#the first installment in my anti-dress saga

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i was so sleep deprived when i wrote this, and it shows

Auradon had far, far too many dresses for Mal's taste.

Telling Fairy Godmother to fuck off was probably too far, though.

#i fully just projected onto mal im not gonna lie to you#the first installment in my anti-dress saga#descendants#villain kids#nonbinary mal#nonbinary#coming out#dysphoria#protective carlos my beloved#also let mal say fuck#trans carlos#carlos de vil#evie grimhilde#mal descendants#jay descendants#found family#original writing#ao3#ao3 link

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

More Superhero Comics, Revealing My Reactionary and Facile Engagement with Art as Little More Than the Accrual of Social Capital, Benefiting Nobody But Myself, 4/7/19

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 4: The Tempest #5 (of 6), Alan Moore, Kevin O’Neill, Ben Dimagmaliw, Todd Klein: This is an often very funny issue, set up like a pasted-together UK edition of old US pre-Code horror and crime comics, which, in addition to being funny, plumps up the page count as the plot moves maybe two or three tics forward in advance of the very-last-issue-of-LoEG-ever. The conservative in me wonders why we’re being this digressive in the penultimate number of the entire saga, but then -- at least since “The Black Dossier” -- this project has been more about positioning various strands of fiction and their accrued cultural baggage against one another than telling a propulsive adventure story. Anyway: the realm of Faerie, having easily survived an attempted nuclear strike on the collective imagination by a military-corporate black ops fiction squad comprised entirely of various revamps of James Bond, has brought in every character from every game, comic, cartoon, TV show, movie and book reality with everything for a HUGE apocalypse!

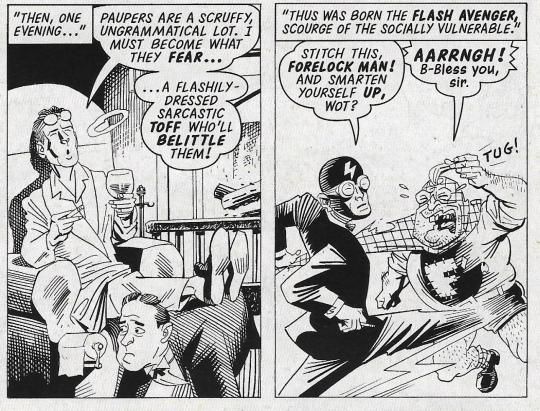

Scenes of bedlam involve: the life story of Victorian painter and murderer Richard Dadd; cameos by Stardust the Super Wizard and David Britton’s Lord Horror; the oeuvre of musician Warren Zevon, brought to terrifying life; a Corbenesque image of a nude muscleman’s massive dick flapping into battle in 3-D; Mick Anglo’s Captain Universe, presented by Moore in unmistakable evocation of his own Marvelman/Miracleman stories of decades ago; a ghost wearing the word CRIME on his head a la Charles Biro’s Mr. Crime, the greatest American comic book horror host; at least one figure from the annals of racist caricature firing powerful sound waves from his mouth; a monster named Demogorgon, the leviathan of Populism, which the heroes allegorically cross as a footbridge en route to a safehouse named the Character Ark; a page-long parody of Batman (via the forgotten UK superhero playboy character the Flash Avenger), describing his origin as motivated entirely by hatred of the poor; a text feature telling of UK comics artist Denis McLoughlin, who worked consistently since the end of WWII, never made enough money to retire, and spent decades as an elderly man drawing for survival on titles he hated, eventually taking his own life in his 80s; and the secret of what happened to all the British superhero characters after the midcentury, which is that they were all eaten by Capitalism, pretty much. I laughed a bunch, but if you think LoEG is tedious shit, this probably won’t turn you around.

*

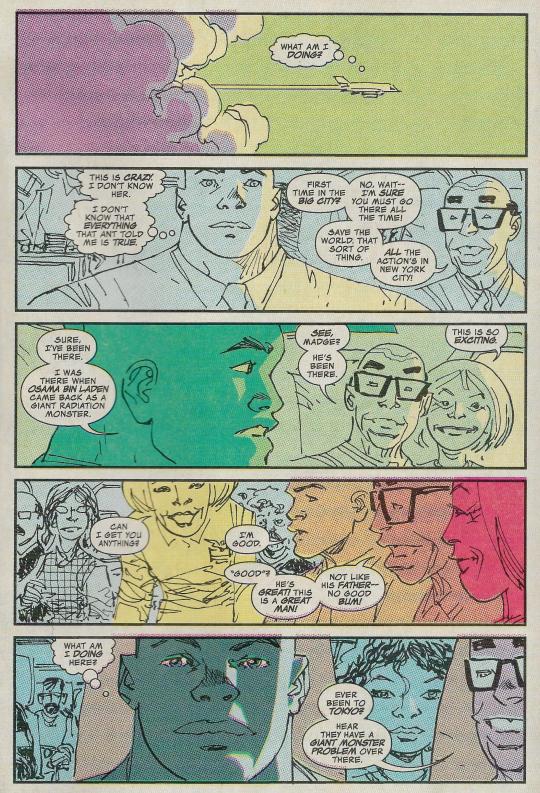

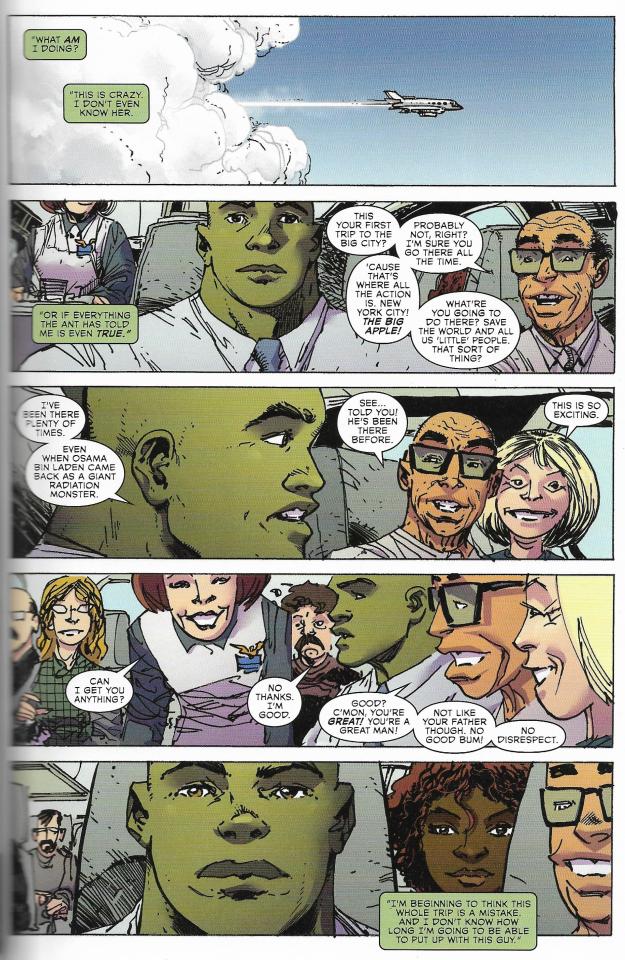

Savage Dragon #242, Erik Larsen, Ferran Delgado, Nikos Koutsis, Mike Toris: The latest installment of the longest-running Image comic written and drawn by one of the Image founders, now deeply dove into problematic network tv drama stuff. The Dragon’s relationship with his partner Maxine is still strained in the wake of her sexual assault, a video of which the Dragon viewed in the police archives; meanwhile, the mother of one of the Dragon’s young children has been telling them all the truth about their parentage, further disrupting the peace of the household. Also, a formerly aggressive sex robot has joined the gang, dressed as an anime maid. And, the Dragon reluctantly teams up with the mid-’00s-vintage sexy heroine character Ant (which Larsen purchased from creator Mario Gully a few years ago) to foil a scheme by elderly elites to project themselves into the bodies of mythic gods in order to provoke the Rapture. Most interesting to me, however, is a bonus segment in which Larsen presents newly-lettered pages of his preliminary solo work on “Spawn” #266 (Oct. 2016), which would later be filled out by contributions from Todd McFarlane, colorist FCO Plascenscia, and letterer Tom Orzechowski.

