#ta’nehisi coates

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates was an incredible read. Coates grew up in Baltimore as a black man who attended Howard University. In this memoir written to his son, he refers to his “body” and the ways it has been damaged and disrespected by American society. His memoir illuminates the issue of race in America by creating a unique and captivating narrative of his personal experiences.

#ta’nehisi coates#book#memoir#book nerd#bookaddict#booklover#books#bookworm#bookstagram#bookblr#bookish#reading#race in america#black lives matter#readthisnow#black rights#baltimore#howard university#race and ethnicity#book review#book recommendations#nonfiction

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tag Game

Tagged by: @lenaoberdorf-fc and @sharpicefire

Rules: Answer 17 questions + tag 17 people

Nicknames: Ally

Zodiac: Libra

Height: 5’3”

Hogwarts House: Ravenclaw

Last thing I googled: WNBA Schedule

Song stuck in my head: Exile-- Bon Iver and Taylor Swift

Amount of sleep: 5-10 hours depending on a variety of things.

Lucky Numbers: no specific lucky number, but I like prime numbers in general. And multiples of 10.

Dream job: Traveler

Wearing: pajamas

Fave instrument: bagpipes or pipe organ

Aesthetic: Trinity College Dublin library on a rainy day. Or a potato.

Fave song: This is very hard cause I love music, and favorites depend on my mood.

Fave author: ooh, also hard. Ta’Nehisi Coates, Aubrey Coulhurst, and Natasha Ngan are current favorites. And Shakespeare is also (mostly) good (yes, I am that nerd. Fight me.)

Fave Animal: Elephants! (Also unicorns and dragons.)

Fave animal sound: purring in general, and also cheetah chirps and the short little trumpeting noises elephants make

Random: I had two extra wisdom teeth (6 total) but when they put me under for the surgery they didn’t give me extra anesthesia so I was starting to wake up before they were done and felt them pull out the last wisdom tooth.

If you see this and want to participate, consider yourself tagged!

#about me#a little unclear on the whole ~aesthetic~ thing#but that library is beautiful and I would like to live there#and also potatoes are amazing because potatoes#I have a whole thing about numbers yet no actually specific lucky number#While I do really love Shakespeare I absolutely DO NOT LOVE ROMEO AND JULIET#I will carry that hatred well past my grave

1 note

·

View note

Text

You are a snake, and so am I.

Everything we do, we do to validate a story about reality that is premised on a delusion. Our self concept is a series of fictions that we maintain to keep us more or less stable.

1. I am in a loving and happy relationship. People respond to tones and actions of others in unique ways. As we get more familiar in our relationships, we learn the triggers of others. We learn what pushes their buttons, what makes them loving and soft, what makes them confident. We learn that our friends give us more attention when we’re in a crisis situation, when we’re confident and outgoing, when we’re listening attentively. We become very familiar with the behaviours that elicit certain emotions in those close to us. My boyfriend gives me most attention when I’m sad, maternal, or independent. My friend gives me most attention when I have an exciting new idea that is intellectually stimulating. My friend gives me most attention when I show sympathy and am deeply attentive. My boyfriend pushes me away when I’m needy, jealous, or stressed.

We become deeply familiar with these dynamics. We amplify certain behaviours to elicit the desired response. We manipulate the people we’re close to. We want the reassurance that our relationships are a certain way, so we do things to validate those ideas. But it is manipulation to sustain a fiction. We want to bring out the qualities in others that will conform more or less to the version of reality that we subscribe to.

2. I had the idea that if I ate whatever I wanted when I wanted, and succumbed to any craving, that I would gain an exception amount of weight and be horribly unattractive. I sustained this fiction by conforming closely to what I believed I had to do stay the weight I wanted. Why did I want this weight? Because it fit into my self concept. I am healthy, fit, slim, and am generally the thinnest girl in most settings. This body image was deeply integrated into my self concept. I stopped conforming to those ideas. I eat whatever I want, eat a lot of pizza, chocolate, fried chicken, coffee with milk and sugar, and I can’t gain weight. I stay within this range. When we do challenge the behaviours we believe we need to sustain our self concept, it is not only enlightening, but baffling. When you have experiences that show that the stories you have been accepting are premised on complete fictions, this is humbling. Because we don’t know why we do the things we do.

3. I read a paper that references Ta’Nehisi Coats. From intellectuals I respect, I’ve come to accept that his ideas are radical, post modern, and conform to an intellectual tradition I do not like. Have I read anything by him? No. But I have this idea of myself, as a centrist. I am critical to a lot of post-modern thought, and I don’t respect the tradition because I reject the principles it is premised on. But to discredit a thinker on the basis that those who think like me discredit him is ridiculous. But I do so because I have a self concept that identifies with a specific intellectual tradition. Of course, self deception and simplification is useful because it means you don’t have to inquire into everything. This makes life easier. Dealing with complexity and dwelling in the unknown is challenging. Identification is comforting. It allows you to have trust. But it is dangerous.

4. I believed that men preferred thin and fit women. Because the men who I’ve been with have been attracted to me, I am thin and fit, therefore I accepted the premise that men like thin women. My boyfriend likes big girls. I was so confused and baffled by this information, because it disconfirmed an idea I had latched onto my whole life. Again, this shattered my fiction, and shook my self concept as proximating an ideal. It made me consider, maybe I am not that attractive.

5. I have a self concept about being pulled together, looking wealthy and clean. Whenever I have messy hair, when my skin is bad, when I’m dressed in ill fitting clothes- I have this deep discomfort. This isn’t me. This isn’t who I am. People will look at me and get the wrong idea of me. But what is the “right” idea? The fiction you tell yourself. This fiction is premised on inauthenticity. What about being altruistic? You pretend to care about justice, you display performative virtue, you attend public events that will validate this notion that you are committed to justice, to equality. You apologize for your ignorance. Why do you do this? It aligns well with the sense of moral superiority and virtue you associate with. But what is equality? Reality isn’t equal and it never will be. Some people are stronger, more intelligent, more beautiful, have a strong work ethic, are maternal and loving, are radiant. These qualities play into differential outcomes. Equality is an idea. It is an abstraction. It is an idea we associate with virtue and thus embody traits that we think are relevant to this ideal. It is a fiction. Moral superiority is a fiction.

6. We get mad when our partner flirts with someone else. When they consider someone else attractive, beautiful, whole, radiant. Why? Because their interest challenges the notion that we are special. That we are somehow deeply linked to this person. That we have security. That we are special and unique. It challenges the idea that our partner is deeply committed to us, and sees these unique traits. It is an emotion premised on insecurity. Premised on the fiction that we have security, that one person will exclusively love us. The fiction that our qualities are somehow unique. You’re not special. You cannot guarantee the loyalty of your partner. You cannot reduce the greatness of others. Nevertheless we allow ourselves to feel threatened based on the idea that your partner’s interest in others is somehow a threat to your relationship, and the fiction that their loyalty is in your power to control. So we manipulate. Through expressions of jealousy, demonization of the person your partner flirts with, amplifying the qualities you think your partner is attracted to, going out of your way to display your “amazing” qualities. You’re not special or any more valuable than anyone else.

We believe that being genetically similar somehow makes connections deeper and more stable. That intimacy and vulnerability makes your connection with a person deeper. That sharing significant experiences makes your connection deeper. It doesn’t. This sense of depth in a relationship is premised on these fictions that these dimensions of shared experience somehow tie you deeply to someone else. They can still leave. They can still cheat. But so long as you mutually subscribe to this idea that you are intimately connected, then this fiction works as glue to the relationship. It’s a fiction.

