#there’s no way they make cutscenes for video games on film reels

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

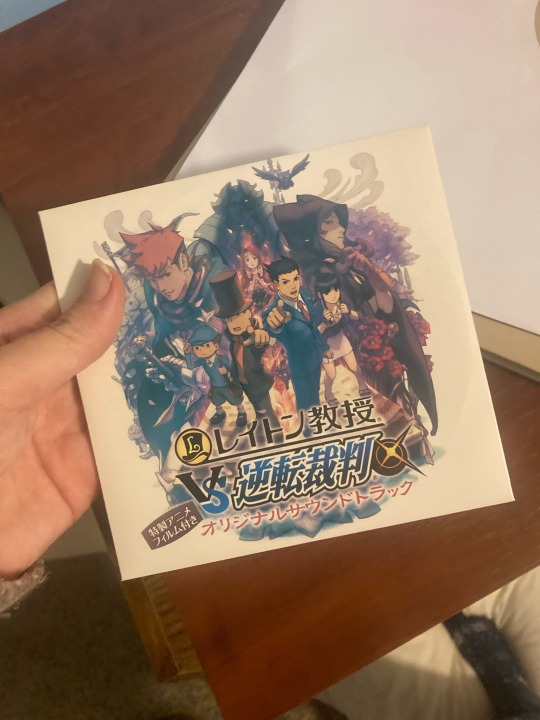

So for my birthday, one of my best friends got me this.

As I understand it, it was a pre-order bonus for the crossover game and had five tracks from the soundtrack and also came with a snippet of film from a cutscene that was made but then cut or something? My friend wasn’t very clear.

Here’s a better look at my snippet. Anyone have any ideas what it might have been of?

#professor layton vs phoenix wright#PLvPW spoilers#I mean probably not but just to be safe#and yes I have the most amazing friends in the world and no I do not deserve them#but they are still mine and you can’t have them#it looks kind of like fire? maybe the fire that destroyed the town the night of the festival?#but that cutscene wasn’t cut was itv#is this even cut or#there’s no way they make cutscenes for video games on film reels#c’mo#what the hell is this#queue takumi defense squad

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resident Evil 2 reflections

One crisp winter evening in early 1998, my friend “Kyle” sat me down on the floor of his room, which was twice the size of my room, and fired up his Sony PlayStation. “You aren’t going to believe this,” he said.

He’d said that a lot over the past several months, usually in regards to something happening on the Sony PlayStation, and usually he was right. He’d shown me Resident Evilfirst, always calling it “Res Eve,” and it had shaken my very idea of what a video game was. Real actors? Real voices? Real emotions? Indeed I could not believe that something as juvenile and recreational as a video game had actually scared me. But the efficacy of that first zombie head-turn was undeniable.

In the following months Kyle had shown me a Top Gun game with live-action cutscenes featuring the bald principal from Back to the Future; the original Dynasty Warriors, which was a 3D fighting game; Mortal Kombat Trilogy; and the Sephiroth fight from Final Fantasy VII where he destroys the entire solar system as a canned attack animation. It’s amusing in hindsight that these titles could ever have been lumped together in any capacity, but each of them was such a fundamental upset of my existing notion of video games* that it was initially impossible for me to discern any gradient in quality. With the exception of the live-action bits, I couldn’t even discern FMVs from in-game cutscenes, because neither concept had existed in my head at all. It was like if you’d gone back in time to the dawn of the industrial age and shown someone The Godfather and an episode of Married with Children back-to-back. However briefly, there’d be a moment where their reaction would be roughly the same to each: “THE PICTURES ARE MOVING AND TALKING.”

*Okay, MK Trilogy didn't exactly break new ground, but it made me realize my kopy of Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3 on the Genesis wasn't very ultimate at all.

↑↓ Keep in mind I saw these two things on the same day, prior to which the most visually impressive thing I'd ever seen a game do was accurately render comic strip characters (Garfield: Caught in the Act, I'm looking at you).

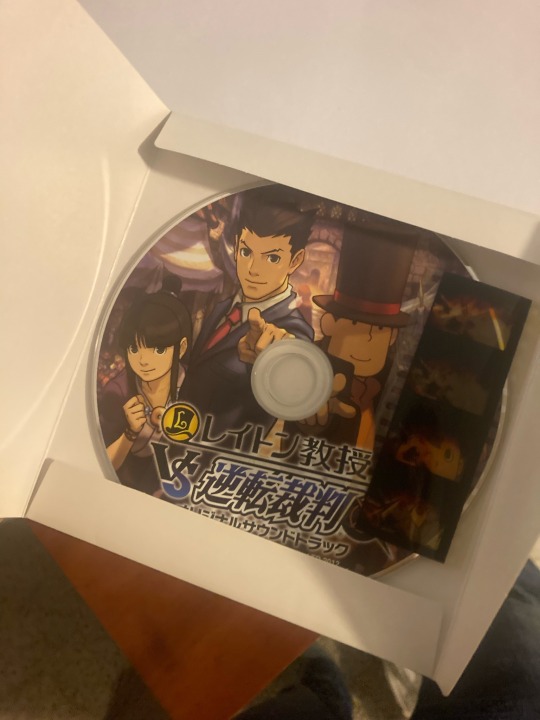

On this crisp, winter evening in 1998, Kyle showed me Resident Evil 2, which had only just released. We sat and watched the Leon intro in silence. There’s a very special stillness, an eerie electricity to the original RE2 intros that reminds me of the ominous feeling of the air and the sky before a big thunderstorm. It’s the same feeling I get when I watch the closing moments of the Who Shot Mr. Burns? Episode of The Simpsons, that sparse tension that is equal parts quieting and disquieting.

I watched, transfixed. Finally, the game relinquished control to Kyle, and he ran through a fiery city street teeming with zombies. Their numbers seemed to fill every shot. Everything was wrecked and burning and overrun, a fruition of the thing the first Resident Evil only hinted at while locking you inside that mansion.

Kyle ducked into an apparent safehouse and was immediately—seamlessly!—halted by a suspicious shopkeep with a shotgun. A dramatic, fully voiced conversation ensued, the shopkeep backed off, and Kyle was given freedom to explore the room until suddenly—seamlessly!—the horde crashed through the false security of the shop’s window glass and ate the screaming shopkeep alive, blood fountaining from his red-stained neck and torso. You know the rest.

