#so I don’t think it is remotely radical to explore how a female character might present outside of that paradigm

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

why is it ok to draw gnc female characters in pretty flowing dresses and lace etc but the second you style them as masc you get randos screaming ‘X IS FEMININE A LADY A GIRLY GIRL LET X BE FEMININE THIS IS SO SICK’ like ok but where is this energy for the flower crowns

#this is so egregious when we’re literally talking about gnc characters half the time#and also lbr Westeros is a setting that generally requires a high level of gender conformity#so I don’t think it is remotely radical to explore how a female character might present outside of that paradigm

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

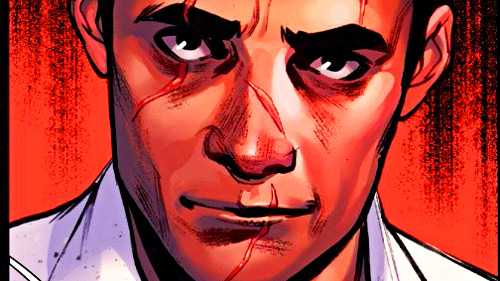

Spider-Men II (2017) - Or, the comic book that shouldn’t exist

Spider-Men II is a meandering, unfocused mess of lukewarm ideas with no pay-off, that dabbles in colorism and whitewashing.

Somewhere around the “Venom Wars” and the “Spider-Man no More” arc, there was a sharp decline in the quality of writing for Ultimate Comics Spider-Man. At the crux of it was the death of Miles Morales’ mother – Rio Morales – and the emotional bullying of a kid who wanted nothing to do with superheroing following the death of his mother, but was battered into thinking otherwise by the female clone of Peter Parker (Jessica Drew), Gwen Stacy, and his friend, Ganke Lee.

If “Venom Wars” was the signal that things were going south in the writing department, the death kneel for Miles Morales’ storyline truly began with the story arc “Spider-Man No More”, which was lead directly into a discombobulated series of story arcs that preluded and finalized the death of the Ultimate Universe.

Since then, Bendis’ take on the character – who had a fairly solid start (from Issues #1-19 of UCSM) – declined in a way that I can only describe as a writer simply losing interest in their pet project and disregarding how he handled the character from thereon out. There was no emotional investment in Miles’ day-to-day life, his family unit, friends, and etc. like there was for Ultimate Peter Parker. Ultimate Spider-Man was, as far as Marvel comic title goes, was fully realized story. But, if we’re being honest, Bendis also didn’t have to do a lot of thinking for Peter’s stories because they were often retreads of plots written fifty-sixty years before his time at Marvel.

With Miles Morales, Bendis, was, to some degree, flying blind and more or less had an open field of possibly and stories to play out. He could’ve created a legit mythology for Miles. Yet, when you boil it down, if Miles wasn’t being thrown into a “Blockbuster Event” meant to boost title sales then he was often standing in the shadow of some version of Peter Parker or Peter Parker’s family members in his own title. Simply put: Miles could not be Spider-Man in the same way Denzel Washington’s The Equalizer couldn’t Jason Bourne the hell out of bad guys without the say so of a white authority. Every time Miles’ story circles back to Peter Parker, the limitations of Bendis’ imagination with his Black Male Superhero was clear.

I don’t think anything encapsulates this more than the unwarranted sequel to Ultimate Marvel’s 2012 miniseries, Spider-Men: Spider-Men II – released in 2017 with about the same amount of issues to its name (five).

Spider-Men saw a then-brand new Spider-Man, a thirteen year old Miles Morales – encounter the 616 Universe version of Peter Parker, who accidentally ends up the 1610 Universe after some convenient circumstances involving the 616 version of Mysterio and a dimension hopping device.

Similar to Ultimate Comics Spider-Man #1-5 and Ultimate Comics Spider-Man #13-14, and Miles Morales: The Ultimate Spider-Man #1-7, Spider-Men #1-5 runs Miles through the third consecutive gambit of getting “The Blessing™” of someone connected to Peter Parker, or Peter Parker himself. Spider-Men is more or less about how an adult Peter Parker deals with the fact someone much younger than himself (when he started doing what he was doing) was playing the role of Spider-Man following the death of teenaged version of himself (1610 Peter Parker), and eventually accepting that. It was a fun crossover that saw Miles work alongside someone he admired, and most importantly, didn’t lose sight of its tone and who the story was about in the end (Miles).

Spider-Men II, unfortunately, does the exact same thing, but now there’s no Brand New Car Smell, the question of how Peter Parker would react to a kiddy Spider-Man has been answered and Miles has been friggin blessed, officially, four friggin times, by Peter Parker and his unit in every way you can think of.

Whitewashing your Protagonist is a Bad Idea™

The crux of Spider-Men II is to answer the question that Miles Morales asked: “I wonder if there’s a me in your universe?” The original Spider-Men ended with 616 Peter Parker searching – online – for the existence of a Miles Morales in his universe and being “shocked” by the answer. Knowing in advance that the series was only five issues long meant that the answer Bendis would provide – almost five years after the original Spider-Men – would be both underwhelming and rushed with no satisfactory resolution to rest on.

