#some slave owners promised their slaves freedom if they fought as patriots in the war only to enslave them after the war

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#random wikipedia articles#wikipedia#us history#US revolutionary war#black history month#20000 African Americans joined the British army#9000 African Americans joined the American army#Dunmore’s Proclamation promised freedom to any slave who joined the British cause#Crispus Attucks was an African American who was killed during the Boston massacre#some slave owners promised their slaves freedom if they fought as patriots in the war only to enslave them after the war#many black men were minutemen before the war started#many African Americans joined as patriots thinking they would be free or get more rights after the war#there was a significant amount of Black captains policing ships for the patriots#some revolutionary leaders were afraid that black soldiers would start slave rebellions#somerset vs steward was a British Cort cause that helped further the British anti slave movement#somerset vs steward threatened slave owning practices in the colonies and was part of the reason people fought the British#Rhode Island struggled to enlist patriot soldiers so they offered to free any slave who joined and to compensate their owners#140 black men joined the 1st Rhode Island Regiment#many black loyalists left America enslaved with their slave masters#George Washington ordered all black men fighting for the British to be held and returned to their slave owners#book of negroes#the book of negroes was a registers of Black soldiers who fought for the British#if accepted into the Book of Negroes the person would be transported out of New York and to Nova Scotia#the book of Negro contained roughly 3000 names 750 names were of children#some people who were evacuated to Canada went to Africa to escape discrimination#in 1792 the us army formally banned African Americans from military service#in 1789 free black men could vote in five of the thirteen states

0 notes

Text

The Forgotten Fifth

I started this post years ago, but unfortunately since have lost many of my notes. Still, at this time (and the day after Juneteenth) I think it’s critical that we understand that Black Americans have been here since the beginning, have advocated for themselves, and have fought for themselves. Our inability to “see” Blacks in American history means we don’t understand why Native American slaughter and Westward expansion happened, we discuss the goals of the antebellum “South” as though 4 million Blacks did not live there (and comprised nearly 50% of the population in some states), we rarely bring forward the consequences of the self-emancipation of enslaved Blacks on the Confederate economy, and so on.

It’s also critical to reject false historical narratives that place white Americans as white saviors rescuing Blacks. Within the Hamilton fandom, there is a strong white supremacist narrative embedded in the praise for John Laurens*, an individual who could not be bothered to ensure the enslaved men with him were properly clothed - which says more about his attitude towards Blacks than any high language way he could write about them as an abstraction. And if we want to praise a white person for playing a big role in encouraging the emancipation of Blacks during the American Revolution, the praise should go to the Loyalist Lord Dunmore in that roundabout way.

The Forgotten Fifth is the title of Harvard historian Gary B. Nash’s book, and refers to the 400,000 people of African descent in the North American colonies at the time of the Declaration of Independence, one-fifth of the total population. Unlike commonly depicted, Blacks in the colonies were not waiting around for freedom to be given to them, or to assume a place as equals in the new Republic. Enslaved Blacks seized opportunities for freedom, they questioned and wrote tracts asking what the Declaration of Independence meant for them, they organized themselves. And they chose what side to fight on depending on the best offers for their freedom. At Yorktown in 1781, Blacks may have comprised a quarter of the American army.

Most of what’s below is taken from wikipedia, other parts are taken from sources I have misplaced - the work is not my own.

In May 1775, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety enrolled slaves in the armies of the colony. The action was adopted by the Continental Congress when they took over the Patriot Army. But Horatio Gates in July 1775 issued an order to recruiters, ordering them not to enroll "any deserter from the Ministerial army, nor any stroller, negro or vagabond. . ." in the Continental Army.[11] Most blacks were integrated into existing military units, but some segregated units were formed.

In November 1775, Virginia’s royal governor, John Murray, 4th early of Dunmore, declared VA in a state of rebellion, placed it under martial law, and offered freedom to enslaved persons and bonded servants of patriot sympathizers if they were willing to fight for the British. Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment consisted of about 300 enslaved men.

in December 1775, Washington wrote a letter to Colonel Henry Lee III, stating that success in the war would come to whatever side could arm the blacks the fastest.[15] Washington issued orders to the recruiters to reenlist the free blacks who had already served in the army; he worried that some of these soldiers might cross over to the British side.

Congress in 1776 agreed with Washington and authorized re-enlistment of free blacks who had already served. Patriots in South Carolina and Georgia resisted enlisting slaves as armed soldiers. African Americans from northern units were generally assigned to fight in southern battles. In some Southern states, southern black slaves substituted for their masters in Patriot service

In 1778, Rhode Island was having trouble recruiting enough white men to meet the troop quotas set by the Continental Congress. The Rhode Island Assembly decided to adopt a suggestion by General Varnum and enlist slaves in 1st Rhode Island Regiment.[16] Varnum had raised the idea in a letter to George Washington, who forwarded the letter to the governor of Rhode Island. On February 14, 1778, the Rhode Island Assembly voted to allow the enlistment of "every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave" who chose to do so, and that "every slave so enlisting shall, upon his passing muster before Colonel Christopher Greene, be immediately discharged from the service of his master or mistress, and be absolutely free...."[17] The owners of slaves who enlisted were to be compensated by the Assembly in an amount equal to the market value of the slave.

A total of 88 slaves enlisted in the regiment over the next four months, joined by some free blacks. The regiment eventually totaled about 225 men; probably fewer than 140 were blacks.[18] The 1st Rhode Island Regiment became the only regiment of the Continental Army to have segregated companies of black soldiers.

Under Colonel Greene, the regiment fought in the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. The regiment played a fairly minor but still-praised role in the battle. Its casualties were three killed, nine wounded, and eleven missing.[19]

Like most of the Continental Army, the regiment saw little action over the next few years, as the focus of the war had shifted to the south. In 1781, Greene and several of his black soldiers were killed in a skirmish with Loyalists. Greene's body was mutilated by the Loyalists, apparently as punishment for having led black soldiers against them.

The British promised freedom to slaves who left rebels to side with the British. In New York City, which the British occupied, thousands of refugee slaves had migrated there to gain freedom. The British created a registry of escaped slaves, called the Book of Negroes. The registry included details of their enslavement, escape, and service to the British. If accepted, the former slave received a certificate entitling transport out of New York. By the time the Book of Negroes was closed, it had the names of 1336 men, 914 women, and 750 children, who were resettled in Nova Scotia. They were known in Canada as Black Loyalists. Sixty-five percent of those evacuated were from the South. About 200 former slaves were taken to London with British forces as free people. Some of these former slaves were eventually sent to form Freetown in Sierra Leone.

The African-American Patriots who served the Continental Army found that the postwar military held no rewards for them. It was much reduced in size, and state legislatures such as Connecticut and Massachusetts in 1784 and 1785, respectively, banned all blacks, free or slave, from military service. Southern states also banned all slaves from their militias. North Carolina was among the states that allowed free people of color to serve in their militias and bear arms until the 1830s. In 1792, the United States Congress formally excluded African Americans from military service, allowing only "free able-bodied white male citizens" to serve.[22]

At the time of the ratification of the Constitution in 1789, free black men could vote in five of the thirteen states, including North Carolina. That demonstrated that they were considered citizens not only of their states but of the United States.

Here’s another general resource: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2narr4.html

*The hyper-focus on John Laurens is one of the ways white people in the Hamilton fandom tell on themselves - they center a narrative about freedom for Blacks around a white man (no story is important unless white people can stick themselves at the center of it, no matter how historically inaccurate!). Lord Dunmore’s 1775 proclamation, if known, is seen just as cynically politically smart, while Laurens’ vision is seen as somehow noble.

