#text: troilus and criseyde

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Operation Annihilate hurts more if you've seen Discovery because Spock does understand what it's like to lose a sibling.

I haven't seen Discovery yet, but I'll admit that my personal experience of TOS and interpretations of what it was doing with its characters and themes in the 60s are very deliberately not informed by the decades of much-later retcons of the original show. Spock in particular*, I think, has been targeted hard by retcons ever since they reset his entire character arc in 1979, and I feel like the later generations of Obligatory Spock Appearances that I have seen (in AOS and SNW) keep ever-more-drastically losing sight of what made him compelling in the first place, across a lot of different axes (including his flawless eyeshadow and narratively central homoeroticism :\).

I don't want to sound hostile or aggressive about the ask at all, though! I didn't mind receiving it, and I don't have any grievance with Discovery fans or people who do feel the need to try to reconcile all the different major Star Trek projects with each other, as long as they don't show up in TOS fans' notes to lecture us on how we've got to engage with ST their way.

I do get "well actually, in [other ST thing] it turns out" on a pretty regular basis, though, so—well, I'm only rambling further about this because I have quite a few new ST followers and want to be clear about what to expect. I'm not trying to attack anyone outside the corporate media hellscape.

I like other Treks than TOS, but I am fundamentally very opposed to the X Cinematic Universe media franchise world where every story in a setting must be perceived as part of a single consistent narrative all the other stories are hammered into, and you've got to keep up with all these different, largely independent projects to truly understand The Whole Story. I'm like, nope, Paramount/Disney/whomever isn't the boss of me, and for me, the TOS movies are kind of the Aeneid of Star Trek to TOS's Iliad, and Prodigy is, like ... uh, Troilus and Criseyde in this analogy, and otherwise, /shrug. It's like, all three texts are fantastic, and I'm intrigued by how the latter two texts talk to each other and to Homer, but they are all very, very different and I have no interest in forging a grand unified narrative of the Trojan War in my head. So it is with Star Trek for me!

I'm not only like this with Star Trek btw—I'm the same with Star Wars (and Lucasfilm is even more aggressive than Paramount about pushing every single thing as integral to The Whole Story). In general, this is just how I as a person respond to fundamentally separate storytelling projects that engage with an ostensible shared setting or shared characters or whatnot.

(I'm not really fannish about any other part of ST, so I didn't bother finding Matter of Troy analogues for TNG/etc, though I enjoy them enough in a non-fannish way.)

So anyway, all of that is to say: for my personal experience and interpretation of how TOS characterizes Spock, it's actually important to me that he really was every bit as isolated his entire life as TOS indicates, until he joined Starfleet and especially until the five-year mission.

For me, Spock's guilt over Amanda in TOS and the stakes of the fraught dynamic between them are deeply bound up in him being her only child (and not only by blood). For me, the "no bigotry on the bridge" scene in "Balance of Terror" really is the first time Spock has had a relationship with anyone who would advocate for him in that way. I see TOS Spock as the child of two parents who care about him but have always been far more preoccupied with each other and themselves, and as someone who was wholly ostracized by all his peers on Vulcan, and who even among the somewhat more welcoming humans, has been continually disrespected in very, very racialized ways.

And for me, part of the heartbreak of that Spock moment in "Operation: Annihilate!" is that TOS Spock and Kirk do have wildly different histories apart from both being bullied, and Spock has never experienced anything like this grief. Spock never had a Sam in his life, nor an Aurelan (who Kirk seems to have been close to as well), nor a Peter and the other two boys who implicitly didn't make it. Spock has spent his life fundamentally alone. But he also has never experienced the kind of horrific losses Kirk has, either—family members, immediate communities, and entire swaths of planetary populations lost, just hundreds or thousands of people ripped away over and over and over while Kirk watches or finds them afterwards.

Something important about Kirk and Spock's relationship to me, though, is that they don't have to personally experience the other's life to profoundly understand and connect to each other in the way they both desperately need. This is one of the reasons they're closer to each other than to any of their other friends or colleagues (something explicitly stated in TOS multiple times). And in S1, I think we really see that evolution with Spock in particular, where in early episodes like "The Enemy Within," he might unbend enough to say, "If I seem insensitive to what you're going through, captain, understand it's the way I am," but by the season finale, he reciprocates Kirk's accommodation of his cultural norms when it really matters.

I think TOS Spock tries to express his compassion in an emotional, human-normative way, down to the phrasing, because at this point, he prioritizes Kirk's suffering at such a time above his own values and preferences. It's more important to reach out to Kirk in Kirk's terms than to Be Vulcan About It, until Kirk needs him to be Vulcan about it. The instant that Kirk makes it clear that he can't deal with human sympathy and needs something productive to focus on, Spock instantly shifts gears to Being Useful because that's what Kirk needs from him, even when it is excruciatingly painful or risks blindness or ... really, anything.

-

*Kirk, notoriously, is also hit super hard by pop culture-filtered characterization retcons from The Wrath of Khan onwards and especially in AOS, well beyond the AU premise. But I think the subtler discomfort seen in modern ST re: TOS Spock as a masculine figure is nearly as egregious.

#astarreborn#respuestas#long post#st fanwank#c: i object to intellect without discipline#c: who do i have to be#anghraine's meta#star trek: the original series#general fanwank#sw fanwank#otp: closer than anyone in the universe#tos: s1#tos: operation annihilate#cw genocide#cw massacre#tos: the enemy within#anghraine rants#aos critical#snw critical#i also have no grievance with ethan peck personally but his spock will never inform tos spock for me. he doesn't even have chest hair :(

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

fourteenth century apology video

I was explaining the premise of Chaucer's Legend of Good Women to my son (poor kid). In its prologue, Chaucer explains how women have been attacking him for slandering the honor of women and being an enemy to love on account of his depiction of Criseyde in Troilus and Criseyde(*), and Chaucer basically says he'll make up for it by writing a book about virtuous and faithful women.

My son says to me "wait, are you saying Chaucer invented the ukulele apology video in the 1300s?!"

All the way dead. Love that kid.

(*leaving a lot out here about how problematic these texts are and how Chaucer is-- my 'fave is problematic' like they used to say)

#geoffrey chaucer#medieval literature#apology video#middle ages#14th century#medieval#mythology and folklore#romance

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crocodile tears: To display insincere sadness. A few ancient and medieval writers believed that crocodiles would cry while eating their victims.