As usual, I prefer the ‘unfinished’ version (top) to the official release product (bottom).

*

Superman Giant #9, Erika Rothberg, ed.

&

Batman Giant #9, Robin Wildman, ed.

These are two of those 100-page DC superhero packages they sell for five bucks exclusively at Walmart (for now; later this year they’re gonna have them in comic book stores too), which marry one new 12-page story per issue with three full-length reprint comic books from elsewhere in the 21st century. I just wanted to know what was inside them. Here is what I found:

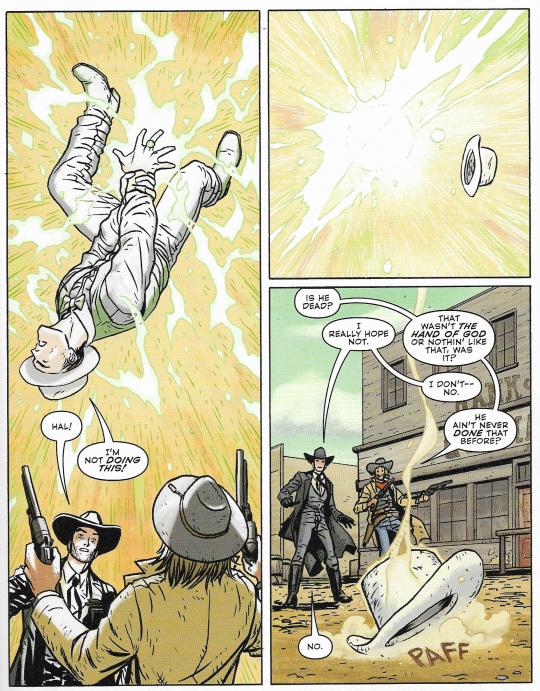

-The new Batman comic is written by Brian Michael Bendis as a very conspicuously all-ages prospect, where the story is about nothing more than what it’s about, and the title character is presented as a serious-minded but inquisitive and compassionate man of adventure. This issue -- just in time for the remix of “Old Town Road” featuring Billy Ray Cyrus -- Batman and Green Lantern travel back to the Old West, trade in their superhero outfits for cowboy clothes, and meet up with Jonah Hex. Nick Derington draws the heroes smooth and squinting with Swanian sincerity, and Dave Stewart colors it all bright and sunny. This is not my thing at all, but it’s confident to the point of acting like almost a rebuke to the rest of the book, where literally everything else is chapter whatever of a nighttime doom ballad drawn by either Jim Lee or something trying very hard to look like him.

-Like:

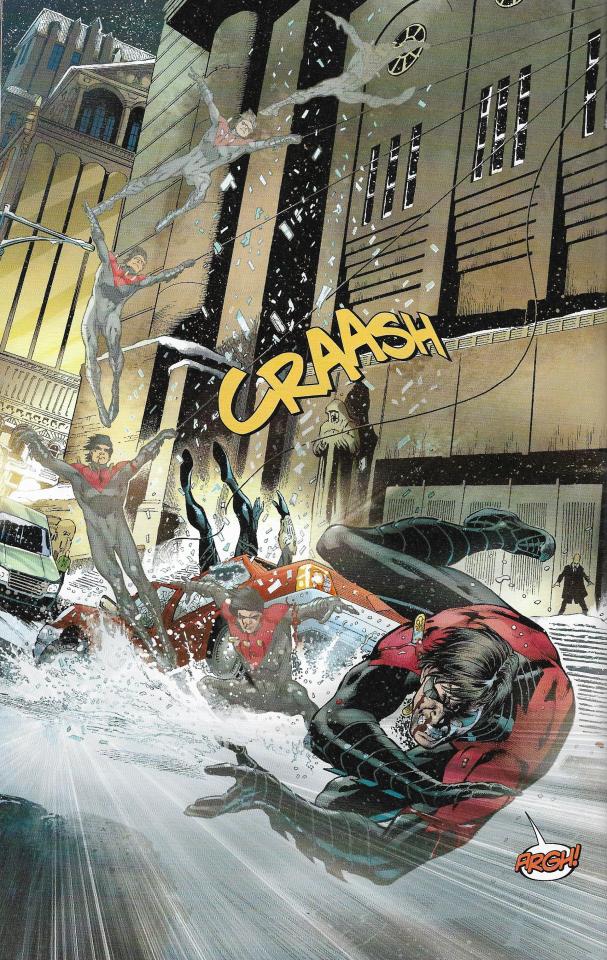

I can spot the differences, sure - if nothing else, reading superhero comics trains you to spot differences in otherwise similar things. But, there is absolutely an aesthetic at work. The top page is from an issue of “Nightwing” that tied into the 2012 “Night of the Owls” crossover in the Batman titles, produced by a seven-person drawing and coloring team fronted by pencillers Eddy Barrows & Andres Guinaldo. The writer, Kyle Higgins, has Dick Grayson fight his semi-immortal great-grandfather, who is an assassin for the Court of Owls: one of the more popular recent Batman organizations of villainy, presented here as a fascist group mediating society’s function through murder from the gray space between social classes. The Graysons, therefore, are the Gray Sons, but Nightwing resists the pull of destiny by winning a big fight, slinging the villain over his shoulder, and walking away toward a better future of just beating the shit out of bad people instead of killing them, I think. The Batgirl story -- from 2011, written by Gail Simone -- is comparatively orthodox, finding the character gripped with uncertainty about the superhero life and going about some downtime character-building activities, though most of it’s a big fight with a villain with a tragic past. The penciller, Ardian Syaf, kind of has trouble blocking the action so that characters’ movements are clear; I think Syaf is best known for having his contract with Marvel terminated in 2017 for slipping what were widely interpreted as anti-Christian and antisemitic references to Indonesian politics into an X-Men comic.

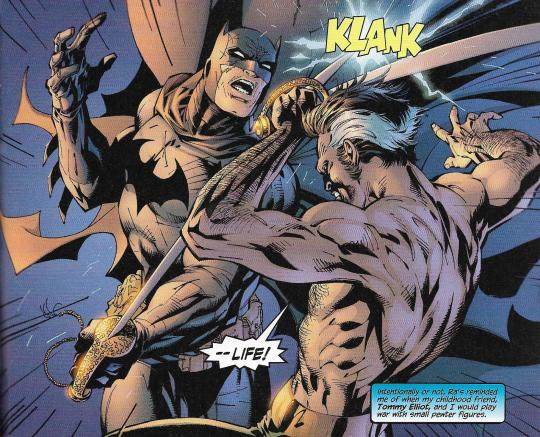

-There is a whole lot of Jeph Loeb among the reprints. He is not a writer who has been in critical fashion for much the past two decades, but he has undoubtedly sold a lot of comics for DC, and they probably feel he can do it again. The Batman book is serializing (deep breath) “Hush”, a 2002-03 storyline notable for its extraordinarily easy-to-solve central mystery, and generally being a taped-together excuse for Jim Lee to draw as many popular Batman characters as possible across 12 issues; it sold like hot cakes. The highlight of chapter 9 is probably a bit where a three person fight ends in one panel, and then one of the characters leaves, and then a second character wakes up from unconsciousness and also leaves, and then the first character comes back and nurses the third (also unconscious) character back to health, and then Batman arrives, all in the transition between the aforementioned panel and the next, which takes place in the same room; such is the befuddling desire to race ahead to more spectacle. Jim Lee (with Scott Williams and Alex Sinclair) is indeed Jim Lee (et al.) throughout, though at one point the team drops a howler of a swordfighting panel where Batman’s blade appears to grows to JRPG length due to what I think is the colorist filling two whoosh lines with the same hue as the swords.

