#the Duke of St Albans

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Quote

Though Margaret may well have regarded the duke of York with wariness from 1453 if not before, she acquiesced to his first protectorate, instead of the regency she had desired, without overt hostility. The first battle of St Albans in 1455 and York's second protectorate changed that. Having pushed for his ouster, she soon sought expanded public power for herself again, though this time through the more traditional and informal avenues of influence to which she already had access as queen. Nevertheless, through the next couple of years it appears that she was content to pursue a policy that combined control with limited conciliation and that stopped well short of seeking anyone's destruction. Though the picture becomes very murky as the situation deteriorated to the outbreak of civil war, by which time Margaret had become an uncompromising partisan, it is clear that she came to this posture rather late. Nor does she appear as the vengeful she-wolf until nearly the end of the reign, when the circumstances of a Yorkist military victory and settlement of the crown had made her one.

Helen Maurer, Margaret of Anjou: Queenship and Power in Late Medieval England (Boydell Press, 2003)

#margaret of anjou#richard duke of york#the first battle of st albans#wars of the roses#gender#queenship#reputation and representation#historian: helen maurer

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dragon has Three Heads or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Believe That Young Griff is the Real Deal

Before going any further, I want to warn anyone reading this analysis that it will contain spoilers for A Dance With Dragons, so proceed at your own risk.

This essay came about from an 'epiphany' I had while reading ADWD on break at work, specifically chapter Daenerys VII. In this chapter, Quentyn Martell and his companions present themselves to Daenerys and offer her a marriage alliance with Dorne. This being the day of her wedding to Hizdahr zo Loraq, Dany refuses and makes note mentally of Quaithe's earlier warning about not trusting "the Sun's Son." The identification seems simple enough, with House Martell's sigil featuring the sun and Quentyn being the son of Doran Martell, Prince of Dorne, but there are serious problems with this conclusion.

The issue with labeling Quentyn Martell the Sun's Son stems from how Dany reaches this conclusion; for starters, this is the original quote given by Quaithe in Daenerys II:

"No. Hear me, Daenerys Targaryen. The glass candles are burning. Soon comes the pale mare, and after her the others. Kraken and dark flame, lion and griffin, the sun's son and the mummer's dragon. Trust none of them. Remember the Undying. Beware the perfumed seneschal."

And this is how Dany identifies Quentyn as the Sun's Son in Daenerys VII and VIII:

Something tickled at her memory. "Ser Barristan, what are the arms of House Martell?"

"A sun in splendor, transfixed by a spear."

The sun's son. A shiver went through her. "Shadows and whispers." What else had Quaithe said? The pale mare and the sun's son. There was a lion in it too, and a dragon. Or am I the dragon? "Beware the perfumed seneschal." That she remembered. "Dreams and prophecies. Why must they always be in riddles? I hate this. Oh, leave me, ser. Tomorrow is my wedding day."

...

The pale mare. Daenerys sighed. Quaithe warned me of the pale mare's coming. She told me of the Dornish prince as well, the sun's son. She told me much and more, but all in riddles.

George has talked about the fickle nature of prophecy in the books and publicly, citing the Duke of Somerset's death at the Battle of St. Albans in Shakespeare's Henry VI as an example of why the literal or easiest interpretations are not always the most reliable. While Dany's conclusion that Quentyn is the 'Sun's Son' seems straightforward, she bases it solely on Barristan's description of the Martell arms. Her reasoning is mainly to justify marrying Hizdahr by dismissing the Martell offer, as Dany herself barely remembers Quaithe's warning and bemoans her 'riddles'.

Assuming that the 'Pale Mare' refers to the 'bloody flux' that the Astapori refugees bring to Meereen, and that the Kraken, dark flame, lion, griffon and mummer's dragon refer to Victarion Greyjoy, Moqorro, Tyrion, Connington and Young Griff respectively, the sequence of Quaithe's warning makes no sense with Quentyn as the 'Sun's Son.' At the end of ADWD, Tyrion is outside the walls of Meereen while Victarion and Moqorro are en route with the Iron Fleet, and Connington and Young Griff are in Westeros. If Dany's return to Meereen from the Dothraki Sea is followed by her journeying westwards, then this sequence makes sense. Victarion will likely destroy the Slaver's fleets and is seeking Dany's hand in marriage, while Moqorro is with him for the purpose of acknowledging her as Azor Ahai and encouraging her to free the slaves of Volantis. Given Tyrion's association with Varys, Illyrio, Jorah and now 'Brown Ben Plumm,' and his family's role in Robert's rebellion, it makes sense that he would not immediately seek out Daenerys on her return to Meereen. Connington and Young Griff await her in Westeros, but Quentyn as the 'Sun's Son' precedes all of them, breaking Quaithe's otherwise sensible sequence. If Quentyn were the 'Sun's Son' he could just as easily have been paired with the Kraken, since both are sent by the heads of their houses to offer her an alliance, while Tyrion and Moqorro travel together on the Selaesori Qhoran (the 'Perfumed Seneschal') and Connington and Griff are in league with Varys.

The far greater issue with Dany's interpretation is that we have access to Quentyn's POV, and there is nothing to suggest that he seeks to betray Daenerys. His purpose was to approach Dany with a marriage alliance, to assist her in reclaiming her crown; his party was even sent by Tatters to scope out the situation in Meereen for a possible double-crossing of the Yunkai'i, specifically to aid Dany. The only thing close to untoward that he does is attempt to claim one of her Dragons, and this was a desperation move driven by his insecurities and his fear of returning to his father empty handed, which would mean that his fallen companions died for nothing:

"What name do you think they will give me, should I return to Dorne without Daenerys?" Prince Quentyn asked. "Quentyn the Cautious? Quentyn the Craven? Quentyn the Quail?" (The Discarded Knight, ADWD)

Volantis, Quentyn thought. Then Lys, then home. Back the way I came, empty-handed. Three brave men dead, for what?

...

His father would speak no word of rebuke, Quentyn knew, but the disappointment would be there in his eyes. His sister would be scornful, the Sand Snakes would mock him with smiles sharp as swords, and Lord Yronwood, his second father, who had sent his own son along to keep him safe … (The Spurned Suitor, ADWD)

Disqualifying Quentyn as the Sun's Son leaves us with only three options, of which only one really works. Trystane is the only other son of House Martell aside from Quentyn via Prince Doran, and given his limited roll in the story thus far I think it's safe to cross him off the list. Doran could theoretically work as the 'Sun's son,' as his mother was Princess of Dorne before him; given that Quaithe describes the figures as going to Dany, Doran's limited mobility and poor health would disqualify him. This leaves us with only one 'son of a sun,' that being 'Young Griff,' aka Aegon VI Targaryen, the son of Rhaegar Targaryen and Elia Martell, Princess of Dorne.

This association of Aegon with the Martells via his mother fits with the copious amounts of imagery linking him to the Rhoynar and to 'Egg' aka Aegon V of "Dunk and Egg" fame, specifically that character's travels in Dorne. Tyrion finds him living on a pole boat in the Rhoyne River, home of the ancient Rhoynar culture that Dorne descends from. The Shy Maid is operated by Yandry and Ysilla, so-called 'orphans of the Greenblood' which are another allusion to Dunk and Egg's travels on the Greenblood River in Dorne:

A poleboat had taken them down the Greenblood to the Planky Town, where they took passage for Oldtown on the galleas White Lady.

...

When they’d been poling down the Greenblood, the orphan girls had made a game of rubbing Egg’s shaven head for luck. (The Sworn Sword)

In Tyrion IV of ADWD, a massive horned turtle appears in the river by the Shy Maid, an obvious reference to the Rhoynish 'Old Man of the River,':

It was another turtle, a horned turtle of enormous size, its dark green shell mottled with brown and overgrown with water moss and crusty black river molluscs. It raised its head and bellowed, a deep-throated thrumming roar louder than any warhorn that Tyrion had ever heard. “We are blessed,” Ysilla was crying loudly, as tears streamed down her face. “We are blessed, we are blessed.”

Duck was hooting, and Young Griff too. Haldon came out on deck to learn the cause of the commotion . . . but too late. The giant turtle had vanished below the water once again. “What was the cause of all that noise?” the Halfmaester asked.

“A turtle,” said Tyrion. “A turtle bigger than this boat.”

“It was him,” cried Yandry. “The Old Man of the River.”

And why not? Tyrion grinned. Gods and wonders always appear, to attend the birth of kings.

When Tyrion and Haldon visit the Painted Turtle inn to find information about Daenerys' whereabouts, we have an interesting description of the inn from Tyrion:

The ridged shell of some immense turtle hung above its door, painted in garish colors. Inside a hundred dim red candles burned like distant stars. (Tyrion VI, ADWD)

We once more have Rhoynish symbolism in the turtle, while the 'garish colors' are reminiscent of Young Griff's hair, which is dyed blue in the Tyroshi fashion. Tyrion's description of inside the 'Painted Turtle' is one of dim red candles burning like stars, which can be seen as an oblique reference to the red rubies on Rhaegar's black breastplate, thereby associating the red of Targaryen heraldry with the cultural symbols of the Rhoynar.