**Whether Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation - encouraging enslaved Blacks to rise up and kill their owners and join the Loyalist cause - played a major role in the progress of the American Revolution was hotly debated as part of the 1619 project.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1781, Quock Walker ran away from “home”.

Born in 1753 an originally believed to be from Ghana, Walker was a slave, owned by Massachusetts slave owner James Caldwell of Worcester County -- just west of Boston. Caldwell promised Walker his freedom once he turned 25 years old, but Caldwell died before the promise was upheld. Nathaniel Jennison, Walker’s owner after Caldwell’s death, refused to give Walker his freedom. So, at 28, three years after the promise, Walker escaped.

Walker went to a nearby farm owned by Seth and John Caldwell, the brothers of James Caldwell. There he was promised a “safe home”. Somehow, Jennison got wind of Walker’s whereabouts, tracked him down and beat him. Walker fought back, suing Jennison for battery.

At this moment in history, the states, later to be known as the United States, were hoping to gain freedom from England. The American Revolution was in full effect. The language determining citizenship, freedom and what it meant to be “a man” in the eyes of the law were up for interpretation.

Two civil cases were heard, on top of one criminal case: Quock Walker v. Jennison. Though the suit originally circled around battery, it became a suit about the legality of slavery. Walker’s lawyers argued against the concept of slavery -- as the practice went against the Bible and the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. The jury agreed. Walker was a freeman and awarded him 50 pounds in damages. Their decision was appealed and later tossed out, due to a failing to appear on Jennison’s case or papers were improperly filed.

The preamble of the Worcester Anti-Slavery Society (something Jennison would have been enraged to see), 1846 -- Digital Commonwealth

In September of 1781, the Attorney General of Massachusetts brought upon a case on the battery charges and the question of Walker’s freedom to the state’s Supreme Court. The results went unchanged. The Massachusetts Supreme Court found Walker a freeman, citing the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights -- “all men are born free and equal” -- as the basis of its decision. In their review, the court cited Brom and Bett v. Ashley (1781) in their reasoning for the Walker decision. That case concerned an African-American woman named Elizabeth Freeman (known as Bet or MumBet) who sued for her freedom and won -- effectively becoming the first enslaved African American to win a freedom suit in Massachusetts. Both these decisions effectively ended slavery in Massachusetts, though no new laws were put in place. A gradual disappearance of the practice happened over the news one hundred years.

In the 1790 United States census, no slaves were recorded in Massachusetts.

This decision gave Boston -- the state’s largest city and capital -- a glowing destination for runaway slaves and freed people of color. They settled in today’s Beacon Hill community, on the north-side of Boston. Its name comes a former beacon that sat upon the neighborhood’s highest point. By the mid to late 1700s, around more than 1,000 African Americans called Beacon Hill home. Throughout the 1800s and into the 20th century, Beacon Hill became the battling ground for those arguing for emancipation, citizenship, women’s rights and tons of civil rights causes.

Today, Boston’s Black Heritage Trail runs through Beacon Hill, detailing the sites and people of the city’s African-American history. From private homes to schools to meeting sites, the walk takes one on a journey through some of Boston’s (and the country’s) highest and lowest points in its history.

54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial

The memorial that sits opposite of the Massachusetts State Capitol is a good starting point for the tour. Its depiction of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment is a fairly well-known story in American history.

The regiment was an infantry regiment that saw service during the American Civil War. It was the first African-American regiment created by a northern state during the war, where all the men enlisted were African-Americans. The officers, however, were white men: most notably Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the regiment and a patron of Boston. Shaw came from abolitionist parents and believed his men should be treated as soldiers--regardless of their skin color. He told his men to refuse pay until the government was willing to pay them equally.

Their most famous engagement came at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner in July of 1863. The 54th Massachusetts led a frontal assault on Fort Wagner and paid heavily: 20 were killed, 102 went missing and 125 were wounded. The battle was a Confederate victory, but the battle’s legacy is more important. Shaw died as he led his troops toward the fort, and his body was left in a ditch with his fallen African-American soldiers. Confederate victors thought the gesture an insult to Shaw’s honor; Shaw’s family and friends believed different. “We can imagine no holier place than that in which he lies, among his brave and devoted followers, nor wish for him better company,” Frank Shaw, the commander’s father, wrote to the surgeon of the regiment.

In 1900, William Carney, a sergeant in the 54th Massachusetts regiment, received the Medal of Freedom for his bravery during the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. During the battle, when the outlook of victory was grim, Carney grabbed hold of the regiment’s colors and is said to have shouted: “Boys, I only did my duty; the old flag never touched the ground!”

Today, the memorial sits valiantly in Boston Common. Completed in 1884 by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the 54th Massachusetts’ memory forever lives in for those who pass the impressive site. On top of its important legacy, the memorial serves as a good starting point for Boston’s Black Heritage Trail.

George Middleton House

Walking up Joy Street and two blocks north of the 54th Memorial sits the George Middleton House. Among Beacon Hill’s brick facades and streets, this building sticks out. Its gray facade is notable and it looks out-of-place, essentially squeezed from its surroundings.

The home, built in 1797, was the home of Patriot soldier George Middleton. During the American Revolution, Middleton served as a commander of the Bucks of America. They were a Boston-based military unit who were part of the Massachusetts militia. Little is known and no official records exist, but the Massachusetts Historical Society has a flag belonging to the group -- leaving some credence to their existence.

After the war, Middleton joined others in the African-American community to Beacon Hill and became one of its first residents -- building the home at 5 Pinckney Street that stands today. He championed civil rights after the war for African-Americans, organizing the African Benevolent Society in 1796. At the turn of the century, Middleton turned his attention to ending slavery throughout the country. He worked with community leaders and wrote pamphlets to help the cause gain steam. He died in 1815.

The house today is privately owned, but marks a vivid reminder for Boston’s post-colonial history.

Phillips School

Head down Pinckney Street, where Anderson Street meets Pinckney, and you wind up at the Phillips School.

Built in 1824, the school was primarily a white-only school. In 1855, Massachusetts law required schools to integrate; Phillips Schools obliged with the law. The school became one of Boston’s first integrated schools. During its segregated days between 1835 and 1855, Phillips School was considered the best for children in Boston.

The school rests only blocks away from the Abiel Smith School, Boston’s public school for African-American children (we’ll get there in a second). The African-American community of Boston fought for integration throughout the 19th century and, when integration happened in 1855, were quick to act. African-American children began attending Phillips School almost immediately.

Today, the former school is a private residence. But the box-like structure of the former school is hard to miss in Beacon Hill.

John J. Smith House

Blending in with the rest of the houses at the end of Pinckney Street, the John J. Smith House sits upon a noticeable slope. In 1820, John J. Smith was born in Richmond, Virginia. He arrived in Boston around twenty years later and became a vital figure in Boston’s African-American community.

First, Smith was a barber. But cutting hair was not the only purpose of his barbershop; he began using his barbershop to organize and meet with abolitionists throughout the city. His home at 86 Pinckney Street was a stop on the Underground Railroad, as he aided escaped slaves to freedom. He helped establish emancipation and justice for escaped slaves such as Shadrach Minkins and Lewis Heyden. Charles Sumner, the United States Senator of over twenty years during the mid-to-late-1800s, was a friend and client of Smith. According to the National Park Service, when Sumner was not found at his office or at home, he was said to be found at Smith’s.