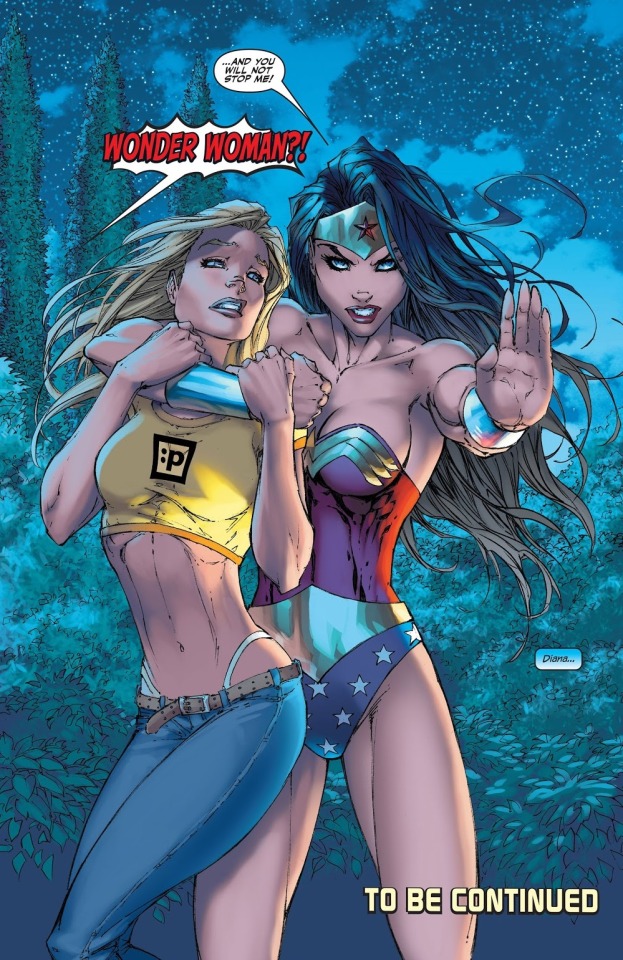

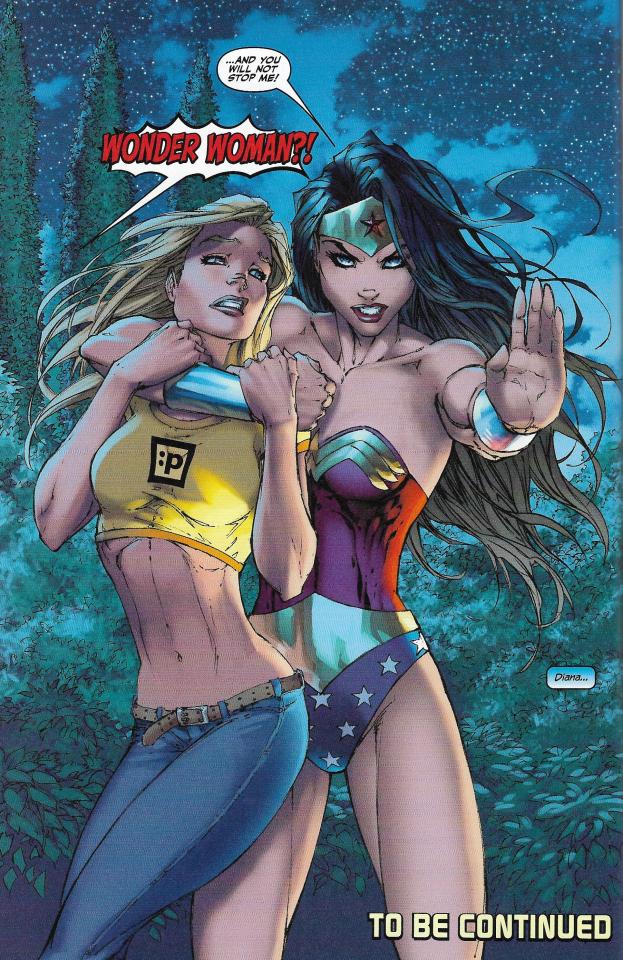

Meanwhile, the Superman book is serializing a 2004 storyline from “Superman/Batman” -- the series where Loeb has Superman describe the action on the page with his own Superman-branded captions, and Batman does the same with Bat-captions, and Superman says tomayto and Batman says tomahto -- in which the late Michael Turner, one of the rock star 2nd generation Image artists, illustrates a new introduction for Supergirl. But this isn’t quite the same comic that was originally published... can YOU spot the difference?

Is this like how Walmart won’t sell CDs that have an explicit content sticker, but with teen superhero g-strings? It’s hard to explain to younger readers how the low-rise/thong panties combo forever sealed the horniness of a generation of het male superhero artists into the late 1990s, and maybe DC doesn’t want to face that. Or, they’re just leery of how Turner slipping some peekaboo glimpse of Supergirl’s underpants or bare thighs into virtually every panel in which she is depicted below the waist might affect the marketability of the comic in 2019 - although I guess it could have happened in an earlier reprint somewhere too.

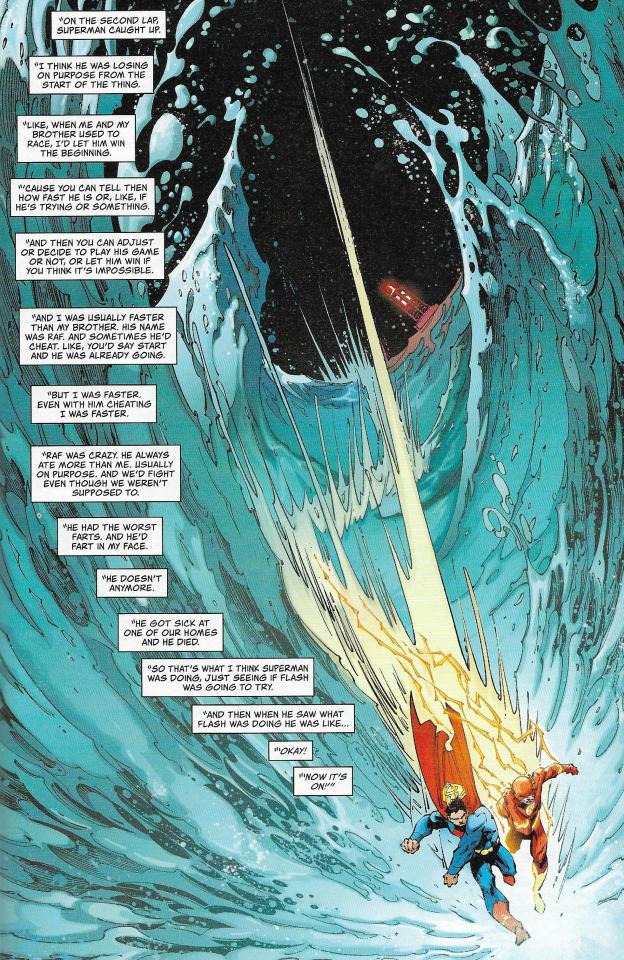

-The new Superman comic is a series of 12 splash pages depicting a race between Superman and the Flash. There is very little sense of speed, because Andy Kubert (inked by Sandra Hope, colored by Brad Anderson) draws the characters as frozen in time in a way that prioritizes muscular tension in the manner of contemporary superhero cover art; at one point the two characters part the sea with the force of their bodies, and it looks to me like they’re gesticulating in front of a theatrical backdrop. And, anyway, the story pulls back almost every other page to depict Batman standing on a ledge, or Lex Luthor in a sinister chair -- or some birds flying next to a building, or the Earth as viewed from space with streaks on it -- as the race occurs deep in the background or off to one side. The point is not excitement, but reflection, as imposed upon us by the between 13 and 21 narrative captions and/or dialogue balloons pasted atop all but the first page.

