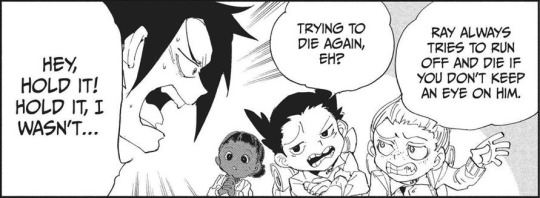

#the ways this family saves each other man; i am disproportionately sentimental about this series but it warms my heart

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

(Mystic Code Book Chapter 2 Bonus Comic for Chapter 48)

In case anyone hasn’t seen it yet or needed a reminder of how much these two love their older brother and how much it hurt them to see him at his absolute lowest point.

#translated by 14thNeah but I tweaked it with some larger font#The Promised Neverland#Yakusoku no Neverland#TPN#YnN#TPN Ray#TPN Thoma#TPN Lannion#YnN Ray#YnN Thoma#YnN Lannion#Ray 81194#Thoma 55294#Lannion 54294#Ray#Lannion#Thoma#Big Bro Ray Tag#FSS Chatter#Promised Forest Arc#TPN 048#they tease. they tease because they love 🤧#we still don't know how much they heard of his speech to Emma about how he fully believed he deserved to die#if they heard anything at all since they might have been running around right up until they banged on the dining hall door#but they were definitely present for Emma slapping him and he was covered in gasoline#not the way one would normally act unless they were quite Distraught™#bless Shirai and Demizu for including this it added 5yrs onto my life 🙏🙏#they care so fucking much your honor omg#the ways this family saves each other man; i am disproportionately sentimental about this series but it warms my heart#“You're worth saving‚ Ray‚ and we love you”

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Time for the Hospitality Industry to Listen to Black Women

History shows us that the novel coronavirus will impact black women restaurateurs, and their businesses, much harder

Before the pandemic, our nation was in the early stages of battling an epidemic that plagued our beloved hospitality industry: the biased structural policies, born out of our country’s legacy of racism that guaranteed that black Americans would continuously work at a deficit. Painfully honest conversations — dissecting the ways in which decades of systematic racial and gender inequality festered in the industry — had finally begun to gain traction in on- and offline spaces. But, collectively, we’d barely broken through the dysfunctional infrastructure that allowed certain groups to fail harder and faster when COVID-19 struck.

Chef Deborah VanTrece was ringing the alarm prior to the coronavirus pandemic. She regularly brought discussions of industry inequality to the table through her dinner-and-conversation series that centers black women in hospitality. “It was something that we had just started talking about at Cast Iron Chronicles, and a lot of other chefs were talking about it,” says VanTrece, owner of Twisted Soul Cookhouse & Pours in Atlanta. “But the conversation wasn’t finished. It still isn’t.”

“As much as we’ve accomplished, I still feel isolated and that I am by myself. I don’t think any of us should feel that way. We should be checking on each other. It’s like [coronavirus] happened and every man for himself,” VanTrece says. “And when I think about it, we were pretty much like that in the first place; that’s why it’s so easy for it to continue now.” Isolation has become a theme in our shared new normal of stay-at-home orders, but what VanTrece is describing is a sentiment long echoed by black women in the industry. Yet seeing the divide continue during these times is heartbreaking for VanTrece. “If we were ever needing to be one, it’s now. We need to be one.”

Black and brown voices are largely excluded from overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry

As we grapple with lives lost and the magnitude of devastation caused by novel coronavirus, accountability and transparency seem to be overshadowed by crisis-led pivots while we brace ourselves for what’s to come. And yet again, black and brown voices are largely excluded from policymaking and overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry. In the face of this pandemic, some may say the pursuit of equality has been railroaded, maybe even understandably so. Others see the crisis as a hopeful confirmation that institutional change is inevitable. Because if not now, when?

In order to know where we are going, we have to understand where we’ve been. Black restaurant owners, black women especially, are in a more precarious position from the get-go. According to the latest figures, from 2017, black women were paid 61 cents for every dollar paid to their white male counterparts, making wealth generation much more difficult. And while one in six restaurant workers live below the poverty line, African Americans are paid the least. Access to capital has been a steady barrier of entry, especially for black women. Black- and brown-owned businesses are three times as likely to be denied loans, and those that are approved often receive lower loan amounts and pay higher interest rates. For a population more likely to rent than other demographics, offering up real estate as collateral for traditional loans isn’t an option. And even for those who own a home, the lasting effects of redlining, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, and low home valuations are palpable.

