#targum onkelos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nephilim

The Nephilim are mysterious beings or people in the Hebrew Bible who are described as being large and strong. The word Nephilim is loosely translated as giants in most translations of the Hebrew Bible, but left untranslated in others. Some Jewish explanations interpret them as hybrid sons of fallen angels (demigods).

The main reference to them is in Genesis 6:1–4, but the passage is ambiguous and the identity of the Nephilim is disputed. According to the Book of Numbers 13:33, a report from ten of the Twelve Spies was given of them inhabiting Canaan at the time of the Israelite conquest of Canaan.

A similar or identical biblical Hebrew term, read as "Nephilim" by some scholars, or as the word "fallen" by others, appears in the Book of Ezekiel 32:27 and is also mentioned in the deuterocanonical books Judith 16:6, Sirach 16:7, Baruch 3:26–28, and Wisdom 14:6.

Etymology

The Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon (1908) gives the meaning of Nephilim as "giants", and holds that proposed etymologies of the word are "all very precarious". Many suggested interpretations are based on the assumption that the word is a derivative of Hebrew verbal root n-p-l "fall." Robert Baker Girdlestone argued in 1871 the word comes from the hif'il causative stem, implying that the Nephilim are to be perceived as 'those that cause others to fall down'. Ronald Hendel states that it is a passive form: 'ones who have fallen', grammatically analogous to paqid 'one who is appointed' (i.e., a deputy or overseer), asir 'one who is bound' (i.e., a prisoner), etc.

The majority of ancient biblical translations – including the Septuagint, Theodotion, Latin Vulgate, Samaritan Targum, Targum Onkelos, and Targum Neofiti – interpret the word to mean "giants". Symmachus translates it as "the violent ones" and Aquila's translation has been interpreted to mean either "the fallen ones" or "the ones falling [upon their enemies]."

In the Hebrew Bible, there are three interconnected passages referencing the nephilim. Two of them come from the Pentateuch. The first occurrence is in Genesis 6:1–4, immediately before the account of Noah's Ark. Genesis 6:4 reads as follows:

Where the Jewish Publication Society's translation simply transliterates the Hebrew nephilim as "Nephilim", the King James Version translates the term as "giants".

The nature of the Nephilim is complicated by the ambiguity of Genesis 6:4, which leaves it unclear whether they are the "sons of God" or their offspring who are the "mighty men of old, men of renown". Richard Hess takes it to mean that the Nephilim are the offspring, as does P. W. Coxon.

The second is Numbers 13:32–33, where ten of the Twelve Spies report that they have seen fearsome giants in Canaan:

Outside the Pentateuch there is one more passage indirectly referencing nephilim and this is Ezekiel 32:17–32. Of special significance is Ezekiel 32:27, which contains a phrase of disputed meaning. With the traditional vowels added to the text in the medieval period, the phrase is read gibborim nophlim ("'fallen warriors" or "fallen Gibborim"), although some scholars read the phrase as gibborim nephilim ("Nephilim warriors" or "warriors, Nephilim"). According to Ronald S. Hendel, the phrase should be interpreted as "warriors, the Nephilim" in a reference to Genesis 6:4. The verse as understood by Hendel reads:

Brian R. Doak, on the other hand, proposes to read the term as the Hebrew verb "fallen" , not a use of the specific term "Nephilim", but still according to Doak a clear reference to the Nephilim tradition as found in Genesis.

Interpretations:

Giants

Most of the contemporary English translations of Genesis 6:1–4 and Numbers 13:33 render the Hebrew nefilim as "giants". This tendency in turn stems from the fact that one of the earliest translations of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint, composed in the 3rd or 2nd century BCE, renders the said word as gigantes. The choice made by the Greek translators has been later adopted into the Latin translation, the Vulgate, compiled in the 4th or 5th century CE, which uses the transcription of the Greek term rather than the literal translation of the Hebrew nefilim. From there, the tradition of the giant progeny of the sons of God and the daughters of men spread to later medieval translations of the Bible.

The decision of the Greek translators to render the Hebrew nefilim as Greek gigantes is a separate matter. The Hebrew nefilim means literally "the fallen ones" and the strict translation into Greek would be peptokotes, which in fact appears in the Septuagint of Ezekiel 32:22–27. It seems then that the authors of Septuagint wished not only to simply translate the foreign term into Greek, but also to employ a term which would be intelligible and meaningful for their Hellenistic audiences. Given the complex meaning of the nefilim which emerged from the three interconnected biblical passages (human–divine hybrids in Genesis 6, autochthonous people in Numbers 13 and ancient warriors trapped in the underworld in Ezekiel 32), the Greek translators recognized some similarities. First and foremost, both nefilim and gigantes were liminal beings resulting from the union of the opposite orders and as such retained the unclear status between the human and divine. Similarly dim was their moral designation and the sources witnessed to both awe and fascination with which these figures must have been looked upon. Secondly, both were presented as impersonating chaotic qualities and posing some serious danger to gods and humans. They appeared either in the prehistoric or early historical context, but in both cases they preceded the ordering of the cosmos. Lastly, both gigantes and nefilim were clearly connected with the underworld and were said to have originated from earth, and they both end up closed therein.

In 1 Enoch, they were "great giants, whose height was three hundred cubits". A cubit being 18 inches (46 cm), this would make them 450 feet (140 m) tall.

The Quran refers to the people of Ād in Quran 26:130 whom the prophet Hud declares to be like jabbarin (Hebrew: gibborim), probably a reference to the Biblical Nephilim. The people of Ād are said to be giants, the tallest among them 100 ft (30 m) high. However, according to Islamic legend, the ʿĀd were not wiped out by the flood, since some of them had been too tall to be drowned. Instead, God destroyed them after they rejected further warnings. After death, they were banished into the lower layers of hell.

Fallen angels

All early sources refer to the "sons of heaven" as angels. From the third century BCE onwards, references are found in the Enochic literature, the Dead Sea Scrolls (the Genesis Apocryphon, the Damascus Document, 4Q180), Jubilees, the Testament of Reuben, 2 Baruch, Josephus, and the book of Jude (compare with 2 Peter 2). For example: 1 Enoch 7:2 "And when the angels, (3) the sons of heaven, beheld them, they became enamoured of them, saying to each other, Come, let us select for ourselves wives from the progeny of men, and let us beget children." Some Christian apologists, such as Tertullian and especially Lactantius, shared this opinion.

The earliest statement in a secondary commentary explicitly interpreting this to mean that angelic beings mated with humans can be traced to the rabbinical Targum Pseudo-Jonathan and it has since become especially commonplace in modern Christian commentaries. This line of interpretation finds additional support in the text of Genesis 6:4, which juxtaposes the sons of God (male gender, divine nature) with the daughters of men (female gender, human nature). From this parallelism it could be inferred that the sons of God are understood as some superhuman beings.

The New American Bible commentary draws a parallel to the Epistle of Jude and the statements set forth in Genesis, suggesting that the Epistle refers implicitly to the paternity of Nephilim as heavenly beings who came to earth and had sexual intercourse with women. The footnotes of the Jerusalem Bible suggest that the biblical author intended the Nephilim to be an "anecdote of a superhuman race".

Some Christian commentators have argued against this view, citing Jesus's statement that angels do not marry. Others believe that Jesus was only referring to angels in heaven.

Evidence cited in favor of the fallen angels interpretation includes the fact that the phrase "the sons of God" ("sons of the gods") is used twice outside of Genesis chapter 6, in the Book of Job (1:6 and 2:1) where the phrase explicitly references angels. The Septuagint manuscript Codex Alexandrinus reading of Genesis 6:2 renders this phrase as "the angels of God" while Codex Vaticanus reads "sons".

Targum Pseudo-Jonathan identifies the Nephilim as Shemihaza and the angels in the name list from 1 Enoch.

Second Temple Judaism

The story of the Nephilim is further elaborated in the Book of Enoch. The Greek, Aramaic, and main Ge'ez manuscripts of 1 Enoch and Jubilees obtained in the 19th century and held in the British Museum and Vatican Library, connect the origin of the Nephilim with the fallen angels, and in particular with the egrḗgoroi (watchers). Samyaza, an angel of high rank, is described as leading a rebel sect of angels in a descent to earth to have sexual intercourse with human females:

In this tradition, the children of the Nephilim are called the Elioud, who are considered a separate race from the Nephilim, but they share the fate of the Nephilim.

Some believe the fallen angels who begat the Nephilim were cast into Tartarus (2 Peter 2:4, Jude 1:6) (Greek Enoch 20:2), a place of "total darkness". An interpretation is that God granted ten percent of the disembodied spirits of the Nephilim to remain after the flood, as demons, to try to lead the human race astray until the final Judgment.

In addition to Enoch, the Book of Jubilees (7:21–25) also states that ridding the Earth of these Nephilim was one of God's purposes for flooding the Earth in Noah's time. These works describe the Nephilim as being evil giants.

There are also allusions to these descendants in the deuterocanonical books of Judith (16:6), Sirach (16:7), Baruch (3:26–28), and Wisdom of Solomon (14:6), and in the non-deuterocanonical 3 Maccabees (2:4).

The New Testament Epistle of Jude (14–15) cites from 1 Enoch 1:9, which many scholars believe is based on Deuteronomy 33:2. To most commentators this confirms that the author of Jude regarded the Enochic interpretations of Genesis 6 as correct; however, others have questioned this.

