#the fourth for a collection inspired in childhood series (my little pony in my case)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Random moodboards that i made for school

#the first was for a wool loom#the second and third for a jacket inspired in greek mitology and culture#the fourth for a collection inspired in childhood series (my little pony in my case)#the fifth about victor von schwartz#Victor is my favourite fashion designer#then there's Dolce and Gabanna moodboard#Valentina Karnoubi moodboard#Ryan Lo moodboard#my prom dress moodboard#moodboards#fashion design

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

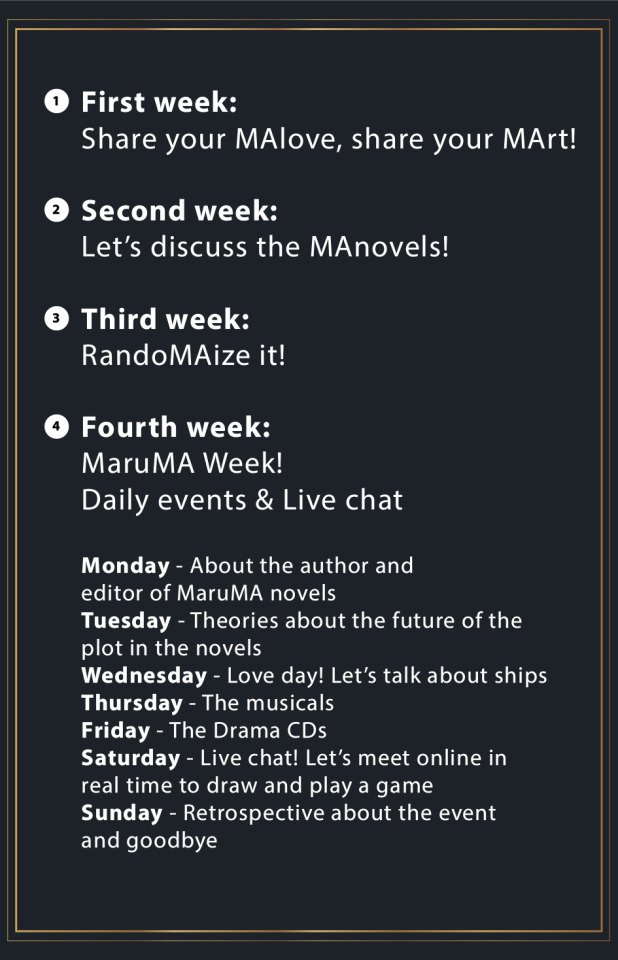

Hello Everyone!

A day like today 20 years ago the first novel of our beloved series was published in November 2000. This is an incredible anniversary and that’s why we’ll celebrate the whole month with events!

I hope you can join this special occasion and contribute a little bit by sharing your posts and art here in tumblr.

This is not the first event run by this blog, if you want to see what we did in previous years you can visit my tags MA Event, MA Event 2017 and MA Event 2018.

The dynamic of the events is to have some deliver themes and inspiration divided in different sections. This event will run weekly, except for the last week of the month when we’ll have daily content shared to inspire you even more.

Please save the date around the last weekend of November for our Live Chat! I’ll post more information about the exact date and time along the next weekly posts.

Update: Live Chat Sunday 29 at 1am Buenos Aires timezone GTM-3 You can check online comparing with your time zone here. We’ll meet and chat, share opinions, and play some games or draw together!

20th Anniversary MA Event - First Week Activity Share your MAlove, share your MArt! From November 1 to November 8

This week we’ll draw fanarts, write fanfics or make any other kind of media to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the series. We have list of 365 prompts in case you need a little bit of extra inspiration, please check under the cut and try to mix anything you pick with a festive mood to make it really special ;D

Remember to tag your posts with #MAnniversary 2020 and #MA Event

Links to the weekly event’s posts:

First Week (in this post) Second Week Third Week Fourth Week | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday

Prompts:

01. Introduction

02. Love

03. Light

04. Dark

05. Seeking Solace

06. Break Away

07. Heaven

08. Innocence

09. Drive

10. Breathe Again

11. Memory

12. Insanity

13. Misfortune

14. Smile

15. Silence

16. Questioning

17. Blood

18. Rainbow

19. Gray

20. Fortitude

21. Vacation

22. Mother Nature

23. Cat

24. No Time

25. Trouble Lurking

26. Tears

27. Foreign

28. Sorrow

29. Happiness

30. Under the Rain

31. Flowers

32. Night

33. Expectations

34. Stars

35. Hold my Hand

36. Precious Treasure

37. Eyes

38. Abandoned

39. Dreams

40. Rated

41. Teamwork

42. Standing Still

43. Dying

44. Two Roads

45. Illusion

46. Family

47. Creation

48. Childhood

49. Stripes

50. Breaking the Rules

51. Fanart

52. Deep in Thought

53. Keeping a Secret

54. Tower

55. Waiting

56. Danger Ahead

57. Sacrifice

58. Kick in the Head

59. No Way Out

60. Rejection

61. Fairy Tale

62. Magic

63. Do Not Disturb

64. Multitasking

65. Horror

66. Traps

67. Playing the Melody

68. Hero

69. Annoyance

70. 67%

71. Obsession

72. Mischief Managed

73. I Can’t

74. Are You Challenging Me?

75. Mirror

76. Broken Pieces

77. Test

78. Drink

79. Starvation

80. Words

81. Pen and Paper

82. Can You Hear Me?

83. Heal

84. Out Cold

85. Spiral

86. Seeing Red

87. Food

88. Pain

89. Through the Fire

90. Triangle

91. Drowning

92. All That I Have

93. Give Up

94. Last Hope

95. Advertisement

96. In the Storm

97. Safety First

98. Puzzle

99. Solitude

100. Relaxation

101. Hello World

102. Fear

103. Anger

104. Regret

105. Happiness

106. Love

107. Family

108. Friendship

109. Home

110. Childhood

111. Adulthood

112. Birth

113. Death

114. Me

115. You

116. Thoughts

117. Emotion

118. Sun

119. Rain

120. Thunder

121. Noon

122. Midnight

123. Twilight

124. Rooms

125. Window to the Soul

126. Games

127. Halo

128. Serenity

129. Firefly

130. Phone

131. Movie

132. Television

133. Plants

134. Freedom

135. Forgetfulness

136. Remembrance

137. Memorial

138. War

139. Fight

140. Loss

141. Winning

142. Losing

143. Nature

144. Hurricane

145. Storms are brewing

146. Lightning

147. Colors

148. Bravo

149. Punishment

150. Picture

151. Another Wolfs

153. The Life You Dream Of

154. Dreams

155. Tears

157. Smiling

158. Laughing

159. Crying

160. Looking in the Mirror

161. Steam

162. Candy

163. Cats

164. Dogs

165. Glasses

166. Orbit

167. Satellite

168. Stars

169. Jade

170. Emerald

171. Gems

172. Dreaming Out Loud

173. Insomnia

174. Rabbits

175. Snake

176. Borders

177. The Year

178. This Time

179. Last Time

180. Forever and a Day

181. Sometimes

182. Always

183. Power

184. Weakness

185. Green

186. Purple

187. Blue

188. Sight

189. Blindness

190. Hurtful

191. Stages of grief

192. Arguments

193. Country

194. Frog

195. Forest

196. River

197. Flying

198. Mountains

199. Snow

200. Goodbye

201. Heart of Glass

202. My Life

203. Me In a Nutshell

204. Forever Yours

205. True Colors

206. My best friend’s girl

207. Impossible Love

208. Forgiveness

209. Fibers of Our Lives

210. Challenging Dream

211. Living My Dream

212. Forgetting Myself

213. Saving Grace

214. Lonely

215. Unbalanced

216. See-saw

217. Math

218. Match Making

219. Beyond Good and Evil

220. Second Sight

221. Double Take

223. Upon Review

224. Losing You

225. Baseball

226. Shouting

227. Farmland

228. Heartland

229. Brick Wall

230. Glass Houses

231. Eyes

231. Ring

233. Circle

234. Square

235. Boxes

236. Moving

237. Well Being

238. Insanity

239. Repetition

240. Learning

241. Class

242. Flowers

243. Special

244. Snowflakes

245. The Man They Call Jayne

246. Malicious

247. Pretty on the Outside

248. The Outside

249. Thankful

250. Neglect

251. Remorse

252. Embracement

253. Reflecting on My Life

254. Space

255. Constellation

256. Collection

257. Magic

258. Thrill

259. Attack

260. 20 Seconds to Mars

261. Unable

262. Foolish

263. Science

264. Sign of Life

265. Motto

266. Me

267. Balloon

268. Self Esteem

269. Narcissism

270. Ideology

271. Pageantry

272. Keeping Up With the Jones’s

273. Crack in Your Armor

274. Spilling Your Guts

275. Lean on Me

276. Crippling Emotion

277. Biggest Fear

278. Prejudices

279. Fresh

280. Corn

281. Sugar

282. Ice Cream

283. Accents

284. Speech

285. Writing

286. Doom

287. Shape

288. The Real You

289. My Name Is ____

290. Who are You on the Inside

291. Hidden Hatred

292. Hanging

293. Jacket

294. Jail

295. Stepping Up to the Plate

296. Star Player

297. My Hero

298. Castle

299. Losing Yourself

300. Finding Hope

301. Pirates

302. Fallen Angel

303. Drowning Lessons

304. Ghosts in the snow

305. Rawr.

306. Pidgeons… Birdy

307. Broken Hearts Parade

308. Paranoid

309. Vampires

310. Betrayal

311. Emmi&Rumura

312. The three friends

313. Horror

314. Mirror

315. Candlelight

316. Spider moneky

317. Devil

318. Flowers

319. Teddy Bear

320. Mist

321. Kingdom Hearts

322. Ferret

323. Vanilla

324. Thunder

325. Pinto Pony

326. M&Ms

327. Killer

328. Grass

329. Peace

330. Chibi

331. Mr. Klaw, polite Lion

332. Eternal

333. Star girl

334. Hats

335. Calvin & Hobbes

336. Misery (A cup full of something… unknown )

337. Hot chocolate

338. My Chemical Romance

339. Light in the darkness

340. Laughter

341. Nightmares

342. Necklace

343. Fire

344. Clorotaint and Treegirl

345. Swirls

346. Pokemon

347. Friends

348. Double Trouble

349. Do not cross

350. Unknowing

351. Chocolate

352. Time

353. A phone

354. Little kids on a playground

355. Darkness

356. A purple lady

357. Writer’s block

358. The dark corner in my room that I go to cry at (and a unicorn)

359. Sunglasses

360. The sun relaxing by an air conditioner

361. A girl fleeing from her nightmares

362. A girl staring at a blank canvas

363. A visual representation of poetry

364. Trolls

365. A hat

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Frozen 2 and Disney’s nostalgia problem

Elsa’s back. | Walt Disney Pictures

Disney used to always be looking forward. These days, it increasingly only looks back.

Nobody was more nostalgic than Marcel Proust.

The French novelist’s six-volume masterwork In Search of Lost Time is narrated by a man who’s remembering his youth, and it explores how strange and unreliable memory can be. Throughout the series, the notion of “involuntary” memory is a recurring theme, but it’s particularly important in the famous “madeleine” scene.

The scene comes early in the first volume, Swann’s Way, when the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea immediately plunges the narrator into a vivid childhood memory. It’s so well-known that it remains a cultural reference point even today, more than a century after Swann’s Way was published: To say that something is your “madeleine” is shorthand for any sensory experience that brings back a flood of childhood memories (even though mounting evidence suggests that Proust’s version may have just been soggy toast).

That sensory experiences can trigger powerful memories, particularly of youth and childhood, was not a particularly earth-shattering insight on Proust’s part — lots of people have had similar episodes. And while not all of his narrator’s recollections are fond, a lot of them seem presented through a haze of affection — the reliability of which, as the narrator us himself, is a little suspect. “Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were,” he writes.

Maurice Rougemont/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Marcel Proust famously wrote about madeleines as he explored the ways our memories are triggered.

Proust aptly describes the concept of nostalgia: a sentimental yearning for the past, which Merriam Webster defines, succinctly and evocatively, as “the state of being homesick.” And while we periodically recall certain moments as being worse than they actually were (I think of the 30 Rock episode in which Liz Lemon is shocked to discover that her memories of being bullied in high school are faulty, and she was the one doing the bullying), the past often takes on a rosy hue.

Time, distance, and the occasional dash of willful ignorance are effective modifiers. They’re why societies collectively hallucinate Golden Ages, and why so many people find the idea of making America “great again” appealing. It’s less about conserving the good of the past, and more about rejecting the present.

Nostalgia is not, as a mood, inherently bad. Sometimes, feeling a bit homesick is good. But when that feeling becomes our default posture, our guiding light, it starts to become ... troubling? Inhibiting, maybe? Stifling? If the past was when things were good, why bother to build a new future? Better to just keep reinventing the past.

Which brings us to Disney, and to Frozen 2.

Disney used to be a company that looked forward. These days, it seems more interested in looking back.

Disney now controls the lion’s share of the movie industry. In 2019 so far, five of the six highest-grossing films worldwide have been Disney properties; the sixth (Spider-Man: Far From Home) was a joint endeavor between Sony and Disney-owned Marvel. The company’s reach is staggering: It owns, among scores other entities, Pixar, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars, and as of earlier this year, the film and TV assets formerly held by 21st Century Fox — in addition to its own extensive and much-beloved back catalog, lots of which is now available to stream via the just-launched Disney+ service.

Disney is in the entertainment business. But what it’s selling isn’t entertainment, exactly — that’s just the vehicle for its real product, and that product has shifted and morphed over time. At one time, a big part of what Disney was selling was a vision of a utopian future, as you know, if you’ve been to Tomorrowland or Epcot at Walt Disney World.

In his speech at the opening day of Disneyland in 1955, Walt Disney himself pointed to his vision of the park as a place where nostalgia and forward-looking inspiration could coexist: “Here age relives fond memories of the past, and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future.”

Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Walt Disney at the Disneyland grand opening in 1955.

But as we come to the end of this banner year for Disney, it’s clear that what the company wants to sell us, going forward, is a seemingly infinite heap of Proustian madeleines. Certainly the warm fuzzies have been one of Disney’s main exports for a long time, but some kind of tipping point was reached in 2019. Now, it seems evident that Disney sees provoking existential homesickness as its main job. Nostalgia is its real product.

Consider Toy Story 4, the fourth film in a series that debuted in November 1995. If you were 8 years old and saw Toy Story in theaters when it opened, you might have brought your own 8-year-old to see the new film earlier this year.

That’s a remarkable stretch of time, and the Toy Story series has stayed remarkably thematically coherent over that time. It’s a set of stories about the passage of time, about how nothing stays the same, about the fact that kids grow up and leave home — that’s why Toy Story 3 left parents bawling when Andy finally grew up and didn’t need his toys anymore. The toys, in a sense, are the parents’ stand-ins. And Toy Story 4, in which some of the toys opt to live a child-free life, feels an awful lot like a movie about being an empty nester, something that could render a parent munching popcorn with their third grader a bit verklempt, thinking about their own now-empty-nester parents who once took them to see Toy Story.

That’s the good kind of nostalgia. And the Toy Story series has successfully refreshed its basic premise over two decades — toys get lost, toys get found — in part through its willingness to surprise viewers, to crack jokes and be a little creepy and think outside the (toy) box with its narratives. So when we find ourselves feeling homesick, in a story about the passage of time, it works.

