#speckled sea lice

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[Blog #5] Fall 2022, Bishop, Limón & Stevens

Beginning this week, I will be reviewing individual poems rather than collections. My Contemporary Poetry Seminar professor only assigned 4 poetry books for that course; the rest were individual poems.

Today, I am comparing and contrasting Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Fish,” Ada Limón's “The Conditional” and Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” by using my professor’s T.R.I.F.F.I.D. method

Before I analyze the similarities and differences between those three poems, I would love to greet anyone who happens to stumble upon this blog post.

This is the link to my first blog post on Ada Limón's The Carrying (2018):

My Contemporary Poetry Seminar professor assigned a poetry book collection or individual poems every other week. My main objective was to dissect a few poems (4-5) that left an impression on me while using his T.R.I.F.F.I.D. method.

Tone: the voice, mood, or attitude the reader believes the author is conveying through subject and word choice.

Rhythm: the pattern and beat between the stressed and unstressed word syllables.

Imagery: the details told through the five senses (touch aka physical, sound aka auditory, sight aka visual, taste aka gustatory and smell aka olfactory).

Figure: or figure of speech, is the non-literal expression of language. Figures of speech include hyperbole, irony, metaphor, simile, anaphora, antithesis and chiasmus.

Form: the way a poem is presented on paper or a screen. Think of how the author physically shapes the poem -- the use of dialogue, line spacing, paragraph breaks, rhythms and patterns.

Idea Density: how the author expresses their ideas throughout their poem. Can be literal (concrete) and/or figurative (vague or hidden).

Diction: the word choice and arrangement within a piece.

Our first subject is Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Fish” (1946):

Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Fish” leans on visual imagery to create an air of mystique, wonder, and empathy for the titled fish.

For example, we are shown visuals through the metaphors and environmental resemblances Bishop utilizes to describe the fish in intricate details:

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down. (9-21)

Here, Bishop incorporates these visuals such as ‘ancient wallpaper’ and environmental infestations to show how long said fish spent in the water-- its survival until the narrator captured it.

Ada Limón's “The Conditional” (2020) uses visual imagery to transform every day/known objects into outlandish metaphors to convey a sense of ‘staying together’ no matter how crazy/apocalyptic life becomes.

For example, Limón shows us the visual images through the bizarre ‘what ifs’/outcomes of a known entity/idea (non-human) such as the moon and the sun:

Say tomorrow doesn't come.

Say the moon becomes an icy pit.

Say the sweet-gum tree is petrified.

Say the sun's a foul black tire fire.

Say the owl's eyes are pinpricks.

Say the raccoon's a hot tar stain.

Say the shirt's plastic ditch-litter.

Say the kitchen's a cow's corpse. (1-8)

It is in these visual images of these known and transformed concepts that we are encouraged to see the world differently.

Though Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” (1917) conveys visual imagery, it also incorporates many indescribable/indefinite ideas that give the poem a realistic, grounded feeling.

For example, we are given big concepts such as minds and beauty in between the visual imagery of the blackbird or the environmental:

I

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

II

I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

III

The blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.

It was a small part of the pantomime.

IV

A man and a woman

Are one.

A man and a woman and a blackbird

Are one.

V

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after. (1-17)

What have I learned from all three poems?

Overall, I believe Bishop and Limón's poems are more similar to one another, since both women showcase their ideas through visual metaphors and descriptions.

Stevens, on the other hand, grounds his poem in a more realistic place as he relies on prose writing and limitless concepts. In a way, Bishop and Limón's big use of visuals makes their poem seem livelier and colorful, whereas Stevens gives an air of silences and muteness.

Despite the 74-year difference between Bishop and Limón's poem, their similarities convey the lasting power of certain poetic techniques -- imagery.

Who are Elizabeth Bishop, Ada Limón and Wallace Stevens?

Both Bishop and Stevens are Limón's predecessors: Bishop won an Academy Fellowship and served as one of the Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets organization, whereas Stevens won a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his Collected Poems (1955) poetry collection.

Limón, as mentioned in her personal blog post, is currently the 24th Poet Laureate of the United States.

For more information and poetry by Bishop, Limón and Stevens, check out the links below:

Lastly, are there any poems from different poets -- despite their varying topic(s) and theme(s) -- that share similar tones, imageries, figure of speeches, etc.?

Feel free to comment some below!

0 notes

Text

The Fish

By Elizabeth Bishop [x]

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn't fight. He hadn't fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled with barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen —the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly— I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. —It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip —if you could call it a lip— grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels—until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go.

0 notes

Text

The Seashore. Written by Jennifer Cochran. Illustrated by Kenneth Lilly, Patricia Mynott, James Nicholls, and George Thompson . 1973.

Internet Archive

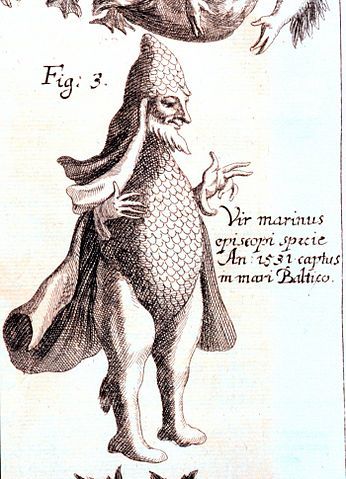

A.) Calanus finmarchicus

B.) Larva of the shrimp Crangon crangon

C.) Larva of the barnacle Semibalanus balanoides

D. + E.) Different stages of the growth of Carcinus maenas

F.) One of the stages of Pisidia longicornis

G.) Eurydice pulchra

H.) Larva of Clytia Johnstoni

#marine life#crustaceans#copepods#shrimp#barnacles#acorn barnacles#crabs#european green crabs#long-clawed porcelain crabs#isopods#speckled sea lice#cnidarians

358 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Fish” by Elizabeth Bishop

I caught a tremendous fish

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of his mouth.

He didn't fight.

He hadn't fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

—It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

—if you could call it a lip—

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Fish

By Elizabeth Bishop

I caught a tremendous fish

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of his mouth.

He didn't fight.

