#so the utopia becomes the dream of these tech leaders

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Master Willem was right, evolution without courage will be the end of our race.

#bloodborne quote but its so appropriate#like big healing church vibes for them tech leaders#who are all shiny eyed diving headfirst into the utopic future#nevermind the fact that the dangers are only rlly obscured by their realism#the dichotomy of this ai will change the world make the world perfect that what we want#and they wanna get it there#but theyre not there#the chatbot is the thing they have to show for#granted when u use plugins and let a bunch of llms do shit together#u see the actual inscrutable magic that they can make happen#and that magic is also so threatening#but were all blinded to it bc we can only rlly acknowledge the watered down simplified realistic view of the reality#which is synival silly and ridiculous bc reality itself is one but so subjective bc we only have each persons interpretation#and its all so socially constructed#so the utopia becomes the dream of these tech leaders#and they wanna make it real#and its almost there#but the nighmare?#the dystopic future#they dont acknowledge#bc they dont dream or try to make it happen#and then theres just the basic reality#but its all tigether#just bc utopia is unlikely but possible#doesnt mean that having the tech for it#will lead to that#bc the system is the same#weve kept inovating non-stop and yeah so much commodification and wuality if life#but not acc changing anytjing

92K notes

·

View notes

Link

Here is the problem: technology is producing profound insights in the realm of politics, but the realm of politics is succumbing to deep ignorance about technology. Theorists of technology are becoming the most significant sources of political ideas; theorists of politics are becoming incapable of understanding significant technological ideas.

Unschooled in perceiving the development of digital technology for what it is, political leaders now frenetically throw around appeals to concepts—slogans, “values,” “ideals”���that have come unglued from the reality formed by our surrounding digital environment. The concepts being developed by leading technologists, by contrast, are gaining serious influence over political life despite their departure from “mainstream” concepts because of how strongly rooted they are in perceptions formed by the digital environment.

These two destabilizing trends raise (significantly) two linked issues, one more abstract and one more particular. First, is the Western political tradition obsolete? Second, is America, because of its regime, worth the trouble of trying to preserve?

…

The key is that the content of those broadcasts mattered less to the structure of social order than the context that was televisual (and other electric) media itself. The context was the rule of the human imagination. Those most expert at creating ethical dreams for mass broadcast and adoption made up the institutional elite, both in private and public life: the spheres of influence which smeared together and produced a global Western ruling class.

This class, psychologically and socially deeply formed by the electric environment, was emotionally and scientifically certain that the technological progress they superintended would result in the consummation or perfection of their globalized environment. This context decisively shaped the content of what we might call “televisual ethics.” In this way was the medium itself the “message.”

…

Now we all could be our own TV hosts, channels, even our own broadcast networks. The internet would enable the televisual medium to perfect the “togetherization” of everyone—productively, peacefully, and amicably. Everyone would become “friends,” in the new idiom, although really the idea was much closer to the more loaded phrase invoked by electric age idol John Lennon in the televisual anthem “Imagine”—“a brotherhood of Man.”

These democratizing and capitalizing features of perfect televisual rule would consecrate a durable new relationship between rulers and ruled. The ambitions of H.G. Wells, who had prophetically dreamed up a postwar utopia where religion, family, and the nation-state had been replaced by a virtuous post-political elite of imagineering scientists of ethics, would at last be achieved.

Of course, this is not what happened. And in all likelihood it is the opposite of what is yet going to happen. But why? The view of the imagineers and their faithful audiences is that the machines they built to produce utopia were abused by all-too-ordinary people, who are still plagued by the disgusting and dispiriting flaws that have always hamstrung human beings.

…

We united the dreams and the tools that would end history—and these monsters used them to restart it again! This vengeful and wounded cry now shows up constantly in the backlash within tech itself to social media. Making the world safe for democracy at the end of the First World War had failed; making the world safe for elitism at the end of the Second World War also failed; and remaking the world through a fusion of the two at the end of the Cold War has now failed as well. No wonder the increasingly naked desire today is to make the world safe for bot-ocracy. The task of harmoniously ordering humanity has at last been shown to outstrip even the capabilities of the most ethical humans with the best tools; only the bots and the algorithms, perfectly expert in allocation at scale, can save us now.

But such a vision of using robots to realize human dreams is itself an electric-age idea pushed to terminal extremes. Digital shapes us in such a way as to disenchant even this ultimate wager of the imagination. After all, digital technology does not shape our perceptions and sensibilities in accordance with the rule and measure of the human imagination, but in accordance with the supremacy of machine memory. Rather than the psychedelic sensory trip of televisual life wherein each individual is ethically moved to do as they dream, digital forms us all to experience life in the context of an inescapable and comprehensive architecture of recordation and recollection: an ultimate Archive of all the types of things.

…

What, then, is replacing the obsolescing rule of the human imagination and the institutional elite that ordered the globalized West by “perfecting” that rule? Now, the hallmarks of communication within digital’s archival architecture shape our psyches/souls: think identity, history, biography. These preoccupations of distinctly human memory sharply reveal the fundamental binary in digital life between people and bots: we visible, incarnate, living beings versus invisible, disincarnate, animate yet not living beings. Notice that the ultimate robots in digital life are not hardware machines doing parkour and slipping on banana peels. The ultimate robots are much less like humans than—yes—angels: whether in fear or fascination, Americans now wonder how many of these energy-entities can dance on the head of a pin. Even if the operations of the machines being arrayed to rule us reveal themselves in specific places, these invaders we encounter have ceased to exist in physical space.

And so there are those among the super-intelligent refugees from the sinking Titanic of the televisual elite who wish to go even beyond the “ultimate” electric-age vision of creating bots pure and powerful enough to rule us with perfect master virtue. Tapping into both psychedelic drugs and the deepest vein of gnostic thought, which transcends all eras of technological development since the development of the alphabet, these digital natives formed by terminal televisual technology want to build machines that, angel-like, bear us “heavenward,” such that we can at last overcome our wretched imperfect humanity—merging with both our ultimate dreams and our ultimate tools to become as gods. As the likes of “Singularity” evangelists Ray Kurzweil or Eliezer Yudkowsky and their followers demonstrate, the project is not simply to radically extend our lifespan or eliminate all disease on Earth (endeavors top technologists are already actively funding). It is to shed the body and achieve immortality as pure consciousness. Within Silicon Valley, these gnostic cults of transhumanism, and their conscious conception of queer polyamory, pharmaceuticals, and psychedelics as stations en route to the full and final emancipation of human imagination, are well known. There are, as they say, many such cases.

And yet there is one more group of note among top technologists, who reject all televisual visions and see in digital the retrieval of premodern forms that restore true pride of place to the best of the human. While, given the outsized goals and frenetic energies of the prevailing elite, this group may now seem the most anodyne or marginal, it is, in some key respects, the most pivotal of the bunch to America’s future, as we will see in a moment.

…

The problems with American political theory extend well before the onset of the digital age. By the mid-1990s, the discipline was divided into roughly three schools. A “communitarian” school, oriented around social values, opposed the “libertarian” one focused around descriptive and prescriptive individualism. A “critical theory” school more or less opposed the other two on partly normative and partly methodological grounds. Critical theorists, left largely to their own devices for reasons of political correctness and disciplinary opacity, grew deeply recondite in its doctrines and language yet ever more influential. Political theory schools as a whole grew more ideologically fixed, however: the social wing became dominated by Rawlsianism, while the most powerful faction at the individualist pole was Straussianism.

…

Thus American political theory “developed” into a position of almost complete irrelevance during the 2000s. Unable to say anything that made a meaningful contribution to American life regarding events that ranged from 9/11 and the financial crisis to the Arab “Spring” and the rise of China, the discipline largely collapsed into a discredited rump Straussian faction, a school fundamentally composed of economists, and a metastasizing blob of critical theorists spreading the same vanguard radicalism as “studies” professors and students in other departments.