I think of this approach as generative nostalgia. It’s a way for Disney to use memory, to tap into the audience’s particular madeleines, to bolster the storytelling itself (and make an enormous wad of cash, too). Not every attempt lands, but when movie studios try to tap into nostalgia in order to generate fresh new stories with universal themes, to get creative with the familiar, it’s a good thing for art.

Pixar Animation Studios / Walt Disney Pictures

From Toy Story 4, we got Forky.

If Toy Story 4 was an example of Disney harnessing generative nostalgia, however, its so-called “live-action” remake of The Lion King was just the opposite. The film was never meant to be a standalone movie; its success was always fully dependent on the long-entrenched popularity of the 1994 animated film it recreates, in some cases shot for shot. It’s an entirely unnecessary movie — a way for Disney to test-drive high-end, lifelike CGI and get people to pay for it. And without the imaginative, sometimes visually wild artwork of the original, it falls very flat, with no new perspective on its source material.

Call it derivative nostalgia: For most audiences, The Lion King and Disney’s other live-action remakes (Aladdin was another huge hit this year) are interesting only insofar as they promise to deliver a (slightly) new spin on a beloved classic, without straying too far. We still get “Can You Feel the Love Tonight,” but it’s Donald Glover and Beyoncé. A copy of the original with some of the details tweaked. That’s the appeal.

And while derivative nostalgia has its place — we rewatch our favorite movies for a reason, because we like the feelings and memories they provoke — Disney seems intent on adopting it as a modus operandi, judging from the number of remakes the company has announced. It will depend on the built-in audience of people who loved Lady and the Tramp or 101 Dalmatians to pony up for a ticket or subscribe to Disney+ and ensure these projects’ success.

But I’m convinced the urge to use your giant piles of money to endlessly replicate the past can’t be good for a culture. Certainly, human culture is cumulative; we’re always building on what came before. For millennia, storytellers have leaned on the same material, like myths and archetypes, to find new ways to tell stories. But derivative nostalgia stymies the creative impulse, miring us in the same thing over and over again and training audiences to demand the predictable. Vanilla pudding tastes good, but there’s a lot more to food than vanilla pudding.

You can witness the battle for Disney’s soul happening inside Frozen 2

These generative and derivative modes of nostalgia seem to be warring inside inside Frozen 2, which is pleasing and enjoyable even if it’s clearly designed to function as an ATM for Disney, with Frozen’s previously established fanbase acting as the bank account behind the screen. It is, thank God, no Olaf’s Frozen Adventure.

The Frozen films are aimed primarily at little girls and boys, of course — Disney’s long-running core constituency for stories about princesses and talking animals (or snowmen). But, given that the first movie came out six years ago, Frozen 2 is also for older kids. And one of the most notable things about the movie is that it’s also for their parents.

Perhaps following Pixar’s lead, the more traditional Disney Animation studio has caught onto the fact that if you want grown-ups to be happy when they take kids to the movie theater, you’ve got to make something they’ll enjoy, too. So Frozen 2 leans (more noticeably than its predecessor) into jokes the adults will appreciate, and one in particular: While the kids at my screening howled at Olaf’s slapsticky misadventures, the adults were the ones laughing as Princess Anna’s hunky boyfriend Kristoff crooned his very ’80s-sounding power ballad “Lost in the Woods.”

During a recent interview, Josh Gad (who voices Olaf) joked that the song “speaks to all of us that grew up in the ’80s.” And he’s totally right. The voice of Kristoff, Jonathan Groff, says he was surprised when the song was handed to him: “I couldn’t believe that they were going to go there,” he said, calling it “truly shocking” and later saying it has the energy of Michael Bolton. The song is about how much Kristoff needs Anna in his life; in the film, he sings it during a fantasy sequence of finding her, backed by a chorus of singing reindeer. (The official Frozen 2 soundtrack includes a version of the song by Weezer, which kind of says everything.)

As Gad pointed out, it’s definitely a sight gag for the olds in the room — the younger Gen X and older millennial parents who’ve come to see Frozen 2 with their kids, and are now being rewarded with their own extended musical joke. What’s funny about it is that the musical-style “Into the Woods” parodies was already ridiculous by the time most gen-Xers and millennials became adults; what we’re reminded of now is the sheer goofiness that was so prevalent back then, when romantic ballads were sung by guys with bad hair surrounded by unironic kitsch.

Kids born in the 21st century won’t get the joke. But Frozen 2 isn’t exclusively for them; it’s for 20th-century kids, too. In fact, though its action is set just three years after the end of Frozen, it is, like Toy Story, about the passage of time, and what it’s like to grow older. Olaf sings a song about how things don’t make sense to him now, but they will someday; Anna and Olaf reflect on how they hope everything will stay the same, even though — spoiler alert — of course, they won’t.

Walt Disney Pictures

The gang’s all back together in Frozen 2.

So Frozen 2 provokes all kinds of nostalgia. For kids who’ve already spent years dressing up as Anna and Elsa and driving their parents to distraction with “Let It Go,” the new film is a return to the happy land of Arendelle, where they’ve had many adventures. For teenagers who saw the original Frozen when they were 8 or so, but are now in high school, it’s a reminder of how far they’ve come. And for adults, it tugs on decades-old heartstrings — not just the chuckling memory of’ 80s power ballads, which might be the madeleine that reminds some of dancing at prom, but also the Disney princess stories so many of us grew up watching.

Whereas the original Frozen is a bit of an odd film — its plot structure feels a little out-of-sync with Disney’s usual storytelling, and its “true love’s kiss” comes not from a prince but a sister — Frozen 2 is much more conventional. Frozen retained some of the eerie strangeness of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale it was (very) loosely based on; Frozen 2 goes back to the usual adventure-and-return structure that has made so many classic Disney movies a success. It’s familiar. It’s comfortable.

By my lights, Frozen 2 is still a plenty enjoyable film, even if it lacks its predecessor’s subversive spark. But for me, watching generative and derivative nostalgia spar within it prompted a different sense of the familiar: bleakness about the future of mouse-eared entertainment. Disney, whatever its faults, has often been a pioneer in storytelling; now it’s resting firmly on its laurels, too often electing to spin the wheel again rather than try to reinvent it.

Nostalgia has its place. Remembering the feeling of homesickness reminds us where we came from, that we come from somewhere. But too much yearning for the past without a concomitant attempt to live in the present and push toward the future is a dangerous trap for a culture to fall into, both because it risks becoming stagnant in its art and because it may begin to to worship the past as the only place worth living in. Too much yearning for the past makes us incurious about the world. And if, as Proust wrote, the past we remember is not necessarily the one that existed, remaining stubbornly beholden to it can render us altogether incapable of dealing with the present.

The bigger Disney gets, the more it controls what most Americans — and people around the world — will see at the movies and on their TV screens, and thus it bears enormous responsibility for seeing into the future. Looking backward too much, recycling old content and relying on old formulas endlessly, becomes a snake eating its own tail.

As the endless stream of reboots and remakes and sequels and revivals that currently dominates entertainment attests, nostalgia sells. But it is also the thing most easily packaged to sell. Recycling content is the low-hanging fruit. And when Disney leans into the least creative sort of recycled content, live-action remakes — something nobody’s really asking for — it’s signaling how little it’s interested in originality.

Even when those remakes take a risk — for instance, by casting black actress Halle Bailey as Ariel in The Little Mermaid — it’s worth noting how safe the “risk” really is. Being a creative leader who celebrates inclusivity means daring to build something new, and trusting the artists to draw audiences into a new story. It doesn’t mean casting new faces in old, well-trodden roles with guaranteed built-in audiences because you’re not sure audiences will turn up otherwise. It doesn’t mean defaulting to reviving your past.