He hadn't fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

—It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

—if you could call it a lip—

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

256K notes

·

View notes

Quote

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn't fight. He hadn't fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled with barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen - the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly- I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. - It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip - if you could call it a lip grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels- until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go.

The Fish by Elizabeth Bishop

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Bishop — An Actual Bishop?

Elizabeth Bishop is not a poet we read for her versificatory virtuosity or marvelous musicality; one need only take a look at The Fish to see that her poems — admittedly not without exception, but overwhelmingly — exhibit less poeticality than many writers' prose. No, her appeal lies not in the traditional qualities we would associate with poetry, but rather in her treatment of the subjects of her poems. She is a poet of incredible empathy, attentiveness and ability to wonder, a poet who exhibits admirable goodness and compassion — acting consistently as per the teachings of the Bible.

Perhaps the best example of Bishop's compassion and empathy is The Prodigal — her retelling of Jesus's parable of the Prodigal Son.1 She conveys sympathy through her detailed description of the son's suffering — an incredibly vivid "brown enormous odor" surrounds him; the sty in which he lives is "plastered halfway up with glass-smooth dung"; his mental state is no better than his surroundings as he is plagued by "his shuddering insights, beyond his control,/ touching him." Bishop focuses on the bestialisation of the son to show him being shunned and ignored by society, dismissed and offered no help. Ken Stone points out the "recurring tendency to disparage humans recognized as different or other (whether on the basis of gender, race, nation, class, or any other marker of difference) by animalizing them, turning them into beasts who then can be treated in ways that we routinely allow ourselves to treat animals."2 This tendency is seen elsewhere in the Bible — for example, Jacques Derrida reads the story of the Garden of Eden as linking animal difference with sexual difference and the boundary between humanity and God3 — and in this case it is made stronger by the fact that the Jews believed pigs to be unclean animals. The animal is associated with the other — Ellen Armour, in a theological essay on Derrida’s Le Toucher, refers to the "fourfold" of "man and his others: his racial and sexual others, his divine other (God), and the animal."4 Armour suggests that modernity is characterized by "a certain configuration of these four elements" in which ‘man occupies the center while the animals, God, as well as man’s raced and sexed others, constitute a network of mirrors that reflect man back to himself by supposedly securing his boundaries."5 This begs the question: why is the son set apart from the rest of society? Perhaps it is simply that his choices led him to poverty and that made him looked down upon. It would not be unreasonable, however, to argue that his situation is the product of prejudice — likely due to homosexuality or other queerness. Nonetheless, this is not the place for a queer reading of The Prodigal (another blessay, perhaps?) — what is important is that Bishop, for one, refuses to shun the son and treats him with an admirable degree of empathy, exemplifying Jesus's commandment "Love your neighbour as you love yourself."6

The Fish is another poem that can be read in light of the Bible. The most obvious link is the ending: "And I let the fish go," which shows empathy and reflects Jesus's teachings: "Happy are those who are merciful to others; God will be merciful to them!"7 What is perhaps more interesting is that Bishop describes the fish at length as being extremely ungainly and repulsive — "Here and there/ his brown skin hung in strips/ like ancient wallpaper"; "He was speckled with barnacles,/ fine rosettes of lime,/ and infested/ with tiny white sea-lice" — yet seems to value it highly despite its seeming worthlessness. This parallels the Bible once again:

The stone which the builders rejected as worthless turned out to be the most important of all. This was done by the Lord; what a wonderful sight it is!8

We see more of Bishop's ability to see the smallest of things as wonderful in Filling Station. It is similar to The Fish for its oddly sympathetic descriptions of ugliness — "oil-soaked, oil-permeated/ to a disturbing, over-all/ black translucency"; "a set of crushed and grease-/ impregnated wickerwork" — but focuses more on the work done in the background by "somebody" who "loves us all". Her focus on efforts which would generally go unnoticed is once again consistent with what Jesus sought to teach us: "Whoever wants to be first must place himself last of all and be the servant of all."9 Bishop elevates the 'servant' to an almost God-like entity that encompasses us all with love.

An extension of Bishop's empathy is her ability to put herself in the mindset of someone else, especially a child. Many of her poems are written from the perspective of herself10 as a young girl, and she masterfully captures the unique way of seeing the world that children are gifted with. First Death in Nova Scotia shows a childhood mentality employed to confront death; a vivid imagination conjures wild explanations to try and come to terms with what is happening. The ending in particular combines fantasy and fairytale with logic in a way that is typical of young children — Arthur was invited to the royal court, but how can he go if he cannot open his eyes? Sestina is a more unusual example because the narrator is an omniscient entity, not a child, but despite employing an adult vocabulary it focuses on a child's mindset — the surreal image of little moons falling off the pages of the book; the characterisation of the almanac as "clever"; the "marvelous" Marvel stove. These examples bring to mind the words of Jesus: "I assure you that unless you change and become like children, you will never enter the Kingdom of heaven."11 Bishop's ability to take on an innocently immature persona is yet another example of her sympathetic, empathetic nature.

Bishop may not have actually been a bishop12, but she was probably a better person than a good deal of them. One needs only to look at the news to know how often the latter seem to completely ignore the teachings of the Bible and do utterly terrible things.13

Luke 15:11-32 ↩︎

Ken Stone, 'Judges 3 and the Queer Hermeneutics of Carnophallogocentrism' in The Bible and Feminism: Remapping the Field, edited by Yvonne Sherwood and Anna Fisk (Oxford University Press, 2017), 264. ↩︎

Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, edited by Marie-Louise Mallet and translated by David Wills (Fordham University Press, 2008), 101. Cited in Stone, 'Queer Hermeneutics of Carnophallogocentrism', 265. ↩︎

Ellen T. Armour, ‘Touching Transcendence: Sexual Difference and Sacrality in Derrida’s Le Toucher’, in Derrida and Religion: Other Testaments, edited by Yvonne Sherwood and Kevin Hart (Routledge, 2005), 353. Cited in Stone, 'Queer Hermeneutics of Carnophallogocentrism', 263. ↩︎

Ibid. 358. ↩︎

Matthew 22:39. All Bible quotes in this blessay are from the Good News New Testament, Today's English Version. ↩︎

