#something something the work being kind of originated by a volcanic eruption. volcanoes are obviously mountains. a.b.a; a character who take

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Almost 2 months later, I remembered this and went to properly check it. As per (my clunky) wikipedia paraphrasing:

Shelley was born on August 30th 1797. The famed summer when she, her later husband Percy Shelley, Lord Byron and John Polidori had their ghost story writing contest happened in 1816. Now as far as I am aware we don't have a specific date. She could've even perhaps been 19 if we assume this all happened in late summer (after all, the uncharacteristic bad weather that kind of kickstarted the contest could be argued to be more proper for early autumn, hah Nevermind, just read that apparently 1816 was known as the Year without Summer, as the world was experiencing a volcanic winter courtesy of the eruption of Mount Tambora! Wow, til!), however, according to both the National Institute of Medicine and Anthony Badalamenti, she was 18 when she won the context. Hence, Shelley was 18 when Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus won the writing contest.

Now, it wasn't til January 1st 1818 that the book's first edition would release (anonymously), so Shelley was 20 when the first edition of Frankenstein hit the shelves. (In just 500 copies at that!)

It wasn't til the second edition, released on August 11th 1821, that it was properly atributed to Mary Shelley, who was still 20.

[Edit: Alright I missed a part while typing and I'm too tired to not to fully copy it so, here's the full wiki paragraph on its own:]

"A French translation (Frankenstein: ou le Prométhée Moderne, translated by Jules Saladin) appeared as early as 1821. The second English edition of Frankenstein was published on 11 August 1823 in two volumes (by G. and W. B. Whittaker) following the success of the stage play Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein by Richard Brinsley Peake. This edition credited Mary Shelley as the book's author on its title page."

Nonetheless! It wasn't til October 31st 1831 that we met the first "popular" edition, a less radical revision by Shelley herself, published by Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley. (Fun facts: Colburn was an exalted purveyor of "silver fork" novels, and you might be familiar with certain of Bentley's periodical's editors (before he left): Charles Dickens)

Here, Shelley was 34 years old.

Curiously, most modern reprints/editions(?) of the book are based off this revision, though there are select publications that still use Shelley's previous writing, and with some scholars prefering it due to considering it closer to the author's original vision.

So in conclusion, while Shelley was indeed 18 when she first wrote the book, it wasn't published and then revised til years later. Regardless of if you want to consider them part of the timeline til we got the most widespread version of the book, I still hold the opinion that even already having the very first pass of such a revolutionary novel at just 18 is incredible.

I also find inspiring that there were retouches of the novel years later. Sure, they were mostly adding author credit or making it less radical (the latter which may be a detriment to the novel by some analists), but they show us that even years later you can pick up your passion project once again for whatever reason... and that you're in your right to do so, no matter if you're not as young as you first were. Don't let anyone hold you back!

I'm pretty sure I read this before but I forgot til now, that Mary Shelley was just 18* when she first wrote Frankenstein... And it dawned on me... So young! I'm in awe at the talent and the skill she showed so young, hats off!

*some sources say she was 19? I'm not sure, though it seems that 18 is the bigger consensus

#oh God that last paragraph got too ''!!!“ haha#can you tell I'm finding this book's publication history almost as fascinating as the book itself#the big revision was published on halloween!? dunno if that was on purpose nor if halloween as we know it was celebrated back then (might#look it up in a different moment. again I'm tired) but if not what a coincidence!#I'm 95% sure that my copy is that version but I gotta check#hmm.. dunno. my copy has (very cool) John Coulthart illustrations (current-day artist) but many publications have it. in fact I cannot find#my book's preface's author?? mysterious but... since it isn't mentioned to be pre-31/oct and apparently those type of editions are ar and#few between... we'll go with my copy being based off 31/oct's like most of them!#this is somehow still a gu.ilty gear blog LOL#something something the work being kind of originated by a volcanic eruption. volcanoes are obviously mountains. a.b.a; a character who take#s some inspiration from said work comes from a manor nearby a mountain village (which as I have prev said. all those years closed inside the#house. the mountains by proxy makes her love of the sea be possibly deeper (heh) than we thought#does that mean anything? WHAT DOES IT MEAN. WHAT DOES IT MEAN!!!#I'm aware I'm making quite the reach even if Ishiwatari and Mori's visions are so impressive but omg. omg guys!?#how poetic..#text tag2b named#frankentag2b named#long post

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Noir Zealand Road Trip.

Breakout noir filmmaker James Ashcroft speaks to Letterboxd’s Indigenous editor Leo Koziol about his chilling new movie Coming Home in the Dark—and reveals how Blue Velvet, Straw Dogs and a bunch of cult New Zealand thrillers are all a part of his Life in Film.

“Many different types of feet walk across those lands, and the land in that sense is quite indifferent to who is on it. I like that duality. I like that sense of we’re never as safe as we would like to think.” —James Ashcroft

In his 1995 contribution to the British Film Institute’s Century of Cinema documentary series, Sam Neill described the unique sense of doom and darkness presented in films from Aotearoa New Zealand as the “Cinema of Unease”.

There couldn’t be a more appropriate addition to this canon than Māori filmmaker James Ashcroft’s startling debut Coming Home in the Dark, a brutal, atmospheric thriller about a family outing disrupted by an enigmatic madman who calls himself Mandrake, played in a revelatory performance by Canadian Kiwi actor Daniel Gillies (previously best known for CW vampire show The Originals, and as John Jameson in Spider-Man 2). Award-winning Māori actress Miriama McDowell is also in the small cast—her performance was explicitly singled out by Letterboxd in our Fantasia coverage.

Based on a short story by acclaimed New Zealand writer Owen Marshall, Ashcroft wrote the screenplay alongside longtime collaborator Eli Kent. It was a lean shoot, filmed over twenty days on a budget of just under US $1 million. The film is now in theaters, following its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January, where it made something of an impact.

Erik Thomson, Matthias Luafutu, Daniel Gillies and Miriama McDowell in a scene from ‘Coming Home in the Dark’.

Creasy007 described the film as “an exciting New Zealand thriller that grabs you tight and doesn’t let you go until the credits are rolling.” Jacob wrote: “One of the most punishingly brutal—both viscerally and emotionally—first viewings I’ve enjoyed in quite a while. Will probably follow James Ashcroft’s career to the gates of Hell after this one.”

Filmgoers weren’t the only ones impressed: Legendary Entertainment—the gargantuan production outfit behind the Dark Knight trilogy and Godzilla vs. Kong—promptly snapped up Ashcroft to direct their adaptation of Devolution, a high-concept novel by World War Z author Max Brooks about a small town facing a sasquatch invasion after a volcanic eruption. (“I find myself deep in Sasquatch mythology and learning a lot about volcanoes at the moment,” says the director, who is also writing the adaptation with Kent.)

Although Coming Home in the Dark marks his feature debut, Ashcroft has been working in the creative arts for many years as an actor and theater director, having previously run the Māori theater company Taki Rua. As he explains below, his film taps into notions of indigeneity in subtle, non-didactic ways. (Words in the Māori language are explained throughout the interview.)