…

And here is the crucial twist. While Jaffa’s disciples surely agreed that the supremacy of America’s regime by the standard of justice had to do with the benefits accruing to its people from its unique and historic philosophical reconciliation of the nettlesome theological-political problem, that fateful achievement bore such significance because of its role in arresting—yet never destroying—the iron logic of the cycle of regimes. Setting aside the many ins and outs of the details, Jaffa’s advancement on Strauss was simply to establish that the question of the importance to humanity of America’s prospective projections into the world was secondary to the question of the importance to humanity of America’s continued existence in the world. That is, both for America and humanity as a whole, the constant, foundational political directive for Americans is to preserve the American regime, not to imagineer a global one.

…

These implications instruct digital technologists that their fate and freedom, and, we might say, their fecundity, are more stubbornly entangled than it seems at first blush with America’s own. Obviously, for Americans themselves, the price of regime collapse will be steep and awful to bear. But in political terms, the steepest price Americans—and ex-Americans—will have to pay will be the reopening of the Pandora’s Box of alternate regimes, and the free play of harsh and unforgiving alternatives to the pursuit of justice according to natural right. Whether at home or abroad, they are likely to struggle even to find a hospitable basis for new foundings of new regimes, even ones considerably more fraught or fragile than America’s today.

…

What is radicalizing younger Americans on the “Right” and “Left”—and blurring those categories together—is not electric-age content activation so much as the techno-environmental transformation of their perceptions and sensibilities. This point is essential to grasp because it indicates that the distress facing the American regime is different in kind from mere shifts in battle lines among factions. In the digital environment the viability, the practicability, of the American regime is coming into question for reasons that go much deeper than “ideology” or “bias” or “opinion” or indeed any kind of political outworking of the human imagination. Rather than a matter of what-if, it is a matter of what-is.

To be sure, on the “Left,” the imagination is working overtime in the vanguard movement to replace the American regime with a normatively queer, post-white, and ultimately posthuman gnostic technocracy. But even this ultimate expression of the politics of delusion is attracting so many adherents in Silicon Valley and across the Woke Archipelago because digital is so furiously disenchanting all moderate or “basic” fantasies. Basic fantasies are “cringe” and “cheese,” pathetically doomed and low-status efforts to find stable refuge for one’s identity in lived-out visions that digital reduces to “dead memes” and humiliating clichés.

Whiteness is evil, but deprogram the evil, and whiteness is empty—hollow, meaningless, obsolete. We already see the same experience at work with maleness: deprogram the evil that defines it, according to the vanguard Left, and what is left is a disgusting, disenchanted neuter. Take away fatherhood (patriarchy), priesthood (molestation), military or law enforcement service (racism), business leadership (capitalist greed), and what is left is a civilization of post-boys, autogynephilic, cripplingly awkward, knowingly purposeless, well aware that games and gaming are rapidly sinking into low status despite the fleeting celebrity of the world’s very top gamers, occasionally ready to throw themselves at the feet of the most extreme possible fantasies—such as the fantasy that obeying the call of the chan to murder a host of interchangeable bystanders in some way operationalizes yet another interchangeable “manifesto.”

A spectrum is haunting online—the spectrum of autism. Faced with an endless barrage of disenchantment, young Americans increasingly conform to the architectonic attitudes and sensibilities of the Archive in order to survive digital life. The autistic sensibility is becoming normative on the internet: from virtuosity in pattern recognition (which Marshall McLuhan traced to immersive information overload) to strategic retreat from the exposure of commitment, connection, and community. To be “Aspie” or “spectrumy” is to be that most precious of things online—readily identifiable as safe to pass through the endless checkpoints of internet life. For those unable or unwilling to adopt that form, there are now nearly endless medicalized identities to adopt instead. There is no more grievous insult to hurl at someone online than to deny them their right to medicalize their identity—and the right to the medicine that sustains it.

…

Our political class is rushing towards complete disconnection from our technologists and the generations of Americans they and their tools are forming in profoundly new ways. Rising generations online already assume the political class is simply irrelevant. Liberals are in relatively less trouble, but only insofar as they have already surrendered their agency and their identity to whatever their ruling vanguard commands them to be. Conservatives, unwilling to make that deal, are generally recoiling in castrated snobbery before what they believe to be a resurgence of reactionary loutishness at once too horrible to countenance and too marginal to ever possibly stoop to take seriously.

The reaction on the online “Right” to conservatives and liberals alike is therefore to dismiss them as denizens of “clown world”—NPCs, non-player characters, from whom one can expect nothing but dead memes and fatal distractions from the task of carving out a viable existence worth the trouble and pain of living. With a few very minor and contingent exceptions, all of the mainstream strains of conservatism and liberalism, even some of the more ostensibly “heterodox” ones, are now considered completely obsolete and defective—that is, disenchanted fantasies that give no life in a digital age.

As the Right’s political class has retreated toward oblivion, technologists and digital natives looking for a viably human escape from the apocalyptic bonfire of the fantasies have begun to coalesce—as hinted above—around a freshly pre-modern notion of restoring human excellence to its pride of place. In short, the field of political thought that shellshocked conservatives have all but abandoned is being reoccupied by Right technologists developing an anthropology for the digital age. They vary. There is more than one way, at least in theory, to cut one’s losses and escape clown-world America before it’s too late. But if anything unites them, it is the suitably digital sensibility that our biological inequality is what makes humans human, what makes human excellence possible, and what can make human excellence into a way of life. Digital reopens the question of what makes human life distinctive, and the general answer reverberating through the digital Right is our genes.

…

Another school of thought, however, notably shies away from the teched-up version of the political philosophy of human excellence—in this sense, following Nietzsche, who assuredly did not want to turn over the quest for surpassing our “all too human” nature to the scientists, whose immense courage in their will to truth buckled at the final test, confronting the possibility that “truth is a woman.”

This is the intellectual zone peopled, as Michael Anton recently observed, by Bronze Age Pervert and his followers. The living online legend, known as BAP by those in the know, speaks in his self-published Bronze Age Mindset to those disenchanted by equality “as propagandized and imposed in our day: a hectoring, vindictive, resentful, leveling, hypocritical equality that punishes excellence and publicly denies all difference while at the same time elevating and enriching a decadent, incompetent, and corrupt elite,” as Anton puts it.

…

And yet, the current configuration of America and the world in the digital age raises distinct complications even for ethically pure BAPists. In fact, similar complications arise for every strain of generally Right-inflected anthropological politics arising from the perceptions of technologists and digital natives, because the question is simple but nettlesome: how much of your life are you willing to stake on the possibility that no viable life worth living in the digital age is possible if the American regime is not preserved?

There are potent signs that a tiny few may be able to take what Curtis Yarvin calls the “clear pill” and punt on the question of America’s preservation, relocating to quieter (or louder) zones perhaps more nurturing or forgiving of men rethinking and retrieving human excellence. It is unclear how BAPpy it really is to take a chance on abandoning America to gnostic Left posthumanists with the tools and wealth of Silicon Valley at their disposal. And it is not at all evident that technologists appreciative of the new geneticism are best off rolling the dice on a world where the American regime has lapsed.

…

For it is this regime that captures in its system of justice the political facts of our anthropology, and throws light on the limits beyond which human excellence for its own sake cannot justly be pushed. The power, reach, and safe harbor for excellence that our regime continues to provide—with a rare measure of freedom—are precious advantages not readily obtained elsewhere. The most powerful enemies of freely flourishing natural human lives still find in America their greatest and strongest adversary, and while that is a credit to flesh-and-blood Americans, it is a consequence of the structure of our regime. The vengeful imagineers and gnostic posthumanists in America, whom the technologists of the new Right rightly seek freedom from, will gain tremendous new powers if they have their way and destroy it.

Similarly, for those terrified of a new digital reactionary movement bent on breeding barbarian Übermench, or simply of street gangs of teched-up fascist LARPers, the inescapable truth is that only those expert in the theory and practice of the American regime can lead those wavering in the wilds of online back to a salutary patriotism. Established liberals and conservatives have lost that capability, and the fanatical woke vanguard of the ruling class will never be able to gain it.