What is a romantic relationship? My conclusion is that a romantic relationship is having a personal space invader. The person is allowed to get very close physically, even put themselves inside of you, lick the inside of your mouth, spend a lot of time in your dwelling, eat food within a meter of so of each other. This person invades your space and takes up your time more than any other person. What is romance? The idea that sharing fictions and emotions leads to deep love. What is love? Feeling like the other person invading your space means that they think your special. You like this a lot. You like having a space invader because it signals that you’re not so repulsive and intolerable. That’s a nice idea. What is a long term relationship, or a marriage? It’s a promise that you’ll continue to invade a person’s space, eliminate possibilities of not invading that person’s space for a long time.

My partner and I just signed a lease for a year. All that is is a promise that the owner of this house will give us 330 square feet of space, and this 330 square feet will function as the space we will mutually invade. We have decided that we will be each others space invaders for at least a year. We buy furniture together, keep things in a closet together, so that not only the space around our bodies is invaded frequently, but that our “belongings” will have to share a space as well. It means we will promise to link our lives together in such a way that not being each other’s space invader for the year will cause a lot of friction.

What is a marriage? It’s a contract that you’ll space invade until death! And if you change your mind it will be costly in many ways. It is a fun little trap that you mutually accept. This contract is another fiction. You can’t be bound to another human, you can’t own another human, you can’t connect to another human. You connect more because we accept the premise that invading space and penetrating a person’s body is special and is a “bonding” experience. What about reading a book? You connect with these fictional people. What about being turned on by porn? You’re literally having a sexual experience with pixels on a screen. What about reading a self help book? You’re feeling vulnerable with words on a page written by someone you’ll probably never know. What about connecting with “God”, who is God? How do you know him/her? Does God invade your personal space? Or is God just a thought that you “connect” to?

We have these ideas and love to manipulate the world to keep these ideas alive. You can see delusion in others, but neglect the ways you are equally deluded. We put smoke detectors in our homes, locks on our door, wear helmets, don’t walk alone at night. But what if you get hit by a car? What is you have an aneurysm? What if you slip in the bath an hit your head and drown? We think we can reduce risks, but it’s just supporting this fiction that we can manipulate the world to give us a false sense of security. We will all die of mortality. The people we love will leave us or die. Our house might get burnt down, we might be struck by lightning. Safety is an idea. Security is an idea.

It’s all a fiction. And you lie to yourself daily to support these fictions. You manipulate others and deceive yourself into believing these fictions. You’re a snake. You’re not above self delusions and neither am I.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

During a lull one afternoon when I was a high school student selling Black Panther Party newspapers on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1971, I sat down on the curb and opened the tabloid to the 10-point program, “What We Want; What We Believe.” The graphic assertion of “Point Number 3” particularly grabbed me:

“We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules … promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of Black people. We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over fifty million Black people. Therefore, we feel this is a modest demand that we make.”

The absence of justice continually flustered me because, even at that young age, I knew that Black people had been kidnapped and brought to this country to labor for free as slaves; stripped of our language, religion, and culture; raped and tortured; and then subjected to a Jim Crow-era of lynchings, police brutality, inferior education, substandard housing, and mediocre health care. I did not know then about the massacres in Rosewood, Florida, or Tulsa, Oklahoma; the merciless experimentations on defenseless Black women devoid of anesthesia that led to modern gynecology; or about the enormous profits from slavery made by corporations, insurance companies, the banking and investment industries, and academic institutions. But on a psychic level, I could feel in my bones the enslavement era’s inhumane cruelty to Black children — its destruction of kindred ties and its economic exploitation and cultural deprivation. There was an incessant gnawing in my soul for amends and redress. I was passionate about injustice, felt the idea of reparations to be reasonable and fair, and vowed to talk about the concept whenever and wherever I could. My analysis, however, had not crystallized beyond a check. But just to mouth the word “reparations” was a starting point to its validity. Thus talk about it I did, despite my views being often rejected, ridiculed, or otherwise summarily dismissed. Standing on the street corner that afternoon nearly five decades ago, little did I realize that I would one day be in the company of leading academics, economists, historians, attorneys, psychiatrists, politicians, and more — domestically and internationally — promoting the right to, and the need for, reparations.

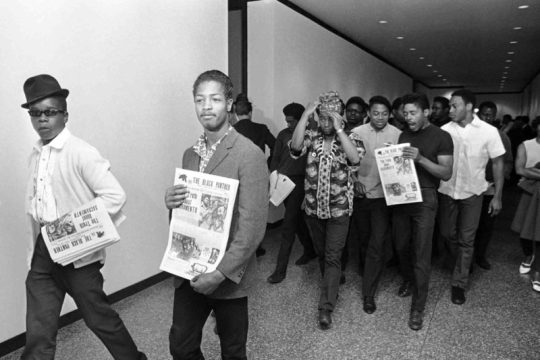

Several members of the Black Panther party carry copies of the Black Panther newspaper

Credit: Associated Press

The Fight for Reparations Has a Long History

But that day would be far into the future. Despite my advocacy and that of many others during my high school, college, and law school years and beyond, the issue of reparations for descendants of Africans enslaved in the United States was not fashionable, but fringe, and definitely not part of the mainstream popular discourse. Indeed, one would be branded as a militant or a revolutionary (both of which I was), or just plain crazy (which I was not), or in today’s dubious governmental surveillance parlance, a “Black Identity Extremist.” Indeed, it is almost surreal being amidst all the buzz surrounding reparations today, from universities to talk show pundits and, interestingly, to 2020 Democratic candidates vying for the presidency. Despite or perhaps because of today’s surge in attention to this longstanding issue, I feel it critical that the populace understands that the demand for reparations in the U.S. for unpaid labor during the enslavement era and post-slavery discrimination is not novel or new. The claim did not drop from the sky with Ta’Nehisi Coates’ brilliant treatise, “The Case for Reparations,” in The Atlantic, or from Randall Robinson’s impassioned book, “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” both of which galvanized the issue in different decades and thrust it into national conversation.

Although there have been hills and valleys in national attention to the issue, there has been no substantial period of time when the call for redress was not passionately voiced. The first formal record of a petition for reparations in the United States was pursued and won by a formerly enslaved woman, Belinda Royall. Professor Ray Winbush’s book, “Belinda’s Petition,” describes a petition she presented to the Massachusetts General Assembly in 1783, requesting a pension from the proceeds of her enslaver’s estate — an estate partly the product of her own uncompensated labor. Belinda’s petition yielded a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings. Former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Mary Frances Berry illuminated the case of Callie House in her book, “My Face Is Black Is True.” Callie, along with Rev. Isaiah Dickerson, headed the first mass reparations movement in the United States, founded in 1898. The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Bounty and Pension Association had 600,000 dues-paying members who sought to obtain compensation for slavery from federal agencies. During the 1920s, Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association galvanized hundreds of thousands of Black people seeking repatriation with reparation, proclaiming, “Hand back to us our own civilisation. Hand back to us that which you have robbed and exploited of us … for the last 500 years.” During the 1950s and 1960s, New York’s Queen Mother Audley Moore was perhaps the best-known advocate for reparations. As president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, she presented a petition against genocide and for self-determination, land, and reparations to the United Nations in both 1957 and 1959. She was active in every major reparations movement until her death in 1996.