Matthew 5:7 ↩︎

Matthew 21:42 citing Psalm 118:22 ↩︎

Mark 9:35 ↩︎

'Someone else' and 'herself' are not contradictory here; the fact that her mindset as an adult is radically different than that of her as a child justifies the separation. ↩︎

Matthew 18:3 ↩︎

Not that this has been conclusively disproven. ↩︎

Not to go off on a tangent yet again, but here are some examples. ↩︎

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

EXODUS FROM EDEN

A Far Cry 5 AU: The Plagues of Egypt

Hope County Gothic 2018- WEEK 1- PROJECT AT EDEN’S GATE

Word count: 1327

WARNING: Blood, dead animals, frogs, insects, rotting food, sickness/disease, starvation, scars and wounds, self-flagellation, child death, major character death, child abuse references, self harm

A Pharaoh once sat on high, his towering empire built by the hands of enslaved Israelites. But he defied the commandments of God, and his hubris was punished with pestilence, famine and death, wrought upon his lands through God’s messenger- a man he once called his brother.

Joseph Seed sits on high, his Project, his Eden inhabited by the unwilling, the unrepentant. And now God sends another messenger, one who trusts in and upholds the law, to warn the false prophet-

Let my people go.

Joseph Seed seeks to build a garden. An Eden where God’s chosen will be saved from the fury of an impending, catastrophic reckoning. With those he loves at his side- his brothers, Jacob and John, his sister Faith, his wife and infant daughter- he fabricated a devout and holy empire, claiming the people of Hope County for indoctrination into his ‘family’. He believes he is saving them. He believes he hears the voice of God.

He is mistaken, misguided by demons.

In a small town on the border of Joseph’s empire, a young police Deputy wanders through the lush Montana landscape, seeking solace and serenity. They had once been a part of Joseph’s family, enticed by his soothing words, his condemnations of government and society, his genuine care for the world’s ‘unfortunates’. But they had seen his true face. His lust for power. His hungry gaze. His serpent tongue.

They had fled.

And it is in that liminal forest that they hear the true voice of God, whispered first through low hanging branches, slipping gently through evergreen leaves, before alighting a bush and illuminating the glade with an opalescent flame.

God’s message is clear.

The people of Hope County must be freed from the clutches of the false prophet.

Under a star-ridden sky, silent in the early hours of the morning, the Deputy meets Joseph in his church and explains to the Father of God’s commandment.

Unwavering in his faith, Joseph simply replies:

‘God will not let you take them.’

The Deputy pleads, but to no avail. And so they deliver the first warning:

...I will strike the water...

The Henbane River, once blue and speckled with the green haze of Bliss, grows thick and stains slowly with crimson. John is holding a sinner below the surface of the water, seemingly cleansing him, but instead he watches in horror as his hands redden and the scent of bitter metal claws its way down his throat. The sinner in his firm grasp begins to thrash and, as John brings him back into the cool night air, he looks upon a man glossed with so thick a sheen of blood, that he wonders how he is not drowning.

...I will plague your whole country with frogs...

Soon, Faith collects flowers by the tainted river. The soles of her bare feet are slick with the blood that has begun to soak into the soil. It is not long until the wild lobelias she gathers are scattered along the grassy path where she fled, as frogs are spat from the river’s depths in their thousands.

...Smite the dust of the land, that it may become lice...

The prisoners in Jacob’s care, their clothes stained with the rotting juice from meat they devoured, are used to the bristle of the Judges’ fur and the itching of lice. But upon the Father’s third denial of freedom, they see their captors begin to scratch the skin from their scalps, bloody flesh under their fingernails, their bodies overrun with the gnawing of a hundred thousand tiny mouths.

...Pharaoh hardened his heart...

Upon the release of a swarm of flies, which in turn brought disease as they settled on the harvest, chewing their way into the stocks hidden deep within the bunkers, Joseph’s voice fills the Deputy’s radio frequency. His words are faint from the unceasing cacophony of wings. He asks that the Deputy cease the plagues. He promises freedom for the people of Hope County.

The land was cleansed of the infestation.

But still, the people were not free.

...the LORD will bring a terrible plague upon the livestock in the field...

The bulls in Holland Valley collapse in the untended grass, their ribs prominent as they starve where they lie. Ravenous cougars rip all but the prongs from the elk corpses on the hot tarmac road through the Whitetail Mountains. The meat is poisoned by sickness. It is not long before the wild cats also succumb.

... festering boils will break out on men...

Joseph dabs soothing ointment upon the sores on John’s back, where they nestle among his deep scars. They grow inflamed and fever racks his body, droplets beading across his brow as though he was newly baptised. He bandages Jacob’s arms, where the patchwork of vermilion welts have given way to a new shroud of bulging sores. The Father is kept awake through the humid night by the screams of his infant daughter, boils burning into her tiny face.

...The LORD sent thunder and hail...

The Angels in the fields were nothing more than dust now. Each was incinerated by a lightning strike that evaporated their milky eyes, before claiming their bodies entirely. The church in Fall’s End no longer had a steeple, the hail having shattered it down. The people of Hope County had heard it crumble. The bell had tolled endlessly as ice rained upon it, and had then fallen silent. The thunder had rocked the earth and reduced the mighty statue of the Father to rubble.

...they will devour what little you have left...

There are no longer pumpkins at Rae-Rae’s farm. No longer are the fields blotted with fleshy fruits, but instead, dark with locusts that even devour the metal fencing, the wood of an old dog house, the tarp that covers a rusted truck. Radio towers appear like pillars of black salt, writhing in the fading sunlight. Joseph hides with his family, still ignoring the Deputy’s pleas.

...darkness that can be felt...

Madness came with three days of darkness. The Seed family kneel before the altar, whipping the flesh from their backs, unable to comprehend why God would allow this false prophet to punish them, his chosen, when they have all suffered so much already. Many of their flock walk out of the compound, never to be seen again. The shadow is suffocating, the silence oppressive. Joseph knows no light can be found in sleep- they are all haunted with nightmares.

...loud wailing... worse than there has ever been or ever will be again...