I walked home for dinner at dusk, looking back over my shoulder every few feet, and marveled that a video game could generate such real-life fear.

I got my own Sony PlayStation about half a year later and devoured both RE2campaigns within three days. By the end I was as much a survivor as a player, and didn’t entirely know how to reconcile the good time I’d had with the immense feeling of relief that it was over. To survive a prolonged immersion in terror is an emotionally complicated experience, and not one I’d been accustomed to associating with “play.” It struck me how much scarier RE2 was than even RE1. RE1 put danger in the obvious place—a big, creepy mansion; in RE2, the evil had spilled out into the streets and overrun society’s most guarded spaces—a gun shop, a police station. The voice acting, graphics, and environmental design were also significantly better than before. The point is that Resident Evil 2 was a special game, in large part because it did things early, but also because it did things well. It was the sweet spot of the original RE trilogy—it did things better than RE1, at a riper time than RE3.

I might’ve thought any attempt to recapture that magic would be futile, had Capcom not already proven the potential for such a thing in 2002 with the GameCube remake of the original Resident Evil, which was where much of the demand for an RE2 remake came from in the first place. The RE1 remake had very cleverly used the players’ nostalgia against them, subverting our expectations in all the most notorious moments. It also made modest but smart improvements to the game’s systems and drastic improvements to its audiovisual elements, and threw in a few meatier surprises. Basically it succeeded in an impossible aim: to make fans feel like they were replaying their favorite game for the first time.

For the most part, RE2’s remake is just as much of a triumph as RE1’s, combining state-of-the-art tech and thoughtful self-reflection to make the old feel brand new again. The police station is significantly altered from its original layout, and yet similar enough that you feel like you know it. The more rote, later sections of the original game have been given new personality and contour—the greenhouse and sewer sections both stood out as impressively reimagined. The characters, too, have been smartly rewritten to feel more like interacting humans than archetypal action figures. Each one of them bore impressive nuance rarely seen in a Capcom title but crucial for good horror, in my opinion.

The action seems to lean heavily toward the “survival” side of things, with even plain-jane zombies sometimes taking an obscene number of bullets before they stay down. I appreciate how this adds to the “dangerous” feel of the game, but I sometimes felt like it had lost a little bit of the fun factor I associate with the shooting action of the entire series. Still, I see this as a stylistic choice rather than a flaw, and they also give you a handful of unlockable infinite ammo rewards in the post-game so you can go for a more action-packed “victory lap.” (Note: @jbsargent taught me that term :D)

Mr. X is worth his own essay, but I’ll just say he was always one of my favorite things about RE2 and he’s absolutely my favorite thing about the RE2remake. I wouldn’t change a thing.

Shortcomings

I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about the remake’s glaring mistreatment of the A/B campaign structure. The whole point of this game’s dual-protagonist hook is to show the unfolding of events from two separate but concurrent perspectives. Here’s what happened to Claire. Now here’s what happened to Leon. The remake sometimes gives us this—Leon deals with Ada while Claire handles Sherry and the police chief—but sometimes inexplicably puts Leon and Claire through the same events, implying that only one of these campaigns is happening. How else can you explain that both Leon and Claire witness, for example, Mr. X lifting the chopper wreckage to make his chilling debut? What point is there to an A/B campaign if they nullify each other? They may as well have done away with the “2nd Run” concept altogether and just let you pick the Leon story or the Claire story. This is one of those things that bothers me the more I think about it. It didn’t affect me very much in the moment, but looking back I don’t know what to make of the story at all. Who did what? The 2nd Run is slightly shorter than the first, but I would have been content with something even shorter if it meant a more coherent narrative.

They’ve also cut at least a couple of the moments from the original game in which Leon and Claire check in with one another, which I found to be enough to greatly hurt the sense of connection between the two characters. The moments when they do interact are great, but I wished there’d been a few more. They also speed through the intro movie on 2nd Run, employing a “Last time on 24”-like highlight reel instead of giving it the space it needs to establish the crucial atmosphere and character dynamics. I didn’t like that.

Camera placement is a debate that will probably never die in the Resident Evil community, and it’s hard for me to even decide where I stand on the matter. The use of fixed camera angles in the classic games was a stroke of genius that allowed the games to mimic the tried-and-tested techniques of horror film, but occasionally the shifting angles caused player inputs to get tangled, resulting in unintended frustration. The over-the-shoulder cam used in the RE2 remake and most other recent RE titles gives the player complete control over what they see. This is a much friendlier interface for the action sequences, but it also means the game can’t force you to look at anything. On my first playthrough, I missed four or five classic moments including the first appearance of Mr. X because I happened to be looking elsewhere when they occurred. I see this as emblematic of the sometimes conflicting aims of game design, where a game is both a plaything and a cinematic experience targeting specific emotions. I’m not sure there’s a perfect solution to this, but I appreciate that the game essentially operates like an autonomous ecosystem. If you miss the action it’s your own fault, but it’s true to life in that sense.

↑ This is actually one rare moment where camera control is taken away and you have to look. Gah.

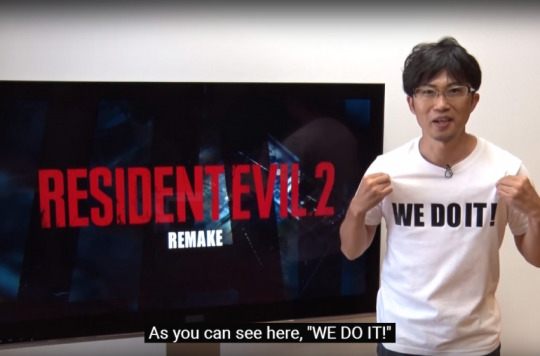

I don’t think there’s any fair way to conclude that the remake is better or worse than its predecessor, but I’ll happily submit that Resident Evil 2 is the best game ever announced via T-shirt. I think Capcom can look back with pride and say, "WE DID IT."

