#tesuque pueblo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Camel Rock, NM

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unknown Photographer

Two Tesuque Buffalo Dancers, 1925.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Baking bread, Pueblo of Tesuque, New Mexico” c.unknown

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Pueblo” is the Spanish word for village. Spanish explorers used the word “pueblo” to describe both the permanent residential structures and the people living in these communities throughout the middle Rio Grande Valley.

There are 6 Pueblo communities within 30 miles of Sante Fe. Many are supposed to be a mix of old and new. Our goal was to try and find some of the original adobe structures. We decided to follow Frommer’s Guide to the Northern Pueblos of New Mexico. Turned out to be a “Wild Pueblo Hunt”!

First one Tesuque we never did find. We did drive through the small town of Tesuque. Second one Pojoaque, we passed on as Frommer’s said there wasn’t much there to see.

Our third attempt was the San Ildefonso Pueblo, we did find the community but were uncertain what was new and what was old. The top photo appears to be one of the original buildings. The visitor center was closed so we took a quick spin around as you are not to take photos without permission.

Fourth Pueblo, we may have hit the jackpot this time! Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo)

Saint John the Baptist Church sits across the road from the Our Lady of Lourdes Shrine built in 1889. The Shrine is in honour of the statue in front of the church. It is also only one of 19 buildings in the country built entirely out of lava rock.

The San Juan Pueblo community is behind the Shrine but we did not want to intrude. As far as we can tell this is a “kiva”, beside the Shrine, rooms under ground that the men of community would use for meetings and rituals.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lindsey Graham just compared the U.S. war crimes of using nuclear weapons against civilians of Hiroshima and Nagsaki to support his endorsement of the Palestinian genocide.

The U.S. should have never deployed nuclear weapons because it is ethically!wrong The U.S. also did not need to deploy the bombs to end the war!

The development of the nuclear bombs within the United States was conducted on stolen land of Mescalero Apache, and the near by "Pueblos of Acoma, Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Laguna, Nambe, Ohkay Owingeh, Picuris, Pojoaque, Sandia, San Felipe, San Ildefonso, Santa Ana, Santa Clara, Santo Domingo, Taos, Tesuque, Zuni and Zia." https://www.newmexico.org/native-culture/native-communities/ https://nuclearprinceton.princeton.edu/nuclear-weapons-testing-0

While the fallout of the initial test fanned north east it affected the Indigenous nations across the entire state. The initial test and every test following should be prosecuted as a war crime committed against each Indigenous nation of the "state" if not every "state". The long term health affects, contamination of: water, milk, vegetables, and of the land itself is horrific crime.

Nuclear testing in the Pacific in the Marshall Islands also forcefully removed the families from their homes. The people of the Marshall islands suffered acute radiation sickness and in some instances could not return to their homes.

All of which is to say it is abhorrent as the occupation murders entire families are in Gaza, Lindsey Graham has the audacity to come out and ask for the U.S. to continue it's active participation in genocide by directly supplying more weapons.

The history of U.S. war crimes begins with genocide at it's foundation which continues today by planning with and arming the IDF to commit genocide against Palestinians.

It is clear Lindsey Graham is speaking not out of turn but seeking to support another nation built by colonization and genocide

0 notes

Text

some favorites from this trip to the Nelson-Atkins.

Mt. Katahdin—November Afternoon by Marsden Hartley (American, 1877 - 1943). Oil on Masonite, 1942.

Tree by Arthur Garfield Dove (American, 1880 - 1946). Oil on canvas, 1934.

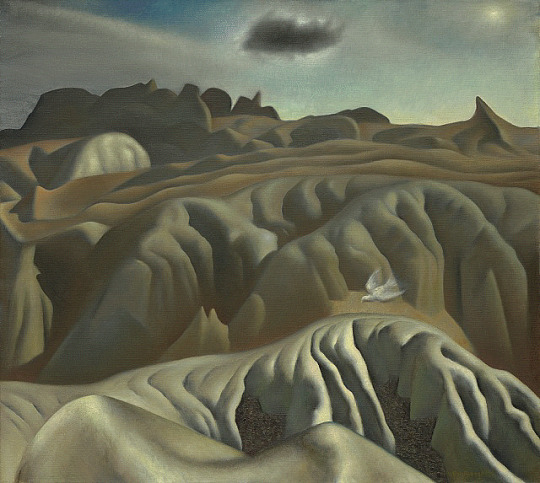

Tschaikovsky's Sixth by Ross Eugene Braught (American, 1898 - 1983). Oil on canvas, 1935.

