#the collected poems of ted berrigan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

favourite poems of december

a.r. ammons collected poems: 1951-1971: "dunes"

jennifer robertson shrill shirts will always balloon

n. scott momaday in the presence of the sun: stories and poems, 1961-1991: "the delight song of tsoai-talee"

ted berrigan the collected poems of ted berrigan: "bean spasms"

natalie diaz when my brother was an aztec: "abecedarian requiring further examination of anglikan seraphym subjugation of a wild indian rezervation"

greg miller watch: "river"

joanna klink excerpts from a secret prophecy: "terrebonne bay"

dorothy dudley pine river bay

brenda shaughnessy our andromeda: "our andromeda"

frank lima incidents of travel in poetry: "orfeo"

lehua m. taitano one kind of hunger

no'u revilla kino

linda hogan when the body

paul verlaine one hundred and one poems by paul verlaine: a biligual edition: "moonlight" (tr. norman r. shapiro)

mahmoud darwish the butterfly's burden: "the cypress broke" (tr. fady joudah)

mahmoud darwish the butterfly's burden: "your night is of lilac"

amir rabiyah prayers for my 17th chromosome: "our dangerous sweetness"

sara nicholson the living method: "the end of television"

charles shields proposal for a exhibition

ginger murchison a scrap of linen, a bone: "river"

tsering wangmo dhompa virtual

anne carson the beauty of the husband: "v. here is my propaganda one one one one oneing on your forehead like droplets of luminous sin"

muriel rukeyser the collected poems of muriel rukeyser: "the book of the dead"

anne stevenson stone milk: "the enigma"

david tomas martinez love song

robert fitzgerald charles river nocturne

thomas mcgrath the movie at the end of the world: collected poems: "many in the darkness"

linda rodriguez heart's migration: "the amazon river dolphin"

donald revell the glens of cithaeron

sumita chakraborty dear, beloved

angela jackson and all these roads be luminous: "miz rosa rides the bus"

kofi

#tbr#poetry#poetry list#tbr list#ar ammons#collected poems: 1951-1971#collected poems#a.r. ammons#dunes#jennifer robertson#shrill shirts will always balloon#n. scott momaday#n scott momaday#in the presence of the sun#the delight song of tsoai-talee#ted berrigan#the collected poems of ted berrigan#bean spasms#natalie diaz#when my brother was an aztec#abecedarian requiring further examination of anglikan seraphym subjugation of a wild indian rezervation#angela jackson#miz rosa rides the bus#and all these roads be luminous#ginger murchison#greg miller#watch#dorothy dudley#pine river bay#robert fitzgerald

250 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Centre for Poetry and Poetics Presents: A Reading with Alice Notley

Please register for this event on: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/208112479027

Alice Notley was born in Bisbee, Arizona, on November 8, 1945, and grew up in Needles, California, in the Mohave Desert. She was educated in the Needles public schools, at Barnard College, and at The Writers Workshop, University of Iowa. During the late 60s and early 70s she lived a traveling poet’s life (San Francisco, Bolinas, London, Wivenhoe, Chicago) before settling on New York’s Lower East Side. For sixteen years there, she was an important force in the eclectic second generation of the so-called New York School of poetry. In 1992 she moved to Paris, France and has remained there ever since, generally practicing no profession except for the writing, publication, and performing of her work, and the teaching of an occasional workshop. Notley is the author of more than thirty books of poetry including At Night the States, the double volume Close to Me and Closer . . . (The Language of Heaven) and Désamère, and How Spring Comes, which was a co-winner of the San Francisco Poetry Award. Her epic poem The Descent of Alette was published by Penguin in 1996, followed by Mysteries of Small Houses (1998), which was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize and the winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poetry. Notley’s long poem Disobedience won the Griffin International Prize in 2002. In 2005 the University of Michigan Press published a book of essays on poetry, Coming After. Notley edited The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan (University of California Press), with her sons Anselm and Edmund Berrigan as co-editors. The three of them edited as wellThe Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan. Notley has also edited two volumes of poetry by the British poet Douglas Oliver. Her most recent books are Certain Magical Acts, Benediction, Songs and Stories of the Ghouls, and Grave of Light: New and Selected Poems, winner of the Academy of American Poets’ Lenore Marshall Award. Notley has edited or co-edited three poetry journals over the years: CHICAGO, SCARLET, and Gare du Nord. She is also a collagist and cover artist. In 2015 she was awarded the Ruth Lilly Prize, for lifetime achievement in poetry.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Signaling Through the Flames: Anselm Berrigan, Author of Free Cell

During this time of uncertainty, we’ve asked City Lights authors how they’re doing, what they’re reading, and any advice they have for our community. Their responses have been very inspiring to us, and we hope that sharing them will inspire you as well.

