#so he seems very well-suited to plucky space-adventure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Bianca Nureyev Detective Agency

This was an anniversary present for my wonderful girlfriend @spiky-lesbian who is just the most wonderful girlfriend ever and I love her a lot!

Juno tries to entertain his and Nureyev’s daughter on a slow day in space...

------------

Being a space pirate did sound good on paper. It sounded like a life full of narrowly dodged laser bullets, sprawling on beds of golden creds, witty one liners delivered to fallen foes in the smoking ruins of their empires that you’d just toppled and large, audacious hats.

And it was like that, about twenty percent of the time. But what they didn’t tell you was that the other eighty percent was a hell of a lot of waiting. It was a lot of snail crawling through deep space, killing days upon days worth of time in cramped metal hallways, eating stasis food and absorbing simulated sunlight. Planning your next big twenty percent could only take up so much time.

And it only got harder when you also had a three year old space pirate to entertain.

“Mamaaaaaaa,” Bee Bee poked her head up over the edge of the sofa, looking like some burrowing animal resurfacing, “I’m bored.”

Juno lowered the case file he’d been reviewing, eyeing his daughter with the tired amusement only a parent could muster, “Oh?”

Bee Bee scrambled up onto the family room’s busted old soda, sinking down beside her mama. She peered at him for a moment, taking note of the way he was sat, one ankle folded over the other and tried to copy him as best she could with her chubby little legs.

“Space is boring,” she declared, “There’s nothing to do.”

Juno set the files aside, silently accepting that he wouldn’t be getting back to them anytime soon, “Nothing? Nothing at all?”

“Nope,” his daughter gave a forlorn sigh, “Nothing at all.”

“Well then,” Juno shrugged, sinking down into the sofa so they were level even if it would be murder on his back later, “We’ll just have to think of something to do, won’t we, kiddo?”

Bee Bee giggled, “Yes. What was mama doing?”

“Oh,” Juno looked to the files he’d piled on the arm of the sofa, “Nothing interesting. Just looking into cases where other people have tried to do the same job we’re going to do.”

“And what happened to them?”

Juno winced. It wasn’t as if their daughter was unaware of the dangers they faced in their line of work. Pirates weren’t exactly famous for operating within the confines of the law, even in her storystreams. And since she’d been born, she’d seen her daddy at work, often getting a birds eye view of it all from a wrap slung across his chest.

“Well. Jail mostly,” he admitted, knowing he didn’t have to hide the truth from her even if it didn’t feel good to.

“Huh,” Bee Bee hardly blinked, swinging her legs, “Well, Auntie Buddy’s way way smarter than all of them. And Auntie Vespa is faster and Auntie Rita is better and Uncle Jet is cooler and my daddy is the best at stealing ever ever in the whole galaxy. And my mama’s the best detective. So we’ll do just fine.”

Juno grinned, reaching over and stroking back her curls, “Yeah. We’ll do just fine.”

“So can I help Mama? With being a detective?” her eyes sparked excitedly.

He knew that look, once her mind was fixed on something she’d follow it to the far side of the universe. She was like her daddy in that. But she wouldn’t exactly find much interest in going through old case files that somehow managed to make jewel heists sound boring. Though the tactics these failed thieves had used didn’t have an awful lot of pizzaz to them. Probably why they’d flopped, or at least that’s what Buddy would say.

“You know what?” Juno snapped his fingers like he’d just had a fantastic idea, “You’re just the kid I need for this very important case!”

“I am!” Bianca beamed, not a question. She had perfect confidence in her own abilities.

“It’s a classic head scratcher, kiddo,” Juno announced grandly, mostly to stall for time while he decided just what this case was going to be, “I’ve been at it for years and I’ve never been able to crack it but with your pluckiness and my brains we might just solve the case of...uh...the case of daddy’s missing glasses!”

Bee Bee gasped appreciatively, “Daddy’s always losing his glasses!”

“He is,” Juno snorted, “And we’ve got to go help him, right?”

“Right!” she jumped onto her feet, bouncing up onto the couch cushions and promptly tumbling, Juno just about managing to catch her. It didn’t seem to diminish her enthusiasm, as her legs windmilled wildly, “Let’s go!”

“Okay,” Juno grinned, “Well, first thing is to examine the scene of the crime and…”

“No, mama!” Bee Bee frowned, looking at him like he was profoundly stupid, “First thing is to dress up.”

“Of course. My mistake.”

Apparently no detective work could be done until Bianca was wearing her mama’s old coat, the one he’d hung onto for sentimental reasons even after he’’d been unable to really call himself a detective. And long after the leather had worn on the elbows and there were none of the original buttons left on it.

It needed to be rolled up quite a few times to even get the tips of her fingers poking out of the sleeves and the bottom of it looked like a mad kind of wedding train but Bee Bee grinned in delight and it was pretty good to see the old thing getting some use again.

