#the 1-turn cut actually usually lets her line up better with galleon to help make up for galleon only attacking every other turn

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

0(:3 )~ =͟͟͞͞(’、3)_ヽ)_

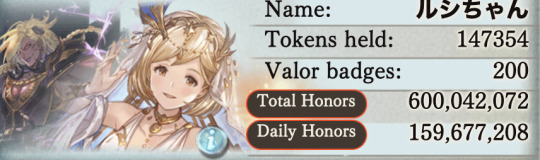

okay, now i can just focus on doing at least 100 mil tomorrow and on day four for the sand. i accidentally solo’d into b tier again and won the first final round so even losing these next three will put me at enough for a sunlightstone, but all i really want is that fcking sand so i can fully uncap the goddamn hanged man spear. amelia pulling her goddamn weight in nm 100 keeping the party constantly armored

#sammy liveblogs about granblue#sammy be quiet#dumb text post#sammy no#using blessed kiss and pneuma on amelia turn one so she has a perma undispelable 10 buffs lol#i still think iatro is better than ult mastery sage for the sake that i can be offensive and have full ta + bonus dmg#i'm not spending the mats for what? a buff that only works if i die? an extra heal on a 5 turn cooldown? a 12 turn cooldown shield?#besides vita removes a debuff on cast which is nicer (though it mattered more on nm 95 as it seems nm 100 has a harder time landing them)#like as funny as it would be to have panacea iii on therapeutic stance and 2-turn debuff cutting instead of 1-turn cutting on vikki ca seal#the 1-turn cut actually usually lets her line up better with galleon to help make up for galleon only attacking every other turn#i love that c.a. seals that can't be removed by clears can still have their duration cut#i do the same thing in light with yuni and the cagi grand mainhand#since the staff has 1.5 c.a. seal on ougi and yuni activates her skill that 1 turn cuts to debuffs on her ougi if we ougi at the same time#the c.a. seal get's cut to .5 turn and its gone on the next turn lolol#so if yuni has her ougi ready i can ougi two turns in a row with overtrance

0 notes

Text

habit.

1.

The road that leads up to the Willow House in Godric’s Hollow — it hadn’t been called anything in a while, and the willow trees that lined the path earned it its name — is usually well-travelled. The three inhabitants at the end of the straight and narrow dirt path do not mind the small distance from the front door to the paved road. The walk can sometimes be soothing, especially when done alone, without the company of children.

Yixing indulges in it on the same day, at precisely the same time every week. His back remains slightly slouched, and the clean-shaven face only appears on this day, at the same time, every week, as if he’s meeting someone of importance. The eyes behind round spectacles look as weary as they’ve ever been, and his hands, for a moment, cease to shake when he pushes the gate open to the graveyard, as if it’s being held and lead towards the same spot. On the same day. Same time. Every week.

Six years cannot change habit.

2.

This morning, Finley Song leaves the house to attend the same castle where his parents first met. He does not know the circumstances of it — Father ( and this is how he has come to call the man, and he hasn’t been corrected so far ) won’t speak of it. Can’t. Doesn’t.

Finn’s old enough to know that stubbornness comes in the form of Yixing Song, who locks himself in the greenhouse, who doesn’t let the children inside the basement as if it’s some grand memorial to a wife he refuses to let go of.

“How long ’til you come home?” Irving sits on his brother’s bed like it’s his own already. The boy is more eloquent than his own, and Finn, though his temper is something to be cautious of when he’s in one of his moods, has always made sure to set aside a fair bit of attention to his younger brother. Days are usually spent between themselves, anyway, and Yixing won’t let them get out of the house because they’re too young, refusing to acknowledge that his sons have grown up too quickly without him.

“I’ll be home for Christmas.” Finn pats his coat for his wand, makes sure that his proper robes are in his backpack. Everything else is packed neatly in his luggage — Father helped him with the spell to make it fit, and so that the thing can be light enough to carry on his own downstairs — and all seemed to be in order. “You and Father can pick me up.”

“I’ll make sure dad remembers!” Finn rolls his eyes at that, and doesn’t bother to correct the boy. Last year Yixing almost forgot Finn’s own birthday. Instead, he tugs the luggage down the stairs, and Irving follows along. “I can’t wait for Christmas!”

“I can’t wait to get out of here,” Finn retorts lightly. The clock face that hangs in the kitchen told him that Father won’t be back for the next hour, judging by the sound of the closing door over breakfast, by which time Finn would be late to his train. There’s no use in waiting.

The cab outside, on the other hand, waits for him instead, and Finn continues the trip to the front door. The cabbie takes his bags, which does little to relieve the nervous sensation in his stomach.

“Alright, Irving,” Finn begins, fishing out galleons for the cab driver before turning towards his younger brother, who looks up at him ( literally, and figuratively ), duck-print pyjamas and all, “when Father asks where I’ve gone you tell him I went to school, okay?”

“He said last night we’d drop you off!” comes the expected and petulant reply, and the frown aimed at the cab driver. “He’s gonna be mad at you!”

“I’m going to be late!”

“Your brother’s right.”

The voice makes him turn around.

Yixing Song stands there, back straight as if he’d had the years of fatigue knocked out of his lungs, and holds his hand out expectantly for the galleons his son had given the driver. With a small grumble and an intimidating glare, the coins find its way back in his hands, and so they get placed upon Finn’s much smaller, trembling palm.

“I will be quite cross with you, Finley. Glad to see that I won’t be anymore.”

3.

