#story of oppression told with an allegory my beloved

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Maybe I’m slow on the draw and everyone connected these dots already, or maybe I’ve just realized how important Jim’s arc is to Aziraphale’s decision at the end of season two.

Not only does Aziraphale meet a completely new, kind person in Gabriel without his memories, but when he finally regains them, he doesn’t revert to his cold self. Gabriel is a reformed person, finally having formed his own opinions outside of the strict guise of Heaven.

And Aziraphale finally realizes that even the worst of the angels have the ability to change.

The happy couple being allowed to disappear and live their eternity together is the proof he needs to believe the others may be swayed as well.

And the Metatron’s timing in all of this is horrifically perfect, catching Zira in a vulnerability that has just formed, and pulling him right back into the cycle of abuse.

#good omens#good omens season two#gos2#gos2 spoilers#good omens spoilers#as much as the coffee theory is nice for coping I genuinely believe zira made this decision#and though it’s not a good decision… all signs in this season and it’s flashbacks point to his religious trauma not at all being resolved#and I’m so so hoping for it to be a big focus in season three#it’s the perfect opportunity to explore the queer themes already in the narrative with trauma that so often afflicts queer people#just not in the manner of homophobia like in real life. it’s more a parallel through this universe’s lends#honestly the complete lack of homophobia is so delightful and allows every character to face deeper conflicts within the self#story of oppression told with an allegory my beloved#(as long as it’s on purpose and us fans don’t have to trip over ourselves to make it a queer narrative of course)#(there’s so much I could cough at and call out with that but you get the idea lol)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review

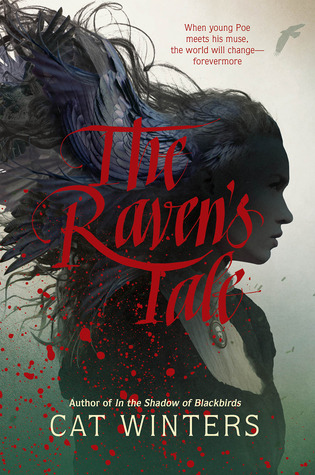

The Raven’s Tale. By Cat Winters. New York: Amulet Books, 2019.

Rating: 2.5/5 stars

Genre: YA historical fiction, supernatural

Part of a Series? No.

Summary: Seventeen-year-old Edgar Poe counts down the days until he can escape his foster family—the wealthy Allans of Richmond, Virginia. He hungers for his upcoming life as a student at the prestigious new university, almost as much as he longs to marry his beloved Elmira Royster. However, on the brink of his departure, all his plans go awry when a macabre Muse named Lenore appears to him. Muses are frightful creatures that lead Artists down a path of ruin and disgrace, and no respectable person could possibly understand or accept them. But Lenore steps out of the shadows with one request: “Let them see me!”

***Full review under the cut.***

Content Warnings: verbal/emotional/financial abuse, morbid thoughts

Overview: In the author’s note at the back of this book, Winters states that she tried to “offer reader’s a window into Poe’s teenage years” and “root the book in [Poe’s] reality while also immersing the story in scenes of Gothic fantasy that paid homage to his legendary macabre works.” Regarding the first bit, I don’t think the concept is itself a bad one - writing about the early life of a major cultural figure is a great way to get a YA audience (who may be teenagers themselves) to connect with them. Regarding the second bit, I don’t think this story came across as “Gothic” so much as it was more “magical realism.” I wouldn’t call this story “macabre” in any way, nor do I think Winters used any elements that were evocative of Gothic fantasy in the literary sense. Even if we abandon the idea that The Raven’s Tale is supposed to be “Gothic,” I do think Winters could have used the concepts she established to a greater effect than she did, such as using Poe’s muses more allegorically to talk about things that matter to modern-day readers (like the value of art, how darkness can be comforting and can help process emotions, etc). But as it stands, this book mostly reads like Poe stumbling around, trying to find his feet as the poetic genius that he’s destined to be - something I don’t think is as interesting.

Writing: Winters alternates between using her own prose style and mimicking Poe’s sense of meter and rhyme. In some cases, she does very well. I was impressed by the way she was able to use her vocabulary to mimic what she thought Poe’s young voice might sound like, and the intertextuality within this book shows how she was cognizant of Poe’s education and background.

I do think, however, that Winters misused repetition. There are some moments when a phrase, sentence, or group of sentences are repeated, perhaps in the attempt to create emphasis on a concept, but to me, they felt tedious. I can’t tell how many times we’re told that Poe is a swimmer, and in one scene, artistic inspiration is portrayed as the same phrases being repeated two or three times until the words are written down.

I also don’t think that, despite the rich vocabulary, Winters makes use of language to create evocative settings or convey emotion well. No matter how many turns of phrases I read, I didn’t quite connect with the characters or feel invested in their well-being.