The 'Dunk and Egg' imagery goes further, with both Egg and Aegon wearing distinctive straw sun hats, and being accompanied by their Hedge Knights from the Stormlands, both of whom have titles derived from their own simplistic personalities (Duncan the Tall, Rolly Duckfield). Moreover, Egg's journeying to Dorne ends up giving him refuge from the Spring Sickness that ravages Westeros, while Aegon's time in Essos serves as a refuge from Robert's spies and the chaos of the War of the Five Kings. While these similarities might be viewed as a doomed attempt by Varys to recreate Egg through Aegon, I think the purpose of these parallels is to establish both princes as following similar trajectories: both are sons of a Targaryen prince (Maekar, Rhaegar) and a Dornish noblewoman (Dyana Dayne, Elia Martell); become King of the Seven Kingdoms through unexpected circumstances: and if George plans to end ADOS with a mini-Dance of the Dragons, I would expect Aegon VI to meet a fiery end like Egg did.

If Young Griff is actually Aegon VI Targaryen as well as the 'Sun's Son,' this leaves the 'mummer's dragon' without any clear identity. Part of this is due to the conviction that Dany's identification of the cloth dragon from the undying visions with a 'mummer's dragon' or puppet dragon must be correct. In truth, there are countless cases from ADWD alone that show us that a mummer's object is not necessarily a puppet, but more broadly means something which is not as it appears:

I know one stands before me now, weeping mummer's tears. The realization made her sad. (Daenerys III, ADWD)

"Not here," warned Gerris, with a mummer's empty smile. "We'll speak of this tonight, when we make camp." (The Windblown, ADWD)

"My lord, I bear you no ill will. The rancor I showed you in the Merman's Court was a mummer's farce put on to please our friends of Frey."

...

I drink with Jared, jape with Symond, promise Rhaegar the hand of my own beloved granddaughter … but never think that means I have forgotten. The north remembers, Lord Davos. The north remembers, and the mummer's farce is almost done. My son is home." (Davos IV, ADWD)

His reign as prince of Winterfell had been a brief one. He had played his part in the mummer's show, giving the feigned Arya to be wed, and now he was of no further use to Roose Bolton. (The Turncloak, ADWD)

Fat Wyman Manderly, Whoresbane Umber, the men of House Hornwood and House Tallhart, the Lockes and Flints and Ryswells, all of them were northmen, sworn to House Stark for generations beyond count. It was the girl who held them here, Lord Eddard's blood, but the girl was just a mummer's ploy, a lamb in a direwolf's skin. So why not send the northmen forth to battle Stannis before the farce unraveled? (A Ghost in Winterfell, ADWD)

Mummer's tears and smiles are obviously false emotions, being affectations put on to hide what someone truly feels. Wyman Manderly is engaged in a mummer's farce wherein he pretends to be loyal to King Tommen and Roose Bolton, but in truth is scheming to restore the Starks to Winterfell and assist Stannis against the Boltons. Roose Bolton, Petyr Baelish and the Crown have in turn engaged in their own mummer's farce by sending Jeyne Poole north to wed Ramsay Snow in the guise of Arya Stark, "a lamb in direwolf's skin." If the 'mummer's dragon' is in fact a dragon that has been made to appear as something else, then Jon Snow more than fits this bill. By birth he should be a Targaryen, having been fathered by Rhaegar Targaryen upon Lyanna Stark; instead, his fortuitous Stark features inherited from his mother, and Ned's claiming Jon as his bastard and raising him amongst his children at Winterfell, has allowed Jon to hide in plain sight from those who would kill him for being Rhaegar's son.

The significance of Dany, Jon and Aegon being the three heads of the dragon is due to their mirroring a less conspicuous triad in George's World: elemental magic and it's connections to the Long Night. We are aware of three forms of elemental magic in the story, being pyromancy, cryomancy and hydromancy. Pyromancy is the most obvious, being the control and use of fire as we see with followers of Rhllor, and also tied to dragons. Cryomancy or ice magic appears in the powers of the Others and in the Wall separating the Seven Kingdoms from the lands beyond. Finally we have hydromancy or water magic, which was used by the Rhoynar against the Valyrian Freedhold and by Nymeria's Rhoynar settlers to support their communities within the deserts of Dorne. Company of the Cat has an excellent video discussing these three 'schools' of magic, but to summarize what she's said: Blue, Red and Green are the colours commonly associated with Ice, Fire and Water/the Sea in ASOIAF; in addition to being featured on the arms of ancient houses such as Massey and Strong, these elements are in turn associated with three magical items in the books. The first, The Horn of Joramun, can raise and lower The Wall (Ice); Dragonbinder, a horn that was likely used alongside similar horns to control the volcanoes of the fourteen flames in Valyria (Fire); and the 'Kraken summoning horn' which is most likely the Hammer of the Waters, since the Hammer raised the seas to swamp the 'Arm of Dorne,' which would have filled the seas fill with corpses of the dead and 'summoned' krakens, which would have fed on the bodies of the drowned.

The Valyrian, Northern and Rhoynish heritage of Dany, Jon and Aegon ties them to these three forms of magic respectively, and by extension to the Long Night. We are given three accounts of the Long Night between ASOIAF and TWOIAF, which I dub the 'western,' 'far eastern' and 'near eastern' versions. The 'western' account concerns the First Men, the Night's Watch, the Last Hero and the Others; the 'far eastern' account covers the 'Jade Compendium' and the Yi Tish account of the Blood Betrayal; and the 'near eastern' or Rhoynar account in which the children of Mother Rhoyne sang a song to return light to the world. Aegon is tied to the Rhoynish account through his mother's heritage, with references to the Rhoynish account in the 'Old Man of the River' appearing in ADWD and Dany's vision of Rhaegar talking about Aegon's 'Song' (that of Ice and Fire):

The Rhoynar tell of a darkness that made the Rhoyne of Essos dwindle and disappear, her waters frozen as far south as the joining of the Selhoru, until a hero convinced the many children of Mother Rhoyne, such as the Crab King and the Old man of the River, to put aside their bickering and join in a secret song that brought back the day. (TWOIAF: Ancient History: The Long Night)

...

“Will you make a song for him?” the woman asked.

“He has a song,” the man replied. “He is the prince that was promised, and his is the song of ice and fire.” (Daenerys IV, ACOK)

Jon's connection to the Northern account is obvious given his Stark lineage and service in the Night's Watch, as well as his dreams in ADWD:

Burning shafts hissed upward, trailing tongues of fire. Scarecrow brothers tumbled down, black cloaks ablaze. "Snow," an eagle cried, as foemen scuttled up the ice like spiders. Jon was armored in black ice, but his blade burned red in his fist. As the dead men reached the top of the Wall he sent them down to die again. He slew a greybeard and a beardless boy, a giant, a gaunt man with filed teeth, a girl with thick red hair. Too late he recognized Ygritte. She was gone as quick as she'd appeared.

The world dissolved into a red mist. Jon stabbed and slashed and cut. He hacked down Donal Noye and gutted Deaf Dick Follard. Qhorin Halfhand stumbled to his knees, trying in vain to staunch the flow of blood from his neck. "I am the Lord of Winterfell," Jon screamed. It was Robb before him now, his hair wet with melting snow. Longclaw took his head off. Then a gnarled hand seized Jon roughly by the shoulder. He whirled … (Jon XII, ADWD)

Finally, Dany is directly referred to as Azor Ahai in the books while her visions from Daenerys IX of AGOT connect her bloodline to the Great Empire of the Dawn. The eye colours of the figures she sees match the titles of four of the eight emperors of the GEOTD, Opal, Jade, Tourmaline and Amethyst, with the Bloodstone Emperor killing his sister the Amethyst Empress and causing the Long Night. Azor Ahai and the Bloodstone Emperor are themselves connected, and I recommend David Lightbringer's Nightbringer series and "Azor Ahai the Bad Guy" video for a concise explanation. It's worth noting that David is well within the Faegon Blackfyre camp, but I think his theories here more than fit my own conclusions also.

Aegon being one of the three heads also fits in with the symbolic relationship between water, fire and ice and the green, red and blue colour scheme. As Company of the Cat points out in her video about the magic horns (timestamp 26:52), green is a secondary colour made from a 'cool' and a 'warm' colour, placing it in the middle of the spectrum while red and blue are polar opposites. Similarly, fire can melt ice back into water and water in turn quenches fire, situating Aegon at a middle ground between Jon's ice and Dany's fire. Whereas Jon's only aspect of himself that ties him to House Targaryen is his father and otherwise he is firmly associated with his mother's house, Dany is tied symbolically to her Targaryen identity in the books, being a product of Targaryen incest, the first to hatch dragons in over a century, and her ties to fire through her 'rebirth' on Mirri's pyre under the Red Comet. While Aegon's physical appearance and his father tie him clearly to House Targaryen like Dany, the support of his mother's family alongside his Rhoynar lineage and symbolism place him in a similar situation to Jon, besides their being half-brothers. This also calls to mind the three accounts of the Long Night: if Jon is the Last Hero leading the Night's Watch and Dany is Azor Ahai driving out the darkness with her 'lightbringer' (ie her dragons), Aegon is the unnamed hero who rallied the children of Mother Rhoyne to sing a secret song which brought back the day. To quote alexis_something_rose's essay about Young Griff, "I can wager who will be bickering and who will tell them to set their differences aside and join together in a secret song that will bring back the day."