The writer is Tom King, whose “Mister Miracle” (with artist Mitch Gerads) gets a double-page advertisement later in the book, festooned with breathless blurbs from major media outlets. His narrator here is a little girl who is literally chained in captivity, clutching a Superman doll, and delivering her soliloquy in a manner of a superhero-themed TED talk with handclap repetitions on the nature of contradiction. Being faster than a speeding bullet is a CONTRADICTION. Being as strong as a locomotive is a CONTRADICTION. Leaping tall buildings in a single bound is a CONTRADICTION. Superman is about to lose the race, but then he wins, because to beat the Fastest Man Alive is... a contradiction. No wonder the GQ entertainment desk was blown away. DC comics do this kind of thing a lot, where they just have the writer tell you how great the characters are, and since you’re still reading superhero comics in the 21st century, you’re expected to pump your fists in recognition, because you and the writer and everyone at DC are just big ol’ fans... but I am not, because I am Jesus Christ, the only son of God.

-Elsewhere in the Superman book is an issue of “Green Lantern” from 2006, drawn by Ethan Van Sciver (inked with Prentis Rollins, colored by Moose Baumann), who is known today mostly as a conservative ‘personality’ online. He also netted more than half a million dollars last July in a crowdfunding campaign to make a 48-page comic book which he has not yet finished; funny to see an American right-winger on the French schedule. Funnier still to see the kind of people (mostly guys of a certain age) who mill around such personalities croaking about how diversity is ruining comics, because ALMOST EVERY FUCKING STORY IN BOTH OF THESE 100-PAGE BOOKS IS DRAWN BY EITHER SOME DUDE FROM THE 1990s OR SOMEBODY WORKING EXPLICITLY IN THAT STYLE, but - I guess when you’ve been pampered for so long, every paper cut feels like a ripped limb. Speaking of dismemberment, the writer here is Geoff Johns, who is often pegged as a superhero traditionalist, though he also has a grasp of gory pomp which occasionally pushes the comics he writes into a Venn diagram set with loud youth manga... at least in terms of how the action plays out, all broad and pained. So, needless to say, he’s currently writing “Doomsday Clock”, which is DC’s present attempt to extend the publication life of the valuable “Watchmen” property, so that they needn’t return it to the original creators, per the original writer, Alan Moore.

-To hear Alan Moore say it, the America’s Best Comics line was done on a work-for-hire basis as a means of ensuring prompt payment of the various creators from Jim Lee’s WildStorm, the original publisher. WildStorm was then acquired by DC (Jim Lee is now their co-publisher and chief creative officer), and Moore -- who has been (fairly) criticized in the past for taking ethical stances that cause financial harm to his artistic collaborators, who are in a less economically flexible position than writers in the comic book field -- allowed the line to continue under DC’s ownership, as to cancel everything would disadvantage everyone working on the titles. One of those titles, “Tom Strong”, was written by Moore and pencilled by Chris Sprouse for a while, and then there was a long line of guest creators, and then Moore and Sprouse came back when the ABC line wrapped, so that the concept could reach its logical termination point in an apocalyptic manner... Moore does love an apocalypse. The final story in the Superman book is a very recent, late 2018 issue of “The Terrifics”, in which we find an attempt to revive the DC-owned Tom Strong characters as players in broader DC stories. Jeff Lemire & José Luís are the primary creators. Jack Cole’s Plastic Man is there, as well as the John Ostrander/Tom Mandrake version of Mister Terrific. It’s a lot of offbeat characters; we even see Moore’s own parody of Hoppy the Marvel Bunny, because, I mean, Alan Moore does a lot of riffs on preexisting characters too, right? It’s a big blob of cartoon whimsy, filled with available characters running around. If they’re available, you might as well roll ‘em out, off the new releases rack and into a supermarket reprint package stacked in a box next to squeeze toys and discount Pokémon merchandise, which I bought, because it was really cheap.

-Jog

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arplis - News: Telling Stories in the Dark

This is a guest post from Elizabeth Brooks. Elizabeth grew up in Chester, England, studied Classics at Cambridge, and now lives on the Isle of Man with her husband and two children. Her debut novel, The Orphan of Salt Winds, was described by BuzzFeed as “evocative, gothic and utterly transportive.” Her second novel, The Whispering House will be published in the U.S. by Tin House on March 16th, 2021. You can find her on Twitter @ManxWriter. Content Warning: Mental illness and suicide My sister knew how to tell a story, and she had an appreciative audience in me. I can picture us now: my 7-year-old self, sitting up in bed, hugging my knees, while 10-year-old Rachel delivered her latest installment in a loud whisper from the adjacent attic bedroom. Sometimes excitement got the better of her, the whisper rose to a babble, and Mum or Dad called up the stairs, “You two! Go to sleep! Now!” For a few wriggly, resentful minutes we were silent, but when the coast seemed clear Rachel would resume, with caution. When I think about those storytelling sessions now, the happiness and humour are still there, but they are complicated by the fact that Rachel died by suicide at the age of 28, having suffered years of mental illness. I wish I could remember one of Rachel’s stories from beginning to end, but I’m left with a muddle of impressions, scraps of detail. I know she relished telling stories about spoiled, bullying girls, of a similar age to us, whose crimes escalated until they got their comeuppance, and that she liked to end each episode on a cliff-hanger, leaving me begging for more. Rachel didn’t just make stories up, she also wrote them down. There were stacks of notebooks in her bedroom, crammed with novels at various stages of completion— children’s stories, family sagas, romances, diaries and poems. I was two and a half years younger than Rachel, and I began writing out of a desire — half deferential, half competitive — to emulate her. It was a struggle to keep up. I rarely seemed able to complete a chapter, let alone a book. I kept waiting for a tidal wave of words and images to sweep me away, but it never did. Whilst I was fussing about how to detach page one without ruining the aesthetics of my new notebook, Rachel’s pen would be flying. She would be biting down on the tip of her tongue, her shoulders rigid with concentration, a cup of tea cooling at her side. One day she’d be a published author; I was sure of that. In as far as we were Little Women, she was Jo. I wish there was a name for the condition that destroyed my sister, so that I could describe it in a single word and expect you to understand. It began in childhood and worsened through adolescence and adulthood. Depression was a part of it, but by no means the whole. Schizophrenia comes close, but isn’t quite right. Whatever it was, it made her hate and harm herself. It drove her to run away from home, cut her arms with razor blades and starve herself of food. Sometimes it had her in floods of tears, sometimes she could hardly move for the sheer, dragging weight of it. Medication was a matter of trial and error, and although there were pills that helped a little, others did more harm than good. Counselling was useful, but didn’t get to the heart of the problem. Nothing ever did. As far as writing was concerned, as far as anything was concerned, Rachel was at the mercy of her illness. One day she might be manically, exhaustingly creative; another day she might be too numbed to lift a pen. There were also times — and it’s important I don’t forget this — when the clouds lifted and she was allowed to be herself, for a while. One of Rachel’s less successful night-time stories strikes me as darkly comic, in retrospect. If that sounds heartless, it’s not meant to: mental illness has its absurdities, interwoven with its cruelties, and it would be dishonest to pretend otherwise. I forget how old she was at the time, perhaps 11 or 12? Rachel began with her main character waking up one morning, but rather than launch him headfirst into his story, she proceeded to describe everything — everything — he did, from the moment he swung his legs out of bed. “He found his slippers under the chair, and he put his left foot in the left slipper, and his right foot in the right slipper, and then he went over to the door and took his dressing-gown off the hook and put his left arm in the left sleeve…” I managed to bite my tongue until our man finally made it downstairs, only to discover that his dishwasher needed emptying. “So he opened the dishwasher and took a mug out and put it away in the cupboard, and then he went back to the dishwasher and took another mug out and took it to the cupboard…” At this point I snapped, and Rachel got upset, which made me even angrier. I told her she was being weird, and that her story was boring. In my defense, I was little, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder was not part of my vocabulary. We grew up together, but as my life unfurled, Rachel’s contracted. The stages I passed through — school, university, marriage, children — were typical enough, but set alongside what she was going through they seemed extraordinary, to the point of unfair. She ought to have been doing these things too, or something equally good, not wasting away in psychiatric wards, or overdosing on anti-depressants, or running away from home in a futile effort to escape herself. We both continued to write, but the further we got from childhood, the more difficult it became to show one another our work. I was too embarrassed to share my navel-gazing attempts at poetry, or bits and bobs of prose, and Rachel’s writings, too, grew ever more private. Whenever she was well enough to put pen to paper, she tended to write diaries rather than fiction, seeking relief from her distress by pouring everything onto the page. I believe that’s what she was doing, anyway: I didn’t read her notebooks then and I couldn’t bear to read them now. Rachel died of an overdose in 2005. It was around the same time, when my children were tiny, that I began to write more seriously. It took me a long time to work out what I wanted to write about, and longer still to find an agent and publisher, but I did in the end. The sense of achievement was real, yet it was tinged, as all those other “ordinary” life events had been tinged, with guilt. The logical part of my brain knew I’d done nothing wrong, but there was a sub-logical part, which wasn’t — still isn’t — so sure. How come I’d fulfilled the dream that was Rachel’s, long before it was mine? Had there only been room for one Jo March in the family? Could I, with my greater resilience, be said to have ‘won’ over my more fragile and sensitive sister? There’s no point getting hung up on such questions — and I don’t — but I’m conscious of them simmering away, out of sight. It’s because of Rachel that I became a writer in the first place, and it’s partly because of her that I settle on the subjects I do. All my novels concern the ways in which people, including ‘normal’ people, are essentially mysterious. I seem drawn to create characters whose vivid internal lives drive them to commit strange, often extreme, acts. Storytelling is, in part, an attempt to shed light on darkness. When something seems impossible to understand, it is instinctive to stare hard into the chaos and search for patterns and structures there. A narrative framework may do nothing to alter life’s harsh realities, but it’s comforting to have one, all the same. When Rachel died, I felt numb. I could come up with no adequate response in the immediate aftermath; what had happened seemed so pointless and cruel. Fifteen years on, it still seems pointless and cruel, but writing has helped me to face it. I have never fictionalised my sister’s story, as such, but I have explored mental illness, the impact of suicide, and the complexities of sibling relationships. Putting these things into words, and shaping the words into stories, is healing. Maybe Rachel’s stories — maybe mine, maybe everyone’s — are flashlights sweeping the darkness, making sense of a frightening world, albeit in brief, fragmentary glimpses. This makes me hope that my residual guilt really is misplaced. Perhaps becoming a writer was not, after all, a private ambition that divided us, but a joint quest that unites us still. !doctype> #OurReadingLives #GuestPost #Writing