In other words, the wealth gap, combined with a lack of access to traditional loans and investors for start-up capital, puts black women at a disadvantage before they even open the doors of their restaurants. “A lot of us have had to build our businesses from scratch, and that may be through personal savings and loans, through family members, credit cards, or we have refinanced our homes,” says chef Evelyn Shelton, owner of Evelyn’s Food Love, a cafe serving comfort food in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood. “We are in uniquely different positions when we start, which makes where we are now even more difficult.”

In the East Bay, chef Fernay McPherson, owner of Minnie Bell’s Soul Movement, a food truck turned brick-and-mortar now located in the Emeryville Public Market food hall, is offering a limited carryout menu in an effort to keep her staff afloat, noting that some are single parents. “I was a single mother, so it’s a lot to take in when you’re thinking, ‘How am I going to feed my child? How am I going to make rent?’” During the Great Recession, McPherson was laid off and had to short-sell her home. She started Minnie Bell’s in 2009, as a catering company, while also working full-time as a transit operator in San Francisco. “It was hard being a mom, driving a bus, and trying to operate a business. It was a lot on me. And my decision was me. To work for me.”

Working multiple jobs is a necessary for many entrepreneurs whose bootstraps are shorter to begin with, says Lauren Amos, director of small-business development at Build Bronzeville, a Chicago incubator that advocates for South Side business owners. “We’re talking about people literally working a full-time job, supporting themselves and their family while still pursuing this dream of opening a business,” she says. “And they’re doing it out of their own physical pocket.”

McPherson, a San Francisco Chronicle 2017 Rising Star Chef, says it was tough getting a job in the restaurant industry after culinary school. “I came into a white, male-dominated field and I was a young, black woman that wasn’t given a chance. My first opportunity was from another black woman and I worked in her restaurant.” Access to a solid professional network, including mentors, is absolutely as vital as access to capital — social capital is another part of the ecosystem, and can be a bridge to resources necessary for growth. But without the right connections, strong networks may be hard to plug into, and exclusion from these networks can have a stifling effect on one’s career.

McPherson has steadily established a solid network over the years. Now, she’s envisioning what her post-pandemic future will look like, including a possible alliance with other women chef-owners. “We’re talking about collectively developing our own restaurant group, in a sense, where we can build a fund for each member, build benefits for our employees, and build career opportunities,” she says.

In coming weeks and months, people in many industries will be taking stock of what could have been done better. But for now, McPherson’s most pressing need is capital to be able to restart.

Studies show that African-American communities were hit hardest by the Great Recession. According to the Social Science Research Council, black households lost 40 percent of wealth during the recession and have not recovered, but white households did. Unemployment caused by the recession disproportionately affected black women, a double-edged sword for many of whom worked lower-wage jobs that relied on tips. The costs of these disparities are far reaching. Six years after a defunct grocery chain shut its doors, creating a food desert in the Chicago South Side neighborhood of South Shore, a new grocery store finally opened — just last December — a few months before the pandemic.

Black communities are undervalued. “Mom-and-pop,” a term of endearment that acknowledges the fortitude and nobility in owning a small business, is rarely applied to black-owned businesses. Racial discrimination and biased perceptions of black-owned restaurants in black communities costs them billions of dollars in lost revenue. Disinvestment in these communities sets the landscape for quick-service restaurant chains to flourish, as professor Marcia Chatelain eloquently lays out in Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, all of which presents added pressure for the competing independent restaurant owners, whose margins are already miniscule.

“We’re truly hanging on by a thin thread,” Shelton says. She encourages local legislators to call on neighborhood restaurants and caterers to feed people who are food insecure, as well as individuals at the 3,000-patient field hospital erected at McCormick Place, the Chicago convention center that already houses Shelton’s now-closed second location. Meanwhile, Shelton regularly delivers meals to the ER staff at a neighboring hospital, paid for out of her own pocket.

Disparities in restaurants are emblematic of the nation. Indicators show that African-American communities are hit the hardest by COVID-19. ProPublica sums it up: “Environmental, economic, and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes.” And a lack of access to quality health care means the novel coronavirus has the potential to disproportionately decimate black communities, and the independent restaurants within them, if adequate support is not provided.