Whether or not all three or some combination of them will play a decisive role in defeating the Others, or if that will be Bran's part to play, I believe strongly that Dany, Jon and Aegon will be the 'three heads of the dragon.' If 'Young Griff' is truly Sun's Son, Aegon son of Rhaegar, his joining with Dany and Jon represents a unification of the three Dawn Age narratives of the Long Night and it's eventual end. Uniting the icey North, the dragon lord's fire and the songs of Mother Rhoyne would make the endgame a true 'Song of Ice and Fire.'

#aegon vi targaryen#young griff#faegon#jon snow#daenerys targaryen#elia martell#quentyn martell#lyanna stark#rhaegar targaryen#asoiaf#asoiaf spoilers#asoiaf speculation#dorne#rhoynar#azor ahai#george rr martin#house martell

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

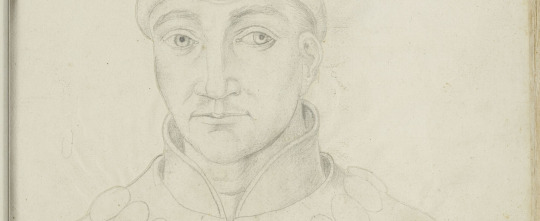

1690s or ab. 1670 British (English) School or attr. to Peter Lely - Portrait of a Man (thought to be Charles Beauclerk, 1st Duke of St Albans)

(St Albans Museum + Gallery)

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady Moyra de Vere Cavendish (née Beauclerk), 27 July 1898

Lady Moyra was the third daughter of the 10th Duke of St. Albans. She married Richard Cavendish in 1895. She lived from 1876-1942.

via the lafayette negative archive

#old photo#old photography#old photograph#victorian photograph#victorian photography#19th century#19th century photography#antique photo#antique photograph#antique photography#edwardian era#victorian era#1890s#british aristocracy#aristocracy#e

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

… Eleanor Cobham was a respectable lady who might expect to become a member of the household of a royal woman or member of the upper nobility, before being married and gaining a household of her own. Eleanor’s upbringing was likely to be typical of a woman of her class. She would not have had an exemplary education like Joan of Navarre did, but she does seem to have been taught to read in English, and she may even have learnt to write. Her education would have only been to a level that she would then be capable of running a knightly household and estate once married. The rest of her upbringing would have been focused on feminine values to help attract and keep her a husband, such as singing, dancing, music and needlework. No known physical description of Eleanor exists, and only one contemporary picture of her survives. This is an illuminated miniature from 1431 of Eleanor with her future husband, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, from the Liber Benefactorum of St Albans by Thomas Walsingham. Eleanor and Humphrey were benefactors of the Abbey of St Albans, shown in Humphrey’s hand in the picture, but little of Eleanor’s real physical attributes can be garnered from the picture, it being a typically stylised miniature of the time. Eleanor is shown with a high forehead, the popular style, but her hair is hidden under a covering, so the colour is left a mystery. She is shown as slim and tall, but whether this mirrored her real stature cannot be known for certain. She is wearing a sumptuous red dress with a golden belt, a black head covering with a golden circlet, and a thick golden necklace, representing the wealth of her station as Duchess of Gloucester. While there is no surviving physical description of Eleanor, it is reasonable to assume that she was an attractive woman. Jehan de Waurin, a Burgundian chronicler and contemporary of Eleanor, describes her as ‘a very noble lady of great descent … also she was beautiful and marvellously kind [pleasant]’. As she was later to attract the attention of a prince, it is likely that she was at least fairly attractive, and probably had sufficient wit and charm to go with it.

Gemma Hollman, "Royal Witches: Witchcraft and the Nobility in Fifteenth Century England"

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

1455 05 22 Saint Albans - Graham Turner

On the 22nd May 1455, the struggle for control of the government of England boiled over into armed conflict in the first battle of what would become known as the Wars of the Roses. The following thirty years would see the throne itself become the prize for the rival Royal houses of Lancaster and York.When King Henry VI regained his sanity in January 1455, the Duke of York`s brief protectorate came to an end and his chief rival, the Duke of Somerset, regained his position of influence at court.York withdrew to the north and began mustering men, supported by his brother in law, the Earl of Salisbury, and Salisbury`s son, Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick, later known as the `Kingmaker`.Advancing towards London, the Yorkist force found the Royal army positioned in the small town of St. Albans. When negotiations for the Duke of Somerset's surrender broke down, York`s men stormed the town`s defences while Warwick broke into the market place through alleys and gardens, attacking the Lancastrian centre.Graham Turner`s painting dramatically recreates the scene as Warwick's men, wearing their red liveries and badges of the Bear and Ragged Staff, advance through the medieval market place, while the 'Kingmaker', in the latest Milanese armour, raises his visor to greet the Duke of York. York, with his Standard bearer beside him, is indicating in the direction of the Castle Inn, site of Somerset`s last stand, and the Abbey towers over the proceedings as it still does today.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ELIZABETH OF YORK, THE WHITE ROSE

The eldest child of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, Elizabeth of York was born at Westminster on 11th February, 1466. She was christened by George Neville, Archbishop of York and her godparents were Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, Cecily Neville, Dowager Duchess of York and Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford. Elizabeth’s parents had married secretly at Grafton Manor, soon after her father’s accession to the throne. Her mother, Elizabeth Woodville was the daughter of Sir Richard Woodville, (later created Earl Rivers) and Jacquetta of Luxemburg, the widow of John, Duke of Bedford (the brother of Henry V). Edward IV had met Elizabeth’s mother, the widow of Sir John Grey, a Lancastrian knight who was killed at St. Albans in 1461, when she came to petition him for the return of her husband’s estates. Edward had wanted to make her his mistress, but she held out for marriage. Following the death of her father and the usurpation of Richard III, Elizabeth and her siblings, including Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, the so-called Princes in the Tower, was declared illegitimate by the Act of Titulus Regius. Her young brothers disappeared inside the Tower of London amidst rumours that they had been murdered. How Elizabeth herself reacted to their demise has gone unrecorded, but she had at the time taken sanctuary with her mother at Westminster Abbey. Rumour suggested that Richard III was planning to marry her himself. Her mother, in secret correspondence with Margaret Beaufort, agreed to the marriage of Elizabeth and Margaret’s son, Richard’s rival and the exiled heir to the House of Lancaster, Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, who took a public oath to marry Elizabeth should he became King of England. Richmond became King Henry VII after his victory over Richard III at Bosworth Field and the Princess was brought back to London from Sheriff Hutton Castle in Yorkshire. Henry was crowned at Westminster alone on 30th October, to underline that he ruled in his own right. Parliament petitioned the king to honour his promise to marry the Yorkist heiress and the marriage of Elizabeth of York and Henry VII was finally celebrated on 18th January 1486 at Westminster Abbey. As the eldest daughter of King Edward IV with no surviving brothers, Elizabeth of York had a strong claim to the throne in her own right, but she did not rule as queen regnant. The rule of a queen regnant would not be accepted in England for another sixty-seven year until the ascension of Elizabeth’s granddaughter, Mary I. Nine months later, the new Queen was delivered of a son. He was given the symbolic name of Arthur, in honour of the legendary Dark Age British King. Elizabeth was finally crowned Queen Consort on 25 November 1487. Elizabeth was tall, fair haired, attractive and gentle in natured. Despite being a political arrangement, the marriage proved successful and both partners appear to have genuinely cared for each other. Elizabeth was generous to her relations, servants and benefactors, and she enjoyed music and dancing, as well as dicing. The Queen’s household was ruled byLady Margaret Beaufort. The Queen’s own mother, the meddlesome and grasping Elizabeth Woodville, suspected of involvement in Yorkist plots, was shut up in a nunnery and stripped of all her belongings. The marriage of Elizabeth of York and Henry VII was to produce seven children, of which only four survived the perils of infancy in Tudor times. One of these was the future Henry VIII. Elizabeth of York died tragically on her 37th birthday, after a long and difficult labor that produced a baby girl, Katherine, who also perished. According to records, in addition to the entire kingdom and the royal court, the king fell into deep mourning, and became more reclusive, avoinding public appearances. Elizabeth was buried at Westminster Abbey, within an magnificent effigy created by the Renaissance sculptor Pietro Torrigiano. Henry VII would be buried at her side, only six years later.

#elizabeth of york#queens#kings#henry vii of england#english history#tudor period#tudor dynasty#historicalwomen#history

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

On May 21st 1424 James I was eventually crowned King at Moot Hill, Scone.I

say eventually because by time his father Robert III died, James was a prisoner of the English, his Uncle, The Duke of Albany quite liked being the ruler, in all but name and was in no hurry to even negotiate to bring his nephew home, and so it took 18 years for his coronation to take place.

James had scores to settle, and here is a wee rundown of the events on and around this day back then.

The 21 of Maij, 1424, K. James the First, with his Queine, Jeane, wer solemly crouned at Scone.

