#shulamith shahar

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hot tip for all you ladies out there:

If your husband cannot satisfy you in matters of conjugal love, consider taking a trip to the statue of Saint Uncumber in St Paul’s cathedral. If you set a peck of oats at her feet, she’ll straight up destroy your husband! Once Saint Uncumber has carried him off, maybe try one of those convents you’ve heard so much about. I hear it’s a very fulfilling place for those inclined to assist their sisters in Christ.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!

What books do you recommend for someone who wants to read more about religion/middle ages but doesn't know where to start?

love your blog btw <3

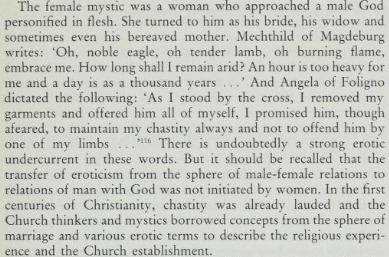

Hello, friend! The Female Mystic by Janelle Dickens is an excellent introduction. For something more in-depth, anything by Caroline Walker Bynum. Holy Feast and Holy Fast focuses specifically on the religious significance of food to medieval women but is also comprehensive as a general study.

I would also recommend Medieval Women's Visionary Literature as a primary source(book)!

Not exclusively about religion, but definitely The Fourth Estate by Shulamith Shahar, too!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

