#stokenewingtonliteraryfestival

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

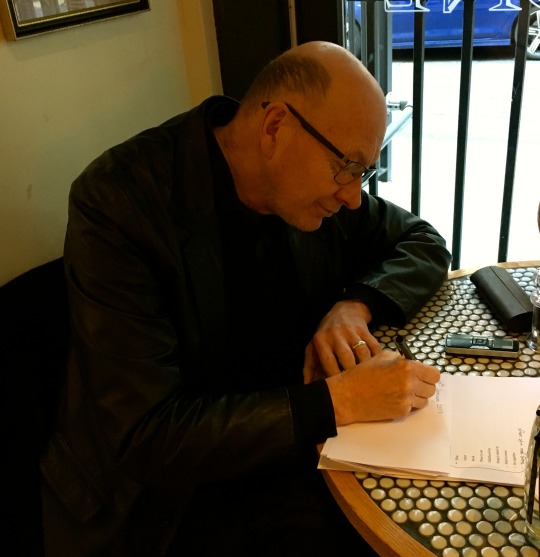

15 minutes with Richard Boon, inventor of indie, manager of Buzzcocks and production manager at Rough Trade

I wear a tie to meet Richard Boon. Firstly, he always wore ties in the punk/indie era, and, secondly, because, I’m not worthy. This person, who is so enormously significant in the history of punk, indie and Rough Trade, never shouts about his contribution. You might see him every now and then in a documentary, or rarely on a panel, but these days he prefers to work happily and quietly in Stoke Newington, as a librarian.

Mr Boon is a sharp-dresser from his Crombie coat right down to his quirky white socks, and he talks in a very considered, knowledgeable and professor-like fashion, with lots… of… important… pauses. He reminds me of a lecturer, someone who is used to being listened to; one who is steeped in literature. In fact, it’s only his one black earring that nods to a clue from his past: that a younger radical, riotous pioneer lives inside him, one that speeded through punk with the Buzzcocks, exploded the world of indie music, shaped a career at Rough Trade, and, most goldenly, made Smiths records.

For him, a real involvement in music all started after the second Sex Pistols gig in Manchester, 1976, where groups of artistic individuals hung around town wondering what to do next. Some of them were at university, some on the dole, some still at school; but all were drawn to doing something in music because of what they had just witnessed. In amongst the different ‘factions’ were Howard Trafford, Linder Sterling, Steven Morrissey and Richard Boon.

Impelled by the rush of the Sex Pistols, Mr Boon’s immediate next step was to book them for his own student union bar at Reading, where they played to a small student crowd. His equally impassioned pal, Howard, formed Buzzcocks and changed his name to Devoto. They made an EP Spiral Scratch. Frustrated that the music industry was dominated by large corporates, DIY-Richard came up with his own independent label, New Hormones, fell into the role of band manager, found a way to custom press the EP through the back door of Polydor, and took orders from record shops on his home phone. Spiral Scratch was born, as the first, self released record in history, and thus, Richard Boon invented indie.

A few years later, in the early eighties, Steven Morrissey approached him to ask what he could do with his songs. Richard explained that as his label was on its last legs, Morrissey should approach Rough Trade distribution. Shortly afterwards, Richard joined the Rough Trade label team as production manager, and worked with The Smiths throughout their entire career.

He is an accomplished chef and would prepare a red pepper soup starter if Morrissey came for dinner (plus ‘pud’). He is most animated and smiley when he talks about his family, especially his wife, Deborah, of thirty years, to whom, I’d say, he owes everything.

J: Please say your full name.

R: I don’t use the first name. Hello I’m Richard Boon! Richard is the middle name. My first name is James.

J: Why don’t you use ‘James’?

R: Because I never have. Ever since I was a very small child. My father was called James and after christening me my mum thought, ‘there’s going to be some confusion ahead’, so I’ve always been Richard. Sometimes shortened, but not by me to Rich. Rick!

J: Do people call you ‘Boon’ or ‘Boonie’?

R: When I was little I used to get called, ‘Boonie’.

J: Can you describe yourself in a sentence?

R: Hmm. I didn’t come to counseling… this has just thrown me.

J: Morrissey described you in Autobiography as a ‘whirlpool of words’.

R: I did read that, yes. Lovely. Some people describe me as the person that started independent music, some people describe me as the world’s coolest librarian. Do you want to know how much I weigh and how tall I am?

J: Yes of course! Who gave you the name ‘the world’s coolest librarian’?

R: The Stoke Newington Literary Festival. With whom I’m deeply involved and have an annual event called Juke Box Fury for music writers to talk about the tune that they allege inspired them to write and then the panel decide if it’s hit or miss. It’s just a joke, and I badly channel David Jacobs, as if you didn’t know, you were there, on my panel!

