#the more aligned with bourgeois interests they are the worse it is

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

things the US needs to address:

the collective psychosis that leads people to make posts like these

#in case it's unclear what i mean:#1.) blaming gen z men or any of the listed grifters is useless idpol#2.) half of your country did not 'vote against [your] collective best interests' lmao#if you truly believe that you have a fundamental misunderstanding of the position your country occupies in the global economy#and the benefits conferred onto its citizens for supporting the imperial world order#3.) i feel like OP kept this point purposefully vague (ofc social media has on effect on the common good. what effect specifically?)#but i'll still respond by saying#social media has helped immensely in exposing how often traditional news outlets lie retract revise and outright fabricate information#the more aligned with bourgeois interests they are the worse it is#the past year of western media's reporting on the genocide in palestine has done nothing if not highlight the incongruence#between what people see n share on the ground and what narratives corporate interests deem fit to disseminate through traditional channels#the importance of following independent (which does not equal 'unbiased') journalists has never been greater#4.) 'lazy minds and lack of empathy' empathy is not some bulwark against fascism. it can actually serve to further it quite easily#idk what OP is trying to get at here. lazy point = lazy response#5.) i can't say anything here that isn't summed up better by that tweet that's like#'american *sees something american happening americanly in america*: what are we a bunch of ASIANS?!?!???'#cause there's just nooo way politicians and public figures in the US could spew reactionary nonsense and get a huge following#unless the evil russians had a hand in it#cause it's not like the US is racism central or anything#come on now#(for those unaware i'm citing this tweet bc orientalism of this kind has historically been directed at russians/slavs in addition to#people from MENA and asian countries broadly)#6.) see point number 3 above; trying to police AI is a fruitless endeavor; people need media literacy in order to#understand the interests of the parties involved in the coverage of any event and better discern the truth about what's happening;#identifying the bias inherent to any news channel and then examining how that bias impacts its reporting does far more to help dispel#misinformation than just labeling anything you don't like or you think influences people the 'wrong' way as misinformation#anyway i'm done. clown.#sansgwilie

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Show and Tell, MLB style.

There's an interesting dichotomy in two MLB storylines that highlights, within the same show, these two approaches and the relative values of each. I am not here to litigate the value of the characters or the outcomes, only the presentation of specific elements within the show.

These characters are Chloé Bourgeois and Felix Fathom. The subject? Abuse

Okay, now that most have left...

Chloé brings us 'show' specifically season 2. The execution of Style Queen was exemplary. We had a pattern for Chloé by now, we knew her(we thought) and what made her tick. Then boom, Audrey drops. In two episodes it redefines everything. There's no moment anyone looks into the camera and says 'abuse' and yet in the animation, the voices, the storyboarding it is all laid out. From cringing, to wheedling, to the interactions between her father and her mother, to the fact that even at the end the very worst she could lay at her mother's feet was 'Why don't you love me?'

It's a victim portrait painted in vivid detail. It expands petty bullying into the larger cycle of abused becoming abuser and the cycle of violence. Whatever else you think on either side of this story it is in isolation, magnificent.

Contrast this then with Felix's presentation. From minor antagonist, to straight up villain(seemingly) to third party villainy, to misunderstood antihero perhaps?(time will tell) there is a lot to unpack with Felix, definitely. Yet the abuse segment of his story is: a line. One line. 'my father was a thousand times worse.' and that is all. We don't know how, or why, or what effects it has on Felix. Maybe will will in time but for now it is simply a check box. 'and also, abuse.' It provides us no insight, no context. Even a single line, with more thought, could put so much more into the moment.

'My mother protected me, and now I want to protect you.'

This instantly paints a more detailed picture. It helps align why Felix is so bold, and why Amilie is so timid in regards to him. It gives that super deep connection they have (despite his other antisocial tendencies) a little more context.

So that's my ramble. Something they did well, and something they did poorly.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 4.11.3 ‘Just indignation of a barber’

A wry little chapter about a conversation between some more onlookers, this time a step up in class from the impoverished old women we saw last time. An old soldier and his barber talk about Napoleon--or rather, His Majesty the Emperor, as they’re flagrant bonapartists.

That puts them towards the middle of the current political spectrum--which is ominous, as they’re relatively liberal bourgeois showing no sign of bestirring themselves to join the people’s side in the current conflict. They discuss a horse, and I have no idea what that does to our horse symbolism, as this one isn’t an overworked nag dragging a cart but Napoleon’s own horse, described in terms which I guess are attractive in warhorses.

It seems like the symbolism is doing something there. I’m really not sure what.

“Barber” is the translation FMA and Wilbour use; Hapgood calls him a hairdresser. But Rose wins this one, I suspect: the French is peruquier, which Rose and Google Translate render as “wigmaker.”

The man clearly is a barber also--he’s currently shaving the soldier--but “wigmaker” ties him much more clearly to the forces that wore down Fantine.