Bring home the bacon: To earn a living or achieve success. This expression dates back to 1104 when a nobleman and his wife dressed themselves as peasants and asked the local Prior for a blessing for not arguing after a year of being married. In response, the Prior gave them a side of bacon. Afterwards, the nobleman gave land to the monastery on the condition they gave couples who accomplished the same deed with the same reward

Knock on wood: If you have good luck and want to keep it. Cosman sees this expression deriving from pre-Christian times, when people performed rites “to inspire spirits dwelling in wood or trees, such as the maypole, or to awaken them after winter slumber, as with the divinities affecting agriculture and human life.”

Hocus pocus: Doing a trick, usually said by a magician. This actually derives from words spoken in Latin during a Mass: when a priest lifted up the eucharist to his parishioners, he would say “Hoc est corpus domini,” which means “This is the body of the Lord.”

Lick into shape: To bring into satisfactory condition or appearance. In medieval bestiaries, you would find an unusual description of bears and how they give birth to their young.

On the carpet: It now means to call upon someone doing bad things. However, its origins in French (‘sur le tapis’) is that it was customary to put a carpet on a banquet table, which was often the centre of conversation.

Buckled down to work: To focus on your job. It comes from medieval warriors having to make sure their armour was buckled and safely on before going out to battle.

Out-Herod Herod: To exceed in violence or extravagance, inspired by the Biblical character. Even before it was used by Shakespeare in Hamlet, the expression could be found in medieval mystery plays.

A long spoon: To keep a safe distance from danger. Cosman notes that in medieval lore, “the best kitchen or banquet implement for supping with the Devil was a very long-handled spoon.”

Goose is cooked: When someone is in trouble. This expression has two origin stories. In one of them, it is ascribed to the Christian reformer Jan Hus when he was burned at the stake in 1415. In the other version, the 16th-century King of Sweden, Eric XIV used the phrase when he burned down a town that he was besieging after they had mocked him by putting out a goose along the walls.

Crow’s feet: A reference to the fine lines that appear around your eyes as you age. The English writer Geoffrey Chaucer is credited with first using the expression In his work Troilus and Criseyde

Food for worms: To be dead and buried. One can see this expression in the Ancrene Wisse, a thirteenth-century monastic text

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm working on a topic for the research paper in my MLIS class and it essentially boils down to me brandishing a copy of Troilus and Criseyde in one hand and As Schoolboys from their Books in the other and shouting "THESE ARE THE SAME!!!"

#hush Bree#'bree did you write this just to push your partner's fic'#...PERHAPS#it's true though#Troilus and criseyde is fanfic of earlier writings about Troy#ASFTB is fic of Yuri on Ice#functionally they are the same and my argument is that they should be treated the same (or at least similarly) archivally#I will probably not use those specific texts as examples but you get the point

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pluralizing Love in Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde

“Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde is one of the first texts in English extensively deliberating on the subject of love in the fictionalized ‘novelistic’ form of the romance: The double sorwe of Troilus to tellen,/That was the kyng Priamus sone of Troye,/In lovynge, how his aventures fellen/Fro wo to wele, and after out of joie,/My purpos is … (I.1–5)

This ‘double sorrow’, Troilus’s ‘unsely aventure’ (I.35), his ‘cas’ (I.29) of a Fortune-dependent rise and fall, is precisely taken by the narrator of the romance as the ground of deploying, debating and performing ‘love’ as a topic apt to rouse pity in the alleged hearers of the tale: ‘And for to have of hem compassioun’ (I.50).

As a consequence, love finds itself described as an uncontrolled, and uncontrollable, emotion triggering off intratextual – figural – emotions such as sadness and joy as well as extratextual – readerly – ones such as fear and pity. It is the basis of performing passion. In the romance, ‘love’ is first introduced through an object of perfection.

Following the idea of the divine ideal, Criseyde is described by the narrator as some heavenly being: Criseyde was this lady name al right./As to my doom, in al Troies cite/Nas non so fair, forpassynge every wight,/So aungelik was hir natif beaute,/That lik a thing inmortal semed she,/As doth an hevenyssh perfit creature,/That down were sent in scornynge of nature. (I.99–105)

Criseyde is seen as ‘heavenly’, ‘immortal’ and ‘perfect’, which brings into play the contemplative aspect of love, whereas the idea of ‘scorn’ already introduces a potential Petrarchist aspect into the poem. The idea of perfection is further corroborated by her portrait which states that ‘In beaute first so stood she, makeles’ (I.172), which creates the opportunity for the young Troilus, ‘this fierse and proude knyght’ (I.225), scornful of love and its effects, to arouse the God of Love’s wrath and to immediately fall in love: Yet with a look his herte wex a-fere,/That he that now was moost in pride above,/Wax sodeynly moost subgit unto love. (I.229–31)

Love finds his way through this ‘look’, piercing Troilus’s ‘eye’ (I.272) through hers (‘hire yen’, I.305), presenting him with ‘nevere … so good a syghte’ (I.294) of ‘Honour, estat, and wommanly noblesse’ (I.287), which makes him exclaim: ‘O mercy, God,’ thoughte he, ‘wher hastow woned,/That art so feyr and goodly to devise?’ (I.276–7)

…In thus juxtaposing the ‘Platonic’ and the ‘Petrarchist’ discourse of thinking and arguing about love, Chaucer begins to produce a non-hierarchical, that is ‘aesthetic’ plurality that clearly goes against a single ideological will to truth normally connected to historical discursive practices. He begins to construct, as well as deconstruct, different historical ways of speaking about love, opening up some kind of discursive (or rather adiscursive) game of abeyance apt to articulate several – figural, narratorial, authorial – truths about love at the same time without having to decide which will eventually have to be seen as the ‘right’ one.

This represents the kind of openness and undecidability that Jonathan Culler, among others, has identified as the place, and potential, of ‘literature’. This possibility of deconstructing truths, of circumventing discursive authority by a non-discursive (or counter-discursive), ‘literary’ language use, has already convincingly been claimed with regard to Petrarch’s work, notably his Canzoniere, as an instance of ‘poetic fiction’, that is literature, being ‘the systematic site of all work of deconstruction’.

