#sort of? it's mostly critical of the writing post death rather than the character herself

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Saw someone claim that canon Stephanie Brown has the character arc / development that "fanon [redacted]" has and buddy I hate to break it to you, but Preboot era Stephanie has the character development of a flat tire.

Stephanie starts out as a decently rounded supporting character who acts as a foil & peer to first Tim and then Cass. She's abrasive, pushy, and impulsive, which works for the narrative role she's in. She has some interesting moments of minor growth and glimpses of potential for more that unfortunately don't really go anywhere.

Then she gets screwed over by editorial's desire for grimdark edginess, dies, turns out not to be dead, and comes back having learned absolutely nothing from her mistakes (including, frankly, the mistake of thinking Bruce Wayne knows what he's doing).

Her following solo title insults other women characters to prop her up, acts like her past mistakes which got people killed are just a minor whoopsie that doesn't need to be addressed, and by the end of the run she's in the exact same narrative place she started.

I suspect if Stephanie hadn't died, or even if she'd died in a different way, she'd have continued to be a decently rounded character. Maybe she wouldn't have learned from her mistakes, but she'd have been allowed to be wrong. Maybe some of those glimpses of potential growth would have finally been followed up!

As-is, it feels like once she came back, DC didn't want to let the narrative criticize her at all, in case they be accused of victim blaming.

Which makes for a very flat character.

#Batgirl 2009 critical#Stephanie Brown Critical#sort of? it's mostly critical of the writing post death rather than the character herself#but I don't think there's a tag for that and I want people to be able to filter out the tag so...#Steph is a character that had a lot of potential and then it just#evaporated#Batgirl 2009 is a great example of judging a work's level of feminism#not by how it treats the lead but by the girls and women in the supporting cast#though actually also how it visually treated Steph too#was not good#see purple dress post for example#Stephanie Brown#DC#Batfam#comics meta#character she was being compared to has been redacted because it's frankly beside the point and a distraction

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books read in January

I am keeping this as a little record for myself, as I already keep a list (my best new year’s resolution - begun Jan 2018) but don’t record my thoughts

General thoughts on this - I read a lot this month but it played into my worst tendencies to read very very fast and not reflect, something I’m particularly prone too with modern fiction. I just, so to speak, swallow it without thinking. First 5 or so entries apart, I did quite well in my usually miserably failed attempt to have my reading be at least half books by women.

1. John le Carré - Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974): I liked this a lot! I sort of lost track of the Cold War and shall we say ethics-concerned parts of it and ended up reading a fair bit of it as an English comedy of manners - but I absolutely love all the bizarre rules about what is in bad taste (are these real? Did le Carré make them up?).

2. John le Carré - The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963): I liked this a lot less. It seemed at the same time wilfully opaque and entirely predictable. Have been thinking a lot about genre fiction - I love westerns and noir, so wonder if for me British genre fiction doesn’t quite scratch the same itch.

3. David Lodge - Ginger You’re Barmy (1962): This was fine. I don’t have much to say about it - I was interested in reading about National Service and a bit bogged down in a history of it so read a novel. As with most comic novels, it was perfectly readable but not very funny.

4. Dan Simmons - Song of Kali (1985): His first novel. This is quite enjoyable just for the amount of Grand Guignol gore, and also because I like to imagine it caused the Calcutta tourist board some consternation. Wildly structurally flawed, however. Best/worst quote: ‘Hearing Amrita speak was like being stroked by a firm but well-oiled palm.’ Continues in that vein.

5. Richard Vinen - National Service: A Generation in Uniform (2014): If you are interested in National Service, this is a good overview! If not, not.

6. Sarah Moss - Ghost Wall (2018): I absolutely loved this. About a camping trip trying to recreate Iron Age Britain. Just, very upsetting but so so good - a horror story where the horror is male violence and abuse within the (un)natural family unit.

7. Kate Grenville - A Room Made of Leaves (2020): Excellent idea, but not amazing execution - the style is kind of bland in that ‘ironed out in MFA workshops’ way (I have no idea if she did an MFA but that’s what it felt like). Rewriting the story of early Australian colonisation through the POV of John Macarthur’s wife Elizabeth.

8. Ruth Goodman - How to Be a Victorian (2013): I mostly read this for Terror fic reasons, if I’m honest. I skimmed a lot of it but she has a charming authorial voice and I really like that she covers the beginning of the period, not just post-1870.

9. Gary Shteyngart - Super Sad True Love Story (2010): I read this on a recommendation from Ms Poose after I asked for good fiction mostly concerned with the internet, and I thought it was excellent - it’s very exaggerated/non-realistic and that heightening of incident and affect works so well.

10. Brenda Wineapple - The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation (2019): What a great book. I had to keep putting it down because reading about Reconstruction always makes me so sad and frustrated with what might have been - the lost dream of a better world.

11. Halle Butler - The New Me (2019): Reading this while single, starting antidepressants and stuck in an office job that bores me to death but is too stable/undemanding to complain about maybe wasn’t a great decision, for me, emotionally.

12. Halle Butler - Jillian (2015): Ditto.

13. Ottessa Moshfegh - Death in Her Hands (2020): Very disappointed by this. I don’t really like meta-fiction unless it’s really something special and this wasn’t. Also, I’m stupid and really bad at reading, like, postmodern allegorical fiction I just never get it.

14. Andrea Lawlor - Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl (2017): This was really really hot! I will admit I don’t think the reflections on gender, homophobia, AIDS etc are very deep or as revealing as some reviews made out, but I also don’t think they’re supposed to be? It’s a lot of fun and all of the characters in it are so precisely, fondly but meanly sketched.

15. Catherine Lacey - The Answers (2017): This was fine! Readable, enjoyable, but honestly it has not stuck with me. There are only so many sad girl dystopias you can read and I think I overdid it with them this month.

16. Hilary Mantel - Wolf Hall (2010, reread): Was supposed to read the first 55 pages of this for my two-person book club, but I completely lack self-restraint so reread the whole thing in four days. Like, I love it I don’t really know what else to say. I was posing for years that ‘Oh, Mantel’s earlier novels are better, they’re such an interesting development of Muriel Spark and the problem of evil and farce’ blah blah blah but nope, this is great.

17. Oisin Fagan - Hostages (2016): Book of short stories that I disliked intensely, which disappointed me because I tore through Nobber in horrified fascination (his novel set in Ireland during the Black Death - which I really cannot recommend enough. It’s so intensely horrible but, like Mantel although in a completely different style/method, he has the trick of not taking the past on modern terms). A lot of this is sci-fi dystopia short stories which just aren’t... very good or well-sustained. BUT I did appreciate it because it is absolutely the opposite of pleasant, competently-written but forgettable MFA fiction.

18. Muriel Spark - Loitering with Intent (1981): Probably my least favourite Spark so far, but still good. I think the Ealing Comedy-esque elements of her style are most evident and most dated here. It just doesn’t have the same sentence-by-sentence sting as most of her work, and again I don’t like meta-fiction.

19. Hilary Mantel - Bring up the Bodies (2012, reread): Having (re)read all of these in about 3 months, I think this is probably my favourite of the three. I just love the way a whole world, whole centuries and centuries of history and society spiral out from every paragraph. And just stylistically, how perfect - every sentence is a cracker. I’m just perpetually in awe of Mantel as a prose stylist (although I dislike that everyone seems to write in the present tense now and blame her for it).

20. Muriel Spark - The Girls of Slender Means (1963, reread): (TW weight talk etc ) As always, Hilary Mantel sets me off on a Muriel Spark spree. I’ve read this too many times to say much about it other than that the denouement always makes me go... my hips definitely wouldn’t fit through that window. Maybe I should lose weight in case I have to crawl out of a bathroom window due to a fire caused by an unexploded bomb from WW2???? Which is a wild throwback to my mentality as a 16 year old.

