#since canon used to be the cudgel they used to beat us

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I don't know if this is just my perception, but I've noticed that Krauser uses Ashley several times as a way to provoke Leon (especially during their final fight).

In their first encounter, immediately after Leon realizes it was Krauser who kidnapped Ashley, the camera focuses on his angry face and then on his hand about to grab his gun. As if the knowledge that it was Krauser who was to blame for Ashley's kidnapping was Leon's motivation to start fighting back.

Then there's that cinematic where Leon arrives just in time to see Krauser take Ashley away with nothing he can do to stop him. Krauser even walks slower and without bothering to turn to look at Leon, not even when he shouts Ashley's name. In Separate Ways, we see Krauser start running with Ashley in tow as soon as Leon can no longer see them.

After killing Salazar and using the elevator, if we use the rifle to get a closer look at the speedboat, Krauser turns to look at Leon, while Ashley is unconscious in the back seat, almost as if he is challenging him.

During their final fight, Krauser mocks Leon's concern for Ashley, and then tells him that he won't be able to save her, and that's when Leon explodes again.

Krauser taunts again when he tells Leon to hurry up or who knows what could happen to Ashley.

And near the end of the fight, Krauser tells Leon that if he needs motivation, he should think about Ashley.

I think Capcom's intention was to show how deeply Leon cares about Ashley through Krauser. That's why I can't take seriously people who say Leon only cares about Ashley because 'it's his job', it just doesn't fucking make sense, it's like they haven't played the damn game, or just decided to ignore all that.

there's a lot going on here, actually, and it goes deeper than just Ashley herself. Krauser absolutely dangles Ashley over Leon's head, don't get me wrong, because he knows that it's a source of angst and insecurity for him -- but it goes far deeper than just this one woman.

Krauser says at one point that he knows Leon's potential better than anyone -- he knows Leon better than anyone. and he may just be right.

in OG, Krauser asks Leon: "what is it that you fight for, comrade?" to which Leon responds: "my past, I suppose."

now, take that little snippet of a conversation and stretch it out over the course of four years of military training. it's likely that Krauser had to dig deep into Leon's psyche in order to motivate him to perform at his absolute best -- and what's at the center of everything for Leon is what happened in Raccoon City. Krauser likely knows every detail of what happened that night.

and what happened that night was that Leon failed to save the life of a single person.

so, since LeonA is canon in the Remake-verse, let's take a look at the list of people Leon failed to save in Raccoon City:

the cop in the gas station

Officer Elliott

Marvin Branaugh

Ben Bertolucci

Annette Birkin

Ada Wong

I don't know if you're keeping score, but that's... just about every person that Leon meets. the only exceptions to this are Kendo and his daughter (who Leon never attempted to save), Claire (who never needed saving), and...

Sherry, whom Leon then gets kidnapped and held hostage almost as soon as he volunteers to take sole custody of her.

so, when Krauser says to him: "you can't save anyone" he means anyone. the US government sent a man who's never been able to save anyone but himself on a mission alone to rescue the president's daughter. if anyone knew his history and his track record, he likely wouldn't have been the agent assigned to do this.

but the only person who knew it was Krauser, because Krauser's the only one who ever got close enough for Leon to tell. and since Krauser's now a traitor and a terrorist, he uses that knowledge as a cudgel to beat Leon with.

so -- yes, Krauser is purposefully using Ashley as a knife to twist in Leon's heart, and yes, saving her is more than "just doing my job" for him. it's extremely personal for him for many reasons. and as he starts to feel more and more affection for her, this need to save her becomes more and more intense, and it becomes easier and easier for Krauser to weaponize that against him.

and this is just storytelling 101. as the story goes on, the stakes have to rise higher and higher until they reach an absolute crescendo at the climax. and since Leon is so physically capable and very little in RE4make comes off as an actual threat to him, his stakes are mental and emotional in nature. as his feelings for Ashley intensify, so too does his anxiety about being able to save her.

the climax of RE4make's story is the walk to Luis's lab, and by then, Leon's feelings for Ashley have gotten so strong, and his need to save her has become so intense, that he sees her life alone as comparable to all of the people who died in front of him in Raccoon City.

if he can just save her, that would absolve him of his other failures.

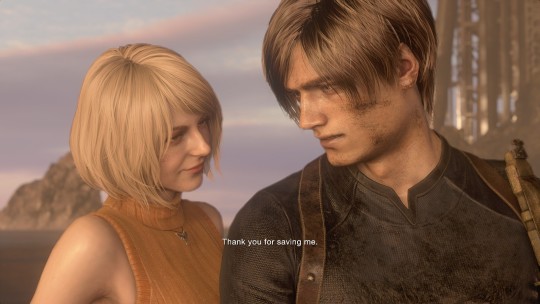

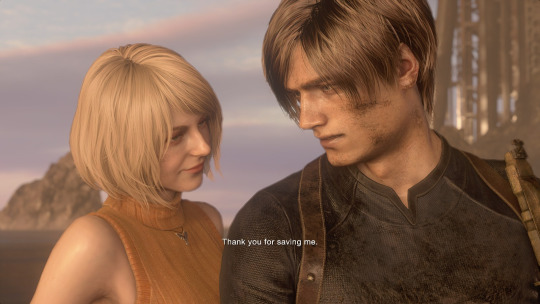

that's why the script was written so that Ashley says the actual words to him in the ending.

this is the culmination of Leon's several character arcs in the series so far; it's the payoff for his character development; it's the catharsis for the angst he brings into RE4make with him.

Leon was a man who couldn't save anyone, but he ends RE4make as a hero.

his 21-year-old self would be so proud.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Krauser dangles Ashley over Leon's head to taunt him

Krauser says at one point that he knows Leon's potential better than anyone -- he knows Leon better than anyone. and he may just be right.

in OG, Krauser asks Leon: "what is it that you fight for, comrade?" to which Leon responds: "my past, I suppose."

now, take that little snippet of a conversation and stretch it out over the course of four years of military training. it's likely that Krauser had to dig deep into Leon's psyche in order to motivate him to perform at his absolute best -- and what's at the center of everything for Leon is what happened in Raccoon City. Krauser likely knows every detail of what happened that night.

and what happened that night was that Leon failed to save the life of a single person.

so, since LeonA is canon in the Remake-verse, let's take a look at the list of people Leon failed to save in Raccoon City:

the cop in the gas station

Officer Elliott

Marvin Branaugh

Ben Bertolucci

Annette Birkin

Ada Wong

I don't know if you're keeping score, but that's... just about every person that Leon meets. the only exceptions to this are Kendo and his daughter (who Leon never attempted to save), Claire (who never needed saving), and...

Sherry, whom Leon then gets kidnapped and held hostage almost as soon as he volunteers to take sole custody of her.

so, when Krauser says to him: "you can't save anyone" he means anyone. the US government sent a man who's never been able to save anyone but himself on a mission alone to rescue the president's daughter. if anyone knew his history and his track record, he likely wouldn't have been the agent assigned to do this.

but the only person who knew it was Krauser, because Krauser's the only one who ever got close enough for Leon to tell. and since Krauser's now a traitor and a terrorist, he uses that knowledge as a cudgel to beat Leon with.

so -- yes, Krauser is purposefully using Ashley as a knife to twist in Leon's heart, and yes, saving her is more than "just doing my job" for him. it's extremely personal for him for many reasons. and as he starts to feel more and more affection for her, this need to save her becomes more and more intense, and it becomes easier and easier for Krauser to weaponize that against him.

and this is just storytelling 101. as the story goes on, the stakes have to rise higher and higher until they reach an absolute crescendo at the climax. and since Leon is so physically capable and very little in RE4make comes off as an actual threat to him, his stakes are mental and emotional in nature. as his feelings for Ashley intensify, so too does his anxiety about being able to save her.

the climax of RE4make's story is the walk to Luis's lab, and by then, Leon's feelings for Ashley have gotten so strong, and his need to save her has become so intense, that he sees her life alone as comparable to all of the people who died in front of him in Raccoon City.

if he can just save her, that would absolve him of his other failures.

that's why the script was written so that Ashley says the actual words to him in the ending.

this is the culmination of Leon's several character arcs in the series so far; it's the payoff for his character development; it's the catharsis for the angst he brings into RE4make with him.