Pueblo Tesuque, No. 2 by George Wesley Bellows (American, 1882 - 1925). Oil on canvas, 1917.

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Postcard Green Corn Dance at Tesuque Indian Pueblo Near Santa Fe, N.M. Linen.

0 notes

Photo

Woman grinding corn, Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico

Photographer: T. Harmon Parkhurst

Date: 1925 - 1945?

Negative Number: 004722

260 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Deer Dance”, Joe Duran of the Tesuque-Po-Ve-Peen, undated

Gouache on matted paper

Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

#pacificgrovemuseumofnaturalhistory#museum#collection#monterey#pacific grove#native american art#deer dance#joe duran#Tesuque-Po-Ve-Peen#tesuque pueblo#new mexico

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

First movie studio owned by Native Americans opens in New Mexico

Last year, the Tesuque Pueblo tribe of New Mexico opened a new casino, moving out of a 75,000-square foot facility that they quickly realized could be repurposed as a studio facility.

That idea was solidified in the fall, when the Universal Pictures feature “News of the World,” starring Tom Hanks, filmed at the facility. And thus launched Camel Rock Studios, which lays claim as the first movie…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Pueblo Indians, Tesuqua [i.e., Tesuque], N.M. - Hook - 1890s

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Get a girl that can do it many different ways

#airforce#feminism#girlsthatlift#girlsthatfight#fightlikeagirl#equality#dontgiveup#hipster#selfie#sucide girls#tattoos#natural#hippy#double life#native american#warriors#punk#fighting for our rights#native#tesuque pueblo