The 26 of this same mounthe, K. James the 1. called a parliament of his estaits at Perth; and one the 9 day of the said parliament, he caussed arrest Murdack, Duck of Albaney, Earle of Fyffe and Menteith, with his 2d sone, Sr Alexander Steuarte, quhom he had knighted the day of his coronatione at Scone, and with them 26 others, viz.

Archbald, Earle of Douglas,

Will: Douglas, Earle of Angus,

George Dumbar, Earle of Marche,

Sr Adam Hepburne of Hailles,

Sr Thomas Hay of Zester,

Valter Halyburtone,

Valter Ogluey,

Dauid Steuarte of Rassythe,

Alex: Settone of Gordon,

Will: Erskyne of Kinoule,

Alex: Earle of Craufurd,

Patrick Ogiluey of Ochterhousse,

Jhone Steuarte of Dundonald,

Dauid Murray of Gaske,

Jo: Steuarte of Cardine,

William, Lord Hay, Grate Constable,

Jo: Scrymgeour of Didope,

Alex: Irwin of Drum,

Herbert Maxwoll of Carlauerock,

Herbert Harries of Terregils,

Androw Gray of Fouills,

Robert Cuninghame of Kilmuers,

Will: Crighton of the same,

Alex: Ramsay of Dalhousey.

This same day he arrest, lykwayes, Sr Johne Montgomerey of the same, and Allane Otterburne, secretarey to the Duck of Albaney; and they too wer releassed within three dayes.

This same zeire, James Steuarte, the Duck of Albaneys youngest sone, quho had escaped the Kings hands wnpprehendit, raisses such forces as he could, burns the toune of Dunbritton, kills Johne Steuarte, (called the Read) of Dundonald, and 32 more, and then, with his fathers old secretarey, Finlaw, Bis: of Argyle, fleis to Irland.

And the following year…..

This zeire, 1425, the Lordes of Montgomery and Kilauers, with Sr Humfrey Cuninghame, are sent by the King with ane armey to beseidge the castell of Kilmauerrin, now Loche Lomond, keipt aganist authority by the partey of James Steuarte, the youngest sone of Murdack, Duck of Albaney.

Justice seems to have been quite slow back then, two years on from his coronation we have…….

The 18 day of Maij, this zeire, 1426, the King adiorned his parliament to Streueling from Perth, till the 24 day of the said mounthe; befor quhom wes accussid Walter Steuart, eldest sone to Murdack, Duck of Albaney, quho receuid sentence of death, and lost his head this same day, befor the castell one a litell rocke; and one the morrow, lykwayes, Murdack, Duck of Albane, with his 2d sone, Alexander Steuarte, and hes father in law, Duncane, Earle of Lennox, being accusid, wer all 4 forfaulted, and condemned to losse ther heades, by an assise of ther peirs. The assierrs wer:-

Walter, Earle of Athole,

Archbald, 3d of that name, E. of Douglas,

Alex: Earle of Ross, Lord of the Iles,

Alex: Steuarte, Earle of Mar,

Will: Douglas, Earle of Angus,

Will: St. Clair, Earle of Orknay,

George Dumbar, Earle of Marche,

James Douglas, Lord Balueney,

Gilbert Hay, Lord of Erole, Grate Constable,

Robert Steuarte, Lord Lorne,

Sr Jo: Montgomerey of the same,

Sr Thomas Somerwaill of the same,

Sr Herbert Harries of Terregills,

James Douglas, L. Dalkeith,

Robert Cuninghame, L. Kilmauers,

Sr Alex: Leuingston of Calender,

Sr Thomas Hay of Locharret,

Sr Will: Borthwick of the same,

Sr Patrick Ogiluey, Shriffe of Angus,

Sr Jo: Forrester of Corstorphin,

Sr Walter Ogiluey of Lintrathen.

By thir assisers they wer forfaulted, and sentenced to losse ther heads; wiche was put to executione one a litle rocke be east Streuelin castle, this same monithe. After wich forfaultrey, the King seassed ther haill estaits in his hands, and caussed, in this same parliament, annex the earledome of Fyffe to the croune.

With all these executions James made enemies and had a busy time quelling rebellions throughout the rest of his reign until……

One the 21 day of Februarij, in the zeire 1437, was the noble King James the 1. killed at the abbey of the Dominicans, in the toune of Perth, by Robert Steuarte and Robert Grhame, at the instigatione of Walter Steuarte, Earle of Athole, his wnckell, in the 13 zeire of his rainge. His corpes wer solemly interrid in a magnificent monument erected by himselue, (quhill he liued,) in his lait foundit monastarey of the Carthusians, in the subvrbs of Perth.

This zeire are the parrcidall traitourts led lyke doges, in halters, to Edinbrughe, quher Walter, Earle of Athole, the cheiffe actor of this woefull tragidey, was tortured one ane ingyne made for the purpois; and with a croune of hote burning irone, was crouned at the crosse of Edinbrugh; and therafter his heart was pulled out of his breast, and rost in a fyre befor his eyes, by the executioner, then cast to the doges to eat; then was his head cutt offe, and hes bodey dewydit in 4 quarters, and sent to the 4 quarters of the realme, and ther hunge vpe one irone gibetts.

Robert Steuart was riuen assunder betuix four horses, and his head sent to Perth, and fixed one ane iron pin aboue the toune gail.

Robert Grhame was tayed with ropes in a cairte, quherin wes a heigh loge of wood, quherone wes nailled that hand that strake the King, with a naile of burning hote iron; the quhole musckells of hes bodey being cut in longe slitts, was fristed with flaming hote irone pincetts, by tuo executioners; and after the lyffe was quyte out of him, his bodey was dewydit in 4 quarters, and erected one gibetts at the end of the 4 most publick wayes of the kingdome; and his head was sett ouer the west port of Edinbrugh.

So although his reign is officially just short of 31 years he actually ruled for around 13 years before his murder, he was 42 years old.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Douai Martyrs is a name applied by the Catholic Church to 158 Catholic priests trained in the English College at Douai, France, who were executed by the English state between 1577 and 1680.[2]

History

Having completed their training at Douai, many returned to England and Wales with the intent to minister to the Catholic population. Under the Jesuits, etc. Act 1584 the presence of a priest within the realm was considered high treason. Missionaries from Douai were looked upon as a papal agents intent on overthrowing the queen. Many were arrested under charges of treason and conspiracy, resulting in torture and execution. In total, 158 members of Douai College were martyred between the years 1577 and 1680.[1] The first was Cuthbert Mayne, executed at Launceston, Cornwall on the 29 November 1577. [3] The last was Thomas Thwing, hanged, drawn, and quartered at York in October 1680.[4] Each time the news of another execution reached the College, a Solemn Mass of thanksgiving was sung.

Many people risked their lives during this period by assisting them, which was also prohibited under the Act. A number of the "seminary priests" from Douai were executed at a three-sided gallows at Tyburn near the present-day Marble Arch. A plaque to the "Catholic martyrs" executed at Tyburn in the period 1535 - 1681 is located at 8 Hyde Park Place, the site of Tyburn convent.[5]

They were beatified between 1886, 1929 and 1987, and only 20 were canonized in 1970. Today, British Catholic dioceses celebrate their feast day on 29 October.[1]

