#the little shepherdess 1892

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Paul Peel (Canadian, 1860-1892) The Little Shepherdess, 1892 Art Gallery of Ontario

#paul peel#canadian art#canadian artist#classical art#art#fine art#oil painting#fine arts#the little shepherdess 1892#the little shepherdess#classic art

780 notes

·

View notes

Text

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Little Shepherdess (Paul Peel, 1892)

644 notes

·

View notes

Text

See https://www.facebook.com/groups/peintureacademique/permalink/7287770821343026/ :

"The Little Shepherdess (1892) "Oil on canvas, 160.6 x 114.0 cm" [Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada] -- Paul Peel (Canadian; 1860 - 1892)

Paul Peel (1860-1892) was the son of a marble-cutter and drawing teacher (John Robert Peel). He studied at the Pennsylvania Academy, Philidelphia (1877-1880 under Thomas Eakins); the R.A. Schools, London (1880); and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris (1881) under Gerome and others.

He returned to London, Ontario, and Toronto for a short time about 1890, but was chiefly active in Paris. He travelled widely in Canada and in Europe, exhibiting as a member of the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy. He later returned to Paris where he died in October 1892. Before his death he had achieved a considerable success for his technique in such academic subjects as 'After the Bath' (1890).

He was one of the first Canadian painters to portray nude figures, as in his A Venetian Bather (1889). At the time of his death Peel appeared to be changing his style toward Impressionism. However, he did not live to develop his art beyond its academic sentimentalism.

Source: The Art History Archive -The Paintings of Paul Peel

"

#painting#forest#fairyish#x#study#shepherdess#barefoot#reflection#river#stream#creek#natural nature#dipping#grass#trees#explained explanation

1 note

·

View note

Text

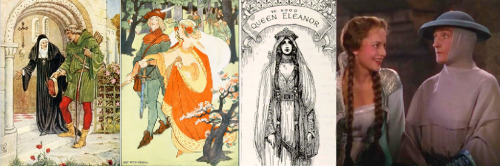

Okay, let’s talk about Maid Marian. Let’s really talk about Marian. So often I see her character disparaged as a damsel in distress without agency of her own, but that is honestly so far from the truth. In fact, Maid Marian is considered to be one of the earliest examples of the “strong, independent woman” character archetype. Not only is it untrue to call her a damsel in distress, it’s also unfair.

As with many stories, Robin Hood is a story filled with men. I love it, but there’s no denying it’s a story filled with men. As the only prominent female character in a story that has been retold for close to 1000 years, centuries of ideas about femininity have been funneled into this singular character. Among the array of male characters, we see many ways to be masculine: smart, witty, artistic, strong, brave, charitable, loyal, both fighters and lovers. All of the characters have been adapted through the years, but Marian can still be distinguished as the only canonically present female character in the main cast.

Other women we traditionally see include Alan’s bride, the Prioress of Kirklees Abbey who murders Robin, Marian’s serving woman, and a few queens. Various contemporary novels, films, and TV representations have added women to the cast to even it out, but Marian is still the only primary female cast member. As such, centuries of what it can mean to be a woman have been reflected through her.

Let’s take a look at what exactly that has looked like through the years.

One of the things I love best about Robin Hood as a legend is that it is constantly evolving and changing for the needs of the audience. Across centuries and decades it has been changed to suit the ideas of the day. Even the oldest extant documentation of Robin Hood is not considered the “original version” because there is no way of really knowing when or how these stories started, or how long it took for them to be written down.

So, just as there isn’t a standardized Robin Hood, there isn’t a standardized Maid Marian. We know that she was added later in the Robin Hood tradition, during the 15th century as part of May Day celebrations, and quickly became a common character in future iterations of the Robin Hood story. Her origins are still murky at best, and it’s impossible to pinpoint the very first time she was introduced.

Her many origins include a shepherdess named Clorinda from Child Ballad 149, an unrelated Marian character in 15th century May Day games who happens to also have a lover named Robin, and a historically based woman named Matilda Fitzwalter appears in Anthony Munday’s “Huntingdon” plays from the 15th century. Furthest from our understanding of Marian is a play titled Robin Hood and the Friar, very merry and full of pastime, proper to be played in May Games. In this play we find Marian as a “trull” a.k.a. prostitute, employed by Friar Tuck. A far cry from how we know both Marian and Friar Tuck today. So far, she’s a working woman, a noblewoman, a romantic interest, and a prostitute.

