone, tightly scripting though, entertaining things, riding, and chatting to the final destination.

Missions are often thrilling action sequences or artificially mundane pictures of wrench labor and trade, full of long-winded Bespoke animations, and outstanding performances. They are only hopelessly harsh, to the point where it feels like I am following the stage directions rather than playing the role of a vagabond in the Old West.

Step out of line in these campaigns and this is a failed situation. As opposed to Red Dead Online, there are very few of them that encourage players to think for themselves, each designed to advance the story. The RDR2 show is at least a spectacle of the slow pace of life in the Old West.

This is not the death and theatricality of a lifetime; My favorite missions include shoveling, drinking wine with a friend, proposing an old romance and riding a hot air balloon. Working through a greater rut, stricter tasks are considered meaningful in the end anyway, inspired by extraordinary, ambient world-building and characterization.

Side missions, minigames, small activities, and random world events — whether they hunt great guns, capture a play, or stumble upon a woman trapped under a horse — all set Arthur’s character and setting in subtle, rich ways. Please inform.

Nested in the third act of a fully animated and voice theatrical performance, something like 10 minutes, it is possible that the response button is pressed after an artist has included a telephone. Arthur would shout, “Hell with the telephone!” It is an optional activity, a long one, and an option is to react in that short window. I think most players will remember this, but this is Canad Response 1 through 3 because this is something Arthur would say, a rageless goofy set his way in the right way.

He would write complete, real diary entries about the 50-hour campaign, sketching memorable scenes and depicting the state of affairs of his chosen family, which people once knew changed their fortunes between hope and despair. It is meant to be a completely alternative reading, but a refreshingly intimate take on a masculine figure that unsettles many doubts and hopes as to the next person.

He sings himself on a lonely ride and lowers his old body in the mirror. He will have an exciting conversation with the horseshoe woman as he gives her a ride into town, both commenting on the troubles of working for wealthy, ungrateful men as a growing necessity. I feel it all. Best horror games on pc free

Hillbillies can capture him after making the camp, a couple may try to rob him after inviting him to dinner, a man with snakebite can come out of the forest by stumbling and tell him to suck venom is. These haphazard encounters portray brutal life on the fading frontier, as nature pushes back against inner poppers who want to change it. Arthur is the perfect vessel to see it

This is because Arthur Morgan is one of the darkest human characters I have played during a great turning point in American history, playing a playful, cruel and compassionate role according to differing theories.

The game world, beautiful as it is, is made more beautiful and tragic by how it is ready to play it on every occasion. Every beautiful vista has something to lose through Arthur’s eyes, power lines and train tracks, cut through the skies, and the rest of his life is slowly filling with factory smoke. Just about everyone sees a sad end in RDR2, too. This is a story that I might not sustain every moment, but I will not forget its brutal arc or the man in the middle of it all. God damn is it sad? An apocalypse that led to this.

Ren Der Reflection

Assuming that you are able to run it at high settings, the biggest strength of RDR2 is how it exquisitely renders the Old West setting on PC, drawing more attention to the nuanced details that make it. This is one of the best looking games I’ve seen and a rare experience that justifies a new GPU or CPU.

Better draw distance and a greater range of vegetation detail were added, making some vistas look photographic. Long shadows vary from walking or roaming between places to rides, to cute nature tours. Due to animal attacks, bullet holes, rain, mud, or rapid flow of blood, the markings on the clothes are caused by very high-resolution textures, which tell a very little story about your friends.

A new photo mode makes it easy to share those moments of amazement. The way the player rides on RDR2 for just sightseeing and sounds is an important feature. I am desperately trying to get an artistic portrait of my horse’s silhouette to sit against the moon, yet another self-proclaimed goal was tolerated by this ridiculously large complex game.

With 2080, i9-9900K and 32GB of RAM, I can run RDR2 mostly on ultra settings with some resource-intensive settings completely off or switched off. But some hardware combinations are proving troublesome for RDR2, leading to random crashes in some APIs and, more recently, to a hotfix, leading to hitching problems for some 4-core CPUs.

During the first weekend, I couldn’t spend more than an hour without crashing on the desktop, though Vulcan switched from DX12 (which gives me better framerates) back to static stuff. Sometimes the UI malfunctions and I cannot select a select or purchase option, the map fails to appear, or I get paged unexpectedly from game servers.