Joseph doesn’t cry when his baby daughter suddenly pales in his arms, her skin and lips fading to a periwinkle blue, cold to the touch. He does not respond to his wife’s heavy sobbing as she clings to the swaddled child. He holds her hand, gently winding his rosary around her palm. He doesn’t cry when he hears John screaming at the hunched figure of his eldest brother, blistered hands gripping at Jacob’s well worn camo jacket and oddly peaceful face, in desperate hope that he might wake. He barely hears the wailing that rings through the compound, through the valley and the mountains. God’s chosen few, chosen no more.

Instead, he radios the Deputy. He speaks in a quiet voice. It is a voice that lingers in the hollow space somewhere between forlorn resignation and tempestuous rage.

And the people of Hope County are at last freed. Purged of Bliss, their scars and swollen tattoos bandaged, the Deputy walks with them through the gates, as the sun rises once more.

Joseph watches them go.

He sits alone in the ruins of his garden. His Eden. He waits for guidance, an echo of the Voice that had let him climb so high and then allowed his world to be torn apart around him.

He is met with silence.

It is the same aching silence he had known as a boy in the moments after his Father had finished beating him. Perhaps he was still there now, in that moment, resting on a porch in the heat of a Georgia summer. Perhaps he would indeed see the Red Sea part, in the form of a gash in his back where leather met skin.

Perhaps this was not his promised land.

And taking a knife in his malnourished fingers, he cuts into his tall forehead, a permanent reminder to his forsaken soul:

Exodus 7:17

“By this you will know that I am the Lord”.

-----------------------------------

Bold quotations are from the Book of Exodus. Painting is The Great Day of His Wrath, by John Martin.

Thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed! This is my first fanfic for this fandom- I haven’t actually written fanfiction for a few years, (at least, not written down, I write it in my head all the time hahaha) and I’ve been concentrating on my meta essays for FC5, so I apologise if I was a bit rusty!

Also, disclaimer: I’ve never actually read the Bible, and obviously this is a fictional interpretation, so there are almost definitely some inaccuracies, but I tried to research as best I could! I wasn’t sure whether the death of the first born applied to daughters as well as sons, or to adults who were firstborn, but I used both for the sake of story.

Finally, I unashamedly acknowledge that I was 100% inspired by the Prince of Egypt.

#hope county gothic#hope county gothic 2018#far cry 5#far cry 5 au#far cry 5 fanfiction#project at eden's gate#joseph seed#john seed#jacob seed#faith seed#it's pretty wordy#and descriptive#but I was too frightened to write dialogue for my first fc5 fic#also confession#I've had this in my drafts for months#I was too scared to post#I've been putting it off all week too#but the first week of the gothic event is nearly over#so I had to pull myself together hahahaha

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poems by Elizabeth Bishop

The Fish

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn't fight. He hadn't fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled with barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen —the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly— I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. —It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip —if you could call it a lip— grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels—until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go.

***

A Cold Spring

for Jane Dewey, Maryland Nothing is so beautiful as spring —Hopkins

A cold spring: the violet was flawed on the lawn. For two weeks or more the trees hesitated; the little leaves waited, carefully indicating their characteristics. Finally a grave green dust settled over your big and aimless hills. One day, in a chill white blast of sunshine, on the side of one a calf was born. The mother stopped lowing and took a long time eating the after-birth, a wretched flag, but the calf got up promptly and seemed inclined to feel gay. The next day was much warmer. Greenish-white dogwood infiltrated the wood, each petal burned, apparently, by a cigarette-butt; and the blurred redbud stood beside it, motionless, but almost more like movement than any placeable color. Four deer practised leaping over your fences. The infant oak-leaves swung through the sober oak. Song-sparrows were wound up for the summer, and in the maple the complementary cardinal cracked a whip, and the sleeper awoke, stretching miles of green limbs from the south. In his cap the lilacs whitened, then one day they fell like snow. Now, in the evening, a new moon comes. The hills grow softer. Tufts of long grass show where each cow-flop lies. The bull-frogs are sounding, slack strings plucked by heavy thumbs.

Beneath the light, against your white front door, the smallest moths, like Chinese fans, flatten themselves, silver and silver-gilt over pale yellow, orange, or gray. Now, from the thick grass, the fireflies begin to rise: up, then down, then up again: lit on the ascending flight, drifting simultaneously to the same height, –exactly like the bubbles in champagne. –Later on they rise much higher. And your shadowy pastures will be able to offer these particular glowing tributes every evening now throughout the summer.

***

Insomnia

The moon in the bureau mirror looks out a million miles (and perhaps with pride, at herself, but she never, never smiles) far and away beyond sleep, or perhaps she's a daytime sleeper. By the Universe deserted, she'd tell it to go to hell, and she'd find a body of water, or a mirror, on which to dwell. So wrap up care in a cobweb and drop it down the well into that world inverted where left is always right, where the shadows are really the body, where we stay awake all night, where the heavens are shallow as the sea is now deep, and you love me.

***

The Armadillo

for Robert Lowell

This is the time of year when almost every night the frail, illegal fire balloons appear. Climbing the mountain height, rising toward a saint still honored in these parts, the paper chambers flush and fill with light that comes and goes, like hearts. Once up against the sky it's hard to tell them from the stars— planets, that is—the tinted ones: Venus going down, or Mars, or the pale green one. With a wind, they flare and falter, wobble and toss; but if it's still they steer between the kite sticks of the Southern Cross, receding, dwindling, solemnly and steadily forsaking us, or, in the downdraft from a peak, suddenly turning dangerous. Last night another big one fell. It splattered like an egg of fire against the cliff behind the house. The flame ran down. We saw the pair of owls who nest there flying up and up, their whirling black-and-white stained bright pink underneath, until they shrieked up out of sight. The ancient owls' nest must have burned. Hastily, all alone, a glistening armadillo left the scene, rose-flecked, head down, tail down, and then a baby rabbit jumped out, short-eared, to our surprise. So soft!—a handful of intangible ash with fixed, ignited eyes. Too pretty, dreamlike mimicry! O falling fire and piercing cry and panic, and a weak mailed fist clenched ignorant against the sky!