The best known and most enduring of these early variations is Child Ballad 150 (you can read it in full here). In this ballad, we see Marian dress as a boy, and go into the forest fully armed, to seek out her lover, Robin Hood. When she finds him and does not recognize him, they begin to fight and Marian handily beats him in their sword fight. Robin immediately asks her to join the Merry Men, they recognize each other, and return to camp for feasting and a “happily ever after” full of adventures.

youtube

- Child Ballad 150

“With quiver and bow, sword, buckler and all,

Thus armed was Marian most bold.”

This ballad is reminiscent of introductory stories of the Merry Men -- Robin meets a stranger, they fight, the stranger wins, and Robin offers them a place in his band.

We can clearly see in Child Ballad 150 that Marian was considered Robin’s equal and a regular member of the group from early on her individual tradition. Other parts of her early tradition survive as well -- she’s a romantic partner for Robin, and a noblewoman.

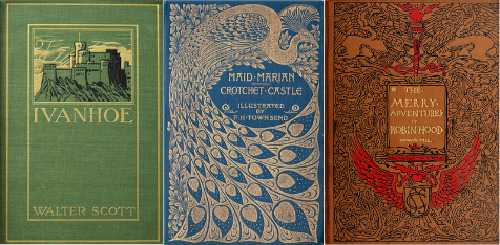

As we progress forward in Robin Hood traditions, we continue to see the story change. Notable changes occur during the Victorian period, when general interest in Robin Hood stories was revived thanks to the publication of Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) and Howard Pyle’s The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883). Marian does not appear in Ivanhoe and is mentioned only once in Pyle’s book, and is effectively written out of the story entirely.

Despite this, we see other novels and stories released as Robin Hood grows in popularity, and here is where we begin to see the idea of a damsel in distress begin to gain traction. As is true in every retelling of Robin Hood, the story changed to suit its audience and to suit the ideas of contemporary society and intended audience.

Victorian literature is full of interesting and lesser known works of Robin Hood, as a result of a Victorian obsession with medievalism and with Robin Hood. Maid Marian and Robin Hood: A Romance of Old Sherwood (1892) by J.E. Muddock features a very distressed Marian who does need rescued and has very little agency. Other Victorian works take a similar tone and cast Marian as a damsel, but this is not the narrative that ultimately survives this period of Robin Hood resurgence.

Thomas Love Peacock published a novella simply titled Maid Marian (1822). Interesting to note, because Robin only appears briefly as a supporting character in Ivanhoe, this is actually the first true Robin Hood novel as a story by itself. Here we see an active, and independent Marian, evocative of Child Ballad 150.

‘Well, father,’ added Matilda, ‘I must go into the woods.’

‘Must you?’ said the Baron, ‘I say you must not.’

‘But I am going,’ said Matilda.

‘But I will have up the drawbridge,’ said the baron.

‘But I will swim the moat,’ said Matilda.

‘But I will secure the gates,’ said the baron.

‘But I will leap from the battlement,’ said Matilda.

‘But I will lock you in an upper chamber,’ said the baron.

‘But I will shred the tapestry,’ said Matilda, ‘and let myself down.’

- Thomas Love Peacock, Maid Marian (1822)

Matilda does indeed go to the woods, takes on the name Maid Marian, and rules the forest with Robin Hood. Other Victorian works take a similar approach to Marian and show her as involved and capable including Maid Marian, or the Forest Queen (1849) by Joaquim Stocqueler, which follows a more traditional Robin Hood storyline filled with adventures and danger.

Later classic works include an active Marian as a member of the outlaw band, as well. Roger Lancelyn Green (1956), Charles E. Vivian (1927), and Paul Creswick (1917) all write a Marian who speaks for herself and works with the outlaws, often dressed as a man.