During the 1850s, John J. Smith fought for equal rights in Boston’s public schools -- connecting him to the previously mentioned Phillips School. In the 1870s, Smith’s daughter Elizabeth became one of the first African-American teachers in Boston. Georgiana, Smith’s wife, was a notable member of the community, as well. She worked for the Freedman’s Bureau. Public service was something ingrained in this family throughout their lives.

Smith’s post-Civil War workload is equally as impressive. He served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, its third African-American member, and was appointed to serve on the Boston Common Council -- the first African-American to do so. On top of all of these achievements, he successfully worked to have the first African-Americans appointed to work for Boston’s police force.

He died in November of 1906, a glowing reminder of the importance of public service.

Charles Street Meeting House

A little detour of a couple blocks is involved to get to Charles Street, where the Charles Street Meeting House resides.

Originally, the site was the Third Baptist Church, built in 1807. Segregation practices were in force during the early run of its existence. African-Americans were allowed only in the gallery and were not permitted to take part in community events organized by the church. Those rules were not in place for long.

In 1836, Timothy Gilbert invited African-Americans to join him in the pew seating during a service. The results were unsuccessful. Gilbert was expelled from the church; the seating arrangements remained. (Gilbert helped find the Tremont Temple -- today known as the country’s first integrated church.) However, over time, the Third Baptist eventually became more lenient in its inclusion of African-Americans.

Despite the Third Baptist Church’s treatment of African-Americans in its early years of existence, members were mostly anti-slavery in mind. Noted African-American speakers such as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass gave speeches at the church. Notable abolitionists Wendell Phillips and Charles Sumner also spoke at the Charles Street Meeting House.

After the Civil War, various churches and organizations used the church’s space. Today, it is home to various businesses as office space.

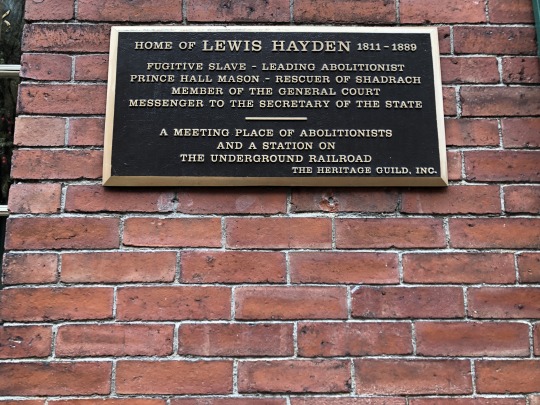

Lewis and Harriet Hayden House

Remember Lewis Hayden? He was one of the escaped slaves that John J. Smith helped in the mid-1800s. Up the street and a couple blocks over from the Charles Street Meeting House -- on Phillips Street -- sits the house of the Haydens.

Lewis was born in 1812 in Kentucky. Hayden was frequently sold in his early years. In the mid-1830s, he married Esther Harvey and had a son. They were all sold to noted United States Senator Henry Clay, who later sold Esther and their son to the Deep South. Hayden never saw them again.

In 1842, after years of learning to read and desperately fighting for his freedom, he married Harriet Bell -- an enslaved woman. Harriet had a son, who Lewis treated like his own. Fearing his family would be split up again, he began planning to escape north. I

Around 1844, Hayden met Calvin Fairbank, a Methodist minister involved with the Underground Railroad. He asked Hayden, “Why do you want your freedom?”. Hayden replied, “Because I am a man.” Fairbank was convinced.

He, along with Delia Webster, a teacher from Vermont working in Kentucky, helped Hayden and his family escape north. Fairbank and Webster were both caught after helping the Haydens escape. Webster served a two-year prison sentence; she was pardoned. Fairbank was sentenced to 15 years. He was pardoned after serving four.

Hayden ended up in Canada, then Detroit, Michigan, ultimately moving to Boston in 1846. He ran a clothing store and became a community leader. In 1850, the family moved into the house that is now part of the Black Heritage Trail. Their home became a welcoming spot for escaped slaves or anyone of color. Between 1850 and 1860, they Hayden house was always full of tenants and residents (according to the Boston Vigilance Committee); they took in anyone that needed help. Among the causes that Hayden thought his time worthy, he helped collect money for John Brown, as Brown prepared for his raid on Harper’s Ferry.

During the Civil War, Lewis Hayden helped recruit for the 54th Massachusetts and later served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. In 1889, Lewis died. Four years later, his wife Harriet followed him to the grave. In death, the two remained a beacon for hope and good fortune to those of need: Harriett bequeathed money to Harvard Medical School, setting up a scholarship for African-American students.

John Coburn House

Continue down Phillips Street and one ends up at the John Coburn House (the darker brick one at the end).

Coburn, born in 1811, was an African-American abolitionist and became one of Boston’s wealthiest residents. He lived most of his life at the house (from 1844 to his death in 1873) that is now a part of this trail -- at 2 Phillips Street. Coburn’s money came from his ownership in a clothing store on Brattle Street in Boston. However, there is some evidence that he also took in money from running a gaming house for “wealthy Bostonians”.

In 1845, Coburn became the treasurer of the New England Freedom Association. Their goal: to aid escaped slaves and fight for their emancipation. Throughout the local papers, Coburn advertised safe lodging for those in need and advertise for his group. In 1854, he founded the Massasoit Guards, an African-American military force to help police Beacon Hill. Coburn was the company’s captain. However, the Massasoit Guards was never officially recognized by Massachusetts.

Along with Lewis Hayden, Coburn helped John Brown’s raid by recruiting volunteers. Coburn died in 1873. He married Emeline Coburn; they had one adopted son, Wendell Coburn, who was deeded all his father’s belongings after his death.

Smith Court Residences

Circle around Cambridge Street and head down Joy Street, again, until you come across a house tucked away by a dead end. This bright structure is part of the Smith Court Residences.

The structure pictured, known as the William C. Nell House, is part of the residences that sit on Smith Court. They are some of the oldest structures in the area’s African-American history. Built between 1798 and 1800, many African-American families called this building-- and those surrounding it--home. The house was a boarding house and many walked through its doors throughout its existence. 3 Smith Court (the one pictured) was home to the area’s longest resident was James Scott, who lived on the premises from 1839 to 1865, and owned the property from 1865 to his death in 1888. He was a clothing dealer and assisted escaped slaves to freedom. (He was arrested once for helping to aid the rescue of Shadrach Minkins, though was later acquitted).

During the 1850s, William Cooper Nell resided on Smith Court. Nell was Boston’s most notable proponents of school integration. He knew and worked everywhere in hopes to see African-Americans living and working side-by-side with their fellow white Americans. He became a noted writer, historian and is remembered as the country first African-American historian.

The buildings surrounding the notable 3 Smith Court structure housed many African-American families. All of which did their part in helping others find safe shelter, food and, in many times, a friend.

African Meeting House

Turn around.

Across the street from the Smith Court Residences is the African Meeting House -- almost the end of the tour.

Built in 1806, the African Meeting House was site of the first African Baptist Church of Boston. It is the oldest “extant church building in the country”, along with being known as the first African American Baptist church created north of the Mason-Dixon line. This was a church built by African-Americans and for African-Americans. The church originally had 24 members, 15 of which were women. Cato Gardner spearheaded its construction, raising $1,500, and his name is still enshrined outside the buildings walls.

The African Meeting House was Boston’s “spiritual center” for its African-American community. It served as the “chief cultural, educational and political nexus” for African-Americans living in Boston. Its speakers throughout the years showcase the church’s importance: William Lloyd Garrison, Maria Stewart, Wendell Phillips Sarah Grimke and Frederick Douglass. Among the many organizations to utilize its space was the New England Anti-Slavery Society, which was founded at the shite in 1832. Furthermore, the 54th Massachusetts used the space as a recruitment post in 1863.