“Now we go to the scene of the crime,” she declared, waving her arms, “Daddy and mama’s room!”

“Come on then, co-detective,” Juno laughed, “Lead the way.”

If Nureyev was surprised to see them burst through the door, it didn’t show on his face. He didn’t scare easily. He only smiled and tilted his head, quickly shoving the book on pregnancy he’d been reading far under Juno’s pillow. They weren’t quite ready to broach that subject with Bianca yet.

“Hello, my loves,” he hummed, “What adventures are we on today?”

“We’re playing detective!” Bee Bee toddled up, clambering on the bed to give him a quick hug before anything else, “Going to find your glasses.”

“Oh could you!” Nureyev smiles pleasantly, “It does seem I’ve misplaced them again, reading is something of a chore without them.”

Juno arched an eyebrow at his husband, “You wouldn’t possibly be deliberately reading that book without your glasses so you could claim you have while not retaining any information or looking at any of the diagrams?”

“An outlandish notion,” Nureyev flicked his fingers at him airily, turning his attention to Bianca who was now crawling around the bed, bent over so she could scrutinise every inch of the sheets like a bloodhound with a scent, “Please, dear little detective, will you take my case?”

“We on the case, daddy!” Bee Bee assured him, hurrying over to give him a hug, now just because she wanted to, “We’ll find the glasses.”

“You gotta question the witness,” Juno advised, “Build a timeline.”

Bee Bee nodded, looking up at Nureyev with a sudden fierce seriousness, “What is your timeline, daddy?”

He couldn’t help but smile down at her as he pretended to think, “Let’s see...well, I went to the kitchen for breakfast...then I had to collect some floorplans from Buddy’s office, I read them over in the family room with my wife...then I had an appointment with the physician. Then I came here to have a nap and do my assigned reading.”

Juno rolled his eyes at that last one.

“We’ll track 'em down!” Bee Bee declared, barrelling off the bed onto the ground. Again, her mama only just managed to catch her, “Come on, Detective Mama! Before the trail goes cold!”

Juno chuckled, pausing briefly to lean down and kiss Nureyev, before he followed his daughter, not needing to hurry too much, one of his strides matching about five of hers.

Their trail through the ship took them most of the rest of the afternoon, clattering through the winding corridors, the two of them making up wild twists and turns whenever suited them, inventing new characters, dastardly schemes that had happened off screen, speculating wildly on new threats. Buddy of course joined in enthusiastically, she was a regular and beloved playmate of Bianca’s. Just searching her room turned into a frantic search to disarm a bomb left by this mysterious glasses thief, a bomb that turned out to be in Buddy’s chest which could only be fixed by a hug from a plucky little detective.

Vespa was less willing, they caught her in the middle of disinfecting all of her scalpels. But even she wasn’t immune to Bee Bee’s charms, eventually playing her role with grudging grace. And Juno was able to get a quick whispered update on Nureyev’s check up, feeling a little better that it wasn’t just him and his husband who knew, that he had someone to offload all his anxiety on, the same anxiety he was trying to shield said husband from.

Even better, they ran into Rita in the kitchen and the game then swerved happily into the wildest corners of two vast imaginations, going off on a tangent that somehow involved werewolves, a falling moon and a galaxy wide ring of prolific glasses thieves (it turned out Rita had lost her pair too, though they did turn out to be perched on top of her head).

It was when Bee Bee was rolling happily around on the floor that she suddenly froze and squealed in triumph. She bounded up to the side table next to the old, sagging sofa, less than an inch from where Juno had been sitting earlier.

“Here! Here’s the glasses!”

Sure enough, there was a pair of cat eye spectacles on a silver chain resting there. Even Juno couldn’t raise much of a grump when he realised they’d been inches from their goal at the very start of the job. Some cases just worked out that way.

“We’ll have to take them back to your daddy, huh?” he panted, collapsing next to his daughter on the sofa. Somewhere along the way he’d picked up glitter on his black turtleneck, a rubber glove from the infirmary stretched over his head like a mad hat and one of Buddy’s scarves wound around his neck.

“Yes! And then get paid,” Bee Bee nodded, making Juno slightly nervous about what sort of payment she was going to demand. She’d asked to be paid in ice cream last time they’d played this game.

She plopped down next to her mama, leaning against his arm, adding more glitter to his favourite jumper, “Mama? I don’t think daddy is very happy right now. I think something’s up.”

Juno froze, “Uh...what makes you say that, kiddo?”

“Well…” Bee Bee wrinkled her nose, “He just seems...floppy. Always flopping on you and he looks pale and he doesn’t sleep good, mama. I think he’s sick.”

Juno tried to keep his face carefully neutral, “Your daddy’s fine, honey, I promise.”

