#the immutable spirit PUBLIC TRANSIT

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i love heart: dress to impress

#heart: the city beneath#crack#crixus#batyn#the immutable spirit PUBLIC TRANSIT#my art#the heart must beat

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

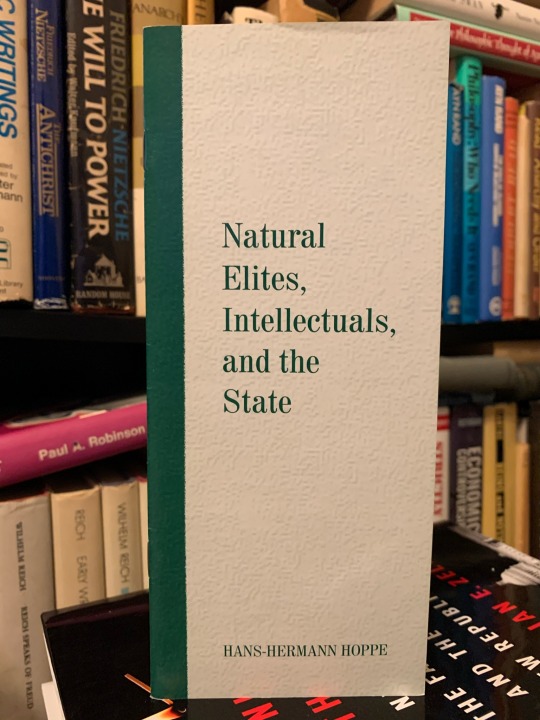

“A fundamental change in the relationship between the state, natural elites, and intellectuals only occurred with the transition from monarchical to democratic rule. It was the inflated price of justice and the perversions of ancient law by kings as monopolistic judges and peacekeepers that motivated the historical opposition against monarchy. But confusion as to the causes of this phenomenon prevailed. There were those who recognized correctly that the problem was with monopoly, not with elites or nobility. However, they were far outnumbered by those who erroneously blamed the elitist character of the ruler for the problem, and who advocated maintaining the monopoly of law and law enforcement and merely replacing the king and the highly visible royal pomp with the "people" and the presumed decency of the "common man." Hence the historic success of democracy.

How ironic that monarchism was destroyed by the same social forces that kings had first stimulated and enlisted when they began to exclude competing natural authorities from acting as judges: the envy of the common men against their betters, and the desire of the intellectuals for their allegedly deserved place in society. When the king's promises of better and cheaper justice turned out to be empty, intellectuals turned the egalitarian sentiments the kings had previously courted against the monarchical rulers themselves. Accordingly, it appeared logical that kings, too, should be brought down and that the egalitarian policies, which monarchs had initiated, should be carried through to their ultimate conclusion: the monopolistic control of the judiciary by the common man. To the intellectuals, this meant by them, as the people's spokesmen.

As elementary economic theory could predict, with the transition from monarchical to democratic one-man-one-vote rule and the substitution of the people for the king, matters became worse. The price of justice rose astronomically while the quality of law constantly deteriorated. For what this transition boiled down to was a system of private government ownership — a private monopoly — being replaced by a system of public government ownership — a publicly owned monopoly.

A "tragedy of the commons" was created. Everyone, not just the king, was now entitled to try to grab everyone else's private property. The consequences were more government exploitation (taxation); the deterioration of law to the point where the idea of a body of universal and immutable principles of justice disappeared and was replaced by the idea of law as legislation (made, rather than found and eternally "given" law); and an increase in the social rate of time preference (increased present-orientation).

A king owned the territory and could hand it on to his son, and thus tried to preserve its value. A democratic ruler was and is a temporary caretaker and thus tries to maximize current government income of all sorts at the expense of capital values, and thus wastes.

(...)

While the state fared much better under democratic rule, and while the "people" have fared much worse since they began to rule "themselves," what about the natural elites and the intellectuals? As regards the former, democratization has succeeded where kings made only a modest beginning: in the ultimate destruction of the natural elite and nobility. The fortunes of the great families have dissipated through confiscatory taxes, during life and at the time of death. These families' tradition of economic independence, intellectual farsightedness, and moral and spiritual leadership have been lost and forgotten.

Rich men exist today, but more frequently than not they owe their fortunes directly or indirectly to the state. Hence, they are often more dependent on the state's continued favors than many people of far-lesser wealth. They are typically no longer the heads of long-established leading families, but "nouveaux riches." Their conduct is not characterized by virtue, wisdom, dignity, or taste, but is a reflection of the same proletarian mass-culture of present-orientation, opportunism, and hedonism that the rich and famous now share with everyone else. Consequently — and thank goodness — their opinions carry no more weight in public opinion than most other people's.

Democracy has achieved what Keynes only dreamt of: the "euthanasia of the rentier class." Keynes's statement that "in the long run we are all dead" accurately expresses the democratic spirit of our times: present-oriented hedonism. Although it is perverse not to think beyond one's own life, such thinking has become typical. Instead of ennobling the proletarians, democracy has proletarianized the elites and has systematically perverted the thinking and judgment of the masses.

On the other hand, while the natural elites were being destroyed, intellectuals assumed a more prominent and powerful position in society. Indeed, to a large extent they have achieved their goal and have become the ruling class, controlling the state and functioning as monopolistic judge.

This is not to say that democratically elected politicians are all intellectuals (although there are certainly more intellectuals nowadays who become president than there were intellectuals who became king.) After all, it requires somewhat different skills and talents to be an intellectual than it does to have mass-appeal and be a successful fundraiser. But even the non-intellectuals are the products of indoctrination by tax-funded schools, universities, and publicly employed intellectuals, and almost all of their advisors are drawn from this pool.

There are almost no economists, philosophers, historians, or social theorists of rank employed privately by members of the natural elite. And those few of the old elite who remain and who might have purchased their services can no longer afford intellectuals financially. Instead, intellectuals are now typically public employees, even if they work for nominally private institutions or foundations. Almost completely protected from the vagaries of consumer demand ("tenured"), their number has dramatically increased and their compensation is on average far above their genuine market value. At the same time the quality of their intellectual output has constantly fallen.

What you will discover is mostly irrelevance and incomprehensibility. Worse, insofar as today's intellectual output is at all relevant and comprehensible, it is viciously statist. There are exceptions, but if practically all intellectuals are employed in the multiple branches of the state, then it should hardly come as a surprise that most of their ever-more voluminous output will, either by commission or omission, be statist propaganda. There are more propagandists of democratic rule around today than there were ever propagandists of monarchical rule in all of human history.

This seemingly unstoppable drift toward statism is illustrated by the fate of the so-called Chicago School: Milton Friedman, his predecessors, and his followers. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Chicago School was still considered left-fringe, and justly so, considering that Friedman, for instance, advocated a central bank and paper money instead of a gold standard. He wholeheartedly endorsed the principle of the welfare state with his proposal of a guaranteed minimum income (negative income tax) on which he could not set a limit. He advocated a progressive income tax to achieve his explicitly egalitarian goals (and he personally helped implement the withholding tax). Friedman endorsed the idea that the State could impose taxes to fund the production of all goods that had a positive neighborhood effect or which he thought would have such an effect. This implies, of course, that there is almost nothing that the state can not tax-fund!

