#they took a different approach to that region’s format and they nailed it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Favourite Region and/or starter?

I love all the starter mons but Rowlet is probably my favorite

But Unova is my favorite region, the pokemon designs from it are some of my favorites!

#ask#pokemon#rowlet#pokemon sm#pokemon usum#i love the borb..#peak pokemon design right there#alola is a close second ngl#they took a different approach to that region’s format and they nailed it#shame they flopped with swsh#so much lost potential#the-chocoholic-writer

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Clashing Storm of Shields - Fighting in the Shield Wall (Part 1: Background)

I think I promised @warsofasoiaf a write up on shield wall combat nearly two years ago now but, after several different versions that each took a slightly different approach, I’ve finally nailed down something that works for me.

As my small introduction has become a rather large post, I’ve decided to split the subject into two sections: a section on the background (introduction, recruitment and organisation, equipment) and a section on how the battle actually took place. I’m posting the first section now, and will post the second in a couple of weeks.

Introduction

I.P. Stephenson once wrote that “the single most defining ideological event in Anglo-Saxon warfare came at Marathon in 490 B.C.”. This comment, and all the assumptions that go with it, highlights the single biggest problem people have in understanding combat in the Early Middle Ages. The uncritical application of Classical scholarship to the medieval world, and a failure to up with the current academic consensus, has significantly distorted how many historians think about shield wall combat.

For example, Gareth William suggests in Weapons of the Viking Warrior that the sax was especially useful in a close order, rim-to-boss formation and compares it to the gladius:

Roman legionaries fighting at close quarters were armed not with a long sword, but with a gladius, or short-sword, which was primarily a thrusting weapon, requiring a minimum of space between the individual soldiers in a line.

The problem with this assumption, leaving aside the fact that weapon sized saxes were rare to the point of non-existence in 9th-11th century Scandinavia and that gladius length saxes weren’t particularly common in Anglo-Saxon England either1, is that the famous Roman short sword wasn’t used for thrusting in a close order formation. Instead, it was used for both cutting and thrusting in open order, with each man taking up 4.5-6 feet of space2. It’s not until open order fighting was abandoned completely and the long spatha was universally adopted by the infantry that we hear of the thrust being the preferred method of combat by the Romans3. An assumption, almost certainly based on scholarship from before 2000, has been made about how the Romans fought and how it might be applied to Anglo-Saxon warfare, but no examination of the different context or more recent scholarship has been performed, leading to the wrong conclusion.

(The Bayeux Tapestry)

Similarly, it’s common in historical fiction set in the Early Middle Ages to feature battles that rely very heavily on Victor Davis Hanson’s The Western Way of War4. For example:

We in the front rank had time to thrust once, then we crouched behind our shields and simply shoved at the enemy line while the men in our second rank fought across our heads. The ring of sword blades and clatter of shield-bosses and clashing of spear-shafts was deafening, but remarkably few men died for it is hard to kill in the crush as two locked shield-walls grind against each other. Instead it you cannot pull it back, there is hardly room to draw a sword, and all the time the enemy’s second rank are raining sword, axe and spear blows on helmets and shield-edges. The worst injuries are caused by men thrusting blades beneath the shields and gradually a barrier of crippled men builds at the front to make the slaughter even more difficult. Only when one side pulls back can the other then kill the crippled enemies stranded at the battle’s tide line.

Bernard Cornwell, The Winter King

Other works, such as Giles Kristian’s Blood Eye and Edward Rutherfurd’s The Princes of Ireland, follow the same pattern of a physical collision between the two formations and a shoving match where weapons are almost secondary. This is a core concept of the traditional model of hoplite combat - the literal othismos (”push”) - that has been likened to a rugby scrum since the early 20th century. Ironically enough, VDH is a great pains to emphasize the unique nature of the Greek phalanx due to the hoplite shield, so even without the doubts of A.D. Fraser, Peter Krentz and all the other “Heretics” it would be questionable to apply this method of warfare to the Early Middle Ages5.

When you examine the differences between the two periods, for example the early Anglo-Saxon shields are often no more than 40cm in diameter and featuring spiked or “sugar loaf” bosses6, it becomes clear that the use of Greek warfare to represent 5th and 6th century warfare is incorrect. Similarly, the difference in construction between the aspis and Scandinavian shields of the 9th and 10th centuries, the aspis having thickly reinforced rims while the Scandinavian shields either taper towards the edges or remain very thin (<10mm), should offer a similar caution7.

In spite of the litany of criticisms I’ve just provided, it’s still necessary to refer back to our understanding of Greek and Roman warfare when examining combat in the Early Middle Ages, for two main reasons. Firstly, and most importantly, the sources are much more detailed about how fighting was carried out and were very often written by men who had themselves fought. While authors of the Early Middle Ages were not necessarily unfamiliar with warfare, they were remarkably uninterested in recording much in the way of details and there’s frequently little useful information to be extracted from accounts of battles.

Secondly, a far larger body of work exists on the how of Ancient hand-to-hand combat. While re-enactors of the medieval period are certainly numerous, perhaps even the most numerous of the pre-modern re-enactor, the sheer output of Greek and Roman re-enactors and the scholars who mine them for insights dwarfs that of medieval re-enactors and, on the whole, is more likely to be up to date with the scholarship of the field in general.

My goal here is to make the best possible use of sources on both Ancient and Medieval warfare in order to present a picture that is as close to a plausible reconstruction as I can manage. I don’t mean for this to be authoritative, and my views do in some cases differ from those of some re-enactors or academics, but I do hope you find this post a useful resource in your writing.

(This? This is what not to do.)

Trees of the Spear-Assembly: Who Were the Warriors?

One of the most important things in understanding combat in the Early Middle Ages is knowing who was doing the fighting and why, since this has a big impact on the way in which they fight, and with how much enthusiasm. In particular, the question of whether they were just poor farmers levied en masse or wealthier members of society who had both military obligations and the culture of carrying them out is an important one, as quite often this is used to demonstrate the difference between two sides.

The answer to the question is that, by and large, men who fought were freemen of some standing, if not always considerable landowners, and wealthy by the standards of their people. I emphasize the concept of relative wealth for good reason, and I’ll get into that as we have a look at the basic structure of the “armies” of the period.

Generally speaking, armies of the Early Middle Ages, across almost all of Europe, consisted of two elements: the Household (hirð, hird, comitatus, etc) and the Levy (fyrd, lið, exercitus, etc). I use “levy” here as a shorthand for any force composed of freemen who are not regularly attached to the household of a major landholder, as they were not usually assembled into a single coherent force with 100% unified command, but I do want to note that there would be a significant difference in the unity of an army made up of regional levies and one made up of lið (individual warbands)8.

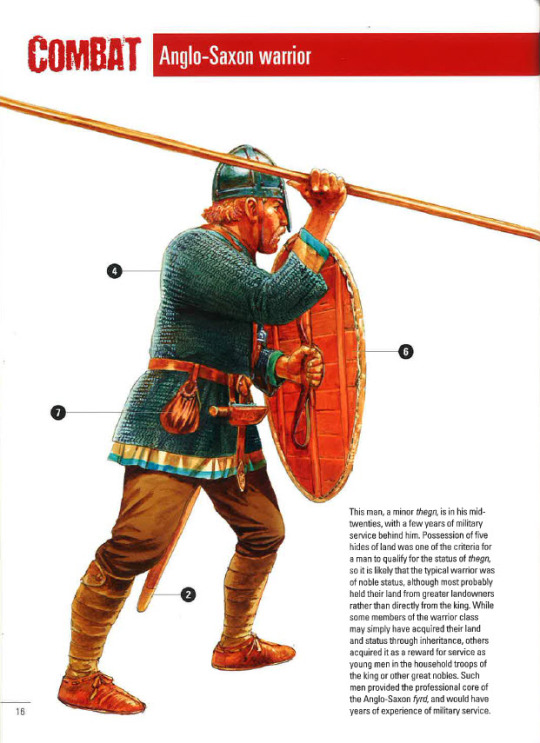

The status of those serving in the household of a powerful landholder could vary significantly, from slaves to the sons of major landholders (although militarised slaves, it must be admitted, were rare outside of the Visigothic realm), and the more powerful the landowner the more likely the men of his household would be themselves descended from someone of considerable status. A significant portion could still be made up of poorer freemen who were sons of older warriors or whose family had some close connection to the major landowner.