***

Sestina

September rain falls on the house. In the failing light, the old grandmother sits in the kitchen with the child beside the Little Marvel Stove, reading the jokes from the almanac, laughing and talking to hide her tears. She thinks that her equinoctial tears and the rain that beats on the roof of the house were both foretold by the almanac, but only known to a grandmother. The iron kettle sings on the stove. She cuts some bread and says to the child, It's time for tea now; but the child is watching the teakettle's small hard tears dance like mad on the hot black stove, the way the rain must dance on the house. Tidying up, the old grandmother hangs up the clever almanac on its string. Birdlike, the almanac hovers half open above the child, hovers above the old grandmother and her teacup full of dark brown tears. She shivers and says she thinks the house feels chilly, and puts more wood in the stove. It was to be, says the Marvel Stove. I know what I know, says the almanac. With crayons the child draws a rigid house and a winding pathway. Then the child puts in a man with buttons like tears and shows it proudly to the grandmother. But secretly, while the grandmother busies herself about the stove, the little moons fall down like tears from between the pages of the almanac into the flower bed the child has carefully placed in the front of the house. Time to plant tears, says the almanac. The grandmother sings to the marvelous stove and the child draws another inscrutable house.

***

In the Waiting Room

In Worcester, Massachusetts, I went with Aunt Consuelo to keep her dentist's appointment and sat and waited for her in the dentist's waiting room. It was winter. It got dark early. The waiting room was full of grown-up people, arctics and overcoats, lamps and magazines. My aunt was inside what seemed like a long time and while I waited I read the National Geographic (I could read) and carefully studied the photographs: the inside of a volcano, black, and full of ashes; then it was spilling over in rivulets of fire. Osa and Martin Johnson dressed in riding breeches, laced boots, and pith helmets. A dead man slung on a pole —"Long Pig," the caption said. Babies with pointed heads wound round and round with string; black, naked women with necks wound round and round with wire like the necks of light bulbs. Their breasts were horrifying. I read it right straight through. I was too shy to stop. And then I looked at the cover: the yellow margins, the date.

Suddenly, from inside, came an oh! of pain —Aunt Consuelo's voice— not very loud or long. I wasn't at all surprised; even then I knew she was a foolish, timid woman. I might have been embarrassed, but wasn't. What took me completely by surprise was that it was me: my voice, in my mouth. Without thinking at all I was my foolish aunt, I—we—were falling, falling, our eyes glued to the cover of the National Geographic, February, 1918.

I said to myself: three days and you'll be seven years old. I was saying it to stop the sensation of falling off the round, turning world. into cold, blue-black space. But I felt: you are an I, you are an Elizabeth, you are one of them. Why should you be one, too? I scarcely dared to look to see what it was I was. I gave a sidelong glance —I couldn't look any higher— at shadowy gray knees, trousers and skirts and boots and different pairs of hands lying under the lamps. I knew that nothing stranger had ever happened, that nothing stranger could ever happen.

Why should I be my aunt, or me, or anyone? What similarities— boots, hands, the family voice I felt in my throat, or even the National Geographic and those awful hanging breasts— held us all together or made us all just one? How—I didn't know any word for it—how "unlikely". . . How had I come to be here, like them, and overhear a cry of pain that could have got loud and worse but hadn't?

The waiting room was bright and too hot. It was sliding beneath a big black wave, another, and another.

Then I was back in it. The War was on. Outside, in Worcester, Massachusetts, were night and slush and cold, and it was still the fifth of February, 1918.

***

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster. Lose something every day. Accept the fluster of lost door keys, the hour badly spent. The art of losing isn’t hard to master. Then practice losing farther, losing faster: places, and names, and where it was you meant to travel. None of these will bring disaster. I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or next-to-last, of three loved houses went. The art of losing isn’t hard to master. I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster, some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent. I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster. —Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident the art of losing’s not too hard to master though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

***

The End of March

for John Malcolm Brinnin and Bill Read: Duxbury

It was cold and windy, scarcely the day to take a walk on that long beach Everything was withdrawn as far as possible, indrawn: the tide far out, the ocean shrunken, seabirds in ones or twos. The rackety, icy, offshore wind numbed our faces on one side; disrupted the formation of a lone flight of Canada geese; and blew back the low, inaudible rollers in upright, steely mist. The sky was darker than the water —it was the color of mutton-fat jade. Along the wet sand, in rubber boots, we followed a track of big dog-prints (so big they were more like lion-prints). Then we came on lengths and lengths, endless, of wet white string, looping up to the tide-line, down to the water, over and over. Finally, they did end: a thick white snarl, man-size, awash, rising on every wave, a sodden ghost, falling back, sodden, giving up the ghost. . . . A kite string?—But no kite. I wanted to get as far as my proto-dream-house, my crypto-dream-house, that crooked box set up on pilings, shingled green, a sort of artichoke of a house, but greener (boiled with bicarbonate of soda?), protected from spring tides by a palisade of--are they railroad ties? (Many things about this place are dubious.) I'd like to retire there and do nothing, or nothing much, forever, in two bare rooms: look through binoculars, read boring books, old, long, long books, and write down useless notes, talk to myself, and, foggy days, watch the droplets slipping, heavy with light. At night, a grog à l'américaine. I'd blaze it with a kitchen match and lovely diaphanous blue flame would waver, doubled in the window. There must be a stove; there is a chimney, askew, but braced with wires, and electricity, possibly —at least, at the back another wire limply leashes the whole affair to something off behind the dunes. A light to read by—perfect! But—impossible. And that day the wind was much too cold even to get that far, and of course the house was boarded up. On the way back our faces froze on the other side. The sun came out for just a minute. For just a minute, set in their bezels of sand, the drab, damp, scattered stones were multi-colored, and all those high enough threw out long shadows, individual shadows, then pulled them in again. They could have been teasing the lion sun, except that now he was behind them —a sun who'd walked the beach the last low tide, making those big, majestic paw-prints, who perhaps had batted a kite out of the sky to play with.