Bl Alexander Crow

Bl Anthony Middleton

Bl Antony Page

Bl Christopher Bales

Bl Christopher Buxton

Bl Christopher Robinson

Bl Christopher Wharton

Bl Edmund Catherick

Bl Edmund Duke

Bl Edmund Sykes

Bl Edward Bamber

Bl Edward Burden

Bl Edward James

Bl Edward Jones

Bl Edward Osbaldeston

Bl Edward Stransham

Bl Edward Thwing

Bl Edward Waterson

Bl Everald Hanse

Bl Francis Ingleby

Bl Francis Page

Bl George Beesley

Bl George Gervase

Bl George Haydock

Bl George Napper

Bl George Nichols

Bl Henry Heath

Bl Hugh Green

Bl Hugh More

Bl Hugh Taylor

Bl James Claxton

Bl James Fenn

Bl James Thompson

Bl John Adams

Bl John Amias

Bl John Bodey

Bl John Cornelius

Bl John Duckett

Bl John Hambley

Bl John Hogg

Bl John Ingram

Bl John Lockwood

Bl John Lowe

Bl John Munden

Bl John Nelson

Bl John Nutter

Bl John Pibush

Bl John Robinson

Bl John Sandys

Bl John Shert

Bl John Slade

Bl John Sugar

Bl John Thules

Bl Joseph Lambton

Bl Lawrence Richardson

Bl Mark Barkworth

Bl Matthew Flathers

Bl Montfort Scott

Bl Nicholas Garlick

Bl Nicholas Postgate

Bl Nicholas Woodfen

Bl Peter Snow

Bl Ralph Crockett

Bl Richard Hill

Bl Richard Holiday

Bl Richard Kirkman

Bl Richard Newport

Bl Richard Sergeant

Bl Richard Simpson

Bl Richard Thirkeld

Bl Richard Yaxley

Bl Robert Anderton

Bl Robert Dalby

Bl Robert Dibdale

Bl Robert Drury

Bl Robert Johnson

Bl Robert Ludlam

Bl Robert Nutter

Bl Robert Sutton

Bl Robert Thorpe

Bl Robert Wilcox

Bl Roger Cadwallador

Bl Roger Filcock

Bl Stephen Rowsham

Bl Thomas Alfield

Bl Thomas Atkinson

Bl Thomas Belson

Bl Thomas Cottam

Bl Thomas Maxfield

Bl Thomas Palaser

Bl Thomas Pilchard

Bl Thomas Pormort

Bl Thomas Reynolds

Bl Thomas Sherwood

Bl Thomas Somers

Bl Thomas Sprott

Bl Thomas Thwing

Bl Thomas Tunstal

Bl Thurstan Hunt

Bl William Andleby

Bl William Davies

Bl William Filby

Bl William Harrington

Bl William Hart

Bl William Hartley

Bl William Lacey

Bl William Marsden

Bl William Patenson

Bl William Southerne

Bl William Spenser

Bl William Thomson

Bl William Ward

Bl William Way

St Alban Bartholomew Roe

St Alexander Briant

St Ambrose Edward Barlow

St Cuthbert Mayne

St Edmund Arrowsmith

St Edmund Campion

St Edmund Gennings

St Eustace White

St Henry Morse

St Henry Walpole

St John Almond

St John Boste

St John Kemble

St John Payne

St John Southworth

St John Wall

St Luke Kirby

St Ralph Sherwin

St Robert Southwell

Ven Edward Morgan

Ven Thomas Tichborne

Bl Alexander Rawlins

Bl Edward Campion

Francis Dickinson

James Bird

James Harrison

John Finglow

John Goodman

John Hewitt

Matthias Harrison

Miles Gerard

St Polydore Plasden

Richard Horner

Robert Leigh

Robert Morton

Robert Watkinson

Roger Dickinson

Bl Thomas Felton

Bl Thomas Ford

Thomas Hemerford

Thomas Holford

William Dean

William Freeman

Bl William Gunter

Bl William Richardson

[+]

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw a post going around about Henry V's looks, so I wonder if you happen to know the hair colour of his siblings? I know the hair colours of some Plantaganets, but frankly I've never looked for those of Henry's siblings before.

Hello! So, there's really only information about what colour hair three of Henry V's five siblings had and only one case where I feel we can be 99.9% certain of the hair colouring.

I'll go into a lot more detail (with photos! and my trademark rambling!) below the cut but basically:

Thomas, Duke of Clarence: unknown

John, Duke of Bedford: dark brown

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester: probably dark brown

Blanche of England: possibly blonde or red

Philippa of England: unknown

John, Duke of Bedford's hair is depicted as brown in two extant manuscripts that belonged to him. Depictions in manuscripts are problematic as far as "true likenesses" go. The artist might not know what their subject look like so they cannot make a true-to-life likeness even if they wanted to. Or they might be making an idealised or generic portrait where what's important is more what the figure represents (i.e. status as king, queen, duke etc.) rather than what the figure really looked like.

But these two manuscripts depict John in what appears to be an effort to depict a reasonable likeness of him (you can tell by the nose). The Bedford Hours has the most detailed and fine portrait, where he has dark brown hair, an aquiline nose and it seems grey eyes (the weird five o'clock shadow around the side of his face and under his jaw is probably the result of pigment wearing off, though).

The portraits in the Salisbury Breviary are overall less detailed but are still personalised enough (see: the nose) that we can say that they were probably made to resemble him:

And if that's not enough, his remains were discovered in 1860 and his hair colour was noted as "dark" or "black". The remains themselves were noted as being blackened so I'd guess the processes of embalming/decay probably darkened his dark brown hair to black.

The flip side of the manuscript problem is Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, where we have four different depictions from four different contemporary/near-contemporary manuscripts, where his hair ranges from light brown (or dark blond, if you'd rather) to dark brown to black, including one where he looks bald but if you zoom in close enough, he has a very short crop of dark hair underneath his crown.

The first is from the Talbot-Shrewsbury Book (made in Rouen, 1444/5), the second from the presentation copy of John Capgrave's Commentary on Exodus (made in England, c. 1440); the third from the Psalter of Humfrey of Gloucester (made in England in the second quarter of the 15th century, before 1447) and the fourth from the St. Albans Benefactor Book (made in St Albans monastery, begun 1380 and finished c. 1540). All of these can be connected with people who knew Humphrey and thus knew what he looked like (though it's not clear when the fourth was made, it may have been long after his lifetime), though as with all manuscripts, he may have been represented as a generic royal duke/patron/donor instead of an attempt being made at a reasonable likeness.

What is striking about them is how different they are not only from the uniform likenesses of John but from each other. If second and third have the same type of hair colour, the faces are noticeably different. None of them resemble the copy of Humphrey's portrait that closely either (though, of course, a portrait has a lot more room for detail and personalisation).

However, the second and third are the most interesting in terms of hair colour because they both depict Humphrey with dark brown hair and were both made in Humphrey's lifetime by English illuminators - the third was almost certainly commissioned by Humphrey himself - so they have the best chance of being reasonably true to how he looked.

But in case that sounds too easy an answer, Humphrey's corpse was also rediscovered in the 1700s and his hair is said to have been yellow. Elizabeth, countess of Moira and a "proto-archaelogist", took some of the hair, noted the colour and that it was strong enough to be woven "Bath rings". She also suggested that the colour of the hair was not as it had been in life but it was "the nature of hair to gain that yellowish hue in the grave" - in other words, Humphrey may have been grey- or white-haired at death and the materials used in embalming bleached or discoloured his hair.

Although being the most obscure sibling, Blanche of England is the perhaps the only other sibling where there's any information about her hair colour. We have this image which I believe is a copy of a near-contemporary image of her (in the centre):

I can't remember or find where I got the information about it being a copy of a near-contemporary original, though, so I might be wrong. As we can see, she appears to have hair that is somewhere on the blond to red spectrum (I read it as ginger but though this is the highest resolution I can find, it's clearly poor quality (cf. the lines on the faces) so the colours might be distorted). The painting might represent Blanche as an idealised queenly figure rather than an attempt to represent her truthfully - though the fact it depicts her with a crown similar to the Palatine Crown she brought as her dowry is suggestive that they were trying to depict her in a way that made her easily identifiable.

Her name, "Blanche", might also be suggestive, as she was named after her grandmother, Blanche of Lancaster, Duchess of Lancaster (daughter of Henry of Grosmont, the first wife of John of Gaunt) whose hair was described by Chaucer as golden:

For every heer upon hir hede, Soth to seyn, hit was not rede, Ne nouther yelow, ne broun hit nas; Me thoghte, most lyk gold hit was. (The Book of the Duchess, ll. 855-858)

Of course, it's possible that Blanche was merely named in honour for her grandmother and there was no resemblance. But given Blanche means "white", it's possible that she was named in honour of her grandmother and because her hair was a similar colour.

I'm not aware of any contemporary surviving contemporary images of Philippa of England, though we have an image from 1590 that shows her with blonde (reddish-blonde?) hair and an stained glass window from the 19th century that shows her with dark hair:

We do have a near-contemporary image of Thomas, Duke of Clarence but... it's his alabaster tomb effigy and he's shown wearing a helm and is without moustache and beard so we have no idea of the colour of his hair.

But the Lancaster siblings probably every hair colour in their gene pool. Henry IV was said to have had "russet" hair when his tomb was opened (though we can't dismiss the possibility that his hair only appeared russet due to the way that red pigment can decay slower than others). Mary de Bohun is depicted as blonde in donor portraits in her psalter and Book of Hours (though it might be an idealised portrait than realistic). Their paternal grandmother, Blanche of Lancaster, was blond, their great-grandparents Philippa of Hainault and Edward III appear to have been black-haired and blonde respectively and red-hair is strongly associated with the Plantagenet line. So while Henry V, John and Humphrey all seeming to have dark brown hair is perhaps indicative of a family trait, I don't think that means Thomas, Blanche and Philippa must have had it too - and Blanche may well have been blonde or ginger.

#thomas duke of clarence#john duke of bedford#humphrey duke of gloucester#blanche of england#philippa of england#text posts#yoghurtbattle#asks#(as for the spouses margaret holland has blond hair in some manuscripts#catherine de valois's effigy had strands of brown hair#and there's a lock of blond hair said to be taken from jacqueline of hainault's tomb though they also said they couldn't find her tomb)#(no information about eleanor cobham or anne of burgundy or jacquetta of luxembourg i believe)#lancasterlings

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Prior to Henry's illness Margaret does not appear to have been anyone's avowed enemy. She was certainly not the enemy of Richard, duke of York, but was regarded by him and his wife as a potential intercessor in his behalf. whatever her private feelings may have been, she appears to have purposely cultivated an image of accessibility, in part through her gifts. Indeed, it appears that her first publicly political response to the crisis should be seen as an attempt to bridge differences rather than as partisan support of a particular faction. Moreover, the notion of faction itself must be questioned, for it grew out of circumstantial cooperation and temporary convenience and could at times be altered by changes in the wind. 'York' - identified as a firm alliance between the duke of York, the Neville earls of Salisbury and Warwick and their associates - appeared as a distinct faction around the time of the first battle of St Albans, while 'Lancaster' remained more amorphous, composed of persons who for one reason or another remained actively loyal to Henry, though only some of them bore specific grudges against York or the Nevilles. Without 'York' there was, in fact, no 'Lancaster'.