The graphics settings are almost too much as well, and probably confusing. In our test, only a handful of settings affected performance by more than 1-2 percent. Large residuals, the mapping between MSAA, volumetric lighting, and parallax occlusion, affect performance by 5 to 25 percent. Most of them don’t make a big visual difference anyway and are best left out.

The way the settings are presented is made to feel underdeveloped: a huge list with unclear presets that require tinkering to make RDR2 run in a satisfactory framerate. It is hard. The PC should be the best place to play, not the best place to play, after all, after a few patches. It’s a shame for a game to look good. upcoming pc games

Cowboy poetry Red Dead Redemption 2 PC

Like in singleplayer mode, in Red Dead Online I can make my goals reasonable and watch them. The problem is, it is basically hamstrung by a frustrating multiplayer leveling system that locks basic equipment and cosmetics behind long XP requirements that can meet hours, perhaps days,

The option is spending gold, premium currency, items and clothing to unlock them immediately. A fishing pole is not available until level 14. A damn fishing pole in an outdoor recreation game. This is not spectacular and is a terrible way to invest players.

out a basic suite of tools (fishing rod, bow, varmint rifle, nice hat, etc.), Red Dead Online opened up widely. I have largely ignored traditional matchmaking modes such as gunfights and horse races, cheap thrills, I will play much better versions in different games, to have fun. It led to the most inventive, serene, real, and sometimes buzzing echo I’ve ever had.

I once walked into the middle of a fire in Blackwater and took the player corpses one by one to the church cemetery. Some were captured and participated in the ‘burial’ of their friends. A corpse thanked me for the gesture. Later, in an extended streak of criminal activity, my pose and I caught another player and instead of killing them on the spot, we rode into the swamp and threw them into the garter infected waters. I got the idea to act like a friend. Best pc games 2017

On a less absurd note, I set myself a constant goal of earning strictly enough money from hunting to buy cool-weather gear and a fine rifle. I am going to hike in the mountains and find the best way to hide there, a wild mountain man adorned with animal skins, which almost touches the floor.

In the meantime, I’m stopping gunmen across the city by running through the streets and calling for a parley. I am participating in an eight-player ballroom. I am living the life of a normal cowboy in the best shepherd game. I hope it clears up soon.

RDR2 PC System Requirements

OS : Windows 7 SP1 64bit

Graphics Nvidia GeForce GTX 770 2GB / AMD Radeon R9 280

Processor: Intel Core i5-2500K / AMD FX-6300

Memory: 8 GB RAM

DirectX: Version 11 Or 12 Support

Storage: 150 GB

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

(forgive me for answering these as a post again, but again I don’t think I can do them justice in the chat box)

I plan on reading the nibelungenlied because a plot description sounds good, but I thought medieval people had a black and white view of everything *because* I read Beowulf (and a couple of the things Cynewulf wrote). It's literally the same plot and main character as A Trekkie's Tale. Seeing Tolkein's constant praise for Beowulf on my dash is one of the reasons I am so reluctant to read LOTR -- what if it sucks as much as Beowulf?

until I recently heard about the Nibelungenlied, I thought Europe just forgot how to write good stories some time after the cool ancient greek stuff

(not done with your post yet)

I read the rest and I am still hung up on you liking Beowulf

Again, it's the same exact story as A Trekkie's Tale

FWIW, I didn’t say I liked Beowulf. I like it fine, for the record--but it’s not the best in Anglo-Saxon poetry. It certainly wouldn’t make my top three.

I do not think the Anglo-Saxons had an unambivalent attitude toward the hero of Beowulf (or the other characters therein). Beowulf is a complicated, complicated topic, one I probably cannot do justice to, but suffice it to say it was written during the Christian era about the pre-Christian mythic past, and like all such works in the Anglo-Saxon corpus is exploring the interplay between two very different worldviews. One point of comparison might be The Wanderer, a poem that takes the form of a poetic monologue by a possibly-pagan figure of the old poetic, heroic tradition that’s bracketed by two sections that reveal the Christian sensibilities of the poet themselves, and which attempt to, if not resolve exactly, at least explore the tension between these two worldviews.

