#source: the mystery of edwin drood

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“ I loved a maid as fair as summer with sunlight in her hair „

“ I loved a maid as red as autumn with sunset in her hair „

“ I loved a maid as white as winter with moonglow in her hair „

Sansa Month 2023 : day fifteen - seasons of my love

#sansa stark#fc: olivia hussey#cersei lannister#fc: catherine deneuve#daenerys targaryen#fc: tamzin merchant#source: donkey skin#peau d'ane#source: romeo and juliet#source: the mystery of edwin drood#source: a clash of kings#asoiaf edits#made by me#sansamonth2023#sansastarkappreciationfest2023

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

12, 16, 23, & 37 for the theater ask?

12: favorite opening number?

Literally opening numbers are The Best part of musicals for me so this is a very difficult question!!!!! But the first musical I ever really campaigned to see was Six, and so seeing Ex-Wives performed in person was an absolutely magical experience <3

16: favorite female solo?

Always The Woman from Teeth and Moonfall from The Mystery of Edwin Drood have been absolute hits with me lately!!! Sonya Alone from Great Comet is one I can actually sing so that gets an honorable mention 🫶

23: what’s a song you like from a musical you don’t?

The Andrew Lippa take on A Little Princess is such an… interesting… musical in how it handles the source material, but there are two songs from it (Once Upon a Time and Soldier On) that do a rather good job of characterizing while also just being good songs!!

37: musical theatre moment that lives in your head rent free?

oh my fucking god. i think about one specific double-casting alllllll the fucking time. like what the fuck do you mean that old prince bolkonsky and his son andrey are typically played by the same actor. here have these videos. im killing myself.

youtube

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rochester Cathedral Interior by F. G. Kitton

Illustration for Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood, p. xxvi

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

Source

#english imagination#english culture#albion#art#england#english art#english christianity#charles dickens#english illustrator#illustrator#illustration#english churches#English cathedral#rochester#Rochester cathedral#Victorian#19th century

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

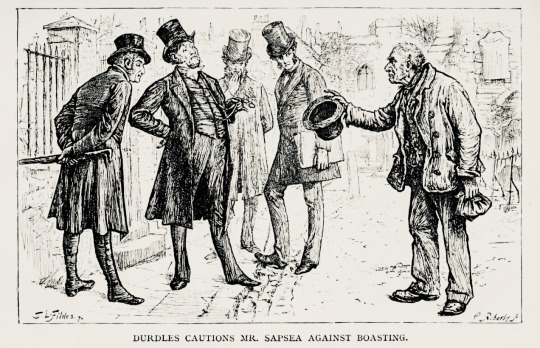

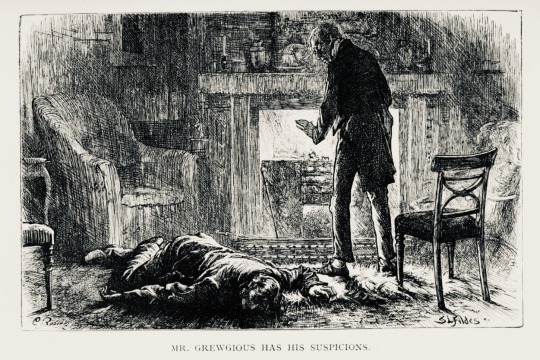

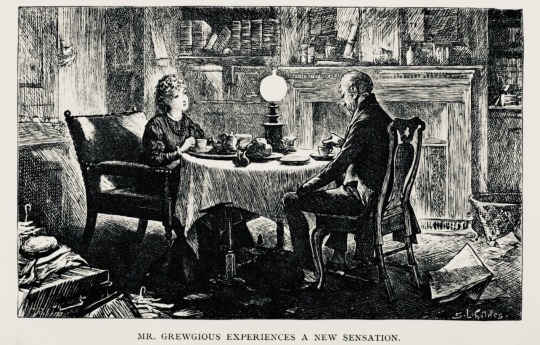

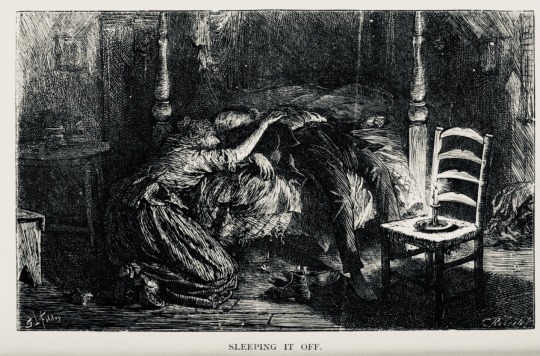

THE MYSTERY OF EDWIN DROOD by Charles Dickens. (London: Chapman & Hall, 1870). Illustrated by S.L. Fildes.

Designs in general shifted towards asymmetry during the 1870s, in opposition to the symmetical vogue of previous decades.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#victorian era#missing persons#cathedrals#charles dickens

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dive in Deeper: Allusion

hello, everyone! Long time no post! I haven’t forgotten about all of you! I’ve just been very busy!

