#that compiled all the textual differences of each manuscript

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

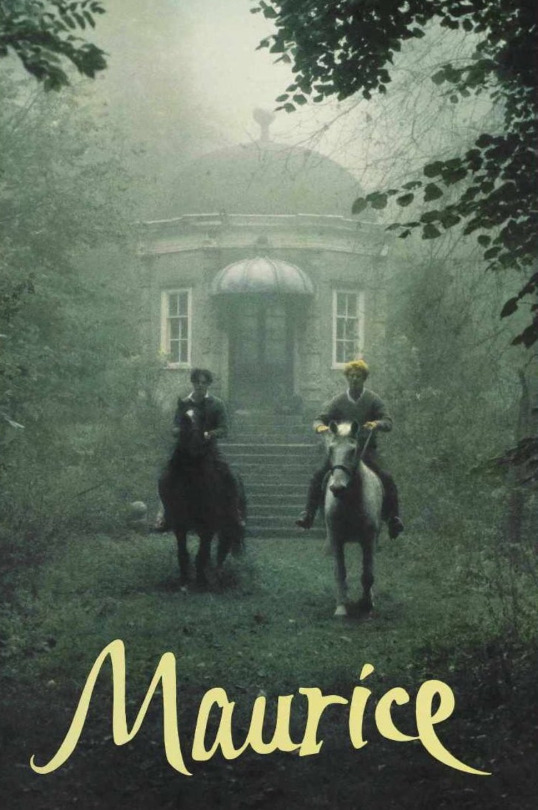

A "Terminal Note" by the author of Maurice, E.M Forster, written in 1960 decades after the original manuscript was completed (1914) but a decade before the book would finally be published posthumously in 1971. The movie is an almost perfect adaptation of the book. If you like gay period pieces with happy endings and a side of class commentary, it's a must watch.

#i got so obsessed with maurice that i got my college to send me an inter library loan from another school of a rare out of print edition#that compiled all the textual differences of each manuscript#maurice#all the sentiment em forster conveys still hits in 2024 if you are gay. but even if you arent gay#its wish fulfillment its a rejection of society its the pain of growing up wrong in peoples eyes and not knowing who you can trust#its the homoerotic best friendship that falls apart brutally#its needing a friend to last your whole life and you theirs#the 1987 date the movie came out is also like. insane to me#what other media was celebrating the potential happy ending being gay could bring during the aids crisis?#and just a year later margaret thatcher's section 28 to pass preventing 'local authorities' from endorsing or promoting homosexuality#that wouldnt have affected the release of this movie since it was independently funded; but the cultural climate was extremely harsh#honestly only saying the movie is almost perfect bc its subjective but it basically is perfectly the novel beat by beat#the stuff that they didnt keep from the book got in as deleted scenes#screenshot from archive.orgs copy of the book which has its own annotations haha#if you dont watch the movie read the book!!!!!!!!#anyway its criminal how overlooked this movie is compared to other gay films#how do people NOT know about it.....*explodes*#the soundtrack is also beautiful and i listen to it a lot to get work done#i cant help but yap about my fav things....#my apologies for the reductive sentence at the end of my post but its just there to catch peoples attention!!!!#i know its *more* than a gay movie with a happy ending but ppl dont even know the bare minimum about it..

362 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the text of the Bible we have today different from the originals?

Sherlock Holmes and John Watson: let’s take a look at the facts

I thought it might be a good idea to write something about whether the Bible is generally reliable as a historical document. Lots of people like to nitpick about things that are difficult to verify, but the strange thing is that even skeptical historians accept many of the core narratives found in the Bible. Let’s start with a Christian historian, then go to a non-Christian one.

First, let’s introduce New Testament scholar Daniel B. Wallace:

Daniel B. Wallace Senior Research Professor of New Testament Studies

BA, Biola University, 1975; ThM, Dallas Theological Seminary, 1979; PhD, 1995.

Dr. Wallace… is a member of the Society of New Testament Studies, the Institute for Biblical Research, the Society of Biblical Literature, the American Society of Papyrologists, and the Evangelical Theological Society (of which he was president in 2016). He has been a consultant for several Bible translations. He has written, edited, or contributed to more than three dozen books, and has published articles in New Testament Studies, Novum Testamentum, Biblica, Westminster Theological Journal, Bulletin of Biblical Review, the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, and several other peer-reviewed journals. His Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament is the standard intermediate Greek grammar and has been translated into more than a half-dozen languages.

Here is an article by Dr. Wallace that corrects misconceptions about the transmission and translation of the Testament.

He lists five in particular:

Myth 1: The Bible has been translated so many times we can’t possibly get back to the original.

Myth 2: Words in red indicate the exact words spoken by Jesus of Nazareth.

Myth 3: Heretics have severely corrupted the text.

Myth 4: Orthodox scribes have severely corrupted the text.

Myth 5: The deity of Christ was invented by emperor Constantine.

Let’s look at #4 in particular, where the argument is that the text of the New Testament is so riddled with errors that we can’t get back to the original text.

It says:

Myth 4: Orthodox scribes have severely corrupted the text.

This is the opposite of myth #3. It finds its most scholarly affirmation in the writings of Dr. Bart Ehrman, chiefly The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture and Misquoting Jesus. Others have followed in his train, but they have gone far beyond what even he claims. For example, a very popular book among British Muslims (The History of the Qur’anic Text from Revelation to Compilation: a Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments by M. M. Al-Azami) makes this claim:

The Orthodox Church, being the sect which eventually established supremacy over all the others, stood in fervent opposition to various ideas ([a.k.a.] ‘heresies’) which were in circulation. These included Adoptionism (the notion that Jesus was not God, but a man); Docetism (the opposite view, that he was God and not man); and Separationism (that the divine and human elements of Jesus Christ were two separate beings). In each case this sect, the one that would rise to become the Orthodox Church, deliberately corrupted the Scriptures so as to reflect its own theological visions of Christ, while demolishing that of all rival sects.”

This is a gross misrepresentation of the facts. Even Ehrman admitted in the appendix to Misquoting Jesus, “Essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual variants in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament.” The extent to which, the reasons for which, and the nature of which the orthodox scribes corrupted the New Testament has been overblown. And the fact that such readings can be detected by comparison with the readings of other ancient manuscripts indicates that the fingerprints of the original text are still to be seen in the extant manuscripts.

Here is the full quote from the appendix of Misquoting Jesus:

“Bruce Metzger is one of the great scholars of modern times, and I dedicated the book to him because he was both my inspiration for going into textual criticism and the person who trained me in the field. I have nothing but respect and admiration for him. And even though we may disagree on important religious questions – he is a firmly committed Christian and I am not – we are in complete agreement on a number of very important historical and textual questions. If he and I were put in a room and asked to hammer out a consensus statement on what we think the original text of the New Testament probably looked like, there would be very few points of disagreement – maybe one or two dozen places out of many thousands. The position I argue for in ‘Misquoting Jesus’ does not actually stand at odds with Prof. Metzger’s position that the essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual variants in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament.”

Finally, I think that the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls shows us that religious texts don’t change as much as we think they do over time.

Look:

The Dead Sea Scrolls play a crucial role in assessing the accurate preservation of the Old Testament. With its hundreds of manuscripts from every book except Esther, detailed comparisons can be made with more recent texts.

The Old Testament that we use today is translated from what is called the Masoretic Text. The Masoretes were Jewish scholars who between A.D. 500 and 950 gave the Old Testament the form that we use today. Until the Dead Sea Scrolls were found in 1947, the oldest Hebrew text of the Old Testament was the Masoretic Aleppo Codex which dates to A.D. 935.{5}

With the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, we now had manuscripts that predated the Masoretic Text by about one thousand years. Scholars were anxious to see how the Dead Sea documents would match up with the Masoretic Text. If a significant amount of differences were found, we could conclude that our Old Testament Text had not been well preserved. Critics, along with religious groups such as Muslims and Mormons, often make the claim that the present day Old Testament has been corrupted and is not well preserved. According to these religious groups, this would explain the contradictions between the Old Testament and their religious teachings.