Arplis - News source https://arplis.com/blogs/news/telling-stories-in-the-dark

0 notes

Text

QUENTIN TARANTINO’S ‘ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD’ “Lightning in a bottle…”

© 2019 by James Clark

The films of Quentin Tarantino are arguably the gold standard of amusement while indirectly excoriating the history of reverence. His recent shot, Once upon a Time… in Hollywood (2019), attends in a rather special way toward his enmity regarding pious foot-soldiers on guard for the sake of half-truths, at best. The target of Hollywood might seem to be a rather minor concern, not to mention that nearly everyone intuits its flaws already. But do they?

We take a ride with Cliff, a movie stunt man/ and double, for actor, Rick, in Rick’s cream-colored Cadillac convertible. While the actor attends to his well-known métier of Western adventures, overblown, underwhelming but passionately popular, Cliff, not being needed to spare the daring in this outing, takes up his other functions as chauffeur and handyman at Rick’s mansion in the exclusive hills. This day, there is the insupportable collapse of the perhaps, sinking brand’s television antenna, the year being 1969. Two magical events occur during Cliff’s hiatus. The first is the remarkable agility of his reaching the roof—sheer acrobatics in leaping from purchase to purchase. When on the irregular roof, his panache is not only bankable but poetry. The second surprise occurs on the freeway with the top down, of course, and music on the radio, to a tune called, “Gamblin’ Man.” The pitch and volume of the sound inundating the fast car can be discerned, with the driver in closeup, that intensity of this degree is, however unspoken, a field of grace. Much remains to be explored regarding Cliff’s solitary day off; but this film invites disparate, rare and desperate action to coalesce. Some months later, and late at night, with the sidekicks about to go their separate ways (and making a last-ditch party of the crisis), Cliff and his pit bull, Brandy, take a walk in the vicinity of Rick’s opulent (but now financially threatened) castle. The acrobat, saying nothing of the earthquake but feeling much, evokes another ecstatic song, far more explosive than the treacly film productions which made the actor affluent, namely, far from matinee-idol, Chris Farlow’s, one-hit-wonder, “Out of Time”—“Baby, Baby, Baby, you’re outta’ time…” And it’s freeway-time again, because the Stones (far more explosive than the earnest writer) know their Hollywood-Rare. The latter’s, wisely distorting the phrase, “Baby, Baby, Baby, you’re outta’ ooaa” [connoting, both “time” and “sight”]. The fateful musical presentation penetrates the mansion next door, the short-lease range of the now-pregnant starlet, Sharon Tate, where a dizzy anti-climax is about to unfold, which obliges us to consider a step far more demanding of nuance than Hollywood can afford. Back to Cliff, on the rich man’s roof, who couldn’t miss hearing the neighbor’s music, a bemusing effort by the laughably named, “Paul Revere and the Raiders.”

We had been up close to her the night before (at an intersection between convertibles; the play-list no improvement on her home choice), on their drive back to Rick’s, not the restauranteur, of course, but the ravenous, for Bogart’s fame. Here she was accompanied by her recent husband, Roman Polanski, still, at that point, a bright light of European avant-garde movies. (His elevated stature depended upon two early 1960’s efforts, Knife in the Water and Repulsion; from there he coasted and became a notorious child molester.) Rick, regarding this sighting as an epiphany, gushes to a less than thrilled Cliff, “He’s been living next door for a month and this is the first time I’ve seen him. I could be one pool party from starring in a Polanski movie…” Rather typically, he cites the big name for bringing to us, Rosemary’s Baby. The “glamorous couple,” dressed in rococo-era costume (once-stifling for all it’s worth in the 18th century) were en route to the Playboy Club, where Sharon cavorted as more polka-Polish than anyone else in the establishment. She and Mama Kass were the life of the party. But the real story had to be “no-bullshit,” tough-guy, Steve McQueen, describing, Louella Parsons-style, the tangled affections of Sharon’s depths. (A pan, while Cliff was still fighting off her music on Rick’s roof, discloses very briefly a lithographic poster by Alphonse Mucha. The sensitivity of the woman’s presence in that work must clearly derive from Polanski’s better days. That day, the so-called auteur was tossing a ball to her miniature dog, while the sweetheart slept snoring.)