For someone who maintained a large household, it was important that they present an image of being a wealthy as possible, and the best way to do this was to outfit the men of their household with every piece of military equipment that displayed status. So, whether he was descended from slaves or was the son of a family who owned a thousand acres, once a man had sworn their oath of loyalty to their new patron, they could be expect to be equipped with all the trappings of a warrior. This might only be symbolic in poorer regions (a fancier sword, a specific type of ornament, etc), especially if the landowner already had a number of armoured retainers, but it bound the different levels of freemen together into a single group.

Generally this oath swearing would occur after a youth had spent several years in the household of their future patron, where they would learn all the necessary skills of a warrior, such as riding, hunting, shooting a bow, using a sword and fighting with spear and shield. These youths probably participated in battles as auxiliaries with bows and javelins and only joined the ranks of the shield wall when they were considered full warriors, but we have only have very limited information on this point.

The status of men of the levy or warband varied to a much smaller degree. They were, in almost all cases, free and relatively wealthy by the standards of their region, although you do see a bit more of a variation in warbands, which might have members from a half dozen regions and many more backgrounds. In comparison, any army raised in defence of a region or raised from a region is going to consist entirely of free men and the majority of these will be fairly wealthy.

Simply put, even basic military equipment was sufficiently expensive that farmers who merely had enough land to sustain their family9 weren’t going to be able to afford much more than an axe, shield and spear or, depending on their region, a bow and 12-24 arrows. This is consistent across the Carolingian, Lombard and Scandinavian world during the 8th-11th centuries and, given the mostly aristocratic nature of warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, was likely true there as well10.

Basic military equipment, however, was not what rulers looked for when summoning forces for external wars or internal defence. We know from the capitularies of Charlemagne that only a man with four estates was required to arm and equip himself for service and that, with one exception, only men with one estate or more were required to pitch in to help equip one of their number for service11. Moreover, these estates weren’t even all the land the freeman held, just the lands he held which had unfree tenants, so that a “poor” freeman who merely had his own personal land was excluded from military service12.

(The average Anglo-Saxon fighting man)

Much the same situation appears in mid-8th century Lombardy, where king Aistulf demanded that those who had 7 or more properties worked by unfree tenants should perform service with a horse and full equipment, while those with less than this, but who own more than 25 acres (40 iugera) of their own, were required to perform an unarmoured cavalry service. 25 acres is about half the land later Anglo-Norman evidence suggests is the minimum for unarmoured cavalry service, so possibly this was an attempt on Aistulf’s part to enfranchise the lesser freemen and get them to support his usurpation of the crown at the political assembly13. Note, however, that the minimum level for cavalry service is nearly double what a peasant family would need to subsist off and implies a man of moderate wealth in and of itself14.

England is somewhat different, as we lack any specific requirements for those being summoned to military service, but from at least 806 we can surmise that 1 man from every 5 hides of land was required for the army. By this point a “hide” wasn’t a measure of area but of value, approximately £1, in a time when 1d. was the wage of a skilled labourer15.

The implications of this aren’t immediately obvious, but when you consider that Wessex had a population of perhaps 450 000 people, across an area of 27 000 taxable hides, only 5400 men (1 man from every 20 families) were actually required for military service16. Many of these, perhaps even most, would have belonged in the retinues of major landholders as either part of their household or as landed warriors owing service to the landholder in exchange for their land. In the same vein, the one man from every hide who was required to maintain bridges and fortifications, as well as defend the burhs (not serve in the field!), was drawn on the basis of something like 1 man for every 4 families. These are heavy responsibilities, but still far from men with sickles and pitchforks making up the fyrd.

There are some exceptions, or else cases where the evidence is thin enough that it’s difficult to say one way or the other, and these typically occur in areas that a less densely populated and less wealthy. The kingdom of Dal Riada in the seventh century, for instance, raised about 3 men from every 2 households for naval duties, although it might also have called out fewer warriors from the general population of the most powerful clan for land warfare17.

(A replica of the Gokstad ship)

Scandinavia is somewhat trickier, since a lot of the sources are late and from a period where central authority existed. We know from archaeological evidence that, in Norway, large scale inland recruitment of men for naval expeditions had been occurring since the Migration Era, as the number of boathouses exceeds the best estimates of local populations18. These were initially clustered around important political and economic centers, but spread out more evenly across Norway during the middle ages as a central political authority arose. This system is likely at least one part of the origin for the leidang system of levying ships, which seems to have properly formed in Norway and Denmark during the late 10th or early 11th century as a result of royal power becoming strong enough to call out local levies across the whole kingdom19.

It seems likely, based on later law codes and other contemporary societies, that Scandinavian raiders during the 8th and 9th centuries were mostly the hird of a wealthy landowner (or their son), supplemented with sons of better off farmers from nearby holdings. Ships were comparatively small at this point, just 26-40 oars (approximately 30-44 men)20, and most had 24-32 oars per ship. This corresponds fairly well with what a prominent landholder might be able to raise from his own household, with additional crews coming from the sons of nearby farmers, although whether this was voluntary, coerced or some combination of the two is impossible to say21.

However, these farmers’ sons, while unlikely to wear mail in the majority of cases, should not be thought of as poor. The vast majority of farmers in 8th-10th century Scandinavia would have had one or two slaves and sufficient land to not only keep their slaves fed and employed, but also to potentially raise more children than later generations22. These farmers’ sons might have been “poor” by the standards of the men they faced in richer areas of the world, but they were rather well off by the standards of their society.

Later, after the end of the 10th century, the leidang was largely controlled by the king of the Scandinavian country and, particularly in the populous and relatively wealthy Denmark, poorer farmers were increasingly sidelined from any obligation to provide military service. Ships also rose in size from the end of the 9th/start of the 10th century, regularly reaching 60 oars for vessels belonging to kings or powerful lords, and even the “average” size seems to have gone from 24-32 oars to 40-50 oars23.

Slaughter Reeds and Flesh Bark: Arms and Armour of the Warrior

The equipment of the warrior consisted of, at its most basic level, a spear and a shield. For those who belonged to a poorer region, a single handed wood axe might serve as a sidearm, or perhaps even just a dagger, while in wealthier regions the sidearm would generally be a sword or a specialised fighting axe24. In an interesting twist, both the poorest and the wealthiest members of society were almost equally likely to use a bow, although I expect that the poorer men mostly used hunting bows, while the professional fighting men used heavier warbows25.

Spearheads, at least from the 7th-11th centuries, were relatively long (blades of >25cm) and heavy (>200g), but most were well tapered for penetrating armour. Some, especially the longest examples, weighed around a pound, but were probably still considered one handed weapons26. Others, however, weighed in excess of two pounds and must have been two handed weapons, possibly the “hewing spear” mentioned in some 13th century sagas27. Javelins, too, appear to have tended to feature long, narrow blades that would have made them a short range weapon, while also providing considerable penetration within their ~40 meter range.

Swords, for their part, were not quite the heavy hacking implement once attributed to them, but also aren’t quite as well balanced as later medieval swords would be. Early swords, before the 9th century, tended to be balanced about halfway down the blade, which might make for a more powerful cut, but didn’t do much for rapid recovery or shifting the blade between covers. However, from the mid-9th century, the balance shifted back towards the hilt, which made them much faster and more maneuverable28. This may indicate a shift towards a looser form of combat, where sword play was more common, or it might indicate nothing more than a stylistic choice. After all, the Celts of the 2nd-1st century BC preferred long, heavy, poorly balanced swords for fighting in spite of relying on the usual Mediterranean “open” style of combat29.