Which, ironically, is something Walt Disney was determined to keep his company from doing. As quoted in the 2007 Disney animated film Meet the Robinsons, he pushed for just the opposite: “Around here, however, we don’t look backwards for very long. We keep moving forward, opening up new doors and doing new things, because we’re curious. And curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.”

Frozen 2 opens in theaters on November 21.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2OvMLXf

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Frozen 2 and Disney’s nostalgia problem

Elsa’s back. | Walt Disney Pictures

Disney used to always be looking forward. These days, it increasingly only looks back.

Nobody was more nostalgic than Marcel Proust.

The French novelist’s six-volume masterwork In Search of Lost Time is narrated by a man who’s remembering his youth, and it explores how strange and unreliable memory can be. Throughout the series, the notion of “involuntary” memory is a recurring theme, but it’s particularly important in the famous “madeleine” scene.

The scene comes early in the first volume, Swann’s Way, when the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea immediately plunges the narrator into a vivid childhood memory. It’s so well-known that it remains a cultural reference point even today, more than a century after Swann’s Way was published: To say that something is your “madeleine” is shorthand for any sensory experience that brings back a flood of childhood memories (even though mounting evidence suggests that Proust’s version may have just been soggy toast).

That sensory experiences can trigger powerful memories, particularly of youth and childhood, was not a particularly earth-shattering insight on Proust’s part — lots of people have had similar episodes. And while not all of his narrator’s recollections are fond, a lot of them seem presented through a haze of affection — the reliability of which, as the narrator us himself, is a little suspect. “Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were,” he writes.

Maurice Rougemont/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Marcel Proust famously wrote about madeleines as he explored the ways our memories are triggered.

Proust aptly describes the concept of nostalgia: a sentimental yearning for the past, which Merriam Webster defines, succinctly and evocatively, as “the state of being homesick.” And while we periodically recall certain moments as being worse than they actually were (I think of the 30 Rock episode in which Liz Lemon is shocked to discover that her memories of being bullied in high school are faulty, and she was the one doing the bullying), the past often takes on a rosy hue.

Time, distance, and the occasional dash of willful ignorance are effective modifiers. They’re why societies collectively hallucinate Golden Ages, and why so many people find the idea of making America “great again” appealing. It’s less about conserving the good of the past, and more about rejecting the present.

Nostalgia is not, as a mood, inherently bad. Sometimes, feeling a bit homesick is good. But when that feeling becomes our default posture, our guiding light, it starts to become ... troubling? Inhibiting, maybe? Stifling? If the past was when things were good, why bother to build a new future? Better to just keep reinventing the past.

Which brings us to Disney, and to Frozen 2.

Disney used to be a company that looked forward. These days, it seems more interested in looking back.

Disney now controls the lion’s share of the movie industry. In 2019 so far, five of the six highest-grossing films worldwide have been Disney properties; the sixth (Spider-Man: Far From Home) was a joint endeavor between Sony and Disney-owned Marvel. The company’s reach is staggering: It owns, among scores other entities, Pixar, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars, and as of earlier this year, the film and TV assets formerly held by 21st Century Fox — in addition to its own extensive and much-beloved back catalog, lots of which is now available to stream via the just-launched Disney+ service.

Disney is in the entertainment business. But what it’s selling isn’t entertainment, exactly — that’s just the vehicle for its real product, and that product has shifted and morphed over time. At one time, a big part of what Disney was selling was a vision of a utopian future, as you know, if you’ve been to Tomorrowland or Epcot at Walt Disney World.

In his speech at the opening day of Disneyland in 1955, Walt Disney himself pointed to his vision of the park as a place where nostalgia and forward-looking inspiration could coexist: “Here age relives fond memories of the past, and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future.”

Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Walt Disney at the Disneyland grand opening in 1955.

But as we come to the end of this banner year for Disney, it’s clear that what the company wants to sell us, going forward, is a seemingly infinite heap of Proustian madeleines. Certainly the warm fuzzies have been one of Disney’s main exports for a long time, but some kind of tipping point was reached in 2019. Now, it seems evident that Disney sees provoking existential homesickness as its main job. Nostalgia is its real product.

Consider Toy Story 4, the fourth film in a series that debuted in November 1995. If you were 8 years old and saw Toy Story in theaters when it opened, you might have brought your own 8-year-old to see the new film earlier this year.

That’s a remarkable stretch of time, and the Toy Story series has stayed remarkably thematically coherent over that time. It’s a set of stories about the passage of time, about how nothing stays the same, about the fact that kids grow up and leave home — that’s why Toy Story 3 left parents bawling when Andy finally grew up and didn’t need his toys anymore. The toys, in a sense, are the parents’ stand-ins. And Toy Story 4, in which some of the toys opt to live a child-free life, feels an awful lot like a movie about being an empty nester, something that could render a parent munching popcorn with their third grader a bit verklempt, thinking about their own now-empty-nester parents who once took them to see Toy Story.

That’s the good kind of nostalgia. And the Toy Story series has successfully refreshed its basic premise over two decades — toys get lost, toys get found — in part through its willingness to surprise viewers, to crack jokes and be a little creepy and think outside the (toy) box with its narratives. So when we find ourselves feeling homesick, in a story about the passage of time, it works.

I think of this approach as generative nostalgia. It’s a way for Disney to use memory, to tap into the audience’s particular madeleines, to bolster the storytelling itself (and make an enormous wad of cash, too). Not every attempt lands, but when movie studios try to tap into nostalgia in order to generate fresh new stories with universal themes, to get creative with the familiar, it’s a good thing for art.

Pixar Animation Studios / Walt Disney Pictures

From Toy Story 4, we got Forky.

If Toy Story 4 was an example of Disney harnessing generative nostalgia, however, its so-called “live-action” remake of The Lion King was just the opposite. The film was never meant to be a standalone movie; its success was always fully dependent on the long-entrenched popularity of the 1994 animated film it recreates, in some cases shot for shot. It’s an entirely unnecessary movie — a way for Disney to test-drive high-end, lifelike CGI and get people to pay for it. And without the imaginative, sometimes visually wild artwork of the original, it falls very flat, with no new perspective on its source material.

Call it derivative nostalgia: For most audiences, The Lion King and Disney’s other live-action remakes (Aladdin was another huge hit this year) are interesting only insofar as they promise to deliver a (slightly) new spin on a beloved classic, without straying too far. We still get “Can You Feel the Love Tonight,” but it’s Donald Glover and Beyoncé. A copy of the original with some of the details tweaked. That’s the appeal.

And while derivative nostalgia has its place — we rewatch our favorite movies for a reason, because we like the feelings and memories they provoke — Disney seems intent on adopting it as a modus operandi, judging from the number of remakes the company has announced. It will depend on the built-in audience of people who loved Lady and the Tramp or 101 Dalmatians to pony up for a ticket or subscribe to Disney+ and ensure these projects’ success.

But I’m convinced the urge to use your giant piles of money to endlessly replicate the past can’t be good for a culture. Certainly, human culture is cumulative; we’re always building on what came before. For millennia, storytellers have leaned on the same material, like myths and archetypes, to find new ways to tell stories. But derivative nostalgia stymies the creative impulse, miring us in the same thing over and over again and training audiences to demand the predictable. Vanilla pudding tastes good, but there’s a lot more to food than vanilla pudding.

You can witness the battle for Disney’s soul happening inside Frozen 2

These generative and derivative modes of nostalgia seem to be warring inside inside Frozen 2, which is pleasing and enjoyable even if it’s clearly designed to function as an ATM for Disney, with Frozen’s previously established fanbase acting as the bank account behind the screen. It is, thank God, no Olaf’s Frozen Adventure.

The Frozen films are aimed primarily at little girls and boys, of course — Disney’s long-running core constituency for stories about princesses and talking animals (or snowmen). But, given that the first movie came out six years ago, Frozen 2 is also for older kids. And one of the most notable things about the movie is that it’s also for their parents.