242 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Decorative Sunday

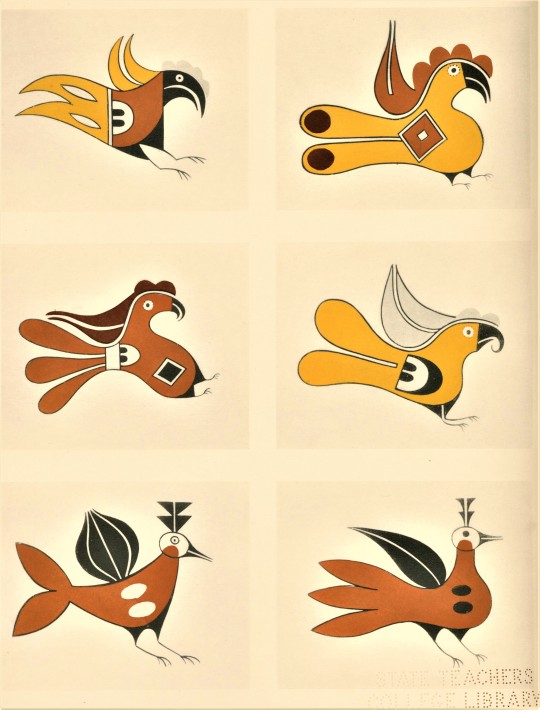

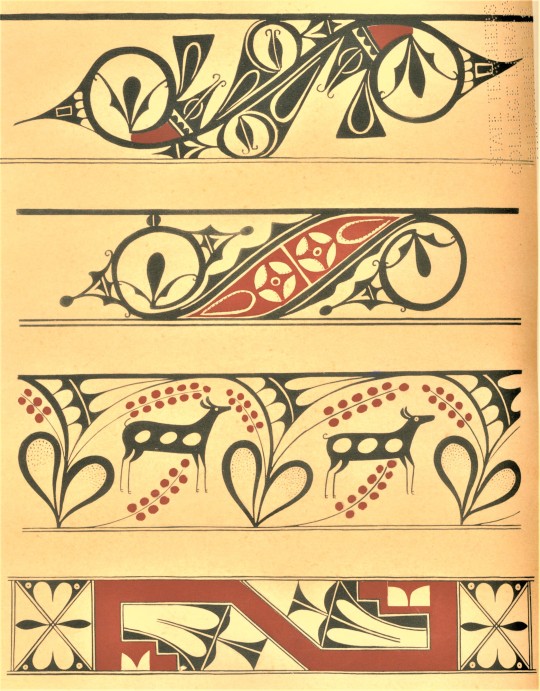

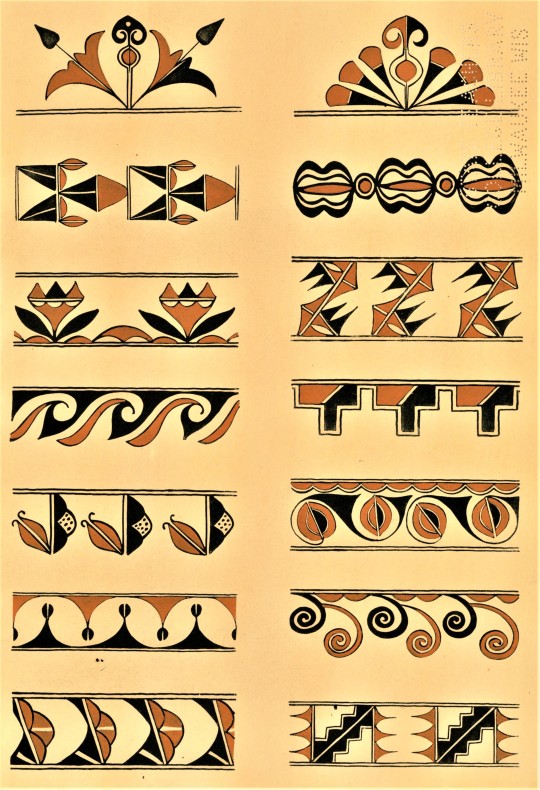

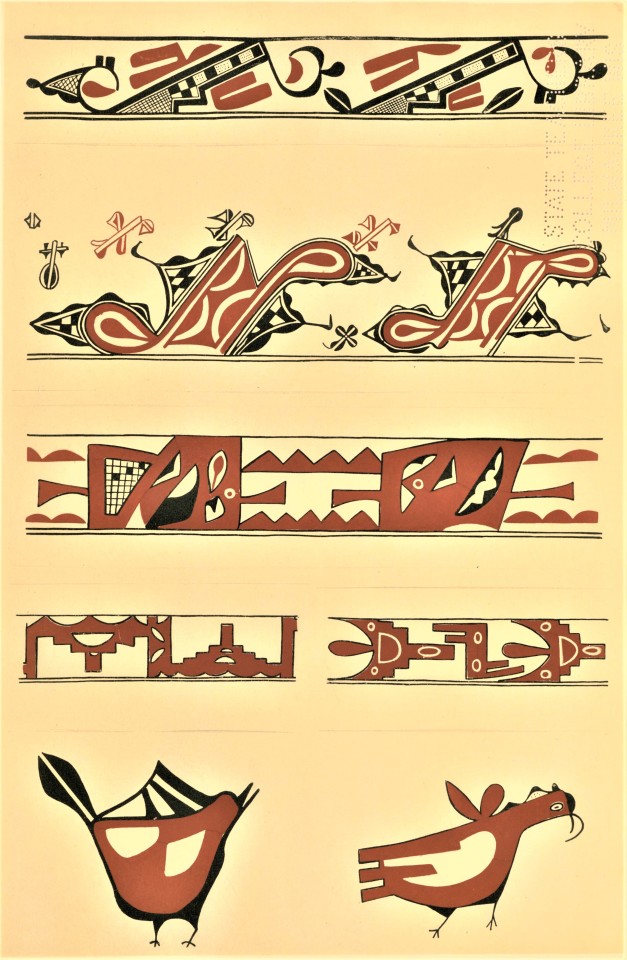

A few weeks ago, our graduate intern Olivia introduced us to the decorative-arts publishing of the somewhat hazy figure of C. Szwedzicki. In that post, Olivia noted that C. Szwedzicki produced 6 titles on Native American Art, the publishing of which was interrupted when the Nice, France, business was seized, either by German Nazis or French Pétainists, and Szwedzicki was shipped off to Poland. Szwedzicki survived the war, and the work on this series was resumed, beginning in 1950.