21. China Mieville - Perdido Street Station (2000, reread): What a lot of fun. I know we don’t do steampunk anymore BUT I do like that he got in the whole economic and justice system of the early British Industrial Revolution and not just like steam engines. God, maybe I should read more sci-fi. Maybe I should reread the rest of this trilogy but that’s like 2000 pages. Maybe I should reread the City and the City because at least that’s short and ties exactly into my Disco Elysium obsession (the mod I downloaded to unlock all dialogue keeps breaking the game though. Is there a script online???)

22. Stephen King - Carrie (1974): I have a confession to make: I was supposed to teach this to one of my tutees and then just never read it, but to be honest we’re still doing basic reading comprehension anyway. That sounds mean but she’s very sweet and I love teaching her because she gets perceptibly less intimidated/critical of herself every lesson. ANYWAY I read half of this in the bath having just finished my period, which I think was perfect. It’s fun! Stephen King is fun! I don’t have anything deeper to say.

23. Hilary Mantel - Every Day is Mother’s Day (1985): You can def tell this is a first novel because it doesn’t quite crackle with the same demonic energy as like, An Experiment in Love or Beyond Black, but all the recurring themes are there. If it were by anyone else I’d be like good novel! But it’s not as good as her other novels.

24. Dominique Fortier - On the Proper Usage of Stars (2010): This was... perfectly competent. Kind of dull? It made me think of what I appreciate about Dan Simmons which is how viscerally unpleasant he makes being in the Navy seem generally, and man-hauling with scurvy specifically. This had the same problem with some other FE fiction which is that they’re mostly not willing to go wild and invent enough so the whole thing is kind of diffuse and under-characterised. Although I hated the invented plucky Victorian orphan who’s great at magnetism and taxonomy and read all ONE THOUSAND BOOKS or whatever on the ships before they got thawed out at Beechey (and then the plotline just went nowhere because they immediately all died???) I had to skim all his bits in irritation. I liked the books more than this makes it sound I was just like Mr Tuesday I hope you fall down a crevasse sooner rather than later.

25. Muriel Spark - The Abbess of Crewe (1974): Transposing Watergate to an English convent is quite funny, although it took me an embarrassingly long time to realise that’s what she was doing even though I lit read a book covering Watergate in detail in December. Muriel Spark is just so, so stylish I’m always consumed with envy. I think a lot of her books don’t quite hang together as books but sentence by sentence... they’re exquisite and incomparable.

Overall thoughts: This month was very indulgent since I basically just inhaled a lot of not challenging fiction. I need to enjoy myself less, so next month we’re finishing a biography of Napoleon, reading the Woman in White and finishing the Lesser Bohemians which currently I’m struggling with since it’s like nearly as impenetrable Joyce c. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man but, so far... well I hesitate to say bad since I think once I get into I’ll be into it but. Bad.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your conversation about Sam Manson. I was talking to Imekitty about this, but I’ve noticed a few things that (sort of) make Sam’s relationship with her parents seem more like teen-drama than actual hardship. If you look closely, she’s got a lot in common with them: outspoken political-activism, possible shared-interest in vintage clothes, and no shame in saying they don’t like certain people. Also, after the Fentons, they were the first to volunteer to use the Ecto-Skeleton, risks and all.

(In reference to this post.)

It’s been a little while since I rewatched DP so I’m not well-placed to do a detail-analysis implication-breakdown right now, but yeah - that fits with the overall impression I remember getting. To me they came across as being sort of old fashioned set-in-their-ways conservative and snooty, and maybe a bit too Pleasantville - but more often in the way of parents who do genuinely want good things for her and to be able to be proud of her despite not really understanding her interests, choices or friends and being very bad at expressing it. Plus she seems to have her grandmother fully in her corner a lot of the time.

I really wish that the writers had committed to one or the other; either making it clear that Sam’s martyr/ persecution complex is mostly just regular self-inflicted teen-drama BS and giving her an arc addressing it, OR fleshing out the idea that she faces a lot of judgement/ pressure/ control/ nonacceptance in her home life and that her negative traits are a bi-product of defensive/ coping mechanisms resulting from that strained dynamic, rather treating things with Roger Rabbit Rules.

(Which isn’t to say that a person can’t have similar interests/ personality traits to, and positive interactions with, their parents while still having a strained, broken or even abusive relationship with them on a deeper level, but the show never really goes hard enough in either direction to make it work.)

As mentioned the last post, this is kind of a consistent pattern across DP - the writers tend go with the low-effort first answer for whatever is Funny or Awesome or Convenient in the moment rather than putting in the work to find a solution that’s consistent with the characterisation, themes and world-lore overall. There’s enough internal contradiction in the show that I don’t think it’s actually possible to take every canon detail as canon without fundamentally breaking things. And in some ways that’s kind of cool; it makes the series more open to interpretation, and trying to distinguish authorial intent from authorial incompetence and come up with theories that account for as many pieces of canon as possible is really satisfying. But, you know, it’s also kind of bad writing in general.

I think the thing that bothers me about Sam’s characterisation in particular is that - where it tends to be more obviously out-of-character when it shows up in other places - there’s a pattern to the inconsistency with how the writers handle Sam:

Throughout the series there’s a double standard in how Sam sees herself/ seems to expects others to act, compared to her own behaviour:

Despite being pro-pacifism she’s okay with smacking Tucker and encouraging Danny to destroy the trucks she doesn’t like

Sam values self-expression and is a feminist, but derides other girls for wanting to express themselves in a conventionally feminine way

Sam doesn’t like being forced to conform to others’ values but is okay with forcing others to conform to hers

Despite being anti-consumerist she shows very little discomfort at, or awareness of, her lavish home life and material belongings

She encourages Danny to take the moral high ground towards his bullies but has no problem antagonising and getting into petty verbal spats with Paulina herself

Sam stalks Danny and his love interest out of jealousy/ protectiveness but threatens to end their friendship when he does the same

In Mystery Meat, when Danny tries to express his discomfort/ anxiety, Sam hijacks the conversation to complain about her own parents instead of listening.

In One of a Kind Sam photographs Danny and Tucker hugging in their sleep, without their knowledge, with the stated intent of putting it in the yearbook, then uses it to blackmail them into silence.

Side note: this joke is also tacky on a meta-level because it boils down to “male intimacy ha ha toxic masculinity no homo amiright?“ Would have been nice if show didn’t use low-key sexist humour as much as it did.

Instead of expressing that she’s hurt by Danny’s “pretty girls” comment in Parental Bonding, Sam retaliates by pushing him to ask Paulina out - a move she knows will most likely result in him getting publicly shut down and humiliated.

Then, after getting the result she wanted, she comes over to gloat and insults Paulina, rather than dropping it now that her point’s been made, which is what ultimately sets off the episode’s subplot.

In Memory Blank Sam permanently physically alters Phantom’s appearance to better suit her tastes while he’s not in a position to understand or give informed consent, then lies when Danny notices and asks about it later.

To be clear this definitely isn’t the be-all-and-end-all of her character and it’s not there 100% of the time - there are plenty of moments when she is loyal and generous and helpful and sincerely kind and where her stubbornness comes in handy. But it’s the aggregate pattern of all these small instances that drives a crack through the foundation of her character integrity; producing this insidious undercurrent alternate-reading of Sam as someone who, at a deep level, just doesn’t respect or recognise that the emotional needs, pains, opinions, autonomy and boundaries of others are as real and valid as her own, and who responds to criticism with passive-aggressive hostility.