“Hmm,” she replied, in that way she had that let him know she didn’t believe him in the slightest, “But it’s okay. Because we found his glasses and that’s gonna make him happy. And then we’ll help him more and we’ll do detective and find his happy.”

Juno relaxed, wrapping his arm around her, “Oh yeah?”

Bee Bee beamed and nodded, “Cos I’m the best detective ever! And mama helps!”

Juno sat back, laughing mostly to himself.

“You know what, kiddo? I thought I was pretty good but I think you really might be the best ever.”

#the penumbra podcast#juno steel#peter nureyev#jupeter#fluff#please reblog and comment if you like this!#tw: trans pregnancy

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

You're probably getting tired of doing kidswap analysis, but I just really wanna know how you think these ones would work: Rose Strider (swapped with Dirk), Dave Lalonde (swappes with Roxy), Jade Crocker, and John English?

So Rose Strider, growing up entirely alone in a very enclosed space, observing her Bro (for the sake of my sanity, we’re gonna say it’s Dirk who grew up kinda weird but generally okay) from a distance of many years. Extended isolation probably means touch is something she simultaneously craves but has NO IDEA what to do with. She observes her friends and reads over her own conversations with them a million times, overanalyzing everything partly because she’s very smart, and partly because she has nothing else to do, and partly because she has no idea how regular human beings interact because she isn’t one. Goes out swimming a lot, isn’t really mechanically minded so she doesn’t end up with Dirk’s hoverboard or anything but she’d actually probably end up a REALLY good sailor. Knows the winds, knows the waves, goes out sailing and fishing and pretends she’s a protagonist in one of Ernest Hemmingway’s novels, like The Old Man and the Sea or something. Probably hates the taste of orange soda and orange Gatorade. Thinks it’s her Bro trying to pull some kind of game with her. He was a weird dude. There’s definitely meaning here. Is the Gatorade a passive aggressive reminder to stay hydrated? Is all the soda meant to remind her that salt water is undrinkable and she must consume this processed, sugary, water-shit in order to survive? Oh, he got her good. At the same time, she probably looks up to him a lot, even if she would rather pry her own teeth out than admit it. She’s really good at sewing and knitting, and has a bunch of plush replicas of his famous smuppet empire. She sleeps holding onto an orange one she crocheted. She’s stuck isolated with only her waterproof computer and a couple robots her Bro left behind as “caretakers,” but they don’t really have any soul in them, not that she can see. So she rabidly learns everything she can. She reads wikipedia for fun, has a million tabs open at all times, learning has never lost its magic and sometimes she wonders if that’s really all she can even do. Definitely has attachment issues, where sometimes she’s cold and callous and goes long spans of time when her friends don’t see hide nor hair of her, and other times suddenly they can’t get her out of their personal space. No idea how to relate to human beings. Awake on her moon beforehand, she’s communed with the horrorterrors a bit, and has used that to her advantage as a Seer. As Seer of Heart, she knows a lot about her friends! She can see their souls in plain, she knows she’s loved, and she knows they’re all friends, and she is good at picking up on their emotions and moods. But what does she DO with that information????? John is distressed so… pat his back??? Give him chocolate??? When Dave is humored should she laugh??? Is she even in on the joke??? What does Jade need when she’s angry??? Should Rose just listen??? Give words of comfort??? Help her calm down??? Socializing is so HARD! She has all this information but doesn’t know what to DO with it! Her quest, much like Dirk, is to figure out how to be, like, a human being who can relate to others in a productive and empathetic manner.

Dave, raised in isolation, growing up adoring his mom from many years distance, with a cat-cloning machine and a bunch of chess pieces for company. He, at least, understands the basics of the social exchange. The chess dudes aren’t the BRIGHTEST, and they don’t really operate with human social norms, and they’re always hungry, and sometimes they try to eat his cats (Dave is cat dad now, those are his babies), but he likes them, they’re his buddies. Pumpkin potlucks with pumpkins imported directly from John’s island are probably pretty common? Is Dave sick of the taste of pumpkin? Probably. Does he absolutely want to have those potlucks anyway? You bet your ass he does. He’s friends with them, for all they seem to worship him as some sort of god. He probably thinks they’re all really great and adores them in a capacity similar to how he loves the Mayor. Getting to meet his friends face to face is probably something that is simultaneously the best thing in his life, and absolutely terrifying. Holy shit, those are other human beings. Dave doesn’t know how to human. He tries desperately to human, and he tries to model himself after his mom (it doesn’t end up too well), but holy shit he is a novice in the art of humaning Rose. Rose what should he do. Rose. Knight of Void, his job is to protect them from the unforseen and covert. )(IC and the Dersian agents are gonna have a harder time with Dave on the scene, and while he cannot perform Roxy’s role of leading their session, he can damn well keep it safe.