Queen Mother Audley Moore

Credit: Associated Press

In his 1963 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” Dr. Martin Luther King proposed a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” which emphasized redress for both the historical victimization and exploitation of Blacks as well as their present-day degradation. “The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of labor on one human being by another,” he wrote. “This law should be made to apply for the American Negroes.” After the Black Panther Party’s stance in 1966, the Republic of New Afrika proclaimed in its 1968 “Declaration of Independence:

“We claim no rights from the United States of America other than those rights belonging to people anywhere in the world, and these include the right to damages, reparations, due us from the grievous injuries sustained by ourselves and our ancestors by reason of United States’ lawlessness.”

In April 1969, the “Black Manifesto” was adopted at a National Black Economic Development Conference. The manifesto, presented by civil rights activist James Forman, included a demand that white churches and synagogues pay $500 million in reparations to Blacks in the U.S. The amount was based on a calculation of $15 for each of the estimated 20 to 30 million African Americans residing in the U.S. He touted it as only the beginning of the amount owed. The following month, Forman interrupted Sunday service at Riverside Church in New York to announce the reparations demand from the “Black Manifesto.” Notably, several religious institutions did respond with financial donations. In 1972, the National Black Political Assembly Convention meeting in Gary, Indiana, adopted “The Anti-Depression Program,” an act authorizing the payment of a sum of money in reparations for slavery as well as the creation of a negotiating commission to determine kind, dates, and other details of paying reparations. Consistently, the Nation of Islam’s publications — such as Muhammad Speaks and, later, The Final Call — have demanded that the United States exempt Black people “from all taxation as long as we are deprived of equal justice.”

The Modern-Day Reparations Movement

But it was the end of the 20th century that brought broad national attention to the call for reparations for people of African descent in the United States with the founding of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (NCOBRA). I was proud to be a founding member of NCOBRA at the historic gathering on Sept. 26, 1987, which brought together diverse groups under one umbrella, from the Republic of New Afrika to the National Conference of Black Lawyers. For its first decade in existence, I served as chair of NCOBRA’s legislative commission. Since the creation of NCOBRA, the demand for reparations in the United States substantially leaped forward, generating what I’ve dubbed “The Modern-Day Reparations Movement.” Inspired by and organized on the heels of the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which granted reparations to Japanese-Americans for their unjust incarceration during World War II, NCOBRA reinvigorated the demand for reparations for African Americans and broadened the concept through public education, accompanied by legislative and litigation-based initiatives. Also encouraged by the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, Rep. John Conyers introduced a bill in 1989 to “establish a commission to examine the institution of slavery and subsequent racial and economic discrimination against African Americans and the impact of these forces on Black people today.” This commission would be charged with making recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies. The bill’s number “H.R. 40” was in remembrance of the unfulfilled 19th-century campaign promise to give freed Blacks 40 acres and a mule. Conyers’ “Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act” provided the cover and vehicle to have a public policy discussion on the issue of reparations in Congress.

Rep. John Conyers

Credit: Associated Press

The 1988 Civil Liberties Act authorized the payment of $20,000 to each Japanese-American detention-camp survivor, a trust fund to be used to educate Americans about the suffering of the Japanese-Americans, a formal apology from the U.S. government, and a pardon for all those convicted of resisting detention camp incarceration. It is a sad commentary that the U.S. government has not taken formal responsibility for its role in the enslavement or post-slavery apartheid segregation of millions of Blacks. It has never attempted reparations to African Americans for the extortion of labor for many generations, deprivation of their freedom and human rights, and terrorism against them throughout the centuries. The U.S. Senate and House did pass symbolic resolutions apologizing for slavery and segregation. However, the 2009 bill passed by the Senate contained a disclaimer that those seeking reparations or cash compensation could not use the apology to support a legal claim against the U.S. Since the introduction of H.R. 40, several state legislatures and scores of city councils across the country have passed reparations-type legislation or resolutions endorsing H.R. 40. In 1990, the Louisiana House of Representatives passed a resolution in support of reparations. In 1991, legislation was introduced in the Massachusetts Senate providing for the payment of reparations for slavery, the slave trade, and individual discrimination against the people of African descent born or residing in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 1994, the Florida Legislature paid $150,000 to each of the 11 survivors of the 1923 Rosewood Race Massacre and created a scholarship fund for students of color. In 2001, the California State Assembly passed a resolution in support of reparations. After a four-year investigation, the Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act was enacted in 2001. Oklahoma legislators settled on a scholarship fund and memorial to commemorate the June 1921 massacre that left as many as 300 Black people dead and 40 square blocks of exclusively Black businesses, homes, and schools obliterated. That same year, a bill was introduced in the New York State Assembly to create a “Commission to Quantify the Debt Owed to African Americans.” Bills are also pending within several other state legislatures, but the reparations movement isn’t just targeting state houses. City councils in the states of Arkansas, California, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have all passed resolutions in support of H.R. 40. Reparations advocates have also challenged corporations who benefited from the profits made from trafficking in human beings during the enslavement era. Countless companies and industries benefited and were enriched from the profits made as a result of chattel slavery. There are companies that sold life insurance policies on the lives of enslaved persons, such as Aetna, New York Life, and AIG. Financial gains were accrued by the predecessor banks of financial giants like J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America. Others with documented ties to slavery included railroads like Norfolk Southern, CSX, Union Pacific, and Canadian National. Newspaper publishers that assisted in the capture of runaway persons include Knight Rider, Tribune, E.W. Scripps, and Gannett. The financial backers of many of the country’s top universities were wealthy slave owners, and it has been disclosed that the reason Georgetown University stands today is because the Jesuits who ran the college used profits from the sale of Black people to continue its operation. Survivors of torture by Chicago police received an unprecedented compensatory package based on a reparations ordinance passed by the Chicago City Council in 2015. Numerous civil and human rights organizations, religious groups, professional organizations, civic groups, sororities, fraternities, and labor unions have also officially endorsed the call for reparations. In 2016, the Movement for Black Lives Policy Table released its platform, which prominently featured the issue of reparations. The role that governments, corporations, industries, religious institutions, educational institutions, private estates, and other entities played in supporting the institution of slavery and its vestiges are roles that can no longer be ignored, dismissed outright, or swept under the rug. The time is now ripe that their involvement be recognized, examined, discussed, and redressed.

The Demand Deserves Serious Consideration

I am part of the inaugural cohort of commissioners on the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC), convened by the Institute of the Black World 21st Century in 2016. The commission’s preamble asserts:

“No amount of material resources or monetary compensation can ever be sufficient restitution for the spiritual, mental, cultural and physical damages inflicted on Africans by centuries of the MAAFA, the holocaust of enslavement and the institution of chattel slavery.”