Today, it is a museum and a recommended site to visit when in Boston. The pews are most of the construction is original. One can almost hear Frederick Douglass or any of its noted speakers throughout its history shout and cry for freedom.

Abiel Smith School

Alas, we come to an end.

Next to the African Meeting House is the Abiel Smith School. When Abiel Smith, a white philanthropist, left $4,000 for the African-American children of Boston in his will, community organizers used the money to help fund a school. The building was constructed in 1834 and was the first public school for African-American children -- which was aptly named after Smith. Up until 1835, African-American children went to school next door at the African Meeting House. Now, they had a building of their own.

William Cooper Nell, who later lived across the street from the school, attended and won (along with two other students) the Franklin Medal for academic achievement. They were not allowed to attend ceremonies in downtown Boston. Nell got in anyways, convincing a waiter to let him help serve the white guests. It is said it was during this ceremony that Nell said, “God helping me, I would do my best to hasten the day when the color of the skin would be no barrier to equal school rights.” Perhaps attending this school and experiencing segregation helped Nell fight so furiously for integration later in life.

At the end of the 1840s, many African-American parents took their children out of the Abiel Smith School -- in protest to help integrate Boston schools. It worked, as noted earlier. The Abiel Smith School was closed the same year Boston outlawed “separate schools”.

And, with that, we close the tour of Boston’s Black Heritage Trail. It’s beautiful walk through Boston’s Beacon Hill community and highly recommended for any visitor or resident. For those who have not made the trip, I hope this guide helped explore Boston’s African-American community and history.

(Thanks to the National Park Service and the Museum of African American History for the research, quotes and information.)

#african american history#history#boston#massachusetts#united states#african american#slavery#54th massachusetts#quock walker#frederick douglass#john coburn#lewis hayden#harriet hayden#john j smith#george middleton#writing#my writing#tour#photography

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

t was only 60 years ago that this would have been an unheard of sight in the south. By custom rather than by law, black folks were best off if they weren't caught eating vanilla ice cream in public in the Jim Crow South, except – the narrative always stipulates – on the Fourth of July. I heard it from my father growing up myself, and the memory of that all-but-unspoken rule seems to be unique to the generation born between World War I and World War II. But if Maya Angelou hadn't said it in her classic autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings | IndieBound, I doubt anybody would believe it today. People in Stamps used to say that the whites in our town were so prejudiced that a Negro couldn't buy vanilla ice cream. Except on July Fourth. Other days he had to be satisfied with chocolate. Vanilla ice cream – flavored with a Nahuatl spice indigenous to Mexico, the cultivation of which was improved by an enslaved black man named Edmund Albius on the colonized Réunion island in the Indian Ocean, now predominately grown on the largest island of the African continent, Madagascar, and served wrapped in the conical invention of a Middle Eastern immigrant – was the symbol of the American dream. That its pure, white sweetness was then routinely denied to the grandchildren of the enslaved was a dream deferred indeed. What makes the vanilla ice cream story less folk memory and more truth is that the terror and shame of living in the purgatory between the Civil War and civil rights movement was often communicated in ways that reinforced to children what the rules of that life were, and what was in store for them if they broke them. My father, for instance, first learned the rules when he first visited South Carolina with my grandfather in the 1940s. In our family's home county of Lancaster, Daddy asked the general store owner if he could buy some candy and ice cream, referring to the white man as "Sir". The store owner promptly grabbed my father by the collar, and yelled at him in the presence of my grandfather. Then he informed the elder man, "You'd better teach this little nigger to say 'Yassuh', boy! 'Sir' ain't good enough!" My grandfather grabbed his son and sped off. The late poet Audre Lorde had a similar narrative to Angelou's in her own autobiography, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. She visited Washington DC with her family as a child, around Independence Day, and her parents wanted to treat her to vanilla ice cream at a soda shop. They were rebuffed by the waitress and refused service. She expressed disappointment at her family and sisters for not decrying the act as anything but "anti-American". She summed up the event: The waitress was white, the counter was white, and the ice cream I never ate in Washington DC that summer I left childhood was white, and the white heat and white pavement and white pavement and white stone monuments of my first Washington summer made me sick to my stomach for the rest of the trip. Why were black people allowed vanilla ice cream, but on the Fourth of July? Why then? After all, in 1852 Frederick Douglass railed against the idea of celebrating Americans' independence when blacks did not have their full, God-given freedom. "What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?", asked Douglass of his audience when invited to speak in commemoration of the day. I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. Was that somehow the purpose of allowing the denied ice cream cone? Was it a pacifier? Was it a message to us that, as long as we obeyed the rules, we could still be occasionally rewarded with just enough to keep us patriotic and loyal? But perhaps it is pointless to ask for more than context. The period during which African Americans were not allowed to eat vanilla ice cream tells us a lot about where this memory is located in time: a period of great progress driven by black Americans themselves. It was a time when our forefathers fought for this country and when our foremothers organized marches to protest lynching; when the mass migration from south to north took place; and when labor organizations became vehicles for early pressure for civil rights. The nadir of black life in America – the period from the born at end of Reconstruction through the full entrenchment of Jim Crow – was firmly on its way out. That period of time also represented a closing of the gates of immigration from Europe, the slow rise of the United States as a world power, and the increasing unification of the idea and principles of "whiteness". In 1910, for instance, "white" did not mean Italian, Jewish, Greek, Polish or any of a variety of other ethnicities we now unequivocally associate with privilege. It was, instead, still a term largely reserved for the "old Americans" – those of northwestern European stock. But that changed – at least for some of the Europeans who wound up on America's shores. In the south in particular, new ethnic whites quickly did all they could to assimilate and then affirm their whiteness – to not do so was death, as demonstrated by the lynchings of Sicilians in Louisiana and the lynching of Leo Frank, who was Jewish, in Georgia in the pre-war decades. Little things took on outsized meanings, and each was another way to differentiate between those who "belonged", and those who were barely tolerated. Perhaps the memory of being denied vanilla ice cream is not a literal memory for most: maybe it is just commentary. There is fantastic power in this fascinating memory of Jim Crow life because it calls our attention to the deeper psychological consequences of legalized racism in American life. The racism of the time period was not just about dignity and self-esteem – it was embodied and mythologized in physical terms. So in a way, the denial of vanilla (and all its symbolic promise) was not so bad after all: indeed satisfaction, with "chocolate" is now emblematic of people of color being supported by and being self sufficient in their own communities. Without this exact satisfaction in our sense of beauty, worth, mind and purpose – without having learned to live without vanilla – we never would have fought to change the world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Revolutionary War: Which Side Gave the Best Shot at Freedom?

Photo: Boston Massacre, Federal Works Agency. Work Projects Administration. Division of Information.

For Africans in the colonies, the American Revolution represented a paradox and an opportunity. Both Patriots and Loyalists recruited enslaved men, yet both continued to condone slavery. Some slave owners even sent enslaved men to fight in their place. But the war also gave Black soldiers a chance to escape to and earn freedom.

African American Loyalists

Photo: Black Loyalist soldier in British uniform, Detail, The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781, John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). Copyright Tate, London 2015.

The British capitalized on the hopes of enslaved blacks as the armed them for battle with the promise of freedom. Blacks strategically chose to become loyalists to fight for freedom from slavery. It is estimated that at least 20,000 enslaved people, over half from the South, fled to join the British from 1775 to 1782. At the end of the war, some secured their freedom and others were sold back into slavery, but all challenged the limits of liberty.