#resident evil 2#re2#resident evil#video games#games#gaming#remake#capcom#reflections#review#criticism#leon#claire#leon kennedy#claire redfield

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

After 200+ hours of playing Breath of the Wild, I have finished my adventure. Here are my thoughts. (Spoilers)

So, almost two months after its release, I have officially completed The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and oh boy, do I have a lot to say about this game. I’m a little hesitant to call this a review, I guess, because it’s not organized too well or intent on giving a score or anything silly like that. But considering my love for this series and acknowledging this game as a huge departure from what many have grown used to, its got my head spinning with a whole bunch of thoughts that I just feel like dumping somewhere. This is mostly an art blog, it feels a little weird sticking this here but I honestly don’t know where else I’d put it. I’ll try to organize my brain and keep things as short as possible, but for the most part I’m just gonna jump in.

Ok, let’s get the big stuff out of the way: I like this game. Even if you haven’t played it, if you’ve so much as searched Zelda within the past month, this near universal opinion shouldn’t be unfamiliar to you. You could go anywhere on the internet around its release and see overwhelming praise, 10/10, a “masterpiece” or even “the best game of all time”. I’m kind of opposed to scores and big statements like that because they have the power to label a game as perfect or flawless, even if they don’t mean to; but the acclaim isn’t necessarily undeserved, this is a great Zelda game, and a really good video game in general. One of the biggest reasons for this praise is attributed to how big of a departure it is, it really sets itself apart from past Zelda games; However, that’s also what inclines me to dissect this title far more than any of its predecessors.

Since this isn’t really a proper review, and I’m assuming most of the people reading this have already played the game in some capacity, I’m just gonna quickly summarize what I like about it. If you want more in depth conversations about the positives you should go ahead and find something on IGN...or Youtube or something I dunno, honestly anywhere, this game has gotten nothing but glowing reviews, it’s not too hard to find something better constructed than my stuff.

-It’s gorgeous, the cel shading and overall homage to japanese animated films *cough* Ghibli *cough* is wholeheartedly welcome and beautiful to look at. This is the first Zelda game where I didn’t want to cut the grass because it was just so damn pretty. I’d constantly find myself placing link in compositionally pleasing settings to just watch the world teem with life and wonder.

-The runes and their implementation with shrines and the divine beasts make for some clever puzzles, even if they are a lot of the times maybe a little too easy and kind of short. When the puzzles are at their best, you can’t help but smile.

-I like the basic concept of the story, it’s nice to see Zelda explored as a character. (Though I will say that Link not being as expressive in this title was a bit of a let down, he’s expressive in the world and not in the cutscenes which is odd. I know there’s a canon reason for this but still, I miss the personality from previous titles. I hope they weren’t trying to reel back on his facial expressions for fear of breaking “immersion” or something silly like that, no one I know sees link as themselves, I’d like to think most people really do see him as his own character.)

-The outfits are great.

-Different weapon types are super cool.

-I actually ended up not hating the voice acting, in fact, I feel like there should have been more of it.

-I love how the world is constantly being traversed by characters that always have something funny or useful to say. I remember one guy telling me that his name was Spinch and his horse was named Spinch too; so completely random. You engage with him further and he’s just like: “We’re both Spinch and I don’t even care.” It killed me, and it’s stuff like that that was part of what made exploring fun.

-It acknowledges the series’ timeline and lore in the most direct way yet. I particularly love how they sprinkled Fi’s theme into scenes with the Master Sword, it gave me chills. Makes you feel like all your past adventures really mattered.

-Music is beautiful, the main theme and Hateno village are some of my new favorites and I can’t wait to hear them Live. Gotta love that Dragon Roost callback too.

-Character design is great. Even the most insignificant npcs have great character designs. This particular reincarnation of Zelda is definitely my favorite appearance wise, the developers did a great job with making her look adorable, dignified, and adventurous all at the same time.

-I like the return of character schedules from Majora’s Mask, makes the world feel alive.

-The champions are all great personalities, but it sucks we couldn’t spend more time with them. (more on this later)

- Prince Sidon is hilarious and really charming.

-Paya is disgustingly cute.

- Bolson is the best god damn npc in the game, that gay ass motherfucker.

-Climbing is fun, unless it rains.

- Fighting is fun (until you’re about 50 hours in and it starts being a little less creative. Once you have a ton of money and really good weapons, the incentive to fight and raid camps isn’t really there anymore unless it's fighting for just fighting’s sake. This made be a bit sad.)

-Based on its basic game mechanics alone, Breath of the Wild is, in general, pretty fun. There’s a lot more I could say, but I feel like it’s fairly obvious what the really good things are in this game.

The list goes on and on and on...but these are my main take aways without getting TOO entrenched into a stream of consciousness. I don’t really feel the need to go too in depth about the games positives, because they’re widely discussed and loudly appreciated across the board; I wanted to be brief with my addition to the echo chamber. With that said, I actually have a few fairly substantial grievances with this game that prevent it from being a masterpiece for me.

Saying this feels like betraying a best friend, especially after waiting 6 years for this game. But I think it’s necessary to put these thoughts out there when a game gets universally good reviews, I want Zelda to grow and improve beyond this point. It’s obvious Nintendo won’t see this shit, but it’s good to get a conversation going, especially when every single Zelda game gets widespread acclaim upon release and only a year or so later do people tend to tone it down a little. This is fairly ironic in my case, as Skyward Sword is one of my favorite games and it seems to have the starkest contrast between its initial opinions and those that popped up a year after. I just have some things that really irk me about this game, which sucks because I actually love it a great deal, I’m super torn.

My biggest takeaway from 200 hours of traveling across Breath of the Wild’s world was that its greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. Nintendo set out to spread its wings and build this immense world that inspires wonder and awe, and it certainly does that, but I feel like that’s mostly all the game is at times. It’s funny, because as soon as I start to say stuff like this, I can’t help but think, “Wow that’s actually really great, I’m glad the game went this direction.” But I also feel heavily conflicted about that direction’s consequences. This may sound strange and it’s not really bad, but I felt like the world is almost so open ended with itself that its identity is spread a little thin.