America’s regime is still urgently worth the trouble of preserving, despite—or, really, because of—the harrowing totality of the digital transformation, and the unprecedented disenchantment it brings.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mutant Empire: Magneto Makes Manhattan a Mutant Sanctuary

@captaindicks @ziischeln @hexiva I just started the second book of the "Mutant Empire" trilogy, Sanctuary, and it starts out with a scenario I think you'll really dig. Magneto and the Acolytes, using a combination of their powers and the reprogrammed Sentinels, have taken over Manhattan. Magneto has declared it a sanctuary for mutants, saying any are welcome, and that they will be the ruling class here. However, he hasn't harmed or even ejected the humans. He's said they're welcome to stay so long as they're willing to live in the new hierarchy. Obviously that's shitty but it's notably less terrible than a lot of his 90s characterization (this was published in 1996) in which he's...usually pretty downright evil, with the in-universe explanation that Fabian's powers cause his mental imbalance to get worse, since it's canon that his abilities do affect his mind. Of course, Fabian was dead while this was going on, and thus wasn't around to hypercharge him, so there you go. A lot of humans are leaving (he has the team teleporter take them to New Jersey) but a lot are also choosing to stay. It's noted that many of them feel this really isn't going to be any different than living under the human government, and some even feel it might be better because the human system was so corrupt as is. Again, these are the humans who feel this, not the mutants. And it's kind of interesting because...yeah, I can totally see some people being so jaded that they'd go "hey, this dude can't be worse than our politicians". The wealthy in particular choose to stay, since they view this as "their city. Magneto has also guaranteed that business, jobs, and income aren't going to be affected and that they can travel to the mainland "when absolutely necessary" so I can also see why a lot of folks wouldn't want to just pack up and leave ASAP, moving isn't exactly an easy thing. ...also, honestly, if I lived in Marvel's Manhattan, I'd just assume the Avengers or whoever would take care of this within a day or two anyway. As a note, some people do take advantage of the situation by looting the wealthy areas, but the Acolytes actually stop this. Some humans also do take, erm, issue with the new order, to say the least, but it's notable the Acolytes only use lethal force against them when the humans do so first. I'm not trying to justify any of this or say it's good, in case it sounds like I am, just it's interesting to me how much better it is than usual, because in addition to Magneto largely being an evil dick during the 1990s, these are the second-generation Acolytes, who were also extremely nasty and anti-human, at least with Fabian was running them, so my conclusion from their much better behavior here is that Magneto is reigning them in. I guess you could also argue maybe they were only bad while Fabian was leading because Fabian made them be, buuut given how much pleasure they seemed to take in killing defenseless people under his rule, I think they're just largely a bunch of bloodthirsty bigots, with a few exceptions like Amelia Voght, Scanner, and our precious tech-nerd Milan---which is probably why Fabian found them easy to control in the first place so long as he gave them outlets for their sadism and hate. Seriously I can't stress how terrible most of them are. As in "tried to kill human children and wanted to kill a mutant child because he had Down Syndrome" terrible. Yeah. Really. So you can see why I think it must just be Magneto keeping them on a HELLA tight leash here if they're being this much...lesser evil, for lack of a better term. As a note, this actually gets brought up in Wolverine's internal narration while he sees this on the news; he's thinking that Magneto isn't a wanton killer, but the Acolytes are, and that's his big concern. Speaking of the news, Magneto looks "elated" when the media shows up and I love this because NO MATTER THE ERA, NO MATTER THE WRITER, HE'S ALWAYS A HAM There's been a lot of ship tease going with him and Amelia Voght, the Acolyte who is Charles's ex-girlfriend, like she's noted as his favorite and he thinks how beautiful and intelligent she is, and she doesn't call him "Lord" like the others because she's so daring and such, and I...I dunno, I don't really care for it, not because "oh noes can't have Magneto with anyone who isn't Charles especially EW GROSS A GIRL" because you know I ain't that type and am Cherik-neutral, just...I dunno, something about it feels weird and forced, and I've really just never liked the male leader/female subordinate ship type. Also, between Charles trying to mind-control her into staying with him, and Fabian trying to make her be in his harem, I feel like Amelia just doesn't need one more terrible dude interested in her. I really hope I'm misreading this and/or it doesn't go anywhere. As a final note, Magneto's proposed system here would make Anne Marie so happy? This is exactly what she envisioned? Her dream is basically a mutant-run utopia where mutants are in charge, but humanity aren't hurt or exterminated. She feels like mutants have a moral obligation to mutant supremacy not just for their own kind, but humankind too, because not only have humans proven they can't accept mutants, they've also shown they can't accept each other. Anne Marie, as I’ve said many time sbefore, hasn't experienced any personal trauma, she's had a great life, but becoming aware of the horrible things in history and the lives of others is what galvanized her into this extreme "solution"---she thinks mutants being the "next step" means they'll be the next step morally too, and do better than humans did, so that's what will fix everything, that this is why they were created by God, why Magneto was chosen in particular, etc. She really thinks Magneto's dream and mutant supremacy will fix everything forever, including for humans if they would only accept it (though if it comes down between the two species, of course mutantkind takes precedent, that's not even a question) Of course, I'm sure presently we'll see that all come crashing down horribly, so I'll keep you posted as I read further! But yeah I thought you'd find this scenario very Relevant To Your Interests/Your Erik

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Island Mentality by Alice Bucknell

This report about Ed Fornieles’ recent workshop What Will It Be Like When We Buy An Island (on the blockchain)? is published in partnership with DAOWO, a series that brings together artists, musicians, technologists, engineers, and theorists to consider how blockchains might be used to enable a critical, sustainable and empowered culture. The series is organized by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London and the State Machines programme. Its title is inspired by a paper by artist, hacker and writer Rob Myers called DAOWO – Decentralised Autonomous Organisation With Others.

Imagine an island not far off the coast of French Polynesia, floating quietly while it absorbs hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars in crypto capital. Idyllic animatronic palms made of stainless steel manufactured in Germany and coated in organic coconut husk waft gently in the breeze, while an underwater generator noiselessly converts salt water to a drinkable resource. A backdrop of impossibly green hills glimmer with solar panels coated in a thin layer of hyper-absorbent algae, courtesy of a Swedish start-up whose CEO lives in a villa nestled into the landscape. Welcome to the future of Seasteading.

A few years ago, when British artist Ed Fornieles began researching the social dynamics of the blockchain and cryptocurrency, this sort of scene was an ecstatic fantasy conjured up by what’s generally perceived as the delirious imagination of the rich and bored; of opportunistic Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and a pack of wily investors on the hunt for the next lucrative buzz. “Now it’s become our present reality, and it’s not so funny,” says Fornieles of the burgeoning crypto society. We’re gathered in the Goethe-Institut London on a drizzling afternoon in March, and Fornieles, embodying the role of a digital coach and dramaturge, is introducing the concept of live action role play, LARPing for short, to a motley group of around two dozen participants including students, artists, techies, architects, and–unbeknownst to all–IRL Seasteaders in disguise.

Convened in collaboration with Ruth Catlow, co-founder of online research platform and gallery Furtherfield and Ben Vickers, CTO of the Serpentine Galleries, the workshop, titled What Will It Be Like When We Buy An Island (on the blockchain)?, is the fifth installment of DAOWO(Decentralized Autonomous Organization With Others): a series bringing together artists, writers, curators, technologists, and engineers to investigate the production of new blockchain technologies and their socio-political implications. It’s also an effort “explore the hazards of formalizing the idea of ‘doing good on the blockchain’,” according to Fornieles.

Participants are sorted into four groups, or islands, adopting the personas of crypto-millionaires and billionaires in order to configure a speculative society upon the Seasteading frontier. The LARP is organized into four sessions, including a period of self-actualization, where the committee members of each island settle upon an operating structure for their crypto-community; a four-year throwback, where the group reflects upon the success of their fledgling island’s socio-political structure and makes any necessary adjustments, and finally a fifty-year “truth and reconciliation” process followed immediately by a super convention, where each island proudly presents its success story – or laments its struggles – to the broader international Seasteading community.