(And I say “Christian,” but don’t mistake me: the worldview of post-Christianization Anglo-Saxon England was very different from the worldview of, say, the religious right in the modern US, which is one connotation that might be evoked by that word; so if you prefer, think of them just as Late Migration Age and Early Medieval cultural differences, because these were changes in culture conditioned as much I think by changes in material and political and social circumstances as by religious ones.)

Beowulf isn’t to everyone’s tastes (though it’s often badly served by some deeply mediocre translations, Heaney’s much-vaunted one included), and part of this may be that it is epic: epic generally deals with flatter characters and more formulaic situations than other kinds of narrative, and a lot of the things that took getting used to on a first reading of Beowulf are like the things that took getting used to on a first reading of Tain Bo Cuailinge or the Epic of Gilgamesh: it’s an affected setting, emotionally and plot-wise, and while the “realist” narratives that make up the overwhelming majority of our cultural output these days (and “realist” as a style subsumes even fantasy and SF; it’s a term here for a set of stylistic conventions, not a judgement on plausibility) is no less affected, it’s affected in different ways, and we’re much more used to it.

I will say this also, though: Beowulf is not written as an Anglo-Saxon Mary Sue. He’s not unambiguously right or good; the Anglo-Saxons didn’t endorse burying your king with all your tribe’s treasure and then disbanding your tribe, and while the model of Germanic heroic literature was still influential in their poetry centuries later, it was not something they thought you should *emulate*: it was very much an element of (to them) their pagan past, something about which they had, I think it’s fair to say, conflicted feelings. Beowulf as a poem is descended from tales created in that past, but is 100% an artifact of the later, Christian era, a work of historical fiction in a mythic tone.

On Beowulf, I will add only this: 1) an Anglo-Saxon audience (as I do) would appreciate how a story like Beowulf is told as much as if not more than the actual content of the narrative; if the narrative seems insufficient, I can only plead the case of the poetry, which, again, suffers under the hand of mediocre translators. Alas, for Beowulf, your options seem to be translations by those who don’t know much about Beowulf or Anglo-Saxon poetry, like Heaney, or translations which are very literal and aimed at helping students trying to read it in the original. 2) As with narrative structure, our tastes in characterization are shaped by culture; if you want your heroes to appear to be the underdog at first and only pull off a triumph against overwhelming odds, a lot of ancient epic is going to come off as a series of Mary Sues, I think. Tastes change! There’s a reason that there’s a big cultural divide between popular literature and old literature, and there’s nothing wrong with finding old literature not to one’s taste. But I also don’t think you’re being fair to Beowulf with the comparison: there’s... a lot going on in that poem, both culturally and narratively. But I didn’t read Beowulf until I’d already been studying Anglo-Saxon literature for three years, and it was in the context of a year-long course taught by a terrifyingly knowledgeable woman who knows more about the subject than I could ever hope to, so idk, maybe none of that comes through in any of the modern translations.

I think a lot of what makes people go “old literature sucks” is really a case of wildly different aesthetic sensibilities--if what you’re looking to get out of a story is very different, yeah, you’re not gonna appreciate Piers Ploughman or Pilgrim’s Progress or w/e. But, I issue the following challenge: I think that even for highly specific modern tastes there is some great medieval literature. If you want something in a vivid narrative style very like modern novels, I recommend specifically the Old Norse sagas: Egil’s Saga is great; Njal’s Saga is even better. The more mythic sagas, like the Saga of Hervor and Heidrek, are still a lot of fun, even if the settings is a little less relatable.

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Handmaid’s Tale is nominated for 20 Emmy Awards this year, after winning 8 for Hulu last year including 2017’s Outstanding Drama Series. The first season of the television show is based on the novel of the same name, set in an oppressive, dystopian future in the Republic of Gilead which has overtaken the United States.

Not only was the television adaptation a critical success, Amazon lists The Handmaid’s Tale as the most read non-fiction book on Kindle and Audible in 2017, beating ‘A Game of Thrones’ and all of the ‘Harry Potter’ books. Author Margaret Atwood published the bestselling novel in 1985 and is not surprised that the totalitarian theme of the book is resonating with audiences today.