History shows us that the most vulnerable are left behind, and a similar pattern will likely occur post-pandemic. “The difference is the ability to be able to bounce back,” says Build Bronzeville’s Amos. When the pandemic hit, her organization swiftly aligned with other South Side organizations to urgently deliver vital information to small-business owners through grassroots efforts. “This is not a drill. Now is the time for all of us who want to be resource providers and boil it down for people,” Amos says.

Recognizing that communities with the most funding will have the greatest chance for survival, Amos leverages her relationships and personally calls and sends texts to restaurateurs conveying time-sensitive information like grant deadlines — she has become a lifeline for vulnerable small-business owners during this critical time. Amos has also extended assistance to Dining at a Distance, a delivery and takeout directory, after noticing its site had robust coverage of hot spots in the city, but little representation of South Side restaurants. Amos became a link and added a slew of South Side restaurants to the platform, noting that consumer-facing exposure is urgently needed. “A grim reality is that we have to capture these dining-out dollars now,” she says, “because there will come a point where people will stop ordering out because it just won’t be fiscally responsible for them to do so.”

As we envision a new path for the hospitality industry, black women must be central to the conversation: Their journeys hold wisdom that is widely absent from in-depth studies and data. And there’s no better industry to lead change than one known for breaking bread.

To support her community and staff, VanTrece has launched a pay-what-you-can menu at Twisted Soul, thinking of the model as a fundraiser of sorts. “This is a whole new pricing structure. You’re not pricing to pay the bills and pay the rent,” says VanTrece, whose landlord told her she wouldn’t have to pay a late fee on her rent, which is $10,000 a month. In addition to cashing in her credit card points for gift cards for her staff, she’s turned her restaurant into a hub where they can quickly grab necessities like a hot meal and toilet paper. It’s a service most of her team participates in. “But then I have some that are just scared,” she says. “They don’t want to come and I can’t blame them.”

On a recent Friday, a carryout fish fry was on VanTrece’s menu, a reminder of the ones she grew up going to during better days. She looks to the past for guidance often. “At Cast Iron, we always talked about the strength and the tenacity of our forefathers, and I’m calling upon that strength now to keep me putting one foot in front of the other, because there are times I just want to roll over,” she says. “And I can’t do that. I fought to get this far and I’m going to continue to fight through this.”

Angela Burke is a food writer and the creator of Black Food & Beverage, a site that amplifies the voices of black food and beverage professionals. Shannon Wright is an illustrator and cartoonist based out of Richmond, Virginia.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3bi4741 https://ift.tt/3bj5Juk

History shows us that the novel coronavirus will impact black women restaurateurs, and their businesses, much harder

Before the pandemic, our nation was in the early stages of battling an epidemic that plagued our beloved hospitality industry: the biased structural policies, born out of our country’s legacy of racism that guaranteed that black Americans would continuously work at a deficit. Painfully honest conversations — dissecting the ways in which decades of systematic racial and gender inequality festered in the industry — had finally begun to gain traction in on- and offline spaces. But, collectively, we’d barely broken through the dysfunctional infrastructure that allowed certain groups to fail harder and faster when COVID-19 struck.

Chef Deborah VanTrece was ringing the alarm prior to the coronavirus pandemic. She regularly brought discussions of industry inequality to the table through her dinner-and-conversation series that centers black women in hospitality. “It was something that we had just started talking about at Cast Iron Chronicles, and a lot of other chefs were talking about it,” says VanTrece, owner of Twisted Soul Cookhouse & Pours in Atlanta. “But the conversation wasn’t finished. It still isn’t.”

“As much as we’ve accomplished, I still feel isolated and that I am by myself. I don’t think any of us should feel that way. We should be checking on each other. It’s like [coronavirus] happened and every man for himself,” VanTrece says. “And when I think about it, we were pretty much like that in the first place; that’s why it’s so easy for it to continue now.” Isolation has become a theme in our shared new normal of stay-at-home orders, but what VanTrece is describing is a sentiment long echoed by black women in the industry. Yet seeing the divide continue during these times is heartbreaking for VanTrece. “If we were ever needing to be one, it’s now. We need to be one.”