Helen Maurer, Margaret of Anjou: Queenship and Power in Late Medieval England (Boydell Press, 2003)

#margaret of anjou#henry vi#richard duke of york#wars of the roses#queenship#the first battle of st albans#historian: helen maurer

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coronation celebration missteps

According to Lady C: She's not aware of any of these 24 Dukes being invited to the coronation. Julie Montague, Viscountess of Hinchingbrooke, found the coronation robe & coronet of the Earl of Sandwich, her father-in-law. The Earldom was created by Charles II, Montague was a big part of bringing him back from exile to England. Now Charles III disses him. They're not invited either, but she's doing commentary for several news outlets. Lady C also said how sorry she felt for the members of Parliaments wives, this would have been a big deal for them & one of a very few perks of being married to a member of the house. The new King is generating hard feelings when it doesn't have to be. He may need these people, royal and non, someday & this will be remembered.

His scaled back monarchy may also be a mistake. Who's going to do all the charity work? The ambassador trips? He's leaving only so many older folks to handle everything. Prince Edward is 59 & he's the youngest brother. I think there aren't enough younger members to fill in when the older ones retire or die.

*These are extant non-royal dukes in the United Kingdom. Two double and one triple Dukes.

Duke of Abercorn (Ireland)

Duke of Argyll (Scotland), (United Kingdom)

Duke of Atholl (Scotland)

Duke of Beaufort (England)

Duke of Bedford (England)

Duke of Buccleuch (Scotland), Duke of Queensberry (Scotland) (currently all one person)

Duke of Devonshire (England)

Duke of Fife (United Kingdom)

Duke of Grafton (England)

Duke of Hamilton (Scotland), Duke of Brandon (Great Britain) (currently all one person)

Duke of Leinster (Ireland)

Duke of Manchester (Great Britain)

Duke of Marlborough (England)

Duke of Montrose (Scotland)

Duke of Norfolk (England)

Duke of Northumberland (Great Britain)

Duke of Richmond (England), Duke of Gordon (United Kingdom), Duke of Lennox (Scotland) (currently all one person)

Duke of Roxburghe (Scotland)

Duke of Rutland (England)

Duke of Somerset (England)

Duke of St Albans (England)

Duke of Sutherland (United Kingdom)

Duke of Wellington (United Kingdom)

Duke of Westminster (United Kingdom)*

*From Wikipedia

1 note

·

View note

Text

2024 olympics Great Britain roster

Archery

Conor Hall (Belfast)

Tom Hall (London)

Alex Wise (Newcastle Upon Tyne)

Megan Havers (Markfield)

Penny Healey (Telford)

Bryony Pitman (Shoreham-By-Sea)

Athletics

Jeremiah Azu (Cardiff)

Louie Hinchliffe (Crosspool)

Zharnel Hughes (The Valley, Anguilla)

Charlie Dobson (Colchester)

Matthew Hudson-Smith (Wolverhampton)

Max Burgin (Halifax)

Elliot Giles (Birmingham)

Ben Pattison (Frimley)

Neil Gourley (Glasgow)

Josh Kerr (Edinburgh)

George Mills (Harrogate)

Sam Atkin (Grimsby)

Patrick Dever (Preston)

Tade Ojora (London)

Alastair Chalmers (Guernsey, Channel Islands)

Richard Kilty (Middlesborough)

Nethaneel Mitchell-Blake (London)

Lewis Davey (Grantham)

Toby Harries (Brighton)

Alex Haydock-Wilson (London)

Sam Reardon (Beckenham)

Emile Cairess (Saltaire)

Mahamed Mahamed (Southampton)

Philip Sesemann (Bromley)

Callum Wilkinson (Moulton)

Jacob Fincham-Dukes (Harrogate)

Scott Lincoln (Northallerton)

Lawrence Okoye (London)

Nick Percy (Glasgow)

Dina Asher-Smith (London)

Imani-Lara Lansiquot (London)

Daryll Neita (London)

Bianca Williams (London)

Amber Anning (Hove)

Laviai Nielsen (London)

Lina Nielsen (London)

Victoria Ohuruogu (London)

Phoebe Gill (St. Albans)

Keely Hodgkinson (Atherton)

Jemma Reekie (Beith)

Georgia Bell (London)

Laura Muir (Milnathort)

Revée Walcott-Nolan (Luton)

Megan Keith (Inverness)

Eilish McColgan (Dundee)

Cynthia Sember (Ypsilanti, Michigan)

Jessie Knight (Epsom)

Lizzie Bird (St. Albans)

Aimee Pratt (Stockport)

Desirèe Henry (London)

Amy Hunt (Nottingham)

Yemi John (London)

Hannah Kelly (Bury)

Jodie Williams (Welwyn Garden City)

Nicole Yeargin (Bowie, Maryland)

Clara Evans (Hereford)

Rose Harvey (London)

Calli Yauger-Thackeray (Flagstaff, Arizona)

Morgan Lake (Reading)

Holly Bradshaw (Preston)

Molly Caudery (Truro)

Katharina Johnson-Thompson (Liverpool)

Jade O'Dowda (Oxford)

Badminton

Ben Lane (Milton Keynes)

Sean Vendy (Milton Keynes)

Kirsty Gilmour (Glasgow)

Boxing

Lewis Richardson (Colchester)

Patrick Brown (Sale)

Delicious Orie (Wolverhampton)

Charley Davison (Lowestoft)

Rosie Eccles (Newport)

Chantelle Reid (Allenton)

Canoeing

Adam Burgess (Stoke-On-Trent)

Joe Clarke (Stoke-On-Trent)

Mallory Franklin (Windsor)

Kimberley Woods (Rugby)

Climbing

Hamish McArthur (York)

Toby Roberts (Elstead)

Erin McNeice (Rodmersham)

Molly Thompson-Smith (London)

Cycling

Tom Pidcock (Leeds)

Josh Tarling (Aberaeron)

Stephen Williams (Aberysthwyth)

Fred Wright (Manchester)

Jack Carlin (Paisley)

Ed Lowe (Stamford)

William Turnbull (Morpeth)

Joe Truman (Petersfield)

Dan Bigham (Newcastle-Under-Lyme)

Ethan Hayter (London)

Ethan Vernon (Bedford)

Oli Wood (Wakefield)

Charlie Tanfield (Great Ayton)

Mark Stewart (Dundee)

Charlie Aldridge (Crieff)

Kieran Reilly (Newcastle Upon Tyne)

Kye Whyte (London)

Ross Cullen (Preston)

Lizzie Deignan (Otley)

Pfeiffer Georgi (Castle Combe)

Anna Henderson (Edlesborough)

Anna Morris (Cardiff)

Sophie Capewell (Lichfield)

Emma Finucane (Carmarthen)

Katy Marchant (Manchester)

Lowri Thomas (Abergavenny)

Elinor Barker (Cardiff)

Neah Evans (Langbank)

Josie Knight (Dingle, Ireland)

Jess Roberts (Carmarthen)

Ella MacLean-Howell (Llantrisant)

Evie Richards (Malvern)

Charlotte Worthington (Chorlton-Cum-Hardy)

Beth Shriever (Braintree)

Emily Hutt (London)

Diving

Jack Laugher (Ripon)

Jordan Houldon (Sheffield)

Noah Williams (London)

Kyle Kothari (London)

Anthony Harding (Ashton-Under-Lyne)

Tom Daley (Plymouth)

Yasmin Harper (Sheffield)

Grace Reid (Edinburgh)

Andrea Spendolini-Sirieix (London)

Lois Toulson (Cleckheaton)

Scarlett Mew-Jensen (London)

Equestrian

Carl Hester (Sark, Channel Islands)

Tom McEwen (London)

Scott Brash (Peebles)

Harry Charles (Alton)

Ben Maher (London)

Lottie Fry (Den Hout, The Netherlands)

Becky Moody (Gunthwaite)

Ros Canter (Louth)

Laura Collett (Royal Leamington Spa)

Field hockey

Tim Nurse (London)

Nick Park (Reading)

Jack Waller (London)

David Ames (Cookstown)

Jacob Draper (Cwmbran)

Zachary Wallace (Kingston-Upon-Thames)

Rupert Shipperley (London)

Sam Ward (Leicester)

James Albery (Cambridge)

Phil Roper (Chester)

David Goodfield (Shrewsbury)

Ollie Payne (Totnes)

Liam Sanford (Wegberg, Germany)

Lee Morton (Glasgow)

Thomas Sorsby (Sheffield)

Conor Williamson (London)

Will Calnan (London)

Gareth Furlong (London)

Laura Unsworth (Sutton Coldfield)

Anna Toman (Derby)

Hannah French (Ipswich)

Sarah Jones (Cardiff)

Amy Costello (Edinburgh)

Sarah Robertson (Melrose)

Charlotte Watson (Dundee)

Tessa Howard (Durham)

Isabelle Petter (Loughborough)

Giselle Ansley (Brixham)

Hollie Pearne-Webb (Duffield)

Fiona Crackles (Kirkby Lonsdale)

Sophie Hamilton (Bruton)

Lily Owsley (Bristol)

Flora Peel (Cheltenham)

Miriam Pritchard (Loughborough)

Golf

Matt Fitzpatrick (Sheffield)

Tommy Fleetwood (Dubai, U.A.E.)