Today we are showing some plates from one of the titles in that series, the 2-volume Pueblo Indian Pottery by Kenneth M. Chapman, curator of the Indian Arts Fund and the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and published in by Szwedzicki in Nice from 1933 to 1936 in an edition of 750 numbered copies signed by the publisher. The volumes include 50 hand-colored photolithographs drawn by Kenneth Chapman himself after vessels in the collection of the Indian Arts Fund at the Laboratory of Anthropology. The text is in both English and French. Volume I focuses on Taos, Picuris, San Juan, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tesuque, Cochiti, Santo Domingo, and Santa Ana, while Volume II surveys Zia, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi.

Click on the images to view the captions. If that fails, see the list of plates below the “Keep reading” prompt.

See more of our Decorative Sunday posts here.

The images from top to bottom are:

1.) Acoma water jar, ca 1875-1925. Diameter 11 in./28 cm. 2.) Title page from volume 1. 3.) Conventional bird design from the interior of a food bowl, Sikyatki, Arizona, ca. 1500. 4.) Group of designs from Zuni pottery. 5.) Group of bird designs from Acoma pottery. 6.) Group of designs from antique Zia pottery. 7.) Typical designs from antique San Ildefonso pottery. 8.) Typical designs from antique Santa Ana pottery. 9.) Group of designs from antique and modern Hopi ware. 10.) Acoma bowl, ca. 1875. Diameter 18 in./46 cm.

#Decorative Sunday#decorative arts#decorative plates#Pueblo Indian Pottery#Pueblo Indians#decorative designs#C. Szwedzicki#Kenneth M. Chapman#Indian Arts Fund#Laboratory of Anthropology#photolithographs#lithographs#hand-colored plates

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Kimora Toledo was a little girl, she and her mother Malisha would make the hour-long drive from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Jemez Pueblo at least once a month. Malisha, who is from Jemez and Tesuque Pueblos, had moved her family to Albuquerque for a better job, but her father was a Jemez medicine man and it was important to her that Kimora be immersed in that heritage. On one of those visits to Jemez, Malisha remembers dancing alongside Kimora – who’s Jemez, Tesuque, Diné and Black – during the feast day celebrations. She hoped it would be the first of many times they’d dance together.

But Malisha battled a criminal record and her ex, Kimora’s father, managed to gain custody over Kimora and her younger brother. The two children would spend several years living at their dad’s house in Albuquerque, without those monthly visits to the pueblo.

When Kimora was 11, the New Mexico children, youth and families department removed her from her father’s home over abuse she was experiencing. Kimora would spend the next three years in and out of group homes and rehabilitation centers, eventually landing in foster care when she asked not to be returned to her father’s.

Kimora had never felt more disconnected from her culture and traditional ways of healing. Her foster mother, a Mexican woman, suggested Kimora take Spanish as an elective in school. But Kimora desperately missed her mother and grandfather, and the language they’d spoken during her childhood. “I missed a lot of my childhood and our traditions,” she said, just weeks before her seventeenth birthday.

Kimora and her mother didn’t know it then, but, as a Native American child, Kimora should have never ended up in foster care the way that she did.

This month, the US supreme court will consider the future of families like Kimora and Malisha’s. On 9 November, the court will hear oral arguments in Haaland v Brackeen, a case challenging the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act. Designed to keep Native American children in their communities during custody, foster care and adoption proceedings, ICWA was passed in 1978 in response to the mass separations of families that had been customary since the 19th century. Many Native American activists are worried for the future of ICWA, given the rightwing composition of the supreme court. Some – like Kimora and Malisha – are also working to enshrine it in local law.

Remedying a policy of destruction

In 1860, the Bureau of Indian Affairs opened the first of what would become more than 350 American Indian boarding schools, with the intention of “civilizing” Native American children – an assimilationist policy regarded by many as “cultural genocide” today. By the 1920s, nearly 83% of school-age Native American children were enrolled in boarding schools, where a government report found they were malnourished, overworked, harshly punished and poorly educated. As boarding school attendance increased into the 1960s and 70s – peaking at 60,000 in 1973 – the US government rolled out another program, called the Indian Adoption Project. It ended up placing 395 Native American children from western states with white families in the midwest and east coast.