The bread-and-butter of a comic book character is their ability to become relatively different characters or offshoots from the one that was the origin point. Marvel’s brand revolves around allowing writers to reinterpret established characters into someone radically different, or just update them for younger audiences. Sometimes this works for good, other times for bad. Anna Paquin’s Rogue isn’t 616 Rogue, 1610 Rogue isn’t X-Men Evolution’s Rogue, and so on and so forth.

Where the reinterpretation of a character becomes an issue is when it begins to erase a marginalized identity. It would be common sense among anyone with enough sensitively and the ability to look beyond themselves to know: You don’t reinterpret a Black character – like Virgil Hawkins or Ororo Munroe – into a white or non-Black character, you don’t reinterpret an LGBT character – like Renee Montoya or John Constantine – into a Heterosexual character, you don’t reinterpret a female character into a male character. White or male or female characters? Most of the time their fair game – with reservation (Heathers is a perfect example) – there’s usually nothing remarkable or unique about those characters because they’re representative of the norm, the thing people have been socialized to sympathize and empathize with.

Unfortunately, Brian Michael Bendis and Sara Pichelli are white, so they have neither sensitivity nor the ability to look beyond themselves. Spider-Men II confirms that, yes, there is a 616 Miles Morales. But, he’s a criminal who makes friends with Wilson Fisk (the Kingpin), and is so light-skinned there is no resemblance to his Black counterpart. He’s just the ambiguously brown stereotype. To brazenly imply that Miles Morales was, as a lot of folk were saying when the title was being published, “Sammy Sosa’ed”, is to imply that the story was tackling the subject of learned self-hatred, self-harm, and anti-Blackness and that somehow figured into 616 Miles’ narrative. Instead, this just atypical comic book racism played straight.

There’s little reason to even sympathize with 616 Miles Morales, and the point of sympathy is merely watching him cry over a woman named Barbra Rodriguez, a gallery curator, then use his criminal enterprise, namely the hired hand Taskmaster (which counts like a DC Comics reject tbh) facilitate a means for him to travel to another dimension to be with another Barbra – who presumably hasn’t met that universal equivalent of Miles Morales. For lack of a better word, 616 Miles Morales is probably the version of Miles Morales Bendis would’ve executed if he hadn’t killed Peter Parker (lbr). He’s a terrible character and a particularly woeful answer to a question better left hanging in the air.

There is no “Mary Jane Watson” for Miles Morales

Bendis’ attempts to provide Miles a love life has been – on all accounts – incredibly bad and unsurprisingly limited to white women. Jason Reynolds might be the only writer to tackle Miles Morales to even remotely consider that Miles’ dating pool might be predominantly Black – but, he’s also the only Black writer to tackle the character, so therein lay the problem.

One of the biggest issues with trying to shack Miles up with a girlfriend is that his character has never been allowed to mature. Where Peter Parker (in the 616 universe, anyhow) was allowed to graduate High School and go to College before he started any serious romantic relationships (Gwen Stacy, Mary Jane) or flirtations (Felicia Hardy) and was, therefore an adult where more adult situations could occur, Miles is a teenage boy who’s mind arguably would change like the four winds about girls, but this is never reflected or explored in his title.

Add to the fact that there were no longstanding female characters in his mythology, no one Bendis planned on introducing was going to work. Then there’s the fact that most readers were probably rooting for Miles and Ganke Lee to hook up as opposed to dropping a female character on him – because they liked their dynamic and most were content to compare their relationship to Peter/Mary Jane anyway. But Marvel was gonna pull the trigger on that in the same way neither Miles or Miguel O’Hara will ever get their big media break in something that isn’t a animated film (Into the Spider-Verse), or television series usurped from them (Spider-Man Unlimited).

Early issues of Ultimate Comics Spider-Man (namely issues #12 and #19) preluded the character who would later become Ultimate Kate Bishop – Katie Bishop. Katie Bishop would play a supporting role as a then fourteen year old Miles’ girlfriend – a year after the death of Rio Morales – from issue #23 of UCSM until the end of Miles Morales: The Ultimate Spider-Man (which was only thirteen issues long). But, the persisting issue with Katie Bishop is that – unlike Mary Jane Watson (in almost any iteration of Peter Parker’s story) – she was never given any proper build-up or development as someone who would be important to Miles’ arc before the romancing starts.

She’s just dropped into the middle of his story, and audience is supposed to accept it. Then, Bendis and co. ultimately decide the only way to make this character interesting is make her the daughter of Neo-Nazi and a Neo-Nazi herself who follows the Ultimate version of Hydra. Instead of building any kind of goodwill with the reader, Bendis poisons the well altogether and sabotages the character and this was way before the bullshit he, Nick Spencer, and other writers would pull that would lead to creation of Nazi Captain America (el-oh-fucking-el).

The second attempt to give Miles a love interest was in the misfire series All-New Ultimates, wherein a fourteen year old Miles began flirting with the idea of messing around with, for all intents and purposes, a grown-ass woman named Diamondback – highlighting one of the major issues with why Miles and Romance subplots never work out. Following Miles’ move to the 616 universe, Bendis and whoever was responsible for the Spider-Gwen title tried to establish an Instant Oatmeal romance between a eighteen year old Gwen Stacy and a now fifteen/sixteen year old Miles Morales that was both misguided (Bendis really tried to justify it with the line “I’ll be seventeen in a month!” fuckin’ creep), gross and flat-out boring.