Kia ora [hello] James. How did you come to be a filmmaker? James Ashcroft: I’ve always loved film. I worked in video stores from the age thirteen to 21. That’s the only other ‘real job’ I’ve ever had. I trained as an actor, and worked as an actor for a long time. So I had always been playing around with film. My first student allowance that I was given when I went to university, I bought a camera, I didn’t pay for my rent. I bought a little handheld Sony camera. We used to make short films with my flatmates and friends, so I’ve always been dabbling and wanting to move into that.

After being predominantly involved with theater, I sort of reached my ceiling of what I wanted to do there. It was time to make a commitment and move over into pursuing and creating a slate of scripts, and making that first feature step into the industry. My main creative collaborator is Eli Kent, who I’ve been working with for seven years now. We’re on our ninth script, I think.

But Coming Home in the Dark, that was our first feature. It was the fifth script we had written, and that was very much about [it] being the first cab off the rank; about being able to find a work that would fit into the budget level that we could reasonably expect from the New Zealand Film Commission. I also wanted to make sure that piece was showing off my strengths and interests—being a character-focused, actor-focused piece—and something that we could execute within those constraints and still deliver truthfully and authentically to the story that we wanted to tell and showcase the areas of interest that I have as a filmmaker, which have always been genre.

Do you see the film more as a horror or a thriller? We’ve never purported to be a horror. We think that the scenario is horrific, some of the events that happen are horrific, but this has always been a thriller for me and everyone involved. I think, sometimes, because of the premiere and the space that it was programmed in at Sundance, being in the Midnight section, there’s a sort of an association with horror or zany comedy. For us it’s more about, if anything, the psychological horror aspect of the story.

It’s violent in places, obviously, but there’s very little violence actually committed on screen. It’s the suggestion. The more terrifying thing is what exists in the viewer’s mind [rather] than necessarily what you can show on screen. My job as a storyteller is to provoke something that you can then flesh out and embellish more in your own psyche and emotions. It’s a great space, the psychological thriller, because it can deal with the dramatic as well as some of those more heightened, visceral moments that horror also can touch on.

Director James Ashcroft. / Photo by Stan Alley

There’s a strong Māori cast in your film. Do you see yourself as a Māori filmmaker, or a filmmaker who is Maori? Well, I’m a Māori everything. I’m a father, I’m a husband, I’m a friend. Everything that I do goes back to my DNA and my whakapapa [lineage]. So that’s just how I view my identity and my world. In terms of categorizing it, I don’t put anything in front of who I am as a storyteller. I’m an actor, I’m a director. I follow the stories that sort of haunt me more than anything. They all have something to do with my experience and how I see the world through my identity and my life—past, present and hopefully future.

In terms of the cast, Matthias Luafutu [who plays Mandrake’s sidekick Tubs], he’s Samoan. Miriama McDowell [who plays Jill, the mother of the family] is Māori. I knew that this story, in the way that I wanted to tell it, was always going to feature Māori in some respect. Both the ‘couples’, I suppose you could say—Hoaggie [Erik Thomson] and Jill on one side and Tubs and Mandrake on the other—I knew one of each would be of a [different] culture. So I knew I wanted to mirror that.

Probably more than anything, I knew if I had to choose one role that was going to be played by a Māori actor, it was definitely going to be Jill, because for me, Jill’s the character that really is the emotional core and our conduit to the story. Her relationship with the audience, we have to be with her—a strong middle-class working mother who has a sort of a joy-ness at the beginning of the film and then goes through quite a number of different emotions and realizations as it goes along.

Those are sometimes the roles that Māori actors, I often feel, don’t get a look at usually. That’s normally a different kind of actor that gets those kinds of roles. And then obviously when Miriama McDowell auditions for you it’s just a no-brainer, because she can play absolutely anything and everything. I have a strong relationship with Miriama from drama-school days, so I knew how to work with her on that.

Once you put a stake in the ground with her, then we go, right, so this is a biracial family, and her sons are going to be Māori and that’s where the Paratene brothers, who are brothers in real life, came into the room, and we were really taken with them immediately. We threw out a lot of their scripted dialogue in the end because what we are casting is that fundamental essence and energy that exists between two real brothers that just speaks volumes more than any dialogue that Eli and I could write.

Matthias Luafutu as Tubs in ‘Coming Home in the Dark’.

What was your approach to the locations? [The area we shot in] is very barren and quite harsh. I spent a lot of time there in my youth, and I find them quite beautiful places. They are very different kinds of landscapes than you normally see in films from our country. We didn’t want to go down The Lord of the Rings route of images from the whenua [land] that are lush mountains and greens and blues, even though that’s what Owen Marshall had written.

I was very keen, along with Matt Henley, our cinematographer, to find that duality in the landscape as well, because the whole story is about that duality in terms of people, in terms of this world, and that grey space. So that’s why we chose to film in those areas.

Regarding the scene where Tubs sprinkles himself with water: including this Māori spiritual element in the film created quite a contrast. That character had partaken in something quite evil, yet still follows a mundane cultural tradition around death. What are your thoughts on that? Yeah. I’m not really interested in black-and-white characters of any kind. I want to find that grey space that allows them to live within more layers in the audience’s mind. So for me—and having family who have spent time in jail, or knowing people who have gone through systems like state-care institutions as well as moving on to prison—just because you have committed a crime or done something in one aspect of your life, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t room and there aren’t other aspects that inform your identity that you also carry.

It’s something that he’s adopted for whatever reasons to ground him in who he is. And they can sit side by side with being involved in some very horrendous actions, but also from Tubs’ perspective, these are actions which are committed in the name of survival. You start to get a sense Mandrake enjoys what he does rather than doing it for just a means to the end. So any moment that you can start to create a greater sense of duality in a person, I think that means that there’s an inner life to a world, to a character, that’s starting to be revealed. That’s an invitation for an audience to lean into that character.

Erik Thomson and Daniel Gillies in ‘Coming Home in the Dark’.

What is the film that made you want to get into filmmaking? The biggest influence on me is probably David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I saw that when I was ten years old. A babysitter, my cousin, rented it. It’s not a film that a ten-year-old should see, by the way. I was in Lower Hutt, there in my aunty’s house, and it was very cold, and there’s a roaring fire going. My cousin and her boyfriend were sitting on a couch behind me, and they started making out. I sort of knew something was going on behind me and not to look. So I was stuck between that and Dennis Hopper huffing nitrous, and this very strange, strange world opening up before me on the television.

I’ve had a few moments like that in my life [where a] film, as well as the circumstance, sort of changed how I view the world. I think something died that day, but obviously something was born. You can see what Lynch did in those early works, especially Blue Velvet. You don’t have to go too far beneath the surface of suburbia or what looks normal and nice and welcoming to find that there’s a complete flip-side. There’s that duality to our world, which we like to think might be far away, but it’s actually closer than you think.