In addition, Friedman and his followers were proponents of the shallowest of all shallow philosophies: ethical and epistemological relativism. There is no such thing as ultimate moral truths and all of our factual, empirical knowledge is at best only hypothetically true. Yet they never doubted that there must be a state, and that the state must be democratic.

Today, half a century later, the Chicago-Friedman school, without having essentially changed any of its positions, is regarded as right-wing and free-market. Indeed, the school defines the borderline of respectable opinion on the political Right, which only extremists cross. Such is the magnitude of the change in public opinion that public employees have brought about.

Consider further indicators of the statist deformation brought about by the intellectuals. If one takes a look at election statistics, one will by and large find the following picture: the longer a person spends in educational institutions, someone with a PhD, for instance, as compared to someone with only a BA, the more likely it is that this person will be ideologically statist and vote Democrat. Moreover, the higher the amount of taxes used to fund education, the lower SAT scores and similar measurements of intellectual performance will fall, and I suspect even further will the traditional standards of moral behavior and civil conduct decline.

Or consider the following indicator: in 1994 it was called a "revolution" and Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, was called a "revolutionary" when he endorsed the New Deal and Social Security, and praised civil rights legislation, i.e., the affirmative action and forced integration which is responsible for the almost complete destruction of private property rights, and the erosion of freedom of contract, association, and disassociation. What kind of a revolution is it where the revolutionaries have wholeheartedly accepted the statist premises and causes of the present disaster? Obviously, this can only be labeled a revolution in an intellectual environment that is statist to the core.

(...)

The situation appears hopeless, but it is not so. First, it must be recognized that the situation can hardly continue forever. The democratic age can hardly be "the end of history," as the neoconservatives want us to believe, for there is also an economic side to the process.

Market interventions will inevitably cause more of the problems they are supposed to cure, which leads to more and more controls and regulations until we finally reach full-blown socialism. If the current trend continues, it can safely be predicted that the democratic welfare state of the West will eventually collapse as did the "people's republics" of the East in the late 1980s. For decades, real incomes in the West have stagnated or even fallen. Government debt and the cost of the "social insurance" schemes have brought on the prospect of an economic meltdown. At the same time, social conflict has risen to dangerous heights.

Perhaps one will have to wait for an economic collapse before the current statist trend changes. But even in the case of a collapse, something else is necessary. A breakdown would not automatically result in a roll-back of the State. Matters could become worse.

In fact, in recent Western history, there are only two clear-cut instances where the powers of the central government were actually reduced, even if only temporarily, as the result of a catastrophe: in West Germany after World War II under Ludwig Erhard, and in Chile under General Pinochet. What is necessary, besides a crisis, is ideas — correct ideas — and men capable of understanding and implementing them once the opportunity arises.

But if the course of history is not inevitable (and it is not) then a catastrophe is neither necessary nor unavoidable. Ultimately, the course of history is determined by ideas, be they true or false, and by men acting upon and being inspired by true or false ideas. Only so long as false ideas rule is a catastrophe unavoidable. On the other hand, once correct ideas are adopted and prevail in public opinion — and ideas can, in principle, be changed almost instantaneously — a catastrophe will not have to occur at all.

This brings me to the role intellectuals must play in the necessary radical and fundamental change in public opinion, and the role that members of the natural elites, or whatever is left of them, will also have to play. The demands on both sides are high, yet as high as they are, to prevent a catastrophe or to emerge successfully from it, these demands will have to be accepted by both as their natural duty.

Even if most intellectuals have been corrupted and are largely responsible for the present perversities, it is impossible to achieve an ideological revolution without their help. The rule of the public intellectuals can only be broken by anti-intellectual intellectuals. Fortunately, the ideas of individual liberty, private property, freedom of contract and association, personal responsibility and liability, and government power as the primary enemy of liberty and property, will not die out as long as there is a human race, simply because they are true and the truth supports itself. Moreover, the books of past thinkers who expressed these ideas will not disappear. However, it is also necessary that there be living thinkers who read such books and who can remember, restate, reapply, sharpen, and advance these ideas, and who are capable and willing to give them personal expression and openly oppose, attack, and refute their fellow intellectuals.

Of these two requirements — intellectual competency and character — the second is the more important, especially in these times. From a purely intellectual point of view, matters are comparatively easy. Most of the statist arguments that we hear day in and out are easily refuted as more or less economic nonsense. It is also not rare to encounter intellectuals who in private do not believe what they proclaim with great fanfare in public. They do not simply err. They deliberately say and write things they know to be untrue. They do not lack intellect; they lack morals. This in turn implies that one must be prepared not only to fight falsehood but also evil — and this is a much more difficult and daring task. In addition to better knowledge, it requires courage.

As an anti-intellectual intellectual, one can expect bribes to be offered — and it is amazing how easily some people can be corrupted: a few hundred dollars, a nice trip, a photo-op with the mighty and powerful are all too often sufficient to make people sell out. Such temptations must be rejected as contemptible. Moreover, in fighting evil, one must be willing to accept that one will probably never be "successful." There are no riches in store, no magnificent promotions, no professional prestige. In fact, intellectual "fame" should be regarded with utmost suspicion.

Indeed, not only does one have to accept that he will be marginalized by the academic establishment, but he will have to expect that his colleagues will try almost anything to ruin him. Just look at Ludwig von Mises and Murray N. Rothbard. The two greatest economists and social philosophers of the 20th century were both essentially unacceptable and unemployable by the academic establishment. Yet throughout their lives, they never gave in, not one inch. They never lost their dignity or even succumbed to pessimism. On the contrary, in the face of constant adversity, they remained undaunted and even cheerful, and worked at a mind-boggling level of productivity. They were satisfied in being devoted to the truth and nothing but the truth.

It is here that what is left of the natural elites comes into play. True intellectuals, like Mises and Rothbard, can not do what they need to do without the natural elites. Despite all obstacles, it was possible for Mises and Rothbard to make themselves heard. They were not condemned to silence. They still taught and published. They still addressed audiences and inspired people with their insights and ideas. This would not have been possible without the support of others. Mises had Lawrence Fertig and the William Volker Fund, which paid his salary at NYU, and Rothbard had The Ludwig von Mises Institute, which supported him, helped publish and promote his books, and provided the institutional framework that allowed him to say and write what needed to be said and written, and that can no longer be said and written inside academia and the official, statist establishment media.