Black and brown voices are largely excluded from overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry

As we grapple with lives lost and the magnitude of devastation caused by novel coronavirus, accountability and transparency seem to be overshadowed by crisis-led pivots while we brace ourselves for what’s to come. And yet again, black and brown voices are largely excluded from policymaking and overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry. In the face of this pandemic, some may say the pursuit of equality has been railroaded, maybe even understandably so. Others see the crisis as a hopeful confirmation that institutional change is inevitable. Because if not now, when?

In order to know where we are going, we have to understand where we’ve been. Black restaurant owners, black women especially, are in a more precarious position from the get-go. According to the latest figures, from 2017, black women were paid 61 cents for every dollar paid to their white male counterparts, making wealth generation much more difficult. And while one in six restaurant workers live below the poverty line, African Americans are paid the least. Access to capital has been a steady barrier of entry, especially for black women. Black- and brown-owned businesses are three times as likely to be denied loans, and those that are approved often receive lower loan amounts and pay higher interest rates. For a population more likely to rent than other demographics, offering up real estate as collateral for traditional loans isn’t an option. And even for those who own a home, the lasting effects of redlining, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, and low home valuations are palpable.

In other words, the wealth gap, combined with a lack of access to traditional loans and investors for start-up capital, puts black women at a disadvantage before they even open the doors of their restaurants. “A lot of us have had to build our businesses from scratch, and that may be through personal savings and loans, through family members, credit cards, or we have refinanced our homes,” says chef Evelyn Shelton, owner of Evelyn’s Food Love, a cafe serving comfort food in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood. “We are in uniquely different positions when we start, which makes where we are now even more difficult.”

In the East Bay, chef Fernay McPherson, owner of Minnie Bell’s Soul Movement, a food truck turned brick-and-mortar now located in the Emeryville Public Market food hall, is offering a limited carryout menu in an effort to keep her staff afloat, noting that some are single parents. “I was a single mother, so it’s a lot to take in when you’re thinking, ‘How am I going to feed my child? How am I going to make rent?’” During the Great Recession, McPherson was laid off and had to short-sell her home. She started Minnie Bell’s in 2009, as a catering company, while also working full-time as a transit operator in San Francisco. “It was hard being a mom, driving a bus, and trying to operate a business. It was a lot on me. And my decision was me. To work for me.”

Working multiple jobs is a necessary for many entrepreneurs whose bootstraps are shorter to begin with, says Lauren Amos, director of small-business development at Build Bronzeville, a Chicago incubator that advocates for South Side business owners. “We’re talking about people literally working a full-time job, supporting themselves and their family while still pursuing this dream of opening a business,” she says. “And they’re doing it out of their own physical pocket.”

McPherson, a San Francisco Chronicle 2017 Rising Star Chef, says it was tough getting a job in the restaurant industry after culinary school. “I came into a white, male-dominated field and I was a young, black woman that wasn’t given a chance. My first opportunity was from another black woman and I worked in her restaurant.” Access to a solid professional network, including mentors, is absolutely as vital as access to capital — social capital is another part of the ecosystem, and can be a bridge to resources necessary for growth. But without the right connections, strong networks may be hard to plug into, and exclusion from these networks can have a stifling effect on one’s career.

McPherson has steadily established a solid network over the years. Now, she’s envisioning what her post-pandemic future will look like, including a possible alliance with other women chef-owners. “We’re talking about collectively developing our own restaurant group, in a sense, where we can build a fund for each member, build benefits for our employees, and build career opportunities,” she says.

In coming weeks and months, people in many industries will be taking stock of what could have been done better. But for now, McPherson’s most pressing need is capital to be able to restart.

Studies show that African-American communities were hit hardest by the Great Recession. According to the Social Science Research Council, black households lost 40 percent of wealth during the recession and have not recovered, but white households did. Unemployment caused by the recession disproportionately affected black women, a double-edged sword for many of whom worked lower-wage jobs that relied on tips. The costs of these disparities are far reaching. Six years after a defunct grocery chain shut its doors, creating a food desert in the Chicago South Side neighborhood of South Shore, a new grocery store finally opened — just last December — a few months before the pandemic.

Black communities are undervalued. “Mom-and-pop,” a term of endearment that acknowledges the fortitude and nobility in owning a small business, is rarely applied to black-owned businesses. Racial discrimination and biased perceptions of black-owned restaurants in black communities costs them billions of dollars in lost revenue. Disinvestment in these communities sets the landscape for quick-service restaurant chains to flourish, as professor Marcia Chatelain eloquently lays out in Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, all of which presents added pressure for the competing independent restaurant owners, whose margins are already miniscule.