Leon was a man who couldn't save anyone, but he ends RE4make as a hero.

his 21-year-old self would be so proud.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

i can’t handle f*nnr*y anymore even though they were my main otp right after tfa, i start thinking about people using the ship’s ‘purity’ as a bludgeon to hurt other shippers whenever i see art or gifsets. it became so associated with toxic fandom behavior for me that it went from my otp to notp and it has nothing to do with the ship itself. i didn’t even ship reylo right away after tlj, i just started following reylo blogs bc they were the only fans who were decent about finnrose, my new otp.

f/rey could have been a glorious multishipper haven but its own fans turned it into a toxic wasteland. I swear I do my best not to let anti nastiness bleed on my perception of the ship itself, but I’m THIS close to have a pavlovian response anytime I see f/rey content, when a good 80% of it is either aggressively gatekept or made with the badly concealed intent of proving it the “better” ship. Not to mention the rabid reylo hate even the most innocuous f/rey gifsets tend to foster in tags and comments. And almost nobody in their ranks calls this shit out! How the hell is this helping F/nn? How am I supposed to support a ship if I’m forbidden to interact? What about the F/nn fans who appreciate his canon storyline and canon romantic arc like you? I honestly don’t have the time or energy to check if OP hates me every time I see cute f/rey art.So I’m basically at a point where I have f/rey blacklisted and I reblog f/rey content only from a few trusted sources(like this one), who I know are wank-free and multishipper friendly (and who deserve nothing but respect and support for going against the tide).

#anon#asks#I have a huge petty side that wants nothing but gloat at this ship being the opposite of canon#since canon used to be the cudgel they used to beat us#...and I'm trying to rein it in#because I know it's shitty#but still#finnrey for ts#anti reylo bs#fanwank#anti discourse#ship wank

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toward a Critical Re-Evaluation of Homestuck, or: A Prayer for Andrew Hussie

(aka Off-the-Cuff Homestuck Thoughts #7)

This might be a manifesto.

Since the ending sequence of Homestuck in April 2017, and even well after the establishment of a canon aftermath for its main characters and the confirmation that there will be a further Epilogue, I've seen a sentiment among Homestuck bloggers and the Homestuck fandom that I find very frustrating, one that persists well into 2018.

The sentiment goes something like this:

"Homestuck is a meaningless work by a flippant, irreverent prankster (Andrew Hussie) who dropped his commitment to the story at the last second, and made fun of his fans for expecting there to be a meaningful ending. Furthermore, he continues to harm and belittle his fandom in the creation of Hiveswap, and only continues his work on Homestuck-related projects to exploit his audience."

Not only is this idea wrong, I find it disingenuous at best, malicious at worst, and actively detrimental to an understanding of Homestuck as a work. While it comes from an understandable frame of mind - the feeling of disappointment many of us felt at the end of Homestuck's pretty short and to-the-point Act 7 - it actively ignores the main reason *why* that ending came across as disappointing at first glance. Namely, it ignores the role serial storytelling - a necessity at that point in Homestuck's existence - played in creating misleading impressions of where the story was going among fans. Furthermore, it completely ignores how well the story arc of Act 6 Homestuck generally works when taken as a whole.

It demonstrates a very shallow understanding of Andrew Hussie as a storyteller, conflating his in-story persona with the actuality of a creator who demonstrates nothing but work ethic and commitment to his creation.

It ignores what actually happened with Hiveswap, which is that despite a frankly horrific set of circumstances that nearly prevented it from being made, Hussie was nonetheless able to gather a small team to create a game studio that delivered on every promise it ever made to Kickstarter backers and created a pretty solid, fun, and novel adventure game, with more installments and a rich evolving mystery on the way.

Finally, this interpretation completely misunderstands the way the idea of narrative is being used in the ending of Homestuck, not as a cudgel to beat off fan desire for thematic completion, but as a tool for delivering a thematically powerful narrative that draws parallels between the specter of Lord English and the way stories themselves are used as tools of oppression.

Homestuck isn't perfect, and neither is Andrew Hussie. But by and large, this popular perception of him is flat-out wrong, an exaggeration of whatever flaws he brought to the creation of Homestuck, and contributes to a misunderstanding of its ending. Indeed, I'd argue it is, in some ways, part of why Homestuck has rarely been acknowledged as a significant work of art. To understand why Homestuck is important, first we need to be able to acknowledge what it achieved.

Here's a daring notion: overall, Homestuck was and is pretty damn good.

Here are some reasons.

1) Being Forced To Tell the Story Serially Over a Slow Drip Messed With the Experience for the Reader

I can hear the bristling now. "I hated the ending," I can hear some of you saying. "It left me cold and unsatisfied, and damn it, that's an objective fact. Who are you to take that away from me?"

Actually, I'm not trying to take that away from you. Like, you're allowed to have been disappointed. I just want to point out that it might be a better ending than you gave it credit for, and explain why it came off the way it did. If you're interested in hearing me out, read on. You should know that initially, I was disappointed, too.

But after rereading Act 6 and the whole narrative leading up to that ending? I changed my mind. Rereading, I found it pretty satisfying, making a great deal of sense, capitalizing on major themes, and delivering a meaningful ending for most, if not all characters

I'll talk more about *what* I think the narrative is doing in a bit, but here's why I think it was misread, by me among many others.

Serial reading fucks with the quality of a story experience. I feel like this is a pretty uncontroversial statement. The problem with serial storytelling is that stories build on themselves, drawing on themes and ideas from earlier on to make a powerful build-up to moments of catharsis. This is the nature of story and character development. However if you're getting a story as little bits and pieces, it is much more difficult for this to happen. You lose track of these threads.

More dangerously, it's very easy to develop a set of expectations around a narrative while it's in pause mode. Little moments - intended to be part of a larger flow of ideas - completely dominate one's thinking for as long as they hold the stage. This is a common thing in fandom, especially webcomic fandoms, who deal with the slowest-drip narratives. Again and again I've seen expectations generated during webcomics' hiatuses lead fans to disappointment with the results, simply because those results have nothing to do with what was expected during one of those moments of downtime. El Goonish Shive, Sluggy Freelance, Gunnerkrigg Court - I've seen it in webcomic fandoms again and again, that the dashing of narrative expectations seemed like a betrayal of the story when read at a drip pace, but made perfect sense when viewed as a whole story.

This is not a problem Hussie was ever unaware of. Here’s an excellent discussion (among many) from one of his early Q&As that takes on the problem in detail:

The longer I do this the more I'm struck by how radical the difference is between the experiences of reading something archivally vs. serially, both for the reader, and the author if he's prone to sampling reactions frequently as I do. For the reader especially, I think the experience of day to day reading is so dramatically different, they might as well be reading a different story altogether.

The main difference is the amount of space between events the reader has, which can be filled with massive amounts of speculation, analysis, predictions, and something I guess you could call "opinion building", which can have both positive and negative effects. On the positive side, these readers become more closely engaged with the material than archival readers can be, zeroing in on details and insights which might be overlooked otherwise. On the negative side, I think that excess mental noise the space between pages allows can potentially be a bit suffocating, and put a strain on the experience the material was intended to deliver.

The archival reader always has the luxury of moving on to the next page, regardless of how he reacts to certain events, and thus can be more impassive about it. That internal cacophony isn't given time to build, and if there are reservations about a string of events, whether due to shocking revelations, or questions over the narrative merit of something, or really any form of dissatisfaction, all he has to do is keep clicking to see how it all fits together, and can make a more complete judgment with hindsight.