Bendis, has, summarily struck out two times in his lack of effort to create a version of “Mary Jane Watson” for Miles Morales. One was underdeveloped (Kate), the other was outright creepy and his living out the fantasy of fucking Gwen Stacy. Michel Fife’s (the writer of All-New Ultimates) creepy and halfhearted attempt to give Miles a “Black Cat” equivalent unilaterally failed with the end of the title itself. Spider-Men II, unfortunately, is Bendis’ third and final miss in the pursuit of Miles Morales’ love life and it’s a big part of why – outside of the whitewashing – Spider-Man II fails as a story.

Bendis attempts to posit that – for every universe that has a Miles Morales, there is a woman named Barbra Rodriguez that he will ultimately fall in love with. 616 Miles Morales’ entire narrative motivation – which renders 1610 Miles Morales’ side of the story completely irrelevant and void – in Spider-Man II is to escape to another universe where there is a Barbra Rodriguez, because his version of Barbra Rodriguez has died. But in the same universe (616) there’s a younger 616 Barbra Rodriguez that just shows up for no reason for 1610 Miles to swoon over. It’s so groan inducing.

Like Ultimate Kate Bishop, as an idea, Barbra Rodriguez isn’t a bad one per se. The issue is, like Ultimate Kate Bishop, that Barbra Rodriguez is dropped into the lap of the reader and expected be swallowed wholesale. In a series of panels illustrated by a perpetually bored Sara Pichelli (who’s interpretation of Miles has become, honestly, more and more ape-like than anything resembling the stellar character design she and David Marquez started out with, but only Marquez remained faithful to before his departure from Miles’ story) in something that resembles the image of the conceited little girl from Monster House selling Halloween candy to a neighborhood she doesn’t live in, the reading audience is meant to believe Miles falls in love with Barbra.

Barbra Rodriguez is a painfully unwritten and boring character to the point where I don’t think you can call her a character ��� just a prop for a half-baked romance subplot that doesn’t involve the version of Miles Morales readers have picked the book up for. As a character, she brings nothing to the table, as a prop she’s not even interesting. Bendis tries to pull the Star Crossed Lovers Xena-level Soulmates position without ever earning it and as a result Barbra is forgettable. Maybe if he actually introduced her in his last outing for Miles instead of creating a walking stereotype of a grandmother, this might’ve worked better. As it is, Barbra Rodriguez is a last minute thought the story itself fails to capitalize on for anything other than manpain.

Miles Morales isn’t Peter Parker, so naturally, he will never have a Mary Jane Watson. Not even on a metaphorical level, or for the sake of comparison. I honestly think that the only character, if it had to be a woman and not Ganke Lee, that would’ve worked, would probably be Bombshell (Lana Baumgartner). She’s the only female character within his age group he’s actually interacted with and established a genuine relationship.

616 Peter Parker is an Asshole

Peter Parker’s interaction with a then thirteen year old Miles Morales was a fairly fun read. I liked the idea of Peter indirectly promoting himself to temporary mentor because he’s a grown man overly worried about the fact that someone far younger he was superheroing and largely in the memory of even younger version of himself – who he can’t quite deal with being dead (because it’s him). It was cute. The rationale behind Peter’s actions made sense, and it didn’t overstay its welcome.

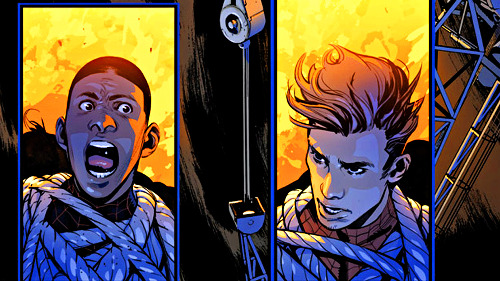

Peter in Spider-Men II is a jerk for almost no reason. Because the narrative begins in medias res, with Miles and Peter arguing about how they got tied upside down, the reader spends a great deal of their time wondering why the hell Peter is being so antagonistic with Miles – to the point where he bluntly tells Miles that his being Spider-Man was a “mistake”.

Spider-Men II does not really answer this question – but instead spends the bulk of its first two issues being evasive about the issue altogether (because issues #3 and #4 are dedicated to 616 Miles Morales and his relationships with Barbra and Kingpin, with issue #5 “wrapping” things up for 616 Miles). Recapping that Peter Parker searched and presumably found Miles Morales in his universe before the implosion of the UM, Spider-Men II then has Peter pretending to help Miles locate the 616 version of himself, going as far enlisting the help of Jessica Jones – who summarily tells them there are no traces of a Miles Morales equivalent to even be worried about.

