#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bertram “Bertie” Wooster, writing stories about Jeeves: My man is a genius. The most brilliant chap I’ve ever known. I would probably die without him. We have our little spats, and he’s got a rummy sort of schadenfreude in the soul, if that is the word I want, but my life with him is so pleasant that it’s all worthwhile. I am also passionately in love with him

James “Corky” Corcoran, writing stories about Ukridge: My best friend is literally the most annoying person alive. Can’t stand his dumb ass. Every problem I have ever had in my life is his fault. There is no interaction I come out of with Ukridge in which my wallet, my belongings, and my pride are intact. It is usually all three. I am also passionately in love with him

#red randomness#jeeves and wooster#ukridge#bertie wooster#reginald jeeves#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#james corky corcoran#jooster#wooves#corkridge#truly the duality of wode#I love how different his two longest-running narrators are#corky is so judgemental that I don’t know if he and Bertie would get along#but it would be really funny if they were friends#Bertie DOES habitually befriend a lot of artists and writers#and Corky’s snarky internal monologue does not seem to prevent him from caring for those he snarks about#Jeeves on the other hand would hate Ukridge with the fire of a thousand suns#someday I’ll write a crossover maybe

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

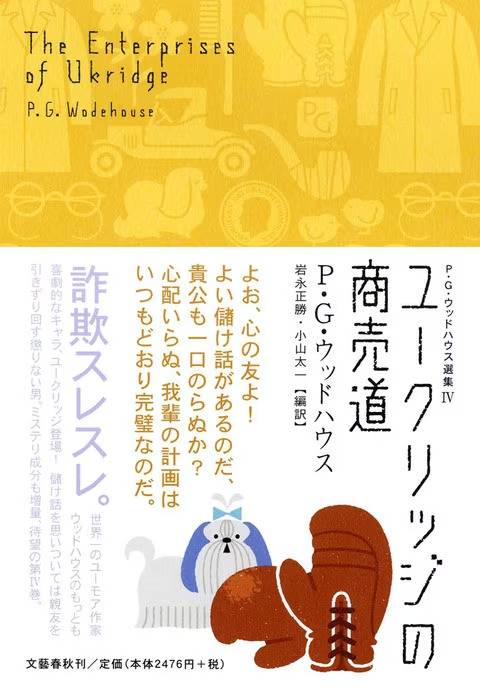

so I'm thinking about buying the Japanese translation of Ukridge, because the art is super cute and it looks like a lot of fun.

attempt at a literal translation of what Ukridge says on the intro page there (by "literal" I mean "without Edwardianing it up to match the vibes of the original"): “Yo, my bosom buddy! I’ve got a nice moneymaking scheme for ya - won’t you take a bite? You don’t have to worry about a thing - my plan is perfect, like always."

Fun notes about this:

よお (yoo) has the exact same meaning and connotation as "yo" does in English. This is very important to me.

The kanji for "bosom buddy" or "kindred spirit", 心の友 (kokoro no tomo), literally reads as "friend of my heart", which is incredibly cute.

Ukridge speaks very casually here, with 貴公 (kikou) being an old-fashioned form of "you" generally said to equals or social inferiors (for the record, it's often rude to even say "you" to someone at all in Japanese if you don't know them well - you're meant to use the third person even when talking to them - and while I have not yet read it in Japanese I suspect Ukridge is kikouing everyone he meets), and changes the negative verb ending ない (nai) to the slangier, more colloquial ね (ne) at every turn. It's such a big part of Ukridge's character that his casual nature has zero regard for class, situation, or decorum, and I love how this translation reflects that.

Easily the best part of this entire translation is the fact that Ukridge's personal pronoun (what he uses to say "I") is 我輩 (wagahai), which carries the connotation of the user being absurdly arrogant. There's a reason Wagahai wa Neko de Aru (I Am a Cat) by Natsume Soseki gives the cat protagonist this pronoun. He is a cat. Cats are like that. And apparently, so is Ukridge. The cocky bastard. I love him so much.

conclusion: there needs to be a Ukridge manga like, yesterday. please. there's already a Jeeves one and it's great. a Ukridge manga would be so much fun.