Perhaps following Pixar’s lead, the more traditional Disney Animation studio has caught onto the fact that if you want grown-ups to be happy when they take kids to the movie theater, you’ve got to make something they’ll enjoy, too. So Frozen 2 leans (more noticeably than its predecessor) into jokes the adults will appreciate, and one in particular: While the kids at my screening howled at Olaf’s slapsticky misadventures, the adults were the ones laughing as Princess Anna’s hunky boyfriend Kristoff crooned his very ’80s-sounding power ballad “Lost in the Woods.”

During a recent interview, Josh Gad (who voices Olaf) joked that the song “speaks to all of us that grew up in the ’80s.” And he’s totally right. The voice of Kristoff, Jonathan Groff, says he was surprised when the song was handed to him: “I couldn’t believe that they were going to go there,” he said, calling it “truly shocking” and later saying it has the energy of Michael Bolton. The song is about how much Kristoff needs Anna in his life; in the film, he sings it during a fantasy sequence of finding her, backed by a chorus of singing reindeer. (The official Frozen 2 soundtrack includes a version of the song by Weezer, which kind of says everything.)

As Gad pointed out, it’s definitely a sight gag for the olds in the room — the younger Gen X and older millennial parents who’ve come to see Frozen 2 with their kids, and are now being rewarded with their own extended musical joke. What’s funny about it is that the musical-style “Into the Woods” parodies was already ridiculous by the time most gen-Xers and millennials became adults; what we’re reminded of now is the sheer goofiness that was so prevalent back then, when romantic ballads were sung by guys with bad hair surrounded by unironic kitsch.

Kids born in the 21st century won’t get the joke. But Frozen 2 isn’t exclusively for them; it’s for 20th-century kids, too. In fact, though its action is set just three years after the end of Frozen, it is, like Toy Story, about the passage of time, and what it’s like to grow older. Olaf sings a song about how things don’t make sense to him now, but they will someday; Anna and Olaf reflect on how they hope everything will stay the same, even though — spoiler alert — of course, they won’t.

Walt Disney Pictures

The gang’s all back together in Frozen 2.

So Frozen 2 provokes all kinds of nostalgia. For kids who’ve already spent years dressing up as Anna and Elsa and driving their parents to distraction with “Let It Go,” the new film is a return to the happy land of Arendelle, where they’ve had many adventures. For teenagers who saw the original Frozen when they were 8 or so, but are now in high school, it’s a reminder of how far they’ve come. And for adults, it tugs on decades-old heartstrings — not just the chuckling memory of’ 80s power ballads, which might be the madeleine that reminds some of dancing at prom, but also the Disney princess stories so many of us grew up watching.

Whereas the original Frozen is a bit of an odd film — its plot structure feels a little out-of-sync with Disney’s usual storytelling, and its “true love’s kiss” comes not from a prince but a sister — Frozen 2 is much more conventional. Frozen retained some of the eerie strangeness of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale it was (very) loosely based on; Frozen 2 goes back to the usual adventure-and-return structure that has made so many classic Disney movies a success. It’s familiar. It’s comfortable.

By my lights, Frozen 2 is still a plenty enjoyable film, even if it lacks its predecessor’s subversive spark. But for me, watching generative and derivative nostalgia spar within it prompted a different sense of the familiar: bleakness about the future of mouse-eared entertainment. Disney, whatever its faults, has often been a pioneer in storytelling; now it’s resting firmly on its laurels, too often electing to spin the wheel again rather than try to reinvent it.

Nostalgia has its place. Remembering the feeling of homesickness reminds us where we came from, that we come from somewhere. But too much yearning for the past without a concomitant attempt to live in the present and push toward the future is a dangerous trap for a culture to fall into, both because it risks becoming stagnant in its art and because it may begin to to worship the past as the only place worth living in. Too much yearning for the past makes us incurious about the world. And if, as Proust wrote, the past we remember is not necessarily the one that existed, remaining stubbornly beholden to it can render us altogether incapable of dealing with the present.

The bigger Disney gets, the more it controls what most Americans — and people around the world — will see at the movies and on their TV screens, and thus it bears enormous responsibility for seeing into the future. Looking backward too much, recycling old content and relying on old formulas endlessly, becomes a snake eating its own tail.

As the endless stream of reboots and remakes and sequels and revivals that currently dominates entertainment attests, nostalgia sells. But it is also the thing most easily packaged to sell. Recycling content is the low-hanging fruit. And when Disney leans into the least creative sort of recycled content, live-action remakes — something nobody’s really asking for — it’s signaling how little it’s interested in originality.

Even when those remakes take a risk — for instance, by casting black actress Halle Bailey as Ariel in The Little Mermaid — it’s worth noting how safe the “risk” really is. Being a creative leader who celebrates inclusivity means daring to build something new, and trusting the artists to draw audiences into a new story. It doesn’t mean casting new faces in old, well-trodden roles with guaranteed built-in audiences because you’re not sure audiences will turn up otherwise. It doesn’t mean defaulting to reviving your past.

Which, ironically, is something Walt Disney was determined to keep his company from doing. As quoted in the 2007 Disney animated film Meet the Robinsons, he pushed for just the opposite: “Around here, however, we don’t look backwards for very long. We keep moving forward, opening up new doors and doing new things, because we’re curious. And curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.”

Frozen 2 opens in theaters on November 21.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2OvMLXf

0 notes

Text

On Frozen 2 and Disney’s nostalgia problem

Elsa’s back. | Walt Disney Pictures

Disney used to always be looking forward. These days, it increasingly only looks back.

Nobody was more nostalgic than Marcel Proust.

The French novelist’s six-volume masterwork In Search of Lost Time is narrated by a man who’s remembering his youth, and it explores how strange and unreliable memory can be. Throughout the series, the notion of “involuntary” memory is a recurring theme, but it’s particularly important in the famous “madeleine” scene.

The scene comes early in the first volume, Swann’s Way, when the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea immediately plunges the narrator into a vivid childhood memory. It’s so well-known that it remains a cultural reference point even today, more than a century after Swann’s Way was published: To say that something is your “madeleine” is shorthand for any sensory experience that brings back a flood of childhood memories (even though mounting evidence suggests that Proust’s version may have just been soggy toast).

That sensory experiences can trigger powerful memories, particularly of youth and childhood, was not a particularly earth-shattering insight on Proust’s part — lots of people have had similar episodes. And while not all of his narrator’s recollections are fond, a lot of them seem presented through a haze of affection — the reliability of which, as the narrator us himself, is a little suspect. “Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were,” he writes.

Maurice Rougemont/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Marcel Proust famously wrote about madeleines as he explored the ways our memories are triggered.

Proust aptly describes the concept of nostalgia: a sentimental yearning for the past, which Merriam Webster defines, succinctly and evocatively, as “the state of being homesick.” And while we periodically recall certain moments as being worse than they actually were (I think of the 30 Rock episode in which Liz Lemon is shocked to discover that her memories of being bullied in high school are faulty, and she was the one doing the bullying), the past often takes on a rosy hue.

Time, distance, and the occasional dash of willful ignorance are effective modifiers. They’re why societies collectively hallucinate Golden Ages, and why so many people find the idea of making America “great again” appealing. It’s less about conserving the good of the past, and more about rejecting the present.

Nostalgia is not, as a mood, inherently bad. Sometimes, feeling a bit homesick is good. But when that feeling becomes our default posture, our guiding light, it starts to become ... troubling? Inhibiting, maybe? Stifling? If the past was when things were good, why bother to build a new future? Better to just keep reinventing the past.

Which brings us to Disney, and to Frozen 2.

Disney used to be a company that looked forward. These days, it seems more interested in looking back.

