#the one in the city was stuck in the housewife role and had zero help and support

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So this is something I have always found interesting. While doing research on my PhD I read a greek paper about gender equality in Greece that said that basically, women's position in society was much, much more prominent during the byzantine empire (our "middle age" - not exactly but whatever) than it was during the first period of greek urbanization (early 20th century). Which is wild to me. But then the professor explained it by saying that during byzantine empire we had an agricultural economy so women had an active role in the means of production, they actively participated (in some instances even dominated) in the agricultural activities of their household, which were the main revenue for the family, aka, women worked and this work was, in fact, recognized as such. They had actual control and power over their household and over their (small) agricultural communities. I am not even talking about the privileged women that had actual political power. Also, raising children was pretty much NOT one woman's work. It wasn't a man's work of course, but women were not isolated in this. There were multiple women raising one woman's child, grandmothers, sisters, cousins, sisters-in-law, mothers-in-law, neighbours etc, while the woman was out, working in the fields, literally.

So. What happened with urbanization was that women were cut off their communities and got isolated in the big cities. They lost their support system, the tight social network of an agricultural community and most importantly, they lost their role in the means of production. They then became housewives, whereas before they were active participants in the agricultural economy. It is in that context that the gender inequality, in the sense of real societal imbalance between men and women, reached its peak, which later on led to the greek feminist movement as an echo of foreign feminist movements, and then the two wars completely changed the rules of the game and the rest is known.

I don't think this only applies to greek history btw, and we should always have in mind that actually no, women weren't mere broodmares in the middle ages and progress is not always linear. It has ups and downs.

all RIGHT:

Why You're Writing Medieval (and Medieval-Coded) Women Wrong: A RANT

(Or, For the Love of God, People, Stop Pretending Victorian Style Gender Roles Applied to All of History)

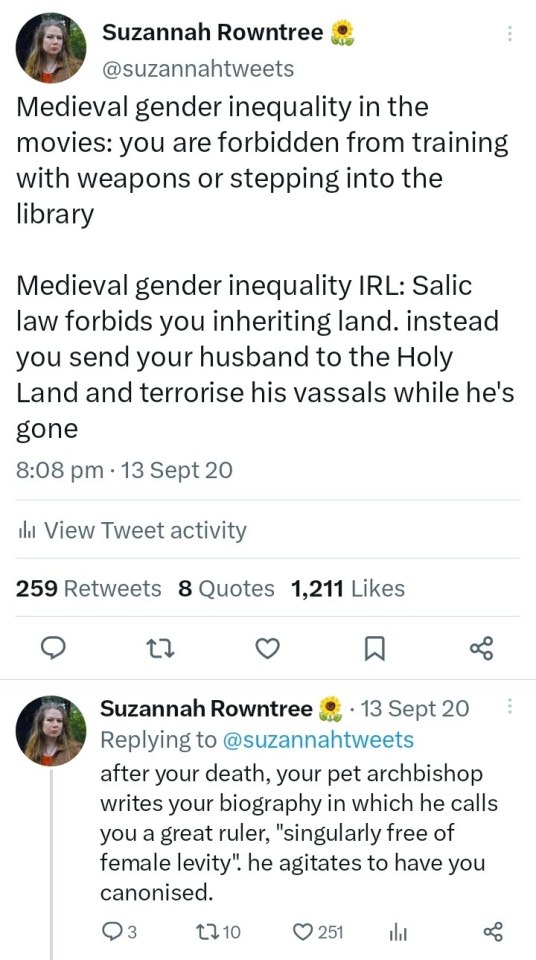

This is a problem I see alllll over the place - I'll be reading a medieval-coded book and the women will be told they aren't allowed to fight or learn or work, that they are only supposed to get married, keep house and have babies, &c &c.

If I point this out ppl will be like "yes but there was misogyny back then! women were treated terribly!" and OK. Stop right there.

By & large, what we as a culture think of as misogyny & patriarchy is the expression prevalent in Victorian times - not medieval. (And NO, this is not me blaming Victorians for their theme park version of "medieval history". This is me blaming 21st century people for being ignorant & refusing to do their homework).