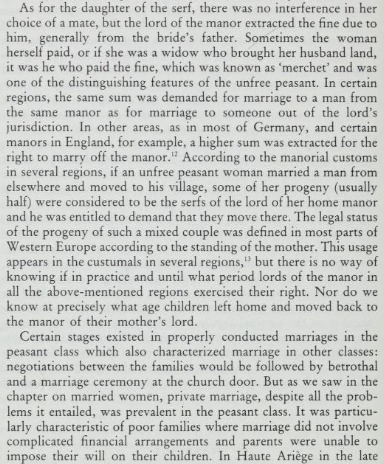

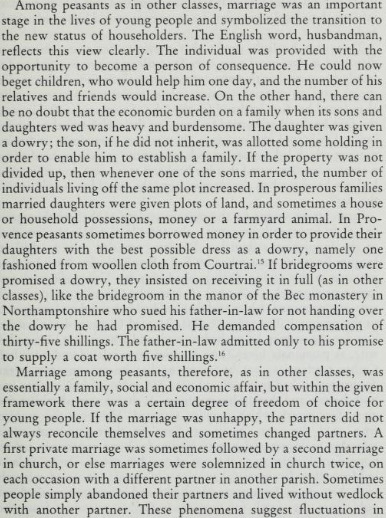

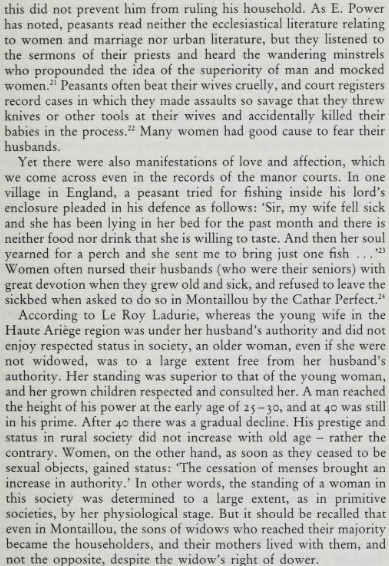

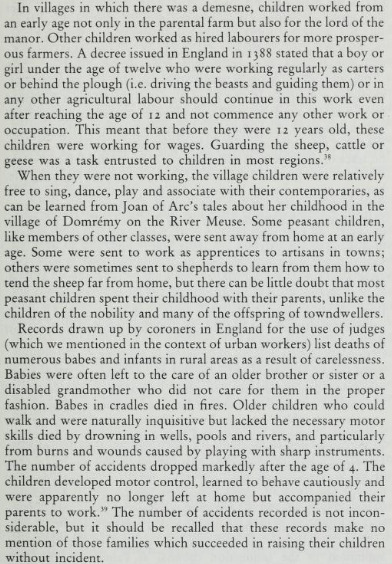

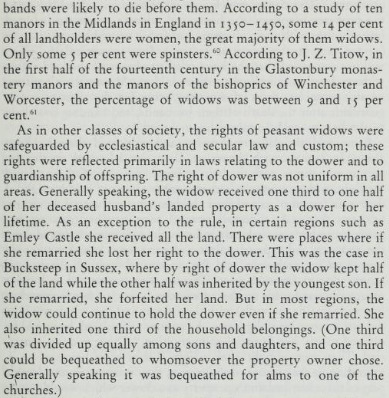

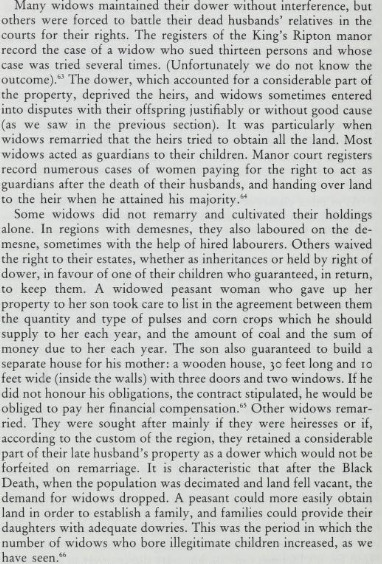

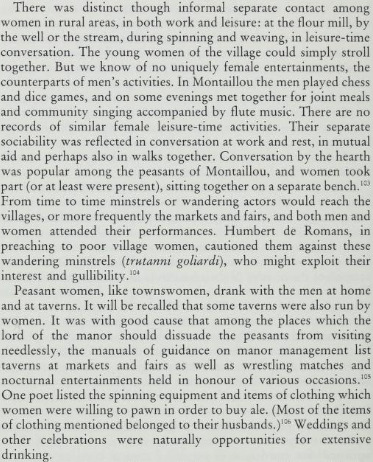

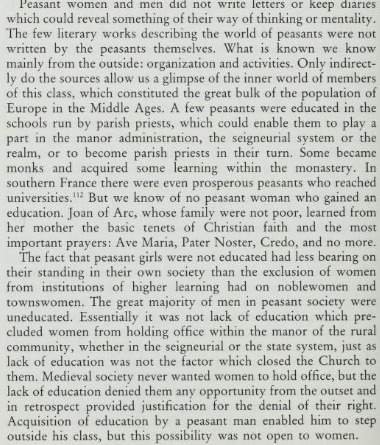

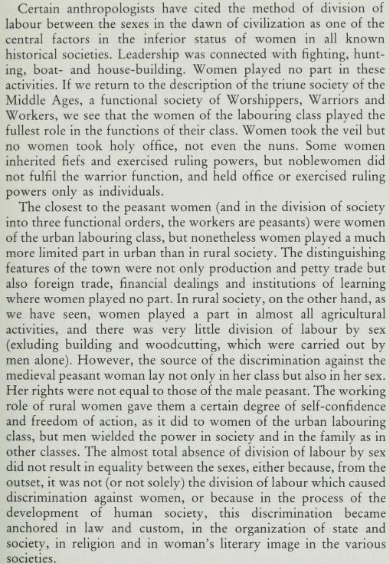

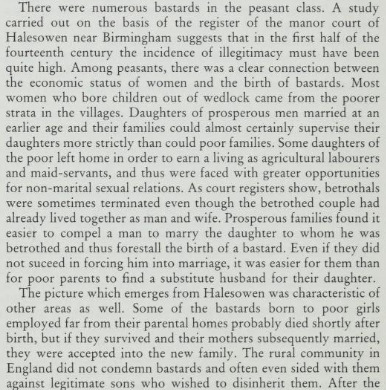

Women in the Middle Ages: Women in the Peasantry

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

13 notes

·

View notes

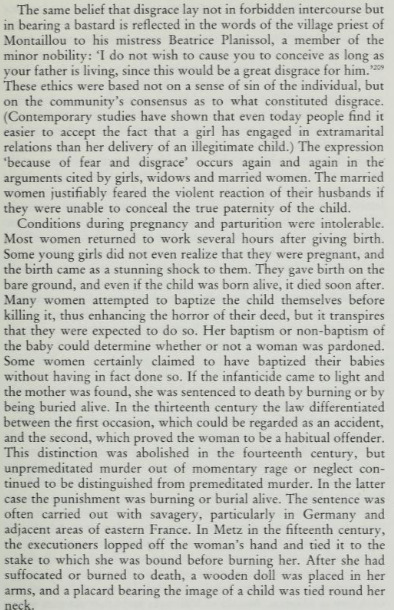

Text

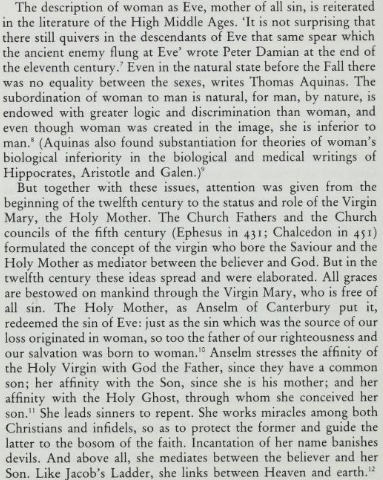

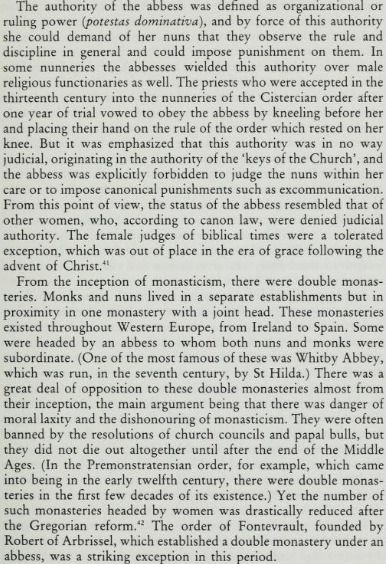

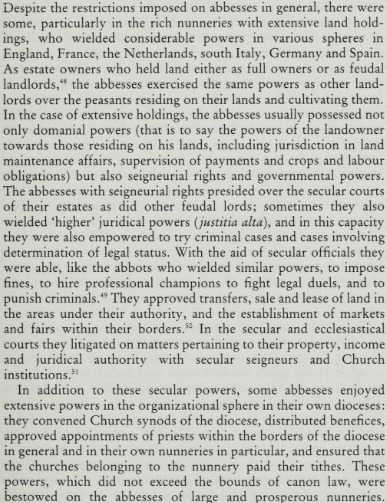

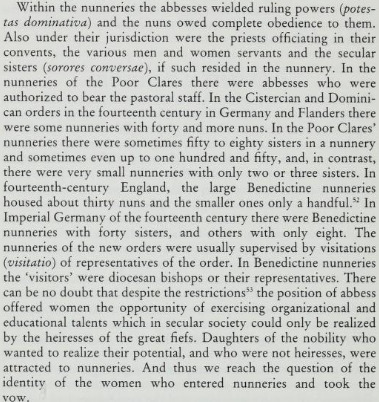

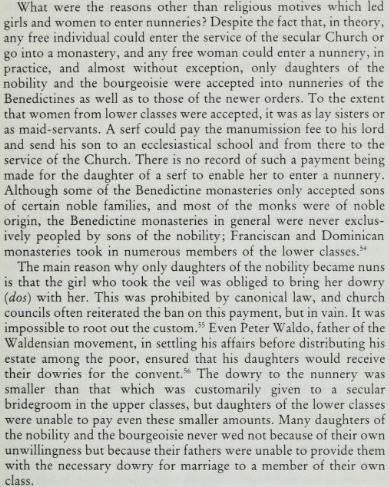

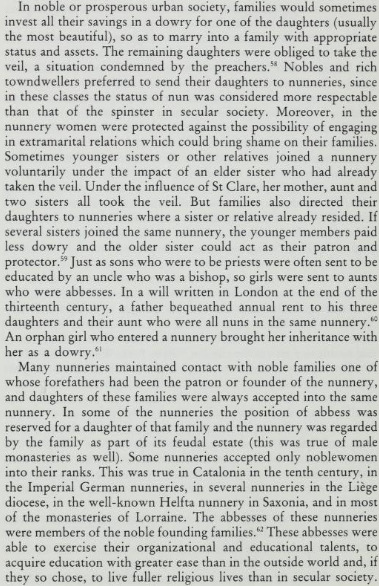

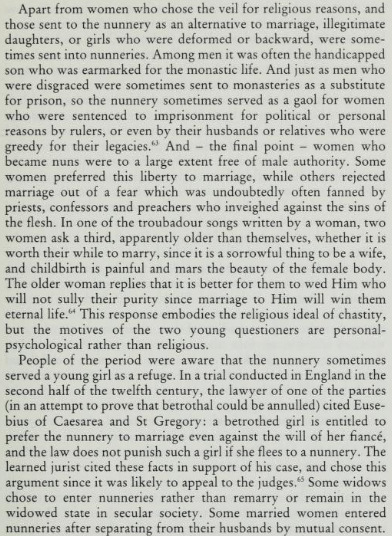

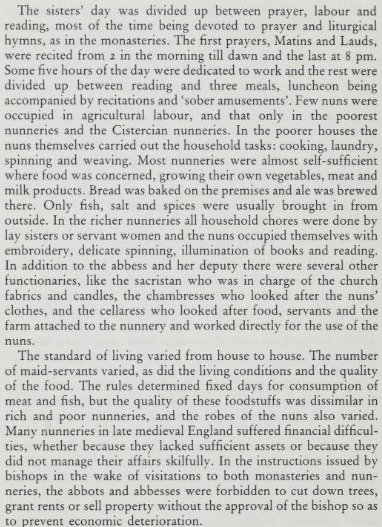

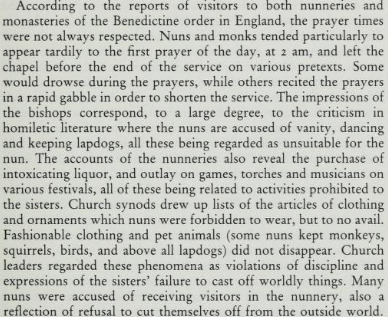

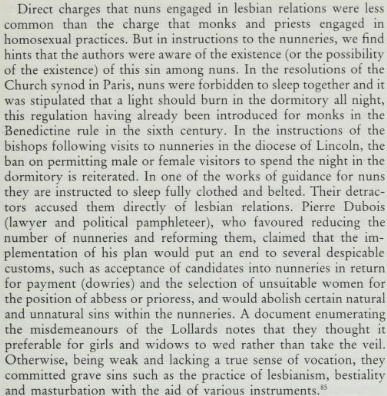

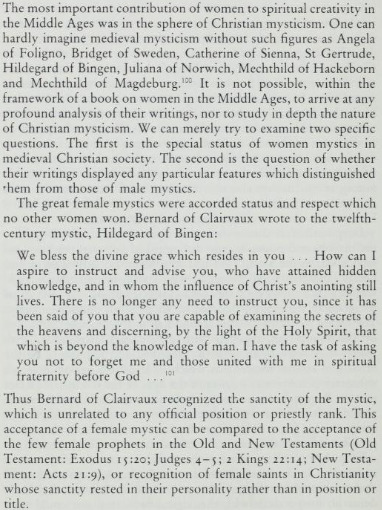

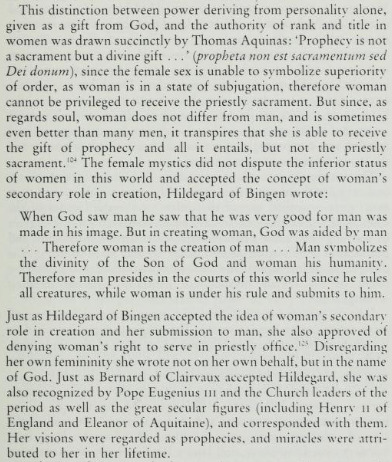

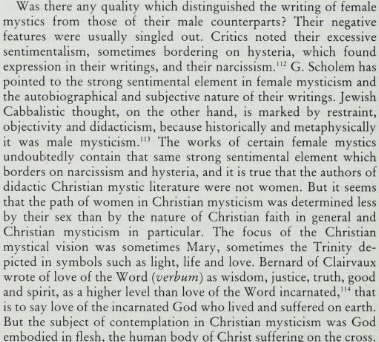

Women in the Middle Ages: Nuns

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

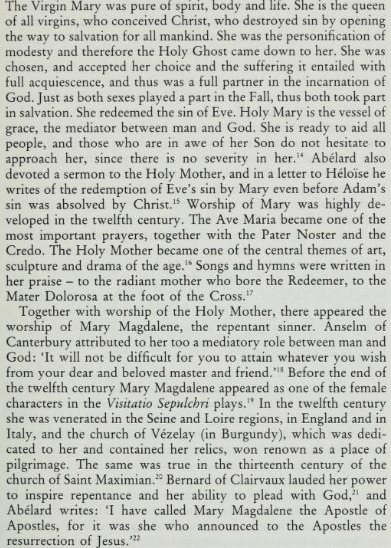

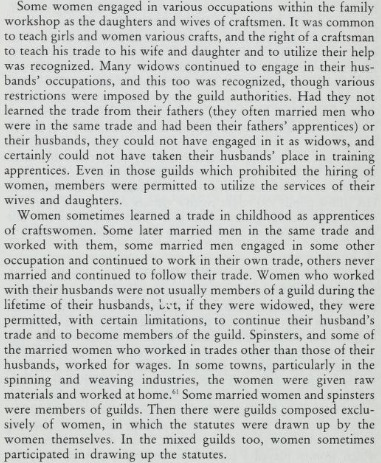

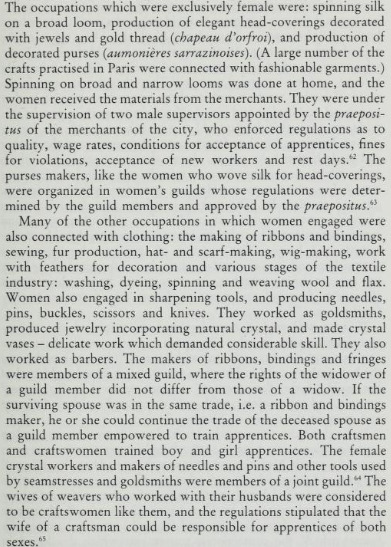

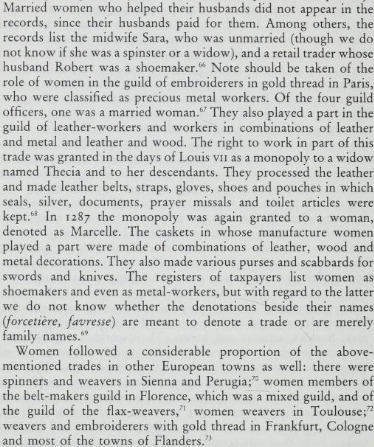

Women in the Middle Ages: Women’s Work

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

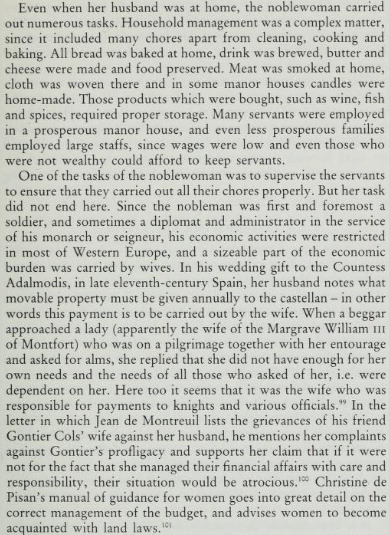

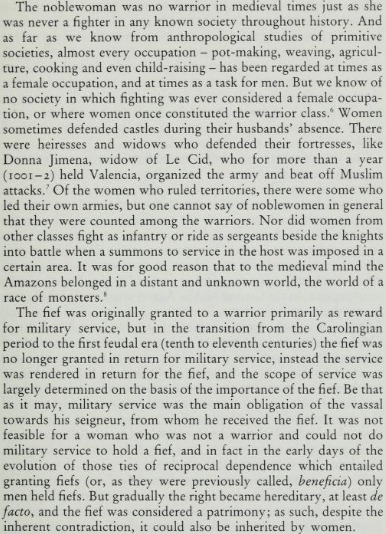

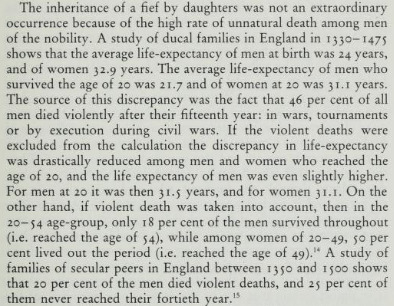

