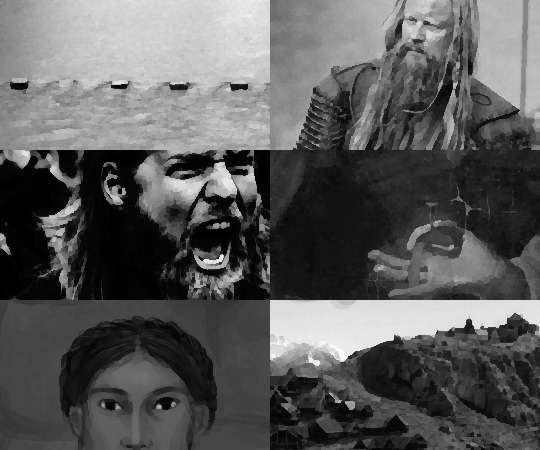

#the stepping-stones of the river isen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

THE STEPPING-STONES OF THE RIVER ISEN

When a young Dunlending woman appears at the Fords of Isen, Erkenbrand, Marshal of the West-mark, is caught in a decades-old secret that shakes Éomer King to his core.

part five (2363 words) of five | part one | part two | part three | part four | on AO3

A/N: Here’s the last part of the first story in the little saga. Hope you’ve enjoyed it! More to come soon xoxo

Gwir rushed through the corridors, skull throbbing. Everyone she passed leapt aside as soon as they saw her. Servants, she imagined, because any soldier or lord would have stopped her by now.

When she finally found her way back to the main hall, a few soldiers clustered near the dais steps spotted her. One gave a shout and started towards her. Gwir raced to the heavy doors; thankfully, one was cracked open. She slipped through and ran down the front stairs. The guards on the terrace leapt to their feet; Gwir didn’t spare them a glance. She ran down the stairs, eyes stinging.

“Halt!” one of the guards shouted.

Gwir skidded to a stop and twisted around. The two men drew their swords as they hurried to the stairs, and she shook her head. No! She turned and sprinted past the stream at the foot of Meduseld and down the road through Edoras. Everywhere she looked, tall blond Strawheads gasped and cried out at the sight of her. Gwir clenched her teeth and ran on, her skull still throbbing with every loud heartbeat.

She ran right past Erkenbrand and Elswide’s daughter’s house. After Ealhwyn’s reaction, she should have known better than to let herself be cornered into meeting with the king, no matter what Erkenbrand said. If the child of two people like Erkenbrand and Elswide could be so unkind, there was no hope for her here at all.

And she had hoped. She didn’t even realize it until now, while running down the hill to the city gates. For some reason, she had hoped that the Strawheads wouldn’t be as horrible as Ketheric said. Gwir knew little of her father, but she knew that he had been kind to her mother. She’d hoped his son would share his decency. But she had been stupid.

Not anymore.

Gwir threw a glance over her shoulder as her feet pounded into the packed dirt. There was no sign of any pursuers, although with the turns in the road there was no guarantee of safety until she was gone.

When she made it in sight of the gate, she slowed to a brisk walk. Her breath came heavily, and she finally reached up to feel the back of her head. Blood stuck to her fingers, and she winced.

The guards here had no notion of her flight from the great hall. One recognized her from earlier.

“Happy to see the back of you,” he called down from his watchpost. His companions laughed.

Gwir said nothing. She only walked quickly through the gate, head held straight and her bloody fingers buried in her crimson belt.

Only after the gate had shut behind her did she remember her satchel, abandoned in a tiny storeroom in Meduseld where she had changed into her dress. She paused. It took a great effort not to turn around. She had nothing, nothing at all now.

Gwir turned towards the setting sun and began to walk.

---

They found her before night had fallen.

When she’d first heard the horses, she’d unwound her red belt and wrapped it tight around her dark hair. She’d kept her head down and stepped off of the road, but the party halted not far behind her.

Gwir’s shoulders rose up to her ears and she kept walking. One of the riders clicked his tongue; a horse drew forward to walk at her side. She peeked up at the rider. It was Erkenbrand’s guard, the one she’d ridden with before. Goduin, that was his name.

Goduin was looking down at her with a frown. “Girl, we were worried you got yourself hurt,” he said.

At that, Gwir halted and spun to stare up at Goduin, who easily pulled his horse up short. “I didn’t hurt myself,” she spat. “Your king did it to me himself!”

“What—no,” he interrupted himself. “I am not supposed to speak of it. I’m just supposed to bring you back.” He reached out a hand to her. “Come on, girl. Come.”

Gwir shook her head. “You think I will go back there? When everyone jumps and screams at the sight of me? No thank you.” She stalked on. Goduin groaned and urged his horse forward and across her path. She had to stop.

“I do not want to force you,” he said, quietly. “But if you do not come willingly, I will. Or my companions will. And all of them are strangers to you.”

She glanced behind her. The two guards on horseback were out of earshot, but she could tell even in the dusk that they were strangers.

“Your king made me bleed,” she said to Goduin. “He struck me and stole—” She reached for the cord around her neck, the cord that wasn’t there. Her neck was bare without it. “I do not want to go back to his hall.”

“You need not,” Goduin promised. “I am taking you to Mistress Ealhwyn’s. With her permission.”

Gwir blinked. That was unexpected.

“Marshal Erkenbrand was worried,” he continued. “Whatever happened in Meduseld, you are under his protection now. I swear to you that you will be safe in his daughter’s house.”

She sighed. “I don’t want to be safe. I just want to be gone from here.”

“Gwir, if you go walking down this road alone, the next soldiers you meet will cut you down.”

Goduin had never said her name before. Gwir couldn’t even remember if he’d ever spoken in Westron before. Was that why Erkenbrand had sent him? For his Westron? Or was it because she knew him?

“Come on,” he urged. Again he reached down to her, and she sighed and let him pull her up before him. She sat sideways in front of him; in her dress, she couldn’t have ridden normally anyway. Goduin secured an arm around her and maneuvered his horse around.

Gwir clutched at the horse’s mane as Goduin spurred them back towards Edoras. The last rays of the evening sun glinted on Meduseld’s golden roof, and Gwir squeezed shut her eyes.

She did not open her eyes until they had stopped.

---

A baby’s cry pierced through Gwir’s dreamless sleep; she jerked awake with a gasp.

She was asleep on a straw pallet again, although this time the floor was wooden slats, not hard stone. And she was not guarded by anyone here. Elswide had apparently convinced Ealhwyn of her trustworthiness, for she had been put in the front room along with Eni, Ealhwyn’s young son, who had been displaced by his grandparents.

Eni grumbled in his sleep but was not roused by his sister’s squalls. The baby cried on, but no one came. Gwir sighed and pulled herself to her feet. She padded along in her white shift and picked the baby up from her crib. She was heavy! How old was this one supposed to be? Gwir had held three-year olds with less weight.

After a second of shocked silence, the baby began to wail again.

“Shh, shh.” Gwir hummed a lullaby and rocked the baby gently against her shoulder. The baby simmered down fairly quickly. Gwir was surprised, but she kept rocking herself back and forth.

Hurried heavy steps made Gwir spin around, and she blanched. Ealhwyn was frozen a few feet away, staring at Gwir with frightened eyes and an arm across her swollen belly. Gwir extended her arms just enough for Ealhwyn to understand the gesture. She hesitated but soon came forward and took her daughter from Gwir’s arms. Gwir stepped back at once.

“Thank you,” Ealhwyn whispered. Even her whisper seemed fearful.

Gwir went back to bed.

---

Over morning tea, Gwir begged Elswide to let her go home.

“You’d be killed, Gwir,” Elswide said. She was sitting on a bench near the fire pit holding a cup of tea. She took a delicate sip. “Until Erkenbrand can guarantee your safe return, I do not want you wandering alone.”

Ealhwyn waddled out from her bedchamber, her belly leading the way. She looked about to pop. Gwir sincerely hoped she would be gone before the birth, but if she had to wait for Erkenbrand, she doubted her wish would be fulfilled.

“Gōdne morgen, Módor,” Ealhwyn said. She poured herself a cup of tea and sat heavily in the empty chair.

From her place leaning against the wall, Gwir waited for her own greeting, but none came. Were all hosts in the Mark so unwelcoming? Probably. She blew on her hot tea to cool it.

“How long will it be, lady?” Gwir asked Elswide. “I cannot stay here forever.”

Ealhwyn’s eyes widened at that. Elswide glanced at her daughter with an indulgent sigh.

“Of course not,” she said. “And yet I would have you safely home. You are our guest, and my duty to you extends beyond the walls of the Hornburg.”

“So I have to wait,” Gwir muttered.

She turned her cup between her hands. Erkenbrand and Ealhwyn’s husband had already left for Meduseld. The thought of Erkenbrand trying to convince his king that she should be left alive made her shudder. She reached for the scab on the back of her head, but pulled back her fingers before she could touch it. If she touched a scab, it would be open again before long. Best not to check it.