Disney now controls the lion’s share of the movie industry. In 2019 so far, five of the six highest-grossing films worldwide have been Disney properties; the sixth (Spider-Man: Far From Home) was a joint endeavor between Sony and Disney-owned Marvel. The company’s reach is staggering: It owns, among scores other entities, Pixar, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars, and as of earlier this year, the film and TV assets formerly held by 21st Century Fox — in addition to its own extensive and much-beloved back catalog, lots of which is now available to stream via the just-launched Disney+ service.

Disney is in the entertainment business. But what it’s selling isn’t entertainment, exactly — that’s just the vehicle for its real product, and that product has shifted and morphed over time. At one time, a big part of what Disney was selling was a vision of a utopian future, as you know, if you’ve been to Tomorrowland or Epcot at Walt Disney World.

In his speech at the opening day of Disneyland in 1955, Walt Disney himself pointed to his vision of the park as a place where nostalgia and forward-looking inspiration could coexist: “Here age relives fond memories of the past, and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future.”

Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Walt Disney at the Disneyland grand opening in 1955.

But as we come to the end of this banner year for Disney, it’s clear that what the company wants to sell us, going forward, is a seemingly infinite heap of Proustian madeleines. Certainly the warm fuzzies have been one of Disney’s main exports for a long time, but some kind of tipping point was reached in 2019. Now, it seems evident that Disney sees provoking existential homesickness as its main job. Nostalgia is its real product.

Consider Toy Story 4, the fourth film in a series that debuted in November 1995. If you were 8 years old and saw Toy Story in theaters when it opened, you might have brought your own 8-year-old to see the new film earlier this year.

That’s a remarkable stretch of time, and the Toy Story series has stayed remarkably thematically coherent over that time. It’s a set of stories about the passage of time, about how nothing stays the same, about the fact that kids grow up and leave home — that’s why Toy Story 3 left parents bawling when Andy finally grew up and didn’t need his toys anymore. The toys, in a sense, are the parents’ stand-ins. And Toy Story 4, in which some of the toys opt to live a child-free life, feels an awful lot like a movie about being an empty nester, something that could render a parent munching popcorn with their third grader a bit verklempt, thinking about their own now-empty-nester parents who once took them to see Toy Story.

That’s the good kind of nostalgia. And the Toy Story series has successfully refreshed its basic premise over two decades — toys get lost, toys get found — in part through its willingness to surprise viewers, to crack jokes and be a little creepy and think outside the (toy) box with its narratives. So when we find ourselves feeling homesick, in a story about the passage of time, it works.

I think of this approach as generative nostalgia. It’s a way for Disney to use memory, to tap into the audience’s particular madeleines, to bolster the storytelling itself (and make an enormous wad of cash, too). Not every attempt lands, but when movie studios try to tap into nostalgia in order to generate fresh new stories with universal themes, to get creative with the familiar, it’s a good thing for art.

Pixar Animation Studios / Walt Disney Pictures

From Toy Story 4, we got Forky.

If Toy Story 4 was an example of Disney harnessing generative nostalgia, however, its so-called “live-action” remake of The Lion King was just the opposite. The film was never meant to be a standalone movie; its success was always fully dependent on the long-entrenched popularity of the 1994 animated film it recreates, in some cases shot for shot. It’s an entirely unnecessary movie — a way for Disney to test-drive high-end, lifelike CGI and get people to pay for it. And without the imaginative, sometimes visually wild artwork of the original, it falls very flat, with no new perspective on its source material.

Call it derivative nostalgia: For most audiences, The Lion King and Disney’s other live-action remakes (Aladdin was another huge hit this year) are interesting only insofar as they promise to deliver a (slightly) new spin on a beloved classic, without straying too far. We still get “Can You Feel the Love Tonight,” but it’s Donald Glover and Beyoncé. A copy of the original with some of the details tweaked. That’s the appeal.

And while derivative nostalgia has its place — we rewatch our favorite movies for a reason, because we like the feelings and memories they provoke — Disney seems intent on adopting it as a modus operandi, judging from the number of remakes the company has announced. It will depend on the built-in audience of people who loved Lady and the Tramp or 101 Dalmatians to pony up for a ticket or subscribe to Disney+ and ensure these projects’ success.

But I’m convinced the urge to use your giant piles of money to endlessly replicate the past can’t be good for a culture. Certainly, human culture is cumulative; we’re always building on what came before. For millennia, storytellers have leaned on the same material, like myths and archetypes, to find new ways to tell stories. But derivative nostalgia stymies the creative impulse, miring us in the same thing over and over again and training audiences to demand the predictable. Vanilla pudding tastes good, but there’s a lot more to food than vanilla pudding.

You can witness the battle for Disney’s soul happening inside Frozen 2

These generative and derivative modes of nostalgia seem to be warring inside inside Frozen 2, which is pleasing and enjoyable even if it’s clearly designed to function as an ATM for Disney, with Frozen’s previously established fanbase acting as the bank account behind the screen. It is, thank God, no Olaf’s Frozen Adventure.

The Frozen films are aimed primarily at little girls and boys, of course — Disney’s long-running core constituency for stories about princesses and talking animals (or snowmen). But, given that the first movie came out six years ago, Frozen 2 is also for older kids. And one of the most notable things about the movie is that it’s also for their parents.

Perhaps following Pixar’s lead, the more traditional Disney Animation studio has caught onto the fact that if you want grown-ups to be happy when they take kids to the movie theater, you’ve got to make something they’ll enjoy, too. So Frozen 2 leans (more noticeably than its predecessor) into jokes the adults will appreciate, and one in particular: While the kids at my screening howled at Olaf’s slapsticky misadventures, the adults were the ones laughing as Princess Anna’s hunky boyfriend Kristoff crooned his very ’80s-sounding power ballad “Lost in the Woods.”

During a recent interview, Josh Gad (who voices Olaf) joked that the song “speaks to all of us that grew up in the ’80s.” And he’s totally right. The voice of Kristoff, Jonathan Groff, says he was surprised when the song was handed to him: “I couldn’t believe that they were going to go there,” he said, calling it “truly shocking” and later saying it has the energy of Michael Bolton. The song is about how much Kristoff needs Anna in his life; in the film, he sings it during a fantasy sequence of finding her, backed by a chorus of singing reindeer. (The official Frozen 2 soundtrack includes a version of the song by Weezer, which kind of says everything.)

As Gad pointed out, it’s definitely a sight gag for the olds in the room — the younger Gen X and older millennial parents who’ve come to see Frozen 2 with their kids, and are now being rewarded with their own extended musical joke. What’s funny about it is that the musical-style “Into the Woods” parodies was already ridiculous by the time most gen-Xers and millennials became adults; what we’re reminded of now is the sheer goofiness that was so prevalent back then, when romantic ballads were sung by guys with bad hair surrounded by unironic kitsch.

Kids born in the 21st century won’t get the joke. But Frozen 2 isn’t exclusively for them; it’s for 20th-century kids, too. In fact, though its action is set just three years after the end of Frozen, it is, like Toy Story, about the passage of time, and what it’s like to grow older. Olaf sings a song about how things don’t make sense to him now, but they will someday; Anna and Olaf reflect on how they hope everything will stay the same, even though — spoiler alert — of course, they won’t.

Walt Disney Pictures

The gang’s all back together in Frozen 2.

So Frozen 2 provokes all kinds of nostalgia. For kids who’ve already spent years dressing up as Anna and Elsa and driving their parents to distraction with “Let It Go,” the new film is a return to the happy land of Arendelle, where they’ve had many adventures. For teenagers who saw the original Frozen when they were 8 or so, but are now in high school, it’s a reminder of how far they’ve come. And for adults, it tugs on decades-old heartstrings — not just the chuckling memory of’ 80s power ballads, which might be the madeleine that reminds some of dancing at prom, but also the Disney princess stories so many of us grew up watching.