***

Objects & Apparitions

for Joseph Cornell

Hexahedrons of wood and glass, scarcely bigger than a shoebox, with room in them for night and all its lights. Monuments to every moment, refuse of every moment, used: cages for infinity. Marbles, buttons, thimbles, dice, pins, stamps, and glass beads: tales of the time. Memory weaves, unweaves the echoes: in the four corners of the box shadowless ladies play at hide-and-seek. Fire buried in the mirror, water sleeping in the agate: solos of Jenny Colonne and Jenny Lind. "One has to commit a painting," said Degas, "the way one commits a crime." But you constructed boxes where things hurry away from their names. Slot machine of visions, condensation flask for conversations, hotel of crickets and constellations. Minimal, incoherent fragments the opposite of History, creator of ruins, out of your ruins you have made creations. Theater of the spirits: objects putting the laws of identity through hoops. "Grand Hotel de la Couronne": in a vial, the three of clubs and, very surprised, Thumbelina in gardens of reflection. A comb is a harp strummed by the glance of a little girl born dumb. The reflector of the inner eye scatters the spectacle: God all alone above an extinct world. The apparitions are manifest, their bodies weigh less than light, lasting as long as this phrase lasts. Joseph Cornell: inside your boxes my words became visible for a moment.

Translated from the Spanish of Octavio Paz

***

My love, my saving grace, your eyes are awfully blue. I kiss your funny face, your coffee-flavored mouth. Last night I slept with you. Today I love you so how can I bear to go (as soon I must, I know) to bed with ugly death in that cold, filthy place, to sleep there without you, without the easy breath and nightlong, limblong warmth I’ve grown accustomed to? —Nobody wants to die; tell me it is a lie! But no, I know it’s true. It’s just the common case; there’s nothing one can do. My love, my saving grace, your eyes are awfully blue early and instant blue.

Unpublished manuscript poem

1 note

·

View note

Text

SOLUTION AT Academic Writers Bay Please respond to the questions (and sub-questions) below. Please make sure that your answers are focused on the questions and that you’re writing as grammatically as possible!. Please use quotes to support your answer, but try to quote only a line or two at a time, maximum: Mostly, I want to read your analysis! When you answer questions, always explain why you’re answering them in the way you’ve chosen to answer them. In total, you should write about 750-1000 in total for this assignment. (More is fine, and even recommended!) 1. Drama—Imagine that a friend has come to you for help. She is auditioning for a play, and she wants to use “The Fish” as her dramatic monologue. She wants you to help her craft the best performance possible. So she asks you to help her figure out: A. How should her emotional state change as she reads the poem to convey the realization the narrator has at the end of the poem? B. How should she play the narrator? How old is this person, what is their personality, what do they value. etc.? C. Your friend doesn’t want to put on a costume for the audition, but she does want to imagine what her character looks like and is wearing while she performs. What do you suggest? D. Likewise, she can’t build a set, but she wants to imagine a location where this is taking place. What do you suggest? E. What lines of the poem do you think she needs to emphasize most in her performance? 2. Fiction A. The poem almost wholly devoted to describing a fish. How does the description of the fish become the plot of the poem? In other words, how do the descriptions help you understand what the narrator is thinking, and how do those thoughts lead her to what is perhaps the unexpected ending? (Remember, use examples to explain your thinking!) B. What is the tone of “The Fish”? How does the tone help you understand the descriptions? C. What lesson(s), if any, do you think this poem is trying to impart to readers? 3. Poetry A. What are some specific images that Bishop uses that are unusual? How do these unusual images lead the reader to an understanding of the poem? B. The poem is slim on the page; its lines do not often end where a sentence or even phrase ends. In other words, Bishop is breaking the line of poetry early and often in “The Fish.” Why? How do the line-breaks and the slimness of the poem contribute to a reader’s understanding of it? C. “The Fish” is a very famous poem, but it is clearly using elements of drama (specifically, dramatic monologue) and fiction (e.g. it has a very clear plot). What does this dramatic story gain by being written as a poem? The Fish, by Elizabeth Bishop I caught a tremendous fishand held him beside the boathalf out of water, with my hookfast in a corner of his mouth.He didn’t fight.He hadn’t fought at all.He hung a grunting weight,battered and venerableand homely. Here and therehis brown skin hung in stripslike ancient wallpaper,and its pattern of darker brownwas like wallpaper:shapes like full-blown rosesstained and lost through age.He was speckled with barnacles,fine rosettes of lime,and infestedwith tiny white sea-lice,and underneath two or threerags of green weed hung down.While his gills were breathing inthe terrible oxygen—the frightening gills,fresh and crisp with blood,that can cut so badly—I thought of the coarse white fleshpacked in like feathers,the big bones and the little bones,the dramatic reds and blacksof his shiny entrails,and the pink swim-bladderlike a big peony.I looked into his eyeswhich were far larger than minebut shallower, and yellowed,the irises backed and packedwith tarnished tinfoilseen through the lensesof old scratched isinglass.They shifted a little, but notto return my stare.—It was more like the tippingof an object toward the light.I admired his sullen face,the mechanism of his jaw,and then I sawthat from his lower lip—if you could call it a lip—grim, wet, and weaponlike,hung five old pieces of fish-line,or four and a wire leaderwith the swivel still attached,with all their five big hooksgrown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the endwhere he broke it, two heavier lines,and a fine black threadstill crimped from the strain and snapwhen it broke and he got away.Like medals with their ribbonsfrayed and wavering,a five-haired beard of wisdomtrailing from his aching jaw.I stared and staredand victory filled upthe little rented boat,from the pool of bilgewhere oil had spread a rainbowaround the rusted engineto the bailer rusted orange,the sun-cracked thwarts,the oarlocks on their strings,the gunnels—until everythingwas rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!And I let the fish go. CLICK HERE TO GET A PROFESSIONAL WRITER TO WORK ON THIS PAPER AND OTHER SIMILAR PAPERS CLICK THE BUTTON TO MAKE YOUR ORDER

0 notes

Text

The Fish

Elizabeth Bishop

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn't fight. He hadn't fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled with barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen —the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly— I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. —It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip —if you could call it a lip— grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels—until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go.

0 notes

Photo

Oysters open more widely during the new moon, though nobody knows exactly why.