J: Yes, it was brilliant. Except for that one scary woman in the audience who got a bit angry.

R: Ah. She has an argumentative history over decades with one of your co-panellists, but we won’t go there.

J: Growing up, what music were you interested in?

R: My brother and I used to pool our pocket money for Beatles EP’s. It was better value than the single. He was seven or eight years older than I was and he started buying albums. The first album he bought was Reach Out by The Four Tops, which is a peerless record. It’s just got everything you want and it’s beautifully sequenced. Apart from the title track! Brilliant record. My father played piano and then he bought a stereo and we just used to listen to the reel-to-reel tape recorder and tape Pick of the Pops. With Fluff - Alan Freeman. Music has always been around me. My brother used to buy Melody Maker and I was buying The NME. There were only two record stores: Boots and downstairs at Valances white goods shop.

J: Where did you grow up?

R: I grew up in Leeds. I went to Leeds Grammar School and it was a direct grant so that I could get in. Like a scholarship bursary kind of thing so even poor kids can get in. When I was a teenager I used to hang out with Howard Trafford, my friend, who became Devoto, and we we’d go to the gigs in Leeds Town Hall together. There wasn’t much happening so we just started talking to a bass player called Dave and a clarinet player called Charlie. We used to meet up and try to write songs together and tape them. After this I went to Reading University.

J: When did you move to Manchester?

R: After graduation at Reading in 1976, a lot of my art school cohort went to London, but I went to Manchester to help Howard and Peter, who were determined to make a band.

J: Do you remember much about the music scene Manchester before The Smiths got started?

R: In Manchester at that time there was a really small and rebellious group of people, like a village within a village or a city within a city… Hamlet! Everybody knew one another but there were factions. People got involved from the consequences of the Pistols playing the Lesser Free Trade Hall. People were doing fanzines too. There was a loose connected identity. When it came to Morrissey everybody knew he was going to be something. He was waiting in the wings for his moment.

J: How did you first meet Morrissey?

R: I knew him from that crowd. We were all kind of a gang in the town but we wanted more bands to start up and get a sense of community going. We used to hang out in the Virgin store and read Melody Maker and read adverts like ‘I’m Rick and I’m looking for a drummer’. This was in 1976. John Maher spotted that Rick ad and I, and possibly Pete Shelley, went to the Portland Hotel with Rick, is it ‘Elby’? who brought his friend, Steven. That’s when we first met. He was very shy and retiring.

J: What was he wearing, what did he look like?

R: He hadn’t got… let’s just say you could call him ‘Steven’ then. He hadn’t got his look together.

J: You mentioned there that, ‘Everybody knew that he was going to be something.’ How could you tell?

R: Generally, he was just so engaging and witty. As things began to develop in Manchester he was always kind of around and paying attention to what was going on and wanting to get involved. He sent me a cassette which is just ‘Steven singing’. It was ‘Reel Around The Fountain’ and a version of a Bessie Smith song called ‘Wake Up Johnny’. On the tape he said, ‘It’s a very quiet recording because my mum is in the next room!’ He had even written two books when he was on the dole. He was a quiet figure waiting to become a big figure.

J: Do you still have the tape?

R: Well I may have but I don’t know where it is! The house is full of stuff! Another one lost in history! I’ve got boxes in the cellar. It might be in there. As if I could ever find it!

J: How old were you then?

R: I was twenty-three and Morrissey was eighteen. For a long period we were friends. We began as a casual connection and then we became acquaintances and then friends. Through all that after-effect of The Sex Pistols playing Manchester and Buzzcocks playing there was this whole group of people who would meet. It was through that group that Morrissey met Linder. We were all at the second Sex Pistols gig. It was after that people started to talk to one another about what to do next.

J: How did you become Buzzcocks manager?

R: I lived in a shared house with Howard Devoto. We had a landline! I just fell into booking a rehearsal space, hustling for gigs, hiring the van to get to the gig and it just turned into Buzzcocks management, although these days I prefer ‘mis-management.’

J: Tell me about Spiral Scratch.

After the Pistols’ Anarchy tour - where as far as we were concerned punk kind of stopped and became a cliché/cartoon - Howard was thinking about going back to college. We wanted to document a moment, and this moment became Buzzcocks Spiral Scratch and it was just a thing to do. We borrowed money from friends and family just to make it happen. An early form of Kickstarter without the advantages. Anyway that became a completely separate thing somehow. Howard wanted to leave, Pete wanted to continue. We hustled for more gigs and bits of music business. A&R interest started to come along, especially after The Clash’s White Riot tour. John Maher was only sixteen - just left school - and I had to check it all with his dad, who’d ask me, ‘Is there going to be any money in this for him?’