After years of careful study, it has been concluded that the Dead Sea Scrolls give substantial confirmation that our Old Testament has been accurately preserved. The scrolls were found to be almost identical with the Masoretic text. Hebrew Scholar Millar Burrows writes, “It is a matter of wonder that through something like one thousand years the text underwent so little alteration. As I said in my first article on the scroll, ‘Herein lies its chief importance, supporting the fidelity of the Masoretic tradition.'”{6}

A significant comparison study was conducted with the Isaiah Scroll written around 100 B.C. that was found among the Dead Sea documents and the book of Isaiah found in the Masoretic text. After much research, scholars found that the two texts were practically identical. Most variants were minor spelling differences, and none affected the meaning of the text.

One of the most respected Old Testament scholars, the late Gleason Archer, examined the two Isaiah scrolls found in Cave 1 and wrote, “Even though the two copies of Isaiah discovered in Qumran Cave 1 near the Dead Sea in 1947 were a thousand years earlier than the oldest dated manuscript previously known (A.D. 980), they proved to be word for word identical with our standard Hebrew Bible in more than 95 percent of the text. The five percent of variation consisted chiefly of obvious slips of the pen and variations in spelling.”{7}

Despite the thousand year gap, scholars found the Masoretic Text and Dead Sea Scrolls to be nearly identical. The Dead Sea Scrolls provide valuable evidence that the Old Testament had been accurately and carefully preserved.

I hope that this post will help those who think that we can’t get back to the text of the original New Testament documents.

Go to the article

0 notes

Text

10 Mysterious Ancient Inventions Science Still Can’t Explain

var h12precont = 'h12c_300x250_' + Math.floor(Math.random()*1000000); document.write('

'); (h12_adarray = window.h12_adarray || []).push({"adcontainer":h12precont,"placement":"c9d6b99f00114c5a436a0f497c7bb182","size":"300x250","type":"standard","width":"300","height":"250","name":""});

Googling “mysterious historical discoveries” or “unexplained historical innovations” results in dozens of websites itemizing artifacts supposedly so baffling the one potential reply may very well be aliens, time journey, the paranormal, the Iluminati, or aliens. Wait – did we already point out aliens? Sorry: they’re a go-to clarification for something apparently too refined, bizarre, or “out-of-place” for “people figured it out, okay?” to be a satisfying clarification.

It’s a disheartening discovery, as a result of when you separate the hoaxes and nonsense from the finds of precise archeological curiosity, there are nonetheless cool mysteries to discover. The listing beneath options mysterious historical innovations, unexplained historical discoveries, and a few barely newer finds nonetheless baffling to scientists within the 21st century – however not as a result of they’re an indication of alien tech. Give humanity just a little extra credit score, y’know?

Lethal “Greek Hearth” Was a Household Secret

Photograph: Public Area/via Wikimedia

It’s not like anybody is aching for napalm to make a comeback, however scientists and historians are nonetheless very curious about Seventh-century “Greek Hearth,” a lethal proto-napalm fired from ships that “would cling to flesh and was unattainable to extinguish with water.” Feels like a nightmare!

The Byzantine Empire wielded it with aplomb, however, like Coca-Cola Traditional and Bush’s Baked Beans, the recipe for Greek Hearth

was a protected household secret. Nationwide Geographic pulled a Mythbusters and took a guess on the elements in 2002, utilizing a “bronze pump” and a “combination of sunshine crude oil and pine resin.” The outcomes? It destroyed a ship “in minutes.” Good guess!

The Recipe for Damascus Metal Stays a Thriller

Photograph: Public Area/via Wikimedia

Getting back from the Crusades, quite a lot of perplexed Europeans began speaking about swords wielded by Islamic warriors “that would slice by means of a floating handkerchief, bend 90 levels and flex again with no harm.” Quick-forward to the 21st century and the recipe for so-called “Damascus steel” is nonetheless a thriller. The blades had been probably manufactured from “crucible metal,” which is created by melting iron with plant matter, however nobody is aware of the particular sort of crucible metal used to yield such a blade. It’d as properly be a lightsaber.

The Voynich Manuscript Could In the end Simply Be Indecipherable

Photograph: Public Area/via Wikimedia

Should you haven’t heard of the Voynich Manuscript, you’re in for a deal with. Researchers say the completely bonkers, hand-written and hand-drawn manuscript, that includes textual content in an indecipherable language and a whole lot of illustrations together with “a myriad of drawings of miniature feminine nudes, most with swelled abdomens, immersed or wading in fluids and oddly interacting with interconnecting tubes and capsules,” was created by somebody someday through the 15th century in Central Europe. A Polish-American antiquarian bookseller named Wilfrid M. Voynich acquired it in 1912. Apart from that, who is aware of? It’s a complete thriller.

If it’s presupposed to imply something or assist folks perceive something, it has failed miserably. That stated, it is among the few real mysteries on the market. Do your self a favor: leap down the Voynich rabbit hole. Simply don’t blame Ranker if you happen to lose your thoughts just a little.

The Antikythera Mechanism Is a Mysterious Astrological Calendar

Photograph: Marsyas /via Wikimedia

Not like the Roman dodecahedra, scientists have a pretty good idea what the so-called Antikythera Mechanism is all about. Found on the backside of the ocean in 1901, the intricate gadget was probably constructed across the finish of the second century BC. It “calculated and displayed celestial info, notably cycles such because the phases of the moon and a luni-solar calendar,” in keeping with analysis compiled in Nature.

However we nonetheless don’t know who constructed it, who used it, and what they used it for, precisely. It’s additionally nonetheless unclear why it’s “technically extra advanced than any recognized gadget for no less than a millennium afterwards,” to cite the Nature summary, which prompted a zillion “historical aliens” and “TIME TRAVEL IS REAL!!” weblog posts after it was revealed in 2006.

However historical past, as Brian Dunning of Skeptoid notes, tells us related gear-based know-how was round two and a half millennia prior, and Occam’s Razor tells us any “siblings” of the Antikythera Mechanism, like most commonplace bronze objects of the interval, had been probably “recycled” into different objects. It’s nonetheless mysterious, only for much less horny causes than some may suppose.

Zhang Heng’s Seismoscope Detected Earthquakes (Someway)

Photograph: Kowloonese/via Wikimedia

The primary earthquake-detecting instrument in historical past was this ornate, golden, dragon-festooned, toad-surrounded vessel from round 132 AD. The image is of a reproduction, however you get the thought, proper? No? Okay, right here’s the idea: when the earth quakes, one of many dragons, every representing principal instructions of the compass, would spit out a ball right into a toad’s mouth, indicating the route of the quake. The instrument was stated to have “detected a four-hundred-mile distant earthquake which was not felt on the location of the seismoscope.” Both that, or somebody bumped up in opposition to it, as a result of to this present day, nobody truly is aware of what was actually contained in the factor. (Extra dragons, possibly?) Some say it may have been a easy pendulum-based system, however the actual “science” stays a thriller.

It’s Unclear How Vikings Made Their Ulfberht Swords

Photograph: Anders Lorange/via Wikimedia

Talking of insane swords – the Vikings could have used strategies or supplies borrowed from the creators of Damascus metal to make their legendary “Ulfberht” swords. When archeologists found the Viking blades, they had been shocked as a result of “the know-how wanted to provide such pure metallic wouldn’t be invented for an additional 800 years.” However in 2014, a Ninth-century Viking grave was found in Scandanavia with an Islamic inscription that means “for/to Allah,” linking the 2 worlds and making the shared data believable – however that’s only a guess. The true origin of the blades continues to be unknown.