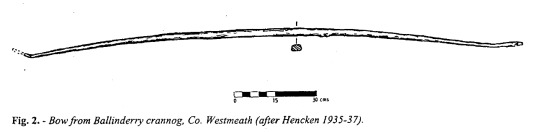

(The Ballinderry Bow)

Warbows, with a couple of exceptions, appear to have been short but powerful. Starting with the Illerup Adal bows, which most likely only had a draw length of 26-27″, we see a repeated pattern when very powerful bows are also much shorter than we expect them to be. In particular, the heavier of the two bows from Illerup Adal is very similar to the Wassenaar Bow, a 9th-10th century bow. A replica of the latter drew 106lbs @ 26″, making it quite a powerful bow, and similar bows have been found at Nydam, Leeuwarden-Heechterp and Aaslum. Only the Ballinderry and Hedeby bows break this trend, with both capable of being drawn to 28″-30″. In all cases, draw weights varied between 80lbs and 150lbs, although 80-100lbs is by far the most common30. The consequence of this is that the power of the bows is not going to be as high as later medieval bows, which were able to be drawn to 30″ and, as the arrows were also relatively light, suggests an energy of 40-60j under most circumstances. This is enough to penetrate mail at close range if using a bodkin arrowhead, but at longer ranges mail would have offered quite excellent protection.

When it comes to shields, there was evidently quite a bit of variation. Early Anglo-Saxon and Merovingian shields were quite small and light, about 40-50cm in diameter31, but later shields were generally 80-90cm in diameter. In particular, we have good evidence of viking shields generally fitting this description, although it’s less clear whether or not later Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon shields retained this diameter or reduced to 50-70cm in diameter (see f.n. 7). In all cases, however, the shield was fairly thin at the center, less than 10mm, and could be as low as 4mm thick at the edge. While thin leather or rawhide could be applied to the front and back of the shield to reinforce it, it’s equally possible that only linen was used to reinforce the shield, or even that the shields were without any reinforcement32.

Recent tests by Rolf F. Warming have shown that this style of shield is rapidly damaged by heavy attacks if used in a passive manner (as in a static shield wall) and that the shield is best used to aggressively defend yourself33. While the test was not entirely accurate to combat in a shield wall (more on this in the second part), it does highlight the relative fragility of early medieval shields compared to other, more heavily constructed shields like the Roman scutum in the Republican and early Empire or the Greek aspis. As I’ve said before, this means we have to rethink how early medieval warfare worked.

Finally, we come to the topic of armour. The dominant form of armour was the mail hauberk - usually resembling a T-shirt in form - and other forms of metal armour were far less common. Guy Halsall has suggested that poorer Merovingian and Carolingian warriors might have used lamellar armour34, and there is some evidence from cemeteries and artwork that Merovingian and Lombard warriors wore lamellar armour in the 6th and 7th centuries, but there’s little evidence to support lamellar beyond this. While it does crop up in Scandinavia twice during the 10th/11th centuries, it was almost certainly an uncommon armour that was used either by Khazar mercenaries or by prominent men who were using it as a status symbol35. Scale armour is right out, Timothy Dawson’s arguments aside, as there is no good evidence of it.

(Helmet from Valsgarde 8)

Helmets evolved throughout the Early Middle Ages, ultimately deriving from late Roman helmets that featured cheek flaps and aventails. During the 6th and 7th centuries, especially in Anglo-Saxon England and Scandinavia, masks were attached to the helmets, either for the whole face or just the eyes. The masks did not long survive the 7th century in Anglo-Saxon England, but the Gjermundbu helmet may suggest it lasted in Scandinavia through to the 10th century. Merovingian helmets of the 6th-8th century tend to be more conical and keep the cheek flaps, but do not have any mask36. Carolingian helmets of the 9th century appear to have been a unique style, more rounded but also coming down further towards the cheeks, and it’s hard to say if this eventually developed in the conical helmet of the late 10th/early 11th century or if it was just a dead end37. Regardless, by the 11th century the conical helmet was the most common form of helmet in England as well as the Continent.

And now for the controversial stuff: non-metallic armour. In short, I don’t think that textile armour was very common during the Early Middle Ages, nor do I think that hardened leather was very common either. The evidence from the High Middle Ages suggests that, unless someone who couldn’t afford to own mail was legally required to own textile armour, they generally didn’t, and we have plenty of quite reliable depictions of infantry serving without any form of body armour38. The shields in use were as much armour as most unarmoured men needed - since, as you’ll recall from the previous section, they rarely fought - and they covered a lot of the body. So far as I’m concerned, there wasn’t a need for it, and plenty of societies through history have fought in close combat without more armour than their shield.

Summing Up

This has been a very basic overview of the background to warfare in the Early Middle Ages, and I know I haven’t covered everything. Hopefully, however, I’ve provided enough background for people to follow along when I dig down into the actual experience of battle in my next post. I’ll cover the basics of scouting, choosing a site to give battle, the religious side of things and then, at long last, the grim face of battle for those standing in the shieldwall.

If you’d like to read more about society and warfare in the Early Middle Ages, then I’d recommend Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian Westand Philip Line's The Vikings and their Enemies: Warfare in Northern Europe, 750-1100, which together cover most of Western and Northern Europe from 400 AD to 1100 AD. While I have some disagreements with both authors, their works have shaped my thoughts over the years since I first acquired them. For the Vikings specifically, Kim Hjardar and Vegard Vike's Vikings at War is excellent, as much for the coverage of campaigns across the world as for the information on weapons and warfare.

Until next time!

- Hergrim

Notes

1 For the rarity of the sax in the viking world, see Vikings at War, by Kim Hjardar and Vegard Vike. For the Anglo-Saxon sax, see the list of finds here. Just 5 out of 33 (15%) had blades 44cm or more and, if you remove those longer than the Pompeii style of gladius (which is the point where some think the Romans changed to purely thrusting style), just two fit the bill.

2 Michael J. Taylor’s “Visual Evidence for Roman Infantry Tactics” is by far the best recent examination of Roman fighting styles, but Polybius has been translated in English for ages. See, however, M.C. Bishop, The Gladius, for an argument that the Romans changed to close order and preferred to rely on thrusting by the end of the 1st century AD.

3 See J. C. Coulston and M.C. Bishop, Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome, for the infantry adoption of the gladius. Any general history of the Roman military will cover the transition from open order to close order during the 3rd century AD.

4 Those of you with a copy of Victor Davis Hanson's The Western Way of War need to perform a quick exorcism. You must burn the book at midnight during the full moon and then divide the ashes into four separate containers, one of gold, one of silver, one of bronze and one of iron. You should then bury ashes from the iron container at a crossroads, scatter the ashes in the bronze container to the wind in four directions, pour the ashes from the silver container into a fast flowing river, and finally feed the ashes from the gold container to a cat, a bat and a rat.

5 A.D. Fraser “The Myth of the Phalanx-Scrimmage” is one of the earliest attacks on the idea of literal othismos. The debate reignited in the 1980s, with Peter Krentz’s “The Nature of Hoplite Battle” leading the charge of the heretics, and the conceptual othismos model is now the accepted version. Hans van Wees’ Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities is probably the best revisionist work to start with. Matthew A. Sears, as attractive as he looks, should be avoided.

6 Early Anglo-Saxon Shields by Tania Dickinson and Heinrich Harke

7 Duncan B. Campbell’s Spartan Warrior 735–331 BC has the most easily accessible information on the best preserved aspis, which is ~10mm thick at the center and 12-18mm thick at the edge, but there’s also a good cross section in Nicholas Sekunda’s Greek Hoplite 480-323 BC. For Viking shields, see this page of archaeological examples by Peter Beatson. Note the similarity to oval shields from Dura Europos in thickness and tapering (Roman Shields by Hilary and John Travis). It’s also worth considering that Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon manuscript miniatures tend to show shields that rarely cover more than should to groin, implying a typical diameter of 50-70cm.

8 See Niels Lund’s “The armies of Swein Forkbeard and Cnut: "leding or lið?”” and Ben Raffield’s “Bands of brothers: a re‐appraisal of the Viking Great Army and its implications for the Scandinavian colonization of England” for an examination of how the lið was constructed, and see Richard Abels’ ‘Alfred the Great, the Micel Hæðn Here and the Viking Threat’, in T. Reuter (ed.), Alfred the Great. Papers from the Eleventh-Centenary Conference for a discussion on the nature of viking “armies”

9 10-15 acres depending on crop rotation and how close to subsistence level you want to peg this category

10 The Scandinavian Gulathing and Frostathing laws were only composed in the late 11th/early 12th century, but it has been argued that they were essentially a codification of earlier oral laws. At least with regards to equipment and service, I see no reason to doubt this.