Descendants of Seth and Cain

References to the offspring of Seth rebelling from God and mingling with the daughters of Cain are found from the second century CE onwards in both Christian and Jewish sources (e.g., Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, Augustine of Hippo, Sextus Julius Africanus, and the Letters attributed to St. Clement). It is also the view expressed in the modern canonical Amharic Ethiopian Orthodox Bible: Henok 2:1–3 "and the Offspring of Seth, who were upon the Holy Mount, saw them and loved them. And they told one another, 'Come, let us choose for us daughters from Cain's children; let us bear children for us.'"

Orthodox Judaism has taken a stance against the idea that Genesis 6 refers to angels or that angels could intermarry with men. Shimon bar Yochai pronounced a curse on anyone teaching this idea. Rashi and Nachmanides followed this. Pseudo-Philo (Biblical Antiquities 3:1–3) may also imply that the "sons of God" were human. Consequently, most Jewish commentaries and translations describe the Nephilim as being from the offspring of "sons of nobles", rather than from "sons of God" or "sons of angels". This is also the rendering suggested in the Targum Onqelos, Symmachus and the Samaritan Targum, which read "sons of the rulers", where Targum Neophyti reads "sons of the judges".

Likewise, a long-held view among some Christians is that the "sons of God" were the formerly righteous descendants of Seth who rebelled, while the "daughters of men" were the unrighteous descendants of Cain, and the Nephilim the offspring of their union. This view, dating to at least the 1st century CE in Jewish literature as described above, is also found in Christian sources from the 3rd century if not earlier, with references throughout the Clementine literature, as well as in Sextus Julius Africanus, Ephrem the Syrian, and others. Holders of this view have looked for support in Jesus' statement that "in those days before the flood they [humans] were ... marrying and giving in marriage" (Matthew 24:38, emphasis added).

Some individuals and groups, including St. Augustine, John Chrysostom, and John Calvin, take the view of Genesis 6:2 that the "Angels" who fathered the Nephilim referred to certain human males from the lineage of Seth, who were called sons of God probably in reference to their prior covenant with Yahweh (cf. Deuteronomy 14:1; 32:5); according to these sources, these men had begun to pursue bodily interests, and so took wives of "the daughters of men", e.g., those who were descended from Cain or from any people who did not worship God.

This also is the view of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, supported by their own Ge'ez manuscripts and Amharic translation of the Haile Selassie Bible—where the books of 1 Enoch and Jubilees, counted as canonical by this church, differ from western academic editions. The "Sons of Seth view" is also the view presented in a few extra-biblical, yet ancient works, including Clementine literature, the 3rd century Cave of Treasures, and the c. 6th century Ge'ez work The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan. In these sources, these offspring of Seth were said to have disobeyed God, by breeding with the Cainites and producing wicked children "who were all unlike", thus angering God into bringing about the Deluge, as in the Conflict:

Arguments from culture and mythology

In Aramaic culture, the term niyphelah refers to the Constellation of Orion and nephilim to the offspring of Orion in mythology. However the Brown–Driver–Briggs lexicon notes this as a "dubious etymology" and "all very precarious".

J. C. Greenfield mentions that "it has been proposed that the tale of the Nephilim, alluded to in Genesis 6 is based on some of the negative aspects of the Apkallu tradition." The apkallu in Sumerian mythology were seven legendary culture heroes from before the Flood, of human descent, but possessing extraordinary wisdom from the gods, and one of the seven apkallu, Adapa, was therefore called "son of Ea" the Babylonian god, despite his human origin.

Arabian paganism

Fallen angels were believed by Arab pagans to be sent to earth in form of men. Some of them mated with humans and gave rise to hybrid children. As recorded by Al-Jahiz, a common belief held that Abu Jurhum, the ancestor of the Jurhum tribe, was actually the son of a disobedient angel and a human woman.

Fossil remains

Alleged discoveries of Nephilim remains have been a common source of hoaxing and misidentification.

In 1577, a series of large bones discovered near Lucerne were interpreted as the bones of an antediluvian giant about 5.8 m (19 ft) tall. In 1786, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach found out that these remains belonged to a mammoth. Cotton Mather believed that fossilized leg bones and teeth discovered near Albany, New York, in 1705, were the remains of nephilim who perished in a great flood. Paleontologists have identified these as mastodon remains.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

JOSEPH, REMAINING TRUE TO G-D, IN THE MIDST OF MAGICIANS

Daily Study Chumash with Rashi

Parshat Vayigash, 2nd Portion (Genesis 44:31-45:7)

Monday, 2 Tevet 5783 / December 26, 2022

https://www.chabad.org/dailystudy/torahreading.asp?tdate=12/26/2022&auto=audio#auto=audio&author=13568&index=1

Genesis Chapter 45 1 Now Joseph could not bear all those standing beside him, and he called out, "Take everyone away from me!" So no one stood with him when Joseph made himself known to his brothers. Now Joseph could not bear all those standing: He could not bear that Egyptians would stand beside him and hear his brothers being embarrassed when he would make himself known to them. [From Tanchuma Vayigash 5] 2 And he wept out loud, so the Egyptians heard, and the house of Pharaoh heard. and the house of Pharaoh heard: Heb. פַּרְעֹה בֵּית, the house of Pharaoh, namely his servants and the members of his household. This does not literally mean a house, but it is like “the house of Israel” (Ps. 115:12), “the house of Judah” (I Kings 12:21), mesnede in Old French, household. [From Targum Onkelos] 3 And Joseph said to his brothers, "I am Joseph. Is my father still alive?" but his brothers could not answer him because they were startled by his presence. they were startled by his presence: Because of embarrassment. [From Tanchuma Vayigash 5] 4 Then Joseph said to his brothers, "Please come closer to me," and they drew closer. And he said, "I am your brother Joseph, whom you sold into Egypt.

Daily Tanya

Likutei Amarim, beginning of Chapter 6

https://www.chabad.org/dailystudy/tanya.asp?tdate=12/26/2022&auto=audio#auto=audio&author=13568&index=1

Concerning the concept of kelipah, we have noted in ch. 1 that although all existence was created by and receives its life from G-dliness, yet, in order that man be able to choose between good and evil and that he earn his reward by serving his Creator by his own effort, G-d created forces of impurity which conceal the G-dliness in all of creation. These forces are called kelipah (plural: kelipot), literally meaning “shells” or “peels”: Just as the shell conceals the fruit, so do the forces of kelipah conceal the G-dliness in every created being.

There are two categories in kelipot: kelipat nogah (lit., “a kelipah [inclusive] of light”) and “the three unclean kelipot.”

The first category, kelipat nogah, contains some measure of good. It is thus an intermediary level between the realms of good and evil, and whatever receives its vitality via the concealing screen of this kelipah may be utilized for either good or evil. To this category belong all permitted physical objects; they may be used for a mitzvah and ascend thereby to the realm of holiness, or they may be used sinfully, G-d forbid, and thereby be further degraded.

The second category—consisting of the “three impure kelipot”—is wholly evil. Whatever receives its vitality via the concealment of this type of kelipah cannot be transformed into holiness, nor, in some cases, may it even be used in the service of holiness. To this category belong all forbidden physical objects, whether forbidden only for consumption, in which case they cannot be transformed into holiness but they may serve it, or whether forbidden for any form of benefit, in which case they cannot even serve any holy purpose.

#DAILY TORAH TANYA PSALMS#DAILY GOOD DEEDS AND CHARITY#JOSEPH REMAINING TRUE TO G-D IN THE MIDST OF MAGICIANS

0 notes

Photo

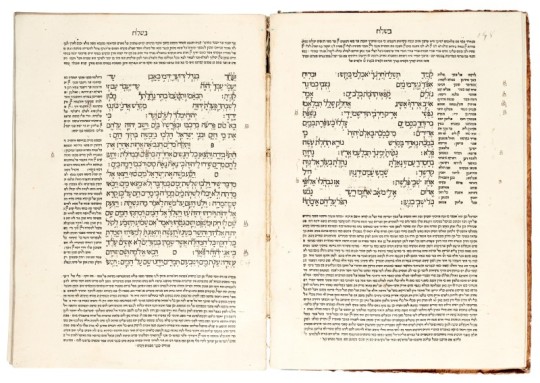

The De Castro Pentateuch

With Haftarot and Five Scrolls

Scribe: Netanel [ben] Daniel (?)