Recognizing these as “crimes against humanity,” as acknowledged by the 2001 Durban Declaration and Program of Action of the World Conference Against Racism in South Africa, the preamble goes on to assert that “the devastating damages of enslavement and systems of apartheid and de facto segregation spanned generations to negatively affect the collective well-being of Africans in America to this very moment.” NAARC has advanced a comprehensive, yet preliminary, reparations program to guide reparatory justice demands by people of African descent in the United States. Finally, although my primary focus has been on obtaining reparations for African descendants in the United States, it is critical to recognize that our quest is part of the international movement for reparations as well. As such, I have worked closely with supporters of reparations throughout the world, recognizing that the success of the movement for reparations for diasporic Africans anywhere advances the movement for reparations by Africans and African descendants everywhere. I am thrilled that my quest to have reparations seen as a legitimate concept for African Americans, begun nearly 50 years ago, is becoming a reality. The issue has become more precise, less rhetorical, and has entered the mainstream. And while cash payments remain an important and necessary component of any claim for damages, it is crystal clear today that a reparations settlement can be fashioned in as many ways as necessary to equitably address the countless manifestations of injury sustained from chattel slavery and its continuing vestiges. Some forms of redress may include land, economic development, or scholarships. Other amends may embrace community development, repatriation resources, or truthful textbooks. Still, other areas of reparatory justice may encompass the erection of monuments and museums, pardons for impacted prisoners from the COINTELPRO-era, and repairing the harms from the War on Drugs. Fifty years after I first entered the reparations movement, I’m optimistic. It’s hard not to be when H.R. 40 has been updated to include not just a mere study of proposals but also their development. It’s also hard not to be optimistic when a Senate companion bill to H.R. 40 has been introduced and even more astonishing when some Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential race are saying they will sign the legislation if elected president. Despite a resurfacing of white supremacy in the U.S., I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. I am buoyed by the reemergence of the spirits of Belinda, Callie House, and Queen Mother Moore as well as the resilience of “Reparations Ray” Jenkins, who kept the fire alive in Rep. Conyers to introduce H.R. 40 year after year. And I am inspired by the words of the great anti-slavery orator Frederick Douglass, who poignantly instructed that “power concedes nothing without a demand.” The demand has been made and the time to seriously consider reparations has finally come.

READ THE FULL REPARATIONS SERIES

Nkechi Taifa is founder and president of The Taifa Group, LLC. An accomplished human rights attorney, she is a justice system reform strategist, advocate, and scholar.

Published May 27, 2020 at 12:05AM via ACLU https://ift.tt/3grc5uE

0 notes

Photo

PREMIERE OF THE PANTHER - SALIEU as T’CHALLA Before Ta’nehisi Coates took over the writing of the Black Panther Comics reboot, before Chadwick Boseman made his first appearance as T’Challa, I took on the task of finding a top male model of color to embody Black Panther in my annual “Comics Casting” exercise for Halloween. My longtime muse Sal’s sinewy physique, attention-demanding presence and “explosive power under control” vibe made him the perfect choice. Any day is a good day to dig through the archives of TuTchTmuse Salieu Jalloh, but today seemed especially appropriate! S/O to the man who discovered Salieu & nurtured his career to the highest levels, @porgie.j at @red_models! Onward & Upwards! @BlackPanther @Marvel @Marvelstudios @salieujalloh27 #TuTchT #TuTchTIMAGING #ThruTuTchTEyes #BlackPanther #SalieuJalloh #TuTchTmuse #TuTchTComicsCasting #TopMaleModelsofColor #TuTchTModelPortraits #SuperheroSupermodels #RunwayKings #PremiereofthePanther

#salieujalloh#tutchtcomicscasting#blackpanther#tutchtmuse#tutchtimaging#tutchtmodelportraits#runwaykings#superherosupermodels#tutcht#thrututchteyes#premiereofthepanther#topmalemodelsofcolor

0 notes

Link

Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

During a lull one afternoon when I was a high school student selling Black Panther Party newspapers on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1971, I sat down on the curb and opened the tabloid to the 10-point program, “What We Want; What We Believe.” The graphic assertion of “Point Number 3” particularly grabbed me:

“We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules … promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of Black people. We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over fifty million Black people. Therefore, we feel this is a modest demand that we make.”

The absence of justice continually flustered me because, even at that young age, I knew that Black people had been kidnapped and brought to this country to labor for free as slaves; stripped of our language, religion, and culture; raped and tortured; and then subjected to a Jim Crow-era of lynchings, police brutality, inferior education, substandard housing, and mediocre health care. I did not know then about the massacres in Rosewood, Florida, or Tulsa, Oklahoma; the merciless experimentations on defenseless Black women devoid of anesthesia that led to modern gynecology; or about the enormous profits from slavery made by corporations, insurance companies, the banking and investment industries, and academic institutions. But on a psychic level, I could feel in my bones the enslavement era’s inhumane cruelty to Black children — its destruction of kindred ties and its economic exploitation and cultural deprivation. There was an incessant gnawing in my soul for amends and redress. I was passionate about injustice, felt the idea of reparations to be reasonable and fair, and vowed to talk about the concept whenever and wherever I could. My analysis, however, had not crystallized beyond a check. But just to mouth the word “reparations” was a starting point to its validity. Thus talk about it I did, despite my views being often rejected, ridiculed, or otherwise summarily dismissed. Standing on the street corner that afternoon nearly five decades ago, little did I realize that I would one day be in the company of leading academics, economists, historians, attorneys, psychiatrists, politicians, and more — domestically and internationally — promoting the right to, and the need for, reparations.

Several members of the Black Panther party carry copies of the Black Panther newspaper

Credit: Associated Press

The Fight for Reparations Has a Long History

But that day would be far into the future. Despite my advocacy and that of many others during my high school, college, and law school years and beyond, the issue of reparations for descendants of Africans enslaved in the United States was not fashionable, but fringe, and definitely not part of the mainstream popular discourse. Indeed, one would be branded as a militant or a revolutionary (both of which I was), or just plain crazy (which I was not), or in today’s dubious governmental surveillance parlance, a “Black Identity Extremist.” Indeed, it is almost surreal being amidst all the buzz surrounding reparations today, from universities to talk show pundits and, interestingly, to 2020 Democratic candidates vying for the presidency. Despite or perhaps because of today’s surge in attention to this longstanding issue, I feel it critical that the populace understands that the demand for reparations in the U.S. for unpaid labor during the enslavement era and post-slavery discrimination is not novel or new. The claim did not drop from the sky with Ta’Nehisi Coates’ brilliant treatise, “The Case for Reparations,” in The Atlantic, or from Randall Robinson’s impassioned book, “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” both of which galvanized the issue in different decades and thrust it into national conversation.

Although there have been hills and valleys in national attention to the issue, there has been no substantial period of time when the call for redress was not passionately voiced. The first formal record of a petition for reparations in the United States was pursued and won by a formerly enslaved woman, Belinda Royall. Professor Ray Winbush’s book, “Belinda’s Petition,” describes a petition she presented to the Massachusetts General Assembly in 1783, requesting a pension from the proceeds of her enslaver’s estate — an estate partly the product of her own uncompensated labor. Belinda’s petition yielded a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings. Former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Mary Frances Berry illuminated the case of Callie House in her book, “My Face Is Black Is True.” Callie, along with Rev. Isaiah Dickerson, headed the first mass reparations movement in the United States, founded in 1898. The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Bounty and Pension Association had 600,000 dues-paying members who sought to obtain compensation for slavery from federal agencies. During the 1920s, Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association galvanized hundreds of thousands of Black people seeking repatriation with reparation, proclaiming, “Hand back to us our own civilisation. Hand back to us that which you have robbed and exploited of us … for the last 500 years.” During the 1950s and 1960s, New York’s Queen Mother Audley Moore was perhaps the best-known advocate for reparations. As president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, she presented a petition against genocide and for self-determination, land, and reparations to the United Nations in both 1957 and 1959. She was active in every major reparations movement until her death in 1996.