Hollywood enters the scene of Robin Hood retellings as early as 1908, but the oldest surviving Robin Hood film is Douglas Fairbanks’ Robin Hood (1922). This silent movie, groundbreaking in budget and sets, features Marian (played by Enid Bennet) as a strong character who holds her own throughout the film. After this, we see another groundbreaking film, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland. This film is widely thought to be the gold standard of Robin Hood films, and I am definitely in that camp. Marian has more agency in this movie, and the lovely Olivia plays a rather coy noblewoman. While we don’t see her taking up a sword in this film, we see her developing the plan that ultimately rescues Robin from the hangman’s noose, successfully warning Robin and his men of Prince John’s plans, and standing her ground while on trial and defending her ideals. Yes, she is rescued from prison in the climax of the movie, but she also plays a vital role in rescuing Robin earlier in the story.

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) begins with a woman of action, but at the end sees Marian rather helplessly forced into a marriage and moments away from being sexually assaulted when Robin literally catapults himself through the window to save her. 20 years later in Robin Hood (2010) Cate Blanchett’s Marian is fully capable in combat and is shown to be a responsible and dedicated lady of Loxley, working the fields and caring for her home.

Meanwhile in a contemporary TV adaptation, Marian is depicted as a Robin Hood figure herself, known as the Nightwatchman. (2006, BBC’s Robin Hood) Although the writers later did a disservice by (unpopularly) killing her character as a season finale, Marian was still depicted as competent and in charge of her own choices and actions, and in fact rescues herself from an unwanted marriage.

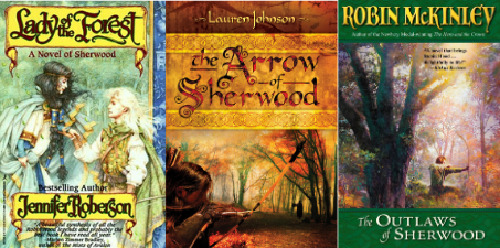

Contemporary Robin Hood literature also features an active Marian. Jennifer Roberson’s Lady of the Forest (1995) and Lady of Sherwood (1999) present Marian as a noblewoman who, over the course of the text, takes control of her own story in her capacity as a member of gentry, Lauren Johnson’s The Arrow of Sherwood (2013) sees an incredibly historically inclined retelling of the Robin Hood story, and includes a dedicated and politically savvy Marian. She doesn’t run into the forest, but makes a real difference through her smart decisions and political manipulation. Robin McKinely’s The Outlaws of Sherwood features Marian as an excellent archer, better than Robin, and she easily slips in and out of the outlaw camp as needed, is skilled in woodscraft, and is a valued and substantial member of the outlaw group. Honestly, I think it would be difficult to find a literary retelling that doesn’t include an active Marian character.

So where do our ideas of Marian as a damsel in distress ultimately come from? I have a few theories.

First, we see the archetype of damsels in distress throughout other fairy tales and folklore, so it’s tempting to assume that Marian is the same and portray her as such, and there are examples of her character playing that role either in whole, or for part of the narrative.

There are unfair assumptions made about medieval women in general, that ignore the powerful positions women could hold, and the amazing things that women did during this period. When people picture medieval women, they are often embroidering tapestries, being forced into unwanted marriages, being beaten by their husbands, and dying in childbirth. There is truth in stereotypes, but there’s also room for deeper understanding of the historical context, and a wider story to be told that includes women standing up for themselves and exercising their own strength and skills. (It’s not good feminism to overwrite real women’s history.)

We see this stereotype most often in movies and TV adaptations, which are highly visible and memorable, cementing ideas about the Robin Hood legend (and Marian) in the general psyche.

Children’s picture books, perhaps one of the first introductions a person might have to Robin Hood, tend to play out the story like a traditional fairy tale and Marian is again likely found in an upper tower, calling for help.

Some find it demeaning for Marian to ever require saving, or to be saved by anyone other than herself. I feel differently about this. People rely on other people, and it’s not inherently weak to ask for support from someone, especially from a romantic partner. The story of Robin Hood is good fun, but it’s also full of danger and peril. It’s not surprising that various characters need to be rescued by friends and lovers throughout various tales. Robin Hood, Little John, Will Stutely, Sir Richard of the Lea, Alan A Dale’s bride, and yes, Maid Marian. All of these characters have stories where they require smart and daring rescues, and they’re exciting stories! Because Alan’s bride and Marian are women, this does not exempt them from the support of their male friends. They deserve to have someone watching their back. I am not offended by Marian needing help; it’s not only human, it’s a staple for a multitude of characters in Robin Hood lore.