“What’s the matter?” Ealhwyn said in Westron.

“Nothing, lady,” Gwir responded automatically.

Ealhwyn frowned but did not press the point, and Gwir decided that the safest thing would be to wrap her hair as she had done last night. Soon enough, her dark hair was hidden under her red belt and the scab was untouchable. And now her tea was cool enough to drink.

Once she’d swallowed the last drop, Gwir wiped her mouth on the back of her hand. “Am I allowed to go out?”

Elswide rubbed her temple. “Into the garden only,” she instructed. “Do not speak to anyone. Don’t even look at them, if you can help it.”

“They will look at me whether I look back or not,” Gwir said.

“Do not even look at them,” Elswide stressed.

Gwir sighed. She wouldn’t have minded making a few faces if someone really did stare. But at least sitting in the garden would be better than this farcical family home.

She did not belong inside.

Elswide unlatched the door for her, and she slipped out, checking her makeshift turban. Her hand froze by her face.

There was a woman standing at the gate, a pale woman tall and beautiful with hair the color of gold. She wore a green velvet gown, finer even than those Elswide had worn at the Hornburg, and her belt was wrought with gold.

Gwir lowered her hand back to her side. She clutched her skirt. Should she bow? Should she run?

“Are you Gwir, daughter of Maderun?” the woman asked. Her voice was cool and clear; her Westron was perfect.

Gwir nodded dumbly. This must be the king’s sister, the wraith-killer. She did not look like a shieldmaiden, not with that dress. Although she held a satchel in one hand—Gwir’s satchel.

“I have your things,” the woman said. “May I enter?”

“I—” Gwir stopped. Elswide’s instructions silenced her. She bit her tongue and turned away, though she stared at the woman out of the corner of her eye. Although… Gwir could talk to Elswide. She went to knock on the door, and Elswide poked her head out after a moment. Gwir fumbled for words, her heart sinking as she realized what was coming.

“What is it?” Elswide asked.

“Someone wants to see you,” Gwir said weakly.

When Elswide saw who had come, she gasped and threw open the door.

“Lady Éowyn!”

“Westú hal, Lady Elswide,” Éowyn said. “May I come in?”

“Of course, we are honored,” Elswide said. She circled past Gwir to open the garden gate for her new guest. Gwir drew back, but Éowyn fixed her with a strong gaze.

“I beg you would join me inside,” Éowyn said. Her words were a request, but her tone was all command. Gwir dawdled for a minute, but in the end she followed the other women inside. She suspected that Elswide would drag her in if she didn’t come on her own.

Éowyn turned expectantly in her seat when Gwir nudged open the door with a creak. Her cool face tightened as she looked Gwir over. Ealhwyn was still (or perhaps back?) in her chair, Eni at her knee. Elswide stood on the other side of the table, next to an unshuttered window.

“Gwir,” Elswide said, “this is Lady Éowyn, sister to Éomer King.”

“I know,” Gwir managed. She pulled the door shut behind her and ducked her head. “My lady.”

Éowyn pursed her lips. “There are your things,” she said, nodding to the satchel by the door.

Gwir did not bend to go through it at once, though she was tempted. Instead, she looked Éowyn square in the eye and asked, “All my things?” The only thing she really wanted back was her birthright. Everything else could be replaced.

“Not all.” Éowyn paused and glanced at Elswide and Ealhwyn, who were watching the exchange warily. “Perhaps Gwir and I could speak in private. Mistress Ealhwyn, I do not wish to disturb you—”

“You couldn’t, my lady,” Ealhwyn said. She pushed herself up. “I will go with my mother to the market. Eni, come.”

Gwir’s stomach flipped; she grabbed the wall for support. She did not want to be alone with Éowyn. She did not want Elswide to leave her!

But Elswide picked up Coenberg, who had been playing on the floor, and settled her on her hip. The four of them were gone within a few minutes, and then Gwir was alone with Éowyn.

Gwir gulped. All of her memories from her meeting with the king flooded back, and her chin quivered until she clenched her teeth together. This was the wraith-killer, the woman who had ridden to war and slain the Witch-King. This was the sister of the man who had made her bleed.

Was Éowyn about to make her bleed too?

“Well,” said Éowyn. She fixed her eyes on Gwir once more. “Hello, sister.”

#becca writes#the stepping-stones of the river isen#rohan#dunlendings#tolkien fanfiction#across the fords

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lord of the Rings Rewrite

Based off the movies, extended edition, and Pippin has magic

Merry hits me through the tent, and I quickly duck under the material.

"Quickly!" Merry boosts me into the cart and I quickly sort through the fireworks. I hold up a medium green rocket, but Merry quickly shuts the idea down.

"No, no! The big one, big one!" he exclaims, looking this way, and that so we won't get caught. My head aches slightly as I hold up a big red rocket, shaped like a dragon's head. I'm about to put it down, when I see Merry's face. He wants this one, so I push aside the ache and jump out of the cart and into the tent. Merry and I set the rocket up, but I'm distracted as my ache returns at double the pain. I try to ignore it and light the fuse.

"Done," I say, pushing the rocket up. It falls onto Merry's chest.

"You're supposed to stick it in the ground!" Merry tells me, panicking as he pushes it back towards me.

"It is in the ground!" I respond, his panic infecting me. My head hurts worse, and I try to figure out the problem. I push it back.

"Outside!" Merry practically yells, pushing it back once again. The pain dulls. Oh. That was the problem. This is bad.

"It was your idea," I remind him. He does all the thinking for me.

Suddenly the firework goes off, pushing us away and blackening our faces. It takes some of the tent with it as it flies high above the party, forming a great big dragon of sparks. Everyone looks on in awe, but my head is telling me there's something wrong. I understand as the dragon turns back towards everyone, flies low to the ground and almost hits everyone before flying off once again and bursting into beautiful fireworks.

"That was good," Merry tells me. I agree, but I wanna say that we should leave now.

"Let's get another one," my voice says without my consent. I internally groan at my automatic idiocracy. I turn to run off, knowing that Merry will listen to my stupidity, when someone grabs my ear. I hear Merry exclaim as well, so at least we were both caught.

"Meriadoc Brandybuck," a familiar voice says, "and Peregrin Took. I might have known." Me and Merry look to see Gandalf. Fear threatens to choke me, but I try to hide it. Hopefully they'll pass it off for the punishment that's sure to come.

The punishment does come, in the form of washing all the dishes from the party. Which, considering the entire Shire came, is a lot of plates and silverware and cups and bowls.

Late into the night, the crowd begins to call out for Bilbo to give a speech. He complies, standing on a barrel to be seen by all.

"My dear Bagginses and Boffins," the mentioned cheer loudly, "Tooks and Brandybucks," Merry and I join in with our families, "Grubbs, Tubbs, Hornblowers," cheers from each as they're mentioned, "Bulgers, Bracegirdles, and Proudfoots." I hear someone call out "PROUDFEET!" followed by laughing from those around him.

"Today is my One Hundred and Eleventh birthday!"

"HAPPY BIRTHDAY!" choruses the crowd. Bilbo continues.

"Alas, eleventy-one years is far too short a time to live among such excellent and admirable hobbits. (cheers?) I don't know half of you half as well as I should like and I like less than half of you, half as well as you deserve." I think about this. So he doesn't know half of us as much as he'd like, and he likes less than half of us, and only half as much as we deserve. I see Gandalf smirk, and find a small mimicry move its way up my face. But I stop when I realize that no other Hobbits besides me understood. I'm supposed to be an idiot, so I adopt the same confused look as Merry.

"I, er, I have things to do." As the old Hobbit speaks, he reaches into one of his pockets. I notice a faint feeling of darkness as he takes something out of his pocket and holds it behind his back. The object glints the moment before it's hidden. "I've put this off for far too long. I regret to announce this is the End. I'm going now. I bid you all a very fond farewell. Goodbye." Bilbo smiles fondly at Frodo, while everyone looks curiously on. Then, quite suddenly, every Hobbit gasps. Every Hobbit but me. Bilbo seems awfully pleased with something he did and hops off the barrel and heads past everything towards his house. I see Gandalf take his pipe out of his mouth and scowl. I look at Merry, but he's just as stunned as all the others.

"What happened, Merry?" I ask. My friend looks at me, eyes wide.

"I don't know, Pippin. I don't know," he mutters. I furrow my brow as I try to think of what happened. Obviously, I was the only one not affected, and judging by what was going on, no one saw Bilbo head home. I watch the chaos and notice Gandalf heading after Bilbo, walking briskly, but somehow as unnoticed as the Hobbit himself.

"Come on!" Merry calls, and I turn to find him running off.

