#sir arthur thomas cotton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Forbidden Desire (Part Six)

Pairing: Thomas Shelby x Reader (Female/Incestuous)

Warnings: Incest (at this stage accidental), Age Gap, PTSD, Domestic Abuse, Self-Harm, Fluff, Smut

Words: 1,456

You heard a few more footsteps until the door was ripped wide open and you saw her. You looked her straight into the eyes which were filled with anger and you were barely quick enough to cover your naked body with the large white cotton that made up Tommy’s bed sheets.

“What is she doing here?” the brunette asked, causing Tommy to sit up and pull up his suit pants which, by this point, he had already gotten rid of simple for the sake of comfort.

“Lizzie, let’s talk downstairs, eh” he then said without bothering to put on any other clothing. He approached her as he spoke, but she pulled away from him and spat with anger.

“I cannot believe that you are fucking this whore” she cursed and Tommy immediately lifted his index finger, cautioning her.

“Lizzie, shut up and calm down” Tommy spat before pulling Lizzie into the hallway and shutting the door behind him.

“You don’t tell me to shut up Thomas! I am carrying your child and you need to show some fucking respect��� Lizzie argued as, slowly, but surely, she followed him downstairs and into his office.

“I will show you some fucking respect when you learn how to respect my guests. Y/N is one of them and I expect you to behave accordingly, eh’ Tommy told her angrily while, on the way to his office, lightening himself a cigarette which he retrieved from the pocket in his pants.

“Now tell me Lizzie, what’s wrong? Why are you here?” he then asked as, finally, they both reached his office. He took a seat while Lizzie stood in front of him with her arms crossed in protest.

“This woman you brought into your bedroom is a thief. She stole from the safe at the gambling den last night” Lizzie said rather angrily, causing Tommy’s eyebrows to furrow.

“How much is missing?” he asked, although he did not really appear to be concerned.

“A lot. About 10,000 pounds. Linda did two counts and we are exactly 10,000 pounds short and I am telling you that it was her. It must have been her” Lizzie tried to allege but, of course, Tommy had your back and chuckled.

“It couldn’t have been her Lizzie. She was with the night before, at the library” Tommy explained with a sense of calm in his voice and this frustrated Lizzie even more.

“At the library? She can’t even fucking read Tommy” Lizzie spat and Tommy answered her calmly again.

“I am teaching her” he explained and this surprised Lizzie. He really seemed to be making an effort with you and she did not understand why.

“You disgust me” Lizzie said before asking him whether he was in love with you.

“Perhaps I am” Tommy told her calmly again and, when she queried what this meant for her and her baby, Tommy began to think about it. It was not really something he had put his mind to just yet but he knew that, sometime soon, he had to make a decision and Lizzie reminded him of exactly that.

“You are in the run to become a Labour MP and I am not going to keep quiet about the baby being yours. Just keep that in mind when you fuck her” Lizzie threatened him and, as if the threat didn’t mean anything to him, he changed the topic. He knew that, ideally, he should be marrying her. It would be the right thing to do and increase his chances during the election. But, even for Tommy, marriage was something reserved for people who were in love and he was certainly not in love with Lizzie. He was in love with you.

***

After twenty minutes of talking to Lizzie about you and the stolen money and a couple of phone calls to Michael and Arthur, Tommy returned to his bedroom and saw that you had gone.

“The lady has left sir. But she did leave a rather cryptic note” Frances said as she noticed from the hallway that Tommy was looking for you.

“A note?” Tommy asked surprised and, when Frances handed it to him, he smiled.

“Gone Home. See you. Love, Y/N” was all it said and, considering that, until most recently, you could not even write out your own name, he was rather impressed by your efforts.

At home, however, you were met by a surprise and when you noticed some light shining through your apartment’s window, you pulled out the gun from your handbag which Tommy had given last night simply as a precaution.

Of course, you lacked experience when it came to shooting a gun but carrying and pointing one was often intimidating enough for any intruder to disappear. Thus, you opened the door to your unit just like this, with the gun in your hand, pointing inwards and into the direction of your living room.

“Who is it and what are you doing in my apartment?” you called out and, when you heard a familiar voice greeting you, you quickly lowered your weapon.

“Mother? Jesus! What are you doing here?” you asked as you put your gun away but your mother was furious already.

“What are you doing with a gun?” she yelled at you and, when you explained to her that you were carrying it simply as a precaution, she began to lecture you until you finally interrupted her.

“Can you please tell me why you are here?” you asked her again and she sighed before sitting back down at the kitchen table to sip on her cup of tea.

“I am here to check on you because I received this from a local member of the police. His name is Constable Moss” she told you before handing you letter which informed her that her husband had been found dead. Since he had been missing for a while, his death alone did not really surprise her, but the fact that he was shot was something that came as concern for her.

“You did this, didn’t you?” she then immediately alleged, seeing that you were carrying a gun and when you did not answer her right away, she began to yell again. “Answer me!” she demanded, which is when you smiled and shook your head.

“I didn’t do jack shit mother” you then said but she didn’t believe you.

“You killed him” she thus alleged again and, again, you shook your head.

“No, I didn’t. But I am glad that he is dead now. He deserved it and I am thankful to whomever was kind enough to pull the trigger” you then said and, for some reason, she was even more concerned about him having been shot now than before, when she assumed that it was you who had killed him.

“What is wrong with you child? Who did you get yourself involved with?” she asked, panicking, while roaming through the papers and letters scattered across your kitchen table/

“I got myself involved with people who can actually stand up for themselves” was all that you said until, suddenly, your mother picked up your latest pay cheque.

“Shelby Company Limited” she read out loud before giving you yet another lecture.

“I told you to stay away from the factories around here” she told you harshly but you did not want to hear it. You had enough of her trying to protect you after she failed to protect you from the monster who was your stepfather.

“I am not working at the factories, mother. I am working for Thomas Shelby. He has offices in town” you explained to her nonetheless in order to relief her from her concerns but, unbeknownst to you, telling her that you were working for this man himself made her worry even more.

“You must resign immediately” she told you and, when she spoke, it almost sounded like she was giving you an order.

“No” was your response. “I enjoy working for him and won’t be resigning” you explained.

“I beg you Y/N, just listen to me this one time. Resign and come back to Camden Town with me” she then begged you almost desperately but, again, you shook your head.

“No. I am done with this life. I like it here. Now please leave” you told her sternly, but she would not relent. This was too important to her and you did not quite know why.

“I am staying here for a few days Y/N. This is my apartment too. I will be departing Sunday afternoon” she then told you, causing you to roll your eyes.

“Fine. You should have the bed then as I have things to do” you told her before grabbing hold of your bag again with the intention to leave.

“Where are you going?” she asked but you did not answer her.

“I won’t be gone for long” was all you said before closing the door behind you.

Tags: @fastfan@elenavampire21@dolllol2405@allie131313@cilliansangel@coldbastille@kpopgirlbtssvt@cdej6@kathrinemelissa@landlockedmermaid77@crazymar15@damedomino @lauren-raines-x@miss-bunny19@skinny-bitch-juice@odorinana@cloudofdisney@weepingstudentfishhorse@allexiiisss@geminiwolves@letsstarsfalling@ysmmsy@chlorrox@tommyshelbypb@chocolatehalo@music-lover911@desperate-and-broken@mysticaldeanvoidhorse@peaky-cillian@lelestrangerandunusualdeetz@december16-1991@captivatedbycillianmurphy@romanogersendgame@randomfangirl2718@missymurphy1985@peakyscillian@lilymurphy03@deefigs@theflamecrystal@livinginfantaxy@rosey1981@hanster1998@fairypitou@zozeebo@kasaikawa@littleweirdoalien@sad-huffle-nerd@theflamecrystal@0ghostwriter0@stylescanbeatmyback@1-800-peakyblinders@datewithgianni@momoneymolife@mcntsee@janelongxox@basiclassy@being-worthy@chaotic-bean-of-smolness@margoo0@vhscillian@crazymar15@im-constantly-fangirling@namelesslosers@littlewhiterose@ttzamara@cilleveryone@peaky-cillian@severewobblerlightdragon@dolllol2405@pkab@babaohhhriley@littleweirdoalien@alreadybroken-ts@masteroperator@stevie75@shabzy96@rainbow12346@obsessedwithfandomsx@geeksareunique@laysalespoir@paigem00@lkarls@vamp-army@luckystarme@myjumper@gxorg@eline-1806@goldenharrysworld@cristinagronk16@stylesofloki@faatxma@slut-for-matt-murdock@tpwkstiles@myjumper@cloudofdisney@look-at-the-soul@smellyzcat@kittycatcait219@theliterarybeldam@being-worthy@layazul@lyn07@kagilmore@50svibes@mainstreetlilly@ourthatgirlabby@bitchwhytho@takethee@registerednursejackie@sofi128@mrkdvidal1989@minxsblog@heidimoreton@laylasbunbunny@laylasbunbunny@queenshelby@camilleholland89@forgottenpeakywriter@vintagecherryt@indierockgirrl@mrkdvidal1989@bluesongbird@dudde-44@gasolinesavages@kissforvoid@bluebird592@1eugenia1isabella1@esposadomdp@lulunalua23@lovelace42@bookklover23@iwantmyredvelvetcupcake@moonmaiden1996@marlenamallowan@cyphah (cannot tag)@majesticcmey@cleverzonkwombatsludge@throughgoeshamilton@alessioayla@elenavampire21@justforfiction@cilliansangel@alannielaraye@satellitelh@pandoramyst@duckybird101@snixx2088@kylianswag@alessioayla@pono-pura-vida@iraisbored69@howling-wolf97@aesthetic0cherryblossom@weirdo-rules@lovemissyhoneybee@dazaiscum@esposadomd@etherealkistar@ur--mommy@throughgoeshamilton