Germany, 1344

Handwritten on parchment; dark brown and red ink, tempera, silver leaf; square and semi-cursive Ashkenazic script. L: 46; W: 31 cm

Commissioned by Joseph ben Ephraim for private use and public reading in the synagogue, this manuscript contains the Aramaic translation Targum Onkelos, as well as a hitherto-unknown version of the commentary of Rashi (Solomon ben Isaac, 1040-1105). The opening of each of the Five Books of Moses and the Five Scrolls is decorated with a large initial word and sometimes with an illustration, such as Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden for Genesis. A full-page depiction of the hanging of Haman and his sons closes the book of Esther.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mekhashepha in Melungeon Culture: Breaking it Down

In order to understand Mekhashepha and its ties to Melungeoninity you must first understand some history. In recent years there has been a lot of push back against cultural Melungeons sharing their traditional culture and practices, with new age Melungeons demonizing and invalidating Melungeon culture in search of something more “mystical” in the form of appropriating Indigenous tribes form which they have no proof of claim. It is no secret that this denial and invalidation is rooted in antisemitism, and denial of Hebrew Melungeons. It is undeniable that Melungeon (and Appalachian) people have Hebrew influence, whether this influence is ethnic, cultural, religious, or both varies per family. This can be substantiated by looking at many common Melungeon names (and old Appalachian names), surnames, dialect, and traditions. Examples can be seen in the common Melungeon surname Cohen>Cowen>Gowen>Goin/Goins as well as common Melungeon given names such as Mahala, Nehemiah, Keziah, Hezekiah, Uzziah, Etc. Melungeon people also have undeniable ties to Spain/Portugal this can also be substantiated by things like surnames (chavis/chavez), traditions, dialect, Oral History, and DNA. Mekhashepha is an ancient Hebrew word, it has been in use since before we existed as Melungeon people, however in the early 1900′s a man named Eliezer Ben Yeuhda, a lexicographer, created the first Hebrew English dictionary, becoming a driving force in the revival of the Hebrew Language, giving terms like Mekhashepha a resurgence, even if temporary at best. Many words coined by Yehuda became part of everyday Hebrew language while others died out or never caught on. The ancient origins of Melungeon people remains unconfirmed today, but it was once a common rumor among colonizers that Melungeon people were born of an affair between The Devil and an Indigenous Woman. This is important to note because this is likely in part why the term Mekhashepha was weaponized against our people. Though Melungeon people are not specifically mentioned, the book “ Religious Authority in the Spanish Renaissance “ by LuAnn Homza notes Nicholas De Lyra’s use of the Onkelos Targum when translating the term Mekhashepha to refer to a female soothsayer, sorceress, or witch, with carnal ties to the Devil. Mekhashepha originally tended to refer to a title, usually that of a female, and not the name of their religious or spiritual practice, though today, following Yehuda’s dictionary, it seems to be used interchangeably. In the Torah and the Old Testament, the Mekhashepha are also included with "necromancers", "those who cast spells", "those who summon spirits" etc., as "an abomination to Yahweh" in Deuteronomy 18:9-10. Mekhashepha does however have controversial translations as many scholars debate it may refer to an herbalist, healer, poisoner, or even pharmacist. In some translations it is said Mekhashepha may be relied on to heal the sick, foretell the future, and predict agricultural outcomes. These are all things that were tied to Melungeon folk and traditional beliefs as well and can be seen still today in practices like faith healing, the man of signs, reading cards, using blood beads, folk remedies, etc. Due to the negative associations between Mekhashepha and Satan, many Melungeon people were not enthusiastic about identifying with the term, however neither were they about identifying as Melungeon. In recent, with the rise of popularity in witchcraft, natural healing, cultural acceptance, and feminism, many Melungeons have made the decision to reclaim these terms and wear them and identify with them proudly, while others still feel uncomfortably with these terms. For further reading on Mekhashepha: https://history.stackexchange.com/questions/39828/what-was-the-churchs-attitude-to-magic-prior-to-the-15th-century

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eliezer_Ben-Yehuda

https://www.academia.edu/33078425/When_a_single_word_matters_The_role_of_Bible_translations_in_the_witch_hunt_in_the_Grand_Duchy_of_Lithuania

https://archive.org/stream/AbrahamAbulafiaAStarterKit/AncientJewishMagic_djvu.txt

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is Mashiach?

We are all well acquainted with Ramban’s 7th article of Jewish faith, poetically rendered in our siddurim as: אֲנִי מַאֲמִין בֶּאֱמוּנָה שְׁלֵמָה שֶׁנְּבוּאַת משֶׁה רַבֵּֽנוּ עָלָיו הַשָּׁלוֹם הָיְתָה אֲמִתִּית וְשֶׁהוּא הָיָה אָב לַנְּבִיאִים לַקּוֹדְמִים לְפָנָיו וְלַבָּאִים אַחֲרָיו (I believe with complete faith [emunah] that the prophecy of Moshe Rabbeinu [our Teacher], may peace be upon him, was true, and that he was the father of the prophets, of those who precede him and of those who succeed him). And, of course, this statement agrees with what is written in the Torah itself (Devarim 34:10): וְלֹא־קָם נָבִיא עוֹד בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל כְּמֹשֶׁה אֲשֶׁר יְדָעוֹ יְיָ פָּנִים אֶל־פָּנִים (Never again has there arisen in Yisrael a prophet like Moshe whom Hashem knew face to face).

If it is true that there never has been a prophet comparable to Moshe in the past and that there never will be a prophet comparable to Moshe in the future, then we have a question: What about Mashiach? Isn’t he going to be greater than Moshe Rabbeinu?

Yeshaya was given an extraordinary and extensive prophecy about the Mashiach (see Yeshaya 52:13-53:12). The passage begins with these awesome words (52:13): הִנֵּה יַשְׂכִּיל עַבְדִּי יָרוּם וְנִשָּׂא וְגָבַהּ מְאֹד (Behold! My servant will become wise. He will be exalted, and be lifted up and be very high). Just how great will the Mashiach be? The Midrash explains the meaning of the three-fold praise expressed in this verse (Yalkut Shemoni Remez 476): זה מלך המשיח...ירום מן אברהם ונשא ממשה וגבה ממלאכי השרת (This is the king Mashiach…he will be exalted above Avraham, and he will be lifted up more than Moshe, and he will be higher than the ministering angels).

How can it be that the Mashiach is described in this prophecy as not only being greater than Moshe Rabbeinu but even greater than the angels, and yet, as we have already read, the verse in the Torah itself (Devarim 34:10) and the codified statement of faith from the Rambam clearly say that no one will ever be greater than Moshe Rabbeinu? Let’s examine this intriguing and important question.

Before Yaakov’s passing, he blessed his son Yehudah with the following words (Bereshit 49:10): לֹא־יָסוּר שֵׁבֶט מִיהוּדָה וּמְחֹקֵק מִבֵּין רַגְלָיו עַד כִּי־יָבֹא שִׁילֹה וְלוֹ יִקְּהַת עַמִּים (A scepter will not depart from Yehudah nor a lawgiver from between his feet [i.e., from among his descendants] until Shiloh comes, and the peoples/nations will assemble to him). Based on the Midrash (see Bereshit Rabbah 99:8) and Targum Onkelos, Rashi states unequivocally that Shiloh is מֶלֶךְ הַמָּשִׁיחַ שֶׁהַמְּלוּכָה שֶׁלּוֹ (The king Mashiach and the monarchy is his). We read the same thing in the Gemara (Sanhedrin 98b): מה שמו דבי רבי שילא אמרי שילה שמו שנאמר עד כי יבא שילה (What is his [Mashiach’s] name? Those of R' Shila’s yeshiva said, Shiloh is his name, as it is stated, ‘until Shiloh comes’). But why did Yaakov use the name Shiloh? It is a code word for Moshe since the gematria of both names are identical (משה = שילה = 345).

This gematria is not novel. It is known from many sources, for example, R' Nachman teaches (Likutei Moharan 2): כָּל צַדִּיק שֶׁבַּדּוֹר הוּא בְּחִינַת מֹשֶׁה מָשִׁיחַ...וּ��ֹשֶׁה זֶה בְּחִינַת מָשִׁיחַ כְּמוֹ שֶׁכָּתוּב עַד כִּי יָבֹא שִׁילֹה דָא מֹשֶׁה מָשִׁיחַ (Each Tzaddik in the generation is an aspect of Moshe Mashiach…and this Moshe is an aspect of Mashiach, as it is written, ‘until Shiloh comes’—this is Moshe Mashiach). This idea is elaborated upon in Likutei Moharan 79: וּבְכָל צַדִּיק וְצַדִּיק מִי שֶׁהוּא צַדִּיק בֶּאֱמֶת יֵשׁ בּוֹ הִתְגַּלּוּת מָשִׁיחַ. וְאַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ הִתְגַּלּוּת מָשִׁיחַ יֵשׁ בּוֹ מִדָּה שֶׁל מָשִׁיחַ שֶׁהוּא בְּחִינַת משֶׁה כְּמוֹ שֶׁכָּתוּב בַּזֹּהַר הַקָּדוֹשׁ (בְּרֵאשִׁית כה:) מָשִׁיחַ דָּא משֶׁה (And in each Tzaddik [of every generation], he who is the true Tzaddik, is a revelation of Mashiach. And even if he is not a revelation of Mashiach, he has in him the attribute of Mashiach, who is an aspect of Moshe, as it is written in the Zohar ha-Kadosh [Bereshit 25b] ‘Mashiach is Moshe’).

These sources reveal the hidden meaning of Yaakov’s blessing to Yehudah. On the surface, it appears to be a promise of a single future event, but it is not. Rather, it is a promise that has been and is being fulfilled on an ongoing basis. Yaakov promised Yehudah that there will always be someone from among his descendants, i.e. the true Tzaddik of each generation, who will be an aspect or ‘spark’ of Moshe himself, and that this person has the potential of becoming the Mashiach (if the generation merits). But there are still more things we can learn from our Sages of blessed memory.