And that, of course, is his alignment in the story. He’s the one who was driving away the hungry mômes (now even more lost) the day Gavroche rescued them. Gavroche has had a disappointing day; his pistol is dogless, he couldn’t afford the supreme cake, and now, remembering the wigmaker, he throws a stone through the window. The wigmaker, who’s just been bragging about how happy he’d be to die with a cannonball in his belly, panics and thinks the small stone is a cannonball, a little bit of comedy about the gap in nerve between soldiers and civilians, which seems like an interesting meditation given what’s coming.

The text calls the wigmaker “worthy” and his indignation “just,” because we’re playing with entering the bourgeois point of view this chapter. From that vantage point, those things are perfectly true.

But Gavroche is operating from a different morality, one where driving the poor into the ground and then leaving them to die because it’s not your concern is maybe worse than a little light property damage.

This chapter is about the contrast between the two. And worrisomely, the bourgeois in the story aren’t getting it.

No doubt Hugo is hoping the bourgeois reader does.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

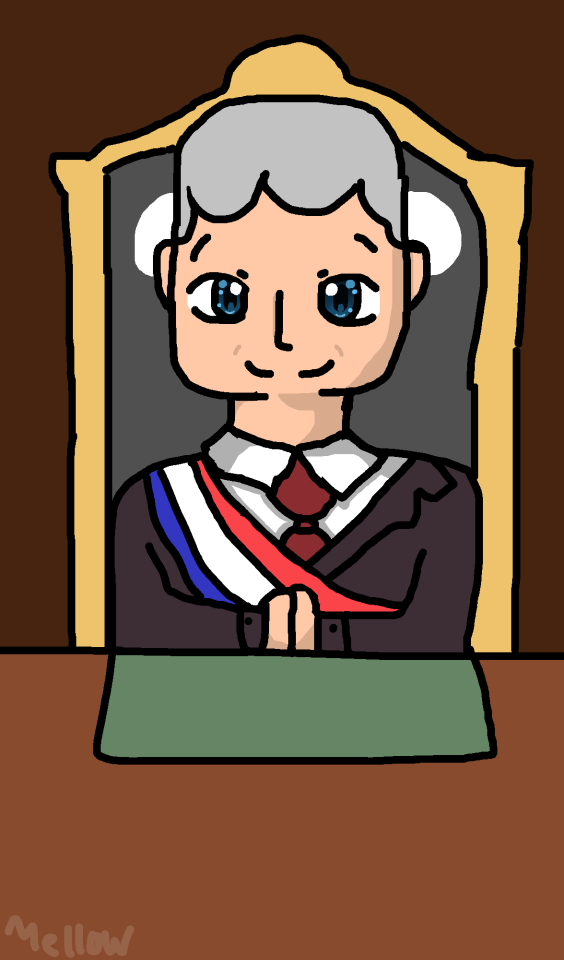

Character Bio 13

Andre Bourgeois aka Mayor

Age: 50

Gender: M

Race: French Species: Human Alignment: Neutral Status: Alive, (later on: injured) Relatives: unnamed mother, unnamed father, Chloe (daughter) Occupation: Director (formerly), Mayor, owner of Le grand paris hotel Love interest: Audrey (married)

Friends: Gabriel (formerly), Emilie, Adrien (currently) the man trying to find new friends

Enemies: Villains

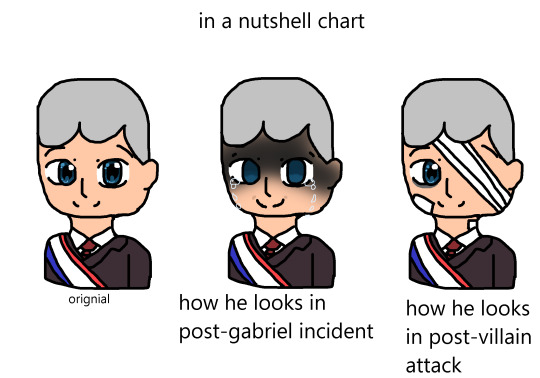

Personality: Manipulative, Cowardly, stubborn, Sensitive, Skeptical, can be nice in some terms.

Post-Gabriel incident personality: Emotional wreck (worse then redeemed chloe), still coward, sensitive, skeptical, nice, Empathetic