Scientists Disagree About Why the Iron Pillar of Delhi Received’t Rust

Photograph: Imahesh3847/via Wikimedia

The more-than-1600-year-old “Iron Pillar of Delhi” has scientists divided about its bizarre resistance to rust. There are two faculties of thought: Workforce Setting says the gentle local weather of Delhi, India, is in the end to thank. Proper place, proper time, basically. Workforce Supplies says it’s all concerning the “presence of phosphorus, and absence of sulfur [and] manganese within the iron,” plus the “giant mass of the pillar.” One factor each camps agree on? It’s a complete thriller how the rust-resistant iron lumps had been “forge-welded to provide the huge six-ton construction.” Regardless, it’s a spectacular piece of engineering.

The Phaistos Disk May Be a Prayer or an Historic Typewriter

Photograph: C messier/via Wikimedia

This large sugar cookie is a head-scratcher, for certain, however there are some attention-grabbing theories on the market. Found in 1908 in Crete, this 6-inch diameter clay disk dates again to round 1700 BC and options 241 “phrases” created out of 45 particular person symbols, organized in a spiral. It may very well be a type of historical “sheet music” to a hymn or prayer devoted to matriarchal deity, or possibly it’s an ancient proto-typewriter? Who is aware of? It certain seems to be scrumptious, although.

Roman Dodecahedra Would possibly Simply Be Candlesticks

Photograph: Itub/via Wikimedia

Should you suppose these little bronze guys would make glorious paperweights or tchotchkes – properly, so did the traditional Romans, possibly? We actually have no idea. They might have been ineffective objects meant for adornment, a dialog piece for the 2nd-to-4th-century Roman equal of espresso tables.

George Hart of Stony Brook College notes dozens of those twelve-sided, 4-to-11 cm. spheroids have been discovered all through Europe, but the Romans made no mention of them. Guesses embody candle stands, flower stands, surveying devices, finger ring-size gauges, and even D&D-style cube. Possibly the traditional Romans had been pen-and-paper stylus-and-papyrus RPG lovers?

Associated

Artykuł 10 Mysterious Ancient Inventions Science Still Can’t Explain pochodzi z serwisu PENSE LOL.

source https://pense.lol/10-mysterious-ancient-inventions-science-still-cant-explain/

0 notes

Link

So which version of the Bible is best? Which one should you choose to do your daily reading and study from? Or is there even a best one? There have been countless articles written on this topic over the years. And they often reach different conclusions. The intent of this post is to share my thoughts about how to choose the best translation for you. The Translation Type If you are using an English Bible, or any language other than the original, you will be dealing with translation issues. The Old Testament was mostly written in Hebrew while the New Testament was written in Greek. While it would be wonderful if there was a one-to-one correspondence for every word in Hebrew, Greek, and English, the reality is that there is not. Choices have to be made as to how best to translate from one language into another. Formal Equivalence Some translations attempt to keep the translation as close as possible to the form that it had in the original language. This includes as much as possible a direct translation of the individual words and sentence structure. But since vocabulary and sentence structure varies across languages, a direct translation would be very difficult to read. So the translations using formal equivalence will modify the sentence structure to make it more readable in English. In addition some of the more challenging language idioms may be changed for readability purposes. The KJV, NKJV, NASB and CSB are examples of translations that attempt as much as possible to translate in a more formal fashion. Functional Equivalence Other translations do not adhere as rigidly to the original form of a passage. Instead they focus more on producing a functional equivalent. These translations attempt to reproduce the message and intent of the Scripture without necessarily producing a translation that is as close in language as possible. Some expressions in the original language don't make much sense when directly translated. So more contemporary expressions with meanings as near as possible are used instead. The ESV, NIV and GNB are examples of translations that use a more functional approach. Paraphrase There is a third type of translation, commonly called a paraphrase. These are not really so much translations as they are English versions that carry the message of the Scripture, but told in contemporary terms. Paraphrases are generally easier to read, but not as useful for a more in-depth study of the Scripture. The Message and Living Bibles are examples of paraphrases. Manuscript Families There are thousands of partial and complete Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. And few of these manuscripts agree completely on the text they contain. The vast majority of the differences between them are minor scribal errors; misspellings, inserted, omitted, or reordered words. These differences are understandable when you realize that all of these manuscripts were hand copied. And that there were many generations of these hand copied manuscripts. Each copy is subject to potential scribal copy errors. As time went on the copies produced in a specific location would not vary much. But when compared between distinct locations the differences between the copies would become greater. Scholars today, in comparing the many manuscripts have identified between three and five distinct 'families' of manuscripts. The two most important of these for Bible scholars are the Alexandrian and the Byzantine families. Byzantine Family of Manuscripts This family of manuscripts is centered around Asia Minor and contains far and away the largest number of manuscripts; somewhere in the order of 5000. These manuscripts date as early as the 5th century although most are more recent. In the early 16th century Erasmus, a Roman Catholic scholar, compiled the known manuscripts into a single Greek text. Over the years he revised his work a couple of times, and others produced similar consolidated texts. It is worth noting that all of these consolidated texts were produced by comparing known manuscripts and attempting to produce what the authors thought would be the original. This involved attempting to identify scribal errors and what the text would have been before the error. The King James Version In the early 17th century the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible was produced. While this was not the first English translation, it quickly became the most popular. This version was produced based on the work of Erasmus and a couple of other men. Their work was compared and the most common reading made it into the KJV. Sometime after the KJV was finished the Textus Receptus (TR) was produced. This was the Greek text that was chosen by the KJV translators. It became the standard Greek text of the New Testament for 200 years. But since its production, many older manuscripts have been discovered, but not incorporated into the TR. Alexandrian Family of Manuscripts A second important family of manuscripts was produced around the Egyptian city of Alexandria. While there are only a few hundred of these manuscripts, they are generally much older than the Byzantine family. Some of these manuscripts date back into the early 2nd century. In recent years other Greek texts have been produced that use these old Alexandrian manuscripts, as well as those of the Byzantine family. Like the work of Erasmus, these Greek texts are produced by comparing the existing ancient manuscripts to try and determine what the original text would have been; a process known as textual criticism. These texts, like the Nestle-Aland, are used by most of the modern English translations such as the NASB, the NIV, the CSB and the ESV. These more modern Greek texts generally give more weight to the Alexandrian manuscripts than they do to the Byzantine manuscripts. While the rationale is debated, it is generally felt the the older manuscripts are more reliable. So even though there are vastly more of the more recent manuscripts, the fewer but older manuscripts carry more weight in the translation process. Differences in the Manuscript Families I grew up reading the KJV and was rather shocked when I started reading the NIV; discovering that familiar passages in the KJV were either missing or relegated to footnotes in the NIV. And I know that I am not alone in the confusion that this causes. It is common for those who advocate the KJV to accuse the more modern translators of intentionally removing critical passages from the Bible. But the reality is that some passages, like the ending of Mark and the story of the woman caught in adultery are simply not found in the oldest manuscripts. They would appear not to be a part of the original text, but were something added by scribes during the copying process of the Byzantine manuscripts. But it worth pointing out that none of these additions/subtractions have any real impact on the doctrine of the church. Whether you use the KJV or the NIV, the doctrine it contains is the same. Format When I became a Christian nearly 50 years ago the only choice I had for reading the Bible was to either purchase a printed copy, or invest in a box of tapes and listen to someone read it to me. But that has changed recently. Digital Bibles have become very popular. I frequently read the Bible on my laptop, my Kindle and my phone. And most of my study happens on one of those devices. No matter where I am, I have access to my Bible. And not just a single translation. I have half a dozen different translations on my phone, and many more available if I have an internet connection. On-line Bibles I have found two different types of digital Bible. One is the online Bible. I primarily use Bible Gateway for this. There is a large number of translations to choose from, in a variety of languages. It is easy to search for passages, words, and expressions. And it's basic functionality is free. There are also a large number of study aids available for a modest subscription. The primary downside to it is that it requires an internet connection. If you are traveling, or otherwise disconnected, it is not available. Installed on Your Device The other format is one that is installed directly on you digital device. I use Olive Tree, although there are a number of other sources. This format has the advantage of always being available, but many of the translations and other resources have a one time cost associated with them. Most of the translations, and some of the resources are inexpensive; but some are quite pricey. What I like most about this, besides being always available, is that it is easy to share notes and highlights across devices. The notes I take on my laptop are available when I am out in the mountains, and vice versa. The Downside There is one major problem I have with on-line Bibles. And it is purely a personal one. I find it less convenient to put my finger on a page and then explore supporting passages. It is certainly doable with on-line Bibles. But I find it much easier with a printed copy. I suspect that has more to do with my age than anything. It is how did it for many years prior to the advent of digital Bibles. And it is what I am comfortable with. But that does not prevent me from using on-line Bibles extensively. Without question I spend more time on phone / kindle / laptop reading and studying than I do with a printed copy. Resources One of the issues that you might face with specific translations is the availability of study aids. Most commentaries, concordances and other study tools are either tied to a specific translation, or are referencing one. For commentaries that is not generally a big deal. But it is for concordances and dictionaries. Because of the great amount of effort involved in producing a printed concordance, they are only available for a limited number of translations. The KJV probably has the largest number of printed references, simply because it has been around the longest and has a large following. The NIV also has quite a number of specific study tools, but others will be lacking in this area. But, when using digital Bibles, the need for a printed concordance pretty much goes away. You will be able to search for words, or expressions, across any Bible that you have available. A Word About Study Bibles There are also a number of what are called 'Study Bibles'. These Bibles have commentary or other study notes built into them. These work well for many people. But I am not overly fond of them. I have found that it is sometimes hard to recognize the difference between the actual Scripture, which is God-breathed, and the associated notes, which are not. Just because they are side by side does not give them equal weight. If you use a Study Bible, please make every effort to observe that distinction. Recommendation So which English translation of the Bible should you use? In the end, I don't believe it matters all that much for our general reading and study efforts. Apart from those produced by the Jehovah's Witnesses, or others, to promote a specific non-orthodox theology, they are all good. The most important aspect of picking a translation is to choose one that you will read. Readability is really the most important issue. If you will not read it, or cannot understand it, then it really makes no difference how good it is. Bible Gateway is a good on-line source where you can choose from 100's of translations. Find one that is meaningful to you, and that you will read, and then use it. Over time you may find that you will change to a new translation. And you may discover than using multiple translations works well for you. But, in the end, pick the one that you will read and use it.