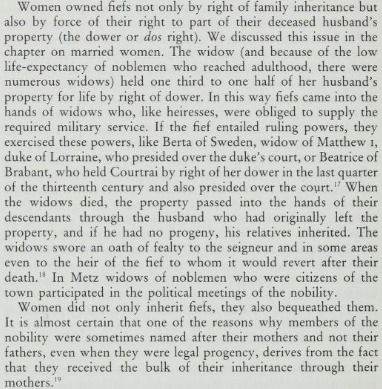

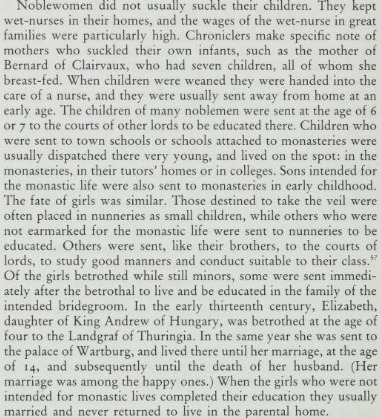

Women in the Middle Ages: Women in the Nobility

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

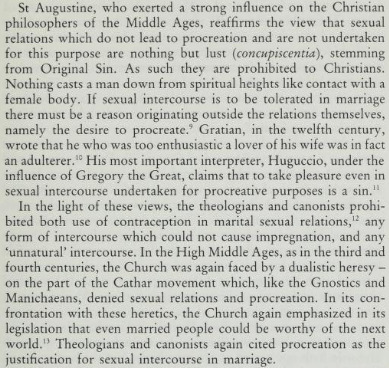

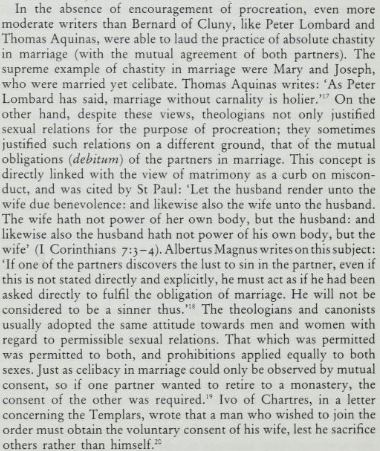

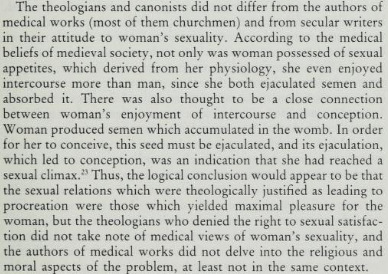

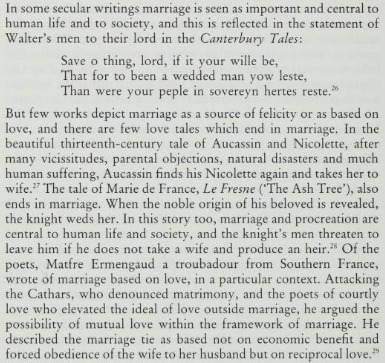

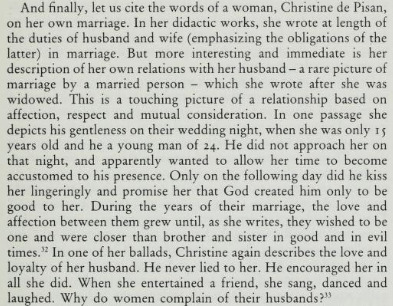

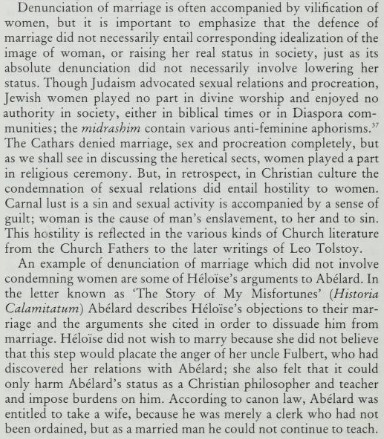

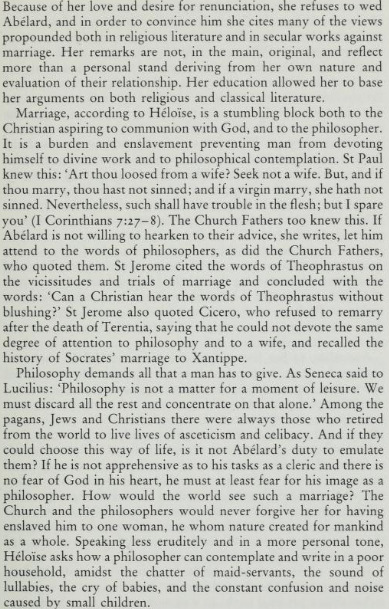

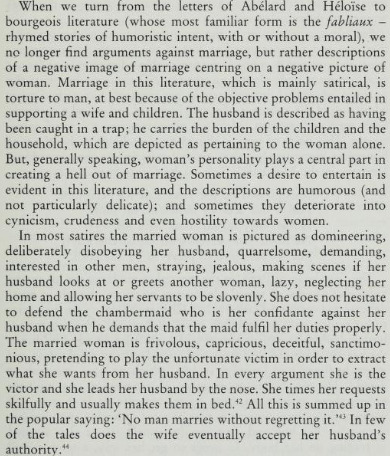

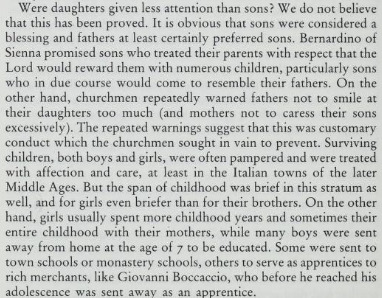

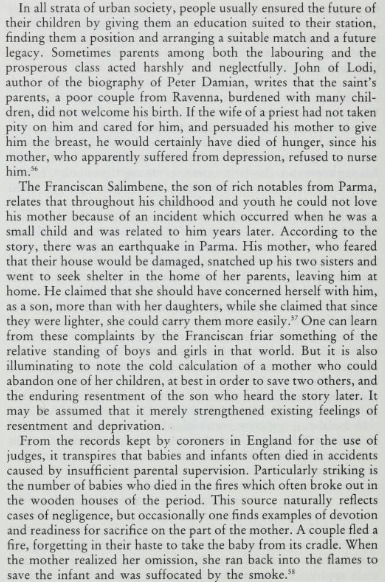

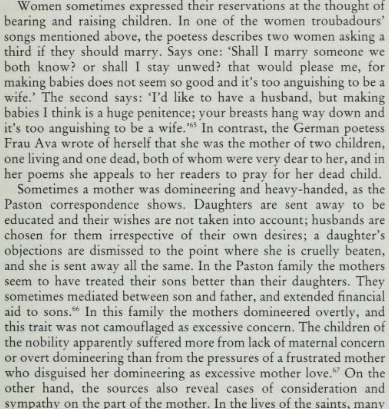

Women in the Middle Ages: Married Women

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

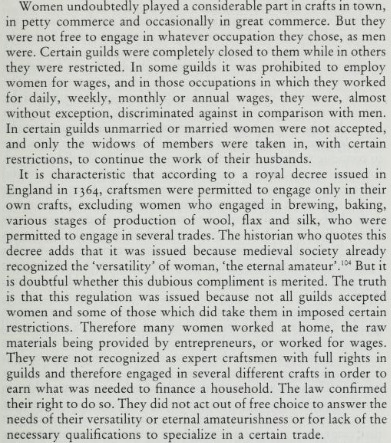

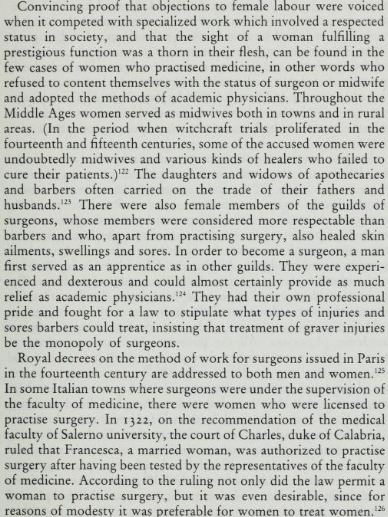

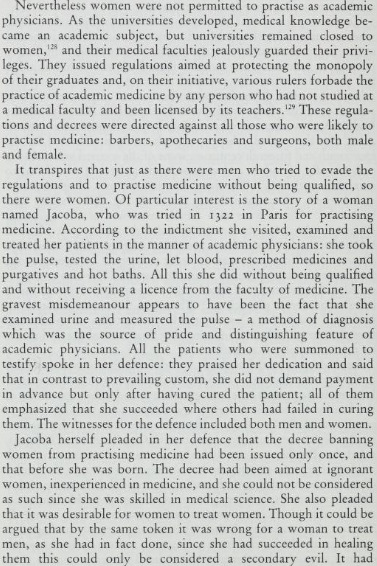

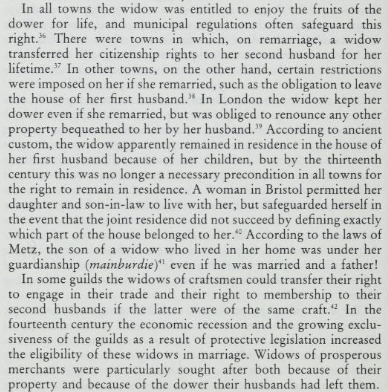

Women in the Middle Ages: Townswomen

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

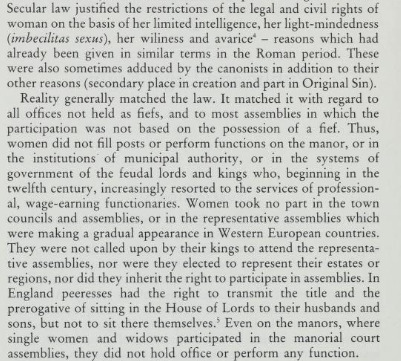

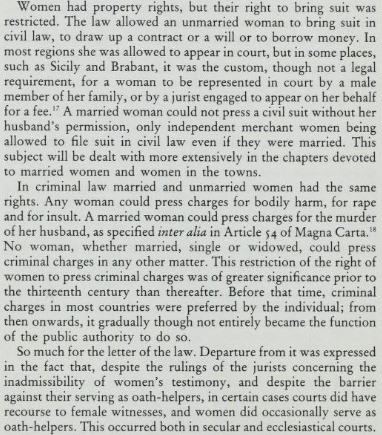

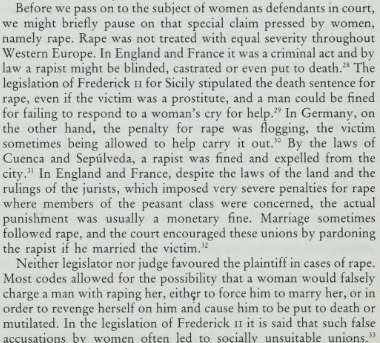

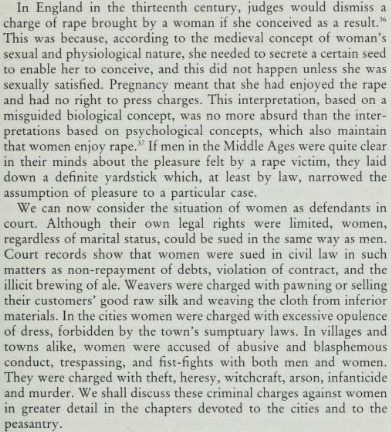

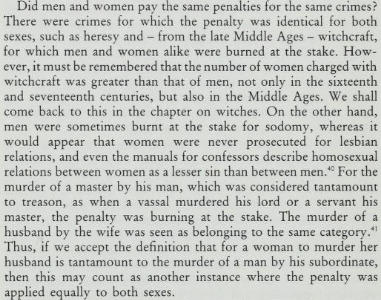

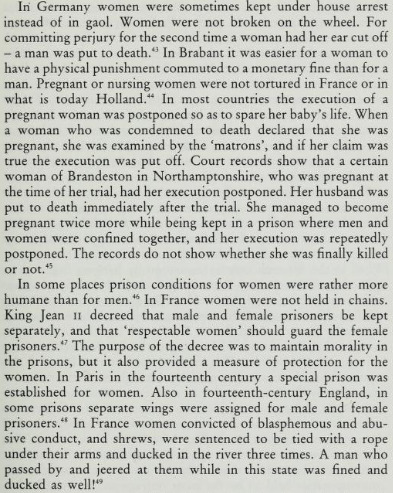

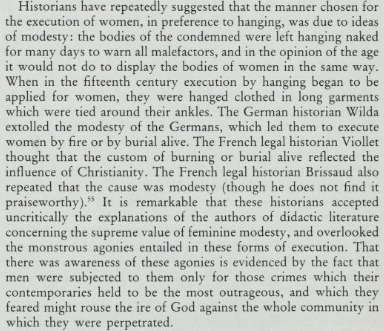

Women in the Middle Ages: Public and Legal Rights

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

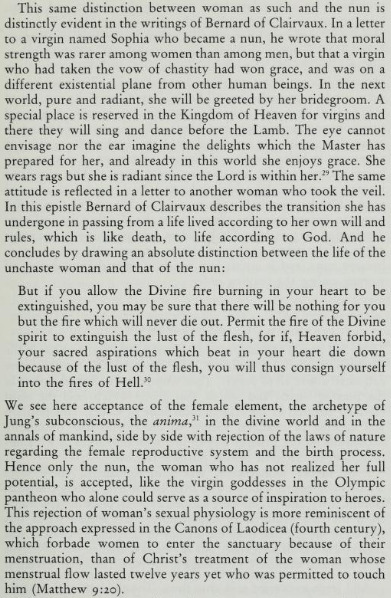

Women in the Middle Ages: Nuns

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

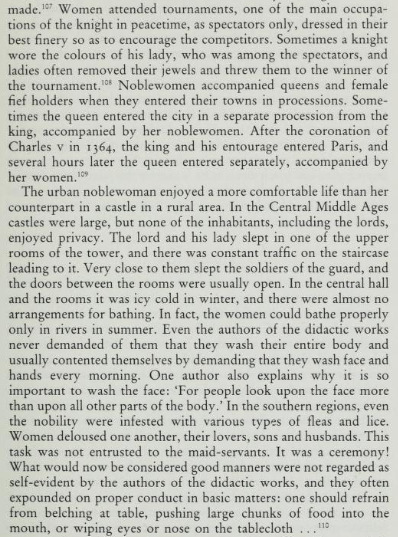