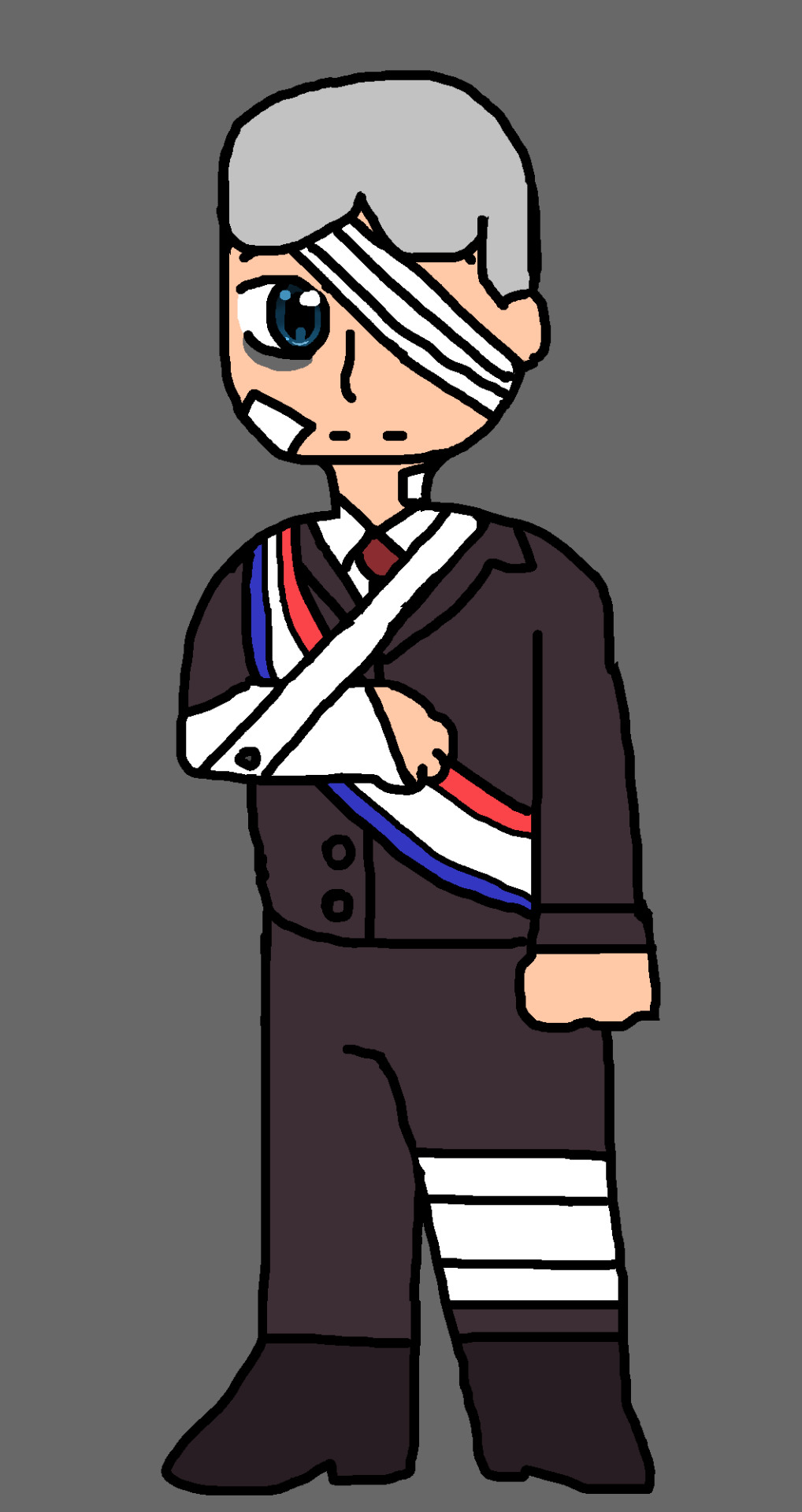

Post-unknown Villain attack (in unknown season): confident, less emotional, protective, venturesome, nice, alert Bio: Andre is the mayor of France. He keeps charge of the country, though he does a bad job of doing that... He’s usually abuse his power just for his family. He sometimes manipulate his citizens for his own gain. He also very stubborn on others opinions however, is scared of own family so he just listens to their opinion. He sometimes check on his family in a meantime.

Post-Gabriel incident bio: He cries much more lately. He can be easily get upset and angered. He pretty much stressed out Even though he’s the mayor, he wants to stay away from his country so he can deal with his problems. But he cant do that.

Post-unknown Villain attack bio: Before the attack, he finally calm down and apologize to everyone (he been wanted to do that after post Gabriel incident but he wasn’t in the correct mood. he gotten this feeling after seeing Gabriel), especially his daughter. He promised her he is going be better person.

After the attack: He’s is no longer scared, he’s much more confident. He willing to protect his own family and country, even if it risks his own life. He takes his job much seriously now, awhile still checking on his family. Because of this, he family sometimes just think he took his courageous little too far. Backstory:

When he was kid, he used to dance to music in class. From there, he hated dancing because he embarrassed from doing it. Believe it or not, Andre used to be middle class. He didn’t have much but he enjoyed awhile he could. He knew how to cook, clean and etc. In the meantime, he go skateboarding. When he was a preteen, He was skateboarding one day and found a little boy (by hitting him by accident.) The boy name was revealed to be Gabriel. He realized Gabriel never been out much before because of his parents. So he wanted to show him around and they became friends after that. Andre will usually get ladder and climb up to Gabriel so that they can go out together.