Again, I think that’s why people are so quick to point out that line from Phantom Planet, even though we all know the episode was a complete mess. None of the examples above are particularly bad in isolation - you can’t really point at any one of them and say “oh no, bad girl” without sounding like you’re making a mountain out of molehill and irrationally hating on her just to hate on her. It’s an uncomfortable slowburn pattern of subtle micro-transgressions that accumulates across the series - a “you might not notice it but your brain did”. And it makes sense that it would be the worst-written episode that amplifies and brings that regular bad-writing undercurrent close enough to the surface for people to consciously recognise and use it to articulate those frustrations.

To wit: Not because it’s most telling of her character but because it’s most telling of the specific bad writing that regularly hurts her character.

And again, from a storytelling point of view, it’s okay for Sam to have flaws. She’s a teenager! She’s learning. She’s allowed to be egocentric and self-important and do things that aren’t the best at times. It’s okay if these are her character weaknesses and a source of conflict with the rest of the cast. But again, for that to be satisfying something really should have come of it. It would have been nice if the writers were willing to have any self-awareness about these flaws being flaws that a person should recognise and grow past in order to have healthy relationships with others. But they didn’t - because it’s easier to keep her as she is - to the point that they’ll actively bend the narrative to roll back or skip over moments that would have necessitated that growth. So, even though they call attention to her flaws, the writers end up rewarding and enabling them instead of letting her learn.

And again, this isn’t meant to hate on Sam. Hanlon’s Razor in full effect: it’s clearly a result of authorial/editorial incompetence rather than deliberate malice. I know this isn’t the intended interpretation.

My preferred reading of Sam Manson is that she’s a Rosa Hubermann/ Hermione Granger/ YJS1 Artemis Crock-type character. Someone who’s passionate and forceful and maybe a bit abrasive and hard to love at a glance, but whose core nature is compassionate and sincerely kind and loyal-to-the-death for the people they value. I wish I could 100% like her without caveats; to be able to say that even if I don’t agree with her flaws I can at least understand that they’re a valid product of the life she lives, that they make her who she is and that she’s trying her best to be a good person who will get better despite them.

But I can’t because the writers don’t give her that. They’re always prioritising other things over the integrity of her character. They don’t give her background enough time and context to make her negative traits feel resonant with it (because that would take time away from the Wicked Cool Radical Ghost-Fighting Superhero Action™) and the framing and plotting doesn’t give her chances to recognise or grow past them (because that would mean character development and those negative traits are an easy source of cheap conflict). The writers just don’t seem to care all that much about Sam - her actual character, who she is, how she came to be that way, what she wants or how her negative traits would actually play against Danny and the others.

And that sucks. Because she has a lot of potential to be a well-rounded and great character. I’ve seen plenty of fics that seize that potential and roll with those gaps and the result is very good. I wish I could like her canon depiction without feeling like I have to actively ignore a bunch of latent behavioural red flags as the price of entry.

She deserved better.

#Danny Phantom#Sam Manson#Character Writing#Character Analysis#I'm also going to cop to the fact that this part of Sam gets to me personally#because it mimics some of my experiences with emotionally abusive relatives#feeling really uneasy and uncomfortable and upset but not being able to articulate what they're doing that makes you feel that way#and wondering if maybe it's your fault and you're just reading into things too much and you're bad for not defending them#until they do something really egregious and suddenly it's like 'oh' 'OH' 'OH SH*T THAT'S NOT OKAY'#And then you look back and see all the little red flags and from then on you can never un-see them#One of the reasons I only like fanon!AmethystOcean is I can see how badly things are likely to go when Danny's flaws meet these problems#Danny's canon flaws are ones that make him particularly susceptible to emotional abuse#and they accidentally wrote canon!Sam with a lot of latent proto-abusive red flags#they both need character development to work as a couple#but this is Danny Phantom and I guess we're chumps from expecting that#anonymous#3WD answers

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jet Wolf Summarizes Act 43, pt2

The manga and I kind of hate each other. This is unfortunate, but still, I’m determined to come out of this with something. Rather than spend energy on a liveblog that’s increasingly negative, I’m reading each manga act (mostly) silently, and then writing up summaries at the end. I won’t pull my punches. There’s going to be criticism and snark about the manga, either wholesale or in details. If that isn’t a thing you feel like reading, please skip this post!

[READ PART ONE HERE]

So for exactly no reason whatsoever, Rei, Ami, and Mako are wistfully lamenting the absence of the Outer Senshi and the many, many, many times they provided succor to their adoring young counterparts.

Minako says, wondering how much of that vodka she’s gone through. As it turns out, Minako’s hiding a deeper secret. For reasons unknown, she’s lost the ability to transform.

Later, she confesses this to Artemis -- and Luna, and Tiny Kitten who happen to be the room. Minako would, naturally, be completely blasé about sharing deeply upsetting and personal information with them, so this makes perfect sense. Artemis gives Minako a pep talk, beginning with his confidence that Minako has the power inside of her and she can totally do this, and finishing with one of my favourite panels so far.

If you were following my posts earlier today, you know where this is going. We hurtle toward it, unable to alter the course of our destiny, ineffective passengers strapped in our seats and riding the bullet train to hell. It comes.

IT COMES

But I’m going to skip this for a moment. Before I loose my shit entirely, I want to talk about what COULD have been good about this issue. It brings up such an interesting idea, and I would have dearly loved for the manga to have done absolutely any of the work necessary to set this up (see also, This Summary Part One), or follow it through.

What’s blocking Minako from being able to transform isn’t (I’m assuming, this is sort of a two-parter) anything the Dead Moon are doing, it isn’t some fiendish enemy plot. It’s Minako’s own feelings of inadequacy because her friends and teammates won’t shut the fuck up about how awesome and inspiring the Outers are. And, by implication, how unnecessary SHE is.

I have no confidence whatsoever that the manga is going to follow through on this, BUT. I love so much this as a problem Minako has to overcome. She’s finally maybe coming to terms with her own fame and notoriety fading before Usagi, she’s enjoying the benefits of being part of a team rather than going solo. Only there’s this hole in Minako that she’s always trying to fill with the attention and adoration of others. It’s why she wants to be famous, why she wants to be a pop idol or an actress. And in her “real” job, it’s her girls that fill that need. The way they turn to her for confidence and strength, for support and strategy.

Except the fucking Outers are doing all that now, AND THEY AREN’T EVEN HERE.

Minako feels she’s losing the respect of Rei, Ami, and Mako, and it fucks her up so badly that she can’t even transform any more. As you can tell just from these few paragraphs, this idea is SO INTERESTING to me. What it says about Minako, what it says about her feelings for the others. That she gets so immediately obsessed about being special in SOMETHING that she falls right into a blatantly obvious Dark Moon trap. IT’S LITERALLY PRINTED ON THE BUSINESS CARD.

I’ll get back to the actual summary here in a second, as the concept begins to fall apart as the issue wears on. Minako makes increasing stupid and bad decisions, which are by far more of a threat to her credibility as leader than Ami imagining she and Pluto had a conversation once. But the IDEA is so interesting and solid, and as with all the most frustrating things, it’s the unrealized potential in it that gets to me most. Takeuchi CAN come up with really interesting character-driven ideas, she just doesn’t give a fuck most of the time, and nobody in editorial seems to have either the power or the will to hold her feet to the fire to see it through.

OR TO STOP HER FROM MAKING REALLY GOD AWFUL DECISIONS LIKE TURNING ARTEMIS INTO A GODDAMN PERVERT FOR NO FUCKING REASON. Don’t worry, we’ll get there, friends. Oh, we will get there.

So having had enough of listening to the others sucking some quality Outer Senshi dick, Minako runs off. It should be HER dick, dammit, HER DICK. As she’s running and crying, she gets spotted by a talent scout, who invites her to an idol audition. Attention soothes the savage beast, and Minako returns to her friends with a business card and a hair flip. “Minako, this blatantly says ‘Auditions by EvilCo, Death Guaranteed’,” Rei points out. “WHAT’S THAT THEY LOVE ME YOU’RE RIGHT REI NO MORE DICK FOR YOU BYEEEE.”