I’m kind of going against my own logic here, because I’ve always wanted a Zelda game with an immense amount of side quests to beef up the experience outside of the main quest. I’ve prayed for a huge world to explore, to really feel the enormity of this land that needed to be saved. And there really is a lot to do, there's a ton, but only a handful of the sidequests outside the shrines have much heft. The game doesn’t really have a set pace as a result, which can be seen as a good thing I guess. I can agree with the sentiment that this choice was necessary as a stepping stone going forward, I think Zelda definitely benefits from the nonlinearity approach, and Nintendo going as far as they did with it this time will help them see its advantages and disadvantages. If Skyward Sword was an extreme in linearity, Breath of the Wild is an extreme in the exact opposite direction. In my opinion, they both still work well in their own regards, albeit in incredibly different ways.

When I say that the game doesn’t have as much of an identity compared to past Zelda’s, I mean that in a way where the identity of the game is largely shaped by the player’s own experience and not by the narrative itself. This can be seen as a huge triumph in player agency, where the power (or in this case courage) really is in the hands of the player. But you can’t curate nonlinearity, at least not entirely. As a result, we tend to lose some of the pacing that made past titles feel “epic”. I guess what I’m getting at is that my main gripe has to do with how the game’s narrative structure comes together.

The developers were definitely aware of a narrative problem, as they needed a way to glue the game together story wise, and the memories were a pretty clever way to do it; honestly, I don’t know how else they could have made it work with their open air concept. But as much as I find the story compelling and interesting, there’s simply not enough of it, which is a real shame because you feel a need to get closer to these characters, especially the champions. Much of this game feels like you are showing up late to the party. There's a weird dichotomy between the past and present as a result. You end up feeling like you need to care more about the champions in the past, but characters in the present end up getting more development, just less emotional weight attributed to them. It’s a weird flip flop, because I loved Prince Sidon as a character, and thought he was the most developed out of all the main quest based npcs, but Mipha kind of steals the climax of the Zora’s Domain story. What sucks about this is that Mipha has, what appears to be on the surface, a tragic and emotionally affecting story, but we don’t get enough time to dwell on it really, so we’re in this weird flux. This past and present problem actually has made me feel the most disconnected from Link than I ever have, and if I was gonna be disconnected I would have at least liked to have seen him show a little more personality, but he only does this in small instances in the present.

This formula disappointed me more and more with each main questline, especially when all the others tended to be less concerned with getting you familiar with or attached to their respective characters. The worst offender is the Rito area, which I swear can be completed in an hour. It really cheats Rivali out of getting any meaningful development, which is a huge missed opportunity because he was funny, quippy, and a nice rival character for Link. Imagine meeting Groose at the beginning of Skyward Sword, except at the end of the tutorial someone pushes him off Skyloft and he straight up dies, the end. Think about how big of a missed opportunity that would be. That’s kind of how this felt.

Now I know that you can argue that Zelda has never been about the story, but honestly I still thinks that’s up to the player, no matter how simple these stories tend to be. It’s mostly less about story and more about how much time is spent on the fun characters Zelda is known for, and the game loses a bit of its heart as a result. A lot of people, like me, are super into the lore and the characters this franchise has to offer; things don’t need to be convoluted like Kingdom Hearts or emotionally complex like the Last of Us. Many players enjoy the adventure of befriending characters, helping them with their problems, and feeling fulfilled by that alone.

Quests that had this fulfillment element were my favorite, such as cooking a rock for a malnourished Goron to help him regain his strength, or building a town from the ground up with a bizarre cast of carpenters that you can’t help but adore. These are rewarding for me, not because of the loot, but because it’s simply just entertaining and makes me feel like I really accomplished something. Once I reached about 90 hours, I didn’t need rupees, or another royal claymore, what I was really looking for was a reflection of how I impacted the world around me. I wanted to suspend my disbelief and truly get absorbed in this world not only for its beauty and sheer size, I wanted to feel like I mattered to its inhabitants too. And the game does this enough to be fairly satisfactory. Though, there are plenty of quests that get halfway there but end up feeling more like fetch quests, which aren’t so bad if they have a nice reward, but they’re still kind of bland and sometimes a chore.

To kind of wrap all this up, I want to say that Breath of the Wild’s biggest and most glaring problem is that its main quest is severely lacking. There is a lot to do in this game, just not a lot of “big” and memorable things. There’s an almost endless list of small challenges, but few end up feeling all that compelling. I know a lot of people have been talking about the dungeons being a huge weakness, and I think that's definitely part of the problem. There really needed to be more substantial dungeons in this game, I’d say there’s about a dungeon and a half in this title. Maybe we can have a discussion about how the shrines make up for that, but I feel like at least for me, most of them were very simple and too many of them were rewards for easy feats or tests of strength. All things considered, the breadth of this game is impressive, but imagine if you fit a main quest from The Wind Waker or Twilight Princess on top of this huge world; imagine big dungeons with a well paced main quest, along with all these sidequests and a beautiful landscape, that would be amazing! I know this comparison has been made a bit too much, but Skyrim found a way to have a good linear main quest packed into a non linear world, you could in fact avoid it altogether and just do “side quests”. Many of its sidequests had significant weight to them that made them feel like they could've been part of the main mission, you weren’t left with a sense of emptiness if you avoided the main route. I think Zelda could learn a lot from this kind of approach to open world games.

Now I will say that there’s a lot to Breath of the Wild’s main quest that I really love (i’ll be doing a lot of fan art because of it!), I just think it needs to be expounded upon a bit more. There’s all the makings of a true masterpiece here, but the center of it feels a bit fragmented. Bigger dungeons, bigger story, more enemy types, more villages etc. I think the game needs more of these large central elements. There's so much I could say about this game, but that would take forever, these are more or less my biggest criticisms. I once again want to reiterate that I like Breath of the Wild and I really love Zelda as a series, I can’t stress that enough. Feel free to disagree with me and maybe start up a dialogue through messages or something, I’m always willing to discuss! I’m not super focused on checking this for structural issues, it’s not really an organized essay, sorry if it was a bit rambly.

Thanks for reading!!!

Sidenote: I’m aware of the story DLC and new dungeon in the future. I’m extremely excited about this and the DLC will hopefully address my grievances with the game.