Whereas the original Frozen is a bit of an odd film — its plot structure feels a little out-of-sync with Disney’s usual storytelling, and its “true love’s kiss” comes not from a prince but a sister — Frozen 2 is much more conventional. Frozen retained some of the eerie strangeness of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale it was (very) loosely based on; Frozen 2 goes back to the usual adventure-and-return structure that has made so many classic Disney movies a success. It’s familiar. It’s comfortable.

By my lights, Frozen 2 is still a plenty enjoyable film, even if it lacks its predecessor’s subversive spark. But for me, watching generative and derivative nostalgia spar within it prompted a different sense of the familiar: bleakness about the future of mouse-eared entertainment. Disney, whatever its faults, has often been a pioneer in storytelling; now it’s resting firmly on its laurels, too often electing to spin the wheel again rather than try to reinvent it.

Nostalgia has its place. Remembering the feeling of homesickness reminds us where we came from, that we come from somewhere. But too much yearning for the past without a concomitant attempt to live in the present and push toward the future is a dangerous trap for a culture to fall into, both because it risks becoming stagnant in its art and because it may begin to to worship the past as the only place worth living in. Too much yearning for the past makes us incurious about the world. And if, as Proust wrote, the past we remember is not necessarily the one that existed, remaining stubbornly beholden to it can render us altogether incapable of dealing with the present.

The bigger Disney gets, the more it controls what most Americans — and people around the world — will see at the movies and on their TV screens, and thus it bears enormous responsibility for seeing into the future. Looking backward too much, recycling old content and relying on old formulas endlessly, becomes a snake eating its own tail.

As the endless stream of reboots and remakes and sequels and revivals that currently dominates entertainment attests, nostalgia sells. But it is also the thing most easily packaged to sell. Recycling content is the low-hanging fruit. And when Disney leans into the least creative sort of recycled content, live-action remakes — something nobody’s really asking for — it’s signaling how little it’s interested in originality.

Even when those remakes take a risk — for instance, by casting black actress Halle Bailey as Ariel in The Little Mermaid — it’s worth noting how safe the “risk” really is. Being a creative leader who celebrates inclusivity means daring to build something new, and trusting the artists to draw audiences into a new story. It doesn’t mean casting new faces in old, well-trodden roles with guaranteed built-in audiences because you’re not sure audiences will turn up otherwise. It doesn’t mean defaulting to reviving your past.

Which, ironically, is something Walt Disney was determined to keep his company from doing. As quoted in the 2007 Disney animated film Meet the Robinsons, he pushed for just the opposite: “Around here, however, we don’t look backwards for very long. We keep moving forward, opening up new doors and doing new things, because we’re curious. And curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.”

Frozen 2 opens in theaters on November 21.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2OvMLXf

0 notes

Text

On Frozen 2 and Disney’s nostalgia problem

Elsa’s back. | Walt Disney Pictures

Disney used to always be looking forward. These days, it increasingly only looks back.

Nobody was more nostalgic than Marcel Proust.

The French novelist’s six-volume masterwork In Search of Lost Time is narrated by a man who’s remembering his youth, and it explores how strange and unreliable memory can be. Throughout the series, the notion of “involuntary” memory is a recurring theme, but it’s particularly important in the famous “madeleine” scene.

The scene comes early in the first volume, Swann’s Way, when the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea immediately plunges the narrator into a vivid childhood memory. It’s so well-known that it remains a cultural reference point even today, more than a century after Swann’s Way was published: To say that something is your “madeleine” is shorthand for any sensory experience that brings back a flood of childhood memories (even though mounting evidence suggests that Proust’s version may have just been soggy toast).

That sensory experiences can trigger powerful memories, particularly of youth and childhood, was not a particularly earth-shattering insight on Proust’s part — lots of people have had similar episodes. And while not all of his narrator’s recollections are fond, a lot of them seem presented through a haze of affection — the reliability of which, as the narrator us himself, is a little suspect. “Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were,” he writes.

Maurice Rougemont/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Marcel Proust famously wrote about madeleines as he explored the ways our memories are triggered.

Proust aptly describes the concept of nostalgia: a sentimental yearning for the past, which Merriam Webster defines, succinctly and evocatively, as “the state of being homesick.” And while we periodically recall certain moments as being worse than they actually were (I think of the 30 Rock episode in which Liz Lemon is shocked to discover that her memories of being bullied in high school are faulty, and she was the one doing the bullying), the past often takes on a rosy hue.

Time, distance, and the occasional dash of willful ignorance are effective modifiers. They’re why societies collectively hallucinate Golden Ages, and why so many people find the idea of making America “great again” appealing. It’s less about conserving the good of the past, and more about rejecting the present.

Nostalgia is not, as a mood, inherently bad. Sometimes, feeling a bit homesick is good. But when that feeling becomes our default posture, our guiding light, it starts to become ... troubling? Inhibiting, maybe? Stifling? If the past was when things were good, why bother to build a new future? Better to just keep reinventing the past.

Which brings us to Disney, and to Frozen 2.

Disney used to be a company that looked forward. These days, it seems more interested in looking back.

Disney now controls the lion’s share of the movie industry. In 2019 so far, five of the six highest-grossing films worldwide have been Disney properties; the sixth (Spider-Man: Far From Home) was a joint endeavor between Sony and Disney-owned Marvel. The company’s reach is staggering: It owns, among scores other entities, Pixar, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars, and as of earlier this year, the film and TV assets formerly held by 21st Century Fox — in addition to its own extensive and much-beloved back catalog, lots of which is now available to stream via the just-launched Disney+ service.

Disney is in the entertainment business. But what it’s selling isn’t entertainment, exactly — that’s just the vehicle for its real product, and that product has shifted and morphed over time. At one time, a big part of what Disney was selling was a vision of a utopian future, as you know, if you’ve been to Tomorrowland or Epcot at Walt Disney World.

In his speech at the opening day of Disneyland in 1955, Walt Disney himself pointed to his vision of the park as a place where nostalgia and forward-looking inspiration could coexist: “Here age relives fond memories of the past, and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future.”

Allan Grant/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Walt Disney at the Disneyland grand opening in 1955.

But as we come to the end of this banner year for Disney, it’s clear that what the company wants to sell us, going forward, is a seemingly infinite heap of Proustian madeleines. Certainly the warm fuzzies have been one of Disney’s main exports for a long time, but some kind of tipping point was reached in 2019. Now, it seems evident that Disney sees provoking existential homesickness as its main job. Nostalgia is its real product.

Consider Toy Story 4, the fourth film in a series that debuted in November 1995. If you were 8 years old and saw Toy Story in theaters when it opened, you might have brought your own 8-year-old to see the new film earlier this year.

That’s a remarkable stretch of time, and the Toy Story series has stayed remarkably thematically coherent over that time. It’s a set of stories about the passage of time, about how nothing stays the same, about the fact that kids grow up and leave home — that’s why Toy Story 3 left parents bawling when Andy finally grew up and didn’t need his toys anymore. The toys, in a sense, are the parents’ stand-ins. And Toy Story 4, in which some of the toys opt to live a child-free life, feels an awful lot like a movie about being an empty nester, something that could render a parent munching popcorn with their third grader a bit verklempt, thinking about their own now-empty-nester parents who once took them to see Toy Story.

That’s the good kind of nostalgia. And the Toy Story series has successfully refreshed its basic premise over two decades — toys get lost, toys get found — in part through its willingness to surprise viewers, to crack jokes and be a little creepy and think outside the (toy) box with its narratives. So when we find ourselves feeling homesick, in a story about the passage of time, it works.

I think of this approach as generative nostalgia. It’s a way for Disney to use memory, to tap into the audience’s particular madeleines, to bolster the storytelling itself (and make an enormous wad of cash, too). Not every attempt lands, but when movie studios try to tap into nostalgia in order to generate fresh new stories with universal themes, to get creative with the familiar, it’s a good thing for art.