That speaks to Coming Home in the Dark and why that short story resonated with me the first time I read it. Even in the most beautiful, scenically attractive places in our land, many different types of feet walk across those lands, and the land in that sense is quite indifferent to who is on it. I like that duality. I like that sense of we’re never as safe as we would like to think. Blue Velvet holds a special place in my heart.

What other films did you have in mind when forming your approach to Coming Home in the Dark? Straw Dogs, the Peckinpah film. The original. Just because it plays in that grey space. Obviously times have changed, and you read the film in different ways now as you might have when it first came out. But that was a big influence because there was a moral ambiguity to that film; those lines of good and bad or black and white, they don’t apply anymore. It just becomes about what happens when people are put under extreme pressure and duress, and they abandon all sense of morals. The Offence by Sidney Lumet would be another one, very much drawn to that ’70s ilk of American and English filmmaking.

‘Coming Home in the Dark’ was filmed on location around the wider Wellington region of New Zealand.

Is there a New Zealand film that’s influenced you significantly? There’s a few. I remember watching The Lost Tribe when it was on TV. That really scared me. I just remember the sounds of it. Mr. Wrong was a great ghost story. That stuck with me for a long time. The Scarecrow. Once I discovered Patu! [Merata Mita’s landmark documentary about the protests against the apartheid-era South African rugby tour of New Zealand in 1981], that sort of blew everything out of the water, because that was actually my first induction and education that this was something that even occurred. I think I saw that when I was about eighteen. That this was something that occurred in our history and had ramifications that were other than just a rugby game.

And Utu, every time I watch that, it doesn’t lose its resonance. I get something new from it every time. It’s a great amalgamation of identity, culture, of genre, and again, plays in that grey space of accountability. Utu still has that power for me. It’s one of those films, when it’s playing, I’ll end up sitting down and just being glued to the screen.

It’s a timeless classic. I will admit that when I watched your film, The Scarecrow did immediately come to mind, as did Garth Maxwell’s Jack Be Nimble. Yeah. [Jack Be Nimble] was really frightening. Again, it was that clash of many different aspects. There was a psychosexual drama there. You’ve got this telekinetic mind control and that abuse and that hunkering down of an isolated family. There are plenty of New Zealand films that have explored a sort of similar territory. They’re all coming to me now.

Bad Blood has a great sense of atmosphere and photography and the use of soundscape to create that shocking sense of isolation and terror in these quick, fast, brutal moments, which then just sort of are left to ring in the air. But I love so much of New Zealand cinema, especially the stuff from the ’80s.

Kia ora [good luck], James. Kia ora.

Related content

Leo’s Letterboxd list of Aotearoa New Zealand Scary-As Movies Adapted from Literature

Dave’s Cinema of Unease list

A Brutal Stillness: Gregory’s list of patient, meditative genre films

Sailordanae’s list of Indigenous directors of the Americas

Follow Leo on Letterboxd

‘Coming Home in the Dark’ is available now in select US theaters and on VOD in the US and New Zealand. All photographs by Stan Alley / GoldFish Creative. Comments have been edited for length and clarity.

#coming home in the dark#letterboxd#daniel gillies#james ashcroft#maori culture#maori movie#maori director#native director#indigenous film#miriama mcdowell#noir#new zealand noir#leo koziol#imagiNATIVE

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@red--thedragon asked me to post my shin godzilla paper from last semester on here. i don’t want to publicly link to google drive so i’m pasting it in here. sources available upon request.

Godzilla (1954) is famously and somewhat blatantly a metaphor for the atomic bomb. It was also released during what is sometimes called the “Golden Age of Japanese cinema” (Kehr), not all that long after the end of World War II and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Probably not coincidentally, it was wildly successful and left a significant mark on pop culture and consciousness. This paper will focus on the 2016 reboot Shin Godzilla, which takes this well-established nuclear metaphor and ties it instead to the Fukushima disaster of 2011. Shin Godzilla is a darker, less campy piece than we may have come to expect from monster movies. It feels closer to the original Godzilla tonally than most modern takes tend to, and focuses much more on political or bureaucratic drama than on monster fight scenes. It is, however, still very recognizably, and crucially, a Godzilla movie in the spirit of what has come before. This paper will examine how Shin Godzilla invokes Fukushima, what points it is trying to make by this, and how the resignification benefits us--in other words, why what the directors are trying to say needed to be said in specifically a Godzilla movie, already tied by implication to the older nuclear narrative of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The major points of the argument are material parallels to the events of Fukushima in Shin Godzilla, prominent themes of politics and media, and the construction of Godzilla himself. Additionally, one might speculate that Shin Godzilla is about narrative itself, or Godzilla as a narrative.

It is worth commenting briefly on the tagline in connection to the idea that this movie is in some way about narrative. The tagline for the Japanese release of the film is written as both “Japan vs Godzilla” in katakana and “Reality vs Fiction” in kanji, with the katakana above the kanji in a way that implies they are the same word or being equated in some way. Framing the text this way makes it a statement both that this fight is between: (a) Japan and Godzilla, (b) reality and fiction (a narrative), and (c) Japan and fiction (a narrative) (the fourth possible reading, that the film is about a struggle between reality and Godzilla, seems less apt except as an extension of (c)). The English tagline, on the other hand, is “A god incarnate. A city doomed.” This is in line with “standard” Godzilla imagery and is not in itself anything surprising. The fact that the English version is not anything close to a direct translation of the Japanese version is surprising. One might speculate that this is because the “reality vs fiction” concept, with a Godzilla movie, was seen as less meaningful outside of Japan (and thus Western audiences might want something a little more traditional for a monster movie?) Using this kind of wordplay in the tagline is setting us up for a movie that is in some way about signification or meaning; it is also setting up an idea of Godzilla as a cultural construct or narrative, as well as just a monster.

In several places the plot and imagery of Shin Godzilla directly parallel the events of Fukushima. The damage caused by Godzilla manifests in blackouts, airport closures, water (and blood) leaking into train tunnels, and leveled buildings (Shin Godzilla). Like the original, and unsurprisingly for a popular nuclear metaphor, there is a heavy focus here on danger from radiation. However, unlike the original movie, one of the government’s first responses to the discovery that Godzilla is radioactive is “it’s not enough of a spike in radiation to warrant evacuation” (Shin Godzilla). Another major parallel is the focus on mass evacuations, specifically the SDF’s inability to evacuate Tokyo in an organized manner and an increasingly wide area requiring evacuation. The initial suggestion that the disruptions observed might be due to a monster is treated as ridiculous; the more “respectable” politicians tend to assume it must be an underwater volcanic eruption or an earthquake (Shin Godzilla). For comparison, in the original Godzilla the first assumption is that there must be a “drifting sea mine, or an underwater volcano” (Gojira). The underwater volcano idea is repeated in both films, but where the original has a mine (more linked to the aftermath of war), Shin Godzilla has an earthquake (part of the actual Fukushima disaster). Obviously, in the case of the real-life disaster, part of the problem was an earthquake, not a giant monster rising from the sea, but the government’s ignorance of, or refusal to acknowledge, what is going on is evocative. This idea that the government does not know what is happening and cannot be relied upon is repeated in other ways. Scientists working with the bureaucracy initially assume that Godzilla would be unable to support his own weight on land and cannot come ashore; immediately afterwards, he comes ashore (Shin Godzilla).