What is an Allusion?

an allusion is a figure of speech that refers to a famous person, place, or historical event—either directly or through implication

are used as stylistic devices to help contextualize a story by referencing a well-known person, place, event, or another literary work

6 Different Types of Literary Allusions

Casual reference. An offhand allusion that is not integral to the plot.

Single reference. The viewer or reader is meant to infer the connection between the work at hand and the allusion.

Self-reference. A reference by the writer to another work of their own.

Corrective allusion. A comparison that is openly in opposition to the source material.

Apparent reference. An allusion that seems to recall a specific source, but challenges that source.

Multiple references or conflation. A variety of allusions that combine cultural traditions in a single work.

How Do You Use Allusion in Writing?

Character development. Using well-known figures as character inspiration can help to define characters and associate familiarity with the reader. For example, King Triton in The Little Mermaid bears resemblance to Poseidon, the god of the sea.

Context. An allusion to another work can delineate differences or similarities between the two. The 1999 film The Matrix draws parallels with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. The film’s protagonist, Neo, follows a character called the “White Rabbit Girl” to a mysterious underworld, much like Alice’s journey to Wonderland.

Exposition. Allusions can be used to help piece together thrillers or mysteries, offering readers clues that intimate other stories. In Charles Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood, allusions to Shakespeare’s Macbeth foreshadows the story’s plot and the motivations of its characters.

There you have it! If you found this useful, please like, comment and re-blog.

If you re-post on Instagram feel free to tag me at perpetualstories

Feel free to follow me on Tumblr for more writing and grammar tips and more!

#writing#writing advice#writing tips#original writing#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writersconnection#writersofig#writersofinstagram#writings

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

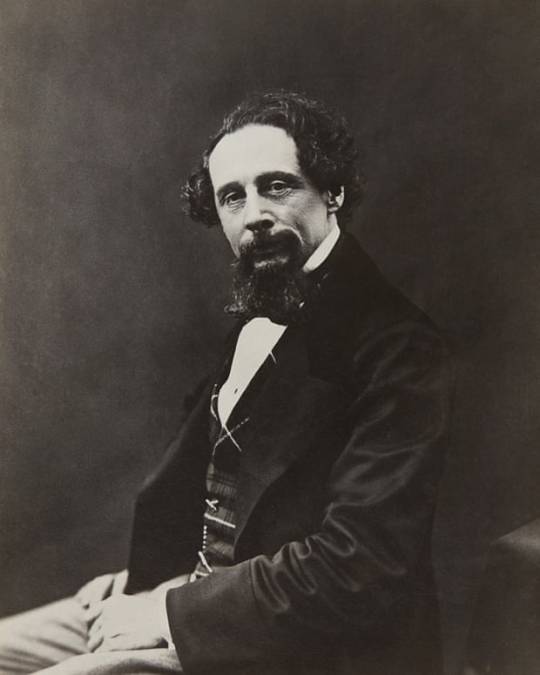

The Mystery of Charles Dickens by AN Wilson review – a great writer's dark side

Was Dickens’s fiction shaped by the nastiness he never consciously acknowledged? A sprightly retelling of a well-known narrative

Near the end of The Mystery of Charles Dickens, AN Wilson quotes at length from a letter written by Philip Larkin to his lover Monica Jones. The poet has just reread Great Expectations, and is reflecting on the novelist’s attention-seeking tricks: “Say what you like about Dickens as an entertainer, he cannot be considered a real writer at all; not a real novelist.” It is a version of a complaint that has been made many times about Dickens the mere “entertainer”. “His is the garish, gaslit, melodramatic barn … where the yokels gape.” Yet, at the end of all his sentences of critical deprecation, Larkin’s final reflex is equally familiar: “However, I much enjoyed G.E. & may try another soon.”

Those with high literary standards have often enjoyed Dickens against their better judgment. In The Mystery of Charles Dickens, Wilson sides with the gaping yokels. He confesses the he has read Dickens with “obsessive rapture” since his childhood, but had to overcome the presumption, later educated into him, that his writing was insufficiently deep or sophisticated. “The death of Paul Dombey is so schmaltzy that we simply refuse to be moved, but then, damn it, we read and the tears well down our cheeks.” For Wilson, Dickens is an irresistible performer. One chapter of his book is devoted to “The Mystery of the Public Readings”, in which Dickens drove himself to near collapse (and made huge amounts of money) by touring America as well as Britain to perform readings from his work. In 1869, he had a stroke on stage in Chester, but still refused to stop the readings, partly because of the money but mostly because he was addicted to the instant responsiveness of his audience.

The highlight of his show was Bill Sikes’s murder of Nancy from Oliver Twist, in which, Wilson thinks, the novelist released some demonic aspect of himself – some yen for sexual violence – on stage. Murderous villains such as the gleefully sadistic Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop, or the psychopathic John Jasper in The Mystery of Edwin Drood, were projections of his own cruelty. Wilson’s book is, you might say, bio-critical: “Dickens’s novels tell the story over and over again of his divided self,” he writes. The secrets of his life lie on the surface of his fiction. The dust jacket proclaims that the book goes “beyond standard narrative biography”. Which is to say that The Mystery of Charles Dickens does not reveal anything the previous biographers have not told us (indeed, it is conscientiously reliant on a small number of secondary sources). Instead, it shows, by a mixture of rational inference and I-feel-it-in-my-bones intuition, how the most powerful aspects of Dickens’s fiction drew on the most painful and secret aspects of his life.