Jade Crocker, raised by Dad Crocker, in a society much like ours but slightly more advanced and as heiress to a baking empire. Probably a culinary scientist of some sort, since her whole life baking and cooking and stuff has been a thing, but she’s still, at her heart, innovative and scientific. Probably knows the nutritional properties of a tomato and lots of weird food history fun facts. An actual goddess with mettle to be meddled with and an optimistic attitude that cannot be kept down. Crockpop of course supports his daughter and is so proud of her, encourages her to pursue all her goals, and watch out for assassination attempts. Good reflexes. Definitely a dog person. The kind of girl who will make those “A cat came into my house, teleported me across town when it was raining, and left me there to call my dad to come pick me up while I stood in an abandoned field for half an hour because he plugged the wrong address into his gps” posts. Nobody really takes them seriously but since she lives with GCat meddling in her life they’re actually true. That damn cat has caused her TOO MANY PROBLEMS. If you have a cat she wants NOTHING TO DO WITH YOU. Probably unironically reblogged that post about the “I’m a lesbian and I hate cats” article and insists that dogs are the only way to go. Does own a rifle in this verse, but Crockpop is VERY meticulous about gun safety and proper usage and handling and some of their father-daughter bonding time is the two of them out on the shooting range together. She’s a real sharp shot. Witch of Life, she’s a powerful healer and can revive folk, but more than that, she can FUCKING TAKE YOURS FROM YOU IF YOU CROSS HER. Like Feferi, her powers are pretty vast in what she’s capable of doing, and she doesn’t have a lot of restraints on them, so the last place you wanna be is on her bad side. She can give you life and she can take it away, bitch. Also… so this is entirely inspired by that one Overwatch character, but please imagine Jade alchemizing a rifle where the bullets are her Life magic and she just. Shoots you better. My badass daughter oh my god I love her so much.

John English would likely end up a lot like John Harley, just without the nifty chess people or magic dog and with some cool monsters plus the death of his grandma. Depression sets in early, socializing is hard, getting out of bed is hard, feeling excited or adventurous is fucking hard, even though he wants to. He wants to feel happy and good and excited, he craves that, but it’s hard. He wants to be goofy and have fun but it’s all so exhausting but talking to his friends usually makes that aching tiredness inside him alleviate for a little while. He’s not suited to isolation. As Heir of Hope, he would start out thinking that the Game got his classpect wrong. He’s not hopeful. He doesn’t embody anything remotely approximating hopefulness. But the point of the Game is that he must become hopeful, he must unfurl his wings and take to brighter skies, brighter times, build his relationships now that he can see his friends, love them fully with his whole heart, not at a distance but present and real. His story would not be the story of a plucky go-getter adventurer, but as a broken boy learning how to Hope for the first time. It is a story of overcoming, of victory, and of the desperate pursuit of forward motion, of learning how to look forward to the future and see good things in it, of finding happiness and goodness in a life of possibilities, even when faced with adversaries.

#Rose Lalonde#John Egbert#Dave Strider#Jade Harley#Rose Strider#Dave Lalonde#Jade Crocker#John English#answers#homestuck meta#analysis#homestuck#John#Dave#Jade#kidswap#I'm not tired of these at all!#It just takes me a little while to get around to them sometimes#I have a bunch of other stuff I should be doing otl#but they're so fun I just wanna sit here and talk about these kids all day

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

I hear you on Potter being deceptively hard to world-build and an eventual failure in the making. Seeing the franchise name become "Wizarding World" is a bad sign but WB seems to forget Potter was a story with a clear ending, so it CAN'T go on eternally like Star Wars or superhero-verses. I'm already feeling bad on how new Potter media reflects on the main seven books. Anything else to add onto Potter & franchise-building in general: how hard it is and the roadblocks corporations face doing so?

I’ll admit, I definitely dropped that in there on purpose, because the idea of How To Make A Shared Universe is one that was preoccupying me a bit recently, and why Harry Potter it turns out can’t do that at all. Even setting aside how good or bad it might have been, Cursed Child is clearly redundant: there was one villain that all other evil flowed from in a very direct sense, his defeat closed the narrative for the main character, that’s the end, no other stories cry out to be told in this world. Yes, you can make a quintilogy about the guy who wrote one of that main characters’ textbooks, but it’s beyond pointless.

At the same time, Harry Potter seems like it should be conducive to the shared universe approach: there’s so much mythology and history setting up the scaffolding of that world, it feels as if you could explore its corners forever. But all of it, from the spells to the characters to the locations, ultimately come down to how they impact Harry. That’s not a flaw of the work, and those characters do breathe on their own, but it’s not *really* an ensemble piece. Only the one guy’s got his name on the cover (well, Sirius and Snape had their nicknames on covers, but you know). Everything relevant feeds back to him and his development one way or another, and once his story is done, the world ends with him. It’s rich set dressing, but for a purpose that has been served.