When they both became a teenager, they usually go to parties (Andre don't dance in them don't worry.) But one day, they went to a party. The party was a house party,. Andre and Gabriel went outside and chat there. Hours later, someone ended up shooting up the party. Everyone started to scream and started running. the shooter then goes to the backyard and noticed two boys. The shooter decided to point the gun at Gabriel. Gabriel was terrified. As soon as the shooter pull the trigger, Andre jumped in front of Gabriel and got shot on the side. Andre started screaming and crying in pain which caused the shooter run. Andre yell at Gabriel to go nearby telephone pole and call the hospital. But Gabriel was so scared that he ran off instead. Andre thought Gabriel wasn’t really his friend because he did that. He ended up passing out afterwards. He wake up in the hospital, found his mother angry. He attempted to tell her what happened but the mother yelled at him and took it as something else. He couldn’t reason with her. He developed becoming a coward because he feared to go to parties after that and talking back to his mother. After getting healed, he attempts to please his mother so she doesn’t get angry. This also how he ends up gaining the pleasing and manipulative tactic.

In his young adult years, He met Gabriel again but he wasn't so happy to met him. Gabriel saw him and wanted to apologize about the past. Andre accepts his apology but was little skeptical about it.

At some point in his young adult years, he became a director as he always wanted. He made 2 films, only one being successful (the one with Emilie.) Even though he liked filming, he lost motivation overtime. In his adult years, He decided he wanted to be mayor, his wife (Audrey) questioned if he’s sure about what’s he doing. He claims he does and moves on to be mayor. He claims he wants to protect the country.

As Malediktator

Altered personality: its the opposite of his personality. and all the bad traits are increased.

cause of akumanzation: He got upset because chloe and his wife wanted to leave him to go to new york.

Akumantized object: sash

Goal: he wants to control his own family awhile doing the same with the country.

Abilities: He can shoot circle like projectile at people and they’ll be under his control.

As Heart hunter

I have already made a post for this so I really don't have to type but I still can show these:

cause of akumanzation: Him and his wife ended up in argument leading to them to think they need a divorce. Akumantized object: brooches

As Wraith

Altered personality: overprotective, strict, aggressive, ignorant Force chloe to be with him...

cause of Haunzation: Chloe didn’t want to be bother by him or see him ever again, causing him to become upset.

Hauntzation object: Sash

Goal: He wants the entire Paris to be gone just for him and chloe to only exist.

He usually would target who chloe loves or friends with first.

Abilities:

He can extend his chain arm He can make extra chain arms He can create a portal

He can create a chained jail

When he floats, everything behind him turns black and pink.

Night vision

Not ability but awhile he hauntzatied, the entire France turns into nighttime.

Relationships (main ones)

Andre & Gabriel

Andre and Gabriel was childhood friends. They used to play together and hangout as kids. But because of that one incident, they wasn’t as close anymore.

They met again as young adults, and decided to hangout but not as much as before. They introduced each other wives and etc.

Andre pretty much considers Gabriel is only friend. He sometimes encourages his job though Gabriel never does the same. He’s usually happy to see him.

Spoilers

Post-Gabriel incident: After Hawkmoth/Gabriel was defeated, mayor found out he was hawkmoth. When he did, this completely broke him. He couldn’t look at Gabriel the same anymore. Not only he was upset, he is also mad at the fact he terrorize his country. But he was extremely mad at him for targeting him and his family.

After that, mayor believes that everyone he ever talk to, he corrupts which is why he wanted to start distancing himself from people. But he knew he can’t, so he ends up putting up a fake smile. Andre & Chloe

Andre loves his daughter dearly, too the point he spoils her. Every time his daughter is upset, he goes to fix it to make her happy again. However, he wish his daughter loved him back the same way.

Depise all this, he dislikes his daughter's way and fears her.

spoilers

Before and After post-villain attack:

Before the attack: After getting over his sadness, he decided to go apologize to Chloe about everything he’s done. He claims he going be better, which chloe liked.

After the attack: Andre loves his daughter so much to the point he would protect her. He doesn’t want anyone hurting her.

Andre & Audrey

Andre loves Audrey but he kinda of annoyed by her. He dislikes her attitude and rudeness. Even though he dislikes that side of her, he’s more scared of her then his daughter. He definitely doesn’t want to see her angry.

He dislikes how she treats their daughter.

Spoilers

After post-villain attack: Since he gained courage, he doesn’t tolerate her acting the way she does anymore. He yells at her when he sees her doing something he doesn’t like. He also told her to treat their daughter better.

Even though he could’ve divorce her, he still loves her somehow...

Full body:

Injured version:

Younger andre

Teen-Young adult andre

Other information:

In the days when Andre wasn’t a mayor, He used to dress fancy clothing because of his wife.

Andre hair used to grow very long. It stopped and started to fall out when he got older.

He will heal later on anyways here’s a chart ig

yes, I sat here and gave a literal mayor a backstory. am just that utterly ridiculous.

and you might be thinking, why didn’t I just make him divorce his wife? because I don't want to gave them man more suffering then he already have.

