#the roger corman tribute issue

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

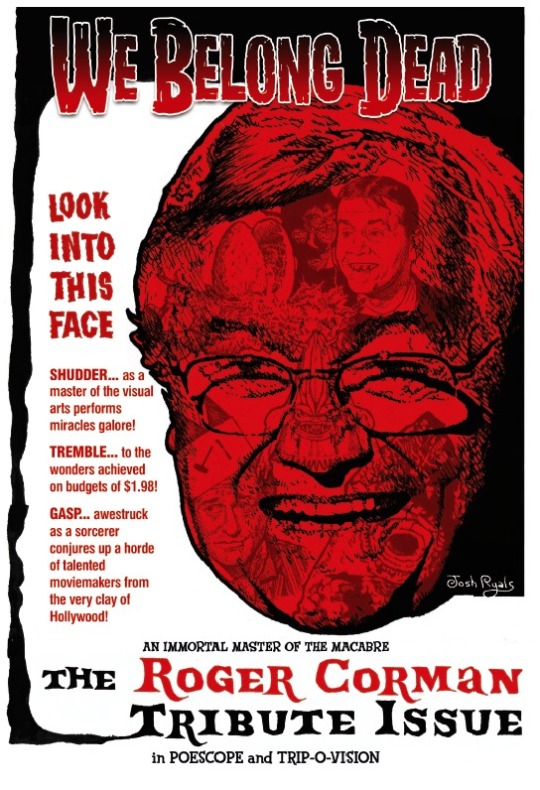

This week on Content Abnormal we present the X Minus One sci-fi story "Bad Medicine" AND reveal the cover of We Belong Dead's Roger Corman Tribute Issue featuring art by Content Abnormal's own Josh Ryals!

Order We Belong Dead's Roger Corman Tribute Issue HERE

#x minus one#horror host#bad medicine#norman rose#cliff carpenter#roger corman#we belong dead#darrell buxton#we belong dead magazine#tribute#fan art#josh ryals art#masque of the red death#the wasp woman#a bucket of blood#dick miller#jack nicholson#little shop of horrors#it conquered the world#not of this earth#attack of the giant leeches#pit and the pendulum#tales of terror#attack of the crab monsters#the roger corman tribute issue#house of usher#fall of the house of usher#clash at the castle#wwe clash at the castle#clash at the castle scotland

1 note

·

View note

Text

What a lot of people don’t seem to understand about Goncharov is that it isn’t just “another Scorsese gangster film” (which in itself is a pretty gross oversimplification), it was a crucial part of the pivotal point of his career as a director. It was Scorsese applying everything he learned about effective low-budget filmmaking from Roger Corman (who co-produced Goncharov as well, albeit uncredited) during the making of Boxcar Bertha, as well as applying John Cassavetes’ advice on making the genre films he wanted to make rather than the more documentary/autobiography works he’d done so far.

With Corman’s assistance (himself notorious for being able to stitch new films together out of scrapped footage from old ones), in 1973 he was able to finish and release two films: Mean Streets, and Goncharov, both films sharing actors, sets, even small bits of footage. Mean Streets happened to be the classic that would launch his career, and Goncharov would remain mostly forgotten until now.

Now, we all know of course that Goncharov got tangled up in international copyright issues from the get-go, with the 1983 and the 1996 recolors only further complicating things as the movie got passed around to different studios, and by that point there wasn’t much Scorsese could even do to get the film back and he was tangled up in a lot of other projects (although some theorize this as one of the reasons why Scorsese would later go on to notoriously champion film restoration and preservation, knowing firsthand what it’s like to have a passion project fall through the cracks and be taken away from you).

Still, the movie did have a limited release in the US and Canada (with a pretty strong fanbase in Winnipeg, actually, for the past decades most of the available copies of Goncharov came from VHS releases in Winnipeg, although very poorly preserved), and it wasn’t terribly well received at the time either. Even if these odd strokes of fate hadn’t destroyed Goncharov’s release I doubt the film would have fared that well much the same.

Where as Mean Streets reads like a blueprint for Scorcese’s gritty masculine hits like Taxi Driver and Goodfellas, Goncharov in many ways feels more in line with Scorsese’s more oddball projects like King of Comedy and Hugo, actually it really does have more in common with Hugo than his other crime films. I think part of why Goncharov’s become popular on Tumblr lately is because it’s remarkably, whimsical? It’s a weird way to describe a movie that gets so dark but, it feels way more grounded in fantasy than his other works (it even has that clock motif that Scorsese would later use in Hugo)

The name itself is a tribute to filmmaker Vasily Goncharov, a film pioneer from the Soviet Union. Goncharov was the first filmmaker to record a film using two cameras and use sound effects, he’d directed the first feature film made in Russian history as well as the first blockbuster with 1812. This was the period where Scorsese was hanging out with De Palma and it shows because there’s a lot of scenes in Goncharov that are explicitly in tribute to Goncharov’s works like Ivan the Terrible and Khas Bulat.

Some of you are wondering where do the queer elements in Goncharov come from or why is Katya unusually pro-active for a Scorsese female lead (or even why this film has a female lead at all when so many of his other works don’t really have one), that’s a side effect of this movie’s debt to Goncharov’s works, particularly Charodeyka (The Enchantress). Katya is basically Scorsese’s take on the Nastasya / Charodeyka character.

In the fifteenth century, Nikita, the vice-regent of Novgorod, and his son Yuri fall in love with Nastasya, the owner of a local inn. But Nastasya is actually the sorceress Charodeyka. The local deacon Mamirov tells Nikita’s wife about Nastasya, and the wife poisons her. She dies in Yuri’s arms, and the enraged Nikita kills Yuri - Jess Nevins, on Charodeyka (1909), description taken from The Encyclopedia of Pulp Heroes

Albeit described as “evil” and being depicted as a witch, Charodeyka bears no blame for any of the tragedy that happens in the movie, she just happens to be a beautiful woman targeted by dangerous affections of men and women alike (the movie does go some way towards showing it isn’t just jealousy that drives Nikita’s wife to murder Charodeyka) while bearing a secret of her own. I’m not saying Charodeyka was a queer tragedy by any means, but it is a tragedy of doomed love affairs and toxic family relationships and that seems to be what Goncharov’s playing with (Scorsese’s Goncharov cut out the implied incest and I’d say that was for the better).

This is kind of why Katya Goncharova kinda feels a little disconnected from Goncharov’s narrative up until the point they first meet and their fates intertwine tragically. Instead of a witch, she’s a femme fatale, and it damns her much the same just as Goncharov’s past catches up to him. It isn’t quite a remake but it’s taking a lot from Charodeyka and Ivan the Terrible and Vasily Goncharov’s other works, and Scorsese didn’t quite manage to blend these influences and tributes smoothly into the story, which is why the movie is kind of all over-the-place in a way that makes describing it make it seem like it’s an epistolary shitpost, which it very much isn’t.

It’s, among all the other things people have described it as, Scorsese’s oddball love letter to his influences as well as an important yet forgotten parts of film history (it’s not for nothing that Goncharov attempts suicide by train). Obviously, for many reasons, it was never going to catch on the way Mean Streets did, but it is fascinating nonetheless and I’m glad to see it’s been rediscovered.

76 notes

·

View notes