One of the major themes of the movie is its focus on politics, red tape, and bureaucratic incompetence. This is probably unique to Shin Godzilla within the Godzilla franchise; it certainly does not play such a prominent role in the original. More time in this movie is devoted to scenes of bureaucrats arguing with each other, while Godzilla lays waste to Tokyo, than to any attempt to fight the monster. As in the original Godzilla, the military is powerless to help; unlike the original, this is partly because of red tape (at one point a comment is made that the Self-Defense Forces are not authorized to fight Godzilla because he is not an invading army (Shin Godzilla)), as well as physical inability to stop the monster. Repeated attempts are made to calm the public via press releases and the like, despite the fact that the government is at this point not actually doing anything to help the situation (Shin Godzilla); this speaks for itself. At least one bureaucrat has made a statement that the Fukushima disaster was as bad as it was because of “reflexive obedience...reluctance to question authority...devotion to ‘sticking with the program’” (“Fukushima report”). These are, by and large, the same things being pointed out in the bureaucracy here. Those in power are reluctant to act; there is no protocol for this kind of catastrophe, so no one actually deals with it, except for the characters who are able to disregard protocol and act outside it. One of the final lines is “The fact remains that casualties were high. Accountability comes with the job” (Shin Godzilla). This feels like an unsubtle comment directed at the government--it is a statement that yes, government accountability for what happened is important. Given the rest of the ending (discussed later), and the tonal implications of changing the actual narrative of the aftermath of Fukushima, could this be a way of constructing a scenario in which the Japanese government is held accountable for its failure or inability to act?

Another way politics play an important thematic role is the issue of international relations, specifically between Japan and the US. This plays into some of the statements Shin Godzilla is making about narrative and continuity. It ties less directly to images of Fukushima (the US did intervene in that disaster to some degree, but in a very different way) than the rest of the movie, but is relevant to its ties to Hiroshima. Following the failure of the SDF and government to stop Godzilla, the international community, and, in particular, the United States, attempt to become involved (Shin Godzilla). The US’s idea of how to fix the problem is to drop an atomic bomb on Tokyo to kill Godzilla; much of the conflict is centered around how to stop Godzilla before that happens (Shin Godzilla). There is a line “post-war extends forever” (Shin Godzilla), in a discussion of the political ramifications of the situation. This explicitly links this movie (and thus Fukushima) to what happened in and after World War II.

Another major point distinguishing this from the original Godzilla and tying it to Fukushima and the modern era is the way Shin Godzilla uses media and social media. We see people filming the initial stages of the disaster on cell phones as it is happening (Shin Godzilla), even while the government does not know what is happening and refuses to comment on it. The internet seems to distribute information faster than the bureaucracy. At some points, there is an overlay of social media commentary on the screen, over footage of disaster (Shin Godzilla). Scenes cut between politicians arguing and either the news. This is a mass-information-era take on Godzilla, a modern reinterpretation in ways that go beyond aesthetics or the addition of color. It also suggests parallels to other discourse around Fukushima, notably Ryouichi Wagou’s Twitter poetry.

While the basic concept of the monster and his origins remain similar, there are some notable differences. This Godzilla, like the original, is created by nuclearity in some way; both versions are prehistoric survivors somehow brought into contact with humans by nuclear weapons or nuclear energy. However, the original Godzilla was created by nuclear testing in the Pacific (Godzilla), while Shin Godzilla evolved rapidly to feed on nuclear waste following unregulated dumping (Shin Godzilla). It is worthy of note that this Godzilla also must periodically reenter the sea to cool his internal nuclear reactor (Shin Godzilla). Additionally, he is eventually stopped by exploiting this need for temperature control. The need for cooling, and specifically cooling by seawater, seems to be referencing the actual means by which meltdown is contained.

There are significant visual differences between the Shin Godzilla take on Godzilla and more traditional depictions. Some of this is attributable to improved special effects, but not all (this Godzilla does not look much more like other contemporary depictions of Godzilla than he does like the original). The most significant change is the theme of mutation and multiple forms, discussed in more detail later. All his forms look somewhat unlike more traditional versions of Godzilla; the second in particular is notably unsettling-looking, resembling a gilled sea animal barely able to move on land and who routinely dumps blood from his gills, while the third and fourth can, unlike the original Godzilla, unhinge their jaws. It is likely that these differences are related to a commentary on narrative, and drawing a contrast with the other ways Godzilla has been reinterpreted over the years. We have become used to the “traditional” Godzilla, in a way people in the 50’s would not have been. Because he is such a fixture of pop culture, the image of Godzilla no longer provokes fear. A new version is better able to provoke a visceral reaction, as well as to indicate that this is not, for all its similarities, quite the same narrative, or the same disaster, but something new, something we should be afraid of. Additionally, the way Godzilla looks has always been some kind of radiation metaphor (for instance, the original Godzilla’s scale patterns resemble scars from radiation poisoning). Is the unsettling appearance and seeming injury here part of the same idea? Are we meant to take the monster leaking blood from his gills as a form of radiation sickness? Is the monster, too, now suffering from the disaster? This could be an interesting reinterpretation of the monster-as-nuclear-metaphor narrative; it would require more space to analyze fully than is available here, but is worth mentioning.

Perhaps the most significant difference between Shin Godzilla’s take on the titular monster and any older material is the idea of mutation. This Godzilla can rewrite his own DNA and take new forms to adapt to new circumstances. While all five forms are recognizably distinct from any other take on Godzilla, the first two in particular look nothing like any other depiction. As the crisis gets worse, he mutates gradually into something much closer to the recognized nuclear symbol that truly ties this to what’s come before. This can be taken as saying essentially, “this started out looking like a brand-new problem, but now we see it is the same pattern repeated.” As for the mutation itself, there is the obvious connection between radiation and mutation. Also, by mutating, Godzilla can adapt to his circumstances and survive, but the government status quo cannot. There is also plausibly a link between the significance of mutation within the film to a commentary on changing narratives themselves: narratives of disaster, the “Godzilla narrative.” Even the title of the film, which literally translates as “New Godzilla,” backs this idea of change. Calling it simply Godzilla (2016) would have been in keeping with the norms of the franchise. The choice to call it “New Godzilla” instead suggests that the creators are deliberately framing this film as a shift in the narrative of disaster (and of Godzilla movies) they are using, even though thematically, tonally, and in terms of actual plot, Shin Godzilla is closer to Godzilla (1954) than many of the newer movies that might bear the name “Godzilla.”