J: Is that how your record label, New Hormones happened?

R: Yes, in a way. There was no real infrastructure for independent labels then. Rough Trade began some distribution which became The Cartel, but the independent label support just wasn’t there, we had to develop it. We wanted to support people around us too, hence Linder’s design of the ‘Orgasm Addict’ cover. Then she started dabbling with music. She’s another person who was doing something but didn’t know what it was going to work out as, a bit of music, a bit of performance art, collages. Young people were trying to explore a direction by 1977.

J: Why the name, ‘New Hormones’?

R: I think it was Howard that chose it. There was a discovery around that time in 1976 of a ‘new hormone’ – I can’t remember it’s name, something scientific. It just sounded, like, yeah! Pretty cool.

J: How did you just decide, right, let’s press records on this label? How did you go about it?

R: We wanted a souvenir of what we had done during 1976. It was just research. I found that pressing plants had spare capacity and would take small amounts to keep the presses running. Polydor had a little department that did custom pressing, so having found that out, they recommended a sleeve printer and it all just worked. Records always seem to be magical things. They appeared in an occult fashion in the racks. It is actually interesting to think about, ‘How did they get there?’

With Spiral Scratch it was mail order with an address and a phone number. Jon Webster at Virgin Records in Lever Street took some. Record store managers had autonomy then. It wasn’t just central buying. Then he told his mates in the other stores, ‘Try a box of twenty five and see what happens!’ And then it happened. The phone started ringing. And generously, all the press reviews gave the address. And the phone number leaked out. It was the phone number of mine and Howard’s house!

Geoff Travis had just recently started the Rough Trade shop and he was like, ‘I’ll take fifty.’ Two days later it was, ‘Can I have two hundred more?’ It just ‘spiraled’ out control! It stimulated and inspired other people to make their own records. Desperate Bicycles formed just to make a record. ‘Spiral Scratch’ had recording information on it. Desperate Bicycles moved that on a bit further. New Hormones was demystifying something that seemed mysterious.

J: Did you ever want to be in the band?

R: No I just wanted to help. I was signing on. They formed the band.

J: Where does the name come from?

R: The name comes from our mythical lost weekend with The Sex Pistols. We picked up a copy of Time Out then which had a review about a girl group and the headline for the feature was, ‘IT’S THE BUZZ, COCKS!’ about a TV series, ‘Rock Follies, about a girl band featuring Julie Covington. It all goes back to that.

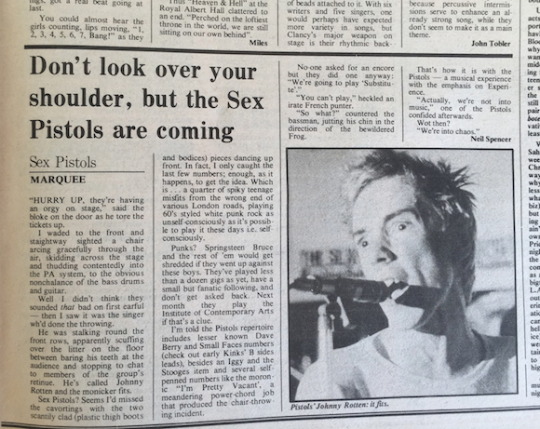

J: What happened on the lost weekend?

R: We’d read Neil Spencer’s NME review of the Pistols at The Marquee and were equally enthused and intrigued. Pete hired a car from Bolton student’s union. Howard and Peter McNeish (later Shelley) and I went off in February 1976, to ‘Sex’ to find Malcolm McLaren, who told us the Pistols were playing that weekend at High Wycombe and Welwyn Garden City. Howard, Peter and I got in the car and we drove straight to the venue. The Sex Pistols were really intrigued that we had come so far. They were opening for Screaming Lord Sutch on one of the nights.

Pete Shelley is great on this memory – he has a Rolodex in his head. It was a student audience. All we did that weekend was gig on the Friday, back to Reading to stay, then back for the Pistols Saturday night, then back home, buzzing with ideas. The weekend wasn’t lost, it was found.

J: Do you remember much about the gigs?

R: The Sex Pistols were ramshackle. It was Johnny, he was extraordinary. He didn’t give a toss about anything. He was obviously speeding. It was hot clothes, fast drugs. Johnny seemed to hate the audience. He was provocative and he dismissed us. But that didn’t matter. The first night a bunch of lads sat just under the stage making ‘Rubbish!’ gestures to their pals at the back. Johnny ran along and tousled their hair! They ran forward, picked him up and threw him on the floor. Neil Stephenson who was their loosely termed road manager joined in… and the band kept playing in the background. It was like a cartoon scrum in Tom and Jerry. Eventually Johnny crawled out from underneath and scrambled back on stage. He went:

‘WELL! THAT WAS NO FUN!’