“Signaling Through the Flames” gets its title from Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s timeless work, Poetry As Insurgent Art, which beings with the line, “I am signaling you through the flames …” This line is, in turn, taken from Antonin Artaud in his landmark book The Theatre and Its Double, in which he says “If there is still one hellish, truly accursed thing in our time, it is our artistic dallying with forms, instead of being like victims burnt at the stake, signaling through the flames.” Follow the hashtag #SignalingThruTheFlames across all our platforms on social media to follow the complete series.

City Lights: Where are you?

Anselm Berrigan: I'm in New York City, in my apartment on East 4th Street in Manhattan, with my family -- poet Karen Weiser and our two daughters, Sylvie (12) and June (9). Plus two cats, Nesh and Frankie.

What books make you feel inspired?

Too many to list them all, but in the past few years I've been especially inspired by the late visual artist Jack Whitten's Notes from the Woodshed, which is a considerable chunk of his studio journals—Whitten was a terrific writer, and really dug deep into his relationships with materials, love, work, ideas, the cosmos, society, race, politics, friendship, money, abstraction, art history as he understood and reinvented it for himself—it's incredibly rich, and the man loved to write about paint. I'm permanently inspired by Harryette Mullen's book-length poem Muse & Drudge, Kevin Davies' long poem "Karnal Bunt", from his book Comp., Douglas Oliver's narrative poem & political satire "The Infant & The Pearl", Don Mee Choi's Hardly War, T.J. Clark's books on painting, and millions of poems by millions of people. Namwali Serpell's recent epic novel The Old Drift has also been a revelation.

What gives you hope in this moment? (And/or what are you thankful for?)

Hope—my kids' composure, direct contact with human beings, thoughtfulness, the very notion of resilience as embodied by so many people throughout time in so many ways, bicycle rides, birds, Karen's work, zombie movies, fantasy baseball drafts, Italian mayors yelling on video, "Ode to a Nightingale", the possibility that the failings of so many under-nourished aspects of our society might lead to an actual fundamental reinvention of how we live, how we treat each other, and how our economy, medical infrastructure, and government should work.

Any advice that you’d like to share with our community?

I'm not sure I have any great advice, but I'm finding that focus is difficult right now, and I am much more able to concentrate when I am not roving around on-line, looking for more information than is actually there—there are important sources of news, but the internet right now, for me, is a sinkhole. At the same time, I have four part-time teaching jobs, and they almost all now require working on-line. So I'm conversely finding that direct contact with people—phone calls, emails, text messages, video calls—are hugely important. Little check-ins—are you ok? what do you need?—are crucial. Then as a writer, what do things look like, how do things sound, what are the materials available—having questions & continuing the deep dive into longstanding questions feels crucial too. I'm trying to let things be slow, as much as possible.

***

Anselm Berrigan is the author of many books of poetry: Something for Everybody, (Wave Books, 2018), Come In Alone (Wave Books, May 2016), Primitive State (Edge, 2015), Notes from Irrelevance (Wave Books, 2011), Free Cell (City Lights Books, 2009), Some Notes on My Programming (Edge, 2006), Zero Star Hotel (Edge, 2002), and Integrity and Dramatic Life (Edge, 1999). He is also the editor of What is Poetry? (Just Kidding, I Know You Know): Interviews from the Poetry Project Newsletter (1983–2009) and co-author of two collaborative books: Loading, with visual artist Jonathan Allen (Brooklyn Arts Press, 2013), and Skasers, with poet John Coletti (Flowers & Cream, 2012). He is the current poetry editor for The Brooklyn Rail, and co-editor with Alice Notley and Edmund Berrigan of The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan (U. California, 2005) and the Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan (U. California, 2011). He is Co-Chair, Writing at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts interdisciplinary MFA program, and also teaches part-time at Brooklyn College. He was awarded a 2015 Process Space Residency by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and in 2014 he was awarded a Robert Rauschenberg Residency by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. He was a New York State Foundation for the Arts fellow in Poetry for 2007, and has received three grants from the Fund for Poetry. He lives in New York City, where he also grew up.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Week’s Expert Picks