Star Wars on the other hand, as the star of the day (or at least the day I received this ask) and therefore my primary positive example? Just going by that first movie, while there’s one character in particular whose narrative ends up driving everything, one of the first things we learn about Star Wars is that a lot of people’s very different stories are propelling this world forward, from comedic robot duos to gun-slinging space smugglers to princesses overseeing galaxy-spanning conflicts to wizard samurai to plucky teens in search of adventure. They’re all relevant, and because of that we as the audience are to understand that all the corners of that world they represent are themselves relevant.

Thinking about it, I ended up laying out some rules for how these mass universes (on the Star Wars/DC/Marvel scale) tend to work:

1. They can’t be set in what we’d comfortably call the real world. If it is, there’s no real shared conceits, beyond the ones us real schmucks already live by, and aside from that the characters could run into each other, the connection is immaterial. The Middle and The Office might exist in the same universe, but besides a theoretical crossover episode, what opportunities spring from that connection that justify making it in the first place, that’d make people go “wow, they exist in the same world, this changes everything about how they both work”? If two or more fantastical things coexist though, you’re multiplying the number of things you’re permitted to bring into each other’s narrative spaces, meaning crossovers can thereby make both worlds exponentially richer.

1a. Speaking of conceits, generally speaking there does need to be a shared one or two that’s specific beyond the very concept of “magic/time travel/etc. exists,” to show why all this stuff needs to be in the same world.

2. Closely tied with the above, there needs to be the opportunity to explore multiple genres in that world; if you want this place to feel rich, it has to be able to feel like all kinds of stuff is going on in there.

3. Closely related, the idea that there are multiple figures of significance worth following beyond their involvement in one or two other peoples’ stories in this world is crucial.

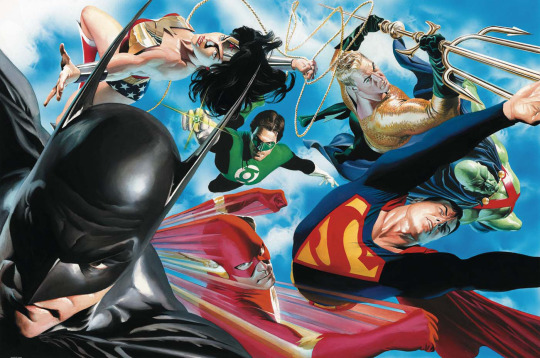

I talked about Star Wars and how it invites diverse genre possibilities a bit already, so let’s go with my own favorite shared universe in the DCU. While I tend to think it actually works best when the ties that bind them are fairly loose, let’s cover what the core Justice League alone bring in:

* With Superman and J’onn, it’s clear that aliens exist in this universe, that they may have fantastic abilities by our pitiful human standards (or may gain them under special circumstances), that both literal little green men from Mars beyond our ken and incredible Flash Gordon-style pulp sci-fi civilizations of near-humans number among them, faster-than-light-travel and teleportation are on the table to get them here, at least one brings an entire ghost dimension with him, and they may well wear elaborate uniforms and publicly devote their lives to protecting Earth, while also living among us as humans in “secret identities”. Their adventures in pursuit of this duty can take them from the depths of space to the inside of men’s minds.

* Batman shows that humans can also devote themselves to the same mission with the same basic methods of operation, that these weird costumed characters can fight flashy stylized murderers with elaborately themed Rube Goldberg-esque master plans, and that said human vigilante can in fact function and defeat them with access to a perfect physique, virtually every existing human skillet, a set of gadgets and vehicles that wouldn’t be out of place in James Bond, and a network of allies, i.e. superheroing is an option theoretically on the table for anyone and everyone in the right circumstances, and they can get so good at it as to earn a spot on the big table with people with superhuman powers.

* Wonder Woman and Aquaman demonstrate that magic, hidden civilizations that may emerge to impact humanity at any time, and literal gods are also on the table - and those of such realms may take classical heroic journeys to save our own world.

* Flash shows that just any old normal human can get powers like these under the right (if still improbable) circumstances, as well as bringing in time-travel and expeditions to other universes.

* Green Lantern shows that all these incredible forces can and will take notice of humanity directly, and declares that even our literal emotions can have a tangible, cosmos-shattering impact when the right super sci-fi tools are applied, and that we may take part in a universe-spanning mythology that extends from galactic military campaigns to beat cop work.

Even if you deleted the rest of DC Comics tomorrow, you could easily rebuild a world from those seven characters and the first principles they represent. There’s a ton going on. And at the same time it makes sense that they can and should all sit in a room together, because they share similar aesthetics and basic goals; that they’re the founders of their own genre all coexisting together in one world is itself a solid, unique central hook to justify building a universe around them.