It introduces the idea of a no longer ‘functional’ (pragmatic) but rather ‘autonomous’ (dysfunctional) variety of fiction, suspending ‘realities’, inventing alternative truths and opening up other possibilities than the ones seemingly obviously at hand.”

- Andreas Mahler, “‘Potent Raisings’: Performing Passion in Chaucer and Shakespeare.” in Love, History and Emotion in Chaucer and Shakespeare: Troilus and Criseyde and Troilus and Cressida

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Typography Tuesday

POST-WWI PRINTING IN ENGLAND

We return to Printing of To-Day: An Illustrated Survey of Post-War Typography in Europe and the United States, printed at the Curwen Press in 1928, and published by Harper and Brothers in New York. and Peter Davies Limited in London (a publishing house founded in 1926 by Peter Llewelyn Davies, one of the Llewelyn Davies children befriended by J. M. Barrie, and whose name was the source for Barrie’s Peter Pan).

This week we feature specimens from the section “Printing in England,” by British printer typographer Oliver Simon (1895–1956), the managing director of the Curwen Press and co-founder of the influential typography journal The Fleuron. Simon writes:

The majority of books in England are set by Monotype or Linotype machine. . . . The Monotype machine is, in my opinion, better adapted to printing the finest quality. . . . Moreover, the Monotype Corporation has a better selection of type faces to offer printers than its rival, although . . . both corporations fall short of what might be expected of them. . . .

There are no CONTEMPORARY Book-types worthy of note: printers are in advance of typographers. It is not easy to believe that there are not designers who could do good work if encouraged. . . . To-day, the two type corporations. . . have for all practical purposes a monopoly! Is it too much to ask them to commission modern types? . . . The plates that follow . . . may give a hint of what English printing will achieve in the near future if printers and publishers will have faith in their own age.

Fortunately, Simon would see his desired outcomes achieved during his lifetime. Once again, as image captions are still not appearing in the Tumblr dashboard, we list them here from top to bottom:

1,) Title page for Ernest Gimson: His Life and Work, printed in Caslon types by the Shakespeare Head Press, with an illustration by F. L. Griggs.

2.) Title page for Robert Graves’s Welchman’s Hose printed in 1925 at the Curwen Press for The Fleuron in Monotype Imprint.

3.) Page from Pompey the Little printed in Caslon with a wood engraving by David Jones at the Golden Cockerel Press.

5.) Page from William Meinhold’s Sidona the Sorceress, with an illustration by Thomas Lowinsky, published in Monotype Garamond by Ernest Benn for the Cambridge University Press.

6.) Opening page for Poor Young People, printed by the Curwen Press for The Fleuron in Monotype Caslon and illustrations by Albert Rutherston.

7.) Title page from Two Poems by Edward Thomas, designed by Percy Smith, and printed in 1927 at the Curwen Press for Ingpen & Grant in Caslon and Stephenson Blake open capitals.

8.) Opening page from Horati Carminum Libri IV, with illustrations by Vera Willoughby and Koch Kursiv type, printed by the Curwen Press for Peter Davies.

9.) Title page for Passo Domini printed in Caslon with wood engravings by Eric Gill at the Golden Cockerel press in 1926.

10.) Page from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, printed in Caslon at the Golden Cockerel Press with wood engravings by Eric Gill.

11.) Half title and text page from The Receipt Book of Elizabeth Raper, with illustrations by Duncan Grant, printed at the Kynoch Press in Monotype Baskerville and Stephenson Blake open capitals for the Nonesuch Press.

12.) Title page from The Poems of Richard Lovelace, printed in Fell types at the Oxford University Press in 1925.

View examples of Continental printing from Printing of To-Day.

View our other Typography Tuesday posts.

#Typography Tuesday#typetuesday#Printing of To-Day#Curwen Press#Oliver Simon#printing in England#20th Century#Caslon#Monotype Imprint#Garamond#Stephenson Blake#Koch Kursiv#Baskerville#Fell#Typography Tuesday

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wrestling with Shakespeare is good for the brain. Scientists have shown that reading the Bard and other classical writers has beneficial effects on the mind.

Works from Shakespeare, Chaucer, Wordsworth and D H Lawrence challenge readers because of their unusual words, tricky sentence structure and the repetition of phrases.

English professors at Liverpool University who teamed up with neuroscientists armed with brain-imaging equipment found that this challenge causes the brain to light up with electrical activity. Professor Philip Davis, who led the study at the university's department of English, said: "The brain appears to become baffled by something unexpected in the text that jolts it into a higher level of thinking.

They were also able to identify that the Shakespeare sparked activity across a far wider area of the brain than "plain" text, with the greatest concentration in a key area associated with language in the temporal lobe known as the Sylvian Fissure.

The researchers claim that techniques such as unusual sentence structure can also stimulate the brain. In the poem Troilus and Criseyde, Chaucer uses parenthesis to throw the reader off. He says: "Men say - not I - that she gave him his heart."

#shakespeare#sword#writing#language#poetry#wordsworth#dh lawrence#american#langauage#chaucer#writers#lingusitics#brain#mind

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Oxford Finals Papers

Hello! Here’s a much requested run-down of the papers I took for my finals! There are 2 streams you can choose between after your first year of Oxford English - Course 1 and Course 2. I went for Course 2 - chosen far less than Course 1 but I found it to be incredibly rewarding!

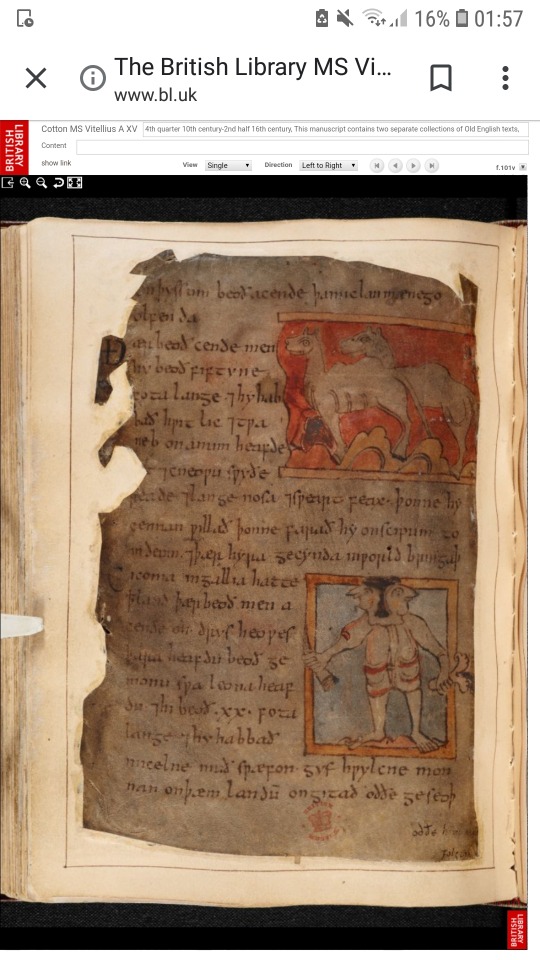

Paper 1 - Literature in English, 650-1100 (Old English)