#cillian murphy#cillian murphy fanfic#cillian murphy fanfiction#Tommy Shelby#tommy shelby fanfiction#tommy shelby imagine#thomas shelby#thomas shelby fanfic#thomas shelby imagine#thomas shelby x reader#tommy shelby x reader#tommy shelby x you#tommy shelby x y/n#thomas shelby x you#peaky blinders fanfiction#Peaky Blinders#cillian murphy smut#cillian murphy x reader#peaky blinders fanfic#peaky blinder#peaky blinders imagine

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Partial list of the books that Helene Hanff ordered from Marks & Co. and mentioned in 84, Charing Cross Road (alphabetical order):

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice, (1813)

Arkwright, Francis trans. Memoirs of the Duc de Saint-Simon

Belloc, Hillaire. Essays.

Catullus – Loeb Classics

Chaucer, Geoffrey The Canterbury Tales translated by Hill, published by Longmans 1934)

Delafield, E. M., Diary of a Provincial Lady

Dobson, Austen ed. The Sir Roger De Coverley Papers

Donne, John Sermons

Elizabethan Poetry

Grahame, Kenneth, The Wind in the Willows

Greek New Testament

Grolier Bible

Hazlitt, William. Selected Essays Of William Hazlitt 1778 To 1830, Nonesuch Press edition.

Horace – Loeb Classics

Hunt, Leigh. Essays.

Johnson, Samuel, On Shakespeare, 1908, Intro by Walter Raleigh

Jonson, Ben. Timber

Lamb, Charles. Essays of Elia, (1823).

Landor, Walter Savage. Vol II of The Works and Life of Walter Savage Landor (1876) – Imaginary Conversations

Latin Anglican New Testament

Latin Vulgate Bible / Latin Vulgate New Testament

Latin Vulgate Dictionary

Leonard, R. M. ed. The Book-Lover's Anthology, (1911)

Newman, John Henry. Discourses on the Scope and Nature of University Education. Addressed to the Catholics of Dublin – "The Idea of a University" (1852 and 1858)

Pepys, Samuel. Pepys Diary – 4 Volume Braybrook ed. (1926, revised ed.)

Plato's Four Socratic Dialogues, 1903

Quiller-Couch, Arthur, The Oxford Book Of English Verse

Quiller-Couch, Arthur, The Pilgrim's Way

Quiller-Couch, Arthur, Oxford Book of English Prose

Sappho – Loeb Classics

St. John, Christopher Ed. Ellen Terry and Bernard Shaw : A Correspondence / The Shaw – Terry Letters : A Romantic Correspondence

Sterne, Laurence, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, (1759)

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Virginibus Puerisque

de Tocqueville, Alexis Journey to America (1831–1832)

Wyatt, Thomas. Poems of Thomas Wyatt

Walton, Izaak and Charles Cotton. The Compleat Angler. (John Major's 2nd ed., 1824)

Walton, Izaak. The Lives of – John Donne – Sir Henry Wotton – Richard Hooker – George Herbert & Robert Sanderson

Woolf, Virginia, The Common Reader, 1932.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post # 143

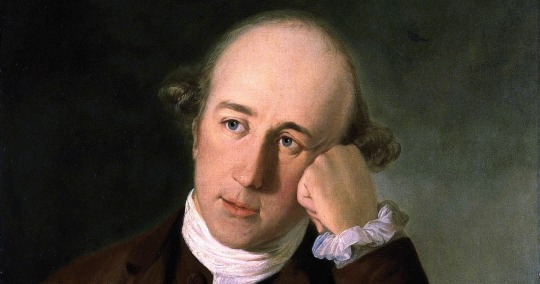

Cotton Dora

Three districts of Andhra Pradesh - East Godavari, West Godavari and Krishna - are littered with more than 3000 statues of a former East India Company official. These statues were built not by the British administration, but by locals of the districts.

On 15th May of every year, thousands of people, mostly farmers, but a few engineers, administrators, academics and politicians too assemble round these statues, pour milk on them, do puja with proper mantras and abhishekam, to celebrate the birth anniversary of this Englishman.

In 2009, an obscure body called the Andhra Pradesh Hindi Academy commissioned an agency to locate the tomb (final resting place) of this Englishman. The agency found the tomb in a village called Dorking, about 50 kms from London. So representatives of this body flew to Dorkings and put flowers on the tombstone to convey their respects to the man. The Telugu Association of London took up renovation of the tomb as their onus.

Now, who is this guy? And what did an Englishman, an East Indian Company official at that, do to deserve such feelings of respect and reverence amongst Indians?

Therein lies a tale.

This Englishman was Sir Arthur Cotton. He was a soldier, an engineer and an administrator with the British East India Company during the 19th century. And in 'an era of darkness' where the British fleeced Indian resources out of India and did very little for the population in return, this general worked on a dozen or so irrigation projects in South India and converted two areas into rice bowls of their respective provinces. Thanjavur became the rice bowl of present day Tamil Nadu, whereas districts surrounding Godavari and Krishna basins became the rice bowls of present day Andhra Pradesh. For the locals of these lands, he was Cotton Dora. Dora is an affectionate-cum-respectful term, meaning Master. His tombstone reads - Irrigation Cotton.

Arthur Cotton, aged 18 years, arrived in India in 1821, with the designation of Second Lieutenant and was attached to the office of the Chief Engineer of Madras presidency. It is said that he was as much an imperialist as his peers, but in 1826, he experienced a religious awakening. Thereafter, he decided that his mission was to work “for the glory of God…and the benefit of men". And he spent close to 50 years with the one idea that he believed could make a difference in India - Irrigation.

His talents for constructing irrigation structures were soon recognized by his superiors and he was entrusted with the task of constructing a dam across Cauvery river. Upon successful completion, he was promoted to the rank of Captain in 1828 and was entrusted with the work of investigation of all irrigation schemes in the presidency. His persistent efforts led to Thanjavur belt becoming the Rice bowl of Tamil Nadu.

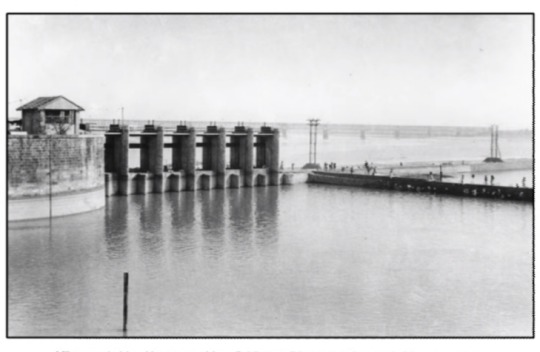

His masterpiece is, of course, the construction of Dowleshwaram barrage across the river Godavari in Andhra Pradesh. Dowleshwaram is a village within the vicinity of Rajamundry city, where Godavari is around 4km wide. When the rains in the Western Ghats would be heavy, the Godavari would be in spate. During summer, the Godavari would dry and nearby areas would be gripped by drought.

Arthur Cotton fought tooth and nail with his administration for a barrage over the river. Getting funds and resources for developmental work was not easy. When the Godavari project was sanctioned in 1847, Arthur Cotton asked for six engineers, eight juniors and 2,000 masons. Instead, he was allotted one young hand, two surveyors, and a few odd men. Yet he persevered. He studied and copied the method of construction used by the Cholas. He succeeded in completing the magnificent project on the Godavari river at Rajamundry in 1852.

As a tribute to him, a new barrage was constructed across the Godavari river, in 1982, upstream of the old one, and was named after him. It was dedicated to the nation by the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi. He is revered in the Godavari districts for making it the rice bowl of Andhra Pradesh.

After completing the Godavari barrage, Arthur Cotton shifted his attention to the construction of the aqueduct on Krishna River. The project was sanctioned in 1851 and completed by 1855.