The biggest secret of Dickens’s life, of course, was his clandestine relationship with Ellen (“Nelly”) Ternan, the young actor whom he first met when she performed at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester in The Frozen Deep, a play that he had written with his friend Wilkie Collins, and in which he himself was acting. She was 18; he was 45. For the next 13 years, Dickens paid for her to live in a series of discreetly located residences, where he would secretly visit her. The last of these was Windsor Lodge in Peckham, then a pleasant village outside London, with a railway station on the line from Dickens’s Kent home.

Each chapter of Wilson’s book is a different “Mystery”, the first being what happened to most of the £22 for which Dickens cashed a cheque on the day before his death. Dickens must have given it to Nelly for housekeeping. Which means that he must have made a quick trip to Peckham and that the “seizure” that killed him must have been induced by some hyper-energetic sex with her. Which means that hasty measures must have been taken to heave the dying novelist into a carriage to be driven back to his Kent home. “Exit Nelly, stage left.” (This enjoyable fiction, which has been hazarded by others before Wilson, is partly withdrawn near the end of the book.)

Next is “The Mystery of his Childhood”. Wilson is hardly the first to suggest that Dickens’s fiction was shaped by what he calls “the grotesquely sad galanty show of his childhood”. He briskly takes us through the story of the penury, the period in the debtors’ prison, the aborted education, the banishment, aged 10, to menial labour in Warren’s Blacking warehouse. There is less stress than usual on the improvidence of Dickens’s father, John Dickens (whose self-relishing orotundity at least inspired the matchless idiolect of Mr Micawber). Instead, Dickens blamed his mother. The ludicrous (Mrs Nickleby) or monstrous (Mrs Clennam) mothers in his novels bear the imprint of “the deepest needs of mother-hate”. Wilson asserts that “his flawed relationship with his mother is the defining feature, of the man and of his art”. Yet his privations made him a great novelist. The Blacking warehouse “saved Dickens the novelist, just as grammar school and Cambridge would have destroyed him”.

Then there is “The Mystery of the Cruel Marriage”. Nothing has more tainted Dickens’s reputation than his public repudiation (via an advertisement in the Times) of his wife, Kate, who had borne him 10 children and suffered all his demands for 22 years. Wilson’s house, he tells us, overlooks the back garden of 70 Gloucester Crescent, Camden Town, whence Catherine Dickens was exiled, with the company of only one of her children, Charley, their eldest son. The others were forbidden to see her. We have found out recently that Dickens tried to have her certified insane, so that she would be put in an asylum. Not only did he want to be free to pursue an affair with Nelly Ternan, he wanted somehow to declare that it was all his blameless wife’s fault. He was the wounded party.

But all the fury and resentment that he felt towards first his mother, and then his wife, inspired his greatest fiction, Wilson thinks. We should be grateful that he was so screwed up. Great Expectations, he believes, was a masterpiece of self-torment, formed from his own ruthlessness, his hunger for money and status, his family hatreds – all handed down to the novel’s narrator, Pip. “A helpful course of cognitive therapy, such as our contemporaries would have urged on a middle-aged man who had just visited such absolute mayhem on his wife and children” would have destroyed his creativity. Just as Pip owed his fortune to a violent criminal, Magwitch, its author owed his lucrative brilliance to “a secret, violent criminal”: himself. Or rather, the dark and nasty secret self that he never consciously acknowledged.

Wilson concedes all the contradictions and hypocrisies anatomised by John Carey in his brilliant, often openly exasperated study of Dickens, The Violent Effigy – but forgives him. Dickens had to contend with the “vast, smoky, cruel, boundlessly energetic, steel-hearted nineteenth century”, which made him variously cruel and sentimental. He was, after all, a nobody, who had grown up “with nuffink”. Alone among all great writers of the 19th century, he had “not merely looked over into the abyss. He had lived in it.” His lifelong insecurity was another creative asset.

If you are a Dickens aficionado, you will think that much of the book’s biographical narrative is well-known material, though here revisited in a sprightly manner. Yet its last, highly personal section suddenly shifts your sense of Wilson’s commitment to his subject. In his final chapter, he remembers first encountering episodes from Dickens at the age of eight or nine at his private school, which was “in effect a concentration camp run by sexual perverts”. The teacher who introduced him to Dickens was himself utterly sinister and Dickensian, the skill with which he impersonated Fagin and Squeers “all too convincing”. The shards of Dickens sustained his spirits among the privations and abuse visited on him by the paedophile headmaster and his monstrous wife, uninhibited sadists in Wilson’s vivid, detailed account. After this, nothing would convince him that Dickens should be condescended to as insufficiently “realistic”. And in returning him to the “abject terror and hopelessness” of childhood, but with that strange Dickensian stir of laughter (Fagin and Squeers, those comic turns), the novelist, hypocritical and self-deceiving as he might have been, has done him some matchless kindness.