Queen Mother Audley Moore

Credit: Associated Press

In his 1963 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” Dr. Martin Luther King proposed a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” which emphasized redress for both the historical victimization and exploitation of Blacks as well as their present-day degradation. “The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of labor on one human being by another,” he wrote. “This law should be made to apply for the American Negroes.” After the Black Panther Party’s stance in 1966, the Republic of New Afrika proclaimed in its 1968 “Declaration of Independence:

“We claim no rights from the United States of America other than those rights belonging to people anywhere in the world, and these include the right to damages, reparations, due us from the grievous injuries sustained by ourselves and our ancestors by reason of United States’ lawlessness.”

In April 1969, the “Black Manifesto” was adopted at a National Black Economic Development Conference. The manifesto, presented by civil rights activist James Forman, included a demand that white churches and synagogues pay $500 million in reparations to Blacks in the U.S. The amount was based on a calculation of $15 for each of the estimated 20 to 30 million African Americans residing in the U.S. He touted it as only the beginning of the amount owed. The following month, Forman interrupted Sunday service at Riverside Church in New York to announce the reparations demand from the “Black Manifesto.” Notably, several religious institutions did respond with financial donations. In 1972, the National Black Political Assembly Convention meeting in Gary, Indiana, adopted “The Anti-Depression Program,” an act authorizing the payment of a sum of money in reparations for slavery as well as the creation of a negotiating commission to determine kind, dates, and other details of paying reparations. Consistently, the Nation of Islam’s publications — such as Muhammad Speaks and, later, The Final Call — have demanded that the United States exempt Black people “from all taxation as long as we are deprived of equal justice.”

The Modern-Day Reparations Movement

But it was the end of the 20th century that brought broad national attention to the call for reparations for people of African descent in the United States with the founding of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (NCOBRA). I was proud to be a founding member of NCOBRA at the historic gathering on Sept. 26, 1987, which brought together diverse groups under one umbrella, from the Republic of New Afrika to the National Conference of Black Lawyers. For its first decade in existence, I served as chair of NCOBRA’s legislative commission. Since the creation of NCOBRA, the demand for reparations in the United States substantially leaped forward, generating what I’ve dubbed “The Modern-Day Reparations Movement.” Inspired by and organized on the heels of the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which granted reparations to Japanese-Americans for their unjust incarceration during World War II, NCOBRA reinvigorated the demand for reparations for African Americans and broadened the concept through public education, accompanied by legislative and litigation-based initiatives. Also encouraged by the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, Rep. John Conyers introduced a bill in 1989 to “establish a commission to examine the institution of slavery and subsequent racial and economic discrimination against African Americans and the impact of these forces on Black people today.” This commission would be charged with making recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies. The bill’s number “H.R. 40” was in remembrance of the unfulfilled 19th-century campaign promise to give freed Blacks 40 acres and a mule. Conyers’ “Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act” provided the cover and vehicle to have a public policy discussion on the issue of reparations in Congress.

Rep. John Conyers

Credit: Associated Press

The 1988 Civil Liberties Act authorized the payment of $20,000 to each Japanese-American detention-camp survivor, a trust fund to be used to educate Americans about the suffering of the Japanese-Americans, a formal apology from the U.S. government, and a pardon for all those convicted of resisting detention camp incarceration. It is a sad commentary that the U.S. government has not taken formal responsibility for its role in the enslavement or post-slavery apartheid segregation of millions of Blacks. It has never attempted reparations to African Americans for the extortion of labor for many generations, deprivation of their freedom and human rights, and terrorism against them throughout the centuries. The U.S. Senate and House did pass symbolic resolutions apologizing for slavery and segregation. However, the 2009 bill passed by the Senate contained a disclaimer that those seeking reparations or cash compensation could not use the apology to support a legal claim against the U.S. Since the introduction of H.R. 40, several state legislatures and scores of city councils across the country have passed reparations-type legislation or resolutions endorsing H.R. 40. In 1990, the Louisiana House of Representatives passed a resolution in support of reparations. In 1991, legislation was introduced in the Massachusetts Senate providing for the payment of reparations for slavery, the slave trade, and individual discrimination against the people of African descent born or residing in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 1994, the Florida Legislature paid $150,000 to each of the 11 survivors of the 1923 Rosewood Race Massacre and created a scholarship fund for students of color. In 2001, the California State Assembly passed a resolution in support of reparations. After a four-year investigation, the Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act was enacted in 2001. Oklahoma legislators settled on a scholarship fund and memorial to commemorate the June 1921 massacre that left as many as 300 Black people dead and 40 square blocks of exclusively Black businesses, homes, and schools obliterated. That same year, a bill was introduced in the New York State Assembly to create a “Commission to Quantify the Debt Owed to African Americans.” Bills are also pending within several other state legislatures, but the reparations movement isn’t just targeting state houses. City councils in the states of Arkansas, California, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have all passed resolutions in support of H.R. 40. Reparations advocates have also challenged corporations who benefited from the profits made from trafficking in human beings during the enslavement era. Countless companies and industries benefited and were enriched from the profits made as a result of chattel slavery. There are companies that sold life insurance policies on the lives of enslaved persons, such as Aetna, New York Life, and AIG. Financial gains were accrued by the predecessor banks of financial giants like J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America. Others with documented ties to slavery included railroads like Norfolk Southern, CSX, Union Pacific, and Canadian National. Newspaper publishers that assisted in the capture of runaway persons include Knight Rider, Tribune, E.W. Scripps, and Gannett. The financial backers of many of the country’s top universities were wealthy slave owners, and it has been disclosed that the reason Georgetown University stands today is because the Jesuits who ran the college used profits from the sale of Black people to continue its operation. Survivors of torture by Chicago police received an unprecedented compensatory package based on a reparations ordinance passed by the Chicago City Council in 2015. Numerous civil and human rights organizations, religious groups, professional organizations, civic groups, sororities, fraternities, and labor unions have also officially endorsed the call for reparations. In 2016, the Movement for Black Lives Policy Table released its platform, which prominently featured the issue of reparations. The role that governments, corporations, industries, religious institutions, educational institutions, private estates, and other entities played in supporting the institution of slavery and its vestiges are roles that can no longer be ignored, dismissed outright, or swept under the rug. The time is now ripe that their involvement be recognized, examined, discussed, and redressed.

The Demand Deserves Serious Consideration

I am part of the inaugural cohort of commissioners on the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC), convened by the Institute of the Black World 21st Century in 2016. The commission’s preamble asserts:

“No amount of material resources or monetary compensation can ever be sufficient restitution for the spiritual, mental, cultural and physical damages inflicted on Africans by centuries of the MAAFA, the holocaust of enslavement and the institution of chattel slavery.”