As soon as she’s out of there though, Minako curses herself for not noticing (IT IS LITERALLY HALF OF THE WORDS ON THE BUSINESS CARD MINAKO), but then decides to turn this into an opportunity to bust the Dead Moon Circus herself and prove she’s a great leader.

BY NOT LEADING ANYONE I’LL NOTE BUT OKAY MINA THAT’S HOW THAT WORKS SURE

When she gets there, though, there are so many people that she isn’t sure she’ll be able to save them all herself. She considers putting out a call for the others, but there’s a problem.

ALONE THEN YES GOOD VERY LEADERLY.

I honestly feel torn between all of this. On the one hand, Minako is CLEARLY not reacting rationally, and that not only makes sense given where she’s at right now, but it’s pretty consistent with Minako’s character to lash out in extreme ways that have absolutely no bearing on good decision making. On the other, I don’t trust Takeuchi’s ability as a writer whatsoever. So is Minako doing this because it’s in-character, or because Takeuchi’s just not thinking it the fuck through? HOW MUCH DO I WANT TO ARGUE THIS SHIT I GUESS IS WHAT I’M ASKING MYSELF.

And the answer is “It’s 7:30 and you’ve been on this one issue since noon”. Yes, good, well argued, Me.

So Minako keeps flying solo through this entire fucked up audition that includes a group of children trapped up on a trapeze platform. YES REALLY

Minako will abandon them for a little bit later, by the way. Since noon, since noon. Right. Moving on.

Everyone at the competition begins to go evil and shit’s not looking good for Minako. She’s about to be crushed by boulders (yes, boulders, I’ve looked five times and I can’t figure out where they come from, just go with it) when Mako shows up out of nowhere, hops between them and Minako, and blasts them into a thousand pieces, because Makoto Kino is all that is good in the world.

ALL. THAT IS GOOD. IN THE WORLD.

Seriously, Mako simultaneously loving Minako enough to be nearly CRUSHED TO DEATH BY BOULDERS to save her, and so pissed off that the first words out of her mouth after are “SHUT THE FUCK UP” is some goddamn A+ Makoto Kinoing. As frustrated and furious as I am at this issue, I give it up for this moment.

The others are pissed because Minako went to fight the bad guys without them, and I just have to say again I would so love if this were an ongoing THING with Minako, that they’ve had honest to god “YOU CANNOT KEEP DOING THIS TO US” talks about it and shit. And you KNOW Minako would lose her shit if any of them did it to her? Imagine her FURIOUS that Rei risked herself by storming off and going it alone, and then Rei calling her right the fuck back on her hypocrisy. How fucking delicious would that be, jesus wept, I want it so much.

ANYWAY WE DON’T HAVE THAT WE HAVE THAT WE HAVE THIS. Under pressure now, Minako tries again to transform, but can’t. Completely unable to face her friends, she runs off again. She pulls herself together though and tries to save the kids. SURPRISE THEY’RE NOT KIDS. Minako’s fallen right into the Quartet’s trap now. They brainwash her to take the ginzuishou from the others, but before she can try, Artemis appeals to her sense of innate goodness and reason.

But the Quartet spring yet another trap! Minako is plummeting to her doom! Artemis saves her again, disregarding all known laws of physics.

And with boulders raining down on Artemis now, that’s where the issue ends.

OKAY SO LET’S TALK ABOUT THE PERVY CAT IN THE ROOM AND HOW FUCKING ENRAGED I AM BY WHAT IT’S DONE

There are SO MANY levels on which I’m so fucking upset and furious about this Artemis thing, including:

Takeuchi’s repeated genuinely distressing thing about animal/human romance

The idea that any meaningful non-familial male/female relationship must inevitably have that element of sexual attraction

EDIT: @docholligay REMINDED ME ABOUT THE CONSTANT CHIBI-USA AND MAMORU SHIT AND I HAD TO SCRATCH THE NON-FAMILIAL PART WHY WERE WE BORN TO SUFFER

Artemis not just violating Minako’s privacy and trust, but sneaking around as he does it, meaning HE HIMSELF knows it’s wrong, he just doesn’t care

The introduction of this as a thing he’s both willing and capable of, forcing the question of how many times he’s done it in the past

The soiling of their friendship and partnership, which is one of my favourites in the entire franchise fuck you so hard Takeuchi

Some extra creepy issues centered around how Artemis is Minako’s MENTOR for fuck’s sake

How it ruins EVERYTHING ABOUT THIS ENDING

I love the idea of Artemis saving Minako. I love that he’s in this with her, looking out for her, believing in her even when she believes in herself so little she can’t even transform. I wish I could just adore everything about this.

BUT I CAN’T

I can’t, because for NO FUCKING REASON I COULD EVER FATHOM, we’ve now introduced lust into their relationship. We now know, incontrovertibly, that some part of Artemis views Minako as sexually desirable. It colours his motives entirely, however much I wish they fucking didn’t. And because it came out of nowhere IN THIS VERY ISSUE, FOR NO APPARENT REASON, it makes it even MORE dubious that there isn’t some part of Artemis trying so hard to save Minako because he’s “in love” with her.

WHY IS THIS EVEN A THING I HAVE TO FUCKING QUESTION NOW WHY WAS IT SO BLOODY NECESSARY TO PUT THIS IDEA OF ALL IDEAS OUT INTO THE WILD

This has utterly fucked Artemis and Minako’s relationship in the manga for me. I can’t unsee this, I can’t wipe it away. THESE HANDS ARE TAINTED. I may have to go try and flush my brain with some Artemis and Minako hijinks from the anime, to try and prevent rot from setting in there, too.

And I’m so ... ANGRY that this is where I am. And why? What payoff could there possibly be? How myopic was Takeuchi that she didn’t see a problem with that? Or that she thought it was what, sweet? Romantic? NOT LITERALLY SKEEVY AS FUCK AND RUINING SOMETHING BEAUTIFUL

That this is a thing I’m having to deal with, though, it’s such a microcosm of the manga for me. It came from nowhere, it wasn’t thought out, it was probably decided on a whim, and it fucking sucks.

I’M SO SO SORRY ARTEMIS

#JW reads Sailor Moon#sm manga dream#sm manga act 43#jet wolf versus the manga#jet wolf summarizes the manga#a novel by jet wolf

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday Roundup 18.10.2017

When it comes to a variety of genres... I honestly wasn’t very variable this week to be honest. Superheroes and Giant Robots, or otherwise known as two of the three ingredients alongside furry animals and a dash of Chemical X which are required to create a Rena of your very own. But in this contest of Heroes and Robots, the real question is who is going to come out on top? Or at least it should be because people love pitting things against each other and gamifying everything. Or so I’ve heard.

DC’s Batwoman, DC’s DC Comics: Bombshells, DC’s Super Sons, DC’s Titans, DW’s Transformers: Lost Light, Lion Forge’s Voltron Legendary Defender Vol. 2

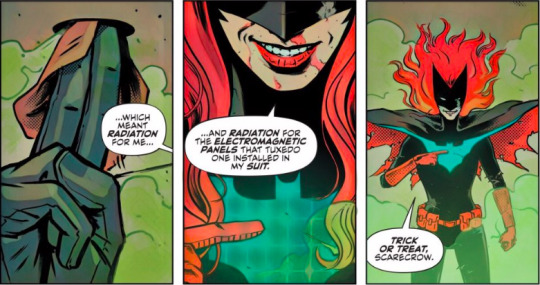

DC’s Batwoman (2017-present) #8 Marguerite Bennett, Fernando Blanco, John Rauch

I was already fully on board with this storyline for Batwoman last month when it was revealed that the Needle was the Scarecrow all along and Kate was in a fear toxin induced fever dream for most of the out there visuals and flashbacks, but that grounding came through in full force this issue as Kate proved herself to not only be a badass and to get herself out in the most seasonally appropriate and cool one-liner of comics this month, but also while never undermining the threat that the Scarecrow poses.