There is about the first moments of our film today such miasma-inducing artificiality, that a whole universe of sensibility has to be invented to counter such an aberration. Firstly, there is a clip of a re-run of Rick’s television series of yore, namely, “Bounty Law,” the facile and preposterous rhetoric there being perhaps engaging for an eight-year-old. But soon we realize that those far more advanced in age than that swear it to be some kind of elixir. In the instalment mentioned, after dispatching five attackers in two seconds, he intones, “Amateurs don’t make it!” Cut, then, to a TV fan program where Rick can do no wrong. The peppy master of ceremonies, one, Allen Kinkaid, congratulates himself for including Cliff—by which he gets to maintain that the viewers are not “seeing double.” Rick explains that Cliff saves him from falling off his horse in high action. He admits, “Yes, I can fall off a horse.” This causes mysterious mirth all round. Then Cliff, convinced that the exercise doesn’t make it, blurts out, “I carry his load,” and more slippery goodwill fills the airwaves. Scatology closing the mainstream show. But there is more to Allen Kinkaid (and more to Hollywood madness) than that. The seeming inconsequential host is sitting on Hollywood gold dust, in the figure of Jeramiah Kinkaid, a farm boy and his black lamb, in the Disney film, So Dear to My Heart (1948). Jeramiah brings the lamb to the county fair and goodwill prevails. But the action having occurred in 1903, the lamb and the boy are no longer a joy. (The boy, played by Bobby Driscall, died destitute at age 31.) The skills invested in that little story did manage a topspin that fans are not to be ridiculed for cherishing. But, in failing to vigorously discern the hardness and settle for a pathos rapidly becoming bathos, those fans fail to appreciate how few such gems obtain; and they fool themselves that sentimental and melodramatic extracts are close enough to the template. They actually, in great numbers, become an uncritical and militant cult. Rick moves on to an appointment with his agent who urges, in light of his frequent drunkenness wrecking for good “Bounty Law,” and doing “guest appearances” on the order of a cover of the “Specialty Song,” “Green Door,” that he reboot in Italy, where American has-beens enjoy a second life. Over and above the insider’s savvy pragmatism, he enthuses about what is obviously his client’s favorite role, from some time quite long ago, as wiping out much of the Nazi hierarchy with a flamethrower, in the movie, “The Fourteen Fists” [recalling the many fists in play, killing the fearful pagan, Johan, in the Ingmar Bergman film, Hour of the Wolf ]. The unctuous go-getter, mimes the attack and we hear our protagonist call out the comic-book line, “Anybody for sauerkraut?”

Before plumbing here any more details of this nearly inscrutable myopia, let’s bring to bear more detail of that vigilante saga—from 1968 (set, wouldn’t you know it, in Germany)—where another homogeneous group of militants see fit to kill a painter who does not subscribe to an infinite future in a heaven. The painter, Johan Borg, could be described as some kind of acrobat, inasmuch as he has ventured to reach a dimension of life with which the vast majority are unconcerned. (“Borg,” denoting, in Swedish, a mountain, a castle stronghold. The film in point being set on a German island, there would be the very different lexical sense of a male castrated pig when young.) Cliff, a self-styled, easy-going guy, carries his skillset with significantly more panache than Johan. But, like the artist, who had repeatedly crushed the skull of a rude boy on a deserted beach, along a steep cliff, there is a past in which Cliff has murdered, in this case, his wife; and gone free, as with the kills Cliff delivered during his military days. (The relentless smashing of an intruder at that swan song party, by the sometime reckless athlete, will give us much to ponder.)

During his day with Rick’s Coup de Ville, Cliff, giving a lift to a teenage girl (1969, again)/ entrepreneur who’d rather do tricks than go home, show’s no enthusiasm for the trade (and its possible quicksand); but, on hearing that “home” is the ranch just beyond LA where the boys worked on “Bounty Law,” he persuades the hooker to ease up for the afternoon and let him see a place he hasn’t visited for years. What he sees is another homogeneous group bent on murderous coercion of heretics—a group, however, right across the board, so inept, you’d think they were in some form of rehab, their main action watching television series, in the energies of a seraglio. This being the notorious Manson marauders, another form of resentment arrives therewith, to make us think. “Pussycat,” the unthinking navigator bringing the Cadillac to the cesspool, declares, angrily—after our protagonist discerns that the once-friend and owner of the property receives, as rent, daily favors from a dogma official, named, “Squeaky”— “You’ve embarrassed me!” She, operatically, like the patrician wolf-pack, in Hour of the Wolf, sneering that the now-non-owner whom the cult kept from Cliff on a pretext of his blindness, is a lie, “He’s not blind—you’re the blind one!” (Her ready playfulness, before the reversal, lingers as somehow at least a bit incisive.) More to the matter of short fuse, by remote soulmates, Johan and Cliff, one of the few males of the entourage (the big beachboy nowhere to be seen) has had, while Cliff was weighing the weight, the temerity to cut one of Rick’s tires. On discovering this, and seeing the sneering perpetrator nearby—a scrawny boy looking as if he should get a checkup—our anti-hero, in the course of ensuring that the inmate install the spare, beats the rascal, repeatedly and very bloodily, to within an inch of killing him. That the first punch lifted the vandal skyward, as in Hollywood cartoons, brings to bear Cliff’s state of far from immunity from the general crap. Later he crushes a sneering Bruce Lee during a lull of a very-short lived assignment. And later still, as mentioned, when Squeaky and a few others (still sans-Manson), have the temerity to invade Rick’s place with Cliff visiting, the latter, receiving a superficial gunshot wound (like that received by wife, Alma, from Johan, the hopeful killer), the retaliation is his taking the pudgy lieutenant by the neck and smashing her face, very often, and very hard upon the telephone receiver (more 1969) and other appliances, leaving her unrecognizable as a head. (Could there ever be anything about that sorority which makes your day? Come to think of it, early on, as the so-called “doubles” [Rick and Cliff] pass by to do their storied errands, there are several of them scavenging through a dumpster, pleased to discover and catch by the wind some white sheets [somewhat like Johan’s lost wife and her sheets in the wind]; and as they squeal like happy seagulls, they have something. They have something far more palatable than do-gooders, Simon and Garfunkel, chiming in here, with their so arch, “Mrs. Robinson.” Hollywood being predictable, but Tarantino, not.)

The anticlimax—a maneuver in the same league as Bergman’s theatrical jolts—pertains, not to movie lore in general, nor to crime thrillers in particular, but to the explosive and lovely ways of intent within everyone’s grasp to sustain, however difficult. Tarantino’s priority is to see how advantages, far more cruel and formidable pieties than stupid murder, derive their monstrous power, and can be, though never not numerically dominant, eclipsed by courage and wit. The dust-up with Bruce Lee, eliciting from the now marginal pieceworker, Cliff, the sneer, “You are a little man who [far from the boast he could beat up Cassius Clay] couldn’t hope to carry his [the boxer’s] trunks,” concerns a ridicule of the entire Hollywood Establishment, perhaps a failing of taste, on Cliff’s part, but a revelation of the metaphysical crisis here. More modulated mockery is to be seen during Rick and Cliff’s evening watching old tapes of “Bounty Law.” Depressed Rick can only register contained grief for a lost past. Non-depressed Cliff laughs out loud, seeing through the dramatic travesty, from beginning to end.

It is, then, the seeming fine Sharen Tate, who can lead us, in special ways, to the poison. We first see her returning to LA from Europe, accessing her priority luggage—including a small dog—in the vicinity of a carousel nudging her to be forever a child, as recommended on the highest authorities. She strides, in a slight slow-motion pace, along a corridor with only one exit, emphasized by the glimpse of her Pan-Am stream-line plane. Soon there is a day, like Cliff’s roundabout at the ranch, where, in her tiny, convertible, foreign vehicle (a 1969 phenomenon), she picks up a woman hitchhiker, very unlike Pussycat. Seen from above, there is no doubt that Sharon, granted good bones and good skin, can be as congenial as the girl next door. (The prelude to the lift is a Buffy Sainte-Marie anthem, in tremolo on the radio— “The Circle Game”—a decided improvement over what she listens to at home.)

(“And the seasons they go round and round

And the painted ponies go up and down

We’re captive on the carousel of time

We can’t return we can only look behind

From where we came.

And go round and round and round

In the circle game.”)