But in 1952, a massive flood breached it. So in 1954, then Chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, Tanguturi Prakasam, laid the foundation for a new barrage. The project was completed in 1957, and was inaugurated by the then Chief Minister, Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy, who named it Prakasam Barrage.

In 1858, Arthur Cotton came up with an even more ambitious proposal - connecting all major rivers of India, and interlinking of canals and rivers - the precursor to today's National Water Grid project. Imagine that! About 160 years back! Below is the gist of his proposal. Of course, he didn't get the necessary funds.

Though Arthur Cotton rose through the ranks steadily, he was hated by his superiors for his service to the Indians. He was thwarted by administrative jealousy and was called a “wild enthusiast" with “water in his head". At one point, impeachment proceedings were initiated by his superiors for his dismissal. He was also summoned to the appear before a House of Commons Committee to justify his proposal to build a barrage across the Godavari. He supposedly said, "My Lord, one day's flow in the Godavari river during high floods is equal to one whole year's flow in the Thames of London".

His biggest bone of contention was with the massive railway lobby amidst the administration. He kept on making the point that railways bled India and Indians, while irrigation gave life to Indians. Because the sole reason why the British invested in Indian railways was the efficient transfer of tradable goods to shipping ports so that wealth can be siphoned off to their British headquarters. He rued the disproportionate investments made in railways vis-a-vis irrigation.

Arthur Cotton retired from service in 1860 and left India. He was knighted in 1861.

This post is a tribute to Sir Arthur Thomas Cotton, Cotton Dora to the folks in Andhra Pradesh, Cotton Dorai, to the locals in Tamil Nadu, a rare Englishman, who worked to improve the lot of the people he conquered.

#sir arthur cotton barrage#sir arthur thomas cotton#sir arthur Cotton#cotton dora#cotton dorai#dowleshwaram barrage#prakasham barrage#rice bowl#godavari river#krishna river#thanjavur#irrigation#irrigation cotton

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

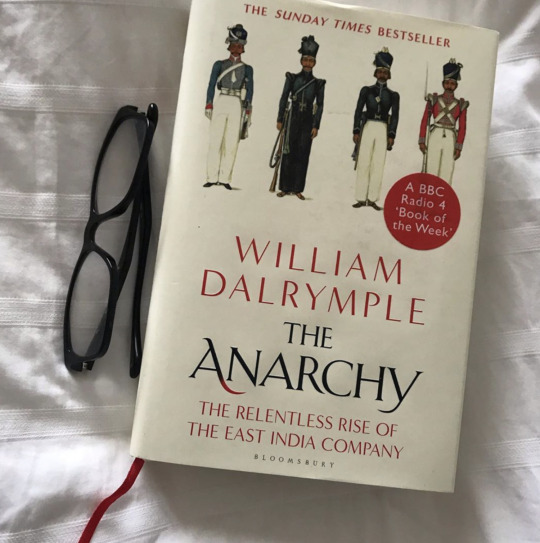

Treat Your S(h)elf: The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise Of The East India Company (2019)

It was not the British government that began seizing great chunks of India in the mid-eighteenth century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by a violent, utterly ruthless and intermittently mentally unstable corporate predator – Clive.

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise Of The East India Company

“One of the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: loot. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this word was rarely heard outside the plains of north India until the late eighteenth century, when it became a common term across Britain.”

With these words, populist historian William Dalrymple, introduces his latest book The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. It is a perfect companion piece to his previous book ‘The Last Mughal’ which I have also read avidly. I’m a big fan of William Dalrymple’s writings as I’ve followed his literary output closely.

And this review is harder to be objective when you actually know the author and like him and his family personally. Born a Scot he was schooled at Ampleforth and Cambridge before he wrote his first much lauded travel book (In Xanadu 1989) just after graduation about his trek through Iran and South Asia. Other highly regarded books followed on such subjects as Byzantium and Afghanistan but mostly about his central love, Delhi. He has won many literary awards for his writings and other honours. He slowly turned to writing histories and co-founding the Jaipur Literary Festival (one of the best I’ve ever been to). He has been living on and off outside Delhi on a farmhouse rasing his children and goats with his artist wife, Olivia. It’s delightfully charming.

Whatever he writes he never disappoints. This latest tome I enjoyed immensely even if I disagreed with some of his conclusions.

Dalrymple recounts the remarkable rise of the East India Company from its founding in 1599 to 1803 when it commanded an army twice the size of the British Army and ruled over the Indian subcontinent. Dalrymple targets the British East India Company for its questionable activities over two centuries in India. In the process, he unmasks a passel of crude, extravagant, feckless, greedy, reprobate rascals - the so-called indigenous rulers over whom the Company trampled to conquer India.

None of this is news to me as I’m already familiar with British imperial history but also speaking more personally. Like many other British families we had strong links to the British Empire, especially India, the jewel in its crown. Those links went all the way back to the East India Company. Typically the second or third sons of the landed gentry or others from the rising bourgeois classes with little financial prospects or advancement would seek their fortune overseas and the East India Company was the ticket to their success - or so they thought.

The East India Company tends to get swept under the carpet and instead everyone focuses on the British Empire. But the birth of British colonialism wasn’t engineered in the halls of Whitehall or the Foreign Office but by what Dalrymple calls, “handful of businessmen from a boardroom in the City of London”. There wasn’t any grand design to speak of, just the pursuit of profit. And it was this that opened a Pandora’s Box that defined the following two centuries of British imperialism of India and the rise of its colonial empire.

The 18th-century triumph and then fall of the Company, and its role in founding what became Queen Victoria’s Indian empire is an astonishing story, which has been recounted in books including The Honourable Company by John Keay (1991) and The Corporation that Changed the World by Nick Robins (2006). It is well-trodden territory but Dalrymple, a historian and author who lives in India and has written widely about the Mughal empire, brings to it erudition, deep insight and an entertaining style.

He also takes a different and topical twist on the question how did a joint stock company founded in Elizabethan England come to replace the glorious Mughal Empire of India, ruling that great land for a hundred years? The answer lies mainly in the title of the book. The Anarchy refers not to the period of British rule but to the period before that time. Dalrymple mentions his title is drawn from a remark attributed to Fakir Khair ud-Din Illahabadi, whose Book of Admonition provided the author with the source material and who said of the 18th century “the once peaceful realm of India became the abode of Anarchy.” But Dalrymple goes further and tells the story as a warning from history on the perils of corporate power. The American edition sports the provocative subtitle, “The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire” (compared with the neutral British subtitle, “The Relentless Rise of the East India Company”). However I think the story Dalrymple really tells is also of how government power corrupts commercial enterprise.

It’s an amazing story and Dalrymple tells it with verve and style drawing, as in his previous books, on underused Indian, Persian and French sources. Dalrymple has a wonderful eye for detail e.g. After the Company’s charter is approved in 1600 the merchant adventures scout for ships to undertake the India voyage: “They have been to Deptford to ‘view severall shippes,’ one of which, the May Flowre, was later famous for a voyage heading in the opposite direction”.

What a Game of Thrones styled tv series it would make, and what a tragedy it unfolded in reality. A preface begins with the foundation of the Company by “Customer Smythe” in 1599, who already had experience trading with the Levant. Certain merchants were little better than pirates and the British lagged behind the Dutch, the Portuguese, the French and even the Spanish in their global aspirations. It was with envious eyes that they saw how Spain had so effectively despoiled Central America. The book fast-forwards to 1756, with successive chapters, and a degree of flexibility in chronology, taking the reader up to 1799. What was supposed to be a few trading posts in India and an import/export agreement became, within a century, a geopolitical force in its own right with its own standing army larger than the British Army.

It is a story of Machiavels from both Britain and India, of pitched battles, vying factions, the use of technology in warfare, strange moments of mutual respect, parliamentary impeachment featuring two of the greatest orators of the day (Edmund Burke and Richard Sheridan), blindings, rapes, psychopaths on both sides, unimaginable wealth, avarice, plunder, famine and worse. It is, in particular – because of the feuding groups loyal to the Mughals, the Marathas, the Rohilla Afghans, the so-called “bankers of the world” the Jagat Seths, and local tribal warlords – a kind of Game Of Thrones with pepper, silk and saltpetre. And that is even before we get to the British, characters such as Robert Clive “of India”, victor at the Battle of Plassey and subsequent suicide; the problematic figure of the cultured Warren Hastings, the whistle-blower who became an unfair scapegoat for Company atrocities; and Richard Wellesley, older brother to the more famous Arthur who became the Duke of Wellington. Co-ordinating such a vast canvas requires a deft hand, and Dalrymple manages this (although the list of dramatis personae is useful). There is even a French mercenary who is described as a “pastry cook, pyrotechnic and poltroon”.