#ukridge#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#extremely embarrassing for corky to be down bad for a guy who uses wagahai. very funny#i'm very curious how they went for corky in katakana#and how they interpreted billson's accent#looking forward to seeing the japanese take on all my favorite lines...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

me and the boys (gender-neutral) when we psychologically analyze p. g. wodehouse characters created entirely to be purveyors of silly

i love looking too deeply into joke characters. it's like a court jester jingled onto the stage and started performing and i stood up in my seat and wailed audibly

#jeeves and wooster#ukridge#bertie wooster#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#i love a Silly Little Guy with a Catastrophic Family Life#bertie and ukridge both aren't aware of the fact that they're kind of a mess and that fascinates and saddens me

26K notes

·

View notes

Note

hi its the ring for jeeves analysis anon sorry im so illusive can't help my mysterious nature its inexplicable, quick question: have you read any psmith??? if so thoughts on them do you hold any opinions, postulations, assumptions etc. in re: queercoding, possibly even queerer coded than jeeves series??

Mysterious Ring for Jeeves anon! Just when I thought you forever borne away on the four winds, you have returned again to the masked ball to drop your calling card (three black goose feathers and a shard of mother of pearl collected from the silver sands by the light of the season's first full moon) into the hollowed-out tree stump at the edge of the garden. I receive and understand your message, and shall await your signal directly the cock crows thrice.

Now, to answer your question, Psmith had been on my "should really get around to it" list for ages, but this ask prompted me to finally download the Psmith in the City audiobook and put it on while I was packing and now I DO have thoughts! My first thought was that I had no idea working in a bank was so much like working in hospitality, but that's a post for another day.

Short answer: yes, this is queer as hell. And it isn't even the first non-Jeeves Wodehouse book I've read that felt even more queer coded than Jeeves-- the first was Ukridge (aka It's Always Sunny in London), which I'm going to go ahead and compare and contrast with Psmith, because I feel like I'm starting to uncover a pattern in Wodehouse's POV characters that I think could lend support to queer readings of a lot of his works.

For those who aren't familiar, Ukridge is ALSO the tale of an extremely blatant self-insert character inescapably captivated by the magnetic personality of an old school friend. Corky, a starving writer who's always struggling to get his articles published in magazines and is totally not Wodehouse by a different name, is deeply irritated by the get-rich-quick schemes of his freeloader friend Ukridge. He knows Ukridge is taking advantage of him, and rarely has a positive thing to say about him, yet clearly finds something about his indefatigable spirit immensely compelling: "to me this tame subsidence into companionship with a rich aunt in Wimbledon seemed somehow an indecent, almost a tragic, end to a colourful career like that of S. F. Ukridge. [...] I should have had more faith. I should have known my Ukridge better. I should have realised that a London suburb could no more imprison that great man permanently than Elba did Napoleon."

This quotation is followed by Corky finding out that Ukridge has acquired six Pekinese dogs (which will turn out to have been pinched from his aunt) that he's planning to train for show biz, and would Corky like to invest. If you wanted to know.

The queerness is rather more unilateral in Ukridge than in Psmith, but no less glaring for that. Corky really doesn't seem to like it when Ukridge is interested in a woman, and shows little to no interest in women himself, iirc. I mean, the first time he sees Ukridge in the company of a woman he sounds almost betrayed: "Never in the course of a long and intimate acquaintance having been shown any evidence to the contrary, I had always looked on Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge, my boyhood chum, as a man ruggedly indifferent to the appeal of the opposite sex. I had assumed that, like so many financial giants, he had no time for dalliance with women—other and deeper matters, I supposed, keeping that great brain permanently occupied." THIS is his reaction to Ukridge announcing that he wants to get engaged: "The thing was too cataclysmal for my mind. It overwhelmed me." GIRL.

If I had no prior familiarity with Wodehouse and I read this book, I would be asking which straight boy hurt him.

