#the life quality here is incomparable to what we had in brazil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I don’t know if i will be able to write here and in my multi today. My husband and i just read the news Canada’s government about the new immigration plans for permanent residency and……everything is very disappointing and heartbreaking tbh and i have no writing mood since we spent the whole day crying and redoing our plans. So yeah. 🥲

#ღ ⸻ jane speaks .#tw vent#tw politics#i understand why the government had to change the plans once again#its election year and canadians are very pissed with the government#for allowing easy entry to immigrants to their country#and that reached a proportion where everyone is not happy here lmao#but i am also allowed to feel sad bc we love this country#and we don’t want to leave#the life quality here is incomparable to what we had in brazil#but we can’t stay here if we don’t have the permanent residence#we applied for it months ago and are still waiting to be called and to be approved#and now we had this news that they are going to limit it#and there’s a 90% of change that we might come back to brazil next year if we don’t get called#that’s so sad and heartbreaking#anyways sorry for this rant vent#i had to put what i am feeling somewhere

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

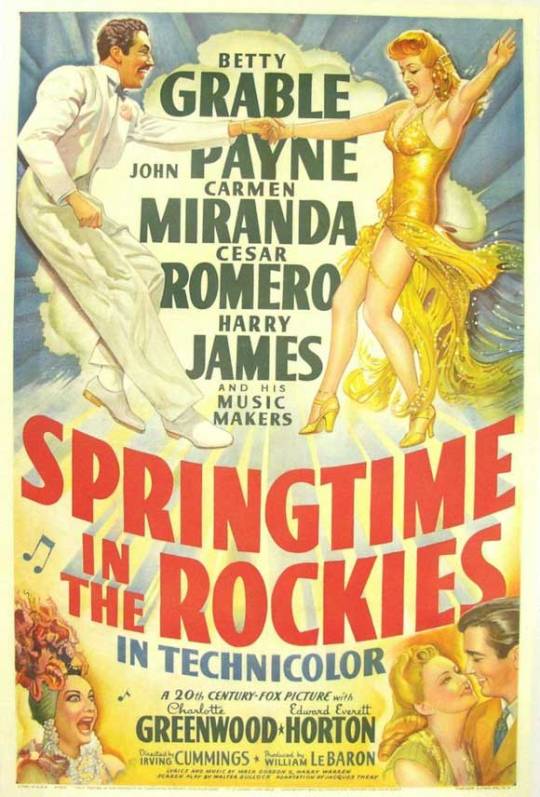

Springtime in the Rockies (1941)

This week we’re looking at the 1941 musical comedy Springtime in the Rockies, purportedly starring John Payne and Betty Grable but really a vehicle for the incomparable Carmen Miranda. It tells the story of a Broadway actor whose two-timing ways lose him a fiancee. Remorseful and desperate for another hit production, he drunkenly decides to track her down in the gorgeous Canadian Rockies, where she’s sort-of-but-not-really fallen for Cesar “The Best Joker” Romero. It’s not bad, kind of a predictable combination of the prewar-style backstage musical and post-Hawks romantic comedy, a nice swing soundtrack if you’re into that sort of thing.

But it’s 100% worth watching for Carmen Miranda, who looms large over the entire production, her sheer goofy presence tearing through the rote screwball proceedings like a big, gay comet. No tutti-frutti hats for the Brazilian Bombshell this go-round, just ruffles, arched brows and an ear-to-ear grin. She sings Chattanooga Choo-Choo in Portuguese. Chattanooga Goddamn Choo-Choo. It could have been embarrassing if it weren’t so fun to watch, if she wasn’t so charismatic and captivating.

youtube

Miranda is iconic. I knew about her in preschool thanks to grey market Daffy Duck videos, not by name of course, but there must have been a good reason that Daffy Duck was wearing bangles and fruit on his head, thrusting his hips and singing “chica-boom.” Carmen Miranda was (at the time of Springtime in the Rockies’ debut) something of a national embarrassment to Brazil, a kind of Larry the Cable Guy-style ugly stereotype, a caricature of folk culture and national identity, a cultural ambassador that made her culture look ridiculous--according to the humorless rich assholes that constituted the Brazilian cultural elite. The Brazilian leftist avant-pop movement of the 1960s, tropicália, eventually reclaimed her as a positive, sincere camp figure. Caetano Veloso, one of the central figures in tropicália (and a musician you should listen to immediately), mentions her in a song named for the movement, which sounds way less subversive than it apparently was. He later spoke of his attraction to Miranda as a camp cultural icon:

You want to bring in an object that’s culturally repulsive, so you go embrace it and then you dislocate it. Then you start to realize why you chose that particular object, you begin to understand it, and you realize the beauty in the object, the tragedy involved in its relationship with humanity...and finally you begin to love it...But before that, there’s a moment when you arrive at that neutral point, when you become uncritical in relation to that object. This was the case with Andy Warhol, who I think stayed at that point right to the end of his life: you cannot think that he is saying: “Look how this is tacky, kitsch, horrible, we should transcend it.” Not at all; he’s at that neutral point when the object is just the object: Bang! It’s in your face and it has nothing to say about itself. So Carmen Miranda, at the time that I wrote “Tropicália,” had reached that point of neutrality for me...She had been recovered: a kind of salvation.

[Dunn, 91-92.]

Veloso’s comments gesture towards the idea of camp as analytic strategy, a way of engaging with an artifact rather than an innate set of qualities. Carmen Miranda only becomes camp if she is approached as such, fruit hats notwithstanding. His notion of “dislocation” and neutrality is particularly interesting, especially in relation to his overtly empathetic reading of Miranda (her “tragedy”). Sontag posits that this detachment is critical to camp’s ironic sensibility, that “tragedy is an experience of hyperinvolvement [i.e. a sincere, serious reading of the artifact-as-account], comedy is an experience of underinvolvement [i.e. an ironic, aesthetic reading of artifact-as-artifact]” and that “Detachment is the prerogative of a[ cultural] elite”--that is, the strategy/discourse of camp hinges upon deliberately identifying artifacts as such (Sontag, 288).

youtube

To approach Carmen Miranda as an accurate account of prewar Brazilian “national character” or folkways is perhaps missing the point, but to approach Carmen Miranda as an icon, a complete “thing” that exists within the cultural consciousness as a complete “thing” regardless of Brazilian (or global) social/cultural history allows the audience to engage with her as a total aesthetic experience unto herself. Her screen presence betrays the illusory aspect of Hollywood: Carmen Miranda is not an actress playing Rosita Murphy (Sontag, 285-6). Her actions, gestures, vocal tics, outward appearance and dress reveal only Carmen Miranda the person generating and performing the the set of ideas and behaviors that supplant the individual with the “Carmen Miranda-icon” (Foucault, 128).

Betty Grable isn’t a particularly good actress either, but she also lacks the silliness and charisma that makes Carmen Miranda so fun to watch. Whereas Miranda commands your attention, Grable is just kind of there. She’s a movie star rather than a transcendent image, an individual without individual character (Sontag, 285-6). Grable’s weird line readings aren’t bad in a funny way because, unlike Miranda, her weird line readings aren’t meant to sound unnatural. Grable’s foil, played by lanky vaudevillian Charlotte Greenwood, isn’t as overwhelming a presence as Miranda, but at least her bizarre hoedown high kicks, shown at the end of the clip above, are a riot. Here’s an example from another film, Down Argentina Way. I could watch this woman dance all day.

youtube

The film ends with the “Pan American Jubilee,” shared earlier in the post. It’s bizarrely on-the-nose. Carmen Miranda’s US stardom is largely due to Hollywood’s involvement with FDR’s Good Neighbor policy, an effort to assuage Latin American anxieties over the United States’ military interventionism in the region throughout the first half of the twentieth century that had been spearheaded/legitimized by Theodore Roosevelt’s enforcement and expansion of the Monroe Doctrine (though it’s not like we ever stopped). The lyrics of the song explicitly mention being a “good neighbor,” which is jarring in the same way as hearing Bugs Bunny tell you to buy war bonds.

I heartily recommend this film, with the caveat that Carmen Miranda is the only thing that makes it worth seeking out. I realize that almost all of this post has been devoted to her but good lord, what a presence. Happy #NotMyPresidentsDay. We will return next week with the post-expressionist tour-de-force, The Scarlet Empress.

Sources

Dunn, Christopher. Brutality Garden: Tropicália and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Foucault, Michel. "What is an Author?" In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice, 113-38. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

Sontag, Susan. "Notes on Camp." In Against Interpretation, 275-92. New York: Delta, 1977.

#carmen miranda#campy#kitschy#betty grable#musical#cesar romero#old hollywood#golden age hollywood#good neighbor#fdr#notmypresident#bad taste#susan sontag#sontag#tropicalia#caetano veloso#bad movies#film#movies#foucault#michel foucault

0 notes