He goes on to discuss a specific example of how this played out for the readers:

The recent pages [the start of Horrorstuck] had me particularly conscious of the nature of serial delivery. [Eridan's betrayal] was rolled out over the course of a weekend, first with Feferi, then Kanaya. When Fereri dies, this registers as one extremely dramatic event. Cue the waiting, speculating, worrying and all that. When Kanaya dies a day or so later, it registers as a second dramatic event! Again the scrutiny begins which the space allows. Is this all too much? How do I feel about this narrative turn? Is this setting a trend for a bloodbath? Does that serve any purpose? The reader projects into the future, does a little unwitting fanfiction writing in his head, and may not like what he sees! All this activity becomes the basis for opinion building, which is sort of the emergence of an official position on matters, good or bad, which is only able to flourish in the slow-motion intake of the story. That official position can be a very stubborn thing, especially when it's negative, and seriously textures the way additional developments are regarded. It's really hard to shake a reader off an entrenched position on a matter, even when it was formed with an incomplete picture.

Reading the same events in the archive is quite different. Very little of that inner monologue takes shape. And while the events are still shocking, and the reader may raise his eyebrows a mile high, he then simply lowers them and keeps reading. In fact, because of the reading pace, I would suggest these two deaths actually register as only ONE DRAMATIC EVENT! One guy snaps and kills two characters. In the flow of straight-through reading especially, it is quite startling, tension-building, and can only serve to propel the reader into further pages, at a pace which suspends the experience-compromising (augmenting??) play-by-play.

Hussie would return to this topic again and again, including here and here and here and h8re.

This is in incredibly valuable insight for anyone who creates stories over the long term, especially webcomics. You may or may not agree that Homestuck's finale is well-executed, but I think it's hard to escape the fact that the response to Homestuck's ending, indeed, to most of Act 6, was hugely influenced by these factors. Why? Because the experience of Act 6 and 7 was more affected by hiatuses and the speculation problems they create than any other part of Homestuck.

It's hard to remember these days, but one thing that Homestuck was known for from about 2010-2013 was its absolutely preposterous rate of updates. I'm pretty sure that *was* the initial fuel for the fire that made Homestuck a huge fandom. What other website could you go to see a huge chunk of a story drop on you so regularly? No other webcomic had people using Update Checkers, programs designed to check the RSS feed of Homestuck and tell you within the minute that it had updated so you could check it out before your friends spoiled everything to you. What other webcomic ever needed such a thing? But the first era of Homestuck fandom was predicated on the idea that the comic would update every couple of days, sometimes once a day, sometimes *multiple times in the same day*. No wonder it got so huge so fast. It was an experience unlike almost anything else out there.

Around 2013 this began to change. Homestuck began having large hiatuses, the famous "pauses," and though Hussie indicated the story was working its way towards the finale, it ultimately took until the 2016 anniversary to complete.

Interestingly, it's around 2013 or so that we started seeing frustration with Homestuck break out into a large phenomenon, with many people arguing that the comic had stopped being good, and it's after the largest of these pauses, the Omegapause before the end of Act 6 and Act 7 updates, that we had the famous ending backlash.

The fact that very few people seem to have considered this in their analysis of whether Homestuck is good or not is absolutely staggering to me.

Given these factors, we would expect to see some of the enthusiasm taken out of the Homestuck fandoms during these periods, and strong opinions on where the story should go next, and, lo and behold, that's exactly what we see. The common sentiment is that Homestuck "stopped being fun during Act 6." Well, yeah, it's a lot less fun to have a comic that updates rarely than a comic that updates with loads of content very, very often. That doesn't necessarily mean the content got worse. And yet I see no one asking if this altered our perception of the story.

2) Serial Reading Problems Are Worsened In an Experimental, Twisty Story

This hiatus problem was exacerbated by the nature of Hussie's storytelling. I'd describe his writing style as "affectionate teasing": testing and pushing readers' boundaries, aiming for strong emotional reactions, constantly working to defy and mess with expectations, but ultimately working towards a rich character-based story. Hussie's work whiplashes between humor, horror, worldbuilding, action - it's intense and disconcerting at first, but once you get familiar with it, you see these that all these elements build toward a coherent whole.

I'd argue that this storytelling style is *uniquely* well-suited to long-form reading and endangered by drip-feed reading.

Because when you read piece by piece, you experience whiplash slowly, and that’s not everybody’s kink. Pieces that are meant to work together take on a different tone when read on their own. As discussed above, continuous events seem like separate events when read on their own, and this creates a *false* expectation of where the narrative is going. Furthermore, it's not as much fun to be teased or messed with in slow motion. The expectation that there will be satisfaction and resolution disappears when the current update is all you can think about. This, not a deficit in storytelling, is what created the feeling of "Homestuck’s not fun anymore." But it was the same affectionate, gently teasing storytelling as ever. But this only comes out when the work is re-read.

This is exactly what happened in Act 6 Homestuck. Events seemed like they would go on forever, when in real story terms, they went on for moments. Take the notorious Trickster "arc" (I can't even call it an arc - it’s more of a sequence if anything). Today it's remembered as an unendurable gauntlet of Hussie pushing buttons. The reality of it is, though, if you read through it, it's like Hussie pushing buttons for all of five minutes, like half a chapter from a novel. Literally all it is is: The Gang Gets High on Magic Candy > They Do Stupid Things > Blackout. Mostly it's an excuse for some serious character development *afterward* as the Alphas discuss the bad decisions that led them to this place. It may or not be perfect, but it's definitely a lot more reasonable when you see it's a quick tangent.

Act 6 is full of things like this: events remembered as horrible slogs that are really quite brief in retrospect.

This is brought home when you consider that events in Act 5 – hell, even Acts 3 and 4 – also brought on strong negative responses from the fandom - it's just that they were quickly buried under a story that was quickly moving on to other things. Here are some strong fan outrages from those days I can name off the top of my head:

--This interlude with the trolls is too long, nobody cares about the trolls, Hussie has abandoned the human kids --Nobody cares about troll romance, switch back to the kids --Jade hasn’t been seen onscreen for ages --Vriska’s creation of Bec Noir shows that she is too powerful a character, she will never face comeuppance --John is dead again and Vriska killed him??? --Killing Feferi, Tavros and Kanaya? That’s too many deaths --I thought Feferi was supposed to unite the troll races! You’re telling me that’s not going to happen? --Kanaya is dead??? Fuck that --Scratching the timeline? What, Hussie, you’re going to reset everything and ruin the story? --Equius should have gone out with more dignity, this is a betrayal of his fans --Nepeta shouldn’t have been murdered, this is a betrayal of her fans --Gamzee used to be cute, now he’s a murder machine, this is a betrayal of his fans --We never found out what happened between Gamzee and Karkat? Why won’t the narrative switch back and tell us? --Nobody cares about Doc Scratch --Nobody cares about these stupid Ancestors, switch back to the trolls --Vriska is DEAD? This is a betrayal of her fans

And so on. Reading Hussie’s old Formspring archives is a graduate class in this era of Homestuck fan frustration.

And yet today Act 5 is universally remembered as brilliant, thought of by many as “the time when Homestuck was great.” In my book, while Act 6 does take on different themes than Act 5 (focusing more on the protagonists’ psychology and failures), and thus may not be to everyone’s taste, the biggest difference between the two is that during Act 5, the twists and turns of the story were thought of as part of a unified whole, because the story was barreling along too fast for these complaints to stick around for long.

Given that Hussie has always been aware of the challenges of serial vs archival storytelling, I feel like the relentless output of the first five acts was in part an attempt to mitigate those problems. As if by shoveling content into the mouth of the behemoth, he could propitiate the ravenous fandom horrorterror and thereby stave off the descent of the Infernal Internet Speculation-Expectation Monster that was prophesized to devour all.

Unfortunately, he couldn’t stave it off forever, and lo, in 2013 did the IISEM descend with its glistening tentacle teeth, IA, IA, IA! CHOMP CHOMP.

It astonishes me that in some quarters folks talk about the 2013-2016 pauses as if they were something Hussie wanted, when by all evidence he tried desperately to avoid them up until that point. I don’t need to explain that these hiatuses had to do with restarting the whole process of creating Hiveswap and building a game studio from scratch, right? I don’t need to explain that he got screwed over and these were circumstances outside his control, right? Let’s assume we’re on the same page there. If not, I suggest you look into the matter before assuming these hiatuses had anything to do with creator apathy.