Finally, one of the Ukridge stories contains this exchange between Corky and a pugilist Ukridge has decided he's going to make a star, which I would like to present here without comment before moving on:

“You ever been in love, mister?” I was thrilled and flattered. Something in my appearance, I told myself, some nebulous something that showed me a man of sentiment and sympathy, had appealed to this man, and he was about to pour out his heart in intimate confession. I said yes, I had been in love many times. I went on to speak of love as a noble emotion of which no man need be ashamed. I spoke at length and with fervour.

Skipping merrily along, let us now come back around to Psmith in the City, starting with the primary POV character and then bringing in Psmith's relationship to him.

Mike is an even more blatant self-insert than Corky. This would have been obvious even if I didn't already know that in his young adulthood Wodehouse, owing to the fact that his father could no longer afford to send him to Oxford, had worked as a clerk at the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank. The jokes are too precise to not be from personal experience. As Mike is our audience avatar, he's naturally the more normal, less distinctive character. Despite his relative nondistinctness, though, he's written in such a way that it's clear Wodehouse deeply identified with him. The sections where he's feeling emotions like homesickness or out-of-placeness or sympathy, for instance, are very vivid and evocative. You really feel what Mike is feeling.

Then there's Psmith, manic pixie dream boy and destroyer of bad managers. He handles every situation with a debonair smile on his face and breezy condescension in his voice, completely unflappable... except with regards to Mike. His feelings typically aren't described in as much detail as Mike's are, but it's obvious he adores him, to the point of slight codependence. He needs Mike near him to hear his thoughts on life, and nobody else will do. As much as he tries to maintain his air of blithe nonchalance at all times, real emotion slips through whenever the situation involves separating him from Mike or Mike being in danger.

When Mike is moved to the Cash Department, Psmith is immediately desolate. I love the way he's like, "but- but if you relocate Mike, then WHO pray tell will PAY ATTENTION TO ME?" and this is a genuine crisis for him. He resents the new guy just for not being Mike. Local annoyingly imperturbable gadfly inconsolable due to boybestfriend going to work in a different department than him, more at eight. Then, when Mike gets into the fight at Clapham Common, Psmith feels genuine fear as he prepares to intervene in the fight and tell Mike to make a run for it.

Another factor I feel makes the queer coding stronger here is that unlike Bertie and Jeeves, there isn't an obvious plausibly deniable reason for Psmith and Mike to always be together. Jeeves is Bertie's employee. He's an unreasonably devoted and loyal employee, but you expect a gentleman to be accompanied by his valet about town, and for the gentleman and valet to share accommodation.

Psmith and Mike are just like that. They live together because they like each other and want to. Psmith spends the whole book essentially treating Mike like his boyfriend and sugar baby, again, simply because he wants to. I mean, the novel literally opens with Psmith bringing Mike home to meet his parents, and Psmith's father later refers to Mike as the "youngster [Psmith] brought home last summer." Psmith invites Mike to go out on an excursion with him "hand in hand" not once, but twice. The end goal of all his scheming is for him and Mike to be together at Cambridge.

'I need you, Comrade Jackson,' he said, when Mike lodged a protest on finding himself bound for the stalls for the second night in succession. 'We must stick together. As my confidential secretary and adviser, your place is by my side. Who knows but that between the acts tonight I may not be seized with some luminous thought? Could I utter this to my next-door neighbour or the programme-girl? Stand by me, Comrade Jackson, or we are undone.' So Mike stood by him.

I find it very notable that despite one of the big themes of the book being Mike and Psmith feeling uncertain about the future and trying to figure out what they want to do in life, neither of them ever mentions or thinks about marriage as something they might want someday. From what I've seen it looks like that might change in later books, but it stuck out in this one. And it's not like they couldn't have! Mr Waller's daughter and her on-again-off-again fiance were at that extremely awkward dinner, and that could have prompted a thought about whether or not the prospect of engagement sounded personally appealing to either of the boys.

This book feels like a wish fulfillment fantasy in much the same way the Jeeves books do. Imagine you have a fascinating friend who, using his money and/or resourcefulness, can rescue you from your terrible job and terrible shitty apartment (or other, richer varieties of soup, if you're Bertie Wooster), freeing you to pursue the life you truly want. He's clever, and quotes all your favorite Shakespeare lines, and is intensely devoted to you (he's also kind of a weird stickler about clothes but you can put up with that). And all he asks for it is that you look at him with awed wonder and gratitude and tell him he's a genius a few times a day.