African American Patriots

Photo: Revolutionary Era Black Sailor, Los Angeles Art Museum, www.lacma.org

In 1775, George Washington penned a letter to Col. Henry Lee remarking that the success of the war depended upon which side quickly armed Africans. The Patriot leaders were initially reluctant to enlist Africans in the armed forces for fear of a rebellion and the loss of their enslaved property. But the British offered enslaved people freedom after service, and by 1776, George Washington also extended the promise of freedom to Africans who enlisted in his army. Enticed by Washington’s promise of liberty, 5,000 enslaved African Americans participated as Patriot combatants.

The Aftermath

Photo: A Black wood cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia, by Captain William Booth, 1788, Coverdale Collection of Canadiana, Library of Archives Canada, C-04162.

After the Revolutionary War, a new nation secured its liberty. The irony of the sacrifice and participation of the 5,000 African Americans that served as combatants with the colonial forces rung loud throughout early America. The valor of enslaved African Americans fighting for the independence of their enslavers inspired Vermont, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts to end slavery in their states before the end of the War. New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Connecticut ended the practice soon after.

Yet the freedom of African American soldiers who fought remained uncertain. Some of the Black Patriot soldiers that participated in the war secured their freedom, while many others remained enslaved. Similarly, of the 100,000 Americans who left America with the British after the war, 15,000 were African Americans. They moved to Britain, British colonies in the West Indies, Canadian colonies like Cato Ramsay and Nova Scotia, and colonies in Sierra Leone. Overseas, some Black Loyalists gained their freedom, while others were re-enslaved by their Loyalist slaveholders or sent to be enslaved elsewhere in the British Empire.

Through bravery, some African American soldiers found freedom, and all helped expand what freedom might mean and whom it might include.

36 notes

·

View notes

Link

They include a spy, a poet, a guerrilla fighter—and foot soldiers who fought on both sides of the war.

During the American Revolution, thousands of black Americans jumped into the war, on both sides of the conflict. But unlike their white counterparts, they weren’t just fighting for independence—or to maintain British control. In a time when the vast majority of African Americans lived in bondage—their forced labor fueling the economy of the fledgling nation—most took up arms hoping to be freed from the literal shackles of chattel slavery. In fact, when enslaved people had choice in the matter, according to historian Edward Ayres of the American Revolution Museum in Yorktown, Virginia, they signed on with whichever side seemed most likely to grant them personal freedom.

For some slaves-turned-soldiers, the Revolution’s promise of liberty became a reality. But despite the patriots’ lofty rhetoric about liberty and justice for all, America’s war for independence didn’t herald widespread emancipation for enslaved people of color. America’s northern states didn’t pass laws to abolish slavery until 1804—and even then, some areas phased it out slowly. Southern states would cling to the brutal practice for more than a half-century longer.

Historians estimate that between 5,000 and 8,000 African-descended people participated in the Revolution on the Patriot side, and that upward of 20,000 served the crown. Many fought with extraordinary bravery and skill, their exploits lost to our collective memory. Below are the stories of several exceptional African American figures—a martyr, a poet and a double agent among them—whose crucial contributions to the conflict have been remembered to history.

READ MORE: He Fought for His Freedom in the Revolution. Then His Sons Were Sold into Slavery

Crispus Attucks, Martyr

Crispus Attucks, whom many historians credit as the first man to die for the rebellion, became a symbol of black American patriotism and sacrifice. In 1770, as tension mounted between British and colonial sailors in Massachusetts ports, distrust and competition among them grew. These pressures came to a head on March 5th, when an angry confrontation turned into a slaughter known as the Boston Massacre.

Witnesses say that Attucks, a middle-aged runaway slave of African and native American descent, who worked as a sailor and a rope maker, played an active role in the initial scuffle. Of the five colonists killed, he was said to be the first to fall—making him the first martyr to the American cause. He was taken down by two musket balls to the chest.

READ MORE: 8 Things We Know About Crispus Attucks

Salem Poor, Patriot Soldier

Postage stamp depicting Salem Poor, a soldier at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Salem Poor began life as a Massachusetts slave and ended it as an American hero. Born into bondage in the late 1740s, he purchased his own freedom two decades later for 27 pounds, the equivalent of a few thousand dollars today. Soon after, Poor joined the fight for independence.

Enlisting multiple times, he is believed to have fought in the battles of Saratoga and Monmouth. He’s most famous, however, for his heroism at the Battle of Bunker Hill—where his contributions so impressed fellow soldiers, that after the war ended, 14 of them formally recognized his excellent battle skills with a petition to the General Court of Massachusetts. In it, they called him out as a “brave and gallant soldier,” saying he “behaved like an experienced officer.” Poor is credited in that battle with killing British Lieutenant Colonel James Abercrombie, along with several other enemy soldiers.

Colonel Tye, Loyalist Guerrilla

The Death of Major Peirsons, painted by John Singleton Copley. Colonel Tye is pictured left from the center.

Colonel Tye earned a reputation as the most formidable guerilla leader in the Revolutionary War. During his years fighting for the British, Patriots feared his raids, while their slaves welcomed his help in their liberation.

Tye, originally known as Titus during his early years in slavery in New Jersey, escaped a particularly brutal master in 1775 and joined the British army after the Crown offered freedom to any enslaved person who enlisted. While Tye stood out as a soldier from the start, the British didn’t station him at pitched battles. They saw more value in using his knowledge of the coveted New Jersey territory, which sat between British-occupied New York and the Patriot’s center of government in Philadelphia. The Redcoats needed to take this middle land—and believed Tye could help.

The British were right. Tye excelled at raid warfare there. His familiarity with the area gave him an advantage in attacks on Patriots’ lands. And his daring, skillful execution kept his Black Brigade soldiers largely unscathed as they plundered homes, took supplies, freed slaves and sometimes even assassinated Patriot slaveholders renowned for their cruelty. The British recognized Tye’s impact on their success and, out of respect for all his contributions, bestowed on him the honorific title of Colonel. He remains an important symbol of fearless resistance.

READ MORE: The Ex-Slaves Who Fought with the British

The First Rhode Island Regiment, Integrated Revolutionary Force

A painting by French artist and sub-lieutenant Jean Baptiste Antoine de Verger, depicting the different men of war, including a member of the First Rhode Island Regiment on the far left.

The First Rhode Island Regiment, the first Continental Army unit largely comprised of New England blacks, showcased African Americans’ skill as soldiers and commitment to their brethren on the battlefield. In the late 1770s, dwindling manpower forced George Washington to reconsider his original decision to ban blacks from the Continental Army. So in 1778, a Rhode Island legislature declared that both free and enslaved blacks could serve. To attract the latter, the Patriots promised freedom at the end of service.

Though relatively small—only about 130 men—the First Rhode Island Regiment had an outsized impact. Commanding General John Sullivan praised its soldiers for their success against attacks in the Battle of Newport, saying they displayed "desperate valor in repelling three furious Hessian (German) infantry assaults." When the Rhode Islanders journeyed to Virginia, where several thousand other soldiers were assembling, they stood out, according to aFrench military officer there, as “most neatly dressed, the best under arms and the most precise in all their maneuvers."

And one early historian, William Cooper, lauded their fierce loyalty. When their commander Colonel Christopher Greene was cut down during a surprise early-morning attack in May 1781, he wrote, “the sabers of the enemy only reached him through the bodies of his faithful guard of blacks, who hovered over him to protect him, and every one of whom was killed.”

Phyllis Wheatley, Patriot Poet

Phyllis Wheatley.