Recognizing these as “crimes against humanity,” as acknowledged by the 2001 Durban Declaration and Program of Action of the World Conference Against Racism in South Africa, the preamble goes on to assert that “the devastating damages of enslavement and systems of apartheid and de facto segregation spanned generations to negatively affect the collective well-being of Africans in America to this very moment.” NAARC has advanced a comprehensive, yet preliminary, reparations program to guide reparatory justice demands by people of African descent in the United States. Finally, although my primary focus has been on obtaining reparations for African descendants in the United States, it is critical to recognize that our quest is part of the international movement for reparations as well. As such, I have worked closely with supporters of reparations throughout the world, recognizing that the success of the movement for reparations for diasporic Africans anywhere advances the movement for reparations by Africans and African descendants everywhere. I am thrilled that my quest to have reparations seen as a legitimate concept for African Americans, begun nearly 50 years ago, is becoming a reality. The issue has become more precise, less rhetorical, and has entered the mainstream. And while cash payments remain an important and necessary component of any claim for damages, it is crystal clear today that a reparations settlement can be fashioned in as many ways as necessary to equitably address the countless manifestations of injury sustained from chattel slavery and its continuing vestiges. Some forms of redress may include land, economic development, or scholarships. Other amends may embrace community development, repatriation resources, or truthful textbooks. Still, other areas of reparatory justice may encompass the erection of monuments and museums, pardons for impacted prisoners from the COINTELPRO-era, and repairing the harms from the War on Drugs. Fifty years after I first entered the reparations movement, I’m optimistic. It’s hard not to be when H.R. 40 has been updated to include not just a mere study of proposals but also their development. It’s also hard not to be optimistic when a Senate companion bill to H.R. 40 has been introduced and even more astonishing when some Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential race are saying they will sign the legislation if elected president. Despite a resurfacing of white supremacy in the U.S., I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. I am buoyed by the reemergence of the spirits of Belinda, Callie House, and Queen Mother Moore as well as the resilience of “Reparations Ray” Jenkins, who kept the fire alive in Rep. Conyers to introduce H.R. 40 year after year. And I am inspired by the words of the great anti-slavery orator Frederick Douglass, who poignantly instructed that “power concedes nothing without a demand.” The demand has been made and the time to seriously consider reparations has finally come.

READ THE FULL REPARATIONS SERIES

Nkechi Taifa is founder and president of The Taifa Group, LLC. An accomplished human rights attorney, she is a justice system reform strategist, advocate, and scholar.

Published May 26, 2020 at 07:35PM via ACLU https://ift.tt/3grc5uE

0 notes

Text

ACLU: Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

During a lull one afternoon when I was a high school student selling Black Panther Party newspapers on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1971, I sat down on the curb and opened the tabloid to the 10-point program, “What We Want; What We Believe.” The graphic assertion of “Point Number 3” particularly grabbed me:

“We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules … promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of Black people. We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over fifty million Black people. Therefore, we feel this is a modest demand that we make.”

The absence of justice continually flustered me because, even at that young age, I knew that Black people had been kidnapped and brought to this country to labor for free as slaves; stripped of our language, religion, and culture; raped and tortured; and then subjected to a Jim Crow-era of lynchings, police brutality, inferior education, substandard housing, and mediocre health care. I did not know then about the massacres in Rosewood, Florida, or Tulsa, Oklahoma; the merciless experimentations on defenseless Black women devoid of anesthesia that led to modern gynecology; or about the enormous profits from slavery made by corporations, insurance companies, the banking and investment industries, and academic institutions. But on a psychic level, I could feel in my bones the enslavement era’s inhumane cruelty to Black children — its destruction of kindred ties and its economic exploitation and cultural deprivation. There was an incessant gnawing in my soul for amends and redress. I was passionate about injustice, felt the idea of reparations to be reasonable and fair, and vowed to talk about the concept whenever and wherever I could. My analysis, however, had not crystallized beyond a check. But just to mouth the word “reparations” was a starting point to its validity. Thus talk about it I did, despite my views being often rejected, ridiculed, or otherwise summarily dismissed. Standing on the street corner that afternoon nearly five decades ago, little did I realize that I would one day be in the company of leading academics, economists, historians, attorneys, psychiatrists, politicians, and more — domestically and internationally — promoting the right to, and the need for, reparations.

Several members of the Black Panther party carry copies of the Black Panther newspaper

Credit: Associated Press

The Fight for Reparations Has a Long History

But that day would be far into the future. Despite my advocacy and that of many others during my high school, college, and law school years and beyond, the issue of reparations for descendants of Africans enslaved in the United States was not fashionable, but fringe, and definitely not part of the mainstream popular discourse. Indeed, one would be branded as a militant or a revolutionary (both of which I was), or just plain crazy (which I was not), or in today’s dubious governmental surveillance parlance, a “Black Identity Extremist.” Indeed, it is almost surreal being amidst all the buzz surrounding reparations today, from universities to talk show pundits and, interestingly, to 2020 Democratic candidates vying for the presidency. Despite or perhaps because of today’s surge in attention to this longstanding issue, I feel it critical that the populace understands that the demand for reparations in the U.S. for unpaid labor during the enslavement era and post-slavery discrimination is not novel or new. The claim did not drop from the sky with Ta’Nehisi Coates’ brilliant treatise, “The Case for Reparations,” in The Atlantic, or from Randall Robinson’s impassioned book, “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” both of which galvanized the issue in different decades and thrust it into national conversation.

Although there have been hills and valleys in national attention to the issue, there has been no substantial period of time when the call for redress was not passionately voiced. The first formal record of a petition for reparations in the United States was pursued and won by a formerly enslaved woman, Belinda Royall. Professor Ray Winbush’s book, “Belinda’s Petition,” describes a petition she presented to the Massachusetts General Assembly in 1783, requesting a pension from the proceeds of her enslaver’s estate — an estate partly the product of her own uncompensated labor. Belinda’s petition yielded a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings. Former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Mary Frances Berry illuminated the case of Callie House in her book, “My Face Is Black Is True.” Callie, along with Rev. Isaiah Dickerson, headed the first mass reparations movement in the United States, founded in 1898. The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Bounty and Pension Association had 600,000 dues-paying members who sought to obtain compensation for slavery from federal agencies. During the 1920s, Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association galvanized hundreds of thousands of Black people seeking repatriation with reparation, proclaiming, “Hand back to us our own civilisation. Hand back to us that which you have robbed and exploited of us … for the last 500 years.” During the 1950s and 1960s, New York’s Queen Mother Audley Moore was perhaps the best-known advocate for reparations. As president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, she presented a petition against genocide and for self-determination, land, and reparations to the United Nations in both 1957 and 1959. She was active in every major reparations movement until her death in 1996.

Queen Mother Audley Moore

Credit: Associated Press

In his 1963 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” Dr. Martin Luther King proposed a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” which emphasized redress for both the historical victimization and exploitation of Blacks as well as their present-day degradation. “The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of labor on one human being by another,” he wrote. “This law should be made to apply for the American Negroes.” After the Black Panther Party’s stance in 1966, the Republic of New Afrika proclaimed in its 1968 “Declaration of Independence:

“We claim no rights from the United States of America other than those rights belonging to people anywhere in the world, and these include the right to damages, reparations, due us from the grievous injuries sustained by ourselves and our ancestors by reason of United States’ lawlessness.”

In April 1969, the “Black Manifesto” was adopted at a National Black Economic Development Conference. The manifesto, presented by civil rights activist James Forman, included a demand that white churches and synagogues pay $500 million in reparations to Blacks in the U.S. The amount was based on a calculation of $15 for each of the estimated 20 to 30 million African Americans residing in the U.S. He touted it as only the beginning of the amount owed. The following month, Forman interrupted Sunday service at Riverside Church in New York to announce the reparations demand from the “Black Manifesto.” Notably, several religious institutions did respond with financial donations. In 1972, the National Black Political Assembly Convention meeting in Gary, Indiana, adopted “The Anti-Depression Program,” an act authorizing the payment of a sum of money in reparations for slavery as well as the creation of a negotiating commission to determine kind, dates, and other details of paying reparations. Consistently, the Nation of Islam’s publications — such as Muhammad Speaks and, later, The Final Call — have demanded that the United States exempt Black people “from all taxation as long as we are deprived of equal justice.”