In the passage from the Zohar referenced above, more secrets are revealed (Zohar Bereshit 25b): לא יָסוּר שֵׁבֶט מִיהוּדָה דָּא מָשִׁיחַ בֶּן דָּוִד. וּמְחוֹקֵק מִבֵּין רַגְלָיו דָּא מָשִׁיחַ בֶּן יוֹסֵף. עַד כִּי יָבוֹא שִׁיל"ה דָּא משֶׁה חֻשְׁבַּן דָּא כְּדָא. וְל"וֹ יִקְהַ"ת עַמִּים אַתְוָון וְלֵוִ"י קְהָ"ת (‘A scepter will not depart from Yehudah’—this is Mashiach ben David—‘nor a lawgiver from between his feet [i.e., from among his descendants]’—this is Mashiach ben Yosef—‘until Shiloh comes’—this is Moshe, the same gematria as Shiloh—‘and the peoples/nations will assemble to him [וְלוֹ יִקְהַת]’—the letters are the same as ‘and Levi Kehat [וְלֵוִי קְהָת]’). This last bit is very fascinating because it means that Yaakov was also alluding to the origins of the soul of Mashiach, i.e., even though he will be a descendant of Yehudah, the soul comes from Moshe through his father Amram, his father Kehat and his father Levi (Yaakov’s son). In other words, the final redeemer will be a combination of Mashiach ben Yosef, Mashiach ben David and Moshe Rabbeinu himself!

R' Natan elaborates in Likutei Halachot (Yoreh Deah, Yayin Nesech 4:12): וְאִתְפַּשְׁטוּתָא דְּמֹשֶׁה בְּכָל דָּרָא וּמְתַקֵּן אֶת יִשְֹרָאֵל בְּכָל דּוֹר וּמְתַקֵּן הַכָּאַת הַצּוּר שֶׁמִּמֶּנּוּ כָּל הַמַּחֲלֹקֶת...וְעִקַּר גְּמַר הַתִּקּוּן יִהְיֶה עַל-יְדֵי מָשִׁיחַ שֶׁהוּא מֹשֶׁה בְּעַצְמוֹ (The [soul] of Moshe is spread out in every generation, to rectify the Jewish People in each generation, and to rectify the sin of striking the rock from which emanates all opposition [against him]…and the ultimate rectification will come through Mashiach, who is Moshe himself).

These sources have answered our question how it can be that Mashiach is greater than Moshe Rabbeinu while the Torah itself says that no one will ever be greater than Moshe Rabbeinu. Mashiach is Moshe—literally! Notice these awesome words from Kochavei Ohr (Introduction to Chochma u’Binah): מוּדַעַת זאת בְּכָל הָאָרֶץ כִּי אָמְנָם לא קָם נָבִיא עוֹד בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל כְּמשֶׁה אֲבָל הוּא בְּעַצְמוֹ עוֹד יָקוּם לְגָאֳלֵנוּ גַּם מֵהַגָּלוּת הַזֶּה כִּי מָשִׁיחַ דָּא משֶׁה וּמַה שֶּׁהָיָה הוּא בְּעַצְמוֹ שֶׁיִּהְיֶה בְּיֶתֶר שְׂאֵת וְיֶתֶר עָז (‘Let this be made known throughout the whole world’ [Yeshaya 12:5]—Because indeed ‘Never again has there arisen in Yisrael a prophet like Moshe’ [Devarim 34:10], but he himself will arise again, to redeem us also from this exile because Mashiach is Moshe, and he will be mightier and more powerful than he ever was before).

Why will he be so much greater than he was before? Because each time his soul was reincarnated throughout time from generation to generation, it received double from the soul of the Tzaddik from the previous generation. We learn this principle from Elisha the prophet. Just before Eliyahu ha-Navi was taken up to heaven in the fiery chariot, he asked Elisha to make one final request of him (2 Melachim 2:9): וַיְהִי כְעׇבְרָם וְאֵלִיָּהוּ אָמַר אֶל־אֱלִישָׁע שְׁאַל מָה אֶעֱשֶׂה־לָּךְ בְּטֶרֶם אֶלָּקַח מֵעִמָּךְ וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלִישָׁע וִיהִי נָא פִּי־שְׁנַיִם בְּרוּחֲךָ אֵלָי (And as they were crossing [the river], Eliyahu said to Elisha, Request what I should do for you before I am taken from you. And Elisha said, May a double-portion of your spirit come upon me). And this doubling would have taken place over and over again with respect to the soul of Moshe Rabbeinu in each generation!

Hopefully now, we can begin to appreciate just how awesome the potential Mashiach must be in our generation.

May our righteous Mashiach be revealed speedily soon in our day to redeem us from this long and painful exile, to sweep away rebellious and arrogant authorities and governments, to restore the sovereignty of the Jewish People in our land, to rebuild our Holy Temple in its place, and to usher in an everlasting age of peace, prosperity and enlightenment for all mankind.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Yitro’s Supposed Conversion to Judaism

On the first aliyah of Parashat Yitro we are told about Moshe's meeting with his father in law, Yitro, and how the former told the later about the wonders the people of Israel experienced until that moment.

וַיְסַפֵּר מֹשֶׁה, לְחֹתְנוֹ, אֵת כָּל-אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה יְהוָה לְפַרְעֹה וּלְמִצְרַיִם, עַל אוֹדֹת יִשְׂרָאֵל: אֵת כָּל-הַתְּלָאָה אֲשֶׁר מְצָאָתַם ב��ַדֶּרֶךְ, וַיַּצִּלֵם יְהוָה.

I dare to say that this is a pretty common moment for those who once were outsiders and now are full members of the tribe. What is perhaps different is that the events are more recent (we are dealing with hundreds of thousands of witnesses), and given his deep bonds with Moshe, there were no reasons to doubt about his son in law's account.

After hearing those wondrous experiences we are told that Yitro blessed God, something we surely can expect from someone whose vocation is on religion, an action that displays his acceptance of what was exposed by his son in law. He then adds a puzzling declaration:

עַתָּה יָדַעְתִּי, כִּי-גָדוֹל יְהוָה מִכָּל-הָאֱלֹהִים: כִּי בַדָּבָר, אֲשֶׁר זָדוּ עֲלֵיהֶם.

There is a widespread belief that Moshe's father in law did convert to Judaism, which in my opinion is hard to sustain despite being so popular. But let’s say that it establishes conversion as a clear consequence of Yitro’s realization.

This claim, at the same time, implies other interesting arguments that we are not going to address. The text itself doesn't give us a lot of information, even the authorized jewish interpretation (The onkelos "translation", though I would call it the most brilliant and concise commentary on the torah) leaves out many details that would be helpful to determine if such event happened, it actually tries to erase any pagan vestige on Moshe's father in law statement:

כְּעַן יָדַעְנָא, אֲרֵי רָב יְיָ וְלֵית אֱלָהּ בָּר מִנֵּיהּ: אֲרֵי בְּפִתְגָמָא, דְּחַשִּׁיבוּ מִצְרָאֵי לִמְדָּן יָת יִשְׂרָאֵל בֵּיהּ דָּנִנּוּן.

In general, the Hebrew Bible doesn't address explicitly "conversion" as we understand it. Even Ruth, the paradigmatic Jewish convert according to our sacred tradition, is not shown as joining formally the Jewish people as we understand it (a formal acceptance of the yoke of the torah and the mitzvot in front of a jewish court) beside her marriage with Boaz, however, unlike Yitro, she actually joins physically the Jewish people moving to the land of Israel which imply that, at least, she became a subject of the Jewish law.

This leaves the possibility that perhaps he did not convert, instead, he kept his status as a non-jew though (if we follow the targum) leaving idolatry.

I don't want to imply that Yitro became a "ben noach" since, in my opinion, professor Jose Faur's insights about this concept are more accurate* than the most popular notion, which I consider senseless. This creates a positive non-sectarian way of approaching the relationship of the non-Jewish world with its creator and opens more possibilities, instead of just constraining (or even denying) the options for those who decide to leave idolatry outside a formal Jewish framework.

--

*Look at his "The Fundamental principles of Jewish Jurisprudence"

1 note

·

View note

Text

der Targum Onkelos und sein Autor Rabbi Aquila – und seine Übersetzung ins Altgriechische

der Targum Onkelos und sein Autor Rabbi Aquila – und seine Übersetzung ins Altgriechische

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Targum#Onkeloshttps://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aquila_(Bibelübersetzer)https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Septuaginta R. Aquila gilt auch als Revisor der griechischen Septuaginta – sprich: lieferte eine radikale Neuübersetzung ins Altgriechische. Es ist davon auszugehen, dass er seine Übersetzung ins Aramäische mit einer ähnlichen Herangehensweise wie seine Übersetzung ins…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Propelling Prayer

“And Israel said to Joseph…Moreover, I have given to you one portion above your brothers, which I took out of the hand of the Emorite with my sword and with my bow.” (Genesis 48:22) With my sword and with my bow = With my prayer and with my supplication. (Targum Onkelos) Why is the bow compared to prayer? Because just as the more one pulls back the bow the further the arrow will fly, so too,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