#andre bourgeois#chloe bourgeois#audrey bourgeois#malediktator#heart hunter#loveeater#miraculous ladybug#miraculous au#miraculous ladybug reboot#miraculous ladybug au#ml reboot

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking Like a Craftsman

Dedicated to the ideas of libertarian communism, libcom.org is a website that pursues the “political expression of the ever-present strands of co-operation and solidarity.” In March 2009 a contributor posting under the alias “Kambing” ventures the interesting thought that “the artisan” may qualify as “a rather attractive concept for a post-capitalist subject—it certainly beats the bourgeois star artist or proletarianized designer as a way of organizing creative activity.” However, “Kambing” continues, the concept of the artisan is at the same timedoomed as an attempt to overcome capitalism, as it can be so easily drawn back into capitalist processes of accumulation and dispossession. This is precisely the problem with a lot of autonomist (and anarchist) strategies for resistance or “exodus”—including some forms of anarcho-syndicalism.5This skepticism is only too familiar by now—any candidate put forward for the new revolutionary subject will be quickly rendered inappropriate, deficient, co-optable. The reasons for such pre-emptive skepticism, popular even among the most hard-line autonomists, anarchists, or anarcho-syndicalists, are manifold. However, a central argument for this co-optation is linked to the awe-inspiring malleability and adaptability of capitalism as such, accompanied by post-political renderings of “democracy,” helpful in reducing politics “to the negotiation of private interests,” as Slavoj Žižek puts it in his discussion of what he considers to be a symptomatic proximity between contemporary biopolitical capitalism and the post-operaist productivity of the multitude: “But what if, in a parallax shift, we perceive the capitalist network itself as the true excess over the flow of the productive multitude?”6The Fable of the Hedgehog and the Hare.The structure of the argument has been so thoroughly rehearsed in past decades that it has assumed a somewhat mythical truth. Capitalism is the shape-shifting creature-beast always already ahead and above—regardless of which revolutionary force tries to overthrow or subvert it—as it continually vampirizes any signs of resistance. It may be necessary to deploy the perceptual model of the parallax, as Žižek does, in order to maintain the structurally paranoiac—if absolutely legitimate—belief in capitalism’s shrewdness, which sometimes seems to resemble the clever hedgehog family in the Grimms’ fairytale “The Hare and the Hedgehog.” Its remarkable ability to re-invent itself and stay alive even as the current full-fledged crisis in interlinked systems of state and corporate capitalism turn capitalism-as-such into a transcendent miracle and/or metaphysical force with increasingly violent repercussions on the ground, with its most recent turn being the recruitment of state and legal powers. Referring to Carlo Vercellone’s 2006 book Capitalismo cognitivo, Žižek points to how profit becomes rent in postindustrial capitalism.7 The more capitalism behaves in “de-regulatory, ‘anti-statal,’ nomadic, deterritorializing” fashions, the more it “relies on increasingly authoritarian interventions of the state and its legal and other apparatuses.”8 While the “general intellect” in reality doesn’t appear to be that “general” or shared—with the products of the innumerable and increasingly dispersed multitudes becoming copyrighted, commoditized, and legally encapsulated as part of the accumulation of wealth by way of “rent”—the unity of the proletariat has split into three parts, following Žižek’s Hegelian idea of the future: white-collar “intellectual laborers,” blue-collar “old manual working class,” and the “outcasts (the unemployed, those living in slums and other interstices of public space).”9 Any possibility of solidarity amongst these factions appears to have been foreclosed, and in many respects the separation seems absolute. The liberal-multicultural self-image of the cognitive workforce doesn’t rhyme particularly well with the populist, nationalist position of the “old” working class, and both are further ostracized by the unruliness, illegality, and poverty of the outcasts who alienate white collar workers and blue collar workers alike, as they seem to indicate through their fate how imperiled their remaining privileges of citizenship may be.But Žižek’s Hegelian triad of postindustrial proletarian factions is debatable. The identities (intellectual laborers, working class, outcasts) are much too unstable, much too fluid and transient for a theorization of the (im)possibilities of overcoming capitalism. And it remains doubtful whether their insertion into the discourse provides more than a paralysis characterized by deadlock, tribal oppositions, and endless desolidarity.In fact, these and other identities shift according to (but also against) the self-transformation of capitalist institutions enabled by various neutralizations and recuperations. And these self-transformations entail wars of position, to use Gramsci’s term. As Chantal Mouffe put it a few years ago in pre-9/11, pessimism-of-the-intellect/optimism-of-the-will style: “although it might become worse, it might also become better.”10 Even Žižek—who has always endorsed a strong idea of capitalism, evincing a certain obsession with the task of proving capitalism’s fascinating, horrifying, and stupefying superiority as one that could only be seriously challenged by a return to the Leninist act—is himself looking for other actors and different processes now. Currently, his hope lies with the hopeless, the people fooled and victimized by “the whole drift of history”—in other words, the very “outcasts” from the proletarian triad mentioned above, those who are forced into improvisation, informality, clandestinity, as this is supposedly all they are left with in a “desperate situation.”11To rely on the desperation of others for one’s own idea of