#the great white silence

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#polls#movies#the great white silence#great white silence#20s movies#herbert g. ponting#have you seen this movie poll

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

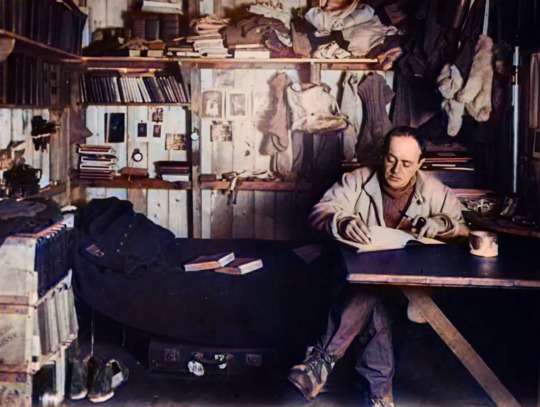

The Great White Silence (1924, dir. Herbert G. Ponting, British)

#the great white silence#robert falcon scott#polar exploration#my screencaps#documentary film#1920s films#unlike South 1919 I read accounts of the expedition before watching this#(specifically cherry-garrard’s Worst Journey in the World)#and the film did not capture the narrative’s feeling for me#obviously you can’t compress 600 pages into a single film#but the goofy 20s intertitles in the first half of this felt so morbid knowing what would happen to scott#polar

481 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching the great white silence (1924) giggling and kicking my legs like a schoolgirl

#blorbo from my silent film#polar exploration#polar history#antarctica#terra nova expedition#herbert ponting#the great white silence

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“But when they found that I was not such a ruffian as I looked, I could even stroke them as they sat on their nests.”

#classicfilmedit#filmedit#classicfilmsource#classicfilmblr#the great white silence#herbert ponting#original#*gifs

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great White Silence Herbert G. Ponting UK, 1922 ★★★★★ I'm sorry, what was the cat's name? I didn't get that part.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great White Silence (1924)-- A Review

Every artistic work is also a document of the time in which it was produced and the people who produced it. The Great White Silence, comprising footage shot during the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition (1910-1913) was released a little over 10 years after its tragedy unfolded. It was also directed by Herbert Ponting, himself a member of the expedition-- their designated "camera artist". The fact that this features images taken during the expedition before the episode that came to define it in public imagination makes it particularly intriguing. And the fact that all of this footage was both taken and then later organized into a documentary by a man who was intimately connected with the events lends it particular poignancy.

The Great White Silence is a flawed film. Sure, it is laden with striking imagery from very early on-- the bergs and ice grottos are a thing to behold, and the images of the Terra Nova forcing her way through the ice are downright sensual. The restoration was quite lovely-- the tinting and toning was beautifully done, and it brings some desperately needed color into overwhelmingly white landscapes. However, the film is also burdened with excessive titles, many of which are explaining things which we're already seeing on the screen. I wonder if they were put in to pad out the runtime. There are also extended sequences showing off the fauna of Antartica-- seals and penguins and gulls and whales all make appearances. I found it interesting how the animals were anthropomorphized by the humans that came into contact with them-- we get titles like "Now, watch baby learning to walk, when Mama says 'come along!'" for a baby seal and its mother. But while the footage of the animals is certainly an important historical document, their length drags down the film.

Meanwhile, I found the sequences showing the men of the expedition quite intriguing, and some even touching. This movie has been on my watchlist for a long time, but I'm glad I only watched it now-- although I'm quite early into my "polar history nerd" era, I think that having some idea of these men as individuals before watching this made for a much more emotionally stimulating experience. Had I watched this before, I would have seen most of them as mere faces in the crowd. But now I see Cherry, and Atch, and Birdie, and Titus. I don't see just figures, but people. Individuals who either died or were left grieving their fallen friends long after their return to "civilization".

Now, speaking of "civilization"-- I said in the opening paragraph that every artistic work is the product of the time, place and people who made it. Often we see people calling things "a product of its time" as a way to acknowledge in passing racism, sexism and classism and then quickly move on with it. I myself don't like this approach; I think it is a rather surface-level way of engaging with the past. It suggests that such prejudices were some sort of point which had to be reached and overcomed and that we, oh-so-advanced people of the 21st Century, have moved past such things. It also conveniently forgets that even during the "before times" there were marginalized people-- non-white folks, queer people, women-- who struggled against that oppressive order (as people struggle now). It does not engage with the larger context which fuels racism as an ideology, which when we talk about this film is particularly important.