The Modern-Day Reparations Movement

But it was the end of the 20th century that brought broad national attention to the call for reparations for people of African descent in the United States with the founding of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (NCOBRA). I was proud to be a founding member of NCOBRA at the historic gathering on Sept. 26, 1987, which brought together diverse groups under one umbrella, from the Republic of New Afrika to the National Conference of Black Lawyers. For its first decade in existence, I served as chair of NCOBRA’s legislative commission. Since the creation of NCOBRA, the demand for reparations in the United States substantially leaped forward, generating what I’ve dubbed “The Modern-Day Reparations Movement.” Inspired by and organized on the heels of the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which granted reparations to Japanese-Americans for their unjust incarceration during World War II, NCOBRA reinvigorated the demand for reparations for African Americans and broadened the concept through public education, accompanied by legislative and litigation-based initiatives. Also encouraged by the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, Rep. John Conyers introduced a bill in 1989 to “establish a commission to examine the institution of slavery and subsequent racial and economic discrimination against African Americans and the impact of these forces on Black people today.” This commission would be charged with making recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies. The bill’s number “H.R. 40” was in remembrance of the unfulfilled 19th-century campaign promise to give freed Blacks 40 acres and a mule. Conyers’ “Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act” provided the cover and vehicle to have a public policy discussion on the issue of reparations in Congress.

Rep. John Conyers

Credit: Associated Press

The 1988 Civil Liberties Act authorized the payment of $20,000 to each Japanese-American detention-camp survivor, a trust fund to be used to educate Americans about the suffering of the Japanese-Americans, a formal apology from the U.S. government, and a pardon for all those convicted of resisting detention camp incarceration. It is a sad commentary that the U.S. government has not taken formal responsibility for its role in the enslavement or post-slavery apartheid segregation of millions of Blacks. It has never attempted reparations to African Americans for the extortion of labor for many generations, deprivation of their freedom and human rights, and terrorism against them throughout the centuries. The U.S. Senate and House did pass symbolic resolutions apologizing for slavery and segregation. However, the 2009 bill passed by the Senate contained a disclaimer that those seeking reparations or cash compensation could not use the apology to support a legal claim against the U.S. Since the introduction of H.R. 40, several state legislatures and scores of city councils across the country have passed reparations-type legislation or resolutions endorsing H.R. 40. In 1990, the Louisiana House of Representatives passed a resolution in support of reparations. In 1991, legislation was introduced in the Massachusetts Senate providing for the payment of reparations for slavery, the slave trade, and individual discrimination against the people of African descent born or residing in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 1994, the Florida Legislature paid $150,000 to each of the 11 survivors of the 1923 Rosewood Race Massacre and created a scholarship fund for students of color. In 2001, the California State Assembly passed a resolution in support of reparations. After a four-year investigation, the Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act was enacted in 2001. Oklahoma legislators settled on a scholarship fund and memorial to commemorate the June 1921 massacre that left as many as 300 Black people dead and 40 square blocks of exclusively Black businesses, homes, and schools obliterated. That same year, a bill was introduced in the New York State Assembly to create a “Commission to Quantify the Debt Owed to African Americans.” Bills are also pending within several other state legislatures, but the reparations movement isn’t just targeting state houses. City councils in the states of Arkansas, California, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have all passed resolutions in support of H.R. 40. Reparations advocates have also challenged corporations who benefited from the profits made from trafficking in human beings during the enslavement era. Countless companies and industries benefited and were enriched from the profits made as a result of chattel slavery. There are companies that sold life insurance policies on the lives of enslaved persons, such as Aetna, New York Life, and AIG. Financial gains were accrued by the predecessor banks of financial giants like J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America. Others with documented ties to slavery included railroads like Norfolk Southern, CSX, Union Pacific, and Canadian National. Newspaper publishers that assisted in the capture of runaway persons include Knight Rider, Tribune, E.W. Scripps, and Gannett. The financial backers of many of the country’s top universities were wealthy slave owners, and it has been disclosed that the reason Georgetown University stands today is because the Jesuits who ran the college used profits from the sale of Black people to continue its operation. Survivors of torture by Chicago police received an unprecedented compensatory package based on a reparations ordinance passed by the Chicago City Council in 2015. Numerous civil and human rights organizations, religious groups, professional organizations, civic groups, sororities, fraternities, and labor unions have also officially endorsed the call for reparations. In 2016, the Movement for Black Lives Policy Table released its platform, which prominently featured the issue of reparations. The role that governments, corporations, industries, religious institutions, educational institutions, private estates, and other entities played in supporting the institution of slavery and its vestiges are roles that can no longer be ignored, dismissed outright, or swept under the rug. The time is now ripe that their involvement be recognized, examined, discussed, and redressed.

The Demand Deserves Serious Consideration

I am part of the inaugural cohort of commissioners on the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC), convened by the Institute of the Black World 21st Century in 2016. The commission’s preamble asserts:

“No amount of material resources or monetary compensation can ever be sufficient restitution for the spiritual, mental, cultural and physical damages inflicted on Africans by centuries of the MAAFA, the holocaust of enslavement and the institution of chattel slavery.”

Recognizing these as “crimes against humanity,” as acknowledged by the 2001 Durban Declaration and Program of Action of the World Conference Against Racism in South Africa, the preamble goes on to assert that “the devastating damages of enslavement and systems of apartheid and de facto segregation spanned generations to negatively affect the collective well-being of Africans in America to this very moment.” NAARC has advanced a comprehensive, yet preliminary, reparations program to guide reparatory justice demands by people of African descent in the United States. Finally, although my primary focus has been on obtaining reparations for African descendants in the United States, it is critical to recognize that our quest is part of the international movement for reparations as well. As such, I have worked closely with supporters of reparations throughout the world, recognizing that the success of the movement for reparations for diasporic Africans anywhere advances the movement for reparations by Africans and African descendants everywhere. I am thrilled that my quest to have reparations seen as a legitimate concept for African Americans, begun nearly 50 years ago, is becoming a reality. The issue has become more precise, less rhetorical, and has entered the mainstream. And while cash payments remain an important and necessary component of any claim for damages, it is crystal clear today that a reparations settlement can be fashioned in as many ways as necessary to equitably address the countless manifestations of injury sustained from chattel slavery and its continuing vestiges. Some forms of redress may include land, economic development, or scholarships. Other amends may embrace community development, repatriation resources, or truthful textbooks. Still, other areas of reparatory justice may encompass the erection of monuments and museums, pardons for impacted prisoners from the COINTELPRO-era, and repairing the harms from the War on Drugs. Fifty years after I first entered the reparations movement, I’m optimistic. It’s hard not to be when H.R. 40 has been updated to include not just a mere study of proposals but also their development. It’s also hard not to be optimistic when a Senate companion bill to H.R. 40 has been introduced and even more astonishing when some Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential race are saying they will sign the legislation if elected president. Despite a resurfacing of white supremacy in the U.S., I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. I am buoyed by the reemergence of the spirits of Belinda, Callie House, and Queen Mother Moore as well as the resilience of “Reparations Ray” Jenkins, who kept the fire alive in Rep. Conyers to introduce H.R. 40 year after year. And I am inspired by the words of the great anti-slavery orator Frederick Douglass, who poignantly instructed that “power concedes nothing without a demand.” The demand has been made and the time to seriously consider reparations has finally come.