- Exam in Trinity Term (3rd and final term), 3rd year, 3 essays in 3 hours

- College taught in Michaelmas Term (1st term) of 2nd year and then revisited for revision

- Focus: Cynewulf's runic signatures concluding his female saints' lives (Juliana and Elene), Ælfric's Catholic Homilies (particular focus on his life of Cuthbert), Old English metrical charms (particularly those found in the margins of MS CCCC 41)

- I LOVE OLD ENGLISH!!!! That is all I have to say about this one, I looooove it

Paper 2 - Medieval English and Related Literatures, 1066-1550 (Romance)

- Exam in Trinity Term, 3rd year, 2 essays in 3 hours

- Faculty taught in Hilary term (2nd term), 2nd year, and then revisited for revision

- Focus: Magic and the supernatural in the First Branch of the Mabinogi (medieval welsh), Marie de France's Lais (particularly Lanval and Milun; medieval French) and Walter Map's King Herla (Latin); The flexibility of the Middle English Sir Gowther in its varying manuscript contexts

- This paper was a challenge because it’s completely unlike anything I’ve done before. Because it was 2 essays in 3 hours (rather than the usual 3), topics had to be much broader and explored in greater depth. You’re also handling different languages too (although you can work with them in translation, but that does make the way you approach analysis different to the way it would be approached if you’re working with the original) and it’s a genre (rather than time period) paper. This is one of the reasons that I really liked Course 2 - while with Course 1 all the papers are time period ones, Course 2 spices things up a bit and I think that enables you to develop a broader skillset.

Paper 3 - Literature in English, 1350-1550 (Middle English)

- Exam in Trinity Term, 3rd year, 2 essays and 1 commentary in 3 hours

- College taught in Michaelmas and Hilary Term, 2nd year and then revisited for revision

- Focus: Authority and translation in Robert Henryson's Morall Fabillis, Gavin Douglas' Eneados and David Lindsay's 'The Testament and Complaynt of Our Soverane Lordis Papyngo'; Affective piety in Middle English Marian lyrics and related material culture; Set commentary passage from Chaucer's ‘Troilus and Criseyde’

- The topics I explored for this paper were really interesting - I thoroughly enjoyed it. I messed up my timing in the exam but hey ho, these things happen!

Paper 4 - The History of the English Language to c1800

- Coursework, submitted Trinity Term, 2nd year

- An essay and a commentary, both 2000-2500

- Formatted like a 'take-home exam' - questions are released and you choose 2 and have about 2.5 weeks to write and submit

- Faculty taught in Hilary and Trinity Term, 2nd year

- Chosen Questions:

Essay - In historical research, there are no 'bad documents' (HIPPOLYTE TAINE). Discuss.

Commentary - 'Nothing reveals the deficiencies of a language more surely than translating into it' (CHRISTIAN KAY). Provide a close analysis of the language of TWO texts which seem to you to reveal or contest that claim.

- Similar to the Romance paper, this one was unlike anything I’ve done before! It was a bloody challenge at first because of it being such an enormous leap up, especially having never done any linguistics before. In the end though, I loved it and I explored some really interesting topics!

Paper 5 - The Material Text

- Coursework, submitted Hilary Term, 3rd year

- A commentary and an essay, both 2000-2500 words

- Formatted in the same way as the English Language paper, but they're considering changing this to be more like your standard coursework

- Faculty taught in Trinity Term, 2nd year, and Michaelmas Term, 3rd year

- Chosen commentary folio:

- Chosen essay question: 'The introduction of error into the transmitted text is often regarded as a random and unpredictable phenomenon related to human frailty' (L. NEIDORF). What other alternatives are there? Give specific examples.

- I loved this paper (are you spotting a pattern here? haha) - getting to see so many real manuscripts up close was fascinating and I feel so lucky to have gotten to see some of the collection in Oxford! Perhaps controversially I chose this option over Shakespeare (!) but I’m so glad I did. I figured I could go back to Shakespeare at any time during my life, but seeing these manuscripts was a one-time opportunity.

Paper 6 - Special Options: Writing Lives

- Coursework, submitted Michaelmas Term, 3rd year

- A 6000 word essay

- Taught by 2 tutors running this specific option (there were a bunch of options released and you had to submit your top 5 - you’d then hopefully be given your 1st choice)

- Focus: The extent to which a writer's temporal moment affects the way they approach writing about mental health. Helen Macdonald's H is for Hawk; Thomas Hoccleve's Complaint and Dialogue

- Ironically, my own mental health went a bit haywire during the term in which I took this paper which was a shame, but hey ho, ya win some ya lose some, and I really enjoyed the texts we got to read for it. I kind of wish I’d chosen a more medieval option but I did manage to incorporate some medieval stuff in there with Hoccleve. The teaching and submission all being in 1 term is a bit ridiculous in my opinion too.

Paper 7 - Dissertation

- Coursework, submitted Hilary Term, 3rd year

- An 8000 word essay

- Undertaken from the end of 2nd year

- Abstract: 'For my dissertation, I will be examining twelfth-century texts (such as Instructions for Christians and the First Worcester Fragment) that speak back to those from the Anglo-Saxon past, considering inheritance from the poetic and homiletic traditions. Building on and developing from the work of Hugh Magennis, I will look at the way light imagery in such late Old English and Post-Conquest texts functions both literally and metaphorically, and how these two functions intersect. I will also consider how such texts engage in dialogue with material culture, examining artefacts such as The Gloucester Candlestick.'