Phillis Wheatley was a revolutionary intellectual who waged a war for freedom with her words. Captured as a child in West Africa, then taken to North America and enslaved, Wheatley had an unusual experience in bondage: Her owners educated her and supported her literary pursuits. In 1773, at around age 20, Wheatley became the first African American and third woman to publish a book of poetry in the young nation. Shortly after, her owners freed her.

Influential colonists read Wheatley’s poems and lauded her talent. Her work, which reflected her close knowledge of the ancient classics as well as Biblical theology, carried strong messages against slavery and became a rallying cry for Abolitionists: “Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain, /May be refin’d and join th’ angelic train.” She also advocated for independence, artfully expressing support for George Washington’s Revolutionary War in her poem, “To His Excellency, General Washington.” Washington, who himself had been forced to end his formal education at age 11, appreciated Wheatley’s support and extolled her talent. The commander even invited her to meet, explaining he would “be happy to see a person so favored by the Muses.”

Peter Salem, Colonial Hero

Peter Salem shooting British Royal Marine officer Major Pitcairn at Bunker Hill.

Peter Salem is best known for his crucial contributions at the outset of the Revolution. Born into slavery in Massachusetts in the mid-18th century, Salem joined the Patriots in the earliest battles of the war, participating as a “minute man” at Lexington and Concord. His owners supported this decision and freed him so that he could remain enlisted.

Salem earned his place in history for his role in one the most important Revolutionary War fights, the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill. Although the British defeated the Continental Army in this encounter, it wasn’t a total loss for the Patriots: Their killing of many Redcoats encouraged them to keep up the fight. Many historians credit Salem with killing a key officer of the crown, Major John Pitcairn, just as he was scaling the top of the American redoubt and demanding that the Patriots surrender. Salem’s role is believed to have been memorialized in John Trumbull’s painting The battle of Bunker's Hill.

James Armistead Lafayette, the Double Agent

Marquis de Lafayette and his assistant James Armistead.

During the Revolution, James Armistead’s life changed drastically—from an enslaved person in Virginia to a double agent passing intel, and misinformation, between the two warring sides. When Armistead joined the Patriots’ efforts, they assigned him to infiltrate the enemy. So he pretended to be a runaway slave wanting to serve the crown, and was welcomed by the British with open arms. At first they assigned him menial support tasks, but he soon became a more strategic resource due to his vast knowledge of the local terrain. Armistead’s role got more interesting when the British directed him to spy on the Patriots. Since his loyalty remained with the colonists, he claimed to be bringing the British intel about the Continental Army, but he was actually pushing incorrect information to foil their plans. In the meantime, he was learning details of the British battle plans, which he brought back to his commander, General Marquis de Lafayette.

This served the Americans well. Because of Armistead’s efforts, they got the insight they needed to successfully execute the decisive Siege of Yorktown, which effectively ended the war. Years later, after a testimonial from the French general helped secure Armistead’s freedom, the former slave changed his surname to Lafayette.

READ MORE: How a Slave-Turned-Spy Helped Secure Victory at the Battle of Yorktown

from Stories - HISTORY https://ift.tt/2OHZyqk February 12, 2020 at 02:01AM

0 notes

Text

There is no escape from politics

How NFL owners and Donald Trump put down a national protest.

I. “By the way, everyone wanted to be here today”

It is the day Donald Trump is meeting with the Stanley Cup champion Pittsburgh Penguins, and I am sitting in the basement of the White House with a group of black folks. The group is made up of journalists, cameramen — all here to watch the day unfold.

The mood is light; we talk; joke. But it’s hard not to recognize how surreal this scene is. Here we are on this October afternoon, black, in a house built by slaves — a house where the first black president used to dance with his black wife, laugh with his black kids, and enjoy the company of his black friends.

That was then. Now, upstairs lives a president who is there largely because he is not black, whose campaign was built upon thinly veiled promises to return power to the majority; to make things the way they were before a black man was president.

We eventually walk inside the East Room, listening to the president speak, his words twisting in the pretzel logic we’ve somehow gotten used to. I can’t help but think how weird this all is. Gone are the days of Obama dancing with Northsiders and Cubs on one of the last days of his administration. The White House felt warm, inviting, even loving under Obama for folks like me. This place feels cold, aggressive, and devoid of anything harboring black joy.

“By the way, everyone wanted to be here today,” Trump says, smiling. “And I know why.”

His smile is one I recognize. It’s one that doesn’t quite involve his eyes.

There is constant cheering. Trump calls the hockey players handsome. He says they are incredible patriots, embodying values all young Americans needed to see. It’s unclear if Trump realizes how many of these young men weren’t born in the U.S.

It’s also clear that these hockey stars aren’t being celebrated for what they have accomplished. Trump’s White House has not rushed to invite any other teams who have won championships, including the Golden State Warriors. It took Stephen Curry saying he wasn’t interested in going to the White House for Trump to say the invitation was rescinded — in truth, no invitation had ever been sent to the team. The only other team Trump has welcomed has been the Chicago Cubs, whose co-owner, Todd Ricketts, was a Trump supporter and had been considered for Deputy Secretary of Commerce.

The Penguins are welcomed with open arms as a display of how white athletes are meant to behave. The president can’t put aside his own agenda, even for a moment. Trump brought the team here to reinforce his attacks against the black people he deems dishonorable, the football players who have protested police brutality, and who Trump has made his latest adversaries in his never-ending culture war.

The white audience seems unaware or uncaring. The blackness in the room or watching on TV is being taunted. Trump is taking a victory lap with his chosen champions, gaslighting nonbelievers and smiling while they squirm.

These political gymnastics are exhausting. For the entirety of this charade, I have felt disoriented. How can no one address this?

In this moment, I remember where I’d seen that smile.

II. The Day of Reckoning

It was a few weeks before that day at the White House, Sept. 25, when Dallas and Washington faced off in a Monday Night Football game.

All weekend, NFL players had kneeled during the “Star Spangled Banner,” some in support of Colin Kaepernick and his original protest against the police killing of black people. Others were responding to Trump, who implored NFL owners to "get that son of a bitch off the field right now" if a player kneeled during the national anthem at a rally earlier that week.

While some NFL owners supported their players and were vocally against Trump’s vulgar tirade, reports had come out that the majority of NFL owners were scrambling to find a way to stop the protests, or at least quiet them down enough to make football the story again.

Ahead of Monday Night Football, there was little talk of what would happen in the game. It was all about what would happen before the kickoff, during the playing of the “Star Spangled Banner.” Sports fans, culture warriors, and America tuned in as Cowboys owner Jerry Jones walked out with his players. I’ll admit: I did not, in my wildest thoughts, think I’d see ol’Jerruh, practically a caricature of a rich white man, walk out with these men.

Then, before the “Star Spangled Banner” began, they all kneeled, arms locked, Jones right in the middle. Jones kept his head down while fans booed. He did not care. His plan was already in motion. He finally looked up. The cameras moved closer. He looked directly into the lens and there it was: the smile. That same, soulless smile.

Then, just before the song, Jones and the rest of the Cowboys stood. It was a protest without any teeth. His smile had been a clear signal to white America: Don’t worry. Jerry will take care of this. We’re going to put them in their place.

What was funny about all this was that Jones, certainly by accident, actually showed hypocrisy on the part of the white people he was trying to send a signal to. He exposed the lie that kneeling was about the “Star Spangled Banner” or patriotism or Trump. He knelt before the song played and was still booed.