0 notes

Text

Dedication Is What You Need

Visit Now - https://zeroviral.com/dedication-is-what-you-need/

Dedication Is What You Need

It is not often that actual history and Showtime’s TV series The Tudors are in agreement. Yet one scene depicts a very small event that may have actually happened, as part of a much larger 16th-century tradition of patronage and gift giving. In it, Thomas Culpepper presents Catherine Howard with a folio-sized book as part of the New Year’s celebrations. The book – the first book on midwifery to be written in English – was the work of Richard Jonas, a man who came to England in the train of Anne of Cleves. Jonas meant to dedicate the book to Anne, but would now like to dedicate it to Catherine instead. Culpepper explains that Jonas would like to dedicate it to ‘the most gracious and in all goodness most excellent virtuous lady Queen Catherine’.

In 1540, Richard Jonas did in fact dedicate his The Byrth of Mankynde to Catherine Howard, using the exact language quoted in the scene, but there is no evidence that she ever saw it or owned a copy. Dedications to manuscript and printed books are a small aspect of book history, but are surprisingly powerful evidence of a way in which Englishmen and women grappled with some of the most important issues of the time. Beyond simple appeals for patronage, book dedications can offer evidence for why an author or translator chose to produce a text, the sources they used for it, how that text came to be published, why it was relevant to the current political or religious situation and how dedicators chose to offer veiled counsel to their dedicatees.

There are no dedications that embody the complicated and symbiotic relationships of dedicators and dedicatees better than those to the five Tudor monarchs. Between them, the monarchs and their spouses received innumerable manuscript dedications and, as printed books gradually replaced manuscripts, at least 300 printed book dedications. While dedicatees may not have had a say in how their name was invoked and the dedications cannot tell us about, for example, the personal reading habits of Elizabeth I, dedications linked a text with a royal person. This connection gave a text authority and a commercial appeal, while at the same time suggesting to the monarch a text that he or she should read, support and learn from.

While the subject matter of dedicated books varied by monarch, there are some overarching generalities that dedications to the Tudors shared. While they were heirs, each of the Tudors received very few dedications. An important motivation for giving a book a dedication was the expectation of receiving something in return and an heir was unlikely to have the power to dispense patronage in the same way as the reigning monarch.

Dedications are evidence of how authors and translators appealed to and railed against the monarchs to make decisions, take counsel and educate themselves and their children. The court musician and tutor Giles Du Wes, for example, dedicated a French textbook to Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, Princess Elizabeth and Lady Mary that contained lessons that had previously been written for Mary during her time in the Welsh Marches. Similarly, the Valencian scholar Juan Luis Vives dedicated a book of mottos (resembling a mirror for princes) to Princess Mary, which was later also used in the educations of Elizabeth and Edward.

The evidence suggests that giving book dedications to a monarch became more popular over the course of the 16th century: there are just 20 extant print and manuscript book dedications for Henry VII, but 183 printed dedications to Elizabeth.

There were further differences between dedications to the monarchs beyond the number of dedications given. Henry VII mainly received printed book dedications from men who already received his patronage, suggesting that, with print as a new industry, no one was quite sure how the monarch would respond to a printed book as opposed to a personalised manuscript. Mary received several more personalised dedications in manuscripts than did her grandfather, because she established personal relationships with many authors and translators who gave them to her for patronage. Robert Recorde, in his The Castle of Knowledge, praised Mary’s piety and learning, while at the same time asking her to support his text:

Godde in despite of cancred malice and of frowninge fortune, dyd exaulte your maiestie to that throne royall, whiche of iustice dyd belonge vnto your highness, althoughe the musers of mischief wrought muche to the contrary.

Henry Parker, Lord Morley, in support of Mary’s often-changing situation at court, wrote a dedication added to a medieval manuscript so that she would keep and protect at least one religious manuscript during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, making a point to note ‘specially in that this is Catholyke’. Interestingly, some men who dedicated to Mary also made dedications to her father and half-siblings, indicating that, for some, receiving patronage was a way of life. The translator Thomas Paynell was one such man, able to survive on patronage through multiple Tudor reigns, dedicating to Henry VIII, Mary and Elizabeth.

As for Elizabeth, it is unsurprising that, having ruled the longest of all of the Tudors, she received the most dedications of the widest range of subject. A complete list of manuscripts dedicated to Elizabeth has not yet been compiled, but the sheer number of printed books alone indicates that by the second half of the 16th century more people than ever before were willing to offer their monarch gifts, that Elizabeth was known to be a patron of the arts and that print in England was becoming easier and cheaper to produce – from paper-making, to printing, to textual production.

Although book dedications are a minor aspect of early modern book culture, as both a tradition and individually they offer unexpected insight into the politics and personal intrigues of the literary culture of Tudor England.

Valerie Schutte is the author of Mary I and the Art of Book Dedications (Palgrave, 2015).