- It was cool being able to research my own topic and produce something from that research. My supervisor was amazing too!

Overall, I really enjoyed the course. My tutoring, especially from my Balliol tutor, was outstanding - she really did go above and beyond for me. I didn't enjoy the writing of the longer pieces so much but I did enjoy the texts I looked at and it's definitely worthwhile to develop the skill of writing longer pieces I think. I loved the rest of my papers, especially Old English! On the whole it was a great course!

If you have any questions about any of this, feel free to ask!

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

You know... Gaiman just kind of beautifully summed up my issues with death of the author and authorial intent and all that jazz.

It's not that he's dead, he clearly isn't, and it's not that he has a right answer and the readers have to find it. It's that their answers are valid because they're doing the work. And a set answer from the author accidentally or intentionally invalidates their work. The work of finding meaning is valuable beyond the answer it yields.

The students are sub-creators (or co-creators if you want to go to the extreme opinion like me) of the story. He is the author. He sets up the boundaries of the text that everyone has to work within. It's like making up the rules of the game. Having done that, it is the reader's playground, their task to see what they can perceive in the text, what they have put into the text, why they have done those things, and are there other equally valid more interpretations. And as long as they follow the rules, the text, any play they engage in, interpretation, is valid.

I kind of resent the idea that there is a single right answer for literature. I agree that there is a right answer FOR YOU but that's a very different thing. For all that literature lovers bleat that literature is art and complex and not the simple memorization of facts or the inevitability of a word problem there does often seem to be a driving need to have a singular correct interpretation that everyone should agree on. And I feel like that's shortchanging the idea of art. How much lesser is a piece of art that can only be felt one way compared to a complexity that can live as richly in every individual interpretation of every single reader.

I really hit this idea when I was lucky enough to get Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde and then Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida one right after the other from two different college professors. Same basic "story" but radically different takes from the different authors. And the real beauty of it was that it was possible for us students to have different takes from the same exact text without a contradiction in text. If the author doesn't say exactly how something happens, the reader fills it in. So we all have to work from Cressida saying a particular line of text but how she says it, how she is blocked, what the facial reactions are, that's up to us and the story changes on our opinions. So I could have a different interpretation, completely valid from the textual evidence, influenced from the comparative experience of Chaucer's Criseyde. I had a kinder view of Cressida than most of the other people in my Shakespeare class and the debate between us, while no one was right or wrong, enriched all our readings.

I, frankly, would have been bitter if Shakespeare had shown up and said no, you can't empathize with Cressida, I wrote her to be a tool for manipulation and that's it.

Art is a dialectal experience. It's not that one answer is right or the other one is. It's that my answer is correct for me AND your answer is correct for you AND someone else's answer is correct for them so long as all of us can get to that answer from the text. That's why literature is powerful.

Hello Neil.

My friends and I (11th grade) recently read your short story “Other People” in English class. The class is locked is currently locked in debate as to whether the demon and the man are the same person, and whether the man who comes in at the end is the same as the man at the beginning. Please resolve this debate as we are on the verge of killing each other.

Thanks you!

I love that literature still has power to make people think and feel and care in this day and age.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Whitney notes numerous treacherous men from Greek mythology, including Sinon (who persuaded the Trojans to bring the Trojan horse into the city, thus causing the downfall of Troy), Eneas (who abandons his lover Dido), Theseus (who deserted Ariadne), and Jason (who abandoned Medea, after she saves his life on countless occasions). Whitney encourages her lover to be not like these men, but like Troilus, who faithfully died loving Criseyde. After Whitney makes her list of unfaithful men, she addresses the virtues she hopes her lover's wife will have, so that he does not regret his decision. She hopes this wife will have: the beauty of Helen, the chastity of Penelope, the constancy of Lucres, and the true love of Thisbe. Whitney tells her lover that aside from Helen's beauty, she possesses all of these qualities, she only wishes she had Cassandra's gift of prophecy so she could see whether he ends up misfortunate, or she does. Although Whitney clearly feels abandoned, she takes the moral high ground by wishing her lover the best, and offering him relationship advice. She completes her poem, or letter, as a morally virtuous woman, and not a victim."

city of troy. aphrodite. ariadne. hecate. and the jason... helen. penelope. 'misunderstood love' and 'forbidden love'. "'Star-crossed' or 'star-crossed lovers' is a phrase describing a pair of lovers who, for some external reason, cannot be together." "(The original texts of the prologue, Q1 and Q2, use the spelling 'starre-crost', but the version 'star-cross'd' is normally used in modern versions.)" "[aside from Lucres' constancy]" and true love. because what is that. do i have it. need it. want it. believe in it? aphrodite, ariadne, hecate, helen, penelope. harry, will, henry, jake, patrick.

0 notes

Text

CHAPTER 2 - FIVE- TO TWELVE-LINE FORMS

Iambic pentains (abbab)—Larkin/Annus Mirabilis:

https://allpoetry.com/Annus-Mirabilis

Iambic pentains (a8b6c8c8b6)—Coleridge/The Rime of the Ancient Mariner:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43997/the-rime-of-the-ancient-mariner-text-of-1834

Sestet/pentametric quatrain + couplet (ababcc)—Shakespeare/Venus and Adonis:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56962/venus-and-adonis-56d239f8f109c

Sestet/tetrametric (abbcac)—Larkin/An Arundel Tomb:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47594/an-arundel-tomb

Rhyme royal–heroic heptet (ababbcc)—Chaucer/Troilus and Criseyde:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/257/257-h/257-h.htm

Rhyme royal—Wyatt/They Flee From Me:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45589/they-flee-from-me

Rhyme royal—James I/The King's Quire:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44442/the-kings-quire

Rhyme royal—Shakespeare/The Rape of Lucrece:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50474/the-rape-of-lucrece

Rhyme royal—Wordsworth/Resolution and Independence:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45545/resolution-and-independence

Rhyme royal—Auden/Letter to Lord Byron:

https://arlindo-correia.com/lord_byron.html

Rhyme royal—Auden/The Shield of Achilles:

https://poets.org/poem/shield-achilles

Octet—tetrametric cross-rhymed (abab-cdcd)—Macauley/Horatius:

https://englishverse.com/poems/horatius

Octet—tetrametric single-rhymed (abcb-defe)—Tom O’Bedlam’s Song:

http://www.thehypertexts.com/Tom%20O%27%20Bedlam%27s%20Song.htm

Octet—Tetrametric bobbed (aaab6-cccd6)—Snodgrass/Magda Goebbels:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42798/magda-goebbels-30-april-1945