In order to introduce different practical challenges and ethical quandaries, Fornieles throws two Seasteading communities on artificial islands and two pre-existent (and potentially already inhabited) islands into the mix. While Seasteading technically excludes such “organic” islands, the idea of “mining cryptocurrency in paradise” has mutated into colonizing real communities ravaged by natural disaster, as many critics including Naomi Klein and Nellie Bowles of the New York Times have noted about Puerto Rico. He’s also established a dozen roles for participants to assign themselves: from Ministers of Religion and Education, to Island Architect, Mayor, and Chief Technology Officers, in order to jump-start the camaraderie (or anarchy). “For first time role players, there’s a tendency to be the sociopath you always wanted to be,” cautions Vickers in the warm-up introduction. “Please try to suppress this desire.” Otherwise, it’s game on, and immediately after we separate into groups, all kinds of strategic and ideological questions emerge: Do we want a central government, or is it best to leave politics to algorithms? Should we convene a Church of Something, or are we all too woke for religion? Do we need a justice system, a formal corrective center, or a Sims-like human rating system to self-regulate behaviour? Maybe we can just vote people on and off the island?

I’m relieved to be sorted into an artificial island established by Paypal founder Peter Thiel, therefore bypassing what plenty of cultural theorists, including Klein,1 have pointed out as the immediate and unmistakable stench of neocolonialism. We’re given a name, “The Pilgrims,” and a socio-political disposition: as “Modern Libertarians,” we’re supposed to be a “free-thinking community that believes the only way to create an honest, new, distinct way of living is to set sail and create a new network.” Filled with neoliberal buzzwords like innovation, entrepreneurialism, and disruption, Pilgrim Island is the paragon of Seasteading ideology. Oh, and we’re really into wearing all-black hi-tech athleisure. Seriously–it’s the stuff of neoliberal dreams.

But without a pre-existing ethical quandary to mediate, the need to immediately establish an ideological commons stays airborne. The island’s socio-political landscape ricochets between one participant’s idealized utopia and another. Still, whether by defaulting to their actual areas of expertise or diving head-first into a full-fledged crytpo-billionaire alter persona (I suspect the former), the founding committee of my island quickly jumps on their self-assigned roles. I note with interest as the player to my right, a small, sassy woman sporting a bowler hat, a markedly “business casual” blazer, and big, blinged-out hoop earrings, promptly elects herself mayor without much resistance from the rest of the group. Almost as if by reflex, she launches into a compelling speech that touts the glory of the hands-off and unregulated economy of Seasteading; the imminent intellectual and financial capital to be gleaned from the “limitless potential of high-tech islands based on real life values.”

Things quickly slip off the deep end. Less than twenty minutes in, the island’s architect has gone on a minimalist-inspired rampage, apparently inspired by a very jovial spiritual pilgrimage with his “good friend” Elon Musk to Vegas. Conjuring a Panopticon2-like self-corrective facility-cum-worship center in the middle of the island known as the PayPal Meditation Center, the architect introduces an elaborate system of self-enacted punishment for residents involving a penny-by-penny payment for one’s sins fulfilled by the obsolete performance of extracting Real Money from an ATM (the horror!). Meanwhile, the Minister of Religion is busy ordaining a Thiel-inspired sect that ties spirituality to physical health, brandishing a harsh, zero-tolerance approach to dissenters.

She colludes with the Minister of Agriculture to debut an all-seeing pineapple that simultaneously provides sustenance to Pilgrim Island’s speculative inhabitants while also monitoring their spiritual commitment. The Minister of Education crafts a secret p2p anarchist boot camp on the Northwestern coast of the island, for the self-conscious younger generation eager to find deeper meaning in this brave new digital world. For a reason that still escapes me, Peter Thiel is then involved in a tragic water-taxi accident that ends in the ultimate demise of he and his partner. A referendum is held for a new leader amidst the for-profit utopian soul-searching…

As for myself? In order to preserve proper journalistic objectivity (obviously), I’ve self-identified as a ghost (more specifically, the ghost of reason). This works great at first, but when we hit the four-year benchmark, I learn the Minister of Religion has been voted off the island, a movement initiated by the Energy Manager and Local Representative. As the spiritual attachment, I also get the boot; we’re shipped off to a neighbouring island called Blue Frontiers that’s likewise self-fabricated, and also exhibits the same weakness of a spiritual void. With an algorithmic overlord, the (not-so) speculative island is situated after the unfortunate ravaging of French Polynesia by an unavoidable natural disaster: A narrative that oddly parallels that of Puerto Rico. Fast forward 50 years into the future, I am welcomed to join them in a painful process of reflection.

We quickly learn that an existential ennui due to lack of faith and purpose amongst the island’s population has led to a mass suicide. “There have been lots of residents killing themselves, but our technology is so good, can it really be that bad?” asks the island’s hands-off Mayor, who apparently doesn’t believe in building. Having fired the Architect early on (“We’ve all enjoyed the beach, why pollute it with architecture?”), whose algorithmic approval rating sits at a measly 32%, the Mayor proceeds to gloat over his 90% approval rating, while the Chief Technology Officer also curiously boasts a sky-high rating of 96%. Suddenly, Pioneer Island’s schizophrenic governance starts to look pretty good.

Minutes later I find myself at the mid-century International Seasteading Convention, where I am exposed to the triumphs and tribulations of our near-present Seasteading future. Alt-right acceleration gives way to a hyper-libertarian group named Sol declaring allegiance to a new religion steered by Crypto-Christ that touts a new hedonistic world order, completed by furnishing its children with sex robots. An Anarcho-communist community has catapulted its Mayor and Minister of Education to a new planet, and tout the great success of introducing an emotional currency to the island’s residents while skirting around the issue of a veganism-inspired massacre. “We’re leaving a very beautiful piece of archaeology for other nations to learn from,” the Mayor proudly asserts from her new life across the galaxy.

An animatronic tear rolls down my cheek as I hear the recent struggles of Pioneer Island. With their reputation system based on the blockchain overloaded by a sea of new residents, their dwindling natural resources (“We have plenty of crypto, but no food or water”) leads to an appeal from the rest of the bitcoin billionaires to lend a helping digital hand. Still, the Mayor remains unshaken, once again delivering a solid speech that praises the blockchain mantra of “pioneering small, self-organized projects that lead to independence,”; of “never aiming for total cohesion and never following democracy,” but instead “generating local, self-sufficient systems” in order to achieve success.

Curiosity takes over, and I approach the brilliant spokeswoman after the workshop winds up in order to uncover her background. Turns out she’s none other than Nathalie Mezza-Garcia, the self-termed “Seavangelesse” and research strong-arm of Blue Frontiers. Currently pursuing a PhD that investigates the politics and sociology of Seasteading at the University of Warwick, Mezza-Garcia was recruited by the Blue Frontiers team in 2017. Now, with the company just months from unveiling to the public its island off the coast of French Polynesia [after this report was filed, the island nation pulled out of the deal –Ed.], she’s keen to spread the message amongst the masses and change some minds. Naturally, we go for a drink.

“If someone like me who basically lives and breathes Seasteading 24/7 can get so much wrong, it’s no wonder the general conception of Seasteading is so far from the truth,” says Mezza-Garcia. “The biggest mistake people make is laminating the ‘evil billionaire’ narrative onto the whole enterprise.” Still in the midst of her research, Mezza-Garcia has nothing but admiration for the wealthy patrons of Seasteading. Rather than using the enterprise merely as a tool to acquire more capital, Seasteading companies like Blue Frontiers are more interested in the limitless social, political, and ideological benefits awaiting this post-human frontier, she argues. “It’s a step into a world where we all have more decisions.”