0 notes

Text

Manuscripts of The Bible and Textual Criticism

The Bible is a collection of ancient manuscripts of the original texts passed down through history. Scholars gather, compile, translate, research and compare all discovered manuscripts and support texts to determine the original biblical texts. This article will discuss an overview of biblical manuscripts and textual criticism; we will explain a brief overview of what Textual Criticism is, creation of source documents to recreate a document that closest resembles the original, what actual biblical manuscripts we currently have to study, and what source documents current bible translations depend on. MANUSCRIPT AVAILABILITY = INCREASED RELIABILITY First, we need to understand the vastness of Biblical Manuscripts compared of other non biblical ancient documents. The Greek Philosopher Plato, for example, lived around 427 BC and lived to be about 80 years old. THE oldest surviving manuscript is dated to around 895 AD. That is over a 1,200 year gap from author to current manuscript. It is volume one of two, the second of which has not been discovered. Let us also consider the manuscripts of Julius Caesar. The oldest account of what Caesar said and did comes from Roman Historians in the 2nd century, 100 years after Caesar, BUT the oldest copy of their manuscripts are 900 years or later from the authors, AND only 12 total manuscripts exist. In school, did you ever question the historical reliability of Plato and Julius Caesar? Now, lets consider Biblical Manuscripts and their dating. John Rylands Fragment, which contains John 18:31-33, 37-38, is originally dated to 96 AD. This is only 60 years after Jesus walked the earth. The probability that this could be a copy of The Apostle John's original is plausible. The fragment itself is dated to around 120AD. Only 30 years after John and 90 years after Jesus is the actual copy we have today. The Bodmer Papyrus is originally dated around the 70s AD, 40 years after Jesus and while some of the Apostles were still alive. The papyrus itself is dated to the end of the 2nd century, putting that exact manuscript that we have in our hands within only 130 years from Jesus and the Apostles. Now, comparing these examples from secular manuscripts with biblical manuscripts we see something very important:

Plato: 1,200 years after the author

Caesar: 900 years after the author

The Gospel of John: 60-90 years after Jesus, and 0-30 years after John.

Let us also look at the number of manuscripts we have discovered.

Plato (all of his known writings): 250 manuscripts, some in question.

Caesar (all of his known writings): 12 manuscripts, some extremely late and questionable.

The Bible: 5,800 manuscripts before the printing press. Some are late and questionable.

Understandably, Caesar did not write volumes like Plato or biblical authors. But, when comparing volume verses volume of Plato and The Bible we see a HUGE difference. There are 5,550 MORE manuscripts of the Bible than there are of Plato and his discovered manuscripts. The importance of this we will get to later. Thus, we can see that Biblical Textual Criticism can be more reliable than that of secular ancient texts. Because of the closeness to authorship and the vast amount of manuscripts; we have a more accurate deduction of the original texts can be made.

BRIEF UNDERSTANDING OF GENERAL TEXTUAL CRITICISM

SYSTEMATIC TEXTUAL CRITICISM When investigating the New Testament manuscripts it is important that each manuscript is organized in its relation to date of creation and its relation to other manuscripts. a systematic approach introduced in 1981 by Kurt and Barbara Aland organized biblical manuscripts by 'text type'. A Text-type is organizing manuscripts based on their similarities and putting them into a family of text. Word usage, key words and phrases, location, and outside witnesses can identify what family the text belongs to. When evaluating a family or Text-type, textual critics and then better determine the source of that family. CONSIDERING THE EVIDENCE External evidence of each physical witness, its date, source, and relationship to other known witnesses help in determining its family type. Critics will often prefer the readings supported by the oldest witnesses. Since errors tend to accumulate, older manuscripts should have fewer errors. Readings supported by a majority of witnesses are also usually preferred, since these are less likely to reflect accidents or individual biases. Internal evidence that comes from the text itself, independent of the physical characteristics of the document. Shorter readings are general observations that the scribes/copyists tended to add words, for clarification or out of habit, more often than they removed them. Harder readings recognizes the tendency for harmonization or resolving apparent inconsistencies in the text. Applying this leads to taking the more unharmonized reading as being more likely to be the original. The critic may also examine the other writings of the author to decide what words and grammatical constructions match his style. The evaluation of internal evidence also provides the critic with information that helps him evaluate the reliability of individual manuscripts. Sentence structure, punctuation, word spelling, word usage, and specific details help date when the original or manuscript was written. Older greek manuscripts were written in upper case letters. Later greek manuscripts were written in lower case letters. Also handwriting practices changed; in Greek texts after the year 900 AD, scribes began to increase the use of ligatures in which they began to connect two or more characters much like cursive. Some will detail historic events in present or past tenses which points to a specific time period of authorship. Others will leave out extremely important historic events that would relate to the authors subject; which points to the authorship before the event occurred. Considering all these factors in the manuscript, scholars can be confident in a date range of the writing and its original source. Finding errors can also help in determining the original of a family of texts. The principle that "community of error implies community of origin." If two witnesses have a number of errors in common, it may be presumed that they were derived from a common intermediate source, called a hyparchetype. COMPILING A SOURCE DOCUMENT Variations in the texts exist and what one omits, the others may retain; what one adds, the others are unlikely to add. Eclecticism allows inferences to be drawn regarding the original text, based on the evidence of contrasts between witnesses. The result of this Eclecticism process is a text with readings drawn from many witnesses. It is not a copy of any particular manuscript, and may even deviate from the majority of existing manuscripts. In a purely eclectic approach, no single witness is theoretically favored. Instead, the critic forms opinions about individual witnesses, relying on both external and internal evidence. The critic can then proceed to the selection step, where the text of the archetype is determined by examining variants from the closest hyparchetypes to the archetype and selecting the best ones. If one reading occurs more often than another at the same level of the tree, then the dominant reading is selected. After evaluating all related family text types and their variants and supporting evidences, the critic then can compile the hyparchetype into a source document, or a archtype that matches the original.

(image from CARM.org)

BIBLICAL MANUSCRIPTS

THE OLD TESTAMENT

Dead Sea Scrolls: These ancient scripts of the OT were written around 150 BC to 70 AD. It contains an impressive complete Isaiah scroll and a large number of Psalms manuscripts. In all, they contained manuscripts of 29 OT books of the current bible.

The Septuagint is a Greek version of an early OT bible. This specific translation quoted a number of times in the New Testament, particularly in Pauline epistles, and also by the Apostolic Fathers and later Greek Church Fathers. We know this from the wording of the quotes. The title in greek μετάφρασις τῶν Ἑβδομήκοντα, means "The Translation of the Seventy" and its symbol is LXX which refers to the seventy Jewish scholars who solely translated the Five Books of Moses into Koine Greek as early as the 3rd century BC. Translations of the Torah into Koine Greek by early Jewish Rabbis have survived as rare fragments only. Pre-Christian Jews such as Philo and Josephus considered the Septuagint on equal standing with the Hebrew text. Manuscripts of the Septuagint have been found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, and were thought to have been in use among Jews at the time. The New Testament writers, when citing the Jewish scriptures, or when quoting Jesus doing so, freely used the Greek translation, implying that Jesus' Apostles and their followers considered it reliable. Later in its history, the Septuagint was widely used by the new Christian sect and thus, the Jewish authority began to denounce its use. They then re-translated the OT in a Hebrew, of which, most new Jewish-Christian converts were not able to read. Irenaeus stated that, concerning Isaiah 7:14, the Septuagint clearly writes of a virgin (Greek παρθένος, bethulah in Hebrew) that shall conceive, while the word almah in the Hebrew text was, according to Irenaeus, at that time interpreted by Theodotion and Aquila (both devout in the Jewish faith) as a young woman that shall conceive. According to Irenaeus, the Ebionites used this to claim that Joseph was the (biological) father of Jesus. From Irenaeus' point of view that was pure heresy, facilitated by (late) anti-Christian alterations of the scripture in Hebrew, as evident by the older, pre-Christian, Septuagint. This shows the later change of the Hebrew writings contradicting the older, pre-Christian, OT Greek translation. The LXX is comprised of: 2nd century BC fragments of Leviticus and Deuteronomy. 1st century BC fragments of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, and the Minor Prophets. Relatively complete manuscripts of the LXX postdate the Hexaplar rescension and include the Codex Vaticanus from the 4th century AD and the Codex Alexandrinus of the 5th century. The oldest extant complete Hebrew texts date some 600 years later, from the first half of the 10th century. The 4th century Codex Sinaiticus also partially survives, still containing many texts of the LXX Old Testament.