When the Red Dragon slipped anchor at Woolwich early in 1601 to exploit the new royal charter granted to the East India Company, the venture started inauspiciously. The ship lay becalmed off Dover for two months before reaching the Indonesian sultanate of Aceh and seizing pepper, cinnamon and cloves from a passing Portuguese vessel. The Company was a strange beast from the start “a joint stock company founded by a motley bunch of explorers and adventurers to trade the world’s riches. This was partly driven by Protestant England’s break with largely Catholic continental Europe. Isolated from their baffled neighbours, the English were forced to scour the globe for new markets and commercial openings further afield. This they did with piratical enthusiasm” William Dalrymple writes. From these Brexit-like roots, it grew into an enterprise that has never been replicated “a business with its own army that conquered swaths of India, seizing minerals, jewels and the wealth of Mughal emperors. This was mercenary globalisation, practised by what the philosopher Edmund Burke called “a state in the guise of a merchant””.

The East India Company’s charter began with an original sin - Elizabeth I granted the company a perpetual monopoly on trade with the East Indies. With its monopoly giving it enhanced access to credit and vast wealth from Indian trade, it’s no surprise that the company grew to control an eighth of all Britain’s imports by the 1750s. Yet it was still primarily a trading company, with some military capacity to defend its factories. That changed thanks to a well-known problem in institutional economics - opportunism by a company agent, in this case Robert Clive of India, who in time became the richest self-made man in the world in time.

Like many start-ups, it had to pivot in its early days, giving up on competing with the entrenched Dutch East India Company in the Spice Islands, and instead specialising in cotton and calico from India. It was an accidental strategy, but it introduced early officials including Sir Thomas Roe to “a world of almost unimaginable splendour” in India, run by the cultured Mughals.

The Nawab of Bengal called the English “a company of base, quarrelling people and foul dealers”, and one local had it that “they live like Englishmen and die like rotten sheep”. But the Company had on its side the adaptiveness and energy of capitalism. It also had a force of 260,000, which was decisive when it stopped negotiating with the Mughals and went to war. After the Battle of Buxar in 1764, “the English gentlemen took off their hats to clap the defeated Shuja ud-Daula, before reinstalling him as a tame ruler, backed by the Company’s Indian troops, and paying it a huge subsidy. “We have at last arrived at that critical Conjuncture, which I have long foreseen” wrote Robert Clive, the “curt, withdrawn and socially awkward young accountant” whose risk-taking and aggression secured crucial military victories for the Company. It was a high point for “the most opulent company in the world,” as Robert Clive described it.

So how was a humble group of British merchants able to take over one of the great empires of history? Under Aurangzeb, the fanatic and ruthless Mughal emperor (1658-1707), the empire grew to its largest geographic extent but only because of decades of continuous warfare and attendant taxing, pillaging, famine, misery and mass death. It was a classic case of the eventual fall of a great power through military over-extension.

At Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, a power struggle ensued but none could command. “Mughal succession disputes and a string of weak and powerless emperors exacerbated the sense of imperial crisis: three emperors were murdered (one was, in addition, first blinded with a hot needle); the mother of one ruler was strangled and the father of another forced off a precipice on his elephant. In the worst year of all, 1719, four different Emperors occupied the Peacock Throne in rapid succession. According to the Mughal historian Khair ud-Din Illahabadi … ‘Disorder and corruption no longer sought to hide themselves and the once peaceful realm of India became a lair of Anarchy’”.

Seeing the chaos at the top, local rulers stopped paying tribute and tried to establish their own power bases. The result was more warfare and a decline in trade as banditry made it unsafe to travel. The Empire appeared ripe to fall. “Delhi in 1737 had around 2 million inhabitants. Larger than London and Paris combined, it was still the most prosperous and magnificent city between Ottoman Istanbul and Imperial Edo (Tokyo). As the Empire fell apart around it, it hung like an overripe mango, huge and inviting, yet clearly in decay, ready to fall and disintegrate”.

In 1739 the mango was plucked by the Persian warlord Nader Shah. Using the latest military technology, horse-mounted cannon, Shah devastated a much larger force of Mughal troops and “managed to capture the Emperor himself by the simple ruse of inviting him to dinner, then refusing to let him leave.” In Delhi, Nader Shah massacred a hundred thousand people and then, after 57 days of pillaging and plundering, left with two hundred years’ worth of Mughal treasure carried on “700 elephants, 4,000 camels and 12,000 horses carrying wagons all laden with gold, silver and precious stones”.

At this time, the East India Company would have probably preferred a stable India but through a series of unforeseen events it gained in relative power as the rest of India crumbled. With the decline of the Mughals, the biggest military power in India was the Marathas and they attacked Bengal, the richest Indian province, looting, plundering, raping and killing as many as 400,000 civilians. Fearing the Maratha hordes, Bengalis fled to the only safe area in the region, the company stronghold in Calcutta. “What was a nightmare for Bengal turned out to be a major opportunity for the Company. Against artillery and cities defended by the trained musketeers of the European powers, the Maratha cavalry was ineffective. Calcutta in particular was protected by a deep defensive ditch especially dug by the Company to keep the Maratha cavalry at bay, and displaced Bengalis now poured over it into the town that they believed offered better protection than any other in the region, more than tripling the size of Calcutta in a decade. … But it was not just the protection of a fortification that was the attraction. Already Calcutta had become a haven of private enterprise, drawing in not just Bengali textile merchants and moneylenders, but also Parsis, Gujaratis and Marwari entrepreneurs and business houses who found it a safe and sheltered environment in which to make their fortunes”. In an early example of what might be called a “charter city,”

English commercial law also attracted entrepreneurs to Calcutta. The “city’s legal system and the availability of a framework of English commercial law and formal commercial contracts, enforceable by the state, all contributed to making it increasingly the destination of choice for merchants and bankers from across Asia”.

The Company benefited by another unforeseen circumstance, Siraj ud-Daula, the Nawab (ruler) of Bengal, was a psychotic rapist who got his kicks from sinking ferry boats in the Ganges and watching the travelers drown. Siraj was uniformly hated by everyone who knew him. “Not one of the many sources for the period — Persian, Bengali, Mughal, French, Dutch or English — has a good word to say about Siraj”. Despite his flaws, Siraj might have stayed in power had he not made the fatal mistake of striking his banker. The Jagat Seth bankers took their revenge when Siraj ud-Daula came into conflict with the Company under Robert Clive. Conspiring with Clive, the Seths arranged for the Nawab’s general to abandon him and thus the Battle of Plassey was won and the stage set for the East India Company.

In typical fashion, Dalrymple devotes half a dozen pages to the Company’s defeat at Pollidur in 1780 by Haider Ali and his son, Tipu, but a few paragraphs to its significance (Haider could have expelled the Company from much of southern India but failed to pursue his advantage). The reader is not spared the gory details.

“Such as were saved from immediate death,” reads a quote from a British survivor about his fellow troops, “were so crowded together…several were in a state of suffocation, while others from the weight of the dead bodies that had fallen upon them were fixed to the spot and therefore at the mercy of the enemy…Some were trampled under the feet of elephants, camels, and horses. Those who were stripped of their clothing lay exposed to the scorching sun, without water and died a lingering and miserable death, becoming prey to ravenous wild animals.”

Many further battles and adventures would ensue before the British were firmly ensconced by 1803 but the general outline of the story remained the same. The EIC prospered due to a combination of luck, disarray among the Company’s rivals and good financing.

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam, for example, had been forced to flee Delhi leaving it to be ruled by a succession of Persian, Afghani and Maratha warlords. But after wandering across eastern India for many years, he regathered his army, retook Delhi and almost restored Mughal power. At a key moment, however, he invited into the Red Fort with open arms his “adopted” son, Ghulam Qadir. Ghulam was the actual son of Zabita Khan who had been defeated by Shah Alam sixteen years earlier. Ghulam, at that time a young boy, had been taken hostage by Shah Alam and raised like a son, albeit a son whom Alam probably used as a catamite. Expecting gratitude, Shah Alam instead found Ghulam driven mad. Ghulam Qadir, a psychopath, ordered a minion to blind Shah Alam: “With his Afghan knife….Qandahari Khan first cut one of Shah Alam’s eyes out of its socket; then, the other eye was wrenched out…Shah Alam flopped on the ground like a chicken with its neck cut.” Ghulam took over the Red Fort and after cutting out the eyes of the Mughal emperor, immediately calling for a painter to immortalise the event.

A few pages on, Ghulam Qadir gets his just dessert. Captured by an ally of the emperor, he is hung in a cage, his ears, nose, tongue, and upper lip cut off, his eyes scooped out, then his hands cut off, followed by his genitals and head. Dalrymple out-grosses himself with the description of Ahmad Shah Durrani, the Afghan invader of India, dying of leprosy with “maggots….dropping from the upper part of his putrefying nose into his mouth and food as he ate.”