He’s not greeted with warmth. He doesn’t expect to be. Yixing has always treated his sons with the same amount of fatherly strictness he barely remembers from his own grandfather, sans the raised fists and life-threatening experience. Yixing never hit his sons, but his words might as well have the same effect.

“Go change your clothes, Irving.” The younger boy looks at his father, then at his brother. “Now. I thought you wanted to go drop your brother off with me?”

That’s enough to get the kid to run back to the house, smiles and all.

Finley, on the other hand, seems displeased.

“You cut your visit to Mother. You didn’t have to —,”

“You think I’m going to miss seeing you off?” It came out as more of an angry snap than an offended reassessment. He almost expects Rose to berate him for it.

( He’s afraid of forgetting the sound of her voice. )

“Leave your bags inside the house. We’re visiting someone quickly before you go.” At the lack of inaction, his frown deepens. “Now, Finley. Unless you want to be late for your train?”

4.

Irving doesn’t remember ever seeing Yixing smile.

Finn tells him, don’t even try, I don’t think he can actually do it, but Irving, having recently obtained the power of semi-decent sentences, has become quite adept at picking up phrases and becoming more eloquent. He’s almost six, now, and he’s old enough to think that, maybe, if he sounded as smart as his brother, Yixing might look at him for more than two seconds. Irving grows up around magic, after all, and miracles aren’t far from reality.

So Irving remains hopeful. They’re visiting Mother, who might as well be a stranger to the young boy, and, it seems, his dad’s entire world, buried six feet under.

5.

Finn doesn’t understand his father’s obsession with the dead.

Yixing is rarely at home, always in his greenhouse or the cemetery. Breakfast, lunch and dinner are always prepared beforehand. The plants in his father’s greenhouse talk of a time when he was happy, when his expression was brighter, when their owner and creator didn’t spend nights hunched over his research and, instead, would walk through the back door, and smile at his wife, and love her.

Finn cannot imagine it.

The mother he remembers is all but a faceless silhouette, face framed by golden hair — or was it dark as night? He was too young, then — who taught him how to read and write, as easy as breathing. All that remains of her now is Yixing, and the weight on his shoulders.

There are no photos on the wall.

6.

“Your mother would know what to say.”

They stop at a gravestone among many. This one has a cactus who greets them, the flower atop it bristling under a light breeze, and remains quiet when it senses that Yixing is not alone, and remains lifeless, as if in understanding. Plants are better than people like that.

Finn shifts his weight from one foot to another, clearly uncomfortable. Irving holds onto his brother’s hand, and looks at the plant in its pot with every intention to touch it. Yixing’s temper is the only thing keeping him from it. Neither of them ask about their mother, because experience has taught them that all they will get is a glare, and controlled anger in a tone as biting as any harsh winter.

But the man does not notice. His gaze remains on the words engraved upon sleek, polished stone, kept clean and immaculate.

“She’d want to see you off, too.” His hands remain in his pockets. It should be easier; it isn’t. “She’s proud of you, I think. She really is. No matter what house you end up in, she’ll still be proud of you.”

The children remain quiet. Yixing has a habit of seeming like he’s talking to himself when he’s talking about someone else who isn’t even there.

“Of course, I’d be pleased if you end up in Slytherin. Anywhere but Gryffindor.” The ghosts in their graves pale in comparison to the echo of a smile on Yixing’s lips. Irving looks at it like it’s the sun. “Ravenclaw is good, too. Your mother was sorted there. She made good friends, I like to think.”

Finn’s grip tightens on Irving’s smaller hand. The younger boy winces, and tries to pull his hand away, but Finn doesn’t let go.

“Father, she’s not —,”

“She’s here, Finley!” Yixing glares at the boy again, as if to say anything else is sacrilegious. “She’s always here. You just — you don’t understand.” He takes a deep breath. Rose wouldn’t want him to raise his voice in front of the boys like this, especially in front of her. “Visit the Astronomy Tower for her. Write to me about the stars you see.”

“You’re not going to read it.” In a burst of either courage or stupidity, Finley talked back. Yixing’s frown deepened as a sign of the impending storm.

“Your mother is going to read it.”

“SHE’S NOT HERE! SHE’S NOT EVEN ALIVE ANYMORE —!”

The back of his hand hits a soft cheek so quickly that the sound of it reaches Yixing’s ears before the sensation of it sinks past the skin of his knuckles, and before blood blooms under the boy’s cheek. It’ll bruise later.

“This was a mistake. You’re too young, after all.”

Finn’s words taste like blood, and this time, Irving doesn’t try to take his hand away from his brother’s own, especially when the boy’s tears go unnoticed in the quiet way he does, teeth sinking into his lower lip, shoulders trembling.

Yixing had already turned his back, and as always, they were expected to follow.

7.

Finley sits in the train with his cousins with a pretty bruise on his cheek and a nice lie on his tongue. His tears have long dried, but the edges of his eyes still hold traces of pink that indicates he cried more than he should’ve.

It’s when he dug in his pockets for galleons that he feels the cold metal of a chain, and a pendant that hangs at the end of it. ( Oddly enough, he remembers it’s his father who gave him this coat, and told him to stop crying before he takes them to apparate to the train station. ) His cousins are too busy arguing amongst themselves to notice — it was twins vs. Hyojin again, it seems, and this time the topic is which sweets are better to purchase — and he takes it out, sitting in the corner and keeping it to himself,

and opens locket that holds a photo of him and his mother, smiling, proud,

golden.

2 notes

·

View notes