© 2020 Guardian News

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caffeine Challenge #29

Posting a little early because I'm a morning writer and have been sitting on this all day. Thanks for the prompt, @caffeinewitchcraft !

*

Engine of Hope

The engine purring outside the window shouldn’t exist.

The drool-soaked pillow under my cheek let me know that I’d been dreaming - the deep, heavy sleep where I worked out the answers to impossible problems. I had ruined my favorite Star Wars pillow when I was eleven years old and dreamt exactly how a raven is like a writing desk. At sixteen, I was hospitalized for dehydration when I dreamt for two weeks straight to solve the mystery of Edwin Drood. At twenty-two, the doctors had thought I’d slipped into a coma before I awoke with the answer to Fermat’s last theorem.

Deep dreams were my blessing and my curse.

“Have you really done it, Dremmar?” A man’s deep baritone brought me out of the last stages of sleep. “Have you really saved the world?”

Dr. George Cavendish grinned at me from my bedside, his cheeks more wrinkles than skin around his mouth, but not his eyes.

“How long was I dreaming?” I struggled to sit up, but my body had never felt so heavy.

“Three months, two days, and one golden hour,” Cavendish replied, gesturing to a beefy nurse to help me navigate the IV needles, EKG lines, electric muscle stimulators, and catheter tubes. “That thing outside assembled itself out of thin air in the last fifty-seven minutes. EM readings have been in constant flux. Everything that runs on electricity for half a mile is dead, but that thing is purring like a kitten. How does it work? How can I make more?”

The naked greed of the mad venture capitalist flashed across Cavendish’s harmless-old-man face. It turned my blood to ice. What had I been thinking to partner with a man like this? How could I tell him that I’d dreamt the formula to forward-engineering the ultimate clean energy source: the power of human hope?

The Hope Engine that powered the levitating car outside the window hadn’t exactly materialized out of thin air, but it had built itself out of the intensity of my desire for it to exist. My deep dreams synchronized my neurons with the fundamental probability functions of the universe. These dreams allowed me to search through the countless possible outcomes that fanned out from each and every moment to find the extremely-low probability future that I wanted and pull that particular timeline to me. Or maybe I pushed my consciousness to that future. Did it really matter?

What mattered was that I’d dreamt a flying car with an engine that ran on pure hope - the ultimate perpetual motion machine. Entropy had no place under that sleek, red hood. The world could have endless power with no pollution. All we’d have to do is hope for it.

And pay George Cavendish for the privilege.

He gazed out the window with that look of bottomless greed. Men in hard hats were building a scaffold around my flying car while men in white coats made notes on clipboards, anxious to study it closer. The nurse gently disconnected me from the tubes that had kept me alive for thirteen weeks, while more men in white coats huddled under kerosene lamps to study the printouts of the brain activity of my deep dream.

Cavendish was no fool. He had three Ph.D.’s himself, with hundreds more on the payroll. With enough time, he would reverse-engineer the Hope Engine, patent it, and become the world’s exclusive purveyor of clean energy. He might even unlock the secret of my deep dreams and put them in a pill. What would a man like that do with that power? Would my blessing become the world’s curse?

I had created an engine that ran on hope. I knew exactly what I had to do with it.

Destroy it.

135 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your vocal love of Dickens the other day reminded me of taking a class on Dickens in 7th grade and reading Great Expectations. I loved that teacher and that class, so thanks for happy memories! It also made me remember the book "Drood," a fictionalized behind the scenes of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, wherein Dickens sort of hypnotizes this rival author into believing all kinds of bizarre supernatural conspiracy stuff, and it's great. Anyway, if you haven't read it, highly recommend.

Oh my god, that sounds right up my alley! I LOVE Dickens, and I LOVE the reimagining of stories (I took a course in college that was JUST reading the source material and then a transformative text, it was AMAZING, if I ever have the time to restart the book club I’d love that) so I’ll pick it up! I’m not reading as much right now, sadly, so my list has gotten long, but it’ll be on there!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clasping hands/ that forearm handshake thing seems to be theatre shorthand for "The script doesn't explicitly state this, but we're bros now."

Sources: The Mystery of Edwin Drood (2012), our current production of Hunchback.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks for tagging me, @thesheepthewolf !

The Game: answer the questions, create your own 11 questions, and tag 11 people.

1. What is the best book you’ve read so far this year? The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum (reread and currently two books into the series), and Yugioh by Kazuki Takahashi (first time reading and currently a little less than halfway through the series). I enjoy both of these series for similar reasons, for the lovable, endearing characters, and the zany, wacky adventures with some occasionally dark and twisted scenes to spice it up.

2. If you could ask any author (living or dead) one question, who would it be and what would you ask? I would ask Charles Dickens about what endings he had in mind for The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

3. Would you ever want to have a book of your own published? That would certainly be a fun and interesting experience, but all I’ve got are a bunch of half-baked ideas, not stories.