Once upon a time, in the pre-democratic age, when the spirit of egalitarianism had not yet destroyed most men of independent wealth and independent minds and judgments, this task of supporting unpopular intellectuals was taken on by individuals. But who can nowadays afford, single-handedly, to employ an intellectual privately, as his personal secretary, advisor, or teacher of his children? And those who still can are more often than not deeply involved in the ever more corrupt big government-big business alliance, and they promote the very same intellectual cretins who dominate statist academia. Just think of Rockefeller and Kissinger, for instance.

Hence, the task of supporting and keeping alive the truths of private property, freedom of contract and association and disassociation, personal responsibility, and of fighting falsehoods, lies, and the evil of statism, relativism, moral corruption, and irresponsibility can nowadays only be taken on collectively by pooling resources and supporting organizations like the Mises Institute , an independent organization dedicated to the values underlying Western civilization, uncompromising and far removed even physically from the corridors of power. Its program of scholarships, teaching, publications, and conferences is nothing less than an island of moral and intellectual decency in a sea of perversion.

To be sure, the first obligation of any decent person is to himself and his family. He should — in the free market — make as much money as he possibly can, because the more money he makes, the more beneficial he has been to his fellow man.

But that is not enough. An intellectual must be committed to the truth, whether or not it pays off in the short run. Similarly, the natural elite have obligations that extend far beyond themselves and their families.

The more successful they are as businessmen and professionals, and the more others recognize them as successful, the more important it is that they set an example: that they strive to live up to the highest standards of ethical conduct. This means accepting as their duty, indeed as their noble duty, to support openly, proudly, and as generously as they possibly can the values that they have recognized as right and true.”

#hans hermann hoppe#hoppe#libertarianism#liberty#anarchocapitalism#anarchism#rothbard#mises#state#elites#intellectuals#milton friedman#newt gingrich#monarchy#democracy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Old Thing

Whether it is small things like utensils or big things like furniture and buildings, the spirit of the time that infused into these things is immutable even if abandoned by time, because there is “human” being there. And the “Water House” on the Huangpu River in Shanghai, China is a very good example. The building itself was converted from a three-story Japanese military headquarters built in the 1930s. Based on the integration of “new” and “old” and the sharp contrast, the designers remodeled this building. The original concrete structure was retained and restored, and the weathering steel of the existing structure was added to the statue describing the industrial background of this shipping terminal on the bank of the Huangpu River.

Rough concrete facade and rust plate showing a original industrial style. By the designer’s clever idea, the architecture once again injected into the contemporary soul, and gained a new life. They naturally take the traces of time, with years of precipitation elegant, seriours look, but found it all seems to be new.

The renovation of the Water House hotel is a good illustration of the continuation of the old things, reflecting the natural continuation on the way of thinking. Thinking from all is the extension and interrelationships of things.

Back to the past, there was more examples of building a garden because of a wasteland. The garden may originate in an old tree, a pond, a period of foundation. Is it possible that a set of old doors and windows can cause a construction activity that makes differences in a new building, or change the initial idea of a design for a few pieces of stone? Here is a particularly issue that our creation is more derived from the concept or a natural continuation of matters and the body.

The continuation of doors and windows creates a room. The continuation of stones creates a garden. It is windows and doors that almost decide the room, and it is the normal stone that decide the courtyard.

Now, the public needs are also shifted from superficial sophistication to lifestyle sophistication. During this important transition period (from nothing to something, from good to better), blind dazzle has become impracticable and designers should examine the issue from different angles. All the ideas should be made from nature and back to basics. By digging deeper into the significance of the place and by making most of the conditions at a specific time and in a specific area, we create the architecture and landscape rooted in the local culture and environment. This is what I think natural architecture.

1 note

·

View note

Text

New top story from Time: How TIME’s Reporting on Gay Life in America Shaped—and Skewed—a Generation’s Attitudes

Editor’s note: At TIME, we aim to apply the same scrutiny to ourselves that we do to the world. In that spirit, TIME is publishing this article by Eric Marcus, author of Making Gay History.

TIME magazine helped me come out to my mother. Inadvertently. It was June 1977 and I was back in home Queens, N.Y., from my first year at Vassar College. At school I’d haltingly made my way out of the closet — transitioning from a first-semester girlfriend to a second-semester boyfriend and torturing myself (and the girlfriend and boyfriend both) over knowing what I wanted and hating who I was because I’d failed to drive those feelings away.

Over lunch one afternoon at our kitchen table, with the latest issue of TIME turned to an article about Anita Bryant’s successful campaign to repeal a gay-rights bill in Dade County, Fla., I raged over the injustice of both Bryant’s assertion that gay people were a danger to children and the cowardly legislators who caved to prejudice and ignorance. Unknowingly, my red-faced outrage offered another clue to my mother that there was more than a little self-interest at stake for me in the fate of the gay civil-rights movement. Weeks later, she would ask me if I was gay.

It wasn’t until more than a decade later, when I began researching an oral-history book on what was then called the gay and lesbian civil-rights movement, that I realized that TIME magazine had also played a role in shaping how my mother thought of homosexuals — and how she’d come to view her teenaged gay son.

In my research, as I struggled to gain an understanding of why people saw homosexuals as sick, sinful and criminal, I stumbled on a 1966 essay in TIME that just about burned the skin off my face as I read it. I think it was meant as a meditation on what to make of the then-growing visibility of gay life in America. But while it’s couched as enlightened analysis, it now reads as shockingly regressive. (There was no byline, which was the norm for the magazine at the time.) To this day, there are words and phrases from that essay that I can recite from memory: Deviate. Witty, pretty, catty, and no problem to keep at arm’s length. Caused psychically, through a disabling fear of the opposite sex. A case of arrested development. A pathetic little second-rate substitute for reality, a pitiable flight from life. No pretense that it is anything but a pernicious sickness. Had my mother read that essay? Did she recall those words when I responded to her question with a shaky “yes”?

As I came to discover, TIME wasn’t alone. The media in those years, as is most often the case today, reflected society’s prevailing views about homosexuals. Back then, homosexuality was still considered a treatable mental illness, sexual relations between two people of the same sex could get you arrested in almost every state, and thousands — perhaps tens of thousands — of gay men and lesbians had been hounded out of federal employment since President Eisenhower signed an executive order in 1953 banning them from government jobs. In New York, a state law about “disorderly” conduct was interpreted as making it illegal to serve known homosexuals alcohol, and the police routinely raided gay bars.

The now-celebrated 1969 Stonewall uprising — triggered by a police raid of the Stonewall Inn gay bar — which is being marked this month by 50th anniversary celebrations, marches and protests, got a particularly pungent headline in the New York Daily News: “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad.” The Village Voice, an alternative downtown newspaper, published an article in the immediate aftermath of the first night of rioting in which the reporter used a slur to refer to the uprising’s participants, earning the Voice, just days after the start of the uprising, one of the first public protests that would come to characterize the newly militant era of “gay liberation.”