If Jones’ demonstration was inartful, it was at least emphatic. Jones has made no mistake about his belief that players should stand for the national anthem, even threatening to lead a coup against commissioner Roger Goodell in part because Goodell wouldn’t place any mandate on players. Even within a group of 31 owners who had collectively donated millions to Trump’s campaign, Jones was a hardliner, and he was lock-step with Trump that Goodell should have nipped the protests in the bud. Via ESPN:

At first, some in the room admired Jones’ pure bravado, the mix of folksy politician and visionary salesman he has perfected. But he was angry. He said the owners had to take the business impact seriously, as the league was threatened by a polarizing issue it couldn’t contain or control. To some in the room, it was clear Jones was trying to build momentum for an anthem mandate resolution, and in the words of one owner, “he brought up a lot of fair points.”

Jones couldn’t get exactly what he wanted — what Trump had demanded — in part because the movement was too big. Watching black bodies defy power in primetime was unexpected. Players reacting so quickly and strongly was unexpected and beautiful, and the league was too overwhelmed to react. The weekend had a chance to be historic. Jones needed to usurp the cause somehow, and he found a way. That moment when Jones smiled, I felt that beauty slip away.

That smile haunts me. It was in that moment I understood that this movement would be taken over and killed. This was the white owner reasserting control.

Truthfully, football was never meant to serve the black body.

This was the co-opting of a black message. This was a smile equivalent to a death sentence, signaling the fate of Colin Kaepernick’s movement — the end of an international moment staked in black pride.

This is something we have seen time and time again in the history of American sport: the use of the black body for popular entertainment; black men and women using that popularity to speak out, then white gatekeepers (either owner, audience, or overseer) co-opting that message or striking it down, often violently.

Truthfully, football was never meant to serve the black body, which has been abused for generations. America watched as men they perceive as property begged for a voice and were muzzled. This is a cycle America has always known. It is no wonder these NFL players did not get far.

III. “Those wild and low sports”

Maybe it was destiny that led Tom Molineaux to Copthorne Common on a blustery December afternoon in 1810 to fight Tom Cribb.

Molineaux, a man newspapers called the “American Othello,” was a freed slave from a Virginia plantation whose family taught him to box. Cribb was the champion of England and white. Molineaux had sailed from America just six months prior to start a new life as a prize fighter.

Englishmen thought he was a lamb being led to slaughter. Though the English were sympathetic to abolitionism, a slave wasn't supposed to swing against his white master. By the ninth round, Cribb was being pummeled. After 30 minutes, fans rioted. They thought Molineaux was cheating. By some accounts, they even broke his fingers.

After 39 rounds, Molineaux conceded, finally succumbing to exhaustion. He appeared to knock out Cribb in the 28th round, but no one could hear the referee call "time!" to indicate that Molineaux had won in the chaos that ensued. Cribb recovered and the fight continued. It was a brilliant fight by all accounts, yet there wasn’t much to read about Molineaux’s exploits in America outside of a small clipping in a North Carolina newspaper.

Molineaux was a symbol of a possibility that was deadly to the white world back then. If black people could prove they are equal in one arena, who's to say they shouldn't be equal in every arena?

Sports were the thing that kept Molineaux enslaved and his tool for liberation. Sports were created on the plantation as diversions to help slavers control the revolutionary urges of slaves. Frederick Douglass, who fought off his owner and ran to freedom, was a critic of sports on the plantation. In Douglass’ autobiography, he said Southern plantation owners deployed “those wild and low sports” in an effort to keep black slaves “civilized.”

What Douglass wrote is, foolishly, why owners expect athletes to know their place. It is why no one expected a Day of Reckoning to begin with. What Douglass missed, and what black athletes discovered, was the expressionism sports allowed. As Molineaux demonstrated, sports create room for protest because they hold the minds of the white consumers hostage during play.

White people showed up to watch Cribb beat Molineaux, and instead were held captive as Molineaux upended their expectations. Similarly, they did not think, both owners and fans, that black football players were capable of revolt. And just as Molineaux helped establish a norm, NFL players have made protest commonplace. To restore the old order would require intervention, co-option — violence of a non-physical sort. That was the reason behind ol’Jerruh’s smile. If order was to be reinstated, pain of some kind would have to be established.

IV. “Coach, a Negro boy can’t play football with white fellers”

It took seven minutes for Oklahoma A&M — the university now named Oklahoma State — to try to kill Johnny Bright, Drake University's black Heisman candidate. It was 1951. Bright was knocked unconscious three times, often without the ball. The third was the most brutal. A large, white defensive end named Wilbanks Smith saw Bright, looking left, throwing a pass. Seconds later — some say as many as six — Banks leapt from his feet and cracked Bright’s jaw with a forceful elbow. Bright’s trainer and another player carried him to the bench. A penalty hadn’t been called all day.

Maury White, who wrote about the attack for the Des Moines Register, said, “You could feel the bones move.” Photos of Bright are kept in the Drake Heritage Collection. They show images of Bright pulling his mouth apart, wires keeping his jaw straight, the reason his college career was upended. The “Great Negro Flash” would never make it to the NFL.

Local accounts before the game had students saying Bright ��would not be around at the end of the game.” Three students told the Register that A&M’s head coach was seen yelling ”get that nigger” when the scout team was running Bright’s plays. Bright told the paper in 1980: “There’s no way it couldn’t have been racially motivated.”

Smith, the white man who tried to kill Bright, said in 2012 he had “nothing to apologize for.” Within two days after the incident, Smith received hundreds of letters of support. Half of the messages begged him to run for office in Louisiana or lead local Klan startups.

“If it wasn’t Wilbanks Smith, it would have been someone else,” the A&M basketball player Dean Nims told the Register in 1980. “They were determined to stop Bright.”

Oklahoma State waited 22 years after Bright died to express sympathy.

Violence was the price of being black in these spaces. It is important to understanding the Day of Reckoning. Players are not simply millionaires asking for attention. They have received death threats, their parents have lost their jobs, their jerseys have been burned from New York to Oakland, their likelihoods are being used as tackling dummies before games, and their coaches are called “no-good niggers.”

A few years before Bright had his jaw demolished in front of the country, Levi Jackson, the first black football captain at Yale, was playing in a high school exhibition. His body had been thrashed for hours, and he was ready to quit. In this era, it was common for white players to attack black players between the whistles. Jackson, however, was fed up. Reading his words, I assume he knew what this sport could do to us. The message was there: White sympathy was not for us unless we were willing to get over race.

“Coach, a Negro boy can’t play football with white fellers,” he said, according to Sport Magazine in Nov. 1949. “You saw what they did to me today. I’m turning in my suit. It’s not sport.”

V. “Nothing more than a mere picnic”

After the Day of Reckoning, the NFL responded by promoting a message of "Unity." I have grown so tired of hearing about “unity” that I no longer believe it's real. What is unity? What are we unifying against? It doesn’t appear to be racism. It has never appeared to be racism. When the concept of unity was offered to these black athletes, it felt comedic.

Look at all these white men. They do not look afraid, as I have. They do not seem tired, as I am.

And the black athletes who felt the same way were often labeled as ungrateful millionaires. "Ungrateful is the new uppity," Jelani Cobb wrote in the wake of the president's attack on players.

For the current revolting black athlete, this certainly seems the case. By co-opting the message of the protests, NFL owners like Jones were able to make still-unsatisfied athletes seem bitter and greedy in a certain light. Thus, Jones' performative wokeness successfully play-actioned protests about police brutality into something lesser that many players felt obligated to accept or else be ostracized even more.

This sort of transformation of messaging angered Bill Russell, one of America’s great social agitators in sports. By the time the March on Washington came to the capital in 1963, Russell was disenchanted with the Civil Rights Movement. He was sick of compromises. He said the day became “nothing more than a mere picnic” because whites marched. The message changed, and the voice of the oppressed was not one with the oppressor at his shoulder.