After a certain point, Hussie faced a difficult choice. Unable to keep up the rapid-pace storytelling, he could change the storytelling to make it suit a serial reader, or he could focus on making the story the best it could be for an archive reader.

I think he went for the better option: aiming for the archive reader. If you’re going to argue that he should have put the emphasis on the serial reader: which serial reader are we talking about here? The one who started following in Homestuck in 2010, like me? The one who started after Horrorstuck, and viewed it, but not the end of Act 5, as a complete whole? The one who joined during late Act 6? How the hell would you decide that? Whose experience is the one to privilege?

The only option that really makes sense is to aim for the version of the story that will be around the longest and experienced by the most people: the archive that is the complete story of Homestuck.

Ultimately, I don’t think he could have changed his style of storytelling anyway, and to do so would have been to lose the combination of humor, madness, and surprises that brought us all to Homestuck in the first place. Forced to reckon with a difficult situation, he focused on making his kind of story the best that it could be, and I think Homestuck is better for it.

Given his awareness of the problem as expressed above, I’m sure Hussie knew proceeding over the long term would stoke a lot of resentment in the fandom. But he went ahead and did it anyway, because his goal was not to live up to a certain set of expectations. His goal was to tell what he saw as the best possible version of the story. I have an immense respect for him for that.

3) The Last Pause is the Deepest (or: Omegapause Killed the Character Development Star)

The final hiatus problem I want to point to is that in terms of the narrative arc of Homestuck, the final pause, the Omegapause, came at the most inopportune time for readers to get a sense of the conclusion of that narrative.

Basically, many character arcs in Homestuck were concluded *before* Collide and Act 7. Before the Omegapause. Indeed, Hussie brought many long-running arcs to an end in a very satisfying way during the “conversation” sequence before the final fight, from Dave’s long-needed conversation with Dirk about Bro to Rose’s finally getting to meet and befriend Roxy, to Game Over!Terezi and (Vriska’s) reunion. In narrative terms, Collide was not the climax, even if it might have been perceived to be. The climax was the Retcon sequence preceding the conversations – the desolation of Game Over, our surviving protagonists’ despair, then victory in the form of negotiating with the Denizens, representatives of Skaia, to create a timeline in which victory may take place, both in game terms and emotional terms. The conversation before the final battle showed us an emotional victory – victory in game terms was really just icing on the cake, or an echo of that emotional victory.

The trouble is, having a long pause before the final battle sequences created the false perception that the conversation was merely the prelude to the climax: that, in fact, the climax had not yet taken place. For us serial readers, it was easy to conclude that there was further character development to come.

Well, in some ways there was, and in some ways there wasn’t. Dirk and Dave got to have another big moment in Collide that drove their themes home, while Rose and Roxy had basically already done their thing earlier and just got to fight alongside each other. Meanwhile Vriska and Caliborn’s arcs really culminated in Act 7, and some, like John’s and Ret-Terezi’s, were complicated and continued by the Credits aftermath and probably won’t be brought to a final end until the Epilogue. There’s a degree of variation, which I enjoy. Collide does serve some functions: characters who were at an emotional distance from each other (for instance Jane and Jake), got to fight alongside each other and start building back their friendships. Overall, though, the bulk of emotional entanglements got resolved in that conversation, making the Retcon the load-bearing piece of Homestuck’s climax.

This is why the Omegapause was the most dangerous pause: because it built up an expectation that things would further develop from there with new entanglements and complications, instead of aiming towards a tying-off of plot elements into a conclusion.

I remember what *I thought* the post-Omegapause sequence was going to be: a showdown between the kids and Lord English as he entered the game session through Bec Noir, Spades Slick and Lord Jack. I expected there would be a twist, and I expected one or more of our protagonists would die. I was thrown for a loop when I realized the story had basically been almost over, with no last twist, no “secret final battle” of kids vs LE in sight.

But as I reread the ending of Act 6, I realized: that would have been so much stupider than what actually happened. The fact that the kids don’t directly face LE and Vriska does is one of the most brilliant parts of the ending, and on the reread I rapidly fell in love with the Homestuck’s conclusion. What had thrown me off was the fact that I developed my expectations during a period where it looked like we were further from the end.

But in retrospect, Hussie had been saying all along that we were very close to the conclusion – it was just, at that moment, very easy to get the wrong impression.

Rarely do I see anyone taking anything like this into account.

I do think we could have benefited from more character development after the pause, if for no other reason than to overcome these problems and make the victory feel a little more grounded, and I do feel like certain characters (Jane comes to mind) got more limited and abbreviated endings. But these are minor points for me in the overall arc of Homestuck’s narrative, which in my experience establishes its conclusion very, very well.

4) Homestuck’s Ending Is a Glorious Queer Gnostic Account of Escaping from Narrative Oppression (and Yes, Virginia, it Has Character Arcs)

Okay, so I’ve written a lot about *what* I love about the ending of Homestuck elsewhere, going on for pages and pages, which you can read here and here. For now, let me just attempt (as absurd as it is) a quick summary.

Homestuck in Act 6 parallels many different motifs to drive home the idea that escaping from Lord English’s domain is an escape from a cosmic oppression, and serves as a metaphor for escaping and defying real-life oppressions and hegemonies. These motifs include Gnosticsm, queer identity, pluralism, and a metafictional examination of the controlling role of the narrative that is Homestuck itself.

Gnosticism is an ancient early alternate version of Christianity that posits a false reality created by a false creator, the Demiurge Yaldabaoth, who rules over human beings but whose domain it is the Gnostic’s quest to escape. The Demiurge styles himself a Lord God (often the very same one from Judaism and more mainstream Christianity) and an artist but is in fact incompetent and limited in comparison with the true harmonious reality. That he was able to create such a false world was a cosmic accident caused by angel-like beings known as Aeons, who existed perfect symmetrical pairs until an asymmetry caused Yaldabaoth’s creation. Sophia, the asymmetrical Aeon is our path back to that perfection. Furthermore, the false world is the world of flesh and matter and material things, while the true world is the world of ideas, symbols and archetypes, a place of divine Platonic form. By knowledge (gnosis) we become our true selves and are set free. Gnosticism is anti-authoritarian, anti-patriarchal, and devoted to each human being’s quest to connect to the divine on their own terms.

Gnostic motifs proliferate everywhere in Homestuck, especially Act 6, from such chat handles as GardenGnostic, TimaeusTestified, and TipsyGnostalgic to basically everything about Calliope and Caliborn, including and especially their role in the finale. Act 7 depicts Caliborn as trapped within the realm he is created, destined for power but ultimately doomed to it, destroyed in the perfect moment where Calliope, his counterpart, brings his domain to an end.

Caliborn’s realm is the sequence of time loops and set of worlds that brought Lord English into being, but it’s also the narrative Homestuck that depicts those events and worlds. He complains about the narrative Homestuck, argues with its author, and tries to make his own version, just as a demiurge would. (Secretly, because of his cosmic influence, he’s more of an influence than he realizes. He places limits and boundaries on these worlds in the form of the narratives he perpetuates, and is obsessed with sexist ideas, exploitation, and themes of masculinity, importance and power. That the heroes escape this realm in which he has control is also them escaping these narratives that have been placed upon them.

This is the sense in which Dave says “we don’t have arcs.” As I’ve said elsewhere, it’s not Hussie rejecting the idea of giving his characters meaningful stories (this is largely a false impression generated by the Omegapause weirdness), as shown by the fact that Dave himself has one of the best, strongest arcs in the whole story. What Dave means, and what Dave’s arc is about, is that he had to let go of the false ideas, false narratives placed on him by the world (Lord English’s world, the Demiurge’s world) in which he lived. He did this by understanding the abuse he suffered from Bro (a Caliborn-esque figure) was wrong, and by overcoming his internalized homophobia to realize the value of the relationship he’d found with Karkat.