So! In conclusion, I think you could read this as romantic or queerplatonic according to your fancy, but there's certainly nothing straight about it. And loath as I am to speculate about the personal lives of people who were alive in recent memory, I'm kind of starting to have some questions about P. G. Wodehouse. But that's neither here nor there. I'm going to go read some fanfic. Thank you so much for the question, Mysterious Ring for Jeeves Anon!

#“stand by me comrade jackson or we are undone” is such a romantic fucking line i-#btw i'm hoping to resume working on the ring for jeeves analysis soon#i've finished moving and i think i've put it down long enough to look at it fresh#psmith#psmith in the city#ukridge#pg wodehouse#p. g. wodehouse#my meta#asks#long post

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book 49: Ukridge

My last (!!) choice book, I decided to do something humerous and while there are a lot of good, modern books out there they have tremendous waiting lists. So, I went with an old favorite, P.G. Wodehouse. A man so Bertie Wooster that he thought that showing he had a stiff upper lip by collaborating mildly with the Nazis would please the British government. But before all that unpleasantness he had a good handful of short stories about hilarious mishaps that he turned into semi-coherent novels. The most famous are the Jeeves and Wooster stories, but his personal favorite was reportedly Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge.

Ukridge is a get-rich-quick mad fellow and usually it ends to his detriment, or more often to the detriment of his friends. The novel Ukridge folloes 10 such schemes through the eyes of his friend Corky Corcoran. He has the Wodehousian stern aunt, and all the Edwardian trappings you could want.

BEST LINE: "He’s the sort of boy you have to be patient with and bring out, if you understand what I mean. I think he grows on you.”

“If he ever tries to grow on me, I’ll have him amputated.”

SHOULD YOU READ THIS BOOK: Yes, you can't go wrong with P.G. Wodehouse and Ukridge is him at his finest.

ART PROJECT:

Ukridge always wears a Makintosh and pince-nez.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can’t recommend enough looking up PG Wodehouse librevox audiobook recordings…. Found out they are on podcasts as a format too

Currently listening to Love In The Time of Chickens 🐓 💞

Apple podcast link for it ^^^

#pg wodehouse#love in the time of chickens#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#podcasts#audibooks#Jeremy garnet

1 note

·

View note

Text

Two Crooked Stanleys’ I love are

Stanley filbrick Pines

Stanley featherstonehaugh Ukridge.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scrolling through Goodreads reviews of Leave It to Psmith and came across one that claimed “the random appearance of Ukridge is awesome,” that although his name isn’t mentioned it has to be him. Initially confusing, but I think they must have been referring to this passage, and on second thought, they just might have a point there.

As Psmith had taken up a stationary position and the population of the lobby was for the most part in a state of flux, he was finding himself next to some one new all the time; and now he decided to accost the individual whom the reshuffle had just brought elbow to elbow with him. This was a jovial-looking soul with a flowered waistcoat, a white hat, and a mottled face. Just the man who might have written that letter.

The effect upon this person of Psmith’s meteorological remark was instantaneous. A light of the utmost friendliness shone in his beautifully-shaven face as he turned. He seized Psmith’s hand and gripped it with a delightful heartiness. He had the air of a man who has found a friend, and what is more, an old friend. He had a sort of journeys-end-in-lovers’-meetings look.

“My dear old chap!” he cried. “I’ve been waiting for you to speak for the last five minutes. Knew we’d met somewhere, but couldn’t place you. Face familiar as the dickens, of course. Well, well, well! And how are they all?”

“Who?” said Psmith courteously.

“Why, the boys, my dear chap.”

“Oh, the boys?”

“The dear old boys,” said the other, specifying more exactly. He slapped Psmith on the shoulder. “What times those were, eh?”

“Which?” said Psmith.

“The times we all used to have together.”

“Oh, those?” said Psmith.

Something of discouragement seemed to creep over the other’s exuberance, as a cloud creeps over the summer sky. But he persevered.