"Wait up," I call back, rushing after my friend.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

We found ourselves in the Green Dragon not that many days after Bilbo left. Apparently, he headed to live with the Elves. After many mugs of ale, Merry and I found ourselves on a table, singing and dancing away.

"Hey ho, to the bottle I go!

To heal my heart and drown my woe.

Rain may fall and wind may blow,

But there still be

many miles to go!

Sweet is the sound of the pouring rain,

and the stream that falls from hill to plain.

Better than rain or rippling brook-"

"Is a mug of beer inside this Took!"

I take over on the last line of the song, raising my half-pint in salute before taking a drink. Everyone around me cheers. It feels good to know that people think I'm good at something, even if it's not that great of a talent.

We walk out later that night, saying goodbye to Rosie on the way. We chuckle at the thought of what Sam would look like if he saw that. She's no more than a friend to us, but Sam's got the biggest fancy for her than anyone else I've seen.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

I can hear singing, like something from another world. I turn and see wood elves passing by. Some are riding on the finest steeds I've ever seen, while most walk, carrying lanterns and wearing pure, glowing robes. I hear talking amidst the singing, and look in the direction it comes from. Just as I see two small forms gazing at the procession, I fall into darkness.

"Smoke rises from the Mountain of Doom. The hour grows late and Gandalf the Grey rides to Isengard seeking my Council. For that is why you have come, is it not? My old friend." A wizard with long grey-white hair and beard and an all-white robe walks down the steps of a huge black tower. Gandalf walks over as he speaks and bows.

"Saruman," Gandalf says. So that is the wizard's name, though what a name it is. I feel the fear within me tremble. Unlike with Gandalf, this fear is real, instinctual, not from years of experience but from something primal, something dark.

I feel a shift, and then Saruman and Gandalf are walking near the tower.

"So the Ring of Power has been found," Saruman states. I shiver at the feeling that comes when he says this. But then I think. Ring of Power? I've heard stories, but nothing concrete.

"All these long years it was in The Shire under my very nose," Gandalf tells his fellow. I want to scream at Gandalf to not tell him, that this wizard is nothing good, but I know that it will be no use.

"And yet you did not have the wits to see it. Your love of the Halflings leaf has clearly slowed your mind." I frown. Many of my best ideas come from Old Toby.

"But we still have time. Time enough to counter Sauron if we act quickly," Gandalf hurriedly says. Sauron. The name sends more shivers down my spine.

"Time! What time do you think we have?" Saruman exclaims, a hint of anger in his voice. Another shift comes, and suddenly I'm inside the tower. I can feel the evil in it, thrumming, but not like the feeling in your chest when you hum. The sound of a war drum, or the noise right before some big monster roars and devours you whole.

"Sauron has regained much of his former strength." I turn and see Saruman and Gandalf still speaking.

"He cannot yet take physical form but his spirit has lost none of its potency. Concealed within his fortress, the Lord of Mordor sees all. His gaze pierces cloud, shadow, earth and flesh. You know of what I speak Gandalf. A great eye, lidless, wreathed in flame." My head begins to ache. The evil in here is so powerful, and the words, and Saruman, and the very tower echo with darkness.

"The Eye of Sauron." Gandalf seems to not feel the darkness surrounding him. Could he be a part of it? NO! I can feel his energy, bright and filled with goodness. I move closer until I'm standing right beside him, using his light as an anchor in this pitch black place. My fear becomes my safety.

"He is gathering all evil to him. Very soon he will have summoned an army great enough to launch an assault upon Middle Earth," Saruman continues, not sounding concerned about the Dark Lord of Mordor trying to kill everything in Middle Earth.

"You know this? How?" Gandalf questions.

"I have seen it," the dark wizard dressed in white answers. The two walk into a different room and I follow. A pedestal stands in the middle of the room, a black cloth covering what sits upon it. I feel pulled towards it, but my will to stay near Gandalf is greater.

"A palantir is a dangerous tool, Saruman."

"Why? Why should we fear to use it?" Saruman pulls the cloth off, revealing a globe, a sphere of black, cloudy glass.

"They are not all accounted for. The lost seeing stones. We do not know who else may be watching." Gandalf moves forward, covering the palantir back up. As he does, I sense a darkness flash through the stone. He must feel it as well, for the Grey Wizard pauses, his face one of realization.

"The hour is later than you think. Sauron's forces are already moving. The Nine have left Minas Morgul." Saruman sits back on his throne.

"The Nine!"

"They crossed the River Isen on Midsummer's Eve disguised as riders in black."

"They've reached The Shire?" The Shire? My head pounds now. I know, I know! That's home! That's where Merry, and Frodo, and Rosie, and Sam, and Mother and Father, and my sisters, and everyone!

"They will find the Ring and kill the one who carries it."

"Frodo." FRODO‽ SERIOUSLY, GANDALF‽ Of all the Hobbits in Hobbiton, it had to be one of my best friends! And then Gandalf the... the Fool goes and says his name! Every thought rushes in one way and out another as I stare between Gandalf and his traitorous kin.

"You did not seriously think that a hobbit could contend with the will of Sauron? There are none who can. Against the power of Mordor there can be no victory. We must join with him Gandalf. We must join with Sauron. It would be wise my friend." I make a slight grunt at the friend part. You'd have to be a fool or evil to be friends with someone this dark. And Gandalf isn't evil.

"Tell me. Friend... When did Saruman the Wise abandon reason for madness?" I internally cheer at the insult, but all possible celebration is wiped from me as Saruman throws the firework-making wizard across the room. As the two begin to fight, throwing each other everywhere, my vision fades.

"GANDALF!" I shout as it all goes black.

#lotr#pippin#merry#frodo#sam#gandalf#bilbo#peregrin took#meriadoc brandybuck#frodo baggins#samwise gamgee#saruman

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some more Lavellan Bros. Young Theo Lavellan ( @serphena ‘s oc) gets caught making some dumb choices with his friends, and Taren goes full big brother with helping him do some healthy teenage rebellion. Inspired by that time your older brother showed you how to properly roll a joint, or got you out of class just to hang, or covered for you when you came home from your first party.

(and by smoking pot down by the river ;) ) cw. for smoking something that is definitely an analogue for marijuana.

AO3 Link or read under the cut!

Dusk was falling over the camp. The clan had been settled into the area for almost a whole season already, and the scent of cooking vegetables lingered in the warm summer air. The fires for the evening were still lit, and the soft murmur of music could be heard on the breeze. Leaves and branches cracked underfoot as Theo and a few of his fellow young hunting apprentices stumbled out of the brush, laughing and shushing one another in the dark at the edge of camp.

Theo felt his head beginning to spin from pleasantly fogged to unsettlingly dizzy and focused on remaining upright. As he was concentrating on maintaining an awareness of his center of gravity, a voice and footsteps came out of the dark.

“Hey, what are you all doing back so late?” Called the voice of the irritated First.

Shit.

In a hushed scramble of swearing and “go!”, his friends scattered away from him, and Theo stumbled forward from the confusion directly into Taren’s path. He looked up, hoping that Taren couldn’t discern the redness in his eyes as he swayed in front of him in the dim light.

“Are you… never mind.” Taren sighed, turning to march Theo back toward the structure that housed the hunter apprentice beds.

“You missed dinner.” Taren told him flatly as they went, and Theo found himself needing to grab onto Taren’s arm in order to walk straight. Fenedhis, he was going to be in so much trouble for this.

“Just drink some water and go to sleep” Taren left him at his bed and shook his head, losing some of the annoyance in his voice as Theo stared at him in panic, “you’ll be fine.”

When Theo woke the next morning, his head was clear once more. And to his surprise, his excuses had been made with Isen, and when he arrived to train the Keeper was not waiting there to kick him out or take away his apprenticeship. He carried on with his tasks like it was a normal morning, checking on the equipment and visiting the halla, thanking the Creators for his luck. Then, midway through the day, and just before Isen would be taking him out to practice his shooting, Taren strode up to his mentor, gave some explanation with a polite little nod, and turned to summon him with a wave.

Theo left his bow and followed Taren away from the hunters’ camp and onto a forest path. He braced himself for an afternoon filled with lectures and scolding, as Taren ducked into the brush off of the path, following a thin trail overgrown with weeds toward the trickle of a small stream. Theo followed curiously, pushing and ducking awkwardly under branches as the path wound about and led down to a rocky ledge by a wider part of the river, backed by the trees of the forest.

Charcoal and ash were left in a circle of rocks by the water, and a group of large flat rocks were set around it like seats. Taren stepped forward and took a seat, motioning for Theo to follow.

“Just tell me how bad it is.” Theo muttered, leaning into a seat on another stone and slouching his head into his hands.

“What?”

“What did Keeper Deshanna say my punishment is? Just tell me, I don’t need you to lecture me too.” Theo groaned, muttering into his hands.