#Zelda#Breath of the wild#The legend of zelda#The Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild#loz#I'm critiquing a zelda game...#hope I don't get killed

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doom Eternal review – the same orgiastic thrills with a creeping weight of story • Eurogamer.net

“Story in a game is like a story in a porn movie,” the original Doom’s programmer John Carmack once wrote. “It’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.” A connoisseur of sleaze might object that story often makes for sexier porn – after all, story tends to involve chemistry, atmosphere, suspense and all the other emotions that distinguish intimacy from the act of banging together genitals to spark a human being. Still, if we’re going to liken games to pornography, and assuming it’s the more kinetic kind of pornography you’re after, I heartily recommend Doom Eternal: a looping video compilation of oversized guns and fists plunging into squelchy orifices, spurting along at 60 frames a second.

Doom Eternal review

Developer: id Software

Publisher: Bethesda

Platform: Reviewed on PS4

Availability: Out March 20th on PS4, Xbox One and PC, coming later this year to Switch

2016’s accomplished reboot was already quite the debauch, its firefights punctuated by leering close-ups of skewered hellspawn, its heavy metal soundtrack always building to a crescendo. Eternal turns up the heat even further, allowing you to dash and flip your way around arenas that are newly fixated on the vertical axis. Dripping organs are wrenched out of, then stuffed back into, demon torsos; chargeable alt-fires scream for release; health orbs spatter the ramps and chokepoints like – well, you get the picture. The environments often look like the work of an adolescent H.R. Giger who’s just got into AC/DC. Aside from silvery Protoss-ish fortresses and some seriously down-at-heel office blocks, you’ll wander labyrinths of squirming flesh, using runes to unclench toothy sphincters and shearing pop-up tentacles in half with your shotgun.

Some, of course, will soberly insist that all of this is just good, honest, videogame violence – clean, upstanding fun with absolutely no over- or undertones whatsoever. And to these people I say: when I am walking down the shaft of an enormous spear, straight into the pierced belly of a reeling, gaping titan, it is difficult to argue that there isn’t some kind of metaphor in play. “Rip and tear”? More like rip and splooge.

Carmack’s porn quote (which he has since qualified a little) epitomises the view that narrative in games is always an imposition, a foreign body carried over from film and literature. It’s a view that has been roundly debunked. The thing is, though, Eternal does have a story, somewhere in amongst the parade of demon O-faces, and while that story is lightweight by Zenimax game standards, it feels hopelessly grafted on. Having thwarted Hell’s invasion of Mars, the legendary Doom Slayer must purge Earth itself of diabolical interlopers, setting out from a gothic orbital station turned customisation hub to a series of ravaged cities, factories and temples that feel on loan from Gears of War. In the process, he must also tunnel back into a startlingly eventful past, sitting through flashbacks and wrangling with old allies.

The 2016 game was a thrilling reimagining of the speed and ferocity of 90s Doom combat, but it also magnified Doom’s narrative trappings, adding in cutscenes, audio diaries, codex entries and mid-mission dialogue – a curious reversal of one of id’s key decisions with the original game, which was once planned to include a sizeable narrative component written by co-founder Tom Hall. Eternal adds yet more to the load, expanding the cast and redoubling the emphasis on lore.

youtube

The cutscenes are now a mix of first and third-person, which means the Slayer is a fully tangible human being – one you can, moreover, trick out with unlockable outfits and weapon skins – rather than a pair of enormous fists twitching beneath your aiming reticle. He feels enclosed by the fiction, rather than, as Christian Donlan put it back in the day, like a man who is also playing Doom and who shares your resentment for anything that gets in the way. There’s some effort to explain the character’s superhuman prowess, with one scientist suggesting that you represent humanity’s rage to survive, as opposed to humanity’s love of making Cacodemons pop in slow motion. The Slayer even has a voice these days, though I think he strings together maybe five words in total.

True, our man in green never looks happy with all the attention, stomping impatiently through cinematics while other parties monologue at his retreating head (if they’re lucky, that is – the fate of most speaking roles in Eternal is to be ground up like tuna). Nor are you required to listen to the audio diaries, or dip into the codex. But these elements drag on you nonetheless, like the lakes of purple goop that stop you running or jumping in certain levels. They’re a deflating reminder that you are no longer here just to indulge your baser instincts. Conversely, the developer’s guilty awareness that people don’t play Doom for the narrative means that when you do dig into the world-building, you’ll find it to be scanty and by-the-numbers: a set of tired references to ancient races, legendary battles and fallen cities.

Still, if visceral gratification is the goal, Eternal amply delivers. The combat is once again about ceaseless pivoting between attack and retreat, care of a raucous battlefield ecology which sees you ripping ammo, health and armour refills from your prey rather than just searching for medikits or finding somewhere to cool off. Stun a foe and you can execute them for a smidgeon of health. These executions double as windows of rest, with other demons easing off till you’re done rearranging your victim’s anatomy. They can also be triggered from metres away, warping you to the target without even the courtesy of a transitional animation, which means you can use them to escape or get behind a mob. Bisect demons with your trusty chainsaw, meanwhile, and you’ll be rewarded with a geyser of ammo, restocking all your weapons in one dollop. You’ll need plenty of chainsaw fuel to carve up the bigger demons, but you’ll always have enough to carve up the smaller “fodder” demons, who spawn endlessly throughout each battle till the larger demons are slain.

This hyper-aggressive resourcing style forces you to close the gap with foes who are, in any case, very good at running you down. Some, like the minion-summoning Archville, are closer to terrain hazards, but the underworld’s legions are light on snipers or artillery; pretty much everybody, from the podgy Mancubus to the serpentine Whiplash, is hell-bent on getting in your face. It sounds like chaos, and often is, but there’s a lot of science to Eternal’s combat, and solid artistry to how the key variables are conveyed from second to second. Ammo, health and armour drops are colour-coded; staggered enemies flash blue, then orange when they’re about to recover. The game’s audio is similarly readable, once you acclimatise to the roaring heavy metal soundtrack. You’ll learn to follow the progress of the battle by ear – be it the tink of a cooldown gauge, the belch of a Cacodemon that has just swallowed something explosive, teeing it up for an execution, or the nasal howl of a charging Pinky.