Finally, I found the genre of this book to be a little strange, given the author’s intention to infuse the story with tributes to “Gothic fantasy.” In my opinion, the tone wasn’t sufficiently gloomy enough to warrant the book as a whole being characterized as “Gothic” or “dark fantasy,” nor were the defining characteristics of Gothic literature present. At most, you could say there was a tyrannical antagonist and some dark imagery, but I don’t think the atmosphere was pushed into the realm of Gothic or even horror. Rather, I think the story is more rooted in magical realism in that we get magical elements in a real-world setting without much explanation as to how or why muses are able to take physical form and everyone accepts that. I don’t think that magical realism is a bad choice or inferior genre, just that Winters’ intention doesn’t quite match up with her results.

Plot: The plot of this book follows a young Edgar Allan Poe as he leaves home to go to college, enduring abuse from his adoptive father as well as financial trouble. Along the way, he comes face-to-face with Lenore, his “dark muse,” who urges him to shrug off his foster father’s influence and embrace his destiny as a writer. I think the potential for something interesting was there - student loan debt is definitely something many young people grapple with, so in some ways, Poe could have been made more relatable to modern readers. I don’t think, however, that the plot itself as it stands was very engaging, primarily because the focus was entirely on cultivating Poe’s “literary genius.” If the story wasn’t talking about whether Poe should write macabre tales or satires, it was focused on Lenore’s desire to “be seen” and “evolve.” Artistic genius is something very few people possess, and the righteous struggle of embracing art no matter the real-world consequences doesn’t quite acknowledge how those real-world consequences have a real effect on a person’s well-being. True, this book does mention that Poe struggles financially and resorts to drinking and gambling and taking out enormous loans to cover his debts, but they felt like afterthoughts in that not much time is given to exploring them compared to Poe’s literary journey. I would have liked to see Poe’s story brought down to a level that more people could connect to, such as using Lenore as a sounding board for exploring more complex ideas like the value of art, how art is used to rebel against oppressive power structures, the cost of following one’s dreams in a world that doesn’t value them, or how darkness and morbid imagery can be a source of comfort (rather than wholly an indicator that something is wrong with someone).

Characters: This book is told in first person, alternating between Poe’s perspective and Lenore’s. Poe is supposedly a teenager obsessed with death yet afraid of dying, yet that defining characteristic comes up so few times that it’s easily forgettable. Poe is also a little hot-and-cold towards his muse, Lenore, sometimes caring for her and desiring her presence, other times pushing her away out of shame. I think the struggle to overcome internal shame could have been interesting if more was done to explore the concept, but as the book stands, it doesn’t seem like young Poe does much except react to the whims of his muses and lament his financial and family situations.

Lenore, Poe’s “Gothic muse,” is a strange figure in that’s she’s a concept made flesh. Representing Poe’s macabre side, she follows Poe around, demanding that she “be seen” so she can evolve into her final form, a dark-winged raven. As much as I liked having half the book narrated by a female character, I don’t think her perspective enhanced the story much. Her perspective demystified Lenore in ways that I think undercut the book’s intended mood, and even the scenes in which she delivers poetic inspiration aren’t very gripping or fantastical.

Poe does have a second muse named Garland O’Peale, who represents Poe’s satirical and witty side. The real Poe was a master literary critic in addition to horror-smith and poet, and it was great to see this part of the literary giant’s career explored in some capacity. Garland is frequently in conflict with Lenore, claiming that focusing on dark imagery and the macabre is “childish.” I think there was some potential here for a deeper dive into why certain literary genres are valued more than others, as well as a more complex rendering of Poe’s mental characteristics being externalized and turned into an allegory. However, because not much is done with this allegory, both Garland and Lenore read a little flat.

Supporting characters are likewise a little underdeveloped. I didn’t get the sense that Poe truly connected with any of his friends and classmates, and I didn’t see why he loved Elmira (other than he tells us so). His adoptive father is sufficiently evil for the purposes of this story, but again, John Allan’s obsession with snuffing out Poe’s literary impulses in favor of turning him towards “real work” could have been taken up as a central theme of the book and made more complex.

Recommendations: I would recommend this book if you’re interested in the life and work of Edgar Allan Poe, 19th century America, dark or Gothic literature, the concept of artistic inspiration, and magical realism.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Power of Nonviolence” based on Isaiah 5:1-7 and Matthew 21:33-40

As my paternal grandmother (Nana) aged, she needed increasing levels of help. After she'd transitioned to assisted living, her beloved only son (my father) would often take her out on shopping excursions. My Nana was a woman who loved to shop, ok, she was a woman who lived to shop. It regularly amused me to talk to both my father and my Nana after said excursions. My Nana would relate the experiences this way, “Your father is SO impatient! All I wanted to do was go to a few stores, look at what they had, and enjoy being out. All he wanted was to get out of there. It is like he doesn't know how to have any fun!” My father would relate the experiences this way, “Your grandmother takes forever! I took her to the store, she wanted me to push her down each of the the aisles, slowly, and then when we were done she'd want to do it again!”