“I wouldn’t know, I didn’t tell her.” Taren replied in a casual tone, and Theo looked up to see him smirking from where he sat cross-legged on the wide bench-like stone laid by the firepit.

Taren turned his attention to a pouch he carried with him, pulling out a bundle of thin woody plants tipped with dark green leaves. He pulled out a small knife as well, and began to peel at the bark of the plants' stems, dropping the shavings into a neat pile on the stone.

“You can’t smoke it wet, that’s what will make you sick.” He explained with a knowing smile as he wrapped the prepared cuttings up and tucked them back into his pouch. He then pulled out another wrapped parcel of herbs, these ones dry, and a thin wooden pipe. Taren carefully pressed some of the finely ground herb into the little wooden contraption and flicked his fingers, while Theo watched in stunned silence.

“You know, the elders do this sometimes when we meet with other clans. There’s probably even a blessing for it.” He held out the pipe in offer, and Theo could smell the root in it burning sweetly, not at all cloudy and thick as it had been the night before.

Theo shrugged and took the pipe, inhaling carefully. The heat hit his throat and he coughed uncomfortably, choking a little on the air as he inhaled it. Taren chuckled and took the pipe back to inhale with a long, easy draw.

It took him a few tries, to Taren’s amusement, but Theo eventually managed to regulate his breaths to take the smoke slowly into his lungs, and exhale without choking. The sensation of lightheadedness was similar to what he had felt before, but it wasn’t accompanied by any dizziness or loss of focus. He felt relaxed, but also like some of his senses were made a little more keen. The lapping sounds of the river and the rustling of the leaves in the breeze stood out as pleasant reminders of the natural world around him, and brought him a smile.

“Why are you showing me this?” Theo finally asked as the contents of the pipe burned down. “I thought you never did anything wrong. Don’t you only care about the rules?” The shock and slight sarcasm in his voice didn’t feel unwarranted, even if Taren was apparently being more like his old, kind self for the moment. Lately all he had seemed to be was stern and stressed, and frankly, it had gotten annoying.

Taren shrugged, “I don’t get caught, there’s a difference.” He tapped the ashes out of the pipe and brushed them into the air to be carried off by the wind. He filled the pipe again and sighed before taking the first inhale, and released the smoke on his exhale in a long trail. “And I don’t just care about rules, idiot. I care about you.”

Theo took a deep breath of the smoke, feeling it properly now. It was still hot and mildly uncomfortable, and he figured he should let the effects settle a while before taking more, but the effects were pleasant. He rolled his eyes at Taren’s sentimentality even though it did touch him.

“I know.” He sighed, glad that it at least felt more like normal. “So what’s been the matter with you lately?”

Taren glanced away uncomfortably. “Bereth and Sulahnna are going to be bonded.” He admitted, taking the pipe back for his own long drag.

“Oh…” He knew that Taren was close with them both, and with Bereth that he had been more than that, But from the way Taren looked now, maybe he hadn’t realised just how much more.

“Yeah, well.” Taren frowned, rubbing at his eye after he passed the pipe back to Theo. Theo set it down beside him for the moment.

“I thought he was… I mean, you were…” Maybe Taren was only rubbing his eye because of the drying effect of the smoke, but he doubted it.

“Not anymore.” Taren shrugged unconvincingly.

“Dick.” Theo commented decisively.

“Theo, don’t. It isn’t like that.” Taren corrected him, but the comment had lightened his frown.

“Well you can do better, anyway.” He insisted, passing the pipe back to Taren.

"So it sounds like you'll be made a full fledged hunter in no time." Taren changed his tone with the subject, landing on something light and complimentary.

"I still have a lot to learn before Isen will let me join one of the real trips." Theo shrugged, but smiled a little at the words.

"So eager to leave?" Taren teased.

"Everyone I know is always away these days, even you." Theo took the pipe for another puff of the sweet smoke, leaning back to watch the breeze in the leaves above him. "It's weird when you're gone, Deshanna won't leave me alone."

"She just worries about you." Taren said, and Theo replied with an exaggerated groan. "I'm back for a while." Taren continued with a reassuring chuckle.

"Does that mean we can do this again?" Theo asked hopefully.

"Sounds like a good plan to me." Taren agreed, tapping the ashes out of the pipe once more. "But I'm not getting you out of anything else. Next time just tell me before you decide to do anything stupid."

#backstory stuff#my ocs#other people's ocs#my writing#taren lavellan#theo lavellan#lavellan bros#brothers#family#just bonding over our relationship probs and smoking pot by the river what#you know just regular summer passtimes#bros bein bros#dragon age fanfic#dragon age inquisition#clan lavellan#cw smoking#cw marijuana#kinda

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE STEPPING-STONES OF THE RIVER ISEN

When a young Dunlending woman appears at the Fords of Isen, Erkenbrand, Marshal of the West-mark, is caught in a decades-old secret that shakes Éomer King to his core.

part four (4157 words) of five | part one | part two | part three | on AO3

A/N: It’s always a challenge to write from the perspective of a well-defined character, but it’s so worth it! Hope you enjoy, let me know what you think, xoxo

Éomer tugged at his beard and paced in front of the desk. Éothain, his lieutenant, and Elfhelm, Marshal of the East-Mark, both stood nearby, their faces lighter now than they had been at the beginning of the harvest tally. The scribe dipped his quill in ink and looked expectantly at his king. When Éomer turned back to the scribe, it took a moment for Yffi’s silhouette against the wide window to come into focus.

“Yffi, write to King Elessar and to Imrahil of Dol Amroth,” Éomer instructed. “Tell them we are set for the winter thanks to their aid and a lucky harvest.” His jaw twitched; he swallowed. He ought to write himself, but his pride flagged at the empty thanks he could offer now. Yffi was far better with words than he, and the scribe was already bent over his parchment, scribbling away. “I will sign myself.”

“As you wish, lord,” Yffi said, still writing.

Éomer, Elfhelm, and Éothain drew away from the desk to door of the study.

“Based on Erkenbrand’s numbers, the West-mark will be harder to feed,” Elfhelm said. “But provisions can be moved.”

“And people, if need be,” Éothain added.

Éomer waved that away. “Enough Éorlingas have become refugees,” he said. “I want none of that.”

Elfhelm pursed his lips. “I’ll talk with Erkenbrand when he arrives. He should be here soon. He’ll know better than I if your wish is possible.”

“Béma willing, it will be,” Éothain said. He clapped Éomer’s arm. “Well, whether we need to relocate people or not, we will make it through this winter thanks to you.”

“And Gondor,” Éomer said darkly.

Éothain and Elfhelm exchanged a look.

“It’s the least they can do,” Éothain said. “We saved them, didn’t we?”

Éomer sighed. He waved them out with the scribe once Yffi had finished. The study door closed with its usual creak behind them, and Éomer sat down to browse Yffi’s work.

Yes, it was much better that Yffi had composed the letters. The scribe’s Westron was perfect. Éomer was no great writer, in terms of penmanship or style, and his stung pride would have screamed out of every sentence if he’d written to Aragorn and Imrahil himself.

Though his new friends did not begrudge him his pride. They were proud men themselves, and they understood. Neither envied his position; Éomer had understood that well enough. Yet they seemed confident that in time, Éomer would repay all of their help. Imrahil had mentioned the Mark’s famed horses; Aragorn had spoken of campaigns to the south and east.

But horses and war seemed paltry indeed compared with keeping his people from starving.

Éomer signed his name on Yffi’s letters.

He lit a match to melt his wax while the ink dried, and he read through Yffi’s compositions one more time. The man was a real marvel.

A knock at the door made Éomer look up. “Enter,” he called.

It was Irminric, Meduseld’s steward, and the man looked anxious enough that Éomer stood. But Irminric only bowed.

“Marshal Erkenbrand has arrived, lord,” Irminric said. He did not meet Éomer’s eyes. “He has brought a guest from the Hornburg.”

“Very good,” Éomer said, frowning. He sat back down. “Show them in.”

“The marshal wished for his guest to make themselves presentable after the ride. They will be in shortly,” Irminric said. At last he met his king’s eye, and Éomer saw how deeply unsettled he was.

“Who has come, Irminric?” Éomer demanded. The match burned down to his fingers, and Éomer hissed and blew it out.

Irminric quaked. “My lord, it is—”

“Westú Éomer hal,” Erkenbrand said loudly. He marched in from the hallway without preamble and gave Irminric such a look that the steward bowed at once and retreated. Erkenbrand bowed.

Éomer leaned forward on his desk. He could feel the damp ink under his palms and growled. Of all the—! “Who have you brought that has my steward so disquieted?”

“A Dunlending,” Erkenbrand said at once.

“What!” Éomer sprang back from his desk. “You are not serious. They are forbidden in these lands.”

But Erkenbrand was not joking. He only bowed. “I beg your leave, lord, but I felt you would wish to meet this one.” He stood and looked straight at Éomer. Unease lurked in Erkenbrand’s deep-set eyes, but he spoke firmly. “Her father is from the Mark.”