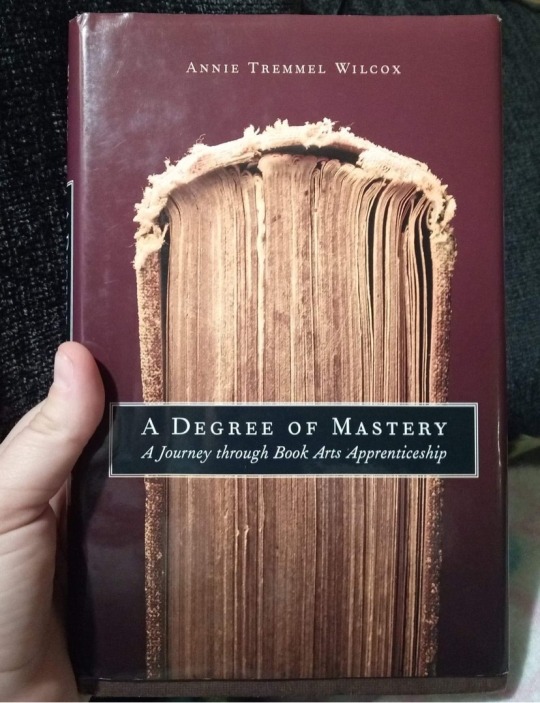

A Degree of Mastery is a con. While it is A Journey Through Book Arts Apprenticeship, this is an unfair title for a book that is at least as much elegy as it is memoir and craft is really the vehicle through which we receive it. I want to be clear: I am ecstatic to have been fooled by this book.

Annie Tremmel Wilcox craftily (heh) weaves vignettes of memoir, detailed explanations of craft, and reflection so clear it might have been purified. A Degree Of Mastery wants you to believe it's a treatise on Book Arts--and it is--but more than that it is a treatise on living a life with dreams and grief.

I'll rewind: this book, on its face, is documentation of life as a Book Arts Apprentice. Wilcox herself is the subject and she clearly and simply explains the ins and outs of book binding and conservation from page one--she explains jargon so easily it's conversational--while interspersing the narrative with the sweet, silly humor of a TV grandmother.

The narrative is broken up with journal entries, excerpts from books on craft, and explanation labels that Wilcox and her colleagues wrote for an exhibit on their work. Straddling the line between conversational and forma, Wilcox makes amazing allusions to past lives that makes her narration three dimensional and slips me slowly into investing.

Okay, I picked up this book because I know the author. I have many times stated outright that I kind of dread reading books by people I know because I am so afraid of reviewing them. This time, I thought "well, book binding is probably cool," while clearly having exactly zero understanding of what book binding even is. (It turns out "preservation is the attempt to save the intellectual content of books while conservation is the attempt to save both the intellectual content and its vehicle...the former is concerned with saving what the human record contains without regard to the forms it winds up in. The latter focuses on the artifact itself, attempts to save *this* book, *this* sheet.") But what kept me reading when I realized I didn't know what I'd gotten myself into was Wilcox's vulnerability and honesty (in the book, not in real life). With each page, a layer is shaved away from the surface and we become nearly cocooned in the conservation department's family dynamic. She also got me invested in conservation, "Implicit in conservation...is the belief that the medium is part of the message--that a book which looks and feels and operates exactly like the original conveys something to the reader which the same thing in another format does not. It is safe to say that a person holding a copy of Walt Whitman's first edition of Leaves of Grass--an edition Whitman personally helped set the type for--experiences the poems differently than he would reading a microfilmed copy of it."

So here is the real magic: Wilcox's treatment of bereavement is one of the very best I've ever read. It is simultaneously accurate and artful. It is a crystalline, beautiful depiction of the most difficult part of life. This is not a long section of the book, but it is maybe the most important.

Deftly, Wilcox uses those aforementioned excerpts to provide reprieve and humor, add perspective, and speak to the audience in a way that adds nuance and rhythm to the book. SE

A look into the former presidents life, from his only niece Mary Trump. It gives personal insight into his life, how he was raised, and the family dynamic between the entire Trump family. She showcases the traumas, toxic relationships, shady business deals, and the neglect that was shown. This is a first-hand account and witness to family interactions, and what makes the family Trump truly stands for.