Imperialism didn't have to happen; it was a choice made by the governments of the imperial bases in order to exploit the people and resources of its colonies, and it was ideologically buoyed by racism which positioned white people as the moral and intellectual superiors of non-white people. From what I've read (which is admittedly not so much), quite a few men of the Terra Nova expedition believed in the colonial project in broad terms, and indeed participated in it (many of them were, of course, serving in the military which was a key instrument to ensure British hegemony and therefore exploitation in its colonies). I don't say this as a way to dismiss their humanity; I have empathy for them as human beings whose lives ended in tragedy, but it is still important to engage meaningfully with this particular aspect of their existence. I don't think you can fully understand The Great White Silence without understanding British imperialism and where it stood both during the time of the expedition and by the time the film was released.

(Their ship's cat name was the n-word. I couldn't fit this bit of information anywhere else in the review but it felt too important not to mention).

Twice there are references to "our Race"-- it being white britons, of course. Scott and the others in the Polar Party perished in March 1912, when the idea of there being some great honor in "dying for the glory of the nation" still gripped the imagination of the public. Hell, it's even in one of the titles: "[...] and happy in the knowledge that they died for the honour of their country". The horrors of World War One, of men torn from limb to limb, of machine guns and mustard gas, would eat away at the foundations of this ideology-- dying for King and Country seemed less like a gallant sacrifice and more like being cattle led into slaughter. In some way, the insistence displayed in The Great White Silence that Scott's death had meaning because it was "for the honour of their country" feels like a desperate throwback to pre-War times. It was a way of assuring the public that their deaths were not in vain, no, they had meaning because it was an important thing it was for honour it was for King and Country and therefore the deaths of millions of soldiers in the Great War also had meaning.

Of course, the way I view it, their deaths had meaning because their lives had meaning, as every single life has. As the tragedy is set into motion (by the departure of the parties from Cape Evans towards the pole), the film picks up the pace, and it manages to strike a chord in terms of emotional engagement which I felt had been missing until then. I love the way the polar journey was represented-- we see four little black dots moving through the massive white landscape, and one by one they turn back, leaving only the one dot charging through. And as each member of the Polar Party dies, we hold on a still image of them. We've seen each one of them so delightfully alive earlier-- hauling, tending to the dogs and the ponies, playing football. To live is to be in motion, to die is to be eternally still. It is quite poignant. It's also a way of turning them from mere figures into actual individuals, of giving their deaths more emotional power. Considering most of the people watching probably weren't polar exploration nerds who already saw them as such because of their reading and research, I found it a very effective way to impact their humanity to the general public.

Overall, I think I found this a mixed bag. Although it does feature many incredible images and is fascinating to analyse from a socio-historical point of view, the excess of intertitles and somewhat extraneous sequences hold it back from being unequivocally great. But it is certainly very interesting, and as someone interested in polar exploration history more specifically, the opportunity of seeing these people I've read so much about in motion as opposed to having only photos and writings is invaluable. It truly brings them to life.

#terra nova expedition#the great white silence#polar exploration#mine#(spent idk maybe 1h30min writing this and haven't revised it so sorry for any errors)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mmmh. WHY would they name the cat that

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great White Silence (Herbert G. Ponting, 1922)

Cast: Robert Falcon Scott, Herbert G. Ponting, Henry R. Bowers, Edgar Evans, Lawrence E.G. Oates, Edward Adrian Wilson.