TIME, which didn’t cover the uprising, gave prominent play to the rage and wave of activism unleashed in the weeks and months that followed. The Oct. 31, 1969, cover story was headlined “The Homosexual: Newly Visible, Newly Understood.” The magazine got the “newly visible” part right. The piece displays an overall attempt at straightforward reporting, a marked change from the tone of three years prior. And yet the picture the article painted of the “newly understood” homosexual was still dripping with sarcasm and contempt. One section of the report noted several “types” of homosexuals: “The Blatant Homosexual,” “The Secret Lifer,” “The Desperate,” “The Adjusted,” “The Bisexual,” “The Situational-Experimental.” After describing these different categories, the writer notes: “The homosexual subculture, a semi-public world, is, without question, shallow and unstable.”

Although that cover story also said some comparatively nice things about homosexuals, is it any wonder members of the newly formed Gay Liberation Front and the Daughters of Bilitis (an organization for lesbians founded in 1955 in San Francisco) picketed the Time-Life building after its publication? On Nov. 12, 1969 — my 11th birthday — demonstrators handed out leaflets, which read: “In characteristic tight-assed fashion, Time has attempted to dictate sexual boundaries for the American public and to define what is healthy, moral, fun, and good on the basis of its own narrow, outdated, warped, perverted, and repressed sexual bias.” Gay people weren’t going to take it anymore.

When I told my mother eight years later that yes, I was gay, she just looked at me with a blank stare. Was she trying to figure out what kind of homosexual I was? A no-longer-secret lifer? Desperate? An experimenter? Definitely not adjusted. In truth, I was a depressed gay teenager who feared that his life was ruined because of this one, immutable flaw. But I wasn’t about to tell my mother that. I responded with a question of my own: “Do you feel guilty?” I’d come to understand from the research I’d done in the Vassar College library that parents of gay children often felt that it was their own fault (also thanks to TIME and all the other news outlets and so-called experts who blamed homosexuality on a dominant mother and passive father). My mother said that she didn’t feel guilty, that she was disappointed. I would rather she had felt guilty. Her disappointment left me in tears.

In the years that followed, change came — but not rapidly, and with more effort and heartbreak than I’d imagined it would take. TIME, like every other major news outlet, shifted away from parroting society’s prejudice and misunderstanding to more honest and balanced reporting. Even before my mother asked me that fateful question, TIME had published a cover story on Leonard Matlovich, who was challenging the ban on gay people serving in the military. That and subsequent cover stories — the 1997 Ellen DeGeneres “Yep, I’m Gay” cover or the 2014 Laverne Cox cover about transgender civil rights, for example — helped reshape in a positive way how people like me thought of ourselves and how the rest of the world saw us.

Courtesy Eric MarcusMarcus and his mother at the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation

My mother came around, too, and by the early 1990s was an activist in her own right, volunteering to lead a support group for gay men whose partners had died from AIDS and helping found the Queens chapter of PFLAG (once known as Parents, Families and Friends, of Lesbians and Gays). Mom died 15 years ago and I wonder what she would have made of the recent TIME cover story on presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg and his husband Chasten under the headline “First Family.”

Actually, I don’t have to wonder. Knowing my mother she’d have the magazine’s cover taped to her refrigerator — her makeshift vision board — and would be on the phone to me, wanting to know if I could get her tickets to the inauguration.

Eric Marcus is the author of Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal Rights and the founder and host of a podcast of the same name. Learn more at www.makinggayhistory.com.

via https://cutslicedanddiced.wordpress.com/2018/01/24/how-to-prevent-food-from-going-to-waste

0 notes

Text

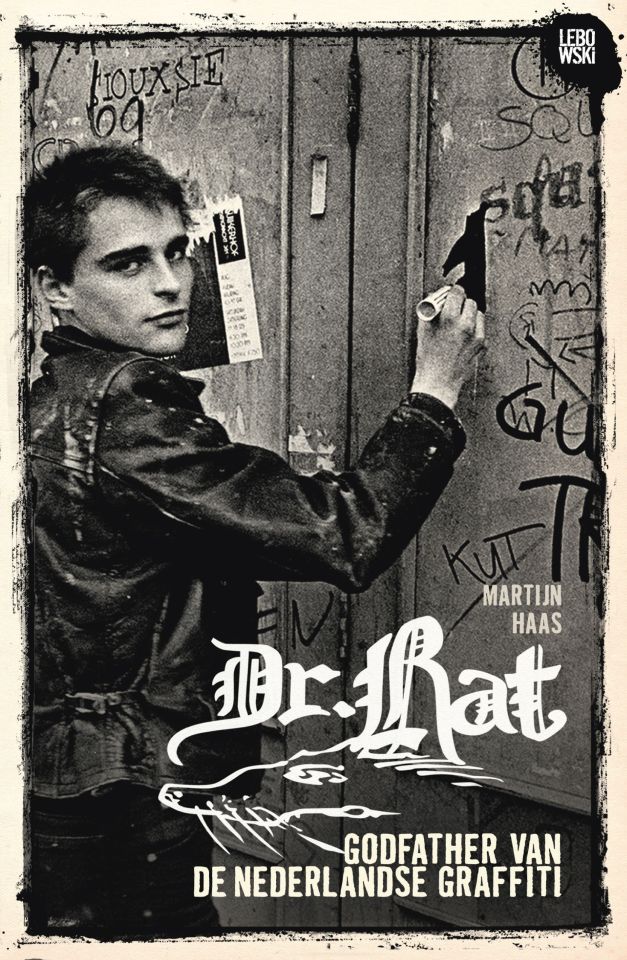

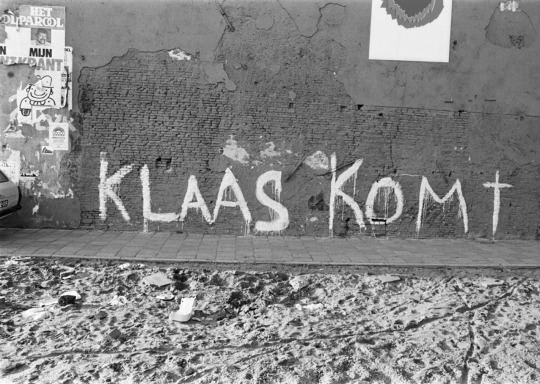

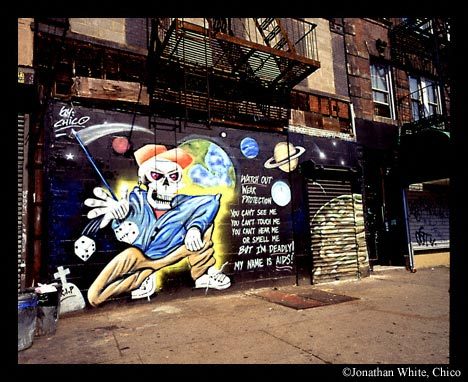

Graffiti - from Writing to Urban Art: a fluid journey towards tomorrow

Street Art Museum Amsterdam have asked the famous expert on graffiti and urban art from Madrid Dr. Figueroa Saavedra to share his thoughts on the evolution of this contemporary art movement. DrGraphitfragen has helped Muelle to get the recognition of the city management - one of the first streets in the world to carry the name of the first graffiti writer is in Madrdid.