(But does this bit of taste rise to the celestial heights her promotors would insist? Or does it speak to the volatility of cogency?) Arriving to the studio and giving the stranger a goodbye hug, we see the sign reads, “Fox.” (The infrastructure by Bergman reads “Wolf.”) Foxy advantage, all the way. Soon she’s done for the day, and she comes upon a movie house showing a film she’s in, along with Dean Martin. We can report she’s not another Jerry Lewis, but her enjoyment of seeing herself cavorting to little palpable effect finds her at some level of apparently remarkable fulfilment. She kicks off her sandals and places her dusty feet on the chair in front; and she foxes down every laugh and cheer in the theatre regarding her supposed martial arts skills. (Back to Cliff and Bruce; and wouldn’t you know, the latter—with his effete wolf howls—is a frequent guest of hers.) She had basked, coming into the show, in finding the cashier and the owner of the theatre typically elated by the presence of a goddess. But there’s a coda to this day even more edifying, in the goddess’ excellent day. On the way home she stops by a bookshop (remember them?) to pick up an order of the Victorian novel, Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891), by Thomas Hardy, for her brainy husband who must, like her, be a Victorian softy. (Bergman kicks ass, similarly, in Cries and Whispers [1972], where Charles Dickens is seen to be an antiquated wimp, and avatar of advantage in the sense of precious careers, precious families and precious patrimonies. Since we’re drawn, by both Tarantino and Bergman being adept dramatic phenomenological philosophers in lodging a pushback against lead-pipe dogmatists, we seem to require mentioning that maniacal, militant careerists, and such, stem from that ancient Platonic myopia as to dynamics while overestimating inert matter. From there, religion, and its causal conclusion, humanitarianism and its obligations to coincide with the former, and science and its quietist retreat have enjoyed pushing around those who see much farther and braver than those who have gone too far with Plato.) With that ascension coming to bear in the anti-climax, we find Rick, a near-perfect wimp, out on the private road, invited to Sharen’s—she being tantamount to an addict of Rick Dalton action television (when she’s not listening to Paul Revere and the Raiders—“Hungry for the good life, baby!”) She wears a team jersey showing 17, her emotional age.

The suffocating majority that is Hollywood is at its apex with the pedantry of those behind the scene—producers, directors, agents, promotors, lawyers, accountants… The breathless Kinkaid raises “double” about our protagonists, only to show he doesn’t know what to do with it, having, the years gone by, allowing a swollen prose to predominate and a withered poetry to die. Earnest cheering for lead-pipe nonsense (see the hunks, see the babes) is the order of our function here. Just as egregious as the bishops presiding over The City of Angels, there is Rick, in semi-depression that his career options have dwindled, meaning that others will man the idiocy where he used to be quite paramount. Before the fading actor takes the advice of the savvy cash-sniffer sold on Italy, there is one more push we need to take into account—involving a director, seemingly near dementia—showing the last of Rick’s several-year stint as a villain. (Immediately after the interview about Italy, Rick rejoins Cliff and cries on the vigorous acrobat’s shoulder. “Don’t let the Mexicans see you crying,” the latter urges, a concern reaching as far as the appalling Mexican directors’ film coups of the present day.)

The obsequious last American helmsman he’ll see, for quite a while, probably aware of a disaster in the making, but knowing a way to lessen the cheapness, promises that modernity and novelty will be the watchword. His patter and timbre of voice about the quality of the chestnut in point somehow overruns his standard positivity, in fascinating ways. Aiming for “lightning in a bottle” and “zeitgeist,” he’s all about changing Rick’s image to “Hell’s Angels” and a new hair style. “I want this to be caliber, not cowboy… Hip…” Rick balks in hearing “hippie…” Though our fading star has for years seen himself as a lucrative entertainer first, to those easily entertained (having purchased a castle of sorts with a pool segueing to the heavens, Architectural Digest-perfect); and a participant in the arts running about #99th (the Polanski moment being a rare jog), that he cared at all would perhaps have factored in the eccentric leader’s rhetoric. And there’s something else crossing Rick’s path which Sam, the inflected snake-oil cheerleader, had to regard as a big plus. Waiting at lunchbreak for an early afternoon first take, he wants nothing more than to read his cowboy novella, and he pauses along a shady point of the concern’s walkway. Nearby, a little girl is reading a script. He asks if he could sit down there; and, after a long pause she says, “Sit.” Not the most cordial welcome; but her presence being far more mature than her age, he becomes curious. Lighting a cigarette and responding to her not small ego, he learns that she never eats before going in front of the cameras, because she wants to concentrate upon her persona. “If I can be a tiny amount better, I will.” She then, the sense of deep resolve losing some traction, declares that Walt Disney is the greatest human to have lived over the past hundred years. She goes on to ask about his book—with a topic about a once-world’s-best wild horse trainer in his 20’s becoming far less than that in his 30’s. Falling, as he would have done during those later acrobatic feats, he’s facing the future with “spine troubles.” “He’s not the best anymore. He’s far from it…” This state of affairs rather oddly brings upon Rick a spate of tears. She tries, by her sincere caring, to help lift the spirits he in fact seldom deals with. But the presence of a vigorous, though wobbly, commitment, has dredged up something he has failed to master, an acrobatic challenge demanding nerve and wit far beyond the ways of those million-dollar dogs. In this crisis, the strain of cheapness cannot be stanched. “Fifteen years, you’ll [the girl] be living it!” [no longer disinterestedly transcending that horde of wolves]. On to the oater and its cliché-fest. Rick flubs many lines; and on a break, back in his trailer, he beats himself up for being so unprofessional and being a drunk. (There are, as mentioned, stories tossed around about his addiction causing the end of “Bounty Law”—lacking bounty and lacking law. Having been inspired by the serious girl, he determines to stop drinking and yet he has a shot before tossing out the bottle). Rick does some homework and his subsequent deliveries of evil do surpass—for how long? —his usual Saturday morning television bilge. (This lost cause is interspersed with Sharen’s delight in a film of hers not noticeably any better than Rick’s. Moreover, Cliff’s radio, as he drives Pussycat to the Spahn Movie Ranch, plays, “Brother Loves Travelling Salvation Show,” another touch of bathos to make to make full sense of.) With a staged conflict between Rick’s “evil” emoting and a Bostonian rationalist, we have the goofy makings of a primal conflict no one is ever going to see as such. The empathetic girl, who was supposedly being held for ransom, tells Rick, “That was the best acting I’ve seen in my life!” Sam, sticking to his sticky story, finds that Rick had reached Shakespearian levels.

There is one more current to add, needing as much pondering as we can manage, that being Cliff’s. We’ll see how amenable our picaresque protagonist can see fit to be stronger and brighter than the level he’s settled for. After the brush with Polanski and Sharon and their effete, rare roadster, the “double” retrieves his severally damaged, early 1960’s Karmann Ghia convertible from Rick’s spacious entrance, performs a little UCLA huddle unwind and returns home—home being a severally damaged trailer at the backside, mud bowl of a drive-in movie of poor status, amidst a terminal truck, various bits of garbage and an operating oil well. (Would that latter apparatus have anything to do with depths?) He kisses and plays with his pit bull, “Brandy,” and presents him with a “Wolf Tooth” dog bone. The easygoing “nonentity” does demand some decorum and patience, at dinner, from the companion/ Alfa. His television, seemingly never turned off, is tuned to a pop singer in a tux, namely, Robert Goulet, a Canadian far less alive than Buffy Sainte- Marie. Discerning the spigot of entertainment may be a large obligation most of us neglect. How Cliff performs, as it happens, is far more momentous than that of anyone else in view here, and we’re obliged to see where he’s going. (Another prelude to a hidden slippage of dialectic is the two hand chow cans being slowly pulled by gravity to the bowl.)