The Peshitta was translated into Syriac from Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century AD, and that the New Testament of the Peshitta was translated from the Greek. Earliest manuscript, designated as "5b1", which is dated to the second half of 5th century. The manuscript includes only Genesis, Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy, and the text is more similar to the Masoretic Text. The Codex Ambrosianus designated as "7a1", dates from the 6th or the 7th century, and includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible. Syr. 341 designated as "8a1", dating from the 8th century or prior with many corrections, it includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible.

The Vulgate is a late 4th-century Latin translation of the Bible. The translation was largely the work of St Jerome, who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Vetus Latina ("Old Latin") Gospels then in use by the Roman Church. Jerome, on his own initiative, extended this work of revision and translation to include most of the Books of the Bible. Dating from the 8th century, the Codex Amiatinus is the earliest surviving manuscript of the complete Vulgate Bible. The Codex Fuldensis, dating from around 545, contains most of the New Testament in the Vulgate version. The Codex Cavensis is a 9th-century Latin Bible.

The Masoretic Text designated as MT, 𝕸, or M {\displaystyle {\mathfrak {M}}} is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the Tanakh for Rabbinic Judaism. But many OT manuscripts older than the Masoretic text and often contradict it. The oldest extant manuscripts of the Masoretic Text date from approximately the 9th century AD. The Aleppo Codex dates from the 10th century. The Nash Papyrus (2nd century BC) may contain a portion of a pre-Masoretic Text. It runs into discrepancies when compared to the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Septuagint, both of which predate The Masoretic text. Not nearly as many manuscripts exist as of the New Testament but quite a lot is know of what the original text meaning is. Though there are variants in the different manuscripts, almost all of the textual variants are fairly insignificant and hardly affect any doctrine. Professor Douglas Stuart states: "It is fair to say that the verses, chapters, and books of the Bible would read largely the same, and would leave the same impression with the reader, even if one adopted virtually every possible alternative reading to those now serving as the basis for current English translations." NEW TESTAMENT The New Testament manuscripts are categorized in 5 'families'. Category I – Alexandrian, Category II – Egyptian, Category III – Eclectic, Category IV – Western, and Category V – Byzantine.

Alexandrian Text-type: The Alexandrian text-type is the form of the Greek New Testament that represents the earliest surviving manuscripts. The oldest, near complete manuscript is The Codex Vaticanus and is dated around 300 AD. the Codex Vaticanus originally contained a virtually complete copy of the Septuagint. The Codex Sinaiticus is also of the Alexandrian family and is dated around 330 to 360AD. It originally contained a virtually complete copy of the Septuagint Which are different from the far later Textus Receptus generated by Erasmus. The Codex Alexandrinus dated around 400AD.

A number of substantial papyrus manuscripts of portions of the New Testament survive. The earliest translation of the New Testament into an Egyptian Coptic version — the Sahidic of the late 2nd century — uses the Alexandrian text as a Greek base. The Chester Beatty II and Bodmer II are dated to the 2nd Century. Bodmer VII, VIII, XIV and XV are dated to the 3th century. Considering these earliest manuscripts and the Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus, and Codex Alexandrinus, not to mention late 1st through 5th century quotes from early church teachers; the new testament message can be compiled from manuscripts no later than the 5th century.

The Western text-type is the predominant form of the New Testament text witnessed in the Old Latin and Peshitta translations from the Greek, and also in quotations from certain 2nd and 3rd-century Christian writers, including Cyprian, Tertullian and Irenaeus. This text type often presents longer variants of text, but in a few places. Papyrus 37, 48, Papyrus Michigan, Oxyrhynchus XXIV are dated to the 3rd century. 0171, Codex Bezae, and some portion of Codex Sinaiticus are Western type dated to the 4th century. Codex Washingtonianus is dated to the 5th century and Codex Claromontanus is dated to the 6th century. Compared to the Byzantine text-type distinctive Western readings in the Gospels are more likely to be abrupt in their Greek expression. Compared to the Alexandrian text-type distinctive Western readings in the Gospels are more likely display glosses, additional details, and instances where the original passages appear to be replaced with longer paraphrases. Although the Western text-type survives in relatively few witnesses, some of these are as early as the earliest witnesses to the Alexandrian text type. Nevertheless, the majority of text critics consider the Western text in the Gospels to be characterized by periphrasis and expansion; and accordingly tend to prefer the Alexandrian readings.

The Byzantine text-type is the form found in the largest number of surviving manuscripts, though not in the oldest. While considerably varying, it is the basis for the Textus Receptus Greek text. The earliest Church Father to witness to a Byzantine text-type in substantial New Testament quotations is John Chrysostom (c. 349 — 407). The second earliest translation to witness to a Greek base conforming generally to the Byzantine text in the Gospels is the Syriac Peshitta. Although in respect of several much contested readings, such as Mark 1:2 and John 1:18, the Peshitta rather supports the Alexandrian witnesses. The Ethiopic version of the Gospels; best represented by the surviving fifth and sixth century manuscripts of the Garima Gospels and classified by Rochus Zuurmond as "early Byzantine". Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus is majority Byzantine, Codex Guelferbytanus B, and Uncial 061 are dated around the 5th century. Codex Basilensis is dated in the 8th century. Codex Boreelianus, Codex Seidelianus I and II, Codex Angelicus, Codex Mosquensis II, Codex Macedoniensis, Codex Koridethi, Minuscule 1424, and Codex Vaticanus 354 are dated to the 9th century. Minuscule 1241 is dated o the 12th century. The Byzantine readings tend to show a greater tendency toward smooth and well-formed Greek, they display fewer instances of textual variation between parallel Synoptic Gospel passages, and they are less likely to present "difficult" issues of exegesis. For example, Mark 1:2 reads "As it is written in the prophets..." in the Byzantine text; whereas the same verse reads, "As it is written in Isaiah the prophet..." in all other early textual witnesses. In that instance, what is being quoted is from Isaiah but also from Malachi. Thus; the Byzantine witness tends to change the wording for a fuller understanding. The explanation of the wide spread later use of the Byzantine text-type can be explained when Constantine I paid for the wide distribution of manuscripts which came from the group of church teachers who came together to generate a source document of older manuscripts. There are several references by Eusebius of Caesarea to Constantine paying for manuscript production.

An example of the actual texts and translations of John 18:32:

John Rylands Papyrus 457, P52 - 125AD

"so that the word of Jesus might be fulfilled, which he spoke signifying what kind of death he was going to die."

ΙΝΑ Ο ΛΟΓΟΣ ΤΟΥ ΙΗΣΟΥ ΠΛΗΡΩΘΗ ΟΝ ΕΙΠΕΝ ΣΗΜΑΙΝΩΝ ΠΟΙΩ ΘΑΝΑΤΩ ΗΜΕΛΛΕΝ ΑΠΟΘΝΗΣΚΕΙΝ

(The words underlined and in bold are what are stated in this fragment)

Codex Sinaiticus - 330 to 360AD

"that the word of Jesus might be fulfilled, which he spoke signifying by what kind of death he was about to die."

να ι ουδενα ϊνα ο λογοϲ του ιυ πληρωθη ┬ ϲημαινω ποιω θανατω ημελλεν αποθνη

(http://ift.tt/2vD6iOz)

Textus Receptus - 1500AD - 1600AD

"That the saying of Jesus might be fulfilled, which he spake, signifying what death he should die."