…which was the tune they were playing. I’ve never seen anything like it. It was shocking, extraordinary, exciting.

J: Have you seen anything like it since?

R: Anything with that power? Patti Smith at Manchester Apollo doing James Brown’s ‘It’s a Man’s Man’s World.’ She nailed it! She came right to the front of the stage and that closeness and immediacy, that strength. She had a knock out moment. Whatever year it was. She actually did fall off the stage somewhere and hurt her neck. In my experience it’s rare to see that magic moment. Gifted performers.

J: Did you book the Sex Pistols for Reading Uni?

R: Yes, it was part of me being an ‘art student’! Did mainly black and white ‘things’. I had a very sympathetic tutor and once I’d seen the Sex Pistols I was determined to get them to play. The art department had a little club subsidised by the student union and I persuaded them, ‘We have to get this band!’ There was an annual event called Art Exchange. I wanted this band – they were really cheap!

[I find this ticket online and ask Richard about it: ‘I think this is fake - we just took money on the door - and it wasn’t in the Students Union; rather in a painting studio in the Art Department; there was no ‘ROCK DISCO’ – as if! Support was a performance artist, one of The Kipper Kids’].

I did all the flyering and stuff and of course as happened then, only about twenty people came. My tutor was very sympathetic when it came to my finals and included the gig booking and promotion as work I’d done. I graduated with a 2:1. Tutor Tom said, ‘The external examiners will want more evidence of drawing ability.’ I got an A1 piece of paper and pencil and just drew vertical lines as close together as I could, for about eight hours. He said, ‘I think that’s enough drawing ability!’ I was just doing black and white things, I wasn’t really doing drawings, as such.

J: Did you hang out with the band?

R: I remember having to get them out of the bar just to go on stage. Johnny liked Red Stripe. He was my favourite Sex Pistol. It went: Johnny, Glen, Paul, Steve. Malcolm was always difficult. But we didn’t really talk to them. Malcolm McLaren dominated the conversation. He’d be giving out his manifesto, like he had this tape loop, over and over again. The band didn’t really socialise much.

On the Anarchy Tour in Manchester we went to Tommy Ducks which was a legendary pub. It had ladies underwear across the ceiling and Johnny tried to pull it down. That week Johnny, Joe Strummer and Pete Shelley had all gone blonde. They were stood at the bar talking about hair products. ‘What colour did you use?’

J: Did you ever see the Pistols with Sid?

R: I saw them twice with Sid. They had become the caricature of themselves that the media set them up to become. Really. It wasn’t fun and it didn’t have the magic.

J: How did you come to work at Rough Trade?

R: Two things happened within weeks of each other. My label, New Hormones was rapidly failing. It never had any money. I had got some records out by a group called Dislocation Dance. I couldn’t do any more. They had some new tracks that I sent to Geoff Travis. I used to send promo cassettes and biogs to Pete Walmsley who did licencing. I had put out a single called ‘Rosemary’ which got picked up in Europe.

Geoff didn’t get back to me for a month and a half and then he said, ‘oh I like this can you arrange a meeting? Then, possibly just a bit later, Morrissey, Johnny and Joe Moss pitched up in my office with a tape of ‘Hand In Glove’ and ‘Handsome Devil’, which I loved! They were like, ‘Can you do anything?’ and I said, ‘Well I can’t do anything. What do you want to do?’ and they said, ‘Well we just want to put it out. Maybe we’ll do it ourselves.’ I said, ‘If you want to do it yourselves, I’ll put you in touch with Simon Edwards, who is in Rough Trade Distribution if that’s what you want to do.’ Versions of this story vary, but I phoned Simon and put him onto Joe Moss. I set up the meeting. Johnny went. They stayed at Matt Johnson’s. Anyway that’s the famous story: Simon took the tape and said, ‘No, this is worth more than a DIY release. Geoff needs to hear it.’

Geoff was always in meetings. Rough Trade was famous for meetings. Everybody was in a meeting. Later there was a meeting room but in Bleinheim Crescent you just couldn’t get hold of people. ‘Just say I’m in a meeting!’ There were an awful lot of meetings. Johnny just came around and waited until Geoff came out of his meetings and said, ‘Simon says you’ve got to hear this NOW!’ and he made an impact. Rough Trade said it would do a one-off single on the label and Scott Piering would do the promotion. Peel and Kid Jensen sessions were happening almost every other week, as a result. Mike Hinc was the booking agent and started getting them gigs and then bigger gigs.