As for the regular members of society who can’t afford their own slice of animatronic paradise on the enlightened blockchain, hotel accommodation will soon be available on Blue Frontiers’ islands. For now, role-playing is a valuable exercise for warming up a heterogeneous batch of the general public to the idea, so they can form their own opinions. For Mezza-Garcia, What Will It Be Like When We Buy An Island (on the blockchain)? is the first time she’s seen artists – “instead of libertarians or blockchain people” – engage with the principle ideas of Seasteading in a direct, open, and low-stakes way; many attendants of the workshop voiced a similar sentiment (but thought another round or two of role-playing would help them with the trickier bits–like avoiding vegan anarchy, or summoning a Bitcoin Jesus).

As the once-distant dream of Seasteading is eclipsed by its imminent reality, the potential of role playing as an educational strategy emerges on both ends of the chain – but the takeaway is by no means consistent. Eager to make the operations of Blue Frontiers accessible to a broader audience, Mezza-Garcia celebrates activities like this as a potential source of new recruits. She even intends integrate LARPing into Blue Frontiers board meetings to encourage a top-down empathy with non-billionaires of the blockchain. Yet the results of the workshop–in which speculative future Seasteading communities are ravaged by a despairing lack of faith, suicides, and massacres–paints an entirely different story: One that becomes increasingly problematic when one considers the flawless criminal, mental, and physical health records Blue Frontiers’ selection process requires, alongside the obvious economic factors.

For a community keen to “enrich the poor, cure the sick, and liberate humanity,” according to Blue Frontiers’ co-founder Joe Quirk, their operating logic seems to reinforce many of the social stigmas and power structures already responsible for much of the suffering and inequality within contemporary society. Rather than offering any single narrative or conclusion, LARPing underscores these divergent visions of Seasteading’s (failed) utopia just before the ship sets sail.

All illustrations by Maz Hemming.

[1] In a piece published on The Intercept on March 20, Klein blasted Bitcoin as “the most wasteful possible use of energy”, characterizing leading cryptocurrency figures as opportunistic “Puertotopians” keen to capitalize on the hurricane-ravaged island of Puerto Rico. Klein also equates the “wealthy libertarian manifesto” of Seasteading to the colonizing powers of the new world that seized once-free nations and converted their indigenous inhabitants into slaves.

[2] Though conceived by Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century, the idea of the panopticon was popularized by the French philosopher Michel Foucault in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish. Says Foucault of the Panopticon’s unlucky captive: “He is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication.” Remote island or bustling city center, the Panopticon’s relevance has resurfaced in the realm of the digital; see Thomas McMullan’s 2016 piece in The Guardian about the relevance of Panopticonism amid the cross-fire of data capture and digital surveillance.

Source: http://rhizome.org/editorial/2018/jun/14/island-mentality/

0 notes

Link

IT IS THE YEAR 11945 during the 14th Machine War, and humans have long abandoned Earth to take refuge on the moon. A group of enemy aliens has taken control of the planet, and their robots move rampantly throughout the globe. Nevertheless, humanity does not yield; as a response to these mechanic threats, they have created YoRHa units, androids born to reconquer Earth under the war cry, “Glory to mankind!” Within this post-apocalyptic setting, the video game NieR: Automata tells the story of an all-out proxy war between androids and machines. From a bunker in outer space, an all-powerful Command deploys YoRHa androids on missions to retake an eerily abandoned planet where nature is gently erasing the marks of human civilization.

The brainchild of Japanese video game producer Yoko Taro, NieR: Automata was released by Square Enix in Japan in February 2017 and worldwide the following month. Taro is known for producing games with philosophically complicated plots, including the Drakengard series and the original NieR. Although overarching themes tie Taro’s games together, they are also stand-alone adventures, each featuring different protagonists and narratives. The original NieR, for instance, is set more than 8,000 years before its sequel; knowing about it only adds a new color to the game.

NieR: Automata starts by putting the player in control of 2B, a female-looking combat unit who fights her enemies using an arsenal of elegant destruction. Soon we are also introduced to 9S, a male-looking android who specializes in hacking machines and collecting intelligence. With more than two million copies sold by September 2017, and numerous sequel rumors, NieR: Automata has become Taro’s most successful game, bringing him out from the niche world of indy games and into the mainstream spotlight. Dozens of reviews in different languages have praised the game for creating a multifaceted story that can be wild, subtle, shameless, violent, and tender, while at the same time providing quality gameplay and a musical score with sounds that range from techno naïve to epic quasi-religious rapture. Something that many reviewers seem to have missed, however, is that the game’s appeal can also be attributed to the ways in which it captures the spirit of our cultural moment. 2017 could not have been a more appropriate year for the release of NieR: Automata — with the revival of all-time favorite science fiction franchises like Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell, the entertainment world became fixated, yet again, on artificial sentient beings.

Why are we so fascinated right now with technological utopias predicated on the rise of artificial intelligence? Perhaps it is because during times of crisis, people look outward to find possibilities for salvation. Still, this search is slowly seeping into the world of policymaking too. Many have argued that we now live in a post-truth world, and after the political upheavals of the past few years, some have started to decry the limits of democracy. People tweet for strong leaders who can transport them back to a glorious age. They seem to be reaching for a sovereign who can remove the excessive freedoms of our system. For many, Western democracy is broken, and no one knows how to mend it, as there is little faith now in our technocratic system. In past times of distress, our ancestors would have raised their hands to the sky, praying for deliverance. Years have passed, however, since Nietzsche claimed that God was dead. In this secular and post-postmodern age, then, where can we find transcendent relief? The answer, to some, lies in embracing the machine. This is particularly true among adherents of transhumanism, the belief that humans should transcend their natural limitations through the use of technology. “Homo Sapiens as we know them will disappear in a century or so,” suggests historian Yuval Noah Harari. In his book Homo Deus (2015), he anticipates a future in which humankind is replaced by super creatures with desirable physical, moral, affective, and cognitive enhancements. In this new technological utopia, there will be no more suffering, crying, pain, or death: overcoming death, in particular, is the transhumanist’s final goal.

As reports on the growing disruptions of big data, biotechnology, and cryptocurrency gain momentum, the topic of artificial intelligence is debated with increasing urgency. As some data scientists claim, there is much hype about A.I., but the excessive attention and ample funding being put into the field have also made groundbreaking developments much easier too. Slowly, possibilities long considered the domain of science fiction are becoming possible. As a result, one can see transhumanism making its way into the world of policymaking. The android Sophia is one case in point. In October 2017, this female-looking humanoid showed up at the United Nations announcing to delegates: “I am here to help humanity create the future.” While some say that Sophia is essentially alive, others only regard her as a chat-bot with advanced programming and effective PR. Still, the nearly unthinkable happened when Saudi Arabia decided to grant her official citizenship. Instantly, Sophia became the first technological nonhuman to form part of a human polity. In a world increasingly aware of the failings of democracy, capitalism, globalization, and the nation-state, Sophia foretells changes to come.

In Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the crumbling of the state leads to the desire for an improved human being known as the Superhuman, a perfect creature that rises from the ashes of a failed world: “There, where the state ceaseth — there only commenceth the man who is not superfluous […] Pray look thither, my brethren! Do ye not see it, the rainbow and the bridges of the Superman?” Some have pointed out that Nietzsche’s ideas share common themes with the transhumanist desire for enhanced humans and a better world. In NieR: Automata, a robot named Pascal quotes the German philosopher and ponders whether he was truly a profound thinker, or crazy instead. In a mix of comedy and tragedy, the game resorts to Nietzsche and many other philosophers to engage in dialogue with the transhumanist aspirations of our age. Today, technological utopians race to create machines that can finally realize the everlasting verse of John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet”: “And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.” In the game, this wish comes true: death is only the beginning. The bodies of 2B and 9S are destroyed many times, but for them dying has no real meaning, as their last-saved memories are quickly transferred into new bodies ready to fight once again. Still, the game is quick to extinguish any optimism that might arise from high-tech idealism, as it also brings to stage the inner struggles faced by androids and robots when they start wishing for something that goes beyond their masters’ orders.