Why oysters close on the full moon—and more odd lunar effects on animals

New research shows that the moon has unexpected and fascinating impacts on marine animals, from oysters to worms to plankton.

DOUGLAS MAIN

APRIL 17, 2019

A full moon is looming—and it will have a big impact on animals, especially those in the ocean.

Recent studies show that many types of animals have biological clocks finely tuned to the cycles of the moon, which drives fascinating and sometimes bizarre patterns of behavior.

Besides revealing hidden aspects of animal life, the research also has implications for better understanding the circadian clocks present in all animals, including humans. (Read more about how the moon affects life on Earth.)

The first circadian clocks evolved in the oceans, so studying them in marine animals can tell us a lot about how they evolved and how they work and interact with each other, explains Kim Last, a researcher at the Scottish Association for Marine Science.

Zooplankton

Take zooplankton. These tiny animals engage in the world’s largest migration, which takes place every night when they swim toward the surface to feed on algae. These mini-creatures are prey to a many larger animals that hunt by sight. So to avoid predation, zooplankton head for the depths at dawn.

“The predators follow them until they run out of light,” Last says. This requires an intricate circadian rhythm, usually regulated by the sun. However in the Arctic, where the winter sun cannot be seen for months on end, some zooplankton also have an internal clock that is set to the moon. Two, actually. (Find out more about circadian rhythms.)

Get photos, videos, and exclusive journalism about wildlife and pets, plus special offers.

By signing up for this email, you are agreeing to receive news, offers, and information from National Geographic Partners, LLC and our partners. Click here to visit our Privacy Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.

When the winter moon is full over the Arctic, it stays above the horizon for a handful of days (depending on latitude), and during this time, zooplankton dive to take cover from predators. But while the moon is out, it also rises and sets—and the zooplankton respond, rising and diving over the course of this cycle, which takes 24 hours and 50 minutes.

Zooplankton like this type of krill rise to the surface at night and dive during the day, but they are also impacted by light from the moon.

Oysters

Oysters, which open their shells to eat and spawn, also have a lunar rhythm, a new study shows.

In a recent experiment, French researchers carefully monitored how widely a dozen oysters opened their shells during a 3.5-month period. The team used a high-tech device that quantified the valve opening every two seconds, as described in a paper published in the journal Biology Letters.

They found that two types of oysters in Arcachon Bay in southwestern France were significantly more open during new moons and more closed when the moon was full. In addition, the oysters could tell the difference between the first quarter moon and the third quarter moon, and were significantly more open (by nearly 20 percent) at the latter.

It’s unknown why the oysters do this, though it could be due to more algae or other food being available during the new moon and as the year progresses, says study leader Damien Tran, a researcher at the University of Bordeaux.

The lunar cycle could influence food availability by its impact on the tides and thus the ocean’s currents. When the moon is full or new, it is directly in line with Earth and the sun, exerting a strong pull on the ocean and thus causing more pronounced tides, explains David Wilcockson, a marine biologist at Aberystwyth University in Wales who wasn’t part of the study.

On the other hand, when the moon is half-full, it is most out of alignment with Earth and the sun, producing so-called neap tides, which are the weakest of the tidal cycle.

The oysters’ rhythms could also have something to do with conditions favorable for mating. The moon, with its corresponding impact on tides and ocean currents, drives many types of marine organisms to mate at specific times of the month and year.

Palolo worms

For instance, oysters, corals, and many types of ocean animals breed by “broadcast spawning,” wherein they release sperm and eggs together in a precisely timed, orgiastic explosion.

Palolo worms, which live in warm ocean waters worldwide, engage in a rather extreme example of this.

South Pacific palolo worms, for example, spend most of the years feeding on organic matter on the seafloor or within coral. But in the austral spring, the rear of their bodies turn into sacks of egg or sperm.

During two days in October, these break off from the rest of the worm, and using an eyespot within, swim toward the surface—and the light of the moon. Exactly a month later, they repeat this feat in even great numbers, during the last quarter moon of November.

A pod of orcas hunts off the Norwegian coast. Orcas are specialist predators: They have finely-tuned strategies for hunting specific prey, like herring, which means they don't cope well with environmental change.

Orcas work together to "carousel hunt." Here, an orca drives herring toward the surface. Then members of the pod will bunch the herring together, giving others a chance to feed.

Southern rockhopper penguins swim toward shore in the Falkland Islands. They use their flipper-like wings to dive fast and deep in search of prey like fish and krill.

Rockhopper penguins climb a steep cliff in the Falklands. Overfishing, pollution, and other perils have dramatically reduced the population of these gregarious birds.

A large colony of Cape fur seals covers a beach near Cape Fria, Namibia. The seals are hunted en masse in Namibia for their oil and fur.

Researchers attempt to satellite tag blue whales off the coast of California. Blue whales, the largest animals on Earth, were hunted to the brink of extinction in the early 20th century. They've made only a partial recovery.

Striped mullet fish swim in a lake in Florida's Fanning Springs State Park. Mullets are a common food source for many larger species. They can thrive in both salt water and fresh water and live all over the world.

Lionfish swim over a reef in the Red Sea. Lionfish are venemous and are considered invasive species in some parts of the world, particularly the Caribbean. They've thrived there, taking the place of other species, like the grouper, that have become overfished.

Opalescant inshore squids lay more than 50,000 eggs at a time and live for six to nine months. Their rapid reproduction rate means that they're potentially positioned to evolve quickly enough to cope with perils such as plastic waste and warming waters.

Anglerfish live deep in the ocean, where there is no light. Females, like the one seen here, "host" males on their bodies. The males latch on with their teeth and are permanent parasites.

Moon jellyfish are pictured off the coast of Alaska. They don't have a respiratory system and breathe by diffusing oxygen through the translucent membranes covering their bodies.

A great white shark swims off Seal Island, in South Africa. Great whites are long-living apex predators and evolve very slowly, making them particularly susceptible to deteriorating ocean conditions due to climate change.

A great white shark catches a decoy seal, set out by researchers. The predators are often hunted for their fins and meat, and they're also caught accidentally, as bycatch in fishing nets.

Thousands of olive ridley sea turtles emerge from the sea once a month to lay eggs on Ostional Beach, in Costa Rica. Dogs, storks, and vultures frequently prey on hatchlings and eggs—as do humans.