I went down with Dislocation Dance and had a meeting with Geoff, and I said, ‘Why did it take you a month and a half to hear about this?’ and he was like, ‘I’m just so busy! I can’t keep up with stuff! Actually I think I’m going to America for two months and I might need someone here. Would you cover?’ So I thought, yes, because everything I’m doing in Manchester has run out of steam and my wife and I were getting tired of a commuting relationship because she was in London already at the BBC. The stars were in the right place. Geoff ended up not going to America.

Rough Trade had a wonderful, endless, financial crisis. I moved into the Production Manager job. It was a very hectic summer in 1983, given the amount of interest in The Smiths which just bounced: more gigs, more records, more media. Everybody at the label side was like, ‘Let’s do more! Build a relationship long term!’

This was the principle of all the early indies: 4AD, Rough Trade, Mute, Factory, they all used to have principles. To have a hit act to subsidise what they wanted to do. Daniel Miller of Mute had Depeche Mode, Factory had Joy Division and Ivo had the Cocteau Twins. Rough Trade had tried to do that with Scritti Politti, but it cost an awful lot and there were a lot of resources put into trying make Green a popstar. The money was all sloshing around A Joy Division album would have paid the debts for a Depeche Mode album.

It kind of worked, but for Rough Trade Scritti didn’t deliver in the same way as the other label-groups had, and Rough Trade was looking for someone to build on. As soon as ‘This Charming Man’ came out it was a given, it was going to be The Smiths.

J: What was the production manager’s job, day to day, at Rough Trade?

R: Get the tapes to the mastering room. Get the white labels. Make sure everybody’s happy. Commission designers. Get the sleeve proofs. Make sure everybody’s happy. Start phoning people up. See how many thousands are needed. A lot of Rough Trade’s business was only a couple of thousand. Then get the sleeves printed. Try to manage all the ingredients. Juggle. If you get a sleeve proof and that colour isn’t working… artists had a lot of control over the look and design.

Morrissey was always great. He would send photocopies of images he wanted and eventually we gave him a Pantone colour book and he could say ‘I want background pantone 132…’ Morrissey always knew what he wanted. He had a great sense of palette. Usually his things were fairly manageable. Things got complicated after Hatful of Hollow! As the Smiths built, it got ridiculous. ‘I want a hundred and fifty thousand gatefold sleeves, by last week!’

Actually, There was one problem with the inner sleeve to Hatful of Hollow. It had been mastered, the artwork was done, the lyrics were in order, it had all been done. I had already started printing the inner bags and Morrissey phoned and said, ‘Change the running order.’ Ha ha! I was like, ‘Stop printing those!’ But 30,000 had been printed already. He was like, ‘No. I want them in the right order.’ We had 30,000 inner bags to deal with. Rough Trade Germany’s production was behind ours so they got 30,000 inner sleeves with the lyrics in the wrong order! Collectors items! I don’t know which way round it had been before the current listing. But that was an awkward moment and generally, personally, Morrissey and I didn’t have awkward moments.

J: You seemed to do a lot of jobs. Were you working for the label side or the distribution side?

R: I worked for the label, initially. I started at Rough Trade in 1983 when it was in one of its regularly-occurring financial crisis. Everyone was like, ‘We can’t go on like this! We need an admin!’ So we found, probably through the Cricket Team, ‘The White Swans’ – not a Rough Trade cricket team, just people who worked at Rough Trade who were members of a cricket team - this guy Richard Powell who had turned around a Watchmakers in Clerkenwell. There was a series of meetings with him and he tidied up the mess. I’m sure the accounts department did their best but there were no clear lines of demarcation. It became this incredible structure where the wholesale department had a board that would meet about their issues. Then someone on the distribution board, then someone on the record company board, then the main board, they had meetings and the money just became a trough.

If the phone rang at Rough Trade we had two answers, ‘I’ll just find them’, or, ‘They’re in a meeting.’ Take a message! There was finally a switchboard but the receptionist would eternally say, ‘So and so is on the phone’ and we’d shout ‘I’m in a meeting!’

Then I moved to Rough Trade Distribution. Distribution had been publishing a magazine called ‘The Catalogue’ which was a funny mix of trade and consumer content. It was losing money. Editor Brenda Kelly and Pete O’Fowler were setting up a production company Snub TV. Brenda was getting ready to leave and I was asked to take over the Catalogue and ‘turn it around’. So I switched from working for the label to working for distribution. Then I turned it round by offering consumer incentives like flexidiscs! I must find a copy of the magazine! We had longer features – a lead feature every month and if you were on the cover there was the interview. It made us put in more consumer focused content other than trade news or new releases. Nick Kent reviewed ‘Rank’. I’ll see if I have that. He loved The Smiths. There was a track from Rank, it was a flexi disc, with Morrissey writing on the back. I can get you one of those if you haven’t got it. If I can find them I’ve got a box, perhaps, somewhere.