This is a frequent motif in the final pages of Homestuck. Queerness is represented as a way of escaping the patriarchal, conservative God of the Demiurge, and that these revelations about Dave appear in parallel with the final departure from the domain Caliborn controls is no coincidence. Queer relationships and identities build in the ending of Homestuck into what Hussie tongue-in-cheek called “the gay singularity.” This growth in queerness is represented as growth toward meaning, and further queer figures like the non-binary Davepeta appear as idealistic mentors to teach our heroes to understand their cosmic circumstances.

At the same time, the growth from a material world to a world of ideas is represented as the heroes taking on God Tier identities that embody aspects—ideas that are literally the building blocks of the universe. To know yourself as an aspect is to know who you are, and by knowing who you are, you become an idea that is divine. This all takes place at the same time characters grow towards queerness. To know your own queer identity is also to become divine.

And, at the same time, the characters leave the narrative. Everything that was Caliborn’s – his worlds, his time loops and influence— is left behind by the characters as they move into the realm where they are heroes, leaders, and gods. They pass through a door that resembles the weapon that he used, that is his narrative, the weapon shaped like the symbol of Homestuck, the weapon that *is* the narrative Homestuck. It is a weapon against him because he stays behind, on the other side of the door. Lord English can never leave. He’s in the dark pocket of the black hole forever. Caliborn enters a realm that appears to give him power—but he never comes out. He’s trapped by his own limited idea of who he is and what the world should be.

This is a fantastic, culturally resonant, and very Gnostic ending.

And as to Vriska—I’ve seen many people say that Vriska’s retconned revival gives her too much power and agency, but I actually think it strikes the perfect balance. The story understands what she wants. But it’s not on her side. I have a lot more to say about her (perhaps l8r), but here’s the most important thing: Vriska can’t leave, either. She gets what she wants: the ultimate fulfilment of her identity as The Hero. She gets to Kill the Bad Guy. But at a cost she is incapable of recognizing. Like Caliborn, she never gets to go on to be a fulfilled, happy patron of the new universe. She is always on the inside of the door, stuck inside Homestuck. And the fact that we’re asked to observe her breaking off her relationship with Terezi to go out in a blaze of glory? The fact that we’re asked to compare her to another version of herself who’s let go of her ego, whose bond with Terezi is the most important thing in her life? The fact, that in her eyes, she comes up better, but in ours, she comes up short? How incredible is that?

Neither the Hero or the Villain, trapped in their own ideas, trapped by their own ideas, can ever be free.

It’s a pretty good ending, is what I’m saying.

5) Against Apathetic Lazy Troll Hussie

So, back to that perception of Hussie I discussed earlier. The idea that he’s a flippant, irreverent prankster who never cared about bringing his story to a good conclusion.

By now it should be clear why I don’t really buy that line of thinking. The sheer effort put into Homestuck after the pauses began, the level of thematic complexity Homestuck was going for at the end—these belie the idea that he was apathetic or lazy or wanted to piss off his fans. What seems obvious to me was that he was committed. He devoted himself to driving towards an end he was personally satisfied with, whatever anyone else thought of it, and chose to accept the consequences of having to tell it over the long term.

I could see how it might be easy to get the impression that Hussie’s a very frivolous, thoughtless guy, when his in-story self is a ridiculous, flighty orange goofball. But come on. That’s mistaking the persona he uses for comedy with his actual self as a writer. Reading any interview, Q&A session, or discussion with him reveals how much thought he put into every moment of Homestuck, and above all, that he was committed to putting an incredible amount of effort into it from the very beginning.

He was also committed to challenging himself and bettering his work, whether that meant trying new experiments (flash games, new animation styles, splitting panels and dialogue, messing with formatting, letting the villains take over the website, etc., etc., etc…) or rethinking his work to take account of a larger, more diverse perspective, as we saw with the developing queerness and introspection of characters like Dave.

Yet he knew that not all experiments would be received well. He chose to accept that, to not wallow in the familiar but to take on new things regardless of in-the-moment reader reactions. As he put it:

I guess I just believe in sticking to your guns as a creator. It doesn't mean you completely ignore what people have to say or fail to take it under advisement, but pandering and caving into critics for fear of diminished appreciation is the wrong way to go. Staying the course with your vision doesn't mean you'll do everything right, but if included in that vision is serious, concerted exploration, you can only benefit as an artist. Adversaries to this cause should be regarded as villains.

There are two ways to do the "obstinate douche bag" thing as an artist.

One is in vehement defense of stagnation. Some artists I've encountered do this, and it's completely indefensible. It's as low as you can get, creatively speaking.

The other is in vehement defense of exploration. This is just the opposite. This is a posture everyone should strive for, and these artists are the ones people should be most inclined to offer their attention and support.

That's just how I feel about it, and I come from a zero-BS standpoint on it all. This isn't a job for me, and I'll never modify my approach to protect a bottom line. If it was just a job, I guarantee I wouldn't spend every waking hour doing it. It's kind of a strange personal mission I'm on, which I happen to make money from, and that's cool. People are welcome to come along for the ride.

There’s a deep, deep irony to me in the fact that some talk about Act 6 Homestuck like it was a stagnant period in Homestuck’s development, when in fact, it was one of its most creative and experimental periods. This is true both of its structural and visual experiments, where messing with form finally revealed itself to be central to Homestuck’s major themes, and of its storytelling experiments. It’s understandable that diving into the kids’ psychological problems was a shift, and not everyone was down with it, but the very fact it was a shift shows that Hussie was trying new things. It would have been easy for him to stay in a comfortable place doing the same things he did in Act 4 and 5, but instead, he began to ask different questions and take the story someplace new. And honestly? Act 6 took a long time to pay its full dividends, but I loved where we ended up in the end.

(What kept us from enjoying it in the moment? The pauses. Once again the pauses.)

But for me, the thing that most puts the lie to the idea of Lazy Hussie is the sheer fact of Act 6’s existence itself.

Consider how easy it would have been to drop Homestuck completely when things got rough in the middle years. Consider how many webcomic authors would have done just that. I can name many webcomic hiatuses where the webcomic never came back.

But Homestuck did. Not only did it return, it returned spectacularly, scorchingly, with the shocking and dynamic Game Over, with Caliborn’s claymations, with two spectacular, full-length animations, one of them lovingly-hand drawn. It returned with metafictional shenanigans and glorious queer Gnostic themes. Hussie kept going, and kept experimenting all along the way.

This is the furthest thing in the world from laziness.

And the same is true for Hiveswap. It astonishes me how much I’ve heard Hiveswap talked about as a debacle or a betrayal of its fans. Despite having horrible problems dropped on him, the sort that would ruin any other Kickstarter, Hussie spent the next few years working to make sure he met the promises he’d made to his fans. He did.

My dudes, Hiveswap is real. It exists. It delivers on every promise that was made about what it might be: it’s a fun, pretty, point-and-click adventure game telling a new story in the world of Homestuck. It’s creative and clever and updates an old style of gameplay by letting you put things on things to your heart’s content. It’s certainly more accessible than Homestuck, and not yet as structurally complex, but given future installments, there’s plenty of time for it to grow into something rich and thorny. And rather than see this idea go under, from basically nowhere Hussie worked to bring together a small, diverse team of queer artists and creators to make this thing happen.

Again, not exactly laziness.

That’s why it angers me when I see people calling Hiveswap (somehow?) a betrayal of Homestuck fans, or advocating pirating Hiveswap or demanding their money back because it doesn’t live up to some weird set of expectations they placed on it. Maybe during the periods of drought and ambiguous release dates, both for Homestuck and Hiveswap, it made a little sense to be skeptical of Hussie making promises, but now?

It’s basically spitting in the face of a creator who kept working in the most difficult circumstances, and the small, insanely hard-working team who made it possible, over something that they’ve handed to you exactly as you specified right on your doorstep in a gift-wrapped box.

I’m not saying you can’t critique Hussie or his storytelling. He’s definitely a weird dude with a lot of quirks (Which is perhaps the only kind of dude who could have made something as quirky as Homestuck.) I think it’s fair to say he hasn’t always communicated well with the fandom. But the reaction to him these days is totally, ludicrously, out of proportion, beyond anything that would be a useful critique.