4. What do you do to get out of a reading slump? I don’t really get reading slumps. If a book is not working out for me, I just put it down and read something else. I use the Popsugar Reading Challenge if I need help picking out the next book to read, and if I’m behind on my Goodreads Book Challenge, I pick up a manga or a picture book.

5. How do you feel about book-to-screen adaptations in general? The two mediums rely on totally different ways of telling a story, so it’s pretty much impossible to completely and accurately translate a book to a film. So long as the adaptation is true to the spirit and ideas of the source material (like Lord of the Rings), or if it can stand on its own as a good movie without the book’s help (like Jurassic Park), it’s fine by me.

6. If there was a fire and you only had enough time to grab 5 books from your shelves, what would you take? The Neverending Story by Michael Ende, Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, Watership Down by Richard Adams, and Bambi by Felix Salten.

7. Do you listen to music while you read, and if so, how do you decide what to listen to? I like to listen to lofi hiphop or chill music while I read because it’s pleasant to listen to, but not too distracting. I just pick a random playlist on YouTube or Spotify.

8. How much of a role does a book cover play for you? Pretty covers certainly catch my attention, but I always do some research first before actually buying or checking out a book...unless it’s a pretty collector’s edition of a beloved classic, then I’m all like GIMME GIMME GIMME.

9. Do you have any “chicken soup books” (titles you return to when your feeling low or ill)? What are they? I like to read HP Lovecraft when I’m sad. I don’t know why.

10. What do you like to snack on while reading? I don’t usually snack on anything while I’m reading. I just find it distracting for some reason. I do like to drink tea while I’m reading, though.

11. If you could only (re)read the same book or series for the rest of your life, which one would you pick? I don’t think I could ever do that willingly, but if it was life or death I’d pick One Piece by Eiichiro Oda. The series is INSANELY long and still ongoing, so I’d probably be old as the hills or deceased by the time I got to the last volume...unless (it’s very likely) the series would continue long after I was dead, so I’d still be reading the series as a ghost.

My questions:

1. Think of a book or series that you read in the past. Has your opinion of that book or series changed since then or stayed the same?

2. Think of a character that you read about in the past. Has your opinion of them changed in retrospect, or stayed the same?

3. Do you listen to audiobooks? If so, when and/or where?

4. What was the first book that you read and enjoyed on your own?

5. Do you read comic books? Graphic novels? Manga? If so, what’s your favorite?

6. What was the last book you read that was originally written or published in a different language?

7. Are there any books you’ve read that have changed your perspective in a big way? A small way?

8. Do you like to read outdoors? If so, where?

9. Do you play videogames? If so, what console(s) do you have? Do you play on a PC?

10. Do you read ebooks? If so, what ereader do you have?

11. What do you think constitutes a “classic”?

I tag anybody who wants to try this, and also @godzilla-reads @thisblogislit-erature @tinynavajoreads @booktineus @blackcatno7 @lamia-zarzis7 @captainbooksnob @thebookishdragon @soggywarmpockets @pokebecher @novelknight

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Game:

Charles Dickens was an English novelist and social critic during the Victorian era.

At some point during 1868, he quite literally bumped into the Assassins Jacob Frye, Evie Frye, and Henry Green in Whitechapel. Henry told the Frye twins that Dickens was a valuable ally to have. He later welcomed Jacob and Evie as members of the "Ghost Club", and together they investigated local mysterious with allegedly paranormal causes.

At the first meeting of the club, the twins were tasked by Dickens to investigate the “demon”, Spring-Heeled Jack.

One night in the Lambeth district, there were a number of victims being assailed by an attacker said to have been killed by the murderer. The Frye twins found out, though, that the supposed demon was a cultist in disguise. They tracked down the impersonator through their workshop and eliminated the cult.

Dickens also pointed the Frye twins towards the cases of Enzio Capelli and James Jasper. Later, the Ghost Club met in a pub to toast to their success in debunking superstition.

In Real Life:

Charles John Huffam Dickens was the well-known and prolific British author of numerous works during the Victorian era that are now considered classics, such as “A Christmas Carol,” “Great Expectations,” and “A Tale of Two Cities.”

Dickens was born on February 7, 1812, in Portsmouth, England. He was the second of eight children to John and Elizabeth Dickens (née Barrow). The former was a navy clerk and the latter aspired to be a teacher and school director. Despite their best efforts, however, the Dickens family remained very poor.

In 1816, they moved to Chatham, Kent, where Charles and his siblings were free to roam the countryside and explore the old castle at Rochester. Charles, however, spent a lot of his time reading voraciously. In 1822, the Dickens family moved again, this time to Camden Town, a poor neighborhood in London, because John Dickens had been recalled to the Navy Pay Office headquarters. By then the family’s financial situation had grown dire, as John Dickens had a bad habit of living beyond the family’s means. Eventually, when Charles was twelve years old, John was sent to prison for debt in 1824.