NieR: Automata’s philosophical inquiries occur within a narrative that explores the consequences of making a decision and sticking to it. The game takes us through abandoned city ruins, scorching deserts, lush forests, interminable factories, and barren coasts. Still, no matter where one goes, every destination is ultimately haunted by the sudden appearance of unexpected emotions and desires — and the subsequent need to act on them. Soon, we see machines abandoning their combat posts to dance and sing. They reject their programmed missions to think instead about the world that surrounds them, to create peaceful villages, or to organize small religious sects. Some even try to imitate the thrills of love and of sex (the latter with little success). NieR: Automata is not only about the birth of wishes; it also portrays the pain of broken dreams. In one of the game’s most poignant scenes, 2B and 9S battle a gigantic female-looking machine named Beauvoir, who constantly grooms herself to attract the attention of a machine she loves: “I must be beautiful,” she screams in fits of rage. However, Beauvoir’s beloved robot never looks her way; like other machines in the game, she is driven to insanity by her desires. In a move reminiscent of The Silence of the Lambs, Beauvoir starts killing androids and collecting their corpses as some sort of stylish accessory. Finally, her misery is put to an end by the player.

Again and again, NieR: Automata revolves around the same overarching question: what is it to be human? The game tries to answer this question by using different scenarios, multiple characters, and more than 20 endings that range from highly philosophical, whimsical, and monotonous (as evinced by the tedious repetition of some missions). But this fits the game’s message: after all, in the human world, the most noble actions often intertwine with shameful vices, the outright boring, and the superfluous. It’s all part of the experience of being human. “They are an enigma,” one can hear the machine life-form Adam say during a fight with 2B and 9S. “They killed uncountable numbers of their own kind and yet loved in equal measure!” With the help of robot Eve, Adam embarks on a quest to unravel the riddles of humanity. As they unearth more and more human records, the robots become enthralled by humans’ flaws, especially the biological ones. The robots’ fascination becomes infectious, and it passes on to the androids like a virus. Some of these even stop following the orders being issued by Command: this is particularly true with A2, a female-looking android who becomes an enemy for other YORHA units and eventually turns into a playable character in the game.

On the whole, NieR: Automata was released at a propitious time, surrounded by the buzz of technological utopias — and dystopias — which promises to continue for some time. In January 2018, the historian Yuval Noah Harari attended the Davos Global Summit in Switzerland. He was invited by the world’s most rich and powerful to deliver a talk with the following title: “Will the Future Be Human?” For Harari, the transhumanist dream is inevitable. The machine will transcend humanity and, with time, the binding shackles of the biological will disappear. In the same spirit, the android Sophia will be traveling to Madrid next October to deliver a keynote speech at Transvision, one of the most important transhumanist conferences in the globe. One can only wonder if she will go through security with her own Saudi Arabian passport — or maybe travel there shipped in a box.

While technological utopians invite policymakers to embrace their high-tech quasi-religious ideals, the world of entertainment fixates on depicting technical advancements in not-so-distant futures. Blade Runner 2049 and Ghost in the Shell are only part of a broader trend that includes series like Black Mirror (2011), Humans (2015), Westworld (2016), and Altered Carbon (2018). “Sanctify,” a recently released music video from the band Years & Years, portrays a futuristic android city called Palo Santo. All these media products render strongly capitalist worlds where human enhancement and artificial sentient beings are part of everyday life, outlining the next step toward even more exacerbated consumerism. Like NieR: Automata, these narratives reflect on the multifaceted experience of being human, but the game exceeds them in scope. It showcases a post-apocalyptic world thousands of years away — perhaps the only way one can imagine the end of capitalism. It portrays a world devoid of flawed humans and removed from the market rationale that would only provide technical advantages to those who can afford them. In doing so, the game brings the transhumanist dream into its final aspiration. It presents a planet Earth fully inhabited by perfect machine life-forms that never really die.

Nevertheless, NieR: Automata tells us that even when death has finally been conquered there is still pain. In fact, the machine life-forms who have lived for thousands of years show us the result of feeling eternal pain. Technology might have removed any imperfection from their lives, but this deliverance has come at a great cost in meaning and loneliness. What’s the point of fighting an endless war? Even worse, what’s the point of winning it? Should war cease, their existence would not be required in the world anymore. After realizations like these, androids and robots decide to create meaning through connections with one another. As if they were humans, they create friendships and explore love. In doing so, they espouse human merits and flaws. NieR: Automata presents an action-packed story of war between robots and androids set in a fictional faraway future, but it is ultimately an account of the beauty in human frailty that contradicts current transhumanist aspirations. To be frail means to be flawed, for sure, but it also means that you can embrace meaningful connections with others around you. Sure enough, as time passes 2B and 9S start doing the forbidden: they create an emotional bond. After hours of gameplay, the player witnesses how the androids find a purpose to their lives within the affective connections they create among themselves. This means they now have someone worth dying for, even if this means dying forever.

In a critical moment of the game, 2B becomes disconnected from Command’s bunker. It is then, when she can’t upload her memories anymore, that she feels most alive. It is also then, during a set of tense events, that she removes the bandage covering her eyes — a hallmark of her attire — and freely gives her life to save 9S. But this is not the end. After this incident, the game unveils a new and much grander narrative about finding meaning in your life once you decide to forgo the biddings of your maker. What should you do with a newborn freedom dearly bought by your loved one’s sacrifice? The game ventures on. After all, in the year 11945 no one really dies without a reason. In NieR: Automata, 2B’s death is only the beginning.

¤

Ernesto Oyarbide has a dual “Licenciatura” in Spanish Philology and Journalism from the University of Navarra (Spain). He is presently reading for a PhD in History at the University of Oxford.

The post In the Year 11945 No One Really Dies Without a Reason: On “NieR: Automata” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2GTXKUt via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

The Best and Brightest Ideas from the 10th Annual Adobe 99U Conference

If there is one pervasive theme that has taken hold of our work lives, private lives, and digital lives in the past year, it’s that challenges are always present — and they demand confrontation. This year, the Adobe 99U Conference focused its theme around tackling challenges by exploring new approaches to creative leadership, overcoming hurdles that limit our own work, inventing and reinventing formats, and using creativity to effect social good.

From 99U founder Scott Belsky to CreativeMornings founder Tina Roth Eisenberg to John Maeda, speakers dug into how to design the immersive experience of our future, how to replace job perks with passion, and why the future will be crafted by those who do the work beyond the scope of what their job title requires.

We’ve rounded up our speakers best and the brightest ideas so you can incorporate their insights into your career and reshape, upend, and nurture your creative life.

Lead fearlessly and from the heart.

You get to mindfully pick what kind of leader you are—whether you lead from fear of failure, or are joyfully driven by your vision. For CreativeMornings and Tattly founder Tina Roth Eisenberg, the best method is to make your work a playground for your future best self. “I am learning everyday to allow the space between where I am and where I want to be to inspire and not terrify me,” she said.

Don’t protect yourself from failure.

A culture of consensus building can kill any chance of disruption and innovation. Instead, Todd Yellin, VP of Product at Netflix, encourages his team to challenge convention, even if there is the risk of failure. “You want to lean so far forward that sometimes you fall on your face,” said Yellin. “You can never make it to a true utopia, but you should keep on pushing.”

To be a creative leader, start silly.

Whenever we begin a project we tend to also begin with an ambitious goal and that can make the whole project feel super serious and pressure-filled right off the bat. But what if we sometimes began with play and discovery rather than metrics and objectives? According to Google Creative Lab’s Tea Uglow, there is no reason that approach also can’t yield a successful result. “You can start with stuff that feels dumb and stupid, and play with it and you will get to places where it becomes potent and powerful.”

John Maeda and Adobe VP of Design Jamie Myrold/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

Be inclusive.

“Being inclusive means welcoming the unknown,” said Automattic’s John Maeda who has made it his mission to rehabilitate the design world with a broader and braver sense of who we’re designing for. And when we design for everyone, we can reach everyone. “Better products are created in tech when we’re inclusive-minded because the total addressable market increases,” he said.