Tourists visit Ostional Beach as turtles emerge to lay eggs. It's legal for residents of the beach community to dig up eggs to sell. The beach's management says that profits stay in the community and that less than 1 percent of the eggs laid every year are collected.

Female olive ridley sea turtles all emerge at the same time every month, usually the week before the new moon, to lay eggs. They dig out a cone-shaped hole in the sand, about a foot and a half deep, and lay their eggs inside.

Speckled sea louse

Even more ordinary behaviors may be driven by the moon as well. Consider the speckled sea louse (Eurydice pulchra).

These little guys burrow in the sand in the intertidal zone, which is covered by water at high tide, and dry when it’s low. They have an internal lunar clock wherein they are active at 12.4-hour intervals, coinciding with the tides, explains Wilcockson.

Sea lice also have a monthly cycle, and are more active during the full and new moons, with their stronger currents, and more sedate during the weak neap tide, he says. But they also have a sun-linked daily cycle: They get dark during the day to protect themselves from solar rays, and are paler at night.

Lab experiments have shown these are separate. “We could abolish the daily cycle, and leave the tidal cycles intact,” Wilcockson says.

Sand hoppers

Another underappreciated creature that lives on British beaches: sand hoppers (Talitrus saltator).

“If you disturb them during the day, they’ll migrate back up the shore and bury themselves in the sand,” Wilcockson says. “If you disturb them at night, they’ll migrate down the shore to feed on stuff that’s washing up.”

Wilcockson explains that scientists hypothesized the crustaceans use their antennae to navigate via the sun, which has been shown to be the case in monarch butterflies. In a 2016 study published in Scientific Reports, Wilcockson and colleagues removed sand hoppers’ antennae and saw how they navigated in a nighttime and daytime environment.

Contrary to expectations, the animals could navigate just find during the day without antennae—presumably using their brains (and light through their eyes). But at night, without these appendages, they were totally lost. The experiment showed sand hoppers have independent clocks tied to each heavenly body, in different parts of their body.

“Our sand hopper has a lunar clock and a solar clock in the antennae and the brain, respectively,” he adds.

0 notes

Text

“The Fish” by Elizabeth Bishop (born on this day in 1911)

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn't fight. He hadn't fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled with barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen - the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly- I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. - It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip - if you could call it a lip grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels- until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go.

326 notes

·

View notes

Note

have none of your followers heard of female poets. here are a few: katherine philips, phillis wheatley, elizabeth barrett browning, elizabeth bishop, gwendolyn brooks, warsan shire. choose one or as many as you like. just like. women write poetry. you know this, i know this, teach your followers this.

okay i am doing Katherine Philips, both because i love this and because it's to her "friend" on their excellent "friendship," oh my word:

To My Excellent Lucasia, on Our Friendship

I did not live until this time Crowned my felicity,When I could say without a crime, I am not thine, but thee.

This carcass breathed, and walked, and slept, So that the world believedThere was a soul the motions kept; But they were all deceived.

For as a watch by art is wound To motion, such was mine:But never had Orinda found A soul till she found thine;

Which now inspires, cures and supplies, And guides my darkened breast:For thou art all that I can prize, My joy, my life, my rest.

No bridegroom’s nor crown-conqueror’s mirth To mine compared can be:They have but pieces of the earth, I’ve all the world in thee.

Then let our flames still light and shine, And no false fear control,As innocent as our design, Immortal as our soul.

i love the last two stanzas especially; crown-conqueror is a great word, and "innocent as our design,/immortal as our soul" is a wonderful flag flung up in defiance of the world.

other standouts: "I am not thine, but thee"; "crowned my felicity."

elizabeth bishop:

okay, here is a thing: I don't like "One Art." I do like Bishop! just not that.

The Fish

I caught a tremendous fishand held him beside the boathalf out of water, with my hookfast in a corner of his mouth.He didn’t fight.He hadn’t fought at all.He hung a grunting weight,battered and venerableand homely. Here and therehis brown skin hung in stripslike ancient wallpaper,and its pattern of darker brownwas like wallpaper:shapes like full-blown rosesstained and lost through age.He was speckled with barnacles,fine rosettes of lime,and infestedwith tiny white sea-lice,and underneath two or threerags of green weed hung down.While his gills were breathing inthe terrible oxygen—the frightening gills,fresh and crisp with blood,that can cut so badly—I thought of the coarse white fleshpacked in like feathers,the big bones and the little bones,the dramatic reds and blacksof his shiny entrails,and the pink swim-bladderlike a big peony.I looked into his eyeswhich were far larger than minebut shallower, and yellowed,the irises backed and packedwith tarnished tinfoilseen through the lensesof old scratched isinglass.They shifted a little, but notto return my stare.—It was more like the tippingof an object toward the light.I admired his sullen face,the mechanism of his jaw,and then I sawthat from his lower lip—if you could call it a lip—grim, wet, and weaponlike,hung five old pieces of fish-line,or four and a wire leaderwith the swivel still attached,with all their five big hooksgrown firmly in his mouth.A green line, frayed at the endwhere he broke it, two heavier lines,and a fine black threadstill crimped from the strain and snapwhen it broke and he got away.Like medals with their ribbonsfrayed and wavering,a five-haired beard of wisdomtrailing from his aching jaw.I stared and staredand victory filled upthe little rented boat,from the pool of bilgewhere oil had spread a rainbowaround the rusted engineto the bailer rusted orange,the sun-cracked thwarts,the oarlocks on their strings,the gunnels—until everythingwas rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!And I let the fish go.

I could live without the rainbow line; but the rest is a wonderful network of metaphor and beautiful description, and the last line is a perfect release of the tension built up by the length of that description.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fish

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn’t fight. He hadn’t fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled with barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen —the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly— I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. —It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip —if you could call it a lip— grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels—until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go.

Elizabeth Bishop

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Fish (1946)

I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn't fight. He hadn't fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled with barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen —the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly— I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. —It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip —if you could call it a lip— grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels—until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go.

- Elizabeth Bishop

0 notes