One of my problems with how the Scarecrow has been underused is that not only is he almost always the underling to some greater plot and easily tossed to the side within the narrative -- I could even make a good argument that this is still the case in this storyline -- but the existential threat of having a psychiatrist who is more fascinated with abusing his knowledge and position of power over those he examines, and forcing confrontation of someone’s worst nightmares and fears, is just a fascinating subject that has hardly received its dues in decades now.

And Marguerite Bennett, who has always been someone I trust with a focus on character first, understands that potential and shows that brilliantly over the course of these last two issues. Really, Kate’s character and history has been the focus of this entire run thus far, sometimes even to the detriment of the pacing considering that we take so long to -- for something like the tenth time in half as many years -- retell her origin story, which is something I was pretty critical of, but it is something I appreciate so much more now.

Bennett is truly making Kate her own, and all the backstory, all the set up, helped make the fears and anguish of the fear toxins feel that much more earned within the comic itself when we showed them. Yes, if you’ve been following Batwoman for the past decade which... well, I have -- you can infer a lot of these things without all that set up. Her relationship with her father being complicated, her mother’s death and sister’s kidnapping her original trauma, even the turbulent romance of her year abroad. She didn’t need these things, but having them all presented within the run and really allowing for an insulated story experience for new readers and old alike, frees Kate of so much of the baggage one might have otherwise expected from her at this point.

And it works as it gets us to the gates of a true confrontation with Scarecrow himself. Kate Kane’s traumatic life before and as Batwoman has always been the source of her unyielding attitude and her drive forward. It defines her far differently than the other members of the Batfamily. So facing her fears and overcoming her trauma may have just unleashed a Batwoman that the Scarecrow is even less prepared for than he realizes.

The art in this issue, as the art for this entire series so far has been, is just excellent. It’s stylistic and weaves in and out of traditional paneling to complex, interwoven dreamscapes and I love that we can have that level of detail and understanding without sacrificing readability, which has been a critique I’ve had of Batwoman stories as far back as Elegy itself.

Just overall this was a really inspiring read and it feels especially powerful during the Halloween season. So fantastic timing.

DC’s DC Comics: Bombshells (2015-2017) Vol. 5The Death of Illusion Marguerite Bennett, Laura Braga, Mirka Andolfo, Elsa Charretier

I am not the huge fan of Bombshells that most of the people I know are, and as such I’ve not really gone out of my way to comment on the last few volumes, but it felt a bit incomplete this week to not mention Bombshells since it did come out this week and is taking us to the “new season” that is currently being published.

There are too many artists to really get into on an individual level so I’m instead going to focus on the formatting, as the adaptation from a Digital First to a printed volume is something all the issues share regardless of artist or style. I just want it noted that while I do enjoy the retro pinup style for some characters, I don’t always like it for all characters, and it’s also a judgment call on how well it adapts from artist to artist.

Strangely enough, it feels like the comics that are the least exploratory with being a part of the digital medium and instead are drawn like comic strip-sized panels that are then stacked for physical publication and volumized format are usually the ones that read the weirdest. That continues to prove true in this comic especially since, as overstuffed as this cast is, the limitations of being drawn like they only have half the page to start with, means we get lots and lots of pages where everyone in a scene are crammed in together -- which you can sort of see in the panels I chose to post above. And that inhibits something that Bennett, as a writer, is usually exceptional at. And that’s building female characters from and around their environment.

Look at those last two panels and think of how much more impactful that sense of loneliness and being surrounded would feel for Ivy if there had been more space to allow that sense to come across.

And that bleeds right into a general writing issue I’ve had with Bombshells since the start. I, on principle, love all the characters and I love the world and the world building. There is precious little that is not inherently appealing to me about this series.

But I feel like I have so few central characters to focus on because of how bloated the cast is and how intertwined all the characters and events are, that I’m left almost annoyed at the fact that we can’t say who, in any one issue, is the central protagonist. And even if that’s a problem I’ve had a sense of from the start, it’s becoming more of a problem in this volume than any of the one before because they’re fitting so much in any one issue. We had the introductions of at least ten characters that I can remember who are obviously going to be prominent, the concept of this universe’s Suicide Squad, and the idea that Hugo Strange is working for all sides and countries at the same time while cloning Kara even though.... Russia had had her loyalty before and... I don’t know. It’s a lot. It’s a whole lot at once.

And even though this is counter to my main argument, I’m getting really damn annoyed that every Batgirl and Batgirl adjacent character in the damn world has been featured now as a Batgirl or otherwise now except for Steph and Cass. Like. Why. What’s the point.

DC’s Super Sons (2017-present) #9 Peter J. Tomasi, Jorge Jimenez, Carmine Di Giandomenico, Alejandro Sanchez, Ivan Plascencia

Super Sons wraps up yet another arc but this time around we have a bit of a juggling act being performed with the artist chair. This isn’t to say it gets completely distracting, but there are a few transitions that were not nearly as smooth as they could have been. I am more of a fan of books who switch artists at least attempting to maintain a theme, but as far as getting the job done story wise, Super Sons more than steps up to the plate.

But of course that leaves the question of what I feel about the storyline and... I still enjoy it! I stand by my consistent criticisms that without Gleason, Tomasi tends to invest more in Jon being the Perfect Child foil to Damian rather than digging into his own insecurities and flaws, and that definitely applies here where he moralizes to save the day and also drops the very interesting thread of plot that actually had me hopeful that we would be seeing more angles to Jon’s naivety, what with the possibility of Damian finally revealing that it was Lois who asked Damian to befriend/train Jon all along, but does it work for having our two young heroes inspiring an entire future of heroes for a parallel dimension?

Sure! I would think so. It feels like Jon and Damian’s new friends and this parallel world are going to be the Legion of Superheroes to Jon’s Superboy which is honestly a pretty exciting idea and is neat to see in the context of modernizing an old idea with a whole new spin and within the current comic landscape.

Or we’ll never see any of this again because comics do that sometimes. It’s hard to tell.

Personally, I enjoyed the ending, even if it was mostly action and explosions, but it’s like I always tag here on the blog -- Every Story Needs an Explosion!

.... I also have a tag on this blog that is “Sun Bleached” for characters who are whitewashed and goddamn DC, you have got to get a memo out to all your colorists on rather or not you’re going to commit to Damian being dark skinned or not. And don’t think I don’t notice that he and Talia both shift between “white” and “brown” depending on the morality they’re showing at any one time. I’ve seen the panels of Batman #33. I see you.

DC’s Titans (2016-present) #16 Dan Abnett, Brett Booth, Norm Rapmund, Andrew Dalhouse

I’ll be honest.... this wasn’t the best issue. And it’s not that it’s bad it was just that it felt entirely skippable. Young Wally shows up but we don’t at all get any time with him to have more than a surprised reaction -- there’s no time to see him mourn or get angry or anything. And the rest of the Titans don’t really have that time either. They’re just more angry than they had been in the last issue and... judging by solicits Wally’s going to be back so the emotional stakes and catharsis were pretty much all we had for this issue.

Instead it was purely fighting and not really even fighting that came to a conclusive end. After all, we still have another issue to go and none of the possessed Titans were freed either. Instead it just leads to.... well an Evil Donna reveal which... I don’t know what that’s going to lead to because I’m still wondering what we’re going to be doing about Wally and Wally!

Overall I still like Titans but this is one issue that really gives me nothing to add or even to say that I haven’t mentioned in previous Roundups because, for me, this issue didn’t do a great job of adding anything writing or art wise.

Just gotta wait for next month then.