ἵνα ὁ λόγος τοῦ Ἰησοῦ πληρωθῇ ὃν εἶπεν σημαίνων ποίῳ θανάτῳ ἤμελλεν ἀποθνῄσκειν

(http://ift.tt/2hzaSHo) (http://ift.tt/2vCDhlT) Spanning over 1,475 years, and yet, they literally say the same thing. The Byzantine Text-type (Textus Receptus) also continues the same message, 1,475 years later. This is not even considering the thousands of other manuscripts and comparing all of them. The Diagram below simplistically illiterates this:

(The image above is a basic and simplified example of how to determine an archetype of the original document based on witness sources)

COMBINED SOURCE DOCUMENTS

Combining the Greek family of manuscripts into a single document is what came next. In 1516 the Novum Instrumentum omne was published. Compiled by Erasmus and using Byzantine Text-type as its primary source it was a foundational document for early church translations which later generated the King James bible.

The Institute for New Testament Textual Research reconstructed its Greek initial text on the basis of the entire manuscript tradition, the early translations and patristic citations; furthermore the preparation of an Editio Critica Maior based on the entire tradition of the New Testament in Greek manuscripts, early versions and New Testament quotations in ancient Christian literature. This source document from the INTF is called the Novum Testamentum Graece and refers to the Nestle-Aland editions of the translated source document and is currently in its 28th edition, abbreviated NA28 of which the United Bible Societies (UBS) also uses. The critical text is an eclectic text compiled by a committee that examines a large number of manuscripts in order to determine which reading is most likely to be closest to the original. A new massive Textual Criticism project is underway by the INTF. Editio Critica Maior (ECM) is a critical edition of the Greek New Testament being produced. They acquired over 90% of the known biblical material on microfilm or photo. The project Editio Critica Maior is supported by the Union of German Academies of Sciences and Humanities. It is to be completed by the year 2030. The International Greek New Testament Project (IGNTP) began in 1926 as a cooperative enterprise between British and German scholars to establish a new critical edition of the New Testament. The project was resurrected in 1949 as a cooperative endeavour between British and North American scholars. British and North American cooperation resulted in the publication of a critical apparatus for the Gospel of Luke in the 1980s. Current research focuses on the Gospel of John, and the surviving majuscule manuscripts have been published in print and electronic form. The present committee comprises scholars from Europe and North America.

The Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, abbreviated as BHS, is an edition of the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible as preserved in the Leningrad Codex, and supplemented by masoretic and text-critical notes. The Eastern Orthodox Bible (EOB) (in progress) is an extensive revision and correction of Brenton's translation which was primarily based on Codex Vaticanus. Its language and syntax have been modernized and simplified. It also includes extensive introductory material and footnotes featuring significant inter-LXX and LXX/MT variants.

(The images above do not show each and every biblical witness but gives a simple and basic overview of how the documents were transmitted)

TEXTUAL BASIS FOR BIBLE VERSIONS

Dead Sea Scrolls - OT, 200BC - 70AD

The Septuagint - OT & NT, 200BC - 400AD

The Peshitta - OT, 100AD - 600AD

The Vulgate - OT & NT, 400AD - 800AD

The Masoretic Text - OT, 800AD - 1000AD

Alexandrian Text-Type - NT, 100AD - 400AD

Western Text-Type - NT, 100AD - 400AD

Byzantine Text-Type - NT, 400AD - 1100AD

Textus Receptus - NT, 1500AD - 1600AD

These 9 canonical manuscripts and fragment manuscript families of more than 25,000 total manuscripts are then compiled and translated into a single source document reflecting the archtype of the originals.

Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia - OT - Masoretic Text of the Leningrad Codex. Biblia Hebraica Quinta is the 5th edition projected completion in 2020.

Novum Instrumentum omne (Textus Receptus) - NT - Byzantine Text-type primary, Latin Vulgate, Codex Montfortianus gap.

Novum Testamentum Graece (Nestle-Aland editions) - NT - Alexandrian Text-Type primary, Western Text-Type gaps.

United Bible Societies (UBS) edition - NT - Alexandrian Text-Type primary.

Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople 1904 Text - NT - Textus Receptus primary, Byzantine Text-type gaps.

From these combined archtype source documents, Bible versions are then translated and printed in common languages. There are different types of publication methods. Word for Word translations (formal), thought for thought (dynamic), paraphrased, or a methodical blend.

New American Standard Bible (NASB) - Word for Word - NT: Nestle-Aland edition. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia with Septuagint influence.

King James Versions (KJV) - Word for Word - NT: Textus Receptus. OT: Masoretic Text with Septuagint influence.

English Standard Version - (ESV) - Word for Word- OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia with Septuagint influence Deutero./Apoc.: Göttingen Septuagint, Rahlf's Septuagint and Stuttgart Vulgate. NT: Nestle-Aland edition, supplemented by Textus Receptus.

New International Version (NIV) - Blend of word for word and thought for thought - NT: Nestle-Aland edition. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, Masoretic Hebrew Text, Dead Sea Scrolls, Samaritan Pentateuch, Latin Vulgate, Peshitta, Aramaic Targums, for Psalms Juxta Hebraica of Jerome.

New Living Translation - (NLT) - Blend of word for word and thought for thought - NT: UBS 4th revised edition and Nestle-Aland edition. OT: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, with some Septuagint influence.

(KJV) (NASB) (NIV) There are about 5,800 Greek manuscripts, 10,000 Latin manuscripts and 9,300 manuscripts in various other ancient languages including Syriac, Slavic, Ethiopic and Armenian of the New Testament. Professor D. A. Carson states: "nothing we believe to be doctrinally true, and nothing we are commanded to do, is in any way jeopardized by the variants. This is true for any textual tradition. The interpretation of individual passages may well be called in question; but never is a doctrine affected." EP Sanders, Arts and Sciences Professor of Religion at Duke University, who himself is nonchristian and open secular historian honestly stated: "Historical reconstruction is never absolutely certain, and in the case of Jesus it is sometimes highly uncertain. Despite this, we have a good idea of the main lines of his ministry and his message. We know who he was, what he did, what he taught, and why he died. ….. the dominant view [among scholars] today seems to be that we can know pretty well what Jesus was out to accomplish, that we can know a lot about what he said, and that those two things make sense within the world of first-century Judaism." All this, he concludes, comes from the vast amount of manuscripts and evidence of the bible. Some of the actual photo copy of manuscripts can be viewed and studied at:

codexsinaiticus.org

http://ift.tt/2fi5Fmw

http://ift.tt/1K2NgPI

http://ift.tt/rpPRw9

http://ift.tt/1XkwV1q

Conclusion To claim that we can not know what the original text said is to then discredit every ancient historical writing ever written about anyone from Alexander The Great to Plato to Julius Caesar himself. The fact is there is vast amounts of hard proof and outside evidences that lead even secular historians to admit that we can know details about ancient persons, including Jesus and ancient Israel. Christians who doubt and nonchristians who discredit do so because of willful ignorance of current evidences. We CAN know and we do know, because God has allowed us to know, through preserving what he has preserved; found in the 25,000 hard copy manuscripts we have today and the vast amount of outside biblical support and evidences as well. Also read Did the Apostles distort what Jesus taught? | Modern Secular Historians and The Bible | Early Accounts of Christianity from Non-Christians | Why The Disciples of The Apostles Matter Today | Apologetics main page If you have any questions or comments about this article please contact us or join our discussion forms

from Blogger http://ift.tt/2vCZ5hi

0 notes

Link

var h12precont = 'h12c_300x250_' + Math.floor(Math.random()*1000000); document.write(' <div id="' + h12precont + '">'); (h12_adarray = window.h12_adarray || []).push({"adcontainer":h12precont,"placement":"c9d6b99f00114c5a436a0f497c7bb182","size":"300x250","type":"standard","width":"300","height":"250","name":""}); </div>

Googling “mysterious historical discoveries” or “unexplained historical innovations” results in dozens of websites itemizing artifacts supposedly so baffling the one potential reply may very well be aliens, time journey, the paranormal, the Iluminati, or aliens. Wait – did we already point out aliens? Sorry: they’re a go-to clarification for something apparently too refined, bizarre, or “out-of-place” for “people figured it out, okay?” to be a satisfying clarification.