The last major element that merits discussion here is the tone of the ending. Shin Godzilla ends slightly differently from the original Godzilla; while the original Godzilla is eventually killed, with concerns that if nuclear testing continues another Godzilla will rise (Godzilla), Shin Godzilla is only frozen, not killed (Shin Godzilla). The idea that the threat is still there, cooled beyond the capacity to act, immobilized, but ready to start moving again, reads as a parallel to the need for continual efforts to contain radioactive leakage. However, it is established that if he starts moving again, the countdown to annihilation from nuclear weapons will also start again (Shin Godzilla). This raises the question of whether that element is really about Fukushima. On the one hand, containment of a meltdown would have the “constant threat that this will become an active problem again” element. On the other, that significance would already be covered by the idea that Godzilla is frozen, not dead; bringing in US involvement, and specifically the threat of nuclear weapons, suggests something else is being referenced here. You cannot talk about dropping an atomic bomb on Japan without invoking Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The ending, while not happy by any means, does have an oddly hopeful tone. Scientists discover that a new radioactive isotope associated with Godzilla has a half-life of only 20 days, and will disappear completely in at most 3 years (Shin Godzilla). This stands in sharp contrast to how we normally think of radioactive contamination, and, significantly, to the actual timescale of Fukushima. As of March of this year, eight years after the original disaster, containment and cleanup efforts were still underway, including difficulties in storing or disposing of contaminated water (Takahashi). The choice to have the radiation go away suggests that there is an “after” for this disaster, when the damage will truly be over and Tokyo will be safe again, in the same way Shin Godzilla elsewhere implies there is not truly an “after” for Hiroshima. This time, reality, or Japan, wins over the narrative. At the same time, changing the real narrative of what happened at Fukushima, and is still, in a way, happening, to one with a happier, more certain end could be taken as narrative winning out over reality. Thus, this question is both answered and unanswered. The same idea of a true post-disaster space is suggested by the prospect of a new set of politicians, who may be less paralyzed by protocol in the face of catastrophe. Ending the movie this way seems to be a means of coping with the disaster, of reanalyzing it as something that can be defeated and truly go away, in a way the reality of nuclear catastrophe cannot.

There is one more minor point relevant to this interpretation. Shin Godzilla was very well-received in Japan, winning 7 Japan Academy Prize awards (Dominguez), but received a much more mixed response in the West (Bellach). Much of the criticism focuses on the movie being boring, confusing, or too heavily focused on the bureaucratic elements. This difference can likely be attributed to two major factors. First, we may have certain expectations for monster movies; as mentioned above, while the original Godzilla was quite depressing, the tendency over the years has been more towards campier, more monster-fight-focused action movies. Evaluated in that genre, Shin Godzilla definitely does not meet expectations. Second, the Fukushima disaster itself, and the government’s response or failure to respond, are likely much more active in people’s minds in Japan. Western critics might not even be aware of some of the details, and would be less likely to have a strong reaction to the parallels than someone who had seen the impact more up-close.

Shin Godzilla is at once a criticism of the Japanese government’s response to the Fukushima disaster, a means of placing Fukushima as part of the same cultural legacy as Hiroshima, a means of coping with the aftermath of Fukushima, and a commentary on the narrative of disaster itself and other Godzilla movies, all, crucially, dressed up as a Godzilla movie. While the primary point here seems to be using the format of a Godzilla movie to critique Fukushima, it is important that this is a Godzilla movie. There is work being done by the images of Hiroshima inherently referenced by this comparison that would not be filled by a new, Fukushima-specific monster, let alone a realistic disaster movie. The same point is being made by explicit references to the atomic bombing of Japan, and the idea that we are still in the “time after” or “aftermath” of Hiroshima. This is both an attempt to process that idea and to cement Fukushima as a continuation of the same narrative. However, the narrative is not set in stone; we are using a rigid narrative to talk about continuation, but the need for change is a major theme, and Japan wins over the "narrative,” if only barely. Changing the way the disaster ends is both a criticism of how the government actually responded to Fukushima and a means of coping with Fukushima, or suggesting hope for the future. Additionally, there are suggestions of commentary on how Godzilla has evolved as a concept that are difficult to separate from the political commentary; this gives an overall impression that in some ways, this is a movie about narratives as much as anything else.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Santorini: The exact image you have in your head of a Greek Isle

This was probably my favorite part of our trip to Greece. We stayed at the Villa Costa Marina, a small B&B in the town of Fira (Latin spelling varies) run by an awesome 30-something and her friend. Maria’s family seemingly has run inns for ages, they also own the Pelicanos Kipos restaurant up the street, and basically, they know what they’re doing.

Orientation

Once a round island, Santorini is now shaped like a sliver of a crescent moon due to a volcanic eruption. The inside of the crescent features steep cliffs with whitewashed houses and churches clinging to the edges. The outside of the crescent falls towards the sea more gradually, and most of the beaches (and farms) can be found here.

Fira is the main city, and is located on the eastern (inside of crescent) side of the island. Oia, a town famous for sunsets, is on the Northern tip of the crescent. Beaches and archeological sites are generally found to the south.

Sights/Activities

The original crater is still active, and you can take a boat tour there. To get to the pier, you can either walk down the hill which includes many stairs and spectacular views (I ran down because I was late for the boat), ride a donkey (probably a cool experience for some people but be warned, the donkeys are excruciatingly slow and kind of smelly), or take the funicular (fastest, we did this on the way up). There are several boat tours available. We opted for a half-day tour in a cool old boat that included an opportunity to swim to the volcanic hot springs. The tour included a guided hike up to the top of the crater that took our group about 30-45 min. Our group was pretty large and included slow walkers like my parents; I probably could have summited in under 15 min without breaking a sweat. The hike to the volcano caldera is all rock (mostly red, some yellow or black) and there are several spots at the top where you can see smoke coming out. There is NO SHADE, so it gets super hot. Bring an umbrella (yes, for the sun). We probably spent 1.5 hours on the volcano crater before going back to the boat.

Reaching the hot springs, we were allowed to jump off the deck of the boat. The water was freezing, which made me swim faster to reach the springs, which, sadly were only warm and not hot (apparently this is seasonal). I definitely swam hard back to the boat knowing that the cold water was coming.

After the tour, I opted to do a 10km hike from Fira to Oia for the sunset. The walk was amazing: generally you travel along the edge of a cliff with views of the sea the whole way. There’s a bit of countryside, some farm navigation, and some old churches and shrines to explore.

Oia is a cool town which merited more time than I gave it. It has smooth, wide stone sidewalks, more whitewashed buildings clinging to cliffsides, cute shops (especially art shops), a wide variety of restaurants, and, of course, breathtaking sunsets. The best place to see the sunset is at the Northern tip of the crescent – basically just keep walking in the direction you were hiking until you can’t anymore. If it’s around sunset, they’ll be lots of people there. There’s a castle thing you can climb for a better view. Buses back were plentiful and popular. I was a bit scared when the last scheduled bus, packed to the gills, left the station before I could get on it, but not to worry, there were more buses coming to take the rest of the people waiting.