MISHPATIM

bs'd Shalom. La idea de esta semana de mi libro 'Healing Anger' es: "Cuando una situación potencialmente frustrante se percibe como una lección para mostranos cuán contraproducentes son nuestras expectativas y demandas , en lugar de enojarse en esas situaciones, podremos para utilizarlas como herramientas como retos en nuestro crecimiento como personas". El link para comprar mi libro es http://www.feldheim.com/healing-anger.html Si quieres comprarlo en Israel contactame. Mi revisión semanal llega a más de 5.000 personas en Inglés y Español en todo el mundo. Les ofrezco a todos la oportunidad de compartir la mitzvá de honrar a un ser querido, patrocinando mi Divre Tora, para shelema refua (curación), o shiduj, Atzlaja (éxito). Siéntete libre de reenviar este Divre Tora basado en las ensenanzas del R' Yisajar Frand a cualquier otro correligionario. Disfrutalo y Shabat Shalom. MISHPATIM-¿Qué es la Verdadera Amistad? En la parashá de esta semana, la Torá dice: "Si el buey de un hombre cornea al buey de su prójimo y muere, venderán el buey vivo y dividirán su valor y también el muerto (buey) se dividirá". [1] La Gemara [2] discute extensamente esta ley junto con otras mas que implican daños a la propiedad. La expresión al comienzo de este pasuk es, "veki yigof shor ish et shor reehu ..." que se traduce como "cuando el buey de un hombre cornea el buey de su amigo". Ibn Ezra cita una interpretación de Ben Zuta que ofrece una traducción diferente; las palabras "shor reehu" significa "el buey compañero" del buey que está corneando. No debe traducirse como “el buey de su amigo” que es la traduccion normal, sino más bien “el buey cornea a su amigo”, ¡que es otro buey! Ibn Ezra rechazó la interpretación de Ben Zuta diciendo: "¡el buey no tiene ningún "amigo" que no sea el propio Ben Zuta!" Es decir, cualquiera que diga tal interpretación es un digno compañero de un buey. El concepto de amistad y el de "reeh" [amigo] como "veAhavta lereeja kamoja" [amaras a tu amigo como a ti mismo], solo se aplica a los seres humanos. La amistad es una relación emocional que refleja un aspecto del ser humano. Los animales pueden tener compañeros e incluso parejas, pero el concepto de amistad no es aplicable a ellos, no existe tal cosa. Así el Ibn Ezra rechazó la interpretación de Ben Zuta. Rav Yitzjak Hutner, zt "l, hace la siguiente observación muy interesante: La palabra "reha", que es una de las varias formas de decir "amigo" en hebreo, proviene de la misma raíz que la palabra" terua" en referencia a Rosh HaShana, “Será un día de terua [rompimiento] para ti” [3]. El Targum Onkelos en este pasuk traduce "yom terua" como "yom yevava", que significa un día de gemidos o un día de gritos rotos. Es por eso que el idea principal del sonido del shofar es el "shevarim" (el sonido de lamento roto). Hay una pregunta en Halaja sobre si el verdadero shevarim son los 3 sonidos cortos que llamamos shevarim o la serie de sonidos más cortos que llamamos terua o una combinación de ambos, pero cualquiera que sea su naturaleza, el "shevarim" es la esencia del sonido del Shofar. El sonido de una sola tocada(tekia) que sigue y continua con los "shevarim" simplemente proporciona un marco, por así decirlo, para resaltar la esencia del sonido del shofar: el sollozo del shevarim. Por lo tanto, la etimología de Terua, que comparte la misma raíz que reut [amistad], tiene la connotación de romper algo. Rav Yitzjak Hutner dice que es por eso que un amigo se llama rea: el propósito de un amigo es "rompernos" y "castigarnos". Un verdadero amigo debería detenernos en seco y darnos una palmazo en la espalda, cuando sea necesario. Un amigo no es el tipo de persona que siempre nos da palmaditas carinosas en la espalda y nos dice lo buenos que somos, siempre condonando lo que hacemos. El propósito de un amigo (rea), como es el propósito de Terua (rompimiento del shofar), es decirnos, a veces, "¡estás completamente equivocado!" Esto es algo que incluso el perro más inteligente o cualquier otra mascota jamas podra decirnos. Obviamente, tiene que haber una relación general positiva. Alguien que siempre es crítico no seguirá siendo un amigo por mucho tiempo. Una persona necesita tener confianza en alguien antes de estar preparado para escuchar sus críticas. Pero el tipo que siempre nos da una palmadita en la espalda y nos dice lo bueno que somos, no es un verdadero amigo. Un verdadero amigo debe ser capaz de detenernos y a veces, ser capaz de quebrarnos para nuestro beneficio. [No hace falta decir que esto debe hacerse con tacto y siempre en privado]. En una de las bendiciones de Sheva Berajot (recitada en una boda y durante las comidas de celebración durante la semana posterior), hacemos referencia a la pareja de recién casados como "reim ahuvim" [amigos amorosos]. Hay un mensaje detrás de esta expresión. Para que el Jatan y la Kala / Esposo-Esposa sean "amigos amorosos", necesitan tener la capacidad de poder decirse el uno al otro "esta no es la forma de hacer las cosas, esta no es la forma de actuar”. Obviamente, una relación basada completamente en este tipo de interacción no va a funcionar. Pero si uno lo merece, el tipo de conyugue que encontrará una persona será una "rea ahuva" en el sentido pleno de la palabra "rea". Es por eso que ningún buey tuvo una "rea". Ningún buey le dirá nunca a su buey compañero "No es correcto comer así" o "Estás comiendo demasiado o demasiado rápido". Un verdadero amigo tiene que hacer eso. Del mismo modo, el Netziv dice en el pasuk, "Un compañero de ayuda frente a él" [Bereshit 2:18] que a veces para que una persona sea una ayuda (ezer), el otro necesita ser su oponente (kenegdo). No debería ser solo "Cariño, eres genial" y "Mi amor, siempre tienes la razón". A veces debe ser "¡Cariño, estas totalmente equivocado!" Esta es la verdadera instancia de "reim ahuvim". Una persona madura da la bienvenida a la crítica constructiva y pone su crecimiento espiritual delante de su ego. Siempre deberiamos entender que un verdadero amigo ofrece una reprimenda porque él / ella es un mensajero de Hashem, enviado para que nos enfoquemos en nuestras deficiencias. Por lo tanto, no debemos rechazar las críticas de un amigo, ya que si lo hacemos, realmente estamos detestando la reprimenda personal de Hashem. [4] Que todos merezcamos tener una amistad verdadera con nuestros compañeros y con nuestros cónyuges. ____________________________ [1] Shemot 21:35 [2] Ver el principio del tratado de Bava Kama. [3] Bamidbar 29:1 [4] Mili DeAvot en Avot 6:6 Le Iluy Nishmat Eliahu ben Simja, Perla bat Simja,Yitzjak ben Perla, Shlomo Moshe ben Abraham, Elimelej David ben Jaya Bayla, Abraham Meir ben Lea, Gil ben Abraham. Zivug agun para Gila bat Mazal Tov, Elisheva bat Malka. Refua Shelema de Jana bat Ester Beyla, Mazaltov bat Guila, Zahav Reuben ben Keyla, Elisheva bat Miriam, Mattisyahu Yered ben Miriam, Naftali Dovid ben Naomi Tzipora, Yehuda ben Simja, Yitzjak ben Mazal Tov, Yaacob ben Miriam, Dvir ben Lea, Menajem Jaim ben Malka, Shlomo ben Sara Nejemia, Sender ben Sara, Dovid Yehoshua ben Leba Malka yYitzjack ben Braja. Exito y parnasa tova de Daniel ben Mazal Tov, Debora Leah Bat Henshe Rajel, Shmuel ben Mazal Tov, Jaya Sara Bat Yitzjak, Yosef Matitiahu ben Yitzjak, Yehuda ben Mazal Sara y Yosef be Sara, Nejemia Efraim ben Beyla Mina.

0 notes

Photo

Continue, You Must Redouble Your Wholesome Efforts

Daily Study Chumash with Rashi Parshat Shemini Tuesday, 17 Nissan 5781 / March 30, 2021

https://www.chabad.org/dailystudy/torahreading.asp?tdate=3/30/2021#auto=video&author=13568&index=1

download audio; https://www.chabad.org/multimedia/filedownload_cdo/aid/1482208

Leviticus Chapter 9 24

And fire went forth from before the Lord and consumed the burnt offering and the fats upon the altar, and all the people saw, sang praises, and fell upon their faces. and sang praises: Heb. ויַָּרֹנּוּ, as Targum [Onkelos] renders it [namely, “and they praised” God]. Leviticus Chapter 10 1And Aaron's sons, Nadab and Abihu, each took his pan, put fire in them, and placed incense upon it, and they brought before the Lord foreign fire, which He had not commanded them. 2And fire went forth from before the Lord and consumed them, and they died before the Lord.

-

Tuesday: Managing Ecstasy Third Reading: Leviticus 9:24–10:11 Translated and Adapted by Moshe Wisnefsky

https://www.chabad.org/dailystudy/dailywisdom.asp?tdate=3/30/2021

After Aaron’s blessing and Moses’ prayer, fire did descend from heaven and consume the parts of the sacrifices that had been placed on the Altar. When the Jewish people saw this, they were ecstatic that G‑d’s presence appeared to them again openly. Their efforts in donating material for the Tabernacle and working diligently in constructing it, as well as their inner “work” of repenting for the incident of the Golden Calf, had born fruit. But then, two of Aaron’s four sons, Nadav and Avihu, offered up some incense on their own initiative. To everyone’s horror, Divine fire again descended, but this time in the form of two pairs of flames that entered Nadav’s and Avihu’s nostrils, killing them instantly.

Managing Ecstasy

A fire went forth from before G‑d and consumed them.

Leviticus 10:2

Nadav and Avihu were swept up in the ecstasy of the moment. In their intense desire to cleave to G‑d, which they expressed through their unauthorized incense offering, they rose through spiritual heights even as they felt their souls leaving them. From this perspective, their death was not a punishment but a fulfillment of their wish to dissolve into G‑d’s essence.