11 Almost all of the relevant capitularies are translated in Hans Delbruck’s History of the Art of War: The Middle Ages, with the original Latin in an appendix.

12 Walter Goffart has made this incredibly clear in his recent series of loosely related articles: “Frankish Military Duty and the Fate of Roman Taxation,” Early Medieval Europe, 16/2 (2008), 166-90, “ The Recruitment of Freemen into the Carolingian Army, or, How Far May One Argue from Silence?” In J. France, K. DeVries, & C. Rogers (Eds.), Journal of Medieval Military History: Volume XVI (pp. 17-34) and ““Defensio patriae” as a Carolingian Military Obligation”. Although I think Goffart argues too strongly against the dominance and importance of aristocratic retinues in the Carolingian military - the great landowners had the most obligation, after all - he does do a brilliant job of highlighting both the universal requirement of service from eligible freemen and the fact that even a “poor” freeman being assessed for service was, in fact, far better off than most of society. This provides some extra context for the prevalence of swords in Merovingian burials, as note by Guy Halsall: it’s not that swords were cheap, it’s that the average Merovingian warrior was rich by the standards of his society.

13 For the text of the capitulary, see Delbruck. For Aistulf’s possible political motives, see Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West. For Anglo-Norman minimum standards for unarmoured cavalry, see Mark Hagger’s Norman Rule in Normandy, 911–1144.

14 I think it’s worth addressing here the pessimistic low crop yields of older authors and their subsequent conclusion that 25-30 acres would be bare subsistence in the Early Middle Ages. As Jonathan Jarrett has proven (”Outgrowing the Dark Ages: agrarian productivity in Carolingian Europe re-evaluated” Agricultural History Review, Volume 67, Number 1, June 2019, pp. 1-28), these low yields are not supported by the evidence, and we should expect yields to be similar to High Medieval yields. His blog contains an early version of his thoughts on the matter.

15 For a recent exploration of the debate around the Anglo-Saxon military, see Ryan Lavelle’s Alfred’s Wars

16 See Richard Abel’s Alfred the Great for this although n.b. his reliance on old crop yield estimates

17 John Bannerman, Studies in the History of Dalriada. The suggestion that the Cenél nGabráin, being the most powerful clan, might have raised fewer men from the general populace for land combat is my own. They may simply have had the largest number of men in military households and, as such, not needed to rely as much on the general populace when on land. It may also be that calling up larger numbers of the free population for land service from the less powerful clans was in and of itself a method of dominance and control - the largest number of armed men left behind for defence/to suppress revolt would be those from the dominant clan.

18 “Boathouses and naval organization” by Bjørn Myhre in Military Aspects of Scandinavian Society in a European Perspective, AD 1-1300

19 That said, the political control of the Scandinavian kings over military levies should not be overstated - it could be very patchy, even in the 13th century. c.f. Philip Line, The Vikings and their Enemies

20 As suggested by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen in Archaeology and the Sea in Scandinavia and Britain, with the estimate of ~40 oars for the Sutton Hoo ship thrown in as a maximum size. Crew estimates are based on 11th century ships in Anglo-Saxon employ where, based on rates of pay and money raised to pay for the ships, there were only 3-4 men more than the rowers on each ship.

21 c.f. Egil’s Saga and the description of Arinbjorn’s preparation for raiding.

22 The Medieval Demographic System of the Nordic Countries by Ole Jørgen Benedictow. The speculation of larger family sizes is my own, based on other medieval evidence that wealthier families tend to have more children.

23 Ian Heath reproduces the leidang obligations of High Medieval Norway in Armies of the Dark Ages, although he incorrectly applies the two men per oar guideline that only became into being during the 13th and 14th centuries. Archaeological evidence only shows ships of 60+ oars or 26 oars, but from the lengthening of the largest ships and the 40-50 oar ships of the later leidang I feel it is appropriate to assume that the number of oars stayed the same from the 10th to the 14th century, it’s just that the number of rowers doubled as ships became heavier. This is similar to the evolution of the medieval galley.

24 I’ve covered saxes earlier in the notes. For axes, see Hjardar and Vike Vikings at War. Axeheads from western Scandinavia were often over a pound in weight, which is double the weight of specialized Slavic war axes and in the same weight range as the heads of broad axes. Even into the 13th century, these wood axes apparently kept turning up at weapons musters as sidearms.

25 Bows were considered an important aristocratic weapon in Merovingian, Carolingian and Scandinavian societies and, while not a prominent aristocratic weapon, it at least wasn’t shameful for a young English nobleman to use one in battle. The division between “hunting” and “war” bows can be seen in the Nydam Bog finds, where the most powerful bows tend to be relatively short (26-28″ draw length) and the longer bows (28-30″ draw length) tend to be fairly weak. Richard Wadge has demonstrated that civilian bows in medieval England were less powerful than military bows during the 13th century, and I’m applying this to the Nydam bows.

26 Ancient Weapons in Britain, by Logan Thompson

27 See “An Early Medieval Winged/Lugged Spearhead from the Dugo Selo Vicinity in the Light of New Knowledge about this Type of Pole-Mounted Weapon” by Željko Demo, and “An Early-Mediaeval winged spearhead from Fruška Gora” by Aleksandar Sajdl

28 Ancient Weapons in Britain, by Logan Thompson

29 The Celtic Sword, by Radomir Pleiner

30 Most dimensions are from Jürgen Junkmanns’ Pfeil und Bogen: Von der Altsteinzeit bis zum Mittelalter, although the information on the Illerup Adal comes to me from Stuart Gorman. Draw weights are only estimates based on replicas of some bows and a formula found in Adam Karpowicz’s “Ottoman bows – an assessment of draw weight, performance and tactical use” Antiquity, 81(313). Draw weights for yew bows in the real world can vary by as much as 40%, so these estimates are only general guidelines.

31 See f.n. 6 for early Anglo-Saxon shields and Halsall, Warfare and Society, for the early Merovingian shields

32 The shields from Dura Europos, constructed in the same way as Scandinavian shields of the 8th-10th century, feature either very thin leather (described as “parchment”), linen or else some kind of fiber set in a glue matrix. In contrast, two twelfth century kite shields from Pola. d, although constructed only with a single layer of planks like a Viking shield, had no covering at all. See Simon James, The arms and armour from Dura-Europos, Syria : weaponry recovered from the Roman garrison town and the Sassanid siegeworks during the excavations, 1922-37 and “Two Twelfth-Century Kite Shields from Szczecin, Poland” by Keith Dowen, Lech Marek, Sławomir Słowiński, Anna Uciechowska-Gawron & Elżbieta Myśkow, Arms & Armour, 16:2

33 Round Shields and Body Techniques: Experimental Archaeology with a Viking Age Round Shield Reconstruction

34 Halsall, Warfare and Society

35 Thomas Vlasaty has a great article that summarises this subject.

36 No real source for this beyond googling pictures of the various Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian and Merovingian helmets.

37 This Facebook post has some wonderful pictures of the original helmet, a reconstruction of the helmet and comparisons with Carolingian art.

38 eg. the Porta Romana frieze, the porch lunette at the basilica of San Zeno in Verona, the Bury Bible.

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

<<Prev | List | Next>>

Eleven: What You Live By

Lay me down in the bed that I made/ Starved for sleep by the shrill serenade/ Singing over and over/ You will die by what you live by

Two hired hands slowly climbed down out of the back of the wagon, carrying a heavy slab of stone between them. The wagon looked out of place, sitting as it was on the floor of the box canyon. The canyon's walls were high and steep, and bent inwards towards the top, making the space feel like a natural cathedral. The rocks were striated with ancient layers of volcanic tuff and red sandstone, with black streaks like soot that ran perpendicular to the natural rock layers. The canyon floor was all rock and sand, the area devoid of any life.