By 1803, the Company’s army had defeated the Maratha gunners and their French officers, installed Shah Alam as a puppet back on his imitation Peacock Throne in Delhi, and the Company ruled all of India virtually.

Indeed as late as 1803, the Marathas too might have defeated the British but rivalry between Tukoji Holkar and Daulat Rao Scindia prevented an alliance. “Here Wellesley’s masterstroke was to send Holkar a captured letter from Scindia in which the latter plotted with Peshwa Baji Rao to overthrow Holkar … ‘After the war is over, we shall both wreak our full vengeance upon him.’ … After receiving this, Holkar, who had just made the first two days march towards Scindia, turned back and firmly declined to join the coalition”.

For Dalrymple the crucial point was the unsanctioned actions of Robert Clive and the bullying of Shah Alam in the rise of the East India Company.

The Jagat Seths then bribed the company men to attack Siraj. Clive, with an eye for personal gain, was happy attack Siraj at the behest of the Jagat Seths even if the company directors had no part in this. They “consistently abhorred ambitious plans of conquest,” he notes. Clive’s defeat of Siraj at Plassey and the subsequent chain of events that led to Shah Alam giving tax-raising powers to the company in 1765 may be history’s most egregious example of the principal-agent problem.

Thus, the East India Company acquired by accident the ultimate economic rent — a secure, unearned income stream. Company cronies initially thwarted attempts at oversight in London, but a government bailout in 1772 following the Bengal Famine and the collapse of Ayr Bank confirmed the crown’s interest in the company, which had now become Too Big to Fail. Adam Smith called the company’s twin roles of trader and sovereign a “strange absurdity” in Book IV of The Wealth of Nations (unfortunately, Smith’s long condemnatory discussion of the company receives only a cursory reference from Dalrymple).

As part of the bailout, Parliament passed the Tea Act to help the company dump its unsold products on the American colonies by giving it the monopoly on legal tea there (Americans drank mostly smuggled Dutch tea). This, of course, led to the Boston Tea Party and the American Revolution.

By 1784, Parliament had set up an oversight board that increasingly dictated the company’s political affairs. The attempted impeachment of Governor-General Warren Hastings by the House of Lords in 1788 confirmed that the company was no longer its own master. By that stage, the company was an arm of the state. Dalrymple’s coverage of the subsequent racist policies of Lord Cornwallis and the military adventures of Richard Wellesley make for compelling reading, but they are not examples of unfettered corporate power.

Overlaid on top of luck and disorder, was the simple fact that the Company paid its bills. Indeed, the Company paid its sepoys (Indian troops) considerably more than did any of its rivals and it paid them on time. It was able to do so because Indian bankers and moneylenders trusted the Company. “In the end it was this access to unlimited reserves of credit, partly through stable flows of land revenues, and partly through collaboration of Indian moneylenders and financiers, that in this period finally gave the Company its edge over their Indian rivals. It was no longer superior European military technology, nor powers of administration that made the difference. It was the ability to mobilise and transfer massive financial resources that enabled the Company to put the largest and best-trained army in the eastern world into the field”.

Dalrymple pretty much loses interest once the Company gains full control. “This book does not aim to provide a complete history of the East India Company,” he writes. He skips past one mention of Hong Kong, which the East India Company seized after the opium wars in China. A few sentences record the 1857 uprising of Indian soldiers that led to the British government taking India from the Company and establishing the Raj that lasted until Indian independence in 1947.

The author makes passing reference to the fact that the struggle for American independence was underway for much of the period about which he writes. He notes that It was British East India Company tea that patriots dumped into Boston harbor in 1773. American colonists were so grateful that the Mysore sultans tied up British forces that might have been deployed in America, they named a warship the Hyder Ali. Lord Cornwallis provides a connection, having surrendered to George Washington at Yorktown in 1781, an event confirming American independence, and turning up in 1786 in India as governor-general, taking Tipu Sultan’s surrender in 1792.

That reference raises an interesting side question that may someday deserve closer examination - Why were American colonists successful in driving off their British overlords. At the same time, Indian aristocracy and the masses over whom they ruled were unable to rid themselves of the British East India Company and the British Raj for another century?

No heroes emerge from Dalrymple’s expansive account that is rich, even overwhelming in detail. He covers two centuries but focuses on the period between 1765 and 1803 when the Company was transformed from a commercial operation to military and totalitarian — to use an appropriate term derived from Sanskrit - juggernaut. Among the multitude of characters involved in this sordid story are a few British names familiar in general history, Robert Clive of India, Warren Hastings, Lord Cornwallis, and Colonel Arthur Wellesley, who was better known long after he departed India as the Duke of Wellington. None - with the exception of Hastings - escape the scathing indictment of Dalrymple’s pen.

At the core of the story we meet Robert Clive, an emblematic character who from being a juvenile delinquent and suicidal lunatic rose to rule India, eventually killing himself in the aftermath of a corruption scandal. In particular Robert Clive comes in for much criticism by Dalrymple. After putting down one rebellion, Clive managed to send back £232 million, of which he personally received £22m. There was a rumour that, on his return to England, his wife’s pet ferret wore a necklace of jewels worth £2,500. Contrast that with the horrors of the 1769 famine: farmers selling their tools, rivers so full of corpses that the fish were inedible, one administrator seeing 40 dead bodies within 20 yards of his home, even cannibalism, all while the Company was stockpiling rice. Some Indian weavers even chopped off their own thumbs to avoid being forced to work and pay the exorbitant taxes that would be imposed on them. The Great Bengal famine of 1770 had already led to unease in London at its methods. “We have murdered, deposed, plundered, usurped,” wrote the Whig politician Horace Walpole. “I stand astonished by my own moderation,” Clive protested, after outrage intensified when the Company had to be bailed out by the British government in 1772. Clive took his own life in disgrace.

Warren Hastings, whom Dalrymple portrays as the more sensitive and sympathetic Company man, was first made governor general of India for 12 years and later endured seven years of impeachment for corruption before acquittal. Hastings showed “deep respect” for India and Indians, writes, Dalrymple, as opposed to most other Europeans in India to suck out as much as possible of the subcontinent’s resources and wealth. “In truth, I love India a little more than my own country,” wrote Hastings, who spoke good Bengali and Urdu, as well as fluent Persian. “(Edmund) Burke had defended Robert Clive (first Governor General of Bengal) against parliamentary enquiry, and so helped exonerate someone who genuinely was a ruthlessly unprincipled plunderer. Now he directed his skills of oratory against Warren Hastings (who was finally impeached), a man who, by virtue of his position, was certainly the symbol of an entire system of mercantile oppression in India, but who had personally done much to begin the process of regulating and reforming the Company, and who had probably done more than any other Company official to rein in the worst excesses of its rule,” Dalrymple writes. At his public impeachment hearing in 1788, Burke thundered: “We have brought before you…..one in whom all the frauds, all the peculation, all the violence, all the tyranny in India are embodied.’ They got the wrong man but, by the time he was cleared in 1795, the British state was steadily absorbing the Company, denouncing its methods but retaining many of its assets.

Dalrymple has a soft spot for a couple of Indian locals. “The British consistently portrayed Tipu as a savage and fanatical barbarian,” Dalrymple writes, “but he was in truth a connoisseur and an intellectual…” Of course, Tipu, Dalrymple confesses a bit later, had rebels’ “arms, legs, ears, and noses cut off before being hanged” as well as forcibly circumcising captives and converting them to Islam.

Emperor Shah Alam (1728-1806) is contemporary for much of the time Dalrymple covers. “His was…a life marked by kindness, decency, integrity and learning at a time when such qualities were in short supply…he…managed to keep the Mughul flame alive through the worst of the Great Anarchy….” Dalrymple portrays a most intriguing figure in Emperor Shah Alam, a man attracted to mysticism and yet as prepared as his contemporaries to double-deal; someone who endures exile and torture and who outlives, albeit in a melancholy fashion, his enemies. Despite his lack of wealth, troops or political power, the very nature of his being emperor still, it seems, inspired affection.

Part of Dalrymple’s excellence is in the use of Indian sources – he takes numerous quotes from Ghulam Hussain Khan, acclaimed by Dalrymple as “brilliant,” who threads the story as an 18th-century historian on his untranslated works, Seir Mutaqherin (Review of Modern Times). Dalrymple has used a trove of company documents in Britain and India as well as Persian-language histories, much of which he shares in English translation with the reader. However he does this a bit too often and portions of his account can seem more assembled than written.