“Many Wild Men have blood from here,” Éomer said, “but that does not give them leave to enter the Riddermark.” He wiped his inky hands against his trousers. “You had no right to allow any to enter, much less bring one to my hall.”

Erkenbrand pressed his lips together unhappily. He was silent for some time. “You will understand when he meet her,” he said at last. “I cannot say more; it is not my place. But I beg that you receive her, that I might consider my duty to you fulfilled.” He bowed again and did not rise.

Éomer shook his head, though Erkenbrand’s face was to the ground and he could not see. This was beyond comprehension. What was his marshal thinking? Had the war affected him so badly? No, for Erkenbrand’s wife or Éomer’s own steward would have informed Éomer. And Erkenbrand had not seemed addled, only concerned. Perhaps it was worth hearing the man out. Finding someone to replace him right now would only mean more headaches.

“Very well,” Éomer said, though his voice was cold. “You may bring your… guest in. I will see her.”

The relief on Erkenbrand’s face was its own kind of reassurance, Éomer thought. He jogged out, leaving Éomer alone again.

And Éomer had thought that the harvest tally was going to be the hardest part of the day. He sighed and went to look over Yffi’s letters. His signatures weren’t smudged too badly to send, although Yffi would disagree. He folded the two letters and pressed the back of his ring into the hot wax seals. Better to get them sealed and out of sight before… Well, before.

Was he as mad as Erkenbrand?

Éomer ran a hand across his forehead and then remembered the ink. “Damn!” He rubbed the corner of his sleeve where he suspected the ink was. No telling what he looked like now, he supposed. There were no mirrors in the study.

Erkenbrand’s voice echoed in from the hall, and Éomer strained to hear.

“Buck up, girl,” his marshal said in Westron.

“You’re one to talk! You’re as nervous as I am!”

The girl sounded peevish; Éomer wondered if she looked as grumpy as she sounded. But why should she be upset? Was she not here by her own design?

Erkenbrand reappeared in the doorway. He paused when he saw Éomer. “Wait there,” he ordered, and the girl remained out of sight in the hall. In their own tongue, Erkenbrand said, “Here.” He passed Éomer a handkerchief and pointed to a spot on his face.

“Thank you,” Éomer said. After a minute of vigorous polishing, his forehead was apparently clear again, for Erkenbrand nodded and went back to the hall to bring in the girl.

Éomer steeled himself. The last time he had seen a Dunlending, it was at the Battle of the Hornburg, when his uncle had been king. Théoden had had the grace to be generous with his defeated enemies. Éomer was not sure if he had his uncle’s poise.

Erkenbrand came in first, and Éomer could see little of the girl behind his armored marshal.

“Lord, this is Gwir, daughter of Maderun,” Erkenbrand said in Westron. He bowed and stepped aside.

Gwir, daughter of Maderun stared at Éomer with the same dark, angled eyes as her mother’s people. She was scared out of her wits, though she was doing her best to conceal it.

At least she wasn’t a total idiot, Éomer thought. Only an idiot would be unafraid to show their face to their enemy’s king.

He studied the girl. She looked about the same age as his sister, so perhaps young woman would have done her more justice. Her hair was dark and braided around her head like a wreath, and her clothes were simple apart from a crimson belt slung above her hips. Her sleeveless overdress was crossed over itself in the robe-like Dunlendish style. Éomer’s lip curled. Yet her nose and mouth were short and straight, not unlike his own, and though darker than any Éorling, she was paler than any of her people that he had seen. And she had something of his people’s height, although she was short to his eyes.

“Gwir, here is Éomer King,” Erkenbrand continued. He nudged her shoulder and she dipped her upper body in a clumsy bow. Gray glinted in her dark hair.

“Lord,” Gwir said. She looked back up at him as she stood straight and ran her fingers across her nose and mouth. She turned to Erkenbrand. “Is he very like…?” she murmured.

“You have not here come to speak to my marshal,” Éomer said before Erkenbrand could answer. He did not care what she was asking; her question meant nothing to him. “You will address me. Why are you here?”

Gwir hesitated and glanced again at Erkenbrand. Éomer slapped his hand against the desk; she flinched and turned back to him. This time, she did not meet his eyes.

“My chief made me come,” she said. “Ketheric of Llowys craves your notice.”

“He cannot have it,” Éomer said, relieved. If this was all, then all of his worry was baseless. “Tell your chief his message and its messenger are displeasing to me.”

She stiffened. “I do not like his message either, but I would rather not have come. I do not deserve your derision, lord.”

“You flaunted the laws of my land when you stepped foot here,” Éomer said. He came around his desk and stood tall before her. He crossed his arms; such a display of his strength was more intimidation than she had expected, and she swallowed nervously. She had to tilt her head to meet his gaze. “You are lucky to be alive.”

“I have a right,” she retorted. She again ran a finger down her short straight nose. “My father…”

She trailed off and again looked at Erkenbrand. Irritation boiled in Éomer’s gut.

“I am king here,” he declared. “Look at me, not at my marshal. He is not your protector. You are safe only through my mercy.” She was still silent. Éomer held out one large fist, and she stepped back instinctively. “Do not try my patience. What right do you have? Your blood is as dark as your people’s.”

Gwir bristled at that. His insult gave her the resolve she needed, finally.

She pulled on the leather cord around her neck. Éomer had not noticed it tucked into her shirt before. Something shiny dangled on the end of it, but she pulled it over her head too fast for him to make it out. She clutched it to her chest, sighed, and held out her hand.

Éomer stared into her open palm. Gwir’s leather cord was strung through a silver ring. The ring was brightly polished; the cord dangled from her fingers. He stepped closer and squinted to make out the seal on the ring’s flat face. A rider rode through water atop a glorious steed. Éomer recognized the image at once—it depicted Éorl crossing the Anduin into the Fields of Celebrant.

This was the seal of Aldburg.

“Thief!” Éomer snatched the ring from her before Gwir could do more than open her mouth in shock. “You dare come here—”

“That is mine.” Her growl cut through his raised voice, but it did not abate his fury. She stepped forward, her whole body tight with tension. Her hands were open and trembling at her sides. She took another step.

Éomer squeezed his father’s seal in his fist and brandished his hand before her. “This is mine by right,” he hissed. “You have no claim to it.”

“It is mine!” Gwir flung herself at him and tried to pry his fingers open. Éomer’s eyes darkened with rage. “He put it on me with his own two hands!”

He saw red. With a shout and great force, he shoved Gwir away from him. She reeled back, dark eyes wide, and tumbled down. She banged her head against the stone doorframe and groaned. Erkenbrand leapt between them and pressed himself against his king before Éomer could swoop down and throttle her. Éomer knew, even in his furious haze, that fighting his marshal was a bad idea.

“Get out!” he bellowed. “Out!”

Gwir shot him a look of pure malice and pulled herself to her feet. She spat at Éomer’s boots, and he wrestled against Erkenbrand’s hold.

“Gwir!” Erkenbrand thundered. The marshal looked ready to throttle the girl himself, but he was still keeping his king back. “How dare you!”

“How dare you!” she cried. She backed up into the entryway and clutched the doorknob for support. Her braids and overdress were askew and her face was ashen. “You are more the thief!”

Éomer finally managed to shove past Erkenbrand. In the face of his naked rage Gwir retreated, slamming the door shut between them. Éomer paused in the face of this new obstacle. His heavy breathing was loud as his anger abated, but as soon as he saw Erkenbrand leaning against the desk, Éomer scowled again.

“You are mad,” he declared.

Erkenbrand stood straight and raised his eyebrows at his king. “I am not. You are the mad one here, lord,” he said. “That girl is not your enemy.”

“What is this, then?” Éomer challenged. He at last opened his fist to reveal his father’s seal. Erkenbrand hissed; the edge of the seal had bitten into Éomer’s skin. The silver ring was coated in blood.

“That is her birthright,” Erkenbrand said. He grabbed the inky kerchief from Éomer’s desk and passed it to his king. He caught Éomer’s eye and held it in his firm gaze. “She is who she claims to be. There is no lie, and she is no thief.”

Éomer shook his head and wiped his blood from the ring. He ignored the stinging in his palm and rubbed the seal until it shone again.

Why was Erkenbrand so sure of the Wild Woman’s story? It was ridiculous—so ridiculous that Éomer could hardly put her claim to words, even in his own mind. The lord of Aldburg… A Dunlending woman… It was far too ridiculous to consider.

And yet Erkenbrand, a man of considerable sense, seemed convinced. Gwir did not seem like a witch; she had not wormed her way into his mind by any mystical means. No, for some reason her story held weight with his marshal.

But why?

“How can you be so sure?” he asked at last. “How do you know she is not lying?”