Nevertheless, we are not intended to imitate their example; on the contrary, we are expressly forbidden to pursue such suicidal spiritual rapture. Although it is necessary to seek inspiration and renew it constantly,

the purpose of reaching increasingly higher planes of Divine consciousness is to bring the consciousness that we acquire down into the world, thereby making the world increasingly more conscious of G‑d, transforming it into His home.1

0 notes

Photo

Numbers with Aramaic Targum and Arabic Tafsir, [Yemen: 14th century]

An early copy of most of the book of Numbers in which every biblical verse is followed first by its Aramaic Targum and then by the Arabic Tafsīr.

In the Second Temple period, with Jewish knowledge of Hebrew in decline, an acute need was felt for the translation of the Scriptures into the vernacular. The two most famous ancient Jewish versions, the Greek Septuagint (third-second centuries BCE) and the Aramaic Targum (first-second centuries CE), would give generations of the faithful access to biblical law, legend, and wisdom. Following the seventh-century Muslim conquest of large swaths of the Middle East, however, Arabic became the lingua franca of much of the Jewish world. Having been asked sometime in the early tenth century to render the Bible into Arabic, Rabbi Saadiah Gaon proceeded to compose the Tafsīr (lit., commentary), a semi-free literary translation.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The One and Only Word Echad

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל ה’ אֱלֹקֵינוּ ה’ אֶחָד (דברים ו, ד)HEAR, O ISRAEL: HASHEM IS OUR G-D, HASHEM IS ONE. (DEVARIM 6:4)

This verse expresses Judaism’s cardinal principle: belief in the singular existence of G-d. The deeper meaning of this “oneness” is that not only is there no deity other than G-d, but G-d is the one and only true existence. I.e., nothing exists outside of Him. Since G-d’s will is the cause of any and all existence, the true identity of every being is the will of G-d that is continuously causing it to exist (see Tanya, Shaar HaYichud V’HaEmunah, at length.)

This idea is hinted to by the Hebrew word echad, “one,” spelled אחד. The numerical values of its three letters are one, eight and four, respectively. The ח, equaling eight, is symbolic of the seven skies and one earth (see Sefer Mitzvos Katan #2). The ד, equaling four, represents the four directions—north, south, east and west. The א, which equals one, represents our singular G-d, Who is Master over all that exists in heaven and earth and in all four directions (Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 61:6).

This demonstrates the difference between Lashon Hakodesh—the sacred language of the Torah, and all other languages. The ten utterances with which G-d created the world (see Mishnah, Avos 5:1), were stated in Lashon Hakodesh (Rashi, Bereishis 2:23). Hence, words in Lashon Hakodesh are not arbitrary; each word reflects the Divine energy animating the particular object it refers to, and captures the essential character of that object. In contrast, all other languages form by human consensus; the words do not reflect the essential nature of the articles or ideas to which they refer (see Shnei Luchos Habris 3a).

This is evident in the Aramaic translation of the word one,chad, as rendered by Targum Onkelos on this verse. The word chad contains a ח and a ד, representing all of creation, as explained above, but it is missing the א, which represents G-d. Though the meaning of the word chad is “one,” and in this context expresses the idea of G-d’s singular existence (just as the word echad does), the truth of this oneness is not as obvious and revealed in the Aramaic word as it is in Lashon Hakodesh.

—Toras Menachem 5743, vol. 1, p. 264

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biblical Studies Carnival for July 2020

Biblical Studies Carnival # 173,

An odd, deficient, odious, but balanced prime.* July 2020.

I, your host, did a carnival in February of this year just around Mardi Gras. I closed that carnival with the Quartet for the End of Time. Little did we know what was coming our way, though we had seen early warning signs. Let this carnival be heralding the beginning of the end of the disaster that is upon us. Let it be that we realize how critical is our support of each other, our 'mutual responsibility and interdependence', and how foolish is the thought, and all its attendant actions, that freedom belongs to the individual at the expense of the whole body. Fun? Enjoyment? Carnival atmosphere? Gaiety? Song and Dance? Unlikely, but let's see if some Immersive Distraction is worth the try.

Tanakh.

Michael Avioz writes on translation of place names in Targum Onkelos which

... became so popular in Babylonian rabbinic circles that the Babylonian Talmud requires Jews to read it every week together with the weekly portion, in the law known as שניים מקרא ואחד תרגום, “[read] scripture twice and the translation once” (b. Ber. 8a).

Hagar

Ariel Kopilovitz explores through a review of the war against Midian how the priestly Torah was compiled. Abdulla Galadari explores the intertextual connections of the Quran with the Shema. David Ben-Gad HaCohen explores the region of Ar-Moab. The Velveteen Rabbi comments on man, woman, and vows in parashat Matot. Nyasha Junior reimagines Hagar in her book on Blackness and the Bible. Lawrence Hoffman sends an open letter to his students outlining 5 valuable principles to be learned from 'tradition' and putting them in the context of Amalek and the current stresses on social order.

Thirty years ago, while researching an article on the subject, I asked my teacher and colleague, the late Harry M. Orlinsky, to define “tradition” and he replied, “Tradition is just a lie going back at least a century.”

Your host continues to dig into the music embedded in the text of the Hebrew Bible. Here is an English arrangement and a Hebrew performance of Genesis 22. On the governance of the Body, Pete Ens begins the month with using the Bible to support ...

The stories of Israelite kings match the Trump presidency remarkably well. And the condemnation of their actions by biblical authors is persistent to the point of being tedious.

Elkanah and his wives (I Samuel)

Laura Quick considers the bed of Og the King of Bashan. (Remembering Remnants of Giants, last seen in 2019.) The Medieval Manuscripts blog shows some Old Testament passages from the Rochester Bible. Francis Landy introduces the Prologue to Deutero-Isaiah.

The seven Sabbaths following Tisha B’Av, the fast day commemorating the destruction of the First and Second Temple, are known as שבעה/שב דנחמתא “the seven [Sabbaths] of Consolation.” All the haftarot are taken from Isaiah 40-66, the work of an anonymous exilic prophet (or prophets), who expresses hope for the future rebuilding of Judea and repatriation of its people.

Doug Chaplin gives us a draft prayer card inspired by Jeremiah 12:1 as used by Gerard Manley Hopkins, in his poem “send my roots rain”. Jim Gordon continues his poetry series with A poem for the Sabbath, by Wendell Berry, a little different from Psalm 92. Carmen Joy Imes praises the laments and imprecatory Psalms.

Mark Whiting writes on penitential wisdom in the penitential psalms. The Hebrew versions of the five poems in the book of Lamentations are riddled with debated readings... It's not very often that Lamentations as poetry gets a mention. A real rabbi now with greying whiskers, and also a poet, Rachel Barenblatt, teaches about feelings in this time of destruction as the period of approach to Tisha B'av.

I'm finding it difficult to face Tisha b'Av this year, in part because every time I read the newspaper feels like Tisha b'Av. There's mourning and grief and loss everywhere I look.

Ah in such solitude sits the city. Abundant with people she is as a widow. Abundant from the nations, noble among the provinces, she is into forced service.

Andrew Perriman continues a four year conversation on redefining Daniel. Is there a Unity amidst this diversity. A question by Anthony Ferguson on the state of the text of the Old Testament.

I am going to discuss the non-aligned manuscripts. I hope to show that these manuscripts are largely secondary and dependent on an MT-like text.

Hebrew language: Your host is beginning a series on explaining the transformation of pointed text into 'spelling lacking niqqud' here and here.

Slave

Jonathan Orr-Stav addresses the difficulties of rendering the cantillation in standard characters. In these days of deception, you might enjoy this note on clothing from David Curwin of Balashon. Archaeology: Jim Davila links to a report on seals that may show more about the gradual resettlement and bureaucracy in Jerusalem after its destruction in 586 BCE. He also points out a deep excavation under Jerusalem. Matthew Susnow explores the ancient temples with an essay on What is a ‘House of a God’? Airton José da Silva links to articles on the administrative storage centre from the time of Hezekiah and Manasseh. Ian Paul offers an essay on 'good'.

for all the wondrous joy of this claim about goodness, Genesis 1 chooses not to say ‘it was perfect’.

Canonical Edges

James McGrath reports from day 2 of the Enoch Seminar on the origins of evil.

Cosmic

Day 3 continues here and here from Jim Davila. Day 4 concludes with a response from Jim Davila and a plug for 1 Enoch as Christian Scripture. In James McGrath's report we read of:

degeneration of the generations, i.e. that evil doesn’t come into the world in one fell swoop but gradually over time, and involved(s) groups rather than individuals,

James Tabor reflects on the good and the ugly. Andrew Perriman draws us into cosmic thinking and then back to political reality. If you are hungry, watch this. Making 2000 year old bread. Absolutely marvelous technique.

New Testament

Having mentioned targum for Tanakh, I am reminded of targuman. Christian Brady is now very active in parish work, and posts on drinking the cup. Timothy Lewis asks why some mothers are included and not others in Matthew's first chapter. Bosco Peters continues his Matthew in Slow Motion, Episode 33. Ian Paul writes on the lectionary and the parable of the sower. Jim Gordon writes on invincible ignorance.

"I don't know how to explain to you that you should care for other people." (Dr Anthony Fauci)

Marg Mowczko meditates on meekness in warhorses.