Where he’s going, on that putatively fateful farewell party is far from transparent. It doesn’t involve Brandy chewing off one the intruder’s cock; but hostility does reign. Getting a bit closer is the Manson irregular and enduring fan of “Bounty Law,” lawyering, “My idea is to kill the people who taught us to kill.” Though far from a debater, Cliff, were he to have been able to listen to such entitlement, he’d have recognized the mob murderousness, in lieu of serious discernment. He’d have recognized it, because everyone around him uses it, in order to rough up those, like him (far from fully acute), by way of ostracism, contempt and sabotage. Even more a setback than the flesh wound contracted in the skirmish, there would be weepy Rick, using a flamethrower to kill a wounded sitting duck; and dissolving a supposed friendship and livelihood, for reasons of clinging to advantage. (How anyone can see staunch buddies here must indulge in large selective cognition. Sure, Cliff goes over old episodes with the star, and enjoys them. But he’s especially savoring the stunts [the acrobatics]. Anyone on to “Outta Time/ Sight” is not apt to be a fan of what Rick does.) After the Manson massacre, there’s the likelihood of some contact, on Rick’s terms. More good-natured balance and risk.

In the run-up to Sam’s hoopla, Rick lobbies to the producer to give Cliff some work, somewhere. “He’ll do anything…” That’s tastes of an in-crowd regarding a no-crowd. (On the plane home from Italy—where the jobs were easy for a Hollywood name, and Rick showed much more acute critical powers about European entertainment errors than the American brand—there was the name and his new wife in opulent “Business Class;” and Cliff getting drunk amidst the also rans.) On trampling Bruce Lee, Cliff loses that job, but occasions more gold than the studio is worth. Alma, the widow in Hour of the Wolf, the endeavor being consulted by Tarantino’s golden touch here, quite remarkably shows very little concern for her artist’s husband’s having stoned to death a young boy. Cliff, too, doesn’t lose any sleep about killing his wife. Here we’re in a volatile territory of crime, coming face-to-face with the heroes of civilization (Rick’s work) being strains of a plague the body-count of blasted fruition impossible to count, especially in view of the fact that it will never end. But the tuning is remarkably upbeat, because dudes like Cliff find a way. A T-shirt of his, somewhat covered by a full shirt, spells Champion. (Our film today, despite so many coincidences with the somber defeat in Hour of the Wolf, becomes a cornucopia of inflected verve.)

A coda at the ending credits, finds black and white Rick urging the viewer to smoke, “Red Apples Cigarettes,” which cuts down “bitter, dry” intake and delivers “healthy flavor.” Hollywood and its dubious logical props not nearly seen for its poison the way cigarettes have come to be discerned.

Someone who would have had no difficulty spotting the poison of world history and the merchants getting rich on it, is Heraclitus (flourishing about 500 B.C.); but left behind by pedants and sissies. One of his aphorisms, paradoxically counselling long-term, creative civilization, proceeds, “War is the father of all and the king of all; and some he has made gods and some men, some bond and some free.”

Let’s close things here with those well-known Heracliteans, the Stones.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0tyCOV3SyQc

0 notes

Text

Starting Over (And over, and over) (continued)

I manage to drag my feet through the rest of the “vacation, if it can even be called that, and after an even more awkward still plane-ride back to New York, we officially call it quits. Out the window goes my fantasies of marriage to my high school sweetheart, only to be replaced by an unprecedented despair unlike I had ever felt before. Now, granted I was young, naïve and probably a bit delusional, but I’ll be damned it the whole thing wasn’t a major wake-up call. Having placed all my eggs in this one basket, the relationship, which had more or less become my entire life (so pathetic, I know), I was suddenly faced with the ever-looming, timeless: What’s next?

The answer to this question, which I was in no rush to discover an answer to, possessed as I was, wallowing in my own self-pity, would not reveal itself to e for some months to come.

I was probably 2 years out of an early high school graduation (skipped junior year) and having foresworn college in my anti-establishment, rebellious arrogance, I found myself in limbo with few other options then to find some type of employment until I could find my way back to the “mojo” which seemed to have forsaken me at this stage.

Fortunately, as I mentioned earlier on, a previous Mushroom tripod saddled me with the brilliant idea of taking truck driving lessons and so I had that much to fall back on. Continuing with the CDL training upon return to New York saves me from probably falling any deeper into the well of hopelessness which I had more or less surrendered to at this point. Struggling with agoraphobia, the driving instructors, maybe the last remnant of socialization I could handle after being so scarred by the ultimate betrayal of one so loved, and having previously isolated myself from my entire network earlier on in the summer, my days consist of bus rides to Astoria, Queens, where the driving school is located, and B lines directly home. Perhaps the universe just felt sorry for how pitifully uneventful and directionless my life had become, but one day, I’m shifting gears of a modest size box truck I’m hauling over the Kosciusko Bridge, when the exhausted, Mexican instructor looks over at me and says “kid, what you need is a job”. This comes after his suggestions, as well as that of several of his coworkers, that I become a Hollywood actor. Gosh, if it was only so easy. This sudden observation was probably the most rational thing he had said to me yet. I’ll admit that he took me a bit by surprise with this, and all I could mutter in my daze and preoccupation with the stick shift, was a half-hearted “alright”. This reply seemed suddenly to awaken an enthusiasm within this man, which had probably been dormant for some time, or was at least previously unseen by me. In this newfound excitement, he proceeds to rattle of directions to this mysterious new job, which unbeknownst to me would swiftly realign the direction of my life, if not save it entirely from bottoming out before my very eyes. A few left and right turns later, we arrive in front of what looks like a hardware store on Manhattan Ave. in Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn, a few steps from the nauseatingly hipster center known to all as Williamsburg.

Now this is the part of the story where I wish I could tell you that we stepped into what looked like a modest hardware store, only to pull a lever and descend into a super-secret, subterranean spy-training outpost, but I’m distressed to inform you that this is disappointingly not that kind of movie. However much I am hopeful that one day I will be recruited as a candidate for membership in some elite world-saving organization, it seems I’ll have to hold my breath a little while longer and pacify myself with adventures and heroic agendas of my own making.

Imagine aspirations aside, the next chapter of my life was about to begin within the modest walls of what appeared to be a multi-generational family owned business. Within seconds of arrival, my instructor and now seemingly guardian angel, comes to life with his arms spread wide, shouting “Mr. Simon!” who had appeared through a door which I would soon discover lead to a much larger space than I would have anticipated. This Mr. Simon, as it came to light, was the present towner of this “industrial supply” biz and bore a strong resemblance to Kermit the frog, if Kermit was Jewish, very pale and dressed daily in a rotation of university sweatshirts. After a few words between the men, I was ushered behind the counter and through the door, only to be surprised to find myself walking into a sprawling warehouse. I’d later find out that some years earlier, the family had knocked down the many first floor walls between the several adjoining buildings that they owned, to expand from a modest hand-repair shop into a thriving paper and chemical supply company. They had also built a bit of an empire for themselves, holding nearly a monopoly on housekeeping/hygiene product sales to NYC’s hotels, gyms, and schools, as it were.

Later, I’ll graduate to a hustling and bustling sales-man, but on this day, where I was determined to have no real experience in the field; after a glance at my resume (always shave one hand: success secret), I was hired on the sport as a warehouse hand, which would evolve ever so rapidly, from delivery van driver to errand runner, installation specialist, and eventually to sales-man.

However much I look forward to sharing some of the finer details of the evolution of this job and what it would do for me, the abridged continuation of this saga can be found in the following August 8th, 2017 letter, which I originally pulled together to give a friend of mine an idea of who I managed to get myself into trouble with the Law. While I do intend to weave them together into a more seamless fashion, perhaps for now, this will add a unique element of character into the project, as it stands. In the meantime, however enjoy and thank you for sticking with us, as we treck and trounce through the chronicles of my fuck-ups and failures, and the lessons learned along the way.

0 notes