Octet—irregular trimetric (abcd-efgd)—Larkin/MCMXIV:

https://www.poetrybyheart.org.uk/poems/mcmxiv/

Octet—tetrametric couplet-rhymed (aabbccdd)—Marvell/The Garden:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44682/the-garden-56d223dec2ced

Octet—tetrametric couplet-rhymed (aabbccdd)—Marvell/Upon the Hill and Grove at Bilbrough:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48331/upon-the-hill-and-grove-at-bilbrough

Octet—tetrametric couplet-rhymed (aabbccdd)—Marvell/Upon Appleton House:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44689/upon-appleton-house-to-my-lord-fairfax

Triolet (1231-4512/abaa-abab)—Henley/Easy is the Triolet:

https://allpoetry.com/Easy-is-the-Triolet

Triolet—Hopkins/The Child is Father to the Man:

https://poets.org/poem/child-father-man

Triolet—Cope/Valentine:

https://gladdestthing.com/poems/valentine

Ottava rima—heroic octet (abababcc)—Byron/Beppo:

https://poetryarchive.org/poem/beppo-extract/

Ottava rima—Byron/Don Juan:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43833/don-juan-canto-11

Ottava rima—Yeats/Sailing to Byzantium:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43291/sailing-to-byzantium

Ottava rima—Yeats/Among School Children:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43293/among-school-children

Spenserian stanza—linked heroic quatrains + alexandrine (abab-bcbc-c12)—Spenser/The Fairie Queene:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45192/the-faerie-queene-book-i-canto-i

Spenserian stanza—Keats/The Eve of St. Agnes:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44470/the-eve-of-st-agnes

Spenserian stanza—Shelley/Adonais:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45112/adonais-an-elegy-on-the-death-of-john-keats

Spenserian stanza—Tennyson/The Lotos-eaters:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45364/the-lotos-eaters

Ten-line stanza (abab-cde-dce)—Keats/Ode on a Grecian Urn:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44477/ode-on-a-grecian-urn

Ten-line stanza (abab-cde-cde)—Keats/Ode on Melancholy:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44478/ode-on-melancholy

Ten-line stanza (abab-cde-c6de)—Keats/Ode to a Nightingale:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44479/ode-to-a-nightingale

Eleven-line stanza (abab-cded-cce)—Keats/To Autumn:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44484/to-autumn

Multi-line stanzas (12/11/12/14/18)—Keats/Ode to Psyche:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44480/ode-to-psyche

Douzaine (12 lines)—stacked couplets—Bradstreet/To My Dear and Loving Husband:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43706/to-my-dear-and-loving-husband

Douzaine—cross rhyme + arch rhyme (abab-cddc-efef)—Tennyson/Mariana:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45365/mariana

6 couplet sonnet—Shakespeare/Sonnet 126:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50649/sonnet-126-o-thou-my-lovely-boy-who-in-thy-powr

1 note

·

View note

Text

on classism and sexism in the establishing of English literature and its canon as university subjects, and how to make a student hate it:

If the tendency to view English literature as if it were a historical progression of worthy authors determined the University of London syllabus until well into the twentieth century, the ancient English universities, once they got round to establishing chairs and then courses of study, felt obliged to make English acceptable by rendering it dry, demanding, and difficult. The problem began with the idea that English was a parvenu subject largely suited to social and intellectual upstarts (a category which it was assumed included women). In order to appear ‘respectable’ in the company of gentlemanly disciplines such as classics and history, it had to require hard labour of its students. In the University of Oxford in particular, the axis of what was taken to be the received body of English literature was shifted drastically backwards.

The popular perception of a loose canon, like Arnold’s, which stretched from Chaucer to Wordsworth (or later Tennyson), was countered by a new, and far less arbitrary, choice of texts with a dominant stress on the close study of Old and Middle English literature. Beyond this insistence on a grasp of the earliest written forms of the English language, the Oxford syllabus virtually dragooned its students into a systematic consideration of a series of monumental poetic texts, all of which were written before the start of the Victorian age.

In the heyday of the unreformed syllabus, in the 1940s, the undergraduate Philip Larkin was, according to his friend Kingsley Amis, driven to the kind of protest unbecoming to a future university librarian. Amis recalls working his own way resentfully through Spenser’s Faerie Queene in an edition owned by his college library. At the foot of the last page he discovered an unsigned pencil note in Larkin’s hand which read: ‘First I thought Troilus and Criseyde was the most boring poem in English. Then I thought Beowulf was. Then I thought Paradise Lost was. Now I know that The Faerie Queene is the dullest thing out. Blast it.’

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Literature but Were Afraid to Ask Žižek: https://bit.ly/2J8ZTB0 - free delivery worldwide

Challenging the widely-held assumption that Slavoj Žižek's work is far more germane to film and cultural studies than to literary studies, this volume demonstrates the importance of Žižek to literary criticism and theory. The contributors show how Žižek's practice of reading theory and literature through one another allows him to critique, complicate, and advance the understanding of Lacanian psychoanalysis and German Idealism, thereby urging a rethinking of historicity and universality. His methodology has implications for analyzing literature across historical periods, nationalities, and genres and can enrich theoretical frameworks ranging from aesthetics, semiotics, and psychoanalysis to feminism, historicism, postcolonialism, and ecocriticism. The contributors also offer Žižekian interpretations of a wide variety of texts, including Geoffrey Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, Samuel Beckett's Not I, and William Burroughs's Nova Trilogy. The collection includes an essay by Žižek on subjectivity in Shakespeare and Beckett.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Literature but Were Afraid to Ask Žižek affirms Žižek's value to literary studies while offering a rigorous model of Žižekian criticism.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Literature but Were Afraid to Ask Žižek: https://bit.ly/2J8ZTB0 - free delivery worldwide

Introducing Slavoj Zizek: A Graphic Guide - https://bit.ly/2HlP9y3 - free delivery worldwide

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Morris

British Textile Designer

- William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896), was a British textile designer, poet, novelist, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditional British textile arts and methods of production.