“We live in a very anxiety-producing moment because a lot of the received wisdom is being challenged and overturned,” says Atwood in her hometown of Toronto, Canada. “The world players are moving rapidly around the stage, taking positions that we’re not used to having them take, so it makes a lot of people anxious.”

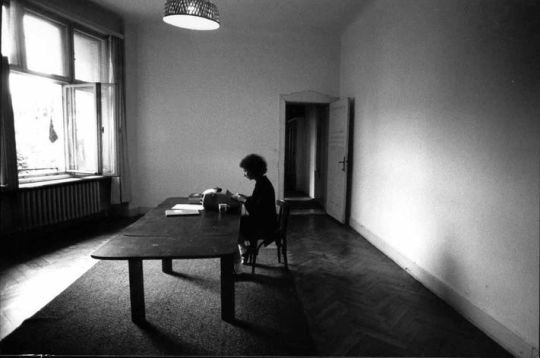

Atwood started writing The Handmaid’s Tale in 1984 while living in West Berlin on a grant that provided funding to filmmakers, writers and musicians to live and work in the West German district occupied by the allies.

“At that time it was a very dark, empty city, by which I mean there were a lot of vacant apartments,” says Atwood. “People didn’t want to live there, because it was surrounded by the wall. They brought in foreign artists to be there just so people wouldn’t feel so cut off.”

She says living through the Cold War in divided Berlin was instructive to the mood she created for Gilead in the book.

“We also visited East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Poland at that time,” says Atwood. “It informed the atmosphere but not the content if you can see what I mean. The experience of having people change the subject, being fearful of talking to you, not knowing who they can trust, all of that was there.”

Atwood finished writing the novel the following year in the United States, while working at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

“When I was writing it, we were still in an age in which America was seen as a beacon of light, of liberal democracy, a model for the rest of the world,” says Atwood. “We’re not there anymore, because the rest of the world has changed and so has America. That is why I think people are seeing The Handmaid’s Tale as more possible than they did when it was first published.”

A third season of the series that narrates the life of enslaved handmaid Offred, played by Elisabeth Moss, was recently announced by Hulu. The streaming service has 20-million subscribers and doesn’t release viewership numbers, but said in May that 2018′s season 2 premiere was streamed by twice the number of viewers as the season 1 premiere last year.

Atwood is currently a consultant on the television show and notes that she has no veto, though says she is generally happy with the direction the series has taken. She says she would like to see the oppressive Aunt Lydia survive the cliffhanger season 2 finale in which she was attacked by a handmaid, and hopes to see more of Offred’s best friend Moira who escaped from Gilead, in season 3.

Atwood is quick-witted in person, unpretentious and doesn’t miss a beat. She acknowledges that the cultural impact of Offred’s story has been significant.

“It’s become an international symbol of protest,” says Atwood. “Especially in situations in which women’s rights are in question, or are being removed from them.”

Dozens of women took to the streets in Buenos Aires this month wearing the red cloaks and white bonnets made famous by the subjugated women of The Handmaid’s Tale. The protestors are in support of a historic bill to decriminalize abortion that will be voted on by the Argentinian Senate on August 8. Demonstrators across the United States have worn similar outfits to protest a woman’s right to choose in the past.

It is not just abortion rights that The Handmaid’s Tale represents. Atwood mentions fair laws, fair pay, and equal pay for work of equal value as issues that need to be addressed today. The 78-year old resists labeling herself a feminist, noting that there are many definitions of the word, but sees Iceland as a shining light in terms of women’s rights.

“Iceland is probably a country that we should be studying because they’ve gone pretty far with equality, and their happiness quotient seems to be quite high.”

The Nordic country ranks number 1 in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index. Women make up 48% of elected representatives in parliament, and a new law introduced on January 1, 2018 mandates that companies prove that they pay men and women equally, or face fines.

“Does it make for a happier society on the whole if women have more equality? That does seem to be the case. Does it make for a more prosperous economy if women are engaged in the workplace and in decision making around the economy? That too seems to be the case,” says Atwood.

Atwood herself was born in Ottawa, Canada, the middle child of an older brother and younger sister. She credits her female relatives with providing her with invaluable lessons early in life.