The wagon was painted in a rich purple and lettered with gold paint, declaring in a fanciful script the name and occupation of its owner. The Spectacular Garmites, it read, Stage Magician, Psychic, Master of Illusions! But there was no magic show happening here; it just so happened that the show wagon was the only one Garmites owned.

"Are you sure you want to return this thing?" The magician asked as he watched the hired help struggle under the weight of the sheet of stone. "I dare say we could get more use out of it than this place could."

"Are you really suggesting we keep a piece of the place that killed me just because you want to have sex on it?" Picketwire asked. She had only blank white expanses for eyes, but Garmites was sure she was glaring at him out of the corner of them.

"Well, when you put it that way…"

"Men," she muttered, and he knew she had returned her gaze to the workers as they approached the canyon wall.

"Hey," he murmured, turning and reaching out to her with his stone arm. He cupped her face, running his thumb over her cheek. "I finally found out that I can touch you after six months of being in love with you. Can you really blame me?"

She closed her eyes and leaned into his touch. Her hand came up and covered his, and he knew she felt the same. Both in that she felt the same longing need to touch him, and that she loved him. They had expressed the mutual feeling after the first time they made love - and immediately fell into each other's' arms to make love multiple times in the same day. Six months of an enforced distance because of their curses, and finally a chance for closeness… it was like a floodgate had opened.

But here she was, willingly getting rid of the one piece of furniture that she could sit or lay on.

Picketwire opened her eyes again, turning her face up to Garmites.

"We'll figure something else out. Better yet, we'll find a way to restore my body so that I can touch all of you."

A chill travelled up his spine at the thought. He had wanted to reverse his own curse for the sake of his life, of course, but now that he had a goal for what to do with his body after he was free from the stone that was replacing his skin, he wanted to find a fix more than ever. Of course Picketwire would only feel the same.

He leaned down to brush his lips against hers, to feel that gentle numbing tingle that he was coming to enjoy, when one of the hired hands called out to him.

Both he and Picketwire let go of one another, straightening and looking ahead.

The closed end of the canyon consisted of a great stone wall covered with paintings and pictographs displaying all sorts of symbols, from animals to people to celestial bodies. Some were so old that they were barely visible, while others were only a hundred or so years old. Chunks of the pictographs were missing, slabs of stone having fallen off or been broken off by archeologists and would-be tomb robbers.

And there, in the center of the wall, stood the thing that had attracted Picketwire to the canyon in the first place. A great stone door carved into the stone, covered with elaborate designs that were outside of the technological capabilities of the tribes native to the region. Unlike the pictographs, it was utterly untouched - except for an opening only a few inches wide.

Picketwire had come closer to opening the crypt than any other attempt - and she had paid dearly for it, the magic protecting the place immediately striking her dead and leaving her soul to wander the desert, alone and cursed.

At least, alone until she found Garmites.

She stepped forward, walking on nothing, floating just above the ground, to join the workers. She looked at the slab - she and Garmites had dismantled the table it was attached to - and studied the patterns painted on its surface. There was the back half of a huge lizard on one of its edges, the image almost a foot long. The slab had been cut into a rectangular shape, so there was no way she could find the exact spot it came from, but with luck, she might find the rest of the pattern.

She stepped back, gazing up at the wall, carefully studying each empty spot where a piece had been broken off.

It took her nearly ten minutes, but she finally spotted the front half of a large lizard. It was on the opposite side of the one on the slab and its legs angled down as opposed to the upward angle the back half. But by tilting her head and thinking, Picketwire figured that the slab simply needed to be turned one hundred and eighty degrees clockwise. She instructed the workers to turn the stone piece over, then guided them to the correct spot.

It took some effort to get the piece into place, as the empty spot was about four feet off the ground, and both Picketwire and Garmites pitched in to lift it up. They group managed to prop it up about where it was supposed to go, like a giant puzzle piece.

Picketwire stood back, looking up at the wall. Then, there was a feeling inside of her. Like something had clicked into place. Like a piece of herself that she didn't even know was missing at been restored.

"Are you alright?" Garmites asked, concerned at the strange look that had come over her face.

Was she alright? She felt somehow slightly more complete, but at the same time she felt a great pull. It was as if someone was trying to drag her towards the crypt's door.

"I have to go inside," she murmured, more to herself than to Garmites.

He looked at the door, furrowing his brow.

"Do you want me to come with you?"

"What?" She had only barely heard him. She felt suddenly like she was underwater. Everything was hard to hear.

"Do you want me to come with you, into that thing?" He repeated.

She thought for a moment. "No. I don't want both of us being killed."

"But you'll try again, despite what happened the first time?"

He had a point, she supposed. And yet…

"I feel like it'll be different this time. Because I'm already dead."

She had kept her eyes on the crack in the door throughout the entire conversation. Garmites caught her by the arm but still she didn't look at him.

"Just be careful," he said.

She nodded, but she hadn't been listening. She pulled her arm away and stepped towards the door. She'd been drifting closer to it without walking since the stone had been put in its place.

She reached the door and placed a hand on the smooth stone surface. When last she had tried to open the crypt, the door had felt like it weighed several tons, and had taken a great deal of force to open even a crack. This time, it yielded instantly to her hand, swinging open like a well-oiled gate.

Inside, the crypt was pitch black. But as she entered, she saw the walls as clear as day. A long, vaulted hallway stretched before her. Every few feet, there was a niche carved into the wall on either side, and in each niche sat matching skulls. The first she passed held small animal skulls; what looked like a bird, a lizard, a rabbit. The animals got bigger in size as she walked forward. A lynx, a coyote, a deer, an elk.

And finally, at the far end of the hallway, two human skulls sat, one on either side of the hall.

Here, the hallway dropped off into a sloping pathway with a much lower ceiling. The pathway was narrow, enough to make her feel claustrophobic, despite her work usually taking her into small burial chambers. Still, she headed down, down into the depths of the crypt. The pathway snaked along with many sharp turns, and then finally opened back up.

The burial chamber of the crypt was a gigantic room, no doubt a natural cave that had been shaped by workers into a smooth-walled chamber. In the center of the room sat a huge stone sarcophagus. Picketwire approached it, to find that it had been carved out of a rock formation native to the room itself, as it was attached to the floor with no sign of nails or adhesive.

The lid of the sarcophagus had been opened slightly. Picketwire grasped the heavy stone and pushed it aside without any hesitation.

The sarcophagus was empty, save for a fine coating of dust. Frustrated, Picketwire stepped back and looked at her surroundings. The walls, she saw, were decorated with paintings of a style far different from the pictographs outside. These images were more realistic and more delicate, depicting life scenes of some ancient civilization. She spotted what looked like pictures of people farming, of people writing, of people playing instruments.

But all of this was overshadowed by a massive painting in the center of one wall that stretched from floor to ceiling. It was an image of a feminine figure with six arms. Each one of her hands held a sword. On the top of her head were huge sickle-shaped horns.

A name came unbidden into Picketwire's mind.

Nelan.

* * *

"Her name is Nelan," Castlerock said over the discussion.

All eyes turned to him. RedRock stopped what he had been saying, which had been a rundown of the creatures of myth he knew about, none of which had matched the description of the thing that had attacked Glyph.

"What?" Magdalena asked, breaking the confused silence.

"The creature in the dust. Her name is Nelan."

"How do you know that?" RedRock asked. He did not hide the slight annoyance he felt at being talked over when he was, in fact, the most well-versed in the tribe's history.

"The spirits told me. They say she is also a spirit, but one far older than any of them. She is a patron of dust, and of battle."

"Your spirits -- do they know what she wants?" Magdalena asked. Her tone was urgent; unlike the rest of the tribe, she had been around to see Elyakim's angels. She had watched as the monsters had decimated the village on the plains, had seen her husband die at their hands. She had watched as they almost killed the Rockbreaker cult. She alone of the tribe knew the dangers that came from the magic that touched the region.

"They said she was put to sleep long, long ago -- before the history of any of the current tribes of the region began. She was trapped, because she was such a danger to the peoples living her. Something must have awoken her."