By the 1970s, data showed that 25% to 35% of Native children had been removed from their families during the boarding school era, leading to the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978. According to the law, states are required to follow protocols when handling certain custody cases involving a Native child, including involving the tribe in the proceedings. Perhaps most notably, ICWA also establishes a placement preference system, requiring child welfare agencies to try to keep Native children within their communities – by placing them, for example, with extended family or with a foster family in their own tribe – to ensure that they do not lose ties to their heritage.

“I call it a remedial statute because it has been the US government’s policy for hundreds of years to destroy the Native American family,” said Angelique EagleWoman (Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate), director of the Native American Law and Sovereignty Institute at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law and one of 30 professors of American Indian law who filed an amicus brief with the supreme court in support of ICWA.

Despite ICWA’s existence, the law has often gone unenforced. That’s in part because there is no federal oversight agency monitoring compliance. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs released guidelines designed to improve enforcement in 2016, tribal officials say that state welfare agencies regarded them as suggestions that were not legally binding.

As a result of these gaps, in 2016, a 10-month-old Navajo and Cherokee boy was fostered by a white Texas couple, Chad and Jennifer Brackeen, who ultimately adopted him. When the Navajo Nation was alerted to the case and stepped in to place the child with a Navajo family, the Brackeens sued.

The questions the court will consider as it hears Brackeen v Haaland are twofold: whether ICWA discriminates on the basis of race and whether the law supersedes states’ rights to control child custody placements. The Brackeens and their supporters argue that ICWA violates the constitution’s equal protection clause, discriminating against them as a white family, and imposes unlawful requirements on states. The federal government and Native advocates say that Congress may enact laws that apply to states in order to uphold its treaty obligations, and that Native Americans belong to a political class based on their sovereign status, not a racial group.

With this supreme court showing willingness to upend long-held precedent, many advocates are worried for the future of the ICWA. In 2013, three justices currently on the court – John Roberts, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas – sided with the majority to rule against a Native American father who had given up custody rights before changing his mind. Since then, the court’s conservative majority has grown to six justices, including Amy Coney Barrett who is herself an adoptive parent. But that majority has also been joined by Neil Gorsuch, who has consistently supported tribal sovereignty – even when that’s meant going against the conservative majority – and many legal scholars are hoping that the court will not overturn ICWA because of how doing so would reshape the legal relationship between the federal government and Indian tribes.

“It is very difficult to conceive of the US supreme court reframing the entire relationship with tribal governments and tribal children,” says EagleWoman. “We are starting to heal our communities, and it would be a major setback to genocidal policies for the US supreme court to strike down any of the provisions in the Indian Child Welfare Act.”

A state-based alternative

Many states, including New Mexico, aren’t waiting to see how the court rules. Instead, they’re enshrining ICWA in state law. To date, ten states have codified ICWA – and eight have added provisions to augment it. Native-led coalitions in other states, like Wyoming, have begun working to do the same.

When organizers in New Mexico began working to pass the state’s Indian Family Protection Act, the majority of the 500 Native children in foster care were in non-Native homes, says Jacqueline Yalch (Isleta Pueblo), director of Isleta Pueblo social services and president of the New Mexico Tribal Indian Child Welfare Consortium. Since New Mexico passed its own law in March, she says, that number has fallen.

After Kimora was placed in foster care at age 14, a social worker reached out to her grandfather and helped him secure custody a year later. After five years of feeling separated from her heritage, Kimora moved back to the Jemez Pueblo and began relearning the Jemez language. Through her grandfather, Kimora was also reunited with her mom, who realized exactly how much Kimora had missed out on – like participating in coming of age ceremonies, learning traditional recipes and dancing at celebrations. “There were so many times we could have danced together,” Malisha said. She’s hoping as the risk of the Covid-19 pandemic lessens, they might be able to dance together again next year.

Malisha and Kimora said that advocating for New Mexico’s Indian Family Protection Act was a healing experience. “Our children are our future,” says Malisha. “We have to do whatever we can to protect them.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Tourist buying Indian pottery from children at Tesuque pueblo, New Mexico.” c.1939. Image by Lee, Russell.

#friends with clay#pueblo pottery#new mexico pottery#new mexico#indigenous pottery#pottery#ceramics#pottery merchant#clay#clay pots#vessels

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Robert Henri (1865 - 1929) Young Buck Of The Tesuque Pueblo, 1916 (61 by 51 cm)

4 notes

·

View notes