Charley Hull (Kettering)

Georgia Hall (Bournemouth)

Gymnastics

Joe Fraser (Birmingham)

Harry Hepworth (Leeds)

Jake Jarman (Peterborough)

Luke Whitehouse (Halifax)

Max Whitlock (Hemel Hempstead)

Zak Perzamanos (Liverpool)

Becky Downie (Nottingham)

Ruby Evans (Cardiff)

Georgia-Mae Fenton (Gravesend)

Alice Kinsella (Sutton Coldfield)

Abi Martin (Paignton)

Bryony Page (Sheffield)

Isabelle Songhurst (Poole)

Judo

Chelsie Giles (Coventry)

Lele Naire (Weston-Super-Mare)

Lucy Renshall (St. Helens)

Katie-Jemima Yeats-Brown (Pembury)

Emma Reid (Royston)

Pentathlon

Charlie Brown (Kidderminster)

Joe Choong (London)

Kerenza Bryson (Plymouth)

Kate French (Chapmanslade)

Rowing

James Robson (Oundle)

Ollie Wynne-Griffith (Guildford)

Tom George (Cheltenham)

Oli Wilkes (Matlock)

David Ambler (London)

Matt Aldridge (Christchurch)

Freddie Davidson (London)

Tom Barras (Staines-Upon-Thames)

Callum Dixon (London)

Matt Haywood (Burton Upon Trent)

Graeme Thomas (Burton)

Sholto Carnegie (Oxford)

Rory Gibbs (Street)

Morgan Bolding (Weybridge)

Jacob Dawson (Portsmouth)

Charlie Elwes (Radley)

Tom Digby (Henley-On-Thames)

James Rudkin (Northampton)

Tom Ford (Holmes Chapel)

Harry Brightmore (Chester)

Henry Fieldman (Barnes)

Liv Bates (Nottingham)

Chloe Brew (Plymouth)

Rebecca Edwards (Aughnacloy)

Becky Wilde (Taunton)

Mathilda Hodgkins-Byrne (London)

Emily Craig (Pembury)

Imogen Grant (Cambridge)

Helen Backshall (Truro)

Esme Booth (Stratford-Apon-Avon)

Samantha Redgrave (Frinton)

Rebecca Shorten (Belfast)

Lauren Henry (Lutterworth)

Hannah Scott (Coleraine)

Lola Anderson (London)

Georgina Brayshaw (Leeds)

Heidi Long (London)

Rowan McKellar (Glasgow)

Holly Dunford (Tadworth)

Emily Ford (Holmes Chapel)

Lauren Irwin (Peterlee)

Eve Stewart (Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

Harriet Taylor (Chertsey)

Annie Campbell-Orde (Wells)

Lucy Glover (Warrington)

Rugby

Abi Burton (Wakefield)

Kayleigh Powell (Llantrisant)

Amy Wilson-Hardy (Poole)

Ellie Boatman (Camberley)

Ellie KIldunne (Keighley)

Emma Uren (London)

Grace Crompton (Epsom)

Heather Cowell (Isleworth)

Isla Norman-Bell (Gillingham)

Jade Shekells (Hartpury)

Jasmine Joyce-Butchers (St. Davids)

Lauren Torley (Flackwell Heath)

Lisa Thomson (Hawick)

Megan Jones (Cardiff)

Sailing

Connor Bainbridge (Halifax)

James Peters (Tunbridge Wells)

Fynn Sterritt (Inverness)

Sam Sills (Launceston)

Micky Beckett (Solva)

Chris Grube (Chester)

John Grimson (Leicester)

Emma Wilson (Christchurch)

Ellie Aldridge (Parkstone)

Hannah Snellgrove (Lymington)

Freya Black (Redhill)

Saskia Tidey (Dublin, Ireland)

Vita Heathcote (Southampton)

Anna Burnet (London)

Shooting

Mike Bargeron (Bromley)

Matthew Coward-Holley (Chelmsford)

Nathan Hales (Chatham)

Seonaid McIntosh (Edinburgh)

Lucy Hall (York)

Amber Rutter (Windsor)

Skateboarding

Andy Macdonald (Newton, Massachusetts)

Sky Brown (Takanabe, Japan)

Lola Tambling (Saltash)

Swimming

Ben Proud (London)

Alex Cahoon (Fairford)

Matt Richards (Droitwich Spa)

Jacob Whittle (Alfreton)

Duncan Scott (Glasgow)

Kieran Bird (Street)

Daniel Jervis (Resolven)

Oliver Morgan (Bishops Castle)

Jonathon Marshall (Southend-On-Sea)

Luke Greenbank (Crewe)

Adam Peaty (Uttoxeter)

James Wilby (Glasgow)

Jimmy Guy (Timperley)

Tom Dean (Maidenhead)

Max Litchfield (Chesterfield)

Joe Litchfield (Chesterfield)

Jack McMillan (Belfast)

Hector Pardoe (Wrexham)

Toby Robinson (Wolverhampton)

Kate Shortman (Clifton)

Isabelle Thorpe (Clifton)

Anna Hopkin (Chorley)

Kathleen Dawson (Kirkcaldy)

Medi Harris (Porthmadog)

Honey Osrin (Portsmouth)

Katie Shanahan (Glasgow)

Angharad Evans (Cambridge)

Keanna Macinnes (Edinburgh)

Laura Stephens (London)

Abbie Wood (Buxton)

Freya Colbert (Grantham)

Eva Okaro (Sevenoaks)

Lucy Hope (Melrose)

Freya Anderson (Birkenhead)

Leah Crisp (Wakefield)

Table tennis

Liam Pitchford (Chesterfield)

Anna Hursey (Tianjin, China)

Taekwondo

Bradly Sinden (Doncaster)

Caden Cunningham (Huddersfield)

Jade Jones (Bodelwyddan)

Rebecca McGowan (Dumbarton)

Tennis

Jack Draper (London)

Dan Evans (Dubai, U.A.E.)

Joe Salisbury (London)

Neal Skupski (Liverpool)

Sir Andy Murray (Leatherhead)

Katie Boulter (Woodhouse Eaves)

Heather Watson (St. Peter Port, Channel Islands)

Triathlon

Sam Dickinson (York)

Alex Yee (London)

Beth Potter (Bearsden)

Georgia Taylor-Brown (Leeds)

Kate Waugh (Newcastle Upon Tyne)

Weightlifting

Emily Campbell (Bulwell)

#Sports#National Teams#U.K.#Celebrities#Races#Michigan#Maryland#Fights#Boxing#Boats#Ireland#Animals#The Netherlands#Hockey#Germany#Golf#U.A.E.#Massachusetts#Tennis

0 notes

Text

Article "Edward IV"

The fifteenth century English civil war that became known as the "Wars of the Roses" arose out of tension between the rival houses of Lancaster and York. Both dynasties could trace their ancestry back to Edward III. Both vied for influence at the court of the Lancastrian King Henry VI. The growing enmity that existed between these two noble lineages eventually led to a pattern of political manoeuvring, backstabbing, and bloodshed that culminated in a contest for the crown and Edward of York’s seizure of the throne to become Edward IV, first Yorkist King of England.

Born at Rouen on April 28, 1442, Edward was the eldest son of Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, "The Rose of Raby". Dubbed “The Rose of Rouen” due to his fair features and place of birth, Edward sported golden hair and an athletic physique. Growing to over six feet tall, the young Earl of March developed into the conventional medieval image of a military leader, ever ready to enter the fray. Intelligent and literate, Edward could read, write, and speak English, French, and a bit of Latin. He enjoyed certain chivalric romances and histories as well as the more physical aristocratic pursuits of hunting, hawking, jousting, feasting, and wenching. Edward proved time and again to be a valiant warrior and competent commander, personally brave and at the same time capable of understanding the finer points of strategy and tactics. As king, he displayed a direct straightforwardness and lacked much of the devious cunning exhibited by some of his contemporaries.

Young Edward of March became embroiled in the dynastic struggle between the Houses of Lancaster and York while still a teen. The family feud erupted into violence for the first time on May 22, 1455, when Yorkist forces under command of the Duke of York and the Earl of Warwick, and Lancastrian forces under command of the Duke of Somerset and King Henry, came to blows on the streets of St. Albans. After a disastrous debacle at Ludford Bridge on October 12, 1459, the Yorkist leaders fled for Calais and Ireland. Edward, Earl of March, was among those declared guilty of high treason by an Act of Attainder passed by Parliament on November 20.