- William Morris is best known as the 19th century's most celebrated designer, but he was also a driven polymath who spent much of his life fighting the consensus. A key figure in the Arts & Crafts Movement, Morris championed a principle of handmade production that didn't chime with the Victorian era's focus on industrial 'progress'. Our collections hold a huge amount of his work – not only wallpapers and textiles but also carpets, embroideries, tapestries, tiles and book designs.

- The legacy of William Morris is as extensive as it is difficult to trace. His artistic and poetic skill, along with the radical new ethos on art and society that he espoused, sent shockwaves through the worlds of art, architecture, design, poetry, and political thought.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Morris

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/introducing-william-morris

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/morris-william/life-and-legacy/

Image:

https://www.typeroom.eu/william-morris-an-ode-to-the-revolutionary-artivist-of-arts-and-crafts

Typography

Morris' design for the Kelmscott Press' trademark via Wiki.

The Nature of Gothic by John Ruskin, printed by Kelmscott Press. First page of text, with typical ornamented border. Right: Troilus and Criseyde, from the Kelmscott Chaucer. Illustration by Burne-Jones and decorations and typefaces by Morris via Wiki.

William Morris's membership card for the Democratic Federation, designed by Morris in 1883 via The William Morris Society.

0 notes

Text

“…Written in the early 1380s, Troilus and Criseyde engages with a growing English cultural interest in and anxiety about interiority, particularly as it was evident within the courtly love discourse of Chaucer’s immediate audience: the court of Richard II. During these early years of Richard’s reign, the evidence suggests that courtly love discourse flourished—both within courtly lyric and within the speech of courtiers themselves—and this discourse was coming to structure what it meant to be a noble man within the court. Through this discourse, royal subjects sought to construct stable, coherent identities by imagining their interior states in relation to an uncontrollable external power—not the monarch to whom they were literally, physically subject but a person to whom they were figuratively and emotionally subject: the female beloved.

Fourteenth-century courtly love was a discourse centered on constructing the interiority of the aristocratic male; the language of courtly love allowed male nobles to express and perform the sophistication of their masculine identities. By the end of the fourteenth century, as Richard Firth Green explains, Since the capacity to experience exalted human love was ... restricted entirely to the well-born, it followed that one way in which a man might display his gentility was to suggest that he was in love; thus the conventions by which this emotion was defined, originally pure literary hyperbole, became part of a code of polite behaviour. By engaging in this discourse—speaking of the overwhelming nature of his love and his unswerving loyalty despite the unattainable nature of his beloved—the male courtier demonstrated his own refinement and nobility.

Courtly love rhetoric was an internalization and eroticization of noble status; the use of such rhetoric was a way of performing the inherent nobility of one’s own interiority. Although a male courtier using the rhetoric of courtly love is explicitly speaking of his own interior emotional response to a particular woman, his performance of such rhetoric is shaped by and for a community of aristocratic men. As is now generally recognized, the rhetoric of courtly love is a social discourse of coercive power, asserting the courtier’s dominance over both the female love-object and men of lesser status.

As Susan Crane argues in her study of late medieval court performance, late medieval courtiers “constitute themselves especially by staging their distinctiveness.” Courtly love is such a performance: courtiers publicly perform a largely set script of powerlessness before love in order to demonstrate their private and unique masculine identities. Part of the performance of courtly love entails a lack of concern for the wider social community—after all, when a noble man is in love nothing else should matter—but, despite this apparent lack of concern, courtly love is always a discourse entrenched in social and political power structures.

In Troilus and Criseyde, Chaucer responds to and addresses the court’s interest in masculine interiority in general and courtly love in particular. Chaucer frequently addresses his court audience as “ye loveres” (I, 22) and, in the prologue, he refers to them, not as subjects of Richard II, but as the “God of Loves servantz” (I, 15). Over the course of the poem, Chaucer depicts Troilus as the embodiment of the typical courtly lover: Troilus falls instantly in love with Criseyde, is overwhelmed by his desire for her, becomes sick and helpless from his love-longing, idealizes Criseyde as the perfect woman, and desires nothing other than to serve her. And, indeed, like courtiers who perform courtly love lyrics, Troilus bursts out into his lyrical, narrative-halting Cantici Troili at three times over the course of the poem.

The poem’s interest in interiority extends beyond love, and one of the ways in which Chaucer emphasizes that courtly love is essentially a discourse of interiority is through his use of penitential language. By drawing on this language, Chaucer emphasizes the extent to which courtly discourse, like penitential discourse, is engaged in self-examination and self-definition. In the fourteenth century, inward reflection on the state of one’s own soul became a prominent feature of devotional texts in general and penitential texts in particular; penitential manuals provided readers with, as Katherine Little notes, “a capacious psychological language ... to think about their identity, identity understood as an inner self and as a self in relation to the larger Christian community.”

The language of sacramental confession encouraged penitents to think of themselves as individuals, individuated before God because of the deeply personal nature and willfulness of their sins. In Chaucer’s poem, Pandarus uses penitential terminology in order to help Troilus establish his new identity as a courtly lover precisely because such language offers a way of defining one’s internal state. Particularly in the opening two books, Pandarus extensively and explicitly uses such language, at one point instructing Troilus to repent his former disdain for love and “bet thi brest, and sey to God of Love, ‘Thy grace, lord, for now I me repente, If I mysspak, for now myself I love.’”

Pandarus’s language here is obviously not sincerely penitential, but he invites Troilus to use such language because it gives him a means by which to regard his internal state as both distinctly individual and fitting into recognizable and coherent identity categories. Since Chaucer centers his poem on Trojan men who are deeply invested in courtly love and their own interiority, Chaucer’s Trojan aristocracy bears a striking resemblance to the court of Richard II. By depicting a court apparently more concerned with its courtiers’ interiority than the wider political world, Chaucer’s poem aligns itself with many of the contemporary critiques of Richard II’s early court: namely that Richard was too interested in display of his own monarchical identity—through love discourse, his personal relationships with his inner circle of young courtiers, and lavish courtly display—and not interested enough in national interests, especially war with France.