I think those rules hold up pretty well. Take Kingdom Hearts: much as I love it, it isn’t well-suited to an expanded universe setup. While there’s a lot of crazy magic and super-science and alien races and mythology in there, it all only really comes down to the people with the keyblades, and they just go from world to world to beat a given bad guy or seal a keyhole; there’s only so much you can obviously justify doing if you stray away from that core premise. Star Trek on the other hand for instance, while centering around a singular organization, has such a broad mission statement - go Out There to find new life and new civilizations - in the context of multiple ensemble piece programs that you can do just about anything with those crews, from dealing with metaphors of race relations to getting thrown into the 1930s to meeting actual Greek gods, and as such a whole empire of TV shows and movies and novels and comics and audiobook dramas and whatnot makes total sense. That’s what it comes down to: if there’s a real feeling that this is a world that can plausibly have anything, then there’s no reason not to do do everything with that set-up.

In a corporate sense like you ask the basic principles don’t change, just the budgets depending on the medium and which characters you can wrangle if it’s an adaptation. I do admire though how the MCU and the DC TV shows have made it work in the public consciousness, particularly how they sidestepped the possible uncanny valley involved with the concept by slowly building up to their weirder elements. The MCU kicked off with a normal guy in an - admittedly extraordinary - exosuit he built fighting terrorists and other guys in exosuits, the next had a monster but one of science gone wrong in building a super-soldier, the next had a god but in another dimension, with most of his time spent on Earth being mortal, and the straight-up costumed superhero of the bunch was in a pulpy period setting, with only Avengers finally doing a straight-up superhero action movie where they all get together with some super-spies to fight aliens. The CW’s world started off with a single crimefighter without even Batman’s allowances for a strict moral code and a flamboyant theme, slowly introduced super-drugs, eventually allowed super-beings but in a limited context with a single well-defined source point, then time travel, and then magic, and then aliens but in another universe, and then finally they let it all sit together with all of these becoming normal elements regularly crossing over and teaming up with superheroes as an established part of that world. Not that it necessarily has to be that way - I have problems with the DCEU, but it isn’t that it kicked off with Superman and then immediately brought in the rest of the Justice League, even if the insistence on pseudo-realism seems odd in that context - but especially in the early stages of making this something that can work for the first time on TV (aside from Trek, but those didn’t often cross over on TV and didn’t branch out nearly as much) and in movies, I bet it helped.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kaori “Xenon” Yaguri: Desert

“Hello. This is Kaori Yaguri, on board the survivor-shuttle ‘Xenon 001’ I have no engine power, and the host ship was destroyed in a collision. Half of my shuttle is inaccessible due to vacuum. Mayday, Mayday.” The short band star-wave® radio hissed back at me. Just like it always did. The ambient garbage waves of the stars caused it to lap and sway like the shores of California. “In other news, it’s my 24th birthday - and Xenon’s third. Xenon had a growing pain today, the circuitry on my surveyor panel fused during a solar flare. I was able to sheild my self in the main cabin using the old space suit. Its going to be out of air soon, i’m down to my last six canisters. Seven had a leak, turns out.”

This was the best way to maintain my sanity - and to keep the radio waves alive with my signal. If a ship would get close enough, they’d receive my emergency shortwave broadcast. An alert would pop up on their sensors and they could tune in if they wanted to. ... You’re supposed to do it any way, but distress beacons are so good these days that is not usually a problem.

“I was able to scavenge some wires and other stuff out of the main cabin. and performed our weekly check on the food preserve. We fixed the surveyor’s panel, and i was able to apply rotation to the ship using a piece of tape and slice of ham -- had to make the screen think i was holding the dish-alignment button down for three days. This rotation will keep Xenon from losing power to her own shadow over solar arrays. The colony of spiders i had with me have died, the last one starved - i could no longer support it, and the gnat farm had a crack in it after i knocked it over, so they are all eaten. ”

Every morning i wake up, turn on the shortband, talk to .. no one. then leave the short band on for as long as i have the power to do so, letting the galaxy listen in on my private conversations. I once watched a ship sail right past us because i didn’t have the short band on long enough for them to find me. I didn’t even know they were there till the sun shined on their aft. “I’ve finished programming my first game, Shattered Ship, the art looks a little stupid but for a two dimensional game, its pretty fun. I’ve had a lot of time to work on the random event generator, and the crew finally stopped killing each-other every time there is a torpedo fire. I’ve moved on to finish working on that adventure game i started last year, about the desert planet. I dunno, seems ambitious. We’ll see.”

Xenon is all I have left now, she is my sister and she is sick. Her power coils won’t last another two years, they’re 2 years past warranty. Her antennae is gone, broke up in a low-orbit pass through mar’s atmosphere. We’re scheduled to pass by again this year, If we’re too low -- Well i’ll probably die unless Xenon’s parachutes still work. If we’re too high, I’ll be flung into solar orbit with the euro care systems, where I’m most likely to be found in another year. ”All things considered, Xenon is really quite happy today. Her batteries are pretty much full, the solar array is only down to 80% maximum efficiency which is great, considering how hard it is to sleep with the blast-panels open at night. means I won’t get locked inside the crew quarters again this week. But out heat waste is minimal and we’ve got plenty of spare parts now that i got the door controls to the cabin working again.” If the mars colonists have their defense radar pointing at me when i pass through, they’ll know its a rogue shuttle, might even notice the distress signature... But i’m from earth so they’ll probably just let me drift another three years till i show up again.