Back in the 1980s, Ted Turner provoked an outcry with his proposal to colorize the black-and-white films in his library. Filmmakers, historians, and critics protested, and with good reason: I remember watching Turner's colorized Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) and being startled by the paisley print on a blouse worn by Ingrid Bergman; I had never noticed it before the added colors made it stand out, which was certainly not the intention of the director, cinematographer Arthur Edeson, or perhaps even the costume designer, Orry-Kelly. Eventually, legislation put restrictions on such manipulation of old movies. But colorization was not a new thing: From the very beginning, filmmakers tried to add color to movies, usually by tinting the film stock a solid color: blue for night scenes; reds, oranges, and yellows for hot settings like Death Valley in Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1924); even pink for love scenes. Most silent movies after 1920 were colored in this way. But there were also attempts at more realistic coloring: For some of his short films, like A Trip to the Moon (1920), George Méliès used a technique devised by Elisabeth Thuillier, a kind of factory assembly-line of colorists who painstakingly added colors to the actors, costumes, and sets in each frame of the film. The technique proved too cumbersome and expensive as movies reached feature length. But it's one of the hallmarks of Herbert G. Ponting's documentary about the fateful Antarctic expedition of Robert Falcon Scott in 1910-13, The Great White Silence. Even though the whiteness of ice and snow is Antarctica's dominant feature, Ponting decided to hand-tint the footage he had shot ten years earlier, and thereby accentuated the contrast between human and animal life and the deadly whiteness of the continent. Color provides the life in the life-and-death struggle to reach -- and return from -- the South Pole. The images Ponting captured as the photographer for the expedition, using photographic equipment that now seems primitive, are the essence of the movie, and they often seem as fresh as if they were shot yesterday. Ponting was not allowed to accompany Scott from the base camp to the pole, which is from our point of view fortunate, as we might not have the record he made of the expedition now. But he filmed Scott and his fellow explorers as they rehearsed for the journey, trekking through the snows, setting up tents, bedding down, so he was able to give us at least some sense of what the men endured. Too bad that The Great White Silence is accompanied by a narrative that seems antique in ways that Ponting's images aren't. There's a lot of rather jingoist rhetoric about how Scott's expedition is a tribute to the English spirit, a credit to what Ponting calls "the Race," by which he seems to mean Anglo-Saxons. (One of the crew members has a pet black cat with an unfortunately racist name.) Ponting seems unconcerned with the irony that the doughty Englishmen of Scott's team failed to reach the South Pole before their chief competitor in the race, the Norwegian Roald Amundsen. Ponting's images of the animal life of Antarctica, seals and gulls and penguins, are accompanied by coy, condescending, anthropomorphic commentary that sets the tone for nature documentaries that followed. Still, it's an astonishing and invaluable film that fully merited the careful reconstruction that makes it available to us a century later.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

And the whole documentary is free to watch here:

youtube

The Great White Silence, 1924, Herbert G. Ponting

#icebergs#antarctica#polar exploration#the great white silence#silent film#silent movies#silent cinema#herbert g. ponting#arctic and antarctic#photography#documentaries#Youtube

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

PEOPLE DIED HERBERT

#shout-out to the great white silence. fascinating historical document. deeply tonally inconsistent movie#polar exploration

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

i saw someone with a jeff dunham shirt at work the other day and it threw me into a fucking frenzy i hate that goddamn dead terrorist and his annoying fucking voice :/

#one of my first misophonia triggers <3 god bless#if i have to hear (even in my head) ‘silence i kill you’ ever again im going to. uh. be very upset. again#it was literally spelled ‘keel’ on the shirt too like i very rarely use the word cringe for other people who are just living life but goddam#that made me so fucking mad LMAO#not that it’s the lady’s fault for wearing a shirt and i would never say this to her face LOL but like. wow#being in public is great because you’ll never know what you will see!#some days it’s jeff dunham shirt. sometimes it’s christian/straight/white/male/meat eater/what else can i do to piss you off#and some days it’s The Gym Is My Psych Ward#what a collection#punktalk

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Glad I’m watching this alone because this shot came on screen and I literally pointed at it and said “oh my god a tabular iceberg”

my love of Antarctica has taken me places I would’ve never gone before (watching a silent film)

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

stupid that stress is like an autism x2 multiplier

#like what do you MEAN im mad the air conditioner is rustling my hair a little#what do you MEAN i can feel every seam on my clothes#what do you MEAN im having a hard time with food textures#what do you MEAN eye contact is more difficult than usual#white noise has been making me. ooooh so on EDGE lately.#but then total silence doesn't feel great either#AAAAAAHGH. i'll be okay! by the end of next sunday the worst of it will be over#uhhh but if i don't have a meltdown between now and then it'll be a miracle

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

White people feel threatened when you so much as give an point of view... I cannot believe I'm reading this shit

#.#great. one person's input isn't an invalidation or dismissal of another person's. other people are allowed to add to the conversation#sometimes......... sometimes the adding on isn't an attack or even necessarily a direct response to someone personally#sometimes isn't not even an opinion on the matter at all#but you must handle these white fragile egos so delicately i guess#also. when white people pull this it shuts other people up. not the other way around. no one is dogpiling or silencing them

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ive come to the conclusion i fucking love gore and blood and shit. god bless. its kind of a surprise cause i wouldn’t think i like that but seeing as im entirely obsessed with westerns and crime dramas it shouldn’t be that surprising to me

#guy that is on the blood and gore loving website: surely that’s not me#film#um just finished the great silence and that shit fucking ruled brother#(spoilers ahead yadda yadda) um the death of silenzio…… slayed!! the slow motion shot of him falling over..#the way he falls into a deep bow with his hands in a prayer…#the white of the snow and the black of his clothing smeared with the red of his blood like HELLO!!#absolutely enamoured by the constant shots of his hands cause like. well its sooo stigmata core. sorry. but well they put holes there! so!!#somehow even though i wrote allll this post im not an mcr fan. crazy how life works

3 notes

·

View notes