ENGLISH: If something has characterised and made Graffiti great, if something explains the transit from Writing to Spray can Art, it is the attention given by writers to the graphic and its aesthetic dimension. It was made with so much passion that intended up becoming a fundamental factor of individual self-realization, a communicatory place and distinctive part of a subculture—later an international movement—which expressed before all freedom and interculturalism.

For this reason, it is complicated to understand the emergence of 21st century Urban Art without paying attention to the genesis and definition of the Writing Graffiti in 20th century. Both processes are child of the same germen, which made them to share the same pavement. Graffiti, with its vitality, autonomy and popular fortune, is, however, the true vanguard of street art in the current century.The Style Wars, in New York of the end of the 70 and the early 80s, were not more than the public declaration that artistic creativity is one of the fundamental pillars of Graffiti.

It characterized it as a frontier art, autonomous at the face of the artistic ecosystem and parallel to those branches of Public Art that are entrusted, or commissioned or monitored, by the public administration and even to omnipresent advertising language. The willingness of design and style triggered an aesthetic movement and an existential life experience, in which the creativity was merit, talent, emotion, affection and co-existence. The Graffiti not only covered trains and walls but also penetrated the mass culture and the high culture galleries, establishing a perpetual interchange of materials with those spheres. It also could connect with its social and cultural reality, jellying its aesthetics as a sign of the new times emerging after the 1973 crisis and giving itself in flesh and soul to the young effervescence of the 80s.

Thus, its childish glance grew up and flourished, absorbing in its spirit the hippie hedonism, the vitality of rock and the rebelliousness of the 70s punk, without leaving aside in its development the combination of nutrients offered by comic, TV, cinema, vinyl’s covers, graphic design, publicity, advertisements, and the cult to the fame expressed in neon lights and screen flashes. Afterwards, the flood of Hip Hop would drag graffiti into refreshing and rhythmic vibes. This took place under the consolidated world-empire of consumerism and the conversion of a combative counter culture into a subculture of resistance. In this context, the corner boy became a neighbourhood superhero, whose psych-evolutive development would make him aware of an adult reality of which he knew he could never belong to. The memorials and other civic murals, which were produced by some writers, became the reflex of the writer’s involvement with its neighbourhood, civil society, the people and its own destiny; always from its own personal glance and fashion.

Meanwhile, while graffiti of signature and “masterpiece” (spraycan art piece) was consolidating on one hand, on the other side of the Atlantic, other street art experiences were being thriving since the 60s. These experiences were at the margin of the official culture, from the framework of popular culture, art world and cultural activism. Postmodernism was born and it had aspirations to remain, it spread itself in each single corner of the western culture, embracing all sort of creative phenomena.

From the “provos” to the hippies to the punk, passing by the Internationale Situationniste, social and political muralism of the 70s, Neo-expressionism or Figuration Libre, or that array of French serigraphysts, in all these movements it was conveyed the living interest for expression without censorship, with creativity and a mix of faith and mocking, publicly, in society, and to take art to the streets to fuse it with life, without more frontier than the limits of the imagination. It was time to annihilate the notion of art as merchandise, underlie its communitarian and un-elitist character, to democratise its access and practice in public spaces. Public spaces had to be taken and left them open and shared. In sum, it is a space lived and enjoyed by an autonomous community.

Doubtlessly, what gathered writers and other graffiti writers and public or urban artists was an epochal air which resumed itself in the opening borders and freedom to action. It was about amplifying the mental horizons of society, its consciousness of the possible and positive, its vision of a future and framework of different interrelations, forged in self-improvement, concord and plurality as opposed to the hostility of a frustrating reality. Yet the movement has not yet shown the severity of its castrating facet.

However, and despite of the worldly pressures and prosecutions of the 90s, no one thought to abandon the idea of an opened or underground visual shock as warranty of a direct and sudden contact with the spectator. It was its own interpretation of an aesthetical-vital experience at the margins of the mass media, but that reproduced or simulated or exaggerate its dynamism and imperative existence. They were sons of a technological era with artcraft mentality. Thus was that the world of graffiti, after of its concretization and as we know it today, passed from being encumbered as Aerosol Art to suffer the spectacular criminalizing whirlpool coming from states.

As Norman Mailer puts it in his The Faith of Graffiti (1974), this was the Vietnamization of the graffiti phenomenon. The systematic and unproportioned belligerent prohibition of graffiti consecrated illegality as a characteristic feature of Hip Hop Graffiti of the 90s (and today); just in the moment where graffiti fell in a crisis and withdrew itself to cultural marginality of neighbours and periphery. No one reacted against such climax of social castration, due to energy of the new generations who replaced the local old schools and to the fact that Hip Hop Graffiti extended itself freshly over Eastern Europe and Latino-America; thus showing its force. Hence renascence, with its acts of vandalism but, at the same time, its artistic entity. Vandalism and art, however, will many times appear and be assumed as disjunctives.

At this point, an entity and identity reflection took place within the graffiti culture. It was time to look backwards, rethink the past, not to doss, take breath and go forward over a lightless tunnel. To some, this reflection came with the opportunity to set aside powerful burdens of the tradition. Some active vets and new writers left the orthodoxy of the old school to give place to their experimental “pulsion” and make graffiti grow with more illusion than fear, with adult vigour and child’s faith.The impression that all the previous stages have followed each other to create a unique and immutable model has been knocked down. There is no duty to reproduce the model with precision and reverence, the present is no longer a devaluated, non-returning golden past. Certainly, the aura of Graffiti was not limited to the idle imaginary of subway art of the 80s, as portrayed by Craig Castleman or Henry Chalfant.

Moreover, no one could imagine the dimension that graffiti would reach in the 21st century. Graffiti did not die in 1989.

It accommodated itself in its roots to see an obscure winter covered with a layer of frost transiting over its colours.From over the 90s, Hip Hop Graffiti would reinvigorate itself due, above all, to its taking consciousness of its character of a transgenerational movement and to the consolidation of a worldwide net of human collaboration and exchange of internal information that had never seen before in artistic movements; may be comparable with proposals in the world of music such as jazz and rock. Therefore emerging fanzines, specialized markets, the first webs geared at exhibiting graffiti art and fostering collaboration, national and international meetings and even the concretion of an own industry. Graffiti revolution within graffiti brought the possibility of having awareness of other street realities, mind opening, other styles creation, new techniques and bases, new techniques to endure, the development of the iconic, of the dynamic, of realism, expressionism, of the grotesque or informal, the exploration of textures, of reliefs, of the volumetric, the accentuation of the conceptual and the performative, the development of the metalinguistic aspect and the study of the relation between graffiti and other means of expression and communication, in sum, new strategies to keep the ‘getting-up’, the creative spirit of graffiti live and fresh.