The next day, while my parents took a guided tour around the island, I opted to take the city bus to some attractions. The city of Akrotiri was buried 3800 years ago by volcanic eruption, and is now an archaeological site enclosed by an impressive building. Not taking the tour saved me the money I needed for entrance, which was not cheap, but it was worth it. The site includes several ancient buildings, some of which you can walk through, as well as some pottery. Signage is in English and pretty good, plus you can always follow one of the guided tour groups around to learn more. The most historically interesting fact (to me) was that Akrotiri was a peaceful city, there was no evidence of weapons or war, just trade. It appears to have been abandoned before the volcano destroyed it, because there were no bodies found buried alive (not like they were in Pompeii).

Santorini isn’t known for its beaches, but there are actually a couple nice ones. Located a short (but technical) walk from the Akrotiri site, the red beach is a smallish semi-circle of coarse reddish-brown sand backed by a high cliff. Though well-known, the beach was uncrowded when we were there (early May) and did not have the typical European 10,000 beach chairs and umbrellas. There’s a juice stand at the entrance to the hike.

As I was standing at the bus stop waiting to go back to town, Maria and Steve, a young couple from California that we’d met on our tour in Athens happened to drive by in their rental car, and I tagged along to their next destination, the black beach. Much bigger than the red beach, the black beach sits on the southeastern side of the crescent of Santorini, far from the cliffs of Oia. Though it was uncrowded in offseason, this is the beach that clearly becomes the land of 10,000 chairs and umbrellas full of probably topless sunbathers in the summer. As it was, we had some mezze at one of the beachside restaurants and a couple beers in the chairs. We were the only ones there.

That night, Maria and Steve and I followed Lila, the girl who worked at our inn, to experience some Santorini nightlife. I couldn’t tell you where we went, but being the off season it was pretty chill. You can see how it would heat up in season, but I doubt it gets crazy like Mikonos, as the vibe is a bit older (more 30-somethings)

Finally, there is a fish pedicure place called Fish Spa. They have free WiFi and offer a 2nd fish pedicure for free if you come back within a certain amount of time. I’d wanted to get a fish pedicure before (mainly, in Cozumel) but they don’t have them in the US because of PETA or something, so I was super excited. And my feet were so soft afterwards. I totally want to do it again.

Food

Pelican Kipos restaurant is owned by Maria’s family and includes an extensive wine cellar. Everything we ate was delicious. A highlight for me was the tomato fritters. They also have a wine tour featuring local cheeses, which I would love to do next time. Generally I found the food in Santorini to be much more reasonably priced than in Mikonos. Anyway, everything we got was delicious and you should go there.

Other than that, there weren’t any places that really stood out in terms of deliciousness. There several restaurants in downtown Fira that offer decks with western exposure, and it’s worth it to get a spot by the railing around sunset (or earlier). One of the Santorini specialties is fried tomatoes, which obviously I couldn’t get enough of.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Secret Origin of Halloweentown Revealed: How a Little Girl Inspired a Beloved Franchise

New Post has been published on https://gossip.network/the-secret-origin-of-halloweentown-revealed-how-a-little-girl-inspired-a-beloved-franchise/

The Secret Origin of Halloweentown Revealed: How a Little Girl Inspired a Beloved Franchise

For almost 20 years, Halloweentown has been an annual destination for many people.

The cult favorite Disney Channel Original Movie first debuted in 1998, introducing a world most kids (OK, and adults) can only dream of: Halloweentown, the whimsical place where all the supernatural creatures live every other day of the year. Four movies later, the Halloweentown franchise is one of the most beloved seasonal offerings, with fans even flocking to the town of St. Helens, Oregon, where the first movie was filmed, to live out their childhood fantasy. (Consider it the original Hogwarts.)

E! News spoke to executive producer Sheri Singer and star Kimberly J. Brown about the film’s legacy, the controversial recasting of Marnie in the fourth film and the magic of Debbie Reynolds, the legendary star who played Grandma Aggie.

Sheri Singer first heard of Halloweentown when she was an executive at Walt Disney Television just after the Wonderful World of Disney programming had ended in 1991, transitioning into a six-movie deal with NBC. As part of that new deal, she was set to collaborate on up to three movies with producer Steve White, and wanting to spread out the projects to other people, she tried to convince him to duck out of the deal. He almost did, but then decided not to at the last minute. Then…fate stepped in.

Singer: What ended up happening to the man that I had tried to fire was I married him. And toward the end of my time at Walt Disney Studios, he came in one day to me and said…”I don’t know where to go with this but my daughter said to me, ‘Dad, where do all the creatures from Halloween go the rest of the year when it’s not October 31?'” And that’s how it was born.

After dubbing it Halloweentown and coming up with a seven-act structure, Singer and White pitched the project to NBC as part of the six-movie deal.

Singer: It had to have a little bit more adult appeal because they were airing these movies at 9 o’clock at night. [NBC] bought it, we developed it in 1994, and we had a writer write the script, and NBC passed. They decided they didn’t really want to do anything, even though we put in adult characters.

A few years later, they brought it to Disney Channel, who initially passed. But after airing their first successful original movie in 1997, Under Wraps, they wanted Halloweentown after all. The movie was quickly redeveloped so that it was more of a kids’ movie. Singer: Doing it at the Disney Channel, which was really the best possible home for the idea, we were able to be very whimsical. We needed to create these really interesting characters. They were fun and slightly scary, but not too scary.

After getting the go-ahead from Disney Channel, casting began. First up, legendary star Debbie Reynolds. Singer: I think right about this time, Debbie had decided she wanted to open herself up to doing some television. When we saw the list, we took one look at her name and said, oh my god, would she really do it? This is absolutely unbelievably blessed and terrific idea for casting. And she did. We never went to anyone else.

When it came to the rest of the roles, the casting directors read everybody, from the leads to characters with only one line, as the Disney Channel had yet to establish a field of talent to pull from. A 13-year-old Kimberly J. Brown eventually landed the lead role of Marnie.

Singer: She came in and she wasn’t who we had visually pictured, but she was the role. She blew everyone else away. She was great.

Brown: It was so exciting when I found out I got it because I remember loving the script and loving the idea of playing a teenage witch. And then hearing Debbie Reynolds was signed onto it, it was like, oh my gosh, I’m going to play Debbie Reynolds’ granddaughter!

Singer: Debbie was coming in with the blonde look and Judith [Hoag] was reddish blonde, so I thought it would maybe be a lighter girl. Of course, this is so politically incorrect today, but they were all related…I had just envisioned a Blondie. But she came in and she was it.

The role of Kalabar, the mayor-turned-villain, was the hardest to cast, as he had to be scary-but-Disney-Channel-scary. Robin Thomas, who had worked with White on an indie film, Amityville Dollhouse, was cast.

Singer: Of all the actors I’ve worked with in my life, he’s in the top five of doing his homework and really prepares. There was a lot of discussion about how do we do this. I think part of what we did…in his role as the mayor, he was more charming and likable, so that the audience would get used to him not being that scary so when he was, he really was.

To create Halloweentown, production chose a small town, St. Helens, outside of Portland, Oregon. In 1980, Mount St. Helen erupted, and was one of the most disastrous volcanic eruptions in U.S. history.