“I read the manual, last night, the service manual - Xeonon’s diary. She says these emergency signals are saved on a data storage somewhere in the ship, as part of the black box. I don’t know how much storage there is, or how much these take up - but the idea that some pooor soul is going to listen to me drone on for three years is terrifying. If there is enough of this material to turn into a book, and then sell it - leave some money for my daughter, if i die. In about six more hours I’ll pass by Kathy-sixsix again, the signal buoy, marking our third year in this eccentric orbit. I’ll be leaving another message for Kathy, the radio operator for this area - maybe she’ll get it, i don’t know. It took forever to build the second net, I don’t know what I’ll do if I miss again..” I stayed up all night two days ago to make sure i would be awake to see Kathy-Sixsix on the surveyor radar - it gives me a better idea of when I’ll have to get out into the space walk with the net. Kathy-SixSix is part of a network of surveyor buoys, with radio dishes set to record, and analyze radio data from other solar systems. It still picks up 16 year old news from the Proxima Colonists. Surely my short band.. and.. annual vandalism are enough to get some ones attention? “Kathy-SixSix this is Kaiori Yaguri, on board the survivor-shuttle ‘Xenon-001′. We’re on course to attempt another netting of your buoy. I have the net’s anchor welded with the backbone of the ship now. One of use is going to be very unhappy in a few hours. I’ve already prepared a Message in a Bottle for you to collect assuming the magnets do- But then, the Buoy responded. “Shuttle Xenon, this is buoy six six. If you’re hearing this, the buoy has detected your radio signature and is responding automatically. This message is two hours long, you need to hail the buoy. Any way you can, I’m not allowed to be on a shift longer than twenty four hours. I’ll have my friend listen for you, If i’m not here. ” It was a very plucky, childishly feminine voice. Reminded me of a flight cadet freshman. I was so happy to hear another voice, another person. It wasn’t on a song, or a radio-advertisment. It was a one-way-broadband audio superhighway into my heart. She knew my shuttle by name!

“The surveyor’s guild is ready to pardon all damages to the buoy, and we have located your daughter, Artemis. Acting Captain Yaguri, we have secured several hooks to the outer-hull of the buoy on break away welds. There will also be a local unpaid intern assigned to Kathy-sixsix every fourth hour for two hours. If you agree to the terms of a contract, the surveyor’s guild would like to do a series of interviews on your journey....” The message was official, and long. But i could hear her, Kathy, the buoy operator. I had listened to my own voice for so long, and Xenon wasn’t equipped to talk. Kathy sounded gorgeous, and also a little sad. “Kaori, this is Kathy. We’ve been picking up your radio logs for the last three years, and I’m sorry. For everything. It is my job to listen for voices like yours. Once we had your signal code on record I was able to keep track of your transmissions. I’ve been listening to your stories about your friend.. I’m at the part where she died. I guess now i know how the story ends, but. I’m so sorry. I .. wasn’t listening to the emergency signals, never even checked them. No one ever flies out here without an escort, there is too much debris. Your ship’s fabricators are already willing to make a settlement with you, since your engines failed. And.. I’ve been letting your daughter listen to every signal we decode. You’re quite the hero back on earth, it turns out. No ones been able to find you, even the teams on mars let us know if they see any thing weird on radar. The fabricators even put out a finder’s fee, like you’re a lost dog or something. Shuttle Xenon, this is buoy six six. If you’re hearing this, the buoy has detected your radio signature and is responding automatically. this message is two hours long, you need to hail the buoy. Any way you can, I’m not allowed to be on a shift longer than twenty four hours. I’ll have my friend listen for you, If i’m not here.” “Kathy-Sixsix, this is Kaiori aboard the survivor shuttle ‘Xenon’. I have your message loud and clear, I’m six hours from the mark, and I have no ships on my radar. Please, someone respond. If i have to agree to some fucking contract, I agree, sign me up, what ever just

GET ME HOME.

Then i waited.

“Shuttle Xenon, this is bouy six six. If you’re hearing this, the bouy has detected your radio signature and is responding automatically. this message is two hours long, you need to hail the bouy. Any way you can, I’m not allowed to be on a shift longer than twenty four hours. I’ll have my friend listen for you, If i’m not here. Your daughter has been doing better in school, the Surveyor’s Guild has put her in a junior academy. Her father had to ask the reporters to stop harassing her so much. He was accused of profiting off your situation a few months ago, and some one dedicated a song to you at the music awards. It.. was a cover of Major Tom.. I’m sorry. No one asked for this. The new flight marshal was instated a few days ago, and wants to put no fly zone for rookie pilots in the debris cloud , to ensure no one ever has to be stuck out there ever again. You have to have a B level rating or higher to fly non-commercial. I don’t know if that’ll help. Seems weird to put a no-fly-zone somewhere where people are more likely to be stranded or worse. Don’t smugglers hide in NFZ?”