Because the reader is either meant to believe or knows that Peter is lying or being dishonest with Miles, a lot of their dynamic is artificial. Whatever Bendis managed to capture with the first crossover event between the two characters has vanished altogether. A lot of the time Peter Parker – who I keep forgetting is basically a diet soda version of Tony Stark, right down to wearing an armored suit with a glowing symbol and owning his own billion dollar franchise (Parker Industries) – comes off as condescending and a spandex wearing asshole. An asshole operates on the belief that he has the right and authority to tell a now fifteen year old Miles Morales when and when he can’t be Spider-Man.

Even weirder, instead of shutting that nonsense down, Miles takes it on the chin is more less like, “aww, gee, I guess you’re right, I’ll go be depressed now” even as Peter offers him a half-hearted apology and Miles can only say “well, you said it”. It’s the equivalent of Cyclops telling Storm she can’t be the leader of the X-Men, but without the holy retribution of Cyclops being smote with lightning. Like, I spend a grand bulk of this series – which doesn’t even legitimately resolve or explore the fraught dynamic between the two – wishing Peter Parker would fall into a hole and die. Peter Parker’s character in this title is downright insufferable. I miss John Romita Jr. and that other guy’s Peter Parker, but I hear he died in the Civil War.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

Behind all the mess that is the core of Spider-Men II, there was a fairly interesting idea to explore. Bendis really could’ve focused on how the two Miles Morales dealt with existing in the same space. He could’ve dealt with how Miles was coping with having his mother back, and living in a universe that was not his own – and how the death of the Ultimate Marvel universe affected him.

If he had established Barbra Rodriguez before this miniseries, he could’ve actually dedicated the time barely spent on her to simply furthering the relationship that should’ve started way before this story.

As it stands? 1610 Miles Morales and his exploits are more or less an afterthought to the core of the story itself. Peter Parker is a billionaire asshole throughout most of the plot and honestly not even required to tell the story. You can remove him from any and all plot points involving the “who is 616 Miles Morales?”, Jessica Jones, and the conflicts with Taskmaster, and nothing would change. He is irrelevant.

There’s too much time spent on the whitewashed version of Miles Morales – something that both hinders and illustrates just how far gone Bendis’ writing for Miles has diminished since 2013. 616 Miles Morales wasn’t a bad idea, but the execution of the character is fairly horrendous and racist.

Almost no one talked about Spider-Men II when it was released, almost in the same way there was barely an eye bated when the confusingly branded Spider-Man title (Miles’s 616 outing) was released in 2016 (beyond the “who cares if I’m Black?” bullshit). Everyone was talking about Spider-Men and Ultimate Comics Spider-Man when they were released, a lot of people liked it, some didn’t, but it was rather an indicator of its quality. The almost unilateral silence even Miles Morales fans visited upon Spider-Man and Spider-Men II rather speaks volumes of how bad it got.

I don’t recommend this to anyone who is a Miles Morales fan. You’re better off pretending Spider-Men never got a sequel.

#miles morales#peter parker#brian michael bendis#spider men ii#whitewashing#media: long posts#ultimate miles meta#series: spider men ii#year: 2017#writer: brian michael bendis#creative: sara pichelli#616 miles morales#616 barbra rodriguez#1610 barbra rodriguez#1610 taskmaster#616 peter parker#616 jessica jones

43 notes

·

View notes

Link

IN THE EARLY 1980s, when I was a sophomore at Yale, I lived in a narrow clapboard house off-campus, somewhere east of Wooster Square. It wasn’t the happiest time in my life, but I had a small study with a big metal desk; my roommates were seniors, with one foot out the door; and there was a speakeasy around the corner where you could get a six-pack of beer on Sundays when everything else was closed.

We lived on the top floor; a couple in their 30s lived downstairs: the woman, who was Vietnamese, spoke little English and always looked frightened; her husband, who was white, was a Vietnam vet who would periodically get drunk and beat her. I’m not sure I would have had the courage to do so had I been living there alone, but my roommates often called the cops, who would come and intervene. My neighbors weren’t the first people I knew for whom the war in Vietnam hadn’t ended — I had friends in Pennsylvania whose older brothers had come back, completely changed. My stepfather, a mild-mannered neurosurgeon who had been a doctor in a busy MASH unit, would occasionally belt back a couple of drinks and fly into an inexplicable rage. I was curious about these people, wondered about the experiences that haunted them. But the war, and the protests surrounding it, seemed remote, something I would never comprehend in the way that we can’t really comprehend things we don’t live through, experiences whose most intimate details we will never know.

In Alice Mattison’s new novel, Conscience, we meet two characters for whom the war has not ended either. The novel, which is set in present-day New Haven (where Mattison lives and often sets her stories), is Mattison’s 14th book, her seventh novel in a long, distinguished career as a writer and a teacher. In an author’s note, she explains that the book grew out of her curiosity about an idealistic young woman she met in the ’60s who later “turned violent.” Among other things, the novel poses some interesting questions: How long does the past linger? What’s the value of rehashing it? How can we honor, forgive, or live with people who have done difficult things?

Mattison tells several stories in Conscience, and watching them grow and intersect is one of the greatest pleasures of the book. The first story begins in the mid-1960s, in Brooklyn, with three young women who become involved in the antiwar protests: Helen Weinstein, a serious girl who drops out of Barnard after she is radicalized; Valerie (Val) Benevento, a popular girl who will eventually write a successful book about Helen’s life; and Olive Grossman, Helen’s best friend, an editor who now lives in New Haven with her husband, Griff, the hard-working principal of a school for troubled kids, a gentle man who is marked, like Olive, by a violent incident that happened in the ’60s. Helen is the most compelling character in the novel, and it is Olive’s need to make sense of Helen’s life that moves the story forward.