IDW’s Transformers: Lost Light (2017-present) #10 James Roberts, Jack Lawrence, Joana Lafuente

In all honesty, the last couple of issues of Transformers: Lost Light have made me feel things that I haven’t since James Roberts’ “First Season” of MTMTE. It really, truly feels like he is back on his A-game and that we’re getting places where his original outline had us going before the whole Dark Cybertron stuff jumped into the fray.

And if it wasn’t obvious from my Batwoman review, it’s because i really really love fridge horror and mind trips and just in general when stories shock me with where they’re willing to go with their characters. Because this is dark. Arguably this issue reveals itself to be darker than almost anything else that Roberts has shown us in his Transformers yet.

Which, again, is saying something.

And it’s darkness an passing a moral event horizon that is really necessary to get us on board with having Getaway and other mutineers as bigger villains than the likes of every other antagonist that the Lost Light crew has encountered so far. I mean, that’s a hell of a direction to take us and yet it’s managed because we’re now beyond just the hatred for what he did to Cyclonus and Tailgate, we’re down the moral sinkhole where his actions are not justified at all. Where you arguably could see the reasons for mutiny when they did so in the last arc of MTMTE.

Now he’s just. Straight up a villain? Though that comes with some questions of its own because before he didn’t seem to be happy that the Black Block Consortia was going to destroy all of them. He jsut... wanted them to not be on the Lost Light? Or so I thought? He did call the DJD, but specifically he thought it was just for Megatron so idk. I literally don’t know but I’m fascinated to see things from Getaway’s perspective.

And speaking of perspectives, I already adored First Aid but he was so good in this issue, and this his discoveries and the further and the further and further down the hole things went from there felt like my stomach was dropping each time. To the point where I wanted to just scream “it’s a trap” multiple times.

It’s just good stuff, I really enjoyed this issue and am on the edge of my seat for what’s coming up.

Lion Forge’s Voltron Legendary Defender Vol. 2 (2017-present) #2 Tim Hedrick, Mitch Iverson, Rubine, Beni Lobel

Okay. All my skepticism before, all my complaints, all my concerns that both art and characterizations were lacking in this story compared to the actual series? I take it back because... I had an absolute blast reading this issue.

So along with our art change, we get something in this issue that we honestly haven’t even gotten from the series, and that is non-food related Hunk centric storylines with him being hailed as a hero to an entire species, having girl problems, and people literally fighting for the right to marry him. Even if those people are more like... sexy female Knuckles and Sonic.

Anyway. This issue pretty much addresses everything I was worried that we were missing before. There’s a coherent plot with a clear need for the individual paladins as well as Voltron all together, there’s jokes but not so much at the expense of a character’s dignity, and Hunk... Hunk is treated better in this issue than he is for the majority of episodes for the last three seasons of the show and I’m genuinely kind of floored by this fact.

There’s a scene I absolutely loved where Hunk, baffled at his own situation, even goes to Lance and they have a whole page dedicated to their heart to heart. Lance ranges from jealous to sarcastic, to genuinely helpful and it’s the first time that any of the franchise has remembered they were friends and roommates first before anyone else.

I was genuinely surprised with how much I enjoyed this issue and if I could give a reward for the single most improvement from one issue to the next it would go to Voltron this week.

Though I will say, c’mon artists, backgrounds are a pain but you have to treat them like your friends. You can’t rely on gradients 100% of the time.

So while there was some harsh criticisms I had this week, I think overall it showed to be a pretty good week for comics, and more than a couple of surprises came up to really make me sit back and reflect on things. But with little doubt, my pick of the week has to be Batwoman because that series and Marguerite Bennett just as a writer on her own have managed to really redefine a familiar character and make her story her lore, and her personality stand proud and alone from all the strings of continuity that has been supposedly holding her back for all these years. I absolutely love it and can’t wait for the next issue.

And those are the comics for this week! Did you happen to agree with me? Disagree? Think I missed out on picking up a comic that was good? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

But before I let you go, I have to (yes have to) plug once more:

I have exactly a month to pack up everything I own and move halfway across the country again which is not helping those financial crunches I mentioned before either.

As such, I really would appreciate if you enjoy my content or are interested in helping me out, please check out either my Patreon or PayPal. Every bit helps and I couldn’t thank you enough for enjoying and supporting my content.

You could also support me by going to my main blog, @renaroo, where I’ll soon be listing prices and more for art and writing commissions.

RenaRoo Ko-Fi

RenaRoo Patreon

RenaRoo PayPal

#Rena Roundups#Wednesday Spoilers#SPOILERS#DC Comics: Bombshells (2015 2017)#Voltron Legendary Defender Vol. 2#Transformers: Lost Light (2016 )#Titans (2016 )#Super Sons (2017 )#Batwoman (2017 )

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The controversy over the new immigration novel American Dirt, explained

On January 21, Oprah Winfrey announced that Jeanine Cummins’s novel American Dirt would be her next book club pick. Winfrey is pictured here with Cummins, Gayle King, Anthony Mason, and Tony Dokoupil. | CBS via Getty Images

A non-Mexican author wrote a book about Mexican migrants. Critics are calling it trauma porn.

The new novel American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, officially released on Tuesday, was anointed the biggest book of the season well before it ever came out.

It sold to Flatiron Books at auction for a reported seven-figure advance. Flatiron announced a first print run of 500,000 copies. (For most authors, a print run of 20,000 is pretty good.) It received glowing blurbs from luminaries like Stephen King, John Grisham, and Sandra Cisneros. Early trade reviews were rapturous. The New York Times had it reviewed twice — once in the daily paper, once in the weekly Book Review — and also interviewed the author and published an excerpt from the novel.

But over the past few days, the narrative around American Dirt has changed. One of those New York Times reviews was a pan, the other was mixed at best. Another critic revealed that she’d written a review panning the book, too, and the magazine that commissioned her review killed it.

All of these negative reviews centered on one major problem: American Dirt is a book about Mexican migrants, and author Jeanine Cummins identified as white “in every practical way,” as recently as 2016. (She has since begun to discuss a Puerto Rican grandmother.) Cummins had written a story that was not hers — and, according to many readers of color, she didn’t do a very good job of it. In fact, she seemed to fetishize the pain of her characters at the expense of treating them as real human beings.

So on Tuesday morning, when Oprah announced that American Dirt would be the next book discussed in her book club, the news was treated not as the crown jewel in the coronation of the novel of the season, but as a slightly awkward development for Oprah.

Oprah, lounging in a silk robe, sipping her morning coffee, copies of Groff's and Seghal's reviews of AMERICAN DIRT on the coffee table. She picks up her phone and thinks: I'll show these literary girls what chaos is

— joshua gutterman tranen (@jdgtranen) January 21, 2020

The story of American Dirt has now become a story about cultural appropriation, and about why publishing as an industry chose this particular tale of Mexican migration to champion. And it revolves around a question that has become fundamental to the way we talk about storytelling today: Who is allowed to tell whose stories?

“I wished someone slightly browner than me would write it”

American Dirt is a social issues thriller. It tells the story of a mother and son, Lydia and Luca, fleeing their home in Acapulco, Mexico, for the US after the rest of their family is murdered by a drug cartel. Lydia is a bookstore owner who never thought of herself as having anything in common with the migrants she sees on the news, but after she comes up with the plan of disguising herself by posing as a migrant, she realizes that it won’t really be a disguise: It’s who she is now.

In her author’s note, Cummins explains that she wrote American Dirt in an attempt to remind readers — presumably white readers — that Mexican migrants are human beings. “At worst, we perceive them [migrants] as an invading mob of resource-draining criminals, and, at best, a sort of helpless, impoverished, faceless brown mass, clamoring for help at our doorstep,” she writes. “We seldom think of them as our fellow human beings.”