Singer: Because of the volcano from a few years before that, it was kind of a ghost town. In terms of making the store fronts and getting the location and making a huge town square, there’s not a lot of places in LA you can do that. They were so grateful to have us there and so easy to work with. We had a good crew up there and it fit the demands of the movie. We made all these storefronts. It was really fun and became very iconic.

Disney Channel was heavily involved in establishing the look of the town. “Whimsical” was the goal and the big pumpkin in the town square was always the focal point.

Singer: It needs to almost look like a Disney ride for young kids. One of the nice things about doing something for Disney is you know there are certain tent poles and goals you want to reach in terms of giving kids a lot of eye candy that’s appropriate for their age and is sort of wish-fulfillment.

Brown: The town square really did feel like Halloweentown. I enjoyed the hell out of it.

The costumes were also a major part of the process, with some of the cast members even keeping their wardrobe to use for Halloween. Brown: I have Marnie’s outfit from the second Halloweentown. Debbie gave me the idea, but she had Aggie’s cape and the purple dress and she used to answer the door for Trick-or-Treaters on Halloween in the outfit. I started doing it, too, one or two years in a row, I put on Marnie’s outfit, and gave out candy. It would take some kids a second, but it was really fun. But then it started getting out of hand where some people would come other parts of the year, knock on the door and ask for Marnie.

Working with Reynolds, who passed away in December 2016, just one day after her daughter Carrie Fisher died, was a memorable experience for everyone on set. Singer: We were doing this scene in a theater…and Debbie had to dance and she pulled a muscle doing the dance. She got up and she said, “You know what, I’ve been doing this for years and years. I’ve dance with pulled muscles and pain and I’m not going to hold you up. I’ll do it.” It was so impressive for the young actors, to see what a real work ethic is. Obviously, she went on for the rest of the show and was fine, but it was very interesting and everyone was applauding.

Brown: I just remember how incredibly warm and vivacious she was and very welcoming. She was just so sweet and trying to make us laugh and just very excited. Her energy was infectious. She treated as us peers and not just like, “You’re the kids.” She wanted everyone to shine and succeed and it was so inspiring to watch.

Singer: Debbie Reynolds…started telling us, she had a granddaughter at the time, who’s Billie Lourd, and she said that put her on the map with her granddaughter and all of her granddaughter’s friends and she started getting stopped in airports and all over the place.

Disney Channel

In the fourth and final installment of the franchise, 2006’s Return to Halloweentown, the role of a college-bound Marnie was played by Sara Paxton.

Brown: I’ve been in the entertainment industry since I was five or six years old and there have been many, many things along the way that have come and just been things that have happened and decisions that are out of your control. That was one of those things where they chose to use somebody else instead of me. I was definitely disappointed for the fans and a little personally disappointed because I love Marnie and have loved being able to participate in her adventures as much as people have seemed to love watching her go through them.

Singer: It was not something we wanted to do. We could not come to terms that we felt were fair. We just weren’t able to. We couldn’t make the deal work. That was why and we didn’t want to not do it. I know people didn’t like it, but it’s not like people haven’t been recast before. I always was sorry. That’s how it went.

Brown: I can’t say that I’ve seen the entire movie…but I do appreciate over the years how much the fans have continued to make memes about it and just really want to talk about it and support me in that sense. It’s been very touching over the years.

facebook.com/Halloweentown.OR

Halloweentown lives on in St. Helens. The town dedicates the month of October to the film. In 2015, media outlets picked up on the tradition, letting fans know they could visit Halloweentown. (The first Twilight film also filmed in St. Helens.)

Crystal Farnsworth, communications office for the City of St. Helens: The festival first started in 1998 to celebrate the release of Halloweentown. With the exception of a few years when a lack of funding and volunteers meant that no celebration occurred, the festival has happened every year since then.

Brown: It spread like wildfire [in 2015]…they ended up calling me and that was the year 15,000 people showed up. It was incredible.

. It was the first time the core cast members of the family have been together since I believe we did Halloweentown High. That was their first time back in St. Helens, so that was really cool. We all keep it touch over social media, but it was the first time all of us were together and it was really nice.

Farnsworth: Not only do we see tens of thousands of extra people in the city during the month of October, but we also have people who travel here at other times of the month to see the filming locations. We have people that show up all year long looking for the giant pumpkin in the Plaza Square (although we only put him out during the month of October). We start getting calls at City Hall in the early spring from people wanting to know what events are happening which weekend in October because they are already trying to plan their trip to Spirit of Halloweentown for the fall. We estimate that this year, we will have had around 40,000–50,000 people attend the festival during October 2017.

The original cast of Piper-Cromwells, including Brown, Hoag, J. Paul Zimmerman, and Emily Roeske, reunited at 2017’s Spirit of Halloweentown festival on Oct. 14.

Brown: It was the first time the core cast members of the family have been together since I believe we did Halloweentown High. That was their first time back in St. Helens, so that was really cool. We all keep it touch over social media, but it was the first time all of us were together and it was really nice. It was nice to go back and honor Debbie. It’s such an honor that people want to come and hang out and see where it was filmed. Never in my wildest dreams could I have imagined this is what we would be doing.

Singer: I realized [Halloweentown] was just one of those things that spoke on so many levels. Beside just the holiday theme, it was about family, and family connections and family secrets and allowing kids to be themselves and come into their own. It just had many, many themes that at the time did not feel overused or seen too many times. When you’re making a movie and you’re post-producing a movie, you get so sick of looking at the movie. I never got tired of seeing the movie.

Source link

0 notes

Text

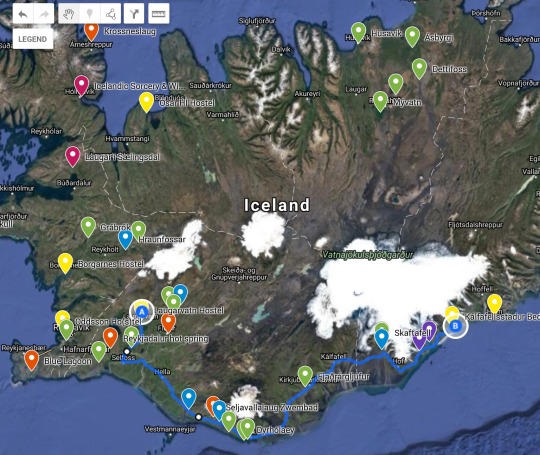

Day 5 - Kálfafellsstaður - 13th August

We had an enormous itinerary planned today, with so many things we wanted to see on the south-eastern side of the country. Unfortunately the only available accommodation was over 6 hours drive away along the ring road. I snatched it up over a month in advance and it was a quaint bed and breakfast for $220 for the night - a little steeper than the $70 we had been paying for everywhere else but I thought it was a slightly better idea than Matthew's suggestion of sleeping in the car. Aside from having a massive drive ahead of us, we were going to try our hardest to still see everything we wanted to, so woke up at the crack of dawn, filled our struggling tyre with air (and said a little prayer) and then excitedly set off. First was a quick petrol and coffee stop at Selfoss, an area we had become very familiar with over the past couple of days, and then further on to new pastures. After a short while we made it to our first waterfall for the day, Seljalandsfoss, which billows out from the overhanging rock face. It was quite chilly this morning and the spray from the falls didn't help, but it was worth it to be able to view the world from behind an Icelandic waterfall.