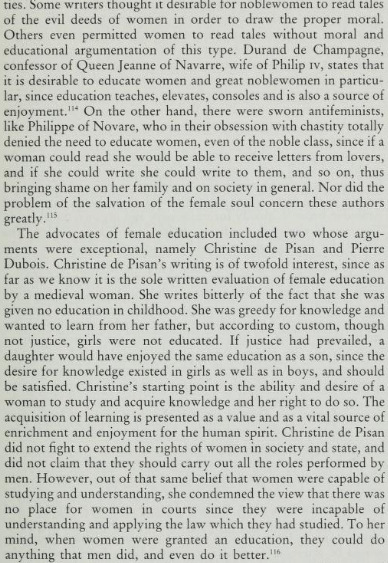

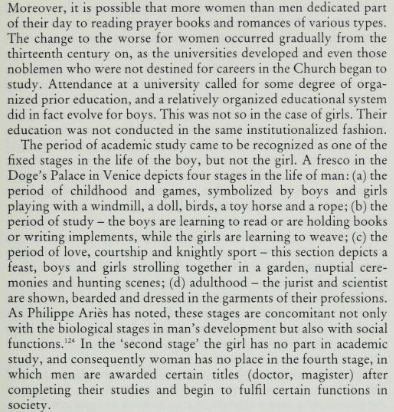

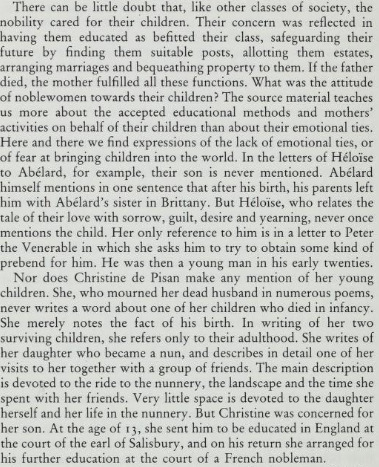

Women in the Middle Ages: Women in the Nobility

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

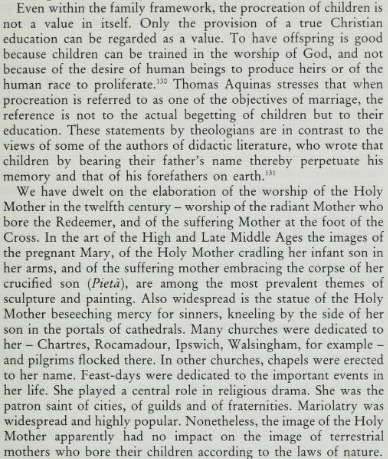

Women in the Middle Ages: Married Women

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

None of the medieval movements of political or social revolt sought to improve the status of women, nor was there ever a feminine movement to improve the condition and extend the rights of women. A singular case is reported tersely in the annals of the Dominicans of Colmar: 'A maiden came from England who was comely and well-spoken. She said that she was the Holy Spirit who had become incarnate for the salvation of womankind. She baptized the women in the name of the Father, the Son and Herself. After she died she was burnt at the stake.'

Shulamith Shahar, From The Fourth Estate: A History of Women in the Middle Ages

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Throughout the Middle Ages and into the sixteenth century, most Europeans believed that God had intentionally organized society in a particular way, imposing certain obligations on people in every societal role, at every level. Protestant reformers built upon this idea in focusing on the nuclear family, convinced that the family was the God-given, fundamental unit in spreading the reform of both church and society. Within the family, there were those responsible for leading and instructing—father first, but also mother—and those in need of teaching and nurture—the children. Both good parenting and responsible behavior on the part of children came to be seen as obligations not only to God and to one’s family, but also to the surrounding community.