"But what does she want, Castlerock?"

The shaman paused, closing his eyes. He seemed to be listening to something that no one else in the room could hear - which he was.

"It's hard to say. They keep talking over each other -- I think they're afraid of her. But," he opened his eyes, "the one thing they've all said is that if we cannot defeat her in battle, we're all dead."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is South Street's retail apocalypse coming to an end?

A downturn decades in the making

The boom-bust business cycle may point to a coming revitalization for the eastern blocks of South Street, but the corridor has a particularly persistent hole to dig out of. For several years, business owners and the local business improvement district have been trying to bring more customers to the street with mixed results, even as the national economy has improved and shopping districts in Center City have experienced a boom.

That’s partly a legacy of South Street’s previous renaissance in the 1970s, which began after older businesses fled to make way for a proposed expressway that was later called off. Cheap rent attracted artists’ galleries, rock clubs, and cafes, run and patronized by young people. Steinberg, who lived in Queen Village in the 1980s, said the youth-centered business model enlivened the corridor, but it didn’t support retail stability and resulted in an “incredible amount of turnover.”

The youthful crowds also caused a major image problem when some 50,000 revelers descended on the street for Mardi Gras in February 2001, leading to riots that made national news. They smashed windows, looted a dozen stores, and threw bottles at police, resulting in 100 arrests and a clampdown on Fat Tuesday celebrations in the years since. “That cast a negative shadow on South Street,” Steinberg said. “That doesn’t happen anymore.”

During the recession, scores of businesses closed and were not replaced for years, prompting some landlords to donate their storefronts to arts organizations for use as low-cost galleries and art studios. Anchor stores like Gap, Tower Records and Blockbuster shut down. The rise of online shopping took a toll. Meanwhile, shoppers began discovering other cool places to spend their time and money.

The variety of alternatives is something the street has “wrestled with over the years and still wrestles with,” said Michael Harris, executive director of the South Street Headhouse District business association. “Frankly, South Street used to be the only game in town, in the 80s and 90s. But the heat map moves, the areas of popularity move, so now you have Fishtown and North Liberties and East Passyunk.”

While the internet and changing shopping habits have challenged retailers everywhere, Center City’s retail market is booming. Some 2 million square feet of new retail space is in development from Vine to South streets, according to a 2017 report from Center City District, “expanding Philadelphia’s prime retail district and reactivating long-dormant downtown shopping streets.”

On Walnut and Chestnut streets west of Broad, the retail vacancy rate dropped below 5 percent last year, CCD said. The vacancy rate citywide hovered around 8 percent as of mid-2018, according to Collier’s International. Meanwhile, South Street struggles with a vacancy rate of 16 percent, nearly twice the citywide average, Harris said.

The loss of businesses on South Street is reflected in stagnant retail rents. Storefronts there rent for about $40 per square foot, well below the amounts charged in the core of Center City, according to a report by the real estate firm CBRE. That figure is almost unchanged from 13 years ago, while asking rates on Chestnut, Walnut and Market streets have risen steadily since then.

Yet with so many buildings vacant, rents should arguably be even lower. Landlords’ unwillingness to accept less profitable lease arrangements may explain why some spots remain empty for months or even years. A similar phenomenon is occurring in parts of Manhattan, where landlords are reluctant to lower rates despite a supposed retail apocalypse driven by online competition.

“There are people still expecting to get rents much higher than I think the street can support, so they’re holding out and holding properties vacant against the dream that has probably changed as retail is facing ever more pressure from the internet,” said Paul Levy, CCD’s chief executive and a resident of nearby Society Hill. “A lot of the property owners have made decisions to wait for certain types of tenants who may not be coming.”

South Street’s future may depend on embracing the model of the neighborhood main street. Levy, Harris, and the brokers agree that the best bet for the long-time tourist attraction may be catering to the affluent residents who have moved in over the last few decades.

“You’ve got incredibly strong market demand on either side of the street, from Society Hill and Queen Village, from Washington Square and from Bella Vista. This is not like a marginal commercial corridor struggling for businesses,” Levy said.

That would mean accelerating the street’s shift from its youth-oriented focus of the 1980s and 1990s, which depended on weekend visitors from around the region, to a balanced model that brings in more local shoppers on weekdays.

“Part of our challenge, and part of our opportunity, is that we have to service both the neighborhood and tourists,” Harris said. A recent survey of people on the street found visitors from 20 different states, he said. “We are a tourist destination and we want that to be a good experience for people, but at the same time we want to be serving all the neighbors that live around here, which are lots of families, and lots of people with disposable income. It’s kind of finding that balance of things that work for both. If you can get the right mix, both sets of consumers will be happy.”

An indication of what that could look like can be found right off South Street, on 4th Street’s Fabric Row, where boutiques, salons, cafes and restaurants like Hungry Pigeon thrive off a steady stream of local customers. One popular boutique, Moon + Arrow recently opened an offshoot shop, Little Moon + Arrow, catering to the organic-onesie-wearing, wooden-toy-playing children of their customers.

Nearby residents are particularly eager to see a grocery store fill the long-vacant storefronts of Abbotts Square. Ahold Delhaize, the Dutch company that owns Giant and other supermarket chains, reportedly leased space in the building in 2016 to open a smaller-sized, higher-end market, but the owner has encountered difficulties that have slowed redevelopment of the complex.

Harris and Steinberg said Ahold recently announced that the 16,000-square-foot market is coming soon. A spokeswoman for Giant Food Stores would not confirm a date or address for a new South Street store, but she said the company is planning to announce several new locations in Philadelphia in the coming months. A Giant Heirloom Market is set to open in December at 24th and Bainbridge, close to South Street West in Graduate Hospital.

The South Street Headhouse District already has Whole Foods and ACME at 10th Street, as well as Essene natural foods and two small markets on 4th Street. There’s also a small ACME on 5th Street in Society Hill.

Another prospective anchor business is the small-format Target proposed for 5th and Bainbridge, where buildings have already been demolished in preparation for construction of the store, a parking garage and apartments. Steinberg said a “highly regarded” national fast-food chain is also working on a deal to open a restaurant on South Street.

“That’s the kind of happening that gives us hope,” he said. “What we’re hoping happens is there are some stabilizing-type tenants that are looking [to occupy space] on the street, that may not have the funky panache that some of the other retailers have had on South Street, but add national stability, which make it a safer destination for retailers and adds more interest.”

Apart from individual anchor stores, what South Street needs are developers who gain control of several properties that are close to each other and pursue visions for cohesive, attractive shopping areas, Levy and Weiss said. Similar approaches worked well for East Passyunk, Frankford Avenue in Fishtown, and 13th Street in the Gayborhood, among other areas, they said.

To that end, Weiss’s firm is working on transactions with large investors who would acquire a whole portfolio of properties at once, he said.

“It will take some time to turn around,” he said. “It’s not going to be one landlord at a time. It will be larger, well-capitalized landlords who have a vision and patience to execute that vision, not to open another hookah shop.”

A promising development along those lines was the sale of several properties owned by New York developer Michael Axelrod to Midwood Investment & Development in 2016. Axelrod has reportedly owned more than 40 South Street buildings and kept many vacant for years, apparently holding out for high-profile tenants willing to pay higher rents. Since the sale, Midwood has started filling the spaces, including a former McDonald’s that was vacant for a decade but recently reopened as a nail salon.

“There are a lot of property owners who are willing and interested in negotiating [with prospective tenants],” Harris said. “There's no magic wand that suddenly cures it all, and the needle doesn't move as fast as I want, but I think there are a tremendous number of great restaurants and great retail down here that we want to remind people of.”

Source: http://planphilly.com/articles/2018/11/20/is-south-street-s-retail-apocalypse-coming-to-an-end

0 notes

Text

Is South Street's retail apocalypse coming to an end?

A downturn decades in the making

The boom-bust business cycle may point to a coming revitalization for the eastern blocks of South Street, but the corridor has a particularly persistent hole to dig out of. For several years, business owners and the local business improvement district have been trying to bring more customers to the street with mixed results, even as the national economy has improved and shopping districts in Center City have experienced a boom.