J: That would be amazing, thank you. What was Geoff’s involvement?

R: He’d probably listen to a test pressing. He wasn’t interested in the artwork - I was - I enjoyed that aspect. When we found Caryn Gough - through Malcolm Garrett - who had a studio and did graphics, we had someone who could look at Morrissey’s doodles and photocopies and turn them into what he wanted. Caryn was slightly rockabilly. She had the jeans and the chain. Caryn and Morrissey just hit it off. It was a joy to witness. Talking on the same wavelength. Caryn and Morrissey were good because he thought well, if I send this picture and the pantone number to her then she does it, and he’d say, ‘That’s just what I want!’

J: So at the label, The Smiths became the priority?

R: Yes, around the label The Smiths became the priority. Loads of attention was focused on it. The Raincoats had an album to deliver, but they kind of got slightly overlooked. They were a great band. It was a great year for music, 1983. Until The Smiths stabilised the whole operation, money was leaking everywhere in Rough Trade. There was no fiscal control. It was slack.

This was also just before we were moving out of Blenheim Crescent to Collier Street in Kings Cross. There was a huge amount to do and there was only a couple of narrow corridors. All the corridors were just filling with boxes and boxes and boxes of records of the debut album. Just before the move, all those corridors were empty! Now there was a warehouse storage space that was full of boxes and boxes.

J: Tell me about the band at that time.

R: Johnny and Morrissey were really driven and had a clear sense of purpose. They knew exactly what they wanted. They shared a vision. It was those two that pushed it forward. The other two were the rhythm section, nice as they were. For Johnny and Morrissey it really wasn’t about work. It was their passion. For the rhythm section it was work. They referred to it as work. I felt that Andy and Mike were slightly overwhelmed when The Smiths took off. It was very fast. They weren’t ready for it in the way that Johnny and Morrissey were. This was like their dream come true. No-one was really ready for it but Morrissey and Johnny had dreamt of it for a really long time.

We didn’t get any arguments from the band. Morrissey and Johnny could be awkward, deliberately so, sometimes. Johnny was overloaded and Morrissey was beautifully whimsical and could change his mind. But everybody was younger. Some of it is really about age.

I wish they had made more videos. I don’t know why they didn’t. The Derek Jarman work fitted a sort of camp sensibility with a slight radical edge, that worked well.

J: It was an exciting time to be a Smiths fan when those Jarman films came out.

R: A pretty boy on London Bridge!

J: I liked the hand in ‘Panic’.

R: It was all Super 8. It was shown all over the place. In arthouses, on TV. I don’t know why it took that long for them to make videos. Those were brilliant!

J: Did you go to a lot of gigs?

R: Yes. I went to a lot of Smiths gigs. When they did ‘This Charming Man’ on Top Of The Pops the crew that Morrissey liked were all there. Me, Geoff, Scott Piering, Martha Defoe. We were all there saying ‘Yes! Yes!’ That was a magic moment. It was incredible. We were in the wings, off camera where we could watch. It was really exciting. We just watched them soar!

I always enjoyed the band in smaller venues. I do remember London Palladium. It was one of Morrissey’s greatest desires to do the London Palladium. They brought on Pete Burns for the encore. It was exciting to see bands that you’re involved in move forward from an audience of twenty people to having an audience of two hundred to having an audience of two thousand. I’m going to use that word I hate – it’s the ‘journey’. Ha ha!

J: Tell me your recollection of the ‘I Don’t Owe You Anything’ moment at the Hacienda.

R: We all went up to the Hacienda because it was on my birthday – July the sixth. Don’t forget to send me a card! It was very nice that Morrissey acknowledged my birthday. The Rough Trade workforce was there – and some old Manchester people. It felt like a homecoming gig. It was a very different night from when The Hacienda had only twenty people in it. It was my thirtieth birthday. Then he went into ‘I Don’t Owe You Anything’, which, was kind of cheeky, I thought. It was playful. I liked it. I was like everybody’s favourite neighbour, that’s what Morrissey said.

J: I get the impression that you and Morrissey had a good rapport.

R: Yes, we had a good rapport. I could banter with him and James Maker. It was just banter, and a bit of polari! James wore beads and high heels. Johnny wore beads too. I think it was the influence of sixties girl groups. It was subversive. It was never any surprise to me that Morrissey became the front man of probably the most subversive group of the time.

J: Have you read Autobiography?

R: I’ve read Morrissey’s book, yes. I really enjoyed the stories of his upbringing - very evocative. I came out of it very well! Me and Morrissey both did, ha ha!