“They were all pretty tough in their various ways, so my image of a competent woman did not come with a negligee and a box of chocolates,” says Atwood. “Being from a country that was pretty close to the frontier experience, I would say ‘Granny on the farm’ was more of a viable role model for me. I’ve got nothing against having your own toolkit, and knowing some elementary plumbing.”

Her no-nonsense attitude led her to a B.A. at The University of Toronto and a Masters at Harvard’s Radcliffe College. One of Atwood’s first jobs out of university was as a market research interview writer. She moved back to Canada in 1964 and taught English at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and published her first book, a collection of poetry the same year.

“When I first started in Canada, it wasn’t just that women weren’t viewed as serious writers. Writing itself was not viewed as a serious pursuit. One of the things we did to overcome it was we started publishing companies, some of which are still going, and I was the founder of one of those,” says Atwood, referring to the Canadian publisher House of Anansi.

The 78-year old has since lived and written in 7 countries and published 40 books. She received a writing fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation at age 44, just before starting work on The Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood is pleased to see the contemporary options now available to writers looking to finance their work, such as crowdsourcing platforms Patreon and Unbound.

“The main thing writers have to figure out to do is how to pay their bills,” says Atwood. “Patreon, they sponsor your project, whatever it is, and Unbound, they will crowdfund a book that they wish could be published. What writers need is time, and all of these things buy time. Are you going to stay up all night and have a day job? I’ve certainly done that. Or, are you going to not have to have a day job, and maybe get a bit more sleep?”

In addition to being an author, Atwood is a vocal advocate for environmental issues. The impact of climate change is a theme that runs through her work, and she notes particular concern at the state of the oceans and how food supply may impact women and children in the future.

Atwood’s Toronto-based company, O.W.Toad, states that it does not use air conditioners or purchase plastic water bottles, and when airplane travel is necessary carbon neutral credits are purchased. Publishing contracts specify that acid-free paper must be used.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, Atwood attributes Gilead’s declining birthrate on pollution and environmental mismanagement. She notes that everything that went into the novel had a historical precedence and that the producers of the television show have continued that principle in subsequent seasons. I asked her if when she was writing the book she believed the circumstances in the novel would come to fruition.

“Did I think it was going to come more true? No,” says Atwood. “But, I understood that that possibility was there.”

97 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I am looking at doing the Creative Writing MA in Paris,but I was just wondering what it was like in general? Like the modules and how big the course is etc?? It sounds so so good but i'm unsure at the moment if i want to apply. Especially since I'm low on money to pay for tuition... :(

hey! ah i am so pleased to hear you’re considering it! i’ll give you a brief rundown of what the course is like below the cut.

In Term One (Sept - Dec), the modules for Creative Writing are:

A choice between two compulsory modules:

- Fiction 1 - Poetry 1

And a secondary module unrelated to the first. I chose to do French Cinema, but there are lots of other options to do with art, literature, and other creative subjects. There should be a module guide on the website as I can’t remember them all.

I am not interested in poetry, so I chose Fiction 1 and French Cinema.

In Fiction 1 you get:

- 3 hours of taught lesson, once a week. So a three hour lecture/workshop.- A reading list of relevant novels relating to the theme of the week. It is expected that you read the novel before your class to prepare. - Each week, a different subject will be introduced. For example, in week one you might focus on character, in week two plot, and so on. - Half of the 3 hour lesson is focused on the lecture (your teacher will introduce the subject, maybe do a presentation, and then you’ll discuss the book). - The second half of the 3 hour lesson is dedicated to workshopping. On top of reading the novel to prepare for the lesson, you are expected to have read the pieces people have submitted (online) for the workshop. You take it in turns to submit something - about 3 people go each week. Everyone will read the submitted pieces, and then discuss it in class. People bring up what they liked, what they didn’t like, and hopefully give some constructive criticism.

I cannot speak for what you will get from your second module in term one as they are all different, except that you will get:

- 3 hours taught lesson, once a week. - A reading list- Probable access to musuems/cinemas/relevant study spaces

At the end of term one, you will be expected to submit a 7,000 word assignment of creative prose. It can be whatever you like. The deadline is early January. On top of this, there will be another assignment due for your second module - obviously this will vary depending on what module you choose. I had to submit a 4,000 word essay on Feminism in the French New Wave (cinema).