A related question is whether Andrew Hussie is burnt out on Homestuck.

Well, maybe?

It’s certainly true that since 2013ish he’s stepped away somewhat from communicating directly with his fans. But 2013 is also the time when Homestuck fandom was at its most massive, its most full of infighting and meaningless arguments, and its most overwhelming to keep up with. I’m not saying I wouldn’t like to hear more of his insights, but it’s pretty understandable that he wanted to step back a bit under the circumstances. That doesn’t necessarily mean he’s burnt out. I mean, he seems to be living his best life, posing glamorously with his fidget spinners and Minion t-shirts. Not exactly hiding in a cave. Rock on, dude.

If he is burnt out on Homestuck, though, that makes what he’s done with Homestuck and Hiveswap all the more impressive. That he brought them this far, and wants to see them keep going and keep doing well, when he could have let them drop unceremoniously a long time ago. If he’s delegating some of the work to others, all the better. I can think of nothing better for an artist who’s burnt out and ready to move on than to find people he can trust to keep the things he started going into the future, and that, I think is exactly what we have in What Pumpkin, Viz, and Homestuck’s artistic team.

But even to assume that he’s burnt out is to presume a lot about his mental state from some very scant data. By many other indications, he wants to keep engaging with Homestuck. There’s an Epilogue to come—a capstone for those last few ambiguities surrounding the timeline, John and Terezi. And he’s getting the Homestuck books re-published with new commentary through Viz—so maybe that’s where he wants to have his conversations with his audience. And he’s still the creative director of Hiveswap itself. It’s very possible he’s not burned out—if anything, wants to keep building the world he created in Homestuck and seeing where he can take it next.

Ultimately, I think people’s ideas about Andrew Hussie say a lot more about their lingering feelings about the ending of Homestuck—a backlash brought on by the pauses he had to work with—than anything about Hussie himself.

6) The Conversation Around Homestuck

Homestuck is a goddamn triumph.

There are certainly critiques I could make of it. But they pale in light of what Homestuck is: is one of the most rich, genre-bending, experimental, character-driven, hilarious, innovative, metafictional, transcendent, optimistic works on the Internet—to say nothing of how it dwarfs much of the rest of literature.

Ultimately, I think Hussie was right: as an archive, as the story it is from beginning to end, Homestuck stands. It’s a rich, meaningful work with a meaningful finale, and it’s right there to be read by anyone who wants to read it. In that sense, Homestuck was and Homestuck is. It doesn’t really need me to defend it. Nor does Andrew Hussie.

So why did I write all this? Why did I write everything I’ve written here on this blog?

Well, mostly for Homestuck’s readers. For fans like myself.

Because I still see people who came away from Homestuck feeling totally burned and abandoned by its creator, when that was anything but the truth. Because I still see people who feel like they can’t escape an awful negativity about this comic, about the ending of something they passionately loved. I want them to see that it doesn’t have to feel that way.

And because I want Homestuck criticism to be better. Because I see prominent bloggers, some of whom I really respect, taking so little of this stuff into account. I want to see people talk about Homestuck’s place in literature, in internet culture, without discounting how circumstances shaped how it was perceived. I want to get away from a lazy cynicism—that cynicism everywhere online—about whether stories can be meaningful at all. A cynicism that Homestuck is the very antithesis of through its themes of transcendence and hope.

I think for some people, Homestuck is that weird old obsession they cringe at. The ghost of teenage fandoms past. Which is fine. It’s reasonable to want to move on. But it frustrates me when I see the same cynical, cringing attitude affecting how people feel—or feel like they’re allowed to feel without social stigma—about the work Homestuck itself. I’m not interested in cringe culture.

I frankly don’t have time for it when Homestuck’s as good as it is.

Don’t get me wrong, I want Homestuck to be criticized, too. I want to hear what its flaws are. I think that’s also an important part of the conversation. But don’t tell me it’s a pointless, apathetic work, that it’s just the product of laziness. Because we know better than that by now. Because we need a better conversation than that. Don’t tell me that Homestuck doesn’t have Gnostic themes. Tell me how it uses them, and how it could use them better. Don’t tell me Homestuck’s meaningless. Tell me how it strives to be meaningful—because it does, in every aspect of its storytelling—and tell me where it succeeds, and where it fails.

That’s the kind of conversation I want to have about Homestuck.

You may not agree with the things I’ve pointed to here—you may think that Homestuck’s ending is much more flawed than I do. But that’s totally fair. All I want to say is this:

If you were holding off from letting yourself enjoy Homestuck, or if you once enjoyed it and wish you could enjoy it again, or if the experience of the ending left you feeling disappointed and frustrated and burned out…

Give it another read, especially Act 6 and 7.

You might be surprised how much you like what you find.

#homestuck#homestuck ending#homestuck analysis#homestuck criticism#andrew hussie#off-the-cuff homestuck thoughts extravaganza 2017#now in 2018#in defense of homestuck#homestuck fandom#understanding homestuck#ending themes#understanding the ending#serial vs archival reading#homestuck is good actually#against lazy cynicsm#towards a better conversation#keep rising

593 notes

·

View notes

Text

POST-MODERNISM IS A SELF-SERVING ICONOCLASM WHOSE END-GAME IS DEATH BY OBSOLESCENCE

Why has post-modernism taken hold so successfully, where did it come from and why does it continue to spread - despite the push-back and the warnings - a culture of mediocrity and reductive relativism that’s threatening to pervert centuries of Western thought and culture?

"We are absurdly accustomed to the miracle of a few written signs being able to contain immortal imagery, involutions of thought, new worlds with live people, speaking, weeping, laughing. We take it for granted so simply that in a sense, by the very act of brutish routine acceptance, we undo the work of the ages, the history of the gradual elaboration of poetical description and construction, from the treeman to Browning, from the caveman to Keats. What if we awake one day, all of us, and find ourselves utterly unable to read? I wish you to gasp not only at what you read but at the miracle of its being readable." -- Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire (1962)

The seeds of what’s become the global post modernist juggernaut were sewn in an unusual way for a cultural movement. It is rooted in a rejection of truth and an antipathy towards individual genius. It's has evolved into much more than just an academic school of Western thought. Today it has conflated itself through media (social media included) with a perverted democratisation of excellence that’s taken hold of vast swathes of “respectable” society and culture. In recent years the degraded redefinition of excellence has spread like a disease to erode truth and fact, disdaining expertise by somehow reducing it to an abusive power dynamic. This is a disastrous choice for us to be making as a society and if the trend isn’t reversed, we’re going to bankrupt Western thought and culture without hope of reprieve. This bankruptcy ends only one way: in our inevitable obsolescence, as the torch passes East and the West cannibalises itself on a banal descent into permanent irrelevance.

From its innocuous roots in late 1940s post-modernism has spread like a steady but relentless virus. It has become a formalised absolution from personal challenge, mobilising a kind of anti-ambition that’s kept virulent by successive generations of mediocre academics motivated by a seemingly bottomless well of intellectual vanity and tenured self-interest.

"Great spirits have always encountered the most violent opposition from mediocre minds." -- Albert Einstein (1879-1955)

A hundred individuals aspiring to creative genius will mostly fall short of the standard and most will have the intelligence to see the shortcomings are their own, be it cowardice or fear or insurmountable absence of virtuousity. How can intelligent academcs used to success reconcile falling short of genius they themselves worship more than any other human characteristic? Post-modernism has become the answer. It is the means to an end and it has served successive generations of post-war career academics - and their students. Just as the Nazis had bastardised Nietzsche to justify Aryan eugenics, the early post-modernists corrupted Heidegger’s rollback of temporal ontology (as the defining way to think about the world) to legitimise a rejection of the significance of all individual human beings in the creative process. The poison had entered the veins of post-war culture.