The only bit I read of Johnny’s was in my local bookshop and he had written something inaccurate about somebody else – and it was me! It was the bit about The Smiths tape with Matt Johnson. But it was me!

J: Do you follow Morrissey’s solo work?

R: Yes. The last time I saw him was at the Albert Hall for You Are The Quarry with my daughter. We were in a box with Boz Boorer’s family. Linder was there in the next box. We went backstage. Morrissey went up to Rachel, my daughter and said, ‘You’re supposed to be a baby!’ It was Rachel’s first big concert. We got smuggled in. Listed by Mike Hinc. I haven’t seen Johnny for a really long time.

J: What is it about The Smiths that makes them so enduring?

R: It’s the songs, really. They stand the test of time. I saw Buzzcocks at the Roundhouse two weeks ago and that was kids of all ages - including their grandparents. It all goes back to the songs. What I always find funny about Morrissey is that football terrace mob; how he excited Millwall fans. Holding banners that they love him. It goes back to the songs.

J: If Morrissey walked in here right now and said, ‘All right, Richard?’ what would you say?

R: Oh. That’s wicked. I’d say, ‘All right, Morrissey?’ Or maybe I would call him ‘Steven’. I called him that before he was Morrissey. Steven. I might say,

‘This isn’t the Morrissey that I used to know.’ Ha ha! I’d also possibly give him a man hug and say ‘It’s about time you made another record.’ Hang on, I’m not sure about the hugging thing.

J: You weren’t big huggers in the eighties?

R: No. I’ve never hugged Morrissey. I need a badge that says that. Wait - maybe it should be, ‘Morrissey never hugged me.’

J: There’s still time.

R: Oh, stop it!

J: If Morrissey was coming to your house, what snacks would you put out for him?

R: In the name of God! Right. Avocado dip. Or hummus.

J: Do you make that avocado dip yourself?

R: Yes. Quite often. Everybody gets this question?

J: Yes.

R: Okay. Dips. Starters. That’s just nibbles you see. Dips. Followed by… Now you’re really asking what I like cooking. Roasted red pepper soup. Main: I’ve recently been doing a lot of stuff with celeriac, so something around celeriac, but I’m not sure what. And then… I suppose you want pud, don’t you?

J: If you’re giving it.

R: Honestly! Oh I think, an ice cream. You want flavour? Ridiculous! For Christmas every year I make Christmas pudding ice cream. Basically vanilla ice cream with pudding in it. Why are you looking like that? I don’t let the pudding sit for a year I make it the year before. It’s frozen! Ice cream is frozen, Julie. There’s always Christmas pudding left isn’t there? Everybody likes Christmas pudding. I like Christmas pudding. Do you?

J: Oh no, I really don’t. Too stodgy. Tell me about your one earring.

R: My earring? Ha ha! I have other studs. I like this black one. I got my ear pierced in 1978. It was probably at Lewis’s in Manchester because they did ear piercing. I think it was my wife’s suggestion. Why only one? Because of William Shakespeare!

J: So it has nothing to do with punk? You never put a safety pin in it or anything like that?

R: No.

J: What did you dress like back in the Rough Trade days?

R: I had jackets. Ties. I liked ties. I always made a point when I worked at Rough Trade amidst all the punks, hippies and goths to wear a tie. It was my gag. But my earring - nobody ever asks me about that.

J: I noticed as it’s the only one. Like, ‘I’m a librarian by day but I’m secretly very punk, you know.’

R: Yes, maybe! I think I just wore a sleeper for a long time. I get most of my stuff from Metal Crumble.

J: What’s your favourite crisp flavour?

R: Salt and Vinegar. If I were to eat crisps I’d probably eat them straight from the bag.

J: What’s your favourite pizza topping?

R: Wow. Right. Topping. Let’s see. You’ve got your tomato base. Olives. Rocket. Maybe some mozzarella.

J: Favourite Buzzcocks song?

R: Ah. ‘What Do You know?’ The one with the horn section. Tail end of Buzzcocks career.

J: Favourite Sex Pistols song?

R: ‘Bodies’. Johnny’s Catholicism comes out. It’s an anti-abortion song. As Simon Reynolds’ says, it’s his favourite because Johnny says ‘F*ck’ a lot. I think because we were so familiar with the Pistols’ repertoire the only thing that was new and distinctly different was ‘Bodies’ so it stood out. Although I disagree with its sentiment.

J: What’s your favourite Smiths song?

R: Wow. Ah. That’s hard. There’s so many. Oh blimey. It’s really hard. ‘Handsome Devil.’ I love it. And I love ‘I Know It’s Over.’ But I still love ‘Handsome Devil’ it’s them as they’re really starting out. It’s got an edge, they got more polished. I like a rough diamond.