In the 1380s in particular, Richard’s court was shedding the character of simply a military household and becoming a court that strove, at least in part, to be a court of love. In her recent analysis of the Troilus frontispiece, Joyce Coleman argues that, although we have little evidence of the court life of the period, the evidence we do have suggests that in the early 1380s Richard II was promoting a culture of Love strongly influenced by and modeled on the Roman de la Rose. Indeed, around 1386, at least three Middle English authors, including Chaucer in his Legend of Good Women, produced allegories in which they depict Richard himself as Cupid, the God of Love. The presence of women at court became more common, and Michael Bennett characterizes Richard II’s court during this time period as having “a rather precious, effete character” because of its emphasis on courtly love.

One chronicler particularly critical of Richard’s reign, Thomas Walsingham, famously criticized Richard’s knights for being “knights of Venus rather than of Bellona: more effective in the bedchamber than the field.” In the early 1380s, Richard’s court had constructed a model of masculinity founded on courtly love discourse and the interior identity of the individual courtly lover. This interest in interiority came at a high cost. There seems to have been a widely held belief among his contemporaries that Richard II was particularly interested in promoting himself as a courtly lover leading a court of love, and that this interest came at the expense of England’s claim to the French throne and England’s military dominance.

Many contemporaries, particularly the members of the established nobility displaced by Richard’s own chosen group of young courtiers, criticized Richard II because of his perceived failure as a military leader of England. In contrast to previous royal courts that centered more on martial and chivalric values grounded in the years of war with France, according to chronicle sources, Richard II wanted to end that war, and was simultaneously promoting a lifestyle that celebrated elegance of dress, subtlety of speech, and sophisticated and perhaps indelicate forms of recreation, innovations that were by no means fully consistent with more traditional conceptions of chivalric virtue.

Christopher Fletcher has recently questioned the truth of familiar claims that Richard was strongly committed to peace with France or allegations that the extravagance of Richard’s royal household made it impossible for the king to afford to pursue war; Fletcher argues that, in fact, the Exchequer severely restricted Richard’s funds, and Richard continued to press for grants of taxation for war. However, regardless of Richard’s own motivations, it is true that Richard’s reign saw greatly reduced fighting with France, and many contemporaries did believe that Richard’s court was extraordinarily extravagant.

Whether accurate or not, there was a growing perception—even before the Wonderful Parliament of 1386 and the Merciless Parliament of 1388 were to bring forth explicit allegations that Richard and his inner circle were overly concerned with their own individual wealth and power—that Richard II’s court was fostering an increased interest in the individual courtier, not the social good. Richard’s ambition was to establish his royal household as an autonomous power, as free as possible from the control of the established nobility. According to Lee Patterson, Richard’s development of the court as an exclusive society wholly dedicated to the fulfilment of the wishes of the king was not simply a matter of personal style. It was also part of a political programme aimed at dispossessing the traditional ruling class of England and replacing it with a courtier nobility created by Richard and located largely in the household.

The structure of Richard’s court placed him as the personal center of the court, with courtiers drawing their power directly from the king’s personal generosity. Richard’s rule made the importance of the individual and individual interiority a matter of political concern. If, as Lynn Staley persuasively argues, in the early part of his reign Richard himself was engaged and interested in “a vigorous, highly charged, and carefully coded conversation about authority,” then we can regard Troilus and Criseyde as taking part in this ongoing conversation. When Chaucer depicts Troilus’s obsession with his own internal state as contributing to the fall of Troy, he warns that the Ricardian court’s current interest in masculine interiority is one that is potentially dangerous to the English kingdom itself.

As I will show, over the course of the poem, Chaucer examines the dangers of an overemphasis on the interior state of the male nobility, rather than national and military interests, and casts suspicion on Troilus for privileging his interior state of love-longing over his military status as a prince of Troy. While Chaucer does not launch a direct critique of Richard II’s kingship, he expresses a deep anxiety about what would happen in a kingdom in which the ruling class set too high a value on their individual interior states at the expense of the national interest.”

- Jennifer Garrison, “Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde and the Danger of Masculine Interiority.”

#jennifer garrison#troilus and criseyde#richard ii#history#late middle ages#courtly love#court#medieval literature#medieval#geoffrey chaucer#english

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

bookposting #2 (shelf clearout 2/69*)

title: cosmopolitanism and the middle ages

editors: john m. ganim, shayne aaron legassie

series: the new middle ages (palgrave)

rating: ★★★★★

opinions: this was, i think, an extremely well-done collection. the authors all contributed strong essays with cogent arguments for the existence and complexity of varying types of cosmopolitanism within what janet abu-lughod calls the world-system of premodern eurasia. the essays themselves transition in focus over the course of the collection from cosmopolitan ideas and experiences across and around europe and asia in the first six chapters to, in the last four, engagements with primarily-english literature dealing with what robert r. edwards calls the “cosmopolitan imaginary” in a variety of times and spaces (the pre-christian low countries, the crusader states, piers plowman’s england…) which i think should definitely be read in concert with suzanne conklin akbari’s idols in the east and geraldine heng’s empire of magic and the invention of race in the european middle ages. of the essays, my favorites were sharon kinoshita’s “reorientations: the worlding of marco polo,” about placing marco polo’s travels in the context of writing in the mongol court, marla segol’s “medieval religious cosmopolitanisms: truth and inclusivity in the literature of muslim spain,” about three texts (two jewish, one islamic) which use anatomical descriptions of the body as a universal microcosm in their discussions on the utility of scripture in the search for truth, and robert r. edwards’s “cosmopolitan imaginaries,” about articulations of cosmopolitan identity in fulcher of chartres’s historia hierosolymitana, chaucer’s troilus and criseyde, and medieval retellings of the trojan war (although i have reservations about placing the historia on the same level as troy literature).

verdict: this one stays.

miscellanea:

this, i think, is the book i have written down the most lines from in my notebook where i write down things i like since—actually, i just checked, since city of quartz, which i didn’t read that long ago.

i am very much a fan of this book’s cover; i find the dusty lavender very pleasing to the eye as well as fitting for rectangular objects. i also like that the people on the cover are having a good time, although the photo information doesn’t tell me where it’s taken from.

john m. ganim, according to the back cover, has written a book called medieval orientalism which, on the strength of this collection, i am going to look up.

call number: JZ1308 .C673 2013

*today i made a bad decision (went into the bookstore) and got some more books, bringing the count of unread books in my room to 69. technically it should be 68 since i have already read one of them, but not as a physical book, and i didn’t want to pass up on the Nice Number.

0 notes