Sickle

In an essay on John as the mundane gospel, Paul Anderson demonstrates now much mundane detail is in John's Gospel. Trinities posts a podcast with Daniel Boyarin on the prologue to John's gospel. Christopher Page continues a series of posts, #86, (and counting) on living with Jesus through the words of John's Gospel. Michael Bird cites Harold Attridge on the beloved disciple. Adele Reinhartz vs. Chris Keith and James Crossley, an online discussion of her book addressing the thesis of Lou Martyn on 'being cast out of the covenant'. Gary Greenberg posts on the case for a proto-gospel and the healing of a blind man in Bethsaida. (via FB and Dr Johnson Thomaskutty. And here is a lecture on the signs in the gospel of John from the Church of South India. Jason Staples writes on 'Reconstituting Israel: Restoration Eschatology in Early Judaism and Paul’s Gentile Mission.'. Second installment here. Andrew Perriman puts glossolalia into a historical framework that "Jerusalem faces a catastrophic judgment".

The gift of speaking in other tongues signifies the extension of Joel’s prophecy beyond geographical Israel to include all Jews who looked to Jerusalem as the centre of their religious life and practice. The city and its spectacular temple would soon be destroyed.

Eyal Regev asks if Christians mourned the destruction of the temple. And if you have forgotten what prosopological means, here's a reminder. James Tabor reminds us with a paper from the 1980s about Paul's words on apotheosis. Christopher Page seems to double this thought with his mid-month 100th pandemic post on Jesus. And to continue the subject, Ian Paul asks what to think of AI. (Homo Deus?) What's in the translator's choices of gloss? Brent Niedergall posts on temptation vs trial. Brian Small notes that Cyril's lost commentary on Hebrews has been found. CSCO has a number of notes on the Oxford Handbook of Pauline Studies. Phillip Long continues his series on Revelation with questions on 'the son of man' and 'the harvests' and 'the final visions'. James Tabor reflects on washed in the blood of the lamb. For another take on Revelation as an orchestral score, and with respect to more recent historical contexts, see Ian Paul on the present crisis. Derek Demars argues that Revelation is a musical!

Miscellaneous

Family

Marc Goodacre teaches by example about fatigue

... one can see an author making characteristic changes to a source at the beginning of a passage, only to lapse into the wording of the source later on.

Jim West has posted Larry Schiffman's lecture on the DSS here. Airton José da Silva announces a new Bible.

Brazilian translation of the famous French “Traduction Oecuménique de la Bible” (TOB) (according to the 12th ed., 2010). It is the model of ecumenical translations, because of the interfaith composition of its collaborators and because it even adapts, for the Old Testament, the Jewish sequence of biblical books. It is an excellent study bible, with rich notes and many references of parallel texts.

And here is an insight into the culture of Biblical Studies in Brazil. Brent Niedergall points to a paper on the CBGM as material for the upcoming virtual SBL annual meeting. And for more on CBGM, see Brent Nongbri's article here. The cosmologist Bishop of Rhode Island, Nicholas Knisely, expresses a hope that we can go beyond our self-images, on his blog, Entangled States. More than a little uncertainty in the referent in the blog name. James McGrath writes on Academic genealogies. Ken Schenck continues his review of the works of his doctoral advisor, Jimmy Dunn, finishing on the twelfth day. Helen Bond remembers Jimmy Dunn. James Tabor traces his history of learning Greek from age 17 to 74. This spring chicken explains how 'older is not better', and that Westcott and Hort are seen by some today as part of 'a “plot from hell” to destroy God’s truth'. (See also a later version here.) This post on his 'first book' is too good to pass up. The first week of July presented several posts which seemed to be strong on issues peripherally related to the Bible, but grounded in the questions raised by our persistence with its content: So a note by Ian Paul on the priesthood (presbyter), running the risk of self-justification but showing the stuff of Cranmer, and on the meaninglessness of life in response to facing death, by Christopher Page, and on manufacturing belief, a documentary in which many famous appear, noted by Bart Ehrman. There is even a commentary by OUP on being prepared. Nicely juxtaposed is Phillip Long's note for the day on the winepress. Westar Think Tank Fellow, Terrence Dean interviews Nontombi Naomi Tutu: Five current questions. On issues of gender in Biblical Studies, note this discussion with the title, Sarah Rollens and Candida Moss vs Chris Keith here.

Books

Abel Mordechai Bibliowicz has made a pdf available on Jewish-Christian Relations-The First Centuries.

Bart Ehrman talks about his book, Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife, in a long podcast on Reason and Theology. (Take care with whom you chose to spar.) His blog also has a guest post by Cavan Concannon on the Bible Museum.

Not to be outdone, Tyndale house is starting a new podcast series on Trusting the Bible.

April Deconick notes a new book on Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism.

Marg Mowczko notes a new book Holding Up Half the Sky.

Stephen Nadler reviews Spinoza.

Reuven Chaim Klein reviews Pharoah, Biblical History, Egypt, and the Missing Millennium, reworking the chronology of traditional Egyptology.

Jim Davila highlights a review of Fredriksen's When Christians were Jews. A good review that I missed from last month's feeds. A good book, too, I am sure.

Brent Niedergall reviews The Greek of the Pentateuch by John A. L. Lee.

Richard Briggs reviews John R. Levinson's The Holy Spirit before Christianity

In a study that is both poignant and provocative, Levison takes readers back five hundred years before Jesus, where he discovers history’s first grasp of the Holy Spirit as a personal agent. The prophet Haggai and the author of Isaiah 56–66, in their search for ways to grapple with the tragic events of exile and to articulate hope for the future, took up old exodus traditions of divine agents―pillars of fire, an angel, God’s own presence―and fused them with belief in God’s Spirit. ... Like most (if not all?) good New Testament ideas, the Old Testament got there first.

Unavoidable

In Memoriam: Alister McGrath has written an obituary for James Packer, certainly a man of some influence and who was known by many in the far west of Canada including former blogger, Suzanne McCarthy most recently of BLT, not just a sandwich. (I knew I could get a bit more poetry in this carnival somehow. I'd rather have good poetry than bad tattoos with lots of ads any day.) ... August is coming up, not April, that cruelest month ...

Next Carnivals

Phil is always looking for volunteers. Fun or not, spending a month actually reading the bloggy scholars and the scholarly blogs is an education... Occasionally, people actually suggest posts too. Chris Brady began the month with a post comparing Facebook to the old blogging community with vigorous discussion of issues in the comments and among the blogs. He also announces the upcoming virtual SBL.

August 2020 – Phillip Long, Reading Acts

September 2020 – Brent Niedergall (who is beginning a video series on James.)

* Footnote: (For the numerologists.) from Blogger https://ift.tt/3fiigze via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

A post about the significance of our words

and the way we use language to express ourselves as shared this evening by John Parsons:

Just as the body can become sick with illness, so can the soul: "I said, 'O LORD, be gracious to me; heal my soul (רְפָאָה נַפְשִׁי), for I have sinned against you'" (Psalm 41:4). Likewise we understand that fear influences the way the brain processes images and messages. And since the mind and body are intricately interconnected, fear is often the root cause of many physiological problems such as heart disease, high blood pressure, clinical depression, and other ailments. Left unchecked, fear can be deadly. Note the connection between fear, lashon hara (evil thoughts/words), and sickness (tzara’at), which are themes of this week's Torah portion...

The targum Onkelos states that God breathed into Adam the ability to think and to speak. In other words, thought and speech are two primary characteristics of the image (tzelem) and likeness (demut) of God. Since our use of words is directly linked to the "breath of God" within us, lashon hara (לָשׁוֹן הָרָה) defaces God's image within us.... Using words to inflict pain therefore perverts the image of God, since God created man to use language to "build up" others in love. This is part of the reason the metzora (i.e., one afflicted with tzara’at) was regarded as “dead” and in need of rebirth.

Lashon hara (evil speech) is really a symptom of the “evil eye” (ayin hara). “Evil comes to one who searches (דָּרַשׁ) for it” (Prov. 11:27). We must train ourselves to use the “good eye” (ayin tovah) and extend kaf zechut (כַּף זְכוּת) - the “hand of merit” to others. Genuine faith is optimistic and involves hakarat tovah, that is, recognizing the good in others and in life’s circumstances. Gam zu l’tovah: “This too is for the good” (Rom. 8:28). The Midrash states that God afflicted houses with tzara’at so that treasure hidden within the walls would be discovered. The good eye finds “hidden treasure” in every person and experience.

King David said (Psalm 35:13): “May what I prayed for happen to me!” (literally, tefillati al-cheki tashuv - “may it return upon my own breast”). Some of our prayers are conscious words spoken to God, whereas others are unconscious expressions of our inner heart attitudes. When we harbor indifference, ill will, or unforgiveness toward others, we are only hurting ourselves. It is very sobering to realize that our thoughts are essentially prayers being offered up to God... When we seek the good of others we find God’s favor, healing and life. Yeshua spoke of "good and evil treasures of the heart" that produce actions that are expressed in our words (Luke 6:45). A midrash states that if someone speaks well of another, the angels above will then speak well of him before the Holy One.

In light of the enigma of “spiritual impurity” (i.e., tumah) and its ultimate expression revealed in the corruption of death, it is all the more telling that we should heed the cry of the Spirit: "Choose Life!" (Deut. 30:19). מָוֶת וְחַיִּים בְּיַד־לָשׁוֹן - "Death and life are in the power of the tongue" (Prov. 18:21). Sin is a type of "spiritual suicide" that seduces us to exchange eternal good for the petty and trivial. The nachash (serpent) in the garden of Eden was the first to speak lashon hara. He slandered God and lied to Eve about how to discern between good and evil. He is a murderer and the father of lies. Resist his wiles with the truth of God...