As with much of media, Marian is the single female in what’s otherwise mostly a boys’ club. She has been the single point of reference in this story for women for centuries. I find that incredible. She was my favorite character as a child because she was the only woman, the only person I could potentially see myself in. With a global story such as Robin Hood, that’s not an insignificant role. No matter what her part may be in any given retelling, there are pieces of women from centuries long past and not so distant. I find that fascinating, worth respecting, and that’s why she’s my favorite character to this day.

tldr: Drink your respect Maid Marian juice.

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Paul Peel The Little Shepherdess 1892

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Little Shepherdess by Paul Peel, 1892 (detail)

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Peel (London, 1860-1892)

The Little Shepherdess (1892).

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Little Shepherdess ~ 1892 ~ Paul Peel (Canadian painter, 1860-1892); the last or bottom version can be found on notecards

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Livia Lupi

Sculptor Salvatore Pisani was born on July 20 1859 in Mongiana, Calabria, an area that was famous for its artists’ skill in chiseling and in the technique of damascening. Salvatore’s talent was spotted by Giuseppe Albonico, an engineer from northern Italy who introduced him to art lover and senator Luigi Torelli.

After modelling Alessandro Manzoni’s bust under the supervision of famous sculptor Giulio Monteverde in 1875, in 1876 Salvatore enrolled at the Accademia di Brera. He then started working for an illustrious clientele, realising bust portraits of several army generals in 1880 and two low reliefs for the funerary chapel of painter Francesco Hayez in Milan in 1883.

Other important works by Pisani include two angels and King Rehoboam for the Duomo in Milan (1892 and 1893), the monument to Giovanni Battista Piatti in Largo La Foppa in Milan (1894) and the bust of Marquise Isimbardi Taverna (1906). He died in Milan on 18 September 1920.

Reference: Salvatore Pisani, Artisti Pisani.it

Further reading:

Domenico Pisani. Salvatore Pisani scultore, 1859-1920. Pizzo Calabro: Edizioni Esperide, 2012.

Little shepherdess, 1885, marble, unknown location.

Bust of Count Genova di Thaon di Revel, 1911, bronze, Museo della Battaglia di San Martino.

Angel and King Rehoboam, 1893, marble, pinnacle Cesa-Bianchi, Duomo, Milan.

Giovanni Battista Piatti, 1894, Largo La Foppa, Milan.

Portrait of Marquise Carolina Isimbardi Taverna, 1906, marble, Sala Isimbardi, Palazzo Isimbardi taverna, Milan.

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean-Jacques Henner, Little shepherdess, 1892

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

References

Beam, K. (1989). Small Fates [etching on Arches paper]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Carr, E. (1929). The Indian Church [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Chambers, J. (1961). Portrait of Marion and Ross Woodman [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Dongen, K.V. (1910). The Purple Garter [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Irvine, R. (1816). View of York [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Kane, P. (1845-1846). Scene in the Northwest: Portrait of John Henry Lefroy [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Lyall, L.M. (1898). Interesting Story [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Masse, B. (1967). Grateful Dead, Daily Flash, The Collectors, Love-In, Painted Ship [two colour offset lithograph on paper]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Masse, B. (1967). The Doors, The Collectors, Painted Ship [two colour offset lithograph on paper]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Masse, B. (1996). Hootie and the Blowfish, Speech, 54-40 [two colour offset lithograph on paper]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Master, J. (late 1400's). The Crucifixion [oil on panel lined with fabric]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Milne, D.B. (1915). The Suburbs [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Peel, P. (1892). The Little Shepherdess [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Pootoogook, A. (2001-2002). Eating in the Corner of a Tent [Coloured pencil, black and red porous-point pen, traces of graphite on paper]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Pootoogook, A. (2006). Hunter Mimicks Seal [Coloured pencil, black porous-point pen on paper]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

Tissot, J. (1883-1885). The Shop Girl [oil on canvas]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON.

0 notes

Photo

The Little Shepherdess by Paul Peel, 1892 (detail)

312 notes

·

View notes