Their two versions of shopping together always made me giggle because it was so clear that they were relating the same story, just from two different experiences. I've been thinking about their shopping excursions this week because the Gospel does the opposite.

As far as I can figure it out, what we have in the Gospel is one story being used for two totally different purposes at the same time (without changing perspectives). One of these stories is the narrative that Jesus told and the other is the one that the early Christian community told, and they told them for VERY different reasons.

Since we are are much more familiar with the one the early Christian community told, and since it is the version we see in the Gospel today, we're going to start by looking at that one. It is brilliantly done, poetically beautiful, and intended to insult the Jews. SIGH. As the Jesus Seminar puts it, “This parable was a favorite in early Christian circles because it could easily be allegorized [to the story where] God's favor was transferred from its original recipients (Israel) to its new heirs (Christians, principally gentiles).”1 This version intentionally reflections on Isaiah 5:1-7. They start in parallel ways, with the description of the creation of the vineyard: planting, enclosing, digging, building a watch tower. The parallels in the beginning of the passages are intended to remind us of the conclusion of the Isaiah reading, which says (in case you forgot), “[God] expected justice, but saw bloodshed; righteousness, but heard a cry!” (Isaiah 5:7b, NRSV)

In Isaiah the shock is that after all that work (and it takes years to get grapes from the vineyard), the grapes were sour. The metaphor indicates that God had invested in creating a just society with Israel and is horrified that they didn't become one. Matthew extends this metaphor, indicating that he thinks the Jews failed to create a just society, but that the Christians will succeed. In the allegorical reading of the parable, God will kick out the tenants and replace them. It seems that this reflects a time when Christians were feeling disempowered and felt the need to tell stories that empowered them. The problem is that for a whole lot of centuries now, Christians have been the empowered and by continuing to tell themselves this story they have disempowered Jewish people and perpetuated antisemitism.

We can be clear that the Matthew version is the creation of the Christian community and not Jesus because it includes the detail about the son being killed and cast off. Ched Myers writes, “The son is killed and cast off (without proper burial, the ultimate insult) Jesus too will be cast 'outside' the city of Jerusalem.”2

The good news is that scholars think they can get a good guess at how the original parable sounded, the one Jesus told. This is the other version of the parable, and it wasn't allegorical. William Herzog points out the version in Matthew is quite different from others, saying, “The parable begins with a description of a man creating a vineyard yet neither Luke nor the Gospel of Thomas include these details.”3 That means that the original parable wasn't meant to be an extension of Isaiah 5, and likely wasn't intending to dismiss the Jews. The Gospel of Thomas version is thought to be the closest to what Jesus might actually have said:

“He said, A [. . .] person owned a vineyard and rented it to some farmers, so they could work it and he could collect its crop from them. He sent his slave so the farmers would give him the vineyard's crop. They grabbed him, beat him, and almost killed him, and the slave returned and told his master. His master said, "Perhaps he didn't know them." He sent another slave, and the farmers beat that one as well. Then the master sent his son and said, "Perhaps they'll show my son some respect." Because the farmers knew that he was the heir to the vineyard, they grabbed him and killed him.”4

This parable seems to describe something that might have actually happened during Jesus life time. It reflects tensions that were present in Galilee at that time. In the Social Science Commentary they write, “If we may assume that at the earliest stage of the Gospel tradition the story was not an allegory about God's dealings with Israel, as it is now, it may well have been a warning to absentee landowners expropriating and exporting the produce of the land.”5 Another commentator concludes, “And however the vengeance of the owner may be interpreted allegorically, it certainly reflects a landowner's wrath, which which the landless Palestinian was all too familiar.”6

So the problem in the parable according to Herzog is “the creation of a vineyard would, on economic grounds alone, have disturbed the hearers of the parable. Because land in Galilee was largely accounted for and intensively cultivated, 'a man' could acquire the land required to build a vineyard only by taking it from someone else. The most likely way he would have added the land to his holdings was through foreclosure on loans to free peasant farmers who were unable to pay off the loans because of poor harvests.”7 This means that “building vineyards was a 'speculative investment' and therefore the prerogative of the rich.”8 So the parable reflects economic realities that were doing GREAT harm in Galilee at the time of Jesus.