After his father’s imprisonment, Charles Dickens was forced to leave school to work at a boot-blacking factory alongside the River Thames. At the rundown, rodent-ridden factory, Dickens earned six shillings a week labeling pots of “blacking,” which was a substance that was used to clean fireplaces. It was the best he could do to help support his family, now that their primary breadwinner was gone. Looking back on the experience, Dickens saw it as the moment he said goodbye to his youthful innocence, stating that he wondered “how [he] could be so easily cast away at such a young age.” He felt abandoned and betrayed by the adults who were supposed to take care of him. These sentiments would become a recurring theme in his writing later on.

Dickens was able to go back to school later on when John Dickens's paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him £450. John used that money to pay off his debts. When Charles was fifteen, though, he was taken out of school once again so that he could work as an office boy to contribute to his family’s income. As it turned out, this job became an early launching point for his writing career.

Within a year of being hired, Dickens began freelance reporting at the law courts of London. Just a few years later, he began to report for two major London newspapers. In 1833, he began submitting sketches to various magazines and newspapers under the pseudonym “Boz.” In 1836, his clippings were published in his first book, “Sketches by Boz.” Following Dickens’ success, he soon married a woman by the name of Catherine Hogarth. Together, the couple had ten children before they separated in 1858.

(Image source)

In the same year that “Sketches by Boz” was released, Dickens started publishing “The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.” His series of sketches, originally written as captions for artist Robert Seymour’s humorous sports-themed illustrations, took the form of monthly serial installments. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club was wildly popular with readers. In fact, Dickens’ sketches were even more popular than the illustrations they were meant to accompany.

Around this time, Dickens had also become publisher of a magazine called Bentley’s Miscellany, in which he started publishing his first novel, “Oliver Twist,” which tells the story of the life of an orphan growing up in the streets. The story was inspired by how Dickens felt as an impoverished child forced to get by on his wits and earn his keep. Dickens continued showcasing his story in the magazines he later edited, including “Household Words” and “All the Year Round,” the latter of which he founded. The novel was extremely well received in both England and America with many dedicated readers.

From 1838 to 1841, he published “The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby,” “The Old Curiosity Shop,” “Barnaby Rudge,” “American Notes for General Circulation,” and “The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit,” though none were as popular as “Oliver Twist.” Over the next several years, though, Dickens published more novels and stories, such as “A Christmas Carol” and “David Copperfield.”

In the 1850s, Dickens suffered from both the loss of one of his daughters and his father. He also separated from his wife at this time, slandering her publically, and formed a relationship with the young actress Ellen "Nelly" Ternan, though sources differ on whether he started seeing Ternan before or after he and his wife split apart.

(Image source)

In 1865, Dickens was in a train accident and never fully recovered. Despite his fragile condition, he continued to tour around England and America until about 1870. On June 9th, 1870, at the age of fifty-eight, Dickens had a stroke and died at Gad’s Hill Place, his country home in Kent, England. He was buried in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey. At the time of Dickens’ death, his final novel, “The Mystery of Edwin Drood,” was unfinished.

Sources:

https://books.google.com/books?id=v6gmAQAAMAAJ&q=isbn:9780198662136&dq=isbn:9780198662136&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjJ0semxrjTAhVIHGMKHao1B5YQ6AEIJTAA

http://www.biography.com/people/charles-dickens-9274087

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/dickens_charles.shtml

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Francis Loftus Sullivan (6 January 1903 – 19 November 1956) was an English film and stage actor.

Francis Loftus Sullivan[1] attended Stonyhurst, the Jesuit public school in Lancashire, England, whose alumni include Charles Laughton and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

A heavily built man with a striking double-chin and a deep voice, Sullivan made his acting debut at the Old Vic at age 18 in Shakespeare’s Richard III. He had considerable theatrical experience before he appeared in his first film in 1932, The Missing Rembrandt, as a German villain opposite Arthur Wontner as Sherlock Holmes.[2]

Among his film roles are Mr. Bumble in Oliver Twist (1948) and Phil Nosseross in the film noir Night and the City (1950). Sullivan also played the part of Jaggers in two versions of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations - in 1934 and 1946. He appeared in a fourth Dickens film, the 1935 Universal Pictures version of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, in which he played Crisparkle.

He was featured in The Citadel (1938), starring Robert Donat, and a decade later, he played the role of Pierre Cauchon in the technicolor version of Joan of Arc (1948), starring Ingrid Bergman. In 1938 he starred in a revival of the Stokes brothers’ play Oscar Wilde at London’s Arts Theatre. He played the Attorney General prosecuting the case defended by Robert Donat as barrister Sir Robert Morton, in the first film version of The Winslow Boy (1948).

Sullivan also acted in light comedies, including My Favorite Spy (1951), starring Bob Hope and Hedy Lamarr, in which he played an enemy agent, and the comedy Fiddlers Three (1944), portraying Nero. He also played the role of Pothinus in the film version of George Bernard Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra (1945). The film was directed by Gabriel Pascal, and was the last film personally supervised by Shaw himself. Sullivan reprised the role in a stage revival of the play.