a successful insurrection is of course deeply romantic and utopian. Žižek may be right in asserting that waiting for the Revolution to be undertaken by others has been the fundamental error of too many leftists. However, would he count himself or anyone in his vicinity to be “desperate” enough to act, especially in a spirit of voluntarism and experimentation that would effectively dissolve the constraints of “freedom” as it is granted by neoliberalism?The “artisan” evoked by “Kambing,” though immediately disregarded as allegedly “doomed” to fail in the face of capitalism like so many others, may be an interesting figure to reconsider here—less out of interest in revolutionary politics than in envisioning alternate ways of organizing “creative activity” to replace and/or evade capitalist modes of production. As Raqs Media Collective have pointed out in their essay “Stubborn Structures and Insistent Seepage in a Networked World,” the figure of the artisan arrived historically before the worker and the artist, before “the drone and the genius,” while it enabled the “transfiguration of people into skills, of lives into working lives, into variable capital.”12 “The artisan,” Raqs claim, “is the vehicle that carried us all into the contemporary world.” However, after the artisan’s role in “making and trading things and knowledge” had been replaced by those of the worker and the artist, by the ubiquity of the commodity and the rarity of the art object, the artisan now seems to be returning, but in different guises—the migrant imbued with all kinds of tactical knowledges, the electronic pirate, or the neo-luddite, many of whom are immaterial laborers, pursuing processes of “imagining, understanding, and invoking a world, mimesis, projection and verisimilitude as well as the skillful deployment of a combination of reality and representation.”Interestingly (and similarly), “Kambing” distinguishes the “artisan” from the “bourgeois star artist” and the “proletarianized designer.” However, one may also imagine these distinct figures aligning—with each other and with others beyond themselves. These alignments or fusions would depend on an ability and a willingness to recognize and accept difference and diversity not only in one’s own social surroundings, but also within oneself as a subject. To acknowledge the fact that one may simultaneously inhabit more than one identity leads almost inevitably to co-operation with others that would go beyond the model of the homogeneous community.But, in Capital, Marx is highly skeptical of “co-operation” as a way out of capitalism: “Co-operation ever constitutes the fundamental form of the capitalist mode of production.” Its power isdeveloped gratuitously whenever the workmen are placed under given conditions and it is capital that places them under such conditions. Because this power costs capital nothing, and because, on the other hand, the labourer himself does not develop it before his labour belongs to capital, it appears as a power with which capital is endowed by Nature—a productive power that is immanent in capital.13A standardized bumper had been installed at the end of each car stall. It looked sleek, but the lower edge of each bumper was sharp metal, liable to scratch cars or calves. Some bumpers, though, had been turned back, on site, for safety. The irregularity of the turning showed that the job had been done manually, the steel smoothed and rounded wherever it might be unsafe to touch; the craftsman had thought for the architect.14The labor of modifying and repairing the work of others is certainly not groundbreaking in terms of anti-capitalist struggle per se. However, the physical skills, the attitude of care and circumspection, the inscription of a hand that performs “responsible” gestures, and so forth, all engender a shared authorship—in this case a cooperation between the absent architect’s and/or construction company’s work and the subsequent, careful labor of detecting and correcting the building’s design problems. This cooperation is neither contractually negotiated nor socially expected, but instead results from a specific situation in which a problem called for a solution. It is inseparable from local conditions and constraints, and should not be taken as a model for action. Yet, on other hand, it is intriguing, as it displays relationalities within material-social practices that usually remain unnoticed, and whose resourcefulness is thus overlooked.Paris scene with a goldsmith's shop , detail of a miniature from "La Vie de St Denis", 1317. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.In some respects Sennett’s concept of “thinking like craftsmen” resembles a definition of “design” that Bruno Latour introduced the same year The Craftsman was published. Speaking at a conference held by the Design History Society in Cornwall, Latour differentiated “design” from the concepts of building or constructing. The process of designing, according to Latour, is marked by a certain semantic modesty—it is always a retroactive, never foundational, action, always re-design, and hence “post-Promethean.” Furthermore, the concept of design emphasizes the dimension of (manual, technical) abilities, of “skills,” which suggests a more cautious and precautionary (not directly tied to making and producing) engagement with problems on an increasingly larger scale (as with climate change). Then, too, design as a practice that engenders meaning and calls for interpretation thus tends to transform objects into things—irreducible to their status as facts or matter, being instead inhabited by causes, issues, and, more generally, semiotic skills. And finally, following Latour, design is inconceivable without an ethical dimension, without the distinction between good design and bad design—which also always renders design negotiable and controvertible.15 Here, at this site of dispute and negotiation, especially on an occasion in which the activity of design is “the whole fabric of our earthly existence,” Latour finds “a completely new political territory” opening up.16