“We’re truly hanging on by a thin thread,” Shelton says. She encourages local legislators to call on neighborhood restaurants and caterers to feed people who are food insecure, as well as individuals at the 3,000-patient field hospital erected at McCormick Place, the Chicago convention center that already houses Shelton’s now-closed second location. Meanwhile, Shelton regularly delivers meals to the ER staff at a neighboring hospital, paid for out of her own pocket.

Disparities in restaurants are emblematic of the nation. Indicators show that African-American communities are hit the hardest by COVID-19. ProPublica sums it up: “Environmental, economic, and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes.” And a lack of access to quality health care means the novel coronavirus has the potential to disproportionately decimate black communities, and the independent restaurants within them, if adequate support is not provided.

History shows us that the most vulnerable are left behind, and a similar pattern will likely occur post-pandemic. “The difference is the ability to be able to bounce back,” says Build Bronzeville’s Amos. When the pandemic hit, her organization swiftly aligned with other South Side organizations to urgently deliver vital information to small-business owners through grassroots efforts. “This is not a drill. Now is the time for all of us who want to be resource providers and boil it down for people,” Amos says.

Recognizing that communities with the most funding will have the greatest chance for survival, Amos leverages her relationships and personally calls and sends texts to restaurateurs conveying time-sensitive information like grant deadlines — she has become a lifeline for vulnerable small-business owners during this critical time. Amos has also extended assistance to Dining at a Distance, a delivery and takeout directory, after noticing its site had robust coverage of hot spots in the city, but little representation of South Side restaurants. Amos became a link and added a slew of South Side restaurants to the platform, noting that consumer-facing exposure is urgently needed. “A grim reality is that we have to capture these dining-out dollars now,” she says, “because there will come a point where people will stop ordering out because it just won’t be fiscally responsible for them to do so.”

As we envision a new path for the hospitality industry, black women must be central to the conversation: Their journeys hold wisdom that is widely absent from in-depth studies and data. And there’s no better industry to lead change than one known for breaking bread.

To support her community and staff, VanTrece has launched a pay-what-you-can menu at Twisted Soul, thinking of the model as a fundraiser of sorts. “This is a whole new pricing structure. You’re not pricing to pay the bills and pay the rent,” says VanTrece, whose landlord told her she wouldn’t have to pay a late fee on her rent, which is $10,000 a month. In addition to cashing in her credit card points for gift cards for her staff, she’s turned her restaurant into a hub where they can quickly grab necessities like a hot meal and toilet paper. It’s a service most of her team participates in. “But then I have some that are just scared,” she says. “They don’t want to come and I can’t blame them.”

On a recent Friday, a carryout fish fry was on VanTrece’s menu, a reminder of the ones she grew up going to during better days. She looks to the past for guidance often. “At Cast Iron, we always talked about the strength and the tenacity of our forefathers, and I’m calling upon that strength now to keep me putting one foot in front of the other, because there are times I just want to roll over,” she says. “And I can’t do that. I fought to get this far and I’m going to continue to fight through this.”

Angela Burke is a food writer and the creator of Black Food & Beverage, a site that amplifies the voices of black food and beverage professionals. Shannon Wright is an illustrator and cartoonist based out of Richmond, Virginia.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3bi4741 via Blogger https://ift.tt/2RKiM0b