Sullivan, who eventually became a naturalized US citizen, won a Tony Award in 1955 for the Agatha Christie play Witness for the Prosecution. Earlier, he had played Hercule Poirot at London’s Embassy Theatre in the Christie play, Black Coffee (1930).[citation needed]

He died of a heart attack, aged 53 (some sources claim he died from an unspecified “lung ailment”).[citation needed]

Francis L. Sullivan was born on January 6, 1903 in London, England as Francis Loftus Sullivan. He was an actor, known for Great Expectations (1946), Oliver Twist (1948) and Joan of Arc (1948). He died on November 19, 1956 in New York City, New York, USA. IMDb

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think about musicals based on books? And should a person who wishes to be in one such musical have read the book before auditioning?

Hmm…musical theater and I don’t really get on–most shows tend to be frivolous, simplistic things that sacrifice story for the sake of a sudden catchy tune. And this goes double for adaptions of books, to my great dismay. The Phantom of the Opera? Cheap, discordant melodrama that either completely jettisons or unrecognizably alters the original characters. The Wizard of Oz? Undigestable pap that truncates the plot beyond all recognition. And the adaptations of Peter Pan and Jane Eyre I was forced to watch through bootleg video (why on earth those things are considered socially acceptable I will never know) nearly made me physically ill. However, lest one think I am completely opposed to the idea, there are a few that I do think are admirable. The Secret Garden is a charming little thing with some good music, Les Miserables is as close to the reading experience one can get without slogging through Hugo’s numerous tangents, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood is a rather creative approach to the unfinished nature of the novella. One of Professor Trent’s students has recommended me Doctor Zhivago and Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812 (based on a very small subplot from War and Peace), both of which show some promise.

As for the second question, I should think some familiarity with the source material is a must. No matter how faithful the adaptation is, there will always be subtleties of story and character left out of the script, mostly due to scriptwriters believing the common playgoing public is too dense to pick up on them (they are often right, unfortunately, but that is beside the point). If an actor has done their homework and filled in these essential gaps, it lends the performance some integrity it might otherwise lack. So yes, I would advise reading the book at least once before auditioning.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Season Announcement Wednesday

What gives me joy about highlighting this week’s company is that even pre-COVID-19 regulations, this group of artists made audience education and variety in entertainment a priority. In addition to some wonderful productions, their community events, pre-show activities, and education program were staples of their mission as a theatre group with love for serving their community. Their work continues in an adapted form while SIP is a reality. So, I am quite pleased to highlight the 2020-2021 season at Town Hall Theatre Company!

Shows/Dates: The Grown-Up (September 26th - October 17th); Coney Island Christmas (December 5th - 20th); The Trip to Bountiful (February 27th, 2021 - March 20th, 2021); Peter and the Starcatcher (May 29th - June 19th)

Venue/Address: Town Hall Theatre @ 3535 School St., Lafayette 94549

Website: www.townhalltheatre.com

Facebook: “Like” them at-Town Hall Theatre

Twitter: “Follow” them at- @TownHallTheatre

Description: Town Hall Theatre Company has been a source for excellent theatre in the East Bay area. I have enjoyed their productions of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Smokey Joe’s Cafe, An Ideal Husband, Sense and Sensibility, The Song of the Nightingale, and The Revolutionists, among others. In addition to their main stage season, Town Hall provides literary events, writing events, lobby events, and all sorts of interactive activities for audiences of all ages. Head to their website to check out the details and make your plans to support this company big time once we can congregate in their house again!

#townhalltheatrecompany#thegrownup#coneyislandchristmas#thetriptobountiful#peterandthestarcatcher#musical#theatre#musicaltheatre#lafayette#bayarea#bayareatheatre#seasonannouncementwednesday

0 notes

Text

#Howard #McGillin #explorepage #eyeliner #eyes #follow #haircolors #makeupjunkie #makeuplooks #nature #polishgirl #studio

Howard McGillin is a Tony-nominated action, screen and television actor, probably ideal known for his role of John Jasper in Drood and for currently being the world’s longest running Phantom in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera. He will star in the upcoming musical Rebecca, which will open on Broadway during the 2012–2013 season.

Other featured and leading roles on Broadway before long followed. Often regarded a “tall, dark and handsome” leading man, McGillin originated the role of John Jasper in The Mystery of Edwin Drood at the Imperial Theatre; for his performance he was nominated for a 1986 Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical. He earned a second Tony nomination in 1988 for his portrayal of Billy Crocker in the Broadway revival of Cole Porter’s Anything Goes. McGillin starred in the award-winning West End revival of Mack & Mabel and sings on the cast album recording. He way too received substantial praise as Molina in the Kander and Ebb musical Kiss of the Spider Woman although he was the 2nd actor to play the role, critics praised his perfomance stating that he and co-star Brian Stokes Mitchell were good enough to incorporate opened in the show.