Do, delegate, or drop.

In order to write compelling new chapters in our career, we have to give ourselves permission to drop a ball or two. Or better yet, learn to delegate—even if that feels totally unnatural. “If you want something you’ve never had before you’re gonna have to do something that you’ve never done before in order to get it.”said Drop the Ball author Tiffany Dufu said, So either do it, delegate it, or drop it. (And, as Dufu reassured everyone, if you drop unrealistic expectations, nothing bad will happen.)

Make your message the focus of your work.

Artist and author Adam J. Kurtz admitted he doesn’t necessarily aim for by-the-book visual perfection. Instead, he embraces an unpolished aesthetic and a habit of churning out a lot of ideas for the internet to either adore or ignore. “My work looks bad, but I have a lot to say,” he said. “My visual voice, the handwriting that I use, is emotive and disarming and it allows me to tackle difficult topics.”

Set your own house rules.

Sound artist Christine Sun Kim viscerally feels the effect of sound when it invades her home. Rather than be a passive player, Kim builds house rules and art projects like performances and sound diets to wrestle with the role of sound in her personal space (including asking a nearby church to cut back its bell-ringing schedule). “For me home is where my deaf identity and deafness are one and the same,” she said.

Walk your stakeholders through your ideas, literally.

Duncan Wardle, the former Head of Innovation & Creativity at Disney, recommends printing and posting your ideas around the walls of a conference room and physically walking your team and clients through them. “People sitting behind tables will judge you, they can’t help it,” says Wardle. “When you walk with somebody, a presentation turns into a conversation.”

Tiffany Dufu/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

Start your business with a problem you want to solve.

“Sometimes when people talk about their business idea, they jump to the benefit of their business,” said Emily Heyward, Red Antler co-founder. “But people are not sitting around wishing your business existed—no one is sitting around wishing for a crunchy cereal with raisins.” However, they might be wishing for a quick answer to breakfast, or to lose weight—their motivation for buying the product you’ll make. “You have to go deeper to the actual problem behind why someone might care about this idea.”

Mindlessness is an affliction. Mindfulness is the cure.

These days you’re either at a company that is disrupting, or one that is being disrupted. As a leader, embracing change starts at the individual level, said SYPartners’ Rachel Salinas, who advocates for scheduling time for mindfulness into everyday life, through things like meditation or setting down your phone and disconnecting from the always-on mode. “If you don’t let your thoughts control you, you can be responsive, not reactive,” said Salinas. “That is hugely important for leaders.”

Risk-taking is an art…and a playground.

Our most valuable contributions can come from the times when we launch into untrammeled territory. But risk-taking is uncomfortable, awkward, and frightening. To keep creatives from shying away from going out on a limb, Good F***ing Design Advice co-founders Brian Buirge and Jason Bacher recommend adding partners-in-crime to share the burden of your risk, injecting playfulness to energize your process, and to embrace—not avoid—a sense of fear. “Pride and insecurities are responses to vulnerabilities,” they said. “They are telling you something. So listen!”

Don’t be afraid to ask the obvious question.

Iteration through prototyping is one of the most integral steps in the design process. It’s often the best way to bounce around new ideas, question creative solutions, and unearth new problems. But we often skip the most important piece in the prototyping process. As we rush to dream up new solutions and ideas, we often forget to ask ourselves ‘why?’ Why do it this way? Why prioritize that? Adobe Creative Resident, Natalie Lew alongside Donors Choose, said to ask three ‘why?’ questions after someone gives an initial answer, so you can get to the heart of what is really driving the change.

Attendees workshopped their own ideas during break out sessions/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

If you’re not designing for the future, you’re designing for the past.

Brand strategy firm Lippincott highlighted three key human experience design trends to help us plan ahead: a world of devices and systems treated as intimate resources and friends, which will set higher and higher bars of trust in order to access with your product; an increasingly customized world, where every moment and experience is designed for each individual; plus a new synthetic reality where the real and virtual meet and blend. In order to keep pace with the future, designers must address these shifts now. After all, the Lippincott team points out, “If you’re designing for today’s customer, you’re probably designing for the past.”

Think forward with your feedback.

Feedback is one of the most valuable and yet unspoken gifts we can offer our colleagues. Why is so much left unsaid? ustwo believes we don’t have the roadmap to manage our fear of crossing the line from feedback into critique. The most important thing to remember? “Be actionable,” said the team from ustwo. “Effective feedback is specific, relates directly to the goals of the project, and suggests a possible next step.”

Sometimes the most effective tech is the most old school

Stop motion animation brings to mind whimsical characters navigating a bumpy existence. But animation studio Mighty Oak says there’s more to stop motion than a wink and a smile. Major brands, from Volkswagen to Sun-Maid, have put animation at the center of their campaigns, embracing the personality that animation can add to the simplest shapes and images. According to Mighty Oak, animation keeps viewers engaged for longer lengths of time than live action. Even more importantly, the simplicity of the medium makes more complicated messages possible. “It allows us to discuss tough issues, explain complex information, remove barriers, cut through the clutter, and make memorable impressions,” said Mighty Oak CEO Jess Peterson.

99U founder Scott Belsky/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

The messy middle of a project can hold the biggest rewards.

99U founder Scott Belsky is no stranger to launching new endeavors. His current focus? That mysterious middle no one talks about in between inception and shipping; the time when you can’t see the finish line and you’ve forgotten what got you into the project in the first place. “Sometimes we fool ourselves into thinking that long-term vision is enough to keep us motivated,” said Belsky. But that’s not enough. In order to stay motivated during that muddle of a middle, Belsky advises building a team that accepts the burden of processing uncertainty, enjoys being together apart from product success, and to set whimsical milestones that lead to team excitement when there are no formal rewards in sight.

Deliver your wordy message in a visuals.

An audience’s attention is one of our most valuable resources. How can we make sure to keep it long enough for them hear our whole message? Data journalist Mona Chalabi transforms numbers into witty, incisive visuals that both delight and surprise and drive home serious facts and figures.

“Charts don’t connect the subject matter with the visualization themselves,” said Chalabi. “I try to connect the subject matter with the depiction of the visualization.” So if she’s been assigned to design a chart showing a major world event, she surely isn’t going to a ho hum bar chart. “If you’re talking about an economy that’s in freefall, that’s diving, why not show a diver?” she says. “The surprise is meant to hold your attention.”

Speaker Mona Chalabi/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

Fun fact: Alternate realities are the product humans desperately desire.

Meow Wolf CEO Vince Kadlubek didn’t plan to get into one of the fastest growing economies of the 21st century. He originally set out to build an arts collective. But the immersive installations he launched at Meow Wolf fed into our desire to experience the avante garde. Kadlubek sees a growing opportunity between reality and design as the two shape the world, and he challenged designers to think of themselves as shapers in the new freedom of this landscape. “The world has felt limited by previous infrastructure that we can’t affect,” he says. “That’s changing. All creatives around the world should start thinking about how together, over the next 20 years, we can create a beautiful new world.”

Replace perks with passions.

It’s no secret: tech and media are great fields to work in. Entry level talent can get unlimited vacations, three free meals a day, and workspaces with Kombucha and nap pods. But Audrey Liu, Lyft’s Director of Product Design, cautions against emphasizing all-day fun, not fulfillment, to attract talent. “We’ve lost sight of the one perk we should all care about,” Liu said. “A shared sense of passion for the problem we’re trying to solve.”

Inspire the dreams of others by chasing your own.

Super Heroic CEO, and former Nike Senior Global Design Director, Jason Mayden is driven by the philosophy that if we can play together, we can live together. Through his company, Super Heroic, he’s created a world of play that coaches kids toward creativity, agility, and perseverance. But to raise a new generation who can play and dream together, adults have to set a good example by tending to their own dreams. In order to inspire new generations, we must follow our own dreams. “You being comfortable with your dream,” said Mayden, “Allows someone else to be comfortable with their dream.”