These pages are also brimming with anecdotes retold with Dalrymple’s distinctive delight in the piquant, equivoque and gory: we have historical moments when “it seemed as if it were raining blood, for the drains were streaming with it” (quoted from a report c1740 regarding events that preceded Nadir Shah’s infamous looting of the peacock throne) as well as duels between Company officials so busy with their in-fighting that it’s a miracle they could perform their work at all; there’s also homosexuality, homophobia, sexual torture, castrations, cannibalism, brothels and gonorrhoea.

The principal protagonists of the “Black Hole of Calcutta” incident are both, naturally, certified pervs: Siraj ud-Daula is a “serial bisexual rapist” while his opponent Governor Drake is having an “affair with his sister”. And one particular Mughal governor liked to throw tax defaulters in pits of rotting shit (“the stench was so offensive, that it almost suffocated anyone who came near it”). All this gives one a rough idea of what historically important people were up to according to Dalrymple. But all things considered, Dalrymple’s research is solid and heavily annotated.

However entertaining and widely researched using unused Urdu and Persian sources, Dalrymple’s overall approach doesn’t tell us very much about the general tendency in eighteenth-century imperial activity, and particularly that of the British, that we didn’t already know. And other things he downplays or neglects. Thus, the East India Company was one of a series of ‘national’ East India companies, including those of France, the Netherlands and Sweden. Moreover, for Britain, there was the Hudson Bay Company, the Royal African Company, and the chartered companies involved in North America, as well, for example, as the Bank of England. Delegated authority in this form or shared state/private activities were a major part of governance. To assume from the modern perspective of state authority that this was necessarily inadequate is misleading as well as teleological. Indeed, Dalrymple offers no real evidence for his view. Was Portuguese India, where the state had a larger role, ‘better’?

Secondly, let us look at India as a whole. There is an established scholarly debate to which Dalrymple makes no ground breaking contribution. This debate focuses on the question of whether, after the death in 1707 of the mighty Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), the focus should be on decline and chaos or, instead, on the development of a tier of powers within the sub-continent, for example Hyderabad. In the latter perspective, the East India Company (EIC) emerges as one and, eventually, the most successful of the successor powers. That raises questions of comparative efficiency and how the EIC succeeded in the Indian military labour market, this helping in defeating the Marathas in the 1800s.

An Indian power, the EIC was also a ‘foreign’ one; although foreignness should not be understood in modern terms. As a ‘foreign’ one, the EIC was not alone among the successful players, and was not even particularly successful, other than against marginal players, until the 1760s. Compared to Nadir Shah of Persia in the late 1730s (on whom Michael Axworthy is well worth reading), or the Afghans from the late 1750s (on whom Jos Gommans is best), the EIC was limited on land. This was part of a longstanding pattern, encompassing indeed, to a degree, the Mughals. Dalrymple fails to address this comparative context adequately.

Dalrymple seems particularly incensed at “corporate violence” and in a (mercifully short) final chapter alludes to Exxon and the United Fruit Company. Indeed Dalrymple has a pitch ” that globalisation is rooted here, albeit that “the world’s largest corporations…..are tame beasts compared with the ravaging territorial appetites of the militarised East India Company.”

It is an interesting question to ask: How might the actions of these corporate raiders have differed from those of a state? It’s not clear, for example, that the EIC was any worse than the average Indian ruler and surely these stationary bandits were better than roving bandits like Nader Shah. The EIC may have looted India but economic historian Tirthankar Roy explains that: “Much of the money that Clive and his henchmen looted from India came from the treasury of the nawab. The Indian princes, ‘walking jeweler’s shops’ as an American merchant called them, spent more money on pearls and diamonds than on infrastructural developments or welfare measures for the poor. If the Company transferred taxpayers’ money from the pockets of an Indian nobleman to its own pockets, the transfer might have bankrupted pearl merchants and reduced the number of people in the harem, but would make little difference to the ordinary Indian.”

Moreover, although it began as a private-firm, the EIC became so regulated by Parliament that Hejeebu (2016) concludes, “After 1773, little of the Company’s commercial ethos survived in India.” Certainly, by the time the brothers Wellesley were making their final push for territorial acquisition, the company directors back in London were pulling out their hair and begging for fewer expensive wars and more trading profits.

So also for eighteenth-century Asia as a whole. Dalrymple has it in for the form of capitalism the EIC represents; but it was less destructive than the Manchu conquest of Xinjiang in the 1750s, or, indeed, the Afghan destruction of Safavid rule in Persia in the early 1720s. Such comparative points would have been offered Dalrymple the opportunity to deploy scholarship and judgment, and, indeed, raise interesting questions about the conceptualisation and methodologies of cross-cultural and diachronic comparison.

Focusing anew on India, the extent to which the Mughal achievement in subjugating the Deccan was itself transient might be underlined, and, alongside consideration, of the Maratha-Mughal struggle in the late seventeenth century, that provides another perspective on subsequent developments. The extent to which Bengal, for example, did not know much peace prior to the EIC is worthy of consideration. It also helps explain why so many local interests found it appropriate, as well as convenient, to ally with the EIC. It brought a degree of protection for the regional economy and offered defence against Maratha, Afghan, and other, attacks and/or exactions. The terms of entry into a British-led global economy were less unwelcome than later nationalist writers might suggest. Dalrymple himself cites Trotsky, who was no guide to the period. To turn to other specifics is only to underline these points.

After Warren Hastings’ impeachment which in effect brought to an end the era when “almost all of India south of [Delhi] was…..effectively ruled by a handful of businessmen from a boardroom in the City of London.” It is hard to find a simple lesson, beyond Dalrymple’s point that talk of Britain having conquered India ‘disguises a much more sinister reality’.

One of the great advantages non-fiction has over fiction is that you cannot make it up, and in the case of the East India Company, you cannot make it up to an extent that beggars belief. William Dalrymple has been for some years one of the most eloquent and assiduous chroniclers of Indian history. With this new work, he sounds a minatory note. The East India Company may be history, but it has warnings for the future. It was “the first great multinational corporation, and the first to run amok”. Wryly, he writes that at least Walmart doesn’t own a fleet of nuclear submarines and Facebook doesn’t have regiments of infantry.

Yet Facebook and Uber does indeed have the potential power to usurp national authority - Facebook can sway elections through its monopoly on how people consume their news for instance. But they do not seize physical territory as Dalrymple states. Even an oil company with private guards in a war-torn country does not compare these days. This doesn’t exonerate corporations though. I know from personal experience of working in the corporate world that it attracts its fair share of psychopaths and cold blooded operators obsessed with the bottom lines of their balance sheets and the worship of the fortunes of their share prices and the lengths they go to would indeed come close to or cross over moral and legal lines. Perhaps the moral is to keep a stern eye on ‘corporate influence, with its fatal blend of power, money and unaccountability’. Clive reflected after Buxar, ‘We must indeed become Nabobs ourselves in Fact if not in Name…..We must go forward, for to retract is impossible.’ That was the nature of the beast.

Speaking of being beastly, some readers may disagree with the more radical views presented in taking apart the imperialist project and showed it for what it was - not about civilising savages, but about brutally exploiting civilised humans by treating them as savages. I think that’s partly true but not the whole story as Dalrymple will freely concede himself. Imperial history is a charged subject and they defy lazy Manichean conclusions of good guys and bad guys.

Dalrymple’s book is an excellent example of popular history - engaging, entertaining, readable, and informative. However, I honestly think he should have stuck to the history and not tried to draw out a trustbusting parallel with today’s big companies. Where the parallels exist, they are to do with cronyism, rent-seeking, and bailouts, all of which are primarily sins of government.

The Anarchy remains though a page-turning history of the rise of the East India Company with plenty of raw material to enjoy and to think about. To my mind the title ‘The Anarchy’ is brilliantly and appositely chosen. There are in fact two anarchies here; the anarchy of the competing regimes in India, and the anarchy – literally, without leaders or rules – of the East India Company itself, a corporation that put itself above law. The dangers of power without governance are depicted in an exemplary fashion. Dalrymple has done a great service in not just writing an eminently readable history of 18th century India, but in reflecting on how so much of it serves as a warning for our own time when chaos runs amok from those seeking to be above the law.

#treat your s(h)elf#books#review#reading#bookgasm#book review#history#east india company#william dalrymple#the anrchy#britain#colonialism#imperialism#british history#india#personal

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you do a Thomas Shelby imagine where her tries to charm the readers parents who the reader lied and told them that Tommy moved away from his gangster life? Since the reader grew up around the Shelby’s being Ada’s best friend and Tommy loving her since their teens and while her family moved to London when she was a teen, when so she comes back to Birmingham as a nurse to run the clinic she falls back into the Shelby’s and her and Tommy finally get together so her parents are weary?

Word Count: 1869

I hope you like :)

CHARMED

“Sybill from down the street told me she saw you and Thomas Shelby earlier.”