“Fancy meeting you again like this!”

“It is a small world,” agreed Psmith.

“I’d ask you to come and have a drink,” said the jovial one, with the slight increase of tensity which comes to a man who approaches the core of a business deal, “but the fact is my ass of a man sent me out this morning without a penny. Forgot to give me my note-case. Damn’ careless! I’ll have to sack the fellow.”

“Annoying, certainly,” said Psmith.

“I wish I could have stood you a drink,” said the other wistfully.

“Of all sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest are these, ‘It might have been,’” sighed Psmith.

“I’ll tell you what,” said the jovial one, inspired. “Lend me a fiver, my dear old boy. That’s the best way out of the difficulty. I can send it round to your hotel or wherever you are this evening when I get home.”

A sweet, sad smile played over Psmith’s face.

“Leave me, comrade!” he murmured.

“Eh?”

“Pass along, old friend, pass along.”

Resignation displaced joviality in the other’s countenance.

“Nothing doing?” he inquired.

“Nothing.”

“Well, there was no harm in trying,” argued the other.

“None whatever.”

“You see,” said the now far less jovial man confidentially, “you look such a perfect mug with that eyeglass that it tempts a chap.”

“I can quite understand how it must!”

“No offence.”

“Assuredly not.”

#Leave It to Psmith#P. G. Wodehouse#Psmith#Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge#your one-stop shop for crossovers#because there's possibly a fleeting appearance from Bertie too#in the play this character turns out to be Ed Cootes

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading Ukridge. I just have the mental image of one of Ukridge’s schemes inevitably going wrong, except this time there’s somehow a dead body and Ukridge gets falsely accused of murder. And now a very frustrated, very fed-up, very worried Corky is visiting him in his cell before the trial, and Ukridge is like “well, Corky old horse, I don’t think I can mansplain manipulate manwhore my way out of this one”

and James “Corky” Corcoran sends a telegram to his American cousin Bruce “Corky” Corcoran to ask if has any ideas, only for Bruce to send a telegram to his buddy Bertie Wooster, who then proceeds to get Jeeves in on it, and now the least experienced people in solving crime (and Jeeves, who probably somehow has crime-solving experience) have to figure out how to solve a murder

#red randomness#ukridge#jeeves and wooster#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#bertie wooster#reginald jeeves#james corky corcoran#bruce corky corcoran#this post was 90% just to create that mansplain line#someday I’ll write this fanfic (probably never)#I would love a silly crime solving comedy in which both Wodehousian duos realize they might be in love with the bestie#but I’ll have to make that happen myself

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yet another post for no one, but I think Ukridge and Corky’s relationship is essentially what would happen if you fused the relationship between Raffles and Bunny with the relationship between Ritchieverse Holmes and Watson but then made the more chaotic member of the pair less competent and successful, and then didn’t have anything of great dramatic significance happen to them. Which amuses me greatly.

#red randomness#ukridge#crime and cricket#rdj holmes#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#james corky corcoran#a. j. raffles#bunny manders#sherlock holmes#john watson#they’re truly all about two deeply codependent guys#and the ostensibly more sensible of them is not sensible at all#because he cannot stay away from the other due to his fondness for him despite his flaws#so they are a matched pair despite the fire

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

tiny spiritual sequel to one of my favorite posts of all time, @probablyday’s ukridge buys bitcoin

#red randomness#ukridge#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#james corky corcoran#sometimes the characters you love would get up to terrible shit in the modern day#and you know what. that’s okay

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

probable reason why Bowles likes Ukridge: his easy geniality, combined with the fact that he treats Bowles, a former butler, neither with reverence (like much of the working class) nor with disdain (like much of the upper class), but just as a person and ���one of the boys”, must be wonderfully refreshing to him

funnier reason why Bowles likes Ukridge: he is well aware that Corky is unfathomably down bad for the world’s most cheerfully frustrating man and ships them for his own amusement

final verdict: both

#red randomness#ukridge#stanley featherstonehaugh ukridge#bowles#james corky corcoran#corkridge#every day I craft more Ukridge posts to send into the careless void#why did I get homosexual brainrot for a Wodehouse series with essentially no fandom#anyway I gotta finish reading the last three stories and then I’ll write my essay on why Corky is Wodehouse’s gayest character#in the meantime apologies to my followers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love Among the Chickens

Love Among the Chickens

Love Among the Chickens By P. G. Wodehouse, narrated by Graham Scott.