READ THE FULL REPARATIONS SERIES

Nkechi Taifa is founder and president of The Taifa Group, LLC. An accomplished human rights attorney, she is a justice system reform strategist, advocate, and scholar.

Published May 27, 2020 at 12:05AM via ACLU https://ift.tt/3grc5uE from Blogger https://ift.tt/3dhutnT via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

ACLU: Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

During a lull one afternoon when I was a high school student selling Black Panther Party newspapers on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1971, I sat down on the curb and opened the tabloid to the 10-point program, “What We Want; What We Believe.” The graphic assertion of “Point Number 3” particularly grabbed me:

“We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules … promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of Black people. We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over fifty million Black people. Therefore, we feel this is a modest demand that we make.”

The absence of justice continually flustered me because, even at that young age, I knew that Black people had been kidnapped and brought to this country to labor for free as slaves; stripped of our language, religion, and culture; raped and tortured; and then subjected to a Jim Crow-era of lynchings, police brutality, inferior education, substandard housing, and mediocre health care. I did not know then about the massacres in Rosewood, Florida, or Tulsa, Oklahoma; the merciless experimentations on defenseless Black women devoid of anesthesia that led to modern gynecology; or about the enormous profits from slavery made by corporations, insurance companies, the banking and investment industries, and academic institutions. But on a psychic level, I could feel in my bones the enslavement era’s inhumane cruelty to Black children — its destruction of kindred ties and its economic exploitation and cultural deprivation. There was an incessant gnawing in my soul for amends and redress. I was passionate about injustice, felt the idea of reparations to be reasonable and fair, and vowed to talk about the concept whenever and wherever I could. My analysis, however, had not crystallized beyond a check. But just to mouth the word “reparations” was a starting point to its validity. Thus talk about it I did, despite my views being often rejected, ridiculed, or otherwise summarily dismissed. Standing on the street corner that afternoon nearly five decades ago, little did I realize that I would one day be in the company of leading academics, economists, historians, attorneys, psychiatrists, politicians, and more — domestically and internationally — promoting the right to, and the need for, reparations.

Several members of the Black Panther party carry copies of the Black Panther newspaper

Credit: Associated Press

The Fight for Reparations Has a Long History

But that day would be far into the future. Despite my advocacy and that of many others during my high school, college, and law school years and beyond, the issue of reparations for descendants of Africans enslaved in the United States was not fashionable, but fringe, and definitely not part of the mainstream popular discourse. Indeed, one would be branded as a militant or a revolutionary (both of which I was), or just plain crazy (which I was not), or in today’s dubious governmental surveillance parlance, a “Black Identity Extremist.” Indeed, it is almost surreal being amidst all the buzz surrounding reparations today, from universities to talk show pundits and, interestingly, to 2020 Democratic candidates vying for the presidency. Despite or perhaps because of today’s surge in attention to this longstanding issue, I feel it critical that the populace understands that the demand for reparations in the U.S. for unpaid labor during the enslavement era and post-slavery discrimination is not novel or new. The claim did not drop from the sky with Ta’Nehisi Coates’ brilliant treatise, “The Case for Reparations,” in The Atlantic, or from Randall Robinson’s impassioned book, “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” both of which galvanized the issue in different decades and thrust it into national conversation.

Although there have been hills and valleys in national attention to the issue, there has been no substantial period of time when the call for redress was not passionately voiced. The first formal record of a petition for reparations in the United States was pursued and won by a formerly enslaved woman, Belinda Royall. Professor Ray Winbush’s book, “Belinda’s Petition,” describes a petition she presented to the Massachusetts General Assembly in 1783, requesting a pension from the proceeds of her enslaver’s estate — an estate partly the product of her own uncompensated labor. Belinda’s petition yielded a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings. Former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Mary Frances Berry illuminated the case of Callie House in her book, “My Face Is Black Is True.” Callie, along with Rev. Isaiah Dickerson, headed the first mass reparations movement in the United States, founded in 1898. The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Bounty and Pension Association had 600,000 dues-paying members who sought to obtain compensation for slavery from federal agencies. During the 1920s, Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association galvanized hundreds of thousands of Black people seeking repatriation with reparation, proclaiming, “Hand back to us our own civilisation. Hand back to us that which you have robbed and exploited of us … for the last 500 years.” During the 1950s and 1960s, New York’s Queen Mother Audley Moore was perhaps the best-known advocate for reparations. As president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, she presented a petition against genocide and for self-determination, land, and reparations to the United Nations in both 1957 and 1959. She was active in every major reparations movement until her death in 1996.

Queen Mother Audley Moore

Credit: Associated Press

In his 1963 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” Dr. Martin Luther King proposed a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” which emphasized redress for both the historical victimization and exploitation of Blacks as well as their present-day degradation. “The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of labor on one human being by another,” he wrote. “This law should be made to apply for the American Negroes.” After the Black Panther Party’s stance in 1966, the Republic of New Afrika proclaimed in its 1968 “Declaration of Independence:

“We claim no rights from the United States of America other than those rights belonging to people anywhere in the world, and these include the right to damages, reparations, due us from the grievous injuries sustained by ourselves and our ancestors by reason of United States’ lawlessness.”

In April 1969, the “Black Manifesto” was adopted at a National Black Economic Development Conference. The manifesto, presented by civil rights activist James Forman, included a demand that white churches and synagogues pay $500 million in reparations to Blacks in the U.S. The amount was based on a calculation of $15 for each of the estimated 20 to 30 million African Americans residing in the U.S. He touted it as only the beginning of the amount owed. The following month, Forman interrupted Sunday service at Riverside Church in New York to announce the reparations demand from the “Black Manifesto.” Notably, several religious institutions did respond with financial donations. In 1972, the National Black Political Assembly Convention meeting in Gary, Indiana, adopted “The Anti-Depression Program,” an act authorizing the payment of a sum of money in reparations for slavery as well as the creation of a negotiating commission to determine kind, dates, and other details of paying reparations. Consistently, the Nation of Islam’s publications — such as Muhammad Speaks and, later, The Final Call — have demanded that the United States exempt Black people “from all taxation as long as we are deprived of equal justice.”

The Modern-Day Reparations Movement

But it was the end of the 20th century that brought broad national attention to the call for reparations for people of African descent in the United States with the founding of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (NCOBRA). I was proud to be a founding member of NCOBRA at the historic gathering on Sept. 26, 1987, which brought together diverse groups under one umbrella, from the Republic of New Afrika to the National Conference of Black Lawyers. For its first decade in existence, I served as chair of NCOBRA’s legislative commission. Since the creation of NCOBRA, the demand for reparations in the United States substantially leaped forward, generating what I’ve dubbed “The Modern-Day Reparations Movement.” Inspired by and organized on the heels of the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which granted reparations to Japanese-Americans for their unjust incarceration during World War II, NCOBRA reinvigorated the demand for reparations for African Americans and broadened the concept through public education, accompanied by legislative and litigation-based initiatives. Also encouraged by the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, Rep. John Conyers introduced a bill in 1989 to “establish a commission to examine the institution of slavery and subsequent racial and economic discrimination against African Americans and the impact of these forces on Black people today.” This commission would be charged with making recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies. The bill’s number “H.R. 40” was in remembrance of the unfulfilled 19th-century campaign promise to give freed Blacks 40 acres and a mule. Conyers’ “Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act” provided the cover and vehicle to have a public policy discussion on the issue of reparations in Congress.

Rep. John Conyers

Credit: Associated Press