(Y/N) choked on a mouthful of stew at her mother's words, fucking Sybill she thought, “Yes..he came by the clinic earlier so we were just catching up. I was close friends with his sister, Ada, remember?”

Her father heaved a large sigh, he had never liked the Shelby’s, it didn’t help that his only daughter was exceptionally close to Ada Shelby and therefore the rest of the family but he had a particular dislike for Tommy, not missing the looks and touches he shared with his daughter when they were teens, and despite the many times he had warned (Y/N) about not getting involved with their family, she ignored him like that stubborn teenager she was. He just couldn’t stomach the idea of his sweet daughter getting together with Tommy, so he went to the extreme and moved the family to London, lying to his daughter about getting a new and better job being the reason. They had only recently returned back to Birmingham, a year after the war had ended.

“Those Shelby’s are no good, you best stay away from them poppet.”

“He’s changed, dad. He works at his uncle Charlie’s yard with the horses, doesn’t do any of that gang stuff anymore.”

Her father scoffed in disbelief, “I doubt it. What could have convinced him to change?”

(Y/N)’s next words were quiet, “The war. Says after that, all he wants is peace and quiet.”

The room fell silent after that, wounds from the war still fresh. (Y/N) had lost uncles and cousins and her elder brother James, who stayed in London, lost a leg.

“Enough about that.” (Y/N)’s mother cleared her throat, breaking the silence of the room, “How was the clinic today?”

As (Y/N) talked to her mother about her day, her stomach was twisting in guilt about lying to them about Tommy. She didn’t want to but her parents were stubborn in their beliefs about his family, though she was surprised that it had taken this long for them to be seen together. She had been back in Small Heath for several months now and Tommy had bumped into her at the clinic on her second day there and since then, they had been sneaking around, their romance instantly blossoming the moment they reconnected.

(Y/N) stood under one of the bridges that ran along the cut, waiting for Tommy with her coat wrapped tightly around her to protect her from the cutting winds. The sound of gravel crunching brought her attention over to where Tommy was making his over to her, hands deep in his pockets.

“Tommy!” (Y/N) excitedly smiled, she hadn’t seen him for a few days, his work taking him out of Birmingham.

“Hello love.” Tommy pressed one of his hands to one of her cheeks before leaning down and kissing her on the lips. They continued kissing, gentle and unrushed until Tommy finally pulled away, a small smile on his lips,

“How’ve you been?”

(Y/N)’s smile falters, something that Tommy catches on to immediately,

“What? What’s wrong?”

“Someone saw us together before you left and told my mother…” (Y/N) spoke after a moment's hesitation. “And you know how much they hated us hanging out with each other when we were young so…”

Tommy raised an eyebrow “So?”

“I might have told a small fib” (Y/N) held her index finger and thumb close together, indicating how small of a lie but Tommy knew she was under selling it by the guilty expression on her face.

“(Y/N), what did ya say?”

“I may have said that you stopped with the gangster stuff and now just work with horses at the stables.” (Y/N) rushed out, embarrassed.

“You what?” Tommy couldn’t help but laugh.

“They were being mean Tom! And I couldn’t just sit there an-”

Tommy interrupted (Y/N)’s panicked rambles, his hands cupping her face, “Hey, don’t get upset eh. I’m not mad yea..”

“You’re not?”

Tommy wiped away the few tears that escaped her eyes before reaching down and tugging her hands into his,

“No, now c’mon. Lemme take you out on a date”

“But what about my parents?!”

“If they think I’m a stablehand then there’s nothing to worry about eh.”

(Y/N) was rendered speechless, allowing Tommy to tug her to the Garrison.

This time it was her father who brought up the topic of Tommy a few days later.

“One of the men from work said that his wife saw you with that Shelby boy a few days ago...says you were awfully close.”

(Y/N) didn’t have to look up from her plate to know the chastising looks her parents were giving her,

“What’s the problem? He does good work.” (Y/N) continued on with the lie, she felt guilty but she couldn’t stand the way they treated Tommy.

“We just don’t think he’s good for darling. I’m sure there’s better men than Tommy Shelby to date out there.” Her mother reached over to pat her hand in comfort.

(Y/N) huffed in frustration, slamming her fork down on the table, “Why don’t you believe me that he’s changed?!”

Her parents are stunned into silence by her outburst,

“Why don’t you meet him? And then you can see how he really is.” (Y/N) suggested, tired of arguing with her parents and they simply nodded in agreement with their daughter, knowing that it was the least they could do.

“What are you doing on Sunday?”

Tommy and (Y/N) were sat in the snug in the Garrison, John and Arthur were loudly playing cards the opposite of the table, allowing the two of them to speak in private.

“Nothing of importance, why?” Tommy lit up a cigarette.

“My parents want to invite you over for dinner. Want to get to know you and everything.”

“Do they still think I’m a stablehand?” Tommy snorted.

“Yea..”

“Orright, I’ll go to dinner.”

“You will?” (Y/N) looked at him in surprise.

“Yeah, how else am I supposed to convince them that this measly stablehand is the perfect man for their daughter?” Tommy threw (Y/N) a cocky smirk making her laugh.

A loud knock sounded on the door at 4 p.m sharp on Sunday evening. (Y/N) stood up before her parents could and quickly made her way to the door, she nervously ran her hands down her outfit before she opened the door and the sight that greeted her made her speechless.

Tommy was dressed down, instead of his usual three piece suit, he just had a wool jacket on top of a cotton shirt, along with some dress pants.

“Whad’ya think, do I look the part?” Tommy held his arms up to his sides, a grin on his face.

“I…. it’s very stablehand-ish. Come inside, I have no doubt that my parents rather talk before we sit for dinner.”

Tommy smiled at her again as he stepped in, pressing a kiss against her cheek before he let her lead the way. Her parents were standing in the living room, shoulders hunched, faces pinched and eyes hard.

“Mum, Dad, you remember Thomas don’t you?” (Y/N)’s voice was quiet.

“Hello, Mr and Mrs. (L/N). It’s a pleasure to meet you again after so long.” Tommy reached out his and shook their hands.

The room was bathed in silence, the atmosphere was tense and awkward, none of them willing the break the silence until (Y/N) suddenly jumped up from her seat.

“Mum, how about we make some tea?” (Y/N)’s mother didn’t even get a chance to open her mouth before (Y/N) was dragging her off to the kitchen.

As soon as they left, the frown on (Y/N)’s fathers face deepened almost immediately, “What do you want with my daughter?”

“I can assure you sir, I only have good intentions with your daughter. I only wish to hopefully marry her in the future.”

“How do I know she’s safe with you. We know what your family does.”

“Me and my brothers no longer do that, after the war we realized how precious life was and hated the idea of throwing our lives away with gang nonsense.” Tommy lied through his teeth, a charming smile painted on his face.

Tommy could see how (Y/N)’s father shoulders began to relax and his frown melt,

“(Y/N) mentioned you fought, what did you do son?”

(Y/N) and her mother walked in with a tray topped with a teapot and several cups before Tommy could answer,

“What are you talking about?” Her mother asked as she took her seat next to her husband, handing him a cup of tea as she did so.

“Tommy was just going to tell me about his experience during the war.”

There was a brief pause before Tommy spoke up, “ I was a tunneller. I also fought at Verdun, the Somme and Mons. I was the Sergeant Major of my unit as well.”

(Y/N) saw the surprised look on her father’s face, it melted into akin to pride,

“That is impressive, young man.” Her father sent Tommy a firm nod.

“Thank you sir.”

“Enough about the war eh.” (Y/N)’s mother changed the subject, she hated talking about it.

They switched the topic and spent the rest of the night chatting, only stopping over bites of food and before she knew it, (Y/N) was showing Tommy the door, it was late at night, Tommy staying for longer than planned, lost in conversation with her parents.

“I don’t know how you did it, but I’m pretty sure they love you.” (Y/N) grinned at Tommy who grinned back.

“I’ll never reveal my secrets.” Tommy kissed her, lingering for a bit before he left, telling her that he’d see her the next day.

(Y/N) skipped into the Garrison the next day, a wide smile on her face, one that grew when she slammed open the door to the snug and spotted Tommy. She squealed as she sat down, wrapping her arms around his neck,

“Oh they love you Tommy!”

Tommy pulled her into a hug, and pressed a kiss to her temple.

“Who loves Tommy?” John asked from across the room.

“My parents. He came over for dinner last night and charmed them.” (Y/N) turned and faced Tommy’s brothers.

“How’d he manage that? I thought your parents hated our family” Arthur spoke up next.

A blush appeared on (Y/N)’s cheeks, “I may have lied about Tommy leaving the gang life and told them that he now works in the stables…”

John and Arthur look at each other before bursting into laughter,

“What you gonna do when they find out you lied? It won’t take long for them to find out” John asked after a few minutes of laughing.