Cummins also says in the note that she recognizes that this story may not be hers to tell, while stressing that her husband is an immigrant and that he used to be undocumented. She does not include in the note the fact that her husband immigrated to the US from Ireland, an elision that some observers have taken to be strategic, as though Cummins wishes to give the impression that her husband is Latino and is in just as much danger of being held in a cage at the border as the people she is writing about.

“I worried that, as a nonmigrant and non-Mexican, I had no business writing a book set almost entirely in Mexico, set entirely among migrants. I wished someone slightly browner than me would write it,” Cummins says. (It is worth noting at this juncture that plenty of people who are slightly browner than Cummins have in fact written about Mexican migration.) “But then, I thought, If you’re a person who has the capacity to be a bridge, why not be a bridge?” Cummins continues. And so she spent years working on this book, traveling on both sides of the border and interviewing the people she met there.

American Dirt is explicitly addressed to non-Mexican readers by a non-Mexican author, and it is framed as a story that will remind those readers that Mexican migrants are human beings. And for some readers, including some Latinx readers, Cummins was successful in her aims. In her blurb for the book, the legendary Mexican-American author Sandra Cisneros declared herself a fan, writing, “This book is not simply the great American novel; it’s the great novel of las Americas. It’s the great world novel! This is the international story of our times. Masterful.”

But for other readers, American Dirt is a failure. And it fails specifically in achieving its ostensible goal: to appreciate its characters’ humanity.

“It aspires to be Día de los Muertos but it, instead, embodies Halloween”

The first true pan of American Dirt came out in December, on the academic blog Tropics of Cancer. In it, the Chicana writer Myriam Gurba takes Cummins to task for “(1) appropriating genius works by people of color; (2) slapping a coat of mayonesa on them to make palatable to taste buds estados-unidenses and (3) repackaging them for mass racially ‘colorblind’ consumption.”

Gurba describes American Dirt as “trauma porn that wears a social justice fig leaf,” arguing, “American Dirt fails to convey any Mexican sensibility. It aspires to be Día de los Muertos but it, instead, embodies Halloween.” Most especially, she critiques the way Cummins positions the US as a safe haven for migrants, a utopia waiting for them outside of the bloody crime zone of Mexico. “Mexicanas get raped in the USA too,” she writes. “You know better, you know how dangerous the United States of America is, and you still chose to frame this place as a sanctuary. It’s not.”

Moreover, Gurba notes that American Dirt has received the kind of institutional support and attention that books about Mexico from Chicano authors rarely do. “While we’re forced to contend with impostor syndrome,” she writes, “dilettantes who grab material, style, and even voice are lauded and rewarded.”

Gurba originally wrote her review for Ms. magazine, but it never appeared there. “I had reviewed for them before,” Gurba told Vox over email. But this time, “when they received my review, they rejected it, telling me I’m not famous enough to be so mean. They offered to pay me a kill fee but I told them to keep the money and use it to hire women of color with strong dissenting voices.”

Gurba says she’s had a mostly positive response to her review, “except for the death threats.” She maintains that American Dirt is a very bad book.

“American Dirt is a metaphor for all that’s wrong in Big Lit,” she says: “big money pushing big turds into the hands of readers eager to gobble up pity porn.”

“I was sure I was the wrong person to review this book”

Gurba’s review established the counter narrative on American Dirt, but that new narrative didn’t become the dominant read until last Friday. That’s when the New York Times published a new negative review by Parul Sehgal, one of the paper’s staff book critics.

“Allow me to take this one for the team,” Sehgal wrote. “The motives of the book may be unimpeachable, but novels must be judged on execution, not intention. This peculiar book flounders and fails.”

Sehgal, who is of Indian descent, says that she believes in the author’s right to write about “the other,” which she argues fiction “necessarily, even rather beautifully” requires. But American Dirt, she says, fails because of the ways in which it seems to fetishize its characters’ otherness: “The book feels conspicuously like the work of an outsider,” she writes.

And, putting aside questions of identity and Cummins’s stated objective, Sehgal finds that American Dirt fails to make the argument that its characters are human beings. “What thin creations these characters are — and how distorted they are by the stilted prose and characterizations,” she says. “The heroes grow only more heroic, the villains more villainous.”

Two days after Sehgal’s review came out in the daily New York Times, the paper published another review from the novelist Lauren Groff in its weekly Book Review section. Groff, who is white, was less critical of American Dirt than Sehgal was, but her review was far from an unmitigated rave: It wrestles with a number of questions over whether Cummins had the right to write this book.

But you would not know as much from the Book Review’s Twitter account, which posted a link to Groff’s published review with a quote that appears nowhere within it. “‘American Dirt’ is one of the most wrenching books I have read in the past few years, with the ferocity and political reach of the best of Theodore Dreiser’s novels,” said the now-deleted tweet.

“Please take this down and post my actual review,” Groff responded.

According to Book Review editor Pamela Paul, the tweet used language from an early draft of Groff’s review and was an unintentional error. But for some observers, that tweet, combined with the deluge of coverage the New York Times was offering Cummins, made it appear that the paper had an agenda: Was it actively trying to make American Dirt a success?

The Times’ intentions aside, in her review, Groff treats American Dirt as a mostly successful commercial thriller with a polemic political agenda, as opposed to Sehgal, who treated it as a failed literary novel. (Arguably, Groff is being truer to the aims of American Dirt’s genre than Sehgal was, but given that American Dirt is a book whose front cover contains a blurb calling it “a Grapes of Wrath for our times,” it’s hard to say that Sehgal’s expectations for literary prose were unmerited.) Groff praises the novel’s “very forceful and efficient drive” and its “propulsive” pacing, but she also finds herself “deeply ambivalent” about it.

“I was sure I was the wrong person to review this book” as a white person, she writes, and became even more sure as she learned that Cummins herself was white. Groff spends much of her review wrestling with her responsibility as a white critic of a novel addressed to white people by a white author about the stories of people of color, and ends without arriving at a satisfying answer. “Perhaps this book is an act of cultural imperialism,” she concludes; “at the same time, weeks after finishing it, the novel remains alive in me.”

On Twitter, Groff has called her review “deeply inadequate,” and said she only took the job in the first place because she didn’t think the Times would ask anyone else who was willing to wrestle with the responsibility of criticism in the course of reviewing it. “Fucking nightmare,” she tweeted.

Fucking nightmare.

— Lauren Groff (@legroff) January 19, 2020

In the wake of these reviews, the American Dirt controversy has coalesced around two major questions. The first is an aesthetic question: Does this book fetishize and glory in the trauma of its characters in ways that objectify them, and is that objectification what always follows when people write about marginalized groups to which they do not belong?

The second is a structural question: Why did the publishing industry choose this particular book — about brown characters, written by a white woman for a white audience — to throw its institutional force behind?

“Writing requires you to enter into the lives of other people”

The aesthetic question is more complicated than it might initially appear to be. People sometimes flatten critiques like the one American Dirt is facing into a pat declaration that no one is allowed to write about groups of which they are not themselves a member, which opponents can then declare to be nothing but rank censorship and an existential threat to fiction itself: “If we have permission to write only about our own personal experience,” Lionel Shriver declared in the New York Times in 2016, “there is no fiction, but only memoir.”

But in fact the most prominent voices in this debate have tended to say that it is entirely possible to write about a particular group without belonging to it. You just have to do it well — and part of doing it well involves treating your characters as human beings, and not luxuriating in and fetishizing their trauma.

In another New York Times essay in 2016, Kaitlyn Greenidge described reading a scene written by an Asian American man that described the lynching of a black man. She strongly felt that this Asian American author had the right to write such a scene, she says, “because he wrote it well. Because he was a good writer, a thoughtful writer, and that scene had a reason to exist besides morbid curiosity or a petulant delight in shrugging on and off another’s pain.”