It also reflected a reality of violence at the time of Jesus. Herzog continues, “If the peasants resorted to violence only when their subsistence itself was threatened then the conversion of land from farmland to a vineyard ([Mark] 12:1b, 2) would be an event that would trigger such a response. The building of the vineyard and the violence it generates also describes the conflict of two value systems. Elites continually sought to expand their holdings and add to their wealth at the expense of the peasants.”9 So, the creation of new vineyards was part of a system of wealth transformation from the subsistence peasants to the very wealthy. Herzog then seems this as step one in a spiral of violence that went like this:

“The spiral begins in the everyday oppression and exploitation of the poor by the ruling class.This violence is often covert and sanctioned by law, such as the hostile takeover of peasant land. More often than not, peasants simply adjust and adapt to these incursions by the elites in order to maintain their subsistence standard; but... even peasants have a breaking point. When their very subsistence is threatened, they will revolt. This is the second phrase of the spiral of violence, and it is this phase that the parable depicts in great detail. Inevitably, such rebellions or revolts are repressed through the use of force, as the final question of the parable suggests. This officially sanctioned violence defines the final phase of the spiral of violence, which always occurs 'under the pretext of safeguarding public order [or] national security.”10

I have, to this point, been following the commentaries of multiple brilliant scholars: ones who differentiated the current form of the parable from the one Jesus likely told, ones that explain the economic factors of vineyards, ones that connect economic systems with violence. However, first I'm going to draw my own conclusion, one that none of them came around to.

To get there, I want to go back to a seemingly simple point John Dominic Crossan made while he was here. He mentioned that Jesus was killed for being a non-violent revolutionary, and we know this because he was killed alone instead of being killed with all of his followers like he would have been if he'd led a violent revolt. John Dominic Crossan is one of many scholars who think that Jesus was very intentionally nonviolent, and that was a definitional characteristic of his movement. I agree with them.

My suspicion is that if Jesus told this story, he told it to talk about violent resistance and nonviolent resistance. He would have told this story to point out that violence tends to beget violence, and to offer an alternative. The spiral of violence: taking away people's livelihoods, killing in self-defense, repressed rebellions was NOT the vision Jesus had for the people. By naming how things tend to go down in the world, by talking about how others were choosing to act, he would have been differentiating his movement from theirs.

The answer to Matthew's question at the end of the parable, “Now when the owner of the vineyard comes, what will he do to those tenants?” is that the owner would either kill them directly or displace them without any resources to allow them to die slowly. In the allegorical version of the story when God becomes the landowner, that's disgusting. However, if Jesus' intention was to point out how the world works and offer an alternative, it is worth listening to.

This week, it seems worth remembering that we are followers of a man who lived in a time of violence, who choose nonviolence and invited others to choose nonviolence with him. John Dominic Crossan invited us to remember that there is power in nonviolence too, and that is a power of the followers of Christ. The empire that perpetuated violence in the of Jesus killed only him because they thought the threat of violence would kill his movement, but it failed. Nonviolent resistance could not be stopped so easily.

The question for today is how we practice nonviolent resistance in the ways that Jesus did: which were pointed, powerful, and effective in caring for the vulnerable people of God. This week has felt overwhelming: paying attention to yet another mass murder, learning more and more about the ways that the people of Puerto Rico have been systematically impoverished, and watching as another large swath of people prepare for yet another hurricane. Nonviolent resistance takes intentionality, focus, communication, collaboration, creativity, and commitment. But it has brought justice to this world time and time again. (If you need an example, the Civil Rights Movement in this country is the most accessible, but the list is really quite long). The next successful movements for justice will be wise to follow the same method that Jesus used: nonviolent resistance. For that I hope we can all say: Thanks be to God. Amen

1 Robert W. Funk, Roy W Hoover, and The Jesus Seminar, The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus (HarperOneUSA, 1993), pages 510.

2 Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man ( Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1988, 2008), page 309.

3 William R. Herzog II, Parables as Subversive Speech, (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1994), p. 101.

4Gospel of Thomas 65:1-7, Scholars Version.

5 Bruce J. Malina and Richard L. Rohrbaugh, Social Science Commentary on the Synoptic Gospels (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003), p. 110.

6 Myers, 309.

7 Herzog, 102.

8 Herzog, 103.

9 Herzog, 107-108.

10 Herzog, 108-109, working with work from Helder Camara, 1971.

Rev. Sara E. Baron

First United Methodist Church of Schenectady

603 State St. Schenectady, NY 12305

Pronouns: she/her/hers

http://fumcschenectady.org/

https://www.facebook.com/FUMCSchenectady

October 8, 2018

#Thinking Church#progressive christianity#FUMC Schenectady#UMC#Schenectady#Albany District#Rev Sara E. Baron#parables of Jesus#Thanks commentators#Thanks Jesus Seminar#John Dominic Crossan#Nonviolence#Nonviolent resistance#Resist

0 notes