(Y/N) and Tommy look at each other before shrugging, “Guess we find out when it happens eh” Tommy huffed a laugh into his glass of whiskey and tucking (Y/N) under his arm.

#tommy shelby x reader#tommy shelby imagines#peaky blinders x reader#peaky blinders imagines#peaky blinders#peaky blinder imagine#peaky fookin blinders#tommy shelby#thomas shelby#thom#fanfic#imagines#cillian murphy#thomas shelby x reader#peaky blinder fanfic

406 notes

·

View notes

Audio

01 - Goin' Down Slow - James Cotton 02 - Jive Harp - Tim Whitest 03 - Birmingham Late Hours - Birmingham Junior & His Lover Boys 04 - Highway Blues - Little Daddy Walton 05 - Steppin' High - Little Luther 06 - You're Growing Old Baby - Model T. Slim 07 - You Better Believe It - Harmonica Slim 08 - Mary Helen - Harmonica Slim 09 - Aw Shucks Baby - Little Red Walter 10 - On The Sunny Side Of Love - Mr. Calhoun 11 - Somebody Voodooed The Hoodooman - Model T. Slim 12 - Wild Women - Danny Boy & His Blues Guitar 13 - Driveway Blues - Harmonica Fats 14 - She's So Good To Me - Little Sam Davis 15 - Stop Cheating On Me - Sir Arthur 16 - Bad Luck - Stormy Herman & His Midnight Rambles 17 - Sweet Pea - Sweet Pea Walker 18 - Well, You Know - Dusty Brown 19 - Mama Mama Talk To Your Daughter - Harmonica Fats 20 - Whole Lotta Woman - Mo-Jo Buford 21 - Goin Crazy - Pete Lewis 22 - My Baby Didn't Come Home - Harmonica Fats 23 - Du Dee Squat - Little Luther (Thomas) 24 - The Mix Up - Little Sonny & His Band 25 - Tore Up - Harmonica Fats 26 - Juicy Harmonica - George “Harmonica: Smith 27 - My Woman Didn't Come Home - Harmonica Fats 28 - Drop Anchor - Harmonica Slim 29 - Ron-De-View 36 - Little Boyd 30 - Take My Hand - Model T. Slim 31 - How Low Is Low - Harmonica Fats 32 - Inside My Heart - Little Sonny & His Band

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Honeysuckle’ (1876).

Block printed cotton designed by William Morris (1834 - 1896) for Morris & Co.

Made by Sir Thomas and Arthur Wardle Ltd.

Image and text information courtesy V&A.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2017. All Rights Reserved.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Serious Things: Chapter 2

While on the road to meet Capone, Arthur meets Mollie and finds that he has a connection with her. Tommy acts like a diva when he finds out that some things are beyond his control.

Arthur doesn’t get enough fic love, and I seek to change that.

Serious Things: Chapter 1

Cicadas were making an almighty racket, splitting Tommy’s head with a ferocity rivaled only by the thought of being trapped in Yemassee a second longer. Blinded by a sun that he was not accustomed to, frustrated by an isolation unfathomable to him before this trip, and horribly hungover, he snapped at the old man stood before him in oil-stained overalls and shite caked boots.

“Two days!” Tommy shouted his expression a picture of rage. He put his hands on his hips and fixed the mechanic with a glare that could freeze the demons out of hell.

“Yep, and gettin’ all het up ain’t gonna make it come any quicker.” The mechanic drawled, wiping his greasy hands on a shop rag. “I’d be happy to give ye a tire off my own truck, but it ain’t gonna fit that there Dusenburg. They gotta special order it, Mr. Shelby.”

Nino intervened, concerned that the congeniality of the old man would wear thin if Tommy continued to rant. “Thank you, sir. Please, make the necessary arrangements.” He handed the man a ten dollar bill and turned back to Tommy who was smoking furiously and flexing his jaw muscles in between drags.

“Tommy, look, I know you’re pissed off, but you can’t take it out on the locals. They all know the score; they’re used to seeing Capone’s associates come through their town, but we don’t need to go looking for attention.”

“How the fook did this happen, eh? The car was fine yesterday,” Tommy growled. Sweat had beaded out on his forehead and was soaking through the back of his waistcoat, and it was only 8:00 am. “Now we’re stuck in this godforsaken hole for two more days.” Tommy turned the nail that the mechanic had found in the tire over and over between his fingers. “I’ll bet Arthur had something to do with this. A nail in the tire is an old family trick.”

“Nah. I think Arthur’s been too busy to sabotage our progress. That Mollie really took a shine to him.”

***

Arthur woke up to the smell of hot coffee. He blinked, unsure of his surroundings in the light, but the memory of soft green eyes and tangled auburn hair shining in the dim glow of an oil lamp soon brought his location into focus. After spending some time getting to know each other, Molly had taken Arthur’s hand and led him to her two-room shack behind the cafe.

Her sheets smelled of her perfume, and Arthur stretched beneath them, trying to recall where he had left his pants. Just then, Mollie appeared in the doorway in a filmy white cotton gown, a mug of coffee in each hand. She stepped into a beam of sunlight as she entered the room, and Arthur hummed appreciatively as the gown became transparent and revealed the outline of her body. She flicked Arthur’s drawers up onto the bed with her foot, “Lookin’ for these?” She giggled.

“Nah. I thought I’d spend the day in me altogether,” he chuckled as he shimmied them on and gratefully took a piping hot mug from her hand.

Mollie leaned against the bedpost and sipped at her coffee, admiring Arthur’s sinewy body. He had skin as pale as milk with a scattering of cinnamon freckles. She licked her lips as she remembered the way his skin tasted. “We have cake for breakfast, ‘less you’d rather have eggs and bacon. I can slip into the kitchen of the cafe and grab some if you’d like.”

Arthur felt the outside world melt away when she spoke to him. He could listen to her low country drawl all day. “Cake will be perfect, dear.” Arthur cleared his throat and patted the narrow bed, prompting Mollie to sit down. “Mollie, I have to leave soon. Tommy is probably champing at the bit to go already.” He took her hand and cast his eyes down.

“I know,” she whispered, “and it’s alright.” Mollie reached up and caressed his cheek.

“I wish things were different. I’ve really liked my time with you...uh, and not just the relations.” He nodded toward the bed as he spoke.

“Me too, Arthur. You are a wonderful man. I wish you didn’t have to go so soon, but I understood what I was getting into when I,” She blushed and searched for the right word, “brought you here.”

“C’mere, love,” Arthur murmured and pulled her down into the bed. She lay her head on his chest, her hair fanning out over his pale, freckled skin. A single salty tear trickled across her cheek before falling to Arthur’s collarbone. She trailed her fingers through the pale thatch of hair on his chest and traced the lines of his tattoo, wishing that they could have one more night together.

“If things were different, I could get used to having you around.” He softly spoke, and he meant it. Arthur had been into snow and whores for so long that he had forgotten what it was like to make love with a woman who was there out of passion and tenderness of feeling, not just because she was paid to be there. Mollie was no angel, but she was with him because she wanted him; she was attracted to the sparkle in his eyes and charm in his smile. She had no expectations of him, financial or otherwise, and she made him feel things that he had never felt before. It was more than just sex; something magical had taken place.

One night of passion had done this to them. They had tumbled into her bed as soon as they reached her home, and when it was over, they had stayed up late into the night talking. Arthur told her about his family and explained his scars and tattoos, and she told him the story of how she had come to live in a little shack behind a cafe in Yemassee, South Carolina.

Her family moved around too much for her to bear. Most of the year they worked at fairs and carnivals throughout the south, and she longed for a settled life. Since her family had roots in Yemasee at one time, she figured it was as good a place as any. She got a job at the café, rented the little shack behind it, and that was that. After she told him her story, they held each other all through the night, neither wanting to let go. Everything felt easy, like they had known each other for years.

Afraid that she would fall to pieces if she laid there any longer, Mollie wiped her eyes and sat up. She gave Arthur a little smile over her shoulder, “I’ll get us some more coffee and a slice of hummingbird cake.” As she moved about in the kitchen, getting plates and forks, she heard frantic whispering coming from just outside the door.

“Mollie, Mollie Girl,” a voice hissed from behind a row of hackberry bushes.

“Who is that?” Arthur whispered to Mollie.

“It’s my next door neighbor’s daughter,” she told Arthur. She rolled her pretty green eyes and smiled. Mollie stepped out onto the porch and spoke to the bushes, “Come on out from there. What is it Pearl?”

“They’s a white man, named Mista Shelby. He’s mad mad. He say he’s lookin’ fo a Mista Arthur Shelby. You ain’t got him back here wi’chu, do you?”