This is the portrait of the man tweeting and golfing everyday. I applaud Mary for telling this story, she wants the truth to be out there that this family is powerful but also one of the most dysfunctional families in America. The book tends to focus on the patriarch of the family Fred Trump and how his power dynamic was transferred to his two sons Fred Jr and Donald whom both had their own problems.

What the book does is provide insights into Trumps character, why he acts the way he does, and how his mind was shaped by his father. Insights include things like Trump paying someone to take the SAT’s for him, his bragging isn’t directed to people but to an audience of one, and the lack of moral values which were replaced with material. A family of extreme privilege that is extremely dysfunctional in which money is the only value, and how the grudges of estrangement can tear a family apart. CJH

I got a lot of questions and this one answers 150 of them. LAW

It's been a tough week. From fridges on the frits to work bullshit, let's just say this entire week hasn't responded to me as it should, which is perfect placement for Zero Star Hotel by by Anselm Berrigan, a beautiful book about the lows and highs of existence. As well as the middle ground. The son of Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan has been surrounded by poetry and poetics his entire life, therefore he knows the lows and highs. I read this book on my back at the Bowery Poetry Club in NYC a long time ago. Just as it did then. and just as I read it on my feet now, it is a capitol reminder that when life is low, it can only go up. From cadence to collective thought, this book is a good reminder and a million star read. RB

0 notes

Text

10 THINGS I DO EVERY DAY

by Ted Berrigan

wake up smoke pot see the cat love my wife think of Frank

eat lunch make noises sing songs go out dig the streets

go home for dinner read the Post make pee-pee two kids grin

read books see my friends get pissed-off have a Pepsi disappear

From “The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan,” edited by Alice Notley. (c) 2006 by the Regents of the University of California. Published by the University of California Press.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HAPPY BIRTHDAY LOU REED ~*~ THE CLASSICS | DO ANGELS NEED HAIRCUTS? Miss Rosen for AnOther Man

In August 1970, when he was 28 years old, Lou Reed quit The Velvet Underground and moved back into his parents’ home in Long Island, where he stayed for the better part of a year in seclusion to write poetry. He vowed never to play rock and roll again.

“I’m a poet,” Reed publicly declared on March 10, 1971, as he took to the stage of the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, New York. Standing before the likes Allen Ginsberg and Ted Berrigan, who smiled in support, Reed recited a selection of new poems along with the lyrics by The Velvet Underground. Six months later, Reed began recording Lou Reed, his self-titled debut solo album produced by David Bowie and arranged by Mick Ronson.

In 1974, Reed compiled All the Pretty People, a book of poetry that was never published. It is only now that his verse has been unearthed, collected, and released in Do Angels Need Haircuts? Early Poems by Lou Reed (Anthology Editions). The book includes 7” record of the 1971 live reading along with aarchival notes by Don Fleming, and photographs by Mick Rock.

Here, Fleming provides a five-point guide to the poetry of this music icon.

Read the Full Story at AnOther Man

Photo: Lou Reed. Photography Andrew Cifrani

1 note

·

View note

Text

“ I waken, read, write long letters and wander restlessly when leaves are blowing my dream a crumpled horn in advance of the broken arm she murmurs of signs to her fingers weeps in the morning to waken so shackled with love Not me. I like to beat people up. My dream a white tree “

“Whatever is going to happen is already happening Some people prefer “the interior monologue” I like to beat people up “

-selected poems of ted berrigan

#might have to write on ted berrigan#he's fascinating#his collected poems start with a reminder that he wrote these poems#not the reader#which is all against so much of poetry's reliance on transference or mutual recognition or whatever you want to call it#but he's constantly stealing from rilke and whitman and pound and basically all the 1st gen school of ny poets#he's just constantly pissed and elated that he's in love with poetry and awed that loveliness exists#it's hard not to love the guy for his lack of a center#he's fiercely aware that he's not adjusted and forceful about trying to embrace his multidimesionality yet he still hates it?#all his poetry and letters suggest that he would hate to have his work analyzed and so i just wanna push his psychic energy#his preoccupation with his persona versus his self is excellent material