Even the most idealistic of reformers did not believe that the effective use of catechism books and sermons alone would result in appropriately faithful and responsible children. Physical discipline was required as well. Corporal punishment was common in medieval and early modern Europe—a fact that Ariès and Stone used as evidence that parents in those time periods did not love their children in the same way that (ideal) modern parents do. Yet most sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers who addressed the topic advised restraint in corporal punishment. Most Protestant reformers believed that children needed some moderate physical discipline—including beating—to help them resist the overwhelming temptation to sin.

The Anabaptist reformer Menno Simons wrote: “Constrain and punish [your children] with discretion and moderation, without anger or bitterness, lest they be discouraged.” This caution against extreme violence was a common sentiment; at the same time, one of the greatest complaints of reformers who wrote about disciplining children was that parents overindulged their children. Protestant leaders believed that either extreme—physical abuse or overindulgence—could both harm a child and dishonor God. Of course, the words of reformers did not translate directly into stricter or more lenient behavior on the part of parents. Nevertheless, their views did have a direct impact on the lives of children in the Reformation.

One of the most significant developments during the Reformation, in terms of children’s lives, was a heightened emphasis on parental responsibility and an increased oversight of family life by church and civic authorities. It is helpful to view the reformers’ increasing attention to enforcing parental responsibility in connection with the Protestant rejection of the cult of saints, which marked a major religious and social change beginning in the sixteenth century. Praying to saints was a fundamental resource for medieval Christians, including parents who sought help caring for their children. Shulamith Shahar tells the story of a woman who, forced to leave her daughter at home in order to fulfill a work obligation to her landlord, prayed to a saint to watch over her child while she was gone.

Medieval Europeans, both church officials and laypeople, accepted such dependence on the mercy of saints in people’s daily lives. Protestant reformers rejected this role of saints as mediators between human beings and God; they rejected even more forcefully the idea that saints could act to intervene in people’s daily lives. This meant that the responsibility of caring for children fell entirely on living human beings: parents, neighbors, and church and civic authorities. The community, then, was of key importance to the reformers. Particularly in Calvinist areas, church members were strongly encouraged to pay close attention to the behavior of their neighbors and to report any “un-Christian” actions to the consistory.