0 notes

Link

I wore black on election day. I did so amid a sea of feminists wearing white in honor of racist suffragette leader Susan B. Anthony for her role in the struggle for white women to secure the right to vote. I saw black as the only choice on November 8th, which for me and many other citizens was not a day of celebration, but a day of mourning as the United States faced the false choice between two candidates who ranked among the least favorable in our nation’s history. Both options were corrupt, racist, and burdened by the extra baggage of their respective past and present – some of which had literally overlapped for more than a decade. I saw little to celebrate, despite the historical significance of a woman having made it so far in U.S. leadership, and instead lamented the pitiful state of our supposed democracy where only women like Hillary Clinton possessed the means to ever make it this close to the presidency.

To make matters worse, calls to wear white on election day in honor of two women who had worked against the interests of marginalized groups at so many turns marked a complete disregard of our humanity. A timeline full of enthusiastic chatter about pantsuits, wearing white, and posting “I Voted” stickers on Susan B. Anthony’s headstone induced the same feelings for me as pronouncements from Trump supporters eager to “make America great again.” Their celebration was not meant for women like me. On the contrary, the praise they heaped upon Clinton was in direct opposition to the chorus of people, many of them also women, who had presented extensive, fact-based arguments against Clinton’s bourgeois, corporate-aligned, imperial feminism and empty messaging. And it was ultimately their cognitively dissonant defense of the candidate so many had justifiably labeled as an adversary that came at our expense.

(Continue Reading)

#politcs#social justice#intersectionality#race#femisism#class#classism#election#democrats#democratic party#hillary clinton#susan b anthony

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Looking Back at the Strange and Surly History of Bay Area Funk Art

View of the Funk show (1967) in the Powerhouse Gallery at U.C. Berkeley (image courtesy BAMPFA)

SAN FRANCISCO — It was sometime after 8:15 pm on April 28, 1967, in the Physical Sciences Lecture Hall at the University of California, Berkeley. In progress was a symposium about Funk, the latest art show exhibited in the school’s University Art Museum. The symposium seemed to promise a lively discussion among several of the artists with work in the show, while moderator duties were covered by Peter Selz, Funk’s curator and the executive director of the museum. Instead, the symposium delivered total chaos.

The conversation went off course as the panelists let slip their grievances with the way Selz had approached the show. Figurative painter Joan Brown felt that Funk failed to present funkiness in context. Avant-garde ceramist Peter Voulkos decried that funk was strictly delimited to a Bay Area oddity. Experimental assemblage-maker, filmmaker, and altogether creative outlaw Bruce Conner denied the premise of Funk altogether. For Conner, the art was too diverse to fit under an umbrella so small and outdated. Conner was probably the most vocal of the artists who believed that whatever art qualified as funky was out of style years before the opening of Funk. Painter and ceramist Jim Melchert went on record with, “[Good funk] attempts to resolve those two essences of mankind: one a striving toward perfectibility, the other a kind of gross realization that we’re all just animals.” Melchert drilled down further into this by wryly lamenting all the funky artists that Selz had left out— like William Shakespeare and Albrecht Dürer.

Funk Symposium, April 28, 1967; University of California, Berkeley (photo by Ron Chamberlain)

Things fell apart when the artists voiced their dissent more creatively. A shoe flew across the stage. Someone began an impromptu jam session. One of the artists poured a glass of water over their own head. Despite the histrionics, the panelists had a great point. The premise of Funk was flawed. “Notes on Funk,” the essay Selz authored for the show’s catalogue, offers clues regarding where this creative fissure might have occurred.

Funk April 28–May 29, 1967; Powerhouse Gallery, University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley (photo by Ron Chamberlain)

“Funk art,” Selz wrote, “so prevalent in the San Francisco-Bay Area, is largely a matter of attitude.” I agree with Selz that this notion is a fundamental component of funk. There are no goals or agendas, only a je ne sais quoi accepted on a pass/fail basis. Conversely, as of this writing, the Wikipedia page for Funk Art offers a digest of how the subject is all too often conveyed: as a movement with certain practitioners. Both of these terms imply a shared goal or motive. However, there was neither a credo nor manifesto behind funk that would inspire the pursuit of perfection. If anything, funk artists avoided being labeled funky. The only definition for funk with staying power seems to be, as phrased by Selz in “Notes,” “When asked to define Funk, artists generally answer: ‘When you see it, you know it.’”

Despite the diffuse nature of funk, Selz takes a page of his essay to explore the pedigree for the show’s eponymous attitude. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades as well as the works of Jean Arp, Joan Miró (especially “Object” from 1936), and Méret Oppenheim are each singled out as possible prototypes, or distinct examples of funk. Selz continues by citing recurrent themes in funky art, especially: private metaphor, self-deprecation, “erotic and scatological” motifs, ambiguous intent, and moral ambiguity. Selz emphasizes this last point by opening the catalogue with a quote from The Bald Soprano (1950) by the absurdist playwright Eugène Ionesco:

Mrs. Martin: What’s the moral?

Fire Chief: That’s for you to find out.