POST-MODERNISM AS A SICKNESS

In the years after the second world war, across societies in great flux with a demobilised but changed citizen spirit, post modernism was not at first a pervasive dogma. It was a convergence of genuinely blue sky sociology studying conditions in the immediate aftermath of war with philosophy chasing meaning in a mechanised relativistic universe. Philosophy and sociology might have kept themselves uncorrupted were it not for the arts - far more numerous and influential in an everyday sense - having been caught between a Joycean rock and a Woolfish hard place. Vladimir Nabokov, most famous emigre after Einstein, warned us what was going to happen in his greatest work, Pale Fire.

"Reality is neither the subject nor the object of true art which creates its own special reality having nothing to do with the average "reality" perceived by the communal eye." -- Nabokov, Pale Fire (1962)

Career academics, their fragile conceits needing a system of protection against the genius of modernism, were driven to post-modernist ideas which they quickly and self-servingly appropriated. Beat poetry was a first response to these trends, born in Columbia University but dispossessed almost immediately as the colleges closed ranks rapidly. Some version of this dichotomy played out in a hundred academies: tenured professors in the halls, modernist genius in portraits on the walls, the vitality and individuality worthy of their natural successors shut out, excluded, forced outside the institutions.

The battle lines were rapidly arranged. Post-modernism was the armor chosen by the academy.

It didn't take long for it to spread. The benefits to conceited mediocrity and fearful conservatives and entrenched comfortable nepotism and lazy hubristic intellectuals was soon obvious. Post-modernism calcified into a cross-faculty movement that's been consolidating power ever since. Generations later it dominates in universities, converges with democratised consumerism and infiltrates all facets of 21st century society. POST-MODERNISM AS NEOLIBERAL FREEMASONRY

Post-modernism, having taken over the arts faculties, cross-pollenated into the outside world to colonise much of the mainstream media. Its spread and tenacity is testimony to its lasting appeal and the temptation to succumb to those worst instincts will follow a person's whole career, readily at hand should an academic or artist or media hold-out go through moments of doubt or crises of confidence or face a choice between principled independent hardship and acceptance plenty and security in joining the club. Neoliberalism is the post-modernist economics heart of this choice and this is as good a definiton as any for the pressures exerted on non-members. It needs no guns and cudgels to achieve its ends.

But why is this particular club so bad? Isn’t neoliberalism better than totalitarian communism? Couldn’t post-modernist principles be liberating for young minds stifled by the straightjacket canon of past generations? This could have been argued until the 1980s though even then the post-modernist exponents were already the children of diminished progenitors. The nature of the temptation post-modernism offers is too strong for most to resist. The early post-moderns began as pale fire apologists cowed by the challenge of modernist genius.

The post-war academics were indeed a mixed bunch, elder statesmen increasingly marginalised by: well-organised successors greedy for authority but unable to use sheer talent to justify their positions, professional iconoclasts in pursuit of misguided but sincere notions of democratising the academy, hostile to received wisdom and suspicious of outlier excellence, career academics increasingly threatened by the ongoing intellectual diaspora from broken Europe closing ranks to formalise systems that levelled the playing field, etc. With a few exceptions, it was left to America to carry the torch of academic continuity for at least a generation 1950s until as late as the 1970s. Europe and now East Asia are no longer behind North America but the parochial professionalism of the baby boomer period has injected itself deeply on the institutions, post-modernism the mechanism of delivery, neoliberalism lubricating the ambitions of its moving parts.

Post-modernism is particularly pernicious, once sufficiently widespread, because it gives faithful advocates a multipurpose toolkit designed perfectly for its continued spread and consolidation. The toolkit is subtle and subject specific, cynical and utilitarian, honed - ironically - by thousands of extremely clever engineers of corporate academia. It covers jargon and linguistics, provides litmus tests to gauge friends and enemies, dividing and conquer transformation of safe zones promising academic enquiry and widespread publicity so long as there’s no gainsay of post-modernism's unwritten rules. Like in a masonic lodge, would-be exponents of their contemporary post-modernist doctrines (and goals) receive informal schooling in identifying one another.

Half a century later the network is well established throughout the world, organised like Islam and its cooperative imam-led cells, it has the academy locked in a stranglehold. Outsiders, outliers and would-be rebels can be pinpointed and delegitimised with remarkable precision, without compromising any individual mason (or, in most cases, committing any single institution). There’s no need to instruct how to exculpate rebels at the time of rebellion. Everyone in the lodge has the toolkit and already knows how to use it against objectionable targets.

TRUTH IS LIES - LOVE IS HATE - PEACE IS WAR - PLENTY IS STARVATION

What might've started as a complex of motivations driving numerous schools of thought soon became comfortable and entrenched, conformism aligning with conservativism to appropriate tradition, especially in the face of counter culture having mobilised opposing forces that might’ve risen to the challenge of modernist luminaries with genius of its own e.g. Jack Kerouac and the beats, Tennessee Williams and the Southern renaissance, James Baldwin and the civil rights movement. These individuals were pushed out onto the front line dismissing academia as unwelcoming or careers in journalism as unworthy. The post-modernist arsenal had its first wave of targets. An insidious schism between the academy and the individual had been transposed onto a global narrative of culture versus counter culture that’s been polarising ever since.

"The mediocre mind is incapable of understanding the man who refuses to bow blindly to conventional prejudices and chooses instead to express his opinions courageously and honestly" -- Albert Einstein (1879-1955)

The battle for the hearts and minds of the many academic institutions and plethora of media outlets, print, radio, television, film was irreparably divisive by the end of the 1960s. Vietnam, hippy counter culture anti-nationalism and the Situationists student revolts against corporate consumerism brought the power of the state into direct conflict with the individual. The timing was fortuitous and the ideological conflict already well developed within the universities made post modernists natural bedfellows with those pushing the agenda of state authority. Both saw their chance: to marginalise dissenters, including untrustworthy writers and auteurs and non-conformists professors. And, worst of all, anyone cheating the median by presuming to exhibit genius out of context becomes a threat to the mainstream social order, subject to a takedown by every means available in the formidable post-modernist playbook.

DEATH OF THE AUTHOR GONE MAINSTREAM

The breakthrough of post-modernism into mainstream culture can be marked into two distinct phases: the silent expansionist war and the loud entrenched victory.

Roland Barthes, French philosopher and literary critic, provided the seminal concept that allowed post-modernism's craven iconoclasm to market itself into mainstream culture. His 1962 work Le Mort d'Auteur "Death of the Author" gave credibility to the academy's anti-individual disdain of virtuosity in art, claiming the hard won life works of artist and scientist alike without having to acknowledge the standards as an implicit challenge. Celebrity was permissible, even desirable, but would be no democracy of equal participants trying to establish an influential off-narrative platform if it boiled down to a meritocracy 'won' by genius and hard work. Personal nuance was to be aggregated into group identity, rules by the academy, propaganda by Barthes and other misrepresented thinkers.

All this contributes to make post-modernism a toolkit for appropriaton, aggregation, subjugation of the individual to the aim of the groups. Recently #metoo is the latest diseased manifestation, born of feminism and the wholly authentic attacking on misogyny as endemic patriarchy, turned into a way to bring down experts and excellence unwilling to confirm to the post-modern dictates of entrenched groupthink - in this case selected by gender.

"What the public wants is the image of passion, not passion itself." -- Roland Barthes Mythologies (1957)

The details of post-modernism evolution from movement to all-encompassing modus operandi needn't be repeated here. There are islands of resistance dotted around the academy and schools with sincere useful ideas not seeking to feed the growing monolith like structuralism, post-structuralism and deconstruction. These more authentic strains in philosophy and literary theory went through their own smaller conflicts, the leading lights like Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Jean Baudrillard, Noam Chomsky marginalized in plain site, separated from the mainstream of the academy in special departments - a standard measure in the post-modernist manual when dealing with intransigent voices grown too noisy to gag or too marketable to deplatform into insignificance.

The most expedient aspects of post-structuralism and, increasingly, any new idea cropping up in academic circles, came to be identified fast then, notwithstanding the stubborn individuals whose future had to be isolation or exculpation, brought into the post-modernist mainstream. Post-structuralism was cannibalised into one of the most insidious movements of the latter culture war years: identity politics.