Yes, there was misogyny in medieval times, but 1) in many ways it was actually markedly less severe than Victorian misogyny, tyvm - and 2) it was of a quite different type. (Disclaimer: I am speaking specifically of Frankish, Western European medieval women rather than those in other parts of the world. This applies to a lesser extent in Byzantium and I am still learning about women in the medieval Islamic world.)

So, here are the 2 vital things to remember about women when writing medieval or medieval-coded societies

FIRST. Where in Victorian times the primary axes of prejudice were gender and race - so that a male labourer had more rights than a female of the higher classes, and a middle class white man would be treated with more respect than an African or Indian dignitary - In medieval times, the primary axis of prejudice was, overwhelmingly, class. Thus, Frankish crusader knights arguably felt more solidarity with their Muslim opponents of knightly status, than they did their own peasants. Faith and age were also medieval axes of prejudice - children and young people were exploited ruthlessly, sent into war or marriage at 15 (boys) or 12 (girls). Gender was less important.

What this meant was that a medieval woman could expect - indeed demand - to be treated more or less the same way the men of her class were. Where no ancient legal obstacle existed, such as Salic law, a king's daughter could and did expect to rule, even after marriage.

Women of the knightly class could & did arm & fight - something that required a MASSIVE outlay of money, which was obviously at their discretion & disposal. See: Sichelgaita, Isabel de Conches, the unnamed women fighting in armour as knights during the Third Crusade, as recorded by Muslim chroniclers.

Tolkien's Eowyn is a great example of this medieval attitude to class trumping race: complaining that she's being told not to fight, she stresses her class: "I am of the house of Eorl & not a serving woman". She claims her rights, not as a woman, but as a member of the warrior class and the ruling family. Similarly in Renaissance Venice a doge protested the practice which saw 80% of noble women locked into convents for life: if these had been men they would have been "born to command & govern the world". Their class ought to have exempted them from discrimination on the basis of sex.

So, tip #1 for writing medieval women: remember that their class always outweighed their gender. They might be subordinate to the men within their own class, but not to those below.

SECOND. Whereas Victorians saw women's highest calling as marriage & children - the "angel in the house" ennobling & improving their men on a spiritual but rarely practical level - Medievals by contrast prized virginity/celibacy above marriage, seeing it as a way for women to transcend their sex. Often as nuns, saints, mystics; sometimes as warriors, queens, & ladies; always as businesswomen & merchants, women could & did forge their own paths in life

When Elizabeth I claimed to have "the heart & stomach of a king" & adopted the persona of the virgin queen, this was the norm she appealed to. Women could do things; they just had to prove they were Not Like Other Girls. By Elizabeth's time things were already changing: it was the Reformation that switched the ideal to marriage, & the Enlightenment that divorced femininity from reason, aggression & public life.

For more on this topic, read Katherine Hager's article "Endowed With Manly Courage: Medieval Perceptions of Women in Combat" on women who transcended gender to occupy a liminal space as warrior/virgin/saint.

So, tip #2: remember that for medieval women, wife and mother wasn't the ideal, virgin saint was the ideal. By proving yourself "not like other girls" you could gain significant autonomy & freedom.

Finally a bonus tip: if writing about medieval women, be sure to read writing on women's issues from the time so as to understand the terms in which these women spoke about & defended their ambitions. Start with Christine de Pisan.

I learned all this doing the reading for WATCHERS OF OUTREMER, my series of historical fantasy novels set in the medieval crusader states, which were dominated by strong medieval women! Book 5, THE HOUSE OF MOURNING (forthcoming 2023) will focus, to a greater extent than any other novel I've ever yet read or written, on the experience of women during the crusades - as warriors, captives, and political leaders. I can't wait to share it with you all!

#sorry for the long ramble it is kind of irrelevant to the OP but also somewhat relevant#patriarchy#also when I compare my two grandmas I see that the professor was right#my grandma in the village was much much more powerful than my grandma in the city#my grandma in the village basically controlled everything#the one in the city was stuck in the housewife role and had zero help and support

30K notes

·

View notes