In the summer of 1460, the Earl of March sailed from Calais to Sandwich with the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick and two-thousand men-at-arms. During Edward’s first proper taste of battle at Northampton in July of that year, he and the Duke of Norfolk co-commanded the vanguard that eventually breached the Lancastrian field fortifications, thanks in part to the traitorous actions of the Lancastrian turncoat Lord Grey of Ruthyn. After the Yorkist victory at Northampton, Edward’s father returned to England and made clear his desire to become king, but the assembled lords failed to support his claim.

With the contest between Lancaster and York still undecided, Edward was given his first independent command. He was sent to Wales to quell an uprising led by Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke, while his father marched out of London to tackle the northern allies of Henry VI’s Queen Margaret of Anjou. Drawn out of Sandal Castle by the appearance of a Lancastrian army, Richard of York fell in battle outside its walls on December 30, 1460. His severed head, along with those of his younger son Edmund, the Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, the Earl of Salisbury, soon adorned spikes atop the city of York’s Micklegate Bar. A paper crown placed on his bloody pate mocked the Duke’s failed bid for the throne. On the site of his father's death, Edward later erected a simple memorial consisting of a cross enclosed by a picket fence.

Now Duke of York, Edward gathered an army in the Welsh marches to avenge the deaths of his father and younger brother. Having spent his boyhood in Sir Richard Croft’s castle near Wigmore, Edward was well known in the region. He made ready to march toward London to support the Earl of Warwick, but then turned north to face an enemy force led by the Earls of Pembroke and Wiltshire. A strange sight greeted the anxious Yorkist troops at Mortimer's Cross that frosty dawn of February 2, 1461. Three rising suns shone in the morning sky. Quick to declare this meteorological phenomenon a positive omen, Edward announced that the Holy Trinity was watching over his army. After his victory at Mortimer’s Cross, Edward added the sunburst to his banner and badge. To make clear that the conflict had entered a more savage phase, Edward ordered the execution of Owen Tudor and nine other captured Lancastrian nobles. Tudor’s severed head went on display on the market cross at Hereford, where a mad woman combed his hair, washed his bloody face, and lit candles around the grisly memorial.

On February 17, the Earl of Warwick suffered his first defeat at the second battle St. Albans, brought about in part by treachery within his ranks. However, London refused to open its gates to Queen Margaret’s looting Lancastrian army, a force the citizens of the capital feared was full of northern savages. Reunited with King Henry, but frustrated by London’s mistrustful citizenry, the queen withdrew her forces toward York. Warwick and what troops he had left then met up with the victorious Edward at either Chipping Norton or Burford on February 22.

Greeted by cheers, Edward and the Earl of Warwick, marched into the capital on February 26. Warwick’s brother, the Chancellor George Neville, asked the people who they wished to be King of England and France. They answered with shouts for Edward. On March 4, 1461, the Duke of York rode from Baynard’s Castle to Westminster, where the Yorkist peers and commons and merchants of London formally proclaimed him King Edward IV.

The new Yorkist king’s official coronation was postponed while he prepared to set out in pursuit of Margaret and Henry. After sending Lord Fauconberg northward at the head of the king’s footmen on the 11th, Edward marched out of the capital on the 13th. He issued orders prohibiting his army from committing robbery, sacrilege, and rape upon penalty of death. He followed the trail of pillaged towns and razed homesteads left behind by Margaret’s northern moss-troopers.

On March 22, Edward received word that his enemies had taken up position behind the River Aire. On March 28, his vanguard tangled with a Lancastrian force holding the wooden span at Ferrybridge. Outflanking the defenders by sending a part of his army across the Aire at Castleford, Edward managed to push his men across the bridge and up the Towton road.

The two armies drew up in battle order on a snowy Palm Sunday, March 29, 1461. At some point during the morning the snow shifted, blowing into the faces of the Lancastrian soldiers. Taking advantage of the favourable wind, Fauconberg ordered his archers forward. The ensuing volley initiated the biggest, bloodiest, and most decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses.

Edward displayed steadfast courage as the battle raged. The young king rode up and down the line and joined in the melee whenever the ranks appeared ready to waver. No quarter was given, for both sides wished to settle the issue once-and-for-all, and the dead piled up between the opposing men-at-arms. At times, the fighting momentarily ceased while the bodies of the slain were pulled aside to make room for continued bloodshed.

After several hours of fierce fighting, the Yorkist line began to give way. However, the arrival of the Duke of Norfolk’s reinforcements tipped the balance in the Yorkist favour, and the exhausted Lancastrian army eventually faltered and broke. Many fleeing soldiers were cut down by Yorkist prickers in an area now known as Bloody Meadow. As was allegedly his habit when victorious, Edward may have given orders to spare the commons but slay the lords. Those Lancastrian nobles that survived the slaughter, along with King Henry, Queen Margaret, and their son Prince Edward, sought sanctuary in Scotland.

Victory at Towton established the Yorkist dynasty, but over the next three years Edward’s rule still faced a series of Lancastrian-inspired rebellions. Many of these uprisings against the Yorkist crown centred on Lancastrian strongholds in Northumberland. Most of Queen Margaret’s moves in the years immediately following the battle revolved around control of various castles, with some rather dubious aid from the Scots. In 1463, Margaret was finally forced to flee to France when Warwick and his brother routed her Scottish allies at Norham. Left behind by his queen, Henry VI held state in the gloomy fortress at Bamburgh. Warwick besieged this stronghold during the summer of 1464, and it became the first English castle to succumb to cannon fire. Captured in Clitherwood twelve months later and abandoned by his queen and allies, the Lancastrian king was sent to the Tower of London. Edward's throne finally seemed secure. However, Edward next faced threat from an unexpected corner as Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, turned on the man he helped make king.

In 1464, Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville, a comparatively lowborn Lancastrian widow. This caused a rift to form between the king and the Earl of Warwick. Edward's in-laws began to exert a growing influence over his court. Displeased with his own waning influence, in 1469 Warwick orchestrated a rebellion in the north. Edward remained in Nottingham while his Herbert and Woodville allies suffered defeat at Edgecote on July 26, 1469. The king then fell under Warwick's protection. On March 12, 1470, Edward was able to rout the rebels at the battle of Losecote Field, a moniker that arose from the fact that many men fleeing the battle discarded their livery jackets displaying the incriminating badges of Warwick and Edward's treacherous brother, the Duke of Clarence. With their treachery made plain, Warwick and Clarence sailed to France and formed an unlikely alliance with Margaret of Anjou. When Warwick returned to England with his new Lancastrian allies, Edward the lost support of the country and fled to the Netherlands. Warwick "The Kingmaker" reinstated the Lancastrian monarch during Henry's Readeption of 1470-1.

Edward IV spent his time in exile assembling an invasion fleet at Flushing and trying to woo his wayward brother back to the Yorkist cause. On March 14, 1471, Edward returned to the realm he claimed as his own, landing at Ravenspur. The Duke of Clarence promptly deserted Warwick and marched to his brother’s aid. Edward headed for London and entered the capital on April 11. Reinforced by Clarence’s troops, Edward took King Henry out of the capital and led a swelling army to face Warwick at Barnet. Edward suffered an early setback as he clashed with his one-time ally on that misty Easter morn of April 14, 1471. The Yorkist left collapsed, and the centre was slowly pushed back, but confusion caused by the obscuring fog eventually doomed Warwick's army. Warwick’s soldiers mistook the star with streams livery worn by the men of the Lancastrian Earl of Oxford for Edward’s sun with streams and loosed volleys of arrows into the approaching troops. With cries of “treason”, Oxford’s men left the field. Sensing the unease that rattled the Lancastrian ranks, Edward rallied his men and pressed the attack. Under this renewed pressure, Warwick’s army wavered and broke. The earl tried to flee the battlefield, but Yorkist soldiers pulled him from his saddle and despatched him with a knife thrust through an eye. Edward arrived on the scene too late to save Warwick from such an ignoble fate.

On May 4, Edward once more led his troops into battle, this time against Queen Margaret’s army at Tewkesbury. Margaret and her son, Prince Edward, had landed at Weymouth with a small force the same day of Edward’s victory over Warwick at Barnet. Under the leadership of the Duke of Somerset, the Lancastrian force moved toward Wales to try to join forces with Jasper Tudor. Wishing to bring Margaret’s army to battle before it crossed the Severn, Edward gave chase. He caught up with Somerset and Margaret at Tewkesbury. Though his army was slightly outnumbered, the Yorkist king once again triumphed over the Lancastrians. Margaret's son, Prince Edward, was captured and slain. Some Lancastrian fugitives, including the Duke of Somerset, tried to seek sanctuary in Tewkesbury Abbey. Dispute surrounds the exact details regarding what happened inside. Edward either granted pardons to those sheltering within the abbey walls, and then reneged on his promise, or he and his men entered the building with swords drawn. Either way, those captives that survived the slaughter were subsequently executed.

With the exception of quickly quelled Kentish and northern revolts, Edward’s triumph at Tewkesbury signalled the end of Lancastrian opposition to his reign. Margaret was captured and brought before Edward on May 12. She remained his prisoner until ransomed by King Louis XI of France. After making his formal entry into London on the 21st, Edward arranged the clandestine murder of poor King Henry VI. Edward’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, entered the Tower that evening. By the next morning, Henry, the potential focus of future Lancastrian resistance to Yorkist rule, was dead.