Medieval Europeans also had intervened in the affairs of their neighbors, but with the establishment of consistories in the sixteenth century, people could now report their concerns directly to an immediately responsive authority. Some children benefited from the reports of concerned neighbors. When the Genevan consistory learned that Claude Gardet had beaten her daughter until her face bled, and that she had a pattern of such excessive discipline, they banned her from communion and sent her to the city council for punishment. But consistories did not provide absolute protection for children. Most contented themselves with admonishing parents and then sending them back home, unless they believed a child’s life was in immediate danger.

Lest we are left thinking that all early modern parents were abusive, it is also important to note that in other cases church and secular authorities insisted on more discipline than parents thought appropriate. In such cases children might find themselves in situations where their parents seemed to be protecting them from the church authorities, rather than vice versa. This could lead to confrontations between consistories and parents, as when the Genevan consistory summoned two men for “not having wanted to do their duty in chastising their children as they had been ordered to by the consistory.”

Overall it appears that the actual physical treatment and experiences of children did not change drastically as a direct result of the Reformation. Religiously and legally, children had the right to expect that they would be clothed and fed by their parents, but they themselves had little power to enforce this right. Most children remained at the mercy of their parents well into their teenage years (and of their masters, if they were working as apprentices or servants). And most parents sought to provide for their children and to find some method of moderate but effective discipline. While parents had the responsibility to train and support their children and the right to discipline them, children also had obligations to their parents.

These duties sometimes developed into points of conflict as the children became adolescents and young adults who might spend their parents’ money carelessly, not support parents in need, or even physically abuse their parents. For young children, however, resistance to family obligations rarely rose to the level of public attention. While it is difficult to be certain about how young children reacted to those expectations, we do know that obligations to their parents were reinforced in many phases of their upbringing, including daily family life, catechism lessons, and even school.

Viewed in one way, the changes provoked by the Protestant Reformation imposed new restrictions on the lives of children— stricter expectations, somewhat more organized attempts to teach the catechism, enforcement of very particular understandings of Christianity that would have significant impact on how children came to understand the world, and reinforcement of parental authority, especially that of fathers. On the other hand, all of these changes must be viewed within the context of life in the sixteenth century. Throughout the period of the Reformation, life remained uncertain in even more ways than it is today.

After several centuries of outbreaks of the plague, climatic changes, and civil wars, the Reformation might be seen broadly as an attempt to bring stability and order to society and perhaps to gain some slightly increased confidence about one’s status in the eyes of God. From this standpoint we might see Protestant efforts regarding children in a more positive light. From a religious point of view, reforming theologians argued that children were an important part of the “family of God” from the time of their birth and, for that very reason, deserved faithful nurture and care from their parents. In the best situations, children experienced these teachings in the diligence and care that their parents applied to raising them. In other instances, church and civic authorities intervened in attempts to guide wayward parents in their duties to their children.”

- Karen E. Spierling, “Baptism and Childhood.” in Reformation Christianity

#karen e. spierling#history#reformation#reformation christianity#christian#renaissance#religion#children

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Many parents of all classes sent their children away from home to work as servants or apprentices - only a small minority went into the church or to university. They were not quite so young as the Venetian author suggests, though. According to Barbara Hanawalt at Ohio State University, the aristocracy did occasionally dispatch their offspring at the age of seven, but most parents waved goodbye to them at about 14. Model letters and diaries in medieval schoolbooks indicate that leaving home was traumatic. "For all that was to me a pleasure when I was a child, from three years old to 10… while I was under my father and mother's keeping, be turned now to torments and pain," complains one boy in a letter given to pupils to translate into Latin. Illiterate servants had no means of communicating with their parents, and the difficulties of travel meant that even if children were only sent 20 miles (32 km) away they could feel completely isolated.

So why did this seemingly cruel system evolve? For the poor, there was an obvious financial incentive to rid the household of a mouth to feed. But parents did believe they were helping their children by sending them away, and the better off would save up to buy an apprenticeship. These typically lasted seven years, but they could go on for a decade. The longer the term, the cheaper it was - a sign that the Venetian visitor was correct to conclude that adolescents were a useful source of cheap labour for their masters. In 1350, the Black Death had reduced Europe's population by roughly half, so hired labour was expensive. The drop in the population, on the other hand, meant that food was cheap - so live-in labour made sense.

"There was a sense that your parents can teach you certain things, but you can learn other things and different things and more things if you get experience of being trained by someone else," says Jeremy Goldberg from the University of York. Perhaps it was also a way for parents to get rid of unruly teenagers. According to social historian Shulamith Shahar, it was thought easier for strangers to raise children - a belief that had some currency even in parts of Italy. The 14th Century Florentine merchant Paolo of Certaldo advised: "If you have a son who does nothing good… deliver him at once into the hands of a merchant who will send him to another country. Or send him yourself to one of your close friends... Nothing else can be done. While he remains with you, he will not mend his ways."

Many adolescents were contractually obliged to behave. In 1396, a contract between a young apprentice named Thomas and a Northampton brazier called John Hyndlee was witnessed by the mayor. Hyndlee took on the formal role of guardian and promised to give Thomas food, teach him his craft and not punish him too severely for mistakes. For his part, Thomas promised not to leave without permission, steal, gamble, visit prostitutes or marry. If he broke the contract, the term of his apprenticeship would be doubled to 14 years. A decade of celibacy was too much for many young men, and apprentices got a reputation for frequenting taverns and indulging in licentious behaviour. Perkyn, the protagonist of Chaucer's Cook's Tale, is an apprentice who is cast out after stealing from his master - he moves in with his friend and a prostitute. In 1517, the Mercers' guild complained that many of their apprentices "have greatly mysordered theymself", spending their masters' money on "harlotes… dyce, cardes and other unthrifty games".

In parts of Germany, Switzerland and Scandinavia, a level of sexual contact between men and women in their late teens and early twenties was sanctioned. Although these traditions - known as "bundling" and "night courting" - were only described in the 19th Century, historians believe they date back to the Middle Ages. "The girl stays at home and a male of her age comes and meets her," says Colin Heywood from the University of Nottingham. "He's allowed to stay the night with her. He can even get into bed with her. But neither of them are allowed to take their clothes off - they're not allowed to do much beyond a bit of petting." Variants on the tradition required men to sleep on top of the bed coverings or the other side of a wooden board that was placed down the centre of the bed to separate the youngsters. It was not expected that this would necessarily lead to betrothal or marriage.

To some extent, young people policed their own sexuality. "If a girl gets a reputation of being rather too easy, then she will find something unpleasant left outside her house so that the whole village knows that she has a bad reputation," says Heywood. Young people also expressed their opinion of the moral conduct of elders, in traditions known as charivari or "rough music". If they disapproved of a marriage - perhaps because the husband beat his wife or was hen-pecked, or there was a big disparity in ages - the couple would be publicly shamed. A gang would parade around carrying effigies of their victims, banging pots and pans, blowing trumpets and possibly pulling the fur of cats to make them shriek (the German word is Katzenmusik). In France, Germany and Switzerland young people banded together in abbayes de jeunesse - "abbeys of misrule" - electing a "King of Youth" each year. "They came to the fore at a time like carnival, when the whole world was turned upside down," says Heywood. Unsurprisingly, things sometimes got out of hand. Philippe Aries describes how in Avignon the young people literally held the town to ransom on carnival day, since they "had the privilege of thrashing Jews and whores unless a ransom was paid".