About 800 metres down the track, past groups of tents filled with travellers just stirring, was a second unique waterfall, Gljúfurárfoss, hidden amongst a narrow chasm. Matthew climbed the steep and slippery rocky incline to get a view from the top, whereas I was happy to appreciate it from ground level. Somehow again once he started the climb a whole group of copy cat people seemed to appear out of nowhere to make the climb.

With no time to lose we were back on the road again. It hadn't been long when we came across the viewing area and visitor centre for Eyjafjallajökull, the volcano that erupted back in 2010 and basically put Iceland on the map. If you didn't know what to look for you would easily miss it, just a mound off in the distance overshadowed by higher peaks. It caused a heck of a lot of chaos for such an unassuming little mound. Anyway it was something to tick off the list before heading on to check out the Selvajallaug thermal Pool, which was something I had been excited to check out after seeing it on Instagram making for really unique photos. I don't think it's as well know by tourists, especially being about 15 minutes down a side road and then another 15 minute hike away. The pool is Iceland's oldest manmade pool and was originally built in 1928 In order to teach locals to swim. It just happens to be in the most picturesque location - even just the beautiful and lush mist covered valley was worth seeing in itself. Unfortunately we just didn't have the time to go for a dip, but spent a bit of time observing those who did.

Matthew took a bit of a tumble while we were exploring the valley, so washed the mud off his sleeve in the luke warm waters of the river.

Back on the ring road and a little further down was Skogafoss, arguably the most popular and photographed waterfall in Iceland. The area was very equipped for tourists with a huge car park, tourist centre and restaurants. We were competing with other tourists to get as close as possible in order to have an unobstructed view. We also climbed the many stairs and observed from the top.

I get now why they call them ‘rock faces’, because I couldn't help but seeing mystical rock covered faces poking out everywhere we went.

An Asian tourist watched me take this photo and she thought it looked so nice that she asked me to take the same of her on her big high tech Canon camera. We thought she must have been a solo traveller...but then a few of her large group of friends jumped into the shot. She was obviously just very impressed with my photography prowess.

Next stop down the road was Solheimajokull (glacier), where we ignored the sign saying you must wear a helmet to get close, and walked to the foot and marvelled at its sheer size and majesty. We also had a bit of fun skimming volcanic rocks into the lake that it met, something you don't get to do everyday.

By this time we were feeling pretty famished and ready for lunch but decided to push on and see just one more thing before stopping for lunch. Little did we know, the next activity would be extremely long and arduous. Again it was an Instagram find, possibly not so much on the main tourist plan these days as it takes a little to get to (which I hadn't realised). I couldn't possibly not see this though, as the photos I had seen were so unique and eerie looking. I kept it as a surprise to Matthew, so he had no expectations.

The DC-3 plane crash is not sign posted, but I had worked out a general idea of its location and once we saw numerous cars parked together on the side of the road we decided it must be the spot. Little did we know it was then a 4km walk away down essentially a flat, barren black sand desert. Looking in front, we could see nothing but the blue sky and tiny ant-like people walking towards us from who knows how far away. Behind us were only the main road and an escarpment of mountains. It was just dead flat and the sun was blaring down on us and it just felt so long. I'm still not sure whether once we got there we were actually looking at the plane crash or it was just a mirage. Still, it was so worth it.

We couldn't have been more excited to eat our sandwiches by the time we got back to the car, but we wanted to do them justice by enjoying them in a more scenic location rather than the side of the road, so we decided to drive the half hour or so to our next attraction, Dyrhólaey, and the area of the famous black sand beach. We enjoyed our lunch in the comfort of the car, whilst listening to the Les Miserables soundtrack, and then went exploring, with the area being the perfect setting for peering out to sea. We stood for a long while on the rocks and took it all in. I was intently watching a solo little sea lion who was popping it's head out of the raging sea at regular intervals. I was also looking out for puffins, but there were none to be seen unfortunately. All the while I was still struggling to believe I was in this part of the world.

The hours were getting away from us, so we were back on the road and ready for the home stretch. We had about 2.5 hours more driving ahead of us and a couple of final stops. We went through the cute seaside town, Vik, which we had been hoping to stay at and sad we couldn't spend more time exploring. Then it was a quick stop at some moss covered lava fields and then Fjaðrárgljúfur- a beautiful, picturesque, kind of fairytale-like mossy canyon.

The final drive up the bottom of the east coast of Iceland to our final destination was the most amazing drive I have ever done. On our right was black sand beaches, the flat sea and then standalone rock platforms jutting out which thousands of years ago were part of the mainland. On our left were snow capped mountains and glaciers. We went around a bend and had two almost symmetrical glaciers staring at us. So incredible.

We made a quick stop at the glacier lagoon, Jökulsárlón, and the bright afternoon light was just hitting it perfectly. There is a bridge going over the part where the lagoon meets the sea, and I think we drove over that bridge about 8 or 10 times over the next 24 hours, because of the various activities we were undertaking. I also had the most incredible toilet stop a little way down the road with a giant glacier as a backdrop.

This is me being proud of our little car for being a trooper so far.

I stupidly hadn't mapped where we were staying that night, I only had a general idea. We got to the little 'township' which was actually just a few farmhouses, a tiny stone church and an Inn which was clearly overbooked and buzzing with activity with numerous motor homes out the front. We assumed the Inn was where we were staying, as there were no other options, so Matthew stayed in the car while I went in to check. It looked so dingy and I walked straight into the kitchen, which looked like an absolute mess hall. I was starting to get really worried, which turned into panic when the receptionist said I didn't have a booking and there was nothing available. I went back out to Matthew feeling defeated, but we decided to drive around to the back of one last place, which just looked like a farmhouse. Luckily it had a tiny little sign, Kálfafellsstaður, and I could not have been more relieved. The owner greeted us with a kind smile as soon as we walked in the door, and we were taken to our quaint, clean, warm, nice smelling room with a view onto the lush green lawn and church. Just what we needed after an overwhelmingly massive day.

But it wasn't time to relax yet! We had half an hour or so for quick eats and a rest before we were off again on the 45 minute journey back to the glacier lagoon. We were lucky enough to be in this part of the world on the night of the annual charity fireworks event. What a treat. There was a great crowd of what seemed like mostly locals and I liked how the volunteers were carrying eftpos machines so we could pay the 1000 kronas on card - you don't often get that in Australia. It was also amusing seeing the person frantically whizzing along on his little boat manually lighting each firework. It was all so incredibly magical though seeing the lagoon and its icebergs lit up and a very fitting end to one of the best days of my life.

0 notes