0 notes

Text

Today is the birthday of avant-garde American poet, essayist, and translator Ron Padgett (1942) (books by this author), who once said: “If you match yourself up against Shakespeare, guess what? You lose. It’s not productive. Better to focus on the poem you’re writing, do your work, and leave it at that.” Padgett went to New York to attend Columbia University (1960), where he fell in with a group of poets who favored stream-of-consciousness writing, vivid imagery, and spontaneity. It was the 1960s, and Padgett, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, and Ted Berrigan drew inspiration from the art galleries, museums, dancers, and artists that surrounded them. Padgett’s collections of poetry include Bean Spasms: Poems and Prose (1967, with Ted Berrigan); How to Be Perfect (2007); Alone and Not Alone (2015), and Big Cabin (2019). His collection How Long (2011) was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

0 notes

Text

SPAM Cuts Special: ONE FOR JOHN JAMES (1938-2018)

As the year draws in past midwinter day, we bring you a SPAM Cut festive special. Luke Roberts invites us to dwell upon the warmth of elegy, craft and sheer radiance in the work of Welsh poet John James, who passed away earlier this year.

> John James died in May, true to his word: ‘best to die in summer / when everything is bright / & the earth turns over lightly’. At his final reading in London in April, very ill, he struggled to stand and had trouble holding his book. It was painful to watch but it was beautiful to listen to, and now it’s December and I can still hear his voice. A little Welsh inflection, fragile, but the music coming through clear and exact. I only really met him once, at a reading organised by graduate students in Cambridge in 2010. We took him to the pub beforehand and I bought him a glass of wine. He winced at the options: only New World varieties. From the 2000s onwards he lived part of the year in France, ‘territory of the vine’, writing his exquisite late work. Someone came to our table collecting for charity and he turned to me and quoted Frank O’Hara: ‘a lady asks us for a nickel for a terrible / disease but we don’t give her one we / don’t like terrible diseases’.

> I want to write about John James because he was truly great, but it’s hard to write about John James because if you can’t see it there’s no hope, and if you get it you already know. In Cambridge the older poets talked in hushed tones about his line, how great his line was. And it’s true. From The Small Henderson Room (1969) through to Berlin Return (1983) James worked out a poetry of rigorous sweetness, poised vulgarity, incredible attitude. After that he could do whatever he wanted. He makes it look effortless, but he also shows you over and over the discipline. Style takes work. Early in his correspondence with The English Intelligencer — one of the ‘rowdies’ as J.H. Prynne affectionately called him — he discourses on craft and writes that the whole point of poetry is to be memorable, to be worthy of commitment to memory. Craft is whatever aids this commitment, nothing more nothing less. And the lines come back: ‘Fresh bread can taste so good, it’s so rare / we eat it together’; ‘My shoulders / have learned to be / tense in the night’; ‘& I haven’t a thought in my head that could / sound like a line of Hölderlin’. And more: ‘Pure Chainsaw feeling in the Vat of TLP’; ‘I like to dance so much & a kind of mania / lures me’; ‘A glass of volvic could have made me happy forever’; ‘you’ve just come back / I definitely love you’; ‘art is a balm to the brain / & gives a certain resolution’. The whole of A Theory of Poetry (1977). The great late poem ‘Intersection’, with the wild opening lines: ‘Mao taught us it is a narrative / we must tell of ourselves each day’. They’re the kind of lines you share with your friends, springing to thought with regular buoyancy. They never went away.

> In 1975 James memorialised the German poet Rolf Dieter Brinkmann, killed in a traffic accident in London aged 35. He died on April 23rd, shortly after reading with James and John Ashbery at the Cambridge Poetry Festival. Veronica Forrest-Thomson died a few days later, and the two were commemorated in a volume published by Andrew Crozier’s Ferry Press. James wrote two poems for Brinkmann: one I already quoted in the opening sentence, and another longer work titled ‘One for Rolf’. It begins with ‘displaced April / air in May’, as if the poet’s death has interrupted the seasons. The whole opening stanza turns around subtleties of appearance, the precise quality of dissolution, where ‘we expire like the breeze at evening’. The expiration brings us back to the air, the poet’s breath still lingering in May-time. Erwin Panofsky says somewhere that poets invented the evening, and I believe this to be true. John James writes:

(the struggle for what is light in what is dark

shone to advantage in our own backyard

The first couplet could almost be Brecht. If this isn’t an image of political commitment I don’t know what is. James was a socialist from first to last, and his poems are littered with references to strikes, to reading The Morning Star, going out to meetings, hating the Government, to say nothing of his ferocious Irish Republican poems of the late 1970s and 1980s. But this doesn’t explain why the lines are so masterful. It’s something to do with the movement of articulation: ‘light’ and ‘advantage’ come to rest high in the mouth, at least if you read ‘advantage’ with a hard A. You tense your face a little to hold the line at the moment of its breaking. But ‘dark’ and ‘backyard’ are open-mouthed, exhalation, release.

> I think these lines, like many of James’s, have a double-function. I read them allegorically as an image of optimism, commitment, even faith. But since this is ‘in our own backyard’ I also picture a distinct physical space. And since this is about darkness and the struggle for what is light, I imagine that the poet has lost something and is looking for something in the night. I imagine light from a window in the rooms above the yard. I think about specific places I’ve lived and specific people I’ve known. Forrest-Thomson would call this bad naturalization: but since this is an elegy, I take licence in my feelings. I think of a beautiful line Andrew Crozier was writing around the same time: ‘In torchlight to know where you are / and then switch the beam off’.

> The poem, which moves through 10 short sections, is organised around images of light and around images of the accident. James walks through Cologne in the ‘silvery grey light’, sees a ‘torso on the grass / discarded’ with ‘the shadow trickling / across the road’. Sometimes the two coalesce, as with the ‘Traffic lights, tall / lamp-standards, thin trees’. He quotes Ed Dorn, from Gunslinger: ‘“Speed” says Ed “is not necessarily fast”’. There are other quotations: parts of O’Hara’s dictum ‘the slightest loss of attention leads to death’, and a slightly-switched repeat of a line from the earlier ‘Rough for Rolf Dieter Brinkmann’ I’ve already mentioned: ‘& I haven’t a line in my head that could / sound like a thought of Hölderlin’. The most plaintive line in the poem sounds itself like a quotation or translation, but I can’t trace it: ‘there has been an accident in my life o my life’. And so these lines are like reaching out for support, to steady and further the poem, to do the work of mourning.

> In the conclusion of the poem James gathers his friends closer. Crozier appears ‘in the new good morning day’, looking out of his window in his back-yard in Lewes. He recalls a reading by Ted Berrigan, from ‘Three Sonnets & A Coda for Tom Clark’:

& Ted I heard him read the words “Tomorrow you die” & me I say, “Are you kidding? See you later!”

And in the elegiac mode this poem from 1975 becomes an elegy in advance for Ted — translated by Brinkmann in Guillaume Apollinaire Ist Tod — and for Ed Dorn, and for Crozier, who died in Lewes in 2008, and why not for Tom Clark, too, who himself was fatally struck by a car earlier this year. And why not for Douglas Oliver and David Chaloner and everybody else, gathered beside Rolf and Veronica as the air switches back from May into April.

> Towards the conclusion, light becomes more wholly the medium of consolation:

the history of your life a pagination of existence in which I partly live a slow exposure to the radiance left by you by you & all others

This gesture towards the others, to everyone, is hard to pull off. Sometimes poets do it to get themselves out of trouble, or else it’s a cheap move of bombast designed to cover the cracks. But James always manages it: the movement is measured, controlled, and authentic, the slow burn of feeling. So we have the radiant pagination of existence, and it’s still radiant.

> A couple of weeks ago I showed my students a short poem from the 1990s:

Confession

I throw myself on a eating utensil a nail a tin of lemonade my head against a wall & smash a window no one had asked me to do this

We talked about the Catholic imagery, the act of confession, the tin of lemonade as a kind of parody sacrament, the nail as holy reliquary. We tried to elaborate the elusive humour of the whole thing. We decided that if you switch the eating utensil for a writing utensil, it works as a metaphor for poetry itself: the comic frenzy, the damage, the pushing up against constraints, the struggle. The poet is answerable to no-one. There’s something adolescent and helpless about it, finally inscrutable. And I think of this as the other side of the coin: there’s control and discipline, there’s the line and there’s craft; but there’s also accident, panic, and fervour. And John James did it again and again. There were quiet years following his Collected Poems in 2002, but after In Romsey Town in 2011 he published poems and pamphlets with regularity until the end. You can read some of them in Sarments: New and Selected Poems, the book he was holding on to back in April. You can read it in the Collected Poems. I love it all the way through.