Erkenbrand sighed heavily, and at last Éomer saw how exhausted the man was. Éomer sat back at his desk, which meant Erkenbrand could sit as well. The older man cast a grateful look at his king, though his gratitude soon darkened into gloom.

“I was there,” Erkenbrand said. “I was there when your father met Maderun.” He turned unhappy eyes back to Éomer. “The Dunlendings have schemed to lay stepping-stones across the river Isen for many years. Maderun was part of such an effort, and she fell in the river. Your father was leading a patrol along the river, and he rescued her from drowning.”

With effort, Éomer tried to think of it dispassionately. But he could not think of it without seeing Gwir’s face, and nothing in her face could have tempted him. He shuddered.

“Maderun was very beautiful,” Erkenbrand continued. “And she was not without charm.”

“Charm!” Éomer spat, disgusted. “No doubt she orchestrated the whole affair and laughed about it with her kinsmen.”

“No indeed,” Erkenbrand said. “For she was young, and she had almost drowned. She did not seem foolish enough to risk her life in pursuit of an enemy.”

So what made his father risk his life in pursuit of her? Éomer still could not grasp what had made his father accept the woman into his bed, but he was too disturbed to ask. Instead, he muttered, “Her daughter seems foolish enough for it.”

“No indeed,” Erkenbrand replied. He leaned forward with conviction. “Gwir has no death wish. She was forced here by her chief, who threatened her. She has submitted to my orders with no—well, with minimal complaint. And she passed on some useful information that confirmed what I had heard before about Dunlending chiefs, and where we might find our best allies to the west.” He paused and looked warily at Éomer. “I did not expect her introduction to go so poorly. I beg your pardon, lord. I only thought you would want to know.”

Éomer sighed. All things considered, he would have been far happier not knowing. Yet…

“She looks younger than I would have thought,” he said. “She does not look older than I am.”

“Béma…” Erkenbrand buried his face in his hand. “She is younger than you. She is twenty-five.”

Horror spread across Éomer face. “You mean,” he sputtered, “that not only did my father consort with the enemy, he betrayed his word to my mother?”

Erkenbrand scooted his chair back from Éomer and nodded glumly. “He did.”

“My father—”

Éomer had no words. He felt more betrayed now than when he realized Gríma’s treachery, than when Théodred had been killed, than when he discovered Éowyn lying as one dead in the Pelennor Fields. This was worse than all of that. The memory of his father had ever been a source of a comfort and strength for Éomer: a righteous, bold man with courage and passion and wisdom. Éomer had always tried to emulate his father, although he knew that the rage he had inherited from him sometimes did more harm than good.

How could he reconcile his memory with what he now heard? Had Éomund’s love for his wife been a lie?

Was Éomer doomed to repeat his father’s mistakes?

“Éomer…”

The pity on Erkenbrand’s weathered face was more than Éomer could bear. “Leave me now, marshal,” he ordered. “Go find the girl and keep her from my sight.”

Erkenbrand stood, his chair scraping against the stone floor. “As you wish, lord.” He bowed and retreated before Éomer changed his mind.

The door closed, and Éomer was left alone with his thoughts, his bloody hand, and his father’s seal.

---

Éowyn swept in an hour later, her long loose hair windblown from her ride. She had been at Aldburg to visit their great-uncle Cearl, who had been granted the ancestral seat in Éomer’s stead. The afternoon light was slowly fading, but the sight of her still jarred him from his reverie.

“Our uncle has kept your rooms just as they were,” she announced as she made her way to his desk. She stooped over it to kiss his brow. “He has taken others for himself, and promises to have your rooms always ready.”

“Good. Westú hal, sister. Welcome home.” Éomer tried to smile, but from Éowyn’s reaction, he guessed it came out as more of a grimace. Her eyes widened in alarm.

“Are you unwell?” She pressed the back of her cool hand to his forehead. “You have no fever. What is the matter, Éomer?”

Éomer pressed his lips together. “Catch,” he said, and tossed the seal on its leather cord across the desk.

Ever the fighter, Éowyn caught it easily. She turned it over in her hand. “This is not your seal, and yet—”

“It was our father’s,” Éomer blurted. He jumped to his feet and began pacing around his desk, hands clenching and unclenching with each step. “He lost this when you were a babe.”

“And now you have found it?” Éowyn asked. She sounded skeptical.

“It has been delivered to me in the hands of a Dunlending,” he said. He shook his head. “A Dunlending who claims to be our—” The word stuck in his throat, but he swallowed and forced it out. “Our sister.”

Éowyn’s thin eyebrows shot up and she nearly dropped the seal. “What!”

“She claims this was given to her by our father,” Éomer said, nodding at their father’s ring. “She says he put it on her with his own two hands.

“Well that’s ridiculous!” she exclaimed. “She must have found it and recognized the image.”

“Erkenbrand doesn’t think so. He believes her. He said… he was there, Éowyn. Erkenbrand was there when Fæder met the Wild Woman.”

Éowyn covered her mouth, appalled, but Éomer could not stop, not now.

“Fæder drew her from the river and bedded her,” he said, voice raw. “And then he gave that child his own seal.” He laughed, but there was no mirth in it. “And she’s only a year older than you, Éowyn. He did all this while married to our mother.” Éomer sat heavily against his desk and tangled his hands through his hair. “He betrayed all of us.”

Éowyn sank into the chair in front of him. She gripped his sleeve and leaned her forehead against his arm. She had no words, and, like Éomer, no tears. He yanked a hand free and rested it on the top of Éowyn’s head.

“Sister…”

“Mm?”

Even in that tiny noise, he could hear Éowyn’s prickly shield. He sighed. Sometimes, his sister’s strength put him to shame. She would never have done as he did. “Éowyn, what should I do?”

“What do you mean?” She straightened and looked up at him, her cool eyes guarded.

“I struck her,” Éomer said. His face burned. “I thought she was a thief, so I took the seal from her. When she tried to take it back—no, it was when she said Fæder had given it to her. I struck her. Hit her, whatever you want.” He pushed away from the desk, away from Éowyn, and strode across the room. “I am full of doubt. How can I accept this?” He waved a hand at the seal in his sister’s hand. “Accepting it means accepting that all we knew of our father was a lie.”

“Not a lie,” Éowyn said. Her mouth twisted. For a few minutes, she sat in silence, thinking. Éomer did not disturb her. Whatever she had to say would be worth the wait.

“It is possible to forget oneself,” she said at last. “I was blinded myself when I rode with you to Mundburg.”

“You were grieved,” Éomer protested. “You were consumed with it. That is not the same.”

“Isn’t it?” Éowyn extended a leg and rolled her ankle around to stretch her calf. “My feelings made me betray my duty. If my actions led to good and not ill, it was through chance alone.”

“And skill,” he said, unable to help himself. “And your love for our uncle, for our country.”

“Whatever happened with this woman, all those years ago, it was because our father was lost in his passion. You get that way sometimes. They say you were surrounded on the field after you saw—Well, you might have been killed.”

Éomer slapped the heavy stone wall with his open hand. “I might have been killed? What about you?” But he shook his head before Éowyn could respond. That was not what he was trying to say. “Éowyn. You said so yourself. I get like him, full of passion, or rage, or both.” He lifted his eyes to her. In the fading light, Éowyn’s expression was unreadable. “Am I doomed to make his mistakes?”

She snorted. “I doubt it. I can’t imagine you ever saving a Dunlending from drowning.”

“Éowyn.” He was serious now, and she sobered. “Éowyn, I’m afraid of his legacy. I clung to it, but now…”

“Don’t let it go,” she said. She came to him and clasped his hands around their father’s seal. “Not all of it. He was a good father to us, and a good leader of men. His mistakes…” She paused. “The more you know of him, the better you can protect yourself from his follies. And we all have our follies, Éomer. There is no shame in that.”

Éomer let out his breath. If Éowyn believed he could avoid what had happened to his father, there was hope for him yet. His heart lightened. “Even Faramir?”

“Of course,” Éowyn said. He could hear the relief in her voice. “And Lord Aragorn, and me, and you, and all of them. Now come. It’s too dark to see, and I would see you smile now. Besides, it’s dinnertime.” She pulled him to the door and swung it open. The light in the corridor was dim, but lighter than the study, and Éowyn hooked her arm through Éomer’s and drew him away.

“All that’s left,” Éomer said, “is to decide what to do with Gwir.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE STEPPING-STONES OF THE RIVER ISEN

When a young Dunlending woman appears at the Fords of Isen, Erkenbrand, Marshal of the West-mark, is caught in a decades-old secret that shakes Éomer King to his core.

part one (3530 words) of five | on AO3

A/N: This was rolling around in my head and wouldn’t leave me alone, so here it is. The Dunlendings have interested me for a long time now, and it’s been interesting to write about one! Thanks to @lothirielqueen for putting up with my endless musings. Hope you enjoy!