It’s a disheartening discovery, as a result of when you separate the hoaxes and nonsense from the finds of precise archeological curiosity, there are nonetheless cool mysteries to discover. The listing beneath options mysterious historical innovations, unexplained historical discoveries, and a few barely newer finds nonetheless baffling to scientists within the 21st century – however not as a result of they’re an indication of alien tech. Give humanity just a little extra credit score, y’know?

Lethal “Greek Hearth” Was a Household Secret

Photograph: Public Area/via Wikimedia

It’s not like anybody is aching for napalm to make a comeback, however scientists and historians are nonetheless very curious about Seventh-century “Greek Hearth,” a lethal proto-napalm fired from ships that “would cling to flesh and was unattainable to extinguish with water.” Feels like a nightmare!

The Byzantine Empire wielded it with aplomb, however, like Coca-Cola Traditional and Bush’s Baked Beans, the recipe for Greek Hearth was a protected household secret. Nationwide Geographic pulled a Mythbusters and took a guess on the elements in 2002, utilizing a “bronze pump” and a “combination of sunshine crude oil and pine resin.” The outcomes? It destroyed a ship “in minutes.” Good guess!

The Recipe for Damascus Metal Stays a Thriller

Photograph: Public Area/via Wikimedia

Getting back from the Crusades, quite a lot of perplexed Europeans began speaking about swords wielded by Islamic warriors “that would slice by means of a floating handkerchief, bend 90 levels and flex again with no harm.” Quick-forward to the 21st century and the recipe for so-called “Damascus steel” is nonetheless a thriller. The blades had been probably manufactured from “crucible metal,” which is created by melting iron with plant matter, however nobody is aware of the particular sort of crucible metal used to yield such a blade. It’d as properly be a lightsaber.

The Voynich Manuscript Could In the end Simply Be Indecipherable

Photograph: Public Area/via Wikimedia

Should you haven’t heard of the Voynich Manuscript, you’re in for a deal with. Researchers say the completely bonkers, hand-written and hand-drawn manuscript, that includes textual content in an indecipherable language and a whole lot of illustrations together with “a myriad of drawings of miniature feminine nudes, most with swelled abdomens, immersed or wading in fluids and oddly interacting with interconnecting tubes and capsules,” was created by somebody someday through the 15th century in Central Europe. A Polish-American antiquarian bookseller named Wilfrid M. Voynich acquired it in 1912. Apart from that, who is aware of? It’s a complete thriller.

If it’s presupposed to imply something or assist folks perceive something, it has failed miserably. That stated, it is among the few real mysteries on the market. Do your self a favor: leap down the Voynich rabbit hole. Simply don’t blame Ranker if you happen to lose your thoughts just a little.

The Antikythera Mechanism Is a Mysterious Astrological Calendar

Photograph: Marsyas /via Wikimedia

Not like the Roman dodecahedra, scientists have a pretty good idea what the so-called Antikythera Mechanism is all about. Found on the backside of the ocean in 1901, the intricate gadget was probably constructed across the finish of the second century BC. It “calculated and displayed celestial info, notably cycles such because the phases of the moon and a luni-solar calendar,” in keeping with analysis compiled in Nature.

However we nonetheless don’t know who constructed it, who used it, and what they used it for, precisely. It’s additionally nonetheless unclear why it’s “technically extra advanced than any recognized gadget for no less than a millennium afterwards,” to cite the Nature summary, which prompted a zillion “historical aliens” and “TIME TRAVEL IS REAL!!” weblog posts after it was revealed in 2006.

However historical past, as Brian Dunning of Skeptoid notes, tells us related gear-based know-how was round two and a half millennia prior, and Occam’s Razor tells us any “siblings” of the Antikythera Mechanism, like most commonplace bronze objects of the interval, had been probably “recycled” into different objects. It’s nonetheless mysterious, only for much less horny causes than some may suppose.

Zhang Heng’s Seismoscope Detected Earthquakes (Someway)

Photograph: Kowloonese/via Wikimedia

The primary earthquake-detecting instrument in historical past was this ornate, golden, dragon-festooned, toad-surrounded vessel from round 132 AD. The image is of a reproduction, however you get the thought, proper? No? Okay, right here’s the idea: when the earth quakes, one of many dragons, every representing principal instructions of the compass, would spit out a ball right into a toad’s mouth, indicating the route of the quake. The instrument was stated to have “detected a four-hundred-mile distant earthquake which was not felt on the location of the seismoscope.” Both that, or somebody bumped up in opposition to it, as a result of to this present day, nobody truly is aware of what was actually contained in the factor. (Extra dragons, possibly?) Some say it may have been a easy pendulum-based system, however the actual “science” stays a thriller.

It’s Unclear How Vikings Made Their Ulfberht Swords

Photograph: Anders Lorange/via Wikimedia

Talking of insane swords – the Vikings could have used strategies or supplies borrowed from the creators of Damascus metal to make their legendary “Ulfberht” swords. When archeologists found the Viking blades, they had been shocked as a result of “the know-how wanted to provide such pure metallic wouldn’t be invented for an additional 800 years.” However in 2014, a Ninth-century Viking grave was found in Scandanavia with an Islamic inscription that means “for/to Allah,” linking the 2 worlds and making the shared data believable – however that’s only a guess. The true origin of the blades continues to be unknown.

Scientists Disagree About Why the Iron Pillar of Delhi Received’t Rust

Photograph: Imahesh3847/via Wikimedia

The more-than-1600-year-old “Iron Pillar of Delhi” has scientists divided about its bizarre resistance to rust. There are two faculties of thought: Workforce Setting says the gentle local weather of Delhi, India, is in the end to thank. Proper place, proper time, basically. Workforce Supplies says it’s all concerning the “presence of phosphorus, and absence of sulfur [and] manganese within the iron,” plus the “giant mass of the pillar.” One factor each camps agree on? It’s a complete thriller how the rust-resistant iron lumps had been “forge-welded to provide the huge six-ton construction.” Regardless, it’s a spectacular piece of engineering.

The Phaistos Disk May Be a Prayer or an Historic Typewriter

Photograph: C messier/via Wikimedia

This large sugar cookie is a head-scratcher, for certain, however there are some attention-grabbing theories on the market. Found in 1908 in Crete, this 6-inch diameter clay disk dates again to round 1700 BC and options 241 “phrases” created out of 45 particular person symbols, organized in a spiral. It may very well be a type of historical “sheet music” to a hymn or prayer devoted to matriarchal deity, or possibly it’s an ancient proto-typewriter? Who is aware of? It certain seems to be scrumptious, although.

Roman Dodecahedra Would possibly Simply Be Candlesticks

Photograph: Itub/via Wikimedia

Should you suppose these little bronze guys would make glorious paperweights or tchotchkes – properly, so did the traditional Romans, possibly? We actually have no idea. They might have been ineffective objects meant for adornment, a dialog piece for the 2nd-to-4th-century Roman equal of espresso tables.

George Hart of Stony Brook College notes dozens of those twelve-sided, 4-to-11 cm. spheroids have been discovered all through Europe, but the Romans made no mention of them. Guesses embody candle stands, flower stands, surveying devices, finger ring-size gauges, and even D&D-style cube. Possibly the traditional Romans had been pen-and-paper stylus-and-papyrus RPG lovers?

Associated

Artykuł 10 Mysterious Ancient Inventions Science Still Can’t Explain pochodzi z serwisu PENSE LOL.

via PENSE LOL

0 notes