“The March on Washington was brilliantly conceived and badly executed,” Russell recalled in Go Up For Glory in 1965. “The bigots will make something of this. But I concur with what Malcolm X said: ‘They merely marched from the feet of one dead president to the feet of another.’”

Acts of "Unity" have been the fodder making America’s heart swell. Hand-holding in the face of a president who believes people of color are inhuman plays into America’s often misguided ideals of egalitarianism. Our nation loves to see black hands holding white hands but has never stopped to gauge what it accomplishes. We are not post-racial by any means, and we will not get there soon by evading America’s insidious nature.

Co-option is a powerful tool. So is money. This year, Eagles safety Malcolm Jenkins said he would stop protesting after NFL owners met with the Players Coalition — a group Jenkins co-founded — and agreed to give $89 million over seven years to charitable groups working toward criminal justice reform and better relationships between community and law enforcement. Several members of the Players Coalition, including 49ers safety Eric Reid, publicly announced their decision to leave the group when the announcement was made.

NFL owners didn't have to look far for a lesson in how to stifle a movement.

In 1961, the Baltimore Colts played the Pittsburgh Steelers in an exhibition game in Roanoke, Va. Virginia State Police were enforcing Jim Crow seating. Local NAACP chapters filed lawsuits. For days state courts didn’t hear the suit. Telegrams were sent to black players on both teams. Coaches asked them what they would do if the game proceeded, and many said they wouldn’t play if segregated seating was enforced. Roanoke officials gathered and said they would ignore the segregationist law to keep peace with players. Pete Rozelle, the NFL commissioner, even sent out a press release.

Newspapers labeled the day a victory before it began. Then Lenny Moore, a star tailback for the Colts, walked inside the stadium and saw that the gatekeepers had lied. Jim Crow seating was enforced, just like any other day.

“I had to reach through the chain-link fence in order to shake their hands,” Moore said in his autobiography. “No image had ever made me realize, with such force, just what blacks have been up against all through American history: We have always been on the outside looking in.”

The lesson here is to be wary of white folks; to know that football is fun, but it is also work. You must maim your body for the happiness of your owner, fans, and America. Or you will be fired. You will be cast aside. And you will go back to being an unknown number in a country that does not love you.

VI. “What they are saying is don’t upset the system.”

As we leave the East Room back on that October afternoon, I think to myself that this did not happen by chance. The concerns of black constituents, black footballers calling for an end to police brutality, none of these is as mighty as the man attacking them to get praise from white Americans.

Only under Trump could the Day of Reckoning have happened. If Obama’s presidency was a result of a second era of Black Reconstruction, then Trump, as the journalist Adam Serwer and the author Ta-Nehisi Coates have noted, sparked a second wave of white redemption.

Trump’s white identity politics are stronger than concerns about his temperament, his sanity, or the people who inhabit his administration. They are stronger than the black athletes at odds with him. If white Americans of virtually every economic background were willing to elect a man like this, one whose political identity is tailored for white nationalism, then there is no place for black, protesting football players.

Trump will always attack black athletes because they pose a threat to this white power dynamic, and because it is the easiest way to signal to his base that that they are right to feel threatened. They are evidence that the gatekeeper’s control is slipping. To suppress that idea, Trump must dismiss them and dehumanize them. As an added bonus for Trump, this excites the base — the large swath of the country that created this moment.

“If you look very carefully you will see that they are the same people who are quite happy with the situation as it is,” the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe told James Baldwin in 1980. “What they are saying is not don’t introduce politics. What they are saying is don’t upset the system. They are just as political as any of us. It’s only that they are on the other side.”

I can understand why the gatekeepers claim these footballers unpatriotic, because they don’t see us as citizens of their states. This can be an argument about the flag if you don’t believe it represents folks like me.

Near the manicured lawn of the White House, Mike Sullivan, the Penguins coach, begins speaking to gathered press. Sullivan reinforces the lie of the afternoon: He says he felt no pressure accepting an invitation here because it wasn’t political. This was only a celebration, he said.

Jerry Jones provided the smile that killed football’s latest revolt. He is no ally. He is not smiling to me. He is smiling to them: the rest of America.

At this point in our history, it seems foolish that someone could offer this misconceived belief unless they are too nonchalant to care or very careful to preserve their position of power. Either feels like cowardice.

“Does it matter that, regardless of [what you’ve said], the president is using you and your team as a prop in this culture war against other black leagues?” I ask. “Because you can kind of say it as many times as you want, but the appearance is that you are complicit.”

“See, you're suggesting that that’s the case,” Sullivan says. “We don’t believe that.”

It was that moment when I knew, despite anything said, that my initial thought was correct. This shit was weird. Trump and whiteness had won the Day of Reckoning. To be passive in the face of the crime is as dangerous as the transparent attack. To be willfully ignorant about race perpetuates and enables racism in America. I can’t help but think that they are all too afraid, too scared to challenge white power, to do what is just, to show a shred of morality for the unprivileged.

And while it is weird, by this point Sullivan’s words are expected. Yes, all of this is still insulting. Yet since black people were kidnapped and dragged here, four violent centuries says all of this is the American normal.

Jerry Jones provided the smile that killed football’s latest revolt. He is no ally. He is not smiling to me. He is smiling to them: the rest of America. I’m sure they are at ease. His message to them is one that we have heard from white people in power for centuries: Don’t worry. The black men had their fun and are back, reset, ready for servitude, docile once more. How dastardly. How American. What a rush.

VII. “We gon’ be alright”

Talking to black people in this country about the last two years since Kaepernick ignited protest in football and elsewhere, it is easy to become despondent. Folks truly, honestly, wanted to believe something could be done, that we could be saved, and that progress, the same progress we have always clamored for, was possible.

Look around. There is no better. There is no hope. This movie ends in tragedy. The idea that white folks think black folks have reason to believe in change is deflating.

There is no reason for optimism when the first black president was followed by a man looking to destroy his legacy and belittle the achievements and advancements of people who he sees as less than. That includes the men in pads who look as I do.

How can I enjoy optimism while a country pays black people for entertainment, appropriates our culture, then spits in their faces when they say anything other than “thank you?”

Optimism is not for me, though, it is beautiful to dream. There is no hope for the black body in modern America. But neither am I despondent.

Black protesters turned football players should not be hopeful. They also should not compromise. They did not win. Whiteness won. It always wins. But there is space to be positive. Blackness has become indefatigable even if our existence here and on the football field fighting for equality is Sisyphean and disheartening.

Thinking of this often makes me think of Kendrick Lamar and his anthems about Black America. On his 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly, Kendrick examines the emotions we can have being American. In the past 15 months, I found myself doing this, going back to these affirmations, humming them during the “Star Spangled Banner.”

“Nigga, we gon’ be alright,” Kendrick promises.

These words, in repetition, are like a proverb. Black people were kidnapped and tortured on the way to this country, built its infrastructure, and became its greatest athletes and entertainers. We are the culture, the sound, its consciousness — the heartbeat of America and somehow also its biggest enemy. Kendrick’s ghetto lullaby reminds me of that. The toot of that saxophone, the ping of that high hat, the rasp of his Compton attitude: It’s all soothing.

Our culture, our beauty, allows us — throughout this tortured cycle of protest and destruction — to keep our pride. There is fire shut up in our bones. We have shown how mighty we are. Listen to the song. Kendrick keeps saying, “Nigga we gon’ be alright.”

Well.

Nigga, maybe you right. Maybe one day we actually will.

0 notes