There was a woman standing on the river Isen.

Erkenbrand held up his hand to signal his guards to halt as they crested the riverbank. He was at the ford to inspect the new defenses he had ordered built in accordance with Éomer King’s wishes, but the soldiers guarding the southern end of the crossing were arguing about the woman on the river, their leather armor bright in the October sun. Only one man seemed to notice his arrival, and he quickly shouted over his comrades and pointed to Erkenbrand.

As soon as the soldiers realized who had come, the eldest among them jogged to where Erkenbrand waited atop the riverbank. The man, who Erkenbrand recognized as Sbern, the captain, kept one eye on the woman. Erkenbrand did the same.

The woman’s dark hair was wound about her head in braids that glinted in the sun, and she was dressed in fitted breeches, a long tunic, and a linen shirt with a satchel slung across her chest. Erkenbrand’s eyes narrowed, but he could not make out her features at this distance. She looked unarmed, but a dagger could be concealed almost anywhere. She did not look to be wearing any armor, either. She just stood there as though on solid ground, her boots barely an inch into the water. The soldiers’ arguments seemed to bore her, and she held a hand over her eyes as she squinted at Erkenbrand.

“Westú Erkenbrand hal!” Sbern said, panting.

“Westú Sbern hal,” Erkenbrand replied. “What is going on?”

Sbern gestured back to the river. “As you see, a Dunlending has come. She refuses to go back, and I do not trust that there would be no ambush if we chased her across.”

“She is standing on the river. Is she a witch?”

“No, there are stepping-stones from the west side. She can’t go any farther, though.”

Erkenbrand flinched. Of course. The stepping-stones. “Why have they not all been removed?”

“It is difficult work, my lord…” Sbern looked sheepish. “We have cleared the fords halfway, but as I said, I am not confident there will be no ambush. I do not wish to incite hostilities when they have so recently ceased. The woman is not entering our lands; she has not disturbed the peace. Just our comfort.”

Despite his annoyance at the woman’s continued presence, Erkenbrand nodded. He had chosen Sbern for his docile nature as well as his tactical brain. “I cannot fault you there,” Erkenbrand said. “Has she said anything?”

“Only that she is waiting for someone. She could not name him, but that he would come sooner or later. Excuse me,” Sbern amended, “she said she did not know his name. She said she would be happy to tell us his name if it would speed her errand.”

“All this in Westron?”

“Yes, but she knows a few words of our tongue as well. She laughed when I scolded Wadhel for aiming at her. She said she would not die today.”

Erkenbrand raised his eyebrows. “Cheeky,” he muttered. He urged his horse forward and walked to the river, Sbern trotting along down beside him. “I will speak to her myself, since nothing else can be done.” He pulled up just when his mount’s front hooves went in the water and again turned his eyes to the woman. She had taken her hand down from her face, and he could at last see her clearly.

He blanched.

“You!” he uttered, eyes wide.

The woman’s face, young and pretty and too pale for a pure Dunlending, split into a fierce grin. She pulled herself up; she was too tall for a Dunlending, too. She spoke to him in Westron.

“You know me?” she asked.

Erkenbrand nodded, shaken. The young woman was about twenty-five, with a short straight nose and a bright straight smile that he had seen countless times.

“Good,” she said. She jumped off of her stone and into the knee-high water in front of it, sending the soldiers around him into a panic. Some hefted spears; Erkenbrand heard more than one bowstring pulled taut. The young woman froze, hands held open over the water. She seemed totally unbothered by the weapons aimed at her, apart from a twitch in her jaw.

“What are you doing here?” Erkenbrand demanded. “You are not free to come here.”

“You know me,” she repeated. “I have a right.” She looked away from him to Sbern and the soldiers. “I have kin in the Mark,” she said, her voice loud and clear. “My father’s kin. I am of your country as much as of that one!” She pointed behind her and looked back at Erkenbrand. “I want to see the king. If you prevent my coming I will tell them all my father’s name. Take me to your king, or I will tell them.”

Erkenbrand’s mouth set in a thin line, but he did nothing. She stamped her foot.

“They will believe me! Your own face will make them believe me. Do you want that?”

He was beaten. Erkenbrand could not in good conscience let her speak on; this secret was not hers to spill on these shores. He had not even thought of it for fifteen years. Though his stomach clenched at the thought, his only choice was to take her to Éomer King.

“You,” he said, eyes narrowed and a finger jabbed in her direction, “will say nothing unless I command you to speak.” Her face soured, but she nodded. To his men, he said, “Lower your weapons.”

Muttering, the men did as ordered. Erkenbrand beckoned the woman forward, and she made her way through the water with her face scrunched up in distaste at the water puddled in her boots. Erkenbrand beckoned forward one of his guards.

“Check her for weapons,” he said in his own tongue. He was fairly confident that nothing would be found, but he wasn’t stupid. If this woman was sent as an assassin, she would die here and no later.

The woman submitted to the search, only wincing when Goduin patted across her breasts and below her hips. But she submitted, even presenting her satchel without being asked; Goduin shook his head when he had finished. He stepped back from the woman with an expression of sheer incredulity.

“She’s safe, my lord,” Goduin said.

“Good. She will ride with you.”

Goduin’s face pinched up almost comically, but he nodded and took the woman by the arm. He was not gentle about it, either. The young woman, struggling against her imposed silence, looked indignantly at Erkenbrand as if to ask if such force was necessary.

“You’ll ride with him,” Erkenbrand told her in Westron, “and you’ll be silent.”

Again, she submitted, but he could read the hatred in her eyes easily enough as Goduin marched her back to his horse. Erkenbrand ignored her black look; treating her with as much respect as she thought she deserved would only lead his men to grow suspicious.

Erkenbrand quickly went over the defenses of the ford with Sbern. He regretted the rush, but he did not fully trust his new charge to keep to her word. The sooner she was out of his hands, the better.

Within an hour, Erkenbrand, his guards, and the woman were on the road to Edoras.

Going straight to the capital was tempting, but Erkenbrand had duties to attend to at the Hornburg, not to mention his wife. A few extra days could hardly make much difference, he supposed, and so he ordered the party to turn south towards Helm’s Deep. As they rode into the valley, Erkenbrand called Goduin to ride by his side.

The woman was seated behind Goduin, with her arms wrapped tightly around his waist and her legs dangling. Erkenbrand eyed her thin legs and frowned; she would be sore just from the short ride from the Isen. Someone would have to attend to her if she was to ride out again tomorrow.

Erkenbrand set that thought aside and looked up at her face. Her round cheek was pressed against Goduin’s cloak as she stared at him with round dark eyes.

“What is your name?” Erkenbrand asked. She hesitated until he gestured at her impatiently.

“Gwir,” she said, and pressed her lips together at once.

“Gwir,” Erkenbrand said, “we are going to the Hornburg.” Her face darkened, and he thought of the dead Dunlendings buried in a mound under the dike. He went on. “You will be humble and silent. If you obey me, I will take you to Éomer King.”

Gwir nodded and turned her head away, though not before Erkenbrand caught the strained expression on her face. Did she want to go? She must, he thought. Why else would she risk her life?

By the time they rode across the stone bridge into the fortress, Gwir’s head was drooping. Goduin grumbled as he tried to keep her arms secure about his waist without bothering his steed. Fortunately, it was only a minute more to the stables. The stable-master ran out to greet Erkenbrand, who dismounted with a grunt. Boys working outside stopped to gape at Gwir until their master made a noise at them.

Goduin shook his shoulders to rouse Gwir, who nearly fell from her perch in shock. But she recovered well enough to stay on until Goduin could help her down. Her legs buckled as soon as she landed, and she clutched Goduin’s arm for support with both hands. Goduin scowled but did not push her away. Stablehands took over Erkenbrand’s horse as well as Goduin’s, and Erkenbrand led the way to the fort. Gwir stumbled along, still clutching Goduin’s arm, and stared around with wide eyes. Her hair was flyaway after the ride.

The door to the fort swung open as they approached, and Erkenbrand’s wife stepped forward into the afternoon light. He smiled; she had his welcome cup ready and waiting for him. But Elswide blanched.

Of course—Gwir.

Erkenbrand quickened his pace to meet Elswide at the door. He took a hasty gulp of ale. As soon as he swallowed, he forestalled the question he could read on her frozen lips. “Westú hal, lady. This is the daughter of a man of the Mark. She will not stay for long.” He pitched his voice so it carried to the few people watching from inside.

“Westú hal,” Elswide said. She took back the cup and shook her long graying braids over her shoulders as she looked Gwir over. Erkenbrand ushered his wife and the rest inside. Goduin stuck close to Erkenbrand with a dark look at the woman on his arm.

“Yes, yes…” Erkenbrand sighed. “Can you walk?” he asked Gwir.