Several other plot lines unfold over the course of the novel: Olive and Griff face an impasse in their marriage; the complex arcs of several female friendships are explored; and Olive finds the courage to tell the truth about her relationship with Helen, getting past what Virginia Woolf famously called the “angel in the house,” that dreadful expectation that women should be sweet and charming, avoiding conflict at all cost. Finally, there is the more contemporary story of a slightly younger woman named Jean, who runs a homeless shelter in New Haven. Her friendship with Olive dominates the second half of the book.

Conscience is told in alternating first-person voices. The shifting perspective works well, as a chorus of “I”s (there are three of them — Olive, Jean, and, to a lesser extent, Griff) helps build a collective sense of the collateral damage of the war and the noisy overlap of friends, family, and lovers that make up a community. At a certain point, the voices seem to blend and merge, becoming almost one, a tactile illustration of some of Mattison’s larger themes: family, friendship, community. The alternating voices also give the reader an intimate view of Olive and Griff’s marriage. Personal space is an important concern in the novel (especially for its female characters), and there are interesting issues related to the architecture of Olive and Griff’s house. Originally a duplex (Griff lived upstairs and Olive downstairs during a time of marital separation), the two units are now connected, but to some extent, the separation remains. Olive, who has a home office she never uses (strange since she is always craving solitude), spreads her work over the kitchen table, which annoys and pains Griff, who retreats upstairs or leaves the house. They often eat alone. As each character recounts their version of this conflict, the reader, like a couples’ therapist, pieces together their troubles, sees the misperceptions and the self-deceptions, and feels the loss of what might have been. In another example of Mattison’s clever use of shifting perspectives, Val’s book, which we learn about as Jean reads it, offers a different perspective on Olive’s and Griff’s versions of Helen’s story.

Most of the plot elements fit together neatly, something we have come to expect from Mattison, who is very good with form. But characters, like Olive and Griff’s oldest daughter, are sometimes brought in to serve the plot, never to return. And some of Mattison’s plot twists feel improbable, especially the ones that are centered around Zach, a young pediatrician who was once involved with Olive and Griff’s daughter and is now involved with Jean. The New Haven story doesn’t have the same intensity as the Brooklyn one, and the friendship between Olive and Jean is not as convincing as the one between Olive and Helen.

But Conscience is a curious book. Every time I wanted to object, Mattison pulled me back in, some of which, I think, is connected to the book’s pacing, which is wonderfully slow and lush. Fiction tends to move at a fast clip these days — it’s full of fragments and ellipses, abrupt shifts that reflect our accelerated, decentered lives. But Mattison refuses to give up the rich, mundane details of domestic life — people talking, cooking, washing the dishes. It’s where her stories live.

Many of Mattison’s characters are well drawn: from important figures like Jean and Zach to minor characters like Eli, an older activist who sleeps with everyone (“[p]utting his hands on both our shoulders, he drew us into his apartment”), and some of the people at the shelter where Jean works. The youthful portraits of Olive and Helen are full of poignant details: from the windy walks they take in Brooklyn to get away from their families to Helen’s growing indifference to money, food, and hygiene. Mattison’s honesty about the less-than-noble motivations that sometimes drive the actions of her characters — to please a friend, to have sex, to get away from their parents — is refreshing. She doesn’t idealize; there are no heroes in this book — on the contrary. Mostly, we see the toll the war takes, the way each character struggles with the dictates of his or her conscience as the government continues to send young men off to war, continues to bomb and kill in Vietnam. As Olive says, “Being preoccupied by the war was something like having such a bad cold that you didn’t care what happened in your life.”

Several of the characters turn to violence. Some of them are destroyed by this and some of them repudiate it, but all of them feel guilty about what they did and didn’t do. Trying to make sense of the choices Helen made, Olive asks some questions that haunt the book: “What should she have done — what should I have done — to end the war? What should we have done instead? To say ‘nothing’ would condemn us to complicity.” Mattison never condemns the characters who opt for violence, but in the present-day story, where characters like Jean and Griff work tirelessly to help troubled kids and the homeless, she offers us a compelling alternative. The most interesting character in this regard is Griff, the agnostic son in a long line of New Haven clergymen, whose youthful act of violence changed his life. Unfortunately, we don’t understand as much about his choice as we do about Helen’s although we see the ways in which his life is circumscribed by it. Every decision he makes involves a painstaking consideration of the potential harm it may do to others, which causes some problems with Olive, but Griff’s condemnation of violence allows for no exceptions: “What’s wrong […] is wrong. What is destructive […] [d]estroys.”

From her earliest work, a 1979 poetry collection called Animals, Mattison has been invested in telling women’s stories, giving women space on the page. The female characters in Conscience are part of a long line of women — working women, sexual women, family women, thinking women — whose lives Mattison has lovingly captured and explored. Her portrayal of the men whose lives intersect with the lives of her female characters is usually nuanced and complex; they are sweet, distant, sexy, needy, human. But in Conscience, this isn’t always the case, which has to do, I think, with the character of Olive and the outsized role she plays in the book.