0 notes

Quote

History shows us that the novel coronavirus will impact black women restaurateurs, and their businesses, much harder Before the pandemic, our nation was in the early stages of battling an epidemic that plagued our beloved hospitality industry: the biased structural policies, born out of our country’s legacy of racism that guaranteed that black Americans would continuously work at a deficit. Painfully honest conversations — dissecting the ways in which decades of systematic racial and gender inequality festered in the industry — had finally begun to gain traction in on- and offline spaces. But, collectively, we’d barely broken through the dysfunctional infrastructure that allowed certain groups to fail harder and faster when COVID-19 struck. Chef Deborah VanTrece was ringing the alarm prior to the coronavirus pandemic. She regularly brought discussions of industry inequality to the table through her dinner-and-conversation series that centers black women in hospitality. “It was something that we had just started talking about at Cast Iron Chronicles, and a lot of other chefs were talking about it,” says VanTrece, owner of Twisted Soul Cookhouse & Pours in Atlanta. “But the conversation wasn’t finished. It still isn’t.” “As much as we’ve accomplished, I still feel isolated and that I am by myself. I don’t think any of us should feel that way. We should be checking on each other. It’s like [coronavirus] happened and every man for himself,” VanTrece says. “And when I think about it, we were pretty much like that in the first place; that’s why it’s so easy for it to continue now.” Isolation has become a theme in our shared new normal of stay-at-home orders, but what VanTrece is describing is a sentiment long echoed by black women in the industry. Yet seeing the divide continue during these times is heartbreaking for VanTrece. “If we were ever needing to be one, it’s now. We need to be one.” Black and brown voices are largely excluded from overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry As we grapple with lives lost and the magnitude of devastation caused by novel coronavirus, accountability and transparency seem to be overshadowed by crisis-led pivots while we brace ourselves for what’s to come. And yet again, black and brown voices are largely excluded from policymaking and overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry. In the face of this pandemic, some may say the pursuit of equality has been railroaded, maybe even understandably so. Others see the crisis as a hopeful confirmation that institutional change is inevitable. Because if not now, when? In order to know where we are going, we have to understand where we’ve been. Black restaurant owners, black women especially, are in a more precarious position from the get-go. According to the latest figures, from 2017, black women were paid 61 cents for every dollar paid to their white male counterparts, making wealth generation much more difficult. And while one in six restaurant workers live below the poverty line, African Americans are paid the least. Access to capital has been a steady barrier of entry, especially for black women. Black- and brown-owned businesses are three times as likely to be denied loans, and those that are approved often receive lower loan amounts and pay higher interest rates. For a population more likely to rent than other demographics, offering up real estate as collateral for traditional loans isn’t an option. And even for those who own a home, the lasting effects of redlining, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, and low home valuations are palpable. In other words, the wealth gap, combined with a lack of access to traditional loans and investors for start-up capital, puts black women at a disadvantage before they even open the doors of their restaurants. “A lot of us have had to build our businesses from scratch, and that may be through personal savings and loans, through family members, credit cards, or we have refinanced our homes,” says chef Evelyn Shelton, owner of Evelyn’s Food Love, a cafe serving comfort food in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood. “We are in uniquely different positions when we start, which makes where we are now even more difficult.” In the East Bay, chef Fernay McPherson, owner of Minnie Bell’s Soul Movement, a food truck turned brick-and-mortar now located in the Emeryville Public Market food hall, is offering a limited carryout menu in an effort to keep her staff afloat, noting that some are single parents. “I was a single mother, so it’s a lot to take in when you’re thinking, ‘How am I going to feed my child? How am I going to make rent?’” During the Great Recession, McPherson was laid off and had to short-sell her home. She started Minnie Bell’s in 2009, as a catering company, while also working full-time as a transit operator in San Francisco. “It was hard being a mom, driving a bus, and trying to operate a business. It was a lot on me. And my decision was me. To work for me.” Working multiple jobs is a necessary for many entrepreneurs whose bootstraps are shorter to begin with, says Lauren Amos, director of small-business development at Build Bronzeville, a Chicago incubator that advocates for South Side business owners. “We’re talking about people literally working a full-time job, supporting themselves and their family while still pursuing this dream of opening a business,” she says. “And they’re doing it out of their own physical pocket.” McPherson, a San Francisco Chronicle 2017 Rising Star Chef, says it was tough getting a job in the restaurant industry after culinary school. “I came into a white, male-dominated field and I was a young, black woman that wasn’t given a chance. My first opportunity was from another black woman and I worked in her restaurant.” Access to a solid professional network, including mentors, is absolutely as vital as access to capital — social capital is another part of the ecosystem, and can be a bridge to resources necessary for growth. But without the right connections, strong networks may be hard to plug into, and exclusion from these networks can have a