Brandon Taylor made a similar point at LitHub earlier in 2016, arguing that successful writers have to be able to write with empathy. “Writing requires you to enter into the lives of other people, to imagine circumstances as varied, as mundane, as painful, as beautiful, and as alive as your own,” Taylor said. “It means graciously and generously allowing for the existence of other minds as bright as quiet as loud as sullen as vivacious as your own might be, or more so. It means seeing the humanity of your characters. If you’re having a difficult time accessing the lives of people who are unlike you, then your work is not yet done.”

Critics of American Dirt are making the case that Cummins has failed to do the work of empathy. They are arguing that she has the right to write from the point of view of Mexican characters, but that they have the right to critique her in turn, and that what their critiques reveal is that she does not see the humanity of her characters. They are arguing that instead, American Dirt has done the opposite of what Greenidge applauded that lynching scene for accomplishing. That the book has failed to suggest “a reason to exist besides morbid curiosity or a petulant delight in shrugging on and off another’s pain.”

It’s in the spirit of that reading — of American Dirt as a failure in empathy, as trauma porn — that Gurba noted on Twitter Wednesday morning that an early book party that Flatiron Books created for Cummins featured barbed wire centerpieces.

pic.twitter.com/6W8suWpCUD

— Myriam Chingona Gurba de Serrano (@lesbrains) January 22, 2020

Those centerpieces are all about the aesthetic splendor of migrant trauma, about the idea of reveling in the thrill of the danger that actual human beings have to deal with every day, without ever worrying that you personally might be threatened. They’re a fairly good illustration of what the phrase “trauma porn” means.

“I only know one writer of color who got a six-figure advance and that was in the ’90s”

The institutional questions about American Dirt are more quantitative. They progress like this: There are plenty of authors of color writing smart, good stories about their experiences. And yet American Dirt, a novel written by a white woman for a white audience, is the book about people of color that landed the seven-figure advance and a publicity budget that could result in four articles in the New York Times. Why has publishing chosen to allocate its resources in this way?

Flatiron Books has defended its choice. “Whose stories get told and who can tell them are important questions,” says Amy Einhorn, Cummins’s acquiring editor and Flatiron’s founder, in a statement emailed to Vox. “We understand and respect that people are discussing this and that it can spark passionate conversations. In today’s turbulent times, it’s hopeful and important that books still have power. We are thrilled that some of the biggest names in Latinx literature are championing American Dirt.”

It is worth pointing out here that Einhorn, a well-respected industry vet, was also the acquiring editor of the 2009 novel The Help, a novel by a white woman about black women in the 1950s. The Help was a bestseller and a major success, but it was also the subject of a critique similar to the one American Dirt is experiencing now, with readers arguing that The Help gloried in fetishizing the pain of its subjects.

Meanwhile, authors of color say that they rarely see publishers investing the kind of money and support in their own books on the level that The Help and American Dirt received.

“I got sexually assaulted by a serial killer in 1996. I wrote a book about that. Most of the subjects in that book are Mexicans and Chicanx. I got paid $3,000 for my story,” Gurba says. “So yes, the publicity surrounding American Dirt is unfamiliar to say the least.”

“I’ve always had five-figure advances (my fourth book comes out this spring) and many of my friends have gotten four figures — and they are mostly writers of color,” said the novelist Porochista Khakpour in an email to Vox. “I only know one writer of color who got a six-figure advance and that was in the ’90s.”

Khakpour adds that the level of hyperbolic attention American Dirt has received, especially from the New York Times, is deeply unusual for publishing. “I only got a Sunday [New York Times Book Review] review for my first novel and that felt like a miracle,” she says. “Again, most writers of color I know are published by indies or academic presses and it’s hard for them to get the attention of the Times. I write for the NYTBR and I can honestly say I’ve never seen this much attention given to a book — I find it embarrassing.”

Both Khakpour and Gurba argue that American Dirt was appealing to publishers because white people tend to be most comfortable reading about people of color as objects of suffering.

“Certain narratives that flirt with poverty porn make liberal white people feel good about their opinions,” Khakpour says. “They feel like they learn something, like by reading these accounts they are somehow participating in helping the world they usually feel so helpless about.”

Gurba says many white people expect to see her enact such narratives herself and become angry when she doesn’t. “Recently, a white woman got angry at me when she found out that I’m Mexican,” Gurba says. “She insisted that I didn’t look or act Mexican and that I had confused her. But she confused herself. She had a stereotype of what Mexicans are. I defied it. That made her uncomfortable. Now, apply that scenario to the literary equation [American Dirt has] presented.”

The narratives Gurba and Khakpour suggest both assume that the decision makers on American Dirt were white. And there is very good reason for that assumption: Publishing is an extremely white industry.

According to trade magazine Publishers Weekly, white people made up 84 percent of publishing’s workforce in 2019. Publishing is staffed almost entirely by white people — and in large part, that fact can be explained by publishing’s punishingly low entry-level salaries.

A job as an editorial assistant pays around $30,000, and it means living in New York City, where conservative estimates generally say you need an annual salary of about $40,000 before taxes to get by. But landing a position as an editorial assistant is generally a promotion: to get one, you usually have to spend a season or two working as an intern first, for low or no pay.

Such salaries mean that the kind of people who work in publishing tend to be the kind of people who can afford to work in publishing: those who are carrying little student debt and who can rely on their parents to supplement their salaries as necessary. And mostly, those people tend to be white.

As a result, publishing is predominantly staffed with well-meaning white people who, when looking for a book about the stories of people of color, can find themselves drawn toward one addressed specifically toward white people — and who will lack the expertise to question that book’s treatment of its characters. Which means that as long as publishing continues to be overwhelmingly, monolithically white, it will continue to find itself mired in controversies like the one surrounding American Dirt.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2vaaciE from Blogger https://ift.tt/2RCGOJy via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

I cannot make any of the poster images work to my satisfaction, but Stephanie as Spoiler is a Barbie, while Stephanie as Batgirl is Ken.

This Barbie is attempting to murder her dad. This Barbie holds evidence hostage to be involved in a case. This Barbie sews her own superhero costume from scratch. This Barbie fucks unapologetically. This Barbie got her jaw fractured by her best friend. This Barbie stalked her boyfriend and stole his mantle. This Barbie survives torture and fakes her death.

Ken is just here.

Saw someone claim that canon Stephanie Brown has the character arc / development that "fanon [redacted]" has and buddy I hate to break it to you, but Preboot era Stephanie has the character development of a flat tire.

Stephanie starts out as a decently rounded supporting character who acts as a foil & peer to first Tim and then Cass. She's abrasive, pushy, and impulsive, which works for the narrative role she's in. She has some interesting moments of minor growth and glimpses of potential for more that unfortunately don't really go anywhere.

Then she gets screwed over by editorial's desire for grimdark edginess, dies, turns out not to be dead, and comes back having learned absolutely nothing from her mistakes (including, frankly, the mistake of thinking Bruce Wayne knows what he's doing).

Her following solo title insults other women characters to prop her up, acts like her past mistakes which got people killed are just a minor whoopsie that doesn't need to be addressed, and by the end of the run she's in the exact same narrative place she started.

I suspect if Stephanie hadn't died, or even if she'd died in a different way, she'd have continued to be a decently rounded character. Maybe she wouldn't have learned from her mistakes, but she'd have been allowed to be wrong. Maybe some of those glimpses of potential growth would have finally been followed up!

As-is, it feels like once she came back, DC didn't want to let the narrative criticize her at all, in case they be accused of victim blaming.

Which makes for a very flat character.

#Barbie Poster Meme#sans actual poster#Batgirl 2009 Critical#Stephanie Brown Critical#sort of? it's mostly critical of the writing post death rather than the character herself#recycling that tag#Stephanie Brown#Spoiler#Batfam#DC

79 notes

·

View notes