Feminism, civil rights, the fight against homophobia, legitimate movements all but in the hands of post-modern spin doctors were twisted to serve different goals and increase the firepower of the academy, the ambitious arbiters of culture. This has been one of the most criminal abuses of the post-modernist cabal.

"...for better or worse, it is the commentator who has the last word." -- Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire (1962)

The appropriation of feminism, sexuality and race should be a practical warning of the ultimate bankruptcy of post-modern ideology. Great women or great gay artists or non-white virtuosos aren't freed from the shackles of traditional homophobic white male-privilege, to aspire to whatever greatness might be attained by their individual unfettered potential. Instead this potential is cut away just as it is with any other presumption of genius. The method is different but the post-modern iconoclast has a diverse toolkit. Women are demeaned into ciphers, gays into icons all face no substance, black writers forced to be poster boys and poster girls ringfenced into representing only a narrow group identity that's as racially segregated as any pre-war ghetto. At best the new oppression is coercive rather than violent but great art is often inspired by oppression. It's certainly always born from distinction by individual outliers and to be deprived of this is to make mediocre currency of great potential. It's ironic that the casualties of this particular battle are the very people the identity political advocates pay lip service to free and defend.

WHERE DOES “DEATH OF THE AUTEUR” END?

From innocent beginnings in the late 1940s, the movement known as post-modernism has evolved into a freemasonry of entrenched anti-intellectual mob legitimacy. It is positioned in the mainstream, confident and on the attack. It has appropriated a dozen counter-cultures, rebranding and often inverting their original good, turning them into cultural sticks to beat society into submission: feminism into gender politics, anti-misogyny into #metoo, anti-homophobia into queer theory, the civil rights movement into affirmitive action, free speech constrained by political correctness. Post-modernism has become ubiquitous, unarguably legitimate stamped with academy credibilty, spread from the institutions through society by brigades well-taught graduates. These days there’s only one line of defence against the self-serving end-game post-modernism continues to drive towards: the independent individual.

Disorganised, unusual, independent, mostly atomised and often contrarian, the individual presents a disunited self-centred front - easy target for patient groupthinkers - but it’s the only other game in town. Complete victory for the post-modernist cabal will mean a society without genius, truth subjugated to expediency, a safe zone so widespread no-one notices it looks the same as obsolescence.

"The bastard form of mass culture is humiliated repetition... always new books, new programs, new films, news items, but always the same meaning." -- Roland Barthes (1915-1980)

The first post-modernist generation passed the latest literary, linguistic and philosophical theory - especially schools of thought coming out of France and Germany - through the prism of democratised merit and everyman relativism to construct an extremely effective popular legitimacy serving the conceits of the tenured academy. The career academic had an arsenal fit for the destruction of reputations and the exculpation of non-conforming genius. The success of this “death of the author” spin, cloaked in the complex language of post-structuralism and other extant obfuscating theory gave the post-modernists a commanding position by the end of the 1960s. This hegemony expressed itself into mainstream culture through successive waves of graduates.

The post-modernist academy bound itself hand in glove with state authority, underpinned by an intellectual neoliberalism sold to the public as responding to the vocational demands of the free market. Anything of substance seeking to thwart the academy or the increasingly polarising state narrative was tarred with the ‘counter culture’ brush, ornery youth the first victims (e.g. the beat generation) but soon anything off-narrative was subjected to the same process of marginalisation (in the case of individuals) and appropriation (in the case of movements).

What little resistance remained in the arts faculties was picked off over the post-Vietnam decades, neoliberalism and consumer capitalism natural bedfellows with post-modernism in a way that solidified in the 80s, integrated branding in the 90s and had become received wisdom - unquestioned, presumed part of the natural order - by the millennium. Small wonder this entrenched cultural regulation adapted quickly to take hold of the internet and, in particular, ringfence social media, turning the latter into a vehicle for population control and echo chamber isolation of contrarian thinkers.

There was no way the post-modernist culture would allow itself to be challenged by changes to the dynamics of society. Vigilant, pro-active and anti-individual to the marrow, the mainstream must remain committed to post-modernisms proven methodology. No genius could be allowed to turn a platform into a pedestal. No expert could be given credible authority over truth, however many facts might be marshalled in support.

"The petit-bourgeois is a man unable to imagine the Other. If he comes face to face with him, he blinds himself, ignores and denies him, or else transforms him into himself." -- Roland Barthes, Mythologies (1957)

There’s something incredibly human about the early motivations of the academics, humiliated by the challenge of modernist achievements, occupying positions of authority but incapable (or unwilling) to go to the same lengths to justify their cultural power. It was wrong but it wasn’t an incomprehensible show of weakness. Perhaps if it had been able to admit a little nuance - like humility - the future would have been different. It wasn’t, however. Committed to a reductive perversion of intellectual relativism, quick to define the opposition in counter cultural terms, increasingly partnered with state expediency, things only got worse and more widespread and more difficult to dislodge in the decades to come.

"I believe in the value of the book, which keeps something irreplaceable, and in the necessity of fighting to secure its respect." -- Jacques Derrida (1930-2004)

The rotten core of the post-modern movement remains throughout, though, and as it’s forced to greater lengths to prosecute an absolute authority, so much the reality and the impact on culture grow more extreme. Today it weaponises such awful characteristics as toxic envy and endemic narcissism. Mediocrity has become synonymous with common sense, conformity means to follow dogma and deny individual free thought. Power dynamics are abused daily, inverting expertise to a sin, traditions of excellence as oppressive patriarchy and individuality subsumed - whether you like it or not - into identity politics where transgression brings the most dire of consequences.

The post-modernist end-game is, by default, a mix of populism and passive aggression. There can be leaders, in the post-modern paradigm state, but these must be celebrities or accidents of ethnicity. Meritocracy becomes lottery - and lottery is an easier sell to a public convinced of its own self-worth but conditioned never to be examined, except for compelled social function. Death of the author and exclusion of individual genius makes life into a reality show - authenticity at arms length - an easy fit with slogans of democracy and universal median values. Equality itself is a twisted principle: not so much equality of outcome as equality of process. The whole system is delivered through the worst of human traits: vanity, egoism, outrage and opinion over complex nuance. It’s a recipe for mediocrity, at best, a disconnection with centuries of intellectual and cultural tradition that may not be restored. In a multifarious world, if we accept the broad sweep of history as led by the enlightenment West and the utilitarian East, it’s the former at risk of becoming obsolete.

We’re quick to spot the nightmare dystopian East when we hear about China and its surveillance social media scorecards for a billion citizens but the West is heading for worse. Mediocrity is a creeping death and will increasingly fall behind as the world moves forward. The Western traditions that have nurtured individual freedom and - quite rightly - arranged a natural order of achievement around encouraging and nurturing genius and original thought: all of this is at risk if the post-modernist social order achieves complete victory. Soon enough the voices of protest and their cries of “Shakespeare” “Newton” “Einstein” “Tesla” “Feinstein” “Goethe” “Nietschze” “Kerouac” “Dante” “Michelangelo” “Freud” “Jung” “Chomsky” “Orwell” will die away. What remains will be the echoing hubbub of an outraged mob that amounts to nothing more than an irrelevant cultural silence.

"There's a blaze of light in every word It doesn't matter which you heard The holy or the broken Hallelujah" -- Leonard Cohen (1934-2016)

0 notes

Text

just thinking about how, for the past 25 years, aeon fandom used canon as a cudgel to beat people with

but ever since SW came out, they've become completely disempowered.

like it was really rocky when SW first came out and aeon fandom threw their little tantrum, but now?

people in overall RE fandom now feel safe enough to actually come out and say "hey i think this ship kinda sucks actually" without getting mobbed by a bunch of mouthbreathers going OKAY BUT IT'S CANON THO AND THERE'S NOTHING YOU CAN DO ABOUT IT LOLOL IT'S CANON

because it's not canon anymore

and i think people are waking up to the fact that "it's canon" is the only thing the ship had going for it in the first place

14 notes

·

View notes