In Term Two (Jan - May), the modules for Creative Writing are:

- Fiction 2/Poetry 2- Paris: The Residency

You do not get to pick a module in your second term, they are both compulsory. (Sidenote: if you picked Poetry 1 in Term One, then you must pick Poetry 2 in Term Two. You cannot do Poetry and then Fiction or vice versa as far as I know.)

In Fiction 2 you get:

- 3 hours taught class time once a week- A reading list of relevant novels- The same structure is in place as in Fiction 1 with half workshop half lecture, however the teachers will be different and have very different approaches (which is very helpful imo!) I learnt way more in Fiction 2 than Fiction 1 personally, but I’ve had great teachers in my second term.

In Paris: The Residency you get:

- 3 hours taught class time once a week- A reading list of relevant novels- A homework task each week to do so that the following week it can be workshopped. Examples of these homework tasks are ‘follow a stranger for ten minutes - discreetly - watching their mannerisms, gait, etc. and write about who they might be’, or ‘try and lose yourself in the streets of the city, then spend fifteen minutes just writing all that you see and hear’, etc. - This module is supposed to be about ‘city writing’, so they want you to write about Paris, or wherever else you feel drawn to city-wise. - I will be honest with you, I really disliked this class. However, I personally didn’t like it because I came on this course to work on and complete my novel (which Fiction 1 and 2 allowed me to do by submitting different chunks of it each week for workshopping and for the assignments), and it seemed a waste of time to be writing silly things about the city each week when I could have been more productive by working on the novel. The class isn’t poorly taught, it just had no relevance to me. I also don’t really enjoy ‘city writing’ as it seems bland, but that’s just a personal preference! Not enjoying this module did not (really) detract from the overall experience of the course, so it was fine.

At the end of Term Two, you are expected to submit one 7,000 word piece of fiction for Fiction Two, and another 7,000 word piece of fiction (city-themed!) for Paris: The Residency. Ngl, this killed me a little bit, because they’re both due on the same day haha, but I did it! And I did very well, so it is possible.

After this, you start work on your dissertation. For anyone doing (Fiction, not Poetry) Creative Writing, this is a 12,000 word piece of fiction. It can be whatever you want, but you must pick a supervisor to meet with 3 times before the deadline (met with mine today and she was so super lovely i could kiss her) to make sure you’re on the right track.

Other Things About The Course:

- It’s based on a campus that doesn’t belong to Kent University, so we only take up a small section of the building. This doesn’t seem like a big deal, but it does limit us as students as we aren’t permitted to use all of the classrooms and study spaces. It’s a beautiful building, but it’s very old, and in the winter it was very cold. Having no place to study (there are some but very few) can be a bit of a problem especially in those cold months. In the summer I just sit in the courtyard and work which is d i v i n e. So that’s easier.

- It’s pretty small, and pretty far away. So, in Term One, there were maybe 30-35 students across the whole course (not just Creative Writing, I mean everyone from Kent University on the Paris campus). The faculty are lovely, lovely people but there are really only 3 of them actually there full-time (yes, really). I have no complaints about these lovely staff, however it does make one feel a little cut off from the main University at times. Frank (who I can absolutely put you in touch with if you need!) is the person to go to with any issues, and I’ve yet to see him not be able to help someone who needs it whether it’s issues with finance, scheduling, contacting staff or whatever.

- In Term Two (important!), the amount of students studying in Paris DOUBLES in size. This is because Kent also offers a ‘split-site’ MA course in Creative Writing along with a variety of other subjects. Students that opt of the split-site MA spend Term One in Canterbury at the main Kent campus, and Term Two in Paris. This is a tricky thing to get to grips with, mostly because having a bunch of new people try and insert themselves into your established Paris life is tricky to accept. However, we eventually integrated fine, and only a few minor problems occurred. Also, it is important to note that if you were interested in doing the split-site course, there is funding for it if you apply for a Masters Loan. For the solely Paris-based course, there is no funding aside from scholarships.

- French courses are provided (two hours a week, and you are divided up by existing skill into three different classes).