As a young woman, Olive is a little neurotic, the kind of girl who worries about being “liked” by other girls, a “secondary character,” as she once calls herself. Her political activism takes a back seat to Helen’s; her desire for approval eventually leads her to be used and burned by Val. As an adult, Olive is lonely; she feels abandoned by Helen, exhausted by the hard work of carving out a space for her career within the confines of marriage. Mostly, though, she’s angry at Griff, whom she blames for many of her problems, in ways that are sometimes tedious, even absurd. Griff can be a tough character, inexpressive and inflexible, but Mattison never succeeded in convincing me that Olive’s problems are his fault, and he comes off as a passive foil, a stand-in for the traditional inequity of male-female relationships. At a certain point, Olive’s critique of Griff is so egregious that I thought the book was going to be about how she recognizes and addresses this, but Mattison’s sympathies remain firmly with Olive. At the end of the book, when Olive agrees to a kitchen renovation that will create a space where she and Griff can coexist, it’s meant to signal love and acceptance, but it really feels like she’s throwing him some crumbs.

You could argue that Griff gets second billing because he’s a male character in a book about female empowerment, but Griff is also black, one of several black characters in the novel, none of whom have much of a voice, and this disparity becomes increasingly apparent as the novel unfolds. Over the course of her career, Mattison’s work has often been set in the world of social justice, including the Civil Rights movement, but her tendency — the old left’s tendency — to divide the world along the lines of race, gender, and ethnicity (black, Jewish, male, female) doesn’t serve the part of her story that takes place in New Haven in the 21st century.

Underlying the problems between Olive and Griff is the pressing question of how men and women (especially women) can live together with autonomy. Mattison, who places a great deal of value on family and community, can’t quite wrap her mind around it, but the novel hints at an intriguing solution. For years, I was married to an architect who had a theory — a convincing one — that many people’s problems are actually architectural problems, problems that can be resolved with architectural solutions, and I followed the architectural trail in the book eagerly. The repurposed duplex, Olive’s unsuccessful quest for a secluded work space, the third floor of Jean’s shelter that controversially offers “private space” — space to read or think or nap — to homeless people in New Haven. In Conscience, Olive and Griff are trapped in a marriage — and in a house — that doesn’t suit them. Could it be that some couples can’t coexist, at least in the traditional ways that couples have always coexisted in the Western world (another issue the ’60s tried, with limited success, to address)? Besides, Olive is a writer, and most writers, male or female, need solitary conditions to work in, conditions that often clash with family life. Mattison is hesitant to liberate Olive and Griff from a traditional marital structure, one that has created a terrible choice for them — a stifling marriage or an unhappy solitude. But what if that dichotomy were false? What if there was another solution, one that occurs, at one point, to Olive, almost as a joke: bring back the duplex!

In Conscience, Alice Mattison gives us an intimate portrait of the struggles and sacrifices of the men and women who protested against the war in Vietnam, some of whom, for better or worse, put their lives on the line. She also reminds us of what it is to have, and act on, a conscience, what it is to make a choice and accept the consequences. As Olive, trying to explain those difficult times to Zach, says, “The sixties weren’t—’ I didn’t know how to put it. ‘We were serious.’” As a new generation of protestors fights to defend our democracy against a different kind of threat, it’s good to remember the long, successful legacy of protests in this country, important to reflect on the risks and rewards of dissent.

It takes a long time to make sense of things, to paint a full picture of an important moment in history, especially one as fraught as the war in Vietnam, but this is the luxury (and, perhaps, the responsibility) of literature. And it should be applauded when it’s done well, as Mattison mostly does here.

¤

Lisa Fetchko has published essays, fiction, reviews, and translations in a variety of publications including Ploughshares, n+1, AGNI, and Bookforum. She teaches at Mount Saint Mary’s and Orange Coast College.

The post The Old Left: “Conscience” by Alice Mattison appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2Ng168h via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

IN THE EARLY 1980s, when I was a sophomore at Yale, I lived in a narrow clapboard house off-campus, somewhere east of Wooster Square. It wasn’t the happiest time in my life, but I had a small study with a big metal desk; my roommates were seniors, with one foot out the door; and there was a speakeasy around the corner where you could get a six-pack of beer on Sundays when everything else was closed.

We lived on the top floor; a couple in their 30s lived downstairs: the woman, who was Vietnamese, spoke little English and always looked frightened; her husband, who was white, was a Vietnam vet who would periodically get drunk and beat her. I’m not sure I would have had the courage to do so had I been living there alone, but my roommates often called the cops, who would come and intervene. My neighbors weren’t the first people I knew for whom the war in Vietnam hadn’t ended — I had friends in Pennsylvania whose older brothers had come back, completely changed. My stepfather, a mild-mannered neurosurgeon who had been a doctor in a busy MASH unit, would occasionally belt back a couple of drinks and fly into an inexplicable rage. I was curious about these people, wondered about the experiences that haunted them. But the war, and the protests surrounding it, seemed remote, something I would never comprehend in the way that we can’t really comprehend things we don’t live through, experiences whose most intimate details we will never know.