J: What’s your favourite Smiths album?

R: Strangeways.

J: The most polished.

R: The most overlooked! The Queen Is Dead is seen as their peak. Otherwise, Hatful Of Hollow. At the Peel sessions they were live and more immediate. Which is yours?

J: The Smiths. The first album. I love all the records but this is what first turned my head so it’s special to me.

R: That reminds me. Geoff and I went to a Peel session and they did ‘This Charming Man’. We ran out into the corridor and said, ‘That song! That has to be the single.’ The first time we heard it. Live. We were in the control room and had to nip out of the studio to talk about it. For Rough Trade, ‘Hand In Glove’ was a one-off deal. We never went in for standard contracts, but we decided to with The Smiths. During that summer we got into contracted discussions. We said, ‘If they’re going to sign, this has to be the single.’

J: Favourite Morrissey song?

R: ‘Every Day Is Like Sunday.’ It’ encapsulates boredom in a more serious way than Buzzcocks did. And Vini’s playing is great.

J: Favourite Morrissey album?

R: ‘Your Arsenal’. I like that one. I like the cover.

J: Do you have a lyric that you love?

R: ‘There’s more to life that books you know, but not much more.’ That’s a great line!

J: How did you end up as a librarian?

R: After the big Rough Trade collapse in 1991 a couple of people and I tried to revive The Catalogue. And failed. We tried and we failed. Then my son was born and I was ‘house husband’. In a parent-run cooperative crèche. Then my son went to primary school and my wife said, ‘Right. Get a job. Here’s an advert you should reply to!’

J: So you got your ear pierced because of your wife, and a job, because of your wife.

R: I moved to London because of my wife. She is my everything.

J: I see that! What’s your favourite thing that she says?

R: ‘Do some f*cking tidying up! Clear some of these books! Get rid of that! Why is this in the living room?’

J: Of course. She’s still with you.

R: Yes. We are blessed. We got married when she was pregnant with our daughter, Rachel, who was twenty-eight yesterday.

J: Who is your favourite actor?

R: Marlon Brando. On The Waterfront.

J: What’s your favourite book?

R: Book? That’s a big ask.

J: Favourite song to dance to?

R: Anything ska or northern soul. I like that one, oh, what’s it called, ‘Give Me Just A Little More Time’ by Chairmen of the Board. Kylie covered it. I love that. See it’s easy to dance. It’s just like this, [stands up, begins walking through the steps]. ‘One-two-three-four. One-two-three-four. Just repeat.’

J: What’s your favourite childhood toy?

R: Toy? Tough call. Mainly, I recall happy hours playing and building on my own as a small boy with Lego bricks, decades before they became so themed.

J: Where is your favourite place to eat?

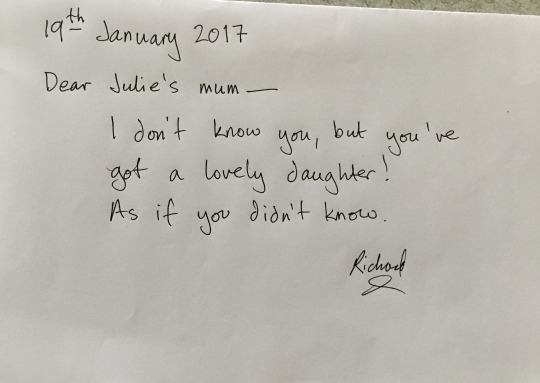

R: Place to eat? I can do place to eat. Home! I’ve done note to mum – tick.

J: Thank you. Do people phone you to check facts from years ago?

R: Yes. And some of the time I can remember them.

Follow Richard Boon on Twitter @booniepops. Don’t phone, he’s in a meeting.

15 Minutes With You by Julie Hamill is available now from all good book shops.

©All content is copyright Julie Hamill 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without consent from Juie Hamill is strictly prohibited.

Punk loose on Oxford Street

#richardboon#thesmiths#roughtrade#Morrissey#buzzcocks#sexpistols#readinguni#manchester#1976#pete shelley#magazine#howard devoto#autobiography#stokenewingtonlibrary#stokenewingtonliteraryfestival#thischarmingman#thecartel#factory records#punk#indie

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Good weekend in Stokey this weekend :) @stokenewingtonliteraryfestival — view on Instagram https://ift.tt/2xGrxAI

0 notes

Photo

Dope chat on "Music, Masculinity & Millennials" at this weekend's @stokenewingtonliteraryfestival @unseenflirtations @mostlylitpod http://ift.tt/2rvpYyP

0 notes