Eternal optimist Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge conceives another foolproof scheme to make himself – and his adoring new wife, Millie – rich: chicken farming!

“No expenses, large profits, quick returns. Chickens, eggs, and the money streaming in faster than you can bank it.” Dragging along his long-suffering old friend,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

In 1903 Wodehouse was visited by Herbert Westbrook, a prep-school master who wanted to make a career as a writer, with a letter of introduction from one of Wodehouse’s former colleagues in the bank. A friendship sprang up between the two men, and Wodehouse was invited to visit him at his school. This establishment was eccentrically run by Baldwin King-Hall, a cricket fanatic who used to hold a morning meeting from his bed at ten o’clock while he ate his breakfast. Baldwin-King and Wodehouse also took to each other and Wodehouse left his Chelsea lodgings to move to Emsworth House where he took rooms above the stables. Wodehouse took no part in the teaching, but helped to put on plays and played in cricket matches on the school grounds. Westbrook was a classicist with great charm and ambitious plans for the future. He had a communal attitude to property, but only in the sense of what’s yours is mine, for he would borrow money without intending to pay it back, and on one occasion borrowed Wodehouse’s dress clothes, leaving their rightful owner, who had needed them that night, to go out attired in the suit of an uncle of an entirely different build. This became raw material for the story First Aid for Dora. That this is a Ukridge story is no coincidence, for Ukridge was based upon Westbrook. Or certainly the Ukridge of the short stories the Ukridge who first appeared, in the first adult novel Wodehouse wrote, Love among the Chickens, is a slightly different beast. The Ukridge here is an amalgam of two people, the second of whom is Carrington Craxton. He and a friend had set themselves up as chicken farmers in Devon without either of them knowing anything about chickens. Townend, a friend of Craxton’s, relayed tales of some of their adventures to Wodehouse who used them as a basis for his novel. But Ukridge is not the central character in this story, it is the narrator, Jeremy Garnet. Wodehouse was keen to establish a character for whom he could write a series of stories, and sixteen years later in Ukridge he saw someone who could be developed into such a character so Ukridge become a bachelor, more seedy and more fully drawn. Part of the style of Love among the Chickens was retained in that the tales are told by a journalist friend, the bachelor James Corcoran, who inherited this role from Garnet. In other respects the style of the only Ukridge novel, which was all over the place, was abandoned. The novel starts with the story being narrated about Jeremy Garnet, then becomes narrated by him, and finishes with his wedding, which is written up in play form. When, fourteen years later, Wodehouse came to revise the work for a new edition, he made Garnet narrate the whole story, which is now minus the wedding scene. As a comic work the novel lacks sufficient humour; it never really takes off. The situations are not developed enough. Maybe the author took the plots too closely from real life. However, it was the book which launched him in America. He had turned down an offer from a friend living in the States to help him get his school stories placed with an American publisher. He wanted to hit America as an adult writer. His school stories had served a purpose in getting him up and running in Britain and out of the bank, but they are not where he saw his long-term future. Ukridge is the most immoral of Wodehouse’s leading characters. Wodehouse loved his creation and wrote about him at intervals throughout his life. The final Ukridge short story occurs in A Few Quick Ones, published in 1959. The Ukridge stories divide fans of P. G. Wodehouse. Some simply do not care for them, mainly because they do not care for Ukridge. Rogues can be popular characters, but they normally have to be lovable rogues. Ukridge is immoral, but lacks the charm or softer side to make us like him. One of the most popular characters in the history of British television sit-com is Del Boy in Only Fools and Horses. He is a rogue and a crook, but he has a kinder side and can be generous with his money, time and emotions. He is a sympathetic character. He is also unsuccessful, which makes us well disposed to him rather than jealous. Ukridge is also unsuccessful on the whole, although he has his minor triumphs. The problem with these minor triumphs is that sometimes his victim is not deserving. When in Ukridge’s Dog College he does down his landlord by getting out of paying his rent and getting the landlord to settle his tradesmen’s accounts do we cheer him on? What have we got against his landlord? Psmith takes as his targets the more legitimate figures of established authority. We do not mind if they are taken down a peg or two; they are high enough already. But Ukridge does down those less able to take the punishment. Ukridge sponges off his fellow strugglers. It is hard to sympathize with Ukridge. This detracts from the stories, which are well written and crafted, and often have more plot than Wodehouse would usually use for a short story. But Wodehouse’s fondness for his character is considerably above that which the average reader has. Richard Usbourne in A Wodehouse Companion states that Ukridge contains “some of the best stories that Wodehouse ever wrote.” The stories are perhaps better than our enjoyment of them. In Wodehouse at Work he writes “one loves that man.” The problem is that many readers do not. Ukridge is a liar, thief, blackmailer and con man. He has little in the way of conscience or scruples. He has few, if any, compensatory characteristics to make us like him. Corky’s landlord, Bowles, approves of him and that he is good with dogs is about all you can say in his defence. It is not nearly enough. Putting the case for Ukridge might involve pointing out that, though he sets out to double-cross people, he often ends as the one who is double-crossed instead. However, this does not make us feel enough sympathy for him; “getting his just deserts” is a more likely reaction. It is easy to admire some of the Ukridge stories, harder to enjoy them.