In Alice Mattison’s new novel, Conscience, we meet two characters for whom the war has not ended either. The novel, which is set in present-day New Haven (where Mattison lives and often sets her stories), is Mattison’s 14th book, her seventh novel in a long, distinguished career as a writer and a teacher. In an author’s note, she explains that the book grew out of her curiosity about an idealistic young woman she met in the ’60s who later “turned violent.” Among other things, the novel poses some interesting questions: How long does the past linger? What’s the value of rehashing it? How can we honor, forgive, or live with people who have done difficult things?

Mattison tells several stories in Conscience, and watching them grow and intersect is one of the greatest pleasures of the book. The first story begins in the mid-1960s, in Brooklyn, with three young women who become involved in the antiwar protests: Helen Weinstein, a serious girl who drops out of Barnard after she is radicalized; Valerie (Val) Benevento, a popular girl who will eventually write a successful book about Helen’s life; and Olive Grossman, Helen’s best friend, an editor who now lives in New Haven with her husband, Griff, the hard-working principal of a school for troubled kids, a gentle man who is marked, like Olive, by a violent incident that happened in the ’60s. Helen is the most compelling character in the novel, and it is Olive’s need to make sense of Helen’s life that moves the story forward.

Several other plot lines unfold over the course of the novel: Olive and Griff face an impasse in their marriage; the complex arcs of several female friendships are explored; and Olive finds the courage to tell the truth about her relationship with Helen, getting past what Virginia Woolf famously called the “angel in the house,” that dreadful expectation that women should be sweet and charming, avoiding conflict at all cost. Finally, there is the more contemporary story of a slightly younger woman named Jean, who runs a homeless shelter in New Haven. Her friendship with Olive dominates the second half of the book.

Conscience is told in alternating first-person voices. The shifting perspective works well, as a chorus of “I”s (there are three of them — Olive, Jean, and, to a lesser extent, Griff) helps build a collective sense of the collateral damage of the war and the noisy overlap of friends, family, and lovers that make up a community. At a certain point, the voices seem to blend and merge, becoming almost one, a tactile illustration of some of Mattison’s larger themes: family, friendship, community. The alternating voices also give the reader an intimate view of Olive and Griff’s marriage. Personal space is an important concern in the novel (especially for its female characters), and there are interesting issues related to the architecture of Olive and Griff’s house. Originally a duplex (Griff lived upstairs and Olive downstairs during a time of marital separation), the two units are now connected, but to some extent, the separation remains. Olive, who has a home office she never uses (strange since she is always craving solitude), spreads her work over the kitchen table, which annoys and pains Griff, who retreats upstairs or leaves the house. They often eat alone. As each character recounts their version of this conflict, the reader, like a couples’ therapist, pieces together their troubles, sees the misperceptions and the self-deceptions, and feels the loss of what might have been. In another example of Mattison’s clever use of shifting perspectives, Val’s book, which we learn about as Jean reads it, offers a different perspective on Olive’s and Griff’s versions of Helen’s story.

Most of the plot elements fit together neatly, something we have come to expect from Mattison, who is very good with form. But characters, like Olive and Griff’s oldest daughter, are sometimes brought in to serve the plot, never to return. And some of Mattison’s plot twists feel improbable, especially the ones that are centered around Zach, a young pediatrician who was once involved with Olive and Griff’s daughter and is now involved with Jean. The New Haven story doesn’t have the same intensity as the Brooklyn one, and the friendship between Olive and Jean is not as convincing as the one between Olive and Helen.

But Conscience is a curious book. Every time I wanted to object, Mattison pulled me back in, some of which, I think, is connected to the book’s pacing, which is wonderfully slow and lush. Fiction tends to move at a fast clip these days — it’s full of fragments and ellipses, abrupt shifts that reflect our accelerated, decentered lives. But Mattison refuses to give up the rich, mundane details of domestic life — people talking, cooking, washing the dishes. It’s where her stories live.

Many of Mattison’s characters are well drawn: from important figures like Jean and Zach to minor characters like Eli, an older activist who sleeps with everyone (“[p]utting his hands on both our shoulders, he drew us into his apartment”), and some of the people at the shelter where Jean works. The youthful portraits of Olive and Helen are full of poignant details: from the windy walks they take in Brooklyn to get away from their families to Helen’s growing indifference to money, food, and hygiene. Mattison’s honesty about the less-than-noble motivations that sometimes drive the actions of her characters — to please a friend, to have sex, to get away from their parents — is refreshing. She doesn’t idealize; there are no heroes in this book — on the contrary. Mostly, we see the toll the war takes, the way each character struggles with the dictates of his or her conscience as the government continues to send young men off to war, continues to bomb and kill in Vietnam. As Olive says, “Being preoccupied by the war was something like having such a bad cold that you didn’t care what happened in your life.”