May it please the LORD to help each of us be entirely mindful of the power and sanctity of our words... May it please Him to help us use our words for the purpose of strengthening and upbuilding (οἰκοδομὴν) one another (Eph. 4:29). May God help us take every thought “captive” to the obedience of the Messiah, thereby enabling us to always behold and express the truth of God’s unfailing love. [Hebrew for Christians]

4.24.20 • Facebook

0 notes

Text

MISHPATIM

bs'd

Shalom.

The thought of this week of my book Healing Anger is

"When a potentially frustrating situation is perceived as a lesson to show us how counterproductive our expectations and demands are, instead of becoming angry in those situations, we will be able to utilize them as tools for challenge and growth."

Buy my book at http://www.feldheim.com/healing-anger.html

If you want to buy it from me in Israel let me know.

This article is based on the teaching of R' Yissachar Frand.

You have the opportunity to share in the mitzvah to honor a loved one by sponsoring my weekly review, or refua shelema (healing), shiduch, Atzlacha (success).

To join the over 4,000 recipients in English and Spanish and receive these insights free on a weekly email, feedback, comments, which has been all around the world, or if you know any other Jew who is interested in receiving these insights weekly, contact me. Shabbat Shalom

MISHPATIM-What is True Friendship?

In this week's parsha the Torah says “If the ox of a man will gore his fellow man’s ox and it dies they will sell the live ox and split its value and also the dead (ox) shall be split.” [1] The Gemara [2] discussed at length this law, along other laws involving damage to or by one’s property.

The expression at the beginning of this pasuk “veki yeegof shor ish et shor re-ehu…” is translated “When a man’s ox will gore his friend’s ox”. Ibn Ezra quotes an interpretation from Ben Zuta who offers a different translation; the words “shor re-ehu” mean the “fellow ox” of the ox who is goring. It is not to be translated as “the ox of his friend” as we normally translate but rather “the ox gores his friend”, which is another ox!

The Ibn Ezra dismissed the interpretation of Ben Zuta by saying, “the ox has no ‘friend’ other than Ben Zuta himself!” Meaning, anyone who says such an interpretation is a worthy companion to an ox.

The concept of friendship and the concept of “re-ah” [friend] as in “veAhavta lere-echa kamocha” [you should love your friend as yourself], only applies to human beings. Friendship is an emotional relationship that reflects an aspect of humanity. Animals can have companions and they can even have mates, but the concept of friendship is not applicable to them, there is no such thing and Ibn Ezra dismissed this interpretation.

Rav Yitchak Hutner, zt”l, makes the following very interesting observation: The word “reha,” which is one of several ways of saying “friend” in Hebrew comes from the same root as the word “teruah” as referring to Rosh HaShannah, “It shall be a day of teruah [blasting] for you” [3]. The Targum Onkelos on this pasuk translates “yom teruah” as “yom yevava”. “Yom yevava” means a day of moaning, or a day of broken up cries.

That is why the main thrust of the shofar sound is the “shevarim” (the broken wailing sound). There is a question in Halacha as to whether the true shevarim is the 3 short sounds we call shevarim or the series of shorter blasts that we call teruah or a combination of both, but whatever its nature, the “shevarim” is the essence of the shofar blowing. The single blast sound (tekiah) that proceeds and follows the “shevarim” merely provides a frame, so to speak, to highlight the essence of the shofar sound – the sobbing cry of shevarim.

Thus, the etymology of Teruah, sharing the same root as reut [friendship] has the connotation of breaking something up. Rav Hutner says that is why a friend is called reah – the purpose of a friend is to “break you up” and to “give you chastisement”. A true friend should stop us in our tracks and give us a kick in the pants, when necessary. A friend is not the type of person who always pats us on the back and tells us how great we are, always condoning whatever we do. The purpose of a friend (reah), as is the purpose of Teruah (shofar blast), is to tell us, sometimes, “you are completely wrong!” This is something that even the smartest dog or any other pet can tell us.

Obviously, there has to be an overall positive relationship. Someone who is always critical will not remain a friend for very long. A person needs to have trust and confidence in someone before he is prepared to hear criticism from him. But the fellow who always slaps us on the back and tells us how great we are is likewise not a true friend. A true friend must be able to stop us and sometimes be able to break us for our benefit.[Needless to say the this has to be done in a pleasant tone of voice, with serenity and in private].

In one of the blessings of Sheva Berachot (recited at a wedding and during celebration meals for the week thereafter), we make reference to the newlywed couple as being “reim ahuvim” [loving friends]. There is a message behind this expression. In order for a Chatan-Kallah / Husband-Wife to be “loving friends,” they need to have the capacity to be able to say to each other “this is not the way to do it; this is not the way to act”. Obviously, a relationship in which this is the entire basis of their interaction will not funtion. But – if one is deserving of it – the type of spouse a person will find will be one who will be a “reah ahuva” in the full sense of the word “reah”.

This is why no ox ever had a “reah”. No ox will ever tell its companion ox “It is not right to eat like that” or “You are eating too much or too fast.” A true friend has to do that.

Similarly, the Netziv says on the pasuk, “A helpmate, opposite[against] him” [Bereshit 2:18] that sometimes a person can best be a helper (ezer), by being an opponent (kenegdo). It should not just be “Honey, you’re great” and “Honey, you are always right.” Sometimes it must be “Honey, you are totally wrong!” This is a true instance of “reim ahuvim”.

A mature person welcomes constructive criticism; he puts his spiritual growth ahead of his ego. Let us always understand that a true friend offers rebuke because she/he is a messenger of Hashem, sent to make us focus on our shortcomings. Thus, we should not reject a friend’s criticism, for if we do so, we are really detesting Hashem’s personal rebuke.[4] May we all merit having true friendship with our companions and specially between ourselves and our spouses. ____________________________ [1] Shemot 21:35 [2] See beginning of Tractate Bava Kamma. [3] Bamidbar 29:1 [4] Mili DeAvot on Avot 6:6

Le Iluy nishmat Eliahu ben Simcha, Mordechai ben Shlomo, Perla bat Simcha, Abraham Meir ben Leah, Moshe ben Gila,Yaakov ben Gila, Sara bat Gila, Yitzchak ben Perla, Leah bat Chavah, Abraham Meir ben Leah,Itamar Ben Reb Yehuda, Yehuda Ben Shmuel Tzvi, Tova Chaya bat Dovid.

Refua Shelema of Mazal Tov bat Freja, Zahav Reuben ben Keyla, Yitzchak ben Mazal Tov, Elisheva bat Miriam, Chana bat Ester Beyla, Mattitiahu Yered ben Miriam, Yaacov ben Miriam, Yehuda ben Simcha, Menachem Chaim ben Malka, Naftali Dovid ben Naomi Tzipora, Nechemia Efraim ben Beyla Mina, Dvir ben Leah, Sender ben Sara, Eliezer Chaim ben Chaya Batya, Shlomo Yoel ben Chaya Leah, Dovid Yehoshua ben Leba, Shmuel ben Mazal Tov, Yosef Yitzchak ben Bracha. Atzlacha and parnasa tova to Daniel ben Mazal Tov, Debora Leah Bat Henshe Rachel, Shmuel ben Mazal tov, Yitzchak ben Mazal Tov, Yehuda ben Mazal Sara and Zivug agun to Gila bat Mazal Tov, Naftali Dovid ben Naomi Tzipora, Elisheva bat Malka. Pidyon anefesh-yeshua of Yosef Itai ben Eliana Shufra.

0 notes

Photo

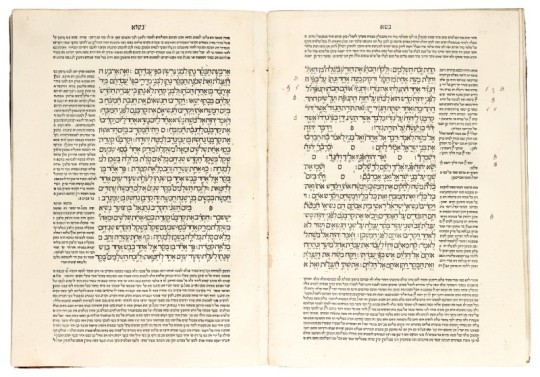

Torah with the Targum of Onkelos and commentary of Rashi, edited by Joseph Hayyim ben Aaron Strasbourg Zarfati. Bologna: Abraham ben Hayyim, 25 January 1482

The Hebrew text is elegantly framed by the Targum of Onkelos in Aramaic to the side, and the commentary of Rashi at head and foot. Rashi's eleventh-century commentary on the Torah had been one of the first Hebrew books ever printed, in Rome in c. 1469-72, and was regularly reprinted; it also proved influential on later commentators such as Nicolaus of Lyra. The Targum of Onkelos, attributed to the first-century Roman convert to Judaism, is the authoritative paraphrase of the text into a western dialect of Aramaic (probably in Palestine, with subsequent Babylonian influence), and was considered important for the interpretation of the original Hebrew. The edition was proofread by Joseph Hayyim Zarfati, who also wrote the colophon.

The printing of Hebrew is hampered by the same problems as printing in Greek, with numerous diacritics (vowel points in Hebrew) to be accommodated; this is the first book printed with the Hebrew text fully vocalised and with cantillation marks. "It constitutes a remarkable technical achievement" (A. Offenberg, A Choice of Corals, 1992, p.141); Offenberg goes on to observe that it took Italian printers another ten years or so to develop a similarly successful Greek type face. [x]

33 notes

·

View notes