The Novel Life of P. G. Wodehouse, Roderick Easdale

(Westbrook and King's Hall make an appearance elsewhere in the Wodehouse canon. In Mike at Wrykyn, when asked about his previous education, Mike replies that he was at “A private school in Hampshire [...]. King-Hall’s. At a place called Emsworth. [...] One of the masters, a chap called Westbrook, was an awfully good slow bowler.” Curiously enough, Ukridge is an Old Wrykinian himself.)

#The Novel Life of P. G. Wodehouse#Roderick Easdale#p. g. wodehouse#Ukridge#Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge#Herbert Westbrook#Love among the Chickens

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

allieinarden replied to your post: allieinarden replied to your post: Mike Nor no...

He’s lucky he ended up with Psmith and not Jeeves or Ukridge…though I doubt he’d put up with Jeeves. He’d get out of that arrangement real fast.

True. Mike knows what he can put up with better than Bertie does, and Jeeves probably would be seeking employment elsewhere pretty quickly. He wouldn't put up with Ukridge either--at least, not for very long. There'd be an I-jolly-well-resign scene, and that would be that.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge: ENFP

Extroverted (energized by social interaction and the outer world)

iNtuitive (innovative and theorizing)

Feeling (bases decisions on values)

Perceiving (adaptable and spontaneous)

Dominant Function: Extroverted iNtuition (Ne)

The dominant function is one’s “default setting,” the function one feels most comfortable using. Ne is concerned with exploring possibilities, developing multiple ideas and trying as many as possible, innovating, being creative, initiating concepts for projects, looking for new options, picking up on hidden meanings and interpreting them, brainstorming and strategizing from here-and-now.

Ukridge has an anything-is-possible mindset, a wild imagination, and theories about everything, especially things he knows nothing about (like chickens and the Irish Question). Not content to stick to one job (or, really, any job…), he adopts many trades and doesn’t stay in one place very long. He has little regard for most conventions and has his own unique way of approaching the world, with a too-loud voice and a casual attitude toward everyone, even the formidable Bowles. Although he may consider him hardheadedly practical, he’s better at generating ideas than carrying them out and really doesn’t have much of a grasp on reality, concentrating more on his over-optimistic schemes for the future. Ultimately (depending on his mood), he’s not easily daunted but ready with a new concept whenever the previous one fails, naively certain that all will work out for the best. Any objects are met with injunctions to have more “vision and the big, broad, flexible outlook.” Flexibility comes easily enough to him: he can strategize in the moment (such as inventing pretexts to get into the house of a girl he’s interested in) and makes light of life’s difficulties (as long as they don’t directly inconvenience him).