She flushed and nodded, dropping Goduin’s arm at once. He lightened considerably and quickly backed away. Gwir glanced at him, half apologetic and half annoyed.

“Goduin, have Gamling come to my study,” Erkenbrand ordered. To Gwir, he said, “Come along.” He took Elswide’s hand, tucked it in his own, and led them through the hall to his study in the back wing. Gwir trailed after them, in as much awe as she had been outside.

No one spoke until Erkenbrand had barred the study door. Gwir twisted her hands together behind her back as she turned in the middle of the room, inspecting the woven tapestries on the walls.

Elswide dropped her husband’s hand and set his cup on his desk. “I did not expect guests,” she said in their own tongue. “This—” she gestured to Gwir— “is not a welcome sight.”

“I know,” Erkenbrand said. He ran a hand through his tangled hair and with the other unclasped his cloak. “I… am not happy about it, but there are choices that are not mine to make. She is indeed a daughter of the Mark, however little she looks it.” He and his wife both turned to Gwir, who was watching them with her dark eyebrows lowered.

“But who is her father? How can you be sure this is not a trick?” Elswide crossed her arms. “She might be a spy. She might be lying. She’s pale for a Dunlending, but there are other places she could come from. The north, for one.”

“Elswide, believe me. I have cause to know she speaks the truth.” He held up a hand to stem his wife’s protests. “I am as impatient as you to have her out of my hands, but for tonight at least she must stay. Put her in one of the small rooms. I will set a guard on the door. You may give her any chore that you trust her to do—though I would not give her anything she might use as a weapon.”

Gwir huffed and stamped her foot. Erkenbrand and Elswide turned to her; Gwir pulled a long leather cord from under her tunic and held it up so they could both see the blackened silver ring dangling on the end. A device was etched into the ring’s round face. Elswide stepped forward to look at it, and Erkenbrand realized too late what it was. His heart skipped a beat. He overtook his wife and tore the ring from Gwir’s hand. The cord was still around her neck, and she yelped. She clutched the cord to her neck.

“It’s mine!” Gwir growled. She glared at Erkenbrand and tugged hard on the cord, so hard that the thin edge of the ring bit into the skin of his fingers. “He put it on me with his own hands!”

“Erkenbrand…” His wife was staring at Gwir with shock. “Is that really his daughter?”

“Yes.” He gave up and dropped the ring, but he thrust his finger at Gwir with a deep scowl. “Do not take that out again, or I will take you back where you come from and throw you in the river!”

Gwir rubbed the ring’s face with her thumb before stuffing it back down her tunic. “I am not stupid,” she said. “If I wanted to die, I could have jumped in the river myself. You think I came here to hurt you? That’s about as stupid as it gets.”

Erkenbrand’s hands clenched, but Elswide pressed her hand to his arm and stepped forward. “What is your name?” she asked, surprisingly calm.

“Gwir verch Maderun a Gwellt Pennaeth. Gwir, daughter of Maderun and… Strawhead.”

Elswide pursed her lips at the derogatory patronym.

“You know your father is dead,” Erkenbrand stated. It was not a question. If Gwir hadn’t known, she would have asked to see her father, not the king.

She nodded. “News travels even now,” she said. “Back then we heard more of it. It only took a few days to hear that he had died. Although we didn’t know if it was true at first.”

“How did your mother come to meet your father, Gwir?” Elswide asked.

Gwir looked at Erkenbrand. He nodded at her to speak, and her mouth pursed as though she was sure he would not like what she was about to say.

“She was helping to lay stepping-stones across the river Isen,” Gwir said, “but she fell in and was swept across. My father got the water from her lungs and kept her in his camp. My mother is very beautiful,” she added, chin lifted proudly. “One of the great beauties of Dunland.”

“And how old are you? You look younger than—”

“Twenty-five.” Gwir shifted her weight and winced. She looked around, shrugged, and sank cross-legged to the floor, clearly sore from the day’s ride. She looked up at the two of them and blushed. It was a pretty sight. “I know he had a wife, and a son. But my mother is impossible to resist. She is still more beautiful than anyone else I have seen. Her husband was lucky to get her, even with me!”

That gave Erkenbrand pause. “Your mother is alive? And married?”

“Of course,” Gwir said. “Why wouldn’t she be?”

“Plenty of mothers in the Mark died at your people’s hands,” Elswide murmured. She ran her hand across her mouth, expression unreadable.

Gwir blinked up at Elswide and rested her round cheek on her hand. “Blame the wizard,” she said. “Blame the chiefs. You cannot blame me. I am sorry, but I will not take your blame. Somewhere outside these walls is a mound of dead Dunlendings, but I do not hold it against you. The war was bad, but it’s over now. I do not want to live it again. Once was enough.”

No one argued with that.

Erkenbrand turned to his wife. “You see why I had to bring her?” he asked in their tongue. Elswide nodded and squeezed his hand. “Thank you, my good wife. I trust you with this, but no one else.” He turned to Gwir and wrapped an arm around Elswide’s shoulders. “This is the lady of the Hornburg. You will obey her as you would me.” Gwir bobbed her chin at Elswide in a clumsy show of respect, still on the floor. She had never done so to him; he raised his eyebrows.

“You want my respect?” Gwir said. “It’s an earned thing. You have done what I wanted, but you have not been kind to me. The lady has tried, at least. That is worth something.”

He threw his hands up. “I cannot be seen to capitulate to strange Dunlending women who threaten me. You have not earned my goodwill, not by a long shot. I will attempt kindness if you will tell me why you have bothered coming to the Mark at all. I can see how little you care for your task. You are not eager.”

Gwir shrank at this. She looked very small, sitting there hunched on the stone floor. With her head down, he could see how much gray glinted in her hair.

“No,” she said. “I am not.” She sighed heavily. “The chief sent me to ask for help. He does not like me, and he hoped I could help him get something from the Mark. He is a small chief, but if he can… Well, a lot of chiefs died. Only a few remain. He said I could not stay if I didn’t come here, even though my mother argued it. But enough people would be happy to see me go that she couldn’t convince them all.”

For the first time, Erkenbrand felt a little pity for the girl; she clearly would have preferred to stay at home with her mother, who apparently was not impossible to resist.

“I don’t know what the chief thought he could get from you,” Gwir continued. “I don’t imagine anyone cares about my blood once they’ve seen the rest of me.” She pulled at the soft, dark hair at the nape of her neck. “My mother’s alright,” she muttered. “As long as she’s alright, I’m not worried about the rest. They’ll make do. They always have.”

“Why doesn’t your chief like you?” Elswide asked.

Gwir sat up, surprised. “The same reason as you,” she said, as though it was obvious. “I’m not enough like him. If he were less angry, he would see I am not trouble. My mother’s husband knows how useful and obedient I am. He has never complained of me in eighteen years. But he is one man in a hundred. Maybe even a thousand.”

Elswide’s fine eyebrows were nearly up to her hairline, and Erkenbrand was sure he looked much the same. It was hard to imagine this sullen creature as useful. Erkenbrand had to admit, however, that she was remarkably loyal. They had not asked about her mother’s husband, but the man had clearly won Gwir’s devotion as well as her affection.

If a gentle demeanor was what it took to get her assured obedience, so be it.

Erkenbrand reached out a hand to Gwir, who eyed him suspiciously. “Let me help you up,” he said. He tried to keep his voice gentle, though it was hard in the face of her dark, wary eyes. He had killed countless men with those eyes, and the men had tried to kill him.

But Gwir took his hand and laboriously climbed to her feet. He brought her to a chair by the desk and gestured for her to sit. She did so, and by the time Gamling arrived, she was quietly nibbling a slice of spiced brown bread with salted meat.

Erkenbrand’s lieutenant seemed much less bothered by Gwir than anyone else who had seen her; he must have been forewarned. Gamling bowed to his lord and lady as soon as the door was shut behind him.

“Welcome back, my lord,” he said in their tongue. “How goes it at the fords?”

“Well enough,” Erkenbrand said. He turned to his wife and said quietly, “Elswide, will you take her to one of the rooms?”

Elswide nodded. Excellent woman. “Gwir, you must be tired. Come with me and I shall get you settled. You can bring your supper with you.”

The two women left promptly; Erkenbrand sat heavily in the empty chair.

“Well, my lord?” Gamling said.

“Well, Gamling,” Erkenbrand said, “we have a guest at the Hornburg.”

#lotr fanfic#erkenbrand#dunlendings#rohan#lord of the rings#becca writes#the stepping-stones of the river isen#for the real shocker:#this story is actually complete#though it is part of a (short) series#hope you enjoy!!!

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE STEPPING-STONES OF THE RIVER ISEN

When a young Dunlending woman appears at the Fords of Isen, Erkenbrand, Marshal of the West-mark, is caught in a decades-old secret that shakes Éomer King to his core.

part two (3713 words) of five | part one | on AO3