New variables include an ice grenade, mapped to the trigger, which lets you flash-freeze whole groups to interrupt otherwise lethal offensives. You can also light foes up with your shoulder flamethrower attachment, causing them to spit out armour parts and further motivating you to fight at close quarters when you’re hurting. The most important change-up, however, is your newfound agility. Besides availing himself of launchpads, the Slayer can now perform aerial dashes, scuttle up laddered surfaces, swing from monkey bars and use a Super Shotgun-mounted grapple line to yank himself towards or past enemies.

This encourages showboating reminiscent of anti-gravity duels in the sadly-forgotten Lawbreakers. You might grapple somebody, fling yourself past them while firing your shotgun pointblank, then double-jump to a monkey bar, hurling yourself at a stunned Pain Elemental, then drop neatly onto a launchpad while switching to your Heavy Assault Rifle so that you can carpet the arena in micro-missiles. The weapons are by and large entertaining rejigs of DOOM 2016’s offerings, with two upgradeable alternate-fires per gun that lend themselves to different tactics and different opponents. Your shotgun, for instance, can serve as either a sticky grenade launcher – useful when trying to shoot the turret off a Cyberdemon – or a buckshot-firing Gatling gun for crowd control.

Inevitably, the charm of Eternal diminishes the further you travel from these firefights. Its grander story component aside, the game is slightly over-burdened with customisation systems. Besides tracking down weapon mods in levels themselves, you’ll equip runes for perks such as slow-mo when you aim in mid-air, together with Praetor Suit upgrades such as the ability to suck in health drops from further away. There’s a knack to combining Rune perks, especially when tackling “Master” versions of levels that have more punishing enemy spawn patterns, but the role-playing systems aren’t novel, and the associated menu-diving bogs down a shooter that’s at its best in the thick of the bloodshed.

What really saps Eternal, however, is the predictable way the campaign once again breaks down into combat bowls and platforming stretches that feel like they’ve been stripped at random from Prince of Persia: Sands of Time. There are collectibles to unearth, some tucked in high alcoves or behind smashable walls, together with optional hidden battle chambers, but the alternation of shoot-out then jumpy bit then shoot-out is the same throughout. Boss battles are the biggest change of tune – the final clash is a doozie, a gruelling two-phase affair in which your nemesis looms over the layout like the world’s angriest D&D player. But some of them are just annoying, a question of repeating a tactic to whittle down a health-bar. It’s revealing that the game offers you a layer of all-but-indestructible Sentinel armour after a certain number of deaths, though Eternal’s accessibility is otherwise refreshing: dropping the difficulty doesn’t cost you anything in terms of progress, and you revert to the previous difficulty once the bossfight is over.

It’s worth remembering that old school Doom wasn’t just a series of one-man massacres. It could be ominous and anxiety-inducing. It had monsters you could hear through walls, shambling about in the guts of the level, and concealed partitions that slid open without warning. It had a narrative, just about, but it didn’t try to root the weirdness of its concept or spaces in lore, and its secrets were as much about enjoying the possibilities of virtual architecture as securing a power-up. It was a world of alarming corners and optical tricks that deformed and shifted simply because it could. For all its abundance of things to find, you don’t get quite the same feeling in DOOM Eternal. At times, it feels like the levels have been designed backwards from the completion screen, with its grocery lists of optional treasures and encounters. You might argue that 3D worlds are simply less surprising on the whole in 2020 than in 1993, but that’s to ignore the work of countless DOOM modders whose creations, made using id’s original engine and tools, continue to startle and intrigue today.

The missing link in this review is multiplayer, which is offline for the moment, but which already looks like a step up from Doom 2016’s ramshackle online. It’s a strictly asymmetrical affair, with one player starring as the Slayer while the others control one of five demon breeds from the campaign. As a demon, you can summon AI-controlled hellspawn with the D-pad, so victory is presumably as much about mob strategy as dealing damage yourself. Which sounds like a pleasant way to cool off once you’ve tired of the sweaty embrace of a campaign that, for all its breaking of Carmack’s ancient maxim, has a shot at being one of the best you’ll play this year. Still, Doom Eternal leaves me undecided. The game is fundamentally the 2016 reboot again with new props, and its dogged commitment to Doom’s narrative universe is as baffling as the firefights are exhilarating. Is this really all Doom can be, nowadays – a cascade of collectables, unwanted cutscenes and the spectacle of a gurning demon face, forever?

from EnterGamingXP https://entergamingxp.com/2020/03/doom-eternal-review-the-same-orgiastic-thrills-with-a-creeping-weight-of-story-%e2%80%a2-eurogamer-net/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=doom-eternal-review-the-same-orgiastic-thrills-with-a-creeping-weight-of-story-%25e2%2580%25a2-eurogamer-net

0 notes

Text

Video Game Retrospective - Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire

George Lucas had a thing for “multimedia projects” before and after going crazy and messing up his own franchise with ill-advised ideas and direction and generally not having any proper oversight. that might’ve salvaged the prequels. A more recent pre-Disney example was The Force Unleashed, which was a really neat concept but fell flat for me gameplay-wise because, well, it feels a bit quaint after experiencing the versatility and general flexibility of Jedi Knight and the awesome insanity of Metal Gear Rising. (Speaking of which, a Star Wars game done by Platinum Games with the right budget, time and director would be absolutely incredible.)

The one big project Lucas worked on before the prequels was Shadows of the Empire, which was functionally an exercise of creating a whole bunch of material around a theoretical interquel film between Empire and Jedi without there actually being a film, though I think the idea of actually producing a film was entertained at one point. There was a fairly decent novel by Steve Perry, comics by Dark Horse, and an absolutely incredible soundtrack by Joel McNeely (who was recommended for the job by John Williams himself), but arguably the biggest part was the video game, which initially released on the N64 and later ported to the PC with CGI cutscenes and voice acting.

I’m gonna say this up front - I have genuine nostalgia for this game, and not just because of the surprisingly faithful recreation of the Hoth battle. That being said, after recently getting the PC version of this game myself, it’s... Not good. It’s playable, especially with mouse and keyboard controls that allow for strafing, but unfortunately there’s more bad than good. That being said, it’s still worth examining.