stifling effect on one’s career. McPherson has steadily established a solid network over the years. Now, she’s envisioning what her post-pandemic future will look like, including a possible alliance with other women chef-owners. “We’re talking about collectively developing our own restaurant group, in a sense, where we can build a fund for each member, build benefits for our employees, and build career opportunities,” she says. In coming weeks and months, people in many industries will be taking stock of what could have been done better. But for now, McPherson’s most pressing need is capital to be able to restart. Studies show that African-American communities were hit hardest by the Great Recession. According to the Social Science Research Council, black households lost 40 percent of wealth during the recession and have not recovered, but white households did. Unemployment caused by the recession disproportionately affected black women, a double-edged sword for many of whom worked lower-wage jobs that relied on tips. The costs of these disparities are far reaching. Six years after a defunct grocery chain shut its doors, creating a food desert in the Chicago South Side neighborhood of South Shore, a new grocery store finally opened — just last December — a few months before the pandemic. Black communities are undervalued. “Mom-and-pop,” a term of endearment that acknowledges the fortitude and nobility in owning a small business, is rarely applied to black-owned businesses. Racial discrimination and biased perceptions of black-owned restaurants in black communities costs them billions of dollars in lost revenue. Disinvestment in these communities sets the landscape for quick-service restaurant chains to flourish, as professor Marcia Chatelain eloquently lays out in Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, all of which presents added pressure for the competing independent restaurant owners, whose margins are already miniscule. “We’re truly hanging on by a thin thread,” Shelton says. She encourages local legislators to call on neighborhood restaurants and caterers to feed people who are food insecure, as well as individuals at the 3,000-patient field hospital erected at McCormick Place, the Chicago convention center that already houses Shelton’s now-closed second location. Meanwhile, Shelton regularly delivers meals to the ER staff at a neighboring hospital, paid for out of her own pocket. Disparities in restaurants are emblematic of the nation. Indicators show that African-American communities are hit the hardest by COVID-19. ProPublica sums it up: “Environmental, economic, and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes.” And a lack of access to quality health care means the novel coronavirus has the potential to disproportionately decimate black communities, and the independent restaurants within them, if adequate support is not provided. History shows us that the most vulnerable are left behind, and a similar pattern will likely occur post-pandemic. “The difference is the ability to be able to bounce back,” says Build Bronzeville’s Amos. When the pandemic hit, her organization swiftly aligned with other South Side organizations to urgently deliver vital information to small-business owners through grassroots efforts. “This is not a drill. Now is the time for all of us who want to be resource providers and boil it down for people,” Amos says. Recognizing that communities with the most funding will have the greatest chance for survival, Amos leverages her relationships and personally calls and sends texts to restaurateurs conveying time-sensitive information like grant deadlines — she has become a lifeline for vulnerable small-business owners during this critical time. Amos has also extended assistance to Dining at a Distance, a delivery and takeout directory, after noticing its site had robust coverage of hot spots in the city, but little representation of South Side restaurants. Amos became a link and added a slew of South Side restaurants to the platform, noting that consumer-facing exposure is urgently needed. “A grim reality is that we have to capture these dining-out dollars now,” she says, “because there will come a point where people will stop ordering out because it just won’t be fiscally responsible for them to do so.” As we envision a new path for the hospitality industry, black women must be central to the conversation: Their journeys hold wisdom that is widely absent from in-depth studies and data. And there’s no better industry to lead change than one known for breaking bread. To support her community and staff, VanTrece has launched a pay-what-you-can menu at Twisted Soul, thinking of the model as a fundraiser of sorts. “This is a whole new pricing structure. You’re not pricing to pay the bills and pay the rent,” says VanTrece, whose landlord told her she wouldn’t have to pay a late fee on her rent, which is $10,000 a month. In addition to cashing in her credit card points for gift cards for her staff, she’s turned her restaurant into a hub where they can quickly grab necessities like a hot meal and toilet paper. It’s a service most of her team participates in. “But then I have some that are just scared,” she says. “They don’t want to come and I can’t blame them.” On a recent Friday, a carryout fish fry was on VanTrece’s menu, a reminder of the ones she grew up going to during better days. She looks to the past for guidance often. “At Cast Iron, we always talked about the strength and the tenacity of our forefathers, and I’m calling upon that strength now to keep me putting one foot in front of the other, because there are times I just want to roll over,” she says. “And I can’t do that. I fought to get this far and I’m going to continue to fight through this.” Angela Burke is a food writer and the creator of Black Food & Beverage, a site that amplifies the voices of black food and beverage professionals. Shannon Wright is an illustrator and cartoonist based out of Richmond, Virginia. from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3bi4741

http://easyfoodnetwork.blogspot.com/2020/04/its-time-for-hospitality-industry-to.html

0 notes