Pixar Animation Studios / Walt Disney Pictures

From Toy Story 4, we got Forky.

If Toy Story 4 was an example of Disney harnessing generative nostalgia, however, its so-called “live-action” remake of The Lion King was just the opposite. The film was never meant to be a standalone movie; its success was always fully dependent on the long-entrenched popularity of the 1994 animated film it recreates, in some cases shot for shot. It’s an entirely unnecessary movie — a way for Disney to test-drive high-end, lifelike CGI and get people to pay for it. And without the imaginative, sometimes visually wild artwork of the original, it falls very flat, with no new perspective on its source material.

Call it derivative nostalgia: For most audiences, The Lion King and Disney’s other live-action remakes (Aladdin was another huge hit this year) are interesting only insofar as they promise to deliver a (slightly) new spin on a beloved classic, without straying too far. We still get “Can You Feel the Love Tonight,” but it’s Donald Glover and Beyoncé. A copy of the original with some of the details tweaked. That’s the appeal.

And while derivative nostalgia has its place — we rewatch our favorite movies for a reason, because we like the feelings and memories they provoke — Disney seems intent on adopting it as a modus operandi, judging from the number of remakes the company has announced. It will depend on the built-in audience of people who loved Lady and the Tramp or 101 Dalmatians to pony up for a ticket or subscribe to Disney+ and ensure these projects’ success.

But I’m convinced the urge to use your giant piles of money to endlessly replicate the past can’t be good for a culture. Certainly, human culture is cumulative; we’re always building on what came before. For millennia, storytellers have leaned on the same material, like myths and archetypes, to find new ways to tell stories. But derivative nostalgia stymies the creative impulse, miring us in the same thing over and over again and training audiences to demand the predictable. Vanilla pudding tastes good, but there’s a lot more to food than vanilla pudding.

You can witness the battle for Disney’s soul happening inside Frozen 2

These generative and derivative modes of nostalgia seem to be warring inside inside Frozen 2, which is pleasing and enjoyable even if it’s clearly designed to function as an ATM for Disney, with Frozen’s previously established fanbase acting as the bank account behind the screen. It is, thank God, no Olaf’s Frozen Adventure.

The Frozen films are aimed primarily at little girls and boys, of course — Disney’s long-running core constituency for stories about princesses and talking animals (or snowmen). But, given that the first movie came out six years ago, Frozen 2 is also for older kids. And one of the most notable things about the movie is that it’s also for their parents.

Perhaps following Pixar’s lead, the more traditional Disney Animation studio has caught onto the fact that if you want grown-ups to be happy when they take kids to the movie theater, you’ve got to make something they’ll enjoy, too. So Frozen 2 leans (more noticeably than its predecessor) into jokes the adults will appreciate, and one in particular: While the kids at my screening howled at Olaf’s slapsticky misadventures, the adults were the ones laughing as Princess Anna’s hunky boyfriend Kristoff crooned his very ’80s-sounding power ballad “Lost in the Woods.”

During a recent interview, Josh Gad (who voices Olaf) joked that the song “speaks to all of us that grew up in the ’80s.” And he’s totally right. The voice of Kristoff, Jonathan Groff, says he was surprised when the song was handed to him: “I couldn’t believe that they were going to go there,” he said, calling it “truly shocking” and later saying it has the energy of Michael Bolton. The song is about how much Kristoff needs Anna in his life; in the film, he sings it during a fantasy sequence of finding her, backed by a chorus of singing reindeer. (The official Frozen 2 soundtrack includes a version of the song by Weezer, which kind of says everything.)

As Gad pointed out, it’s definitely a sight gag for the olds in the room — the younger Gen X and older millennial parents who’ve come to see Frozen 2 with their kids, and are now being rewarded with their own extended musical joke. What’s funny about it is that the musical-style “Into the Woods” parodies was already ridiculous by the time most gen-Xers and millennials became adults; what we’re reminded of now is the sheer goofiness that was so prevalent back then, when romantic ballads were sung by guys with bad hair surrounded by unironic kitsch.

Kids born in the 21st century won’t get the joke. But Frozen 2 isn’t exclusively for them; it’s for 20th-century kids, too. In fact, though its action is set just three years after the end of Frozen, it is, like Toy Story, about the passage of time, and what it’s like to grow older. Olaf sings a song about how things don’t make sense to him now, but they will someday; Anna and Olaf reflect on how they hope everything will stay the same, even though — spoiler alert — of course, they won’t.

Walt Disney Pictures

The gang’s all back together in Frozen 2.

So Frozen 2 provokes all kinds of nostalgia. For kids who’ve already spent years dressing up as Anna and Elsa and driving their parents to distraction with “Let It Go,” the new film is a return to the happy land of Arendelle, where they’ve had many adventures. For teenagers who saw the original Frozen when they were 8 or so, but are now in high school, it’s a reminder of how far they’ve come. And for adults, it tugs on decades-old heartstrings — not just the chuckling memory of’ 80s power ballads, which might be the madeleine that reminds some of dancing at prom, but also the Disney princess stories so many of us grew up watching.

Whereas the original Frozen is a bit of an odd film — its plot structure feels a little out-of-sync with Disney’s usual storytelling, and its “true love’s kiss” comes not from a prince but a sister — Frozen 2 is much more conventional. Frozen retained some of the eerie strangeness of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale it was (very) loosely based on; Frozen 2 goes back to the usual adventure-and-return structure that has made so many classic Disney movies a success. It’s familiar. It’s comfortable.

By my lights, Frozen 2 is still a plenty enjoyable film, even if it lacks its predecessor’s subversive spark. But for me, watching generative and derivative nostalgia spar within it prompted a different sense of the familiar: bleakness about the future of mouse-eared entertainment. Disney, whatever its faults, has often been a pioneer in storytelling; now it’s resting firmly on its laurels, too often electing to spin the wheel again rather than try to reinvent it.

Nostalgia has its place. Remembering the feeling of homesickness reminds us where we came from, that we come from somewhere. But too much yearning for the past without a concomitant attempt to live in the present and push toward the future is a dangerous trap for a culture to fall into, both because it risks becoming stagnant in its art and because it may begin to to worship the past as the only place worth living in. Too much yearning for the past makes us incurious about the world. And if, as Proust wrote, the past we remember is not necessarily the one that existed, remaining stubbornly beholden to it can render us altogether incapable of dealing with the present.

The bigger Disney gets, the more it controls what most Americans — and people around the world — will see at the movies and on their TV screens, and thus it bears enormous responsibility for seeing into the future. Looking backward too much, recycling old content and relying on old formulas endlessly, becomes a snake eating its own tail.

As the endless stream of reboots and remakes and sequels and revivals that currently dominates entertainment attests, nostalgia sells. But it is also the thing most easily packaged to sell. Recycling content is the low-hanging fruit. And when Disney leans into the least creative sort of recycled content, live-action remakes — something nobody’s really asking for — it’s signaling how little it’s interested in originality.

Even when those remakes take a risk — for instance, by casting black actress Halle Bailey as Ariel in The Little Mermaid — it’s worth noting how safe the “risk” really is. Being a creative leader who celebrates inclusivity means daring to build something new, and trusting the artists to draw audiences into a new story. It doesn’t mean casting new faces in old, well-trodden roles with guaranteed built-in audiences because you’re not sure audiences will turn up otherwise. It doesn’t mean defaulting to reviving your past.

Which, ironically, is something Walt Disney was determined to keep his company from doing. As quoted in the 2007 Disney animated film Meet the Robinsons, he pushed for just the opposite: “Around here, however, we don’t look backwards for very long. We keep moving forward, opening up new doors and doing new things, because we’re curious. And curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.”

Frozen 2 opens in theaters on November 21.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2OvMLXf

0 notes