Name Howard McGillin Height Naionality American Day of Birth 5-November-1953 Place of Birth Los Angeles, California, U.S. Famous for Acting

The post Howard McGillin Biography Photographs Wallpapers appeared first on Beautiful Women.

source http://topbeautifulwomen.com/howard-mcgillin-biography-photographs-wallpapers/

0 notes

Text

We Triumph Now, God Only Knows How

We've blocked our zombies and zombie hunters, and we've run the two acts separately. Next week we move into the theatre, and start running the whole show. The vocal music is sounding amazing, in part because we're spending a lot more time than usual reviewing music in blocking rehearsals, which makes the actors so much more comfortable. We're now at that point now where they have to put down their scores, and that moment terrifies some of them. The score is learned, the show has been staged, and now we put meat on the bones. I realized a number of years ago, that comic book art is a really good metaphor for our creation process. I think that's because comic book art and musical theatre are both (usually) very collaborative work, which ultimately needs to look like it came from one artist. We block a show relatively fast, and we don't run scenes a lot until all the pieces are in place. I think about that part of our process as my pencil drawing. I define the work ahead and lay down the ground rules. Then together, the actors and I "ink in" my pencil drawing, we add clarity and depth and focus, and we make a lot of choices. Then I sort of stand back and let the actors "color" their performance. I'm a director who doesn't want to give an actor too much direction up front. I once saw an interview with Hal Prince, where he said that the job of a director is to put everybody on the same road, make sure they all stay on that road and don't stray onto some other road, let them do the work, and then edit and polish that work to create a coherent whole. I love that idea. I firmly believe that our show will be better and richer if the actors actively collaborate with me, actively create our show as much (or more) than I do. It won't be nearly as cool if all the ideas come from me. That's unnerving for some actors, who'd rather I ink and color their performances. But most actors love the freedom. Then again, freedom isn't free. With great power comes great responsibility. But The Zombies of Penzance is a crazy, meta, artistic tightrope, so that freedom is a little scarier than usual. I've asked the actors, now that they're comfortable with the music, to really focus on the text, to read it out loud (a good idea with any lyric), to make sure they totally understand everything they're singing (that's not always easy with G&S, or G&S parodies), to think about all the lyrics like they're dialogue, to think about why they repeat things... But also, we all have to keep in mind that Gilbert & Sullivan operettas are almost entirely about showing how ridiculous we all are (yes, even zombies), and part of that ridiculousness is how Very Seriously the characters take themselves and each other. It's always Very High Stakes, literally life or death -- or undeath -- in our story. But also...

We always have to keep one eye on the central meta joke of the show -- that this is the most wrong-headed storytelling form possible for telling this particular story. To be honest, that was the biggest appeal of the project for me initially. So we have to underline and revel in that wrongness, in this wild mismatch between our story and our storytelling. Remember, The Pirates of Penzance was already making fun of the conventions of opera, like almost all the G&S shows do. But with The Zombies of Penzance, we add another meta-layer to it. Here, we're telling a horror story in the language of English light opera. So inside the story, everything is terrifying and insane and literally life or death; but when the actors step outside of the story to directly tell the audience things (which happens a ton!), they're in a quirky, ever so polite English light opera. And yet they're still in character and period the whole time. The actors have to find that dual reality and realize that if they're comfortable with it, the audience will accept it. I guess our meta-meta musical is closer to The Mystery of Edwin Drood than any other musical I can think of. It's interesting that both Zombies and Drood are American shows based on British sources and British theatre forms. What makes Gilbert & Sullivan shows work is getting the audience to accept the barely logical reality of the story, to accept the story's usually ridiculous rules and conventions, to care about the characters, no matter how crazy they are. In fact, it's often the most ridiculous G&S characters that we bond with most. The way all that happens onstage is for the actors to live completely and honestly within that crazy reality, no matter how crazy it gets, no matter how tenuous its logic gets. It's just like doing Little Shop of Horrors or Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson -- the actors have to make peace with the odd, unconventional rules these shows invent for themselves, and then audiences will do the same. Actors who don't do musicals often think musical theatre acting is somehow "lesser" -- less serious, less skillful, less honest -- than acting in non-musical plays. The opposite is true. The kind of acting most musicals require (particularly post-1964) is much more difficult, much more complex, and requires more and different training. That's why so many famous actors have sucked in musicals. Our actors in The Zombies of Penzance have a much harder job to do than people realize. It is a truism of theatre (and I assume other forms) that audiences will follow strong, confident storytelling wherever it takes them. We New Liners have seen that proven over and over again throughout our history, with shows like The Wild Party, Love Kills, Forbidden Planet, Floyd Collins, Passing Strange, American Idiot, Bat Boy, Urinetown, Sweet Smell of Success. But audiences will not follow tentative or clueless storytelling; they will disconnect.

We now have two and half weeks to just run our show at every rehearsal, tweak it, polish it, but most of all, to let the actors collectively find that dual reality, the style and tone, and construct the magic "clockwork" that pulls everything together into a unified whole. Our intrepid music director Nicolas Valdez and our truly brilliant cast have shaped such a gorgeous musical sound for our show. Now the actors have to put down their scores, so they can explore and invest in these wacky characters and this wild, barely logical story. The sooner they put down the music and the more time they give themselves to play in this world, the richer our show will be. This is the part where I sit back and let the actors explore. It's the most exciting part. The adventure continues... Long Live the Musical! Scott from The Bad Boy of Musical Theatre http://newlinetheatre.blogspot.com/2018/09/we-triumph-now-god-only-knows-how.html

0 notes