Selz wanted to respect the spirit of the artwork by steering the show away from making “a definitive statement” about funk. Nicole Rudick quotes Selz in her essay in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition What Nerve! (2014) at the Rhode Island School of Design: “I was merely interested in pointing out something that was going on right now with a few examples … from the background that have to do with the developments as I see it [sic].” The point of Funk was to offer viewers the chance to judge the art at face value. Selz amassed nearly sixty objects (we now recognize funk as extending into any medium, but Selz focused his exhibition on sculptural objects) for the exhibition and implicitly gave each equal billing under the singular title of Funk. Some pieces were small, while others were gargantuan installations. Some were created by Beat writers in the mid-1950s while others were created by hippies in the mid-‘60s. Some of the objects were pale while others were as brightly decorated as a venomous creature. Some were figurative, some surreal, and some vaguely squishy. The diversity of works ensured that a single definition of funk was impossible. If everything in Funk was funky, then sure, why not throw in the works of Shakespeare and Dürer?

Peter Saul “Relax in the Electric Chair (Dirty Guy)” (1966) exhibited at the Funk show (image courtesy Israel Valencia and the di Rosa Preserve)

No one, Selz included, presumed that the show would make an impact beyond its run through May 1967. Selz said years later, “We never expected that [Funk] would become a part of art history.” After the show, knowledge of the aesthetics associated with it quickly spread across the country. Reviews of the exhibition appeared in Artforum, Time magazine, Chicago Daily News, New York Times, and outlets abroad. While some of these were unflattering (Artforum was scathing, which Selz pinned on the magazine’s permanent relocation from Los Angeles to snobby New York City), the march of funk from sea to shining sea continued.

The term “funk artist,” first entered the American lexicon as shorthand for anyone with work in Selz’s 1967 show. The most famous example is John Perreault’s 1967 article titled “Metaphysical Funk Monk,” about a William T. Wiley show in New York. Notoriety followed the designation as Funk artists later showed with increasingly prestigious institutions and gained representation in the Big Apple. Joan Brown, for example, was in the Whitney’s Young America 1960 exhibition prior to Funk, while ceramist and painter Robert Arneson and ceramist David Gilhooly showed there just a few years later. Over the years, the definition of funk expanded, until today, when any artist whose art is difficult to categorize is at risk for being labeled funky, or worse, inspired by the funk “movement.”

Mowry Baden, “Delivery Suite” (1965) 1.24 m x 1.95 m x 1.90 m (high) steel, fibered polyester resin, collection of Theresa Britschgi Seattle WA (© 2017 Mowry Baden)

To be clear, none of this historical account is meant to suggest that funk is bunk. A very real phenomenon of art that could be considered funky cropped up around the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid- to late-1950s. This art was made during a short period of time between the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, roughly aligning with the rise and collapse of Beat culture in the Bay Area. Artists went to New York to sell out, but they made the pilgrimage to San Francisco to create. Between World War II and the early 1960s, two or maybe three real galleries made up the corpus of the Bay Area art market. Despite this paucity of places to show their work, and a very small chance to earn a living off art alone, artists poured into the area seeking camaraderie and the freedom to pursue their vision. Artists felt the financial squeeze of trying to make a living in a small city without art buyers and a dearth of available day jobs. So, many sought refuge in the ivory tower. Teaching not only provided a steady income, a sense of community, and encouraged the free flow of ideas, but also offered artists the opportunity to use school facilities for their own projects after work. Most funky artists crossed paths while teaching or studying at the San Francisco Art Institute or the University of California, Davis.

Teaching was supplemented by the artists’ fascination with life outside the classroom — the streets, coffee houses, and houseboats or abandoned garages hosting single-serving exhibition spaces. In Selz’s words, funk looked “at things which traditionally were not meant to be looked at.” Without patrons or buyers to impress or woo, artists were open to risks. They experimented with challenging materials and unconventional ideas. They made art that was ugly rather than beautiful, rough rather than refined, and funny rather than respectful. The art was intimate, meant for very few eyes or no eyes at all. This is the essence of true, honest-to-god funk art.

Harold Paris, “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme” (1966) plastic and rubber, 4 x 5-1/2 in., (courtesy of University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, gift of the artist)

It is disheartening to see this fiftieth anniversary of Funk pass by without so much as a nod from the art world. No heavy tome about funk is set to roll off the presses, no symposium gather to discuss funky tropes, and nary one prominent museum open an exhibition to celebrate funk and explore the directions of its scholarship. Still, some modern and contemporary art museums have examples of funk or funk-adjacent art, and some of the best are in Northern California. If you are in the area, check out the excellent Recent Gifts exhibition at the brand new Manetti Shrem Museum in Davis (which is free) and book a viewing for the di Rosa Collection outside Napa Valley (not free, but still very good). Further examples are on view at the Cantor at Stanford University and hither and yon in San Francisco MOMA.

The lessons of funk are available to contemplate if we find the art and, as Selz suggested, make up our own minds.

The post Looking Back at the Strange and Surly History of Bay Area Funk Art appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2pwtCd3 via IFTTT

0 notes