Graffiti has grown up, in body and spirit and yet was facing a metamorphosis that would give place to something that looked like another thing: the Postgraffiti. This movement was manifested in the explosion of Iconism, Stencil Art, stickers, posters and urban spontaneous interventions. They themselves were not new things; their power and profusion were. It was about amplifying limits, tense them in the extreme while keeping the possibility of preserving graffiti as an art; this time with more integrity, after the infelicitous experiences of the 80s and first 90s. In this way, writers and artists would converge from different origins and goals in urban art of the 21st century, building innovative proposals from its grounding and aspirations, with the added difficulty of having to reach an equilibrium of respect with the public powers.

The transfer from Graffiti to Urban Art did not necessarily supposed a rupture with a certain mode of seeing and making things. The protagonists saw it as a conceptual expansion, an amplification of the graffiti consciousness, speech and capacity of action, always faithful to the concept of ‘no limits to fame’, which now became a motto of freedom and heterodoxy within the world of graffiti. Graffiti was born and always beats in streets, true. But it could reverberate in other ambits with the same passion. In any case, graffiti would keep itself as a solid movement, cohesioned, rich and international, which has shown a great capacity of integration and renovation. It is an incomparable community within the world of contemporary art, it is a past which grows every day and helps building a different reality.

At the doors of the 21st century, we see a new urban reality; very different to that of the 70s. In graffiti, a new poetic project emerged, it diversified physical objects, which can be static, mobiles and portable. Graffiti in this new era leads to hybrid pieces which integrate street action and expositive facet. Writers not only take possession of but also establish a face to face dialogue with architecture, urban furniture, and human surrounding and the other communicative codes that share space with graffiti. Graffiti would endorse social and political leitmotivs. All these new concerns were imperatives that were taking form along the new century and yielded graffiti not unheard, given its public vocation.

Aware of the prevailing social conventions, the well-established political truths and today’s world’s agony, we find in graffiti as opinions, criticisms, demands or hopes expressed grotesquely or poetically in walls become revolutionary acts. From their personal initiative or under the aegis of group initiatives, writers vertebrate themselves into social movements and cultural, political and social life. However, all is susceptible to a political and commercial instrumentalisation. Even rebelliousness would be a victim of such instrumentalisation, as it occurs with the use of urban artists in processes like gentrification or campaigns of institutional imagine building. Yet Graffiti, due to its special philosophy, tailors the dignifying life in the neighbourhood (barrio pride), bricklayer’s routine.

Moreover urban artists avoid being encapsulates as public artists, even though in seldom occasions. It is obvious that Urban Art and Graffiti exemplify that great human potential which is resumed in the mottos ‘do it yourself’ or ‘don’t stop’. Street Art looks like a polyhedron of one hundred faces, a figure capable of daringly give away a ‘just do it’ to society and the world of art, thereby appropriating and reinterpreting to parody the ‘American dream’. Graffiti talks to society to convince us that any adversity, conflict and fear will be overcome. We just have to have ourselves. Moreover, in its popular origin and outlook it pulses the nerve which makes some persons proclivity to understand life as a collective adventure and embark themselves to redefine society without more arms than a spray can charged with heart, and a fabric of ideas in one’s soul. The writer or urban artist has in his hand the possibility to express the humanity that the own human hostility shrinks while nature demands it to explore the responsibility and consciousness that comes with the project of building a common freedom.

Fernando Figueroa Saavedra, PhD in History of Art

SPANISH (original): Si algo singularizó e hizo grande al Graffiti, si algo explica claramente el tránsito del Writing al Aerosol Art, eso fue la atención prestada por los writers al plano gráfico y estético. Se hizo con tanta pasión que acabó convirtiéndose en un factor fundamental de realización individual, aglutinador comunitario y distintivo particular de una subcultura –luego movimiento internacional–, que expresaba ante todo libertad e interculturalidad. Por esa razón, resulta complejo entender la eclosión del Urban Art del siglo XXI sin atender a la génesis y definición del Writing-Graffiti en el siglo XX. Ambos procesos son hijos de un mismo germen, que les condujo a compartir una misma senda sobre el asfalto, siendo el Graffiti con su vitalidad, autonom��a y fortuna popular la verdadera vanguardia del arte callejero de ese siglo.

Las Style Wars, en el Nueva York de finales de los 70 y primeros 80, no fueron más que la declaración pública de que la creatividad artística era uno de los pilares fundamentales del Graffiti, caracterizándolo como un arte de frontera, autónomo frente al ecosistema artístico y paralelo a ese Public Art encargado, ordenado o dirigido por la administración pública o al omnipresente lenguaje publicitario. La fruición por el diseño y el estilo fue el pistoletazo de salida para un movimiento estético y una aventura vivencial sin precedentes, en el que la creatividad era a la vez mérito, ingenio, emoción, afecto y convivencia.

El Graffiti no sólo recubría los vagones o los muros, sino que penetraba en la cultura de masas y en las galerías de la alta cultura, estableciendo un perpetuo intercambio de materiales con dichas esferas. También había logrado conectar con su realidad social y cultural, cuajando su estética como un signo de los nuevos tiempos surgidos tras la Crisis de 1973 y entregándose en cuerpo y alma a la efervescencia juvenil de los años 80. Así, su mirada infantil había crecido y florecido, absorbiendo en su espíritu el hedonismo hippie, la vitalidad del rock o la rebeldía punk de los 70, sin dejar de lado en su encarnación todo ese conjunto de nutrientes ofrecidos a través del cómic, la TV, el cine, las carátulas de discos, el diseño gráfico, la publicidad, los letreros comerciales, el culto a la fama expresado en luces de neón y fogonazos de pantalla. Luego la riada Hip Hop, arrastraría al Graffiti con sus aires renovadores y rítmicos, bajo el consolidado imperio mundial de la sociedad de consumo y la conversión de una contracultura combativa en subcultura de resistencia.

En ese contexto, el pandillero se convertía en un peculiar superhéroe de barrio, cuyo desarrollo psicoevolutivo le llevaba a tomar conciencia de una realidad adulta de la que sabía que no podía evitar formar parte. Los memorials y otros murales cívicos, salidos de manos de algunos writers, se convirtieron en el reflejo de la involucración con sus vecindarios, con la sociedad civil, con la gente y su destino, siempre desde su mirada personal y a su manera.Paralelamente, mientras a uno y otro lado del Atlántico el graffiti de firma y pieza cogía cuerpo y arraigo, otras experiencias artístico-callejeras se habían estado desarrollando desde los años 60 en adelante al margen de la cultura oficial, desde el marco de la cultura popular, el mundo del arte o el activismo cultural.