Shadows of the Empire focuses its game adaptation around Dash Rendar, who is a rather shameless expy/clone of Han Solo, though it’s a bit more justified by the fact that he’s friends with Solo and in some ways a bit of a friendly rival. Frankly, you could do a lot worse for a Star Wars protagonist, it can be said that the much-beloved Kyle Katarn from the Dark Forces/Jedi Knight saga was at least partially cut from the same cloth. But at any rate, if you want to play as a Jedi, you’re out of luck here. On the bright side, though, you get to do some pretty badass stuff as Dash - fighting an AT-ST on foot and winning, a jetpack duel with Boba Fett (plus fighting the Slave I when Fett decides to get pragmatic), flying directly into Prince Xizor’s skyhook base to blow it up from the inside... This game has quite a bit of variety.

One thing to get out of the way quickly - the game’s mechanics are “janky” and feel poorly-programmed in many ways. Moving down a downwards slope causes Dash to fall down it rather than walk in many cases (which has resulted in a otherwise-avoidable deaths), the way the movement works in general can be awkward in dangerous areas if you’re not using an analog stick due to Dash’s high maximum movement speed, jumping doesn’t account for the velocity of moving platforms (making the junkyard sequence awkward to navigate) and the Stormtroopers (among other enemies) are more accurate with their blasters than you are (and I don’t just mean they’re still inaccurate, they’re actually as precise as Obi Wan said they were in this game) and are often placed in awkward locations, making shooting them without getting damaged to be often difficult if not impossible in later stages. The game is playable, but it can be fairly difficult due to unfair mechanics and enemy placement. Oh, and the speeder chase doesn’t intuitively inform you how the hell you’re supposed to make jumps. I could go on for a while about, this. Also, the PC version, to my knowledge, doesn’t let you rebind keys, and mouselook controls both turning and moving forward and backward, which makes it a bit awkward if you find the mouse and keys fighting for moving your character.

In general, it feels like this game was made in that period where developers in general had the unenviable position of trying to figure out how to make things work in 3D. While the devs of this game weren’t really able to make something that aged well, it wasn’t for a lack of trying. The only things that they really did well were the flying/space vehicle levels, and even those would be later outdone by Factor5′s Rogue Squadron. That being said, this game deserves the recognition it gets for being the first game to successfully recreate the Hoth battle, complete with bringing down AT-ATs with tow cables.

Before we continue, I might as well talk the differences between the two versions of the game - the PC version replaced the N64′s ‘simple’ cutscenes (mainly just static images with simple tweening animations) with CGI FMVs, and provided full voice acting. The voice acting is fine, but I honestly prefer the N64′s cutscenes in many ways. Aside from the use of just the one theme for all the cutscenes (granted, it’s a damn fine theme and provides enough atmosphere), the visuals are really nice compared to the even worse-aging CGI of the PC version’s FMVs, and some scenes are outright superior in the N64 version - IG-88′s introduction, for example, is unsettling, with him rising out of the junk pile, and his appearence with the red eyes is genuinely creepy (the guy scared the hell out of me as a kid, but I guess I was more easily scared back then, I used to be terrified of Andross in Star Fox 64/Lylat Wars as well back then, amongst other enemies and bosses during that generation), whereas the CGI version makes him look much less threatening and his voice doesn’t help either. Really, the N64′s cutscenes are absolutely dripping with atmosphere, which the PC cutscenes lack. On the bright side, both versions use McNeely’s soundtrack, which is impressive considering the N64′s known space limitations.

This game does have some replay value, just to note - every level has a collection of “challenge coins” (which are actually floating, silver Imperial emblems) to find, and beating the game on hard or above nets you a secret ending revealing that Dash successfully faked his death while escaping from the Skyhook by hitting hyperspace just as it blows up. None of the other media for the project reveals this twist, and the novel ends with Luke assuming that Dash perished because he wasn’t on his game because he failed to save an allied ship during an earlier space battle (turns out he couldn’t have done anything about it anyway) and was still reeling from the guilt.

In summary, it’s not a good game. But it is still noteworthy as far as Star Wars games go for what it did and what it tried to do, and its genuinely redeeming qualities (mainly the soundtrack). If nothing else, at least watch a let’s play of it or something if you haven’t experienced it in some form, or get the PC version via Good Old Games.

Oh, and amongst the other stuff that was in the recent Star Wars Humble Bundle, there’s the excellent Rogue Squadron 3D, and Galactic Battlegrounds, which is basically a Star Wars version of Age of Empires II, made by AoE’s developers, which is really cool and worth playing if you’re an RTS buff.

0 notes

Text

Video Games and Society- Rian Bannick

In the book, To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee, we see the journey of a young child learning about the real world, escaping their childhood premonitions and seeing the injustices of race and how certain groups are put down in society just because of that group treatment in the past. The game industry started off with basic arcade games that required payment for each game played, and largely targeted children and adolescents, as they're young minds would hopefully not realize that these games were meant to be impossibly difficult as to extract the most profit. So the seeds had been planted for this new type of media; a trap for children to lose their allowances accomplishing nothing and most likely begging their parents for more quarters so they can finally put that feeling of “I was so close that time!” to rest. This frightening many parents into a scare that their children were being made into addictive adults with no sense of willpower. However, this was just the beginning. With the massive success of arcade games, larger industries and experimental methods started to pop up. The first home consoles were appearing in the stores with their games, and their pixel graphics and iconic soundtracks. Games like Super Mario Bros in 1985 introduced many players to the idea of local multiplayer. A space where teamwork would be the only ideal way forward, teaching the new generation of players how to work together with your peers effectively. This is something that our American Schooling system has always stressed to students, as it's implications in the adult world are paramount. However, as early game companies like Electronic Arts and Nintendo began to move into the digital era, their staff began to include people who grew up with Super Mario and M.U.L.E., and the industry itself had shifted from strictly a children's pastime, to a new form of media for all to enjoy, similar to film, music, and literature.