December 19th 2018

~

Text & Image: Luke Roberts

0 notes

Text

Elazar Larry Freifeld interviewed by Lonnie Monka

LM: Larry, you seem to have led a rich life filled with creative activity and family, while also having crossed paths with many of the top literary figures of the Beats and early New York School poets. What has been the biggest impact on your creative activities and literary associations since deciding to emigrate to Israel? Have you felt more or less inspired and/or productive post-aliyah?

ELF: Not really, the basics remain the same wherever you are. Language is a repository of culture and since I was culturally Jewish in America I am even more so here in Israel. The transition of my ethos as a poet from the US to Israel was made easier by the fact that there was already a well established community of expatriate English language writers and poets from throughout the world in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa.

First off, there’s no ‘biggest impact’ on my work beyond what inspires me in the moment; something I hear or touch or read. In this I am a romantic and write in series, until another experience triggers my imagination to embark on another poem. ‘Passion rules the universe’ says Isaac Babel, and the true traveler ‘goes only to get away’ [Charles Baudelaire]. Poems are like little boats in passing….

LM: Part of being a poet is consistently pondering and sometimes even answering questions about the meaning of poetry. Do you have any advice you would give to a young aspiring poet?

ELF: Writing a poem is both process and end-product. “If one could just sit down and write what is in his heart it would be a great book” said Edgar Allen Poe. Don’t ‘think’ poem before you write it. It may or may not originate in thought but rather in feeling or overhearing or seeing or any of the five senses or combination of perception(s). It may even be extra-terrestrial! It is in part an act of discovery and like a mistake, it can never be entirely calculated. Keep an open heart and listening ear, all great art is ‘appropriation’ of what is already there. ‘We are transmitters’, (D.H. Lawrence) conveyances of popular wisdom and prophets of the absurd. Study the classics if you will, follow the rules of the game like chess, then break them but with intelligence and meaning, when you find it.

LM: In your interview with Allen Ginsberg, he mentioned that your poetry reminds him of Charles Resnikov’s work. Do you imagine yourself as writing in his, or anyone else's lineage? Moreover, who are your biggest influences, and have you ever had a poetic mentor?

ELF: To be honest with you, I can’t imagine why Ginsberg compared me to Resnikov as I was never a great reader or admirer of his work; except that we both wrote in the vernacular. So did Carl Sandburg.

No, I never had mentors because I ran away from school when I was 11 years old and didn’t graduate high school until I was 35. There were however many poets both classical and modern who influenced my writing. Too numerous here to mention… lately I have been enamored by Apollinaire and Voznesenski. Found some good things to steal!

I was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan before it became the East Village and my first readings at St. Marks Church, ca 1965 (run by Joel Oppenheimer and Paul Blackburn) hosted many great poets from both the California Renaissance of beat poets headed by Jack Spicer, Gregory Corso, and Allen Ginsberg, and the NY School headed by John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and David Shapiro. If I were to proscribe a circle of poets with whom I most congregated, it must include Jackson MacLow, Paul Blackburn, Jerome Rothenberg, Ted Berrigan, Armand Shwerner, Vito Acconci, Dick Higgins, and especially Tuli Kupferberg. I will never forget a reading I attended of John Berryman reading his sonnets.

As the 60’s progressed into the 70’s I grew more aligned with Dick Higgins at Something Else Press who represented the international concrete poetry movement headed by Emmett Williams and a list of other European and South American poets. Moving to Israel was simply a fulfilment of being a poet and also being a Jew, culturally. I’m not sure I could ever have attained that in America being ‘a Jew writing Hebrew in the ghetto’ as a friend once described my work. Here in Israel I have achieved this balance along with many other expatriated Jewish poets from English speaking countries from throughout the world.

LM: How often do you write these days? And how would you describe your current work? In other words, please tell us a bit about your muse as well as what we can expect to read from you in the future.

ELF: I write less nowadays since I recently discovered that ‘I am myself the poem’. They are mostly seasonal and largely appropriated. I devote a lot of time these days like Ezra Pound collecting and editing poems and stories already written.