El Postmodernism había nacido y aspiraba a quedarse, desperdigado por cada recoveco de la sociedad occidental, acogiendo todo tipo de fenómenos creativos. Desde los provos o los hippies hasta el Punk, pasando por la Internationale Situationniste, el muralismo social y político de los 70, el Neo-Expressionism o la Figuration Libre, o esa pléyade de serigrafitistas franceses, desde todos ellos se exponía el vivo interés por expresarse sin tapujos, con creatividad y una mezcla de fe y cachondeo, públicamente, en sociedad, y sacar el arte a las calles para fundirlo con la vida, sin más frontera que los límites de la imaginación. Era ya hora de aniquilar el arte como mercancía, subrayar su carácter comunitario y no elitista, democratizar su acceso popular y su práctica común en un espacio público que debía ser un espacio reivindicado y tomado, abierto y compartido, en suma, un espacio vivido y disfrutado por una ciudadanía autónoma.Sin duda, lo que reunía a writers y a otros graffiteros o artistas públicos o urbanos era un aire de época que se resumía en la apertura de miras y la libertad de acción.

Se trataba de ampliar los horizontes mentales de la sociedad, su conciencia de lo posible y lo positivo, su visión de un futuro y un marco de interrelaciones diferentes, forjado en la superación, la concordia y la pluralidad frente a la hostilidad de una realidad frustrante, pero que todavía no había mostrado en toda su crudeza su faceta castradora. No obstante, pese a las presiones y persecuciones asentadas en los años 90 a nivel mundial, jamás se pensó abandonar el shock visual a cielo abierto o bajo el subsuelo como garante de un contacto directo y sorpresivo con el espectador. Era su interpretación de una experiencia estético-vital al margen de los mass media, pero que reproducía, simulaba o exageraba su dinámica e imperativa vigencia.

Eran hijos de una era tecnológica con mentalidad artesana.Así fue que el mundo del Graffiti, tras su concreción tal y como lo conocemos hoy en día en los 80, pasó de encumbrarse como Aerosol Art a padecer una vorágine criminalizadora espectacular desde las instancias públicas, una vez cuajó la vietnamización del fenómeno, tal y como denunció Norman Mailer en su The Faith of Graffiti (1974) . Esta ilegalización sistemática y beligerante hasta la desproporción acabó consagrando la ilegalidad como un rasgo identitario del Hip Hop Graffiti de los 90 hasta hoy, justo en el momento que se sumía en una crisis y se replegaba de nuevo hacia la marginalidad cultural de los barrios y la periferia. No se tardó en reaccionar en este clima de castración social, gracias al brío de las nuevas generaciones que tomaban el relevo de las old schools locales y a que el Hip Hop Graffiti se expandía airoso hacia Europa del Este y Latinoamérica, demostrando su fortaleza. De este modo se afrontó inicialmente ese renacimiento, acentuándose el actuar vandálico, pero también su entidad artística. No obstante, ambos aspectos se planteaban y asumían, a menudo, como una disyuntiva.En este punto, dentro del Hip Hop Graffiti se produjo una reflexión sobre su entidad e identidad. Era hora de mirar hacia atrás, hacer memoria, no flojear, coger aliento y seguir para delante por un túnel sin luz, y eso contrajo, para algunos, la oportunidad de decidir dejar a un lado el lastre poderoso de una tradición.

Algunos veteranos activos y nuevos writers se deslindaban de la ortodoxia más old school para dar alas a su pulsión experimental y hacer crecer el Graffiti, con más ilusión que temor, con ímpetu adulto y fe de niño.Se había derrumbado la impresión de que todas las etapas anteriores habían sucedido para llegar a un modelo inmutable y único, que se tenía la obligación de reproducirse con precisión y reverencia, o de que el presente no era más que una devaluación de un pasado dorado que no volvería jamás. Ciertamente, la aureola del Graffiti no se limitaba a la imagen idílica del Subway Art de los 80, retratado por Craig Castleman o Henry Chalfant, es más, nadie podía imaginar la dimensión que alcanzaría en el siglo XXI. El Graffiti no murió en 1989, sólo se acomodó en sus raíces para ver transitar por encima de sus colores el oscuro invierno con su blanco manto de escarcha.

Desde mediados de los 90, el Hip Hop Graffiti volvía a fortalecerse, gracias, sobre todo, a que tomaba plena conciencia como movimiento transgeneracional, y a la consolidación de una red mundial de intercambio humano y de información interna sin parangón entre los movimientos artísticos que se habían sucedido hasta la fecha, sólo comparable con algunas propuestas del mundo musical, como el jazz o el rock. Surgían fanzines, comercios especializados, las primeras webs destinadas a visualizarse y estrechar lazos, los encuentros nacionales e internacionales o la concreción de una industria propia. La revolución del Graffiti dentro del Graffiti tuvo como consecuencia conocer otras realidades callejeras, abrir la mente, crear nuevos estilos, nuevas técnicas y soportes, nuevas tácticas para perdurar, el desarrollo de lo icónico, de lo dinámico, del realismo, el expresionismo, lo grotesco o lo informal, la exploración de las texturas, del relieve, de lo volumétrico, la acentuación de lo conceptual y lo performativo, el desarrollo del aspecto metalingüístico y el estudio de las relaciones con otros medios de expresión y comunicación, y en definitiva, nuevas estrategias para mantener el getting-up y el espíritu creativo del Graffiti vivos y frescos.

El Graffiti había madurado, en cuerpo y alma, y afrontaba una metamorfosis que daría lugar a algo que parecía otra cosa: el Postgraffiti, encabezado por la eclosión del iconismo, el Stencil Art, las pegatinas, los carteles o las intervenciones urbanas. No eran cosas nuevas, pero su vigor y profusión sí lo eran. Se trataba de ampliar sus límites, tensarlos al máximo, manteniendo también la posibilidad de adentrarse en el ecosistema artístico, ahora con más integridad, tras las infelices experiencias de los 80 y primeros 90. De este modo, writers y artistas convergían desde distintos orígenes y diferentes metas en el Urban Art del s. XXI, contribuyendo desde su bagaje y aspiraciones a concretar propuestas innovadoras en ese difícil equilibrio y respeto con los poderes públicos. El trasvase del Graffiti al Urban Art no suponía necesariamente para sus protagonistas una ruptura con un modo de ver y hacer las cosas, sino acaso una expansión conceptual, una ampliación de la conciencia, del discurso y de la capacidad de acción, fiel al concepto del ‘no limits to fame’, que se reconvertía ahora en un lema de libertad y heterodoxia dentro del mundo del Graffiti. El Graffiti nacía y latía en la calle, pero podía reverberar en otros ámbitos con la misma pasión.