The problem we see today is the same fear from the industry’s beginnings as roguelike adventures and endless games of increasingly difficult levels, where people fear Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto V turns harmless teens into chaotic criminals. For many, these are sensationalized ads meant to grab the attention of gullible parents, because news companies need profits to stay afloat. Also, only a small number of studies have actually been done on the topic, and their results haven’t concluded that games cause reduced empathy or violent behavior. In fact, a study done at Brock University dove into this back in 2012, finding that the games subject played correlated with their behavior, but that this behavior existed before the gaming ever took place. In other words, people with violent tendencies may be attracted to darker, more violent video games, but just because a normal person plays a violent game, they won't be indoctrinated into being more violent, or committing acts of crime.

Other arguments have been made about games harming eyesight, desensitizing players to horrific acts, and being dangerously addicting. However, Sara Winters, an adult living Ocular Albinism, experienced an increase in her eyesight of 200% over two years, going from 200/20 vision, to 100/20 vision after being exposed to the games Breakout and Pokémon Red for her Game Boy during her youth. As an adult, she helps educate visually impaired children, using similar games that encourage reading and coordination to help her students get better in a way that comes naturally; having fun. Also, some groups make the statement that games desensitize players to the terrible things that occur on-screen. Such as horror games and violent action shooters depicting gore and grisly crimes. Though, this is the same case with violent movies, horror books, and even the news, which constantly depicts crimes and tragedies to increase ratings, so why should games take the blame, and be forced to censor themselves, when horrific imagery in H.P. Lovecraft has gone uncensored for years. Additionally, people have said that games are addicting, using Skinner-Box mechanics to reel in players to a never-ending loop of play that takes over their lives, getting them kicked out of college, ruining relationships, and tormenting the player an activity they don't really enjoy, but can't stop sinking their life into. Many people can admit to this, even very popular YouTubers like James Portnow of Extra Credits and Austin Hourigan from ShoddyCast, but they tell a different story. The games didn't cause the problem, there was already a problem, that games were just an outlet for. As Austin put it: “...it’s not just the games themselves causing the compulsion, but rather they're just a symptom of something lacking in someone's life. Either autonomy, a sense of purpose, or, maybe, like in my case, a state of mental illness.” Thus, it's not that games are somehow evil, or addictive, or worse than any other form of media. Sure there are bad developers and shovelware, but this true with all expressive mediums, and games shouldn't be treated any differently just because their troubled beginnings.

Games can also be a force for good, not just a source of entertainment. Undertale by Toby Fox is an outstanding example. Where most developers would make a colorful, eighty-hour RPG in an underground, fantasy setting, with the common features we've come to expect; grinding in a zone to level up, beating all the bosses, and defeating some grand villain, Undertale told a very different story. In Undertale, by all means, you could still do all those things, but the game questioned the morals of that fact in a way that most triple A game industries haven't done for their entire existence. You could go the way of most games, slaughtering everything in your path until the fateful end, when you've reached the highest level, with the best gear, when it's time to fight to final boss, and you realize, you're the bad guy. In order to avoid this however, you have to painstakingly persevere through frustration and show mercy to the opponents and monsters that mean you harm, showing that, doing the right thing isn't always easy. Other games like Battlefield 1 show a great deal of respect towards veterans, giving players a singleplayer campaign that isn't solely supposed to be entertaining, but also, especially in cutscenes and the opening minutes of gameplay, show the futility of war, and the struggles real soldiers face, so that, just for a brief moment, you come close to perhaps understanding the dread of being in the trenches waiting to die, or coming home to world that just wants to weep for you, and pity you as you are haunted by the scars of your past. Games also can instill empathy in players, as games tackle darker elements of the human experience that other media simply can not. This War of Mine does this by showcasing some awful choices during your gameplay. For example, while out scavenging for supplies you desperately need, you hear a young woman who is about to be raped. You could rush in there to save her, but the criminal is well armed, and you don't have a weapon. You'd be putting you and the people who are counting on you to bring back water and medicine in danger by doing this, but you might save this woman. Or you could ensure that the family you've made makes it another day in this harsh world, but you'll have to live with the knowledge that you left this poor woman without even trying to save her. This gives players a new understanding of the tragically difficult choices people in underdeveloped and war-torn nations have to face on a daily basis. Giving players a new appreciation for their own lives, and empathy for others that have to make these impossible choices. It just wouldn't be the same watching that choice unfold in a theatre, or reading it in a book as it would be to actually be forced to make it yourself.

Games are still young; they only really began to catch speed forty years ago, and only in the last fifteen or so have they really began establishing themselves as a true form of media in which people of all walks of life can play and be affected by. Just because games have a history of exploiting children out of their parents money so they can make a profit doesn't mean that the new companies and developers on the scene shouldn’t be able make something amazing and atmospheric for all people to immersed into. Books depict a new world for us to reconstruct in our minds, films show us that world in ways we couldn't conceive, and games give us the chance to interact with that world in a very real way. It is foolish to say that video game companies shouldn't be allowed to continue making games that tackle serious topics solely on the basis that some desperate news stations said they're dangerous, or because of their somewhat questionable history, especially when they can teach us ideas and emotions we've never known.

Despite all of this, however, games are still being censored on the claim that they’re too mature for young audiences, but games aren’t just childspay anymore. When games are mature and dark, telling a sophisticated, tragic, or hopeful tales of normal people who, by the player’s own willpower and inner strength to keep going despite the difficulty of this particular boss, or whatever the game tends to feature, sure young people will try it, simply because that’s what kids do, they break the rules, play games with M ratings, and watch R rated movies; it isn’t Spec Ops: The Line’s Fault that your child that your child wasn’t ready to experience the gritty, self-loathing terror that came with playing it. Games can show us what it means to literally “climb into [someone else’s] skin and walk around in it" (Lee 87), and feel what our movie and book protagonists feel. We make their tough choices, overcome their insurmountable challenges, and understand that, in the seemingly hopeless last moments of their world, that just maybe we can save everyone we’ve come to love by giving ourselves up, with no care of our own survival, only the saving of this world. Games can allow us to stand with our heroes, be them, feel the fear of death, the curiosity of the unexplored, the blood-pumping stress of a ticking clock, the joy of camaraderie, the pain of loss, and the tragedy of sacrifice and that is truly a beautiful thing.

0 notes