I watched the radar until it was nearly time to do the space walk. two hours until mark, and i had to get ready to deploy the net. But first i wanted to hail the buoy. The radar was still empty.

“Kathy-SixSix, Xenon here, when the Guild assigned Unpaid Interns to watch for my passing, did they check the pilot’s flight rating?

Am I currently in a no fly zone?

I have to get ready soon. I’ve got a better net and a better anchor this time. I’ll be able to tow, or destroy the buoy. In either case, something will happen and I’ll have more scrap material to build an antennae out of. Or the spine of the shuttle will collapse and I’ll be dead, or clinging to the buoy. I’ve got a tool-bag i can fit all the spare air canisters in.... jesus christ please respond. Kathy, please. Give me a better option.”

I waited, tears in my eyes as I stared into the bandwidth monitors, waiting for the static signals to change. This was all I had left.

“Shuttle Xenon, this is buoy six six. If you’re hearing this, the buoy has detected your radio signature and is responding automatically. this message is two hours long, you need to hail the buoy. Any way you can, I’m not allowed to be on a shift longer than twenty four hours. I’ll have my friend listen for you, If i’m not here. It seems like people, rookie pilots mostly, have taken to scratching their name and their rating in Buoy sixsix’s paint using their repair tools. There were six or seven names when the trend started, I counted seventy last time i went out to repair it. Maybe one of these enthusiasts will come out and try to add their name to the buoy. One way to survive would be to anchor onto the buoy some how. Your relative speed is quite high, so you’d need to slow down. I’ve added some commercial air tanks to the repair storage on the buoy. the keys are magnetized to the underside of the buoy's new collision-safety lantern, opposite of the ion drive. I’ve been talking to your daughter about things that might help keep you company. I had to go, it was time. I needed an antennae, and the buoy had several just flying about last time i left. I managed to knock several loose. Maybe they magnetized to the buoy or stabilized near the buoy in some kind of Dzhanibekov spin. I’m probably not lucky enough for that. Out here on the magnetic surfaces, watching the buoy slowly get closer to me and Xenon, i could not see anything other than the buoy. No ships, no debris. Just a floating hunk of spare parts. I had 30 minutes to set out the net, one hour to stabilize it and another thirty to get safely inside the ship before i created another debris cloud. There wasn’t any A-ARCS left in my suit, i burned that a long time ago just trying to slow the shuttle down, so i couldn’t jump ship and transfer to the buoy itself. Once the net was ready to catch the buoy, I was on my way back inside. I drifted through the rear cabin’s hull breach, used the fixtures to navigate inside and was lucky enough to have an emergency airlock between every major substation on the shuttle. Just slip out of the suit, disconnect the canisters and then strap my self into the surveyor’s console. “Shuttle Xenon, this is buoy six six. If you’re hearing this, the buoy has detected your radio signature and is responding automatically. this message is two hours long, you need to hail the buoy. Any way you can, I’m not allowed to be on a shift longer than twenty four hours. My co-workers no long wish to take additional shifts to fill that time. It was really hard to get people on board with your net idea. No one wanted to rebuild a buoy, but now that you’re such a celebrity, the cost of our public image seemed rather high. There are these videos on the web, about how to get you safe. It started with a simple mag-tow and RCS burn.. the whole thing devolved into more complicated plans over time. You could, for example, tie together sixteen thousand socks, and create an elastic brake that you lasso around one of the hooks we welded onto the buoy. The buoy would tear the socks and you’d slow down just enough to.. well, collide with mars but we’d know where you were going. Oh that reminds me, don’t dissemble the parachute systems for any reason. A lot of junior academy simulations are showing how easily you could enter mars atmosphere this coming year, and you’ll want those to be operational. You’ll have to set them manually to deploy when there is enough atmosphere for them to grab onto, though. The maintenance guide on board with you should provide the information on how to do that. I’ve gotta go to bed, when i record the next message I’ll read you a chapter from a book your daughter said you like. Be sure to stay tuned in for that when ever this gets added to the message loop. Its been six months since I set this message and now i am adding to this loop, it can only fit 2 hours of data..editing it is a nightmare though. sucks, right?”

#kaori#xenon#yaguri#space#scifi#damage#ship#captain's log#space travel#stranded#diary#isolation#RP#OC#Original Character#Blog#roleplay#mars#colonized#repeating#themes#askme#answer this#answerme#answer#drifting#story

9 notes

·

View notes