En todo caso, el Graffiti se mantenía y mantiene como un movimiento sólido, cohesionado, rico e internacional, que ha demostrado una gran capacidad de integración y renovación. Una comunidad humana sin igual en el mundo del arte contemporáneo y pretérito que crece día a día y ayuda a construir otra realidad. A las puertas del siglo XXI, se adaptó a una nueva realidad urbana, diferente a la urbe de los años 70. En ella ha establecido un nuevo proyecto poético, diversificando los objetivos físicos, estáticos, móviles o portátiles, susceptibles de convertirse en soportes o las maneras de intervenir en ellos, llegando a concebir piezas híbridas que integran en su proceso tanto la acción callejera como la faceta expositiva. Los writers no sólo poseen, sino que dialogan con la arquitectura cara a cara, con el mobiliario urbano, el entorno físico y humano, los otros códigos comunicativos que comparten escenario con ellos, y, por su puesto, acogen, llegado el caso, enfoques sociales o políticos. Era un imperativo que crecía con el avance del siglo XXI y que no les puede ser ajeno como fauna urbana, dada su vocación pública.

Conscientes de las convenciones sociales y políticas o la deriva y agonía mundial, podemos hacernos una idea de que la opinión, la crítica, la demanda o la esperanza expresadas de forma poética o grotesca sobre los muros se convierten, de nuevo, en actos revolucionarios. Ya sea desde el plano personal o al abrigo de iniciativas públicas, particulares o vecinales, los writers que participan de ellos se vertebran dentro de la movilización social y la vida cultural, social y política. Sin embargo, todo es susceptible de instrumentalizarse política y comercialmente, incluso la rebeldía, como sucede con el empleo de artistas urbanos en procesos como la gentrificación o campañas de imagen institucional, pero el Graffti, por su especial filosofía, a nivel local parece congeniar muy bien con la dignificación y el orgullo de barrio, o el trabajo a pie de calle, como también algunos artistas urbanos, poco propensos a establecerse, aunque sea puntualmente, dentro del más convencional rol del artista público.

Es evidente que el Urban Art y el Graffiti ejemplifican ese gran potencial humano resumido en lemas como ‘do it yourself’ o ‘don’t stop’. El Street Art se asemeja a un poliedro de cien caras, capaz de soltarle con osadía un contundente ‘just do it’ a la sociedad y al mundo del arte, reapropiándose y reinterpretando hasta la parodia el American dream, para convencernos de que la voluntad supera toda adversidad, conflicto o miedo mientras nos tengamos a nosotros mismos. Pero no sólo eso, sino que en su sentir comunitario y origen popular late el nervio que hace a algunas personas proclives a entender la vida como una aventura colectiva y embarcarse en redefinir la sociedad sin más armas que un spray cargado de corazón y una fábrica de ideas en su alma. El writer o artista urbano tiene en su mano ayudar a expresar la humanidad que la propia hostilidad humana se encarga de encoger, mientras el mandato de la Naturaleza le impulsa a explorar la responsabilidad y consciencia de lo que significa construir la libertad común.

Fernando Figueroa Saavedra, Doctor en Historia del Arte

#graffiti#amsterdam graffiti#madrid graffiti#dr rat#dutch graffiti#history of graffiti#history of street art#street art#amsterdam#amsterdam street art#delta#boris telegen#suso33#misstic

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

For nearly two decades, Benoit Sokal has been a peerless impresario of point-and-click adventure games, most famously for the longrunning Syberia series which is now, at long last, releasing its much-anticipated third installment. But, particularly for Francophone audiences, Sokal was known long before his game design days as a colorful cartoonist from a golden age of comic art, flowing from the pens of many French and Belgian artists--particularly for his satirical Inspector Canardo, which follows the many adventures of a sauced duck detective in an anthropomorphized send up of noir detective drama.

For Sokal, the transition into game design was a natural extension of his skills and talents as a comic artist, and it also put him in a unique position as the creative lead for his games.

Sokal is a fascinating figure in game design because his vision is one he was actually able to paint with unparalleled skill. You were looking at his clear, unfiltered vision when you played his games. He drew the concepts and shaped the game’s visual language without mediation. To play is to get a sense of the inside of Sokal’s head in a way few videogame auteurs are capable of allowing.

I spoke to him recently about his transition into game development, as well as a few odds and ends about the development of Syberia 3. He also hints at a fourth installment for the series where Kate Walker’s adventures come to include romance.

I was quite naturally going back and forth from one to the other following the development of technology which allowed me first to colorize my comic strips with the help of a computer and to rather laboriously create small drawings with a mouse. Soon, I was interested in 3D computer generated images. By watching movies like Jurassic Park or Titanic, I had a kind of love at first sight for this technology that made it possible to render "hyper-realistically" things directly coming from the imagination of its creator or things that had totally disappeared.

I offered to my comic book publisher to produce, with these new types of images, a short story: what was called at the time "an interactive CD-ROM." I got caught up, the beginning of my ambition grew further and with a very small team, we worked during four years to develop “L'Amerzone.” For me, it was only the natural evolution of my trade: that of storytelling but only the tools changed.

I created Canardo at a very young age, I was 23. At the time, I was reading a lot of detective novels. Canardo was a parody of this genre; I probably had some significant teenage concerns and a dark humor to go with it. But I was afraid to find myself prisoner of this character’s success and not be able to address other themes and other kinds of stories. I always had the concern to diversify myself. Kate Walker was imagined more than twenty years later after that time. I had just simply changed and evolved. I guess I was looking at life differently!

I never imagined playing video games as a medium of expression in its own right. I consider myself as a video game author as one could be novelist or film director or cartoonist.

If, of course, the writing is very different, it nevertheless remains that I continue in video game to do what I have always done: create imaginary worlds; set a scene with great care and tell visual stories.

Yet, between the two genres, there are nonetheless immutable dramaturgical rules: how do you take the reader or player by the hand and guide him into the universe that is offered to him ... How do you create empathy between him and the characters we imagine.

And above all, to intrigue, confuse, and make him laugh or to cry: in short to create emotion.

But all that only works if you stay true to yourself. Only if one is going to seek his inspiring raw material deep inside, in what one has most secret and more intimate, hoping that in spite of all it interests the greatest number.

All stories are love stories. So I do not imagine that the adventures of Kate Walker could never benefit from a romantic engine as powerful as love and sexuality. I am currently creating for Kate Walker a love story that will take place in Syberia 4. What will be her ups and downs? The directions she will be taking? it's probably a bit early to say. But Kate Walker is an intelligent and free woman: her motto is “Adventure!”, which is included in her love choices... I can only imagine that these will never be final or stopped.

I have been very interested in the cultures and religions of nomadic Arctic peoples such as the Nenets of Siberia and the Tsaatans of Mongolia. I read a lot about their trances and paths to get there, and I met with shamanism specialists like Corinne Sombrun. The beliefs of these native peoples have hardly changed until the last few decades. They are fascinating because they use notions lost to the modern world: the permeability of the boundaries between the world of the living and the spirits and the fluidity of time passing ... Years, centuries do not exist for our ancestors, those who drew dancing animals on the walls of the caves.

*Editorial Note: This interview was translated from the original French by Daniel Sarrazin.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

0 notes