__________________________________

This interview was conducted in preparation for the Jerusalism event Back to Back, at Studio of Her Own Gallery, in Jerusalem (February 15th, 2018).

0 notes

Text

Signaling Through the Flames: Edmund Berrigan, Author of More Gone

During this time of uncertainty, we’ve asked City Lights authors how they’re doing, what they’re reading, and any advice they have for our community. Their responses have been very inspiring to us, and we hope that sharing them will inspire you as well.

“Signaling Through the Flames” gets its title from Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s timeless work, Poetry As Insurgent Art, which beings with the line, “I am signaling you through the flames …” This line is, in turn, taken from Antonin Artaud in his landmark book The Theatre and Its Double, in which he says “If there is still one hellish, truly accursed thing in our time, it is our artistic dallying with forms, instead of being like victims burnt at the stake, signaling through the flames.” Follow the hashtag #SignalingThruTheFlames across all our platforms on social media to follow the complete series.

City Lights: Where are you?

Edmund Berrigan: I'm in Brooklyn, in the Prospect Lefferts Gardens neighborhood.

What books make you feel inspired?

I'm reading The New Oxford Book of Seventeenth Century Verse, which I got in a trade. Thinking about race, class, gender, beauty, survival, the mystery of language, the fear of death--then, now and forward. The space between something written and then read. "Love made me poet, / And this I writ; / My heart did do it, / And not my wit."--Elizabeth, Lady Tanfield (1565-1628)

What gives you hope in this moment? (And/or what are you thankful for?)

The faces of people in my neighborhood, whom I don't know, but when in passing we look up at each other and we smile or shrug, acknowledging that we're all here together.

Any advice that you’d like to share with our community?

Reach out to your friends, don't let negative spaces linger, support those in need as best you can, and think twice, it's alright.

***

Edmund Berrigan is the author of two books of poetry, Disarming Matter (Owl Press, 1999) and Glad Stone Children (Farfalla, 2008), and a memoir, Can It! (Letter Machine Editions, 2013). He is editor of The Selected Poems of Steve Carey (Sub Press, 2009), and is co-editor with Anselm Berrigan and Alice Notley of The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan (University of California, 2005) and The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan (University of California, 2010). He records and performs music as I Feel Tractor, and lives in Brooklyn. Berrigan’s latest collection of poetry, More Gone, is part of City Lights’s Spotlight series.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Centre for Poetry and Poetics Presents: A Reading with Alice NotleyPlease register for this event on: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/208112479027Alice Notley was born in Bisbee, Arizona, on November 8, 1945, and grew up in Needles, California, in the Mohave Desert. She was educated in the Needles public schools, at Barnard College, and at The Writers Workshop, University of Iowa. During the late 60s and early 70s she lived a traveling poet’s life (San Francisco, Bolinas, London, Wivenhoe, Chicago) before settling on New York’s Lower East Side. For sixteen years there, she was an important force in the eclectic second generation of the so-called New York School of poetry. In 1992 she moved to Paris, France and has remained there ever since, generally practicing no profession except for the writing, publication, and performing of her work, and the teaching of an occasional workshop. Notley is the author of more than thirty books of poetry including At Night the States, the double volume Close to Me and Closer . . . (The Language of Heaven) and Désamère, and How Spring Comes, which was a co-winner of the San Francisco Poetry Award. Her epic poem The Descent of Alette was published by Penguin in 1996, followed by Mysteries of Small Houses (1998), which was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize and the winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poetry. Notley’s long poem Disobedience won the Griffin International Prize in 2002. In 2005 the University of Michigan Press published a book of essays on poetry, Coming After. Notley edited The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan (University of California Press), with her sons Anselm and Edmund Berrigan as co-editors. The three of them edited as wellThe Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan. Notley has also edited two volumes of poetry by the British poet Douglas Oliver. Her most recent books are Certain Magical Acts, Benediction, Songs and Stories of the Ghouls, and Grave of Light: New and Selected Poems, winner of the Academy of American Poets’ Lenore Marshall Award. Notley has edited or co-edited three poetry journals over the years: CHICAGO, SCARLET, and Gare du Nord. She is also a collagist and cover artist. In 2015 she was awarded the Ruth Lilly Prize, for lifetime achievement in poetry.

0 notes