Auxiliary Function: Introverted Feeling (Fi)

The auxiliary function assists and balances the dominant function and is used when one helps or mentors someone. Fi is concerned with focusing on personal/individual values, experiencing intense emotions which are not directly expressed and may be concealed, expressing feelings indirectly, understanding and defining personal feelings/values and likes and dislikes, determining what is worthy of being valued and stood up for, balancing peace and conflict, striving for consistency of values.

Ukridge is independent in his moral code. He lacks the need for others’ approval and doesn’t adapt well to things like school rules. He’s willing to defy conventions and go to bizarre lengths to achieve his ends, whether it be money-making or marrying the girl he loves. Although his moral code is unorthodox at best, it seems to make complete sense to him. He has a moral rationalization for everything he does (“How can I pay the man? Apart from the fact that at this stage of my career it would be madness to start flinging money right and left, there’s the principle of the thing!”) and persuades others according to value-based arguments (convincing his creditors that they’re wronging him by demanding payment) or dramatics and flattery (generally with Corky and George Tupper). He expects self-sacrifice from other people—never himself. However, he can be quite recklessly generous to his friends when he’s financially able, and he is capable of taking pity on another person (Dora Mason), though maybe only because he’s had a similar experience. He makes a great production out of being “altruistic” to old schoolmates. His emotions are intense and tend to fluctuate, depending on the situation. He can change his feelings toward someone within minutes. Everything is taken extremely personally, and he will go on long rants (“Upon my Sam, it’s a little hard!...”) whenever he feels he’s been unfairly treated. According to Jeremy Garnet, he can “[induce] himself to be broad-minded for five minutes” but will easily “slip back to his own personal point of view and became once more the man with a grievance.”

Tertiary Function: Extroverted Thinking (Te)

The tertiary function is the area where one seeks guidance and accepts help, where one is either childish or childlike and vulnerable. It can also be a source of relief, a means of unwinding, or how one expresses creativity. Te is concerned with making sure procedures are efficient, less concerned with precision than clarity, finding practical/pragmatic solutions, aiming for achievement and success, using external data to prove a point, planning and organizing to achieve a definite goal, using orderly logic in clear steps.

Developing plans to carry out his ideas comes naturally to Ukridge. He can be elaborately detailed about how something is to be carried out, talks out all his theories, and is confident that he can do anything. He has strong opinions which he seldom hesitates to express: he loves to give (usually unsolicited) advice and clings doggedly to his theories even when they’re clearly impractical (“But Ukridge says his theory is mathematically sound, and he sticks to it”). He knows what he wants and goes after it, his philosophy being “Tell him exactly what you want and stand no nonsense. If you don’t see what you want in the window, ask for it.” However, his Te is also immature in many ways. He can be demanding and delegates all the unpleasant tasks to his friends (whether they want to be involved or not). The Te pragmatism manifests in him as down Machiavellianism sometimes: he has no qualms about taking, stealing, or otherwise mooching off other people, or of lying to get off paying his rent. Empathy isn’t his strong point either; he’s often more interested in what he can get out of other people than in them themselves.

Inferior Function: Introverted Sensing (Si)

The inferior function is the area one is at one’s weakest in and least comfortable using, something one might aspire to but not be able to use well. It can emerge in times of great stress as a negative version of itself. Si is concerned with recalling past experiences, maintaining traditions, storing detailed information, linking and comparing what one knows to situations in the present, following established customs and procedures, valuing stability and the tried-and-true.

Ukridge’s use of Si is hazy at best. He has Ne foresight but lacks attention to detail, as seen in how he got expelled from Wrykyn (disguising himself when sneaking out at night but neglecting to remove his school cap) and his habit of writing crucial letters and then forgetting to send them. He usually leaves mundane problems and details to other people. Although he’s most often forward-thinking, he does uses past experiences as evidence for his belief that all his farfetched schemes will work out. But the past isn’t a pleasant thing for him. He views his school days with sentimentality, has low moods where he broods on what might have been, and has a tendency to tell long, sad life stories at three in the morning to whatever captive audience is handy.

1 note

·

View note