That’s partly a legacy of South Street’s previous renaissance in the 1970s, which began after older businesses fled to make way for a proposed expressway that was later called off. Cheap rent attracted artists’ galleries, rock clubs, and cafes, run and patronized by young people. Steinberg, who lived in Queen Village in the 1980s, said the youth-centered business model enlivened the corridor, but it didn’t support retail stability and resulted in an “incredible amount of turnover.”

The youthful crowds also caused a major image problem when some 50,000 revelers descended on the street for Mardi Gras in February 2001, leading to riots that made national news. They smashed windows, looted a dozen stores, and threw bottles at police, resulting in 100 arrests and a clampdown on Fat Tuesday celebrations in the years since. “That cast a negative shadow on South Street,” Steinberg said. “That doesn’t happen anymore.”

During the recession, scores of businesses closed and were not replaced for years, prompting some landlords to donate their storefronts to arts organizations for use as low-cost galleries and art studios. Anchor stores like Gap, Tower Records and Blockbuster shut down. The rise of online shopping took a toll. Meanwhile, shoppers began discovering other cool places to spend their time and money.

The variety of alternatives is something the street has “wrestled with over the years and still wrestles with,” said Michael Harris, executive director of the South Street Headhouse District business association. “Frankly, South Street used to be the only game in town, in the 80s and 90s. But the heat map moves, the areas of popularity move, so now you have Fishtown and North Liberties and East Passyunk.”

While the internet and changing shopping habits have challenged retailers everywhere, Center City’s retail market is booming. Some 2 million square feet of new retail space is in development from Vine to South streets, according to a 2017 report from Center City District, “expanding Philadelphia’s prime retail district and reactivating long-dormant downtown shopping streets.”

On Walnut and Chestnut streets west of Broad, the retail vacancy rate dropped below 5 percent last year, CCD said. The vacancy rate citywide hovered around 8 percent as of mid-2018, according to Collier’s International. Meanwhile, South Street struggles with a vacancy rate of 16 percent, nearly twice the citywide average, Harris said.

The loss of businesses on South Street is reflected in stagnant retail rents. Storefronts there rent for about $40 per square foot, well below the amounts charged in the core of Center City, according to a report by the real estate firm CBRE. That figure is almost unchanged from 13 years ago, while asking rates on Chestnut, Walnut and Market streets have risen steadily since then.

Yet with so many buildings vacant, rents should arguably be even lower. Landlords’ unwillingness to accept less profitable lease arrangements may explain why some spots remain empty for months or even years. A similar phenomenon is occurring in parts of Manhattan, where landlords are reluctant to lower rates despite a supposed retail apocalypse driven by online competition.

“There are people still expecting to get rents much higher than I think the street can support, so they’re holding out and holding properties vacant against the dream that has probably changed as retail is facing ever more pressure from the internet,” said Paul Levy, CCD’s chief executive and a resident of nearby Society Hill. “A lot of the property owners have made decisions to wait for certain types of tenants who may not be coming.”

South Street’s future may depend on embracing the model of the neighborhood main street. Levy, Harris, and the brokers agree that the best bet for the long-time tourist attraction may be catering to the affluent residents who have moved in over the last few decades.

“You’ve got incredibly strong market demand on either side of the street, from Society Hill and Queen Village, from Washington Square and from Bella Vista. This is not like a marginal commercial corridor struggling for businesses,” Levy said.

That would mean accelerating the street’s shift from its youth-oriented focus of the 1980s and 1990s, which depended on weekend visitors from around the region, to a balanced model that brings in more local shoppers on weekdays.

“Part of our challenge, and part of our opportunity, is that we have to service both the neighborhood and tourists,” Harris said. A recent survey of people on the street found visitors from 20 different states, he said. “We are a tourist destination and we want that to be a good experience for people, but at the same time we want to be serving all the neighbors that live around here, which are lots of families, and lots of people with disposable income. It’s kind of finding that balance of things that work for both. If you can get the right mix, both sets of consumers will be happy.”

An indication of what that could look like can be found right off South Street, on 4th Street’s Fabric Row, where boutiques, salons, cafes and restaurants like Hungry Pigeon thrive off a steady stream of local customers. One popular boutique, Moon + Arrow recently opened an offshoot shop, Little Moon + Arrow, catering to the organic-onesie-wearing, wooden-toy-playing children of their customers.

Nearby residents are particularly eager to see a grocery store fill the long-vacant storefronts of Abbotts Square. Ahold Delhaize, the Dutch company that owns Giant and other supermarket chains, reportedly leased space in the building in 2016 to open a smaller-sized, higher-end market, but the owner has encountered difficulties that have slowed redevelopment of the complex.

Harris and Steinberg said Ahold recently announced that the 16,000-square-foot market is coming soon. A spokeswoman for Giant Food Stores would not confirm a date or address for a new South Street store, but she said the company is planning to announce several new locations in Philadelphia in the coming months. A Giant Heirloom Market is set to open in December at 24th and Bainbridge, close to South Street West in Graduate Hospital.

The South Street Headhouse District already has Whole Foods and ACME at 10th Street, as well as Essene natural foods and two small markets on 4th Street. There’s also a small ACME on 5th Street in Society Hill.

Another prospective anchor business is the small-format Target proposed for 5th and Bainbridge, where buildings have already been demolished in preparation for construction of the store, a parking garage and apartments. Steinberg said a “highly regarded” national fast-food chain is also working on a deal to open a restaurant on South Street.

“That’s the kind of happening that gives us hope,” he said. “What we’re hoping happens is there are some stabilizing-type tenants that are looking [to occupy space] on the street, that may not have the funky panache that some of the other retailers have had on South Street, but add national stability, which make it a safer destination for retailers and adds more interest.”

Apart from individual anchor stores, what South Street needs are developers who gain control of several properties that are close to each other and pursue visions for cohesive, attractive shopping areas, Levy and Weiss said. Similar approaches worked well for East Passyunk, Frankford Avenue in Fishtown, and 13th Street in the Gayborhood, among other areas, they said.

To that end, Weiss’s firm is working on transactions with large investors who would acquire a whole portfolio of properties at once, he said.

“It will take some time to turn around,” he said. “It’s not going to be one landlord at a time. It will be larger, well-capitalized landlords who have a vision and patience to execute that vision, not to open another hookah shop.”

A promising development along those lines was the sale of several properties owned by New York developer Michael Axelrod to Midwood Investment & Development in 2016. Axelrod has reportedly owned more than 40 South Street buildings and kept many vacant for years, apparently holding out for high-profile tenants willing to pay higher rents. Since the sale, Midwood has started filling the spaces, including a former McDonald’s that was vacant for a decade but recently reopened as a nail salon.

“There are a lot of property owners who are willing and interested in negotiating [with prospective tenants],” Harris said. “There's no magic wand that suddenly cures it all, and the needle doesn't move as fast as I want, but I think there are a tremendous number of great restaurants and great retail down here that we want to remind people of.”

Source: http://planphilly.com/articles/2018/11/20/is-south-street-s-retail-apocalypse-coming-to-an-end

0 notes

Text

Retrospective view on 2018/2019 DPC season in Dota 2

New Post has been published on https://www.ultragamerz.com/retrospective-view-on-2018-2019-dpc-season-in-dota-2/

Retrospective view on 2018/2019 DPC season in Dota 2

Retrospective view on 2018/2019 DPC season in Dota 2

At the late night on 14 July, the qualifier for the main tournament of the year The International 2019 ended up. The second DPC season got over along with the qualifiers. This year gave us many interesting matches, tournaments, results and events which are connected with Dota 2 and its community.

So, what has 2018-2019 season presented to us?

Majors become significant again

Unlike 2017/2018 season, the second DPC season, Valve has dramatically reduced the number of tournaments. Instead of 22 premium tournaments, the community got 5 minors and 5 majors. On the one hand, it seems to be a minus, as the more Dota we have, the better it is.