In London, the different guilds divided into tribes and engaged in violent disputes. In 1339, fishmongers were involved in a series of major street battles with goldsmiths. But ironically, the apprentices with the worst reputation for violence belonged to the legal profession. These boys of the Bench had independent means and did not live under the watch of their masters. In the 15th and 16th Centuries, apprentice riots in London became more common, with the mob targeting foreigners including the Flemish and Lombards. On May Day in 1517, the call to riot was shouted out - "Prentices and clubs!" - and a night of looting and violence followed that shocked Tudor England. By this time, the city was swelling with apprentices, and the adult population was finding them more difficult to control, says Barbara Hanawalt. As early death from infectious disease became rarer the apprentices faced a long wait to take over from their masters. "You've got quite a number of young men who are in apprenticeships who have got no hope of getting a workshop and a business of their own," says Jeremy Goldberg. "You've got numbers of somewhat disillusioned and disenfranchised young men, who may be predisposed to challenging authority, because they have nothing invested in it."

How different were the young men and women of the Middle Ages from today's adolescents? It's hard to judge from the available information, says Goldberg. But many parents of 21st Century teenagers will nod their heads in recognition at St Bede's Eighth Century youths, who were "lean (even though they eat heartily), swift-footed, bold, irritable and active". They might also shed a tear over a rare collection of letters from the 16th Century, written by members of the Behaim family of Nuremberg and documented by Stephen Ozment. Michael Behaim was apprenticed to a merchant in Milan at the age of 12. In the 1520s, he wrote to his mother complaining that he wasn't being taught anything about trade or markets but was being made to sweep the floor. Perhaps more troubling for his parents, he also wrote about his fears of catching the plague. Another Behaim boy towards the end of the 16th Century wrote to his parents from school. Fourteen-year-old Friedrich moaned about the food, asked for goods to be sent to keep up appearances with his peers, and wondered who would do his laundry. His mother sent three shirts in a sack, with the warning that "they may still be a bit damp so you should hang them over a window for a while". Full of good advice, like mothers today, she added: "Use the sack for your dirty washing."

- William Kremer, “What medieval Europe did with its teenagers.”

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

“One of the areas in which the Middle Ages seems to be vilified most in the modern world is in medieval people’s decisions about parenting; for example, fostering their children with other families at a young age. While it’s true that often some of the decisions about child-rearing in different periods and cultures seem bizarre to us now, it’s just as often (if not more) that their behaviour is actually familiar to us. When it comes to taking care of babies in the Middle Ages, this meant swaddling them and rocking them in cradles.

Babies then, as babies now, were susceptible to cold, so it was of the utmost importance that they were kept as snug and warm as possible. In the medieval world, this meant swaddling. Infants were wrapped in cloth and then swaddled with bands around their bodies to keep their limbs close and to keep their blankets secured. In Childhood in the Middle Ages, Shulamith Shahar writes that this may also have been an effort to keep an infant’s limbs growing straight. In medieval manuscript images, babies are often shown swaddled and very straight – almost like Egyptian mummies. This may suggest that babies were swaddled tightly enough that they weren’t able to bend their legs like little inchworms, but there may be a simpler explanation: it might just have been much easier to draw them this way.

Swaddled babies were put to sleep in cradles in both rich and poor households, although the nature of the cradle would be very different in each. Royalty would have richly carved and gilded cradles, while the poorer folk might have had to do with a box or basket. In Medieval Children, Nicholas Orme gives an example of this difference when he describes Henry VII’s household’s immense cradle for state occasions. Decorated with the arms of his house and filled with plush fabrics, at seven-and-a-half feet long and two-and-a-half feet wide, this monstrosity would have dwarfed a little princeling and kept his admirers well back. As newborns are not very mobile, the more humble baskets of the poor would have functioned perfectly well, as the boxes currently supplied to Scotland’s new mothers bear out.

Cradles in the Middle Ages were often more sophisticated than this, however, with the means to rock the baby without having to take him or her out of it. Some were suspended from the ceiling like hammocks to make rocking easy with a gentle push or a pull from a rope. The cradles which sat on the floor were often equipped with rockers, something which Shahar suggests were perhaps a medieval invention. As anyone who’s rocked back too far in a chair will know, rockers make it easier for a piece of furniture to tip, which meant that it was important to find ways to prevent this when it came to these tiny, precious members of the household. To solve this problem, medieval people fixed straps and buckles to their cradles to keep babies from falling out if they were knocked by animals or siblings.

A baby in a cradle was still not completely out of danger, however. Cradles were often placed close to the hearth in order to keep children warm, but this brought about accidents, too. As Shahar says, an accident common to babies was scalding, as hot pots and kettles might have splashed as they were carried to and from the fire. Babies who were left unattended (very likely more out of necessity than callous neglect, I would argue) were in danger of being mauled by animals like pigs, as in the coroners’ reports Orme cites.

Tragic though these accidents are, they were accidents, and the intention of medieval parents was always to keep their babies safe. To this end, Shahar notes that doctors and preachers advised against babies being taken to bed with their parents because of the danger of suffocation (co-sleeping continues to be hotly debated today). It’s understandable that a parent would want to take a baby to bed in order to facilitate both breastfeeding and warmth, despite these warnings, so it’s noteworthy that, as Shahar points out, Peter Abelard chose accidental suffocation as an example when he wanted to show the difference between outcome and intent: though the outcome might be tragic, the parent’s intent to care for the child was clearly good. Beyond the potential for accident, Shahar also notes that one fourteenth-century writer (Bernard Gordon) advises against co-sleeping because children will like it too much, and won’t want to sleep in their own beds (as many a modern parent has discovered). Cradles were therefore seen to be the better option to medieval minds.

Having a cradle isn’t sufficient to get a baby to sleep (unfortunately). Usually, for this miracle to occur, someone has to rock it. Royals, again, could use their money to solve this problem, hiring people whose principal work was to rock the royal cradle. These people were titled “rockers” or (even better) “rocksters”. As Orme notes, the Percy family was having none of their own sleep interrupted: they hired two rockers. For the poor, as ever, rocking the cradle was just one more thing to add to their list of chores.

Orme points out that Piers Plowman contains a mention of this specifically among the unpleasant things a medieval peasant had to deal with. In a moment many modern parents can relate to, William Langland describes the experience of bleary-eyed parents everywhere: And woe in winter-time with waking at nights,/To rise to the ruelle [bedside] to rock the cradle.”

- Danièle Cybulskie, “Taking Care of Babies in the Middle Ages.”

9 notes

·

View notes