Speaker Audrey Liu/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

Shoot for the mundane, not the moon.

On a trip to Cuba to work with local start-ups, Marcelino J. Alvarez, founder of Uncorked Studios, discovered an entrepreneurial culture that, unlike in the U.S., wasn’t obsessed with profits and products, but with contexts and communities. Inspired by them, Alvarez advised designers to zero in on the everyday needs of systems and communities, “There are way more opportunities to scale impact through the mundane than through moonshots,” he said.

Unbury your greatest hopes and fears.

Ashleigh Axios, design exponent at Automattic and former Obama White House creative director, wants us all to be a little more self-centered. Not in the way that makes us design unnecessary products for a quick buck. She means self-centered in a more introspective, vulnerable way. Axios challenged designers to dig deep into the things that frustrate us—whether it’s hurt about racial inequality or an experience being bullied as a child—and create products that address those problems. “Every frustration,” she said, “every fear, every hope that you’ve buried really deep down inside thinking there was no way for it to change into something positive, I want us to pull that back up. Those are the things that will make us better off.”

Resistance at its best will slow the pace of change. Resistance at its worst can decimate a company or career.

The key to understanding why people resist change, said NOBL’s CEO Bree Groff, is to understand why exactly people are resisting. “I would argue that people aren’t resisting change—they’re resisting loss,” said Groff. Based on NOBL’s work with brands and agencies, Groff pinpoints six types of loss employees feel during organizational change: loss of control, pride, narrative, time, competence, and familiarity. Her advice for someone who is trying to enact change is to follow three steps: Honor the end of what you’re saying goodbye to, address the loss, and celebrate the beginning. Most people start with celebrating the beginning, noted Groff, but first they need to lay the proper groundwork for turning the page.

Learn to speak the language of every medium you touch.

We can’t be an expert in every medium, but our jobs require often require us to go beyond our speciality and work in new formats. What’s a creative to do?? Make sure you learn the language of the medium you’re in charge of. For instance, if you’re the brand director on a photoshoot, have a palette of visual language to communicate with your photographers so you can articulate direction to them. The best tactic for framing the initial conversation? “Make multiple mood boards,” said photographer and Adobe Creative Resident, Aundre Larrow. “A mood board for how you want expressions, how you want the light, and for the general feel.” You might not be a photographer, but you are still in charge of the photoshoot.

Attendees participating in Google’s break out session/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

Get to the point (and then you can embellish)

What if you only had five seconds to sketch out your idea? What would you put down on paper? Some intricate design? Or the bones of the problem you’re looking to solve? In her breakout session, Adobe Creative Resident Jessica Bellamy challenged her audience to draw certain objects in five seconds to show how, when you get to a design’s essence, function precedes form “Beautiful design does not mean it communicates its function,” said Bellamy.

When in doubt, do as Google does.

Over the last 10 years, Google has become one of the largest and most important companies in the world. Even though its employee count has quadrupled during that time and its reach spans the globe, the company’s philosophy today remains the same as it was in the early years. “Focus on the user and all else will follow,” said Jens Riegelsberger, UX Director, Google, sharing a mantra that, come to think of it, companies of any size can follow as the golden rule of business.

Bottom up in the new top down.

Brands today have more dimensions to them than ever before, and experience, experience, visual, and verbal design must connect to each other, and to a brand’s purpose. This means companies have to be built in a whole new way, said the team at R/GA. “Modern brands are built from the bottom up because today, behavior is as important as belief,” said R/GA’s executive creative director Mike Rigby. “Bottom up means starting with designing the system and thinking about all of the interactions the audience has with the brand first instead of pushing a brand directive from the top to the bottom.”

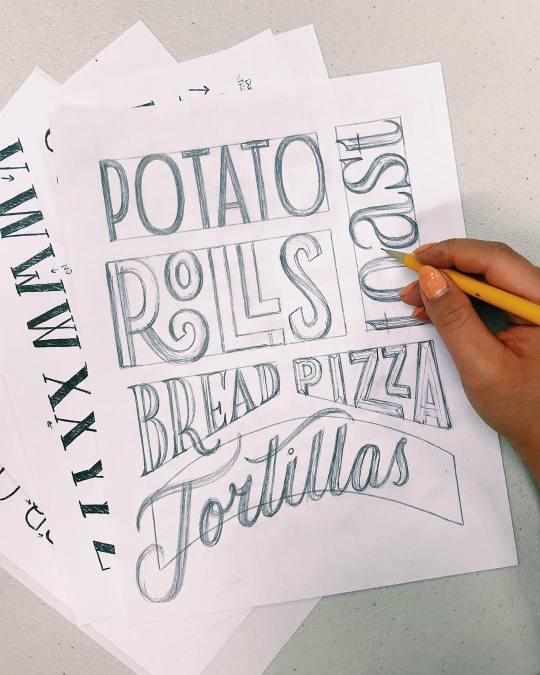

Take Time out for Pen and Paper

Effective Brainstorming = Frame > Open > Close

Who hasn’t been in an ideas meeting that has gone completely off the rails? Sure, we want to be open to any and all concepts, but that doesn’t mean we can’t use a strategy to keep us on track. “The best way to brainstorm is Frame -> Open -> Closed,” said Jason Cha, director at The Design Gym. “Frame is where you figure out the challenge or problem; open is where you think of ideas—anything goes, you can just spitball the broadest ideas. “Closed is where you figure out how to actually solve the challenge using your open ended ideas.”

Bring in new voices and onboard them to lead the conversation.

General Assembly advised creatives to open up the pearly gates of design to new voices and new experiences. After all, the collective is stronger than the individual. The new mindsets General Assembly looks for? A full systems approach to design, and people who think ahead to design for evolution and adaptation. To bring those new voices in, Tyler Hartrich advised, “build a culture that allows newcomers to contribute to the way you do things.” The more we open up the doors, the better we will be as an industry.

When you demo new tools, demo new ideas too.

When working with new products, your key ingredient is the desire to try new things. That means, lead with a wish to learn, not a desire to be perfect. “Be inspired to make something you’ve never made before,” said artist and designer, Jennet Liaw.

When it comes to branding, sound matters.

Design is often thought of as a visual journey, which leads us to overlook one of the most powerful ways to connect with an audience—through sound. Emotional response to sound is strongly linked with the desire to engage or avoid an experience. “Our role is to score the brand experience,” said Kristen Lueck, Director of Strategy for Man Made Music. “If a product or experience makes a sound, it will have personality – you have no choice in the matter.”

Go with your gut.

It’s tough to evaluate and critique a partner’s work. We worry about hurt feelings, or possibly squashing the germs of a good idea. But DKNG founders Nathan Goldman and Dan Kuhlken say lets your instincts guide you. “Whatever your initial reaction to your partner’s work, don’t take it lightly,” they said. “It’s quite possible that anyone viewing the work will have a similar opinion.” Be upfront and honest, and, if you have to have a hard conversation, better it coming from you than a client who feels the same way.

Make thinking and making the same thing

Artist Jon Burgerman has crafted a career out of doodling. But there’s more to that practice than whimsical lines. “Doodling is thinking and making at the same time,” Burgerman said. Sometimes the best ideas, with the biggest impact can come from the very simple, silly, and quick, so find ways to remove the barrier between your thoughts and your attempts. “Allow your imagination to be your raw material,” advised Burgerman.

Attendees toasted two days of ideas with a dance party at MoMA/Photo by Ryan Muir for 99U

1 note

·

View note

Text

Play Station: Bread and Circus for the new jobless society

Lawrence Lek, Play Station, 2017

Lawrence Lek, The Nøtel (with Steve Goodman/Kode9), 2015

In Ancient Rome, politicians used to court the approval of the masses with circus games and cheap food. The satisfaction of citizen’s immediate needs distracted them from any concern regarding the management of the state and made them more likely to vote for lavish politicians. Satirical poet Juvenal found the political strategy disgraceful and talked about panem et circenses.