In fact, this decision is right for the competitive Dota stage. Dota remains the same, but the rules have changed. Key differences of 2018-2019 season from 2017/2018 season:

Importance of majors. Even though the number of championships has reduced, their importance has increased. At the second season of the DPC system a win at a major provided teams with getting to TI which surely was a great motivation for teams during the whole year. Majors again were considered to be important tournaments which guaranteed a trip to TI;

Absence of oversaturation. In 2017, there was too much Dota. Tournaments took place almost one after another. Breaks lasted for 7-9 days. Even if everybody liked this format at the beginning, in the middle of the season it got obvious that fans and spectators got tired of Dota. In 2018, Valve returned to the previous format with five majors in a season. And the community liked it;

Number of direct invitations has increased. Even if there are less tournaments, the number of directly invited teams has increased. Instead of 8 invitations, 12 were played for.

These distinctive features are remembered about the DPC season if we take a look at the format. But apart from numbers and the amount of tournaments, this year has become significant due to other numerous events.

Results of the qualifiers for The international 2019

To sum up the whole season, it will be silly not to mention the main qualifiers of the year. Six trips to Shanghai were played for at the qualifiers in 2019. Due to the fact that twelve teams got to TI9 instead of eight, there was no competition at some regions. Chaos became the winners in Europe as it had been expected, in South America – Infamous, and in North America – Forward Gaming. The Chinese region is the most competitive and strong if we talk about the level of the game. At the intense battle NG managed to win over CDEC by the score of 3-2. South Asia disappointed everybody with their level of teams and performers. Mineski managed to defeat the stack from Jinesbrus on last breath. The most interesting for CIS citizens was a classic CIS knockdown-dragout fight.

Slaughter at the CIS qualifiers or value of a ragequit

Unlike the previous year, the qualifiers in 2019 got different due to brightness of game and unexpected results. First of all, the biggest disappointment is five players from Gambit Esports. The brightest favorite of the CIS qualifiers, the team that showed a high level during the year, didn’t make it to the playoff stage of the closed qualifiers in the CIS. The reason is disagreement and misunderstandings between the players. A key moment which stated the beginning of the end was an unexpected leave of Afoninje after the death at a very important match against Winstrike. Iceberg and the teams closed the casket door while the sharks from Vega Squadron knocked a nail in it. As a result – 3-4 place and the work done during the year which turned out to be in vain.

On the other hand – Natus Vincere. The legendary tag, the most successful team at TI, that come back to The International after two long years. As well as Gambit, Born approached the qualifiers as favorites. But the majority believed in the win of Gambit while Na’Vi were thought to get to the final only. The five yellow-black players managed to show their characters and to win the CIS qualifiers, coming back to the list of eighteen best teams in the world. Also we should not forget that The Alliance who are arch-enemies of Born to Win also made it to the International. This match can become the most epic and awaited battle at the upcoming TI along with the final of the tournament.

Thorny path to the stars or how the teams passed to The International 2019

The main goal of the season was to define and to choose the best teams for participation in the main event of the year. And if Team Secret, ViCi and Virtus.pro got to the event expectedly, the other teams had a more difficult path:

EG. Evil Geniuses’ visiting card is their stability. Having played well at the majority of majors of the season, the team provided themselves with getting to the TI;

PSG.LGD. Even though the season was not as successful as the previous one for the Chinese team, it is still one of the biggest pretenders to the victory at the upcoming TI;

Liquid. The team have been having a decline during the season, but still they managed to get back on their feet till the end and taking two second places at the last majors, the players got to TI directly;

OG. The team that became the champion last year didn’t have the best times at the beginning of the year. After Anal, the main star of the roster, returned to the European team, OG started to play at the previous level and managed to gain a direct invitation to the TI;

NiP. The team PPD deserved a direct invitation to The International thanks to wins at minors and rather good places at majors;

Fnatic. Although this year wasn’t the brightest for Iceiceice and the team, they were able to qualify for TI;

TNC Predator. Having signed Heen as a coach in April, the team improved their game. Having taken two 4 places at majors, Armal and the team provided themselves with getting to TI;

Alliance. The champions of the third TI come back to the main tournament of the year. Placing premium on the young roster and experienced coach Loda, the Swedish managed to perform well at the second half of the year and kicking Gambit out, the team provided themselves with a direct invitation to the International;

Keen Gaming. The players from Keen Gaming complete the list of the teams who got to the event directly. Rather low results during the year let them get through the minimal border of points, getting the 12 place in the rating and a direct invitation to TI

That was the path of the teams to the main tournament in Shanghai. It is remarkable that at the home tournament only four Chinese teams out of 18 will play at while Europe dominates this year – 6 representatives at TI, rather considerable number. Besides, 2018/2019 season was full of scandals and curious events

Scandals of the second DPC season

As well as in any other kind of sports, Dota has unpleasant precedents. The second competitive season was not an exception. We can make several highlights among the most scandalous and unpleasant events:

Inappropriate statements of KuKu and consequently his ban to participate in the Major in Chongqing;

Scandal where the champion of TI took part, Ceb and his inappropriate statements in public;

Unexpected kick of MATUMBAMAN from Team Liquid;

Loss of Gambit at the closed qualifiers for The International;

Lil and his constant search of «family»;

Dendi leaving Na’Vi

Conclusion

This is what is remembered about a regular Dota season in 2018-2019. But this is not the end, the most important is ahead.

Preludes are finished, participants are known, The International 2019 is close. Can they satisfy the hopes of their fans and win at the home stadium or will an even year bring another championship to the West? We will get to know the answers to these questions pretty soon.

Tags:

DPC season in Dota 2

0 notes

Text

Is South Street's retail apocalypse coming to an end?

A downturn decades in the making

The boom-bust business cycle may point to a coming revitalization for the eastern blocks of South Street, but the corridor has a particularly persistent hole to dig out of. For several years, business owners and the local business improvement district have been trying to bring more customers to the street with mixed results, even as the national economy has improved and shopping districts in Center City have experienced a boom.

That’s partly a legacy of South Street’s previous renaissance in the 1970s, which began after older businesses fled to make way for a proposed expressway that was later called off. Cheap rent attracted artists’ galleries, rock clubs, and cafes, run and patronized by young people. Steinberg, who lived in Queen Village in the 1980s, said the youth-centered business model enlivened the corridor, but it didn’t support retail stability and resulted in an “incredible amount of turnover.”

The youthful crowds also caused a major image problem when some 50,000 revelers descended on the street for Mardi Gras in February 2001, leading to riots that made national news. They smashed windows, looted a dozen stores, and threw bottles at police, resulting in 100 arrests and a clampdown on Fat Tuesday celebrations in the years since. “That cast a negative shadow on South Street,” Steinberg said. “That doesn’t happen anymore.”

During the recession, scores of businesses closed and were not replaced for years, prompting some landlords to donate their storefronts to arts organizations for use as low-cost galleries and art studios. Anchor stores like Gap, Tower Records and Blockbuster shut down. The rise of online shopping took a toll. Meanwhile, shoppers began discovering other cool places to spend their time and money.

The variety of alternatives is something the street has “wrestled with over the years and still wrestles with,” said Michael Harris, executive director of the South Street Headhouse District business association. “Frankly, South Street used to be the only game in town, in the 80s and 90s. But the heat map moves, the areas of popularity move, so now you have Fishtown and North Liberties and East Passyunk.”

While the internet and changing shopping habits have challenged retailers everywhere, Center City’s retail market is booming. Some 2 million square feet of new retail space is in development from Vine to South streets, according to a 2017 report from Center City District, “expanding Philadelphia’s prime retail district and reactivating long-dormant downtown shopping streets.”

On Walnut and Chestnut streets west of Broad, the retail vacancy rate dropped below 5 percent last year, CCD said. The vacancy rate citywide hovered around 8 percent as of mid-2018, according to Collier’s International. Meanwhile, South Street struggles with a vacancy rate of 16 percent, nearly twice the citywide average, Harris said.

The loss of businesses on South Street is reflected in stagnant retail rents. Storefronts there rent for about $40 per square foot, well below the amounts charged in the core of Center City, according to a report by the real estate firm CBRE. That figure is almost unchanged from 13 years ago, while asking rates on Chestnut, Walnut and Market streets have risen steadily since then.