Several of the characters turn to violence. Some of them are destroyed by this and some of them repudiate it, but all of them feel guilty about what they did and didn’t do. Trying to make sense of the choices Helen made, Olive asks some questions that haunt the book: “What should she have done — what should I have done — to end the war? What should we have done instead? To say ‘nothing’ would condemn us to complicity.” Mattison never condemns the characters who opt for violence, but in the present-day story, where characters like Jean and Griff work tirelessly to help troubled kids and the homeless, she offers us a compelling alternative. The most interesting character in this regard is Griff, the agnostic son in a long line of New Haven clergymen, whose youthful act of violence changed his life. Unfortunately, we don’t understand as much about his choice as we do about Helen’s although we see the ways in which his life is circumscribed by it. Every decision he makes involves a painstaking consideration of the potential harm it may do to others, which causes some problems with Olive, but Griff’s condemnation of violence allows for no exceptions: “What’s wrong […] is wrong. What is destructive […] [d]estroys.”

From her earliest work, a 1979 poetry collection called Animals, Mattison has been invested in telling women’s stories, giving women space on the page. The female characters in Conscience are part of a long line of women — working women, sexual women, family women, thinking women — whose lives Mattison has lovingly captured and explored. Her portrayal of the men whose lives intersect with the lives of her female characters is usually nuanced and complex; they are sweet, distant, sexy, needy, human. But in Conscience, this isn’t always the case, which has to do, I think, with the character of Olive and the outsized role she plays in the book.

As a young woman, Olive is a little neurotic, the kind of girl who worries about being “liked” by other girls, a “secondary character,” as she once calls herself. Her political activism takes a back seat to Helen’s; her desire for approval eventually leads her to be used and burned by Val. As an adult, Olive is lonely; she feels abandoned by Helen, exhausted by the hard work of carving out a space for her career within the confines of marriage. Mostly, though, she’s angry at Griff, whom she blames for many of her problems, in ways that are sometimes tedious, even absurd. Griff can be a tough character, inexpressive and inflexible, but Mattison never succeeded in convincing me that Olive’s problems are his fault, and he comes off as a passive foil, a stand-in for the traditional inequity of male-female relationships. At a certain point, Olive’s critique of Griff is so egregious that I thought the book was going to be about how she recognizes and addresses this, but Mattison’s sympathies remain firmly with Olive. At the end of the book, when Olive agrees to a kitchen renovation that will create a space where she and Griff can coexist, it’s meant to signal love and acceptance, but it really feels like she’s throwing him some crumbs.

You could argue that Griff gets second billing because he’s a male character in a book about female empowerment, but Griff is also black, one of several black characters in the novel, none of whom have much of a voice, and this disparity becomes increasingly apparent as the novel unfolds. Over the course of her career, Mattison’s work has often been set in the world of social justice, including the Civil Rights movement, but her tendency — the old left’s tendency — to divide the world along the lines of race, gender, and ethnicity (black, Jewish, male, female) doesn’t serve the part of her story that takes place in New Haven in the 21st century.

Underlying the problems between Olive and Griff is the pressing question of how men and women (especially women) can live together with autonomy. Mattison, who places a great deal of value on family and community, can’t quite wrap her mind around it, but the novel hints at an intriguing solution. For years, I was married to an architect who had a theory — a convincing one — that many people’s problems are actually architectural problems, problems that can be resolved with architectural solutions, and I followed the architectural trail in the book eagerly. The repurposed duplex, Olive’s unsuccessful quest for a secluded work space, the third floor of Jean’s shelter that controversially offers “private space” — space to read or think or nap — to homeless people in New Haven. In Conscience, Olive and Griff are trapped in a marriage — and in a house — that doesn’t suit them. Could it be that some couples can’t coexist, at least in the traditional ways that couples have always coexisted in the Western world (another issue the ’60s tried, with limited success, to address)? Besides, Olive is a writer, and most writers, male or female, need solitary conditions to work in, conditions that often clash with family life. Mattison is hesitant to liberate Olive and Griff from a traditional marital structure, one that has created a terrible choice for them — a stifling marriage or an unhappy solitude. But what if that dichotomy were false? What if there was another solution, one that occurs, at one point, to Olive, almost as a joke: bring back the duplex!

In Conscience, Alice Mattison gives us an intimate portrait of the struggles and sacrifices of the men and women who protested against the war in Vietnam, some of whom, for better or worse, put their lives on the line. She also reminds us of what it is to have, and act on, a conscience, what it is to make a choice and accept the consequences. As Olive, trying to explain those difficult times to Zach, says, “The sixties weren’t—’ I didn’t know how to put it. ‘We were serious.’” As a new generation of protestors fights to defend our democracy against a different kind of threat, it’s good to remember the long, successful legacy of protests in this country, important to reflect on the risks and rewards of dissent.

It takes a long time to make sense of things, to paint a full picture of an important moment in history, especially one as fraught as the war in Vietnam, but this is the luxury (and, perhaps, the responsibility) of literature. And it should be applauded when it’s done well, as Mattison mostly does here.

¤

Lisa Fetchko has published essays, fiction, reviews, and translations in a variety of publications including Ploughshares, n+1, AGNI, and Bookforum. She teaches at Mount Saint Mary’s and Orange Coast College.

The post The Old Left: “Conscience” by Alice Mattison appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2Ng168h

0 notes